Borderline personality disorder family dynamics

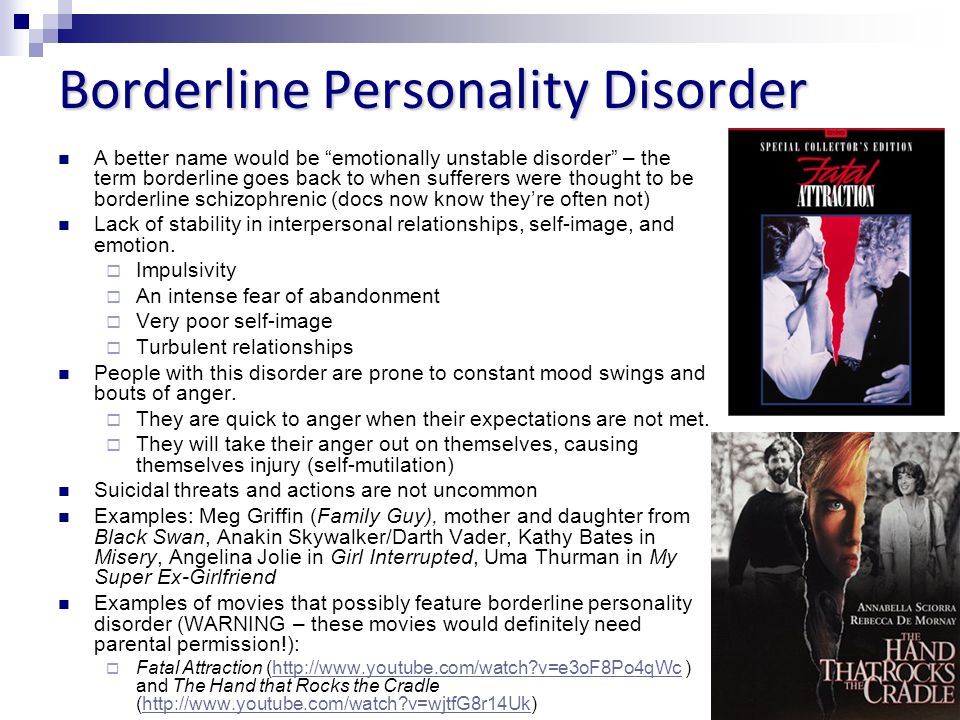

Borderline Personality Disorder

What causes BPD?

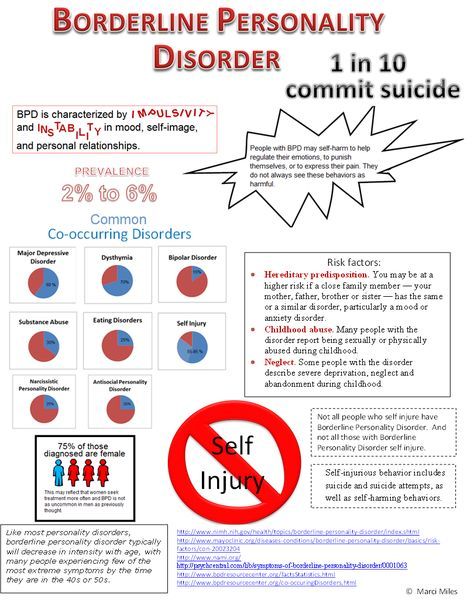

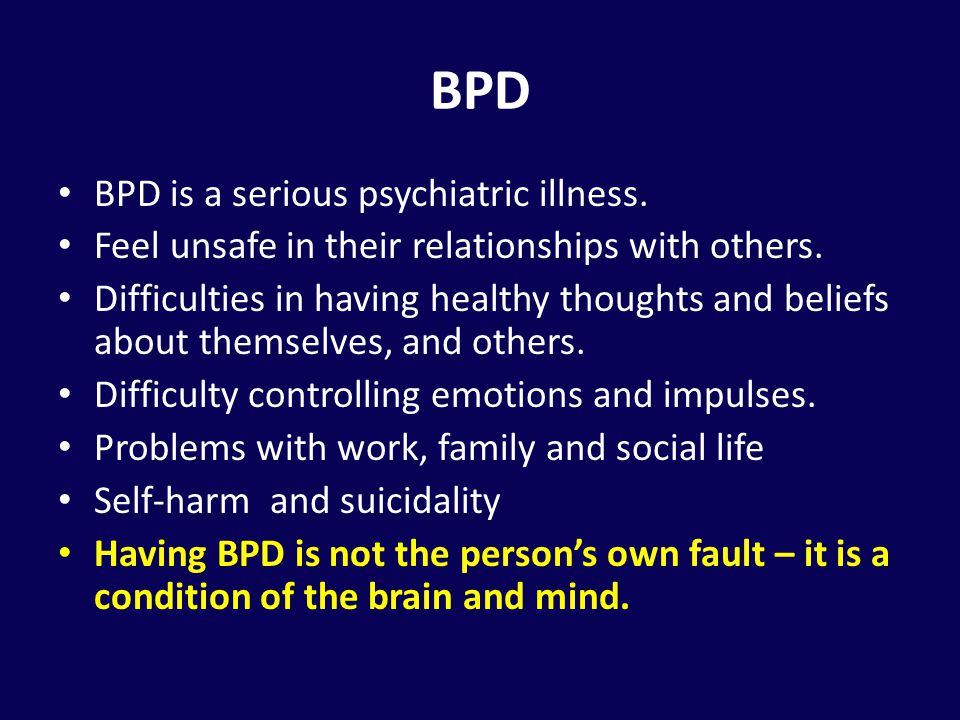

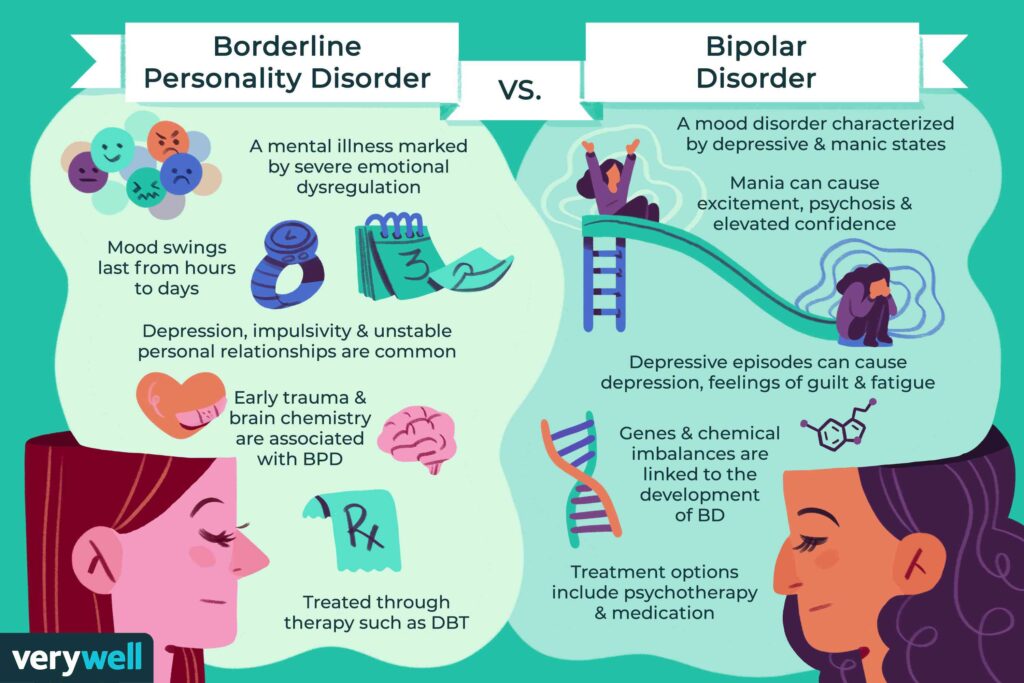

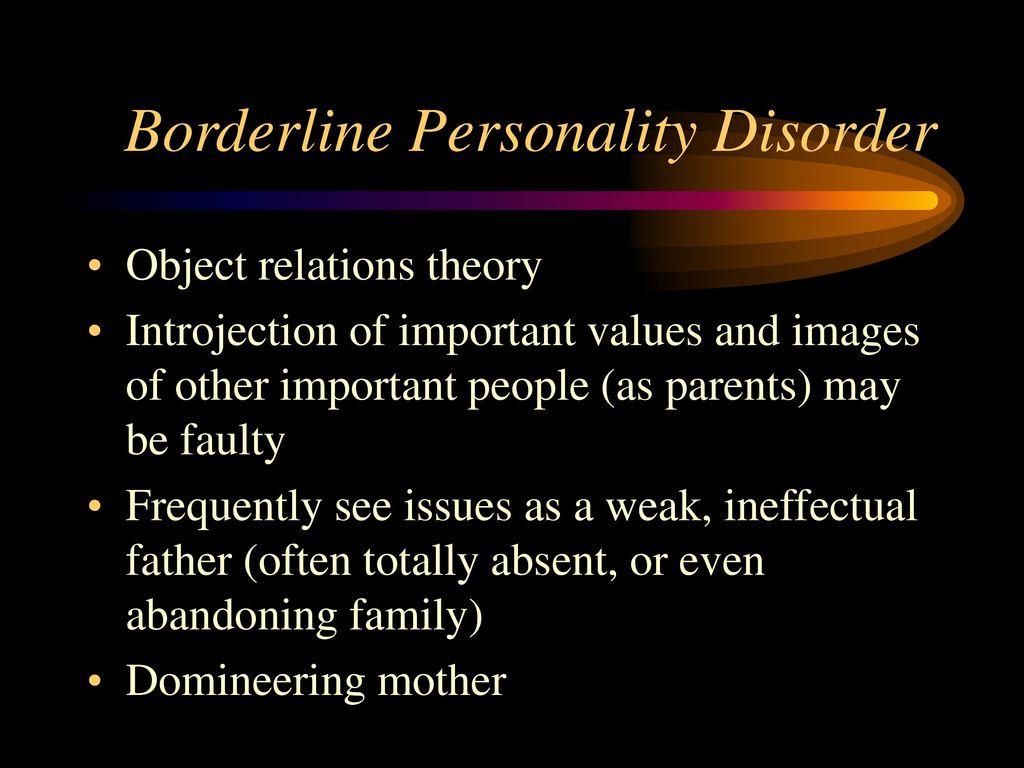

At one point, BPD was believed to be caused by faulty parenting, and many families felt unfairly blamed. Our current understanding is that BPD has a strong biological component, and that it results from a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Recent research suggests that individuals suffering from BPD have imbalances in the neurotransmitters that regulate emotion and impulse control. Serotonin is one neurotransmitter believed to play a significant role in BPD. When individuals suffer from this type of an imbalance, life stresses can easily overwhelm their coping abilities.

