Symptoms of hypomania disorder

What Is It, Comparison vs Mania, Symptoms & Treatment

Overview

What is hypomania?

Hypomania is a condition in which you have a period of abnormally elevated, extreme changes in your mood or emotions, energy level or activity level. This energized level of energy, mood and behavior must be a change from your usual self and be noticeable by others.

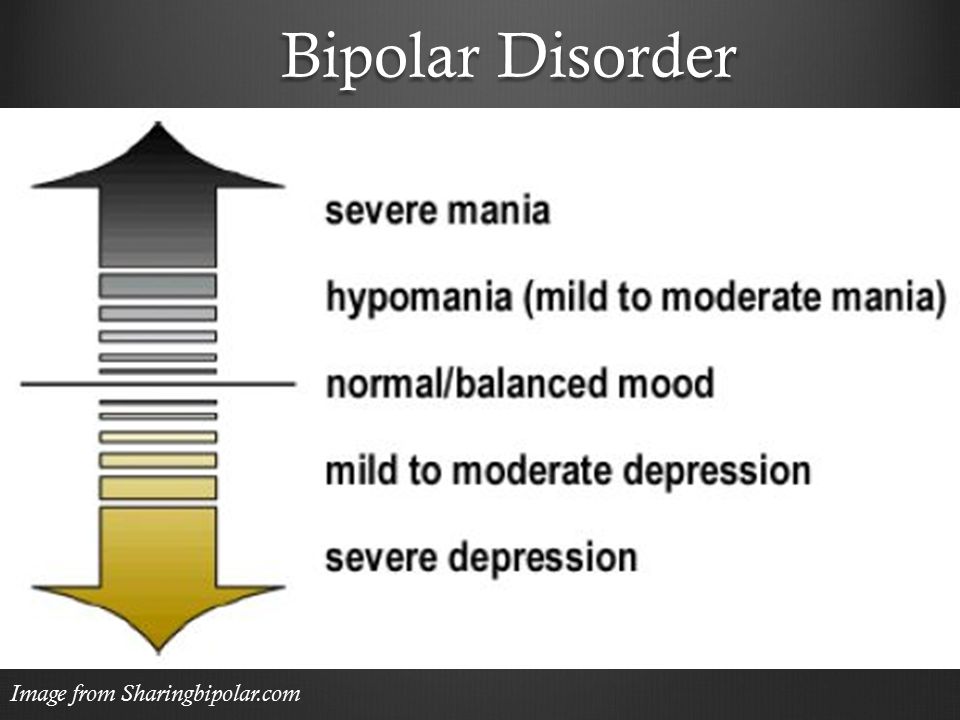

Hypomania is a symptom of bipolar disorder, but can also be a symptom of other mental health conditions.

What’s the difference between hypomania and mania?

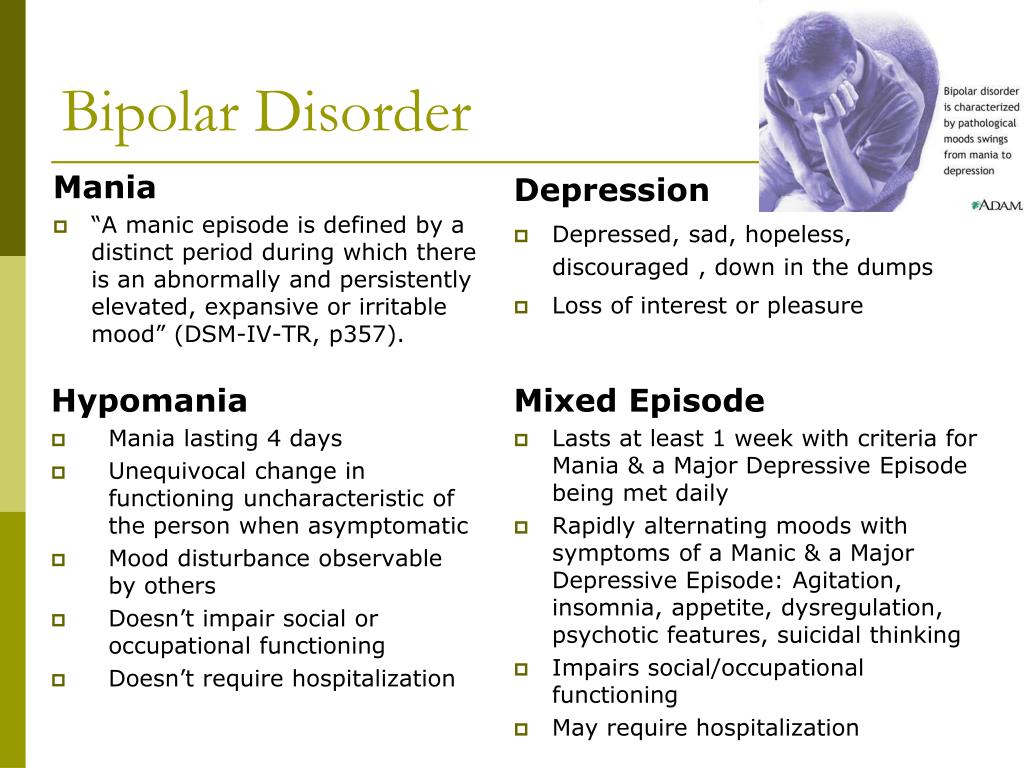

Hypomania is a less severe form of mania. The criteria that healthcare professionals use to make the diagnosis of either hypomania or mania is what sets them apart. These differences are as follows:

| Hypomania | Mania | |

|---|---|---|

| How long the episode lasts | At least four consecutive days | At least one week |

| Severity of episode | Not severe enough to significantly affect social or work/school functioning | Causes severe impact on social or work/school functioning |

| Need for hospitalization | No | Possibly |

| Need for hospitalization | Can’t be present for a diagnosis of hypomania | Is among possible symptoms |

What triggers a hypomanic episode?

Each person’s triggers may be different. Some common triggers include:

- A highly stimulating situation or environment (e.g., lots of noise, bright lights, large crowds).

- A major life change (e.g., divorce, marriage, job loss).

- Lack of sleep.

- Substance use, such as recreational drugs or alcohol.

It’s smart to develop a list of your triggers to know when a hypomanic episode may be starting. Since hypomania doesn’t cause severe changes in your activity level, mood or behavior, it may be helpful to ask family and close friends who you trust and have close contact with to help identify your triggers. They may notice changes from your usual self more easily than you do. Share your trigger list with your close, trusted friends so they can tell when you might need help.

How long does a hypomanic episode last?

According to the criteria for hypomania, hypomania must last at least four days. But it can last up to several months.

What happens after a hypomanic episode?

After a hypomanic episode you may:

- Feel happy or embarrassed about your behavior.

- Feel overwhelmed by all the activities you’ve agreed to take on.

- Have only a few or unclear memories of what happened during your manic episode.

- Feel very tired and need sleep.

- Feel depressed (if your hypomania is part of bipolar disorder).

Symptoms and Causes

What are the symptoms of hypomania?

