The bystander effect definition

Bystander Effect | Psychology Today

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

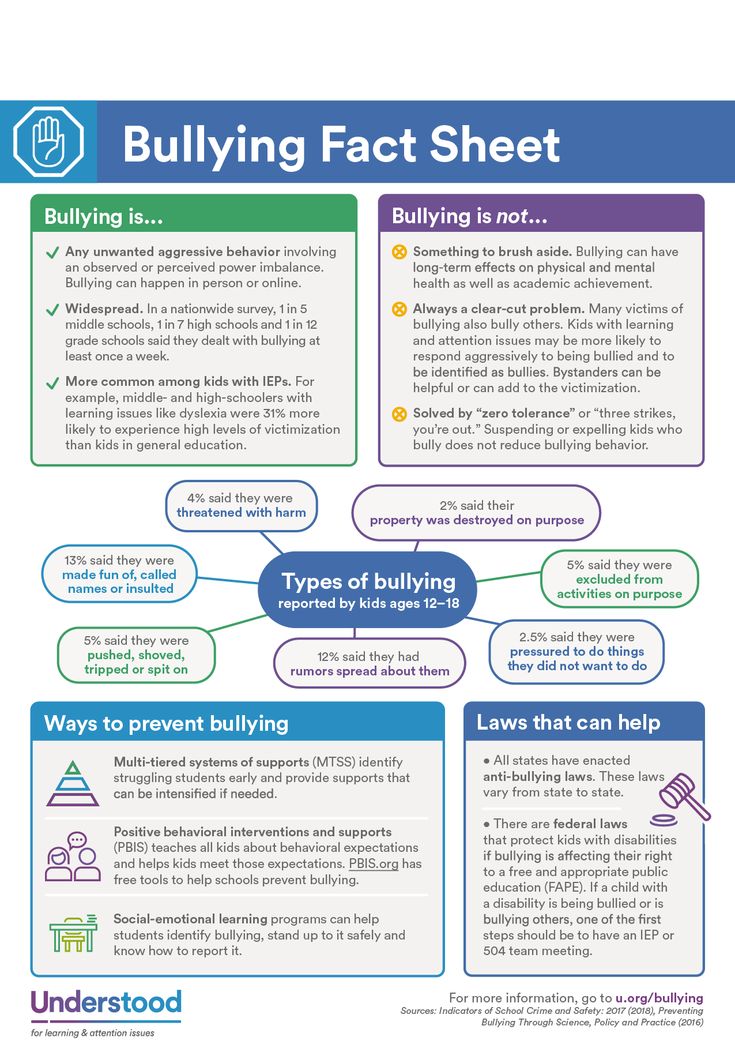

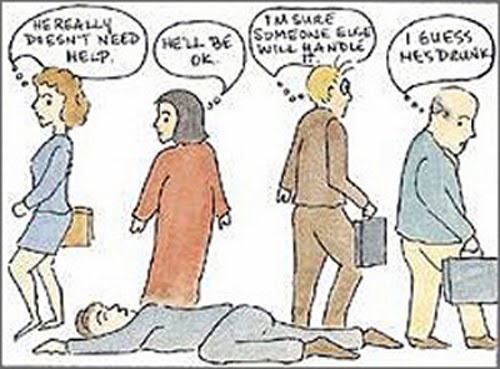

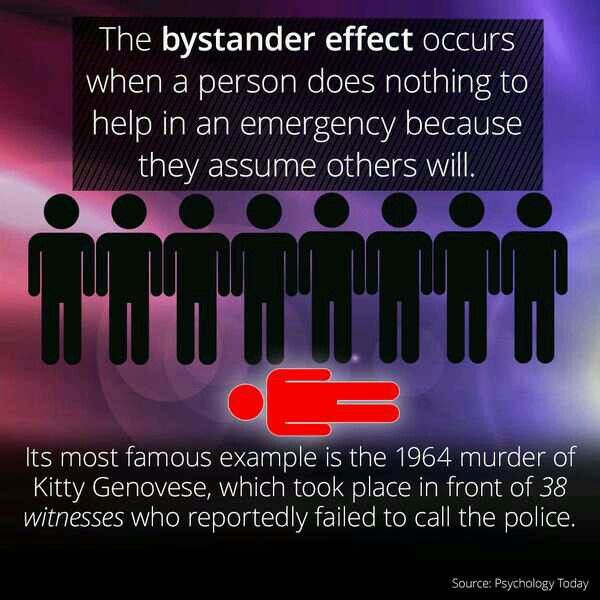

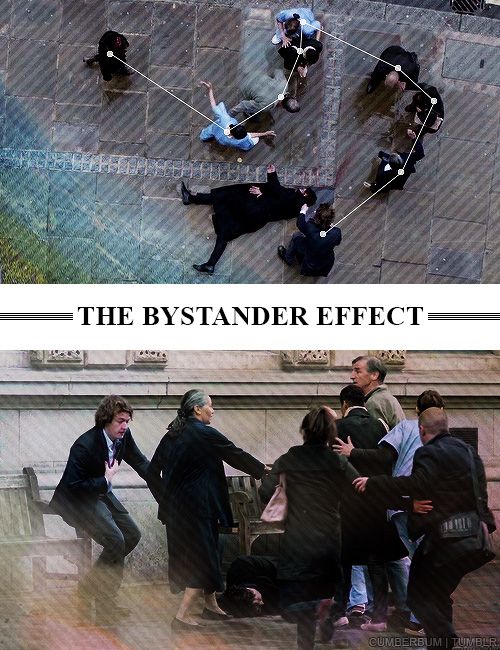

The bystander effect occurs when the presence of others discourages an individual from intervening in an emergency situation, against a bully, or during an assault or other crime. The greater the number of bystanders, the less likely it is for any one of them to provide help to a person in distress. People are more likely to take action in a crisis when there are few or no other witnesses present.

Contents

- Understanding the Bystander Effect

- Be an Active Bystander

Understanding the Bystander Effect

Social psychologists Bibb Latané and John Darley popularized the concept of the bystander effect following the infamous murder of Kitty Genovese in New York City in 1964.