Although BPD may develop purely as a result of a biological "vulnerability," research indicates that many individuals with BPD do have a history of traumatic early childhood experiences. About 50 - 70% of individuals with BPD report a history of childhood sexual abuse. Many also report histories of verbal or physical abuse. Often there is a pattern of inconsistent parenting and poorly met needs that may stem from parental addictions or mental illness.

A history of early loss or traumatic abandonment is also common, possibly due to death of a parent or parental separation.

Because of their knowledge and expertise in family relationships, MFTs can help reduce the impact of BPD symptoms on family relationships, and improve overall marital and family functioning.

What is the effect of BPD on family members?

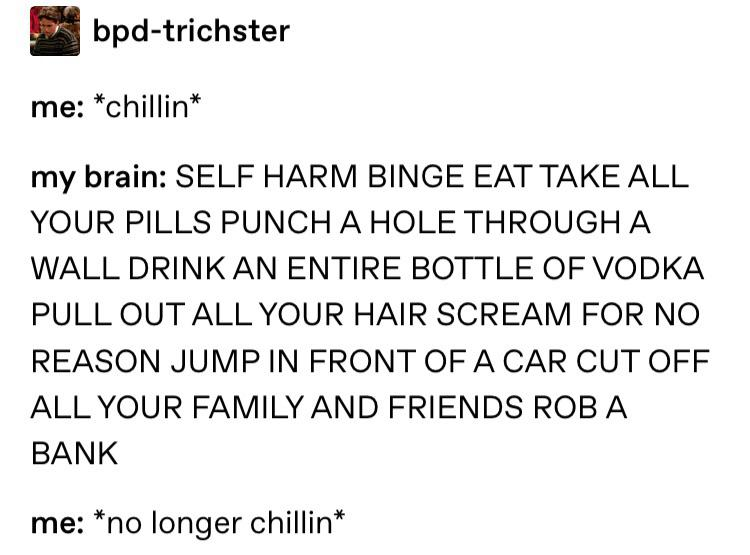

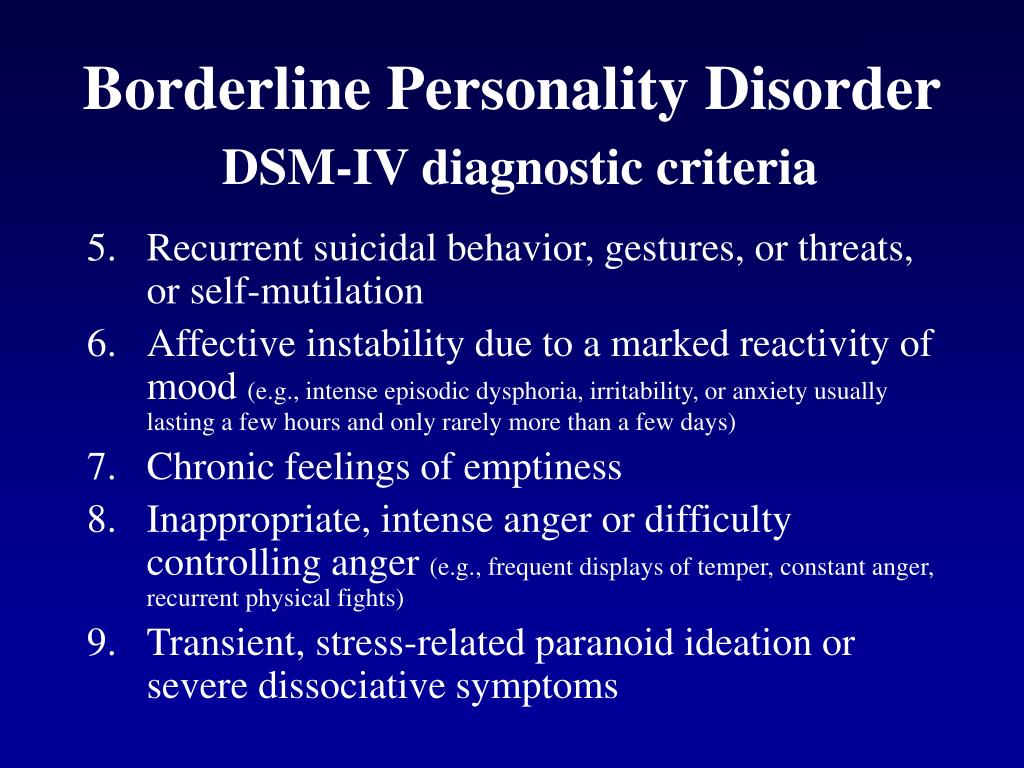

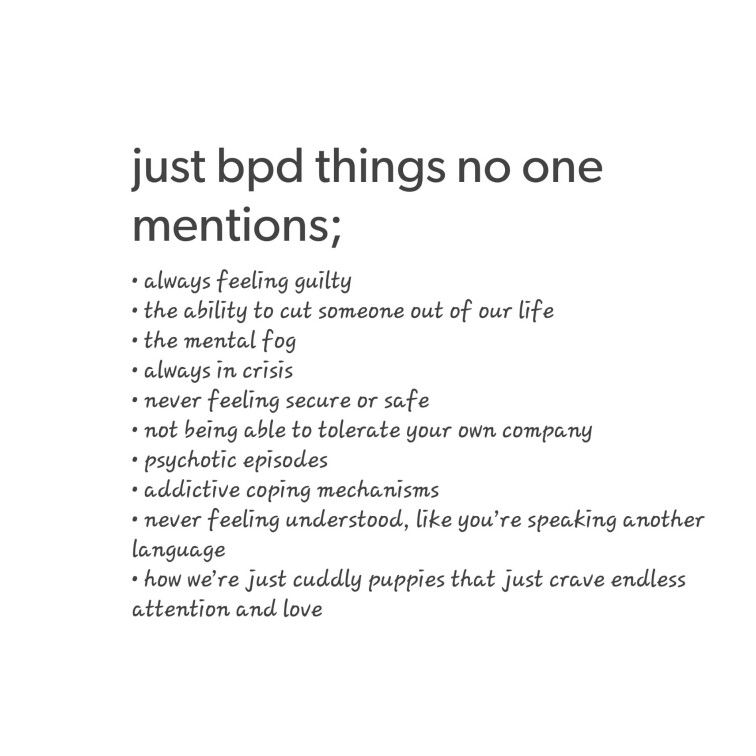

Family members often feel mystified and exhausted by their relative's illness. The intense mood swings and anger outbursts can be frightening and disruptive. Impulsive acting out in areas such as spending, substance abuse, or sex can be a major source of marital conflict. Relatives may be overwhelmed with worry regarding their loved one's safety following repeated suicide attempts or acts of self-mutilation. At times, partners and family members may feel manipulated by these suicidal or self-destructive behaviors, and feel torn between reaching out to their loved one, and setting personal limits and boundaries. It is not unusual for relatives and spouses of BPD individuals to feel depressed themselves, and to struggle with feelings of guilt, shame and helplessness.

What help is available?

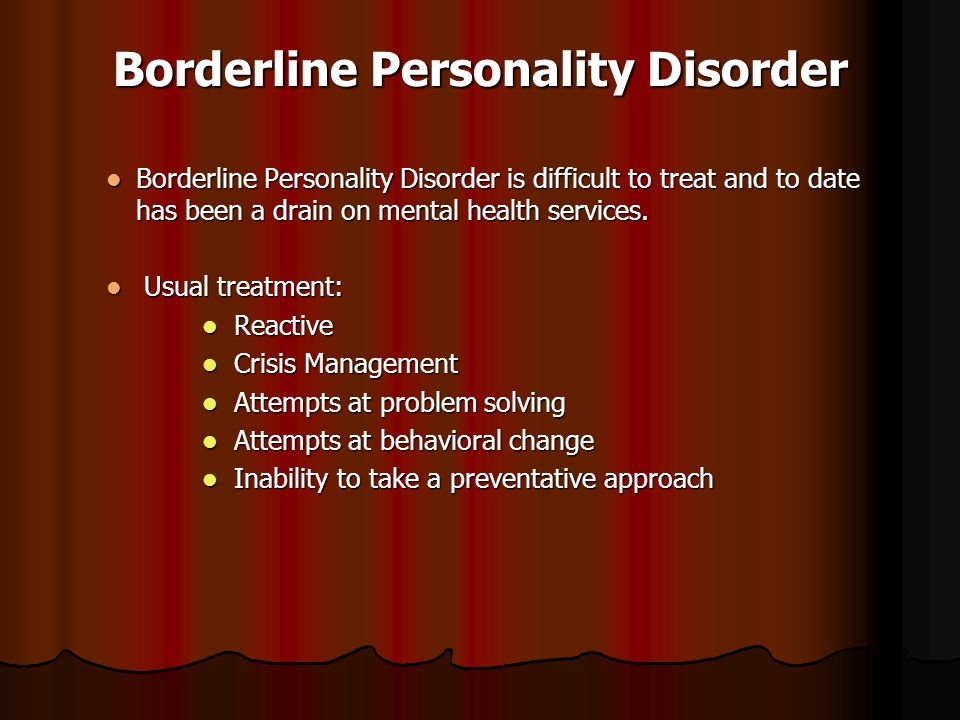

A number of effective treatment options are emerging to help BPD individuals and their families. Some of these options include:

Medication: Medications can be helpful in reducing symptoms of depression, anxiety, irritability and paranoid thoughts. Medications may also help improve emotional and impulse control, thereby reducing stress in marital or family relationships and making it easier to develop new interpersonal or stress management skills in psychotherapy.