Symptoms of a hypomanic episode are the same but less intense than mania. Hypomanic symptoms, which vary from person to person, include:

- Having an abnormally high level of activity or energy.

- Feeling extremely happy, excited.

- Not sleeping or only getting a few hours of sleep but still feel rested.

- Having an inflated self-esteem, thinking you’re invincible.

- Being more talkative than usual. Talking so much and so fast that others can’t interrupt.

- Having racing thoughts — having lots of thoughts on lots of topics at the same time (called a “flight of ideas”).

- Being easily distracted by unimportant or unrelated things.

- Being obsessed with and completely absorbed in an activity you’re focus on.

- Displaying purposeless movements, such as pacing around your home or office or fidgeting when you’re sitting.

- Showing impulsive behavior that can lead to poor choices, such as buying sprees, reckless sex or foolish business investments.

What’s the difference between feeling good vs hypomania?

It takes time to know the difference. Everyone enjoys being happy and feeling good. But feeling good doesn’t always mean you are good. Over time, you’ll start to understand yourself and learn the warning signs that you may be starting to have an elevated mood that is different than just feeling good.

Ask family and close friends who you trust, and have frequent contact with, to give you feedback. Ask them to tell you when they see beyond normal changes in your mood or behaviors.

What does hypomania feel and look like?

What hypomania feels like and looks like will be different for each person. Some examples of things you might feel and/or do include:

Some examples of things you might feel and/or do include:

- Get into an intense cleaning frenzy and clean all surfaces of every room in your house.

- Stay up until 3 a.m. or don’t go to bed at all and not feel tired the next morning.

- Start a project, or more than one project, and work non-stop on these projects for 20 hours straight.

- Feel that you can’t fail at anything you want to do, even if you have no training or experience.

- Call and text all your friends all day and night and post a large number of pictures and comments on social media.

- Quickly jump from subject to subject when talking, and talking very fast.

What causes hypomania?

Scientists aren’t completely sure what causes hypomania. However, there are several factors that are thought to contribute. Causes differ from person to person.

Causes may include:

- Family history. If you have a family member with bipolar illness, you have an increased chance of developing mania.

This is not definite though. You may never develop mania even if other family members have.

This is not definite though. You may never develop mania even if other family members have. - Chemical imbalance in your brain.

- Side effect of a medication (such as some antidepressants), alcohol or recreational drugs.

- A significant change in your life, such as a divorce, house move or death of a loved one.

- Difficult life situations, such as trauma or abuse, or problems with housing, money or loneliness.

- High stress level and inability to manage it.

- Lack of sleep or changes in sleep pattern.

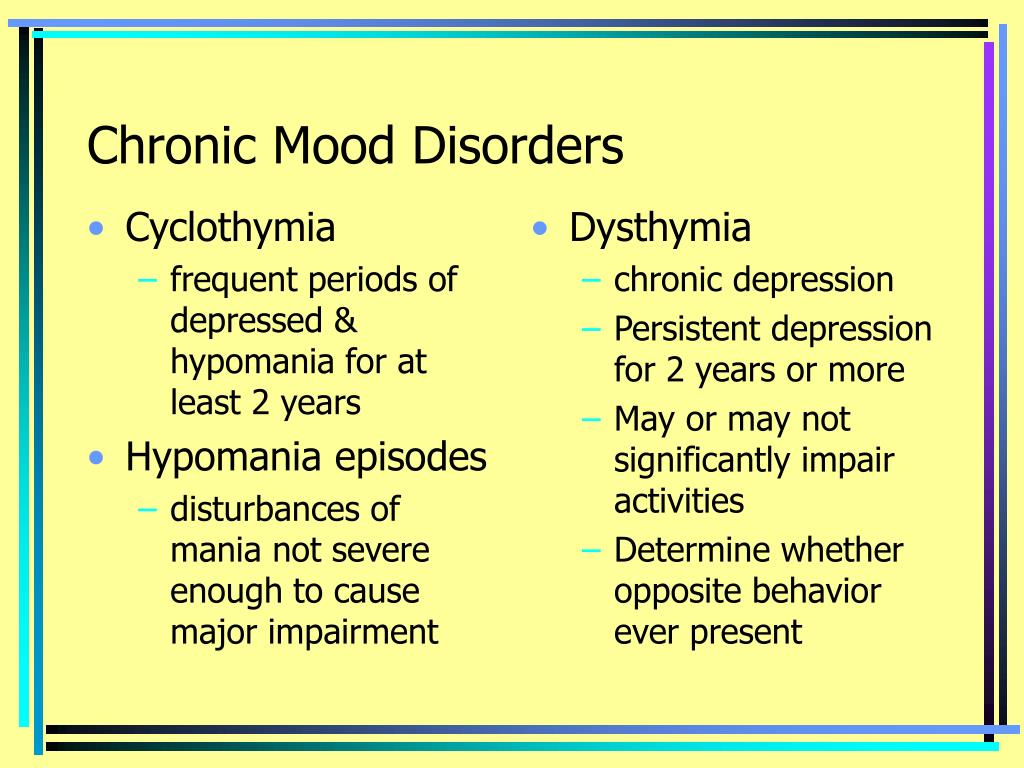

- As a symptom of mental health problems including cyclothymia, seasonal affective disorder, postpartum psychosis, schizoaffective disorder or other physical or neurologic condition such as brain injury, brain tumors, stroke, dementia, lupus or encephalitis.

Diagnosis and Tests

How is hypomania diagnosed?

