Suicidal thoughts bipolar

Bipolar Depression: The Lows We Don’t Talk About Enough

SEP. 22, 2021

By Katherine Ponte, JD, MBA, CPRP

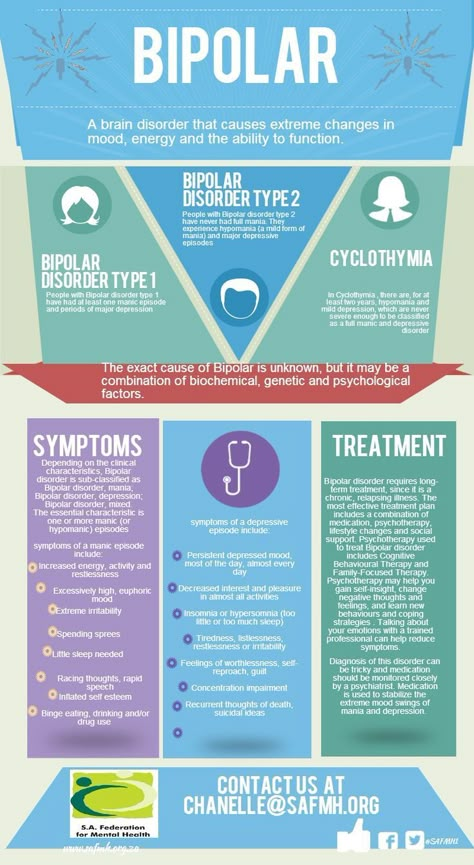

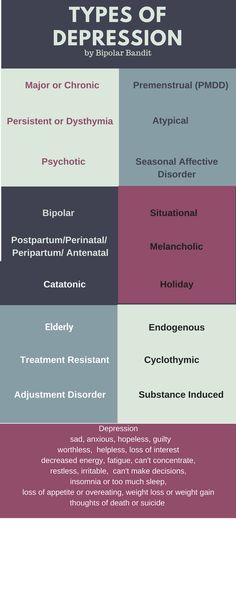

The highs and lows of bipolar disorder can both be extremely challenging. The name of the illness itself recognizes these two sides (depression and mania), but many people don’t fully understand the role of depression in bipolar disorder. Those who do, like our caregivers and treatment providers, seem to focus solely on the “mania” component of the condition. They often view the highs of mania as the most dangerous states to be avoided and tamed — and they may even find the depressive side to be a relief from the unpredictable highs.

