Securely attached child

Is your child securely attached?

© 2008 – 2022 Gwen Dewar, Ph.D., all rights reserved

The Strange Situation procedure: The original test of the infant-parent bond

We hear a lot about “secure attachment relationships.” But what exactly do researchers mean by this term? Psychologist Mary Ainsworth first devised the Strange Situation procedure to assess the quality of an infant’s attachment to his or her mother. This article

- explains the procedure,

- discusses how babies respond,

- reviews why some children are insecurely-attached, and

- explores how early attachments might affect adult outcomes.

It also considers an important question: To what extent has research over-emphasized the role of the mother? Shouldn’t we also be talking about the role of fathers, grandparents, and other caregivers?

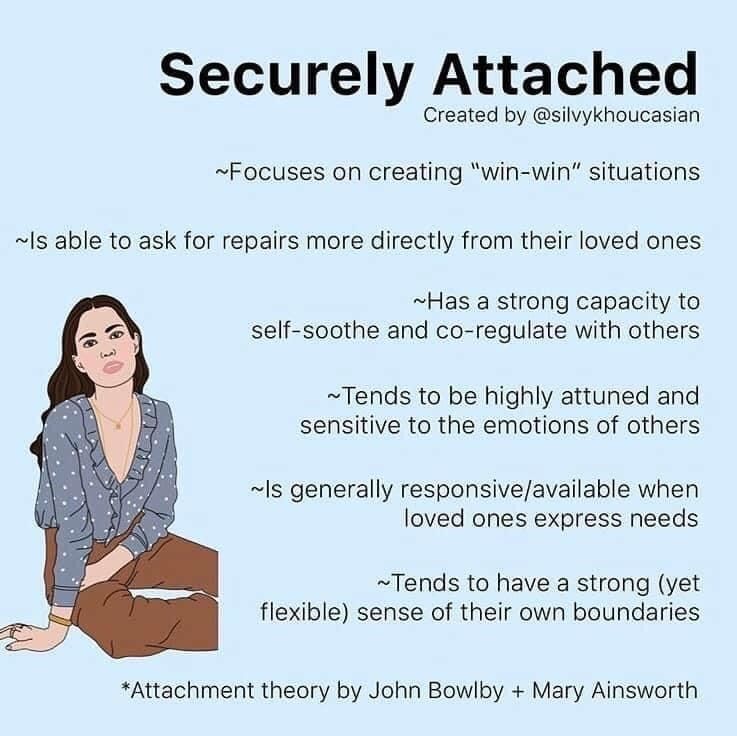

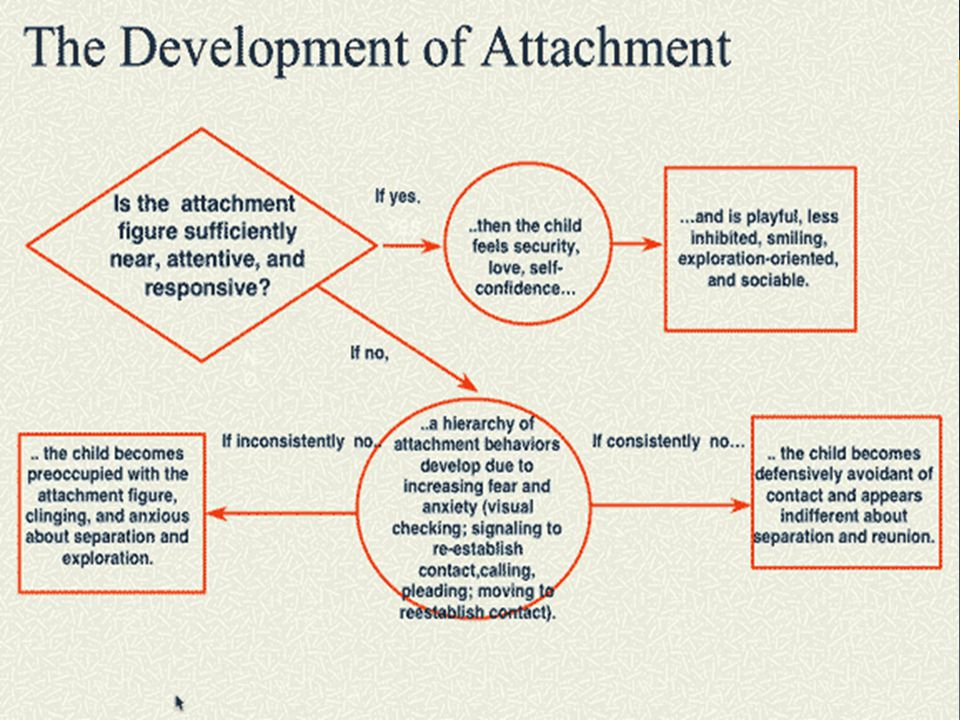

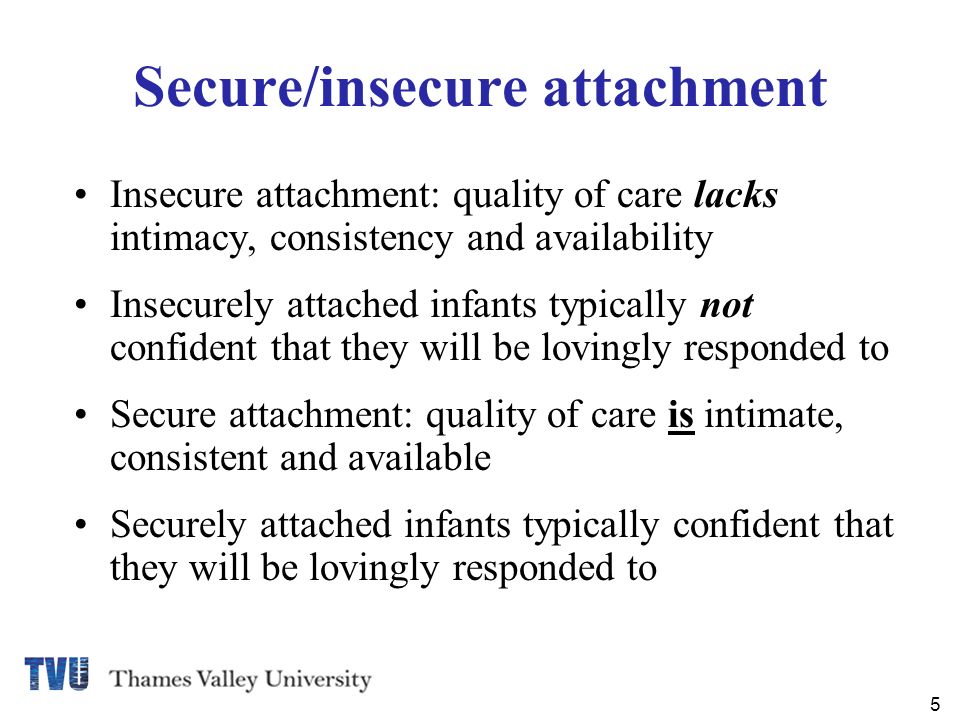

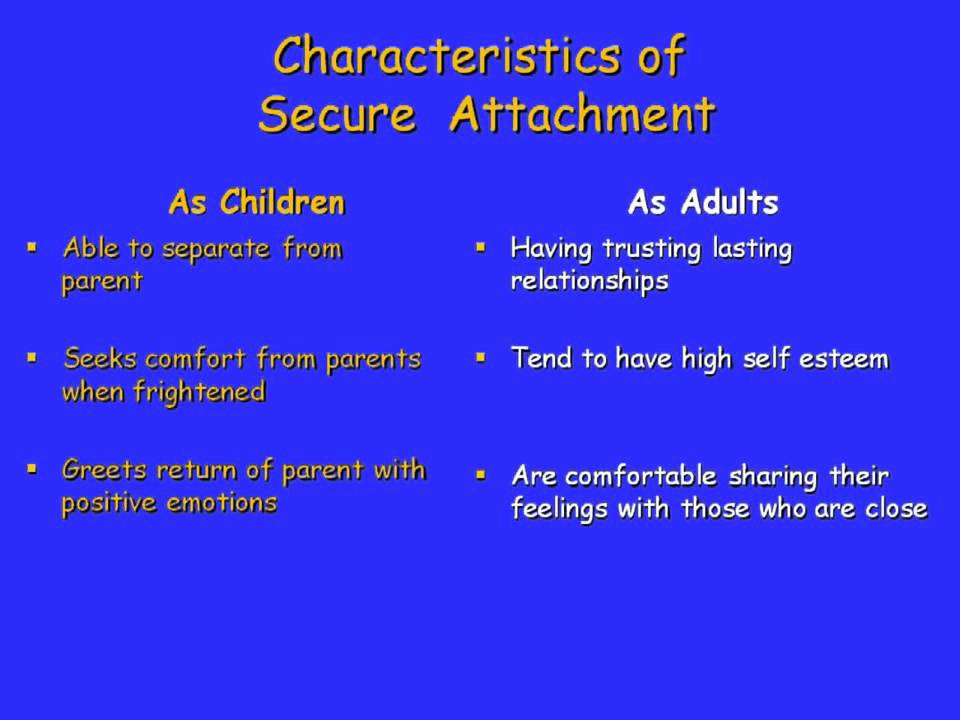

What is a secure attachment?

