Theory of permanence

Object Permanence: Piaget's Theory, Age It Emerges, Examples

Object permanence is the understanding that objects continue to exist even when we can’t actually see them.

Object permanence, or object constancy, in developmental psychology is understanding that things continue to exist, even if you cannot seem them.

Infants younger than around 4-7 months in age do not yet understand object permanence.

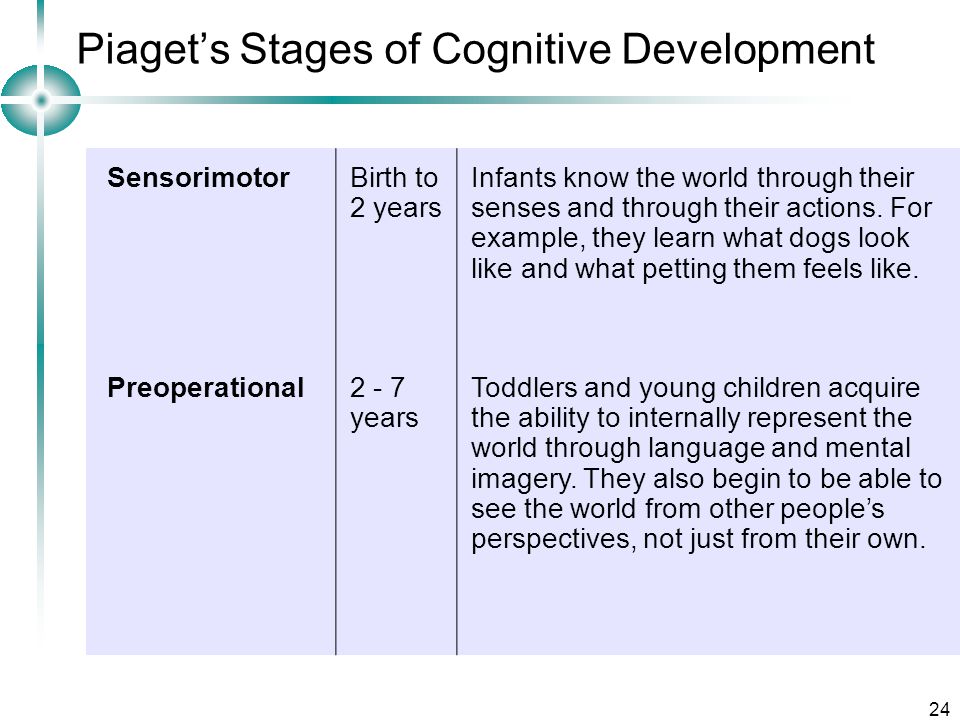

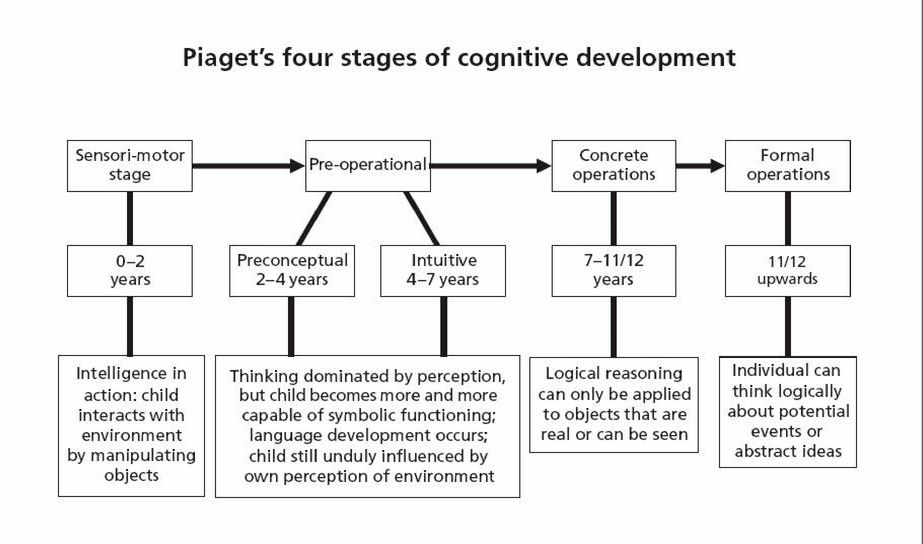

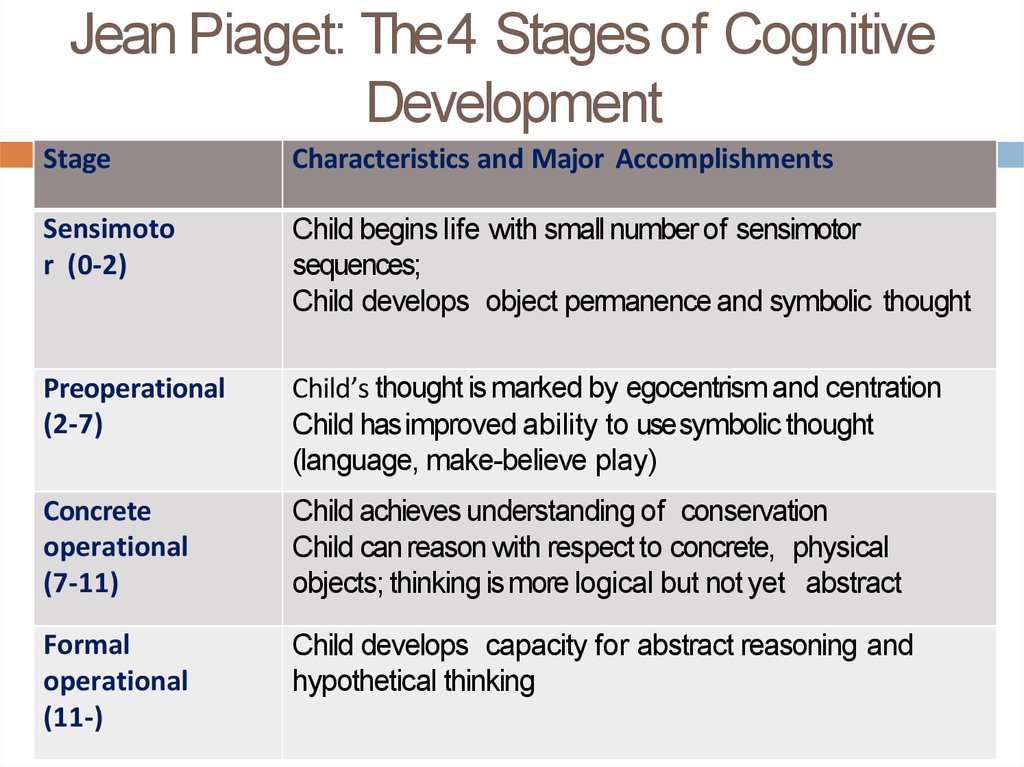

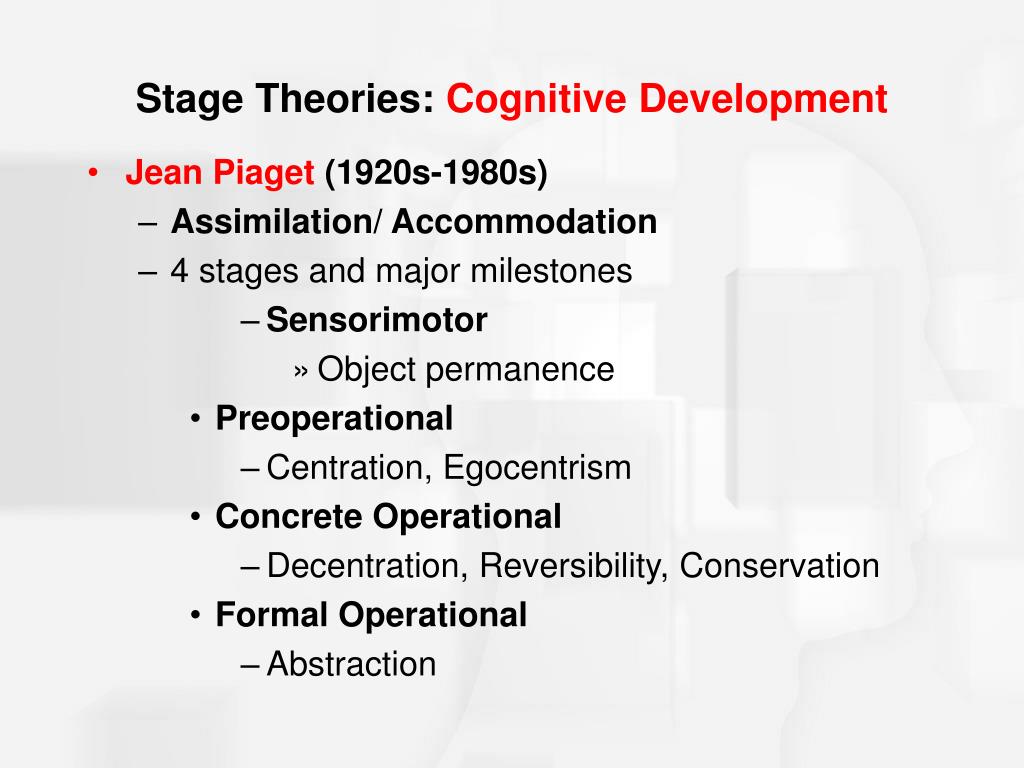

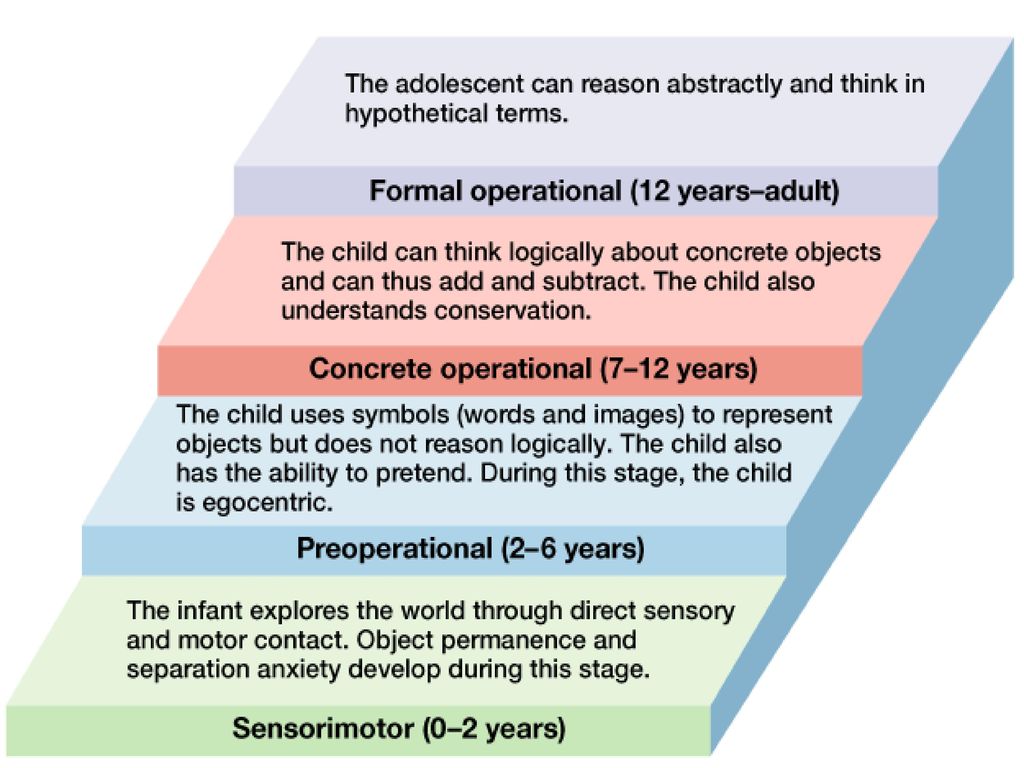

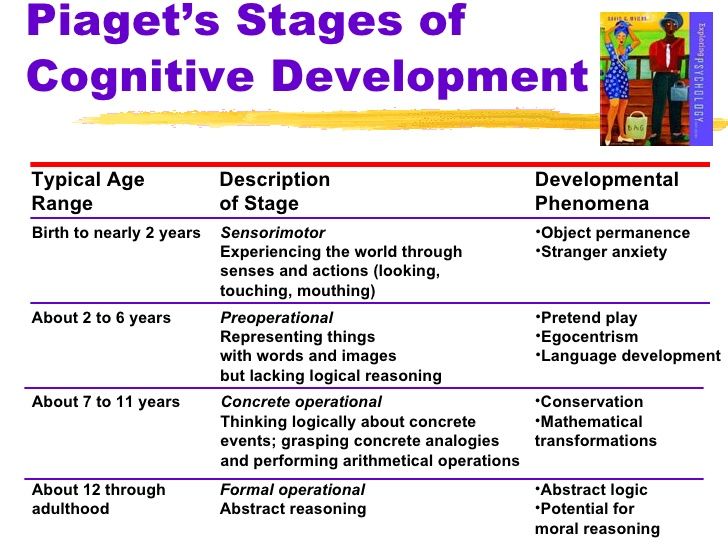

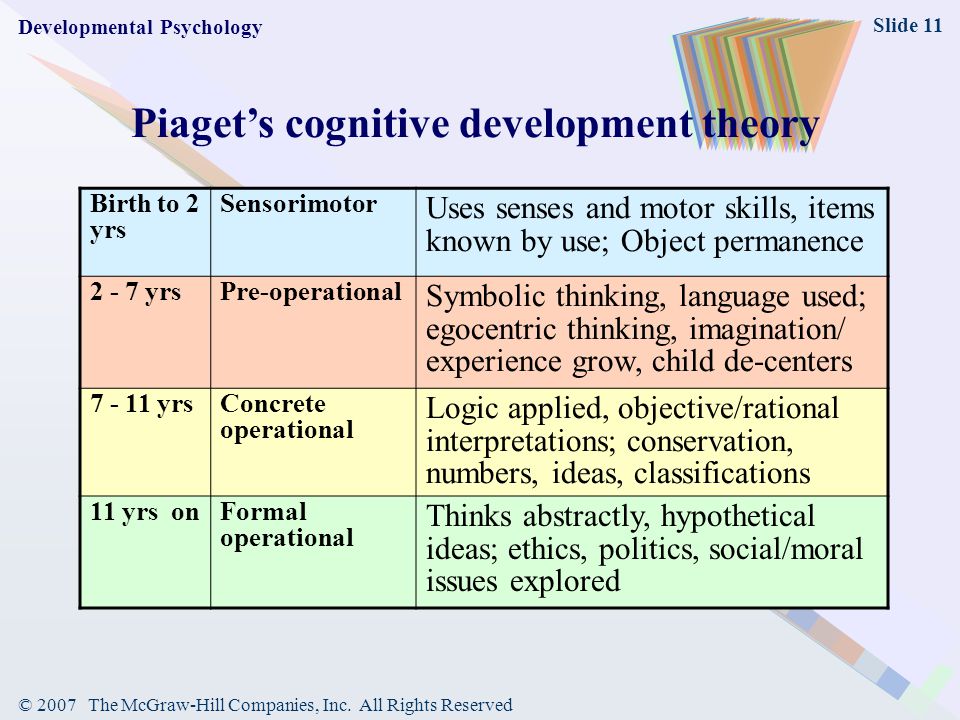

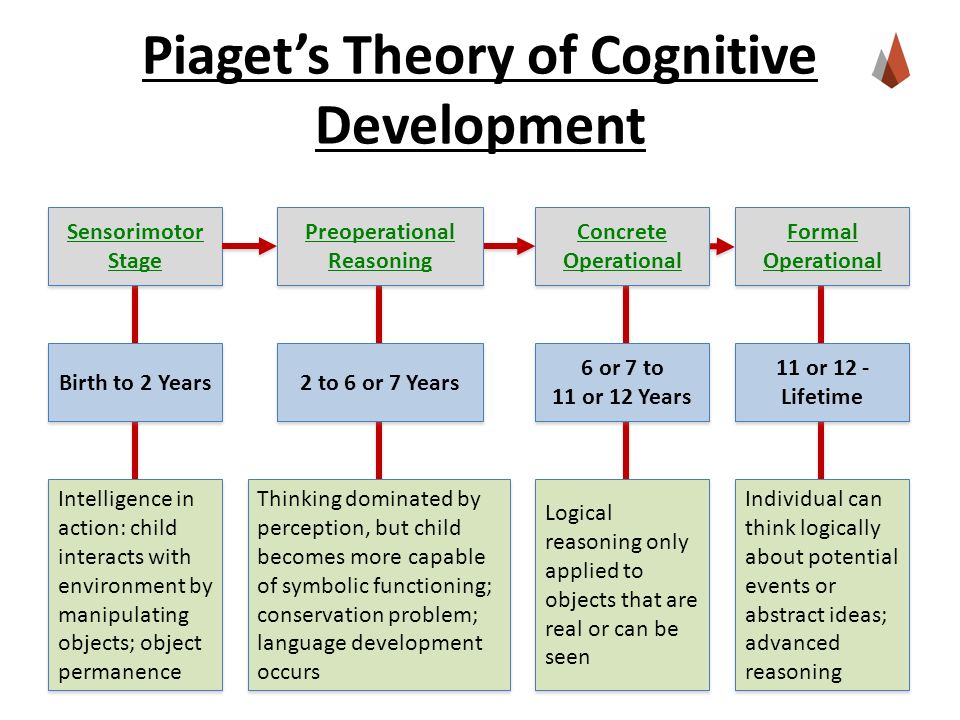

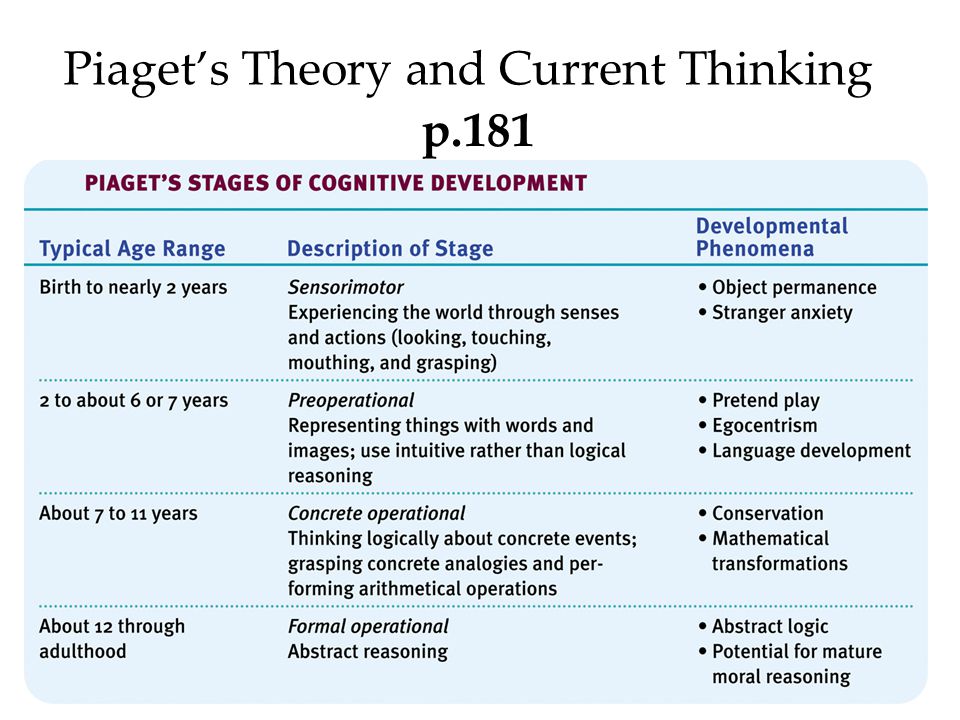

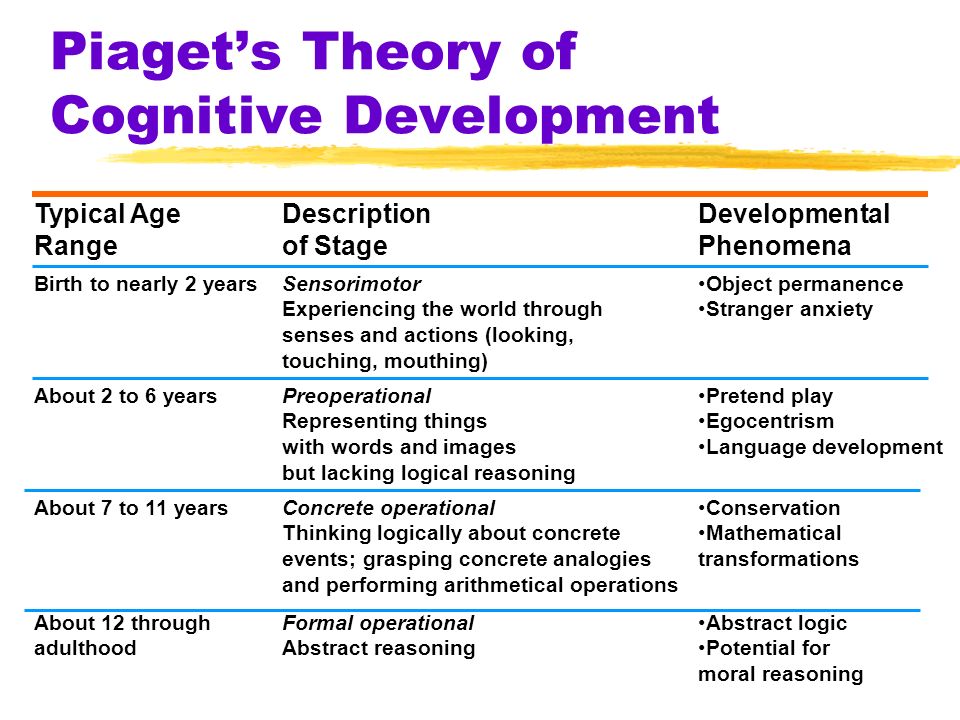

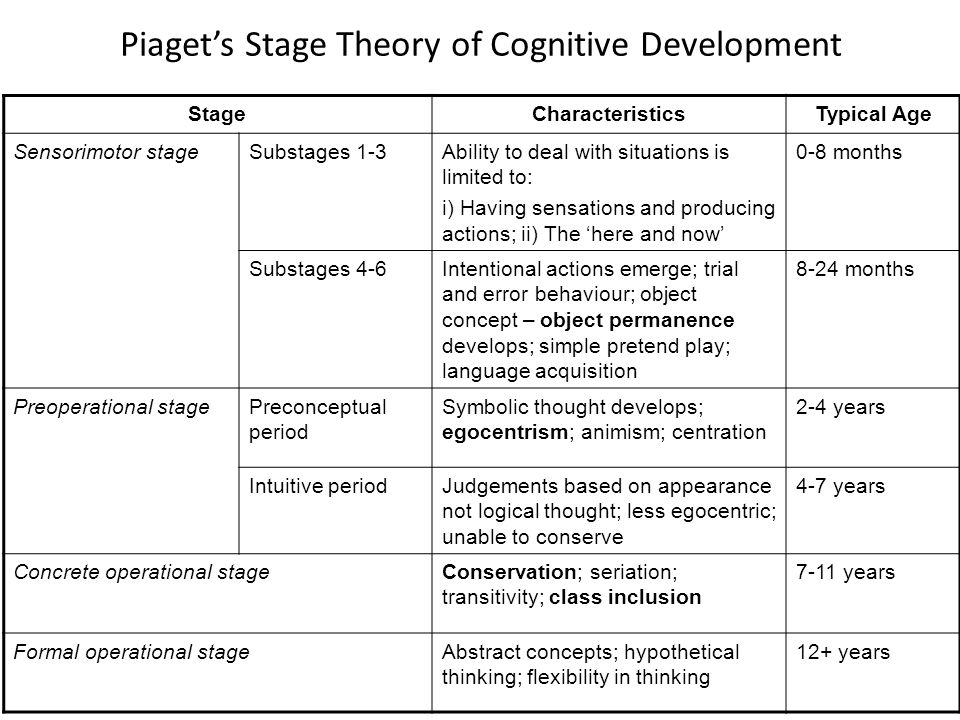

Understanding object permanence is a key part of Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development.

Before they can develop an understanding of object permanence, young children must have a mental representation of an object.

Without understanding object permanence, though, young children must wonder where the world goes when they close their eyes.

Perhaps young infants, brand new in the world, experience their environment as a kind of nonsensical dream in which even the simplest properties of objects surprise them.

Or, perhaps they do have some intuitive understanding that objects continue to exist even when they can’t be directly experienced?