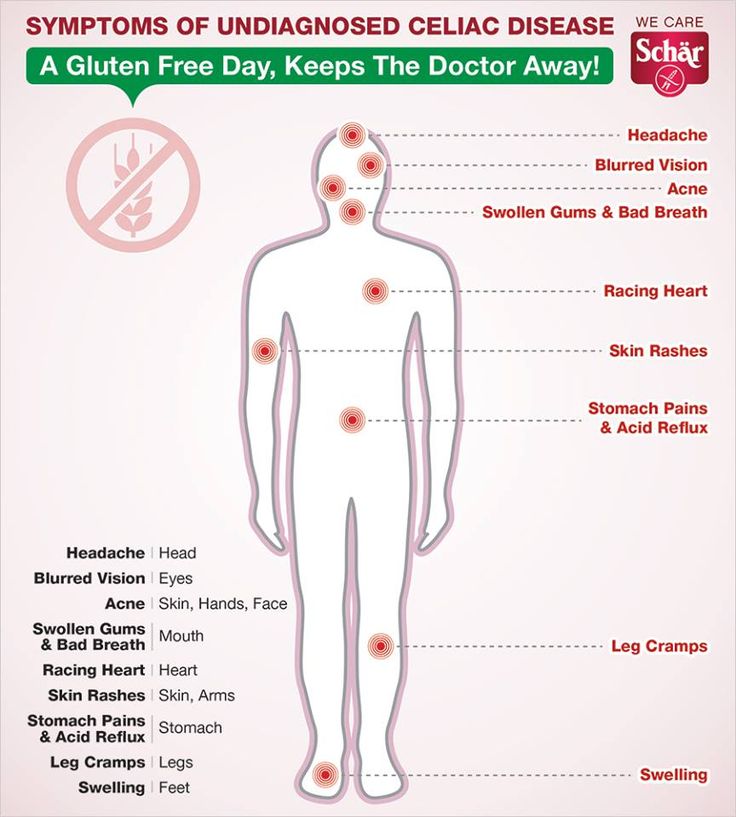

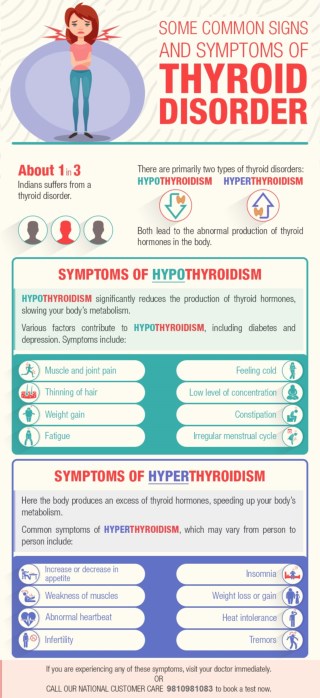

Your healthcare provider will ask about your medical history, family medical history, current prescriptions and non-prescription medications and any herbal products or supplements you take. Your provider may order blood tests and body scans to rule out other conditions that may mimic mania. One such condition is hyperthyroidism. If other diseases and conditions are ruled out, your provider may refer you to a mental health specialist

Your provider may order blood tests and body scans to rule out other conditions that may mimic mania. One such condition is hyperthyroidism. If other diseases and conditions are ruled out, your provider may refer you to a mental health specialist

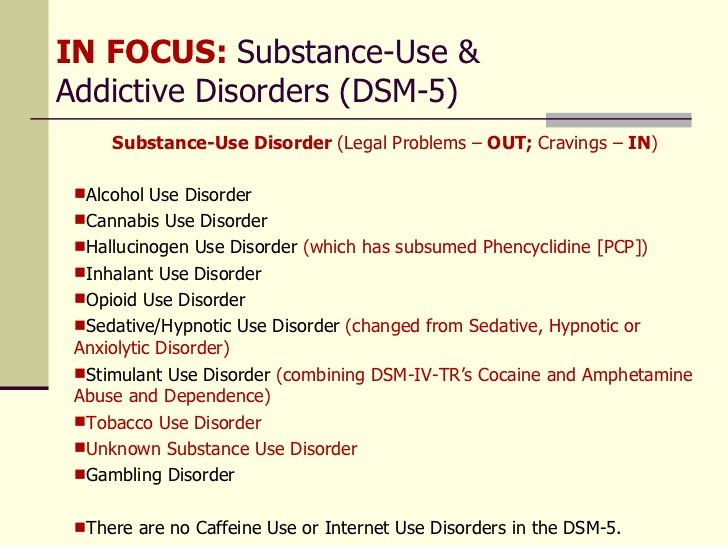

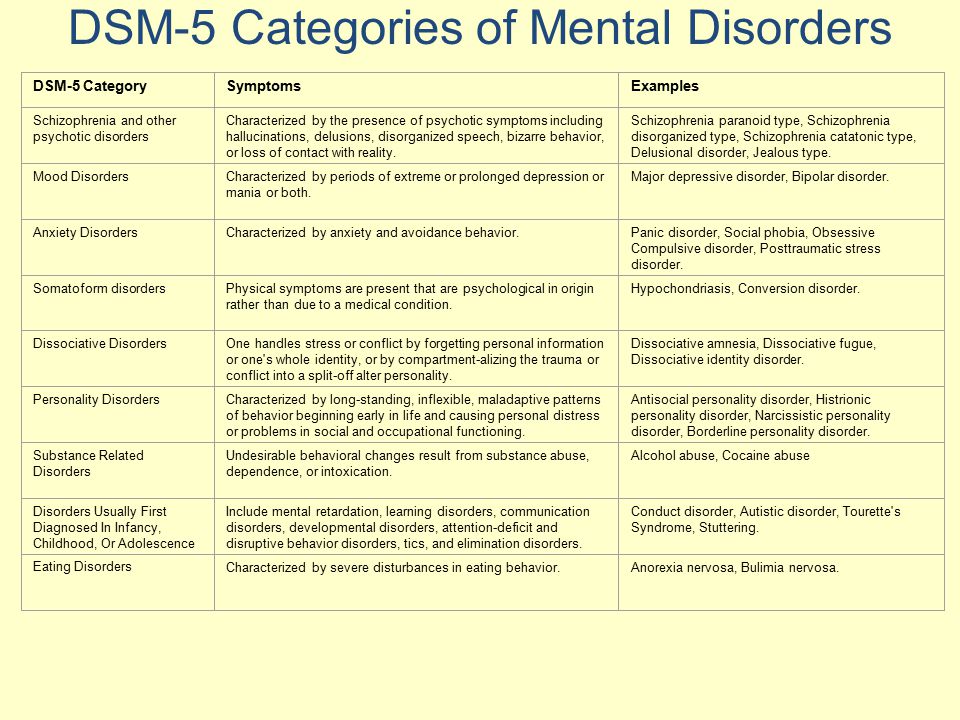

To be diagnosed with hypomania, your mental health specialist may follow the criteria of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5. Their criteria for manic episode is:

- You have an abnormal, long-lasting elevated expression of emotion along with a high degree of energy and activity that lasts for at least four consecutive days and is present most of the day, nearly every day.

- You have three or more symptoms to a degree that they’re a noticeable change from your usual behavior (four symptoms if mood is only irritable). (See the symptoms section of this article for a list of the symptoms used as criteria.)

- The hypomanic episode is not severe enough to significantly interfere with your social, work or school functioning and there’s no need for hospitalization.

- The hypomanic episode can’t be caused by the effects of a substance (medications or drug abuse) or another medical condition.

If you have hypomania, you don’t have thoughts that are out of step with reality — you don’t have false beliefs (delusions) or false perceptions (hallucinations). If you do have these symptoms of psychosis, your diagnosis is mania.

What is bipolar II disorder?

Bipolar II disorder is a type of bipolar disorder in which people experience depressive episodes as well as hypomanic episodes (shifting back and forth), but never mania. People with bipolar II disorder tend to have longer and more frequent depressed episodes than people with bipolar I disorder.

If the severity of your symptoms never rises to the level of mania, you have bipolar II disorder. If you have even a single episode of what is considered mania or one psychotic event (delusions or hallucinations) during a hypomanic episode, your diagnosis would change to bipolar I disorder.

Management and Treatment

How is hypomania treated?

Hypomania is treated with psychotherapy, antipsychotic medications and mood stabilizers.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy involves a variety of techniques. During psychotherapy, you’ll talk with a mental health professional who will help you identify hypomania symptoms and triggers and learn ways to cope with or lessen the effects of hypomanic episodes.

Medications

Antipsychotic medication choices include:

- Ariprazole (Abilify®).

- Lurasidone (Latuda®).

- Lanzapine (Zyprexa®).

- Quetiapine (Seroquel®).

- Risperridone (Risperdal®).

Mood stabilizers include:

- Lithium.

- Valproate (Depakote®).

