Supporting bad behavior

How to Stop Enabling Codependency

Are you an enabler?

An enabler is someone who encourages or allows negative or self-destructive behavior in another.

Here are some examples of enablers:

- Giving money to someone who has a gambling problem

- Lying to cover up bad behavior for someone else

- Making excuses for someone’s bad behavior

There is a very fine line between enabling and helping. When you help someone you do something for them that they cannot do for themselves or as an act of generosity. When you enable someone, you do something for them that they should be doing themselves or is hurting them not to do.

Do you have someone in your life that complains about the same problems again and again, but does nothing to change them? You might be enabling them.

How Enabling Works

You have offered help, suggestions and advice, but nothing ever really changes. And every time you see them you have to hear about the same problems over and over again—the worst part is they don’t see their patterns. They think their issues are unsolvable, completely different every time and extremely interesting.

I do. I have this person in my life and it is driving me crazy. In fact, over the years I have had a few people like this. Can you relate?

- The girlfriend who always dates the bad boy and every time he cheats on her, treats her like sh*t or dumps her for someone else.

- The wantrepreneur who has another amazing business idea that will take off and be the next big thing. But it never does.

- The drama magnet who can never make rent, is always short on cash to pay the check at dinner and runs out of gas so you always have to drive.

- The addict who asks for money, excuses and cover-ups from you.

I’m sorry if this post is sounding angry. I am a little angry, but I’m mostly frustrated. I’m frustrated because I care about this person so much and it kills me to see them ignorant to their own patterns. I love them and I want the best for them so it breaks my heart that they don’t realize that they are in a cycle of the same problem over and over again. They are stagnant—and blind to their own stagnation.

They are stagnant—and blind to their own stagnation.

I call this person a hamster. They are lovable, but they are stuck in a cage going around the same wheel over and over again without realizing they aren’t going anywhere. If you have a hamster in your life, you know how exasperating it is to desperately want to help someone who will not help themselves.

Your desire to help someone is not enough. They have to want to help themselves.

If you continue trying to help someone who is not changing then you are not helping, you are enabling.

↑ Table of Contents ↑

The Cycle:

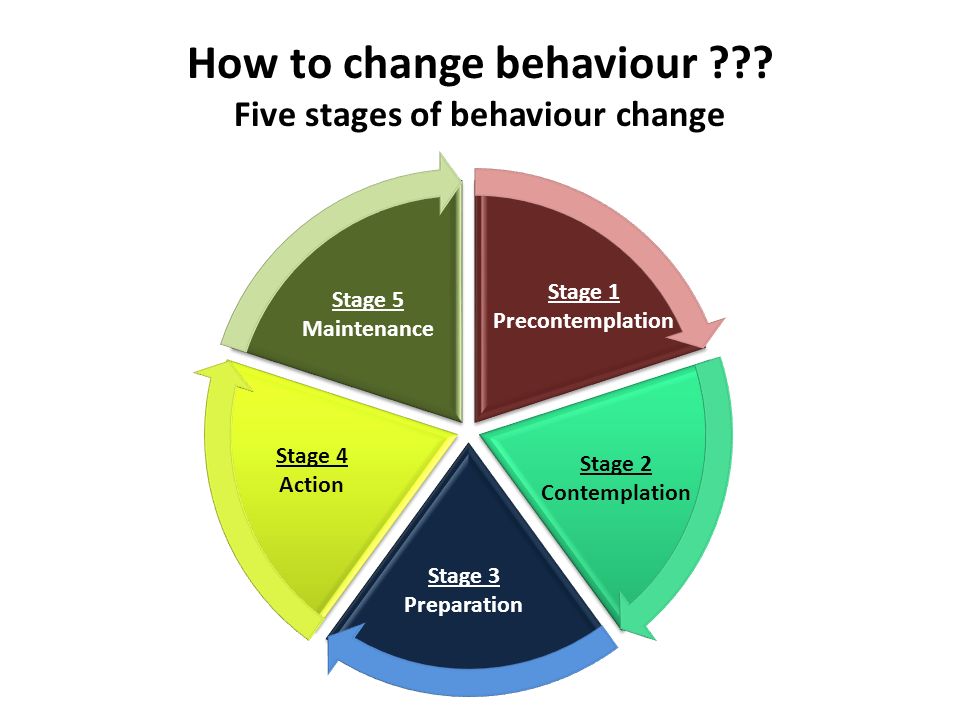

I have noticed there is a 4 stage process of how enabling can happen:

- They tell you about a problem they are having. You offer advice. They nod and say they’ll try it.

- The problem comes up again. You ask about the advice you gave. No, that wouldn’t have worked. You offer sympathy and more advice. They take the sympathy, but not the advice.

- They want to re-hash a ‘new’ version of the problem. You mention it sounds similar. Could this be a pattern? They get mad. You decide to not try to help and just listen.

- There is an update on the problem they want to talk to you about. They spend a long time venting. This time it’s worse and has bigger consequences. Any advice is politely ignored as they continue to vent. You worry that by listening you are actually enabling the problem. You get frustrated and bored.

Repeat.

What do you do when this 4 stage process has repeated itself 5 or 6 times? A dozen? Is this still a healthy relationship? Is this still a healthy person? This might be the start of a co-dependent or enabling relationship.

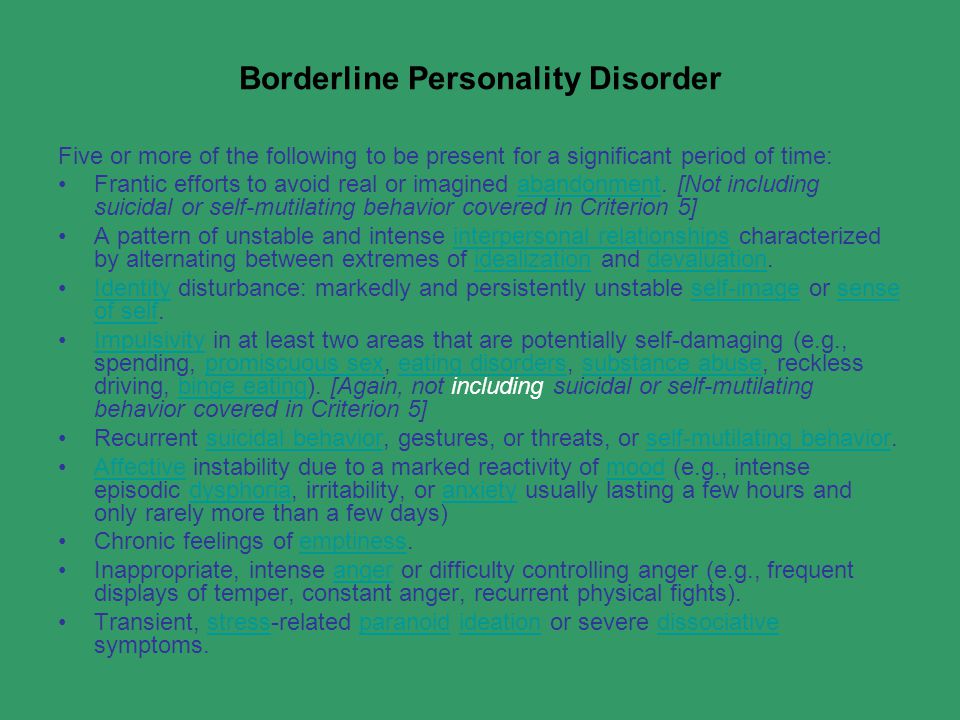

Codependency is a relationship where one person enables the other person’s bad behavior, poor mental health or even addiction. Typically a codependent relationship is marked by excessive reliance on one another and a constant seeing of approval.

