Social anxiety disorder pictures

Social Anxiety Disorder Explained (DSM-5 In Picture Form) — Insights of a Neurodivergent Clinician

tag

DSM-5 in Pictures

Written By Megan Anna Neff

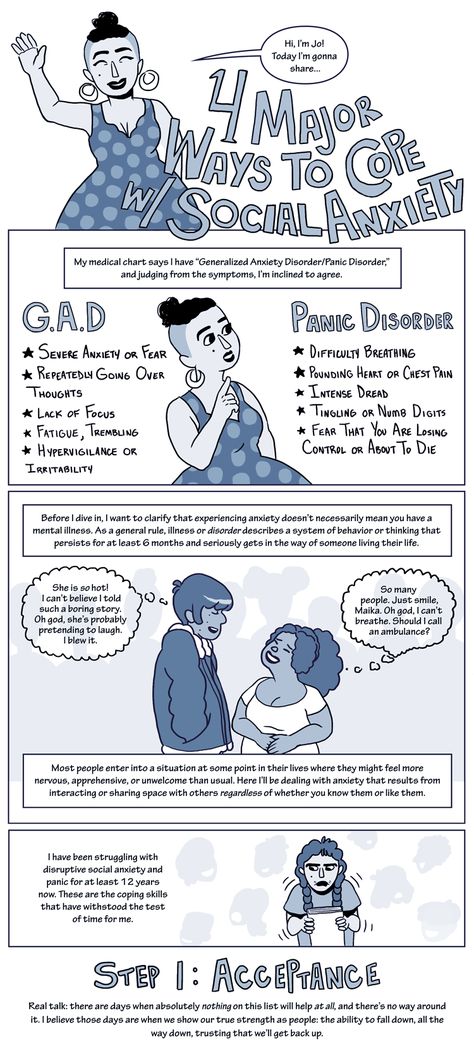

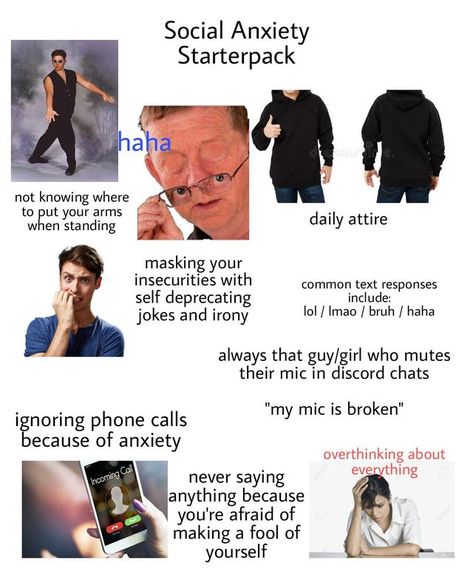

I am creating a new series over on Instagram and here on my blog. I will be taking commonly diagnosed conditions and reviewing the DSM-5 criteria in picture form. Since website content can get a bit choppy, you can also download a high-quality PDF of these images over in my shop. Before diving into the DSM-5 criteria for social anxiety, let’s first go over some basic information and disclaimers.

Disclaimers, FAQs, and Basic Information on the DSM-5

Why am I creating this Series: Glad you asked; here is why:

1). Like many Neurodivergent people, I can't understand a thing unless it's visual. I want to help break down the complexity of diagnosis codes through images.

2). The mental health world can be overly mysterious and opaque. As someone who regularly assesses and diagnoses people, I want to increase the transparency of what goes into diagnoses and assessments. Reducing uncertainty is helpful for all people but particularly important for Autistic people.

What this is: Educational

What this isn't: A substitute for medical advice, a diagnostic tool

A word on language: I use the language of the DSM for educational purposes; much of this is pathological by nature. It doesn't mean I agree with all the wording (in fact, I do not!).

What do A, B, and C mean? The DSM is broken into different criteria buckets. While a person doesn't need to have all symptoms of each criterion, they typically need to have all criteria met (A, B, C, etc..) to be diagnosed.

What about international people? The DSM-5 is based in the United States (the Psychological Association of America puts it out). However, the criteria are very similar to the ICD, which is used globally and broadly in medical settings.

However, the criteria are very similar to the ICD, which is used globally and broadly in medical settings.

Social Anxiety Disorder (Social Phobia) DSM-5 Criteria

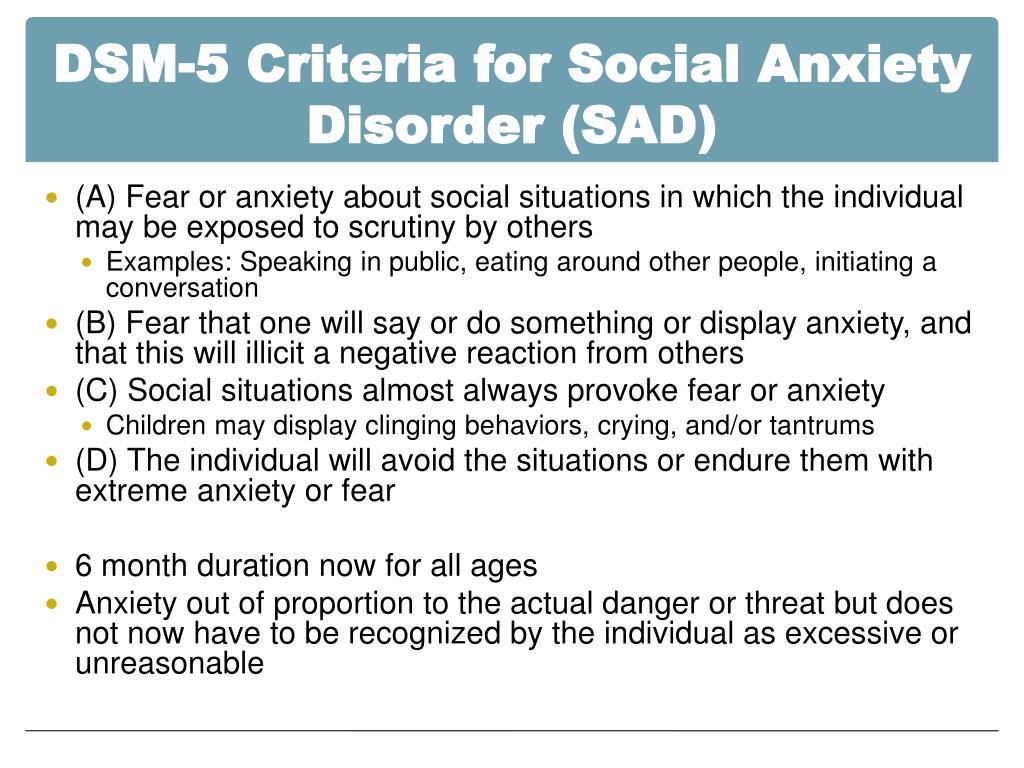

There are 10 different buckets of criteria that need to be met for a person to be diagnosed with social anxiety. In the DSM-5 these are categorized from A-J.

Criteria A for Social Anxiety Disorder

Criteria A for Social Anxiety Disorder

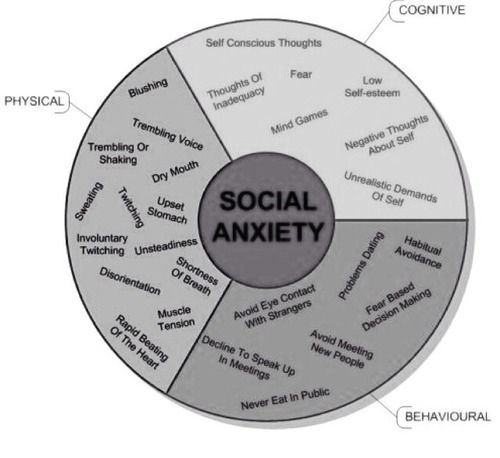

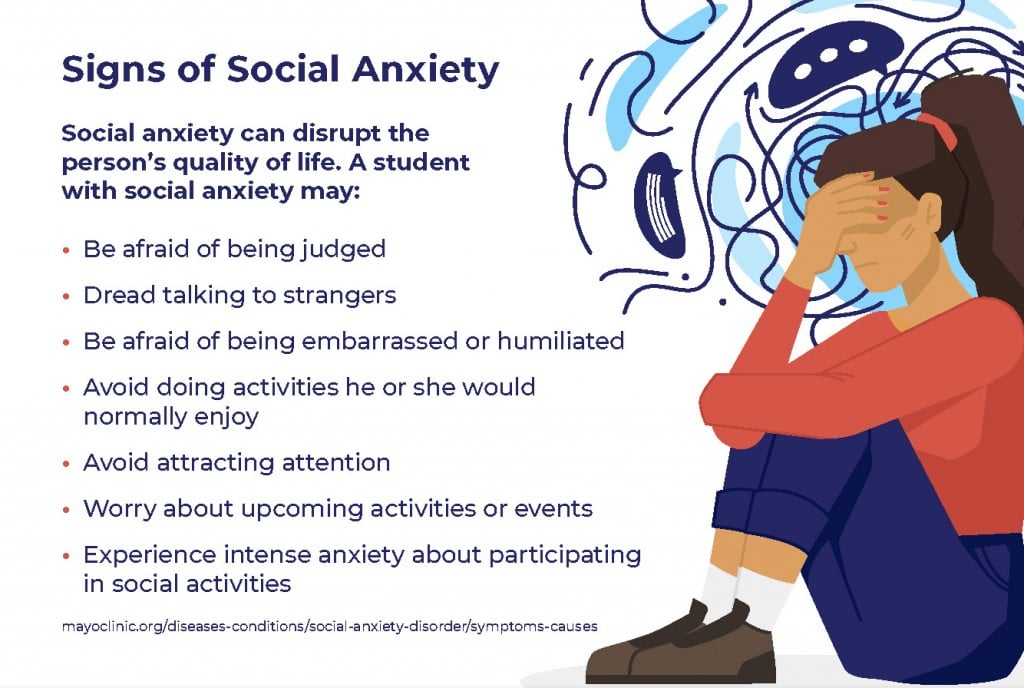

Criteria A for social anxiety includes: "Marked fear or anxiety about one or more social situations in which the individual is exposed to possible scrutiny by others" (The DSM, 2013).

