Signs of pain in nonverbal patients

Recognize Non-Verbal Pain Cues - Parentis Health

Hospice care exists in order to improve a person’s quality of life. Key to this is managing pain. Pain affects more than physical comfort. It damages people emotionally and can even harm their relationship with their family as well. Therefore, it is important that caregivers and hospice workers respond to pain as quickly as possible. However, many end-of-life issues impair the ability to speak, which is why it is important caregivers be able to recognize non-verbal pain cues.

Acute pain vs. chronic pain

There are two types of pain: acute and chronic. Acute pain has a specific and obvious cause, such as stubbing your toe. It typically fades quickly once it has been treated, though sometimes it can linger.

Chronic pain, on the other hand, is constant, caused by an underlying condition that cannot be easily cured. It is so debilitating that, in most cases, it affects almost every aspect of a person’s life. Sometimes, patients struggle with the pain for so long, they cannot even properly register it anymore. It comes at them from everywhere, an irritating stimulus with no focal point.

How to recognize non-verbal pain cues

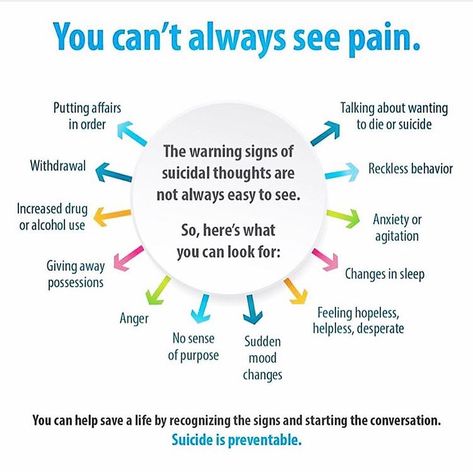

Most non-verbal pain cues are easy to identify. Look for:

- Grimacing, Pursed Lips, Furrowed Brow, Wrinkled Nose, Clasped Eyes

- Moaning, Yelling, or Crying

- Jaw Tightening

- Grinding Teeth

- Clenching Fists or Blankets

- Flinching

- Rapid or Unusual Breathing

- Limping

- Tense or Rigid Muscles

- Clutching or Guarding a Specific Part of the Body

One of the most serious symptoms is difficulty sleeping. If not caught it can create a vicious cycle. Poor sleep exacerbates chronic pain, which leads to less sleep and more pain.

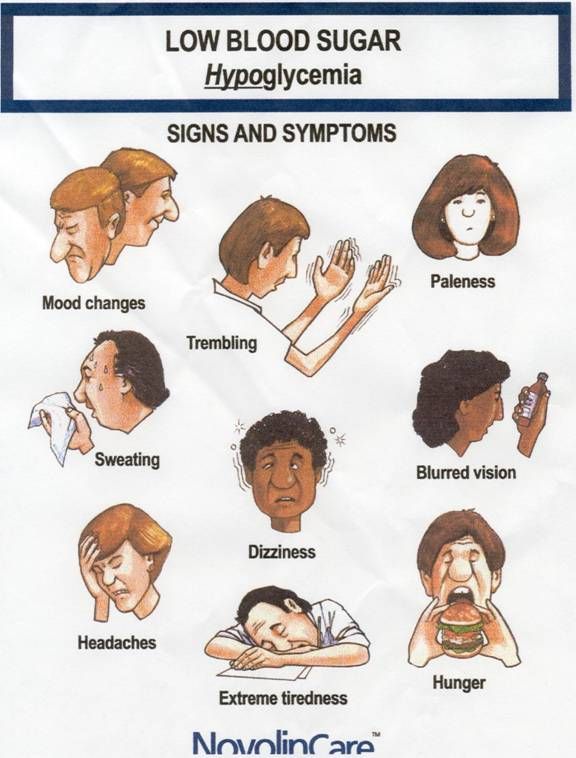

Monitoring appetite is another way to recognize non-verbal pain cues. As chronic pain grows worse, people become nauseated and stop eating. As a result, rapid weight loss may be an urgent sign a loved one is in distress.

As a result, rapid weight loss may be an urgent sign a loved one is in distress.

Behavior issues

Pain has a serious effect on people’s behavior as well. For example, in many cases, pain causes anxiety. Visible symptoms include restlessness, fidgeting, writhing, and panic attacks. Patients may also start pulling at their clothing, like they were trying to undress, or attempt to jump out of bed.

Pain also makes people withdrawn. Whereas before they may have been able to get up, shower, dress, or perhaps even go for a walk, now they only want to lay in bed.

Memory problems make behavior issues even worse. In these cases, the patient may lash out or become combative when their caregivers try to touch them or move them. This is purely reactive. Because they cannot state their feelings, lashing out might be the only way to communicate when something you do upsets them. They are distressed, but cannot identify the cause, so the pain will likely increase their confusion until it is treated.

Treating pain in non-verbal patients

For hospice patients, pain is normally treated with medication. There is a misunderstanding about the goal of medication in this situation. It is not given in order to put the patient to sleep, but to improve their quality of life and allow them to be happy in the time they have left.

For non-verbal patients, caregivers play an essential role in pain management. The closer they are to a patient, the easier it is for them to recognize non-verbal pain cues. For instance, if they notice a patient is more anxious and combative when they try to shower them, the caregiver can report the behavior to the doctor in order to begin a pain regimen.

Caregivers and hospice workers are also the only ones in a position to assess how well the medication is working. Is the patient functional again? Are they able to get out of bed? Are they eating? What is their mood? How long does it take for symptoms to re-emerge? This type of firsthand knowledge tells the doctor whether the patient should remain on the same medication, whether the patient needs a larger dose, or if they should be switched to a longer-lasting drug.

Under those circumstances, it is essential the caregiver be able to read the patient’s behavior. The closer their relationship, the more likely it is they will receive effective relief.

Why it is important to recognize non-verbal pain cues

Not every patient with a life-limiting illness experiences pain. Many remain verbal, awake, and alert. Unfortunately, however, when an illness impairs a patient’s ability to communicate, it is crucial that caregivers and hospice workers be able to recognize non-verbal pain cues. Their attention is essential to protecting the patient’s comfort and dignity.

Parentis Health is dedicated to providing its patients with the highest quality of life. Contact us to find out what we can do to make sure your loved one enjoys the peace and serenity they deserve.

Jose Escobar is the Hospice Executive for Parentis Health. He works with patients and families across Southern California, providing support and education, in order to alleviate the pain and suffering of chronic and terminal illness.

Controlling Pain and Discomfort, Part 2: Assessment in Non-verbal Older Adults

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

- PMC4991889

Nursing. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2017 May 1.

Published in final edited form as:

Nursing. 2016 May; 46(5): 66–69.

doi: 10.1097/01.NURSE.0000480619.08039.50

PMCID: PMC4991889

NIHMSID: NIHMS801778

PMID: 27096920

, MS, RN, PhD(c), PhD candidate and , MSN, RN, PhD(c), PCCN alumni, PhD candidate