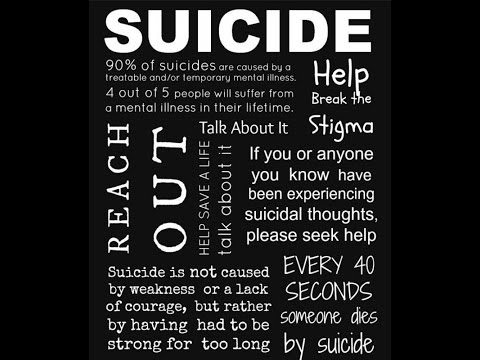

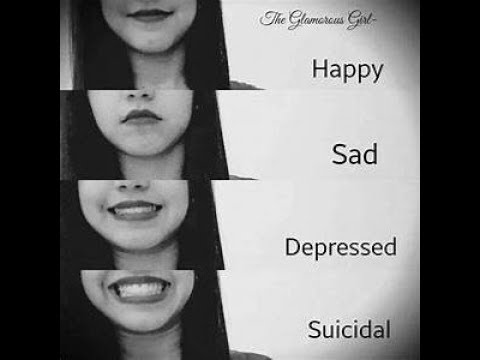

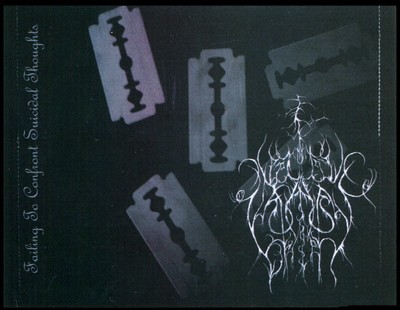

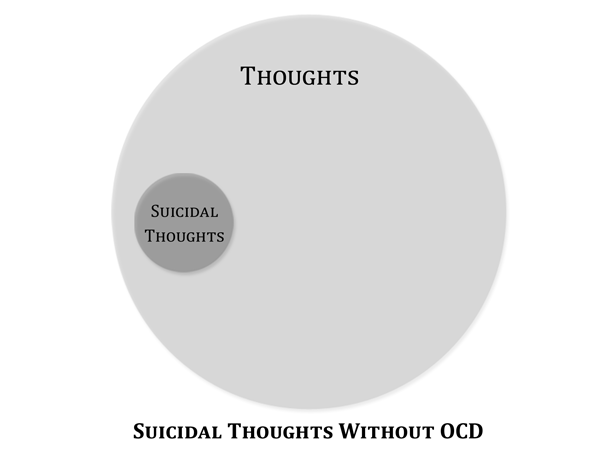

However, it’s during the lows that people with bipolar disorder are at the greatest risk of suicide. People with bipolar disorder experience high suicide rates — up to 19% of us die by suicide and up to 50% of us will make a non-fatal suicide attempt — and suicide risk is strongly associated with depressive phases.

Personally, I experienced extended periods of suicidal ideation due to prolonged periods of depression. I often explain the sides of bipolar disorder by saying, “It’s the mania that gets you into trouble, but it’s the depression that can kill you.”

Given that depression is the more pervasive symptom of bipolar disorder for most people, and given its detrimental impacts on so many areas of our lives, I believe caregivers and providers need to focus more on bipolar depression. Everybody's experience is different, but in my in my situation, overlooking depression has prolonged and worsened symptoms for many reasons:

Delays in Getting a Correct Diagnosis

A depressive episode preceded my first manic episode, so I was diagnosed with and treated for unipolar depression. It was a year before I was properly diagnosed. This is common for people diagnosed with bipolar disorder — and the typical delay in getting a correct diagnosis is six to eight years.

The Duration of Symptoms

I have experienced much longer depressive phases than manic phases, which are relatively short-lived. Depressive phases could last from a few months to years. They were relentless. While my manic phases could be quickly treated with medication, my depressive episodes were difficult to address with medication.

Depressive phases could last from a few months to years. They were relentless. While my manic phases could be quickly treated with medication, my depressive episodes were difficult to address with medication.

The Consequences of Mania

Typically, after my manic episode, deep depression would set in. In fact, studies show that depressive episodes frequently follow manic episodes. It was a steep fall from the highs of my mania into severe depression.

My depression was worsened by the deep shame and embarrassment, guilt and regret I experienced due to my actions while manic. This behavior included frantic rambling emails, often stemming for paranoid fixations, other destructive behaviors, interpersonal conflict and public humiliation. As my mania subsided, I appreciated just how bad my behavior had been, contributing to my depressive symptoms.

The Aftermath of Hospitalization

My three involuntarily hospitalizations due to manic episodes were extremely traumatic. People with mental illness experience some of the highest suicide rates after psychiatric hospitalization. During the first three months after discharge, their rate of suicide is 100 times the suicide rate of the general population, according to a meta-analysis of studies. The weeks and months following hospitalization were certainly among the lowest points I have experienced in my life.

People with mental illness experience some of the highest suicide rates after psychiatric hospitalization. During the first three months after discharge, their rate of suicide is 100 times the suicide rate of the general population, according to a meta-analysis of studies. The weeks and months following hospitalization were certainly among the lowest points I have experienced in my life.

Lack of Caregiver Attention

My caregiver expressed extreme alarm over my hypomanic and manic episodes, but relatively little concern over my lows. When I started to become more exuberant, my caregiver was hypervigilant and focused on controlling my activities, insistent that I seek treatment and remain in constant contact with my psychiatrist to prevent a manic episode.

During my lows, my caregiver seemed relieved with my inactivity. He seemed unaware of the extent of my struggles, even though he was aware that I was often unable to get out of bed. I felt uncared for, isolated and abandoned, which worsened my depression. He did not insist on treatment and intervention like he did during my manic phases. I believe this contributed to my depression being undertreated.

He did not insist on treatment and intervention like he did during my manic phases. I believe this contributed to my depression being undertreated.

The role of a caregiver in identifying and encouraging treatment of bipolar depression is critical. When we are depressed, we may lack a will to live, we may neglect treatment (such as missing appointments). We can lose hope and even cease communication. Caregivers are the best placed to observe these changes in behavior and activities and encourage treatment.

Lack of Treatment Focus

Likewise, my then-psychiatrist focused their treatment on preventing the next manic episode and hospitalization. On multiple occasions, I explained how severe my depression was and asked them to address it. They largely ignored my concerns. In addition, their treatment approach was highly sedating medication to reduce the risk of mania. This approach further contributed to my depression.