This is the question psychologists have been trying to answer while researching what infants in their first year of life understand about ‘object permanence’.

Jean Piaget’s theory of object permanence

From his research, Piaget concluded that children couldn’t properly grasp the concept of object permanence until they were at least 12 months of age.

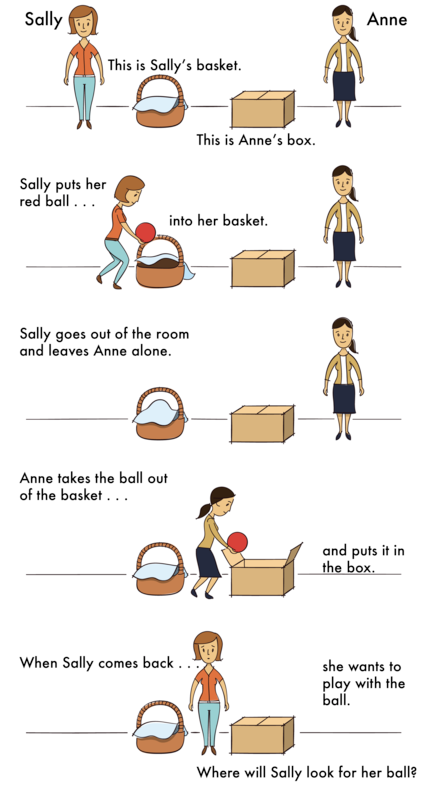

In a typical experiment Piaget would show a toy to an infant, then hide it or take it away.

Piaget would then watch to see if the child searched for the toy.

From experiments like these, Piaget developed a six-stage theory of object permanence:

- 0–1 months: Reflexes – First babies use their reflexes to understand and explore the world. Their awareness of objects is poor, as is their eyesight.

- 1–4 months: Primary circular reactions – Babies start to notice some objects and movements are enjoyable. They discover their feet, arms and hands.

- 4–8 months: Secondary circular reactions – These are when babies do something to create a reaction, such as reaching for an object that is partially hidden. However, babies do not yet reach for hidden objects, perhaps suggesting a lack of understanding of object permanence.

- 8–12 months: Coordination of secondary circular reactions – One of the most important stages for cognitive development. Now the infant is goal-directed. This is when the earliest understanding of object permanence starts. Children can pull objects out from hidden locations.

- 12–18 months: Tertiary circular reaction – The child starts using trial-and-error to learn and solve new problems. The child can retrieve an object when it is hidden several times, as long as they can see it first.

