Storytelling as therapy

The power of story - Counseling Today

Write what you know.

This classic adage from creative writing class has launched many a novel. According to those who practice narrative therapy, it also can launch a counseling client into a transformative and healing process of self-reflection.

Narrative therapy refers to the work most often attributed to Michael White and David Epston. The approach emphasizes a person’s life stories and considers problems to be created out of different contexts, not as the result of who the person is. A well-worn maxim associated with narrative therapy is that “the person is not the problem, the problem is the problem.” Narrative therapy emphasizes clients’ strengths, helping them to tell the alternative personal stories that often get overshadowed by the more dominant stories about their problems. Using gentle questioning techniques, the counselor collaborates with the client to deconstruct stories and thoroughly investigate any problems together, as though they were reporters getting to the bottom of a lead.

This approach resonates deeply with Jane Ashley, a former newspaper editor and reporter who left journalism because she was disenchanted by the way that preconceived ideas often shaped how the media presented stories. “What I found in the first few years as a therapist was that the same way of listening and seeing clients was at work in the [process] of therapy,” she says. “So, I was starting to be a bit discouraged when I heard Michael White’s approach. What he had to say spoke directly to my concerns with journalism and the mainstream world of psychotherapy.”

Since discovering narrative therapy in 1995, Ashley, a licensed professional counselor (LPC) in Arlington, Va., has participated in dozens of related trainings, including a one-week intensive workshop with White. She also runs a narrative peer study group that incorporates mindfulness techniques. Ashley says it is the nonimpositional stance of the narrative therapist in particular that helps her avoid the pitfalls of preconceived notions.

“Narrative ideas inform my position in the conversation as a curious, nondirective collaborator in exploration of how the problem, or problems, have taken up more space in the lives of my clients,” Ashley says. “I try to stay curious and to keep my language and questions based on the language and expressions of the client. To me, this position is the most important aspect and hardest to learn for therapists.

“We are trained in all the other approaches to interpret and offer suggestions and interventions that come from the ‘expert’ knowledge of whatever theoretical orientation informs our interpretations. We are trained to speak from expert knowledge. In narrative work, the expertise is in listening for ‘sparkling moments’ and ‘exceptions to the problem’ in the words, attitudes and expressions of the client. It is very honoring of the lived experience and values and beliefs of the client.”

Ginny Graham, an American Counseling Association member who is one of Ashley’s counseling supervisees, agrees. “I love the accessibility of the genre,” she says. “The more I use the context of story to frame clinical discussions, the more I appreciate how its familiarity invites and grows content. Who doesn’t love a good story? By its very nature, story elevates and even celebrates conflict as the central vehicle for change.”

“I love the accessibility of the genre,” she says. “The more I use the context of story to frame clinical discussions, the more I appreciate how its familiarity invites and grows content. Who doesn’t love a good story? By its very nature, story elevates and even celebrates conflict as the central vehicle for change.”

Graham, an LPC with offices in Alexandria and Arlington, Va., came to counseling work after a career as a high school English teacher. She acknowledges that this background likely predisposed her to an appreciation of narrative therapy. “Using story as a gateway to greater meaning in life — a key component of this approach — is a given in any English classroom. A way I’d create relevancy for my English students was to talk about all literature as a kind of ongoing conversation that people have been having since the first word was spoken,” she notes. “Finding a therapeutic approach that says the most defining story of all is each person’s own unique story felt like a natural progression for me clinically. ”

”

Crediting her supervision work with Ashley as the spark that ignited her curiosity about narrative therapy, Graham says, “It probably sounds simplistic to explain the experience as one of being taken seriously. If that doesn’t happen in a clinical or supervision relationship, there’s something wrong, right? Yet there was something powerful about being on the receiving end of the questions she asked, as well as her encouragement to expand on and enrich the content.”

Graham also attended a workshop that Ashley led about using narrative techniques in group therapy. “After selecting witnesses to listen to a conversation between the practitioner and the client in which the client told a story, we were asked to do a few simple things: isolate a phrase or image that stuck with us and to talk about how it resonated, how we could relate it to our own story,” she explains. “After we shared our material, the client talked about how what we’d said had changed her original perceptions.

“The result was unanimous energy and enthusiasm for the creative way we had experienced each other and unwittingly grown in honing our own understanding of ourselves. … Experiencing it spoke volumes about the empowering possibilities inherent in this approach for doing group work. It was a living, breathing illustration of how stories overlap in a powerful way to inform, confirm, contradict, challenge and inspire.”

Tools for the narrative

Narrative therapy demands that counselors hone their listening skills. “I try to train myself to listen for wisps of dreams that are barely spoken — those hopeful thoughts that might be drowned out by the influences of the louder, more emphatic problem narrative,” Graham says. “What’s more, it’s not enough for me to hear it. I want to create a sense of collaboration. I want to be considerate and explicitly check out what I think I’m hearing with my client.

“In my collaborative, narrative mode, I might say something like, ‘It’s funny when you say that it seems like some of what you’ve said is barely written — as if it’s written with a light, thin pencil. Yet, as you talk, there’s something that has me thinking that you might want to swap that pencil for a permanent marker. Am I right? Or what am I hearing unfold here? Is this something you want to talk more about?’”

Yet, as you talk, there’s something that has me thinking that you might want to swap that pencil for a permanent marker. Am I right? Or what am I hearing unfold here? Is this something you want to talk more about?’”

Graham has found that the narrative approach is particularly helpful with clients who are facing adjustments related to loss and major life changes, as well as when multicultural issues come into play. “I love asking questions that invite [both myself and] folks to reflect on the relative strengths and weaknesses that exist in our social discourses,” she says. “For many, examining themselves objectively as a person in history becomes a first opportunity to think critically about culture, politics and the dominant stories that inform unconscious attitudes, hold us back and dictate behavior.

“For me, undoubtedly the most satisfying aspect of this approach is that the act of inviting and encouraging authorship automatically means there will be revisions because, as every writer of story comes to know, revising is where the real story emerges,” Graham adds. “The act of revising a story is such a positive, possible task and serves to lessen the sting and stress of the change process. Some clients have likened the approach to the pick-your-own-ending books they remember delightedly from their childhood.”

“The act of revising a story is such a positive, possible task and serves to lessen the sting and stress of the change process. Some clients have likened the approach to the pick-your-own-ending books they remember delightedly from their childhood.”

Sandy Davis, an ACA member and LPC in Fenton, Mo., was drawn to narrative therapy during her graduate program. “As students, we were challenged not to just be ‘eclectic’ but to find a mode of therapy that would fit us,” she says. “I began searching for a therapy that fit me rather than forcing myself into a mold. Narrative therapy utilizes my strengths, and I am consistently adding to my skill set by seeking educational opportunities on narrative therapy through journals, articles and continuing education.”

Davis uses narrative interventions to help clients separate themselves from their problems. “I am interested in the person’s self-talk, how they describe themselves, how a ‘problem’ begins using a small truth or situation and creates a challenge to the person’s concept of self. … Learning the ability to utilize externalizing language often allows [the client] to relax and begin building self-confidence,” she explains. “They are usually relieved that they are not identified as ‘the problem’ and welcome the opportunity to have someone to team up with to address and combat the problem.”

… Learning the ability to utilize externalizing language often allows [the client] to relax and begin building self-confidence,” she explains. “They are usually relieved that they are not identified as ‘the problem’ and welcome the opportunity to have someone to team up with to address and combat the problem.”

“Asking a person how depression keeps them from having fun forces them to develop more concrete reasons,” Davis continues. “They may reply that depression tells them they are not good enough, not skinny enough, not smart enough and that they do not have energy. This gives me insight into their thought process and how the problem manipulates the person.” Other narrative tools include letters, contracts, poetry, art and addressing cognitive distortions.When using narrative techniques, Davis says, counselors should know there is always more than one version of a story. “Mapping the problem and its effects on the person is an important first task,” she says. “We assist the person in [developing] a more complete story of exceptions for when they were able to defeat the problem. We ask questions like, ‘How does the problem talk you into your behavior?’ The person is then invited to take a position on the problem, to decide how it will affect the person from that point on.”

