Social interaction with autism

Social Skills and Autism | Autism Speaks

Many children and adults on the autism spectrum need help in learning how to act in different types of social situations. They often have the desire to interact with others, but may not know how to engage friends or may be overwhelmed by the idea of new experiences.

Building up social skills with practice can help enhance participation in the community and support outcomes like happiness and friendships. We have compiled social skills tips and information from experts, teachers, and families, along with useful tools to help enhance opportunities to be part of the community.

What Are Social Skills?

Social skills are the rules, customs, and abilities that guide our interactions with other people and the world around us. In general, people tend to “pick up” social skills in the same way they learn language skills: naturally and easily. Over time they build a social “map” of how to in act in situations and with others.

For people with autism it can be harder to learn and build up these skills, forcing them to guess what the social "map" should look like.

Social skills development for people with autism involves:

- Direct or explicit instruction and "teachable moments" with practice in realistic settings

- Focus on timing and attention

- Support for enhancing communication and sensory integration

- Learning behaviors that predict important social outcomes like friendship and happiness

- A way to build up cognitive and language skills

Who Can Teach Social Skills?

There are many social skills to learn, so many different people will teach them in different settings - at home, school, and in the community. A special education teacher, speech pathologist, or other clinician may lead a “social skills group” that combines direct, explicit instruction with opportunities to practice and generalize these skills in more natural environments. This means real life practice with peers! Other professionals that support social skills include:

- occupational therapists

- behavioral therapists

- school psychologists

- general education teachers

- health and PE teachers

- many other direct care staff

Social Skills Groups

Social skills groups offer an opportunity for people with autism of all ages to practice their social skills with each other and/or typical peers on a regular basis. Many groups follow commercially available social skills curricula. A review of five studies on social skills groups by researchers at the University of Utah and the U.C. Davis MIND Institute helped identify what makes an effective social skills group.

Many groups follow commercially available social skills curricula. A review of five studies on social skills groups by researchers at the University of Utah and the U.C. Davis MIND Institute helped identify what makes an effective social skills group.

Effective Social Skills groups should*:

- Provide structure and predictability

- Break down abstract social concepts into concrete actions

- Simplify language and group children by language level

- Work in pairs or groups with cooperation and partnership encouraged

- Provide multiple and varied learning opportunities

- Foster self-awareness and self-esteem

- Provide opportunities for practice so that skills are used beyond the group in real life settings

*Excerpted from Social Skills Interventions: Getting to the Core of Autism developed for the Interactive Autism Network (IAN) by Teresa j. Fodden and Connie Anderson, Ph.D.

A Promising Model

The PEERS program at UCLA, which stands for Program for the Education and Enrichment of Relational Skills, is a 16 week-long program that teaches social skills, including tips on dating. Read more about the program:

- Social skills classes produce lasting benefits for adults with autism

- This program is teaching social skills to young adults with autism

Tips from Our Community

We asked Autism Speaks families for tips and ideas on social skill building. One mom shared,

My son plays social therapy games at a local social skill group where they let him practice with his peers. He has a chance to ask 'why' certain social skills are important in a safe and supportive space.

Read more social skills improvement ideas from our community here.

Search our Directory to find Social Skills programs in your community.

Using Personalized Teaching Stories

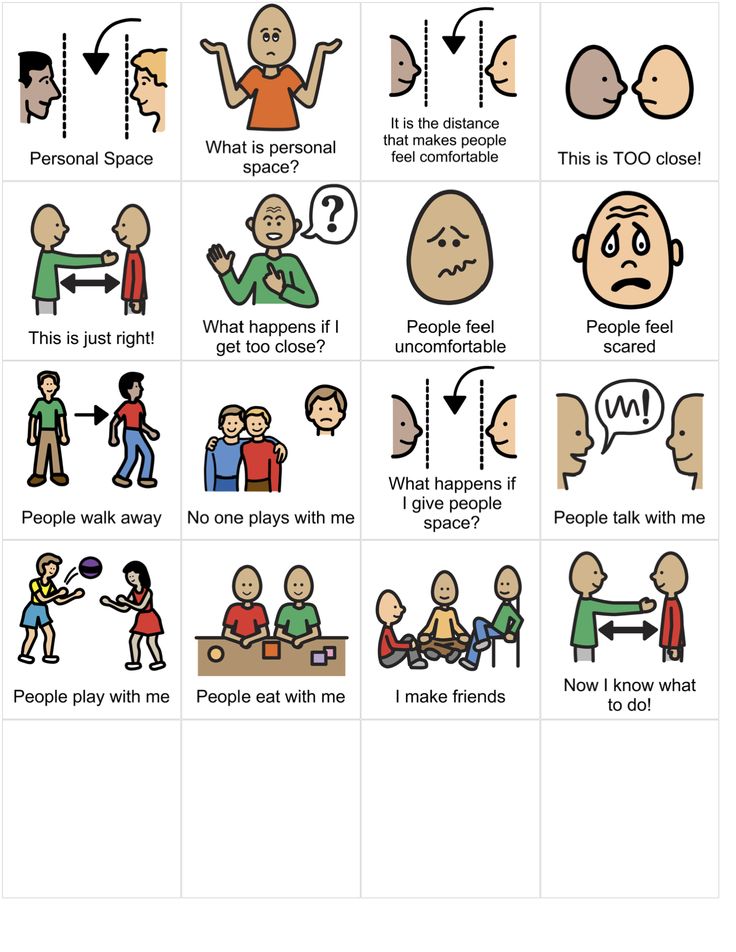

People with autism benefit from having information presented visually, such as a chart, a booklet, or an electronic device. Using personalized teaching stories provides a visual aid for people with autism to know what to expect in different situations and to learn what is expected of them in these situations.

Using personalized teaching stories provides a visual aid for people with autism to know what to expect in different situations and to learn what is expected of them in these situations.

Through pictures and simple language, these stories can make everyday social situations more predictable for people with autism, as well as giving them strategies for navigating these situations more effectively.

Autism Speaks partnered with the University of Washington READI Lab and Microsoft Office to provide this series of personalized templates for parents and therapists to customize to explain social situations to people with autism.

Personalize the templates with your own photos to explain what to expect and how to act in a variety of everyday situations. Personalized Stories:

- Going to a Restaurant

Help your child know what to expect when they go to a restaurant. - Going to the Store

Help explain what to expect when your family goes to the store to your child.

- Handling Bullying

Help explain how to handle bullying to your child. - Play Date

Help explain what to expect on a play date to your child. - Potty Training

Help explain how to use the potty to your child. - Taking Turns

Help explain the process of taking turns to your child.

Open the Doors to Your Community

Participation in the community can be enhanced through improvement in the social skills of people with autism.

-

Use our Directory to search for programs to practice social skills in your community.

-

Our Leading the Way: Autism-Friendly Youth Organizations guide can help community organizations make their programs more inclusive of children and young adults with autism.

-

Strategies for Supporting Social Skill Development for teachers

-

Nine Ways I Helped Foster Friendships for My Son with Autism

- Build Social Skills with 10 Inclusion Tips for Sports and Recreation

Autism: Impairments in Social Interaction

You are here:

Home / About Autism / About Autism Spectrum Disorder / Autism: Impairments in Social Interaction

Interactive Autism Network at Kennedy Krieger Institute

Date Last Revised:

December 5, 2013

Date Published:

April 2, 2007

The most striking feature of autism is social disconnection. People with autism may appear neither to be interested in nor able to “read” the social world. It is as though they are blind to the boisterous, complicated, emotionally loaded give-and-take of human interaction. Writing of one of the boys in his study, Kanner stated:

People with autism may appear neither to be interested in nor able to “read” the social world. It is as though they are blind to the boisterous, complicated, emotionally loaded give-and-take of human interaction. Writing of one of the boys in his study, Kanner stated:

“He paid no attention to the persons around him. When taken into a room, he completely disregarded the people and instantly went for objects, preferably those that could be spun. Commands or actions that could not possibly be disregarded were resented as unwelcome intrusions. But he was never angry at the interfering person. He angrily shoved away the hand that was in his way or the foot that stepped on one of his blocks…”1

The boy in Kanner’s study pushed away interfering body parts without seeming to understand that they were attached to a whole person – a person with his own intentions and desires. They were just objects that happened to be in the way. This is very typical of autism.

This is very typical of autism.