I was so highly sedated that I could not work nor have normal social relationships. My psychiatrist also discouraged social activities out of concern for the stress they might cause me, possibly triggering a manic episode. I felt as though the treatment focus was minimizing the suffering of others who had to

deal with me rather than actually helping me. I resigned myself to this lesser life, which significantly contributed to my depression.

My psychiatrist also discouraged social activities out of concern for the stress they might cause me, possibly triggering a manic episode. I felt as though the treatment focus was minimizing the suffering of others who had to

deal with me rather than actually helping me. I resigned myself to this lesser life, which significantly contributed to my depression.

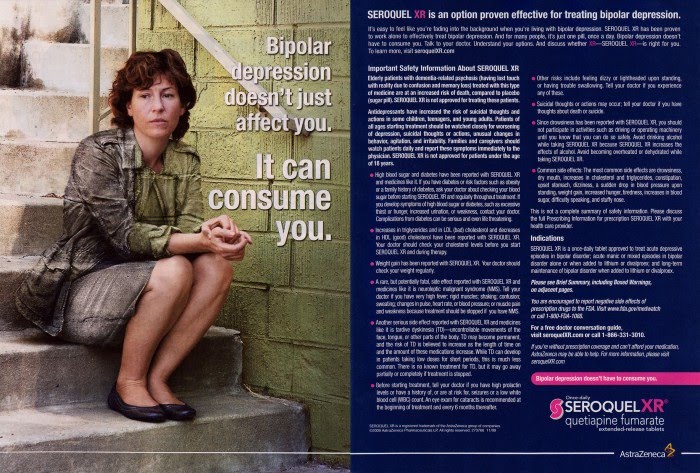

My psychiatrist refused to take calculated risks that could have improved the quality of my life. For example, they did not prescribe antidepressants which they feared might trigger a manic episode. As a result, I believe my depression was undertreated. I believed that there was no effective treatment for my depression which was incredibly disheartening.

However, bipolar depression can be effectively treated, and there are medications that have been specifically approved for bipolar depression — some of which have been very effective for me.

Activity Being Equated to Mania

Depression can lead to extreme lethargy and lack of motivation, which can make it extremely difficult to take part in the normal activities of life. Disappointingly, practitioners may view moments of optimism and activity that break through the depression and inactivity as a reason for concern.

Disappointingly, practitioners may view moments of optimism and activity that break through the depression and inactivity as a reason for concern.

Our caregivers and doctors may mistake these signs of life for early signs of mania. Their preemptive efforts to prevent the potential manic episode can also reinforce the inactivity. This can keep patients in a depressive state.

Ultimately, bipolar depression is ignored, minimized and dismissed all too often. I lost over a decade of my life to depression, which still causes me deep sorrow. It’s even more tragic that so many people lose their lives to suicide.

Too often, actions and factors that can worsen depression are considered acceptable in order to prevent mania. This only makes it significantly more difficult to overcome depression and extremely difficult to reach recovery. It is a vicious cycle.

I am now happily living in recovery, and I have been relatively depression-free for several years now. Now, my caregiver acts on my depression, my doctor cares equally about the highs and lows and I’m finally on the appropriate medication. Notably, acknowledging and treating my depression also addressed my mania. Since being effectively treated for my depression, I have not experienced a manic episode. I am living proof that the highs and lows deserve equal attention and respect and care.

Notably, acknowledging and treating my depression also addressed my mania. Since being effectively treated for my depression, I have not experienced a manic episode. I am living proof that the highs and lows deserve equal attention and respect and care.

Katherine Ponte is happily living in recovery from severe bipolar I disorder. She’s the Founder of ForLikeMinds’ mental illness peer support community, BipolarThriving: Recovery Coaching and Psych Ward Greeting Cards. Katherine is also a faculty member of the Yale University Program for Recovery and Community Health and has authored ForLikeMinds: Mental Illness Recovery Insights.

We’re always accepting submissions to the NAMI Blog! We feature the latest research, stories of recovery, ways to end stigma and strategies for living well with mental illness. Most importantly: We feature your voices.

Check out our Submission Guidelines for more information.