The 28-year-old woman was stabbed to death outside her apartment; at the time, it was reported that dozens of neighbors failed to step in to assist or call the police.

Latané and Darley attributed the bystander effect to two factors: diffusion of responsibility and social influence. The perceived diffusion of responsibility means that the more onlookers there are, the less personal responsibility individuals will feel to take action. Social influence means that individuals monitor the behavior of those around them to determine how to act.

Why do people fail to help in an emergency?

It’s natural for people to freeze or go into shock when seeing someone having an emergency or being attacked. This is usually a response to fear—the fear that you are too weak to help, that you might be misunderstanding the context and seeing a threat where there is none, or even that intervening will put your own life in danger.

What situational factors contribute to the bystander effect?

It can be hard to tease out the many reasons people fail to take action, but when it comes to sexual assault against women, research has shown that witnesses who are male, hold sexist attitudes, or are under the influence of drugs or alcohol are less likely to actively help a woman who seems too incapacitated to consent to sexual activity.

Can the bystander effect ever be positive?

The same factors that lead to the bystander effect can be used to increase helping behaviors. Individuals are more likely to behave well when they feel themselves being watched by “the crowd,” and when their actions align with their social identities. For example, someone who identifies as pro-environment will take more effort to recycle when they believe they are being observed.

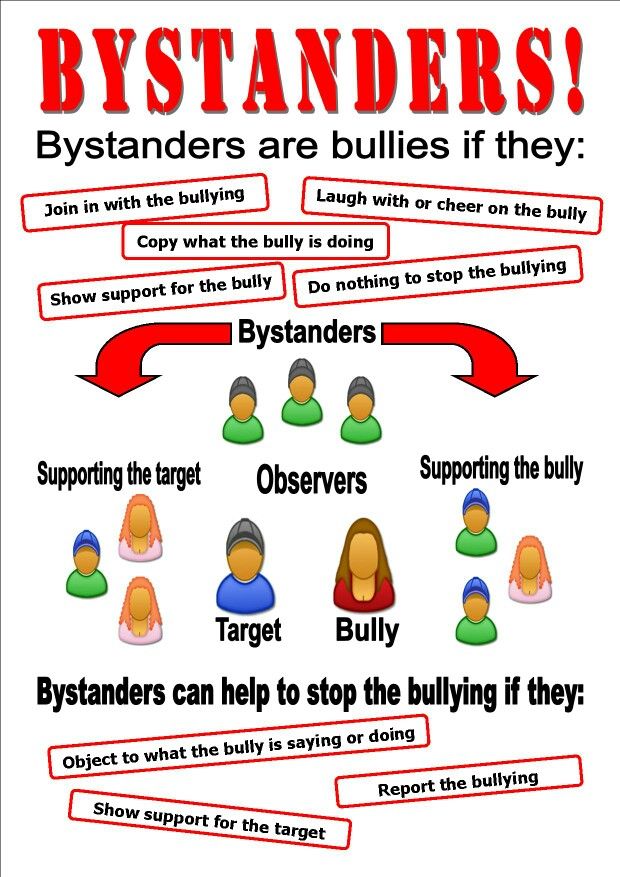

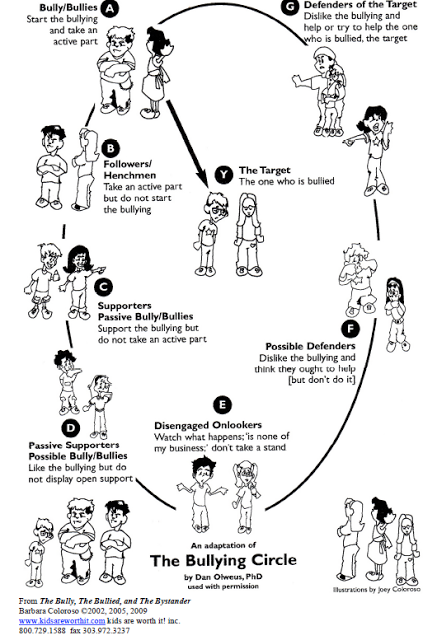

What makes bystanders more likely to intervene against bullying?

Good people can be complicit in bad behavior (hence the common “just following orders” excuse). Someone who speaks up against bullying is called an “upstander.” Upstanders have confidence in their judgment and values and believe their actions will make a difference. They are more likely to do the right thing because they take the time to stop and think before acting.

Someone who speaks up against bullying is called an “upstander.” Upstanders have confidence in their judgment and values and believe their actions will make a difference. They are more likely to do the right thing because they take the time to stop and think before acting.

How to Be an Active Bystander

The intervention of bystanders is often the only reason why bullying and other crimes cease. The social and behavioral paralysis described by the bystander effect can be reduced with awareness and, in some cases, explicit training. Secondary schools and college campuses encourage students to speak up when witnessing an act of bullying or a potential assault.

One technique is to behave as if one is the first or only person witnessing a problem. Often, when one person takes action, if only to shout, "Hey, what's going on?" or "The police are coming," others may be emboldened to take action as well. That said, an active bystander is most effective when they assume that they themselves are the sole person taking charge; giving direction to other bystanders to assist can, therefore, be critically important.

How can you avoid being a passive bystander?

Don’t expect others to be the first to act in a crisis—just saying “Stop” or “Help is on the way” can prevent further harm. Speak up using a calm, firm tone. Give others directions to get them involved in helping too. Do your best to ensure the safety of the victim, and don’t be afraid to seek assistance when you need it.

Is it wrong not to help in an emergency?

If a bystander can help someone without risking their own life and chooses not to, they are usually considered morally guilty. But the average person is typically under no legal obligation to help in an emergency. However, some places have adopted duty-to-rescue laws, making it a crime not to help a person in need.

Is there a legal risk if you do try to help someone?

Yes, some people can be held legally responsible for negative outcomes if they get involved. Fear of legal consequences can be a major contributor to the bystander effect. Some jurisdictions have passed Good Samaritan laws as encouragement for bystanders to act, offering legal protection to those trying to help victims. However, these laws are often limited.