Why does this happen? They have damaging, but powerful self-narratives.

↑ Table of Contents ↑

The Power of the Self-Narratives

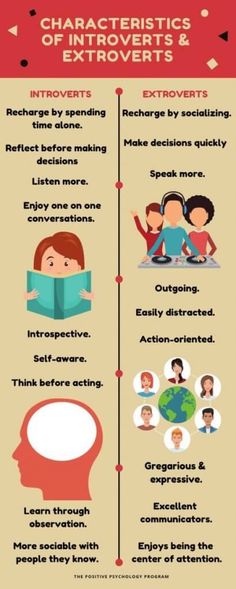

A self-narrative is the story we tell ourselves about ourselves. Do you see yourself as a survivor? A hero? Unlucky? Unique?

Researcher, Dan McAdams has found that most of us have crafted narratives and stories about our lives. This is how we craft our identity and define the forces that shape us. Some examples:

- The Warrior Narrative: This person believes they are a survivor and have to fight for everything they want. They believe nothing has or ever will come to them easy. Typically, they have had difficult past experiences that they have survived and come out stronger. They say things like, “My whole life has been a battle,” or “I have fought for everything I have ever gotten” or “Nothing comes easy to me.”

- The Nurturer Narrative: This person sees themselves as a care-taker, a giver and a nurturer.

They might have had a number of siblings or fighting parents where they played peacemaker in their home growing up. Or they are in a job where they have to put their own needs aside for others. They typically will always say yes to others even if it is not in their best interest. They tend to overcommit and be people pleasers.

They might have had a number of siblings or fighting parents where they played peacemaker in their home growing up. Or they are in a job where they have to put their own needs aside for others. They typically will always say yes to others even if it is not in their best interest. They tend to overcommit and be people pleasers. - The Adventurer: Some people see their self-narrative like a character in a great novel. They thrive in unconventional situations and define themselves by doing unique things. They might have had an unusual upbringing or eclectic tastes and feel this defines them and their identity, therefore they continue to make unique choices that further differentiate them.

↑ Table of Contents ↑

Why We Self-Define

Here’s the thing about self-narratives: they are self-defined. We craft a story about ourselves and then continue to make choices and behave in ways that further carry out the narrative. For example, if a hamster has the Victim Narrative, they always see themselves as a martyr or defeated. Then they pick jobs or activities that continue to put them in this place. I think this is why some hamsters have the same problems over and over again. Their problems are annoying and difficult, but they are also playing into their narrative.

Then they pick jobs or activities that continue to put them in this place. I think this is why some hamsters have the same problems over and over again. Their problems are annoying and difficult, but they are also playing into their narrative.

Enablers often are woven into someone’s self-identity.

This is how self-narratives work when a hamster won’t change:

- The Warrior Narrative: A warrior has a job where the boss hates him. You tell him to apply for a transfer with a new boss, but this means having a non-competitive work environment. A warrior isn’t used to having nothing or no one to fight about, this isn’t in their self-narrative. So they complain, but they keep the job because it’s what they know.

- The Nurturer Narrative: A nurturer is in a relationship where she is taken for granted. She does all the housework and is basically a servant to her partner.

You bring this up and encourage her to stand up for herself. Although she wants to, standing up for herself and putting her needs first is against her self-narrative. So she stays in a relationship that is unhappy but familiar.

You bring this up and encourage her to stand up for herself. Although she wants to, standing up for herself and putting her needs first is against her self-narrative. So she stays in a relationship that is unhappy but familiar. - The Adventurer: Your adventurer friend is always complaining about not being able to pay down student debt or afford dinners out. He can’t keep a steady job because they are all so boring. He would prefer to travel the world—great, you say! Then get a virtual job or save up more before traveling. Your idea of responsible is his idea of boring and too conventional. He keeps job hopping and complaining about the bills. He is an adventurer—a 9 to 5 job (even virtual) would kill his personal brand.

↑ Table of Contents ↑

Unhappy But Familiar

Self-narratives are defining, they are also comfortable. Children who have been abused often end up in abusive relationships as adults. Why? I think this comes down to a self-narrative. They have a self-narrative that casts them in the horrible role of abuse. They don’t like it, but they know it.

They have a self-narrative that casts them in the horrible role of abuse. They don’t like it, but they know it.

For some, predictably terrible is better than an unpredictable unknown.

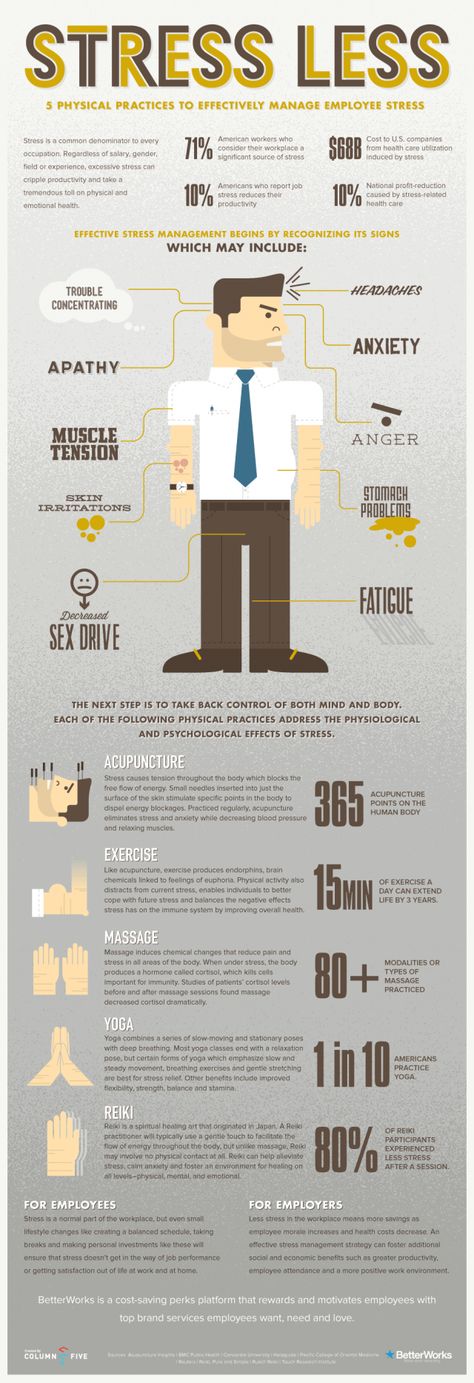

I think the reason why some people can’t change is because they are fighting two extremely strong forces:

#1: Their Identity

They are afraid of changing something because it’s not how they see themselves. By acting different, they might get something different and this feels scary.