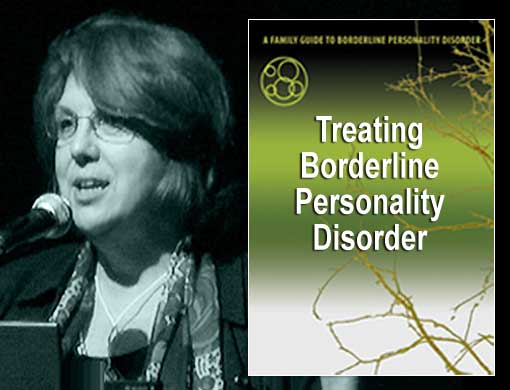

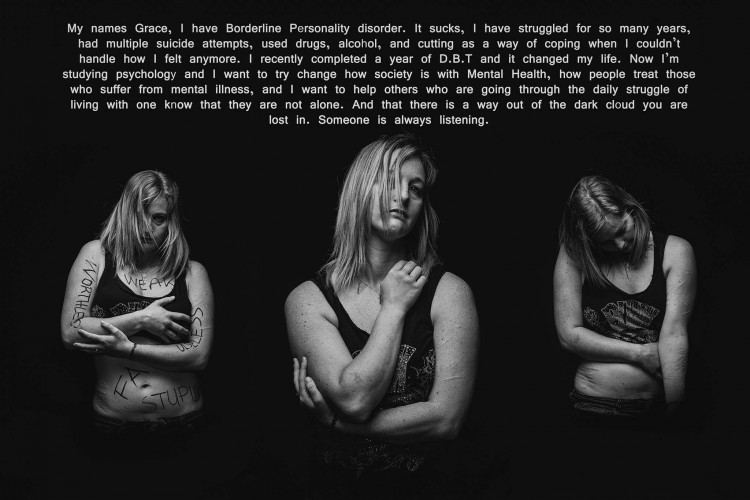

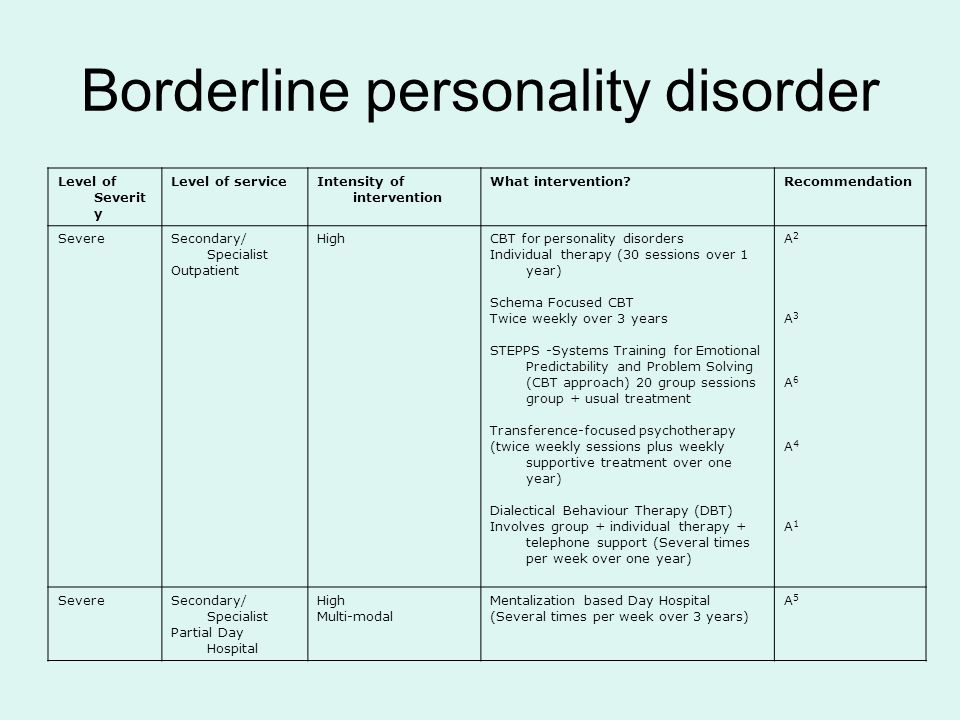

Individual Psychotherapy: Often, psychotherapy is required to achieve lasting personality change. Short-term or brief therapy may be helpful in stabilizing immediate crises. Psychodynamic therapy helps make connections between early traumatic experiences and ways that learned behavior patterns are repeated in current relationships. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, especially a version of it known as Dialectical Behavior Therapy(DBT), has proven helpful in altering negative patterns of thinking, and in learning new behaviors and coping strategies.

Group Therapy: Group Therapy is often helpful in learning and practicing new interpersonal skills and increasing awareness of problematic interpersonal traits and behaviors.

Brief Hospitalization: Hospitalization may be necessary to ensure safety during suicidal crises or episodes of self-injury. Some hospitals offer brief intensive treatment programs for BPD.

Marital or Family Therapy: Marital Therapy can be helpful in stabilizing the marital relationship and in reducing marital conflict and stress that can worsen BPD symptoms. Family Therapy or Family Psychoeducation can help educate family members regarding BPD, improve family communication and problem solving, and provide support to family members in dealing with their loved one's illness.

Marriage and Family Therapists (MFTs) can be excellent treatment providers for individuals and families who are struggling with the effects of BPD. MFTs are trained to recognize and treat BPD using many of the treatments described above. Because of their knowledge and expertise in family relationships, MFTs can help reduce the impact of BPD symptoms on family relationships, and improve overall marital and family functioning.

Because of their knowledge and expertise in family relationships, MFTs can help reduce the impact of BPD symptoms on family relationships, and improve overall marital and family functioning.

Resources

-

Borderline Personality Disorder Central: A non-profit organization offering Internet resources and support for family members.

-

National Educational Alliance for Borderline Personality Disorder (NEA-BPD): A non-profit organization focused on families that aims to provide education regarding BPD.

Phone: (914)835-9011 -

BPD Family: A website focused on family support and including online support forums

Edited by Malcolm MacFarlane, MA

Last updated October 2017

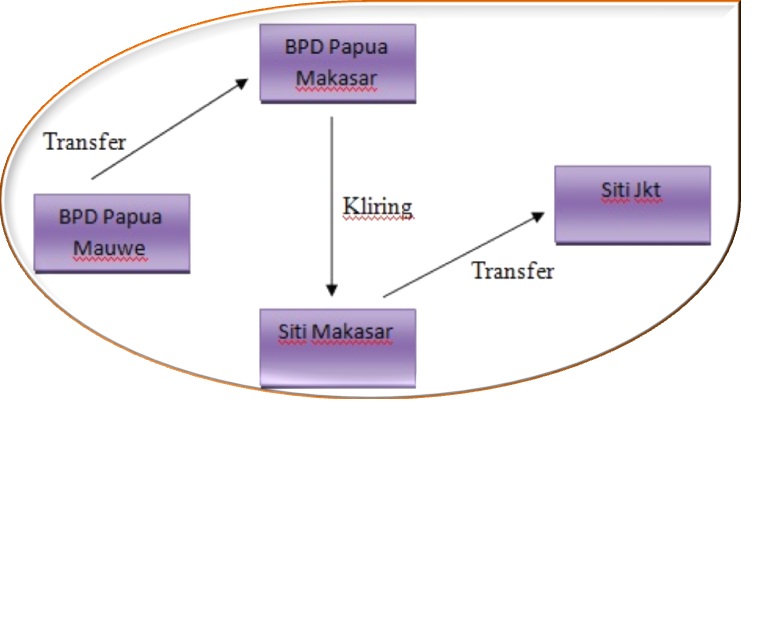

The Family Dynamics of Patients With Borderline Personality

In my last post, I discussed how children act out certain roles in their family of origin to try to stabilize parents who are emotionally unstable. Doing so also has the effect of maintaining dysfunctional relationship patterns so that the family operates in predictable ways (family homeostasis).

Doing so also has the effect of maintaining dysfunctional relationship patterns so that the family operates in predictable ways (family homeostasis).

In today's post, I will look at the role that is played by the patient with borderline personality disorder (BPD), which I call the Spoiler. I will look at the dysfunctional family dynamics that I believe help to create the disorder.