Fear of legal consequences can be a major contributor to the bystander effect. Some jurisdictions have passed Good Samaritan laws as encouragement for bystanders to act, offering legal protection to those trying to help victims. However, these laws are often limited.

How can you overcome the bystander effect?

When training yourself to be an active bystander, it helps to cultivate qualities like empathy. Try to see the situation from the victim’s perspective. Worry less about the consequences of helping and more about the example you are setting for future generations. If you are the victim, pick out one person in the crowd and make eye contact. People’s natural tendencies towards altruism may move them to help if given the chance.

Essential Reads

Recent Posts

bystander effect | Britannica

- Related Topics:

- altruistic behaviour human social behaviour

See all related content →

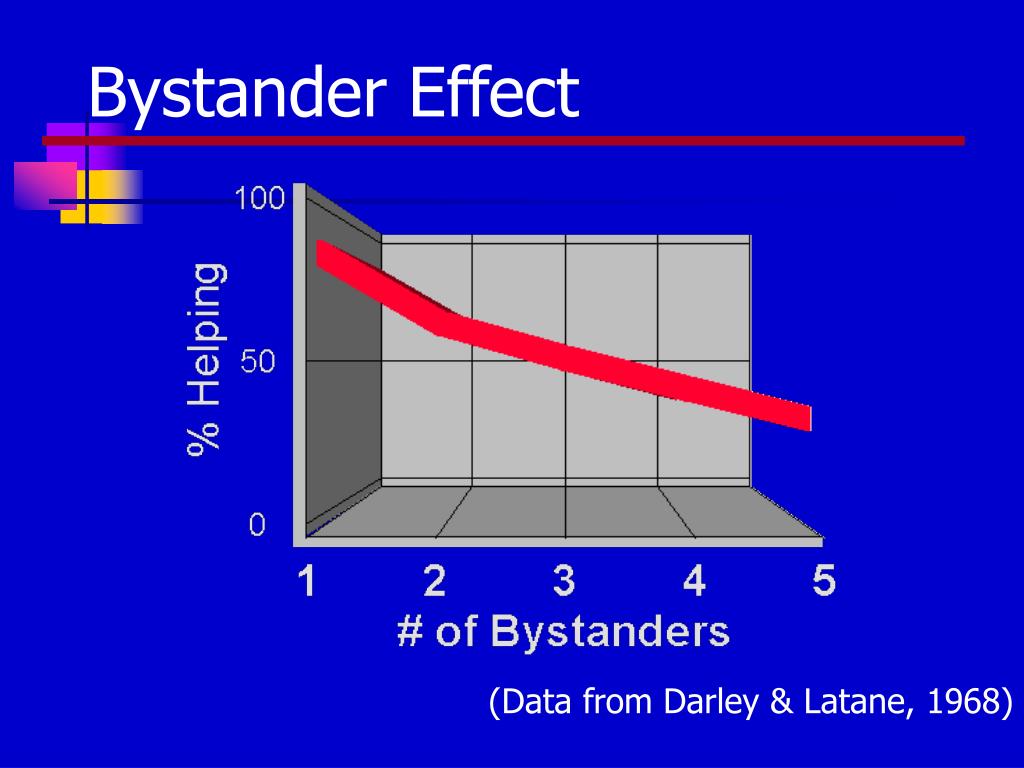

bystander effect, the inhibiting influence of the presence of others on a person’s willingness to help someone in need. Research has shown that, even in an emergency, a bystander is less likely to extend help when he or she is in the real or imagined presence of others than when he or she is alone. Moreover, the number of others is important, such that more bystanders leads to less assistance, although the impact of each additional bystander has a diminishing impact on helping.

Research has shown that, even in an emergency, a bystander is less likely to extend help when he or she is in the real or imagined presence of others than when he or she is alone. Moreover, the number of others is important, such that more bystanders leads to less assistance, although the impact of each additional bystander has a diminishing impact on helping.

Investigations of the bystander effect in the 1960s and ’70s sparked a wealth of research on helping behaviour, which has expanded beyond emergency situations to include everyday forms of helping. By illuminating the power of situations to affect individuals’ perceptions, decisions, and behaviour, study of the bystander effect continues to influence the course of social psychological theory and research.

Bystander intervention

The bystander effect became a subject of significant interest following the brutal murder of American woman Kitty Genovese in 1964. Genovese, returning home late from work, was viciously attacked and sexually assaulted by a man with a knife while walking home to her apartment complex from a nearby parking lot. As reported in the The New York Times two weeks later, for over half an hour 38 respectable, law-abiding people heard or saw the man attack her three separate times. The voices and lights from the bystanders in nearby apartments interrupted the killer and frightened him off twice, but each time he returned and stabbed her again. None of the 38 witnesses called the police during the attack, and only one bystander contacted authorities after Kitty Genovese died. (In 2016, following the death of the attacker, Winston Moseley, The New York Times published an article stating that the number of witnesses and what they saw or heard had been exaggerated, that there had been just two attacks, that two bystanders had called the police, and that another bystander tried to comfort the dying woman.)

As reported in the The New York Times two weeks later, for over half an hour 38 respectable, law-abiding people heard or saw the man attack her three separate times. The voices and lights from the bystanders in nearby apartments interrupted the killer and frightened him off twice, but each time he returned and stabbed her again. None of the 38 witnesses called the police during the attack, and only one bystander contacted authorities after Kitty Genovese died. (In 2016, following the death of the attacker, Winston Moseley, The New York Times published an article stating that the number of witnesses and what they saw or heard had been exaggerated, that there had been just two attacks, that two bystanders had called the police, and that another bystander tried to comfort the dying woman.)

The story of Genovese’s murder became a modern parable for the powerful psychological effects of the presence of others. It was an example of how people sometimes fail to react to the needs of others and, more broadly, how behavioral tendencies to act prosocially are greatly influenced by the situation. Moreover, the tragedy led to new research on prosocial behaviour, namely bystander intervention, in which people do and do not extend help. The seminal research on bystander intervention was conducted by American social psychologists Bibb Latané and John Darley, who found that bystanders do care about those in need of assistance but nevertheless often do not offer help. Whether bystanders extend help depends on a series of decisions.