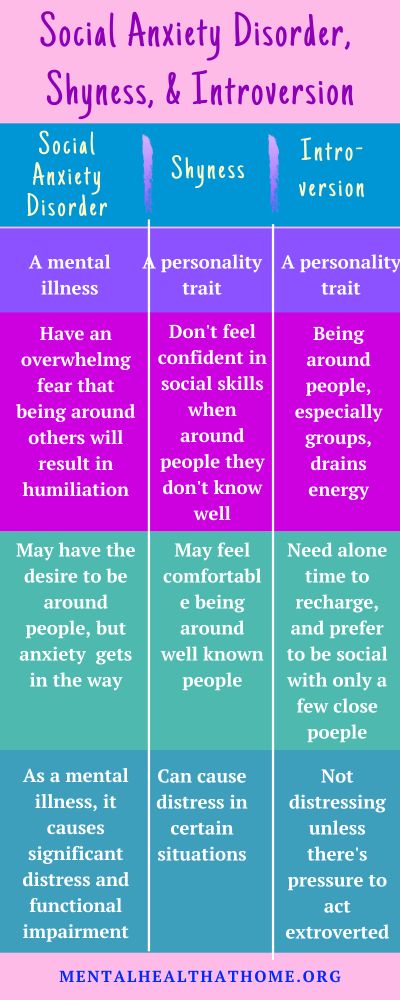

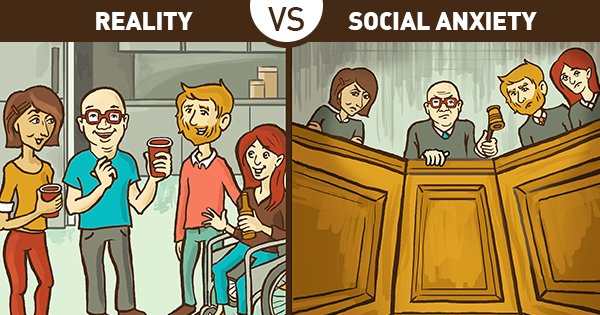

This is an important part of social anxiety to understand. Social anxiety is not the same as simply being anxious around others or feeling sensory overloaded. Rather the intense fear of being ridiculed, scrutinized, and embarrassed drives much of the anxiety.

Common experiences that can cause anxiety include situations where the person will be in the spotlight (such as giving a presentation or speech), having a conversation with someone (particularly someone new or unknown), and situations where they are observed by others (such as eating or drinking in public spaces).

***One specifier for social anxiety is if it is only present when performing or speaking in public. This can still be diagnosed as social anxiety with the specifier of performing only. This form of social anxiety is typically mostly causing impairment in a person’s professional life (for example, performers, musicians, athletes, etc.).

Criteria B for Social Anxiety Disorder

Criteria B for Social Anxiety Disorder

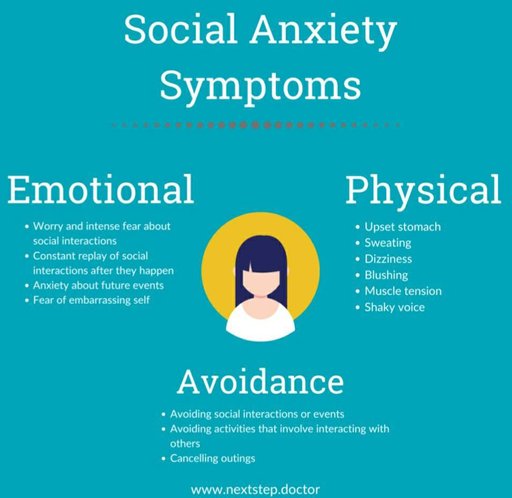

Criteria B for social anxiety includes: "The individual fears that he or she will act in a way or show anxiety symptoms that will be negatively evaluated." Examples include things such as:

1) Fear of being humiliated or embarrassed

2) Fear of situations where one may be judged negatively

3) Fear of physical manifestations of anxiety (blushing, sweating, trembling, or a shaky voice)

4) Fear of offending others

5) Fear of being Rejected

Here the person is highly anxious that others will perceive them as "anxious, weak, crazy, stupid, boring, intimidating, dirty, or unlikable" (DSM-5, 2013). The person is often particularly nervous about showing their anxiety symptoms through blushing, trembling, sweating, stumbling over one's words, or staring, which will lead to being rejected or negatively evaluated.

The person is often particularly nervous about showing their anxiety symptoms through blushing, trembling, sweating, stumbling over one's words, or staring, which will lead to being rejected or negatively evaluated.

Those from more collectivistic cultures are more prone to worry that they will accidentally offend others (through a gaze or by their outward signs of anxiety).

Criteria C and D for Social Anxiety Disorder

Criteria C and D for Social Anxiety Disorder

C. Social situations almost always provoke fear or anxiety.

Criteria C captures the pervasiveness of the experience. We aren’t talking about situational anxiety that comes and goes; we’re talking about anxiety that is persistent and present in many contexts.

D. The social situations are avoided or endured with intense fear or anxiety.

Avoidance and anxiety go hand and hand. When we experience anxiety, we often avoid the thing that triggers the anxiety (which then makes the anxiety worse, often referred to as the anxiety-avoidant loop). Criteria C and D capture this element of social anxiety. The person nearly always pushes through the avoidance but experiences intense fear and anxiety (criteria c), or they avoid these situations whenever possible (avoidance).

Criteria C and D capture this element of social anxiety. The person nearly always pushes through the avoidance but experiences intense fear and anxiety (criteria c), or they avoid these situations whenever possible (avoidance).

Criteria E for Social Anxiety Disorder

Criteria E for Social Anxiety Disorder

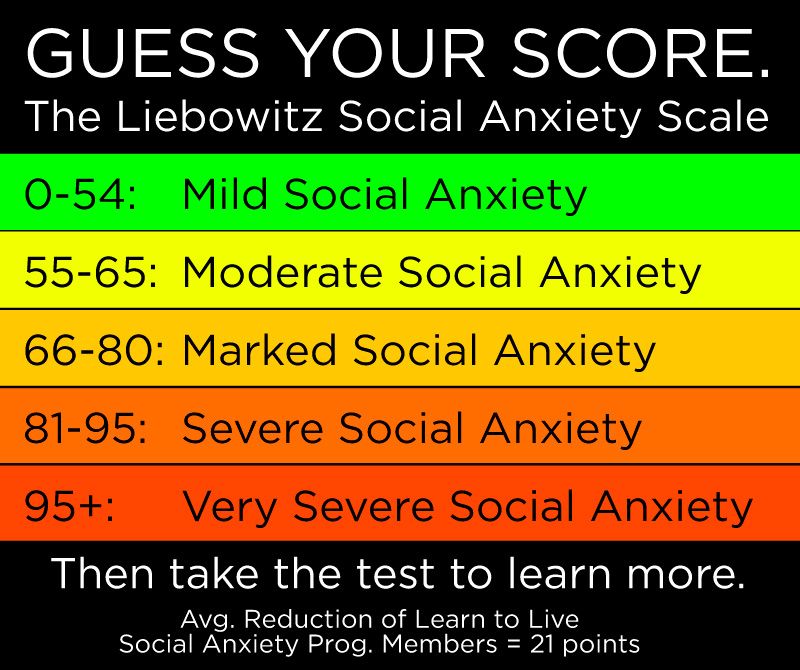

Criteria E is important for distinguishing situational or context-dependent anxiety that is justified based on risk or sociocultural factors from anxiety that is excessive in nature. For a person to be diagnosed with social anxiety disorder, the anxiety needs to be excessive and persistent.

One of the ways to discern if the anxiety is excessive is to look at whether or not it is proportional to the situation. This is a critical consideration, particularly when working with people with marginalized identities.

This is an area where BIPOC, Trans, and Neurodivergent people are often misunderstood. When your skin color or gender can be a source of danger and harm, the anxiety associated with many social situations is proportional to the risk. Or when you've spent a lifetime of not fitting in and not understanding why (re autism), the anxiety may be proportional to the context and past experiences.

When your skin color or gender can be a source of danger and harm, the anxiety associated with many social situations is proportional to the risk. Or when you've spent a lifetime of not fitting in and not understanding why (re autism), the anxiety may be proportional to the context and past experiences.