- Carbamazepine (Tegretol®).

(If you’re pregnant or plan to become pregnant, let your provider know. Valproate can increase the chance of birth defects and learning disabilities and shouldn’t be prescribed to individuals who are able to become pregnant. )

)

Sometimes antidepressants are also prescribed.

Managing hypomania without medications

If your hypomania is mild, you may be able to cope without medications. Your healthcare provider may suggest having a greater focus on self-care to stay as healthy as possible.

Suggested actions may include:

- Go to bed at the same time each night and get plenty of sleep (six to nine hours).

- Avoid stimulating triggers such as coffee, tea, colas, sugar, noisy and crowded environments.

- Eat a healthy diet, such as the Mediterranean or Dash diet.

- Get 30 minutes of exercise on most days of the week. Even two short walks a day is beneficial.

- Don’t use illegal or recreational drugs or alcohol.

- Learn ways to relax. Yoga, meditation, listening to calming music, aromatherapy are a few examples.

- Take all medications as prescribed or instructed on package labeling. If you think you’re having side effects or new side effects to a medication, call your provider.

Never stop taking — or change the dose — of a prescription medication without talking to your provider first. Make sure they know all supplements, herbal products and vitamins you take.

Never stop taking — or change the dose — of a prescription medication without talking to your provider first. Make sure they know all supplements, herbal products and vitamins you take. - Join a support group. Ask your provider for contact information for local support groups. You might find it helpful to talk with other people who have similar medical experiences and share problems, ideas for coping and strategies for living and caring for yourself.

Prevention

Can hypomania be prevented?

Episodes of hypomania can’t always be prevented. However, you can learn ways to better manage your symptoms and prevent them from getting worse.

Suggestions on your “to-do list” might include:

- Keeping a “mood diary” to become more self-aware of events that trigger an oncoming episode of hypomania. These events are unique to you. Sometimes you can’t recognize your own triggers. Ask your trusted, close family and friends to help identify when they see changes in your mood, behavior and energy level that is different from your usual self.

- Following other coping strategies. (See the bulleted list under, “Managing hypomania without drugs,” just above in this article.)

Outlook / Prognosis

What outcome can I expect if I’ve been diagnosed with hypomania?

If you’ve been diagnosed with hypomania, you can have a favorable outcome if you learn about your condition, learn to recognize when you’re having a hypomanic episode and engage in coping strategies to lessen the severity or prevent events. Always take any prescribed medications as directed by your healthcare provider.

A note from Cleveland Clinic

Being amped up about your life and being in a good mood is usually thought to be a good thing. It can be if that’s how you normally are most of the time. This is what makes hypomania a little tricky to diagnose. Key to a diagnosis of hypomania is that your elevated mood, behavior or activity level must last at least four days (all day or most of the day) and must rise to the level that’s beyond normal and is noticeable by others. Know that a team of healthcare professionals — your primary care provider, psychologists and/or psychiatrist — is ready to help you figure this out.

Know that a team of healthcare professionals — your primary care provider, psychologists and/or psychiatrist — is ready to help you figure this out.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can my diagnosis change between bipolar II disorder and bipolar I disorder?

Yes. If you have been diagnosed with the less severe condition of hypomania and have even a single episode of mania (as defined by the criteria), your diagnosis will change to bipolar I disorder. Once you have a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder – even if you never have another manic episode – your diagnosis can never be changed back to bipolar II disorder. You’ll always have a bipolar I disorder diagnosis.

What Is It, Comparison vs Mania, Symptoms & Treatment

Overview

What is hypomania?

Hypomania is a condition in which you have a period of abnormally elevated, extreme changes in your mood or emotions, energy level or activity level. This energized level of energy, mood and behavior must be a change from your usual self and be noticeable by others.

Hypomania is a symptom of bipolar disorder, but can also be a symptom of other mental health conditions.

What’s the difference between hypomania and mania?

Hypomania is a less severe form of mania. The criteria that healthcare professionals use to make the diagnosis of either hypomania or mania is what sets them apart. These differences are as follows:

| Hypomania | Mania | |

|---|---|---|

| How long the episode lasts | At least four consecutive days | At least one week |

| Severity of episode | Not severe enough to significantly affect social or work/school functioning | Causes severe impact on social or work/school functioning |

| Need for hospitalization | No | Possibly |

| Need for hospitalization | Can’t be present for a diagnosis of hypomania | Is among possible symptoms |

What triggers a hypomanic episode?

Each person’s triggers may be different. Some common triggers include:

Some common triggers include:

- A highly stimulating situation or environment (e.g., lots of noise, bright lights, large crowds).

- A major life change (e.g., divorce, marriage, job loss).

- Lack of sleep.

- Substance use, such as recreational drugs or alcohol.

It’s smart to develop a list of your triggers to know when a hypomanic episode may be starting. Since hypomania doesn’t cause severe changes in your activity level, mood or behavior, it may be helpful to ask family and close friends who you trust and have close contact with to help identify your triggers. They may notice changes from your usual self more easily than you do. Share your trigger list with your close, trusted friends so they can tell when you might need help.

How long does a hypomanic episode last?

According to the criteria for hypomania, hypomania must last at least four days. But it can last up to several months.

What happens after a hypomanic episode?

After a hypomanic episode you may:

- Feel happy or embarrassed about your behavior.

- Feel overwhelmed by all the activities you’ve agreed to take on.

- Have only a few or unclear memories of what happened during your manic episode.

- Feel very tired and need sleep.

- Feel depressed (if your hypomania is part of bipolar disorder).

Symptoms and Causes

What are the symptoms of hypomania?

Symptoms of a hypomanic episode are the same but less intense than mania. Hypomanic symptoms, which vary from person to person, include:

- Having an abnormally high level of activity or energy.

- Feeling extremely happy, excited.

- Not sleeping or only getting a few hours of sleep but still feel rested.

- Having an inflated self-esteem, thinking you’re invincible.

- Being more talkative than usual. Talking so much and so fast that others can’t interrupt.

- Having racing thoughts — having lots of thoughts on lots of topics at the same time (called a “flight of ideas”).

- Being easily distracted by unimportant or unrelated things.

- Being obsessed with and completely absorbed in an activity you’re focus on.

- Displaying purposeless movements, such as pacing around your home or office or fidgeting when you’re sitting.

- Showing impulsive behavior that can lead to poor choices, such as buying sprees, reckless sex or foolish business investments.

What’s the difference between feeling good vs hypomania?

It takes time to know the difference. Everyone enjoys being happy and feeling good. But feeling good doesn’t always mean you are good. Over time, you’ll start to understand yourself and learn the warning signs that you may be starting to have an elevated mood that is different than just feeling good.

Ask family and close friends who you trust, and have frequent contact with, to give you feedback. Ask them to tell you when they see beyond normal changes in your mood or behaviors.

What does hypomania feel and look like?

What hypomania feels like and looks like will be different for each person. Some examples of things you might feel and/or do include:

Some examples of things you might feel and/or do include:

- Get into an intense cleaning frenzy and clean all surfaces of every room in your house.

- Stay up until 3 a.m. or don’t go to bed at all and not feel tired the next morning.