According to the theories of John Bowlby (1988), children are securely-attached if they are confident of a caregiver’s support. They understand the caregiver to be accessible and responsive, and — as they develop independence during infancy — they come to think of the caregiver as a “secure base.” As long as the caregiver is nearby, securely-attached children feel free to explore, play, and socialize with others.

In addition, securely-attached babies tend to

- keep track of the caregiver during exploration,

- approach or touch the caregiver when anxious or distressed; and

- find comfort in proximity and contact.

And, in the long-term, kids with secure attachments seem to have many advantages – emotional, social, medical, and cognitive.

But how can you know if researchers would classify your own baby as securely attached? How do they actually measure attachment security? The original method, developed by the influential psychologist Mary Ainsworth, is the laboratory procedure called the “Strange Situation” (Ainsworth et al 1978). It tests how babies or young children respond to the temporary absence of their mothers. Here’s how it works.

Here’s how it works.

The Strange Situation

It begins with mother and child being ushered into a room containing toys. Then the child experiences the following steps, with each step taking approximately 3 minutes.

- The mother sits in a chair while the child is allowed to explore the room.

- A friendly woman — previously unknown to the child — enters the room. She talks to the mother, and then gets on the floor and interacts with the child.

- The mother says goodbye and leaves the room. The child is left behind with the friendly stranger.

- The mother returns, and the stranger departs. The mother offers comfort to the child, and encourages the child to play with the toys.

- The mother leaves for a second time. On this occasion, the child is left completely alone. Nobody else is in the room.

- The friendly stranger returns and offers comfort to the child. The stranger tries to distract the child with toys.

- The mother returns for a second reunion. Once again, the stranger leaves, and the mother tries to comfort her child.

How children respond to the Strange Situation

As suggested by its name, the Strange Situation was designed to present children with an unfamiliar, but not overwhelmingly frightening, experience (Ainsworth et al 1978). When a child undergoes the Strange Situation, researchers are interested in two things:

- how much the child explores the room, and

- how the child responds to the return of his or her mother.