↑ Table of Contents ↑

#2: Fear of Change

Change is scary. We know what we like and we like what we know. This keeps us in a very limited mindset and prevents any kind of growth.

If you always do what you’ve always done, you’ll always get what you’ve always got.

Henry Ford

So what to do? I think the answer comes down to compassion.

- Don’t get angry, get curious. You have this person who won’t change, try to identify the forces at play.

What do you think their self-narrative is? Is their fear of change greater than their desire to end their problems?

What do you think their self-narrative is? Is their fear of change greater than their desire to end their problems? - Help them change the narrative. Instead of giving them advice on changing the behavior (the symptom) try helping them see the narrative (the cause). Ask them how they see themselves. Ask them what role they play in their relationships, job and friendships. Ask them what it would feel like if the roles were reversed or if someone could wave a magic wand.

- Let go. I have come to the sad conclusion that some people cannot be helped.

Everyone can be loved, but not everyone can be changed.

Enablers can stop enabling when they admit to themselves that someone might not be able to change — and they might be blocked from changing by the enabling behavior.

I tend to take it very personally when people don’t take my advice or people close to me keep making the same mistakes over and over again. But the truth is, it’s not about me or the quality of my advice. It is about their bravery and courage to see truth and make hard choices that bring change.

But the truth is, it’s not about me or the quality of my advice. It is about their bravery and courage to see truth and make hard choices that bring change.

All you can do is be the mirror for them to see their narratives and the support if they decide to leap into the fear of change. It’s not easy: We can’t change people, but we can change behavior—slowly, lovingly, compassionately.

↑ Table of Contents ↑

How to Change Bad Behavior

You know who is an expert in changing bad behavior? Dentists. They have to convince people to floss, brush and treat their teeth well — a lifelong challenge. Let me tell you how my dentist helped change my bad behavior…

First, I should mention that I do not have a great track record with dentists. I freak out at needles, gag when cotton chunks come near my mouth and am disgusted by every flavor of polishing paste (really, can someone disrupt the fluoride industry already?!). I’m also a terrible patient. Every year since I have had teeth, this is how my dental appointment goes:

Every Dentist I’ve ever had: Vanessa, I can tell you’re not flossing. You need to floss more. If you don’t floss you will get more cavities. Maybe an electric toothbrush will help? You have to get it into your nightly schedule. I will know the difference next time you come in. Floss or else!

You need to floss more. If you don’t floss you will get more cavities. Maybe an electric toothbrush will help? You have to get it into your nightly schedule. I will know the difference next time you come in. Floss or else!

And this is always my response:

Me: I know. I know. I know. I don’t want the electric toothbrush, but I will take the free floss. I’m sorry. I know.

And then I leave. And nothing changes. In a good month, I floss once per month. A few months ago, I decided to switch to a new dentist a little closer to my house. She—Dr. Vu at Wellness Dental begins my appointment with an exam. Just like normal. But then, everything changes:

Dr. Vu: Vanessa, you have beautiful teeth. I can tell you brush every day. Maybe you even floss once per month? That’s great! That’s more than the average person. I am really happy to see that.

Me: I do?! Yes, I do! I floss once per month and I always brush twice per day.

Dr. Vu: I can tell, that is wonderful and a really good set of dental habits. Now, I see you have a few very small cavities. I think that since you take care of your mouth, we might be able to fight these and definitely prevent more from coming. But we will have to fight them together.

Me: Yes! Yes, let’s fight them together! How can we do it?

Dr. Vu: Here’s what I am thinking. First, I want you to see your progress. I am

going to take a picture of every single tooth (cool wand device brought out) and that way you can see exactly the worrisome areas I am talking about. Then when you come back for your next cleaning, we can take new pictures and check your progress to see how we are doing. This is what I think we can fix…

[She pulls up a picture of my tooth on the screen and shows me exactly where there is a tiny dark spot]

Me: Oh wow, I didn’t know you could see it. So you think that I can reverse the damage without drilling?

Dr. Vu: Yes definitely! Enamel can heal if you treat it right, so we are going to go on full attack—last resort is drilling. First, we get you an electric toothbrush, that will really help. Second, we up your flossing. Even once per week would be a tremendous change. I am going to give you some free boxes. Lastly, I am going to give you some prescription fluoride toothpaste.

Vu: Yes definitely! Enamel can heal if you treat it right, so we are going to go on full attack—last resort is drilling. First, we get you an electric toothbrush, that will really help. Second, we up your flossing. Even once per week would be a tremendous change. I am going to give you some free boxes. Lastly, I am going to give you some prescription fluoride toothpaste.

Me: Ok, definitely I want the electric toothbrush and I think one time per week is doable, but I bet I can do more if I really focus on it.

Dr. Vu: Absolutely! I have no doubt. When you come back we will compare the pictures and see how we did! I am even going to score each tooth with a number for gum health so we can see how much the flossing is helping.

Me: Ok! I hope I can improve my score on most of them.

Dr. Vu: I know you can!

I have flossed almost every day since this first appointment. I did not have to get those two cavities filled because we repaired the damage and I improved my overall teeth scores from average to excellent. For the first time in my life, I don’t dread going to the dentist.

For the first time in my life, I don’t dread going to the dentist.

This experience demonstrates far more than how to encourage teeth health. It speaks to an essential part of human nature: Behavior Change.

↑ Table of Contents ↑

Why We Want to Change People

We can’t help it: We love to try to fix the people in our life. We give advice to a friend. We tell a family member how they could do something better. We try to suggest, fix and change a partner for the better. Sadly, even though we mean well, changing people usually doesn’t work. In fact, it might even make the person you are trying to help angry at you. This is classic enabling.

Why are you trying to change me?

I know better!

You don’t understand, my situation is different.

Stay out of it!

Mind your own business.

Yet, we keep trying to ‘help.’