- Start a project, or more than one project, and work non-stop on these projects for 20 hours straight.

- Feel that you can’t fail at anything you want to do, even if you have no training or experience.

- Call and text all your friends all day and night and post a large number of pictures and comments on social media.

- Quickly jump from subject to subject when talking, and talking very fast.

What causes hypomania?

Scientists aren’t completely sure what causes hypomania. However, there are several factors that are thought to contribute. Causes differ from person to person.

Causes may include:

- Family history. If you have a family member with bipolar illness, you have an increased chance of developing mania.

This is not definite though. You may never develop mania even if other family members have.

This is not definite though. You may never develop mania even if other family members have. - Chemical imbalance in your brain.

- Side effect of a medication (such as some antidepressants), alcohol or recreational drugs.

- A significant change in your life, such as a divorce, house move or death of a loved one.

- Difficult life situations, such as trauma or abuse, or problems with housing, money or loneliness.

- High stress level and inability to manage it.

- Lack of sleep or changes in sleep pattern.

- As a symptom of mental health problems including cyclothymia, seasonal affective disorder, postpartum psychosis, schizoaffective disorder or other physical or neurologic condition such as brain injury, brain tumors, stroke, dementia, lupus or encephalitis.

Diagnosis and Tests

How is hypomania diagnosed?

Your healthcare provider will ask about your medical history, family medical history, current prescriptions and non-prescription medications and any herbal products or supplements you take. Your provider may order blood tests and body scans to rule out other conditions that may mimic mania. One such condition is hyperthyroidism. If other diseases and conditions are ruled out, your provider may refer you to a mental health specialist

Your provider may order blood tests and body scans to rule out other conditions that may mimic mania. One such condition is hyperthyroidism. If other diseases and conditions are ruled out, your provider may refer you to a mental health specialist

To be diagnosed with hypomania, your mental health specialist may follow the criteria of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5. Their criteria for manic episode is:

- You have an abnormal, long-lasting elevated expression of emotion along with a high degree of energy and activity that lasts for at least four consecutive days and is present most of the day, nearly every day.

- You have three or more symptoms to a degree that they’re a noticeable change from your usual behavior (four symptoms if mood is only irritable). (See the symptoms section of this article for a list of the symptoms used as criteria.)

- The hypomanic episode is not severe enough to significantly interfere with your social, work or school functioning and there’s no need for hospitalization.

/legionnaires-disease-overview-4175995-5c0f2a28c9e77c0001c970a3.png)

- The hypomanic episode can’t be caused by the effects of a substance (medications or drug abuse) or another medical condition.

If you have hypomania, you don’t have thoughts that are out of step with reality — you don’t have false beliefs (delusions) or false perceptions (hallucinations). If you do have these symptoms of psychosis, your diagnosis is mania.

What is bipolar II disorder?

Bipolar II disorder is a type of bipolar disorder in which people experience depressive episodes as well as hypomanic episodes (shifting back and forth), but never mania. People with bipolar II disorder tend to have longer and more frequent depressed episodes than people with bipolar I disorder.

If the severity of your symptoms never rises to the level of mania, you have bipolar II disorder. If you have even a single episode of what is considered mania or one psychotic event (delusions or hallucinations) during a hypomanic episode, your diagnosis would change to bipolar I disorder.

Management and Treatment

How is hypomania treated?

Hypomania is treated with psychotherapy, antipsychotic medications and mood stabilizers.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy involves a variety of techniques. During psychotherapy, you’ll talk with a mental health professional who will help you identify hypomania symptoms and triggers and learn ways to cope with or lessen the effects of hypomanic episodes.

Medications

Antipsychotic medication choices include:

- Ariprazole (Abilify®).

- Lurasidone (Latuda®).

- Lanzapine (Zyprexa®).

- Quetiapine (Seroquel®).

- Risperridone (Risperdal®).

Mood stabilizers include:

- Lithium.

- Valproate (Depakote®).

- Carbamazepine (Tegretol®).

(If you’re pregnant or plan to become pregnant, let your provider know. Valproate can increase the chance of birth defects and learning disabilities and shouldn’t be prescribed to individuals who are able to become pregnant. )

)

Sometimes antidepressants are also prescribed.

Managing hypomania without medications

If your hypomania is mild, you may be able to cope without medications. Your healthcare provider may suggest having a greater focus on self-care to stay as healthy as possible.

Suggested actions may include:

- Go to bed at the same time each night and get plenty of sleep (six to nine hours).

- Avoid stimulating triggers such as coffee, tea, colas, sugar, noisy and crowded environments.

- Eat a healthy diet, such as the Mediterranean or Dash diet.

- Get 30 minutes of exercise on most days of the week. Even two short walks a day is beneficial.

- Don’t use illegal or recreational drugs or alcohol.

- Learn ways to relax. Yoga, meditation, listening to calming music, aromatherapy are a few examples.

- Take all medications as prescribed or instructed on package labeling. If you think you’re having side effects or new side effects to a medication, call your provider.

Never stop taking — or change the dose — of a prescription medication without talking to your provider first. Make sure they know all supplements, herbal products and vitamins you take.

Never stop taking — or change the dose — of a prescription medication without talking to your provider first. Make sure they know all supplements, herbal products and vitamins you take. - Join a support group. Ask your provider for contact information for local support groups. You might find it helpful to talk with other people who have similar medical experiences and share problems, ideas for coping and strategies for living and caring for yourself.

Prevention

Can hypomania be prevented?

Episodes of hypomania can’t always be prevented. However, you can learn ways to better manage your symptoms and prevent them from getting worse.

Suggestions on your “to-do list” might include:

- Keeping a “mood diary” to become more self-aware of events that trigger an oncoming episode of hypomania. These events are unique to you. Sometimes you can’t recognize your own triggers. Ask your trusted, close family and friends to help identify when they see changes in your mood, behavior and energy level that is different from your usual self.

- Following other coping strategies. (See the bulleted list under, “Managing hypomania without drugs,” just above in this article.)

Outlook / Prognosis

What outcome can I expect if I’ve been diagnosed with hypomania?

If you’ve been diagnosed with hypomania, you can have a favorable outcome if you learn about your condition, learn to recognize when you’re having a hypomanic episode and engage in coping strategies to lessen the severity or prevent events. Always take any prescribed medications as directed by your healthcare provider.

A note from Cleveland Clinic

Being amped up about your life and being in a good mood is usually thought to be a good thing. It can be if that’s how you normally are most of the time. This is what makes hypomania a little tricky to diagnose. Key to a diagnosis of hypomania is that your elevated mood, behavior or activity level must last at least four days (all day or most of the day) and must rise to the level that’s beyond normal and is noticeable by others. Know that a team of healthcare professionals — your primary care provider, psychologists and/or psychiatrist — is ready to help you figure this out.

Know that a team of healthcare professionals — your primary care provider, psychologists and/or psychiatrist — is ready to help you figure this out.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can my diagnosis change between bipolar II disorder and bipolar I disorder?