LEARN MORE

Suicide Risk in Bipolar Disorder: A Brief Review

1. Rihmer Z., Dome P. Suicide and Bipolar Disorder. In: Zarate C.A.J., Manji H.K., editors. Bipolar Depression: Molecular Neurobiology, Clinical Diagnosis, and Pharmacotherapy. 2nd ed. Springer; Bern, Switzerland: 2017. [Google Scholar]

Rihmer Z., Dome P. Suicide and Bipolar Disorder. In: Zarate C.A.J., Manji H.K., editors. Bipolar Depression: Molecular Neurobiology, Clinical Diagnosis, and Pharmacotherapy. 2nd ed. Springer; Bern, Switzerland: 2017. [Google Scholar]

2. Rihmer Z., Gonda X., Döme P. The Assessment and Management of SuicideRrisk in Bipolar Disorder. In: Carvalho A.F., Vieta E., editors. The Treatment of Bipolar Disorder: Integrative Clinical Strategies and Future Directions. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2017. [Google Scholar]

3. Staudt Hansen P., Frahm Laursen M., Grontved S., Puggard Vogt Straszek S., Licht R.W., Nielsen R.E. Increasing mortality gap for patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder—A nationwide study with 20 years of follow-up. Bipolar Disord. 2019;21:270–275. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12684. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Hayes J.F., Marston L., Walters K., King M.B., Osborn D.P.J. Mortality gap for people with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: UK-based cohort study 2000–2014. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2017;211:175–181. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.117.202606. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Br. J. Psychiatry. 2017;211:175–181. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.117.202606. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Bauer M., Andreassen O.A., Geddes J.R., Vedel Kessing L., Lewitzka U., Schulze T.G., Vieta E. Areas of uncertainties and unmet needs in bipolar disorders: Clinical and research perspectives. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:930–939. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30253-0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. World Health Organization . Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative. WHO Press; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. [Google Scholar]

7. Turecki G., Brent D.A. Suicide and suicidal behaviour. Lancet. 2016;387:1227–1239. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00234-2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Plans L., Barrot C., Nieto E., Rios J., Schulze T.G., Papiol S., Mitjans M., Vieta E., Benabarre A. Association between completed suicide and bipolar disorder: A systematic review of the literature. J. Affect. Disord. 2019;242:111–122. doi: 10. 1016/j.jad.2018.08.054. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

1016/j.jad.2018.08.054. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Rihmer Z., Döme P. Major Mood Disorders and Suicidal Behavior. In: O’Connor R.C., Pirkis J., editors. The International Handbook of Suicide Prevention: Research, Policy and Practice. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.; Chichester, UK: 2016. [Google Scholar]

10. Malhi G.S., Outhred T., Das P., Morris G., Hamilton A., Mannie Z. Modeling suicide in bipolar disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20:334–348. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12622. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Vieta E., Berk M., Schulze T.G., Carvalho A.F., Suppes T., Calabrese J.R., Gao K., Miskowiak K.W., Grande I. Bipolar disorders. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2018;4:18008. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.8. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Pompili M., Gonda X., Serafini G., Innamorati M., Sher L., Amore M., Rihmer Z., Girardi P. Epidemiology of suicide in bipolar disorders: A systematic review of the literature. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15:457–490. doi: 10.1111/bdi. 12087. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12087. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Schaffer A., Isometsa E.T., Tondo L., Moreno D.H., Sinyor M., Kessing L.V., Turecki G., Weizman A., Azorin J.-M., Ha K., et al. Epidemiology, neurobiology and pharmacological interventions related to suicide deaths and suicide attempts in bipolar disorder: Part I of a report of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force on Suicide in Bipolar Disorder. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2015;49:785–802. doi: 10.1177/0004867415594427. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Desîlets A., Labossière M., McGirr A., Turecki G. Schizophrenia, Other Psychotic Disorders, and Suicidal Behavior. In: O’Connor R.C., Pirkis J., editors. The International Handbook of Suicide Prevention. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; Chichester, UK: 2016. [Google Scholar]