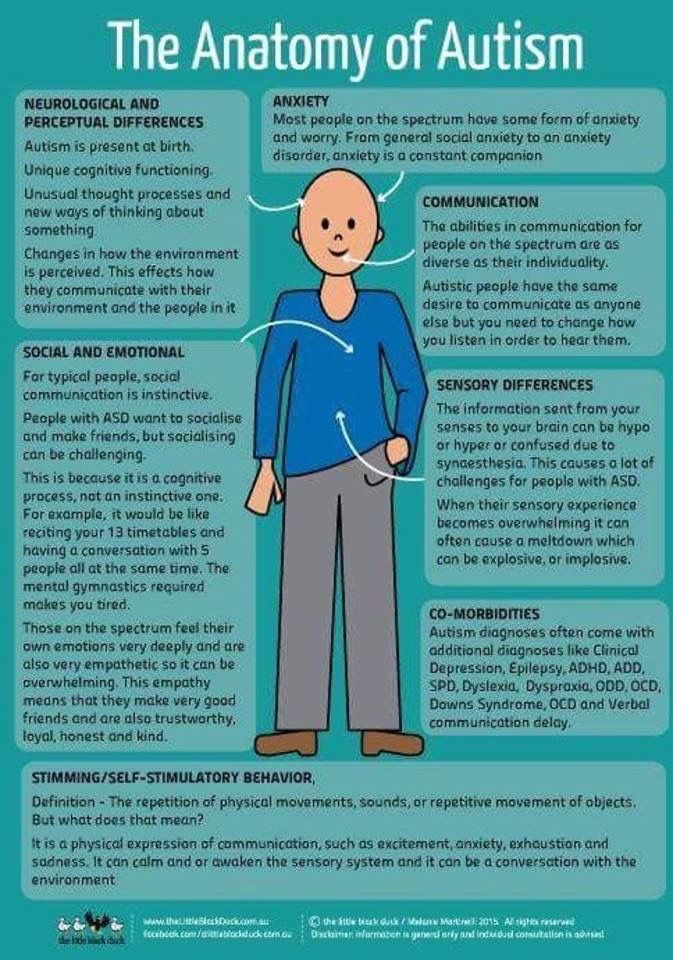

Current day researchers are working to understand this social disconnect. Their observations have shown us that, whereas typical infants are “pre-wired by evolution with the motivation and capacity to begin establishing an immediate social relationship with their caregivers," 2 individuals with autism tend not to focus on human faces or voices. They tend neither to look at their caregivers, nor to establish “joint attention” with them in order to create shared experiences.3 They do not point at a doll, an airplane, a golden retriever, looking from object to parent and back again, to show and to enjoy together.

Even when a person with autism does manage to focus on the social world, they have great difficulty interpreting what they see and hear. Whatever it is that permits typically-developing people to instantly make a good guess about another person’s mental or emotional state, it is not functioning properly in people with autism. They are said to have mindblindness4 -- that is, they lack the ability to take another’s perspective, to “read” where they are coming from, and to respond in kind.

They are said to have mindblindness4 -- that is, they lack the ability to take another’s perspective, to “read” where they are coming from, and to respond in kind.

For those with a family member who has been diagnosed with autism, this may be the most distressing aspect of the disorder: to love a child, grandchild, or sibling who cannot fully connect with you in the way that you had hoped. It is no wonder that most interventions include at least some focus on helping a person with autism relate to the people in their family and the larger world.

See also:

- Challenging Behaviors: Social Issues

- Insights from Neuroscience

- Cognitive Theories Explaining ASDs

References

- Kanner, L. (1943). Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child, 2, 217-250. (pg. 220)

- Carter, A.S., Davis, N.O., Klin, A., & Volkmar, F. (2005). Social development in autism. In F. Volkmar et al. (Eds.

), Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders (pp.312-334). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. (pg. 317)

), Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders (pp.312-334). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. (pg. 317) - Mundy, P., & Burnette, C. (2005). Joint attention and neurodevelopmental models of autism. In F. Volkmar et al. (Eds.), Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders (pp.650-681). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Baron-Cohen, Simon. (1995). Mindblindness: An essay on autism and theory of mind. Cambridge, MA; London: The MIT Press.

Please rate the helpfulness of this article:

How to teach a child with autism social skills?

01/17/15

Description

“I'm not asking my daughter to be a party star or socialite. I just want her to be happy and have her own friends. She is a wonderful child, and I hope one day others will notice it too.”

Lack of social skills development in autism spectrum disorders

In fact, many parents of children with autism will agree with this opinion regarding the social behavior of their children. They know that their child has a lot of great qualities that they could offer to others, but the nature of their disorders, and more specifically, their low level of socialization, often prevents them from making meaningful social contacts. This frustration is heightened when a parent knows that their child is desperate to make friends with others, but fails to make friends.

They know that their child has a lot of great qualities that they could offer to others, but the nature of their disorders, and more specifically, their low level of socialization, often prevents them from making meaningful social contacts. This frustration is heightened when a parent knows that their child is desperate to make friends with others, but fails to make friends.

Often their failure is directly caused by ineffective programs and insufficient resources that are available for social skills training. For most children, social skills (such as "waiting in line", "conversation") are acquired easily and quickly. For children with autism, the process is much more complicated. While many children learn these socialization skills simply by participating in social situations, children with autism spectrum disorders often need to be taught in detail, and as early as possible. This article focuses on the underdevelopment of social skills in children with autism and describes a five-step model for learning to communicate, with particular emphasis on the relatively new and increasingly popular method of assistance - video modeling.

Lack of interest in socializing or not knowing what to do

Social functioning disorder is a major feature of autism. A typical lack of development of social skills concerns starting a conversation, responding to an invitation to talk from other people, eye contact, reading other people's non-verbal cues, the ability to look at what is happening from the other's point of view. The reasons for the underdevelopment of these skills can range from congenital neurological disorders to the inability to acquire these skills (social isolation). Most importantly, the underdevelopment of these skills prevents a person from developing and maintaining meaningful and satisfying relationships. And although the lack of social skills becomes central to autism spectrum disorders, many such children do not receive sufficient training in these skills (Hume, Bellini, & Pratt, 2005).

This is a worrying situation, especially given the fact that having a social disorder can lead to more debilitating problems such as poor school performance, communication and peer rejection, anxiety, depression, and other negative outcomes ( Bellini, 2006; Tantam, 2000; Welsh, Park, Widaman, & O'Neil, 2001). And having a personalized social skills plan is all the more relevant given that there are effective social skills teaching approaches that can reduce these challenges.

And having a personalized social skills plan is all the more relevant given that there are effective social skills teaching approaches that can reduce these challenges.

The long held belief that children with autism spectrum disorders lack the motivation to communicate is often wrong. Many children with autism actually want to communicate, however, these children often lack the skills to communicate effectively. One young man I worked with is a good example of this. Prior to my visit, the school administration informed me of his inappropriate behavior and his apparent "lack of interest" in interacting with other children. After Zak spent the morning in a separate classroom, he was allowed to have breakfast with the entire school population (at this time and in this place most of the problem behavior occurs). While he was eating his breakfast, a group of children to his right started talking about frogs. As soon as the conversation began, he immediately noticed it. And I noticed too. As he listened to the other children, he began to take off his shoes and then his socks. I remember thinking, "God, it's starting!" As soon as the second sock hit the floor, Zach threw his feet up on the table, looked at the group of children and exclaimed, “Look, webbed feet!” Other children (including myself) looked on in surprise. In this case, Zach has shown a desire to be part of a social situation, but he clearly lacks the necessary skills to do so in an appropriate and effective way.

As he listened to the other children, he began to take off his shoes and then his socks. I remember thinking, "God, it's starting!" As soon as the second sock hit the floor, Zach threw his feet up on the table, looked at the group of children and exclaimed, “Look, webbed feet!” Other children (including myself) looked on in surprise. In this case, Zach has shown a desire to be part of a social situation, but he clearly lacks the necessary skills to do so in an appropriate and effective way.

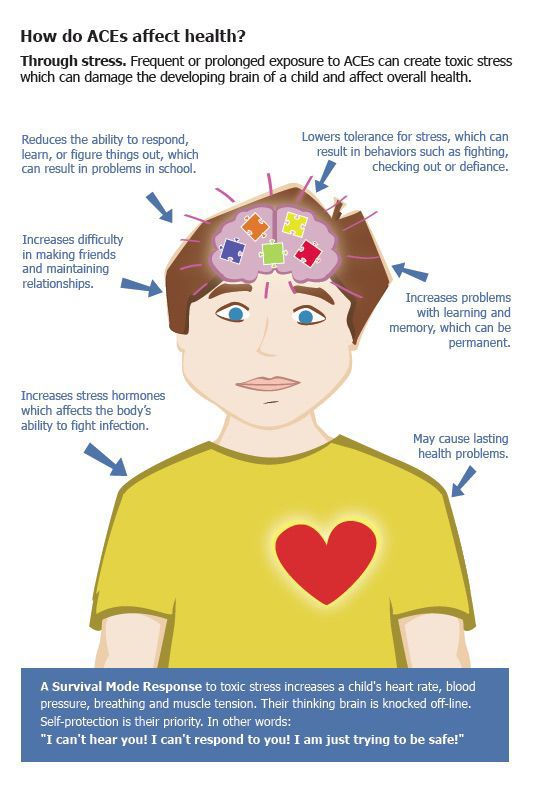

This lack of knowledge "how to do it" can also lead to social anxiety in some children. Many parents and teachers report that social situations tend to cause a lot of fear in their children. The way children with autism describe this anxiety is reminiscent of what many of us feel when we are forced to perform in front of an audience (increased heart rate, noticeable trembling, concentration problems, etc.). Not only the performance itself is stressful, the very thought of it is enough to create this painful feeling. Imagine how your life would be if every social interaction you make caused as much anxiety as giving a speech in front of a large group of people.

Imagine how your life would be if every social interaction you make caused as much anxiety as giving a speech in front of a large group of people.

A typical defense for most of us is to reduce stress and anxiety by avoiding stressful situations. For children with autism spectrum disorders, this often leads to avoidance of all social situations and, as a result, the development of a lack of social skills. When a child constantly avoids communication, he does not give himself the opportunity to acquire social skills. For some children, this lack of skill leads to negative experiences with peers, peer rejection, isolation, anxiety, depression, drug use, and even suicidal thoughts. For others, it forms a pattern of total immersion in different hobbies and interests in solitude, and this pattern is often very difficult to change.