- 18–24 months: Invention of new means through mental combination – A full understanding of object permanence occurs at this age. A child can understand when objects are hidden in containers. In Piaget’s theory, this is because children have developed mental representations. They can imagine the object without being able to see it.

Criticism of Piaget’s theory

Piaget has often been criticised for underestimating children’s abilities, in particular of object permanence.

Piaget’s ideas were challenged by a series of studies on object permanence carried out by Professor Renee Baillargeon from the University of Illinois and colleagues (e.g. Baillargeon & DeVos, 1986).

These studies used children’s apparent surprise at ‘impossible’ events to try and work out whether they understood object permanence.

Examples of modern object permanence research

In one study infants as young as 6.5 months watched a toy car travelling down a ramp.

Half way through its journey, though, it went behind a screen out of the baby’s view before exiting the other side, once more visible.

In one condition the infants saw a block placed behind the screen in the way of the toy car.

And yet when the car was released, experimental trickery was used so that the block didn’t stop the car’s progress.

Miraculously it still appeared from the other side of the screen.

This ‘impossible’ condition was compared with another condition where the block was placed near, but not in the way of, the car’s progress – the ‘possible’ condition.

Baillargeon found that the infants looked reliably longer at the seemingly impossible scenario.

This suggested they understood that the block continued to exist despite the fact they couldn’t actually see it.

They also must have understood that the car could not pass through the block.

This seems like reasonable evidence that infants can understand object permanence.

Object permanence from 3.5 months-of-age

In further studies Professor Baillargeon tested all sorts of variations on this theme.

Toy rabbits, toy mice and carrots were all used, with some defying the laws of nature in the ‘impossible’ conditions and others studiously following them in the ‘possible’ conditions.

Each time, though, infants looked longer at the apparently impossible events, perhaps wondering if they were dreaming.

These studies have now shown that infants as young as 3.5 months seem to have a basic grasp of object permanence.

While others have argued for alternative explanations and interpretations, when all these studies are taken together the idea that children understand object permanence is arguably the simplest explanation.

Infants are intuitive physicists

Using these results Baillargeon and others have argued that young infants are not necessarily trapped in a world of shapes which have little meaning for them.

Instead they seem to be intuitive physicists who can carry out rudimentary reasoning about physical concepts like gravity, inertia and object permanence.

So, perhaps infants don’t perceive the world as a completely nonsensical dream.

Sure, they have many new things to learn and many things surprise them, but they do seem to understand some fundamentals about how the world works from very early on.