Moreover, the tragedy led to new research on prosocial behaviour, namely bystander intervention, in which people do and do not extend help. The seminal research on bystander intervention was conducted by American social psychologists Bibb Latané and John Darley, who found that bystanders do care about those in need of assistance but nevertheless often do not offer help. Whether bystanders extend help depends on a series of decisions.

Bystander decision-making

The circumstances surrounding an emergency in which an individual needs help tend to be unique, unusual, and multifaceted. Many people have never encountered such a situation and have little experience to guide them during the pressure-filled moments when they must decide whether or not to help. Several decision models of bystander intervention have been developed.

According to Latané and Darley, before helping another, a bystander progresses through a five-step decision-making process. A bystander must notice that something is amiss, define the situation as an emergency or a circumstance requiring assistance, decide whether he or she is personally responsible to act, choose how to help, and finally implement the chosen helping behaviour. Failing to notice, define, decide, choose, and implement leads a bystander not to engage in helping behaviour.

Failing to notice, define, decide, choose, and implement leads a bystander not to engage in helping behaviour.

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content. Subscribe Now

In another decision model, bystanders are presumed to weigh the costs and rewards of helping. Bystanders rationalize their decision on the basis of which choice (helping or not helping) will deliver the best possible outcome for themselves. In this model, bystanders are more likely to help when they view helping as a way to advance their personal growth, to feel good about themselves, or to avoid guilt that may result from not helping.

Social influence plays a significant role in determining how quickly individuals notice that something is wrong and define the situation as an emergency. Research has shown that the presence of others can cause diffusion of the responsibility to help. Hence, social influence and diffusion of responsibility are fundamental processes underlying the bystander effect during the early steps of the decision-making process.

Social influence

If a bystander is physically in a position to notice a victim, factors such as the bystander’s emotional state, the nature of the emergency, and the presence of others can influence his or her ability to realize that something is wrong and that assistance is required. In general, positive moods, such as happiness and contentment, encourage bystanders to notice emergencies and provide assistance, whereas negative moods, such as depression, inhibit helping. However, some negative moods, such as sadness and guilt, have been found to promote helping. In addition, some events, such as someone falling down a flight of stairs, are very visible and hence attract bystanders’ attention. For example, studies have demonstrated that victims who yell or scream receive help almost without fail. In contrast, other events, such as a person suffering a heart attack, often are not highly visible and so attract little attention from bystanders. In the latter situations, the presence of others can have a substantial impact on bystanders’ tendency to notice the situation and define it as one that requires assistance.

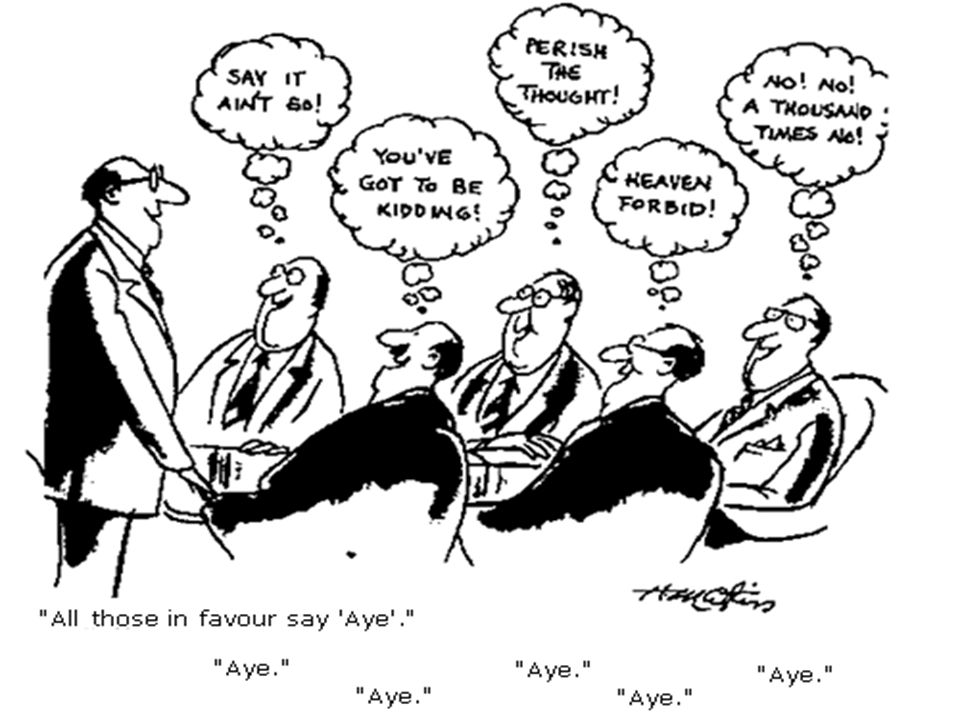

In situations where the need for help is unclear, bystanders often look to others for clues as to how they should behave. Consistent with social comparison theory, the effect of others is more pronounced when the situation is more ambiguous. For example, when other people act calmly in the presence of a potential emergency because they are unsure of what the event means, bystanders may not interpret the situation as an emergency and thus act as if nothing is wrong. Their behaviour can cause yet other bystanders to conclude that no action is needed, a phenomenon known as pluralistic ignorance. But when others seem shocked or distressed, bystanders are more likely to realize an emergency has occurred and conclude that assistance is needed. Other social comparison variables, such as the similarity of other bystanders (e.g., whether they are members of a common in-group), can moderate the extent to which bystanders look to others as guides in helping situations. In sum, when the need for help is unclear, bystanders look to others for guidance. This is not the case when the need for assistance is obvious.

This is not the case when the need for assistance is obvious.

