Self harm as punishment

Why It Doesn't Work and Alternatives

You’ve done something that hurt someone else, perhaps even yourself. You regret it, but you can’t take it back, so you wait for someone to notice and provide some sort of correction to relieve your guilt.

Mistakes of any kind often provoke criticism from others, though more significant errors might trigger a harsher critique, or punishment.

Maybe you don’t enjoy this punishment, whether it involves offering an apology or doing act of kindness. But once it’s over, you probably feel much better. After all, you’ve atoned for your misdeed and earned forgiveness.

When no one catches your slip-up, your guilt might linger. If you don’t feel able to own up, for whatever reason, you might look for ways to self-punish in order to relieve your guilt.

It might feel like the only logical move in the moment, but self-punishment tends to do more harm than good.

Self-punishment comes in many forms. At its most extreme, it might involve some type of self-harm.

But it could also refer to:

- withholding a reward

- lecturing yourself mentally

- continuing to dredge up bad feelings long after a regrettable decision

Where does this urge come from? Cultural messages and other complex factors can contribute, so there’s not always a simple answer. The following explanations often play a part, though.

We believe suffering improves our character

The desire to become a better person is fairly common. While this goal is an admirable one, it often involves some emotional distress: You wish you were better, so you punish yourself for failing to improve.

Many people see pain (physical or emotional) as a way to restore integrity and virtuousness. You might see punishment from someone else as a deserved, just action that absolves you of your “sins.”

Undergoing suffering in the form of self-punishment can seem like a similarly productive way to pay for mistakes. By holding yourself accountable when no one else does, you show remorse and restore your personal sense that you aren’t, in fact, a bad person.

We believe we deserve it

Children often learn shame at an early age. You might feel the first stirrings when parents or other caregivers suggest your behavior violates their expectations or broader social norms.

It’s not always easy to separate shame from guilt, particularly when they show up together, but here’s one helpful way of looking at it: Guilt typically relates to actions, while shame usually relates to self-identity.

You might experience guilt after a specific mistake, while shame describes a general sense of yourself as unworthy.

These feelings of unworthiness can prompt self-punishment, even if you can’t trace them back to anything specific. As 2015 research points out, people more prone to shame tend to punish themselves more readily.

We want to relieve guilt

In some cases, you might hesitate to come clean after a mistake, believing this would only cause more pain.

When you feel guilty for thoughts you can’t express or actions you can’t apologize for, you might see self-punishment as a way of redeeming yourself, at least in your own eyes.

In a small study from 2010, participants asked to recall an instance of unethical behavior and then complete a painful task (leaving their hand in a bucket of ice water for as long as they could) reported less guilt after their “punishment.”

Additional research from 2017 also explored the link between guilt and self-punishment. It suggested that people who felt guilty about keeping secrets from their romantic partners often attempted to relieve that guilt by denying themselves enjoyable activities or taking less pleasure them.

Punishment isn’t always the most effective tool, but there are times when it can lead to personal growth.

For motivation

Say you’ve promised yourself you’ll take the afternoon to relax at the beach after you get your work done. You dedicate the morning to work, but for some reason, you just can’t focus and you end up getting very little done.

When the afternoon rolls around, instead of taking off to the beach, you stay home and make a renewed effort to finish up.

Denying yourself the planned trip provides a second chance to do what you need to do and motivates you to stay on task next time you’ve planned something fun.

For changing behavior

Self-punishment could also encourage you to address problematic behavior.

Perhaps you and a few work friends decide to play a prank on a coworker. “Just some harmless fun,” you tell yourselves, but the prank really upsets your coworker. They disappear into the bathroom, avoiding everyone for the rest of the day.

They never find out you were involved, but you still want to make amends. You arrange for an anonymous delivery of their favorite candy and take them out to lunch later that week.

Next time someone mentions a prank, you remember your coworker’s embarrassment and decline to participate.

While some forms of self-punishment might be useful, the problem is that it can easily become a harmful cycle that’s hard to get out of.

Instead of forgiving yourself for normal human errors, you might begin fixating on even minor slip-ups, offering unkind judgment instead of a self-loving “I’ll do better next time. ”

”

It doesn’t always resolve the problem

Say you feel guilty because you lied to someone or did something you want to keep secret. Punishing yourself might reduce your guilt and help you feel better. Yet it doesn’t address the real issue — the thing you’re hiding.

In the future, you might find yourself lying again in order to maintain your deception. This lie creates more guilt, which you may attempt to resolve with more self-punishment. A pretty unpleasant cycle, to say the least.

It can create more distress

Consider your canceled trip to the beach. If you spend the afternoon criticizing yourself for your earlier distraction, you might still struggle to complete your work.

By the end of the day, you feel pretty miserable. You missed out on something you were looking forward to, and you still have tons of work to finish.

The negative self-talk playing on repeat in your head also has you feeling as if you can’t do anything right.

Instead of resolving to try again tomorrow, you decide you don’t deserve any rewards and throw yourself into your work instead.

This pattern will likely leave you feeling drained and burnt out, which can take a much bigger toll on your work than an afternoon at the beach.

Not sure if your approach to self-punishment lies more in the motivational self-improvement category or the unhelpful and potentially harmful one?

This can sometimes prove a little challenging, but asking yourself these questions can help:

- Is this behavior constructive? Will the thing you’re doing actually help you improve, or just make you feel worse?

- What’s keeping me from making amends in person? Generally speaking, confessing your mistake is usually best, if you have that option.

- Will this behavior contribute to lasting harm? Negative self-talk, self-harm, excessive exercise, and skipping meals are all forms of self-punishment that can have lasting effects on emotional and physical health.

- Does this behavior replace healthy self-care? Punishment that keeps you from taking care of yourself is never helpful.

Working late into the night, for example, might seem a good way to compensate for distraction, but this can quickly disrupt your sleep and affect your health.

Working late into the night, for example, might seem a good way to compensate for distraction, but this can quickly disrupt your sleep and affect your health.