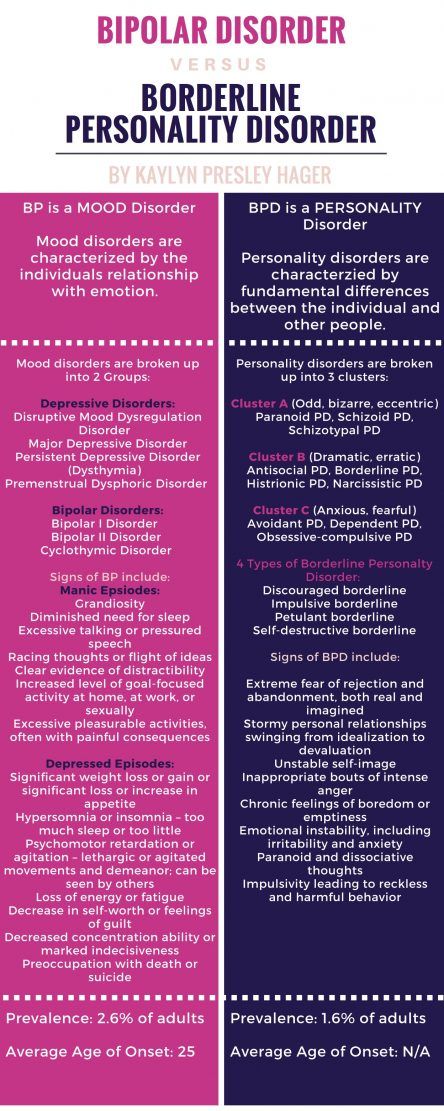

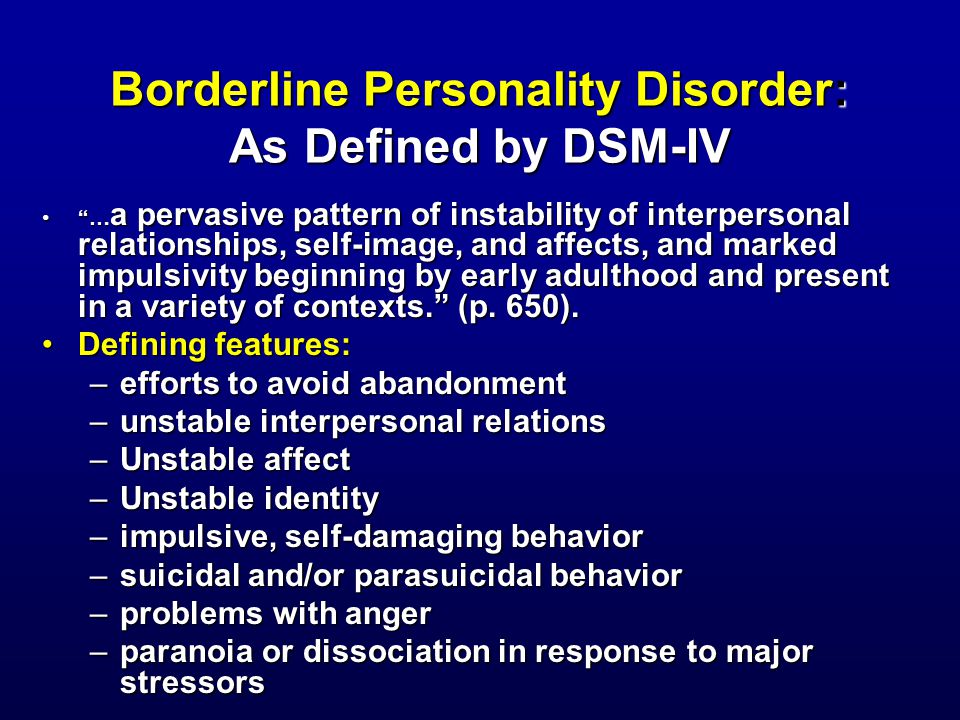

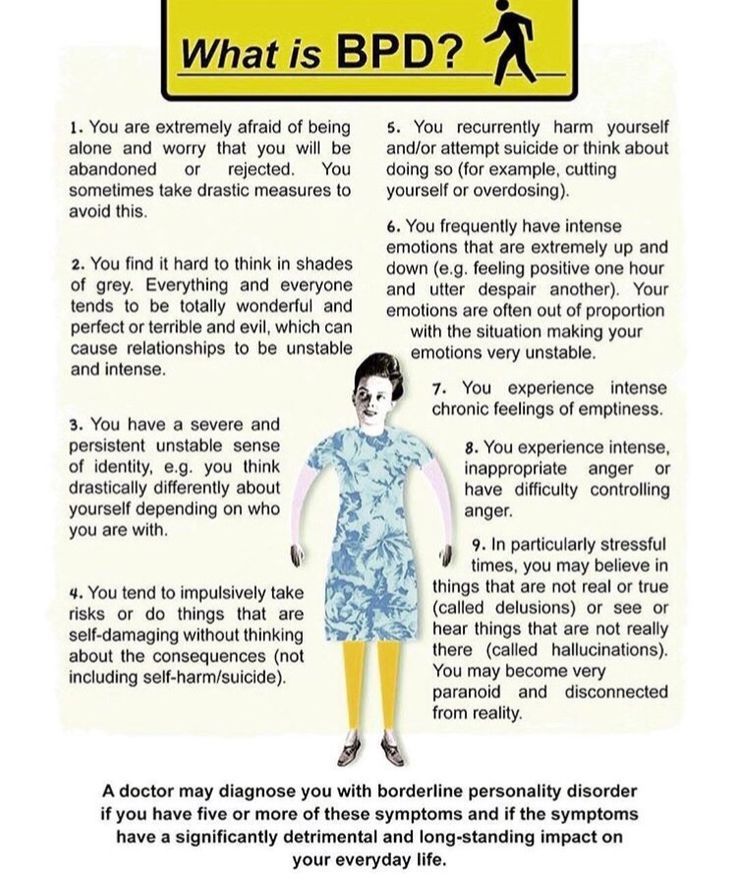

For readers who are not familiar with the disorder, BPD is sort of the "jack of all trades" of personality dysfunction. People who have the diagnosis show gross disturbances in their ability to control their emotions, in their extremely chaotic interpersonal relationships, in their impulse control, and in their attempts to understand who or what they want to be in life (identity confusion).

These are the people who are not psychotic but who seem to show very poor judgment in interpersonal relationships, and who often seem to misinterpret in a negative way the most innocent-sounding comments made to them by others. They often cut, burn, or in other ways injure themselves. They make suicide threats and attempts and have anger control problems. They do not trust others easily, and they often "space out" or dissociate when under stress.

They often cut, burn, or in other ways injure themselves. They make suicide threats and attempts and have anger control problems. They do not trust others easily, and they often "space out" or dissociate when under stress.

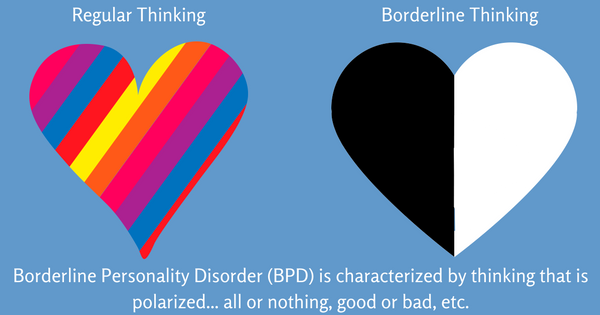

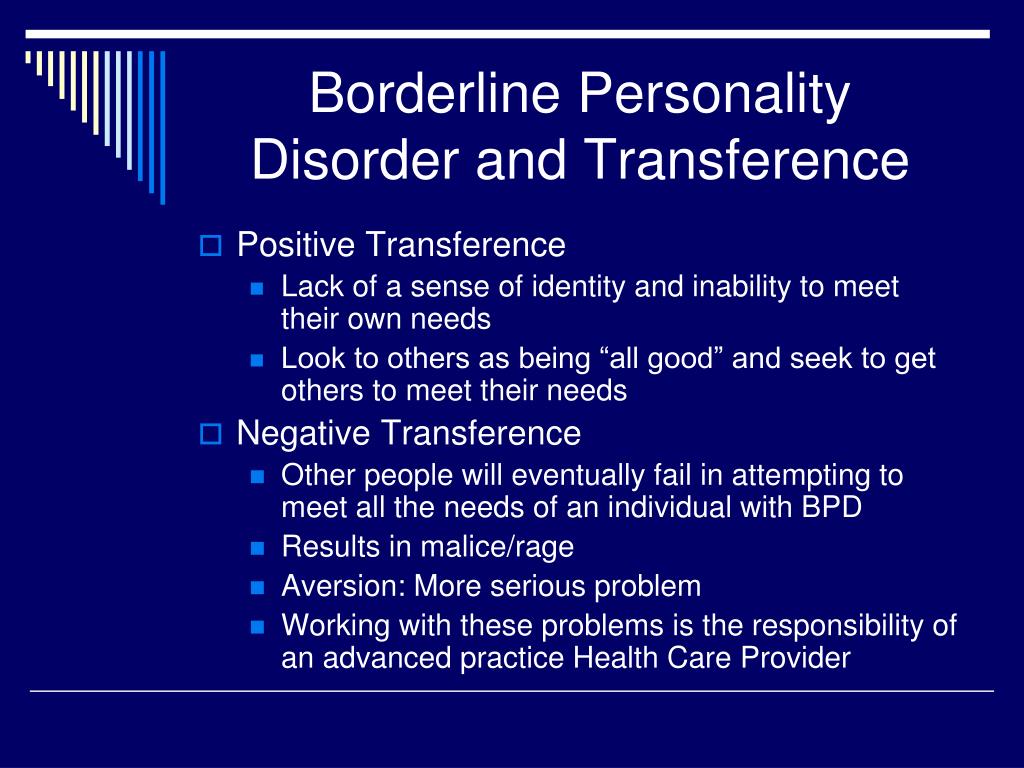

They engage in behavior referred to by therapists as splitting: Everyone else is treated either like a god or a complete pile of manure, with nothing in between. Interestingly, patients with BPD are often described by therapists as being superb manipulators. One must wonder how anyone who cannot simultaneously evaluate another person's strengths and weaknesses could possibly be a good manipulator. Simple answer: They could not. While the tendency of these individuals to "split" others into all good or all bad does derive from the bewildering contradictory behavior of the patient's parents or primary caretakers, usually it is just an act.

Their behavior is often so extreme that is natural to start to think that they must have some sort of brain disease. While genetics may predispose some individuals to be more prone to develop these characteristics than others, I am not among the psychiatrists who think BPD is a disease rather than dysfunctional personality traits that tend to co-occur in some children from some disturbed families.

While genetics may predispose some individuals to be more prone to develop these characteristics than others, I am not among the psychiatrists who think BPD is a disease rather than dysfunctional personality traits that tend to co-occur in some children from some disturbed families.

Why do I say this? Mainly for two reasons. First, once I figured out how best to respond to patients with BPD in psychotherapy; and many of the therapists who see a lot of these patients independently stumbled upon the same techniques that I use. I noticed that patients with BPD could turn most of their symptoms off and on like a faucet, and at a moment's notice. [Clarification requested by many commenters: by "symptoms" I am speaking of behavioral symptoms, not how they feel inside]. Patients with what I believe to have significant brain disorders such as those with schizophrenia or melancholic depression are not able to do this. Second, when I finally get the real story of their lives, these patients nearly always seem to come from families that have severe family pathology.

According to a large number of studies, child abuse and/or neglect is the single most common biological, psychological, or social risk factors seen in individuals who develop the disorder. Of course, not every abused or neglected child develops BPD, and many patients who have the disorder were never sexually or physically abused.

On my Family Dysfunction and Mental Health blog, I discuss the movie Thirteen, which is almost an instruction manual on how to create patients with BPD without abusing them. It is not abuse per se, but the conflicting double messages given by the parents that are most likely to create borderline behavior in offspring.

The basic problem in the "borderline" family—to make a complicated and highly variable story tremendously oversimplified—is that the parents in such families see the role of being parents as the end all and be all of human existence. Yet, at the same time, deep down they hate being parents and/or see their children as an impediment to their personal fulfillment.

It's all well and good to try to understand the behavior of the individual with BPD in terms of a response to parental problems, but that just kicks the question of an explanation for the disorder back a generation. In many families, the parents' conflicting emotions are focused on one or more of their children, so that their other children may escape relatively unscathed.

The conflict over the role of "parent" leads to a pattern in which the parents go back and forth between hostile over-involvement with or without abuse, and hostile under-involvement with or without neglect.

The double message inherent in this pattern, in turn, leads the children to perceive a message from their parents that roughly translates into, "I need you, but I hate you." The over-involvement or under-involvement polarity may predominate in a particular family, but if one waits long enough, the other extreme rears its ugly head.

To stabilize the family homeostasis, the child who becomes the focus of the parents' ambivalence has to figure out the answer to the following question: How can he or she remain central in the parents' lives (even if contact seems limited) and still provide them with an easy justification and outlet for their anger so they do not have to feel guilty about it?

The role of the Spoiler is the perfect solution, and it is absolutely ingenious.

Spoiling behavior was first described by psychoanalyst Melanie Klein, who thought it had something to do with a child's primitive envy of the mother's breast. I just could not get my head around this almost psychotic-sounding explanation, but I had to admit that she was describing a very real pattern of adult behavior.

The spoiler child refuses to grow up, remains dependent in some way on the parent or a parent surrogate, and ruins and/or denigrates everything the parents try to do for them. A female child might start to lose or mistreat valuable designer clothes, and then demand both replacements of the expensive gifts and more of her mother's time.

Nothing the parent does or says is ever good enough. The "child," and this continues well into adulthood, will figuratively piss over everything the parent does for them. The parents' motives are consistently misinterpreted and they are constantly accused of being selfish, overly demanding, stupid, or downright evil. They are treated with utter contempt.

They are treated with utter contempt.

This treatment of the parents is a form of invalidation.