Bystander effect

Imagine the situation: you are walking along a busy street, and then a passer-by not far from you becomes ill. Most likely, you will not help the poor fellow - just as dozens of people around will not help. This does not make you a bad person: in this case, the “witness effect” works, reducing the chances that in a large crowd the victim will receive help in time. Read about this cognitive distortion, as well as about the famous case that happened in 1964 in New York, in our new blog. nine0003

If we talk about the fact that some cognitive distortions can be dangerous in real life, then the "bystander effect" (also known as the "outsider effect", "observer effect" and under any other names - translations of the phrase 'bystander effect' ) is undoubtedly one of them. But it carries a threat not to those who are exposed to it, but to completely random people. This cognitive bias is that a person is less likely to come to the aid of an injured person if there are other people around. nine0003

This cognitive bias is that a person is less likely to come to the aid of an injured person if there are other people around. nine0003

This effect was first described by two American social psychologists, John Darley and Bibb Latane, in 1968. Their scientific article was inspired by an incident in New York four years earlier, and even served as a kind of response to it.

On the evening of March 13, 1964, Kitty Genovese, a resident of the Queens area (the “bystander effect”, by the way, is sometimes also called “Genovese syndrome” - just in honor of her), was attacked: the attacker stabbed the girl twice in the back with a knife. Kitty fought back and screamed, but no one responded to her cries - only one of the residents of the nearest houses shouted out of the window: “Leave the girl alone!”, after which the criminal disappeared for a while. For the next few minutes, Genovese, bleeding to death, tried to find a safe place - and still without anyone's help. Then the attacker again overtook Genovese and inflicted several more blows on her, after which he disappeared. She died from her injuries on the way to the hospital. nine0003

She died from her injuries on the way to the hospital. nine0003

New York in the mid-1960s was not uncommon. However, the murder of Kitty Genovese received a lot of publicity. During the investigation, it turned out that 38 residents of nearby houses were witnesses to the crime (although information about their number is sometimes disputed), so “respectable law-abiding citizens” who ignored the incident were also publicly condemned during the trial. Adding fuel to the fire was a column published in The New York TImes, which reported that none of the alleged witnesses helped Genovese or even reported the incident to the police or an ambulance (with the exception of a man screaming from the window, who temporarily drove the criminal away from the victim). nine0003

During the trial, witnesses gave a variety of reasons for not providing any assistance to Genovese: many said they did not want to intervene (apparently considering what was happening on the street as a normal domestic quarrel or fearing for their own lives), one witness admitted that he was very tired, and another said that he did not know the reason for his inactivity.

In fact, they were led not only by fear and unwillingness to interfere, but also by the presence of other witnesses. Waking up from a loud noise, turning on the light and going to the window, the residents of the houses located near the crime scene saw several other similarly lit windows. Each witness knew they were not alone and could assume that someone else would take responsibility for preventing the murder. nine0003

Many researchers and journalists noted in the years following the murder that the New York Times column on the incident greatly exaggerated the number of witnesses to the crime and their inaction. Nevertheless, the case of Kitty Genovese, even though less controversial than the journalists described, served as the reason for the start of socio-psychological research on the reactions of witnesses to incidents.

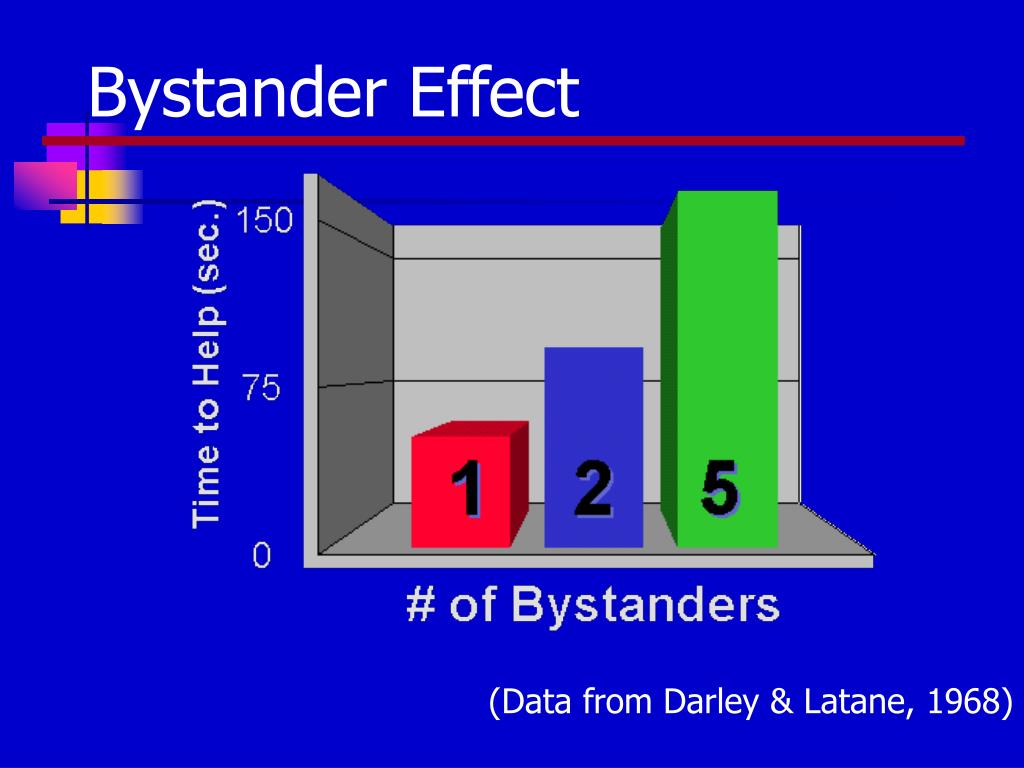

In order to study in more detail the behavior of passers-by in a similar situation, Darley and Latane conducted an experiment. They invited students to special meetings to discuss their problems and experiences. At each meeting there was an actor who spoke first and mimicked a fit a few minutes later. The experimental groups differed in the number of participants: the actor could be one on one with the "experimental" participant, or there could be three people in the room, or even six. nine0003

At each meeting there was an actor who spoke first and mimicked a fit a few minutes later. The experimental groups differed in the number of participants: the actor could be one on one with the "experimental" participant, or there could be three people in the room, or even six. nine0003

Scientists have noticed that in cases where the "experimental" participant of the experiment was the only witness of the "seizure", any assistance was provided to the victim in 85 percent of cases, if there were two witnesses - in 62 percent, and if there were five - only in 31 percentage of cases. At the same time, how quickly assistance was provided also depended on the number of witnesses: left alone with the “injured”, the participants made attempts to help already by 52 seconds, while five took more than two minutes to decide on some action. . nine0003

This experiment led scientists to conclude that people's behavior in such a situation may be due to the so-called "diffusion of responsibility", suggesting that a person is less likely to accept responsibility for an action or inaction if there is someone else around him.