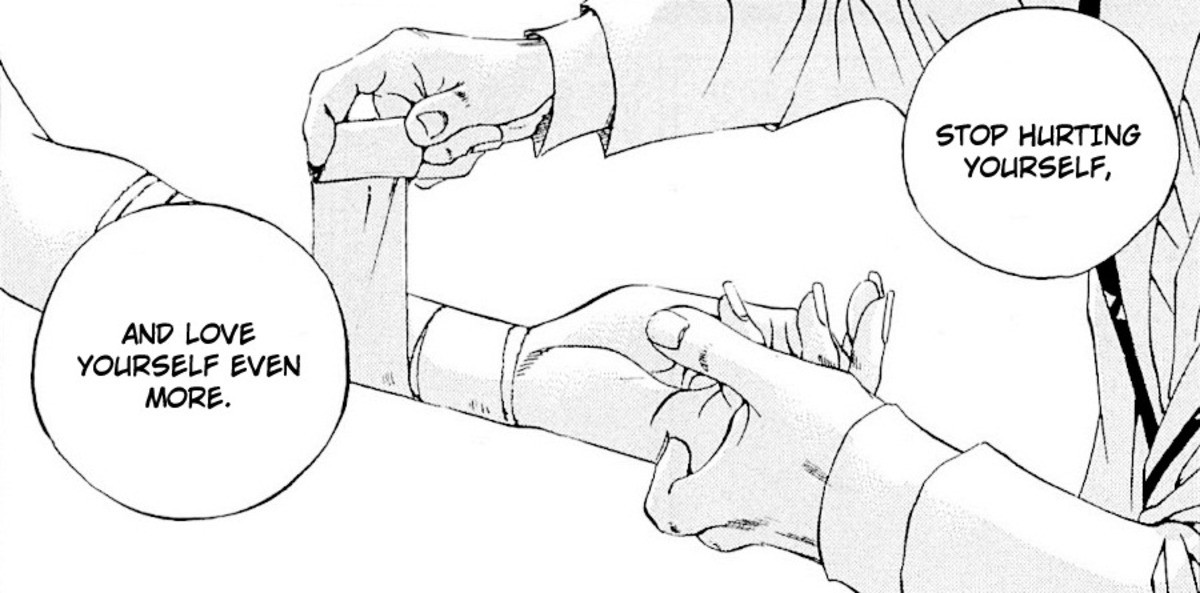

Self-punishment could help relieve guilt after you do something you’re not proud of. But it may not do much to improve your overall feelings about yourself, especially if you also have feelings of shame and low self-worth.

Thankfully, self-compassion offers a beneficial alternative. Not only does it help you get more comfortable with the idea that mistakes are merely part of being human, but it also helps you learn to love yourself regardless of your perceived flaws.

Self-compassion can also help ease even long-held pain and promote self-worth, making it easier to treat yourself with love and kindness. Over time, greater self-regard can improve your faith in your ability to make positive change.

Practice self-forgiveness

It’s easy to cling to self-blame after wrongdoing. If you don’t feel worthy of forgiveness, you might struggle to let your mistake go.

Try to keep in mind that life involves the occasional error, and you deserve a chance to try again (and again, and again, if needed) to show yourself you can indeed do better.

Reframing your mistakes as opportunities for growth, rather than failures, can also make it easier to practice forgiveness toward yourself.

You can only ever do your best. Even if your best falls short of what you envision for yourself, you can still use what you’ve learned to guide your choices in the future.

Reward yourself

Most people are pretty good at rewarding themselves when they believe they’ve done something right, but sometimes self-compassion involves rewarding yourself even when you think you’ve done something wrong.

Next time you feel guilty for getting distracted at work, ask yourself if your lack of focus means you really need a break.

A trip to the beach might seem like a treat, but the exercise, sunshine, and time in nature it involves can also help improve your mood, potentially increasing productivity.

Treating yourself with kindness makes it easier to acknowledge and respect your needs instead of punishing yourself for having them.

Make it a habit

It can take some time to get the hang of self-compassion, but you’ll usually notice it comes more easily with practice.

Build up self-compassion skills by:

- practicing affirmations

- keeping a journal

- trying loving-kindness meditation

- taking time for relaxation and self-care

A long-standing pattern of self-punishment might be tough to overcome alone, particularly when it relates to shame, unworthiness, or difficulty forgiving yourself.

If guilt causes significant emotional distress, affects your relationships, or keeps you from finding enjoyment in life, professional support can make a big difference.

Therapy provides a safe space to address:

- memories that trigger guilt and shame

- self-harm and other unhelpful self-punishment behaviors

- negative self-talk

A therapist can help you explore healthier approaches to managing and resolving guilt, including self-compassion and resilience.

When your harshest critic is yourself, self-punishment might seem like the best path toward atonement. You’ll usually find, though, the compassionate route results in a more productive journey.

Crystal Raypole has previously worked as a writer and editor for GoodTherapy. Her fields of interest include Asian languages and literature, Japanese translation, cooking, natural sciences, sex positivity, and mental health. In particular, she’s committed to helping decrease stigma around mental health issues.

Harm | Crisis Text Line

Text A Crisis Counselor

Message A Crisis Counselor on WhatsApp

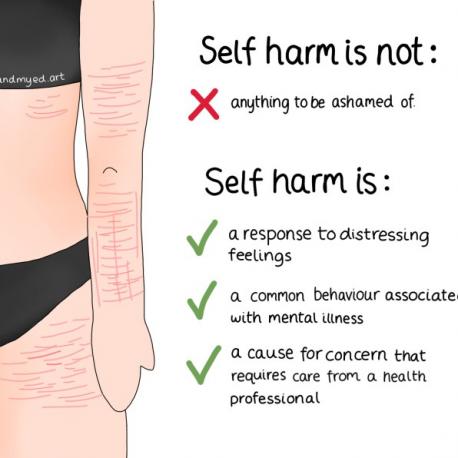

What is Self-Harm?

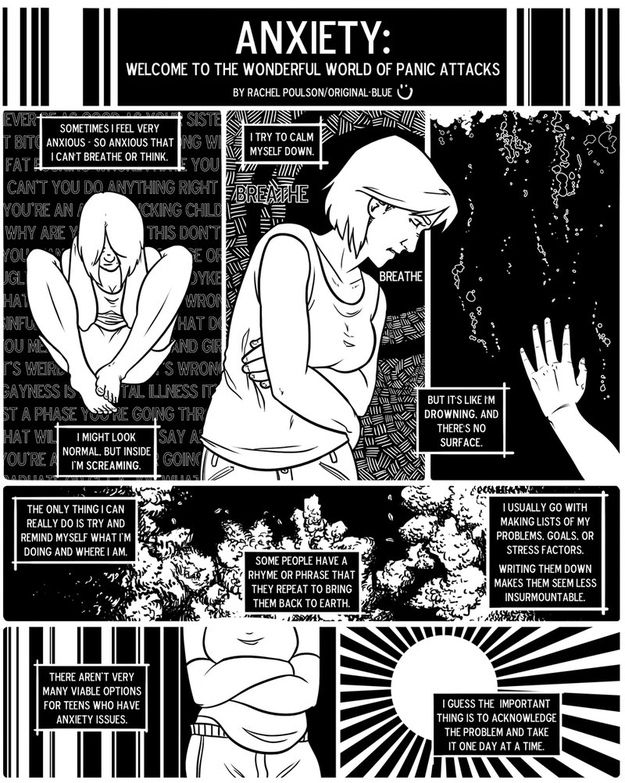

For some people, when depression and anxiety lead to a tornado of emotions, they turn to self-harm looking for a release. Self-harm and self-injury are any forms of hurting oneself on purpose. Usually, when people self-harm, they do not do so as a suicide attempt. Rather, they self-harm as a way to release painful emotions.