We ask questions like, ‘How does the problem talk you into your behavior?’ The person is then invited to take a position on the problem, to decide how it will affect the person from that point on.”

Davis’ first homework assignment to clients asks them to consider their own self-talk. “I ask the person to create two lists of adjectives that they see as truths about themselves. I am careful to state not to include what others say about them,” she says. “One list is to contain negative [adjectives] and the other, positive adjectives. They bring the list into the safety of the office, and we together try to find evidence that these words portray what is really true. I work with the person to find exceptions for the negative words.”

Davis adds that narrative work also offers flexibility, allowing her to use it in conjunction with other models, including solution-focused and cognitive behavioral techniques.

A career context

Many agree that narrative therapy, with its invitation to consider one’s life experiences as a set of rich stories that can build off one another, is particularly applicable to career development work. Lisa Severy is an ACA member who primarily works with traditionally aged college students as assistant vice chancellor of student affairs at the University of Colorado at Boulder. She applies narrative techniques in this capacity, especially as she helps students determine their next steps after graduation.

Lisa Severy is an ACA member who primarily works with traditionally aged college students as assistant vice chancellor of student affairs at the University of Colorado at Boulder. She applies narrative techniques in this capacity, especially as she helps students determine their next steps after graduation.

“I often ask students to think about their favorite book or movie. When they have one in mind, I ask them to describe it to me and to tell me what is happening at the plot level and what the underlying themes are,” she explains. “While many people describe the plot of the movie in similar ways, the underlying themes often vary [because] those are a reflection of the viewer as much as of the movie itself.

“In sharing that with students, I tell them that people seem to report being most happy and successful in their careers when the plot of their career story is closely aligned with their own life themes. Those people whom we see floating through their work lives with very little energy probably have a huge gap between what they are doing and who they are [their life themes]. Our goal, then, is to create the next chapter in the student’s story that carefully aligns plot and underlying theme. That description tends to help students understand the process and buy in to the idea.”

Our goal, then, is to create the next chapter in the student’s story that carefully aligns plot and underlying theme. That description tends to help students understand the process and buy in to the idea.”

Severy, the incoming president-elect of the National Career Development Association, a division of ACA, adds that narrative techniques are particularly refreshing in career development contexts. “Many career counseling models are norm-referenced. … They tend to assess a ton of people and then compare an individual to characteristics of the group. The norm, of course, doesn’t really exist, so comparing people to it can often lead to frustration — ‘Why does everyone else know what they want?’ What if there isn’t some ideal career choice hidden beneath the surface that just [needs to] be uncovered?

“Asking people to write the next chapter in their lives moves them away from the idea that they are writing their entire autobiography at 22 years old,” she says. “It also allows them to use their own words, culture and experience to create the story. I think of it as a reverse funnel. Older models are reductionist … taking the breadth and depth of a person and identifying certain traits — interests, skills, values, personality type — and reducing it down through a funnel process, the end result being something that could be compared to norms or to work settings.”

I think of it as a reverse funnel. Older models are reductionist … taking the breadth and depth of a person and identifying certain traits — interests, skills, values, personality type — and reducing it down through a funnel process, the end result being something that could be compared to norms or to work settings.”

“Narrative therapy is the opposite, helping people to create holistic, broad stories in context,” Severy continues. “Not only have I found it to be much more successful in helping students, it is also much more satisfying for me as a counselor.”

A worldview in practice

For treatment-wise clients — those who have been in and out of therapy throughout their lives — the narrative approach may feel strange at first. “It will just look like a rich conversation with a loving friend,” Ashley says. She finds the techniques work best with those who are “thinking and creative people. … In my view, this includes all people.”

Severy agrees: “Some clients are certainly more drawn to [narrative work] than others, but I use the principles to guide my practice either way. In college student career counseling, some students come in just wanting someone to give them an answer quickly … and this type of counseling requires a great deal of time and effort to do well. Those that put in the time and are naturally drawn to history, culture, stories, narratives, etc., find it very engaging.”

In college student career counseling, some students come in just wanting someone to give them an answer quickly … and this type of counseling requires a great deal of time and effort to do well. Those that put in the time and are naturally drawn to history, culture, stories, narratives, etc., find it very engaging.”

Ashley recommends that interested counselors seek training with those narrative therapists who regard this work as a “worldview” in practice. “It is not the techniques,” she says. “The techniques — externalizing the problem, deconstructing the story, etc.— are to support the position of curiosity, interest, imagination and respect for the client.” She cautions that “many people who are practicing what they call ‘narrative work’ are actually using the techniques to deliver their ‘expert’ knowledge that comes from the other therapeutic orientations.”

Similarly, Severy warns interested counselors against jumping to conclusions as the client’s story unfolds. “There is a danger within this model of trying to move too quickly, with theme identification becoming more of a diagnosis than an authorship: ‘Oh, you told me a story about getting a kitten when you were 5. You must want to be a veterinarian!’” she quips. “The co-creation model emphasizes that the counselor should continually check assumptions and conclusions with the client to avoid that trap. I like to think of the process as the client being the writer and the counselor a test audience or editor — not someone to judge, but to ask questions and help refine.”

You must want to be a veterinarian!’” she quips. “The co-creation model emphasizes that the counselor should continually check assumptions and conclusions with the client to avoid that trap. I like to think of the process as the client being the writer and the counselor a test audience or editor — not someone to judge, but to ask questions and help refine.”

Searching for optimistic vignettes is part of the narrative therapist’s task as well, Davis adds. “It is a wonderful way of assisting [clients] to see a more preferred story that has been lived rather than only the dominant story that includes the present problem. The challenge is to find out what is going right, to be optimistic in the face of some horrific stories [and] to see the strength in the one sitting before us.”

“We often serve a population that lives problem-saturated stories, and yet they survive with skills that they do not acknowledge,” she says. “Rewriting history can occur, and it can change the future of those we serve. As therapists, we must remember that some remnants of resiliency and hope are there, but that the dominant story is able to disguise them. Collaborating with a person to discover these other truths is a life-changing event.”

As therapists, we must remember that some remnants of resiliency and hope are there, but that the dominant story is able to disguise them. Collaborating with a person to discover these other truths is a life-changing event.”

Contributing writer Stacy Notaras Murphy is a licensed professional counselor and certified Imago relationship therapist practicing in Washington, D.C. To contact her, visit stacymurphyLPC.com.

Letters to the editor: [email protected]

Is Storytelling Therapy?. The fine line between narrative and… | by Jacqueline Ward

Photo by S O C I A L . C U T on UnsplashI’m a psychologist as well as a fiction writer. At a conference the other day someone asked me if I thought that a novel was an example of a psychological narrative and if it was therapeutic to the writer and/or the reader.

The word narrative, used in the context of describing language, is broad-based and therefore complex. The word is used in both literary terminology and in psychological language and although the dictionary definition is ‘a story or account of events, experiences, or the like, whether true or fictitious’ the word has different depths of meaning in these different contexts.

The key word here is ‘story’. The obvious use of narrative is the telling of a story, and in literature this has become popular terminology to describe the strands and structure of a story which is told via an author. This story can be an autobiography, a biography or fiction; all of these have a narrative. The main aim of this storytelling is for artistic value and/or to publish commercially.

On the surface the meaning of psychological narrative is the same, it means to tell a story. However, this is where the commonalities end, as psychological narrative has a different context than literary narrative in that the storytelling is a representation of the storyteller’s identity. In these terms, the psychological personal narrative with its multiple truths is a vehicle for a two-way communication with the world.