Yes. If you have been diagnosed with the less severe condition of hypomania and have even a single episode of mania (as defined by the criteria), your diagnosis will change to bipolar I disorder. Once you have a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder – even if you never have another manic episode – your diagnosis can never be changed back to bipolar II disorder. You’ll always have a bipolar I disorder diagnosis.

FGBNU NTsPZ. ‹‹Endogenous mental illness››

Hypomania (mania levis, mania mitis) is a mild form of mania, including in a weakened form the manifestations of the latter. Hypomanic syndrome, like classical mania, is determined by an increased, hyperthymic affect, sometimes with features of euphoria (carefree contentment, serenity, passive tenderness), acceleration of cognitive processes with increased talkativeness, irritability, mobility, and a reduction in nighttime sleep. Hypomania is usually egosyntonic and is subjectively perceived as a state of natural, pleasant elation. A critical attitude to the disorder is subjectively difficult: signs of recovery, uncharacteristic for the patient outside this period, are more often noticeable only for his environment. Manifestations of hypomania include both affective disorders (hyperthymia) and auto- and somatopsychic spheres.

Hypomania is usually egosyntonic and is subjectively perceived as a state of natural, pleasant elation. A critical attitude to the disorder is subjectively difficult: signs of recovery, uncharacteristic for the patient outside this period, are more often noticeable only for his environment. Manifestations of hypomania include both affective disorders (hyperthymia) and auto- and somatopsychic spheres.

Hyperthymia is characterized by an increase in the general (vital) tone, cheerfulness, a sense of well-being, excessive, usually incommensurable with the real situation of optimism. Pathologically altered affect corresponds to a change in self-esteem with a boastful exaggeration of one's own merits, conviction in one's originality, infallibility, ideas of superiority. With such “existence with arrogance” [Moryiama K., 1965], any objection or opposition is perceived as an annoying hindrance; the response becomes a "hypertrophied spirit of contradiction" [Akiskal H. S., 1989] with captiousness, irritability, anger. More often these signs are quite labile [Nuller Yu. L., Mikhalenko I. P., 1988; Kryzhanovsky A.V., 1995], but they can determine the clinical picture of "irritable", "groaning" hypomania.

More often these signs are quite labile [Nuller Yu. L., Mikhalenko I. P., 1988; Kryzhanovsky A.V., 1995], but they can determine the clinical picture of "irritable", "groaning" hypomania.

In the autopsychic sphere , an elevated mood is expressed by an acceleration of the pace of thinking and speech, dispersal, distractibility, “a sense of the power of one’s own Self” [Petrilowitsch N., 1964], a surge of inexhaustible energy, and zealous efficiency. Even routine work is carried out with a special emotional upsurge, any problem seems to be solvable; there are many plans with unshakable confidence in their feasibility, attempts are made to immediately implement the plan.

In the foreground among the violations of the somatopsychic sphere - a sense of bodily comfort, special physical well-being, the highest flowering of strength, excellent health. Physical activity with good exercise tolerance and a high fatigue threshold is combined with a reduced need for rest. The surge of energy that lasts throughout the day is combined with a decrease in the need for sleep with sufficient depth. Somatopsychic manifestations of hypomania (as well as depression) with minimal severity of affective disorders proper can dominate the clinical picture (“mania without mania” - according to MA. Morozova, 1988).

The surge of energy that lasts throughout the day is combined with a decrease in the need for sleep with sufficient depth. Somatopsychic manifestations of hypomania (as well as depression) with minimal severity of affective disorders proper can dominate the clinical picture (“mania without mania” - according to MA. Morozova, 1988).

The typological subdivision of hypomania and their nosological assessment are not identical to the differentiation of depressions. Hypomanias (like manias) only in general terms repeat depressions, but are not their mirror image.

Clinical qualification of hypomania, like depression, is actually carried out on the basis of the predominance of certain disorders of the vital sphere ( simple, or cheerful; irritable, or angry, expansive hypomania ), somatopsychic ( euphoric hypomania ndria) and personal ( querulant, adventurous, dysphoric hypomania ). At the same time, the variants of the observed manifest (psychotic) states - mania with a jump in ideas, frenzy - mania furibunda, angry mania, mania with delirium do not develop.

With cyclothymia, productive hypomanias are often observed, characterized by increased activity that was not characteristic earlier (before the development of the phase), with a feeling of inexhaustible energy. Violations of the sleep-wake cycle are shallow and are manifested by some reduction in the duration of night sleep with early awakening, accompanied by a feeling of cheerfulness and readiness for activity. Ideatory processes are accelerated with a moderately pronounced distraction ™. Memory is sharpened (especially for past events), assimilation of what has been read improves. Often there is an increased need for communication, familiarity, social hyperactivity with pressure aimed at overcoming obstacles. Productive hypomania does not disrupt professional activity, and in a number of cases (and especially those that do not require long-term effort and painstaking, monotonous work aimed at a distant future) even stimulates it. However, an excess of activity (“flight of ideas” and “endless striving forward” - according to N. Ey, 1955) when combined with other signs of hypomania - talkativeness, carelessness, indiscretion, irresponsibility, distractibility, distractibility with switching to insignificant, irrelevant stimuli, it often turns out to be unproductive; the activity of patients turns into a chain of unfinished undertakings, unfulfilled obligations; in the foreground - an increased need for pleasure, the search for fresh, but superficial impressions. Such manifestations increase the risk of subjectively pleasant, but not conventional, actions that are not approved either in the family or in society (wastefulness, revelry, sexual intemperance), threatening negative consequences (hasty divorce or marriage, bankruptcy, etc.).

Ey, 1955) when combined with other signs of hypomania - talkativeness, carelessness, indiscretion, irresponsibility, distractibility, distractibility with switching to insignificant, irrelevant stimuli, it often turns out to be unproductive; the activity of patients turns into a chain of unfinished undertakings, unfulfilled obligations; in the foreground - an increased need for pleasure, the search for fresh, but superficial impressions. Such manifestations increase the risk of subjectively pleasant, but not conventional, actions that are not approved either in the family or in society (wastefulness, revelry, sexual intemperance), threatening negative consequences (hasty divorce or marriage, bankruptcy, etc.).

As special - atypical forms, characterized by the predominance of somatopsychic disorders, hyperthymic hypochondria are distinguished. In cases where the phenomena of sensory hypochondria predominate, increased affect, realized by unrestrained activity aimed at combating an imaginary illness, can be hidden behind the facade of pathological bodily sensations (vegetative dysfunctions, conversions, algopathies) - masked hypomania N. Bonnet (1978). In other cases, hypochondriacal polarization of hyperthymia can be carried out by attaching to a persistent, devoid of modulation, increased affect of phenomena ideoipochondria — euphoric hypochondria [Dubnitskaya E. B., Chudakov V. M., 1994; Leonhard K., 1957]. Isolated, but alien to normal bodily perception, pathological sensations with the properties of “mastering sensations” (persistent, relentless, pathological sensations that are not amenable to the influence of analgesics, alien to ordinary ideas, opposed to other bodily sensations and, as it were, contradicting the entire life experience of patients) become the source of overvalued obsession. An optimistic attitude to "overcoming the disease" is accompanied by attempts to "distance" from it with the help of noisy bravado, forced gaiety, and "black" humor.