→ This article is part of a series on 10 crucial developmental psychology studies:

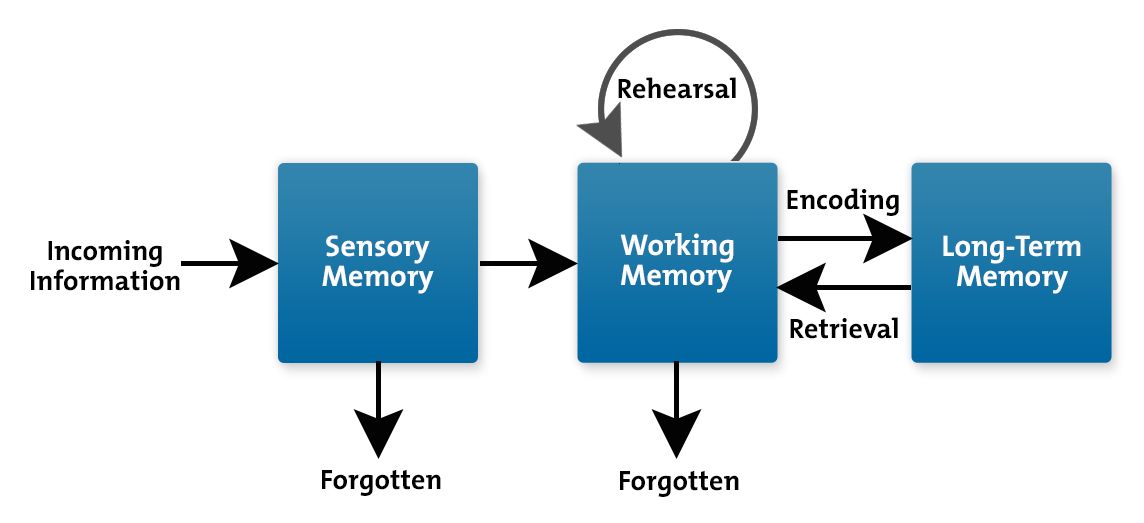

- When infant memory develops

- How self-concept emerges in infants

- How children learn new concepts

- The importance of attachment styles

- When infants learn to imitate others

- Theory of mind reveals the social world

- Understanding object permanence

- How infants learn their first word

- The six types of play

- Piaget’s stages of development theory

.

Facts About Object Permanence in Babies

Written by WebMD Editorial Contributors

In this Article

- What Is Object Permanence, and Why Is It Important?

- When Does Object Permanence Occur?

- What Can You Do to Help Your Baby Develop Object Permanence?

- What Happens After Object Permanence Develops?

- Object Permanence Is an Important Milestone

If you’ve ever played peekaboo with your little one, you’ve helped them work on object permanence. Your baby is learning that people and objects exist even when they can’t see or hear them. Object permanence is one of the development milestones that your infant will learn during their first year of life.

What Is Object Permanence, and Why Is It Important?

Object permanence involves understanding that items and people still exist even when you can’t see or hear them. This concept was discovered by child psychologist Jean Piaget and is an important milestone in a baby's brain development.

Before your baby develops object permanence, things that leave their sight are gone and don’t exist from their point of view. For example, you may notice that when your infant drops a loved toy out of view, they don't look around to find it. Once they start developing object permanence, they will begin to look for the item or express their unhappiness that they don’t have it.

Developing object permanence is important because it’s the first step to other types of symbolic understanding and reasoning, such as pretend play, memory development, and language development. This concept of things and people in their world having permanence is also important for their emotional development, including developing attachments.

When Does Object Permanence Occur?

Research by Jean Piaget suggests object permanence develops when a baby is around eight months old. According to Piaget’s stages of development, object permanence is the main goal for the sensorimotor stage.

However, more recent research shows that babies start to understand object permanence between four and seven months of age.

This development milestone takes time for your baby to understand and doesn’t occur overnight. Your baby also may enjoy engaging in activities that involve object permanence on some days and not others. This change is common.

What Can You Do to Help Your Baby Develop Object Permanence?

Playing games like peekaboo is a fun way to help your baby practice this cognitive skill. Activities, books, and games that involve things that are hidden that then appear are good choices to help develop object permanence. These games can also help your baby start to understand that even when objects or people go away for a little while, they will be back.

Here are some games you can play with your baby that help them strengthen their object permanence.

- Classic peekaboo. You first cover your face with your hands, then remove your hands and say cheerfully, “Peekaboo!”

- Peekaboo variation. Put a light cloth over your head and then remove it, saying “Peekaboo!” As your baby gets a little older, you can see if they will remove the cloth from your head.

- Peekaboo with a toy. Using one of your baby’s toys, hold it behind you or an object and then make it appear.

- Hiding and finding toys. While your baby is watching, place several layers of cloth over a favorite toy. When you’re done, encourage your baby to find the toy. As your baby learns to crawl, you can hide a few toys around the room. Let them watch you hide them. Then encourage them to find the toys as you stay by your child.

Pop-up toys and books. These types of toys have the toy hidden from sight until the object pops up, and there are books with flaps you or your child can raise to show the hidden image.

What Happens After Object Permanence Develops?

Watching your baby’s delight when they find a hidden toy or play peekaboo is exciting and fun. Yet, as your baby learns object permanence, you may notice other changes in their behavior like separation anxiety.

Separation anxiety is a common part of the development process for infants and toddlers. During this phase, they may be afraid or nervous when they are separated from a parent or caregiver and may cry when you leave.

During this phase, they may be afraid or nervous when they are separated from a parent or caregiver and may cry when you leave.

These behaviors start to happen because now your baby knows you exist even if they can’t see you, and they aren’t happy that you’re not with them. This stage is temporary. With time, you’ll be able to step away from your baby without them crying.

Object Permanence Is an Important Milestone

Understanding that people and items still exist even when they aren’t in view is an important concept that your baby will learn during their first year of life. But don’t worry — your little one will delight in activities related to object permanence even after they’ve mastered this milestone.

So enjoy playing peekaboo together. Playing these and other object permanence games will help your baby's developing brain learn.

what supports our identity? — Monoclair

Headings : Translations, Latest articles, Philosophy

Did you find something useful here? Help us stay free, independent, and free by making any donation or purchasing some of our literary merchandise.

The phenomenon of becoming a person and being oneself excited many philosophers and thinkers - from Plotinus to Nietzsche and Foucault. What does it mean to become who you are? Can the different situations we face in life make us a “different person”? Or do they just highlight those facets of our "I" that for the time being were hidden from us? What then is the role of changes in the formation of our identity, and can these changes be purposeful? We are publishing a translation of the long read, in which the philosopher, Yale University graduate student Kevin Tobia, is looking for answers to these questions. nine0009

“It has been six years since I discovered that my son was using drugs. I was very sad all the time and devastated, not to mention how worried I was about his well being. My son was no longer the same person,” Vincenzina Urzia writes in Anthony and Me (2014), in which she talks about her son’s drug addiction.