Author information Copyright and License information Disclaimer

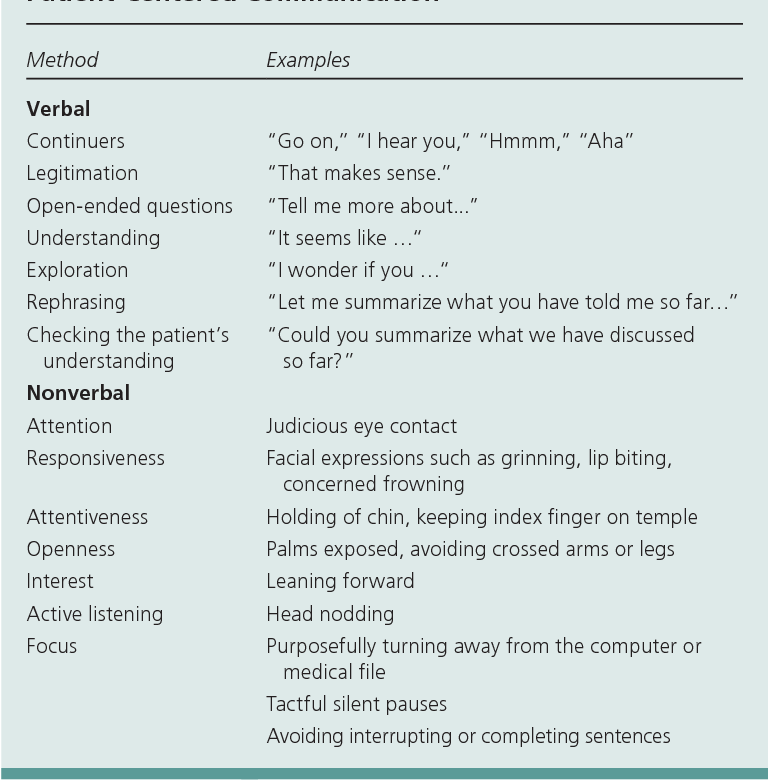

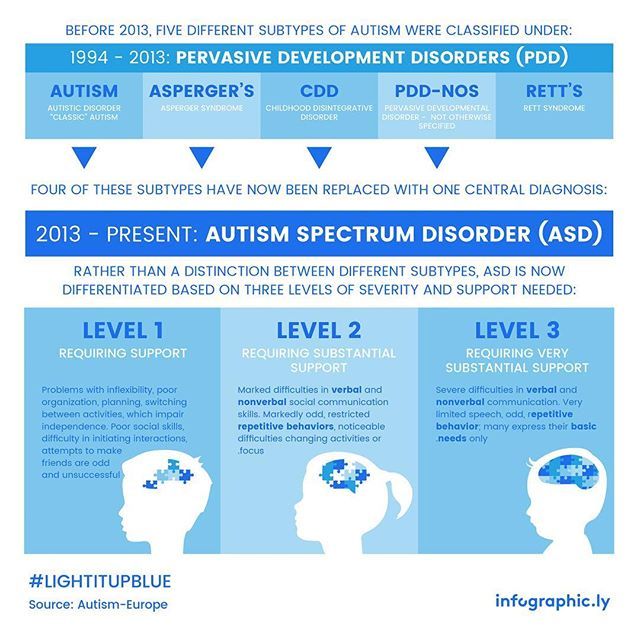

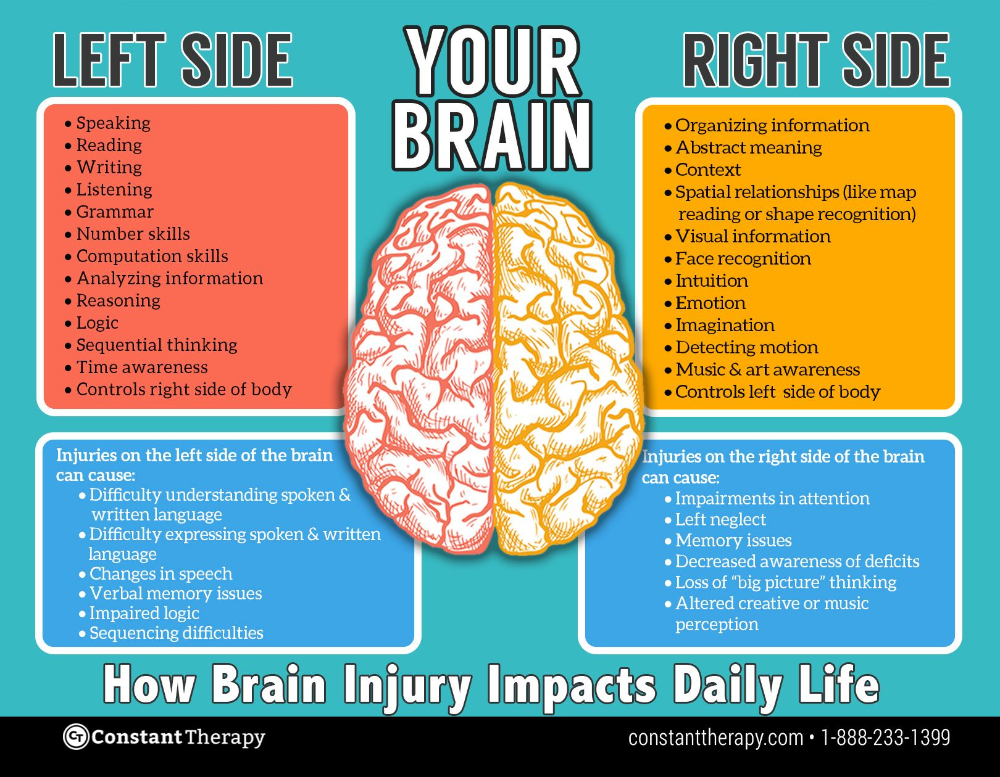

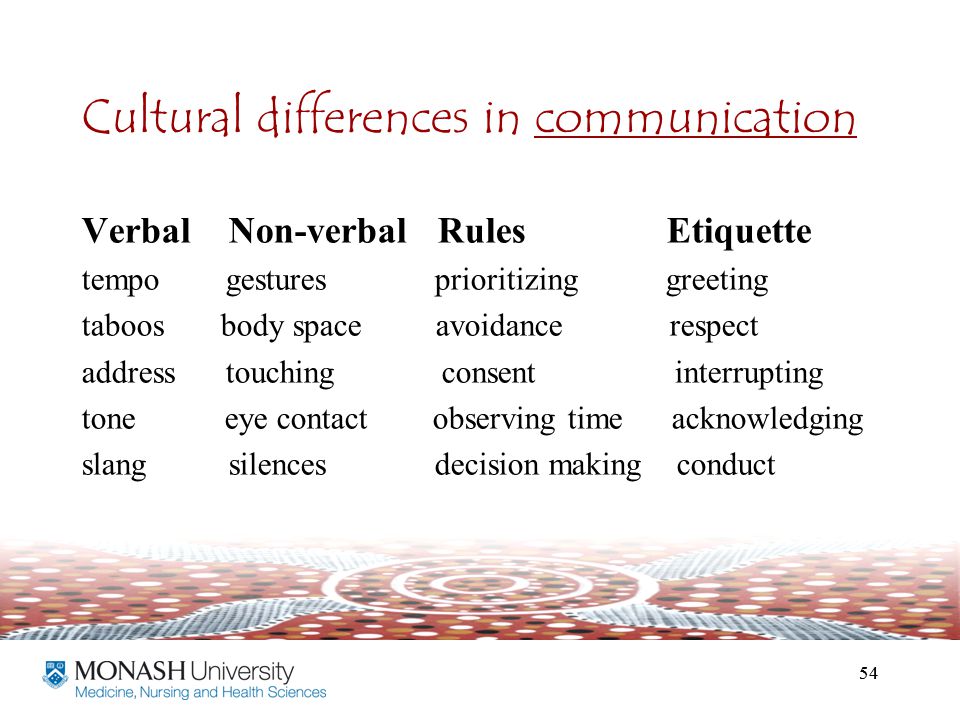

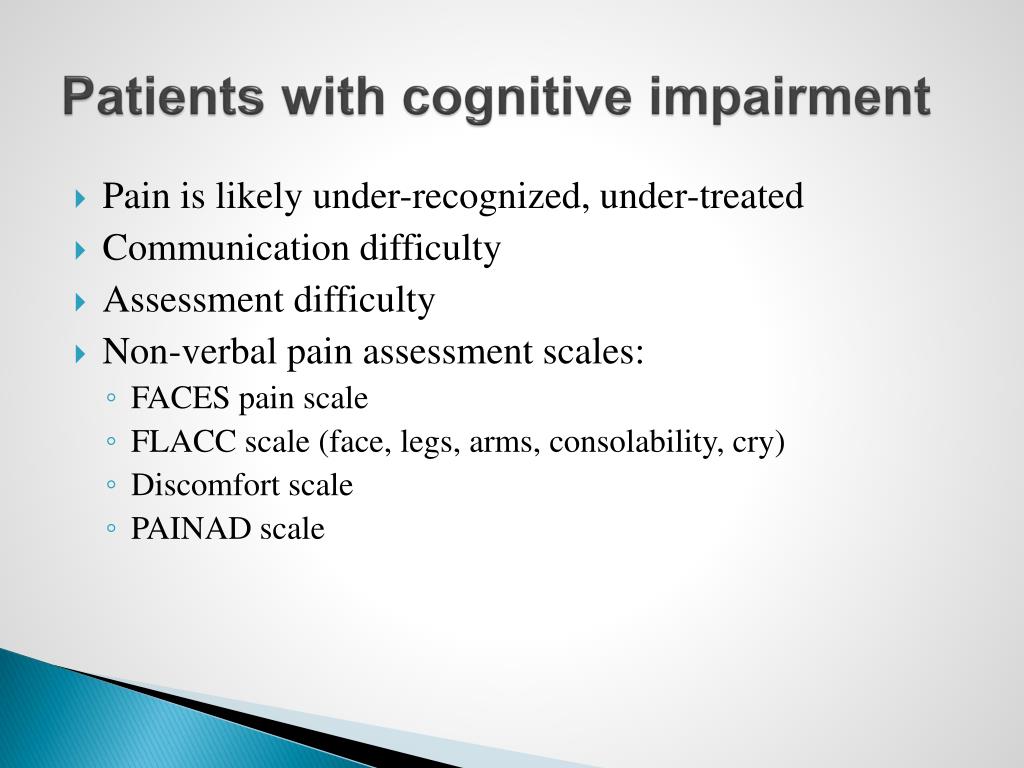

Because pain is a subjective experience, pain assessment relies heavily on verbal self-report. However, self-report may be difficult or impossible in nonverbal critically ill older adults who are intubated, sedated, or unconscious; or older adults with communication and cognitive impairments, such as aphasia/dysphasia, language barriers, dementia, delirium, intellectual disabilities, traumatic brain injury, and/or deaf or severe hearing impairment. As a result, they are unable to verbally convey and describe pain, placing them at greater risk for non- and under-assessment. To prevent under-assessment in this vulnerable population, a multi-component and interdisciplinary approach to determine pain is needed. It may be especially important to involve a palliative care nurse whose expertise in pain (symptom) management can facilitate effective assessment in older adults whose communication is more compromised due to advanced disease or impending death.

However, self-report may be difficult or impossible in nonverbal critically ill older adults who are intubated, sedated, or unconscious; or older adults with communication and cognitive impairments, such as aphasia/dysphasia, language barriers, dementia, delirium, intellectual disabilities, traumatic brain injury, and/or deaf or severe hearing impairment. As a result, they are unable to verbally convey and describe pain, placing them at greater risk for non- and under-assessment. To prevent under-assessment in this vulnerable population, a multi-component and interdisciplinary approach to determine pain is needed. It may be especially important to involve a palliative care nurse whose expertise in pain (symptom) management can facilitate effective assessment in older adults whose communication is more compromised due to advanced disease or impending death.

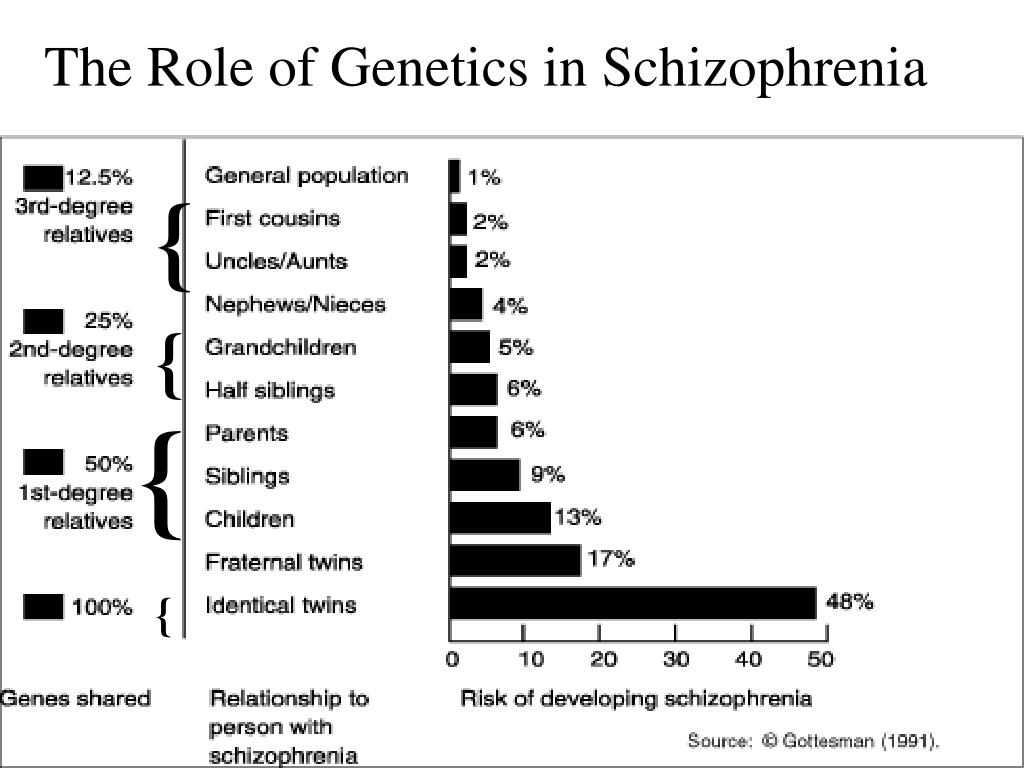

Dementia is one of the most common forms of cognitive impairment in older adults, and age is a major risk factor for both pain and dementia. Older adults have a lower pain threshold (i.e., minimum intensity of a stimulus that is perceived as painful) which may progressively decrease over time in older adults with dementia (Figure 1), while their pain tolerance (i.e., maximum intensity of a painful stimulus that a subject is willing/able to tolerate) increases because they are unable to cognitively recognize and quickly interpret pain, thus increasing vulnerability to consequences of pain. However, their pain often goes unrecognized because they may be unable to verbally communicate and self-report pain. Likewise, nurses and nursing assistants consistently report that cognitive impairment is a major barrier to pain assessment, and unrelieved pain exposes them to unnecessary suffering and exacerbation of cognitive impairment, as evidenced by decreasing memory and ability to communicate and process commands, decrease in scores on cognitive screening tezsts, and increased agitation.1–2 To help nurses more confidently identify pain in non-verbal adults, this second of a three-article series describes an evidence-based approach to pain assessment.

Older adults have a lower pain threshold (i.e., minimum intensity of a stimulus that is perceived as painful) which may progressively decrease over time in older adults with dementia (Figure 1), while their pain tolerance (i.e., maximum intensity of a painful stimulus that a subject is willing/able to tolerate) increases because they are unable to cognitively recognize and quickly interpret pain, thus increasing vulnerability to consequences of pain. However, their pain often goes unrecognized because they may be unable to verbally communicate and self-report pain. Likewise, nurses and nursing assistants consistently report that cognitive impairment is a major barrier to pain assessment, and unrelieved pain exposes them to unnecessary suffering and exacerbation of cognitive impairment, as evidenced by decreasing memory and ability to communicate and process commands, decrease in scores on cognitive screening tezsts, and increased agitation.1–2 To help nurses more confidently identify pain in non-verbal adults, this second of a three-article series describes an evidence-based approach to pain assessment.

The Hierarchy of Pain Assessment can be used to identify and assess pain in individuals unable to verbally communicate pain.3–6 This hierarchy can be implemented in acute care and long-term care and adapted for primary, ambulatory, and homecare where interaction with older adult may be limited by time.

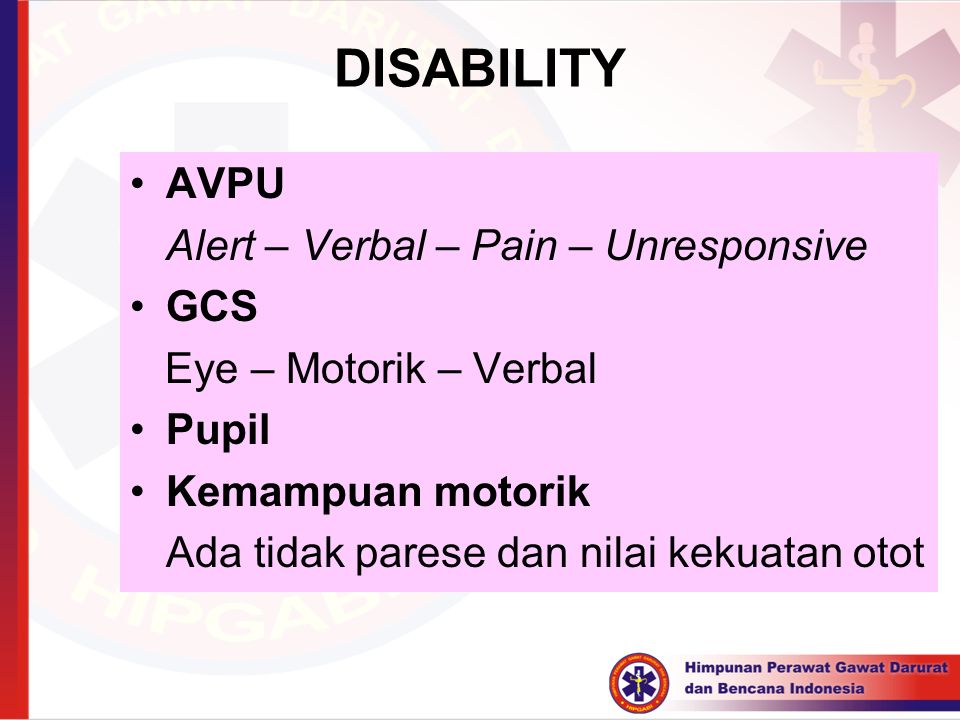

Step 1: Determine older adult’s reliability and verbal ability, and attempt self-report