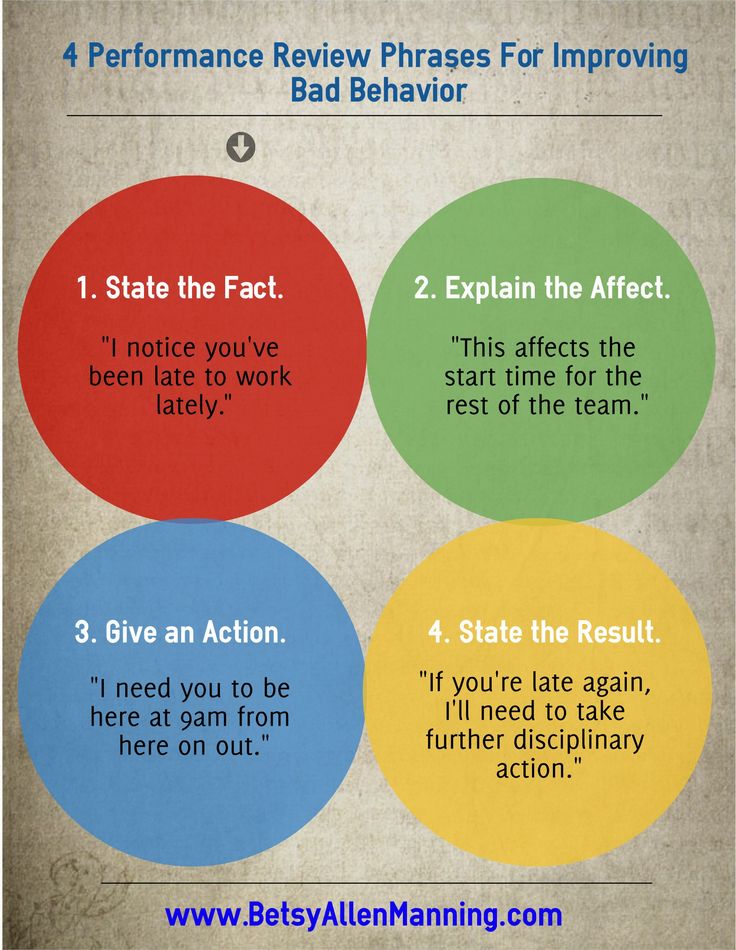

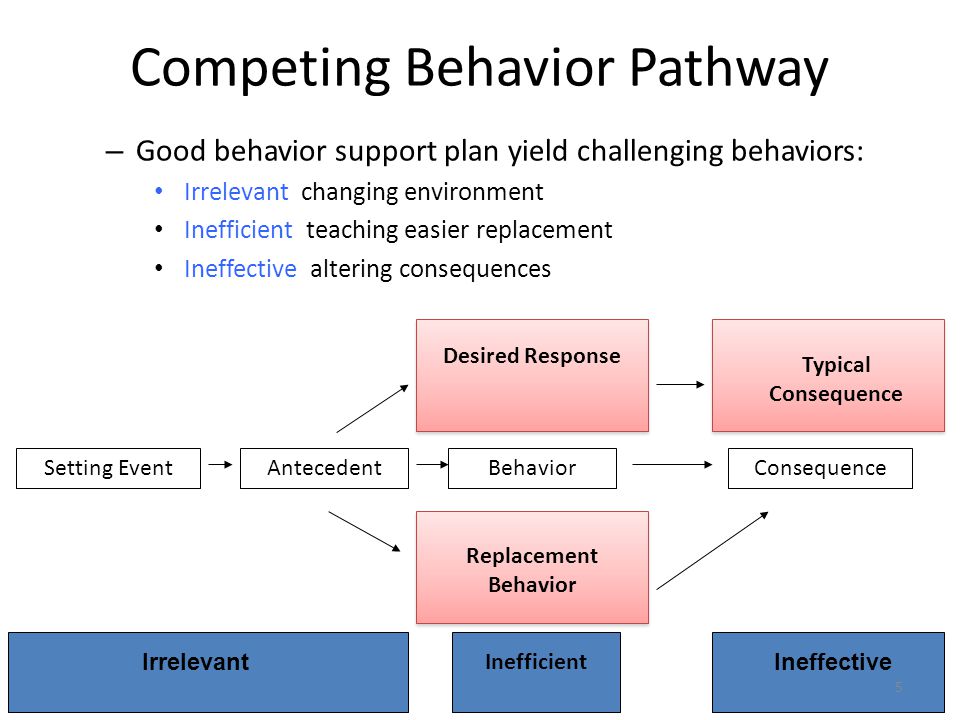

Think of how the dentist tried to change my bad flossing habits. These are the common strategies people often try. You might be enabling because you are using the wrong tactics. Here’s how enablers trap themselves in codependent relationships:

You might be enabling because you are using the wrong tactics. Here’s how enablers trap themselves in codependent relationships:

↑ Table of Contents ↑

Tactic #1: Be Helpful

As a dentist I would recommend flossing more. You know what really helped me? I have some great advice for you. I just want to help! If I were you I would just try to…

Someone in your life is doing something wrong. You think you could help them out with some advice—if only they could be more like you or do it more like you would do it, everything would be easier! So you offer advice, suggestions, send them tips, articles and books. Sometimes this works, but often it doesn’t. This person comes back to you with the same problems over and over again.

↑ Table of Contents ↑

Tactic #2: Incentivizing

My mother: If you floss every night and don’t fight with me about brushing I will get you a new Hula Hoop!

Parents do this a lot with children, but we also do this with colleagues and employees. We offer a reward for behavior change. This can work in the short term, but never holds up in the long term as incentives hold less value over time.

We offer a reward for behavior change. This can work in the short term, but never holds up in the long term as incentives hold less value over time.

↑ Table of Contents ↑

Tactic #3: Threatening

If you don’t floss, you will get more cavities! If you don’t start saving money, we are going to have to sell the car. If you don’t lose weight, you’ll have to buy all new clothes.

Fear mongering and threatening is a typical tactic used by dentists, parents and bosses alike. But the stick is less effective than a carrot (and a carrot wasn’t that all effective in the first place, see above). Threatening only makes you the target of someone’s animosity. People who want to lose weight or eat less calories already know what’s at stake. Threats only add stress, fear and anxiety. This might work temporarily but could destroy your relationship.

↑ Table of Contents ↑

Tactic #4: Pleading

Do it for me! Do it for your future kids! Think of all the money we have spent, don’t let it go to waste!

When we are really desperate for someone’s behavior to change, we plead with them. We beg them to change and point to a higher purpose—the future, money, religion, children. We hope that by tying the mission to something bigger it makes people pay attention. Typically this only makes someone feel more alone, not more inclined to change.

We beg them to change and point to a higher purpose—the future, money, religion, children. We hope that by tying the mission to something bigger it makes people pay attention. Typically this only makes someone feel more alone, not more inclined to change.

↑ Table of Contents ↑

Tactic #5: Shaming

Your oral hygiene is below average. Your weight is disgusting. Aren’t you embarrassed by your debt problem? I would be humiliated if I were you! I would never show up late all the time, it is so rude.

Shaming is a standard tactic for behavior change—you see it a lot on weight loss reality shows for example. The problem is that shaming can work, but it has devastating consequences on someone’s self-worth and long-term health. When you shame someone into changing their behavior they work out of a negative space and attack their own sense of worth. Even if they end up changing the behavior they often have a hard time getting back their self-esteem.

Ok, so all of these tactics don’t really work in changing someone’s behavior. What does?

↑ Table of Contents ↑

How to Stop Enabling

Dr. Vu did something powerful with me that day in her office. She showed me how to really get someone to change behavior.