The puzzle here is that someone can become "not the same person. " The phrase is like a philosophical statement, perhaps even an absurdity. At the same time, the very idea that we might stop recognizing someone we used to know is striking. Many of us have experienced situations when, under the influence of strong changes, a person began to seem completely different. nine0003

" The phrase is like a philosophical statement, perhaps even an absurdity. At the same time, the very idea that we might stop recognizing someone we used to know is striking. Many of us have experienced situations when, under the influence of strong changes, a person began to seem completely different. nine0003

Drug addiction vividly illustrates this phenomenon of alienation: the mother sees that addiction turns her son into a shadow of his former self. Other examples may evoke the same feeling. The rupture of relations changes the partner so much that he seems to become a different person. The same applies to Alzheimer's disease, which affects up to half of older Americans. A parent or relative develops a severe form of Alzheimer's and it seems like the person we once knew has disappeared. A variety of situations lead to profound changes, which sometimes make someone else out of well-known friends or relatives. nine0003

These examples show how some changes can disturb our sense of self. However, there are changes that do not affect our identity. What's more, some profound changes seem to be forcing us to become truly ourselves. Think about finding your true self in romantic love, discovering a hidden passion in life, trying to drastically improve your health, and experiencing a religious or spiritual conversion. The same effect can occur in more difficult cases, such as surviving a period of war or imprisonment. All this leads to huge transformations, but they do not threaten identity. On the contrary, these changes seem to bring out our selves, forcing us to become who we really are. This allows us to make a seemingly paradoxical statement: paradigm, in which a person continues to be the same person, includes the formation and interaction of radical changes.

However, there are changes that do not affect our identity. What's more, some profound changes seem to be forcing us to become truly ourselves. Think about finding your true self in romantic love, discovering a hidden passion in life, trying to drastically improve your health, and experiencing a religious or spiritual conversion. The same effect can occur in more difficult cases, such as surviving a period of war or imprisonment. All this leads to huge transformations, but they do not threaten identity. On the contrary, these changes seem to bring out our selves, forcing us to become who we really are. This allows us to make a seemingly paradoxical statement: paradigm, in which a person continues to be the same person, includes the formation and interaction of radical changes.

This idea of the need for change to maintain our "self" can be clarified by resorting to a philosophical thought experiment. Think of yourself as a newborn. Fifteen years after you were born, your friends and relatives saw a man who looked nothing like a newborn. This teenager had a bigger body, a sharper mind, deeper values, and a richer social life. In many of these important ways, this teenager would be nothing like a small child. But the two would certainly be the same person. You are hardly expected to be the same as a newborn. In fact, in order for you to be the same person, there are actually many aspects in which you must differ from a newborn over time. nine0003

This teenager had a bigger body, a sharper mind, deeper values, and a richer social life. In many of these important ways, this teenager would be nothing like a small child. But the two would certainly be the same person. You are hardly expected to be the same as a newborn. In fact, in order for you to be the same person, there are actually many aspects in which you must differ from a newborn over time. nine0003

Philosophy often emphasizes the importance of being oneself in spite of change. She asks how various changes, such as complete memory loss or a brain transplant, can create a different person. This helps clarify aspects of personal identity and self, but also obscures the idea of the meaning of the change itself. The ideal way to maintain the unity of your existence in time is not to remain exactly the same. Instead, you need to change.

See also

- Ecce Homo: Nietzsche's psychology, or how to become yourself

- Descartes was wrong: a person is aware of himself through the Other

- "Meeting with oneself involves meeting one's own shadow": Valery Leybin on the shadow side of personality

◊ ◊ ◊

The meaning of change is not limited to how we talk about personal identity. Various practical problems are based on assumptions not of a static but of a changing self. For example, a custodial account opened for a young child suggests that the adult beneficiary will be very different from that child. On the other hand, the money in this account is for a person who will be like this little child in many ways, but it is not for someone with the linguistic, mental, and moral abilities of a little child. Many long-term liabilities share this approach. They are based on expected changes or developments, not exact similarities. nine0003

Various practical problems are based on assumptions not of a static but of a changing self. For example, a custodial account opened for a young child suggests that the adult beneficiary will be very different from that child. On the other hand, the money in this account is for a person who will be like this little child in many ways, but it is not for someone with the linguistic, mental, and moral abilities of a little child. Many long-term liabilities share this approach. They are based on expected changes or developments, not exact similarities. nine0003

Philosophers point out cases where change causes practical problems. For example, it may seem that certain personal changes require breaking promises seemingly made to another person. But in the case of a custodial account, we seem to be more concerned about the appropriateness of issuing funds from that account if the adult is like a child than if it is too different. The implicit conditions underlying these judgments are not just static similarities, but assumed changes over time. nine0003

nine0003

What changes contribute to such ideal transformations - according to a certain model? These essential changes are not arbitrary. In our thought experiment, changes were taken into account that indicated the purposeful development of the newborn. This thought experiment exemplifies the steady change that is consistent with personal identity and is fundamental to the self. We certainly would not encourage a teenager to strive for an exact resemblance to a newborn for fear of losing their true identity. Part of what it means for a teenager to be the same person as a newborn is a significant and purposeful transformation through the learning of language, the acquisition of social norms and moral rules. nine0003

Everyday life offers numerous examples of identity preservation and purposeful change. Sometimes big changes address the essence of a person or his deepest self. New relationships, career successes, or new hobbies inevitably change us, but they do so in accordance with our self-description. These changes do not make us appear "less than ourselves." Instead, these changes seem to help us become who we are .

These changes do not make us appear "less than ourselves." Instead, these changes seem to help us become who we are .

The history of philosophy encourages us to purposefully change our "I". The ancient Greek philosopher Plotinus referred to the image of the statue. He calls us

“Cut off everything that is excessive, straighten everything that is crooked, illuminate everything that is dim, work to make everything a radiance of beauty. Never stop working on a statue until the divine light of virtue has been shed upon you.”

Purposeful self-change is not a problem of personal identity. Rather, it reveals the facets of the true "I".

A few centuries earlier, the Chinese philosopher Mencius described people as farmers, cultivating the seeds of their virtue. If we grow up into good people, it means that we have grown in the right direction, cultivating our seeds of virtue. It is important that we are born like seeds and not like mature trees of our virtue. We are not born absolutely good, keeping our virtue unchanged. On the contrary, we are born as simple seeds of virtue that will flourish through development. nine0003

We are not born absolutely good, keeping our virtue unchanged. On the contrary, we are born as simple seeds of virtue that will flourish through development. nine0003

Similar ideas are repeated throughout the history of philosophy. In Ecce Homo, Friedrich Nietzsche describes the phenomenon of becoming who you are:

“Becoming who you are essentially assumes that you have no idea who you are… the organizing, dominating ‘idea’ continues to grow deep within… before giving any hint of an overarching goal, a ‘goal’ , "meaning"".

And in the interview "On the Genealogy of Morals" Michel Foucault remarks that:

"We must create ourselves as a work of art."