Types of Self-Harm

Self-harm can manifest differently for everyone. And, the ways people may self-harm extend far beyond the usual references to cutting in media. Simply, self-harm is anything and everything someone can do to purposely hurt their body.

Here are some of the most common types of self-injury:

- Cutting

- Scratching

- Burning

- Carving words or symbols into the skin

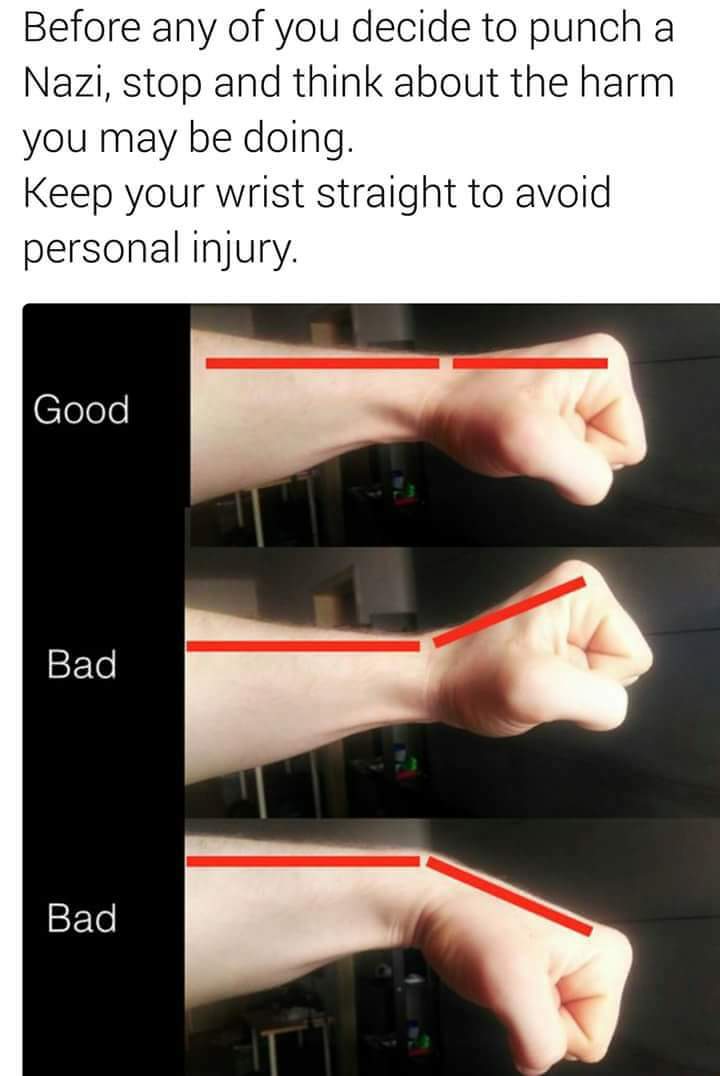

- Hitting or punching oneself (including banging one’s head or other body parts against another surface)

- Piercing the skin with sharp objects such as hairpins

- Pulling out hair

- Picking at existing wounds

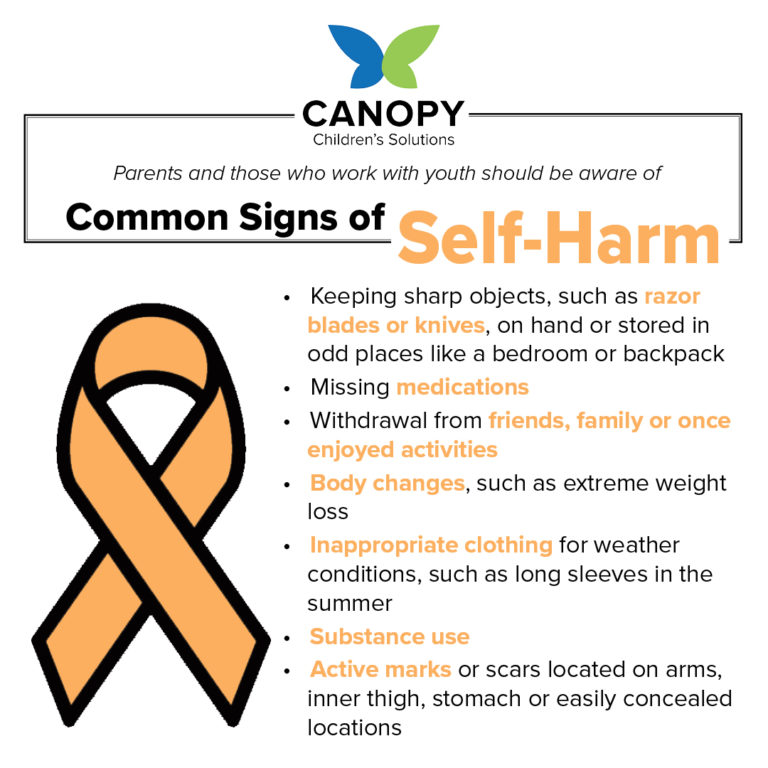

Symptoms of Self-Harm

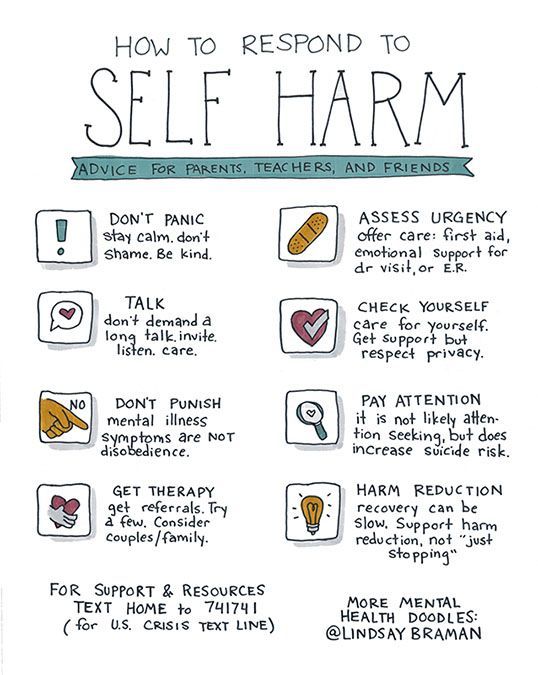

Stigma creates shame and embarrassment, making it hard for people who self-harm to get help. So, look out for yourself and for your pals. If you suspect that someone in your life is self-harming, here are some warning signs to keep top of mind:

- Scars

- Fresh cuts, burns, scratches, or bruises

- Rubbing an area excessively to create a burn

- Having sharp objects on hand

- Wearing long sleeves or long pants, even in hot weather

- Difficulties with interpersonal relationships

- Persistent questions about personal identity

- Behavioral and emotional instability, impulsiveness, or unpredictability

- Saying that they feel helpless, hopeless, or worthless

Crisis Text Line can help you deal with self-harm. Text a Crisis Counselor at 741741, or use the mobile text button below.

Text a Crisis Counselor at 741741, or use the mobile text button below.

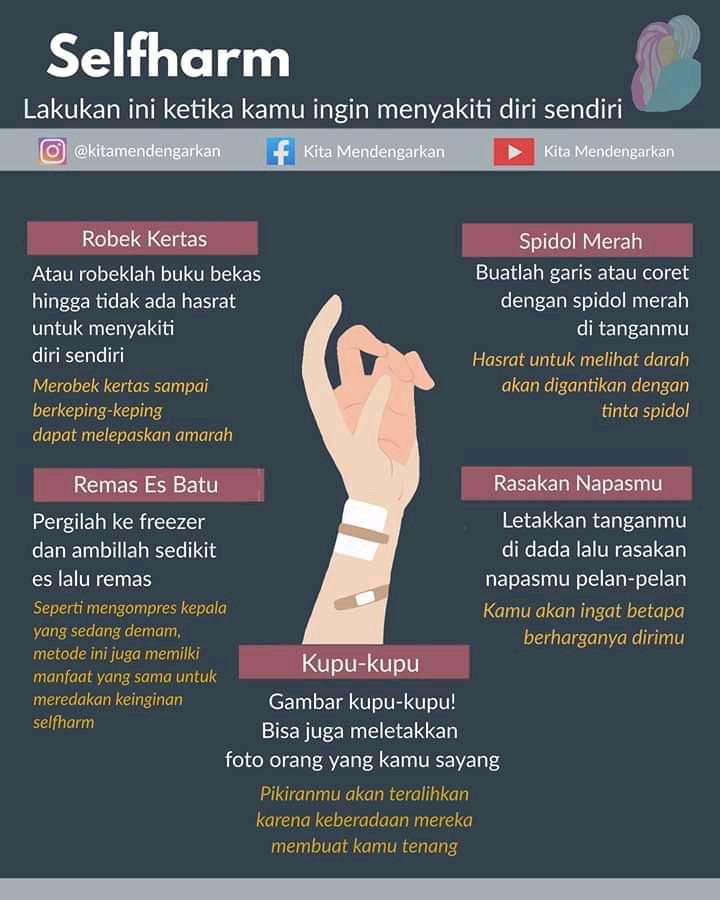

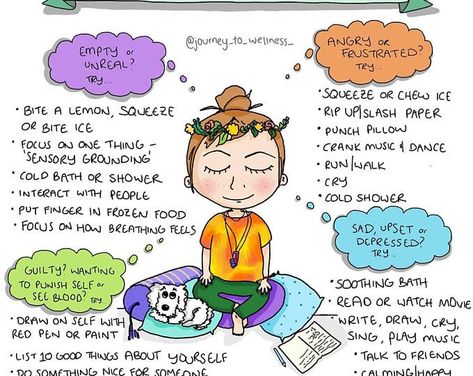

How to Deal With Self-Harm

Emotions can be really painful sometimes. It’s totally normal to need ways to cope with and process the hard things in your life. If you are using self-harm to manage your emotions, we’re here for you. And, we want to help keep you safe.

Here are some ways to push through, process, and cope with your emotions.

- Text to cool down. If you’re dealing with painful emotions, we’re here to help. Shoot us a text to connect with a real human and strategize healthy coping mechanisms to manage your emotions. Text HOME to 741741 to connect with a real human.