Personally, in these situations, I prefer to frame the symptoms in the context of society vs. locating the disorder within the person. The person doesn't have a social anxiety disorder, rather, the sickness is in the society, and they are having an appropriate response to navigating a racist, transphobic, homophobic or ableist world.

Criteria F for Social Anxiety Disorder

Criteria F for Social Anxiety Disorder

For the majority of DSM-5 diagnoses, a specific amount of time needs to have passed before a person reaches the threshold of diagnosis.

For example, a person must experience two weeks of depressive symptoms before a diagnosis of major depression is given, 30 days of acute stress symptoms before a diagnosis of PTSD, and so on).

For social anxiety disorder, there needs to be a pattern of anxiety observed over the last six months.

This may seem arbitrary, however, having time requirements is generally helpful as it helps to tease out the difference between a major anxiety or depressive disorder and situational anxiety or situational mood symptoms (these situations often fall into the category of adjustment disorders).

Criteria G Social Anxiety Disorder

Criteria G for Social Anxiety Disorder

While I am a huge fan of the rise of mental health awareness and education happening in places like TikTok and Instagram, there are also some drawbacks. When a checklist of symptoms is put out, or someone shares a 60-second clip of their experience, it can be easy to relate to these experiences and start identifying with many of these conditions.

In some cases, this is accurate, and the person is finally finding language to understand their experience! However, at other times, a person may over-identify with these simplified checklists.

For example, most people likely experience occasional social anxiety. However, for a diagnosis, the symptoms need to cause either A) significant suffering or B) impairment in school, work, relationships, or another area of a person's life. The difference between fleeting social anxiety and social anxiety disorder largely comes down to this element—how much is it impacting the person's life?

I appreciate the DSM says "clinically significant distress" or “impairment.” This takes into account people with high-functioning anxiety who may not be experiencing significant work or school struggles but whose mental and emotional health is struggling due to the intensity of their symptoms.

Criteria H, I, J for Social Anxiety Disorder

Criteria H, I, J for Social Anxiety Disorder

When we get to the last few criteria (for almost all DSM-5 diagnoses), we start talking about disqualifiers. By disqualifiers and rule-outs, I mean we are looking to ensure that the symptoms and experiences aren't better explained by another condition (another medical condition, mental health condition, substances, etc. ). In general, you want to diagnose less and better. By this, I mean if you can explain the person's symptoms in one diagnosis, that is preferred over providing 2 or 3 diagnoses.

). In general, you want to diagnose less and better. By this, I mean if you can explain the person's symptoms in one diagnosis, that is preferred over providing 2 or 3 diagnoses.

Let me give an example. In the case of PTSD, the person would likely meet the criteria for generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder (based on symptoms). However, these symptoms are best explained by PTSD, and it requires fewer diagnoses. So the person would be diagnosed with PTSD (not all three).

This is important as it helps guide the treatment. In the above example, it is assumed that as PTSD is treated, depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms would also improve. If they don't, it may be time to revisit and consider adding a depression diagnosis if it is lingering beyond the PTSD symptoms and treatment.

Many undiagnosed Autistic and ADHD people are diagnosed with social anxiety. If you like to learn more about the similarities and differences between social anxiety and autism, you can check out my brief e-book on it.

Megan Anna Neff

Behavioural and neural correlates of self-focused emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder

1. McRae K, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation. In: Sander D, Scherer KR, editors. Oxford companion to the affective sciences. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

2. Damasio A, Carvalho GB. The nature of feelings: evolutionary and neurobiological origins. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:143–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Ochsner KN, Silvers JA, Buhle JT. Functional imaging studies of emotion regulation: a synthetic review and evolving model of the cognitive control of emotion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1251:E1–E24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Gross JJ. Emotion regulation: affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology. 2002;39:281–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Walter H, Von Kalckreuth A, Schardt DM, et al. The temporal dynamics of voluntary emotion regulation. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6726. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

The temporal dynamics of voluntary emotion regulation. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6726. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Kalisch R, Wiech K, Critchley H. Anxiety reduction through detachment: subjective, physiological, and neural effects. J Cogn Neurosci. 2005;17:874–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Morrison AS, Heimberg RG. Social anxiety and social anxiety disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:249–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Kessler RC, Chiu WT. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Bishop SJ. Neurocognitive mechanisms of anxiety: an integrative account. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:307–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Hattingh CJ, Ipser J, Tromp SA, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging during emotion recognition in social anxiety disorder: an activation likelihood meta-analysis. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:347. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:347. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Werner K, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation and psychopathology: a conceptual framework. In: Kring AM, Sloan DM, editors. Emotion regulation and psychopathology: a transdiagnostic approach to etiology and treatment. New York (NY): Guildford; 2004. pp. 13–37. [Google Scholar]

12. Mennin DS, Heimberg RG, Turk CL, et al. Preliminary evidence for an emotion dysregulation model of generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:1281–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Goldin PR, Manber T, Hakimi S, et al. Neural bases of social anxiety disorder: emotional reactivity and cognitive regulation during social and physical threat. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:170–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Goldin PR, Manber-Ball T, Werner K, et al. Neural mechanisms of cognitive reappraisal of negative self-beliefs in social anxiety disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:1091–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Blair KS, Blair RJR. A cognitive neuroscience approach to generalized anxiety disorder and social phobia. Emotion Review. 2012;4:133–8. [Google Scholar]

Blair KS, Blair RJR. A cognitive neuroscience approach to generalized anxiety disorder and social phobia. Emotion Review. 2012;4:133–8. [Google Scholar]

16. Alden LE, Regambal MJ. Social anxiety, social anxiety disorder, and the self. In: Hofmann SG, Di Bartolo PM, editors. Social anxiety. 2nd ed. Waltham (MA): Academic Press; 2010. pp. 423–45. [Google Scholar]

17. Clark DM, Wells A. A cognitive model of social phobia. In: Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DR, et al., editors. Social phobia: diagnosis, assessment and treatment. New York (NY): Guilford; 1995. pp. 69–93. [Google Scholar]

18. Rapee R, Heimberg R. A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:741–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Stangier U, Fydrich T. Das störungskonzept der sozialen phobie oder der sozialen angststörung. In: Stangier U, Fydrich T, editors. Soziale phobie — soziale angststörungen. Göttingen (DE): Hogrefe; 2002. pp. 10–33. [Google Scholar]

20. Bögels SM. Task concentration training versus applied relaxation, in combination with cognitive therapy, for social phobia patients with fear of blushing, trembling, and sweating. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:1199–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bögels SM. Task concentration training versus applied relaxation, in combination with cognitive therapy, for social phobia patients with fear of blushing, trembling, and sweating. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:1199–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Hofmann SG, Moscovitch Da, Kim H-J, et al. Changes in self-perception during treatment of social phobia. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:588–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Shah SG, Klumpp H, Angstadt M, et al. Amygdala and insula response to emotional images in patients with generalized social anxiety disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2009;34:296–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Etkin A, Wager TD. Functional neuroimaging of anxiety: a meta-analysis of emotional processing in PTSD, social anxiety disorder, and specific phobia. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1476–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Ziv M, Goldin PR, Jazaieri H, et al. Is there less to social anxiety than meets the eye? Behavioral and neural responses to three socio-emotional tasks. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord. 2013;3:5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Biol Mood Anxiety Disord. 2013;3:5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Quadflieg S, Mohr A, Mentzel H-J, et al. Modulation of the neural network involved in the processing of anger prosody: the role of task-relevance and social phobia. Biol Psychol. 2008;78:129–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Sripada CS, Angstadt M, Banks S, et al. Functional neuroimaging of mentalizing during the trust game in social anxiety disorder. Neuroreport. 2009;20:984–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Amir N, Klumpp H, Elias J, et al. Increased activation of the anterior cingulate cortex during processing of disgust faces in individuals with social phobia. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:975–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Gentili C, Gobbini MI, Ricciardi E, et al. Differential modulation of neural activity throughout the distributed neural system for face perception in patients with social phobia and healthy subjects. Brain Res Bull. 2008;77:286–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Brühl AB, Herwig U, Delsignore A, et al. General emotion processing in social anxiety disorder: neural issues of cognitive control. Psychiatry Res. 2013;212:108–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brühl AB, Herwig U, Delsignore A, et al. General emotion processing in social anxiety disorder: neural issues of cognitive control. Psychiatry Res. 2013;212:108–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Blair KS, Geraci M, Smith BW, et al. Reduced dorsal anterior cingulate cortical activity during emotional regulation and top-down attentional control in generalized social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and comorbid generalized social phobia/generalized anxiety disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:476–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington (DC): The Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

33. Wittchen H-U, Wunderlich U, Gruschwitz S, et al. Strukturiertes klinisches interview für DSM-IV. Achse I: psychische störungen. Göttingen (DE): Hogrefe; 1997. [Google Scholar]

Göttingen (DE): Hogrefe; 1997. [Google Scholar]

34. Gast U, Oswald P, Zündorf F, et al. Das strukturierte klinische interview für DSM-IV-dissoziative störungen. Interview und manual. Göttingen (DE): Hogrefe; 2000. [Google Scholar]