My essay draws inspiration from these statements, even though each of them remains the subject of debate. The main idea is that, in contrast to the notion that our identity is associated with permanence or similarity, in fact, "I" is an organic and dynamic phenomenon. Being the same person across time is not about trying to hold on to every aspect of our current selves, but about purposeful change. nine0077

Being the same person across time is not about trying to hold on to every aspect of our current selves, but about purposeful change. nine0077

◊ ◊ ◊

The common feature of all these historical views is the vision of something deep within, whether it be the image of a statue, a seed of virtue, or a guiding idea to "become who you are." This reveals an important insight about purposeful development. With the right development, the future self will not be exactly the same as the current self. Instead, the future self must purposefully evolve and thus become a different version of the present self. And often the future self will be a flourishing or flourishing version of an earlier self that contained small seeds or hints of the future. nine0003

Understanding this kind of change requires broader thinking. What does it mean to purposefully develop? Human goals are complex, so let's look at the goal of something simpler first. Let's take a stomach. The purpose of the acorn is to become an oak tree. We could attribute this purpose to individual acorns in different ways. For example, since we know that acorns usually grow into oak trees, it would seem that each of the acorns could have such a purpose. But we also attribute goals retrospectively. Having seen how an unknown object turns into an oak, we can go back and attribute the transformation into an oak as the goal of this object. Moreover, once we know that a particular acorn has grown into a very tall oak tree, we can go back in time and think that becoming a very tall oak tree is the more specific purpose of that acorn. nine0003

We could attribute this purpose to individual acorns in different ways. For example, since we know that acorns usually grow into oak trees, it would seem that each of the acorns could have such a purpose. But we also attribute goals retrospectively. Having seen how an unknown object turns into an oak, we can go back and attribute the transformation into an oak as the goal of this object. Moreover, once we know that a particular acorn has grown into a very tall oak tree, we can go back in time and think that becoming a very tall oak tree is the more specific purpose of that acorn. nine0003

However, the human goals of a person are wider than the development of language and values, becoming a social and moral being. But there are some similarities with the acorn. We study many of the apparent purposes of humans through theory. Humans usually develop language and morality, and so it seems that newborns also have this purpose, even when the newborns themselves do not exhibit any linguistic or moral behavior. The same reasoning can be applied to more individualized goals. Perhaps, having learned that a particular child has developed into a great athlete, we might even look back and think that such a specific goal was noticeable in a small child who had not yet manifested such traits and tendencies. It seems to us that the main aspects of personal identity can be traced even in youth. nine0003

The same reasoning can be applied to more individualized goals. Perhaps, having learned that a particular child has developed into a great athlete, we might even look back and think that such a specific goal was noticeable in a small child who had not yet manifested such traits and tendencies. It seems to us that the main aspects of personal identity can be traced even in youth. nine0003

This notion of a dynamic and purposive self is at odds with the focus of some discussions of personal identity. This debate is centered on the immutability under change, and is based on the idea that immutability implies similarity with something. In a broad sense, this notion of purposefulness suggests similarity—an identical purpose throughout life, but, as Nietzsche notes, the purpose is often hidden. Often we have no idea who we are until we become it. nine0003

Interest in the problem of not knowing who we are or who we will become initiates philosophical discussions about "transformational experiences". It's an experience that changes a person in fundamental and unpredictable ways: having a baby, serving in the military, starting a new career, going to jail or falling in love. Decisions to gain such experience pose a problem for decision theory. How can we appreciate what we do not know? Of course, we can evaluate some uncertain solutions. While I have never tried tequila or the Twinky Diet, I conclude that this is probably a poor choice. But other unknown decisions are harder to assess, because the person I would become by virtue of my decision is in some fundamental way different from my current self. For example, the arrival of a child can lead to such profound personal changes that it is difficult to even evaluate this decision. The list of pros and cons from my current perspective does not seem to adequately reflect this decision, as the "me" that emerges as a response to having a baby may be radically different from my current self. nine0003

It's an experience that changes a person in fundamental and unpredictable ways: having a baby, serving in the military, starting a new career, going to jail or falling in love. Decisions to gain such experience pose a problem for decision theory. How can we appreciate what we do not know? Of course, we can evaluate some uncertain solutions. While I have never tried tequila or the Twinky Diet, I conclude that this is probably a poor choice. But other unknown decisions are harder to assess, because the person I would become by virtue of my decision is in some fundamental way different from my current self. For example, the arrival of a child can lead to such profound personal changes that it is difficult to even evaluate this decision. The list of pros and cons from my current perspective does not seem to adequately reflect this decision, as the "me" that emerges as a response to having a baby may be radically different from my current self. nine0003

A possible answer to these problems comes from an intuition about the meaning of personal change. The key to understanding is our belief in the goal. Remember how we talked about the acorn, which should turn into an oak tree. In the same way, we understand that a newborn person must develop, grow, become wiser, morally and socially prepared. Language acquisition transforms our experience, but we have no doubt that it is an experience that preserves and enriches identity, and does not upset identity or destroy the true self. Radical changes, such as learning a language, develop us into the people we really should be, although the personalities we become are shaped in different ways. nine0077

The key to understanding is our belief in the goal. Remember how we talked about the acorn, which should turn into an oak tree. In the same way, we understand that a newborn person must develop, grow, become wiser, morally and socially prepared. Language acquisition transforms our experience, but we have no doubt that it is an experience that preserves and enriches identity, and does not upset identity or destroy the true self. Radical changes, such as learning a language, develop us into the people we really should be, although the personalities we become are shaped in different ways. nine0077

◊ ◊ ◊

However, humans are very different from plants and other animals. Our apparent goals are wider than those given by nature or even culture. While the acorn's sole purpose is to grow into an oak tree, humans are creatures of many and varied possibilities. This implies the exciting but dangerous aspect of self-goal setting. Often, who we think we are now becomes more understandable over time. To clarify this property, consider examples of great achievements. Imagine that a small child grows into a great artist. In this case, we reflect on the past and see the seeds of genius in the child. This opinion may be a mistake or a bias; perhaps that was not his intention. But, undoubtedly, this is a common story that we tell. nine0003

To clarify this property, consider examples of great achievements. Imagine that a small child grows into a great artist. In this case, we reflect on the past and see the seeds of genius in the child. This opinion may be a mistake or a bias; perhaps that was not his intention. But, undoubtedly, this is a common story that we tell. nine0003

Whether this story is right or wrong, it seeps into our morality. Philosopher Bernard Williams presented an imaginary thought experiment about Paul Gauguin inspired by the real life of the artist. In a thought experiment, young Gauguin decides to leave his family for his artistic ambitions. As Williams astutely noted, the evaluation of young Gauguin's choice may depend on the randomness of its outcome. Philosophers call this phenomenon "moral luck." If the old Gauguin fails as an artist, the young Gauguin will be blameworthy. But if the old Gauguin succeeds, we will say, as Williams did in Moral Fortune (perhaps a little reluctantly): "Well, it worked out, then well done. " Another way to tell this story is to try to see it in terms of the true self and the undoubted goals of the young Gauguin. Seeing the old Gauguin, a successful artist, we immediately attribute the seeds of artistic potential to the young Gauguin. In a hypothetical world in which old Gauguin fails, we fear that a young man who left his family years ago has drifted away from his moral and family goals (as we now realize he really had no artistic talent). nine0003

" Another way to tell this story is to try to see it in terms of the true self and the undoubted goals of the young Gauguin. Seeing the old Gauguin, a successful artist, we immediately attribute the seeds of artistic potential to the young Gauguin. In a hypothetical world in which old Gauguin fails, we fear that a young man who left his family years ago has drifted away from his moral and family goals (as we now realize he really had no artistic talent). nine0003

In interpreting "I" through purposefulness, there is an additional argument in light of the discovery of a philosophical experiment: we tend to see improvements in the permanence of our identity rather than its destruction. People rate change for the better as being more aligned with identity than change for the worse. The purposeful interpretation hypothesis is that change for the better shapes our impression of a person's past experience. When we see someone improving, we attribute that value to the potentiality of their earlier self. nine0003

nine0003

Seeing the growth of a magnificent oak, we will be more certain that it must have been planted in the acorn. And, having seen a positive strong change in a person, we think with greater confidence about that part of his true "I", which preceded the improvement in time. However, seeing the deterioration of a person's condition, we fear that he has departed from his real calling.