The diffusion of responsibility makes a person think that in a large group of people there will always be someone who can help the victim, which means that he himself can remain an outside observer. In addition, in some cases, people do not help the victim, because they believe that someone else will do it more qualified (for example, it will turn out to be a doctor), while with their unskilled actions they will only interfere with the real savior, or even (which, perhaps, most unpleasant for the unfortunate witness) will have to take responsibility, perhaps even legal, in case their help only hurts. nine0003

Of course, the witnesses of the incident explain their refusal to provide assistance to the victim not only by transferring responsibility to other people (by the way, without knowing for sure whether they will help better and if they will help at all), but also, for example, for reasons of their own safety (“A What if they attack me too?”) or a subjective assessment of the seriousness of the situation. It also turned out that the witness is more likely to help if the area in which he encountered the incident is familiar to him. nine0003

It also turned out that the witness is more likely to help if the area in which he encountered the incident is familiar to him. nine0003

The bystander effect is one of the most studied phenomena in social psychology. In the almost 55 years that have passed since the famous New York murder, scientists have been able to repeatedly show that inaction in a situation where others need help is not due to apathy and indifference, but to deeper features of human psychology.

Update: The original version of the note did not state that The New York Times' account of the story that prompted Darley and Latane's research was largely exaggerated. Despite this, in the very first experiment of scientists they managed to show that such a situation is quite real, but it is not explained by the indifference of observers, but by other factors, many of which have been studied (and are still being studied). Nevertheless, the N + 1 editors apologize for the innuendo when writing the material. nine0032

nine0032

Witness effect. Why People Don't Prevent Murder

Helping someone in need is something most of us are taught from childhood. We all know one way or another how to provide first aid to those in a difficult situation. But from time to time there are incidents when a person in a large crowd of people becomes a victim of an accident or even murder without receiving any help. Why is this happening? Are we human beings so callous?

The so-called “bystander effect”, also known as the “Genovese effect”, named after its most famous victim, Kitty Genovese, is to blame. It was first described in 1968 by two American scientists, Bibb Latane and John Darley. This happened after a terrible incident that stirred up the public around the world. In front of many people, right on the street, an aggressive man killed a young girl for no reason by stabbing her twice in the back. Despite the fact that Kitty loudly called for help, no one present helped her.

The English word "bystander" is translated literally as "witness", "appeared near". An observer, an outsider, an eyewitness, “standing aside”, as they translate it into Russian, still inaccurately reflect its meaning. Probably, the obsolete Russian word “onlookers” is closest to him in meaning. The one who stands and watches with his mouth open, but does nothing. nine0003

An observer, an outsider, an eyewitness, “standing aside”, as they translate it into Russian, still inaccurately reflect its meaning. Probably, the obsolete Russian word “onlookers” is closest to him in meaning. The one who stands and watches with his mouth open, but does nothing. nine0003

Murder in front of witnesses: the sad story of Kitty Genovese

The story took place in New York in an area called Kew Gardens. This area is known as a peaceful, calm place with a low crime rate. Wealthy, intelligent families live here, many of them know each other personally.

Katherine (Kitty) Genovese was 29 years old and worked as a bar manager. On March 13, 1964, she was returning home from work. Parking the car, Kitty noticed a man approaching her. She was frightened and ran, sensing danger, the man chased after her. He caught up with her, grabbed her from behind and stabbed her several times in the back. All this time, Kitty screamed loudly and called for help. "Oh my God! He stabbed me!” the poor girl screamed. The screams were heard by many people in the nearby house, lights came on in the windows. Some man looked out and shouted "Hey, leave the girl alone!". The killer left Kitty for a while and fled. nine0003

The screams were heard by many people in the nearby house, lights came on in the windows. Some man looked out and shouted "Hey, leave the girl alone!". The killer left Kitty for a while and fled. nine0003

A seriously injured girl reached the door of her house and tried to open it. At this time, the killer returned and again inflicted several wounds on her. Neighbors peered out of windows at Kitty's screams. The names of these people are known: Andre Pick, Marjorie and Samuel Koshkin. They managed to see how the killer ran to his car and left, but a few minutes later he returned again and found the girl to deliver the final, fatal blow. Kitty had already entered the hall and lay there bleeding. The killer, taking advantage of the moment, raped her, and then finished off, inflicting a mortal wound. nine0003

In the half hour that this terrible atrocity lasted, none of the witnesses called the police. The offender managed to get into his car and drive away safely. As it later became known, Catherine Genovese became his third victim. A few minutes after the attack, one of the witnesses, Samuel Ross, nevertheless called the police. But it was too late, Kitty died from her wounds in an ambulance on the way to the clinic.

A few minutes after the attack, one of the witnesses, Samuel Ross, nevertheless called the police. But it was too late, Kitty died from her wounds in an ambulance on the way to the clinic.

The killer turned out to be a 29-year-old black man named Winston Mosley, a laborer with no qualifications. He was married, had two children, and lived near the scene of the murder. Had no previous convictions. Mosley cited an irresistible desire to kill a woman as the motive for the murder. The defense collected information about Mosley's mental insanity, but the judge made a mistake by not allowing information about the mental health of the killer to be released at the preliminary hearing. As a result, the original sentence - the death penalty in the electric chair - was commuted to life imprisonment. nine0003

After a year of imprisonment, Mosley attempted to escape: he attacked a guard, took five civilians hostage, raped a woman, and then surrendered to the FBI agents. He spent the next 50 years in prison, during which time his requests for a reduction in his sentence were rejected. He died in 2016 at Great Meadow Prison, New York. It is clear that Mosley was a socially dangerous criminal, a sociopath, and did not repent of his deed at all.