35. Mombour W, Zaudig M, Berger P, et al. International Personality Disorder Examination ICD-10 Modul. Deutschsprachige Ausgabe Im Auftrag der WHO. Göttingen (DE): Hogrefe; 1996. [Google Scholar]

36. Stangier U, Heidenreich T. Die Liebowitz Soziale Angst-Skala (LSAS) Göttingen (DE): Hogrefe; 2003. [Google Scholar]

37. Hautzinger M, Keller F, Kühner C. Beck Depressions-Inventar (BDI-II) Frankfurt (DE): Pearson Assessment; 2006. [Google Scholar]

38. Laux L, Glanzmann P, Schaffner P, et al. STAI–Das State-Trait-Angstinventar. Göttingen (DE): Beltz; 1981. [Google Scholar]

39. Franz M, Schneider C, Schäfer R, et al. [Factoral structure and psychometric properties of the German version of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) in psychosomatic patients]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2001;51:48–55. [article in German] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2001;51:48–55. [article in German] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Reitan RM. The relation of the Trail Making Test to organic brain damage. J Consult Psychol. 1955;19:393–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Hoyer J. [Dysfunctional and Functional Self-Consciousness (DFS): theoretical concept, reliability, and validity]. Diagnostica. 2000;46:140–8. [article in German] [Google Scholar]

42. Ströhle G, Nachtigall C, Michalak J, et al. Die Erfassung von Achtsamkeit als mehrdimensionales Konstrukt. Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie. 2010;39:1–12. [Google Scholar]

43. Abler B, Kessler H. Emotion Regulation Questionnaire — Eine deutschsprachige Fassung des ERQ von Gross und John. Diagnostica. 2009;55:144–52. [Google Scholar]

44. Paulus C. Der Saarbrücker Persönlichkeitsfragebogen SPF(IRI) zur Messung von Empathie — Psychometrische Evaluation der deutschen Version des Interpersonal Reactivity Index. Saarbrücken (DE): Universität des Saarlandes; 2009. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

45. Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. International Affective Picture System (IAPS): affective ratings of pictures and instruction manual. Gainesville (FL): University of Florida; 2008. Report no.: A-8. [Google Scholar]

46. Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15:273–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Brühl AB, Rufer M, Delsignore A, et al. Neural correlates of altered general emotion processing in social anxiety disorder. Brain Res. 2011;1378:72–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Turk CL, Heimberg RG, Luterek JA, et al. Emotion dysregulation in generalized anxiety disorder: a comparison with social anxiety disorder. Cognit Ther Res. 2005;29:89–106. [Google Scholar]

49. Hsu M, Bhatt M, Adolphs R, et al. Neural systems responding to degrees of uncertainty in human decision-making. Science. 2005;310:1680–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Science. 2005;310:1680–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Kanske P, Heissler J, Schönfelder S, et al. How to regulate emotion? Neural networks for reappraisal and distraction. Cereb Cortex. 2010;21:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Adolphs R. What does the amygdala contribute to social cognition? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1191:42–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Van Overwalle F. Social cognition and the brain: a meta-analysis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:829–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Blanke O. Multisensory brain mechanisms of bodily self-consciousness. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:556–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Diekhof EK, Geier K, Falkai P, et al. Fear is only as deep as the mind allows: a coordinate-based meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies on the regulation of negative affect. Neuroimage. 2011;58:275–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Müller VI, Habel U, Derntl B, et al. Incongruence effects in cross-modal emotional integration. Neuroimage. 2011;54:2257–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Neuroimage. 2011;54:2257–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Koenigsberg HW, Fan J, Ochsner KN, et al. Neural correlates of using distancing to regulate emotional responses to social situations. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48:1813–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Roy AK, Shehzad Z, Margulies DS, et al. Functional connectivity of the human amygdala using resting state fMRI. Neuroimage. 2009;45:614–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Stein JL, Wiedholz LM, Bassett DS, et al. A validated network of effective amygdala connectivity. Neuroimage. 2007;36:736–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Damasio A, Damasio H, Tranel D. Persistence of feelings and sentience after bilateral damage of the insula. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23:833–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Feinstein JS, Buzza C, Hurlemann R, et al. Fear and panic in humans with bilateral amygdala damage. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:270–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12 Signs of an Anxiety Disorder - Lifehacker

September 20, 2017 Health

Some disorders in the work of the psyche pretend to be ordinary phenomena. An anxiety disorder is one of those, but that doesn't mean it shouldn't be treated.

An anxiety disorder is one of those, but that doesn't mean it shouldn't be treated.

Anxiety is an emotion that all people experience when they are nervous or afraid of something. It’s unpleasant to be “on your nerves” all the time, but what can you do if life is like this: there will always be a reason for anxiety and fear, you need to learn to keep your emotions under control, and everything will be fine. In most cases, this is exactly the case.

It's okay to be anxious. Sometimes it’s even helpful: when we worry about something, we pay more attention to it, work harder, and generally achieve better results.

But sometimes anxiety goes beyond reasonable limits and interferes with life. And this is already an anxiety disorder - a condition that can ruin everything and which requires special treatment.

Why anxiety disorders appear

As with most mental disorders, no one can say for sure why anxiety clings to us: so far too little is known about the brain to speak with confidence about the causes. Several factors are most likely to blame, from ubiquitous genetics to traumatic experiences.

Several factors are most likely to blame, from ubiquitous genetics to traumatic experiences.

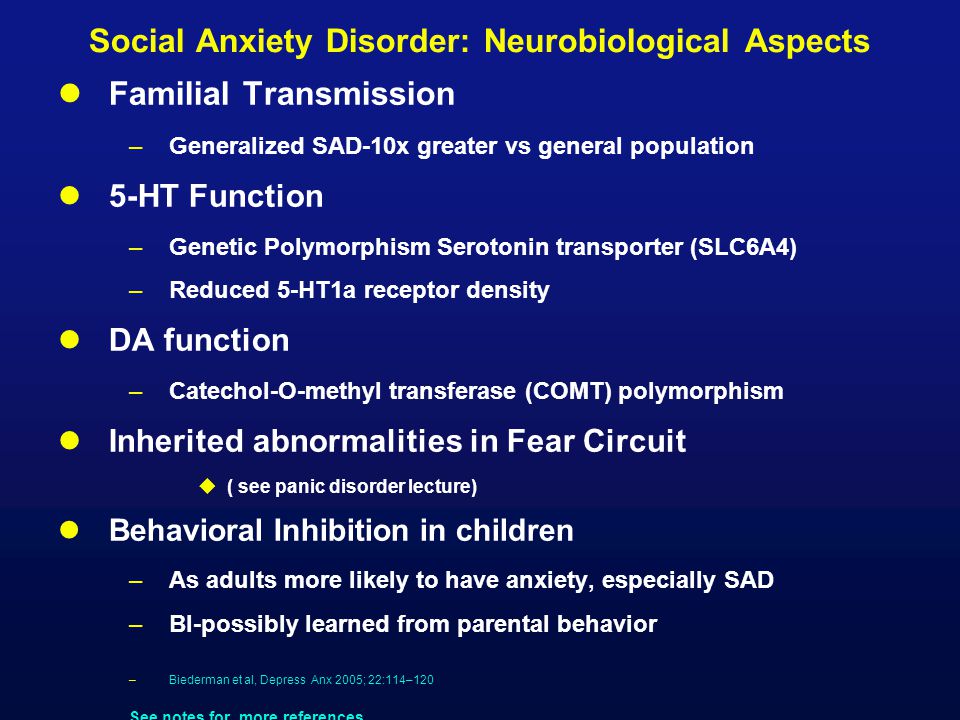

For some, anxiety appears due to the excitation of certain parts of the brain, for some, the hormones - serotonin and norepinephrine are acting up, and for some, the disorder occurs as a load of other diseases, and not necessarily mental ones.