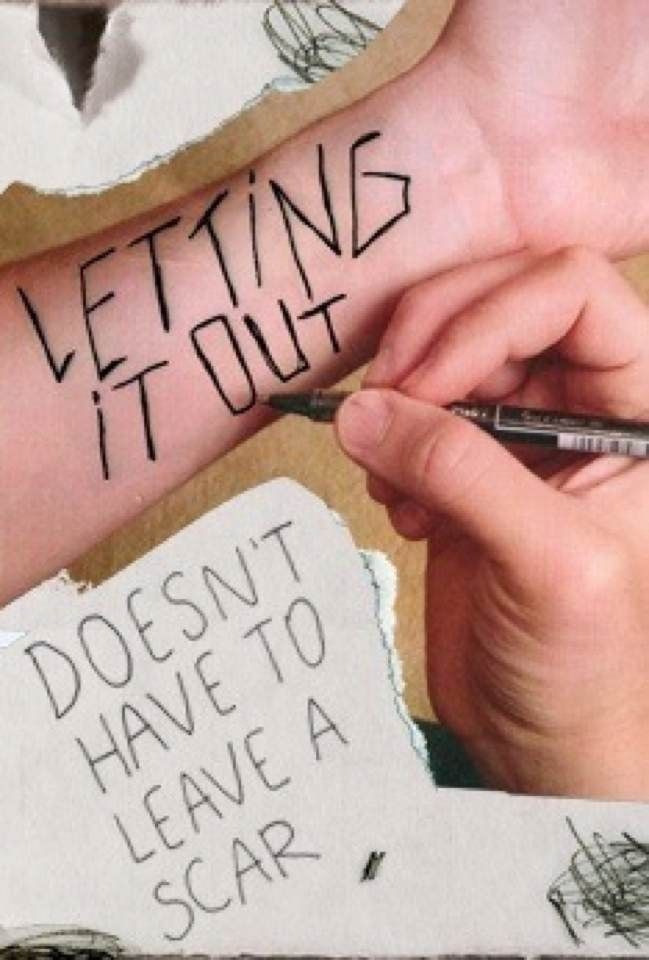

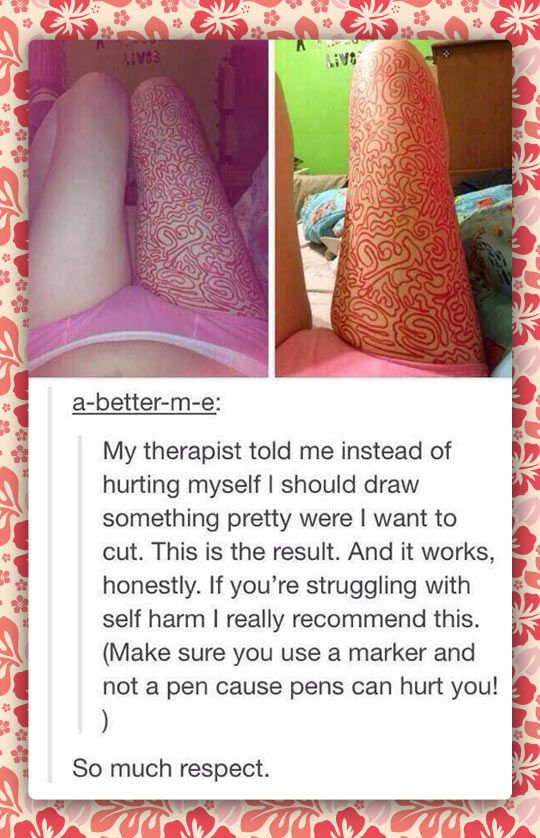

- Get creative. Studies show that diving into making art can help people process emotions. So, next time you’re feeling like self-harming, grab your sharpie and doodle your worries away. A bonus: you can totally suck at it and still reap the same rewards.

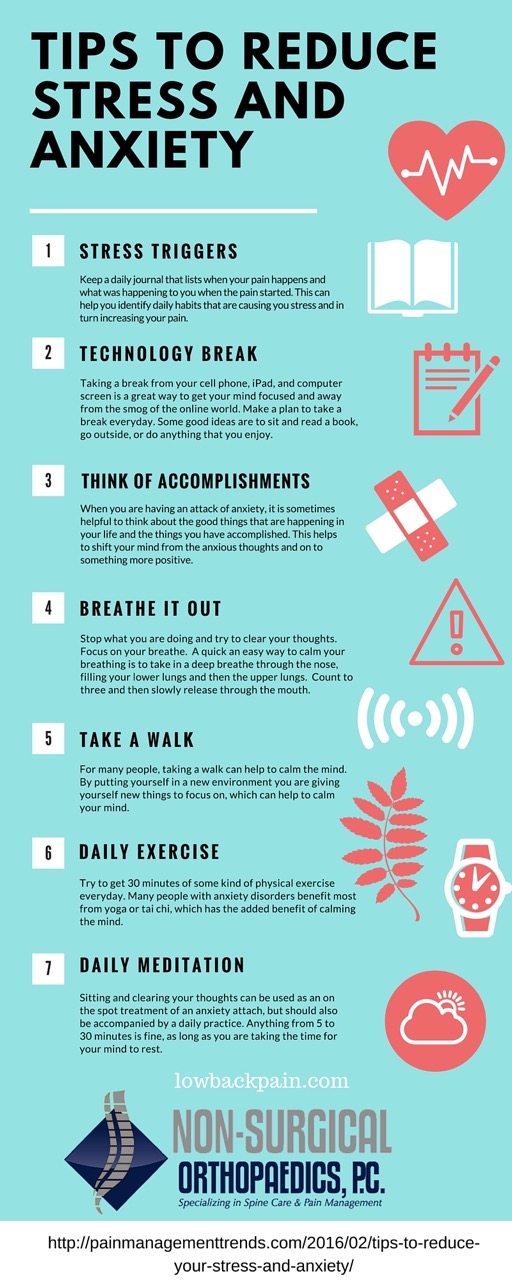

- Find your zen.

Keeping yourself safe from self-harming is all about finding healthy alternatives to work through the hard stuff. Researchers found taking time to re-center through meditation to be a powerful way to find your cool and calm. Try using an app like Headspace to get on the meditation bandwagon.

Keeping yourself safe from self-harming is all about finding healthy alternatives to work through the hard stuff. Researchers found taking time to re-center through meditation to be a powerful way to find your cool and calm. Try using an app like Headspace to get on the meditation bandwagon. - Talk to a pro. Self-harm is serious. And, while the intention behind self-harm usually is not death, it can still be dangerous—both physically and emotionally. Talking to someone who can help you find alternatives is incredibly important. Of course, you can start by texting us. Also, consider telling someone you know who can help you connect with a professional.

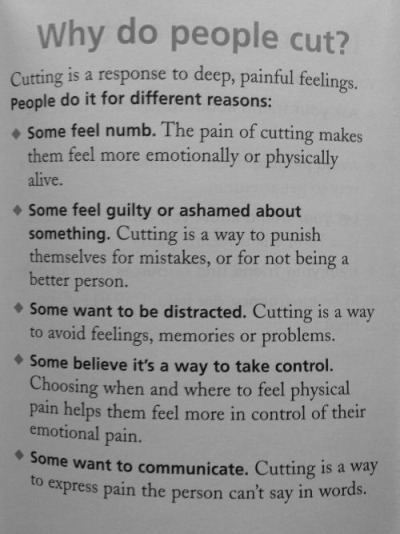

Why Do People Self-Harm?

Let’s start with this: everyone needs a way to cope with their emotions. People who self-harm have turned to hurting themselves as their coping mechanism to manage their emotions.

So, people might self-harm to:

- Process their negative feelings

- Distract themselves from their negative feelings

- Feel something physical, particularly if they are feeling numb

- Develop a sense of control over their lives

- Punish themselves for things they think they’ve done wrong

- Express emotions that they are otherwise embarrassed to show

Effects of Self-Harm

Self-harm can be seriously dangerous—physically, emotionally, socially, all of it.

Physical Effects of Self-Harm

- Permanent scars

- Uncontrolled bleeding

- Infection

- Emotional Effects of Self-Harm

- Guilt or shame

- A diminished sense of self, including feeling helpless or worthless

- Addiction to the behavior

Social Effects of Self-Harm

- Avoiding friends and loved ones

- Becoming ostracized from loved ones who may not understand

- Interpersonal difficulty from lying to others about injuries

Recovering from Self-Harm

A lot of people who self-harm do so because they are dealing with painful emotions. If this applies to you, hi—we believe in you and recognize your pain. Because painful emotions are at the root of self-harm, quite often recovering from self-harm involves addressing emotions.