He died in 2016 at Great Meadow Prison, New York. It is clear that Mosley was a socially dangerous criminal, a sociopath, and did not repent of his deed at all.

An interesting fact that reveals the identity of the killer from an unexpected angle: hiding from the scene of the crime, Mosley saw the driver of a neighboring car dozing at the crossroads at the wheel. He stopped, got out of the car and woke up the driver. Amazing altruism after such a cold-blooded murder. nine0003

The tragedy of Kitty's story is that none of the many witnesses to the murder called the police in time. According to crime reporters, a total of 38 people attended the event. True, these data were later revised and a clarification came out that there were much fewer witnesses, about ten. One way or another, they all relied on each other and did nothing, which cost the life of young Kitty.

Darley and Latane's social experiment

Scientists decided to conduct an experiment to understand why people do nothing in a critical situation. Among the hypotheses put forward by them initially were such as the mutual alienation of urban residents, leading to the loss of individuality, the diffusion (distribution) of responsibility and the so-called "mass ignorance". This is the behavior of people in a critical situation, when they look at each other in search of an example of how they should act. As a result, without receiving any instructions and in the absence of guidance, they decide to do nothing. In the diffusion of responsibility, people hope that someone else will help and do not feel guilty, because others did the same. nine0003

Among the hypotheses put forward by them initially were such as the mutual alienation of urban residents, leading to the loss of individuality, the diffusion (distribution) of responsibility and the so-called "mass ignorance". This is the behavior of people in a critical situation, when they look at each other in search of an example of how they should act. As a result, without receiving any instructions and in the absence of guidance, they decide to do nothing. In the diffusion of responsibility, people hope that someone else will help and do not feel guilty, because others did the same. nine0003

For example, in the case of Kitty Genovese, her neighbor Mr. Koshkin was about to call the police from the sixth floor, but his wife dissuaded him from doing so. She said that without him there must have been a lot of calls already. Later in the trial, Mosley admitted that he felt his complete impunity. He was sure that the man screaming from the window would simply close his window and go to sleep. Unfortunately for his victim, that's exactly what happened.

Unfortunately for his victim, that's exactly what happened.

For the experiment, Bibb Darley and John Latane gathered students, as if into psychological support groups, where everyone could talk about their problems and get help. An important organizational moment: all the subjects were in separate rooms, not seeing each other, only hearing voices via audio communication. Each participant had the opportunity to speak for two minutes. nine0003

All experimental groups differed in the number of people: two, three or six people. In fact, there were only two participants, the subject and the actor, the rest of the voices were just a recording. But everything looked so that each subject was sure that he was communicating with several people.

In each group there was a figurehead, an actor, about whom the subjects did not know in advance. Before the start of the experiment, he reported that in extreme situations he could become ill. He began to speak first, and suddenly pretended to have a fit. "Help! I'll die now! Call for help!" - heard the subjects on the intercom. And here the reactions of people were divided, depending on how many people were declared in the group (in fact, in each situation there were only two of them). nine0003

"Help! I'll die now! Call for help!" - heard the subjects on the intercom. And here the reactions of people were divided, depending on how many people were declared in the group (in fact, in each situation there were only two of them). nine0003

- In groups of two, 85% of the subjects called for help;

- In groups of three, 62% of students reported a seizure;

- In groups of six, only 31% of the subjects called for help.

Thus, the experiment confirmed the effect of dissipation of responsibility: the more people there were in the experimental group, the less the participants in the experiment felt personally responsible for providing assistance.

The second experiment was organized in the same way as the first, but this time the students had to sit in a secluded room and complete a written task by completing a questionnaire. It was a survey supposedly designed to reveal the difficulties of city dwellers. At some point, smoke began to seep into the room, which was specially let in through a hole in the wall. That is, this time the imaginary danger threatened not an outsider, but the subjects themselves. And here again, the statistics turned out to be different, depending on the number of people present:

That is, this time the imaginary danger threatened not an outsider, but the subjects themselves. And here again, the statistics turned out to be different, depending on the number of people present:

- 50% of students doing the task alone took active steps to prevent the "fire" in the first 4 minutes;

- 75% of the subjects began to act only after 6 minutes, that is, after the end of the experiment, while the smoke was already so strong that visibility deteriorated.

However, when the students did the task in groups of three, the results were strikingly different:

- only 4% of the participants reported smoke in the first 4 minutes; nine0074

- only 38% worried about their safety within 6 minutes.

Then the experiment was complicated: there were two shams among the participants who answered “I don't know” to the participants' questions like “Do you think maybe we should do something?”. And in this case, only 10 participants called for help in the first 6 minutes after the end of the experiment. Thus, most of the subjects did not want to disturb their peace of mind with unnecessary responsibility. And looking at those around them, they calmed down, seeing that they were also inactive. nine0003

Thus, most of the subjects did not want to disturb their peace of mind with unnecessary responsibility. And looking at those around them, they calmed down, seeing that they were also inactive. nine0003

Later, the experiment was repeated by scientists in Toronto with even more impressive results: 90% of single test subjects reacted to smoke and only 16% in groups with two front men.

Darley and Latane also conducted other studies of people's actions in non-standard situations, for example, students on the street asked the name of people passing by, asking them for 10 cents. The result showed that people were more willing to give their name if the person who approached him introduced himself first, and gave money if they received some kind of explanation (for example, a stolen wallet) - in about 72% of cases, and only in 34% of cases when the person asking for nothing explained. And according to statistics collected by the EMS service, the likelihood of providing assistance to victims correlated with the degree of threat to health. nine0003

nine0003

Other cases of “bystander effect”

Similar stories, unfortunately, occur all over the world. The most tragic cases are reported by the media.