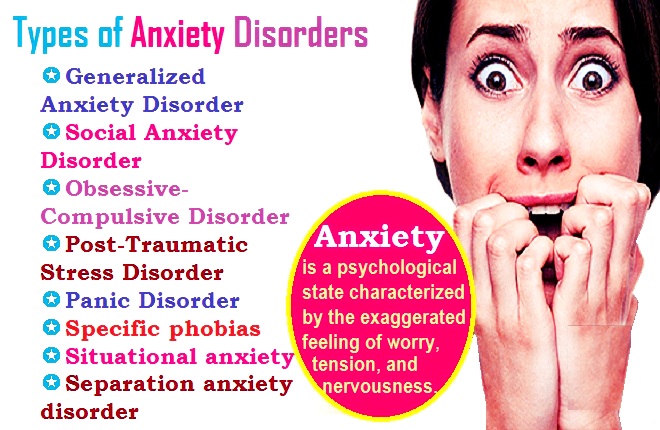

What is an anxiety disorder

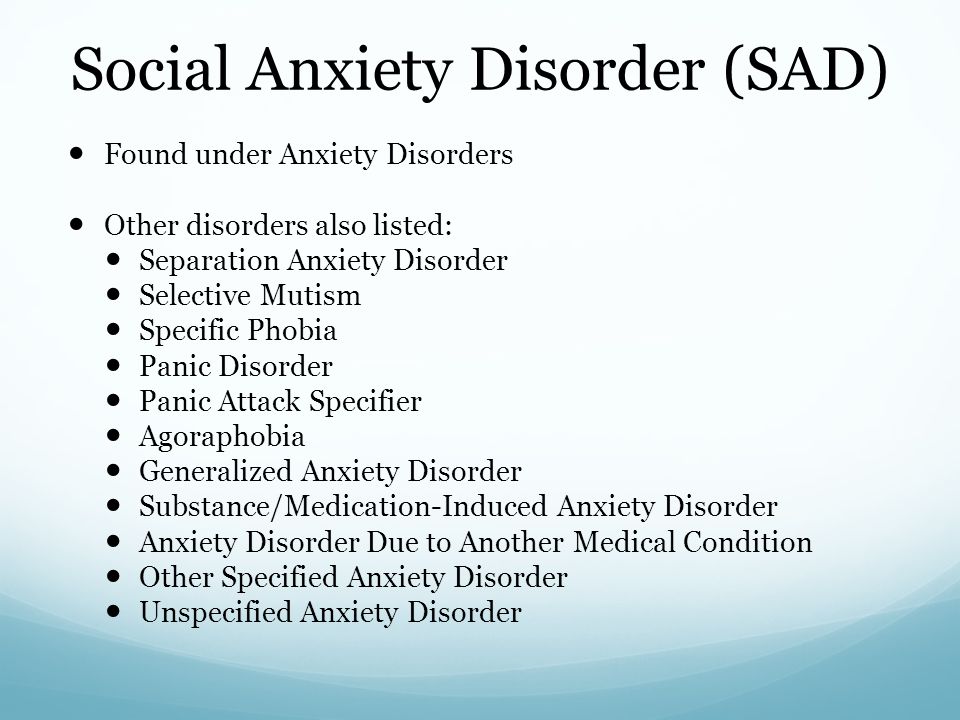

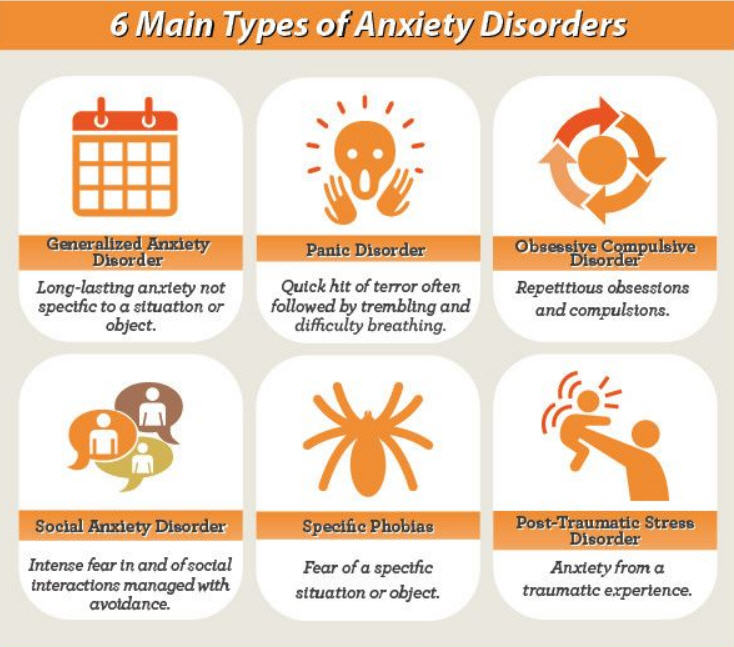

Anxiety disorders include several groups of diseases at once.

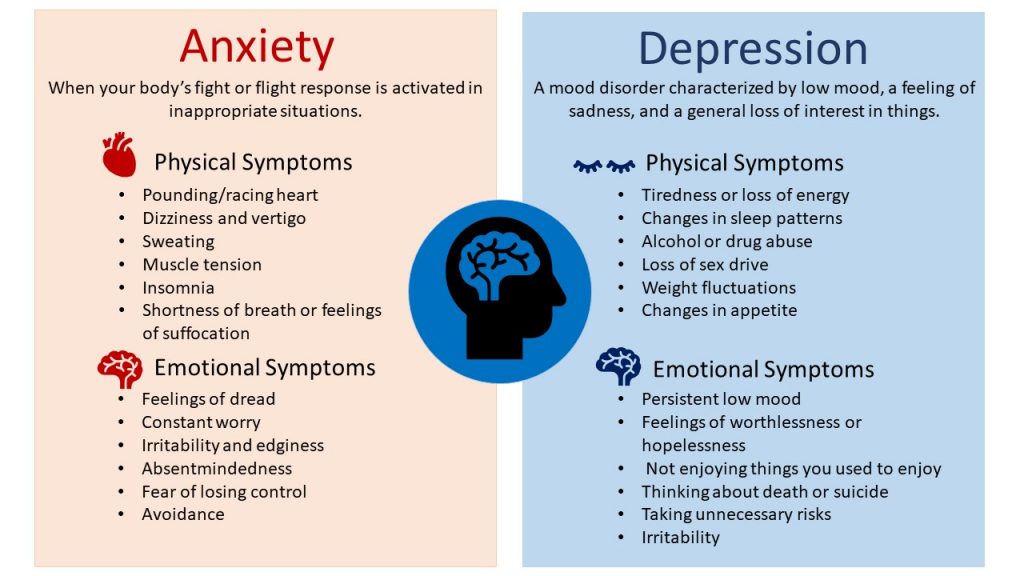

- Generalized anxiety disorder . This is the case when anxiety does not appear because of exams or the upcoming acquaintance with the parents of a loved one. Anxiety comes by itself, it does not need a reason, and the experiences are so strong that they do not allow a person to perform even simple daily activities.

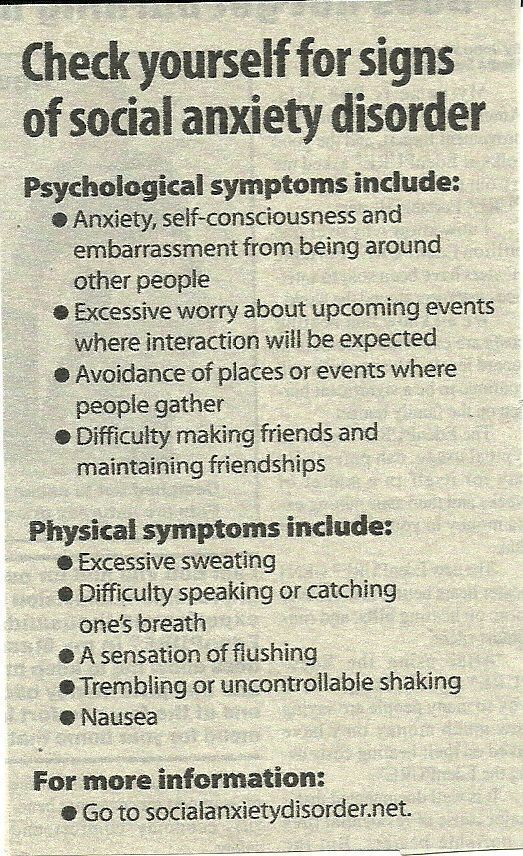

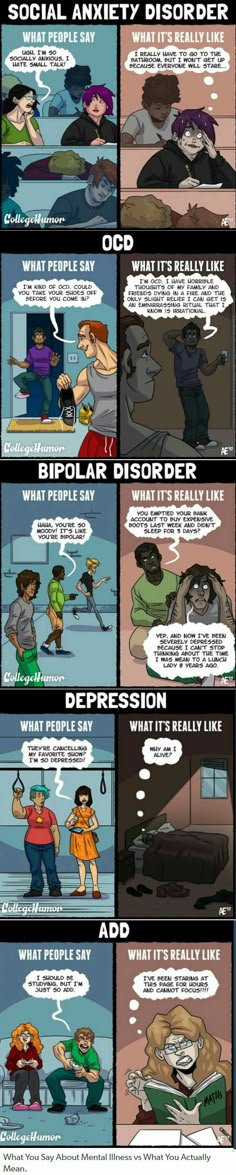

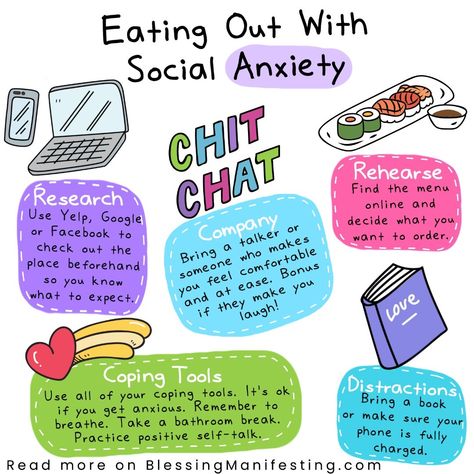

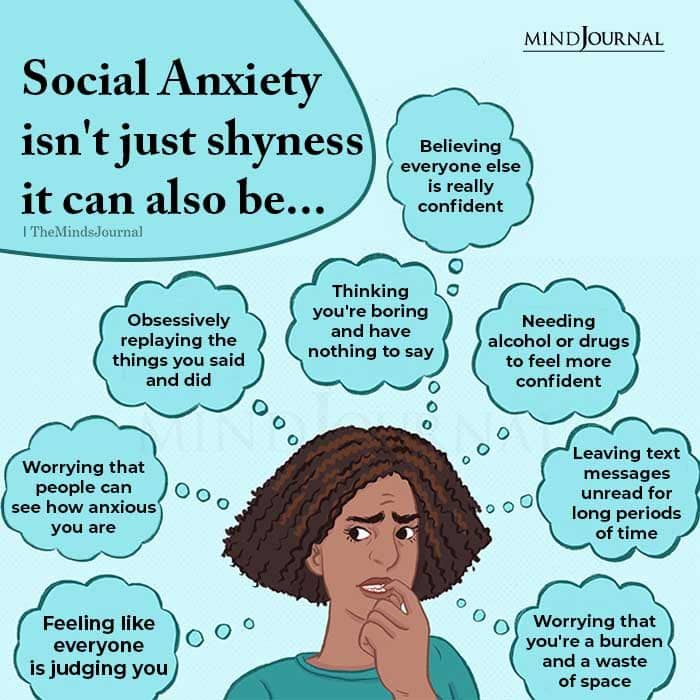

- Social anxiety disorder . Fear that prevents being among people. Someone is afraid of other people's assessments, someone is afraid of other people's actions. Be that as it may, it interferes with studying, working, even going to the store and saying hello to neighbors.