Five step model

1. Assess social interaction.

2. Distinguish between lack of skill acquisition and lack of application.

3. Select intervention strategies.

Select intervention strategies.

4. Intervention.

5. Evaluate and monitor progress.

This paragraph briefly describes my five-step model for teaching social skills (Bellini, 2006). Before starting to provide social skills training, it is important to start with a detailed assessment of their current level. When the assessment is completed, the next step is to recognize the difference between difficulties in acquiring skills and difficulties in applying them. Based on this information, we choose an intervention strategy. Once an intervention is initiated, it is essential to evaluate and modify the intervention strategy as needed. Although I use the word steps, it is important to note that this model is not completely linear. So, in real life, social skills training will not follow a rigid path from step one to step five. For example, quite often I notice an additional lack of social skills (stage one) while I have already begun the intervention process (stage four). In addition, I am constantly evaluating and changing the way I intervene as more information and data become available.

In addition, I am constantly evaluating and changing the way I intervene as more information and data become available.

Social Interaction Assessment

The first step in any social skills training program should be to conduct a complete assessment of the child's current level of social interaction. The purpose of this assessment is to answer a simple yet complex question: What prevents a child from starting and maintaining social relationships? For many children, the answer takes the form of a lack of certain social skills. For others, the cause is cruel and ignorant peers. For others, it's both.

Testing should show in detail both the strengths and weaknesses of the child in terms of his presence in society. Evaluation should be a combination of observation (both natural and structured), interviews (with parents, teachers on the playground, and the child themselves) and standard measurements (behavior tests and social skills measurements). I have developed the Autistic Social Skills Profile, which helps identify common social skill deficiencies in children with autism and tracks the progress a child is making in learning. Kathleen Quill (2000) also provides an excellent social skills checklist for parents and teachers in her book Do-Look-Listen-Say. It is important for the team that works with the child to determine the current level of interaction and effectively intervene in the area where the child needs help. For example, if testing indicates that the child is unable to have simple one-on-one conversations with others, then intervention should begin with that, and not with more complex levels of group communication. Or, if the research shows that the child does not know how to symbolically or even functionally use toys, then the correction will most likely begin with teaching play skills to learning social skills. Once the detailed social interaction assessment is complete, the team should determine whether the lack of skills is due to a lack of skill acquisition or skill application.

Kathleen Quill (2000) also provides an excellent social skills checklist for parents and teachers in her book Do-Look-Listen-Say. It is important for the team that works with the child to determine the current level of interaction and effectively intervene in the area where the child needs help. For example, if testing indicates that the child is unable to have simple one-on-one conversations with others, then intervention should begin with that, and not with more complex levels of group communication. Or, if the research shows that the child does not know how to symbolically or even functionally use toys, then the correction will most likely begin with teaching play skills to learning social skills. Once the detailed social interaction assessment is complete, the team should determine whether the lack of skills is due to a lack of skill acquisition or skill application.

Distinguishing between insufficient mastery of skills and insufficient practice in their application

Following a full examination of the level of social interaction of the child and after determining the skills that we will teach him, it is necessary to understand whether the reason for the underdevelopment of social skills is a lack of acquisition or a lack of their application (Elliott & Gresham, 1991). Simply put, the success of your social skills training program depends on your ability to distinguish between the two.

Simply put, the success of your social skills training program depends on your ability to distinguish between the two.

Lack of skill acquisition refers to the absence of a particular skill or behaviour. For example, a child with autism may not know how to successfully join their peers' activities and therefore he or she is often unable to participate. If we want a child to join his peers, we must teach him to do so.

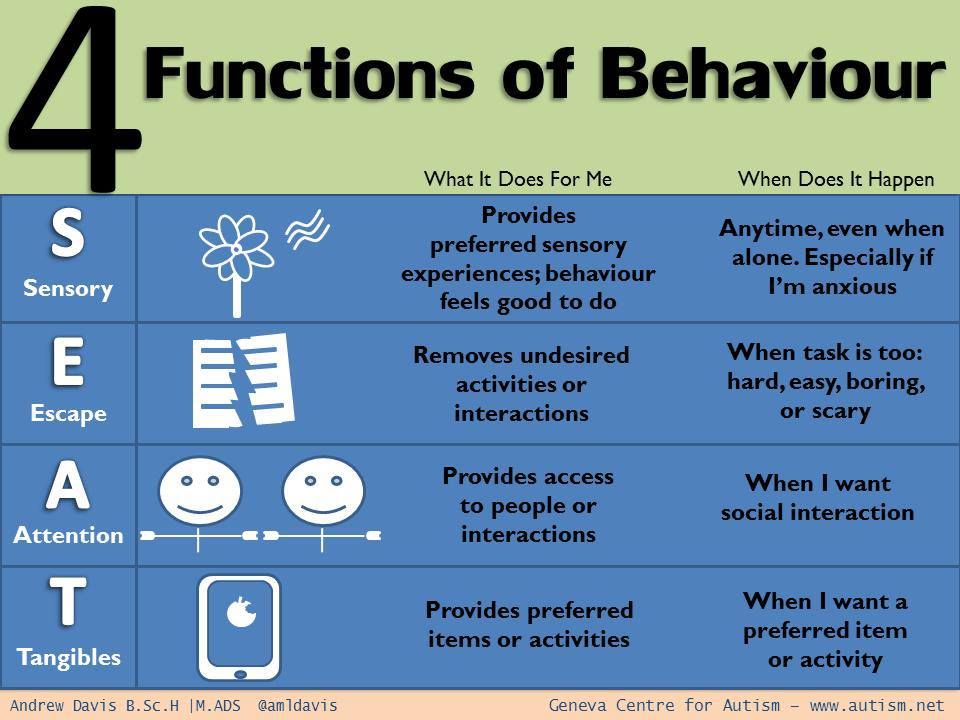

Lack of skill application implies that the skill or behavior is familiar to the child but is not shown or used. In the same example, a child may have the skill of joining, but, for some reason, he does not succeed. In this case, if we want the child to take part, we do not have to teach him to do this (since he already knows how). Instead, we need to work on what hinders the use of the skill, which could be a lack of motivation, anxiety, or sensory sensitivity.

A good sign to distinguish between a lack of acquisition of a skill and a lack of use is the question "Can a child demonstrate a skill with many people and in many situations?" For example, if a child only talks to his mother at home and does not interact with peers at school, then this difficulty should be considered as a lack of mastery of the skill. I often hear from school teachers: “The child communicates well with me, so this must be a lack of use of the skill, right?” Not really. In my experience, children with autism communicate more often and better with adults, because adults usually make it easy for them - adults do all the “work” of communication for the child. In baseball terms, just because Tommy can hit the soft, low throws his dad practices at home doesn't mean he's good enough to hit the ball his peers throw at him on the playground. Sometimes an adult's interaction with a child on the autism spectrum is like those soft, low tosses. And although they do this with good intentions, it does not prepare the child for more difficult moments of communication with peers.

I often hear from school teachers: “The child communicates well with me, so this must be a lack of use of the skill, right?” Not really. In my experience, children with autism communicate more often and better with adults, because adults usually make it easy for them - adults do all the “work” of communication for the child. In baseball terms, just because Tommy can hit the soft, low throws his dad practices at home doesn't mean he's good enough to hit the ball his peers throw at him on the playground. Sometimes an adult's interaction with a child on the autism spectrum is like those soft, low tosses. And although they do this with good intentions, it does not prepare the child for more difficult moments of communication with peers.

Very often underdevelopment of social skills and unacceptable behavior are justified by a lack of use of skills. This is because we tend to think that if a child does not exhibit a behavior, it is due to rejection or lack of motivation. In other words, we think that a child who does not start socializing with peers can do it, but does not want to (lack of skill use). In many cases, this is an erroneous assumption. In my experience, most cases of lack of social skills in children with autism relate to the lack of these skills.

In many cases, this is an erroneous assumption. In my experience, most cases of lack of social skills in children with autism relate to the lack of these skills.

So if children with autism do not demonstrate some social skills, then most likely it is not because they do not want or refuse to be around other people, but because they simply do not have these skills. If we want young children to be successful in communication, then we must teach them exactly how to communicate. Therefore, it is important to focus on skill development.

The benefit of using the learning deficit/skill use gap model is that it helps us choose intervention strategies. Most corrective methods are better suited to either one or the other. The chosen method of intervention should correspond to the existing deficiency. You don't want to use an intervention program designed for lack of skill use if the child's main difficulty is mastering the skill.

In the example above, if Tommy hasn't mastered the batting skill (Lack of Mastery), no rewards in the world (not even pizza) will help Tommy hit the ball during the game. If we want him to hit shots well, we must additionally teach him the mechanics of hitting the ball. The same is true for social skills. If we want a child to communicate freely, then we must effectively teach him social skills. On the contrary, if Tommy has sufficient skills, but lacks the motivation to "go all out", then cheese and pepperoni pizza may be what will help him play successfully on the field.

If we want him to hit shots well, we must additionally teach him the mechanics of hitting the ball. The same is true for social skills. If we want a child to communicate freely, then we must effectively teach him social skills. On the contrary, if Tommy has sufficient skills, but lacks the motivation to "go all out", then cheese and pepperoni pizza may be what will help him play successfully on the field.

Once the detailed assessment of social skills has been completed and the team can attribute social difficulties to either a lack of skill acquisition or a lack of skill use, training can begin. There are many methods that can be applied to children with autism. Most importantly, the strategies that are applied to the child are suited to his personal needs, and that a logical explanation is given for the method used.