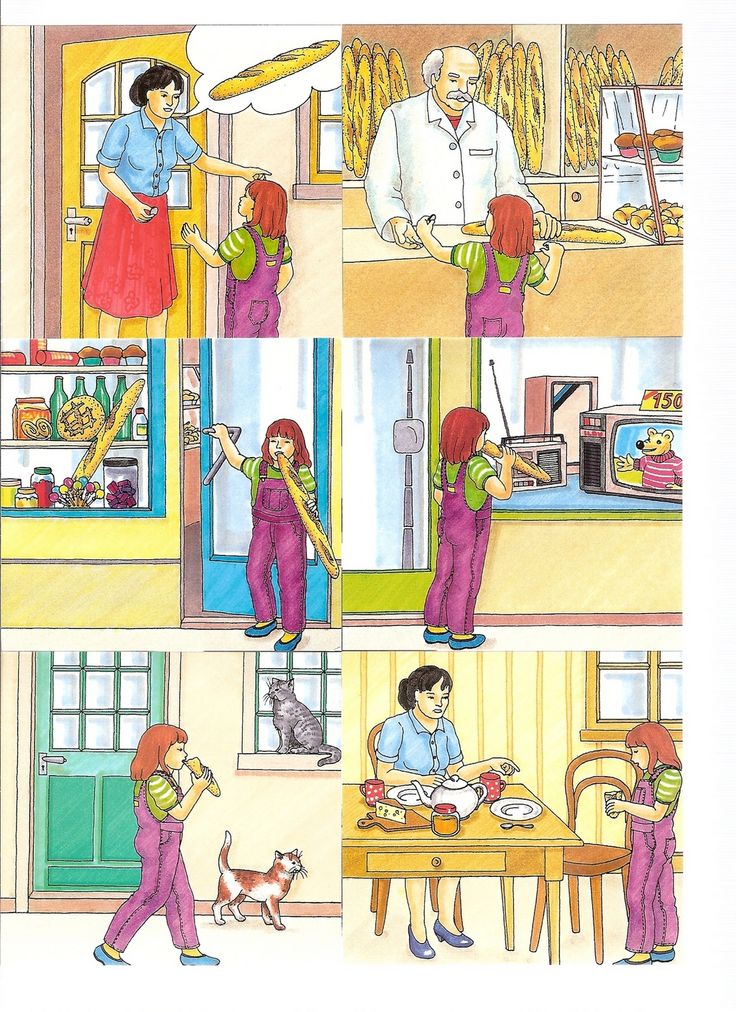

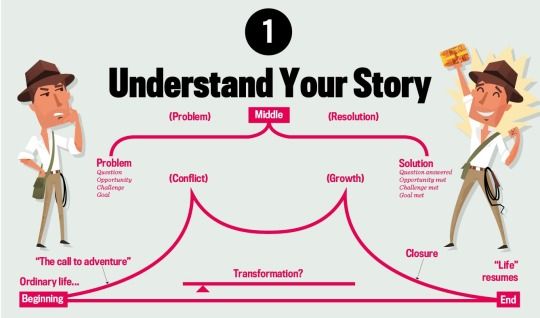

Psychologists use narrative psychology to understand how people relate to the world in the context of their own lives. Their stories may be told through many different mediums such as video, storyboards, poetry, music and of course conventional storytelling. Each story has a beginning, a middle and an ending, and has peaks and troughs; even so, it is based in the mundane normality of everyday life for most people, with the occasional peaks and troughs providing a heartbeat of crisis and joy in the context of feelings and emotions. This is fairly different from the literary narrative that often takes the form of mountains of joy and valleys of crisis joined together by very little normality, as this is what sells books, magazines, newspaper and TV media.

Each story has a beginning, a middle and an ending, and has peaks and troughs; even so, it is based in the mundane normality of everyday life for most people, with the occasional peaks and troughs providing a heartbeat of crisis and joy in the context of feelings and emotions. This is fairly different from the literary narrative that often takes the form of mountains of joy and valleys of crisis joined together by very little normality, as this is what sells books, magazines, newspaper and TV media.

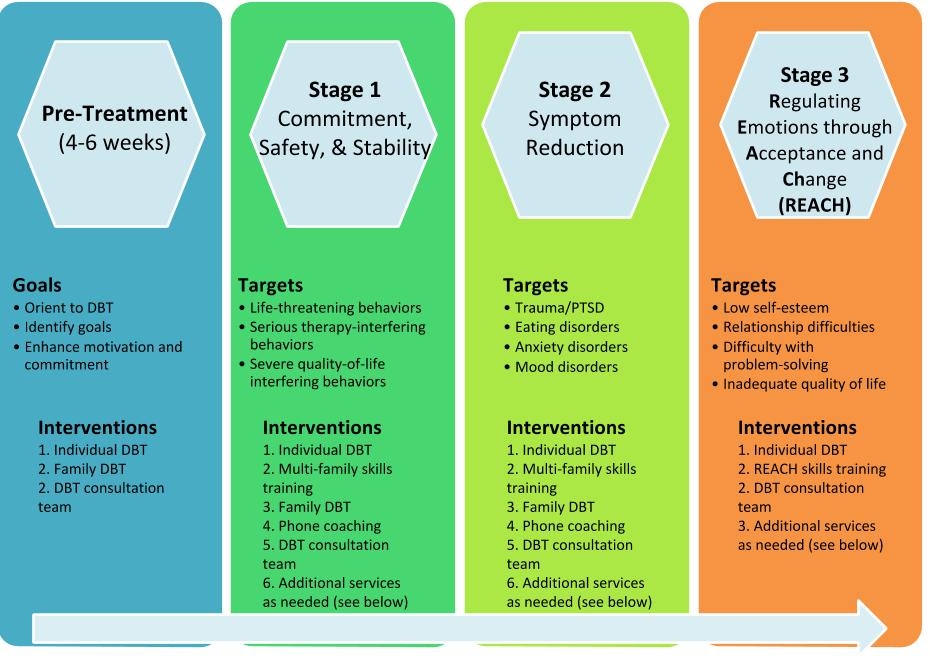

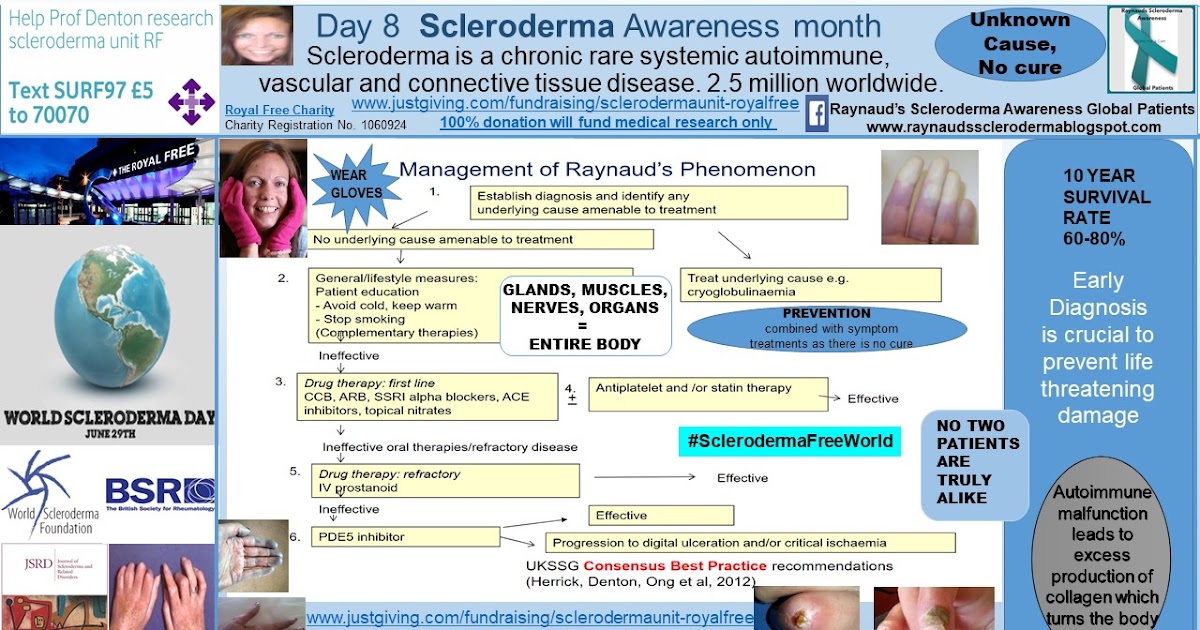

Narrative therapy is used to look at the identity story of a person, identify the crisis and the joy in their lives, understand how this has affected them, and reframe this positively. The underlying intention is to help the person come to terms with events in their lives that have left them perhaps uncertain and fearful about the future. The aim is to form an awareness of your continuing narrative and to form a deeper relationship with both the internal and external world.