Recommended

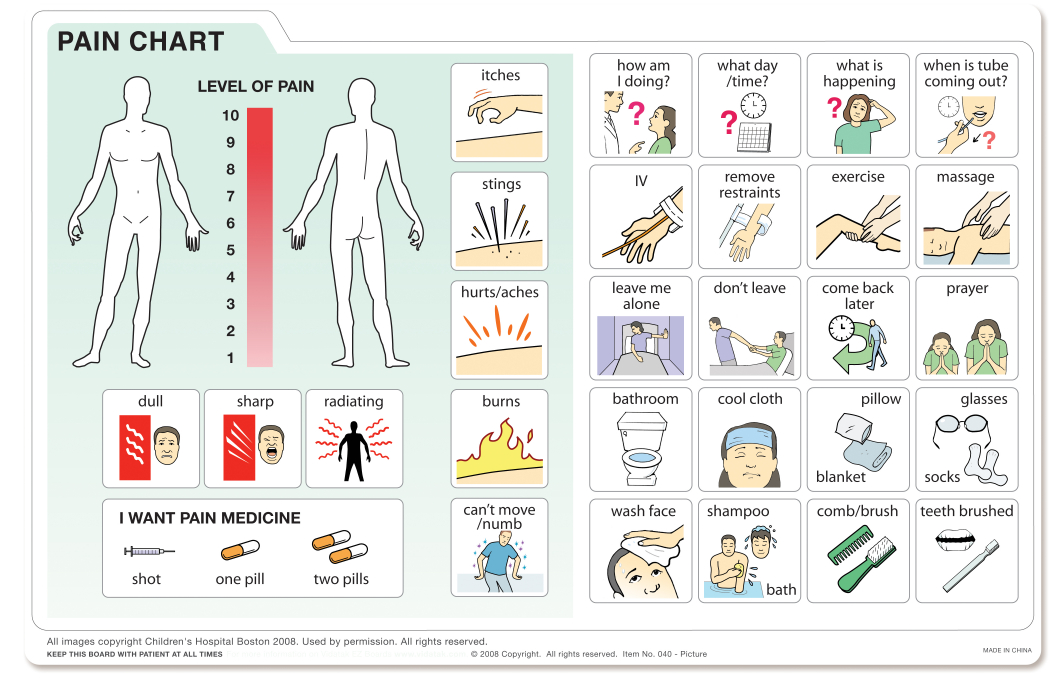

Communication and cognitive impairments may limit an older adult’s ability to reliably self-report, but not all persons with communication or cognitive impairment are unable to self-report, which is why self-report should be attempted. As noted in one study, older adults may not be able to articulate that they are in pain per sé or the location of pain, but may ask for “help”.2 In addition, older adults who are intubated but not heavily sedated may be able to squeeze hand, raise a finger, blink eyes, or nod head if they are having pain (or hurting) or discomfort. Older adults verbally limited by aphasia/dysphasia may be able to use a self-report pain scale by pointing to the intensity level and location(s). Also, older adults who may be deaf may require a sign-language interpreter.

Older adults verbally limited by aphasia/dysphasia may be able to use a self-report pain scale by pointing to the intensity level and location(s). Also, older adults who may be deaf may require a sign-language interpreter.

To determine if an older adult can reliably self-report, 1) observe coherency in communication and thought patterns, 2) assess mental status using a Mini-Cog or Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in acute care or Brief Interview for Mental Status (BIMS) for long-term care residents, 3) note if there is a diagnosis of cognitive impairment, and 4) assess understanding of pain scales by asking patients to show where no pain or severe pain is represented on a pain scale. These are cues that may indicate that the older adult’s report of pain may be unreliable. Accommodating sensory impairments is important as this could impact [reli]ability. Greater detail of this step is provided in Part 1 of this series. When older adult cannot report pain reliably, proceed with steps 2–6.

Not Recommended

Nurses should refrain from relying on a cognitive impairment diagnosis or communication impairments as reasons for an older adult’s inability or unwillingness to self-report. Even those with moderate dementia can sometimes report pain.3,7

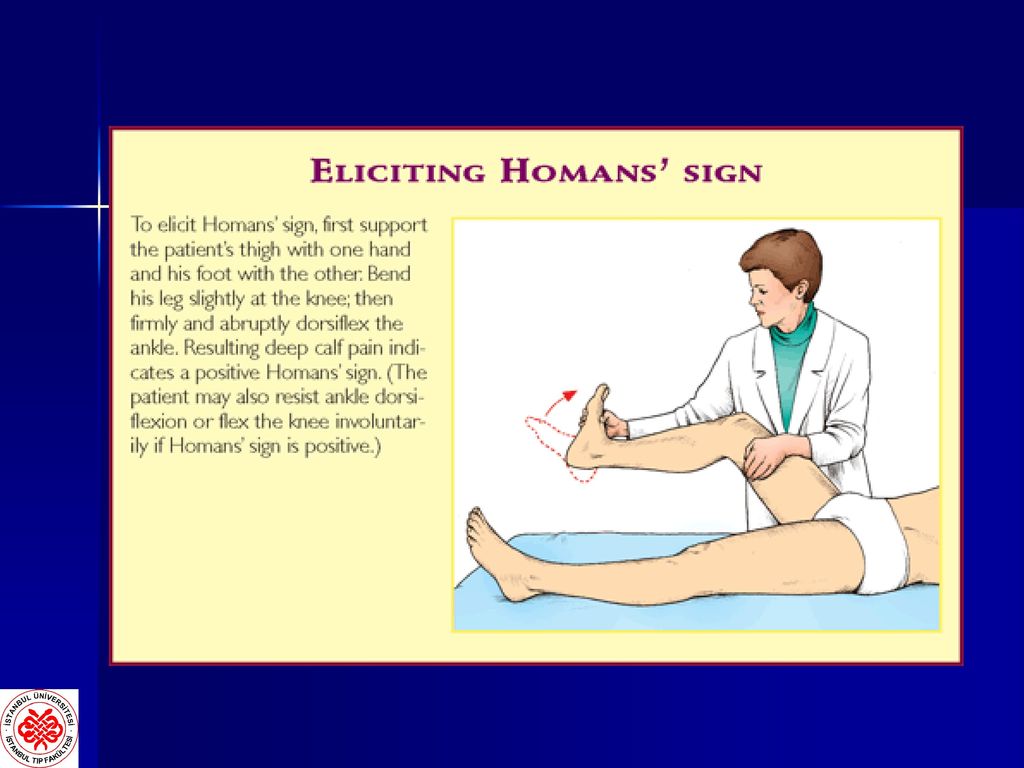

Step 2: Identify potential causes or sources of pain (i.e., pathologic, procedural, injury, pharmacological) common in older adults

Recommended

There are numerous causes of pain in older adults. Close observation during care activities often reveals subtle cues of pain. These cues should be followed by a focused nursing assessment and review of patient medical records to help determine cause of pain. Review patient’s medical diagnoses for chronic diseases associated with pain symptoms or history of chronic pain, acute conditions associated with pain, recent injury, newly added medical devices or taut restraints, and procedures such as catheter insertion.

6 Common causes of pain in older adults include osteoarthritis, pressure ulcers and wound care, infections, diabetic neuropathy, and irritation of previous injuries. For additional causes of pain see articles by Reid8 and Booker and colleagues.6

For additional causes of pain see articles by Reid8 and Booker and colleagues.6

Not Recommended

After determination of potential pain sources, interventions should not be withheld until behavioral indicators of pain manifest, nor should interventions be delayed until source of pain is diagnosed. Delayed intervention can result in additional complications.

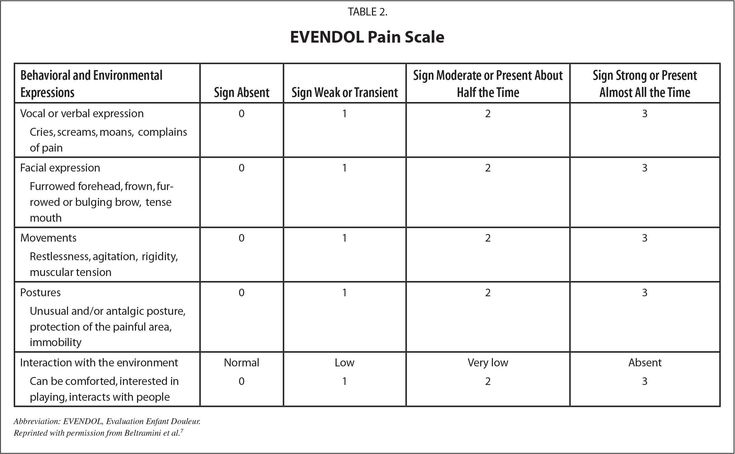

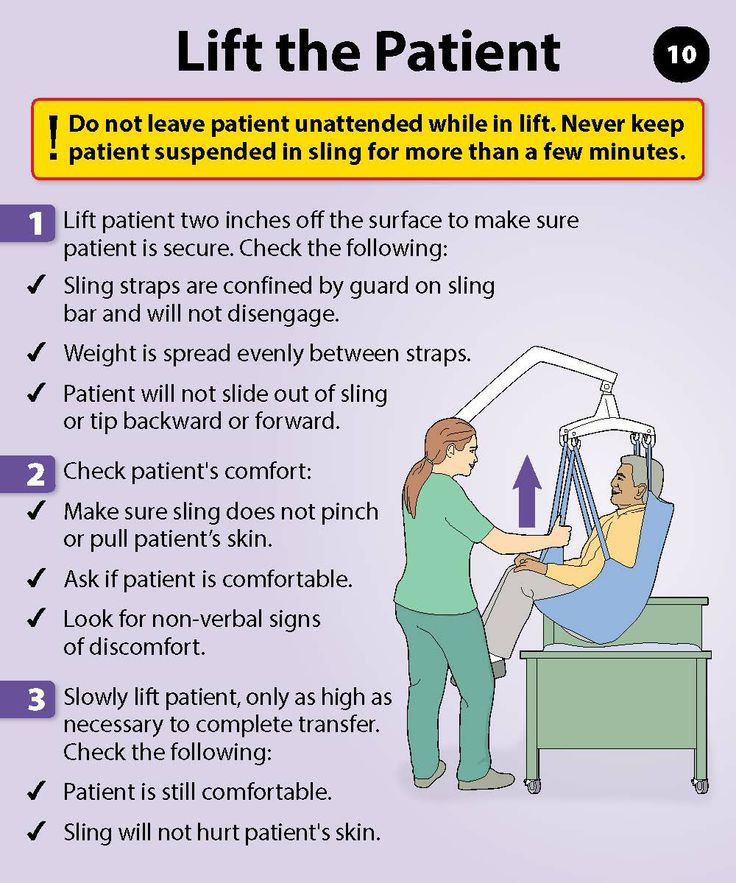

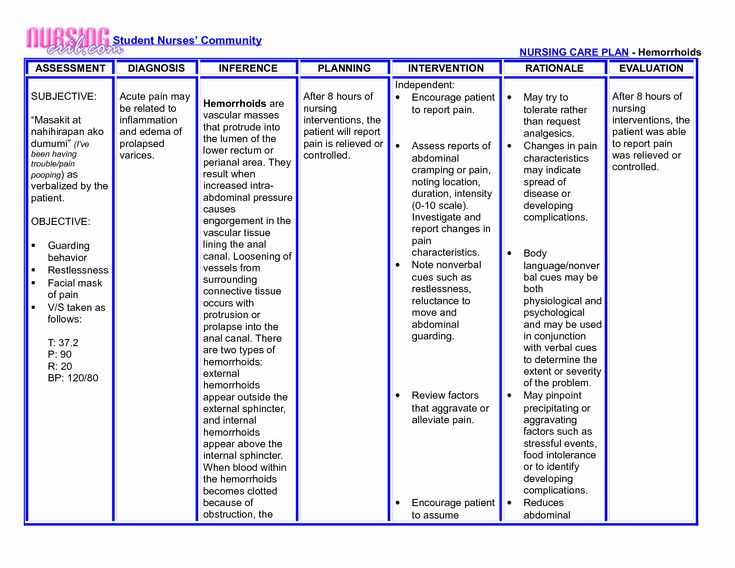

Step 3: Observe for indicators or behaviors suggestive of pain ()

Table 1

Behaviors Suggestive of Acute or Persistent Pain in Non-verbal Older Adults

| Category | Behavior* |

|---|---|

| Facial Expressions | Rapid blinking, frightened expression, distorted expressions, brow lowering, clenched teeth, orbit tightening, upper-lip raising, nose wrinkling, eye narrowing or closure |

| Verbalizations & Vocalization | Calling out for help, screaming, swearing, crying, moaning, sighing, praying, swearing |

| Body Movements | Altered gait/limping, rubbing a body area, tense tone/rigidity, decreased movement, guarding, pacing, rocking, fidgeting, repetitive movements, guarding |

| Interpersonal Interactions | Resisting personal care, aggression, withdrawal/isolation |

| Change in Mood and Mental State | Delirium, depressive symptoms, agitation, anxiety, irritability, crying, impaired executive function, declining cognition, exacerbation of cognition impairment |

| Change in Activity Patterns | Wandering, sleep disturbances, disengagement with social activities, wanting to stay in bed, change in normal routine |

| Change in Function | Decreased ability to engage in activities of daily living, rehabilitation, falls |

| Autonomic Signs | Pallor, altered breathing, change in VS |

Open in a separate window

*Intensity of behaviors or actions vary with intensity of pain.