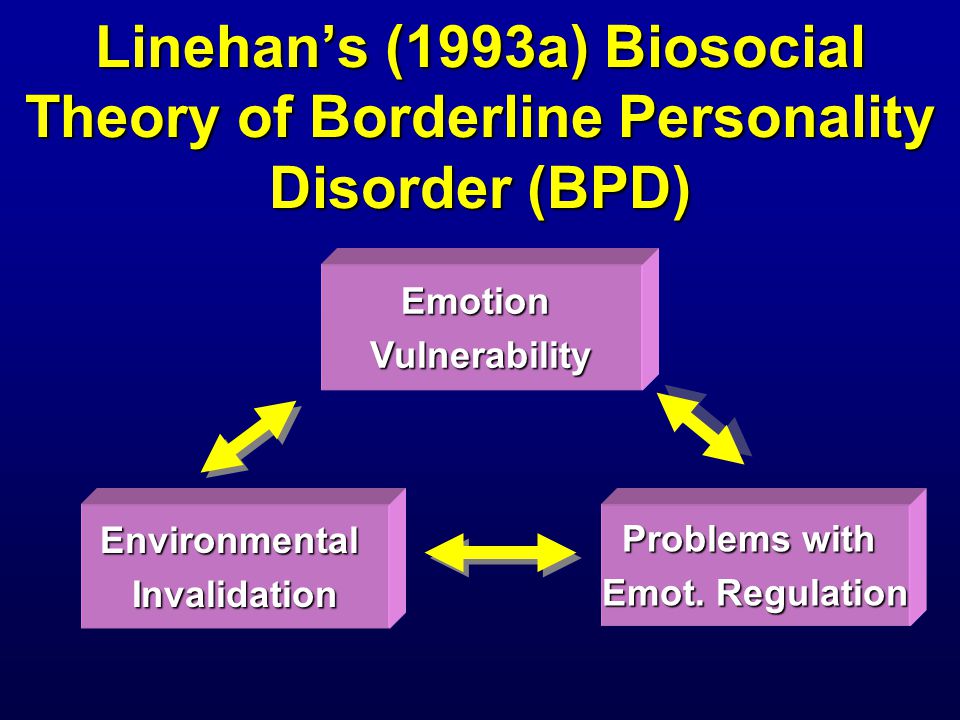

Marsha Linehan, the developer of one of the most prominent psychotherapy treatment models for BPD, theorizes that an "invalidating environment" is, along with a genetic tendency to be over-emotional, one of the two major causes of BPD. She does not specify which environment she is talking about, but it is obviously the family in which the person grew up.

Invalidating someone else is not merely disagreeing with something that the other person says. It is a process in which individuals communicate to another that the opinions and emotions of the target are invalid, irrational, selfish, uncaring, stupid, most likely insane, and wrong, wrong, wrong. Invalidaters let it be known directly or indirectly that their target's views and feelings do not count for anything to anybody at any time or in any way. In some families, the invalidation becomes extreme, leading to physical abuse and even murder. However, invalidation can also be accomplished by verbal manipulations that invalidate in ways both subtle and confusing.

However, invalidation can also be accomplished by verbal manipulations that invalidate in ways both subtle and confusing.

In families that produce BPD offspring, invalidation of the child by the parents is omnipresent. After a while, the child starts doing to the parents exactly what the parents have been doing to the child. They start to give at least as good as they get.

Spoilers never become independent of their parents because they never really function as competent adults. This allows the parents to remain obsessed with the child, as seems to be their fervent desire. At the same time, the outrageous and scandalous behavior of the child gives the parents a much-needed excuse to vent their often unacknowledged hostility toward their offspring.

The parents often still feel guilty over their poor performance in the parenting role, which again leads them to become unstable. In response, the child will start to try to "regulate" their emotions. If the parents get too angry, the child makes them feel guilty. If they start to feel too guilty, the child makes them angry.

If they start to feel too guilty, the child makes them angry.

The spoiler role is difficult to maintain, so the child needs to continually practice it with other people. The usual candidates for them to practice on are lovers, spouses, and of course therapists. No one else will continue to put up with them.

It is also important to realize that an adult who exhibits BPD behavior volunteers to perform the spoiler role, so their behavior cannot be blamed entirely on the parents. As I stated earlier, past a certain point, patients with BPD give as good as they get.

FGBNU NTsPZ. ‹‹Borderline mental disorders››

The pathocharacterological properties that unite this group of personality disorders are impulsiveness with a pronounced tendency to act without regard for consequences and a lack of self-control, combined with mood instability and violent affective outbursts that occur at the slightest provocation. There are two types of this variant of personality disorders - impulsive and borderline.

Impulse type corresponds to excitable psychopathy. Psychopathy of this type, as E. Kraepelin points out, is characterized by unusually strong emotional excitability. Its initial manifestations are found even in preschool age. Children often scream and get angry. Any restrictions, prohibitions and punishments cause them violent reactions of protest with malice and aggression. In the lower grades, these are “difficult” children with excessive mobility, unbridled pranks, capriciousness and touchiness. Along with irascibility and irritability, they are characterized by cruelty and gloom. They are vindictive and quarrelsome. Early revealed tendency to a gloomy mood is combined with periodic short-term (2-3 days) dysphoria. In communicating with their peers, they claim leadership, try to command, establish their own rules, which often causes conflicts. Most of the time they are not interested in learning. They are not always kept at school or vocational schools, and once they start working, they soon leave.

The formed psychopathy of the excitable type is accompanied by bouts of anger, rage, affective discharges, sometimes with an affectively narrowed consciousness and a sharp motor excitation. In temper (especially easily occurring during alcoholic excesses), excitable individuals are able to commit rash, sometimes dangerous actions. In life, these are active, but incapable of long-term purposeful activity, uncompromising, tough people, with vindictiveness, with viscosity of affective reactions. Among them, there are often people with disinhibition of drives, prone to perversions and sexual excesses.

The subsequent dynamics of excitable psychopathy, as shown by the works of V. A. Guryeva and V. Ya. Gindikin (1980), is heterogeneous. With a favorable course, psychopathic manifestations are stabilized and even relatively fully compensated, which is largely facilitated by the positive influences of the environment and the necessary educational measures. Behavioral disturbances in such cases by the age of 30-40 are significantly smoothed out, and emotional excitability gradually decreases. However, a different dynamic is possible with a gradual increase in psychopathic features. Disorderly life, inability to restrain impulses, joining alcoholism, intolerance to any restrictions, and finally, a tendency to violent affective reactions serve in such cases as the causes of a long-term violation of social adaptation. In the most severe cases, acts of aggression and violence committed during affective outbursts lead to a collision with the law.

However, a different dynamic is possible with a gradual increase in psychopathic features. Disorderly life, inability to restrain impulses, joining alcoholism, intolerance to any restrictions, and finally, a tendency to violent affective reactions serve in such cases as the causes of a long-term violation of social adaptation. In the most severe cases, acts of aggression and violence committed during affective outbursts lead to a collision with the law.

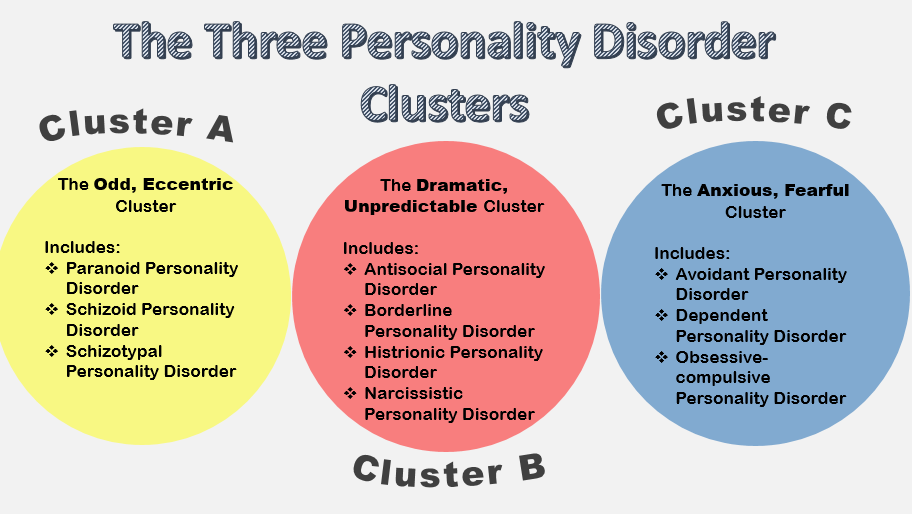

The borderline type has no direct analogues in the domestic systematics of psychopathy, although in some personal parameters it is comparable to the unstable type of psychopathy. Borderline personality disorder overlaps with other personality disorders - primarily hysterical, narcissistic, dissocial [Harrison G., Pope U. G. et al., 1983], needs to be differentiated from schizotypal disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety-phobic and affective disorders (see. description of the dynamics of borderline personality disorder).

The borderline personality is distinguished by increased impressionability, affective lability, vividness of imagination, mobility of cognitive processes, constant "inclusion" in events related to the sphere of current interests or hobbies, extreme sensitivity to obstacles on the way to self-realization, functioning at the maximum of possibilities. Difficulties in the sphere of interpersonal relations, especially the situation of frustration, are also perceived sharply. The reactions of such subjects even to trivial events can acquire an exaggerated, demonstrative character. As emphasized by M. Smiedeberg (1959), they too often experience those feelings that are usually found only in a situation of stress.

The initial pathocharacterological manifestations (emotional lability, suggestibility, a tendency to fantasies, a quick change in hobbies, instability in relationships with peers) are found already in adolescence. These children ignore school rules and parental prohibitions. Despite good intellectual abilities, they do not do well, because they do not prepare for classes, get distracted in class, and reject any attempts to regulate their daily routine.

Despite good intellectual abilities, they do not do well, because they do not prepare for classes, get distracted in class, and reject any attempts to regulate their daily routine.

The distinctive properties of borderline personalities include the lability of self-esteem, the variability of ideas about both the surrounding reality and one's own personality - a violation of self-identification, the inconstancy of life attitudes, goals and plans, the inability to resist the opinions of others. Accordingly, they are suggestible, susceptible to external influences, easily adopt forms of behavior not approved by society, indulge in drunkenness, take stimulants, drugs, they can even acquire criminal experience, commit an offense (most often we are talking about petty fraud).

Borderline psychopaths easily fall into dependence on other, sometimes unfamiliar people. Approaching, they quickly form a complex structure of relationships with excessive subordination, hatred or adoration, the formation of overvalued attachments; the latter serve as a source of conflict and suffering associated with the fear of separation and impending loneliness, and may be accompanied by suicidal blackmail.

The life path of borderline individuals seems to be very uneven, replete with unexpected turns in the social route, family status. Periods of relative calm are replaced by all sorts of collisions; easy transitions from one extreme to another - this is a sudden love that overcomes all obstacles, ending in an equally sudden break; and passion for a new business with objectively high professional success, and a sudden abrupt change of job after a minor industrial conflict; it is also wanderlust leading to relocation and progression. However, despite all the upheavals of life, these people do not lose their sanity when in trouble, they are not as helpless as they might seem, they can find an acceptable way out of the situation at the right time. The "zigzags" of behavior inherent in most of them do not prevent a fairly good adaptation. Easily adapting to new circumstances, they retain their ability to work, find work, arrange a new life [McGlashan T. N., 1986].

Within the framework of the dynamics of borderline personality disorder, phases that are erased, not accompanied by manifest affective symptoms, are observed, unfolding mainly in the autopsychic sphere. Long periods of recovery with increased activity, a sense of optimal intellectual functioning, a heightened perception of the surrounding life can be replaced (most often due to psychogenic or somatic - pregnancy, childbirth, intercurrent illness - provocation) dysthymic phases. In these cases, complaints about a decrease in mental capabilities, a feeling of incompleteness of feelings and cognitive functions, and in more severe cases, the phenomena of mental anesthesia are brought to the fore in the clinical picture in these cases.