- Panic disorder . People with this disease experience panic attacks: they are so scared that sometimes they cannot take a step. The heart beats at a frantic speed, it gets dark in the eyes, there is not enough air. These attacks can come at the most unexpected moment, and sometimes because of them a person is afraid to leave the house.

- Phobias . When a person is afraid of something specific.

In addition, anxiety disorder often occurs in combination with other problems: bipolar or obsessive-compulsive disorder or depression.

How to understand that this is a disorder

The main symptom is a constant feeling of anxiety, which lasts for at least six months, provided that there is no cause for nervousness or they are insignificant, and emotional reactions are disproportionately strong. This means that anxiety changes life: you refuse work, projects, walks, meetings or acquaintances, some activity just because you worry too much.

Other symptoms that hint that something is wrong:

- constant fatigue;

- insomnia;

- constant fear;

- inability to concentrate;

- inability to relax;

- trembling in the hands;

- irritability;

- dizziness;

- palpitations, although there are no cardiac pathologies;

- excessive sweating;

- pain in the head, stomach, muscles - despite the fact that doctors do not find any violations.

There is no exact test or analysis by which to identify an anxiety disorder, because anxiety cannot be measured or touched. The decision on the diagnosis is made by a specialist who looks at all the symptoms and complaints.

Because of this, there is a temptation to go to extremes: either to diagnose yourself with a disorder when a black streak just began in life, or not to pay attention to your condition and scold your weak-willed character, when, due to fear, an attempt to go out into the street turns into feat.

Do not get carried away and confuse constant stress with constant anxiety.

Stress is a response to a stimulus. For example, on a call from a dissatisfied customer. When the situation changes, the stress goes away. And anxiety can remain - this is a reaction of the body that occurs even if there is no direct effect. For example, when an incoming call comes from a regular customer who is happy with everything, but picking up the phone is still scary. If the anxiety is so strong that any phone call is torture, then this is already a disorder.

No need to hide your head in the sand and pretend that everything is fine when constant stress interferes with life.

It is not customary to go to the doctor with such problems, and anxiety is often confused with suspiciousness and even cowardice, and being a coward in society is a shame.

If a person shares his fears, he is more likely to receive advice to pull himself together and not become limp than an offer to find a good doctor. The trouble is that it will not be possible to overcome the disorder with a powerful effort of will, just as it will not be possible to cure tuberculosis by meditation.

The trouble is that it will not be possible to overcome the disorder with a powerful effort of will, just as it will not be possible to cure tuberculosis by meditation.

How to treat anxiety

Chronic anxiety is treated like other mental disorders. For this, there are psychotherapists who, contrary to popular myths, do not just talk to patients about a difficult childhood, but help to find such techniques and techniques that really improve the condition.

Someone will feel better after a few conversations, someone will be helped by pharmacology. The doctor will help you review your lifestyle, find the reasons why you are nervous a lot, assess how severe the symptoms are and whether you need to take medication.

If you still think you don't need a therapist, try taming your anxiety yourself.

1. Find the cause

Analyze what you worry about most and most often, and try to eliminate this factor from your life. Anxiety is a natural mechanism that is needed for our own safety. We are afraid of something dangerous that can harm us.

We are afraid of something dangerous that can harm us.

Maybe if you are constantly shaking with fear of the authorities, it is better to change jobs and relax? If you succeed, then your anxiety is not caused by a disorder, you don’t need to treat anything - live and enjoy life. But if it is not possible to isolate the cause of anxiety, then it is better to seek help.

2. Exercise regularly

There are many blind spots in the treatment of mental disorders, but researchers agree on one thing: regular exercise really helps keep the mind in order.

3. Let the brain rest

The best thing is to sleep. Only in a dream does the brain overloaded with fears relax, and you get a break.

4. Learn to slow down the imagination with work

Anxiety is a reaction to something that hasn't happened. It is the fear of what might happen. In fact, anxiety is only in our head and is completely irrational. Why is it important? Because counteracting anxiety is not peace, but reality.

While all sorts of horrors happen in the anxious imagination, in reality everything goes on as usual, and one of the best ways to turn off the constantly itchy fear is to return to the present, to the current tasks.

For example, to keep your head and hands busy with work or sports.

5. Quit smoking and drinking

When the body is already a mess, it is at least illogical to shake the delicate balance with substances that affect the brain.

6. Learn relaxation techniques

The rule “the more the better” applies here. Learn breathing exercises, look for relaxing yoga poses, try music or even ASMR, drink chamomile tea, or use lavender essential oil in the room. Everything in a row until you find several options that will help you.

Types of anxiety according to modern criteria

Anxiety is a part of our life. Humanity owes much of its survival to this feeling. However, sometimes it gets out of control, turning from an adaptive mechanism into a real hindrance that interferes with normal life. In such situations, anxiety may be an independent disorder, or it may be a symptom of another disease.

In such situations, anxiety may be an independent disorder, or it may be a symptom of another disease.

Normal anxiety is always situational, and its level is related to the severity of the circumstances.

Let's say a student didn't learn the tickets before the exam. Will he be worried? Probably. Will this feeling be similar to the anxiety of a mother whose child is late after school and does not answer the phone? Probably not. At the same time, with a change in the situation - the student passed the exam, the child finally picked up the phone - the anxious feeling disappears by itself.

How is pathological anxiety different?

First, it is not adequate to the situation. Imagine a student who studied perfectly all the time, learned all the tickets, but is still afraid that he will not pass. On the exam, this will not only not help, but also interfere. Secondly, such anxiety goes beyond the situation, that is, it becomes spilled over time. Months and even years go by like this. Interestingly, patients easily find something to worry about even in the absence of threats. If you often feel like you left the iron on or didn't lock the door, then you know what that means. Finally, pathological anxiety seriously reduces the quality of life. This happens in different directions: the quality of sleep worsens, concentration and shifting of attention decrease, and working capacity decreases.

Months and even years go by like this. Interestingly, patients easily find something to worry about even in the absence of threats. If you often feel like you left the iron on or didn't lock the door, then you know what that means. Finally, pathological anxiety seriously reduces the quality of life. This happens in different directions: the quality of sleep worsens, concentration and shifting of attention decrease, and working capacity decreases.

Anxious patients often experience so-called dysfunctional emotions: guilt, self-criticism, sadness, shame, anger, jealousy, and apathy. This fusion of negative experiences can be the cause of suicidal behavior [1]. Therefore, it is often a question not only of the quality of life, but also of its preservation.

It can be argued that the alarm includes several components:

- emotional: unpleasant experiences, fear, guilt, etc.;

- cognitive: disorders of attention, memory and thinking;

- bodily: sensations like a lump in the throat, tachycardia, etc.

- behavioral: increased irritability, avoidance of certain situations, etc.

Previously, some psychiatrists and neurologists used diagnoses like vegetative-vascular dystonia (VVD). Today, this approach is recognized as inaccurate: this very VSD can be a manifestation of a generalized anxiety disorder, or it can manifest itself in phobias, that is, very specific fears. It is the modern classification that we will adhere to further.

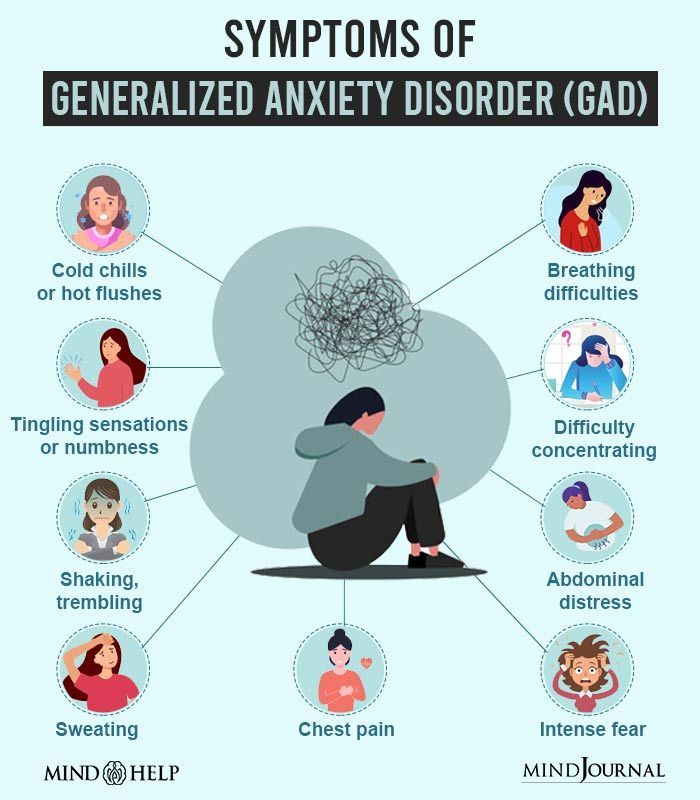

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

GAD is often based on unresolved psychological conflict or trauma and increased genetic anxiety. It is characterized not by specific anxiety when the cause is clear, but by constant, all-encompassing anxiety for a variety of reasons. It can be difficult for a person to establish the specific cause that triggered this condition.