Recommended

Consider pain if there is a subtle or significant change in the resident’s condition or behavior. Older adults with dementia experiencing pain may exhibit care-resistant behaviors; therefore, nurses should assess and treat pain before personal care is given. There can be an overlap in pain-suggestive behaviors and neurocognitive behaviors, making the distinction between pain and dementia or delirium symptoms more complicated. Therefore, nurses and providers must consistently use a valid, reliable, and practical pain behavior tool that is appropriate for the patient.3 There are over 15 pain behavior tools, but a thorough review of reliability, validity, and utility by an expert panel recommend the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia Scale (PAINAD) and Pain Assessment Checklist for Seniors with Limited Ability to Communicate (PACSLAC or PACSLAC-II) specifically for nursing home residents.9 In addition to reliability and validity, the choice of pain behavior instrument should consider patient race, culture, language, setting of care, and nurse’s knowledge of the tool. Observational discomfort-behavior tools, such as the, Discomfort in Dementia of the Alzheimer’s Type (DS-DAT), can be used with non-verbal patients who have dementia. Pain should be assessed at rest, during movement, and passive and active care activities. Use of pain observation tools improves recognition of pain and its intensity.10

Observational discomfort-behavior tools, such as the, Discomfort in Dementia of the Alzheimer’s Type (DS-DAT), can be used with non-verbal patients who have dementia. Pain should be assessed at rest, during movement, and passive and active care activities. Use of pain observation tools improves recognition of pain and its intensity.10

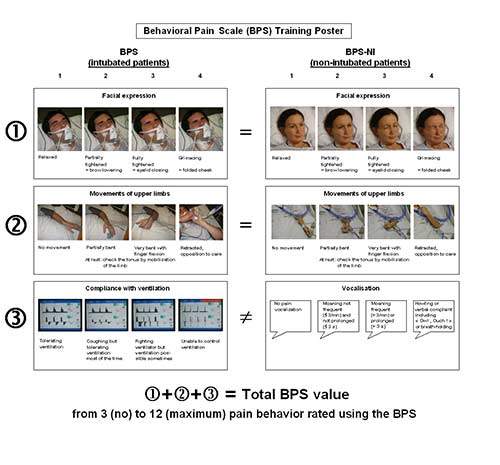

For critically-ill patients unable to self-report the Critical-care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT) and Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS) are recommended.11 Consulting with family and professional caregivers who know the person’s normative behavior can help determine if pain is triggering change in behaviors.

Not Recommended

Vital signs (VS) are often used to determine presence of pain, but, alone, these are not the best indicators considering that VS outside defined limits may be due to injury/disease process or medications. Elevated VS do not indicate presence of pain and non- elevated VS do not suggest absence of pain. However, changes in VS should alert the need for further medical attention and serve as cue for pain assessment.5 One study found no significant correlation between self-report of pain intensity and heart rate and blood pressure.12 Also, sedation does not eliminate pain, and snoring neither indicates absence of pain or that the patient is sleeping well with or without pain.

However, changes in VS should alert the need for further medical attention and serve as cue for pain assessment.5 One study found no significant correlation between self-report of pain intensity and heart rate and blood pressure.12 Also, sedation does not eliminate pain, and snoring neither indicates absence of pain or that the patient is sleeping well with or without pain.

Step 4: Discuss with all relevant informants changes in the patient’s behavior, mood, and daily functional patterns that may indicate pain

Recommended

Family and professional caregivers, and even housekeepers, who have had a long-term relationship with the older adult, can share information about the patient’s communication patterns and behaviors that indicate pain and discomfort. For example, during, clinic visits with primary care provider or homecare visits with the nurse, the family is especially valuable in providing additional details and corroboration of pain. These individuals can also share information about past behaviors and disposition when the older adult was in pain. 5 If depression is suspected, the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD) or Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 or PHQ-2) can be administered.

5 If depression is suspected, the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD) or Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 or PHQ-2) can be administered.

Not Recommended

Using family or caregivers perceptions of pain in older patients should not be used as sole evidence, as research shows that family members/caregivers can underestimate or overestimate pain.13 Proxy report from family and caregivers should be used along with nursing judgment and other evidence identified in any of the steps 1–5.

Step 5: If pain is suspected, initiate an analgesic trial after comfort and non-pharmacological measures have been tried

Recommended

While pain-related behaviors trigger nurses to intervene in different ways, interventions rarely included an analgesic trial,14 despite recommendations and evidence demonstrating that analgesic trials are effective in reducing pain behaviors.15,16 Initiate a stepwise analgesic trial paying close attention to patient response and proceeding with each subsequent step if behaviors do not improve. 4,16 The duration of the trial depends upon individual patient characteristics, times of suspected pain, and type of medication trialed; thus, the trial can range from one hour to one week. Example empiric analgesic trials are as follow:

4,16 The duration of the trial depends upon individual patient characteristics, times of suspected pain, and type of medication trialed; thus, the trial can range from one hour to one week. Example empiric analgesic trials are as follow:

For suspected nociceptive pain,

Step 5a: Start with a non-opioid, such as oral acetaminophen 650–1000 g every 8 hours with a maximum daily dose of 3,000 g. When oral acetaminophen cannot be given, consider intravenous acetaminophen (Ofirmev®). Older adults with severe liver impairment should not be given acetaminophen. A topical analgesic can be used with acetaminophen.

Step 5b: If acetaminophen proves ineffective alone, add a short acting, low dose opioid such as oral morphine sulfate 5 mg every 12 hours to a maximum dose of 10 mg every 12 hours. Again, a topical analgesic can be used.

Step 5c: If the short-acting opioid is not adequate, try adding a longer-acting opioid, such as Buprenorphine transdermal patch 5 mcg/hour to a maximum 10 mcg/hour for a seven-day period.

The acetaminophen and/or short-acting opioid can be used routinely or for breakthrough pain.

The acetaminophen and/or short-acting opioid can be used routinely or for breakthrough pain.

For suspected neuropathic or mixed pain,

Step 5a: Give acetaminophen (as dosed above) with pregabalin 25 mg, maximum of 300 mg/day for seven days.

Step 5b: If acetaminophen is not effective with the pregabalin, a short- or long-acting opioid can be added.

Behaviors and function often improve with acetaminophen, but if behaviors do not improve after completing all steps, a pain specialist consultation may be needed and other reasons for behaviors should be explored.4 If behaviors decrease and function improve during the trial (i.e., frequency, duration, intensity), assume pain present (APP), document in care plan, and develop a multi-modal plan of care (i.e., Step 6).

Not Recommended

Analgesic placebo trials to elicit a therapeutic effect should not be implemented.17 Analgesic placebos are sham or “fake” medications in the form of sugar pills, normal saline injections, or minute doses of drugs. 17 Older adults deserve real treatment for real pain.

17 Older adults deserve real treatment for real pain.

Dilution of opioid medications is also discouraged unless there is a physician’s order or clear instructions from the pharmaceutical manufacturer or pharmacy. A 2014 survey by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices found that nurses unnecessarily dilute many medications, including those used for pain management.18

Step 6: Develop a multi-modal pain treatment plan with measurable comfort-function-mood-behavior goals

Recommended

If analgesic trial confirms pain, providers and family/caregivers should collaboratively construct a multi-modal pain treatment plan guided by measurable goals for sustained or improved comfort, function, mood, and behavior. Continue to assess and document pain using same pain-behavior observation tool. Multi-modal treatment should (1) include an appropriate analgesic plan of care (APOC) based on benefits/risks and pain type and severity, and (2) incorporate complementary, alternative, and integrative interventions to maximize analgesic effect. More on multi-modal treatment can be read in Part 3 of this series.

More on multi-modal treatment can be read in Part 3 of this series.

Not Recommended

The analgesic found to be effective in improving behaviors in the Step 5, may not be most appropriate to continue on a routine basis. The purpose of the analgesic trial is to help identify the presence of pain.

When pain is not detected and treated adequately, executive function decreases. This further limits older adults’ with cognitive and communication impairments ability to report pain. Nurses are encouraged to use multiple methods to determine and treat pain in older adults who are unable to verbally communicate or articulate their pain.

Staja Booker, MS, RN, PhD(c) is a National Hartford Center for Gerontological Nursing Excellence Patricia G. Archbold and MayDay Fund Scholar whose research and clinical focus is pain management in ethnically diverse older adults.

Staja Q. Booker, Word Address: The University of Iowa, College of Nursing, 50 Newton Road Iowa City, IA 52242, Home address: 2675 Heinz Road, Apt 1 Iowa City, IA 52240, ude. awoiu@rekoob-ajats, 318-533-9076 (home), 319-353-5535 (fax)

awoiu@rekoob-ajats, 318-533-9076 (home), 319-353-5535 (fax)

Christine Haedtke, Work address: The University of Iowa, College of Nursing, 50 Newton Road, Iowa City, IA 52242, Home address: 2910 B Ave Deep River, IA 52222, ude.awoiu@ektdeah-enitsirhc, 608-799-3758 (Cell)

1. Coker E, Papaioannou A, Kaasalainen S, et al. Nurses’ perceived barriers to optimal pain management in older adults on acute medical units. Appl Nurs Res. 2010;23:139–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Dobbs D, Baker T, Carrion IV, et al. Certified nursing assistants’ perspectives of nursing home residents’ pain experience: Communication patterns, cultural context, and the role of empathy. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014;14(1):87–96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2012.06.008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Hadjistavropoulos T, Herr K, Prkachin KM, et al. Pain assessment in elderly adults with dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:1216–1227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Reuben DB, Herr KA, Pacala JT, et al. Pain. In: Reuben DB, Herr KA, Pacala JT, et al., editors. Geriatrics at your fingertips. 16th. New York: American Geriatrics Society; 2014. pp. 227–240. [Google Scholar]

Pain. In: Reuben DB, Herr KA, Pacala JT, et al., editors. Geriatrics at your fingertips. 16th. New York: American Geriatrics Society; 2014. pp. 227–240. [Google Scholar]

5. Herr KA, Coyne PJ, McCaffery M, et al. Pain assessment in the patient unable to self-report: Position statement with clinical practice recommendations. Pain Manag Nurs. 2011;12(4):230–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Booker SQ, Bartoszczyk DA, Herr KA. Pain management in frail elders. Am Nurs Today. In press. [Google Scholar]

7. Chen YH, Lin LC. The credibility of self-reported pain among institutional older people with different degrees of cognitive function in taiwan. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015;16(3):163–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Reid MC, Eccleston C, Pillemer K. Management of chronic pain in older adults. BMJ. 2015;350:h532. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Herr KA, Bursch H, Ersek M, et al. Use of pain-behavioral assessment tools in the nursing home: Expert consensus recommendations for practice. J Gerontol Nurs. 2010;36(3):18–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Gerontol Nurs. 2010;36(3):18–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Lukas A, Barber JB, Johnson P, et al. Observer-rated pain assessment instruments improve both the detection of pain and the evaluation of pain intensity in people with dementia. Eur J Pain. 2013;17(10):1558–1568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Gélinas C, Puntillo KA, Joffe AM, Barr J. A validated approach to evaluating psychometric properties of pain assessment tools for use in non-verbal critically ill adults. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34(2):153–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Chen HJ, Chen YM. Pain assessment: Validation of the physiologic indicators in the ventilated adult patient. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014 Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Santos S, Castanho M. The use of visual analog scales to compare pain between patients with alzheimer's disease and patients without any known neurodegenerative disease and their caregivers. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;29(4):320–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Gilmore-Bykovskyi AL, Bowers BJ. Understanding nurses' decisions to treat pain in nursing home residents with dementia. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2013;6(2):127–138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Elliot AF, Horgas AL. Effects of an analgesic trial in reducing pain behaviors in community-dwelling older adults with dementia. Nurs Res. 2009;58(2):140–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Sandvik RK, Selbaek G, Seifert R, et al. Impact of a stepwise protocol for treating pain on pain intensity in nursing home patients with dementia: a cluster randomized trial. Eur J Pain. 2014;18(10):1490–1500. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Arnstein P, Broglio K, Wubrman E, et al. Use of placebos in pain management. Position statement. Pain Manag Nurs. 2011;12(4):225–229. Retrieve March 7, 2015 from http://www.aspmn.org/documents/UseofPlacebosinPainManagement.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) Some IV Medications Are Diluted Unnecessarily In Patient Care Areas, Creating Undue Risk. 2014 Jun; Retrieved March 7, 2105 from http://www.ismp.org/newsletters/acutecare/showarticle.aspx?id=82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2014 Jun; Retrieved March 7, 2105 from http://www.ismp.org/newsletters/acutecare/showarticle.aspx?id=82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Signs of pain in non-verbal children

Hunfeld J.A.M., Passchier J.