Here’s what we can learn from her on how to stop enabling and start changing:

↑ Table of Contents ↑

Step #1: Pride

Dr. Vu started out by invoking feelings of pride. She told me I had beautiful teeth. She also mentioned that I do floss and that was ‘better than average.’ This immediately made me feel proud of the little I do floss as opposed to ashamed about how much I don’t. This is a major difference. Pride makes us want to rise to do more, it makes us feel powerful and we want to live up to the definition. If you want to change someone’s behavior make them feel proud.

- Point out what is going well

- Praise them for what they are doing right

- Invoke their feelings of pride so they live up to the label

↑ Table of Contents ↑

Step #2: Togetherness

Dr. Vu also uses “we” more than “you.” It took me a while to notice this, but when I did I realized it made me feel calmer. She wasn’t accusing me of bad dental hygiene, nor was she saying I was on my own. In fact, she was putting me on her team. She was saying that we would fight cavities together and I was not alone in the battle. If you want to change someone’s behavior put them on a team.

Vu also uses “we” more than “you.” It took me a while to notice this, but when I did I realized it made me feel calmer. She wasn’t accusing me of bad dental hygiene, nor was she saying I was on my own. In fact, she was putting me on her team. She was saying that we would fight cavities together and I was not alone in the battle. If you want to change someone’s behavior put them on a team.

- Say ‘we’ not ‘you’

- Join their cause

- Find them people or allies to change with

↑ Table of Contents ↑

Step #3: Progress

The next thing Dr. Vu did was to help me catalogue my progress. She took pictures of each tooth and gave my gums a score. This gave me a benchmark—it’s like seeing how much you have in savings or weighing yourself. Specific, measurable goals are always easier to achieve. I could see the little dark spot on my tooth—and I wanted to get rid of it. I could see my teeth scores—and I wanted to improve them. She made my target defined. Other dentists would just tell me to floss more. I had no idea if it was working or not and my only measure was if I didn’t get any cavities. That’s not enough for sustained behavior change! Every night when I floss, I imagine how much my score will improve and that little dark spot fading. That is a powerful motivator and mental image to floss more.

I had no idea if it was working or not and my only measure was if I didn’t get any cavities. That’s not enough for sustained behavior change! Every night when I floss, I imagine how much my score will improve and that little dark spot fading. That is a powerful motivator and mental image to floss more.

- Define a measurable benchmark

- Track progress

- Make it easy to visualize change

↑ Table of Contents ↑

Step #4: Tools

The last thing Dr. Vu did was give me specific tools and steps. I had heard all of these before, but never in such a direct, prescriptive way. When I heard them before they felt like annoyances. But after Dr. Vu’s first 3 steps, they felt like powerful weapons! She broke it down into 3 steps and promised a measurable outcome. I was hooked.

- Give steps

- Provide helpful tools

- Make a clear path to change

These 3 steps to behavior change work in any kind of environment. For example, let’s look at a parent trying to get their child to clean their room more:

↑ Table of Contents ↑

Tactics that don’t work to stop enabling:

- Helpful: If you cleaned your room more, you would be able to get ready for school on time.

- Threatening: If you don’t clean your room you will be grounded!

- Incentivizing: If you clean your room every day for the next month I will buy you a new video game.

- Pleading: I am begging you to clean your room, it would make me so happy for when guests come over!

- Shaming: Your room is disgusting! It is shameful and a total pigsty, I would be so embarrassed to have friends over if I were you.

↑ Table of Contents ↑

Steps that do work to stop enabling:

- Pride: Thank you for always packing your backpack at night, it saves us so much time in the morning. You are so organized with your school stuff. I also really like the new posters you made for your walls. They look awesome, your friends will love them when they come over.

- Togetherness: I would love to help you get your room clean. What can we do together to make that work? How about we use the dishes and laundry schedule to help?

- Progress: I am going to keep a calendar of laundry days and do the dishes every morning.

This way you know exactly when to bring things down and when I will be coming up there—so you don’t feel like I am dive bombing your room randomly. I am going to keep track of when you bring down yours. If we can do it 3 of the 7 days of the week that would be great.

This way you know exactly when to bring things down and when I will be coming up there—so you don’t feel like I am dive bombing your room randomly. I am going to keep track of when you bring down yours. If we can do it 3 of the 7 days of the week that would be great. - Tools: I am going to get you your own laundry basket. I also got you a Nalgene bottle for your room you can refill upstairs instead of using the water glasses. That should save a lot of time. I also just ordered these sheets that make it easier to strip and make the bed. They are pretty cool.

This is a totally different approach to behavior change. It goes against our instincts, but actually gets results without making people feel bad in the process. We all have bad behavior, it’s great to get some compassionate help sometimes. Use these steps to help someone break free of their bad habits. Oh, and thanks so much Dr. Vu! You are the best =)

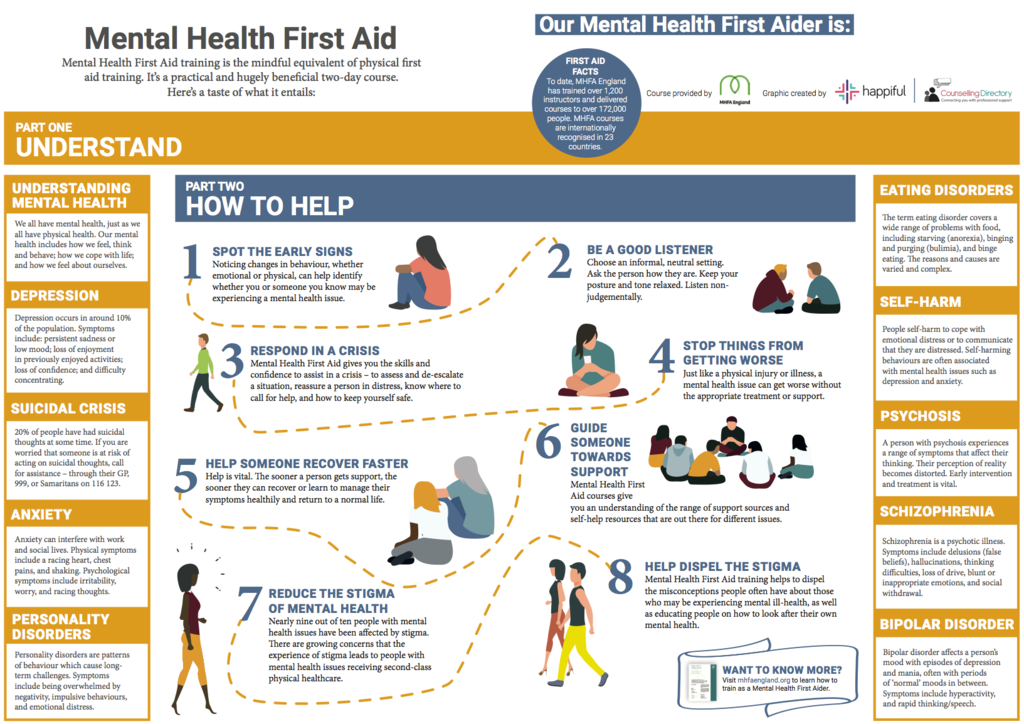

What Is the Difference Between Supporting and Enabling?