The following are examples of techniques that can be used to successfully teach communication skills to children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. All of the strategies listed below, except for the peer-based approach, are skill learning disadvantages. However, some methods (notably the video self-modeling method and the social story method) also work well when there is a lack of skill use. In addition, it is important to constantly reward the child for his efforts and participation in the educational program.

All of the strategies listed below, except for the peer-based approach, are skill learning disadvantages. However, some methods (notably the video self-modeling method and the social story method) also work well when there is a lack of skill use. In addition, it is important to constantly reward the child for his efforts and participation in the educational program.

Choice of remedial strategies

Change the child's environment or behavior

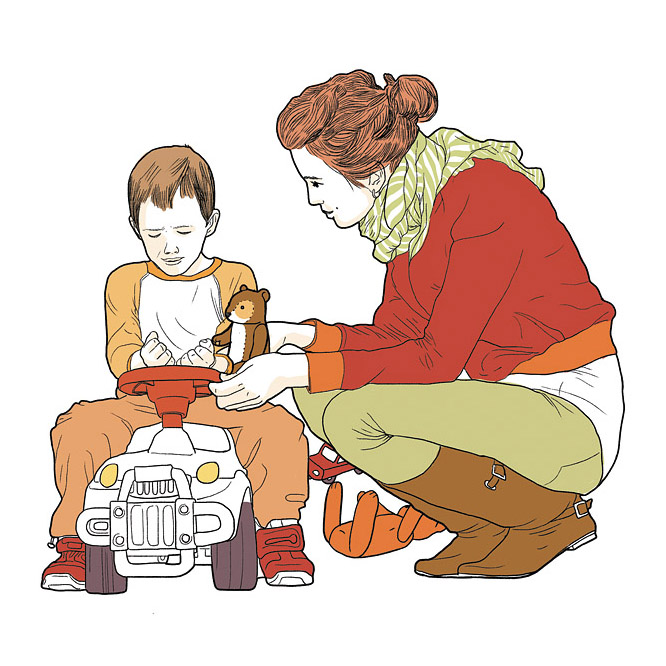

It is important to consider the principle of "changing the child's environment or behavior" when choosing a correction method. In the context of social skills training, the child's social or physical environment can be changed to provide opportunities for positive social interaction. Examples of this include: teaching peer helpers how to interact with the child during the school day, autism awareness training for classmates, including the child in different leisure groups such as sports teams or scouting squads.

On the other hand, you can change not the environment, but work on the behavior of the child himself. This includes learning that allows the child to be more successful in communication. A successful social skills development program must include both changes in the child's environment and work on his behavior. If you focus on only one thing, then your efforts may fail.

For example, one family I worked with did an excellent job of arranging peer play sessions for their child and ensuring that they attended various leisure activities in groups. At the same time, they were very disappointed that their son was unable to make friends, and he still had negative moments in communication with peers. The problem was that they put the cart before the horse. They provided the child with enough opportunities to communicate with others, but did not teach him the skills necessary to be successful in this communication.

Similarly, teaching a child a skill (behavior change) without changing the environment to be more friendly to the child with autism also leads the child to fail. This happens when a child with autism enthusiastically tries a newly acquired skill in a group of peers who do not accept it. It is important to both teach skills and change the environment. This will ensure that the new skill will be met with understanding by peers.

This happens when a child with autism enthusiastically tries a newly acquired skill in a group of peers who do not accept it. It is important to both teach skills and change the environment. This will ensure that the new skill will be met with understanding by peers.

Methods of teaching social skills

As previously stated, children and adolescents with autism need to be given extensive and detailed instruction in social skills. Traditional methods of teaching social skills (such as board games about friendship and proper classroom behavior) are confusing for many children with autism. For example, a school psychologist was frustrated with the little progress she had made with a student with autism. She claimed that the training program showed positive results in "other children in the group", but the child with autism did not seem to "understand" her. Of course he didn't understand! The reason was obvious. The school psychologist tried to teach the students the concept of "friendship". This is acceptable to other students, but for children with autism, these explanations were too abstract. So, instead of spending endless time telling a child about “friendship,” the training should have focused on specific skills that a child could use to make and keep friends. Experience tells me that the concept of "friendship" is much easier to understand when you already have a friend or a couple of friends!

This is acceptable to other students, but for children with autism, these explanations were too abstract. So, instead of spending endless time telling a child about “friendship,” the training should have focused on specific skills that a child could use to make and keep friends. Experience tells me that the concept of "friendship" is much easier to understand when you already have a friend or a couple of friends!

There are a number of issues to consider when choosing an intervention. For example, does the training program address the lack of skill acquisition identified in the Social Interaction Assessment? Does the program improve its use? Does the program provide an opportunity to master the skill? Are there studies supporting its use? If not, how do you plan to evaluate its effectiveness for your child? Is the program suitable for the child's developmental level? What follows is a list of social skills teaching methods that have proven effective in teaching children with autism.

The following part of the article briefly describes the various intervention strategies that have been developed to teach social skills to young children with autism, including peer intervention, thought and feeling exercises, social stories, role playing, and video modeling.

Peer intervention

The use of peers as facilitators is one good example of effective intervention for young children with autism. Peer intervention is often used to establish positive social interaction among preschool peers (Strain & Odom, 1986; Odom, McConnell, & McEvoy 1992). Peer-involved learning allows us to structure the physical and social environment in a way that creates successful moments of social interaction.

With this approach, peers are trained to engage in communication and respond immediately and appropriately to the desire of a child with autism to communicate during the school day. Peer helpers must be classmates of the child with autism, must have age-appropriate social and play skills, must attend school regularly, and must have previously interacted with children with autism in a positive (or at least neutral) way. Peer helpers should also be taught about autism behaviors in a polite and age-appropriate way.

Peer helpers should also be taught about autism behaviors in a polite and age-appropriate way.

Using these helpers allows teachers and other adults to act as facilitators rather than active interlocutors and play partners. So, instead of becoming the third wheel in communication between two children, the teacher helps peers start a conversation or respond appropriately to a child with autism and walks away. Involving peers in communication also helps to generalize new skills and practice them in a natural environment.

Lessons about thoughts and feelings

Recognizing and understanding thoughts and feelings, both one's own and those of others, is often the Achilles' heel of children with autism and is essential for successful communication. For example, we constantly change our behavior according to the non-verbal feedback we receive from other people. We can continue the story if the other person smiles, looks expectantly, or shows other signs of genuine interest. On the other hand, if a person keeps looking at his watch, sighs, looks the other way, we will probably shorten our story (I said “probably”!). Children with autism often have difficulty recognizing and understanding these non-verbal cues. This makes it harder for them to modify their behavior to meet the emotional and mental needs of others.

On the other hand, if a person keeps looking at his watch, sighs, looks the other way, we will probably shorten our story (I said “probably”!). Children with autism often have difficulty recognizing and understanding these non-verbal cues. This makes it harder for them to modify their behavior to meet the emotional and mental needs of others.

The simplest activity about thoughts and feelings involves showing the child pictures of various expressions of emotion. Pictures can range from the most basic, such as happy, sad, angry, or scared, to more complex emotions, such as embarrassed, bashful, nervous, or incredulous. Start by asking the child to point to an emotion (“show where happy is”), then ask the child to identify how the character feels (“how does he feel?”).

Many of the young children I work with learn to identify emotions quite easily. When they are already good at this, it's time to move on to more complex teaching methods, such as teaching the meaning of an emotion or "why?" this emotion appears. To do this, the child needs to draw conclusions based on the context and signs shown in the picture. So, based on the information in the picture, you can ask "Why is the child sad?". The pictures should depict characters participating in different social situations and showing different facial expressions or other non-verbal ways of expressing emotions. You can cut out pictures from magazines or download and print them from the Internet. You can also use illustrations from children's books, which are usually rich in emotional content and situational images.

To do this, the child needs to draw conclusions based on the context and signs shown in the picture. So, based on the information in the picture, you can ask "Why is the child sad?". The pictures should depict characters participating in different social situations and showing different facial expressions or other non-verbal ways of expressing emotions. You can cut out pictures from magazines or download and print them from the Internet. You can also use illustrations from children's books, which are usually rich in emotional content and situational images.

Once the child is good at pictures, switch to TV programs and videos of social situations. Many programs that are shown on TV are excellent sources of material for classes, as they show characters in social situations, and they clearly express their emotions. You can use the same mechanism as with the pictures, but this time the child will draw conclusions from dynamic social cues. Just ask your child to identify how the characters on the screen feel and why they feel the way they do. When the action is too fast for the child, press pause and ask a question about a still picture (make sure your TV shows a clear picture during the pause).

When the action is too fast for the child, press pause and ask a question about a still picture (make sure your TV shows a clear picture during the pause).

Social stories

Social stories are often used in teaching social skills to children with disabilities. Social stories are an unobtrusive way to explain social concepts and rules to children in the form of a short story. This strategy can be used to teach a range of social and behavioral concepts such as crossing the street, participating in a game, and driving out of town.

Carol Gray (1995; 2000) outlines the components necessary for a successful social story: the story must be written in response to the specific needs of the child, the child must be willing to read the story for himself (depending on his level of ability), the story must be appropriate ability and level of understanding of the child, the story should contain less descriptive “can” or “could” instead of “will” and “should”.