In 1998, Levi Frosted, an American, reported in a chat room struggling with alcoholism that he got drunk and set fire to his house, in which his little daughter burned down. Of the 200 present, no one took the report seriously, and after much argument, only three reported the murder to the police.

In 2008, 49 died in a Brooklyn hospitala year old woman named Esmine Green after a day of waiting for help. For about an hour she lay on the floor in front of other patients and guards passing by.

An accident occurred in the St. Petersburg metro the same year: a young girl fell into a gap between the subway cars. This was recorded by surveillance cameras. Near the victim there were many people entering and leaving the cars. Several people noticed what was happening, but no one helped the girl, and she died under the wheels of the train. nine0003

nine0003

In 2009, Jane Doe, a graduate of Richmond High School, was raped and beaten by a group of young people after prom. This event was attended by 20 people, but no one helped the girl, moreover, many watched this incident with pleasure, filming it on the phone.

In 2009, two girls were hit by a car in the center of Irkutsk. Nobody helped them either, the drivers drove by and did not stop.

In 2011 in China, a two-year-old girl ran into the street and was hit by a car. She was still alive and lying on the road. Pedestrians passed by, drivers drove around her, but no one helped the child up and carried her to a safe place. After 7 minutes, the girl was hit by a truck, already to death. Only then did a woman run up to her, who called her mother. Alas, it was already too late. nine0003

In 2011 in California, Alameda, 51-year-old Raymond Zach entered the water on the beach and, going up to his neck, stood 150 yards from the shore for an hour in front of many people. According to his mother, the man was about to drown himself. Firefighters and police, watching the incident, called for a Coast Guard boat, but no one entered the water to provide assistance. According to the police, they did not have the appropriate training and certificates for land water rescue. An hour later, apparently due to hypothermia, Zak plunged into the water. Only a few minutes later, one of the watching men pulled it out. Zach later died at a local hospital. nine0003

According to his mother, the man was about to drown himself. Firefighters and police, watching the incident, called for a Coast Guard boat, but no one entered the water to provide assistance. According to the police, they did not have the appropriate training and certificates for land water rescue. An hour later, apparently due to hypothermia, Zak plunged into the water. Only a few minutes later, one of the watching men pulled it out. Zach later died at a local hospital. nine0003

What if you need help and you are in a large crowd?

According to research by Darley and Latane, the following 5 characteristics of a situation that can affect bystanders influence the “bystander effect”:

- Emergencies are rare and unusual.

- Emergencies are associated with a threat to life and health.

- They are unexpected, cannot be predicted in advance.

- Helping a person requires immediate action. nine0074

- The type of action required for assistance may vary from case to case.

Due to these characteristics, people present during an emergency go through the following cognitive and behavioral processes:

- Notice that something is happening.

- Interpret the situation as an emergency.

- Define the degree of responsibility.

- Select form of assistance.

- Carry out specific actions to rescue the victim. nine0074

Most of those present do not expect an emergency, are not ready for it, do not know how to act, and can simply become confused, fall into a stupor. Help can be provided by specially trained people - rescuers, ambulance workers. But in order to summon them, someone has to take responsibility for it. And the "bystander effect", unfortunately, dissipates this responsibility.

If you are the one in an emergency situation and you need help, you need to ask for help, observing the following conditions:

- Act quickly. Try to keep from panic, for this you can focus on breathing, breathe deeper.

If you feel that you are becoming ill, losing consciousness - call for help immediately.

If you feel that you are becoming ill, losing consciousness - call for help immediately. - Ask a specific person for help. Usually, if the request is addressed, the person rarely refuses. Identify this person in any way by referring to him. For example: “The man in the blue jacket! Yes you". If possible, take the nearest person by the hand and ask for help. nine0074

- Tell the person loudly and clearly what is required of him. For example: “Do you have a phone? Call the police! Call an ambulance!" etc.

If you are a witness and ready to help, but do not have first aid skills:

- Make sure you are not in danger. You are not on the roadway, there are no exposed live wires nearby, fire, wild animals, working mechanisms, etc. If the victim received an electric shock, the wire can be removed from him with a wooden stick, but in no case not with hands. nine0074

- If possible, place the casualty in a safe place where they can wait for the ambulance to arrive.

- Check the reaction of the victim, if he is conscious, talk to him, try to calm him down.

- Call an ambulance or rescue service (112).

- If you are skilled in first aid, do what you can to help the casualty survive until paramedics arrive. If you don’t know how, it’s better to turn to those present and ask who knows how to do it. Inept first aid can sometimes only worsen the situation. nine0074

Of course, it is very important to inform people about how they can help themselves and others in emergency situations. But it's also important to remember that the world is generally an unsafe place, despite all the blessings of civilization. We are vulnerable and everyone may need help at any moment. Today we help, and tomorrow they help us or our loved ones. Mutual indifference, responsiveness and compassion - this is exactly what makes us human.

References:

- 1. Kopets L. V. "Classical experiments in psychology" - K.

, 2010

- 2. J. Rolls. "Classic cases in psychology" - M., 2010

- 3. Robert D. Cialdini. "The Psychology of Influence". - M., 2010.

- 4. "The Kitty Genovese Murder and the Social Psychology of Helping: the parable of the 38 witnesses" Rachel Manning University of the West of England, Bristol Mark Levine and Alan Collins Lancaster University. /www.psych.lancs.ac.uk/people/uploads/MarkLevine20070604T095238.pdf

- 5. "37 Who Saw Murder Didn't Call the Police; Apathy at Stabbing of Queens Woman Shocks Inspector - The New York Time, March 27, 1964 https://www.nytimes.com/1964/03/27/archives/37-who-saw-murder-didnt-call-the -police-apathy-at-stabbing-of.html

Author: Nadezhda Kozochkina, psychologist

Editor: Chekardina Elizaveta Yurievna

- To write or not to write? – that is the question https://psychosearch.ru/7reasonstowrite

- How to become a partner of PsychoPoisk magazine? https://psychosearch.