It is human nature to want to care for and help someone you love. There is a very fine line, however, between being supportive of someone you care about and enabling bad behaviors. Often it can be very difficult to see the line at all. Because of that people frequently end up on the wrong side of the line and don’t even know it.

There is a very fine line, however, between being supportive of someone you care about and enabling bad behaviors. Often it can be very difficult to see the line at all. Because of that people frequently end up on the wrong side of the line and don’t even know it.

Whether it is alcohol, other selfish behavior, or general irresponsibility, allowing someone to continue to choose damaging behaviors by being passive, or assisting in them through your own actions, only deepens the damage. When your intention is to help, acting as an enabler does just the opposite.

So what is the difference between supporting and enabling? Simply stated supporting or helping includes assisting with things that he or she is incapable of doing for him or herself, or doing things that help facilitate them gaining control of their behaviors and life. Enabling behaviors, on the other hand, keep someone from dealing with the negative consequences of their actions. Not dealing with these consequences gives the impression that their behavior is somehow acceptable.

For instance, a parent who let’s a child skip school because they are late with an assignment is enabling irresponsibility. A partner who accepts a hangover as being “sick” is enabling alcohol abuse and overlooking the symptoms, and the partner who never says no and is taken advantage of time and again, is enabling selfish behavior. These people may feel as though they are being supportive, helpful, or accepting, but the reality is that they are causing the behaviors to worsen.

Enablers will also often try to solve the problems for the people they are trying to help. Solving their problems makes the enabler feel as though they are doing something good for the person they care about. The truth, however, is that they are hurting them. Enabling behavior that needs to change will also create a negative dynamic in the relationship. The person needing the help becomes unable to live their life in a healthy, independent and responsible manner, and therefore becomes dependent on others. The enabler then takes on responsibilities that are not truly theirs. This can ultimately create resentment in the enabler and a very unhealthy and unbalanced relationship overall.

The enabler then takes on responsibilities that are not truly theirs. This can ultimately create resentment in the enabler and a very unhealthy and unbalanced relationship overall.

If you are wondering whether you are being helpful or enabling, ask yourself the following questions.

- Do you find yourself making excuses for someone else? “Oh, he was just sick today,” “She meant to turn it in, but she was just too busy,” “He was just blowing of some steam.”

- Do you regularly put your own needs second because someone else needs your attention? This can be normal with a newborn, but in most instances is unhealthy.

- Do you have a feeling (or know full well) that the behavior you are seeing is unhealthy or irresponsible?

- Have you lied (or routinely lie) for someone?

If you have answered yes to any of these you may very well be enabling behaviors that need to change.

So what should you do? In a word — stop. That sounds easier than it actually is. As mentioned earlier, it is in our nature to want to help those we care about. And it takes work and self-control to allow someone to suffer the consequences of their own choices. No parent wants to see their child fail and no person wants to see someone they love suffer the effects of bad decisions. But “helping” and “supporting” in these situations often requires you to do just that.

As mentioned earlier, it is in our nature to want to help those we care about. And it takes work and self-control to allow someone to suffer the consequences of their own choices. No parent wants to see their child fail and no person wants to see someone they love suffer the effects of bad decisions. But “helping” and “supporting” in these situations often requires you to do just that.

So you may need to become the parent who makes the child explain to their teacher why their assignment isn’t done and accept a poor grade. Or the spouse who calls the hang-over alcohol abuse and insists on change, or the partner that requires selfish behavior stop and insists on balance in the relationship. These roles are not easy and you may find that you need help yourself in enacting them. By putting a stop to the enabling behavior, however, you will ultimately make a true difference in someone’s life. You will help them live life in a self-sufficient and healthy way.

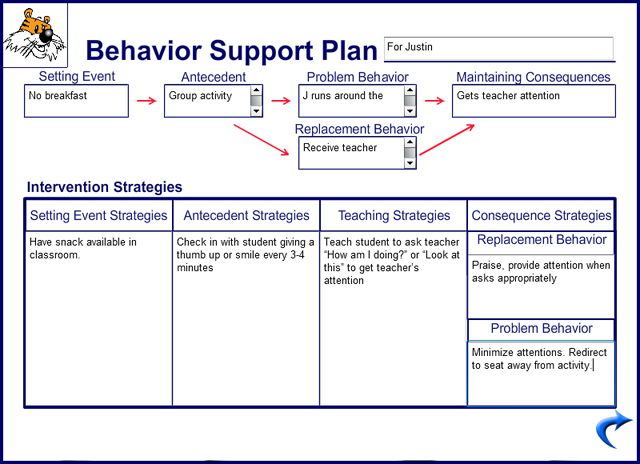

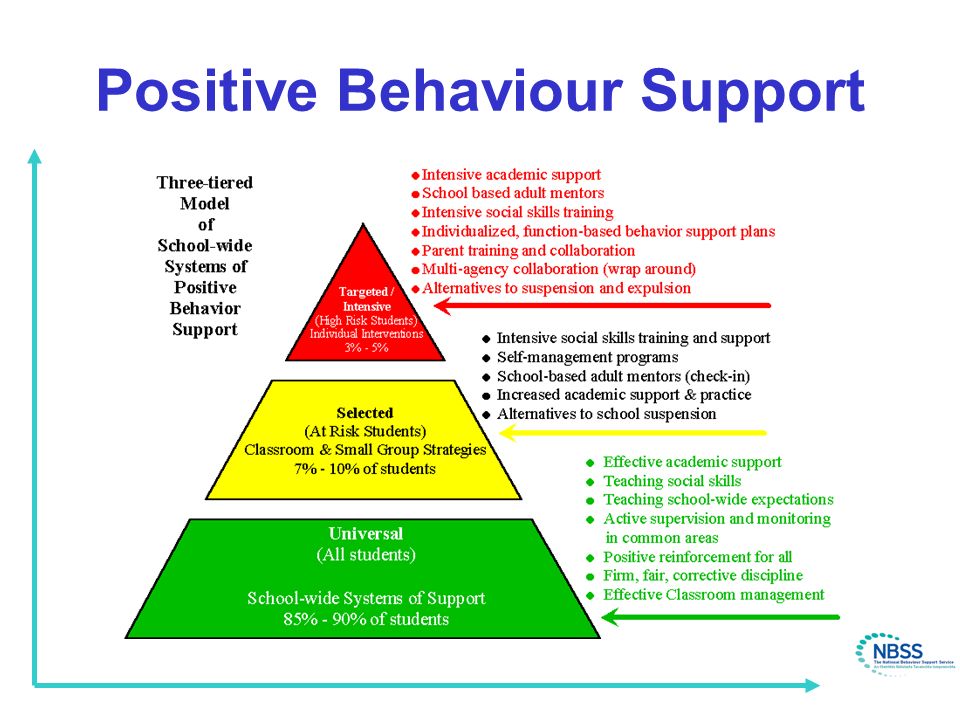

Bad Behavior from a Positive Parenting Perspective - Child Development

Do your children harass you with their bad behavior? If you were asked to describe your toddler by continuing the sentence "He's a good kid, but. .." would you use words like "naughty", "cryy", "unmotivated", "disrespectful", "angry", or "demanding"? ”, adding only a few good words to the description?