This last component is especially important for children who tend to refuse to follow instructions from adults (that is, a child who does not decide what to do until you tell him to do something . .. and he will do exactly the opposite!) . The social story can be illustrated with pictures or played on a computer to use the child's visual thinking or interest in the computer.

.. and he will do exactly the opposite!) . The social story can be illustrated with pictures or played on a computer to use the child's visual thinking or interest in the computer.

I have found that children with autism learn best when social stories are used in conjunction with role play as a "textbook for communication". Thus, after reading a social story, the child practices the skill presented in that story. For example, immediately after reading a story about games with peers, the child will try this skill in the form of a role play. Then, after reading the story and practicing, the child will be involved in a social situation where he will have the opportunity to use this skill in a natural setting.

Role play/behavioral rehearsal

Role play and behavioral rehearsal are primarily used to teach basic communication skills. It is an effective approach for teaching social skills that allows for the positive practice of these skills (Gresham, 2002). Role play involves acting out situations or activities in a structured environment to practice newly acquired skills and strategies or previously acquired skills that the child has difficulty using. Role plays can be scripted or spontaneous. In the second case, the situation is described to the child (for example, asking another child to play with him), but no specific scenario is given. I usually combine prewritten and unwritten elements in every RPG. For example, a child may be given a question or a first sentence, but the rest of the conversation should be spontaneous.

Role play involves acting out situations or activities in a structured environment to practice newly acquired skills and strategies or previously acquired skills that the child has difficulty using. Role plays can be scripted or spontaneous. In the second case, the situation is described to the child (for example, asking another child to play with him), but no specific scenario is given. I usually combine prewritten and unwritten elements in every RPG. For example, a child may be given a question or a first sentence, but the rest of the conversation should be spontaneous.

I use role play to teach children many communication skills, especially those that involve starting a conversation, answering and ending a conversation. In one of the scenarios, the child has to start a conversation with a peer who is busy with something. Therefore, he will have to ask permission to join or engage the interlocutor in his own game. The latter is usually the most difficult for children with autism.

During the first learning sessions, it is typical for a child to get stuck in conversations and interactions for several minutes, not knowing what to say or how to proceed. At an early stage, the child should be given enough time to understand and respond to the role-play scenario. As you progress, your speed and confidence will increase.

Video Modeling and Video Self Modeling

Video modeling is by far one of the most effective strategies for teaching social skills I have used with autistic children. Video modeling involves watching a demonstration of some behavior on video and then repeating the behavior of the model. Peers, adults or the child himself (video self-modeling) can participate in video modeling. The advantage of video self-modeling is that it becomes a visual confirmation of success for the child ... his own success! Video self-simulation can be used to master skills, improve skill use, and reduce problem behaviors. It combines a powerful learning tool for a child with autism (visual instruction) with an effective intervention (simulation).

A growing body of research is promising great success in using video modeling (with a peer or adult as a model) and video self modeling as a therapeutic approach for children with autism. Bellini and Akullian (book in progress) conducted an analysis of video modeling and video self-modeling studies, including 20 papers by their colleagues, in which 63 children with autism participated. The results confirm that video modeling and video self modeling are effective interventions for social communication skills, unwanted behaviors, and functional skills in children and adolescents with autism. In particular, these methods provide an opportunity for skill acquisition, and these skills, acquired through video modeling and video self-simulation, are retained over time and transferred to other people and situations. Thus, this approach can be considered effective for children with ASD from early to adolescence. Studies have shown a dramatic increase (or decrease) in selected behaviors with an average intervention duration that corresponded to watching nine videos. At the same time, the average duration of the videos shown to the participants was only three minutes.

At the same time, the average duration of the videos shown to the participants was only three minutes.

Video self-modeling generally falls into two categories: positive self-image and video behavior (Dowrick, 1999).

Creating a positive self-image allows children to observe behavior that is already in their behavioral repertoire. Creating a positive self-image can be used for behaviors that are very rare or that the child has stopped using. An example of positive self-image correction for preschoolers would be to videotape the child participating in something with peers (if this is rare) and then show the video to the child. Buggy and his colleagues (1999) used this method to increase response rates in young children with autism. The children in the study watched videos of themselves answering questions while playing. Although these children rarely answered the questions, the videos were edited to show that the children answered freely (points where there were no answers were removed from the records). This intervention dramatically increased the number of verbal responses that children began to give without prompting.

This intervention dramatically increased the number of verbal responses that children began to give without prompting.

Video Behavior Shaping, another category of video self-modelling, is typically used when the child already has the required skills in their repertoire but is unable to combine them to complete the activity. For example, a child can get out of bed, brush their teeth, get dressed, and comb their hair (morning routines), but cannot perform these actions in the correct sequence and without prompting. With this correction method, we will record on video how the child performs each procedure, and then put the fragments in the desired sequence. The same can be done with regular social communication sequences. For example, you could record a child doing the following three things: starting a conversation, responding to another child, and ending the conversation in an acceptable way. The three scenes can then be combined together to make one successful free talk.

Video behavior shaping is also helpful for children who need extra help or support to successfully complete a task. Accounting for "hidden support" is an important component in correcting video behavior. For example, you can record how a child communicates with peers while an adult helps him with gestures and prompts. Adult prompts will be cut out (hidden) so that when the child watches the video, they will see how independent and successful they are. Behavior shaping on video requires additional technical capabilities compared to the method of creating a positive image of yourself, but usually it requires less "raw" video material.

Accounting for "hidden support" is an important component in correcting video behavior. For example, you can record how a child communicates with peers while an adult helps him with gestures and prompts. Adult prompts will be cut out (hidden) so that when the child watches the video, they will see how independent and successful they are. Behavior shaping on video requires additional technical capabilities compared to the method of creating a positive image of yourself, but usually it requires less "raw" video material.

Delivering the intervention

Once you have assessed social functioning and selected the skills to be taught, differentiated between lack of skill acquisition and lack of use of the skill, and selected an intervention method, it is time to start making adjustments. Social skills training should take place in different places (at home, in the classroom, in the resource classroom, on the playground, among other people, etc.) and by different instructors. There is no "best" place for social skills training, although it is important to keep in mind that the goal of any socialization training is to enable the child to be socially successful with their PEERS in a NATURAL environment. As such, if a child is being taught social skills in a resource class at school (or with the help of a private therapist), there needs to be a plan in place to transfer those skills from the resource class to the natural environment. Parents and teachers should look for opportunities to support and encourage the skills that a child is taught in a resource class or remedial center.

As such, if a child is being taught social skills in a resource class at school (or with the help of a private therapist), there needs to be a plan in place to transfer those skills from the resource class to the natural environment. Parents and teachers should look for opportunities to support and encourage the skills that a child is taught in a resource class or remedial center.

The level of skill development depends on the individual child. Some children will start using a skill after two or three sessions, while other children will need three months before they start to "grasp" the material and begin to use their newly acquired skills. Of course, simply using or trying out a skill is only the first step to social success. Your child will need extra time to improve the skills they are learning and developing. Gresham et al. (2001) recommend that social skills training be given more frequently and intensively than conventional training. They concluded that "thirty hours distributed over 10-12 weeks is not enough. " Social skills training should be intensive (as often as possible) and inclusive (occurring in whatever environment the child is in).

" Social skills training should be intensive (as often as possible) and inclusive (occurring in whatever environment the child is in).

Evaluate and change intervention

Although the last item on the list is “assess and change intervention”, it is certainly not the least important. Plus, it shouldn't be the last thing on your mind when designing a social skills training program. Usually, once I understand what skill gaps I need to work on, I begin to develop methods for evaluating the effectiveness of the correction. In the most basic example, if the purpose of the correction is to start a conversation, then I can use data on the frequency of conversations with peers and adults as a basis. Then I will continue to collect data on the child's initiative in making conversations throughout the correction phase. Accurate data collection is essential to evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention. This allows us to understand if the child is benefiting from the education and how best to modify the program to best help the child. Within a school, accurate data collection is a must. When I work with school teachers, we focus on integrating the social skills curriculum with the child's behavioral and social goals. Thus, the fifth stage is usually an important aspect of development, intervention and integrity.

Within a school, accurate data collection is a must. When I work with school teachers, we focus on integrating the social skills curriculum with the child's behavioral and social goals. Thus, the fifth stage is usually an important aspect of development, intervention and integrity.

An example of using the described method

The following example describes a method for teaching social skills to a little girl diagnosed with autism. "Kelly" attended kindergarten and had a below-average speech ability. Although her vocabulary was average for her age group, she rarely used speech voluntarily with classmates and teachers. She only spoke in response to direct questions and only joined in when others started the conversation. Consequently, Kelly spent most of her time on the playground by herself, rarely interacting with her peers. The assessment of social skills led to the conclusion that she had a significant lack in the ability to start a conversation and continue a conversation with peers. Social skills correction was designed to increase the frequency and duration of conversations with peers. Data on conversations with peers (when she started them herself and when she answered peers) was collected both on the site and during breaks.

Social skills correction was designed to increase the frequency and duration of conversations with peers. Data on conversations with peers (when she started them herself and when she answered peers) was collected both on the site and during breaks.