In contrast, the literary narrative, whilst perhaps resonating with the life experiences of some people, is providing an alternative, often fantasy, narrative in which people can hide from their ‘selves’ and temporarily integrate, as a reader, with the writer’s imagination and creativity.

In some cases the relationship between the writers personal narrative and the literary narrative they create is strong, as in the autobiography. Even in fiction the personal narrative of the writer can be the basis of a novel. Possibly the main difference here is the audience; for a literary narrative it is the readership transaction and this is fixed at the narrative end of the communication. For the psychological narrative it is everyday life in the communication of identity, which is fluid and flexible at both ends of the communication, as demonstrated by the effectiveness of narrative therapy in reframing experience.

An example of attempts to merge the two kinds of narrative were climate change advertisement on national television, where the media illustrated reality through a fairytale. A child was shown reading a book of fairy tales which outlined the dire effects of climate change. Parents complained vigorously about this symbolism, and this is an example of the difference between what we expect from the ‘reality’ of everyday narratives and escapism of mediated narratives.

This advertisement is a story of a story of a story. The film uses visible human reactions to storytelling as the story unfolds a written and pictorial version of the story of climate change. The representation of generational knowledge is another story depicted to reinforce its power.

We may think that stories are confined to books, but advertising makes use of storytelling to use the shape of stories, as above, to influence us. Whether it is truth or fiction is irrelevant-it is the presentation of stories in a familiar pattern to both literary narrative and personal narratives that is powerful.

This advertisement also highlights the longevity and transference of storytelling. This is another important factor in the blurred line between literary narratives and psychological narratives. As children, nursery rhymes are used as metaphors for power relationship and good and bad. The much-maligned wicked stepmother in Cinderella has set a precedent for women in second marriages and step-parenting that has fuelled a plethora of stereotypes embedded in our psyche.

So, be it entertainment or therapy or a mixture of both, storytelling involves narratives and this is why the two often become confused. Ultimately, storytelling is storytelling, yet the difference between psychological and literary narratives, from meaning to mediation, stretches the boundaries of truths just that little bit further as we realise that both are ultimately works of fiction filtered through experience.

It’s the expectations of the story, the transmission media, the width and depth of the audience and where the story ends that differentiates. Literary narratives end on the last page yet have the capacity to preserve a story and cultural detail, whereas psychological narratives are circular stories, generational and enduring in memory, overarching culture and society.

Micro and macro? You decide.

Storytelling techniques: narrative and plot, without which there are no stories

Author Roman Skrupnik Reading 15 min. Views 7k. Posted by

Roman Skrupnik helps you understand the basics of creating stories. Why the right narratives determine the success of articles and what you need to know to tell compelling stories.

Why the right narratives determine the success of articles and what you need to know to tell compelling stories.

Contents

- No history, no reader

- Storitelling in marketing

- Storitelling in psychotherapy

- narrative: Instructions for understanding the event

- The narrative creates primarily

- The plot saves Longrid

- as a person writes personal history

- of the Narrativa system - the system

- Scaling: brand as history

- No history? Let's invent a legend

- So, what's the problem?

No history, no reader

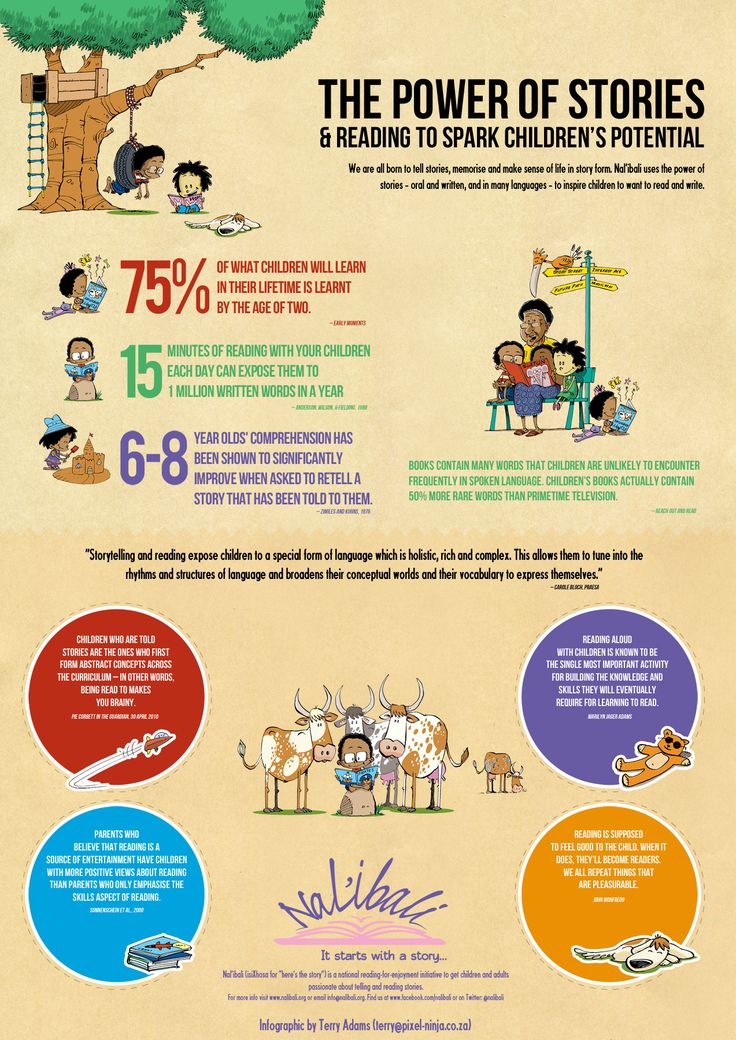

Digital media fight not for traffic, but for engagement: time on the site, scrolls and page transitions. Articles are read if they captivate the reader—if they have stories.