15. Yatham L.N., Kennedy S.H., Parikh S.V., Schaffer A., Bond D.J., Frey B.N., Sharma V., I Goldstein B., Rej S., Beaulieu S., et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20:97–170. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12609. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Bipolar Disord. 2018;20:97–170. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12609. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Isometsa E. Suicidal behaviour in mood disorders—Who, when, and why? Can. J. Psychiatry. 2014;59:120–130. doi: 10.1177/070674371405900303. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Hansson C., Joas E., Palsson E., Hawton K., Runeson B., Landen M. Risk factors for suicide in bipolar disorder: A cohort study of 12,850 patients. Acta Psychiatry Scand. 2018;138:456–463. doi: 10.1111/acps.12946. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Tondo L., Pompili M., Forte A., Baldessarini R.J. Suicide attempts in bipolar disorders: Comprehensive review of 101 reports. Acta Psychiatry Scand. 2016;133:174–186. doi: 10.1111/acps.12517. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Schaffer A., Isometsa E.T., Tondo L., Moreno D.H., Turecki G., Reis C., Cassidy F., Sinyor M., Azorin J.-M., Kessing L.V., et al. International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force on Suicide: Meta-analyses and meta-regression of correlates of suicide attempts and suicide deaths in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17:1–16. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Bipolar Disord. 2015;17:1–16. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Choi K.W., Na E.J., Hong J.P., Cho M.J., Fava M., Mischoulon D., Jeon H.J. Comparison of suicide attempts in individuals with major depressive disorder with and without history of subthreshold hypomania: A nationwide community sample of Korean adults. J. Affect. Disord. 2019;248:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.01.022. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Park Y.M., Lee B.H. Treatment response in relation to subthreshold bipolarity in patients with major depressive disorder receiving antidepressant monotherapy: A post hoc data analysis (KOMDD study) Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2016;12:1221–1227. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S104188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22. Koirala P., Hu B., Altinay M., Li M., DiVita A.L., Bryant K.A., Karne H.S., Fiedorowicz J.G., Anan A. Sub-threshold bipolar disorder in medication-free young subjects with major depression: Clinical characteristics and antidepressant treatment response. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2019;110:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.12.006. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J. Psychiatr. Res. 2019;110:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.12.006. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. Dome P., Gonda X., Rihmer Z. Effects of smoking on health outcomes in bipolar disorder with a special focus on suicidal behavior. Neuropsychiatry. 2012;2:429–441. doi: 10.2217/npy.12.51. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

24. Latalova K., Kamaradova D., Prasko J. Suicide in bipolar disorder: A review. Psychiatr. Danub. 2014;26:108–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Gonda X., Pompili M., Serafini G., Montebovi F., Campi S., Dome P., Duleba T., Girardi P., Rihmer Z. Suicidal behavior in bipolar disorder: Epidemiology, characteristics and major risk factors. J. Affect. Disord. 2012;143:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.04.041. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Da Silva Costa L., Alencar A.P., Nascimento Neto P.J., dos Santos Mdo S., da Silva C.G., Pinheiro Sde F., Silveira R.T., Bianco B.A.V., Junior R.F.F.P., De Lima M.A.P., et al. Risk factors for suicide in bipolar disorder: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2015;170:237–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.09.003. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J. Affect. Disord. 2015;170:237–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.09.003. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

27. Michaels M.S., Balthrop T., Pulido A., Rudd M.D., Joiner T.E. Is the Higher Number of Suicide Attempts in Bipolar Disorder vs. Major Depressive Disorder Attributable to Illness Severity? Arch. Suicide Res. 2018;22:46–56. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2017.1319308. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

28. Pallaskorpi S., Suominen K., Ketokivi M., Valtonen H., Arvilommi P., Mantere O., Leppämäki S., Isometsä E. Incidence and predictors of suicide attempts in bipolar I and II disorders: A 5-year follow-up study. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19:13–22. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12464. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Vazquez G.H., Gonda X., Lolich M., Tondo L., Baldessarini R.J. Suicidal Risk and Affective Temperaments, Evaluated with the TEMPS-A Scale: A Systematic Review. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry. 2018;26:8–18. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000153. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

30. Persons J.E., Coryell W.H., Solomon D.A., Keller M.B., Endicott J., Fiedorowicz J.G. Mixed state and suicide: Is the effect of mixed state on suicidal behavior more than the sum of its parts? Bipolar Disord. 2018;20:35–41. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12538. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Persons J.E., Coryell W.H., Solomon D.A., Keller M.B., Endicott J., Fiedorowicz J.G. Mixed state and suicide: Is the effect of mixed state on suicidal behavior more than the sum of its parts? Bipolar Disord. 2018;20:35–41. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12538. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

31. Fiedorowicz J.G., Persons J.E., Assari S., Ostacher M.J., Zandi P., Wang P.W., Thase M.E., Frye M.A., Coryell W. Depressive symptoms carry an increased risk for suicidal ideation and behavior in bipolar disorder without any additional contribution of mixed symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 2019;246:775–782. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.057. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

32. Tidemalm D., Haglund A., Karanti A., Landen M., Runeson B. Attempted suicide in bipolar disorder: Risk factors in a cohort of 6086 patients. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e94097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094097. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

33. Manchia M., Hajek T. , O’Donovan C., Deiana V., Chillotti C., Ruzickova M., Del Zompo M., Alda M. Genetic risk of suicidal behavior in bipolar spectrum disorder: Analysis of 737 pedigrees. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15:496–506. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12088. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, O’Donovan C., Deiana V., Chillotti C., Ruzickova M., Del Zompo M., Alda M. Genetic risk of suicidal behavior in bipolar spectrum disorder: Analysis of 737 pedigrees. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15:496–506. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12088. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