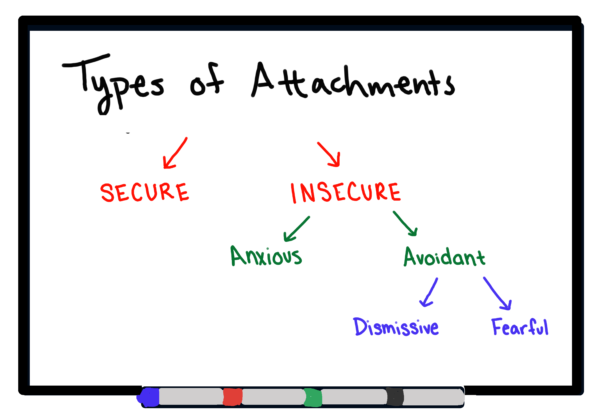

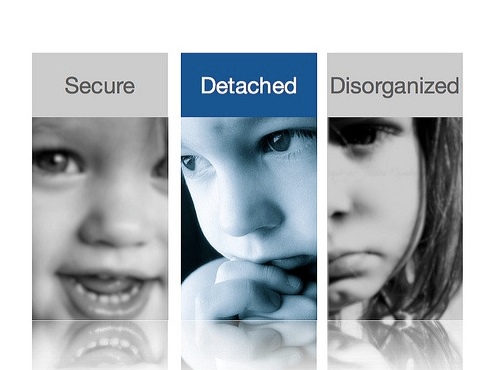

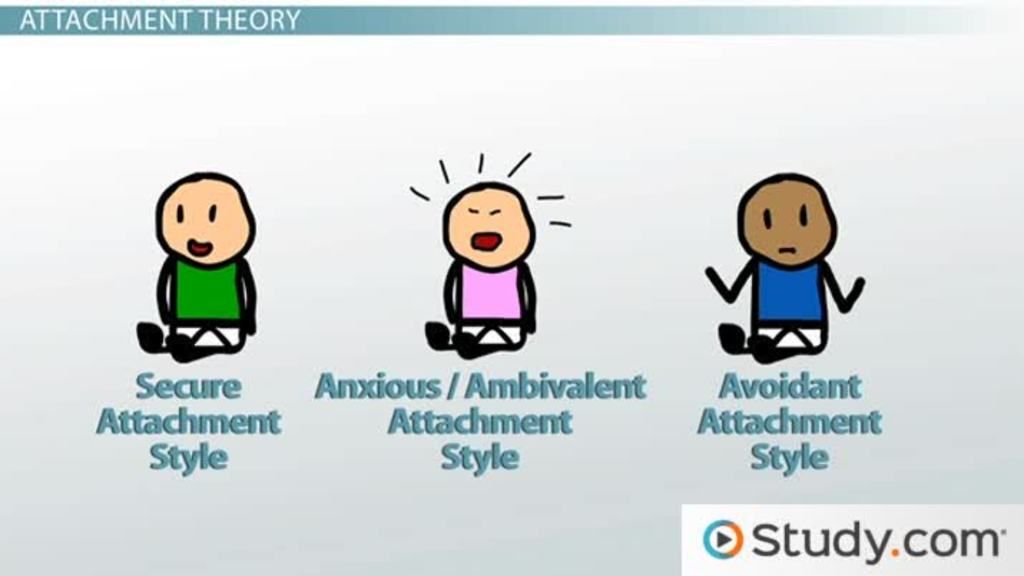

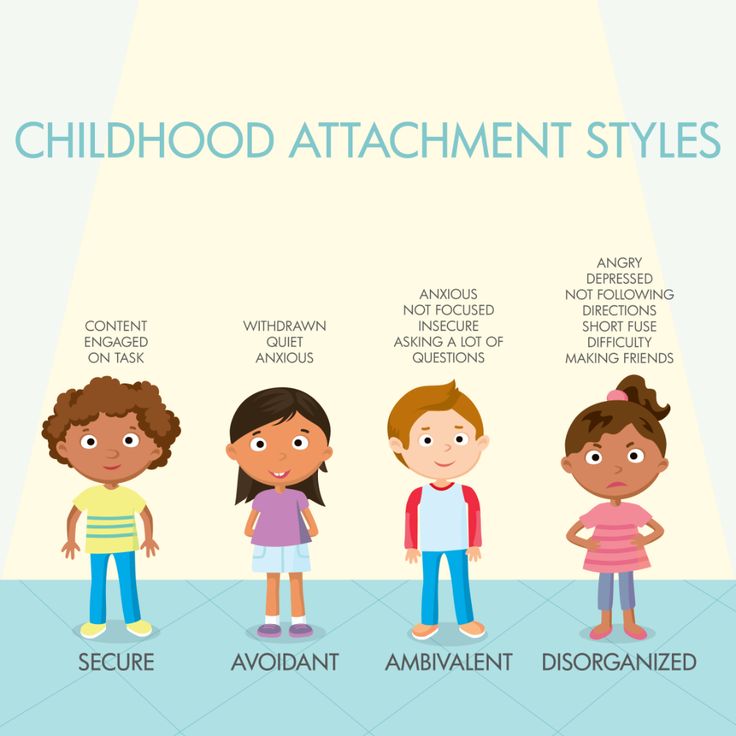