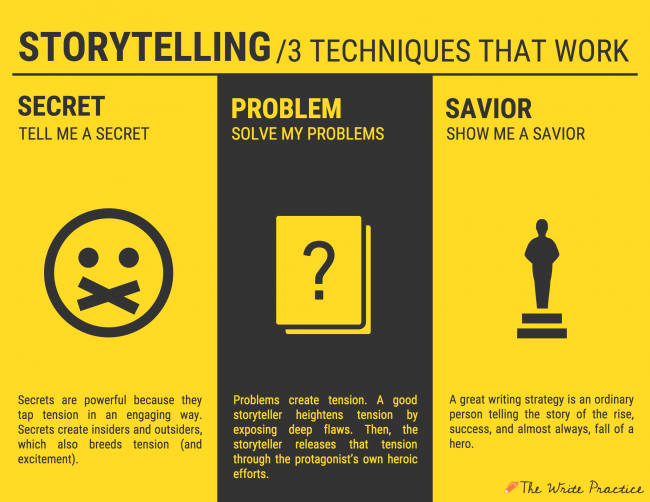

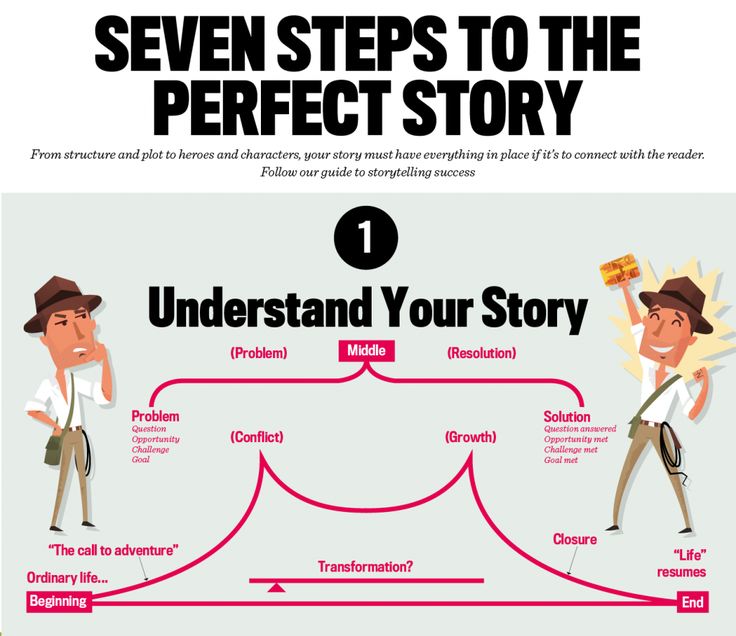

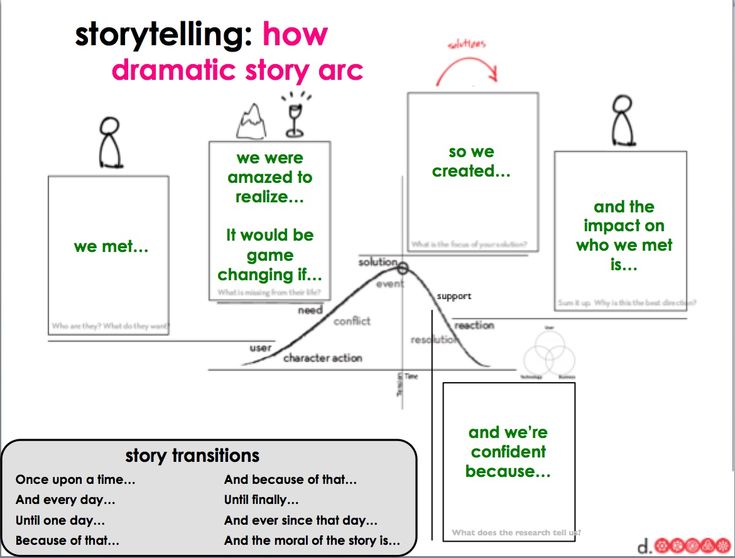

A story must have a plot: exposition, plot, development, denouement. Not bad if there is a prologue and an epilogue. And it must be based on a strong narrative.

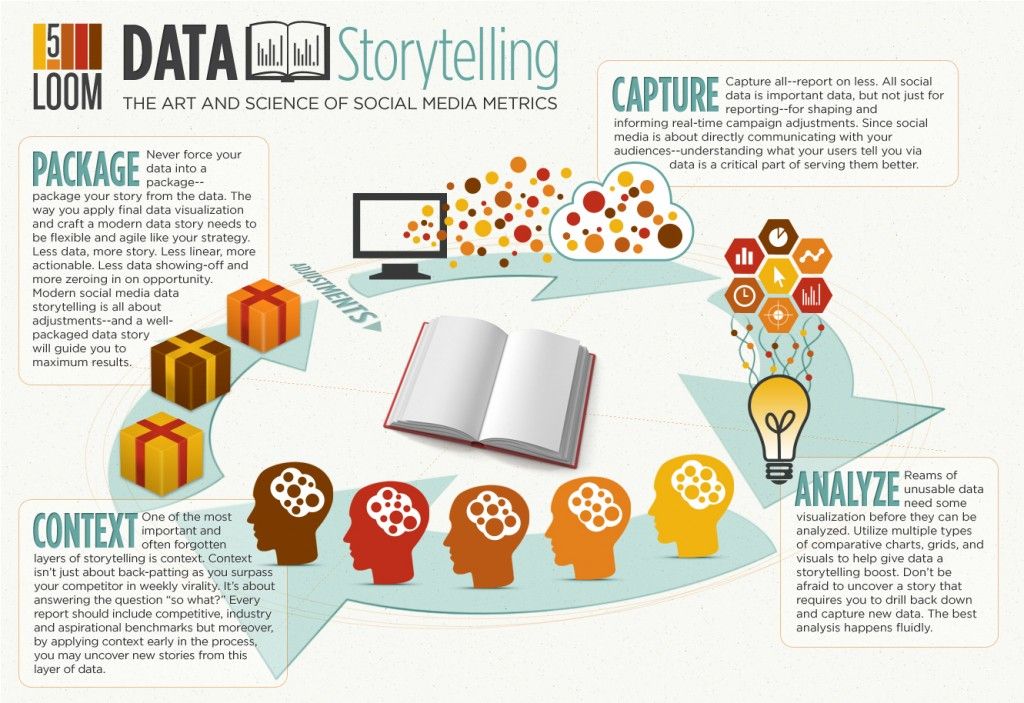

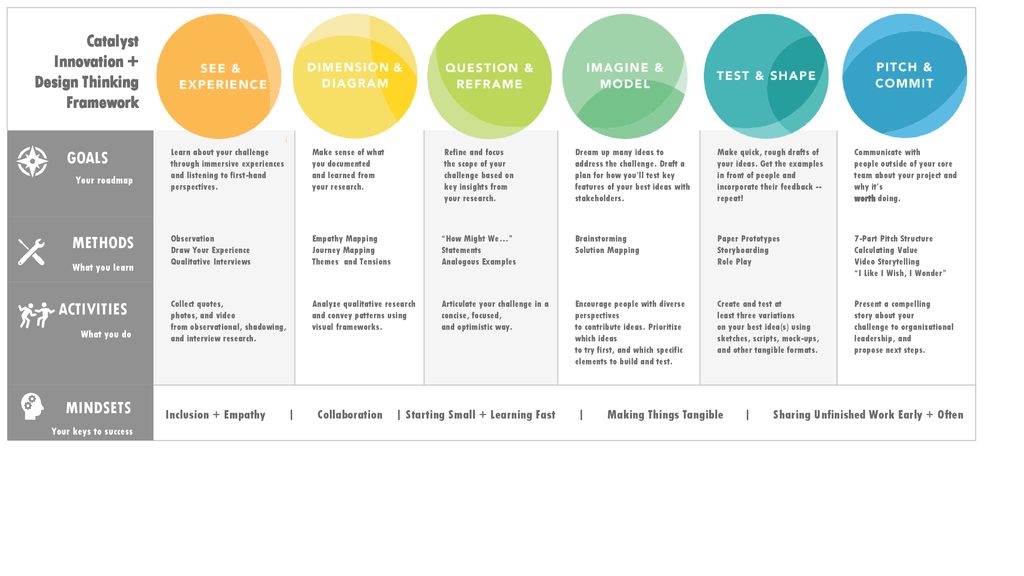

Storytelling in marketing

A set of methodologies forms a tool. At first a person thinks that he needs to take something heavy and hit - then a hammer appears. Methodologies improve, and tools follow. Not vice versa. nine0005

At first a person thinks that he needs to take something heavy and hit - then a hammer appears. Methodologies improve, and tools follow. Not vice versa. nine0005

Same with storytelling marketing. First, the marketer thinks about how to get the reader to finish reading the article. Then comes storytelling. The difficulty is that the concept of storytelling has been adopted by many, but the tools have not been studied, so they use it in vain.