Typical symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder:

- anxiety arises over a range of events and situations

- bodily manifestations (palpitations, sweating, tremors, dry mouth, difficulty breathing, lump in throat, nausea, digestive problems, dizziness, feeling unsteady, chills or fever, muscle pain, etc.

)

) - manifestations persist for six months or more

- habitual life is seriously disturbed

According to existing data, women are affected more than men on average. However, GAD usually occurs between 20 and 40 years of age.

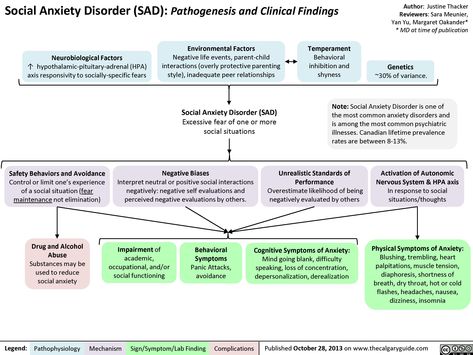

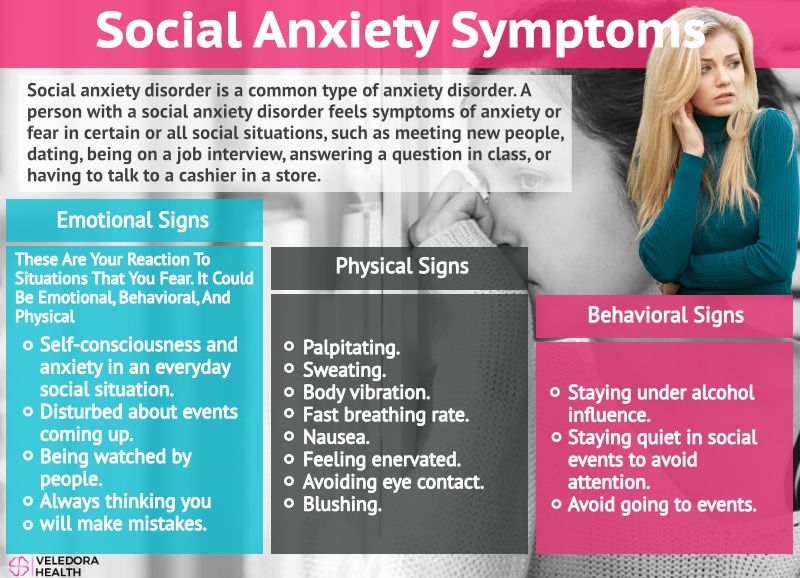

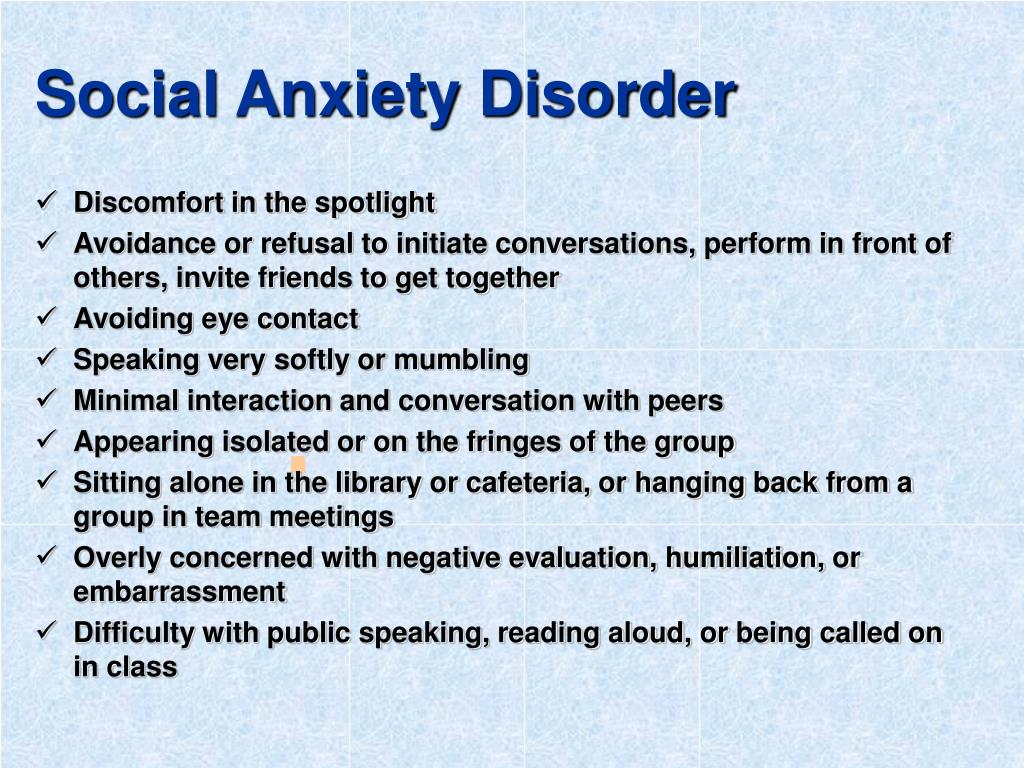

Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD)

SAD can be defined as a marked persistent fear of attention from other people. This leads to the fact that the patient has a strong feeling that everyone is looking only at him and also talking only about him: they criticize his appearance, etc. So any exit to the street becomes an insurmountable problem.

Symptoms of social anxiety disorder are most often bodily. Common among them:

- redness

- nausea

- fear of vomiting, involuntary urination or defecation

All this manifests itself in trigger situations: at the time of being on the subway, during a job interview, or, for example, when entering the elevator. In this case, the patient usually admits that his fear is illogical and irrational. Having gone to a psychologist, he may even feel that he has worked through his fear, but as soon as there are a lot of people around again, there is no trace of a rational assessment.

In this case, the patient usually admits that his fear is illogical and irrational. Having gone to a psychologist, he may even feel that he has worked through his fear, but as soon as there are a lot of people around again, there is no trace of a rational assessment.

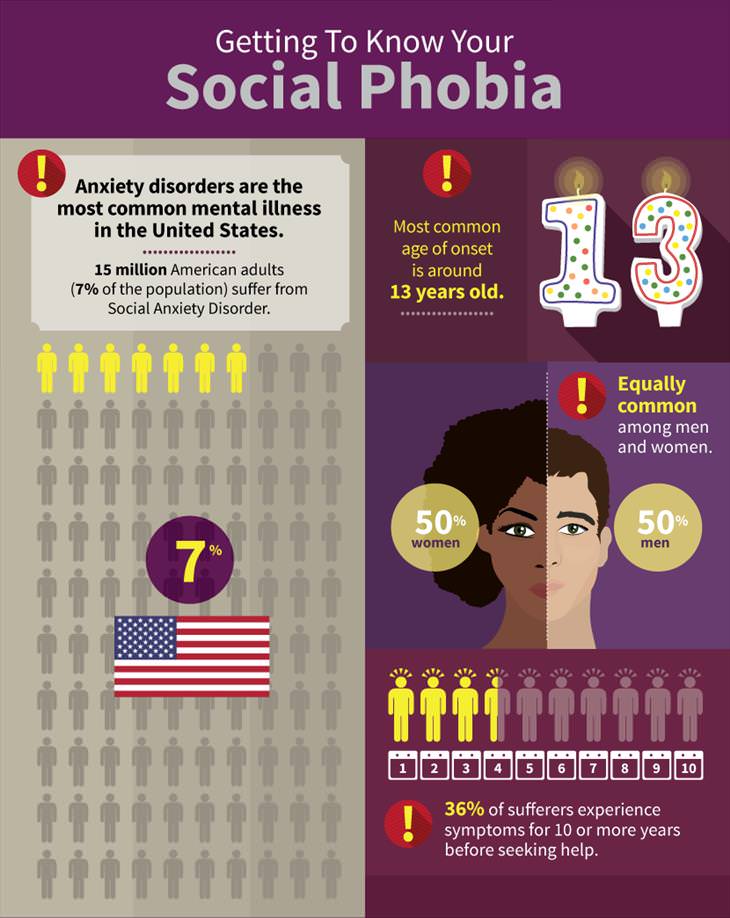

STR is a rather “young” pathology. The National Institute of Mental Health (USA) indicates 13 years as the average age of onset of the disease [3]. It can be assumed that in many cases it is rooted in traumatic experiences associated with adolescent insecurity and school bullying.