In the last 10 years, attention to the problem of pain in children has increased. This is due to medical and technological advances, such as the latest surgical interventions and treatments, as well as the emergence of new views on pain in children. In this regard, in 1993, at the request of the then State Secretary of the Ministry of Welfare, Health and Culture, the Pain Research Program Committee of the Dutch Research Organization, which is a division of the Central Program Committee for Chronic Diseases, compiled a note on pain and assessment degree pain in children. These materials form the basis of this article, which provides a brief overview of the current knowledge on pain and pain assessment in children, and reflects the gaps reported by Dutch experts in the scientific literature

To map international experience in measuring pain a literature study was conducted using the Medline and Psychlit databases. We restrict ourselves to the review articles cited in Current contens and textbooks on pain in children published since 1986 to 1994. Publications in Dutch scientific journals on pain and its measurement in children were also examined

We restrict ourselves to the review articles cited in Current contens and textbooks on pain in children published since 1986 to 1994. Publications in Dutch scientific journals on pain and its measurement in children were also examined

Pain and pain assessment in children

Definition of pain, types of pain and perception of pain. The most commonly used is the definition of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IAIB): "Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience accompanied by actual or potential tissue damage, or a condition whose verbal description corresponds to such damage"

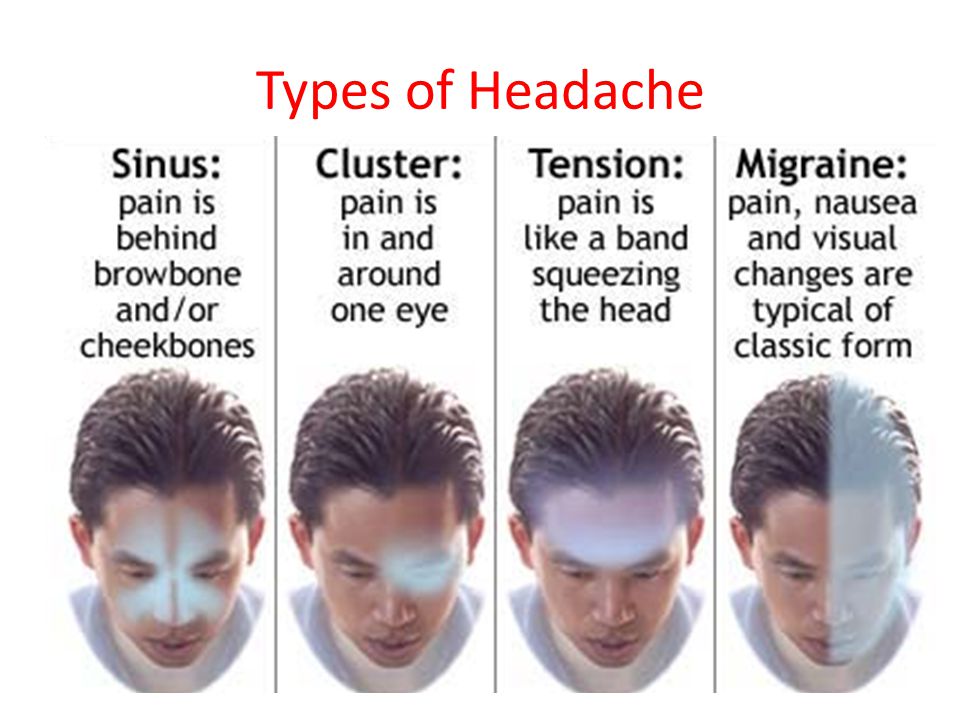

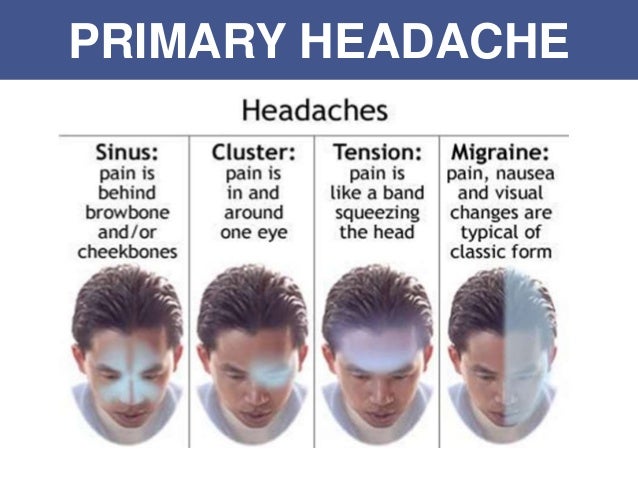

Distinguish between acute, chronic and recurrent pain. Acute pain is caused by tissue damage, such as injury, illness, or invasive medical intervention. This pain is most common in children. Pain is termed chronic if it lasts longer than would be expected based on normal healing time. The scientific literature indicates periods from 3 to 6 months. In children, chronic pain is most often of an organic nature, such as pain due to cancer or arthritis. Recurrent pain is referred to as 3 or more episodes of acute pain within 3 months. These episodes may be due to diseases such as arthritis, but they may also be headache or abdominal pain without a detectable nociceptive (pain receptor) substrate. In this case, pain is associated with a stressful situation and is often observed in children whose parents have a history of such pain in their anamnesis

Recurrent pain is referred to as 3 or more episodes of acute pain within 3 months. These episodes may be due to diseases such as arthritis, but they may also be headache or abdominal pain without a detectable nociceptive (pain receptor) substrate. In this case, pain is associated with a stressful situation and is often observed in children whose parents have a history of such pain in their anamnesis

Melzack and Wall introduced "gate control theory", expanding the concept of pain from a purely sensory to a multidimensional phenomenon. At the physiological level, this theory shows, in particular, how emotions can influence the experience of pain. According to this theory, nociceptive information can be inhibited during transmission from peripheral nerve fibers to nerve fibers in the spinal cord. The authors describe this mechanism as a gate. When the gate is open, nociceptive information reaches the brain. When the gate is partially or completely closed, less information comes to the brain or it does not come at all. Peripheral processes (for example, when rubbing an injured part of the body) and central processes (for example, with an increased level of fear) can affect the transmission of pain information and cause a decrease or increase in pain

Peripheral processes (for example, when rubbing an injured part of the body) and central processes (for example, with an increased level of fear) can affect the transmission of pain information and cause a decrease or increase in pain

Rice 1. Egg Loesor;

The 4 circles represent a variable effect on the experience of pain. (Published with permission.)

Based on this theory, Melzack developed the first multidimensional pain assessment system, the McGill Pain Questionnaire. The multidimensional nature of pain can also be found in the oft-cited Loeser model. The "Egg of Loeser" consists of 4 circles that reflect the exchange interactions between nociception (an organic component of pain), sensation (registration by the central nervous system), experience (suffering from pain) and pain behavior. As the duration of pain increases, the components of experience and behavior increasingly influence how a person feels pain (Fig. 1)

Cognitive development and choosing the right way to assess the degree of pain

The choice of how to assess the degree of pain in addition to the type of pain is determined by the age and development of the child, clinical circumstances and cultural background. The subjective nature of pain makes it difficult to measure. This is especially true for those who find it difficult to put their pain into words. As a result, the treatment of pain in newborns until the early 1980s was rarely adequately performed, since it was assumed that due to the immature nervous system, they practically did not feel pain. The experiments of Anand et al., as well as Anand and Hickey, have changed these ideas. They showed that preterm infants after surgery with conventional minimal anesthesia developed significantly greater stress responses (defined as an increase in the concentration of catecholamines, growth hormone, glucagon, corticosteroids), had more postoperative complications, and had higher mortality than in the neonatal group. who received full anesthesia (fentanyl)

The subjective nature of pain makes it difficult to measure. This is especially true for those who find it difficult to put their pain into words. As a result, the treatment of pain in newborns until the early 1980s was rarely adequately performed, since it was assumed that due to the immature nervous system, they practically did not feel pain. The experiments of Anand et al., as well as Anand and Hickey, have changed these ideas. They showed that preterm infants after surgery with conventional minimal anesthesia developed significantly greater stress responses (defined as an increase in the concentration of catecholamines, growth hormone, glucagon, corticosteroids), had more postoperative complications, and had higher mortality than in the neonatal group. who received full anesthesia (fentanyl)

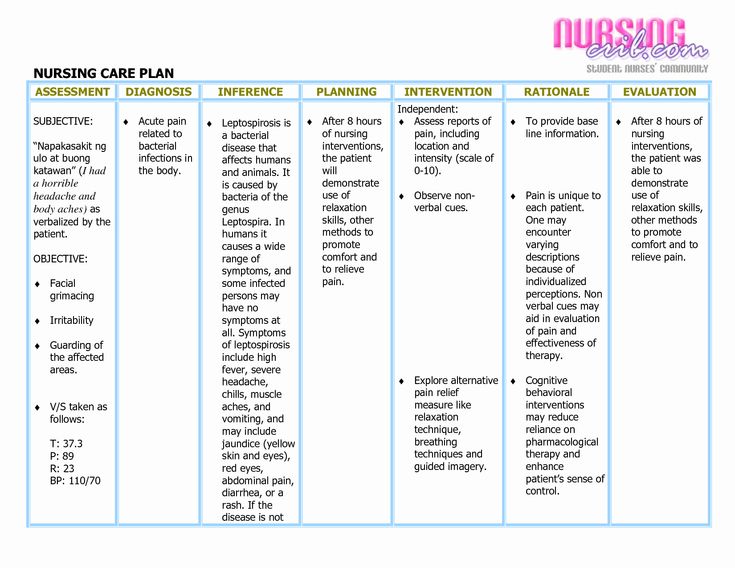

Table 1. adapted for Holland

"Scale Comfort", with the help of which the intensity of some reactions of the body

Clead state

Deep sleep

Light sleep

Clead and defeat

Status of increased readiness

Calm/excited

Calm

Slightly scared

Scared

Very scared

Panic

Blood pressure

Below baseline

All the time at baseline

Infrequent (1 to 3 times) increases of 15% or more over baseline

Frequent (more than 3 times) increases of 15% or more over baseline

Constantly increased by 15% or more from baseline

Better observational techniques have shown that newborns are sensitive to pain on a behavioral and emotional level and that their responses to noxious stimuli are influenced by biological and environmental factors. Preterm infants appear to be even more sensitive to pain stimuli than term infants. Based on these findings, McGrath and Unruh conclude that neonatal immaturity is not about the inability to experience pain, but the inability to communicate it. Under these conditions, cognitive (mental) development probably plays the most important role. Therefore, in young children, methods based on non-verbal behavioral research, in particular on the study of emotions, are often used. The facial expression study conducted by Ekman and Friesen was decisive.

Preterm infants appear to be even more sensitive to pain stimuli than term infants. Based on these findings, McGrath and Unruh conclude that neonatal immaturity is not about the inability to experience pain, but the inability to communicate it. Under these conditions, cognitive (mental) development probably plays the most important role. Therefore, in young children, methods based on non-verbal behavioral research, in particular on the study of emotions, are often used. The facial expression study conducted by Ekman and Friesen was decisive.

Figure 2. Newborn facial expression: reaction to a heel prick.

Available non-verbal measures of pain in the absence of a "gold standard" are being explored by comparing results with other measures (eg physiological) and with expected changes in pain experience under anesthesia and over time after the intervention. In this way, their "constructive consistency" can be established, in other words, whether they measure what they are supposed to measure

A child in the period from birth to 3 years is in the phase of sensory-motor development; he thinks, so to speak, with his body. Therefore, behavioral observation is recommended as a method for assessing the degree of pain. The movement, position of the body, facial expression and the nature of the crying of the child are recorded (Fig. 2). Observation of behavior can be done directly or later using videotape. In the first case, this is usually done by specially trained nursing staff. At the same time, they check in advance whether their consistency in the estimates is acceptable (for example, weighted k _ 70; kappa is a statistical variable for measuring consistency between observers, taking into account the measure of random consistency)

Therefore, behavioral observation is recommended as a method for assessing the degree of pain. The movement, position of the body, facial expression and the nature of the crying of the child are recorded (Fig. 2). Observation of behavior can be done directly or later using videotape. In the first case, this is usually done by specially trained nursing staff. At the same time, they check in advance whether their consistency in the estimates is acceptable (for example, weighted k _ 70; kappa is a statistical variable for measuring consistency between observers, taking into account the measure of random consistency)

Figure 3. Oucher scale. To assess the degree of pain, the child can choose one of the photographs of children's faces with and without increasing expression of pain.

(Copyright owned by Judith E. Beyer, R.N.,

Ph.D., University of Colorado Health Sciences Center School of Nursing, Denver, Colo, USA.)