The tools here are plot and narratives. You can't just say "tell stories!" — and expect the stories themselves to engage and inspire.

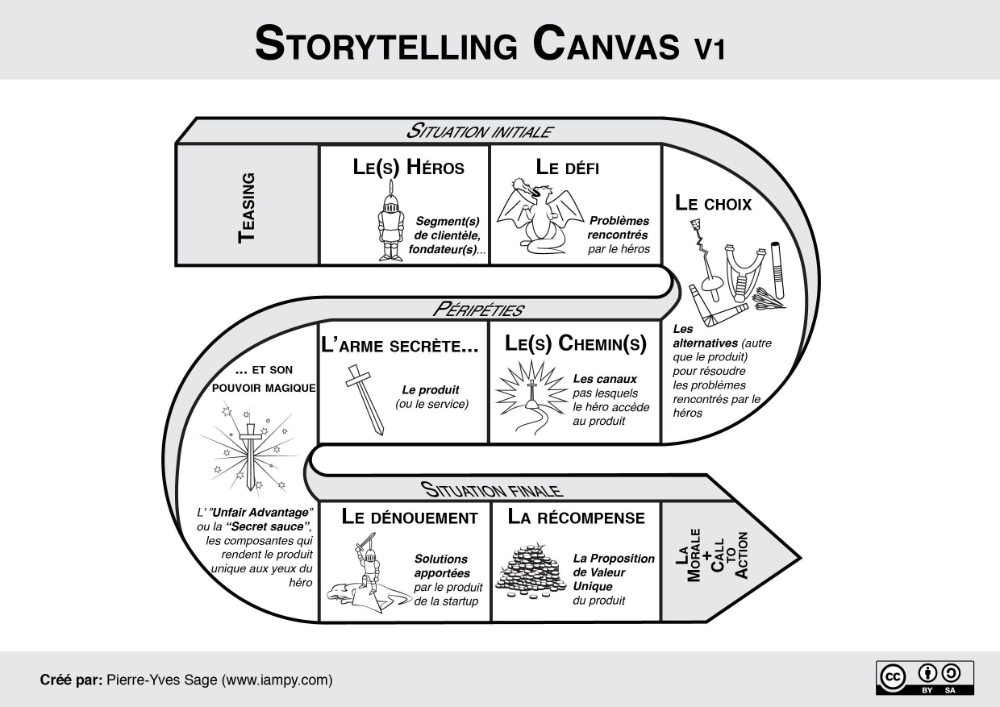

The story is based on a narrative: an instruction for understanding what is happening. Then the narrative is overgrown with a plot - a hero appears, the hero's path and all the participants in the story. Additional storylines are being built, it all twists into a vivid narrative. nine0005

Storytelling in psychotherapy

The concept of storytelling "stuck" to marketing quite recently, and before that it was mostly said in psychotherapy.

Storytelling is a way of conveying information and finding meaning through storytelling. It is used in psychotherapy and is called "narrative psychotherapy".

The goal of narrative therapy is to create space around the client for the development of alternative, preferred stories that will enable him to feel able to influence the course of his own life, become the direct author of his own story and embody it, attracting "their" people to increase the feeling of caring and support. nine0005

Narrative is used in psychology according to well-established methods - because a mistake can harm the patient. You can’t just sit in a chair, turn on a violent fantasy and leave the patient alone with the demons in his head.

Fortunately, boring articles do not drive one crazy, at worst they annoy. There is always a choice: do storytelling meaningfully or continue to do it with a “finger” at random. Increasingly, marketers are calling texts storytelling, using a blind fashion trend. nine0005

nine0005

This is not storytelling

- An article about bars where you can watch football.

- Google Analytics Manual. №

- Reflections on the meaning of being.

- This article.

In secret: even instructions can be built according to the rules of storytelling, if you lay the foundation for the narrative “the hero overcomes obstacles” and build the plot of the narrative – you will not just list menu items, but tell how the hero learns to solve certain tasks. nine0005

Narrative: instructions for understanding the event

Narrative as a concept of postmodern philosophy is too complicated for a small article. Therefore, we will take a more or less popular interpretation.

D. Schiffrin defines narrative as “a form of discourse through which we reconstruct and represent past experience for ourselves and for others” [Schiffrin 2006: 321].

“Narratives play the role of lenses through which the independent elements of existence are seen as connected parts of the whole. They set the parameters of the everyday and determine the rules and ways of identifying objects that are to be included in the discursive space” (Rosenfeld 2006). nine0005

They set the parameters of the everyday and determine the rules and ways of identifying objects that are to be included in the discursive space” (Rosenfeld 2006). nine0005

“The idea of the subjective introduction of meaning through the task of the final is taken as the fundamental idea of narrativism” (Wikipedia).

Psychologists J. Brockmeyer and R. Harre in their study of narratives say that a narrative is not a description of a certain reality, it is an instruction for understanding reality.

Is it difficult? Yes there is a bit. Now let's get on the fingers.

Narrative is a subjective narrative that tells how to comprehend what happened. nine0108 In fact, the story of events replaces the event itself. For example, the same war, described by the winners and the vanquished, looks different. Each description is based on its own narrative - the narrator creates a certain model of the world in which the event takes place. In this way, the narrator essentially tells the listeners what to think about this event.

In this way, the narrator essentially tells the listeners what to think about this event.

A story becomes a story when the ending is known. In this way the narrator (narrator) differs from the hero and the listener. If the hero acts without knowing how everything will end - and this is the strength of the story, then the narrator knows the ending in advance and builds his hero's path to it. The joy of the listener is to see how all the plot knots will be untied in the finale. nine0005

The ending is set by one or another narrative.

- We have been training for a long time, we have developed excellent teamwork, and fourth place in the championship is a success for the team. Now we can get higher.

- The team is young, the coach is inexperienced, they spent all the time on basic training, it is not surprising that they only got to fourth place out of 5 teams. The coach needs to change.

These are two stories about the same team in the same championship. As you can see, the ending changes the story itself. nine0005

As you can see, the ending changes the story itself. nine0005

Narrative is created first of all

Let's take a coffee advertisement. It relies on a simple narrative in general.

The clumsy hero seeks the attention of the "princess" while she is committed to the hero without flaws. A magical elixir makes an awkward hero more attractive.

At the same time, the plot is based on the charm of the "face" of the brand - George Clooney and the adventures of the hero of the story - no less charming Jack Black. The narrative essentially "sticks together" the charm of Clooney and the idea of the magical quality of the drink. nine0005

If you watch the other videos in this series (such as the one with Danny DeVito), you will see that the basis of the advertising campaign - the narrative that is used to write the story - allows you to build consistently inspiring stories with different characters.

Plot Saves Longread

Snowfall: The Avalanche at Tunnel Creek Publication Series.

This story was published by The New York Times in 2012, from that moment "to make a snowfall" is said when they decide to make a similar page. nine0005

Even if we remove the visual effects and leave only the text, we will see a classic storytelling with an engaging plot and drama. Formatting is important, but it won't save an article with boring content. There is a strong story and a catchy interactive binding.

It is the plot of the story that leads the reader from one block to another; without an internal connection, the long read simply falls apart.

And if by plot you mean something like a plot/middle/denouement, then you are greatly mistaken. The plot is built according to a rigid plan. The plot plunges into the context of the story, then a certain event-catalyst occurs that pushes the hero on the path, along the way the plot unfolds completely several times - and this is what keeps the reader in suspense, then the climax happens, and by the end the reader must empathize with the hero so much that my heart beat faster when I read the last lines. nine0005

nine0005

Snowfall cover

Snow Fall combines a strong story with a rich visual tie-in that grabs the reader's attention in an information-saturated environment.