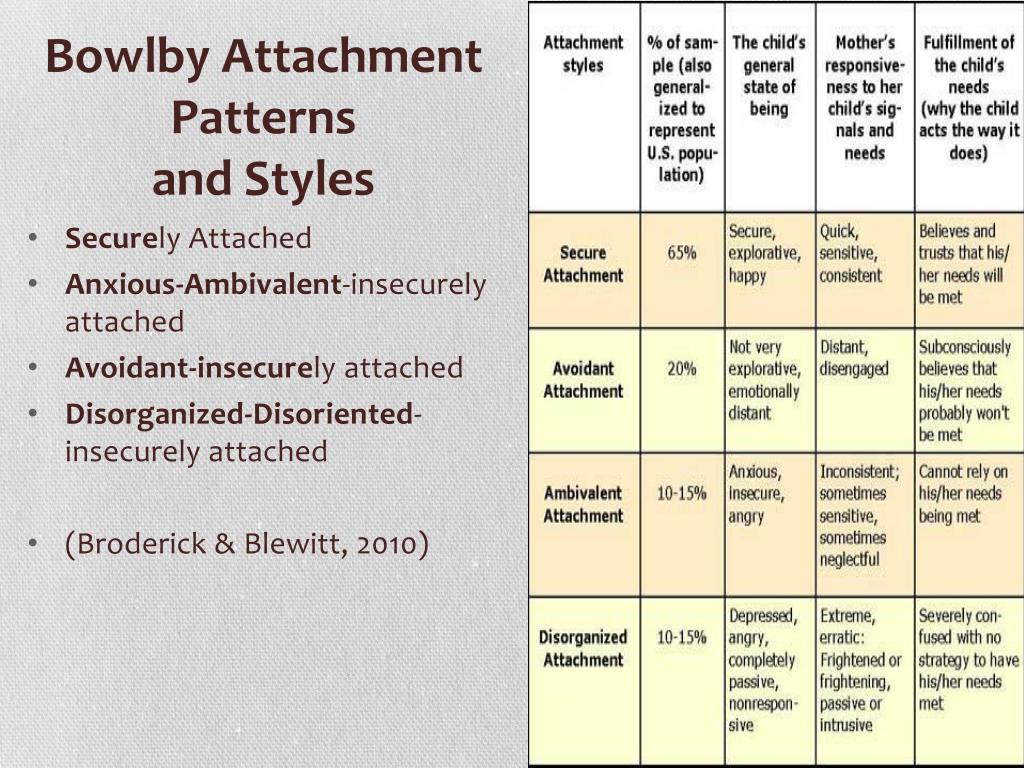

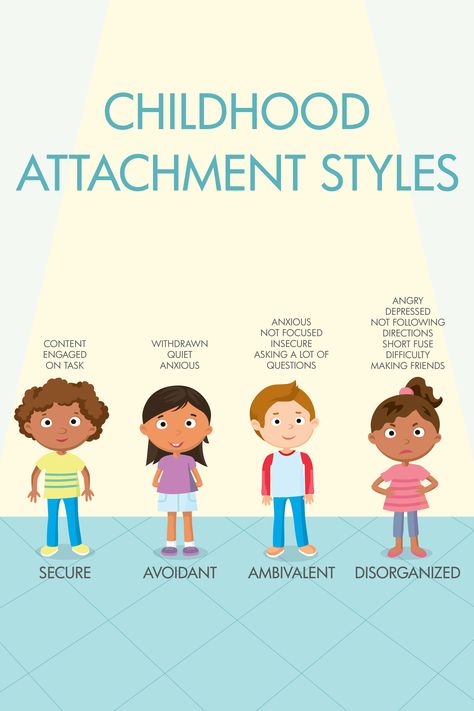

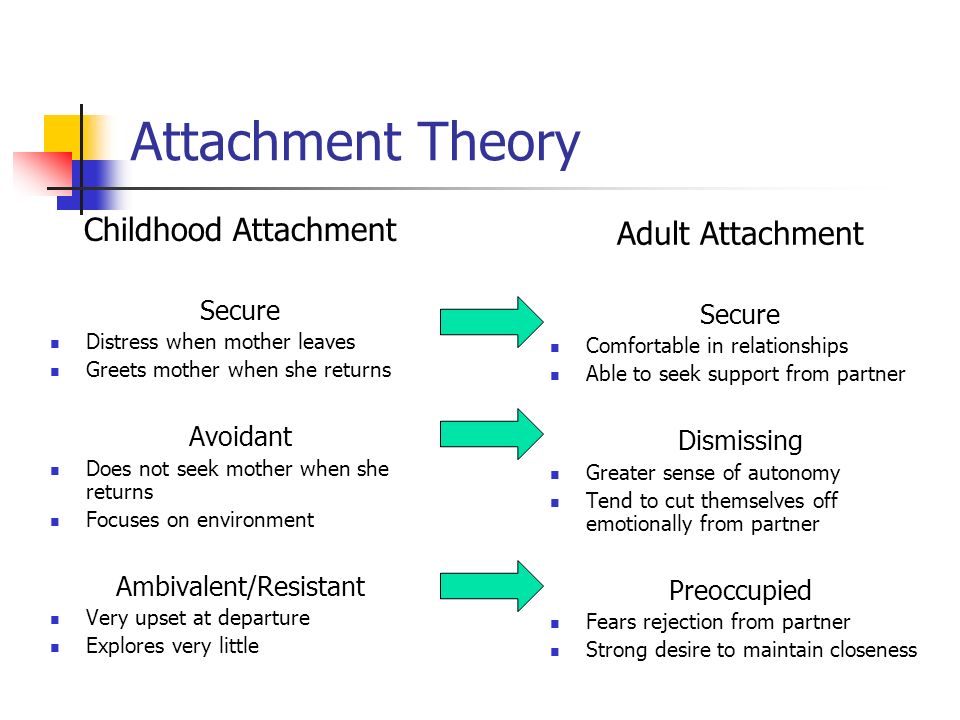