Long periods of recovery with increased activity, a sense of optimal intellectual functioning, a heightened perception of the surrounding life can be replaced (most often due to psychogenic or somatic - pregnancy, childbirth, intercurrent illness - provocation) dysthymic phases. In these cases, complaints about a decrease in mental capabilities, a feeling of incompleteness of feelings and cognitive functions, and in more severe cases, the phenomena of mental anesthesia are brought to the fore in the clinical picture in these cases.

Among other pathological reactions, judging by the descriptions of J. G. Gunderson, M. Singer (1965), Ch. Perry, G. Kjerman (1975), J. Modestine (1983), with borderline disorders, psychogenically provoked transient outbursts are most common with a motley clinical picture, including, along with affective, dissociative hysterical, poorly systematized delusional disorders. Although these psychopathological manifestations (“mini-psychoses”) [Pfeifter R. , 1974; Rohde-Dacher Ch., 1982], as a rule, are rapidly reduced, their nosological qualification is fraught with difficulties. First of all, it is necessary to exclude schizophrenia, affective and schizoaffective psychoses.

, 1974; Rohde-Dacher Ch., 1982], as a rule, are rapidly reduced, their nosological qualification is fraught with difficulties. First of all, it is necessary to exclude schizophrenia, affective and schizoaffective psychoses.

The criteria that reduce the validity of the diagnosis of an endogenous disease are such features of "minipsychoses" as psychogenic provocation, transient nature, complete reversibility in the absence of a tendency to systematization and chronification.

FGBNU NTsPZ. ‹‹Borderline mental disorders››

Psychopathic personalities are distinguished not only by an abnormal temperament, but also by a much greater vulnerability compared to healthy people, increased sensitivity to the influence of both internal - biological (age crises, menstrual cycle, pregnancy, childbirth, etc.), and external stressful and somatogenic factors. As P. B. Gannushkin points out (1933), the ability of psychopaths to lose mental balance and leads to the fact that "psychopathic soil", as a rule, causes a much more vivid and varied dynamics than normal.

The foundations of the doctrine of the dynamics of psychopathy in domestic psychiatry were laid by P. B. Gannushkin (1933). Rejecting the view that existed at that time of psychopathy as frozen anomalies that do not change during life, he resolutely opposed static characterology. “Although we oppose,” wrote P. B. Gannushkin, “psychopathy as stationary states to psychosis processes, this statics is very conditional: it comes down mainly to the preservation of a certain unity of the personality, against the background of which a purely dynamic unfolds.”

In some cases, only the dynamics of pathocharacterological properties, due to the influence of certain pathogenic factors for a given personality, “shows” the psychopathic properties of the personality, and they reach the degree of a clinically delineated anomaly. This is more often observed with shallow personality anomalies that remain under normal conditions at the level of character accentuations (according to A. E. Lichko, 1983), accentuated personalities (according to K. Leonhard, 1968, 1981).

Lichko, 1983), accentuated personalities (according to K. Leonhard, 1968, 1981).

The development of psychopathy is more determined by external causes than by relatively clearly biologically determined patterns that govern the course of endogenous psychoses. An extremely wide range of possible external influences, in turn, corresponds to the variety of psychopathic manifestations throughout the life of abnormal personalities.

The dynamics of psychopathy may change due to the addition of alcoholism and drug abuse. Substance abuse in such cases not only alters the picture of psychopathy, but also acquire a more malignant course. Substance abuse in psychopathic personalities is characterized by compulsive craving, more severe withdrawal symptoms, early onset of psychotic disorders and signs of an organic psychosyndrome. A tendency to chronic alcoholism and drug addiction is more often observed with borderline personality disorder, but it is also possible with other types of personality anomalies (excitable, hysterical). 80; Lichko A. E., 1983]. The addition of substance abuse leads to an increase in affective and gross hysterical reactions with demonstrative suicidal attempts, and an increase in the disharmony of the personality as a whole. At the same time, facultative or previously hidden psychopathic features are usually revealed, irritability, malice, anger, impulse disorders are intensified, and often antisocial forms of behavior appear for the first time.

80; Lichko A. E., 1983]. The addition of substance abuse leads to an increase in affective and gross hysterical reactions with demonstrative suicidal attempts, and an increase in the disharmony of the personality as a whole. At the same time, facultative or previously hidden psychopathic features are usually revealed, irritability, malice, anger, impulse disorders are intensified, and often antisocial forms of behavior appear for the first time.

The clinical picture of decompensation (features of clinical manifestations, severity and duration), as well as trends towards the further development of psychopathy after decompensation, are determined not only by external influences, but also by the severity and typological differences of psychopathic changes. With different types of psychopathy, conflicts and reactions arise for different reasons, have different content. So, schizoid, avoidant and dependent personalities are better adapted in family conditions, but are easily decompensated due to work conflicts. Impulsive (excitable), on the contrary, are primarily surrounded by family troubles. They are intolerant in the family and present much less difficulty in the workplace. Hysterical "hysterical" everywhere, but only in the appropriate situation. Anancasts successfully adapt to army conditions with strict routines and strict discipline, while those from the circle of dissocial and impulsive quickly decompensate.

Impulsive (excitable), on the contrary, are primarily surrounded by family troubles. They are intolerant in the family and present much less difficulty in the workplace. Hysterical "hysterical" everywhere, but only in the appropriate situation. Anancasts successfully adapt to army conditions with strict routines and strict discipline, while those from the circle of dissocial and impulsive quickly decompensate.

During the life of abnormal personalities, as a rule, shifts occur, most often coinciding with age crises. The most dangerous in terms of decompensation are periods of puberty and involution. The first of these can be divided into two phases - adolescence and youth. Adolescence (11-15 years) is accompanied by lability of emotions and extreme imbalance of behavior with violent affective reactions, abrupt unmotivated transitions from depression and tearfulness to unrestrained and noisy gaiety. Adolescents at this time strive for self-affirmation, become restless, restless, self-centered, stubborn, disobedient and quick-tempered: minor obstacles can become an occasion for affective outbursts with anger, fainting and hysterical seizures. There are also reactions of opposition, imitation, refusal [Gurieva V.A. et al., 1994]. For adolescence (16-20 years), along with persistent affective lability, a change in the range of interests and the whole system of thinking is characteristic with heightened reflection, a passion for "eternal", insoluble questions, complex philosophical systems (metaphysical intoxication). From the age of 20-25, interpersonal conflicts and other manifestations of decompensation gradually decrease, leading to violations of social adaptation or even subject to treatment. The character becomes more balanced, the ability to adapt to the changing demands of life gradually increases.

There are also reactions of opposition, imitation, refusal [Gurieva V.A. et al., 1994]. For adolescence (16-20 years), along with persistent affective lability, a change in the range of interests and the whole system of thinking is characteristic with heightened reflection, a passion for "eternal", insoluble questions, complex philosophical systems (metaphysical intoxication). From the age of 20-25, interpersonal conflicts and other manifestations of decompensation gradually decrease, leading to violations of social adaptation or even subject to treatment. The character becomes more balanced, the ability to adapt to the changing demands of life gradually increases.

In the period of age involution (45-60 years), psychopathic personality traits are again aggravated and become, according to W. Bayer (1951), hypertypical. In this age period, as well as at the age of puberty, the probability of mental imbalance sharply increases, which is associated with the aging process and concomitant cerebrovascular pathology: the flexibility of judgments and behavior in general decreases, activity and initiative weaken, conservatism and rigidity or, conversely, emotional lability, irritability, tearfulness. Psychopathic personalities at this age show a particular vulnerability to changes in their habitual life stereotype (change of job or place of residence, retirement, etc.).

Psychopathic personalities at this age show a particular vulnerability to changes in their habitual life stereotype (change of job or place of residence, retirement, etc.).

Among the external factors leading to decompensation, most often are the loss of persons from the immediate environment, the deterioration of one's own somatic condition, conflicts in the family [Mikhailova N. M., 1996]. The clinical picture is usually dominated by affective disorders with pessimism, a feeling of despondency, self-doubt, anxiety for the future. Sometimes decompensation is delayed. Massive hysterical manifestations, depressive-hypochondriac states with increased concern for one's health and exaggerated attention to the slightest somatic ailments are not uncommon. It is also possible a sharp increase in conflict with exaggerated truth-seeking and litigation.

In general, the dynamics of psychopathy is characterized by two main trends - compensation and decompensation; they are determined by the interaction of a number of factors (the severity and type of psychopathy, social conditions, age, etc. ).

).

During periods of predominant tendency to compensate, psychopathic personalities usually do not need medical attention and remain out of sight of the doctor; at the same time, the reaction to life events, somatic changes, age evolution approach the manifestations of the normal development of the personality. In fact, this is no longer a form of personality pathology that is revealed at certain stages of the life path, but a natural “movement” through life (“steps through life”), acquiring individual forms characteristic of each human destiny. In this regard, P. B. Gannushkin spoke about compensated, or “latent”, psychopathy and noted that the possibilities of establishing mental balance remain until the age of 25-30. Under favorable living conditions, persons with mild psychopathic character traits after a period of decompensation, for example, in adolescence, gradually become mentally more mature, their spiritual life acquires the features of inner harmony. Most of them quite fully adapt to the environment, correct their reactions and behavior, realize and critically evaluate their actions, lead a meaningful life.

The most favorable prospects for compensation are in the group of psychopathies of the schizoid pole, with anankastic, anxious (avoidant) personality disorder. With already established compensation, social adaptation in these types of psychopathy, even in very difficult living conditions, is less disturbed than in individuals of excitable and hysterical types. For them, any change in the situation, leading to the restriction of their willful demands or infringement of interests, can lead to a series of conflicts, often with alcohol excesses, dismissal from work, etc.

According to the materials of the follow-up study conducted by R. Tolle (1966), quite complete social adaptation occurs in psychopathic individuals who previously needed medical care and even hospitalization due to decompensation. The mechanisms of adaptation of such persons in society may be different depending on the type of psychopathy, social and other conditions. The most universal form of compensation is the strengthening of the features of rigidity, the emphasized desire for order. This form of compensation is possible in psychopathic personalities of various types. The desire for order extends to all spheres of life: from cleanliness in everyday life to commitment and accuracy in business affairs, punctuality in the distribution of time, a clear change of work and rest.

This form of compensation is possible in psychopathic personalities of various types. The desire for order extends to all spheres of life: from cleanliness in everyday life to commitment and accuracy in business affairs, punctuality in the distribution of time, a clear change of work and rest.

In the most general form, two main directions of differentiation of adaptation mechanisms can be distinguished. In the first of these, a certain balance of the psychopathic personality with the environment is achieved by narrowing the scope of activity and limiting communication with others to the limits of their endurance. Such a compensatory mechanism is more often observed with the predominance of anomalies of the dependent, asthenic, sensitive pole. Consistently enjoying a reputation for being obliging, conscientious, and very diligent workers, such people usually occupy a position below their professional capabilities. With difficulty overcoming the feeling of low value, indecision, they reluctantly and after great hesitation take on responsible tasks, do not strive for promotion. They want to work "behind the back" of the authoritative authorities, who take on all the representative functions and thus provide "protection" from unnecessary contacts and vicissitudes of the world around them.