Bonnet (1978). In other cases, hypochondriacal polarization of hyperthymia can be carried out by attaching to a persistent, devoid of modulation, increased affect of phenomena ideoipochondria — euphoric hypochondria [Dubnitskaya E. B., Chudakov V. M., 1994; Leonhard K., 1957]. Isolated, but alien to normal bodily perception, pathological sensations with the properties of “mastering sensations” (persistent, relentless, pathological sensations that are not amenable to the influence of analgesics, alien to ordinary ideas, opposed to other bodily sensations and, as it were, contradicting the entire life experience of patients) become the source of overvalued obsession. An optimistic attitude to "overcoming the disease" is accompanied by attempts to "distance" from it with the help of noisy bravado, forced gaiety, and "black" humor.

Hypomania can be formed both within periodically recurring phases, and acquire a persistent, protracted character. Affective disorders, which determine the picture of cyclothymic phases, are characterized by a distinct, delineated in time, different from the usual and noticeable to others, a rise in mood. Hypomanic phases, in comparison with manic phases, are usually not accompanied by persistent violations of social and professional status.

Hypomanic phases, in comparison with manic phases, are usually not accompanied by persistent violations of social and professional status.

With a protracted course, hypomania acquires a long-term persistent character ( chronic hypomania ). The states of chronic elevation are characterized by persistent affect and often proceed as productive hypomania, defined by patients as a period of "simple" and "easy" life. However, atypical variants are also observed: among them - chronic hypomania with overvalued formations, when inclinations and hobbies that did not play a significant role before become the meaning of all life; hypomania with rudimentary obsessions, idiopathic algias. Often a long period of consistently good health can be suddenly interrupted by a kind of "zigzag", when a relatively flat line of hypomania is replaced by transient somatization disorders (vegetative crises, conversions) and / or asthenia, vital fear, self-consciousness disorders with anxiety, fussiness, insomnia.

The position of chronic hypomania in the systematics of affective disorders needs to be clarified, since, unlike dysthymia, singled out as an independent diagnostic category, the distinction between chronic hypomania is not completed: one part of them, in accordance with modern concepts, is considered within the framework of constitutional anomalies - hyperthymia ("hyperthymic temperament"). ” - according to H. S. Akiskal, 1996), the other refers to endogenous pathology (“ psychopathic hypomania "- according to A. S. Tiganov, 1969; A. B. Smulevich, 1987, 1994).

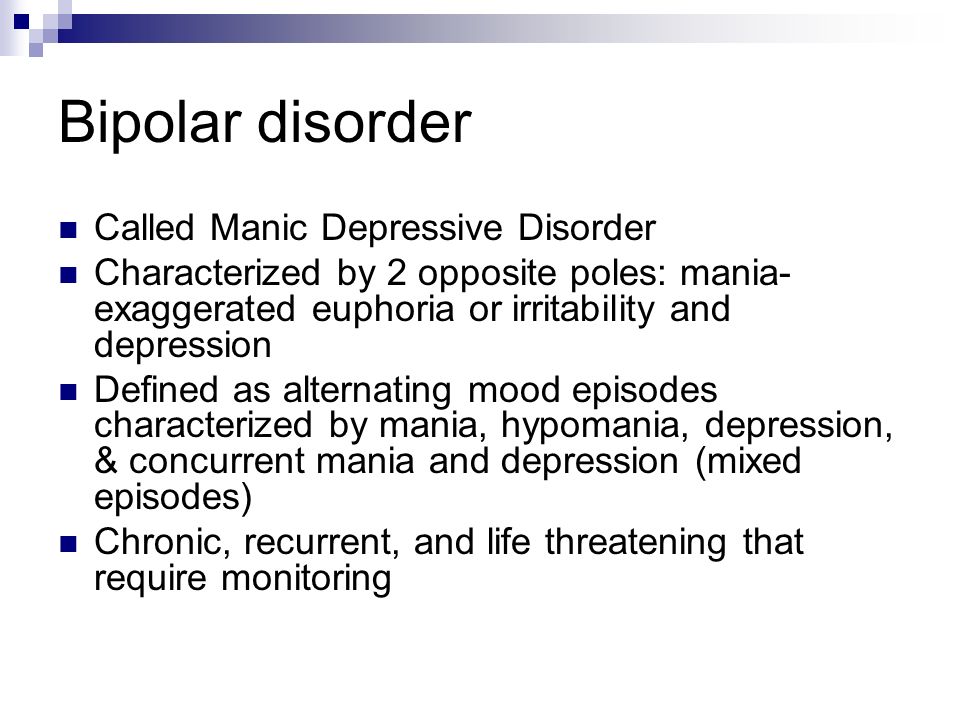

Bipolar disorder | Symptoms, complications, diagnosis and treatment

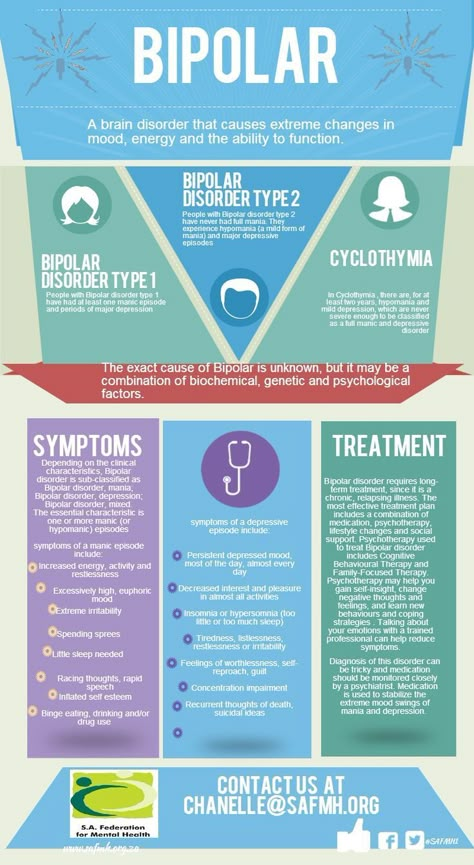

Bipolar disorder, formerly called manic depression, is a mental health condition that causes extreme mood swings that include emotional highs (mania or hypomania) and lows (depression). Episodes of mood swings may occur infrequently or several times a year.

When you become depressed, you may feel sad or hopeless and lose interest or pleasure in most activities. When the mood shifts to mania or hypomania (less extreme than mania), you may feel euphoric, full of energy or unusually irritable. These mood swings can affect sleep, energy, alertness, judgment, behavior, and the ability to think clearly.

When the mood shifts to mania or hypomania (less extreme than mania), you may feel euphoric, full of energy or unusually irritable. These mood swings can affect sleep, energy, alertness, judgment, behavior, and the ability to think clearly.

Although bipolar disorder is a lifelong condition, you can manage your mood swings and other symptoms by following a treatment plan. In most cases, bipolar disorder is treated with medication and psychological counseling (psychotherapy).