From the book How New Media Changed Journalism:

Media consumption is such that there are always distractions. The author of a multimedia story must understand that the user is rarely completely immersed in the story, and therefore correctly place the accents, select adequate multimedia formats and find a balance between the story and the reader. This puts forward increased requirements for the structure of the material, it must hold the reader's attention. Passion for a story is the product of its parts divided by the number of stories in the user's focus. nine0005

If the user has ten stories in the active area of attention, on which his eyes jump, then immersion in a particular story will be minimal. This formula also explains the requirement for the fullness of the meaning of each element of the multimedia material. If any of them carries a zero meaning, then the entire product in the numerator will be reset to zero. Leave in the story only those elements that work to achieve the goal.

If any of them carries a zero meaning, then the entire product in the numerator will be reset to zero. Leave in the story only those elements that work to achieve the goal.

The author can only propose hypotheses and think through scenarios through which he will lead the user. This path must be clean, free and clear. You should not get carried away with details, fill the space of history with information modules and elements just because “we can make infographics”. nine0005

Pay more attention to the character, the structure of the story, the plot, what will happen in the foreground and background of the story. Pay attention to the logic of the narrative and the emotional component more than how fully you have used all the multimedia formats available to you.

Snowfall also shows how the story is scaled - stretched over a series of publications. This is one of the nuances of the work of a journalist. If you are involved in media, for example, you are engaged in content marketing, it will be useful to know. nine0005

nine0005

Editor and TV presenter Timur Olevsky told UCU students that Western journalists are looking for a story that they can tell throughout their careers. And such a story can make a name for a journalist. A story that develops in real time and remains interesting until the end.

At the same time, no matter how "boring" the story may be in reality, it must be told in an engaging way. And this can become a social mission of a journalist - an interesting story will draw more attention to problems, for example, refugees. nine0005

The task of the author is to make the text read to the end. The text is read exactly as long as it is interesting.

And the most interesting story is our life.

How a person writes a personal story

We have gone through the heights of storytelling, now we will understand the nature of narratives and understand why we cannot live without stories.

From childhood, we form a picture of the world through the description of objects and events - narratives. If we did not know how, the world would be a complete hallucination for us, and we would remain in infancy. nine0005

If we did not know how, the world would be a complete hallucination for us, and we would remain in infancy. nine0005

How do we know this? Scientists modeled infant behavior.

From a study by neurophysiologists on the effects of LSD on the brain (2016)

The desynchronization of the DMN neurons correlated with the subjective assessments of the subjects who reported "dissolution of personality", "loss of "I"" (Self Dissolution).

The complication of the neural networks of the brain, the strengthening of the specialization of its areas and the strengthening of the connections between them occur as they grow older and mature. Therefore, the activity of the human brain under LSD is compared by the authors with the work of the brain of an infant. nine0005

“Loss of “I”” is the state of a person before he begins to describe the objects and phenomena surrounding him, that is, infancy. Over time, the child begins to describe the world around him through interaction with it: he pushes a vase, grabs his mother’s hand, shouts at the dog. From that moment on, self-awareness is born, and the brain remembers what is happening.

From that moment on, self-awareness is born, and the brain remembers what is happening.

The cat is not to blame

We built our world through descriptions - narratives, so the most convenient way for us to perceive new information is with their help. nine0005

For example, the Soviet folklorist Vladimir Propp tried to formulate the basic structure of a fairy tale narrative. He proposed to divide the narrative into smaller units - narratems: characters, character functions, magic tools or certain situations. For example, the narrateme “the hero meets a magical helper” can be found both in the Russian folk tale about Ivan Tsarevich and the Gray Wolf, and in The Hobbit, where the mysterious werewolf Beorn comes to the aid of Bilbo and his friends.

Fairy-tale narratives and other stories that are told to babies gradually build a picture of the world in which they will live. And they teach to live correctly (from the point of view of the society in which they are to enter).

We can rethink, change or create a new narrative system at any age. Thus, the birth of a child forces parents to rethink and create new narrative connections.

Researchers conducted a clinical study AAI (Adult Attachment Interview) to assess the "connectivity" of the parents' narrative. So neuroscientists have found that after parents comprehend how their past affects the present, they are able to establish stable, reliable and safe relationships with children and other people. nine0005

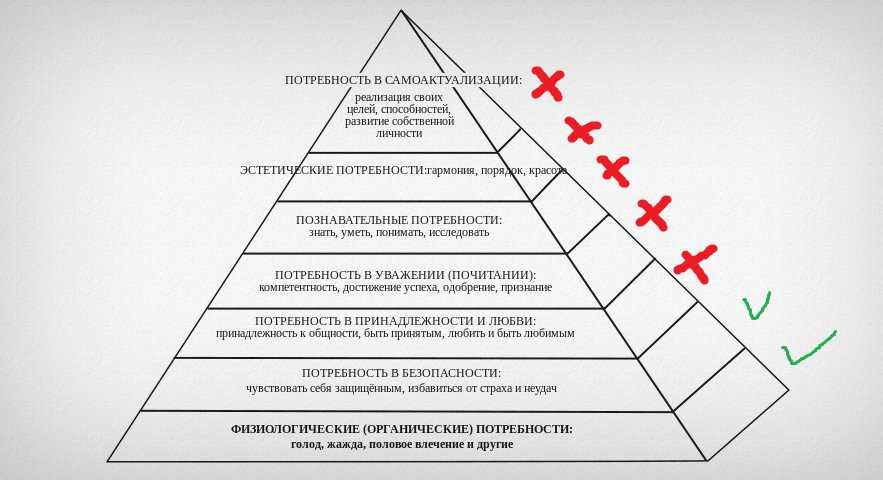

Our picture of the world is a system of narratives

“Each of us lives in a narrative, and this narrative is what we are,” said the famous neurologist Oliver Sachs. A person perceives his life as a plot, and the memory of a person corrects this plot.

I wouldn't argue with him.

Close people form similar narratives, and if previously unfamiliar people find that their outlook on life is the same, they get closer. Hence the stereotypes, and the peoples' perception of their place in the history of mankind, and the closeness of the adherents of a particular brand. nine0005

nine0005

Narrative is an instrument of influence

Groups of people have common views and judgments. So, the people unite people not only on a national or geographical basis, but also on their views on current events and the history of the state.

Each nation exists within its own system of narratives, which forms stereotypes and a sense of its place in the history of mankind.

For example, let's invent the simplest system of two narratives: "Orthodox = Russians" and "Russian does not criticize the Soviet army." Within the framework of such a paradigm, a Protestant, a gay, a historian with an alternative view of the events of World War II are not Russians. I took Orthodoxy, Russians and the Soviet army that are understandable to us in order to simplify the logical chain as much as possible and demonstrate the power of influence of narratives. nine0005

It does not matter to the system whether the narratives correspond to the truth, because they form an assessment (way of perception) of reality through the interpretation of events and phenomena. There is no objective reality in history. Any event is interpreted by a person, so the whole story is a system of narratives that are acceptable to a group of people at a given moment. Narrative can turn truth into lies and lies into truth. If you change the key narrative or a set of narratives within the system, a group of people will change their views on events and their place in history. This is what happens when history books are rewritten or films are made with an alternative view of the events of the past. nine0005

There is no objective reality in history. Any event is interpreted by a person, so the whole story is a system of narratives that are acceptable to a group of people at a given moment. Narrative can turn truth into lies and lies into truth. If you change the key narrative or a set of narratives within the system, a group of people will change their views on events and their place in history. This is what happens when history books are rewritten or films are made with an alternative view of the events of the past. nine0005

Compare states and peoples with brands and consumers. Brands write their story and instill in consumers a value system that is different from their closest competitors. When a consumer accepts a brand's narrative system, they become loyal. Companies will not mind if each representative of the target audience becomes a brand advocate - a brand patriot.