.." would you use words like "naughty", "cryy", "unmotivated", "disrespectful", "angry", or "demanding"? ”, adding only a few good words to the description?

If negative thoughts are born in your head most often, and positive thoughts much less often, then the first thing to understand is that it is quite natural. We, parents, are also people, which means we tend to be in constant search of what is wrong with our child, and then diligently focus on this “flaw” in order to certainly “fix” it for the better. One way or another, this process reassures us, we believe that by doing so we increase the child's chances of surviving in this very difficult world for many years to come.

The problem, however, is that if we spend most of our time worrying and dwelling on the negative, trying in every possible way to shape our children to our ideal image of them, we miss their valuable positive traits that are already inherent in them . The good news is that if you want to positively influence your child and keep your communication open, it will be more effective for you to use a balanced view of things. I'm going to help you "change the lenses on your glasses" so you can see the negative sides of your child in a more positive light - or at least a clearer and more understandable one!

I'm going to help you "change the lenses on your glasses" so you can see the negative sides of your child in a more positive light - or at least a clearer and more understandable one!

Here are five rules to get you off to a good start:

Rule #1: Stop looking for what you're afraid of.

Parents, as tension builds up, may develop a tendency to look for evidence of what they fear. I had a friend who was so afraid that her son would be a social loser that she couldn't even sleep. She herself had been in some kind of social struggle all her life. Once, in order to somehow cope with her fear for her son, she went to the playground, where he was supposed to be at that time, specifically to find evidence of her negative belief that he had no friends.

Of course, when you're looking for evidence of your fearful belief, you'll find certain things - and immediately identify them as such. When she pulled up, he was standing all alone at the edge of the tarmac while all the kids were playing at the opposite end. She got out of her car and ran to her son almost in horror: “Why are you standing here all alone and not joining other children?” He said, "Mom, can you get out of here? I am a goalkeeper and I am in the heat of the game, this is football!”

She got out of her car and ran to her son almost in horror: “Why are you standing here all alone and not joining other children?” He said, "Mom, can you get out of here? I am a goalkeeper and I am in the heat of the game, this is football!”

This story illustrates very clearly the extent of what anxiety can do to us - it can make us look for evidence of what we fear, look for it and find it, after which we begin to treat it as something real, like to a fulfilled prophecy. And if this way of responding becomes habitual, taking away from you the opportunity to teach your child how to interact effectively with other children, you will inadvertently nurture in him that slightly negative that is. In other words, what you are trying to prevent will happen!

Sometimes we turn a certain behavior of a child into a problem, about which we immediately begin to worry intensely and lose sight of logic and facts. When this happens, even positive character traits can become negative. An important skill that parents should learn is to stop looking for what they are afraid of. This applies not only to education, but to the whole life.

This applies not only to education, but to the whole life.

Rule #2: Change your lenses.

We can also turn a positive into a negative when we can't see the positives hidden under the guise of irritable and unpleasant behavior that deprives us of inner balance. How often do we worry that children do not listen to us. We do not like that they contradict us, go against our opinion, do not agree with what we want from them. When they say "no" or refuse to comply with our request, it just drives us crazy. It is quite customary and natural in this case to get angry and classify the child's behavior and his attitude towards us as negative, i.e., again, one that needs to be corrected. But, despite the inertia, the best option for us would still be to think about the result of such behavior (refusal to do something) - about the actual characteristics of the child and not necessarily bad.

By changing the "lenses" in our imaginary glasses, instead of trying to change our children, we can try to understand their confrontational tendencies, evaluate them and understand them. It will be difficult and tiring, but worth it. Look at the situation this way: we want our children to grow up and become self-reliant and independent from adults. The rebelliousness and confrontation you see in behavior can also be interpreted as the child not being afraid to say no to peer pressure, or as having strong leadership qualities in character. It is our job as parents, knowing our children well, to channel this powerful energy in the proper way, by setting certain limits and trying to keep our channel open with them.

It will be difficult and tiring, but worth it. Look at the situation this way: we want our children to grow up and become self-reliant and independent from adults. The rebelliousness and confrontation you see in behavior can also be interpreted as the child not being afraid to say no to peer pressure, or as having strong leadership qualities in character. It is our job as parents, knowing our children well, to channel this powerful energy in the proper way, by setting certain limits and trying to keep our channel open with them.

It is a challenge to see the positive in our children's behavior when this behavior complicates our lives or differs from what we want. But looking at things more positively will become easier when you allow and accept that your child is unique and separate from you. You shouldn't force your child on their path, it's helpful to try to step back a bit and see them grow from a more positive mindset.

Useful exercise. If you tend to see the glass as half empty, what do you need to do to see the glass as half full? Here's my advice: Every time you find yourself focusing on your child's negative traits, write down three positive aspects of each of those "bad" traits or behaviors. Train yourself to look at things from a different perspective. If your child is overly sensitive, note the positive side of this - his sensitive nature. If he argues with you, think that the good thing about it is that he defends his position and thus asserts himself.

Train yourself to look at things from a different perspective. If your child is overly sensitive, note the positive side of this - his sensitive nature. If he argues with you, think that the good thing about it is that he defends his position and thus asserts himself.

The key is to note and record the positive aspects of your child's negative behavior, and then help him by properly directing him in the right direction. You can facilitate the transition from aggression to self-assertion by setting limits on his behavior, as well as defining its natural consequences (behavior, not his emotions). Then move on to addressing the problem directly by talking about how to rein yourself in and be more productive next time. You must understand that having a quality of assertiveness in a child's personality is a very useful tool for life, as long as he, of course, uses it in a healthy way. Your job is to guide the child and help him do it correctly.

Rule #3: Visualize yourself in your child's shoes.

Look at any unsettling behavior and ask yourself what you need to understand about it? To do this, you will need to consider that your child's brain is still developing, as well as put yourself in your daughter's or son's shoes for a moment. Then you can learn this behavior in a less anxious state.

Let's say your son is in high school and wants to buy the running shoes that almost every kid in his class wears. When you answer “no”, he immediately gives an emotional reaction. You, in turn, react no less violently and shout: “Just because everyone has them, this does not mean that you should have them too!” At the same time, you think to yourself: “What happened to the values that we taught him? What's wrong with him? How did he become so selfish, demanding and rude?

Now stop for a moment and really imagine yourself in the place of the child. What do you now see and understand from what you did not see when you were in your place? Perhaps you can more clearly understand that it’s not about sneakers at all, but about his need to join the team (or not stand out from it), to be part of it. His development at this age stage of life dictates to him an urgent need to look and act like his peers.