They want to work "behind the back" of the authoritative authorities, who take on all the representative functions and thus provide "protection" from unnecessary contacts and vicissitudes of the world around them.

The second way of adaptation of psychopathic personalities is increased activity, the desire for practical success and the acquisition of material wealth. Although such activity sometimes runs counter to spiritual aspirations and former ideals, it serves as a means of self-affirmation, allowing one to escape from internal doubts, to overcome uncertainty and suspiciousness. The place of daydreaming and a penchant for fantasies is now occupied by pure pragmatism, "worldly grasp." In dealing with people, a new style of behavior is developed - previously uncharacteristic arrogance, pomposity, arrogance and even rudeness.

If a tendency to decompensation predominates in psychopathy, then the development curve of a psychopathic personality in many respects resembles the life curve of the mentally ill. This is pathological dynamics in the narrow sense. Clinical manifestations of decompensation sometimes go beyond the actual psychopathic and reach the level of psychotic states (reactions, phases). In case of pathological reactions associated with social, work, family conflicts, mental trauma, somatic hazards, as well as autochthonous disorders, medical interventions are required (both for expert and therapeutic purposes), including hospitalization. These short-term and long-term pathological stages of the dynamics of psychopathy are primarily the object of clinical research.

This is pathological dynamics in the narrow sense. Clinical manifestations of decompensation sometimes go beyond the actual psychopathic and reach the level of psychotic states (reactions, phases). In case of pathological reactions associated with social, work, family conflicts, mental trauma, somatic hazards, as well as autochthonous disorders, medical interventions are required (both for expert and therapeutic purposes), including hospitalization. These short-term and long-term pathological stages of the dynamics of psychopathy are primarily the object of clinical research.

It must be emphasized that psychopathologically complete states, traditionally attributed by P. B. Gannushkin and his school to the dynamics of psychopathy, are qualified in some modern systematics, including ICD-10, as independent clinical categories. In particular, manifestations of the phase dynamics of psychopathy can be considered according to the ICD-10 within the diagnostic headings "Depressive episode" (F32), "Cyclothymia" (F34. 0), "Dysthymia" (F34.1).

0), "Dysthymia" (F34.1).

Thus, in a number of disorders of minor psychiatry, a new system of correlations is being created. If the traditional concept of psychopathy is based on the idea of the etiological role of personality disorders in their dynamics, then the corresponding section of the ICD-10 is based on a different principle. According to this approach, there are clear nosographic boundaries between pathocharacterological formations, i.e., constitutional personality traits (these properties are qualified under the category "Personality Disorders") and clinical syndromal structures (the so-called actual syndromes), taken out of the dynamics of psychopathy. Although this provides for a variety of comorbid relationships (symptomatic and temporal comorbidity), the situation with the distinction between pathocharacterological and psychopathological disorders seems to be not so unambiguous. In accordance with ICD-10, personality disorders can be considered as a factor predisposing to the manifestation of psychopathological formations traditionally attributed to the dynamics of psychopathy, as well as a pathoplastic factor that modifies their evolution, affecting resistance/lability in relation to therapeutic effects. As clinical practice shows, in a number of cases, against the background of personality disorders, the formation of pathological disorders is observed, which, according to S. Taylor, W. J. Livesley (1995) cannot be considered "as existing separately". The structure and dynamics of the corresponding syndromes without signs of a course according to the stereotype of neuroses or endogenous diseases indicate their significant constitutional conditioning. In a number of such cases, it is impossible to separate painful manifestations from the personality structure [Petrilowitsch N., 1960]. In the interpretation of S. Yu. Tsirkin (1994), such disorders should be considered as a sign of diathesis, i.e. as functional disorders close to constitutional anomalies and devoid of the properties of a progressive disease process.

As clinical practice shows, in a number of cases, against the background of personality disorders, the formation of pathological disorders is observed, which, according to S. Taylor, W. J. Livesley (1995) cannot be considered "as existing separately". The structure and dynamics of the corresponding syndromes without signs of a course according to the stereotype of neuroses or endogenous diseases indicate their significant constitutional conditioning. In a number of such cases, it is impossible to separate painful manifestations from the personality structure [Petrilowitsch N., 1960]. In the interpretation of S. Yu. Tsirkin (1994), such disorders should be considered as a sign of diathesis, i.e. as functional disorders close to constitutional anomalies and devoid of the properties of a progressive disease process.

Psychopathological formations, which are formed on the same “axis” with pathocharacterological complexes and are their “prototypes” in form and content, most often act as constitutionally conditioned ones. For example, pathocharacterological disorders of the anxious (avoidant) type are associated with social phobia; congenital disgust, cleanliness (super cleanliness - according to S. Verhaest, R. Pier-loot, 1980) acts on the same "axis" with mysophobia; manifestations of anankastic warehouse - with obsessions of repeated control (rechecking habitual actions: locking doors, shutting off gas or water pipes, etc.). In a number of cases, the constitutionally characteristic accentuation of the sphere of self-consciousness, obsession with the processes of one's own intellectual or bodily sphere during periods of decompensation of psychopathy are manifested by symptom complexes of ideational depersonalization, overvalued or sensory hypochondria.

For example, pathocharacterological disorders of the anxious (avoidant) type are associated with social phobia; congenital disgust, cleanliness (super cleanliness - according to S. Verhaest, R. Pier-loot, 1980) acts on the same "axis" with mysophobia; manifestations of anankastic warehouse - with obsessions of repeated control (rechecking habitual actions: locking doors, shutting off gas or water pipes, etc.). In a number of cases, the constitutionally characteristic accentuation of the sphere of self-consciousness, obsession with the processes of one's own intellectual or bodily sphere during periods of decompensation of psychopathy are manifested by symptom complexes of ideational depersonalization, overvalued or sensory hypochondria.

The distinguishing features of constitutionally conditioned psychopathological phenomena include the isolation of manifestations and the persistence of symptom complexes, sometimes remaining unchanged for many years. The considered psychopathological formations act most often as facultative disorders and do not determine the state as a whole; they do not significantly disrupt social homeostasis and, as a rule, are egosynthonic, do not contradict conventional ideas about the normal manifestations of mental life, psychologically understandable habits. The transformation of pathopsychological disorders into psychopathological disorders that occurs within one “axis” sometimes occurs so smoothly that these phenomena are almost impossible to differentiate. So, H. C. Rumke (1967), considering the possibility of interpreting some obsessions as a quantitative strengthening of character, indicates that such personality traits as stinginess, excessive pedantry, scrupulousness, are already obsessions in themselves.

The transformation of pathopsychological disorders into psychopathological disorders that occurs within one “axis” sometimes occurs so smoothly that these phenomena are almost impossible to differentiate. So, H. C. Rumke (1967), considering the possibility of interpreting some obsessions as a quantitative strengthening of character, indicates that such personality traits as stinginess, excessive pedantry, scrupulousness, are already obsessions in themselves.

In accordance with the systematics of P. B. Gannushkin, pathological dynamics include: 1) spontaneous (autochthonous) phases, 2) pathological reactions, i.e. psychopathic, neurotic or psychotic symptom complexes that occur in response to external somatic or mental influences.

Phase-attacks occur in psychopathic individuals for no apparent reason, autochthonously; upon their completion, the state that was before the onset of the attack returns. The concept of spontaneity in the development of phases does not exclude their dependence on various external influences. So, V. M. Bekhterev (1886) noted their connection not only with psychogenic influences, but also with the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, somatic diseases, and even weather changes. However, all these factors play the role of triggering, provoking mechanisms and do not significantly affect either the clinical picture or the duration of the phase.

So, V. M. Bekhterev (1886) noted their connection not only with psychogenic influences, but also with the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, somatic diseases, and even weather changes. However, all these factors play the role of triggering, provoking mechanisms and do not significantly affect either the clinical picture or the duration of the phase.

Phases cannot always be considered within the framework of a temporary exacerbation of constitutional properties (depressive phases in constitutionally depressive individuals, manic phases in hyperthymic individuals, etc.). Their genesis appears to be more complex. Sometimes there is no direct dependence of the psychopathological structure of the phases on the warehouse of the psychopathic personality. So, for example, affective (depressive) phases can develop not only in cycloids, but also in personality disorders of a different type: in anxiety, hysterics and schizoids. The emergence of persistent phases indicates a deeper, compared with reactive decompensation, disturbance of mental activity. As P. B. Gannushkin noted (1964), for their appearance, in addition to the constitutional predisposition, "some adjuncts are necessary, perhaps to a certain extent similar to that which is added to the schizoid or epileptoid constitution when the corresponding progredient diseases occur." For example, with psychopathy of the anancaste-schizoid circle (similar anomalies are also defined as ideo-obsessive psychopathy [Sukhanov S.A., 1905], anancaste psychopathy [Schneider K., 1928; Weitbrecht J., 1973; Leonhard K., 1981] or an expansive subtype of schizoid psychopathy [Smulevich A. B., 1983; Snezhnevsky A.V., 1983] autochthonous obsessive phases are formed that do not have a close relationship with affective disorders. The clinical picture of such phases is limited to contrasting obsessions (aggressive obsessions) [Rasmussen S., Eysen J., 1991] in the form of monophobias (homicidophobia, fear of antisocial or other unseemly acts) and isolated obsessions of repeated control (mainly obsessive doubts of everyday content) [ Dorozhenek I.

As P. B. Gannushkin noted (1964), for their appearance, in addition to the constitutional predisposition, "some adjuncts are necessary, perhaps to a certain extent similar to that which is added to the schizoid or epileptoid constitution when the corresponding progredient diseases occur." For example, with psychopathy of the anancaste-schizoid circle (similar anomalies are also defined as ideo-obsessive psychopathy [Sukhanov S.A., 1905], anancaste psychopathy [Schneider K., 1928; Weitbrecht J., 1973; Leonhard K., 1981] or an expansive subtype of schizoid psychopathy [Smulevich A. B., 1983; Snezhnevsky A.V., 1983] autochthonous obsessive phases are formed that do not have a close relationship with affective disorders. The clinical picture of such phases is limited to contrasting obsessions (aggressive obsessions) [Rasmussen S., Eysen J., 1991] in the form of monophobias (homicidophobia, fear of antisocial or other unseemly acts) and isolated obsessions of repeated control (mainly obsessive doubts of everyday content) [ Dorozhenek I. Yu., 1999]. A characteristic feature of the dynamics of such phase states, which S.A. Sukhanov (1905) refers to as "extreme sharpening of the obsessive constitution", is a fairly rapid and complete reduction of contrasting obsessions without signs of transformation into other phobic or obsessional formations. The propensity for phase states is found relatively early in psychopathic personalities. They are most often seen in people under the age of 20. From the point of view of prognosis, the spontaneous phase indicates the possibility of periodic repetition of similar, autochthonous mental disorders.