Two peer helpers were selected to participate with Kelly in a playgroup. Peers were instructed to initiate conversation and respond immediately when Kelly spoke to them. Her peers were also given developmentally appropriate information about autism and Kelly's behavior, which included arm waving. Also, before starting work in the playgroup, Kelly was read a social story related to starting a conversation. Each time a story was read, Kelly was given the opportunity to practice the skill through role play. The children participated in the play group three days a week for two weeks. During group sessions, Kelly was given prompts to start a conversation herself, and she was also prompted to respond promptly and appropriately to her peers when they started a conversation with her. The sessions were videotaped over the course of two weeks. The video was then edited to remove all of Kelly's tips and help. Edited videos showed how Kelly communicated freely and successfully with peers. The tapes showed Kelly in five-minute chunks for two weeks. For Kelly, video self-modeling led to immediate improvements in making and maintaining social interactions both during the game and on the court. By the end of the school year, Kelly became friends with two children, with whom the friendship continues to this day.

The sessions were videotaped over the course of two weeks. The video was then edited to remove all of Kelly's tips and help. Edited videos showed how Kelly communicated freely and successfully with peers. The tapes showed Kelly in five-minute chunks for two weeks. For Kelly, video self-modeling led to immediate improvements in making and maintaining social interactions both during the game and on the court. By the end of the school year, Kelly became friends with two children, with whom the friendship continues to this day.

The purpose of this article is not to provide a list of all social skills interventions available to children with autism. Instead, the article presents a social skills training model that assists parents and professionals in socialization training. However, not all programs are suitable for every child. First, a huge amount of careful planning must be done to make sure that the methods used in the program meet the needs of the child. Therefore, a comprehensive intervention program is needed that addresses the individual characteristics (both strengths and weaknesses) of the child. In the example above, Kelly was given weekly social skills sessions in addition to sessions with a speech and occupational therapist. Kelly needed the full range of correction in order to be socially successful. As her mom told me, Kelly is unlikely to be a party star or a socialite. But after undergoing an effective social skills training program, Kelly had the opportunity to develop meaningful personal relationships. And we were given the opportunity to meet a wonderful child.

In the example above, Kelly was given weekly social skills sessions in addition to sessions with a speech and occupational therapist. Kelly needed the full range of correction in order to be socially successful. As her mom told me, Kelly is unlikely to be a party star or a socialite. But after undergoing an effective social skills training program, Kelly had the opportunity to develop meaningful personal relationships. And we were given the opportunity to meet a wonderful child.

See also:

How to use video to help children with autism

How to teach children with autism through social stories

Kira Solomatova: “We all need social stories”

How to develop social skills with autism through games

Thanks to Tamara Solomatina for the translation.

We hope you found this material useful or interesting. You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button.

Parenting with autism, Friendly environment, Methods and treatment, Social skills

Autism

Autism- Popular Topics

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Data and statistics »

- News bulletin

- The facts are clear

- Publications

- Find country »

- А

- Б

- В

- Г

- Д

- Е

- Ё

- Ж

- З

- И

- Й

- К

- Л

- М

- Н

- О

- П

- Р

- С

- Т

- У

- Ф

- Х

- Ц

- Ч

- Ш

- Щ

- Ъ

- Ы

- Ь

- Э

- Ю

- Я

- WHO in countries »

- Reporting

- Regions »

- Africa

- America

- Southeast Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- Media Center

- Press releases

- Statements

- Media messages

- Comments

- Reporting

- Online Q&A

- Developments

- Photo reports

- Questions and answers

- Latest information

- Emergencies "

- News "

- Disease Outbreak News

- WHO data »

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Monitoring Dashboard

- Basic moments "

- About WHO »

- CEO

- About WHO

- WHO activities

- Where does WHO work?

- Governing Bodies »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive committee

- Main page/

- Media Center/

- Newsletters/

- Read more/

- Autism

Key Facts

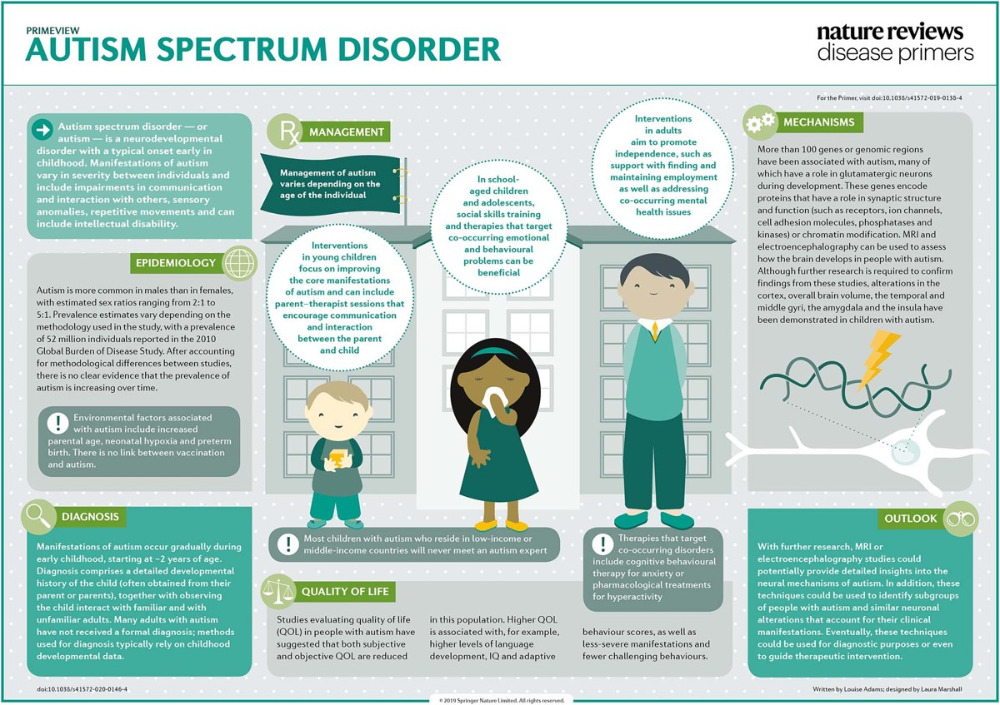

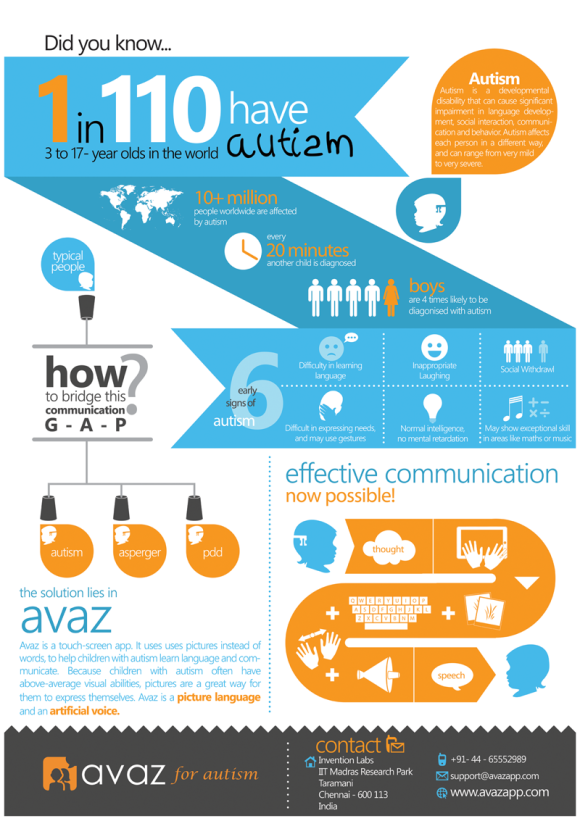

- Autism, also called autism spectrum disorder, is a diverse group of pathological conditions caused by the development of the brain.

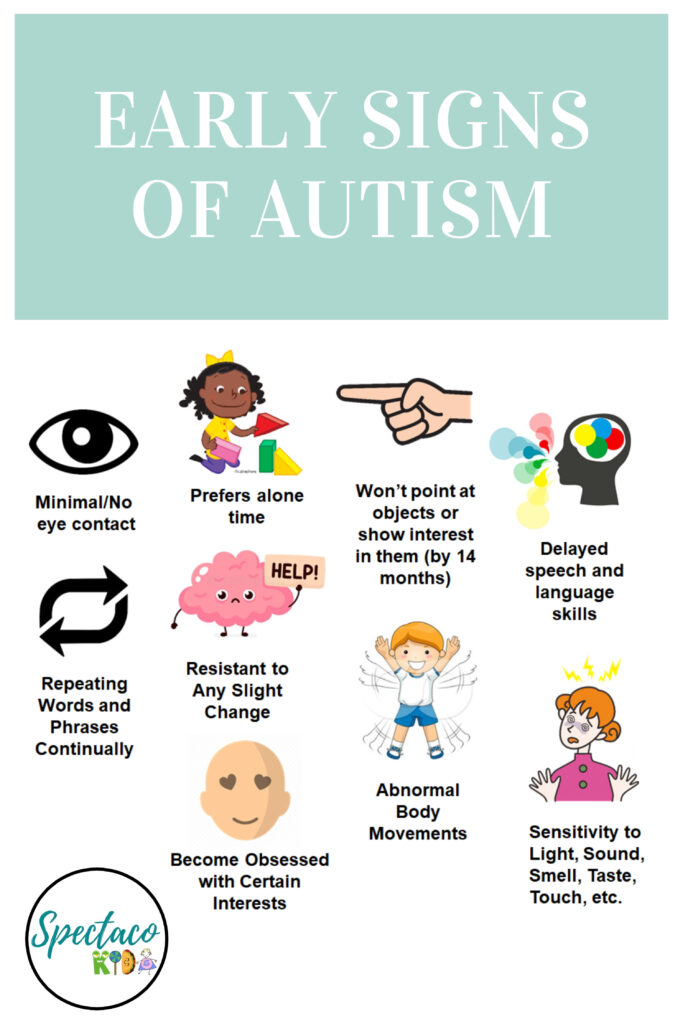

- Signs of autism can be detected in early childhood, but it is often not diagnosed until later in life.