Breaking away from the cycle of self-harm can feel like a huge climb. It involves breaking a habit that has once brought comfort from pain. But, it is not impossible. Here are some steps to set you up for success:

But, it is not impossible. Here are some steps to set you up for success:

- Name your reason for hurting yourself and your reason for quitting. Ask yourself: “What do I feel before, during, and after self-injury? Which of those emotions do I actively seek out, and which are harmful?”

- Identify other ways of achieving the same result. For example, if you self-harm for the physical sensation, seek other ways of releasing endorphins, like exercise. For real, try throwing a few punches at a kickboxing class or tapping it back in a spin class with the *perfect* playlist. If you self-harm to express your emotions, practice expressing them in words by writing them down. Grab a pen and your favorite notebook, or start typing away in your notes app.

- Tackle the underlying emotions. Explore the feelings that lead you to want to hurt yourself. If it’s guilt, where is that guilt coming from? Maybe try finding a therapist—there are pros trained specifically to help with this.

- Tell someone you trust. Let a friend, family member, or trusted adult know what you’re going through and that you need their support. Opening up to people can be easier said than done. Here’s a place to start: “I’m having a hard time processing some painful emotions and I could use your support right now.”

Getting healthy—both in your brain and in your body—takes hard work. You got this. And, we believe in you.

Text a Crisis Counselor at 741471 or use the mobile click to text button below. You’re not alone.

Pass 741741 On To A Friend

You never know who might need Crisis Text Line. Pass it on and tell the people in your life to text HOME to 741741 if they’re ever in crisis.

The prosecutor explains - The Prosecutor's Office of the Saratov region

nine0003 Prosecutor explains

- February 20, 2021, 10:22

Prosecutor's office of Balashov: On criminal liability for evasion of military service duties by feigning illness or in other ways

Text

Share

Article 339 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation (hereinafter referred to as the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation) provides that if a serviceman evades military service duties by feigning illness, or inflicting any injury on himself (mutilation), forgery of documents or other deceit, such a person is assigned punishment in the form of restriction in military service for a term of up to one year, or arrest for a term of up to six months, or detention in a disciplinary military unit for a term of up to one year (part 1). nine0005

nine0005

If a citizen has committed such an act in order to completely exempt himself from the performance of military service duties, he is subject to criminal liability in the form of imprisonment for up to seven years.

Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation No. 3 dated April 3, 2008 (as amended on December 23, 2010) “On the practice of court consideration of criminal cases on draft evasion and military or alternative civilian service evasion” explains that the duration evasion from the performance of duties of military service for the composition of the completed crime does not matter. nine0005

In addition, if a person pursued the goal of completely freeing himself from military service duties, however, the crime was not completed due to circumstances beyond his control, the deed should be qualified under part 1 or part 3 of article 30 and part 2 of article 339 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation . For example, if a person is found to have tools or means for committing self-mutilation, their search is qualified as preparation for evading military service duties in this way. If the forgery of documents, on the basis of which a person was subject to early dismissal from military service, was discovered by the command, the deed should be qualified as an attempted crime under part 2 of article 339Criminal Code of the Russian Federation.

If the forgery of documents, on the basis of which a person was subject to early dismissal from military service, was discovered by the command, the deed should be qualified as an attempted crime under part 2 of article 339Criminal Code of the Russian Federation.

Prosecutor of Balashov A.V. Dementyev

Prosecutor's Office of Balashov: On criminal liability for evasion of military service duties by feigning illness or other means

Article 339 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation (hereinafter - the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation) provides that if a serviceman evades military service duties by feigning illness, or inflicting any injury on himself (mutilation), forgery of documents or other deceit, such a person is punished in in the form of restriction in military service for a term of up to one year, or arrest for a term of up to six months, or detention in a disciplinary military unit for a term of up to one year (Part 1). nine0005

nine0005

If a citizen has committed such an act in order to completely exempt himself from the performance of military service duties, he is subject to criminal liability in the form of imprisonment for up to seven years.

Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation No. 3 dated April 3, 2008 (as amended on December 23, 2010) “On the practice of court consideration of criminal cases on draft evasion and military or alternative civilian service evasion” explains that the duration evasion from the performance of duties of military service for the composition of the completed crime does not matter. nine0005

In addition, if a person pursued the goal of completely freeing himself from military service duties, however, the crime was not completed due to circumstances beyond his control, the deed should be qualified under part 1 or part 3 of article 30 and part 2 of article 339 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation . For example, if a person is found to have tools or means for committing self-mutilation, their search is qualified as preparation for evading military service duties in this way. If the forgery of documents, on the basis of which a person was subject to early dismissal from military service, was discovered by the command, the deed should be qualified as an attempted crime under part 2 of article 339Criminal Code of the Russian Federation.

If the forgery of documents, on the basis of which a person was subject to early dismissal from military service, was discovered by the command, the deed should be qualified as an attempted crime under part 2 of article 339Criminal Code of the Russian Federation.

Prosecutor of Balashov A.V. Dementiev

Self-mutilation of a convict as a basis for refusing to release from punishment due to illness

Bibliographic description:

Borodulkina, E. S. Self-mutilation of a convict as a basis for refusal to release from punishment due to illness / E. S. Borodulkina. - Text: direct // Young scientist. - 2014. - No. 17 (76). - S. 373-376. — URL: https://moluch.ru/archive/76/13105/ (date of access: 01/12/2023).

Introduction. In the Republic of Belarus, cases are not uncommon when convicts, while in institutions of the penitentiary system (hereinafter referred to as the penitentiary system), intentionally harm their health. This may be "self-mutilation", deliberate "aggravation" of diseases (intensification of painful symptoms), deliberate self-infection. nine0005

This may be "self-mutilation", deliberate "aggravation" of diseases (intensification of painful symptoms), deliberate self-infection. nine0005

Researchers name many reasons contributing to such non-suicidal self-destructive behavior [1, p. 17] convicts: the desire to avoid the fulfillment of security requirements, work duties, the imposition of a disciplinary sanction; the desire to fall under the regime of medical care to receive benefits, additional rights; "change of scenery", providing access to painkillers, other medicines; solving personal issues related to the need to meet with other convicts [2, p. 40], demonstration of “protest” or early release from serving a sentence for health reasons [3, p. 156]. nine0005

In the framework of this study, we propose to consider situations where, as a result of self-harm, a convict acquires diseases that can serve as a basis for his release on the grounds provided for in Art. 92 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Belarus (hereinafter - the Criminal Code). In particular, we will consider the question of whether it is advisable to find out and subsequently take into account in court how the disease was acquired; whether a proven act of self-harm should be an unconditional ground for denial of sick leave. nine0005

In particular, we will consider the question of whether it is advisable to find out and subsequently take into account in court how the disease was acquired; whether a proven act of self-harm should be an unconditional ground for denial of sick leave. nine0005

Main part. It is important for the purposes of this study to clarify the content of the terms "self-harm", "self-harm", which will ensure an adequate reflection of the terminology about causing harm to convicts to their health in the legislation.