34. Bauer M., Glenn T., Alda M., Andreassen O.A., Angelopoulos E., Ardau R., Ayhan Y., Baethge C., Bauer R., Baune B.T., et al. Association between solar insolation and a history of suicide attempts in bipolar I disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2019;113:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.03.001. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

35. Caribe A.C., Studart P., Bezerra-Filho S., Brietzke E., Nunes Noto M., Vianna-Sulzbach M., Kapczinski F., Neves F.S., Corrêa H., Miranda-Scippa A. Is religiosity a protective factor against suicidal behavior in bipolar I outpatients? J. Affect. Disord. 2015;186:156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.07.024. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

36. Gearing R.E., Alonzo D. Religion and Suicide: New Findings. J. Relig. Health. 2018;57:2478–2499. doi: 10.1007/s10943-018-0629-8. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J. Relig. Health. 2018;57:2478–2499. doi: 10.1007/s10943-018-0629-8. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

37. Schaffer A., Isometsa E.T., Azorin J.M., Cassidy F., Goldstein T., Rihmer Z., Sinyor M., Tondo L., Moreno D.H., Turecki G., et al. A review of factors associated with greater likelihood of suicide attempts and suicide deaths in bipolar disorder: Part II of a report of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force on Suicide in Bipolar Disorder. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2015;49:1006–1020. doi: 10.1177/0004867415594428. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

38. Novick D.M., Swartz H.A., Frank E. Suicide attempts in bipolar I and bipolar II disorder: A review and meta-analysis of the evidence. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00786.x. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

39. Angst J., Sellaro R., Angst F. Long-term outcome and mortality of treated versus untreated bipolar and depressed patients: A preliminary report. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 1998;2:115–119. doi: 10.3109/13651509809115343. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 1998;2:115–119. doi: 10.3109/13651509809115343. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

40. Smith K.A., Cipriani A. Lithium and suicide in mood disorders: Updated meta-review of the scientific literature. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19:575–586. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12543. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

41. Tondo L., Baldessarini R.J. Antisuicidal Effects in Mood Disorders: Are They Unique to Lithium? Pharmacopsychiatry. 2018;51:177–188. doi: 10.1055/a-0596-7853. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

42. Cipriani A., Hawton K., Stockton S., Geddes J.R. Lithium in the prevention of suicide in mood disorders: Updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f3646. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3646. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

43. Chen T.Y., Kamali M., Chu C.S., Yeh C.B., Huang S.Y., Mao W.C., Lin P.-Y., Chen Y.-W., Tseng P.-T., Hsu C.-Y. Divalproex and its effect on suicide risk in bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of multinational observational studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2019;245:812–818. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.093. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J. Affect. Disord. 2019;245:812–818. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.093. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

44. Caley C.F., Perriello E., Golden J. Antiepileptic drugs and suicide-related outcomes in bipolar disorder: A descriptive review of published data. Ment. Health Clin. 2018;8:138–147. doi: 10.9740/mhc.2018.05.138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

45. Alberich S., Martinez-Cengotitabengoa M., Lopez P., Zorrilla I., Nunez N., Vieta E., González-Pinto A. Efficacy and safety of ketamine in bipolar depression: A systematic review. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2017;10:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.rpsm.2016.05.005. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

46. Lopez-Diaz A., Fernandez-Gonzalez J.L., Lujan-Jimenez J.E., Galiano-Rus S., Gutierrez-Rojas L. Use of repeated intravenous ketamine therapy in treatment-resistant bipolar depression with suicidal behaviour: A case report from Spain. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2017;7:137–140. doi: 10.1177/2045125316675578. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

[PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

47. Andrade C. Ketamine for Depression, 6: Effects on Suicidal Ideation and Possible Use as Crisis Intervention in Patients at Suicide Risk. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2018;79 doi: 10.4088/JCP.18f12242. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

48. Grunebaum M.F., Ellis S.P., Keilp J.G., Moitra V.K., Cooper T.B., Marver J.E., Burke A.K., Milak M.S., Sublette M.E., Oquendo M.A., et al. Ketamine versus midazolam in bipolar depression with suicidal thoughts: A pilot midazolam-controlled randomized clinical trial. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19:176–183. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12487. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

49. Sanacora G., Katz R. Ketamine: A Review for Clinicians. Focus. 2018;16:243–250. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.20180012. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