- Approximately 1 in 100 children have autism.

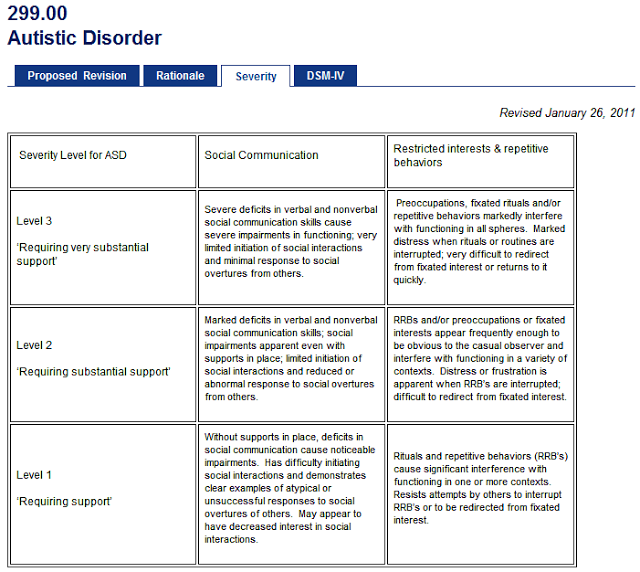

- The abilities and needs of people with autism can vary and change over time. Some people with autism are able to lead independent and productive lives, while others become severely disabled and require lifelong care and support.

- Evidence-based psychosocial interventions improve communication skills and social behaviors that positively impact the well-being and quality of life of people with autism and their caregivers.

- Care for people with autism must be accompanied by local and community action to make physical and social environments and relationships more accessible, inclusive and supportive.