Yu., 1999]. A characteristic feature of the dynamics of such phase states, which S.A. Sukhanov (1905) refers to as "extreme sharpening of the obsessive constitution", is a fairly rapid and complete reduction of contrasting obsessions without signs of transformation into other phobic or obsessional formations. The propensity for phase states is found relatively early in psychopathic personalities. They are most often seen in people under the age of 20. From the point of view of prognosis, the spontaneous phase indicates the possibility of periodic repetition of similar, autochthonous mental disorders.

The phase states include a wide range of psychopathological disorders - from the mildest unreasonable mood changes, transient fluctuations in affect and mental performance, which are most characteristic of psychopathic personalities, to severe long-term depression, which is relatively rare in psychopathy. The clinical picture of phase states is presented in the section "Affective disorders". Most of the asthenic, asthenohypochondriac and other neurotic conditions observed within the framework of the dynamics of psychopathy, which can also be attributed to psychopathic phases, are described in the sections "Neurotic disorders" and "Psychosomatic disorders". In contrast to the neurotic ones proper, their manifestations become more and more similar to pathocharacterological ones, they are not perceived as signs of the disease, being organically included (amalgamated) in the structure of personality anomalies. Obsessions act as eccentricities, phobias (especially agoraphobia, phobia of heights, etc.), impress as strange, well-established habits, accompanied by avoidant behavior (using only certain types of transport or routes of movement), but do not violate the general order of life and do not significantly affect the social adaptation. Somatoform disorders and hypochondriacal fears, initially acting as part of essential hypochondria, have "smooth transitions to hypochondriacal personality disorder" [Kuchenhoff J.

Most of the asthenic, asthenohypochondriac and other neurotic conditions observed within the framework of the dynamics of psychopathy, which can also be attributed to psychopathic phases, are described in the sections "Neurotic disorders" and "Psychosomatic disorders". In contrast to the neurotic ones proper, their manifestations become more and more similar to pathocharacterological ones, they are not perceived as signs of the disease, being organically included (amalgamated) in the structure of personality anomalies. Obsessions act as eccentricities, phobias (especially agoraphobia, phobia of heights, etc.), impress as strange, well-established habits, accompanied by avoidant behavior (using only certain types of transport or routes of movement), but do not violate the general order of life and do not significantly affect the social adaptation. Somatoform disorders and hypochondriacal fears, initially acting as part of essential hypochondria, have "smooth transitions to hypochondriacal personality disorder" [Kuchenhoff J. , 1985]; such transitions are manifested by an expanding tendency to insure the body, to assume the role of the patient. Symptoms of hyperthymia or dysthymia, gradually reduced to a subsyndromal level, are manifested, respectively, either by a tendency to exaltation, distraction, thoughtless actions, or in the form of pessimism and other gloomy character traits (constant discontent, grumbling).

, 1985]; such transitions are manifested by an expanding tendency to insure the body, to assume the role of the patient. Symptoms of hyperthymia or dysthymia, gradually reduced to a subsyndromal level, are manifested, respectively, either by a tendency to exaltation, distraction, thoughtless actions, or in the form of pessimism and other gloomy character traits (constant discontent, grumbling).

Pathological (psychogenic) reactions include shock reactions and protracted reactive states of both neurotic and psychotic levels. The content of psychopathological disorders that determine psychogenic reactions is dominated by a traumatic situation. The clinical picture of psychogenic reactions for one or another type of psychopathy is nonspecific and corresponds to that of psychogenic diseases.

The group of pathological reactions also includes constitutional psychopathic reactions (reactions “within the resources of the individual”, according to N.I. Felinskaya; characterological, psychopathic reactions, according to B. V. Shostakovich, 1997) and pathological developments. Constitutional reactions appear in situations that are subjectively difficult for a given person (forced change in the usual life stereotype, loss of loved ones, family drama, domestic conflicts, etc.). The clinical manifestation of such reactions may be a temporary significant increase in the main abnormal personality traits (reactions unambiguous to the type of psychopathy). As a rule, they are fleeting and last for several hours or days and appear in the form of violent affective discharges [Shostakovich B.V., 1997]. Sometimes there are psychopathic forms of response, ambiguous to the type of personality anomaly. They are due to a sharp increase in the optional features of an abnormal personality. In these cases, reactions may occur that contrast with the main properties of this type of personality: asthenic in excitable, aggressively explosive in anxious, explosive in sensitive schizoids. The universal forms of psychogenic response also include depressive, hypochondriacal, hysterical, less often paranoid reactions.

V. Shostakovich, 1997) and pathological developments. Constitutional reactions appear in situations that are subjectively difficult for a given person (forced change in the usual life stereotype, loss of loved ones, family drama, domestic conflicts, etc.). The clinical manifestation of such reactions may be a temporary significant increase in the main abnormal personality traits (reactions unambiguous to the type of psychopathy). As a rule, they are fleeting and last for several hours or days and appear in the form of violent affective discharges [Shostakovich B.V., 1997]. Sometimes there are psychopathic forms of response, ambiguous to the type of personality anomaly. They are due to a sharp increase in the optional features of an abnormal personality. In these cases, reactions may occur that contrast with the main properties of this type of personality: asthenic in excitable, aggressively explosive in anxious, explosive in sensitive schizoids. The universal forms of psychogenic response also include depressive, hypochondriacal, hysterical, less often paranoid reactions.

The concept of "pathological development" since the time of P. B. Gannushkin has been used in domestic psychiatry to refer to certain types of dynamics of psychopathy, reflecting the processes of decompensation of mental anomalies that differ in clinical manifestations. The type of pathological development of a psychopathic personality (as well as the development of a personality in general) is not predetermined in advance by certain constitutional features, it is not a consequence of only internal causes. According to N. Petrilowitsch (1966), pathological development is the response of an abnormal personality to an unfavorable relationship with the outside world. In other words, pathological development is always the result of the interaction of a complex of constitutional, psychogenic, somatogenic and other factors. Such interaction determines this or that pathological deviation in the dynamics of the mental activity of an abnormal personality.

In the clinical aspect, pathological development is a unilateral persistent increase, hypertrophy of manifest (obligate or facultative) or latent features of an abnormal personality. A striking example of the pathological dynamics of the type under consideration are paranoid (including litigious and sensitive) developments. They are observed not only in paranoid, but also in other types of psychopathy (in schizoids, anancastes, etc.), in persons prone to the formation of overvalued formations. In this case, we are talking about a special group of psychopathological disorders, which are, as it were, a mirror reflection of catatim pathocharacterological complexes. So, in persons with a catatymic complex of the “fanatics of feelings” type, phenomena of erotic obsession (obsession) are formed, in pathological jealous people - obsessive jealousy. If there is a phenomenon of painful dependence in the structure of personality anomalies [Andryushchenko A. V. et al., 1999; Horney K., 1950] manifestation of codependency depression is possible [Korolenko Ts. P., 1998] or in multiple personality disorder, also referred to as “dissociative identity disorder” [Alien J. G. et al.

A striking example of the pathological dynamics of the type under consideration are paranoid (including litigious and sensitive) developments. They are observed not only in paranoid, but also in other types of psychopathy (in schizoids, anancastes, etc.), in persons prone to the formation of overvalued formations. In this case, we are talking about a special group of psychopathological disorders, which are, as it were, a mirror reflection of catatim pathocharacterological complexes. So, in persons with a catatymic complex of the “fanatics of feelings” type, phenomena of erotic obsession (obsession) are formed, in pathological jealous people - obsessive jealousy. If there is a phenomenon of painful dependence in the structure of personality anomalies [Andryushchenko A. V. et al., 1999; Horney K., 1950] manifestation of codependency depression is possible [Korolenko Ts. P., 1998] or in multiple personality disorder, also referred to as “dissociative identity disorder” [Alien J. G. et al. "phantom" of the continuing life of the deceased object of affection. This catathymic complex is similar to the phenomena of symbiotic attachment and is associated with the fear of being abandoned by the person with whom the patient is connected through the mechanism of "adhesive identification". In such cases, we are talking about the predominance of anxious traits with fear of separation [Akiskal H., 1987], attachment-dependent or “clinging” character traits [Parkes C. M., 1985].

"phantom" of the continuing life of the deceased object of affection. This catathymic complex is similar to the phenomena of symbiotic attachment and is associated with the fear of being abandoned by the person with whom the patient is connected through the mechanism of "adhesive identification". In such cases, we are talking about the predominance of anxious traits with fear of separation [Akiskal H., 1987], attachment-dependent or “clinging” character traits [Parkes C. M., 1985].

The aggravation of pathocharacterological traits usually occurs after psychotraumatic events, especially deeply affecting the patient's imagination - by catatymic mechanisms that reveal affinity for overvalued complexes, for example, in a situation of infringement of copyright for industrial improvements. As the conflict unfolds, patients become more and more suspicious, anxious, insistently demand more and more new tests, conduct many years of litigation, clearly exaggerating the significance of their rationalization proposals, appeal to public opinion, turn to higher authorities. In other cases, interest in literary creativity, keeping diaries and various kinds of records, which did not interfere with professional activity for many years, during the period of involution against the background of the initial manifestations of cerebral atherosclerosis becomes graphomania. Such subjects sit down to write memoirs, the content of which is equated with the most important historical documents, and persistently seek their publication.

In other cases, interest in literary creativity, keeping diaries and various kinds of records, which did not interfere with professional activity for many years, during the period of involution against the background of the initial manifestations of cerebral atherosclerosis becomes graphomania. Such subjects sit down to write memoirs, the content of which is equated with the most important historical documents, and persistently seek their publication.

They willingly talk about their creative plans, apply to various editions, speak with disdain about other writers, claim that their manuscripts are not inferior in artistic value to the works of the most prominent writers. In some psychopathic individuals, long-standing conflict relationships with relatives due to a change in the situation or in connection with some psychogenic moments can expand to the extent of an intra-family “struggle”, litigious activity (complaints to public organizations, the police, proceedings in friendly courts, etc. ) . In some cases of this paranoid development, even isolated ideas of harm and persecution may arise.

) . In some cases of this paranoid development, even isolated ideas of harm and persecution may arise.

Pathological developments are divided into constitutional (or psychopathic, according to H. Binder, 1967) and situational, also defined as post-reactive or psychogenic [Kerbikov O. V., Felinskaya N. I., 1965; Naku A. G., Revenko M. G., Oprya N. A., 1980]. With constitutional developments, the pathological dynamics is primarily due to internal predisposition, and the influences of the outside world do not represent any extraordinary stimuli (everyday, almost ordinary influences). Psychogenic developments are formed after reactive states or are associated with long-term severe psycho-traumatic effects and chronic conflict situations (pathocharacterological development, according to O. V. Kerbikov and N. I. Felinskaya). With psychogenic developments, facultative and sometimes latent features of the abnormal personality are more often enhanced. As P. B. Gannushkin points out, such developments “use” the constitution not completely, not entirely, but partially, selectively, that is, according to the situation.