Panic disorder

Such a violation is characterized by suddenness. A panic attack develops rapidly, literally in a second, and lasts for several minutes. Sometimes a patient calls an ambulance because he thinks he has a heart attack or stroke.

Symptoms of panic disorder:

- heart palpitations

- sweating

- tremor

- dry mouth

- discomfort in the chest and abdomen

- fear of death

In diagnostics, repeatability over a certain period of time is considered an important feature. In other words, only one panic attack does not indicate a pathology. With such a disease, the patient is afraid of the next episode of panic, worries about its consequences and begins to avoid certain situations. So, if a panic attack overtook him on the bus, it is likely that the person will stop using public transport.

In other words, only one panic attack does not indicate a pathology. With such a disease, the patient is afraid of the next episode of panic, worries about its consequences and begins to avoid certain situations. So, if a panic attack overtook him on the bus, it is likely that the person will stop using public transport.

Panic disorder is more commonly diagnosed by the age of 30.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

PTSD occurs as a result of extreme events, during which the psyche was severely traumatized. It affects survivors of terrorist attacks, sexual violence, combatants and so on. Women are on average affected twice as often as men.

PTSD sufferers often have recurring dreams associated with the traumatic event. At the same time, avoiding behavior is formed in them as a defensive reaction to what happened. That is, a survivor of a terrorist attack in the subway will strive under no circumstances to get into the subway, and the survivor of a shipwreck will not go for a boat ride.

It is important that PTSD develops not only in victims, but also in witnesses of events, one way or another involved in them. Since the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center in New York, American scientists have done a lot of research on PTSD. It turned out, in particular, that after a few years, symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder were observed in 22% of firefighters who took part in the elimination of the consequences of a terrorist attack [4].

It is believed that the development of PTSD can be prevented. For this, survivors of an extreme event are advised to maintain contacts with loved ones, with those who can emotionally share what happened. Sometimes survivors or victims of violence develop a guilt complex. It is important that this does not happen. Therefore, work with a psychotherapist is also shown, the purpose of which is to teach a person to identify with survivors, and not with victims. Therefore, in the sense of prevention, volunteering is especially effective when a person helps those who, having gone through the same experience as himself, survived.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

OCD is characterized by intrusive thoughts (obsessions) and repetitive actions (compulsions). A classic example is the fear of germs and the overwhelming desire to wash your hands many times, sometimes even to chapped skin and burns.

It happens that obsessions and compulsions are observed separately. For example, a woman may develop an obsessive fear of killing her husband with a fork. Of course, she really loves her husband and, moreover, she herself is afraid of this thought. This is an obsession. If you add to this the idea that you can avoid killing if you go to the window, open and close it, then this is not only an obsession, but also a compulsion.

In OCD, intrusive thoughts, images, and impulses must be present for at least two weeks. It is characteristic that the performance of certain actions does not bring any satisfaction. Once again, washing his hands or checking the door lock, the patient will not smile or breathe a sigh of relief.

It is curious that OCD also includes disorders that differ in a set of very specific features. For example:

- pathological hoarding ("Plyushkin's syndrome"), when a person cannot explain why the rubbish growing around the mountain is so important to him

- dysmorphophobia - exaggerated dissatisfaction with one's body

- trichotillomania - pulling out one's own hair

- dermatotillomania - scratching one's own skin

This disease occurs in both adults and children. In young patients, symptoms of OCD may manifest with ideas such as "If I step on a crack in the pavement on my way to school, my mother will die." Such a child jumps over the cracks one after another, and this seems like a fun game, but in fact it is a compulsion associated with constant fear for the mother.

Compared to the diseases we have already discussed, OCD is perhaps the most amenable to psychotherapeutic treatment. Of course, drugs are also required, usually SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors), and at fairly high doses.

Of course, drugs are also required, usually SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors), and at fairly high doses.

Phobias

A phobia is an overwhelming fear of a specific object that causes a person to behave irrationally. Even thinking about this subject or situation can trigger a panic attack. The patient remains critical of the illogicality of his fear, but, faced with it, is unable to cope with his own horror or disgust.

Human phobias are very diverse: fear of certain animals, natural phenomena, such as thunderstorms, medical procedures, vehicles, and even fear of certain words and numbers. As with other disorders, an attack of a phobia is accompanied by bodily reactions such as those we mentioned for GAD and avoidance behavior. The quality of life also suffers.

Fortunately, all types of phobias lend themselves well to step-by-step psychotherapy (“step by step”). For example, if someone suffers from arachnophobia, he first learns not to be afraid of painted spiders, then spiders in the movies, then toy spiders, then a tarantula in a glass terrarium, and so on. Such therapy in tandem with SSRIs and tranquilizers gives a rapid improvement.

Such therapy in tandem with SSRIs and tranquilizers gives a rapid improvement.

Anxiety in mothers

In those who have just become a mother, increased anxiety is associated with hormonal changes, and some mood changes occur in approximately 85% of women in the postpartum period [5].

Let's talk first about the mechanisms of occurrence of anxiety-depressive syndromes after the birth of a child. The placenta is known to be the main source of estrogen during pregnancy. Approximately 7 days after giving birth, that is, when the placenta is no longer in the mother's body, estrogen levels reach a record low compared to previous months. Estrogen affects dopamine and serotonin: the higher its level, the more elated we experience, through an increase in serotonin levels. In addition, estrogen increases the residence time of serotonin in the synapse and slows down its breakdown. Therefore, during pregnancy, many women feel the comfort and security that leaves them after childbirth. The level of another hormone - progesterone - also becomes almost zero, and already on the third day after birth. Progesterone, like estrogen, enhances the action of serotonin and helps build emotional stability.

The level of another hormone - progesterone - also becomes almost zero, and already on the third day after birth. Progesterone, like estrogen, enhances the action of serotonin and helps build emotional stability.

The described hormonal and neurotransmitter changes underlie three conditions:

- baby blues, or postpartum blues

- postpartum depression

- postpartum psychosis

Baby Blues is a very common mood disorder: according to WHO estimates, it occurs in 80% of mothers. Many of its manifestations (tearfulness, apathy, etc.) are similar to postpartum depression. It is important, however, to understand the difference between them. The fact is that, being less pronounced, they do not prevent mothers from taking care of the newborn and themselves. In this case, the baby blues last up to two weeks and are intermittent.

In postpartum depression, on the contrary, the symptoms are more pronounced, they are accompanied by a change in appetite, sleep disturbance, decreased concentration, heart rhythm disturbance, and others. Patients with suspected such depression are shown a general and biochemical blood test to rule out anemia, vitamin deficiency, and thyroid dysfunction.

Patients with suspected such depression are shown a general and biochemical blood test to rule out anemia, vitamin deficiency, and thyroid dysfunction.

Now let's focus on postpartum psychosis. Fortunately, this is a fairly rare but very dangerous type of bipolar disorder. This condition develops in 1-2 women out of 1000 women in labor. Symptoms can appear as early as 48 to 72 hours after birth, which is when progesterone levels drop to a minimum. Women in this condition are erratic, agitated, may have hallucinations, and are often haunted by thoughts of harming themselves or their children. These patients require urgent medical attention.

In conclusion, let's talk about risk factors leading to various types of anxiety and depression in mothers. These include:

- a history of anxiety-depressive and other mental illness in a woman, as well as in other family members

- previous reproductive problems (infertility, stillbirth)

- adverse circumstances associated with the birth of a child (prematurity, birth trauma, lack of milk, etc.

)

) - sleep disorder in mother

- financial and other problems

Conclusions

- Not every anxiety indicates a pathology, but in some cases we can talk about a particular disease. Long-term anxiety is considered suspicious, which is not associated with a specific objectively existing threat and which significantly worsens the quality of a person's life, making it difficult for him to interact with other people.

- When making a diagnosis, accuracy is essential. Diagnoses like vegetative-vascular dystonia do not explain anything and are considered incorrect in modern psychiatry and neurology. Currently, the following anxiety disorders are distinguished: generalized, social, panic, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and phobias.

- These diseases have several dimensions: emotional (feelings of fear, shame, guilt and other negative emotions), cognitive (decreased concentration and shifting of attention, memory impairment, viscosity of thinking), bodily (feeling of a lump in the throat, sweating, tachycardia, nausea, tremor) and behavioral (irritability, tearfulness, avoidance behavior).

- A separate group of disorders is formed by conditions observed in women after the birth of a child. It is believed that they are associated with a sharp drop in the level of estrogen and progesterone, which, in turn, affect the content of serotonin. These include a fairly common mood change known as baby blues, as well as postpartum depression and emergency postpartum psychosis.

- Anxiety has a physiological basis: a decrease in the level of certain neurotransmitters and an increase in the activity of the amygdala, a kind of alarm button in the brain. Therefore, treatment with antidepressants, in particular SSRIs, and in certain cases with the use of tranquilizers is considered effective. In some diseases, psychotherapy, including for children, demonstrates high efficiency.

If unreasonable anxiety has become a constant companion of you or your child, contact Nashe Vremya clinic. We will select treatments that will help you get rid of anxiety and increase productivity at work and school performance.