Quite often, self-harm is identified with self-harm, and in this case, both terms mean deliberate actions of persons to inflict various types of injuries on themselves [4, p. 67]. In accordance with the provisions of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems - 10th revision (ICD-10), self-harm and self-harm are also used as synonyms [5]. At the same time, the point of view that “self-harm” is the infliction of damage (not to the members of a person, but to areas of the body and organs) to oneself and no one else seems to be argued, which distinguishes self-harm from self-harm [6]. nine0005

nine0005

However, in our opinion, it is reasonable to use a broader wording - "intentional infliction of harm to one's health", which will include various types of damage. For example, in addition to self-mutilation, self-harm, the above-mentioned “self-infection” can be summed up under this wording.

It should be noted that rarely in case of self-harm, the disease immediately acquires that severe form, which makes it possible to release the person from punishment. For this case, in the text of the International Statistical Classification there is a mention of "the consequences of intentional self-harm that developed a year or more after the event" [5]. With the acceptable wording we have indicated, we can take into account "the consequences of intentionally causing harm to one's health that developed after the event." nine0005

Despite the fact that the Internal Rules of Correctional Institutions, approved by the Decree of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Republic of Belarus dated October 20, 2000 No. 174, contain a ban on self-mutilation by convicts (clauses 58. 22), in terms of resolving the issue of When exempting from punishment, the Belarusian legislator does not attach legal significance to the causes of the disease in persons serving sentences. Neither in the Criminal Code of the Republic of Belarus, nor in the Instructions on the procedure for medical examination of convicts and the establishment of a list of diseases that impede the further serving of a sentence, approved by the Decree of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Republic of Belarus and the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Belarus dated February 16, 2011 No. 54/15 (hereinafter - the List ), the need to take into account the intentional infliction of harm to one's health by a person serving a sentence is not indicated. nine0005

174, contain a ban on self-mutilation by convicts (clauses 58. 22), in terms of resolving the issue of When exempting from punishment, the Belarusian legislator does not attach legal significance to the causes of the disease in persons serving sentences. Neither in the Criminal Code of the Republic of Belarus, nor in the Instructions on the procedure for medical examination of convicts and the establishment of a list of diseases that impede the further serving of a sentence, approved by the Decree of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Republic of Belarus and the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Belarus dated February 16, 2011 No. 54/15 (hereinafter - the List ), the need to take into account the intentional infliction of harm to one's health by a person serving a sentence is not indicated. nine0005

A different approach is demonstrated by the legislation of the Russian Federation (hereinafter referred to as the Russian Federation). Despite the fact that according to Art. 81 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, the possibility of exemption from punishment in case of a serious non-mental illness is not related to other criteria, in addition to medical (the disease itself), in paragraph 24 of the Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation dated April 21, 2009 No.![]() 8 "On the judicial practice of parole from serving punishment, replacing the unserved part of the punishment with a milder type of punishment "it is stated that" if the disease of the convict occurred as a result of his intentional actions (for example, self-mutilation) with the aim of subsequent release, he is not subject to release from serving the sentence on the grounds provided for in Art. 81 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation. nine0005

8 "On the judicial practice of parole from serving punishment, replacing the unserved part of the punishment with a milder type of punishment "it is stated that" if the disease of the convict occurred as a result of his intentional actions (for example, self-mutilation) with the aim of subsequent release, he is not subject to release from serving the sentence on the grounds provided for in Art. 81 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation. nine0005

Analyzing this paragraph, one should pay attention to the fact that the convict must be denied mandatory release only if the person pursued the goal of early release, while if the convict pursued a different goal, then in fact he can be released . In our opinion, such a wording can cause difficulties in practice, since it will be difficult to unequivocally establish the purpose of self-harm, and in the event of the slightest mistake, the decision to refuse release will be cruel and unfair in relation to the seriously ill convict. nine0005

Another significant shortcoming of the norm is rightly pointed out by A. P. Skiba. From the content of paragraph 24 of the above Resolution, it follows that if the convict, due to self-mutilation committed with the aim of subsequent release, ceased to realize the actual nature and social danger of his actions or to control them, then he must still be released from punishment due to illness, regardless of what caused his mental disorder. In this case, the Decree of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation contradicts not only the provisions of the law, but is also illogical, since the provision of corrective action on such a person is meaningless [3, p. 234–235]. nine0005

P. Skiba. From the content of paragraph 24 of the above Resolution, it follows that if the convict, due to self-mutilation committed with the aim of subsequent release, ceased to realize the actual nature and social danger of his actions or to control them, then he must still be released from punishment due to illness, regardless of what caused his mental disorder. In this case, the Decree of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation contradicts not only the provisions of the law, but is also illogical, since the provision of corrective action on such a person is meaningless [3, p. 234–235]. nine0005

We agree with the opinion of the scientist and note that if, nevertheless, the legislation contains a ban on the release of sick people, in the event that the disease occurred as a result of self-mutilation, then there should be a reservation regarding those whom this restriction does not apply to, namely those who has acquired a mental disorder, which makes it possible to release a sick person from punishment.

Despite the indicated shortcomings of the legislative regulation of this problem, most Russian scientists agree that in case of causing serious harm to their health, convicts should be denied release from punishment, since the encouragement of such actions (in the form of the release of such convicts) can serve incentive for their distribution [7, p. 139; 8, p. 46; 9, p. 40].

On the one hand, indeed, one can support the point of view that the presence of such a norm can be a significant deterrent when convicts commit such actions, on the other hand, it is worth analyzing whether the number of diseases that can be obtained as a result of self-mutilation is so large.