His development at this age stage of life dictates to him an urgent need to look and act like his peers.

Have you ever tried not to worry about what others think of you? How did you do it? Now try being a teenager or a ten year old and do it again. Almost impossible, right? Don't get me wrong, a child's behavior doesn't mean you should give up and go buy him running shoes; it says that the child needs your sympathy and location so that you are on his side. Therefore, when you see his outbursts of anger, transform them into a thoughtful understanding of the child, and not experience or irritation about this.

Don't take everything personally. In addition to the fact that in this way you will get the opportunity to empathize with him and show calmness before you begin to discuss with the child the necessary restrictions on his behavior, you will also understand that some negativity of your baby is quite normal and is within the age limits. It will also help not to get personal, but to see the picture a little more clearly. Bottom line: You may not like the behavior, but at least you can see what the purpose of it was and won't take it personally.

Bottom line: You may not like the behavior, but at least you can see what the purpose of it was and won't take it personally.

Rule #4 Ask yourself "Is this just bad behavior or a reaction to something else?"

Sometimes we just don't notice the true purpose of our child's behavior and immediately classify it as negative. But once we begin to understand its motivation, it doesn't look so bad anymore. For example, suppose the parents of a child have been angry at each other for a long time. The child feels their tension and reacts in his own way. Having become the "emotional sponge" in the family, he begins to unconsciously notice that as soon as he does something bad (or even gets sick), his parents stop quarreling. Why is this happening? They get the opportunity to focus on the negative behavior of the child and distract from their own problems - such employment allows them to calm down a bit, leaving mutual recriminations and misunderstandings for a while. As a result, the child grows up with the knowledge of a concrete and effective way to keep his parents' relationship harmonious - to have some problems himself. It should be emphasized that this happens unconsciously.

As a result, the child grows up with the knowledge of a concrete and effective way to keep his parents' relationship harmonious - to have some problems himself. It should be emphasized that this happens unconsciously.

Therefore, take a step back and try to analyze whether your child's behavior is the implementation of a "script" for a "family merger". Is his behavior a reflection of the fact that family members have stopped hearing each other? Does it help others avoid focusing on themselves, personal problems, or their misbehaving? If yes, then this behavior is called “merging”. As James Lehman says, children watch us carefully throughout their lives and intuit certain things that their family needs to maintain stability and vitality. This means that they will exhibit (and sometimes unconsciously imitate) bad behavior and, if necessary, become the bright backbone of the family. Once you understand that a child's behavior serves a purpose, you can view it in a completely different light.

Rule #5 Differences are okay.

Of course, it is quite natural and understandable that we receive a lot of positive energy from people who like us and who are somewhat similar to us. Differences can make us feel uncomfortable, but keep in mind that differences are not synonymous with something negative. If your child acts, behaves, or thinks differently from you, instead of seeing it as a negative, just acknowledge those differences between you and move on.

It is very easy to perceive people, especially our children, from a position of concern. Our imagination in a stressful state is able to rush off into such impenetrable jungle, ... literally "run wild". But try to see your children as they really are, not as you fear they might become. When you learn to see them in a positive, sensible and realistic light, it will help them shine, blossom, and thrive.

Debbie Pinkus, Empowering Parents

Motivations for “bad behavior” of children.

Causes of persistent disobedience

Causes of persistent disobedience What are the causes of "bad behavior"? Let's think about what exactly do children want when they "misbehave"? Where does bad behavior come from?

The reasons for the persistent disobedience of the child, the motives of "bad behavior" should be sought in the depths of the child's psyche. It seems on the surface that he “simply does not obey”, “simply does not want to understand”, but in fact the reason is different. And, as a rule, it is emotional, not rational. Moreover, it is not realized by either the adult or the child himself. Hence the conclusion: such reasons need to be known.

There are five main causes of behavioral disorders in children that lead to the fact that the child becomes difficult and sometimes uncontrollable.

The first reason is the struggle for attention. If a child does not receive the attention that he needs so much for normal development and emotional well-being, then he finds his own way to get it: he does not obey. Disobedience is also an opportunity to attract attention to yourself. Parents now and then break away from their affairs, make comments ...

Disobedience is also an opportunity to attract attention to yourself. Parents now and then break away from their affairs, make comments ...

The second reason is the struggle for self-affirmation. This is a struggle against excessive parental authority and guardianship. The child declares war on the endless instructions, remarks and fears of adults. The famous demand of the child "I myself" persists throughout childhood, becoming especially aggravated in adolescents. The ability to have your own opinion, to make your own decision is an opportunity to gain your own experience, even if it is erroneous. If the parents too often make comments and give advice, and their criticism is too harsh, the fears are exaggerated, then the child "revolts".

The third reason is the desire for revenge. A child may retaliate when compared to older or younger siblings, or when parents give more attention to a younger child; humiliation of each other by family members; the injustice of parents and their unfulfilled promises; excessive manifestation of love of adults for each other, etc. Children are often offended by their parents, for example, if the mother separated from the father, if a new family member appeared in the house, or the child himself was excommunicated from the family (sent to his grandmother, to a camp, etc.). In the depths of his soul, the child experiences and even suffers, but on the surface all the same protests, disobedience.

Children are often offended by their parents, for example, if the mother separated from the father, if a new family member appeared in the house, or the child himself was excommunicated from the family (sent to his grandmother, to a camp, etc.). In the depths of his soul, the child experiences and even suffers, but on the surface all the same protests, disobedience.

The fourth reason is the loss of faith in one's own success. Reasons for not believing in one's own success can be educational failures, relationships in the classroom and with the teacher, low self-esteem. It may happen that a child is experiencing trouble in one area, and failures occur in a completely different area. For example, the boy did not have a relationship in the classroom, and the result was a neglected study; in another case, failure at school leads to defiant behavior at home. This "displacement of ill-being" is due to the child's low self-esteem. Having accumulated bitter experience, he loses self-confidence and comes to the conclusion: “There is nothing to try, nothing will work out anyway. ” This is in the soul, and by his behavior he shows: “I don’t care ...”, “Let me be bad ...”.

” This is in the soul, and by his behavior he shows: “I don’t care ...”, “Let me be bad ...”.

The fifth reason is attempts to enlist the support of friends (in many ways similar to the first). If a child does not receive the necessary attention in the family, then he finds his own way to get it: he finds attention and support from friends. The child disappears late into the street with his peers. Despite all the reprimands and exhortations of the parents, the situation is not improving.

Remember, any serious misbehavior is a cry for help. By his behavior, the child tells us: “I feel bad! Help!" The conclusion follows from this: a “difficult” child needs help, not criticism or punishment.

Naturally, children do all this unconsciously; as a rule, annoying adults with their bad behavior, they are not aware of what they are trying to achieve.

If you learn to determine the cause of a behavioral disorder, you can constructively build communication with your child, replace an unproductive way of communication with an effective one.