Based on the Eastern Ontario Children's Hospital Pain Scale (OECH) for preterm (less than 37 weeks) and term newborns (from 37 weeks to 6 weeks after birth), the Neonatal Pediatric Pain Scale (NIPS) has been developed to record acute pain (from a needle) and pain-induced distress. To assess postoperative pain in Dutch children, Boelen van der Loo modified the FWDBVO. Facial observation forms the basis of the "Neonatal Facial Coding System" (NFCS) developed by Grunau and Craig to measure acute pain in newborns

To assess postoperative pain in Dutch children, Boelen van der Loo modified the FWDBVO. Facial observation forms the basis of the "Neonatal Facial Coding System" (NFCS) developed by Grunau and Craig to measure acute pain in newborns

In addition, in this age group, the degree of pain is judged on the basis of physiological changes, such as accelerated heart rate and high blood pressure, slow breathing, sweating of the palms and increased levels of catecholamines. Physiological measurements, however, require complex equipment, so they are used only when the child is already connected to this equipment, perhaps when used in an intensive care unit, for example. Optimal measurement of pain in this age group is possible using a combination of behavioral and physiological measurements. An example of such a combined method is the "Comfort Scale", which records the intensity of 8 reactions, such as alertness, calmness/arousal, body movements, muscle (face) tension, blood pressure, respiration and heartbeat. This scale has been developed for Holland and, together with other different methods of assessing the degree of pain, is currently being investigated in the intensive care unit of the Department of Pediatric Surgery of the Academic Hospital Rotterdam - Children's Hospital Sofia in cooperation with the Department of Pediatric Surgery of the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam (Table 1; H. Koot message 1994 g.)

This scale has been developed for Holland and, together with other different methods of assessing the degree of pain, is currently being investigated in the intensive care unit of the Department of Pediatric Surgery of the Academic Hospital Rotterdam - Children's Hospital Sofia in cooperation with the Department of Pediatric Surgery of the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam (Table 1; H. Koot message 1994 g.)

The cognitive level of children aged 3-7 years is such that they themselves can indicate pain. Their increased focus on the sensory leads to the fact that various sensory stimuli, for example, during a puncture of a vein, they experience more than older children. These irritants can be, for example, the smell of a disinfectant, a bright white coat and the intonation of the voice of a doctor giving an injection, the feel of a rubber glove on his hand, etc. Children of this age are often asked to express pain intensity in terms of color or drawing (projective methods) using, for example, the "Eland color tool" or the "Poker chip scale"

In this age group, the Oucher scale is also often used to measure pain intensity, and the child can choose from various photographs of baby faces (Fig. 3)

3)

If the child is about 7 years old, more abstract intensity scales can be used to record pain

Pain intensity can , for example, expressed through words (verbal rating scale - VVO) or by crossing out numbers from 0 (no pain) to 10 (terrible pain; numerical rating scale - NVR). The downside of the SVO is that the interpretation of words can be different. The problems with the use of the SNR are that some people have a strong preference for one or another number. In addition, students tend to rate high numbers as "good" and low numbers as "bad". Another disadvantage is the low sensitivity. Therefore, the child is also sometimes asked to self-rate the pain from 0 (no pain) to, for example, 100 (unbearable pain; 101-item NNR). More sensitive than most verbal and numerical scales is the visual analog scale (VAS). It is a horizontal line 10 cm long, on which the child himself can indicate the intensity of pain with a dash, the assessment varies from "no pain" to "the worst pain imaginable. " VAS-type scales allow very accurate and reliable registration of both acute and chronic and recurrent pain. Additional advantages are that the scale is a sliding continuity and the sums constitute a scale of proportions so that they can be tested by parametric statistical methods

" VAS-type scales allow very accurate and reliable registration of both acute and chronic and recurrent pain. Additional advantages are that the scale is a sliding continuity and the sums constitute a scale of proportions so that they can be tested by parametric statistical methods

Subjective assessment of pain in this age group is often combined with standardized behavioral assessment methods; an example is the Behavioral Distress Observation Scale (BEDS), which monitors socially desirable responses. SNPD allows accurate and reliable recording of both pain and fear during bone marrow puncture

Children 7-12 years old have concrete-operational thinking. The ability to think abstractly in this age category increases, but, mainly in younger children, is still strongly associated with concrete ideas. In older children, the experience of pain, in addition to sensual ones, is often also associated with mental associations. Pain, for example, is not only "stabbing", but also something that "loses the good mood". Older children are also more likely to associate pain with loss of control over their own actions (eg, inability to participate in sports and school activities). In this age group, methods are used that, in addition to sensory, allow for an affective and evaluative assessment of pain, such as the McGill Pain Questionnaire adapted by Huijer Abu-Saad for Dutch children. The Varni/Thompson Pediatric Pain Inventory (VAP) is used to assess chronic and recurrent pain in children with rheumatoid arthritis. In addition to the quality and intensity of pain, PHB also registers the pain history of parents and the child and environmental factors

Older children are also more likely to associate pain with loss of control over their own actions (eg, inability to participate in sports and school activities). In this age group, methods are used that, in addition to sensory, allow for an affective and evaluative assessment of pain, such as the McGill Pain Questionnaire adapted by Huijer Abu-Saad for Dutch children. The Varni/Thompson Pediatric Pain Inventory (VAP) is used to assess chronic and recurrent pain in children with rheumatoid arthritis. In addition to the quality and intensity of pain, PHB also registers the pain history of parents and the child and environmental factors

And in this age group, behavior is an important additional measure of pain assessment, as in the Procedural Behavioral Rating Scale-r (PPS-r) used for bone marrow and spinal canal punctures. abstract thinking. He is able to think about such negative consequences of pain in the near and distant future as disability. In this age group, self-report methods are mainly used. For chronic or recurrent pain, VAS is an important part of the questionnaires. In addition, a child suffering from such pain can use a pain diary, in which, in addition to the intensity of pain, he can also record other, probably important information, such as the use of medications, the time of the onset of pain and his activities before it began, indicate what interference this causes him pain. Diaries are currently mainly used in the Netherlands and abroad in the study of pain in young patients with migraine

For chronic or recurrent pain, VAS is an important part of the questionnaires. In addition, a child suffering from such pain can use a pain diary, in which, in addition to the intensity of pain, he can also record other, probably important information, such as the use of medications, the time of the onset of pain and his activities before it began, indicate what interference this causes him pain. Diaries are currently mainly used in the Netherlands and abroad in the study of pain in young patients with migraine

In this age group, it is also possible to use self-report methods that aim to assess such aspects of quality of life as functioning at school, activity at home, hobbies and social life. The scale for assessing the quality of life for patients with headache aged 12 to 17 years was developed by Langeveld et al. Table 2 provides an overview of methods for assessing the degree of pain

Lack of methods for assessing pain in children

Due to the large number of available methods, it may seem that further development of methods for assessing pain is futile. It is not right. For many patients, the available pain assessment methods are not suitable because they cannot adequately express the pain. This applies primarily to pain in newborns (especially premature ones) with congenital abnormalities, in which the degree of pain cannot yet be correctly assessed. In addition, their movements are often constrained by the abundance of modern life-sustaining medical equipment. It remains to be seen whether existing behavioral pain assessment methods are suitable for them or whether new tools need to be developed. This is also true for pain in a mentally or physically disabled child and for children from different ethnic groups

It is not right. For many patients, the available pain assessment methods are not suitable because they cannot adequately express the pain. This applies primarily to pain in newborns (especially premature ones) with congenital abnormalities, in which the degree of pain cannot yet be correctly assessed. In addition, their movements are often constrained by the abundance of modern life-sustaining medical equipment. It remains to be seen whether existing behavioral pain assessment methods are suitable for them or whether new tools need to be developed. This is also true for pain in a mentally or physically disabled child and for children from different ethnic groups

Most methods have been developed to assess acute pain. The question is whether they are also valid for recording long-term or chronic pain when some signs, in particular movement, are less pronounced

A large number of methods have been developed to assess the quality of life in adults, while there are still few available methods for recording the quality of life in children. There is a great need for methods to record the impact of recurrent and chronic pain, for example, on social functioning, school achievement, and the overall well-being of a child in pain

There is a great need for methods to record the impact of recurrent and chronic pain, for example, on social functioning, school achievement, and the overall well-being of a child in pain

Conclusion

Over the past 10 years, there has been increasing attention in the Netherlands both to assessing the degree of pain in children and to managing it. Pain assessment methods developed in the US and UK are usually adapted for the Dutch population. Currently, integrated projects are being carried out in various institutions in the Netherlands, the aim of which is to develop methods for measuring the degree of pain in children from 0 to 3 years. The development of methods for recording the quality of life of a child with chronic pain has also begun. When applying existing methods and developing new ones, it is necessary to remember all the time that many methods can be implemented within the framework of research, but they often require too much time and labor, and this makes their routine use in clinical practice impossible. When developing new methods, it is necessary to take into account the fact that pain assessment takes place in everyday life: at home, at school and in the hospital

When developing new methods, it is necessary to take into account the fact that pain assessment takes place in everyday life: at home, at school and in the hospital

Literature:

1. Ministerie van Welzijn. Volksgezondheid en Cultuur (WVC). Pijn en pijnmeting bij kinderen. Notitie van de Programmacommissie Pijnonderzoek. Rijswijk: Ministerie van WVC, 1993

2. IASP Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain terms: a list with definitions and notes on usage. Pain 1979;6:249-52.

3. McGrath PA, Pain in children. Nature assessment and treatment. New York: Guilford Press, 1990.

4. Dingemans WA, Groenman NH, Kleef M van, Krijgsman MJ. Pijn en pijnbehandeling. Een basaal onderwijscurriculum, Nederlandse Vereniging ler Bestudering van Pijn. Maastricht: Universitaire Pers, 1993

5. Melzack R. The McGill pain questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain 1975;277-99

6. Anand KJS, Sippell WG, Aynsley-Green A. Randomised trial of fentanyl anaesthesia in preterm babies undergoing surgery: effects on the stress response. Lancet 1987;i:243-8.

Lancet 1987;i:243-8.

7. Anand KJS, Hickey PR. Pain and its effects in the human neonate and fetus. N Engl J Med 1987;317:1321-9.

8. Campos JJ, Barrett KC, Lamb ME, Goldsmith HH, Stenberg C. Socioemotional development. In: Hait MM, Campos JJ, editors. Infancy and developmental psychobiology. New York: Wiley Press, 1983:783-915.

9. Franck LS. A new method tj quantitatively describe pain behavior in infants. Nurs Res 1986;35:28-31.

10. Huijer Abu-Saad H. Beoordeling van pijn bij kinderen. Pijninformatorium 1987;13:1-17.

11. Anand KJS, McGrath PJ. Pain in neonates. Pain research and clinical management. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers, 1993

12. Fitzgerald M, Millard C, McIntosh N. Cutaneous hypersensitivity following peripheral tissue damage in newborn and its reversal with topical anaesthesia. Pain 1989;39:31-6.

13. McGrath PJ, Unruh A. Pain in children and adolescents. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1987.

14. Ekman P, Friesen P. The repertoire of nonverbal behavior: categories, origins, usage and coding. Semiotica 1969;49-98.

Semiotica 1969;49-98.

15. Nunnally JC. psychometric theory. New York: McCraw-Hill, 1978.

16. McGrath PJ, Johnson G, Goodman JT, Schilinger J, Dunn J, Chapman J. The CHEOPS: a behavioral scale to measure postoperative pain in children. In: Fields HL, Dubner R, Cervero F, editors. Advances in pain research and therapy. New York: Raven Press, 1985:395-402.

17. Lawrence J, Alcock D, McGrath P, Kay J, McMurray S, Dulberg C. The development of a tool to assess neonatal pain. Neonatal Network 1993;12:59-66.

18. Centraal Begeleidingsorgaan voor de Intercollegiale Toetsing (CBO). Acute pijn bij kinderen. Preventie en behandeling. Utrecht: CBO, 1993:II

19. Grunau RVE, Craig KD. Facial activity as a measure of neonatal pain expression. In: Tyler DC, Krane EJ, editors. Advances in pain research and therapy. New York: Raven Press, 1990:147-56

20. Ambuel B, Hamlett KW, Marx CM, Blumer JL. Assessing distress in pediatric intensive care environments: the COMFORT scale. J Pediatr Psychol 1992;17:95-109.

J Pediatr Psychol 1992;17:95-109.

21. Linden van Heuvell GFEC van. Voorbereiding op medische ingrepen. Ontwikkeling en evaluatic van een stress management training voor kinderen in het ziekenhuis die vaak geprikt worden [proefschrift]. Groningen: Rijksuniversiteit, 1994.

22. Eland JM. Minimizing pain associated with prekindergarten intramuscular injections. Issues Compr Pediatric Nurs 1982;5:361-72

23. Hester NK. The preoperational child's reaction to immunization. Nurs Res 1979;28:250-5.

24. Beyer JE. The Oucher: a user's manual and technical report. Evanston, III.: Judson, 1984

25. Linssen ACG, Spinhoven Ph. Pijnmeting in de klinische praktijk. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1991;135:557-60

26. McGrath PA, Brigham MC. The assessment of pain in children and adolescents. In: Turk DC, Melzack R, editors. Handbook of pain assessment. London: Guilford, 1992;295-314.