Analyzing specific diseases from the List, in the presence of which the court may decide to release a person, it can be assumed that, for example, tuberculosis can be a disease obtained as a result of self-infection. Sometimes convicts actually make successful attempts to acquire such diseases [10, p. 21]. nine0005

21]. nine0005

For an adequate assessment of the possible wide spread of self-harm among convicts, we consider it necessary to present the results of a study by O. A. Alfimova. According to the conclusions made by the scientist, no serious somatic diseases, provided for in the Russian List of Diseases, as a result of infliction of harm to their health by convicts, were identified. As a result of self-harm, convicts most often inflicted injuries in the form of cut, stab and stab wounds with different localization (most often in the forearm, neck, abdomen, chest, thighs) [11, p. 165]. Belarusian scientists V. B. Shabanov and M. Yu. Kashinsky come to a similar conclusion about the forms of self-mutilation. It was found that in the Republic of Belarus the range of manifestations of self-harm (self-harm) in places of deprivation of liberty is quite wide, however, the most “spectacular” methods of self-harm prevail, usually not requiring specialized medical care: infliction of superficial stab wounds, burns of I, II degrees, driving sharp objects into the body and fractures of limbs, as well as demonstrative suicide attempts [1, p. nineteen].

nineteen].

Moreover, despite the fact that the rule on the ban on the release of persons who have resorted to self-mutilation is in force on the territory of the Russian Federation, A.P. Skiba notes that in the course of the study, when studying court materials, there were no cases when a convicted person denied release due to illness in connection with self-mutilation [3, p. 235].

These data refer to the Russian Federation, where there are hundreds of times more people released than in Belarus. It is extremely difficult to form any idea of whether such a problem exists with us. Data on self-mutilation is not contained in the court materials on the decision on the issue of release. nine0005

The above facts indicate that the court should not “turn a blind eye” to the issues of causing serious harm to the health of convicts, at the same time, it is necessary to avoid the cruel approach that is reflected in the legislation of the Russian Federation. We believe that the necessary balance may be the legislative wording, in which self-mutilation will be taken into account along with other criteria when deciding on the issue of release, but will not be an unconditional prohibition for release. nine0005

nine0005

It could be assumed that since self-mutilation is an asocial form of behavior of the convict, this issue should be reflected in the analysis of the behavior of the convict. However, since the study of behavior includes a number of other characteristics, it is highly likely that the issue of intentionally harming convicts to their health may be beyond the scope of its study (as it is happening now). In this case, we consider it important to single it out as a separate independent criterion that must be taken into account when making a judgment. nine0005

Conclusion. Summing up what has been said, and answering the question posed at the beginning of the article about whether it is reasonable to introduce the practice of clarifying and taking into account by the court when deciding on the release from punishment of the nature of the occurrence of a serious illness, we conclude that it is advisable to take into account the intentional infliction of harm to the convict to his health. However, such accounting is necessary not as a basis for an unconditional refusal to release, as is enshrined, for example, in the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, but as one of the criteria, along with other medical and penitentiary criteria: the severity of the crime committed, the personality of the convict, the nature of the disease, time served, the behavior of the convict. The committed act of self-mutilation testifies to the convict's improper attitude to his health, however, not all reasons for its commission can directly indicate the degree of correctional impact or the social danger of the convict. This may be a protest, an unsuccessful act of suicide, and harm to health could be caused unconsciously as a result of depression or a mental disorder. Accordingly, the motives for such behavior can also be very diverse, evasion of duties, psychological protection, imitation, and others, which is subject to mandatory assessment by the court when implementing the provisions of Art.

However, such accounting is necessary not as a basis for an unconditional refusal to release, as is enshrined, for example, in the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, but as one of the criteria, along with other medical and penitentiary criteria: the severity of the crime committed, the personality of the convict, the nature of the disease, time served, the behavior of the convict. The committed act of self-mutilation testifies to the convict's improper attitude to his health, however, not all reasons for its commission can directly indicate the degree of correctional impact or the social danger of the convict. This may be a protest, an unsuccessful act of suicide, and harm to health could be caused unconsciously as a result of depression or a mental disorder. Accordingly, the motives for such behavior can also be very diverse, evasion of duties, psychological protection, imitation, and others, which is subject to mandatory assessment by the court when implementing the provisions of Art. nine2 UK.

nine2 UK.

Thus, we consider it necessary to supplement Part 2 of Art. 92 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Belarus with the provision that when exempting from punishment due to illness, it is taken into account, among other things, the deliberate infliction of harm to the convict's health or the consequences that developed after the event. Separate aspects of harming convicts to their health, which should be taken into account when clarifying the issue of convict self-mutilation committed, can be reflected in the draft Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Republic of Belarus “On the practice of exemption from punishment in case of a serious illness”. These issues may include: the presence of mental illness at the time of the self-harm, clarification of the purpose and motives for causing harm to health and the attitude of the convict to the committed act of self-harm, as well as whether this was the only case of harm to these convicts or whether this happened repeatedly. nine0005

nine0005

The proposed version of legislative regulation will make it possible to exclude the established formal approach to the consideration of cases of release from punishment of seriously ill persons, will not allow it to serve as a factor stimulating the spread of the phenomenon of self-harm among convicts, and also, in general, will be able to increase the effectiveness of the application of the rule on release from punishment in case of another severe illness.

Literature:

1. Shabanov, V. B. Organizational and legal problems of counteracting suicidal and non-suicidal self-destructive manifestations of convicts in places of deprivation of liberty / V. B. Shabanov, M. Yu. - 2012. - No. 3. - S. 17–24. nine0005

2. Filchenko, A.P. The attitude of the convict to his health as a criterion for correction: for or against? / A.P. Filchenko // Lawyer. - 2013. - No. 9. - S. 39-43.

3. Skiba A.P. Execution of criminal penalties in relation to sick convicts: theoretical and applied research: thesis . .. doctor. legal Sciences 12.00.08. / A.P. Skiba. - Ryazan, 2013. - 459 p.

.. doctor. legal Sciences 12.00.08. / A.P. Skiba. - Ryazan, 2013. - 459 p.

4. Gubenkova, E.V. Legal and psychological aspects of auto-aggressive behavior of convicts in correctional institutions of Russia / E.V. Gubenkova // Bulletin of the Astrakhan State Technical University. –.2011. — No. 1. — S. 64–69.

5. International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10) [Electronic resource]. — 2014. — Access mode: http://mkb–10.com/. — Date of access: 09/22/2014.

6. Self-mutilation / Forensic medical examination of the state of health [Electronic resource]. — 2014. — Access mode: http://sudebnaja.ru/sudebno–mediczinskaya–ekspertiza–sostoyaniya–zdorovya/349–chlenovreditelstvo.html. — Date of access: 09/22/2014.

7. Tkachevsky, Yu. M. Release from serving a sentence / Yu. M. Tkachevsky. — M.: Yurid. lit., 1970. — 240 p.

8. Kirillova, I.A. Release from serving a sentence due to illness / I.A. Kirillova // Problems of improving the legislation governing the execution of punishment: a collection of scientific papers.