Symptoms

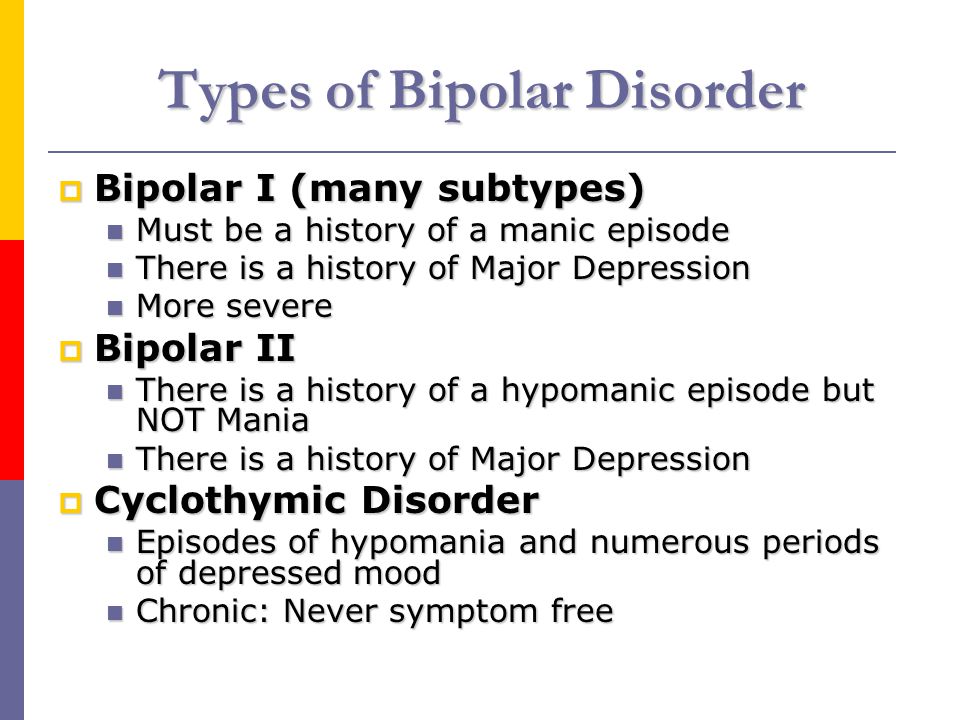

There are several types of bipolar and related disorders. They may include mania, hypomania, and depression. The symptoms can lead to unpredictable changes in mood and behavior, leading to significant stress and difficulty in life.

- Bipolar I. You have had at least one manic episode, which may be preceded or accompanied by hypomanic or major depressive episodes. In some cases, mania can cause a break with reality (psychosis).

- Bipolar disorder II. You have had at least one major depressive episode and at least one hypomanic episode, but never had a manic episode.

- Cyclothymic disorder. You have had at least two years - or one year in children and adolescents - many periods of hypomanic symptoms and periods of depressive symptoms (though less severe than major depression).

- Other types. These include, for example, bipolar and related disorders caused by certain drugs or alcohol or due to health conditions such as Cushing's disease, multiple sclerosis or stroke.

Bipolar II is not a milder form of Bipolar I but is a separate diagnosis. Although bipolar I manic episodes can be severe and dangerous, people with bipolar II can be depressed for longer periods of time, which can cause significant impairment.

Although bipolar disorder can occur at any age, it is usually diagnosed in adolescence or early twenties. Symptoms can vary from person to person, and symptoms can change over time.

Symptoms can vary from person to person, and symptoms can change over time.

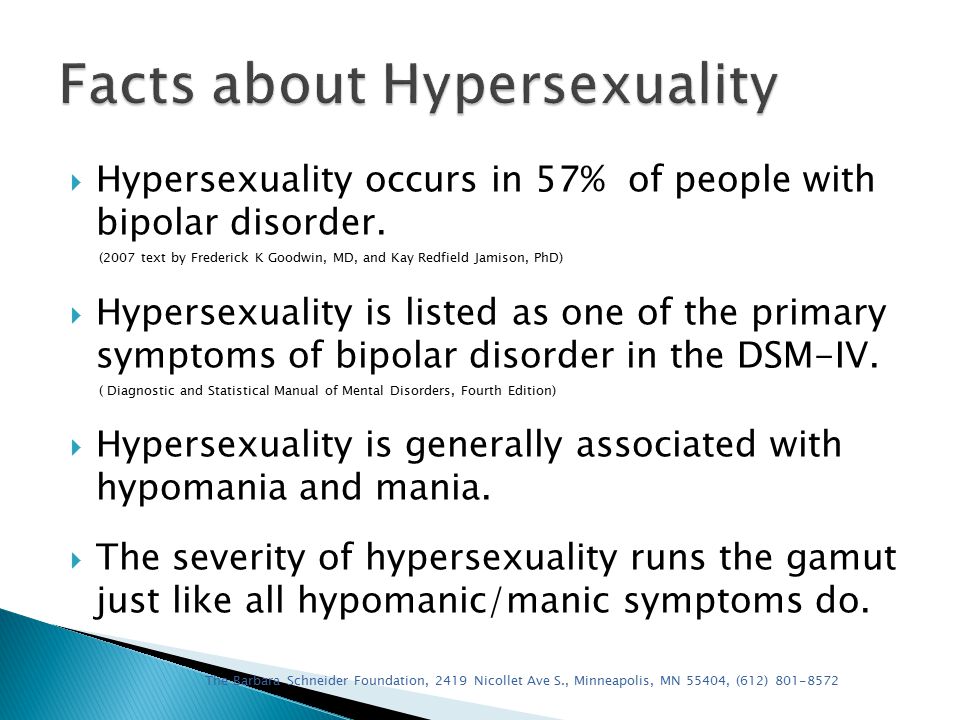

Mania and hypomania

Mania and hypomania are two different types of episodes, but they share the same symptoms. Mania is more pronounced than hypomania and causes more noticeable problems at work, school, and social activities, as well as relationship difficulties. Mania can also cause a break with reality (psychosis) and require hospitalization.

Both a manic and a hypomanic episode include three or more of these symptoms:

- Abnormally optimistic or nervous

- Increased activity, energy or excitement

- Exaggerated sense of well-being and self-confidence (euphoria)

- Reduced need for sleep

- Unusual talkativeness

- Distractibility

- Poor decision-making - for example, in speculation, in sexual intercourse or in irrational investments

Major depressive episode

Major depressive episode includes symptoms that are severe enough to cause noticeable difficulty in daily activities such as work, school, social activities, or relationships. Episode includes five or more of these symptoms:

Episode includes five or more of these symptoms:

- Depressed mood, such as feeling sad, empty, hopeless, or tearful (in children and adolescents, depressed mood may manifest as irritability)

- Marked loss of interest or feeling of displeasure in all (or nearly all) activities

- Significant weight loss with no diet, weight gain, or decreased or increased appetite (in children, failure to gain weight as expected may be a sign of depression)

- Either insomnia or sleeping too much

- Either anxiety or slow behavior

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt

- Decreased ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness

- Thinking, planning or attempting suicide

Other features of bipolar disorder

Signs and symptoms of bipolar I and bipolar II disorder may include other signs such as anxiety disorder, melancholia, psychosis, or others.