One of the narrative techniques is the image of the enemy. Pay attention to how well-known brands use it. For example, the argument about which is better - Pepsi-Cola or Coca-Cola, iPhone or Samsung - has long turned into a big story that is interesting to watch. On the other hand, a brand that is not involved in the confrontation can ridicule the leaders and rebuild from the “fuss”, as Microsoft does:

For example, the argument about which is better - Pepsi-Cola or Coca-Cola, iPhone or Samsung - has long turned into a big story that is interesting to watch. On the other hand, a brand that is not involved in the confrontation can ridicule the leaders and rebuild from the “fuss”, as Microsoft does:

Scaling: a brand as a story

Storytelling is scalable: from one article to a brand's lifetime.

Consciously or not, each brand forms around itself a system of narratives that influences people's opinion about it.

Narratives are formed into a system, although they do not always strengthen this system, contradictory narratives can undermine it.

Imagine a conditional marketing agency with a positive image:

- they organize useful events;

- their employees are strong speakers;

- they answer calls quickly;

- they publish useful articles.

Here is the whole picture.

And now the notional bank with conflicting narratives:

- this is a reliable bank;

- they have a hot-tempered manager;

- they are technological;

- their owner calls marketers names;

- they have strong marketing. nine0012

The picture is shaky, but there is a main character here, not idealized, as in modern films. And it also works for the brand. A strong narrative can "crush" all others.

It's good when the quality of the product outweighs risky narratives.

Brands write their story and tell it to consumers. This is how we come to storytelling beyond a single article, storytelling is a tool that a brand can consciously manage throughout its history.

The mission of a brand is to tell a coherent story, to develop the story throughout its existence, and to immerse consumers in this story.

No history? Let's invent a legend

If the brand is young or its appearance is only in the plans, a brand legend is created for its launch according to literary canons.

In 2007, I got a job in a shoe store and received a pack of materials to study. One section described brand stories. For example, like this:

“... somewhere in the very beginning of the 90s of the twentieth century, an interesting young girl appeared in the London district of Chelsea. She can often be seen in the most popular institutions of the English capital, at art exhibitions, poetry evenings and just at bohemian parties ... only very few people know that the girl's name is Helen Braska. She is a designer and she has a dream - light and elegant. She wants to come up with the best shoes in the world ... So, or something like this, one of the most progressive shoe brands called BRASKA was born. nine0050

The trademark is registered in England, the owner is a Ukrainian company, manufactured in China and India.

And here is the legend of the Zibert brand from Obolon:

At the beginning of the 20th century, namely in 1906, the construction of a brewery began in Fastov. The founders of the brewery were the tradesman Julius Siebert and the Prussian citizen Herman Saalman. The beautiful bank of the Unava River in Zarechye, next to the Church of the Intercession of the Virgin, was chosen as a place for the plant. German masters very quickly organized the work of the brewery, and already on December 24 they began to produce the first fast beer. nine0050

The founders of the brewery were the tradesman Julius Siebert and the Prussian citizen Herman Saalman. The beautiful bank of the Unava River in Zarechye, next to the Church of the Intercession of the Virgin, was chosen as a place for the plant. German masters very quickly organized the work of the brewery, and already on December 24 they began to produce the first fast beer. nine0050

The brewery did not stop its work even during the military actions that took place in history. Neither the First, nor the Second World Wars, nor the revolution became an obstacle for the Fastov brewers.

Not Masha, but GrettaPositioned as a German beer at an affordable price. A vivid story with narratives about German beer.

It's easier to enter the market when there is a story. No history, no brand. And strong stories are written on the basis of strong narratives.

So, what's the problem? nine0037

No problem.

Professionals will learn the basics of the fundamentals and hone tool techniques from the point of view. First the goal, then the tool.

First the goal, then the tool.

Mediocre marketers - rush after trends, calling anything as storytelling if it gives hope for sales. They will take the tool, and only then they will think how to apply it.

I hope that the concept of "storytelling" will fall into my field of vision as rarely as possible. And fascinating stories as often as possible. nine0005

The narrative turns out to be the tool that, being in the shadows, determines the perception of information. It is useful for an ordinary person to understand his nature in order to at least not fall for the tricks of deceivers. And marketers and commercial writers will finally talk about products in an interesting way.

Don't ask Google how to do storytelling. Take an interest in how to write stories, build plots, use narratives, and you will discover the knowledge accumulated over hundreds of years of literary development. nine0005

Subscribe to the newsletter. No spam!

Email *

Provided by SendPulse

NeoCode Institute - New NLP Code

personal tools

Content

- Storytelling

-

-

Good story criteria (suggested by Larry Prusak):

-

Sticky story criteria:

-

-

Storytelling: ideas, principles, tips

-

-

Storytelling training format used in the Lab:

-

-

Feedback format:

-

-

Stories told in the Lab:

-

Links to discussion of storytelling in the lab:

-

Related links

-

"By changing the stories we tell, we change our lives. " — Mike Turner

" — Mike Turner

Storytelling is a way of conveying information and finding meaning through storytelling. It is used both in psychotherapy, which is called "narrative psychotherapy", and in public speaking and management, where it is usually called "organizational storytelling".

Also on this topic, see the Narrative Practice section.

Good story criteria (proposed by Larry Prusak):

-

Persistence - the persistence of a story to retain its key messages through multiple retellings.

-

Remarkability (bulge) - the ability of a story to stand out, create an emotional difference, have an emotional charge. Humor, motivation for action, elegance of the proposed solutions are named among the things that create "bulge".

-

Meaningfulness - explanatory power, persuasiveness, correspondence to the observed facts in essential parts.

nine0404

nine0404 -

**Congruence** to the narrator - the narrator's comfort level in telling the story.

Sticky story criteria:

These six principles for good stories and ideas are suggested by the Heath brothers in Made to Stick. Why some ideas survive and others die. By a good story, they mean a "sticky" story (sticky in English), that is, tenacious, easily disseminated. History should be:

-

Simple

-

Unexpected

-

Specific

-

Realistic

-

Emotional

-

Good story

Note that in English this list is easier to remember:

-

S imple

-

U nexpected

-

C oncrete

-

C redible

-

E motional

-

S tory

Learn more about these principles (article in English).

Storytelling: ideas, principles, tips

-

Better Beginnings: how to start a presentation, book, article

-

Stories in position three versus stories in position one article from the NY Times.

-

Themes for stories as a way to rethink the situation. nine0005

-

Article from the Headhunter magazine "How to learn to tell stories" (based on training by M. Kukushkin)

-

Storytelling exercises (in English)

-

Telling stories well is an important foundation for being able to write them down (see writing)

-

We tell stories (tales, parables, fairy tales) for 3-10 minutes.

-

Best of all - from my own experience, about achieving some result. But you can also strangers, from any person. In general, the criterion for a good story is if someone can retell it. nine0404

-

At the beginning of the story it is useful to say a few words about her, why you personally like her.

-

The story should be transformative, that is, it should start the process of change in the listeners. You don't have to tell us right away what changes you are talking about, but if such a question arises, you should be ready to answer it.

-

If no one minds, the same stories can be told several times.

-

Any story ends with applause and feedback in a circle.

Feedback format:

Answer the questions:

-

What was good?

-

May I retell this story?

-

Do I want to retell, in the sense of “Is this story close to me?”

-

Was there a transformational component? Has something changed inside from listening and if so, what exactly? nine0005

-

What can be added and how exactly?

It is also important that the story is really transformational . Here are the questions we formulated for the narrator himself:

-

What happens to me when I remember a story?

-

What happens to me when I tell it?

-

How does my story change as I tell it?

-

What does it change for the listener (and does it change?)

-

How do I change?

Stories told in the Lab:

-

Hamster story

-

Photocopier story

Links to storytelling lab discussions:

-

Storytelling experiences

-

What's new in storytelling?

nine0012 -

Why are we doing this?

-

Storytelling and work

Other related links

-

http://www.