Introduction

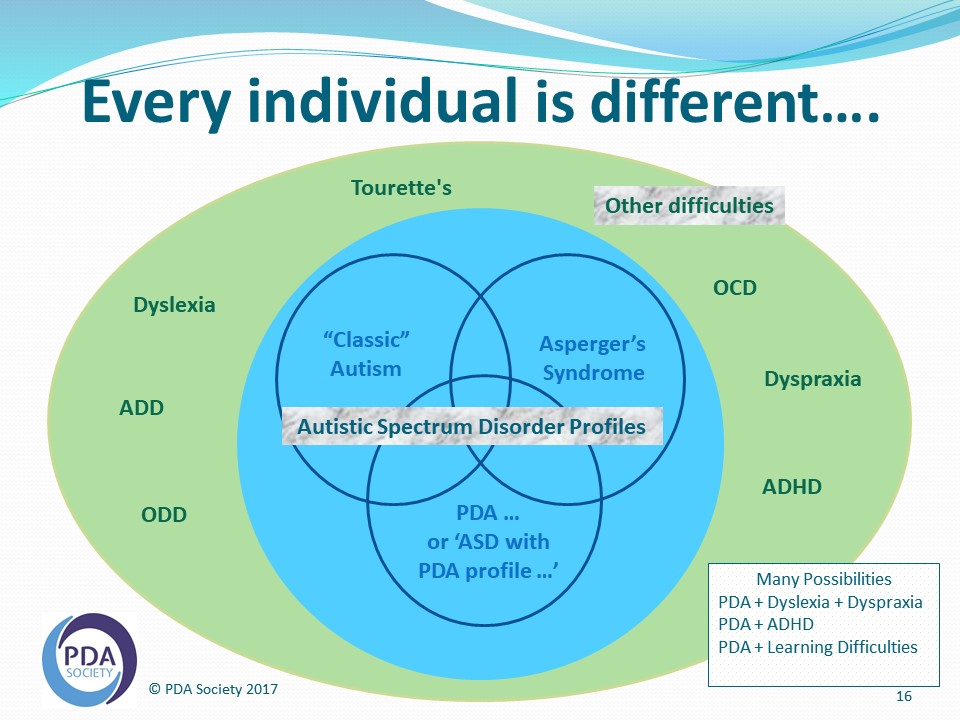

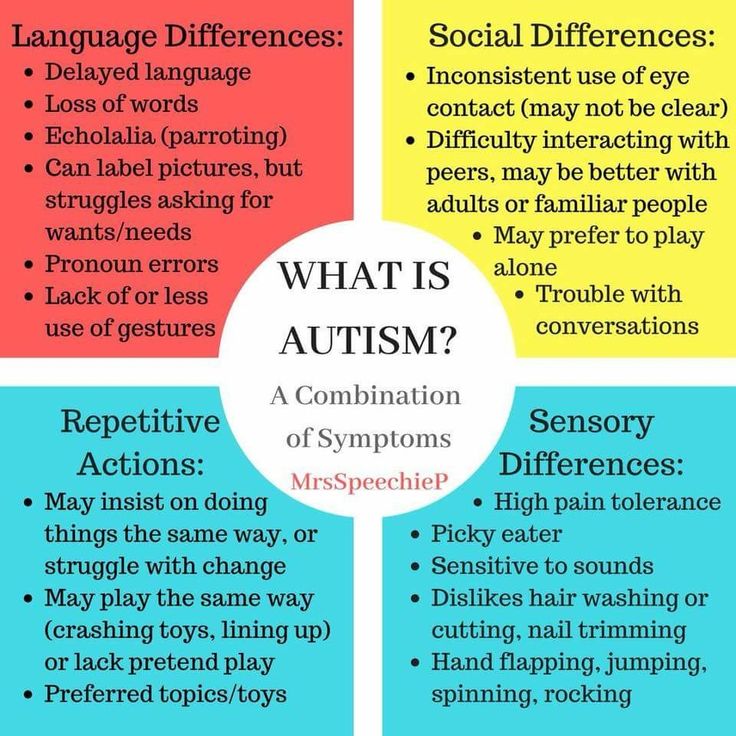

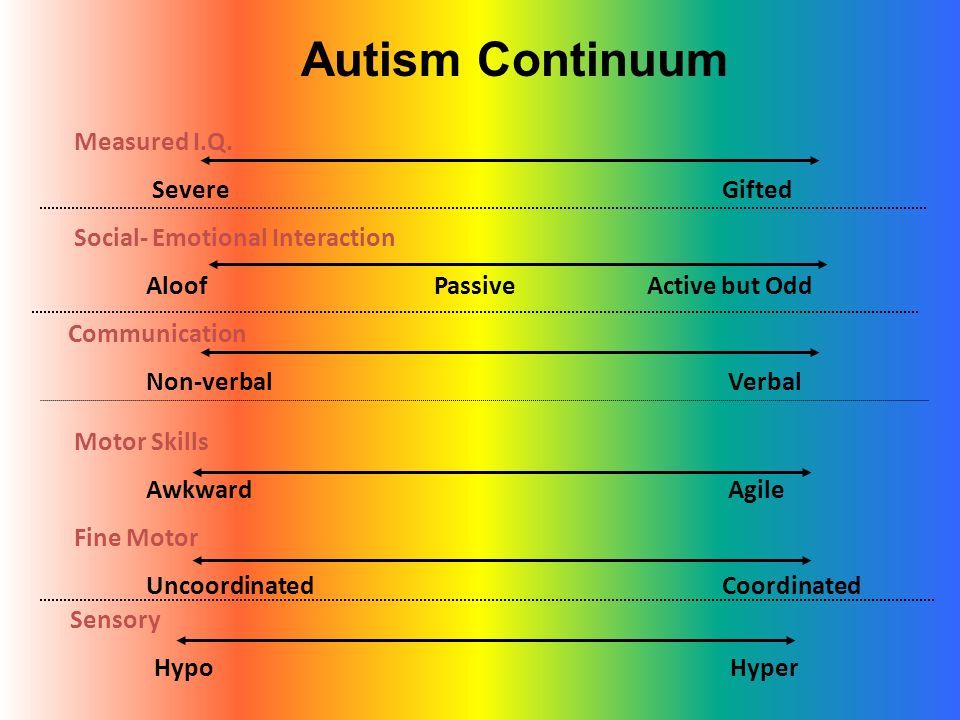

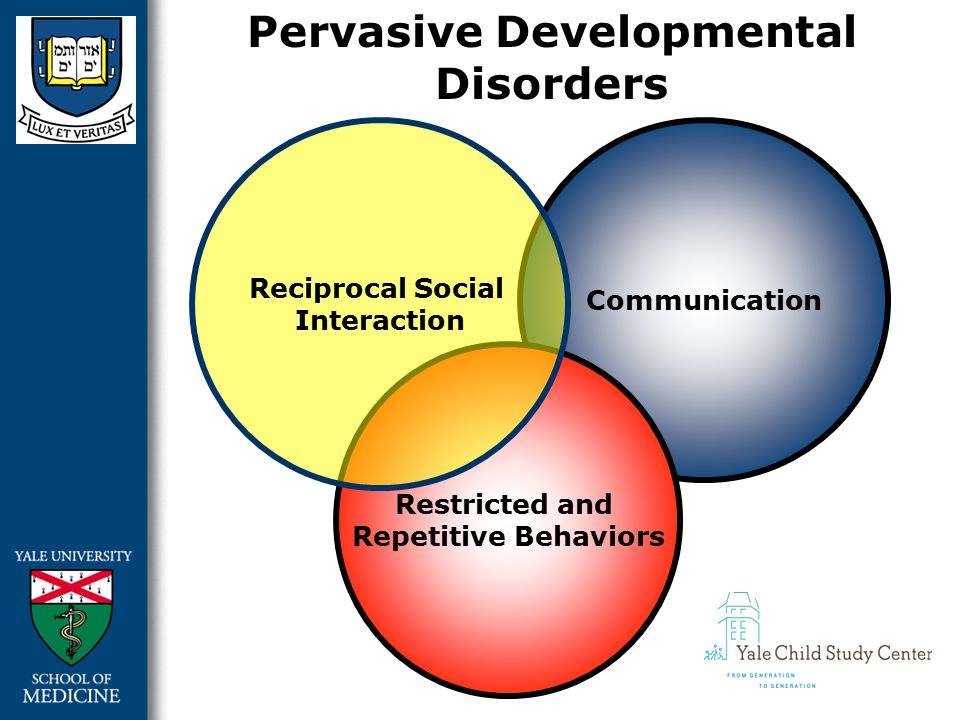

Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) are a group of different conditions. All of them are characterized by certain difficulties with social interaction and communication. Other features include atypical patterns of action and behaviors, such as difficulty moving from one activity to another, focus on details, and unusual responses to external stimuli.

All of them are characterized by certain difficulties with social interaction and communication. Other features include atypical patterns of action and behaviors, such as difficulty moving from one activity to another, focus on details, and unusual responses to external stimuli.

The abilities and needs of people with autism can vary and change over time. Some people with autism are able to live independent and productive lives, while others become severely disabled and require lifelong care and support. Autism often negatively affects educational or employment opportunities. In addition, for family members of people with autism, care and support responsibilities can often be a source of significant stress. Community attitudes and the level of support from local and national governments are important determinants of the quality of life of people with autism.

Signs of autism can be identified in early childhood, but the condition is often diagnosed at much later stages.

People with autism often have comorbid conditions and illnesses, including epilepsy, depression, anxiety, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, as well as behavioral problems such as sleep disturbances or self-harm. The level of intellectual abilities of people with autism varies in a wide range from severe cognitive impairment to a high level of intelligence.

Epidemiology

It is estimated that autism affects about 1 in 100 children worldwide (1). At the same time, we are talking about an average indicator, and the prevalence rates of autism recorded according to different studies vary widely. Nonetheless, according to some reputable controlled studies, the real numbers are much higher. The prevalence of autism in many low- and middle-income countries is unknown.

Causes

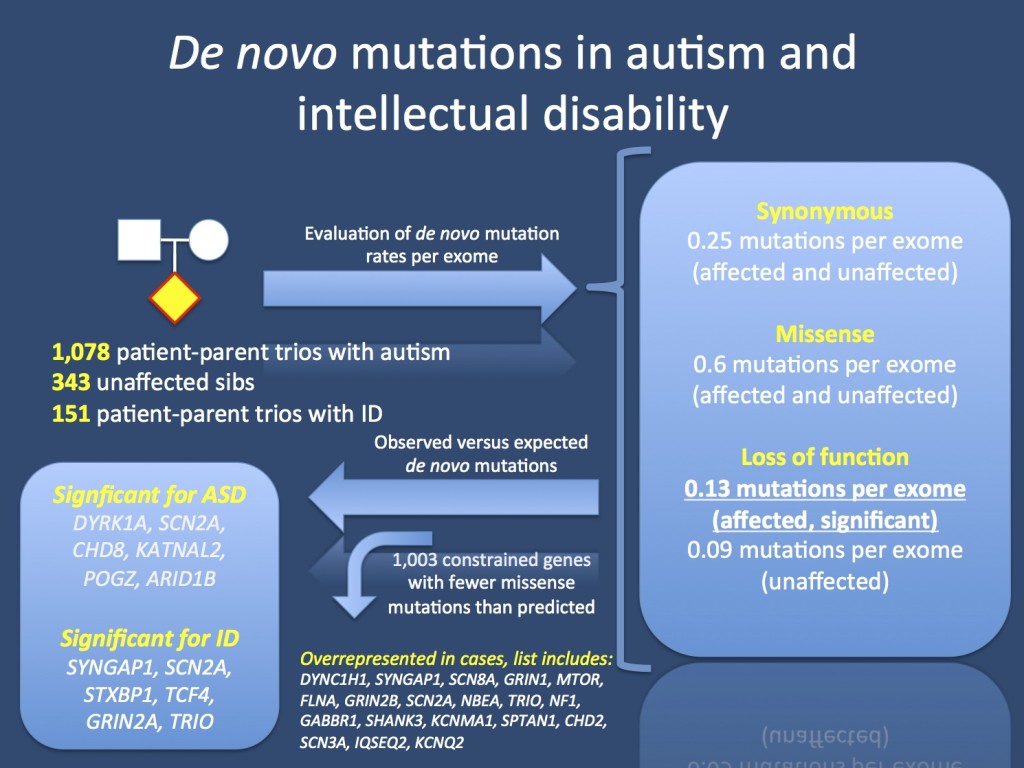

Available scientific evidence indicates many factors that may increase the likelihood of children developing autism, including environmental and genetic factors.

Available epidemiological data do not support a causal relationship between autism and measles, mumps and rubella vaccination. Past studies suggesting such a causal relationship have been many methodological problems were found (2), (3).

Similarly, there is no evidence that any childhood vaccine can increase the risk of developing autism. Evidence reviews on a potential association between the preservative thiomersal and aluminum adjuvants contained in inactivated vaccines and the risk of developing autism strongly suggest that vaccines do not lead to an increase in this risk.

Needs Assessment and Care Management

A range of interventions, from early childhood and throughout life, can contribute to the optimal development, well-being and quality of life of people with autism. Timely evidence-based psychosocial interventions at an early age can improve the ability of children with autism to communicate and interact effectively with others. It is recommended to monitor the development of children as part of the planned provision of medical care to mothers and children.

It is important that immediately after diagnosis, children, adolescents and adults diagnosed with autism and their caregivers have access to relevant information, referrals and practical support tailored to their individual needs. constantly changing needs and preferences.

The health care needs of people with autism are complex, requiring them to provide comprehensive services, including health promotion, care and rehabilitation services. Therefore, it is important to ensure cooperation with other sectors, in particular with the education system, employment and the social sector.

Interventions to help people with autism and other developmental disabilities should be planned and implemented with the participation of people with these conditions themselves. Caring for people with autism should be accompanied by local action. and at the level of society as a whole, in order to make the physical and social environment and relationships more accessible, inclusive and supportive.

Human rights

All people, including those with autism, have the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.

Yet people with autism often face stigma and discrimination: their health care and education rights are unfairly denied, and their opportunities to participate in society are limited.

People with autism may experience the same health problems as the rest of the population. In addition, they may have special health care needs related to autism and other related conditions. They can be are more vulnerable to chronic noncommunicable diseases associated with behavioral risk factors such as physical inactivity and poor diet, and are at greater risk of violence, injury and abuse.

People with autism, like the rest of the population, need affordable health services to meet general health needs, including health promotion and prevention services, as well as acute and chronic care. However less than in the general population, the level of satisfaction of the medical needs of people with autism is at a lower level. These people are also more vulnerable in humanitarian emergencies. One of the common barriers is the insufficient level of knowledge and understanding of the specifics of autism by medical professionals.

These people are also more vulnerable in humanitarian emergencies. One of the common barriers is the insufficient level of knowledge and understanding of the specifics of autism by medical professionals.

WHO Resolution on Autism Spectrum Disorders

In May 2014, the Sixty-seventh World Health Assembly adopted a resolution on "Comprehensive and concerted efforts for the management of autism spectrum disorders", supported by over 60 countries.

The resolution calls on WHO to work with Member States and partner agencies to strengthen national capacity to address ASD and other developmental disabilities.

WHO activities

WHO and partners recognize the need to strengthen countries' capacity to promote the optimal health and well-being of all people with autism.

The main activities of WHO in this regard are:

- promoting the adoption of targeted measures by national governments to improve the quality of life of people with autism;

- develop recommendations for policies and action plans to address autism in the broader context of physical, mental, brain health and care for people with disabilities;

- help to empower healthcare professionals to provide appropriate and effective care for people with autism and achieve optimal health and well-being; and

- Promoting an inclusive and supportive environment for people with autism and other developmental disabilities and providing support to their caregivers.

WHO comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2030 and World Health Assembly Resolution WHA73.10 "Global action against epilepsy and other neurological disorders" contain calling on countries to address significant gaps in the early detection, care, treatment and rehabilitation of people with mental and neurodevelopmental disorders, including and autism. The resolution also calls on countries to take action to meet the social, economic, educational and other needs of people living with mental and neurological disorders and their families, and to develop surveillance and related research activities.

Reference literature

(1) Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Zeidan J et al. Autism Research 2022 March.

(2) Wakefield's affair: 12 years of uncertainty whereas no link between autism and MMR vaccine has been proven. Maisonneuve H, Floret D. Presse Med. 2012 Sep; French https://pubmed.