27. Jay SM, Ozolins M, Elliott C, Caldwell S. Assessment of children's distress during painful medical procedures. J Health Psychol 1983;2:133-47.

J Health Psychol 1983;2:133-47.

28. Schultz NV. How do children perceive pain. Nurs Outlook 1971;19:670-3.

29. Huijer Abu-Saad H. On the development of a multidimensional Dutch Pain Assessment Tool for children. Pain 1990;43:249-56.

30. Varni JW, Thompson KL, Hanson V. The Varni/Thompson Pediatric Pain Questionnaire. I. Chronic musculoskeletal pain in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pain 1987;28:27-38

31. Katz ER, Kellerman J, Siegel SE. Behavioral distress in children with cancer undergoing medical procedures: developmental considerations. J Consult Clin Psychol 1980;48:356-65

32. Katz ER, Sharp B, Kellerman J, Siegel SE. Anxiety as an affective focus in the study of acute behavioral distress: a reply to Schacham and Daut. J Consult Clin Psychol 1981;49:470-1.

33. Larsson B, Melin L. The psychological treatment of recurrent headache in adolescents. Headache 1988;187-95

34. Osterhaus SOL, Passchier J. The optimal length of headache recording in juvenile migraine patients. Cephalalgia 1992;12:297-9

Cephalalgia 1992;12:297-9

35. Langeveld J. Passchier J, Koot HM. Development of a quality of life instrument for young patients with migraine. In: BPs A, Bousser MG. Ferrari MD, Lace JW, Olesen J, Sicuteri F, editors. Proceedings of the 6th International Headache Congress. Cephalalgia 1993;13 Suppl 13;220.

36. Boelenvan der Loo WJC. De Oucher: een pijnbeoordelingsinstrument voor 4 tot en met 8-jarigen. Pijnbulletin 1990;10:13-6.

37. Szyfelbein SK, Osgood PF, Carr DB, The assessment of pain and plasma beta-endorphin immunoactivity in burned children. Pain 1985;22:173-28.

Table 2. Different ways of assessing the degree of pain in children (according to McGrath et al.)

| Behavior observation; use in newborns and as an additional method in children under 12 years of age | Physiological reactions use in neonates | Self-report methods for children over 3 years old | Self-report methods for children over 12 years old | |||

| Pose | Reflexes | Level : | Intensity scales |

| ||

| Specific distress | Heartbeat | catecholamines | (VASH, painful | Interview | ||

| facial expression | Blood pressure | growth hormones | thermometer, scale | Questionnaires | ||

| Vocalization/character of crying | Breathing | glucagon | Outcher, verbal categories | Diaries | ||

|

| pO indicator 2 | insulin | Projective tests (color, shape, pattern) | Scale quality of life | ||

|

| (transdermal measurement) | b-endorphins |

|

| ||

http://www. rmj.ru/articles_2596.htm

rmj.ru/articles_2596.htm

How to measure your own and others' pain. Scales and methods of pain relief

Pain is the most common symptom that occurs in any pathology: infections, coronary heart disease, rheumatoid arthritis and other diseases. The issue of anesthesia is especially acute in metastatic cancer. We tell you how to measure pain and learn how to manage it.

Illustration: Katya October

Types of pain

Pain evolutionarily helps us survive, respond in time to a cut, sprain, burn or injury. Pain can also be a sign of illness. If something hurts for a long time, we don’t know the cause of the pain and we can’t focus on daily activities - we understand that we need to go to a therapist or a neurologist.

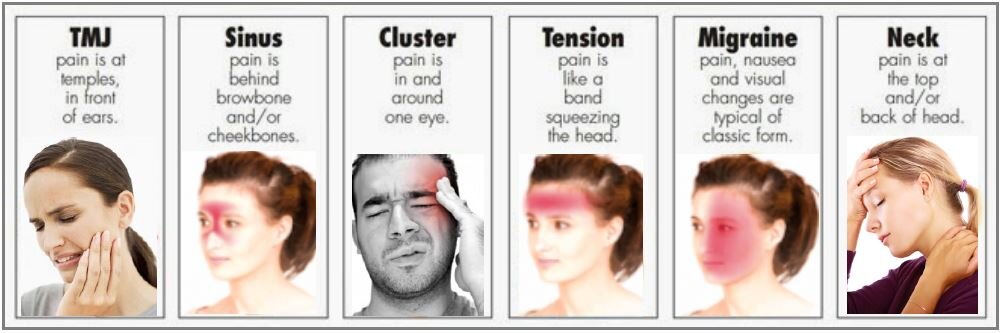

At the appointment, the doctor usually asks to describe the pain and its nature, to tell in what situations and for how long it has been manifested, to show the location of the pain. Interestingly, the description of pain often depends on the field of activity of a person and his communication skills. The neurosurgeon of the Three Sisters clinic Mikhail Zonov says: “If there is a teacher, writer, artist or philosopher at the reception, then the pain in the description acquires a bright emotional coloring: “it looks like an iron burn”, “tingles”, “shoots”, “whines”, "It's like goosebumps." It is more difficult to understand what a person means when he says: “It hurts, that’s all.”

The neurosurgeon of the Three Sisters clinic Mikhail Zonov says: “If there is a teacher, writer, artist or philosopher at the reception, then the pain in the description acquires a bright emotional coloring: “it looks like an iron burn”, “tingles”, “shoots”, “whines”, "It's like goosebumps." It is more difficult to understand what a person means when he says: “It hurts, that’s all.”

Pain can be neuropathic (caused by disturbances in the structure and function of nerves), nociceptive (occurs when peripheral pain receptors located in organs are irritated) and psychogenic (provoked by emotional factors). If the pain occurs suddenly and unexpectedly, it is called acute. If it bothers you for several weeks or months - chronic. A patient may have several types of pain at the same time.

People with chronic pain may be encouraged to keep a diary. In it, the patient records the time of occurrence of pain, his feelings, as well as the intake of painkillers. Some experts believe that the diary helps to reduce psycho-emotional perception, to understand the duration of the prescribed drug, others believe that this fixes the patient on his own world of pain.

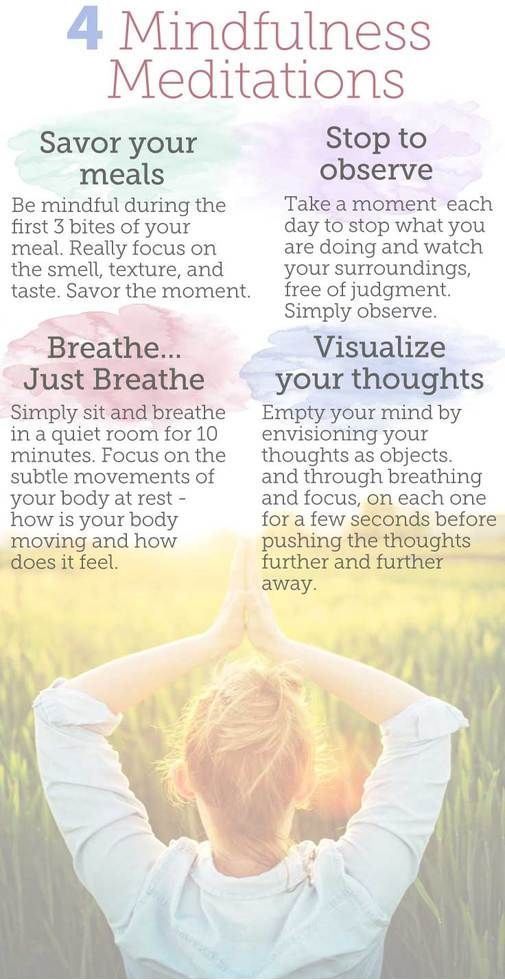

In the treatment of pain, doctors use different methods: drug therapy (painkillers, antidepressants, muscle relaxants), targeted therapy (blockades), neuromodulation (using electrical or chemical effects on the nerve), surgery. In addition, to relieve pain, the doctor may recommend sports, massage, meditation.

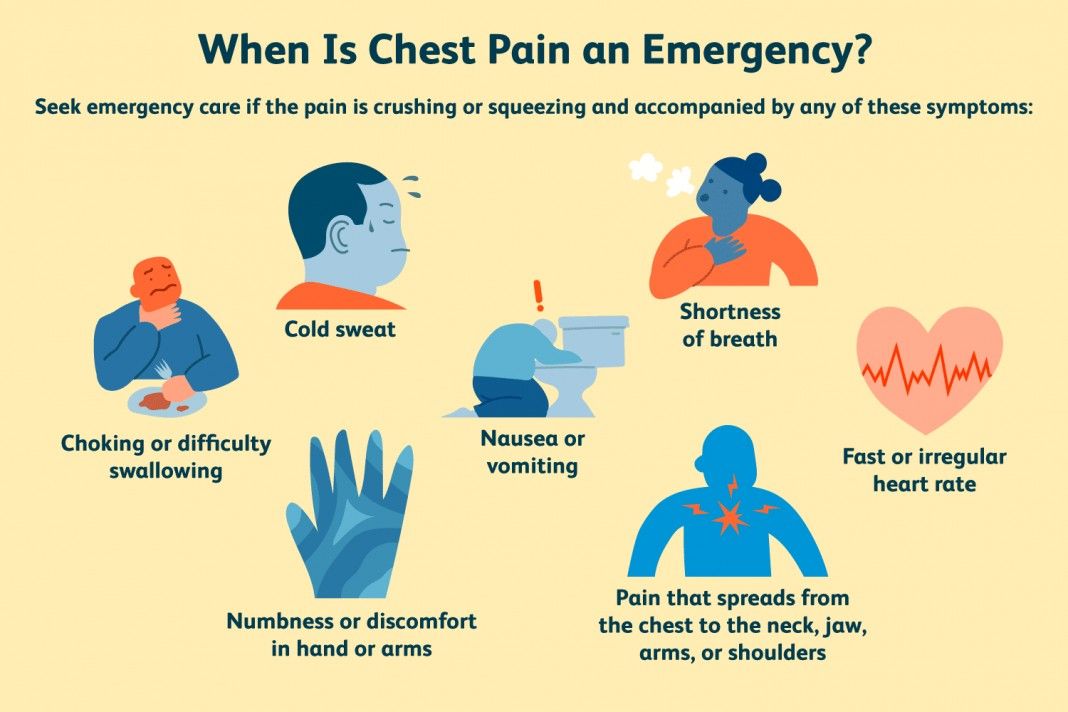

Neurosurgeon Mikhail Zonov says that psychogenic pain is often found in patients: “In addition to pain, people usually experience difficulty in breathing, spasms, discomfort in the chest, a sensation of a lump in the throat. One of the indicators of psychogenic pain is if the patient says that pain from the neck radiates to the arms, legs and lower back at the same time. Patients with psychogenic pain syndrome need the help of a psychologist or psychotherapist. But often because people have preconceptions about psychotherapy, they end up on the operating table or receive months of treatment that doesn't work for them."

Not all people can report their pain, and this does not mean that they do not experience it. Perhaps an older person is embarrassed to talk about pain, because he is used to the fact that pain "must be endured." A person with progressive dementia who has lost the ability to communicate with others cannot communicate his feelings. The child may not talk about the pain, because he is afraid of the consequences (go to the hospital, doctors, injections).

Perhaps an older person is embarrassed to talk about pain, because he is used to the fact that pain "must be endured." A person with progressive dementia who has lost the ability to communicate with others cannot communicate his feelings. The child may not talk about the pain, because he is afraid of the consequences (go to the hospital, doctors, injections).

It is important that loved ones pay attention to the well-being of their relatives and be able to recognize pain. The longer a person suffers pain, the more difficult it is to treat.

Illustration: Katya October

Pain scales

For adults

Feeling pain is always subjective. People in the same circumstances experience pain differently, not just because people have different pain thresholds. The sensation of pain is influenced by: accompanying emotional and mental disorders, social factors, traditions, habits, access to medical care. Medical anthropologists talk about a different "culture of pain" - someone is ready to endure pain at all costs, someone turns to doctors immediately after discomfort has arisen.