50. Sanches M., Quevedo J., Soares J.C. Treatment Resistance in Bipolar Disorders. In: Kim Y.-K., editor. Treatment Resistance in Psychiatry. Springer Nature; Singapore: 2019. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

51. Fountoulakis K.N., Grunze H., Vieta E., Young A., Yatham L., Blier P., Kasper S., Moeller H.J. The International College of Neuro-Psychopharmacology (CINP) Treatment Guidelines for Bipolar Disorder in Adults (CINP-BD-2017), Part 3: The Clinical Guidelines. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;20:180–195. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyw109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

52. Liang C.S., Chung C.H., Ho P.S., Tsai C.K., Chien W.C. Superior anti-suicidal effects of electroconvulsive therapy in unipolar disorder and bipolar depression. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20:539–546. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12589. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

53. Bahji A., Hawken E.R., Sepehry A.A., Cabrera C.A., Vazquez G. ECT beyond unipolar major depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis of electroconvulsive therapy in bipolar depression. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2019;139:214–226. doi: 10.1111/acps.12994. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

54. Mendez-Bustos P. , Calati R., Rubio-Ramirez F., Olie E., Courtet P., Lopez-Castroman J. Effectiveness of Psychotherapy on Suicidal Risk: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Front. Psychol. 2019;10:277. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00277. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, Calati R., Rubio-Ramirez F., Olie E., Courtet P., Lopez-Castroman J. Effectiveness of Psychotherapy on Suicidal Risk: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Front. Psychol. 2019;10:277. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00277. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

55. Inder M.L., Crowe M.T., Luty S.E., Carter J.D., Moor S., Frampton C.M., Joyce P.R. Prospective rates of suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury by young people with bipolar disorder participating in a psychotherapy study. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2016;50:167–173. doi: 10.1177/0004867415622268. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

56. Rucci P., Frank E., Kostelnik B., Fagiolini A., Mallinger A.G., Swartz H.A., Thase M.E., Siegel L., Wilson D., Kupfer D.J. Suicide attempts in patients with bipolar I disorder during acute and maintenance phases of intensive treatment with pharmacotherapy and adjunctive psychotherapy. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2002;159:1160–1164. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1160. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

57. Weinstein S.M., Cruz R.A., Isaia A.R., Peters A.T., West A.E. Child- and Family-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Pediatric Bipolar Disorder: Applications for Suicide Prevention. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2018;48:797–811. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12416. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Weinstein S.M., Cruz R.A., Isaia A.R., Peters A.T., West A.E. Child- and Family-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Pediatric Bipolar Disorder: Applications for Suicide Prevention. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2018;48:797–811. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12416. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

58. Goldstein T.R., Fersch-Podrat R.K., Rivera M., Axelson D.A., Merranko J., Yu H., Brent D.A., Birmaher B. Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with bipolar disorder: Results from a pilot randomized trial. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2015;25:140–149. doi: 10.1089/cap.2013.0145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

59. Wasserman D., Rihmer Z., Rujescu D., Sarchiapone M., Sokolowski M., Titelman D., Zalsman G., Zemishlany Z., Carli V. The European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance on suicide treatment and prevention. Eur. Psychiatry. 2012;27:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.06.003. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Get help & support for suicide

If you’re in emotional distress or suicidal crisis, find help in your area with Find a helpline.

If you believe that someone else is in danger of suicide and you have their contact information, contact your local law enforcement for immediate help. You can also encourage the person to contact a suicide prevention hotline using the information above.

Learn more about personal crisis information with Google Search.

Google’s crisis information comes from high-quality websites, partnerships, medical professionals, and search results.

Important: Partnerships vary by country and region.

| Country | Hotline organization | Website | Phone number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | Centro de Asistencia al Suicida | www.asistenciaalsuicida.org | (011) 5275-1135 |

| Australia | Lifeline Australia | www. lifeline.org lifeline.org | 13 11 14 |

| Austria | Telefon Seelsorge Osterreich | www.telefonseelsorge.at | 142 |

| Belgium | Center de Prevention du Suicide | www.preventionsuicide.be | 0800 32 123 |

| Belgium | CHS Helpline | www.chsbelgium.org | 02 648 40 14 |

| Belgium | Zelfmoord 1813 | www.zelfmoord1813.be | 1813 |

| Brazil | Centro de Valorização da Vida | www.cvv.org | 188 |

| Canada | Crisis Services Canada | crisisservicescanada.ca | 833-456-4566 |

| Chile | Ministry of Health of Chile | www.hospitaldigital. gob gob | 6003607777 |