Understanding the self in terms of purposefulness also explains the limit of this idea: not all improvements appear to be identity preservation. We do not perceive any improvement as part of self-development. As Aristotle noted, and Martha Nussbaum elaborated, we would not want our friends to become gods because we would lose them. Extraordinary and unusual changes - even changes for the better - can make someone seem like a different person. An acorn that magically turns into an apple is no longer the same, just as a person who magically turns into a god is no longer the same. Man may remain through great transformations as a speaking, moral and social being, an artist or an athlete, but not as a god. nine0003

nine0003

While this idea of purposeful and sustainable being answers some philosophical riddles, we can object to its relentless naturalistic premise. Becoming communicative and social beings is a meaningful transformational experience, but what about children? It is not obvious that by abandoning this explicit naturalistic goal, we cannot become truly ourselves. What about a cochlear implant in a deaf person - does this choice take him away from his true self? Talking about the "goal" of a person has a detrimental effect when talking about different ways of being. Typical or "natural", according to most, purposeful changes do not necessarily correspond to the true "I" of each person. nine0003

Our insights into human goals raise deep and problematic questions. What makes us distinguish goals? What are the goals of different people? Moreover, all the discussion so far has been about obvious goals. But are these "goals" real or illusory? If they are real, do they really have to do with personal identity or true self? Or maybe we remain ourselves, even if we do not achieve these goals?

This leaves us in a difficult position. Our conceptions of identity and self are entangled in webs of goal bias. Of course, understanding yourself as a dynamic and purposeful self provides clarity in understanding. As opposed to a static view of identity, we should support some kind of developmental model and identity criteria, at least those that our moral and social development recognizes. Not all changes threaten our identity, and we should accept the meaning of a purposeful change in our self. But we must also be careful about unconscious teleological reasoning. nine0003

Our conceptions of identity and self are entangled in webs of goal bias. Of course, understanding yourself as a dynamic and purposeful self provides clarity in understanding. As opposed to a static view of identity, we should support some kind of developmental model and identity criteria, at least those that our moral and social development recognizes. Not all changes threaten our identity, and we should accept the meaning of a purposeful change in our self. But we must also be careful about unconscious teleological reasoning. nine0003

Despite these questions about the boundaries of identity and self goals, for the moment these reflections substantiate the modern model of morality. Since the mysteries of personal identity emphasize the importance of the integrity of the self despite change - for example, while maintaining the same body or mind - we should also remember the vital role of change itself. Every mundane example of a continuous personal identity involves huge transformations, whether it be the acquisition of a language, social and moral norms, an encounter with a hidden passion, an exposure, a change of profession, the beginning or end of a love relationship, the creation or search for a family. However, this dynamic does not call into question our identity. These changes represent one of the most significant aspects of our self. nine0003

However, this dynamic does not call into question our identity. These changes represent one of the most significant aspects of our self. nine0003

See also

- What is your story? The Psychological Power of Narrative

- Ecce Homo: Nietzsche's psychology, or how to become yourself

Source: Change becomes you / Aeon

Cover: Paul Gauguin, Grotesque Self Portrait (1889) / National Gallery of Art, Washington / Wikipedia

If you find an error, please select a piece of text and press Ctrl+Enter .

identitytranslationspsychologyphilosophy

similar articles

,000 Topic 2: Initial chemical ideas- Video

- Simulator

- Theory

Spotted a mistake?

Discovery of the law of the constancy of the composition of substances

Scientists of the XVII-XVIII centuries. many quantitative measurements were carried out, including by determining the mass fraction of an element in a substance. But the results of their experiments were inaccurate, and as a result, did not match. nine0003

many quantitative measurements were carried out, including by determining the mass fraction of an element in a substance. But the results of their experiments were inaccurate, and as a result, did not match. nine0003

The French chemist Claude Louis Berthollet tried to prove that the composition of substances depends on the proportions in which the reactants are found.

Fig. 1. Claude Louis Berthollet

In contrast to him, another French chemist Joseph Louis Proust conducted many experiments to study the composition of various substances and concluded that the composition of a substance is constant.

Fig. 2. Joseph Louis Proust

In 1808, Proust formulated law of constancy of the composition of substances : " Substances have a constant composition, regardless of the method and place of their receipt."

The essence of the law

In his study of copper in 1799, Proust showed that natural copper carbonate and copper carbonate obtained by chemists in the laboratory have the same composition.

There is no difference between the water flowing from our tap, the water from the spring, or the water obtained synthetically (meaning the composition of the pure substance - water, and not the composition of the mixture). Water will always contain, by mass, 11.1% hydrogen and 88.9% oxygen.

But nature is much more diverse than any theory created by man. And there are exceptions to the law of the constancy of the composition of substances. In the 20th century, it was discovered that some compounds do not have a permanent composition.

Limitation of the law

Thus, it cannot be said that Claude Berthollet was absolutely wrong. The law of the constancy of the composition of substances has limitations.

Substances with a variable composition exist, they were named after Berthollet - berthollides. nine0003

Bertollides are compounds of variable composition that do not obey the laws of constant and multiple ratios. Bertollides are non-stoichiometric binary compounds of variable composition, which depends on the method of preparation. Numerous cases of the formation of berthollides have been discovered in metal systems, as well as among oxides, sulfides, carbides, hydrides, etc. For example, vanadium(II) oxide may have, depending on the conditions of preparation, the composition from V 0.9 to V 1, 3 . nine0003

Bertollides are non-stoichiometric binary compounds of variable composition, which depends on the method of preparation. Numerous cases of the formation of berthollides have been discovered in metal systems, as well as among oxides, sulfides, carbides, hydrides, etc. For example, vanadium(II) oxide may have, depending on the conditions of preparation, the composition from V 0.9 to V 1, 3 . nine0003

List of recommended literature

- Collection of tasks and exercises in chemistry: 8th grade: to the textbook by P. A. Orzhekovsky and others "Chemistry, grade 8" / P. A. Orzhekovsky, N. A Titov, F. F. Hegele. - M.: AST: Astrel, 2006. (p. 25-28)

- Ushakova O. V. Chemistry workbook: 8th grade: to the textbook by P. A. Orzhekovsky and others “Chemistry. Grade 8» / O. V. Ushakova, P. I. Bespalov, P. A. Orzhekovsky; under. ed. prof. P. A. Orzhekovsky - M .: AST: Astrel: Profizdat, 2006. (p. 21-23)

- Chemistry: 8th grade: textbook.

for general institutions / P. A. Orzhekovsky, L. M. Meshcheryakova, L. S. Pontak. M.: AST: Astrel, 2005. (§9)

for general institutions / P. A. Orzhekovsky, L. M. Meshcheryakova, L. S. Pontak. M.: AST: Astrel, 2005. (§9) - Chemistry: inorg. chemistry: textbook. for 8 cells. general institutions / G. E. Rudzitis, F. G. Feldman. - M .: Education, JSC "Moscow textbooks", 2009. (§§10,14)

- Encyclopedia for children. Volume 17. Chemistry / Chapter. ed. V. A. Volodin, lead. scientific ed. I. Leenson. – M.: Avanta+, 2003.

More Web Resources

- United collection of digital educational resources (Source)

- Electronic version of the journal "Chemistry and Life" (Source)

- Chemistry tests (online) (Source)

Homework

p. 22-23 No. 3, 7 from the Workbook in Chemistry: 8th grade: to the textbook by P. A. Orzhekovsky and others “Chemistry. Grade 8» / O. V. Ushakova, P. I. Bespalov, P. A. Orzhekovsky; under. ed. prof. P. A. Orzhekovsky. - M.: AST: Astrel: Profizdat, 2006.