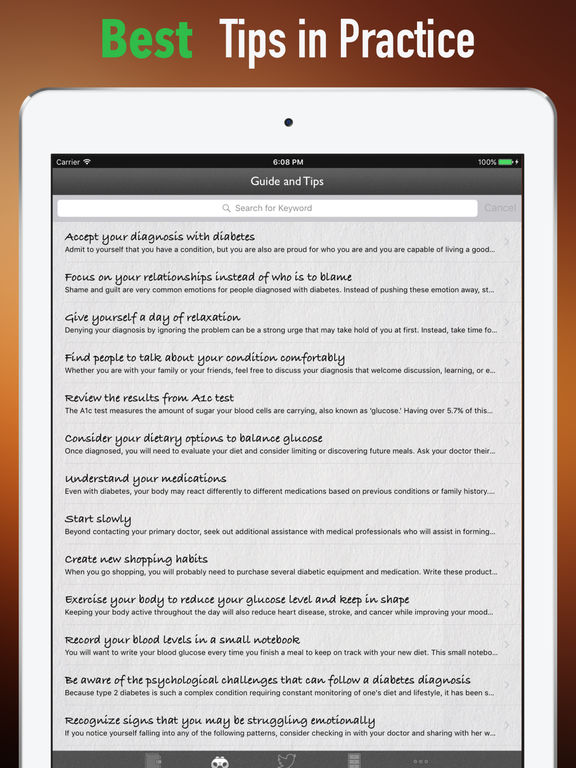

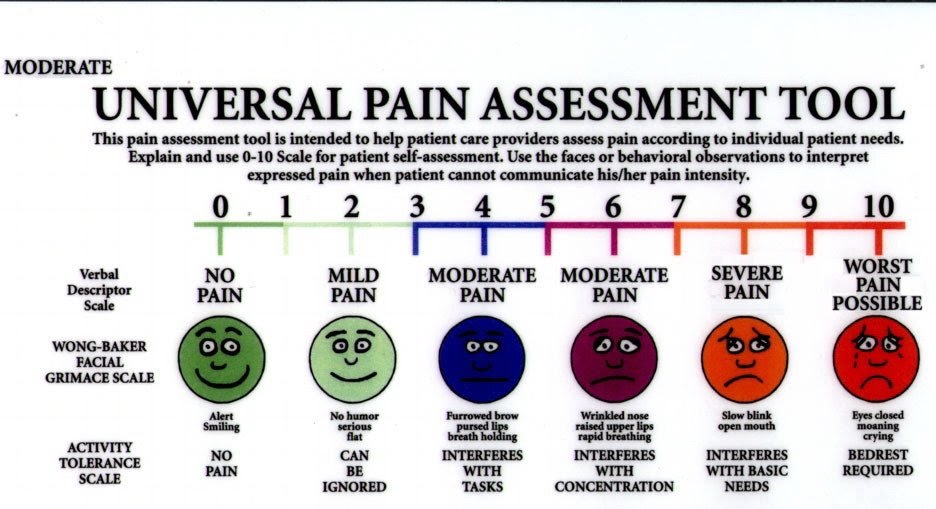

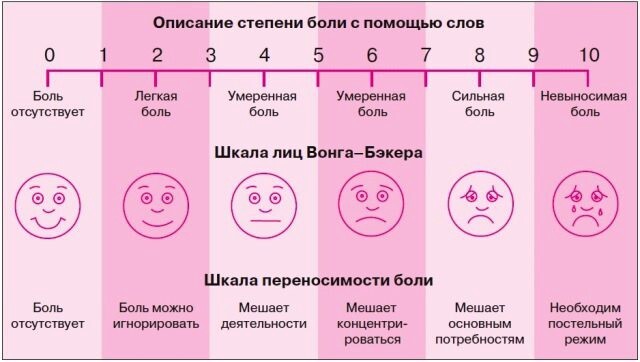

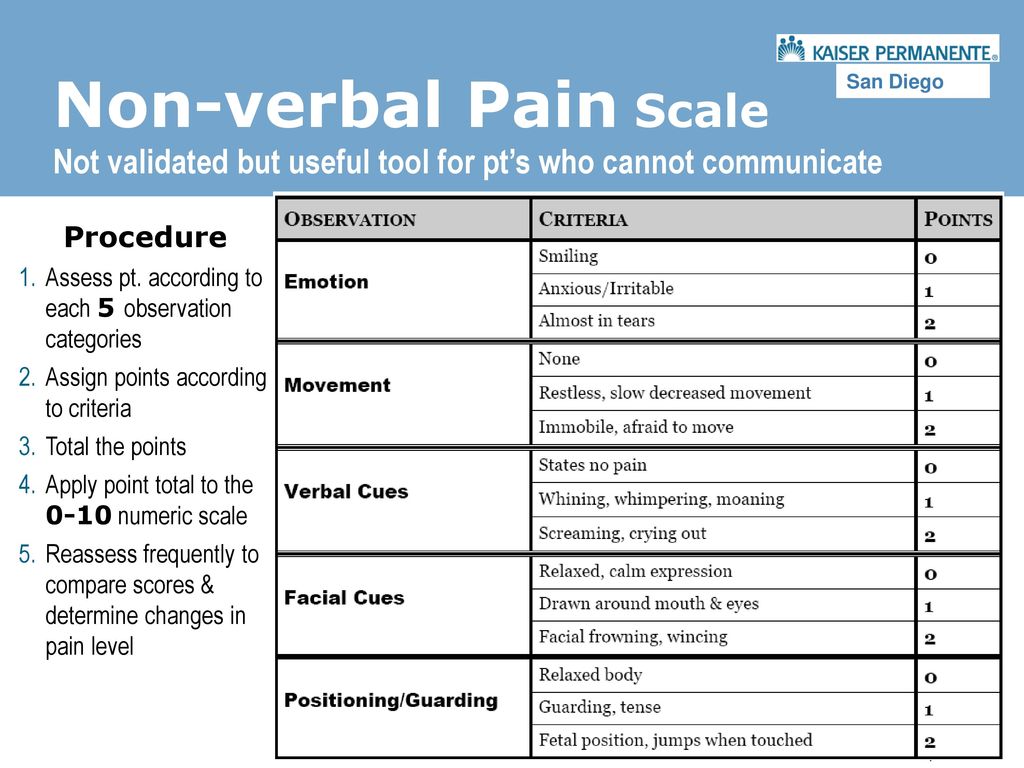

Special scales are used to assess pain. They can be used by doctors, nurses, patients themselves and their loved ones. Scales are selected depending on the age of the patient, his condition and cognitive characteristics. The most popular in the world is the visual analogue scale (VAS), which is a line of 10 segments, where zero means no pain, and 10 means unbearable pain. It is suitable for children who understand the meaning of numbers and adults.

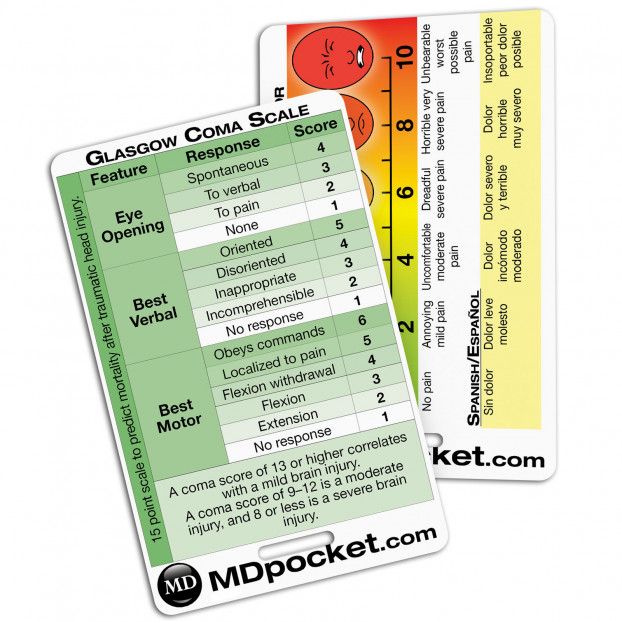

Various scales are used for patients in the intensive care unit, including intubated patients (Behavioral Pain Scale). There are scales that are created for people with various complications and diseases. For people with dementia, the Doloplus 2 scale is used. When assessing pain, you need to pay attention to the position in which the person is at rest, whether sleep is disturbed, whether he allows hygiene procedures, and other indicators.

The Abbey scale is suitable for assessing pain in severe non-verbal patients. It should be used when a person is in motion, for example, during coups, eating or hygiene procedures. The following parameters are important: emitted sounds (crying, moaning, whimpering), facial expressions (tense, frowning), non-verbal signs (fidgeting, detachment), behavior (refusal to eat), physiological changes (sweating, pale skin, fever), physical changes (pressure sores, contractures, arthritis).

It should be used when a person is in motion, for example, during coups, eating or hygiene procedures. The following parameters are important: emitted sounds (crying, moaning, whimpering), facial expressions (tense, frowning), non-verbal signs (fidgeting, detachment), behavior (refusal to eat), physiological changes (sweating, pale skin, fever), physical changes (pressure sores, contractures, arthritis).

Neurosurgeon Mikhail Zonov: “The way a person evaluates his pain is influenced by his experience of experiencing pain in the past. I have had patients who, when they were clearly in severe pain, called 4-5 on the VAS scale. In the conversation, it turned out that these people treated their teeth without anesthesia. And there are patients who, it would seem, not with the most significant pain, called 5 out of 10 according to VAS. It may have been the worst pain of their lives."

Illustration: Katya October

For children

In children, it is difficult to assess the level of pain, especially up to three years. Instead of the word “pain”, the child can name words-definitions close to him, for example, “bo-bo”, and if you ask the child to point to the place of pain, most likely he will point to the stomach, even if his head or throat hurts. Children over 8 years of age are able to describe pain based on their experience, adolescents are able to talk in detail about the causes of pain and talk in detail about pain sensations.

Instead of the word “pain”, the child can name words-definitions close to him, for example, “bo-bo”, and if you ask the child to point to the place of pain, most likely he will point to the stomach, even if his head or throat hurts. Children over 8 years of age are able to describe pain based on their experience, adolescents are able to talk in detail about the causes of pain and talk in detail about pain sensations.

NIPS - Neonatal Infant Pain Scale is used to assess pain in children under one year old. When using it, parents or medical workers are guided by the child's facial expression, crying, breathing, the position of the arms and legs, the state of consciousness. But the result on the scale will be only approximate.

Pediatric scales for older children are numerous. Here are some of them:

- Wong-Baker scale, where the child needs to choose a smiley face that is close to his condition. A sad emoticon hurts, a cheerful one does not hurt;

- Oucher Scale with photographs of children with and without increasing pain;

- Hand scale: if the child does not have pain, he should show his fist, if it hurts a little - one finger, and if the pain is severe - fully open his palm;

- Touch Visual Pain Scale for HIV-infected non-verbal children with multiple organ involvement;

- Eland body tool.

The child determines the intensity of pain with the help of color: severe pain - red, moderate pain - orange, weak pain - yellow. The scale allows you to determine the location of pain.

The child determines the intensity of pain with the help of color: severe pain - red, moderate pain - orange, weak pain - yellow. The scale allows you to determine the location of pain.

It is important to understand that there are no ideal scales. Parents should pay attention to the behavior of the child: did the child eat today, did he refuse to drink, does he want to play or talk, does he cry, how natural is the position in which he is.

Pain is not a necessary companion of the disease

The issue of pain and pain relief is especially common in people with cancer. If at the initial stage of the disease, when the tumor is small and does not cause irritation of the receptors, there may be no pain, then with progression, severe pain may appear suddenly.

Pain may be associated with the formation of a tumor, its germination in the surrounding tissues, with damage to organs and nerves. In addition, pain may occur after surgery or be a reaction to chemotherapy. For a patient with oncology, the doctor should prescribe pain relief therapy according to an increasing scheme - from a weak analgesic to a strong one, depending on whether the prescribed drug worked or not. At the first stage of anesthesia are paracetamol and ibuprofen, at the second - tramadol, at the top - morphine and fentanyl.

For a patient with oncology, the doctor should prescribe pain relief therapy according to an increasing scheme - from a weak analgesic to a strong one, depending on whether the prescribed drug worked or not. At the first stage of anesthesia are paracetamol and ibuprofen, at the second - tramadol, at the top - morphine and fentanyl.

Many myths are associated with the prescription of narcotic painkillers: “This is how you can become addicted”, “Pain is an obligatory part of the disease, you have to endure it” and even “Hair will fall out!”. Firstly, addiction can be avoided by proper selection of the drug and dosage, as well as gradual withdrawal if necessary. If a person has not abused drugs during their lifetime, then the risk of developing opioid dependence from treatment is minimal.

Secondly, pain cannot be (and almost impossible in oncology) tolerable, it worsens the work of the heart and digestive system, increases blood pressure and depresses the psycho-emotional state. A person in severe pain can only lie down and suffer from their sensations. Thirdly, hair loss in people with cancer is not associated with taking painkillers, but with receiving chemotherapy, and this is reversible.

A person in severe pain can only lie down and suffer from their sensations. Thirdly, hair loss in people with cancer is not associated with taking painkillers, but with receiving chemotherapy, and this is reversible.

If the patient follows the recommendations of doctors, he can lead an active life and not concentrate on the disease. Perhaps every evidence-based oncologist has a story about how he persuaded a patient to start taking morphine for a long time, the patient refused until the condition became very serious. And when he agreed, he cheered up, began to communicate with loved ones again, felt a return to life.

Text: Diana Karliner. The material was published in the fifth issue of the Three Sisters magazine.

The Three Sisters Clinic treats acute and chronic pain. We can arrange a consultation with our neurologist or neurosurgeon, perform pain relief procedures on an outpatient basis or offer a comprehensive pain management program that includes not only pain relief, but also physical therapy, massage, aqua therapy.