| China | Beijing Suicide Research and Prevention Center | www.crisis.org | 800-810-1117 |

| Costa Rica | Colegio de Profesionales en Psicologia de Costa Rica | psicologiacr.com/aqui-estoy | 2272-3774 |

| France | SOS Amitié | www.sos-amitie.org | 09 72 39 40 50 |

| Germany | Telefon Seelsorge Deutschland | www.telefonseelsorge.de | 0800 1110111 |

| Hong Kong | Suicide Prevention Services | www.sps.org | 2382 0000 |

| India | iCall Helpline | icallhelpline.org | 9152987821 |

| Ireland | Samaritans Ireland | www. samaritans.org/how-we-can-help samaritans.org/how-we-can-help | 116 123 |

| Israel | [Eran] ער"ן | www.eran.org | 1201 |

| Italy | Samaritans Onlus | www.samaritansonlus.org | 800 86 00 22 |

| Japan | Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology | www.mext.go.jp | 81-0120-0-78310 |

| Japan | Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan | www.mhlw.go | 0570-064-556 |

| Malaysia | Befrienders KL | www.befrienders.org | 03-76272929 |

| Netherlands | 113Online | www.113.nl | 0800-0113 |

| New Zealand | Lifeline Aotearoa Incorporated | www. lifeline.org lifeline.org | 0800 543 354 |

| Norway | Mental Helse | mentalhelse.no | 116 123 |

| Pakistan | Umang Pakistan | www.umang.com.pk/ | 0311-7786264 |

| Philippines | Department of Health - Republic of the Philippines | doh.gov.ph/NCMH-Crisis-Hotline | 0966-351-4518 |

| Portugal | SOS Voz Amiga | www.sosvozamiga.org | 213 544 545 963 524 660 912 802 669 |

| Russia | Fund to Support Children in Difficult Life Situations | www.ya-parent.ru | 8-800-2000-122 |

| Singapore | Samaritans of Singapore | www.sos.org | 1-767 |

| South Africa | South African Depression and Anxiety Group | www. sadag.org sadag.org | 0800 567 567 |

| South Korea | Korea Suicide Prevention Center중앙자살예방센터 | www.spckorea.or | 1393 |

| Spain | Telefono de la Esperanza | www.telefonodelaesperanza.org | 717 003 717 |

| Switzerland | Die Dargebotene Hand | www.143.ch | 143 |

| Taiwan | 国际生命线台湾总会 [International Lifeline Taiwan Association] | www.life1995.org | 1995 |

| Ukraine | Lifeline Ukraine | lifelineukraine.com | 7333 |

| United Kingdom | Samaritans | www.samaritans.org/how-we-can-help | 116 123 |

| United States | 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline | 988lifeline. org org | 988 |

How can we improve it?

Ask the Help Community

Get answers from community expertsTransfers

home

Parents

Helpline

Information about the unified all-Russian children's helpline

In September 2010, in the Russian Federation, the Foundation for Support of Children in Difficult Life Situations, together with the constituent entities of the Russian Federation, introduced a unified all-Russian children's helpline number 8-800-2000-122 .

When calling this number in any locality of the Russian Federation from landline or mobile phones, children in difficult life situations, adolescents and their parents, other citizens can receive emergency psychological assistance, which is provided by specialists of services already operating in the constituent entities of the Russian Federation that provide services for telephone counseling and connected to a single all-Russian number of children's helpline.

Confidentiality and free of charge are the two main principles of the children's helpline. This means that every child and parent can anonymously and free of charge receive psychological assistance and the secrecy of his call to the helpline is guaranteed.

Working hours of the children's helpline in the constituent entities of the Russian Federation

(as of October 1, 2013)

| Name of the constituent entity of the Russian Federation | The operating mode of the children's helpline of trust | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Russian Federation | Total | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Central Federal District | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | Belgorod region | pon.pat.09.00-21.00 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Bryansk Region | pon.09.00-22.00 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 9ATH | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | Voronezh region | around the clock | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Ivanovo region | Mon-Fri 11. 00-20.00 6 903 00-20.00 6 903 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Southern Federal District | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 37 | Republic of Adygea | Clultwood | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 38 | Kalmykia | PON-PIT. 8.00-17.00 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 39 | Krasnodar Territory | 2 round-the-clock | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 40 | Astrakhan Region | AGROMOUSE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 41 039 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 82 | Jewish AO | pon.pat.09.00-18.00 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 83 | Chukotsky Autonomous Office | Pon.09.00-22.00, OXIS. 16.00-22.00 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

12.2016

12.2016