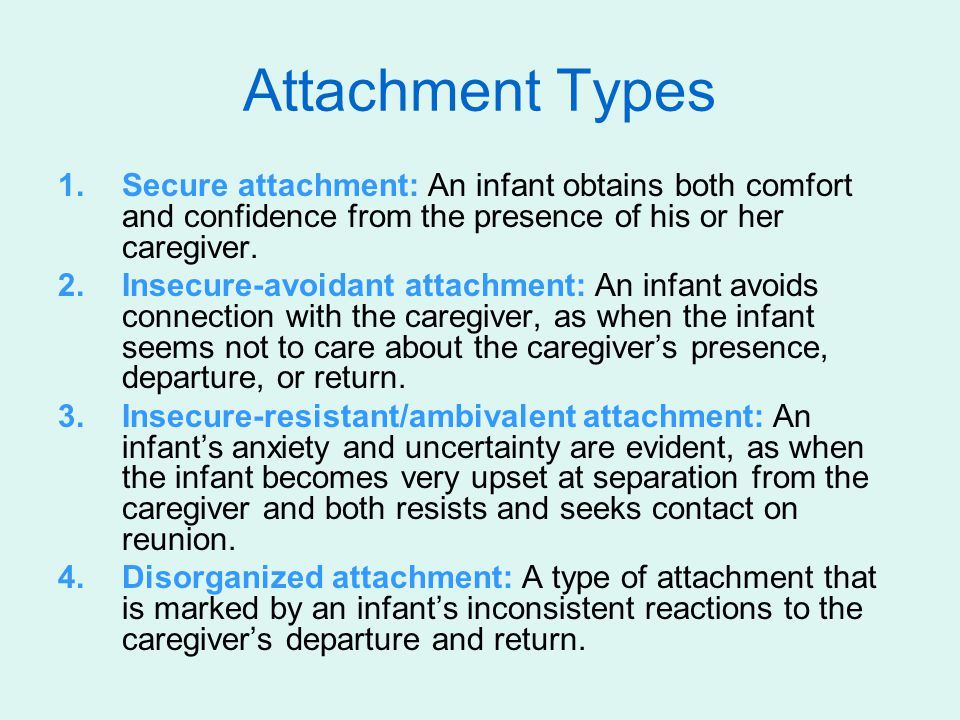

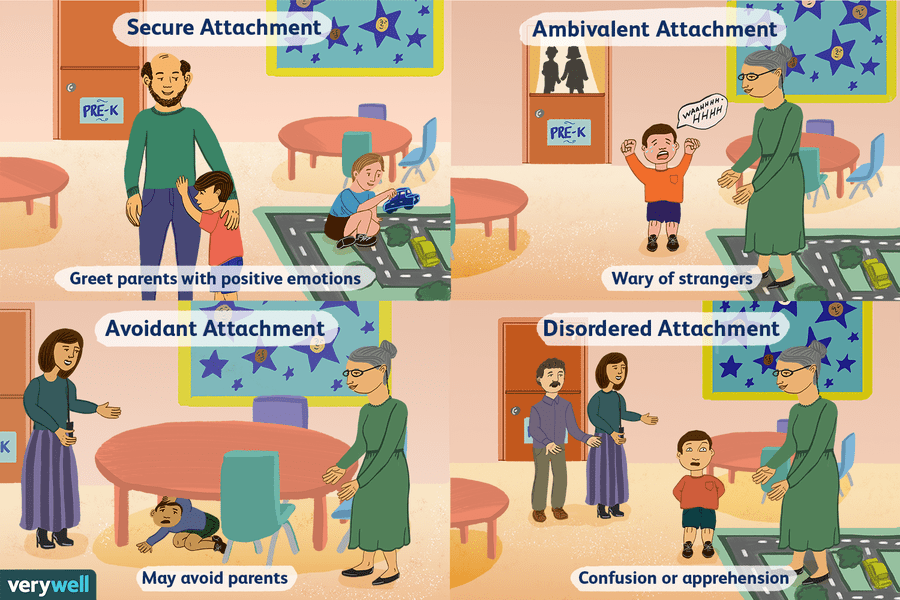

Typically, a child’s response to the Strange Situation follows one of four patterns.

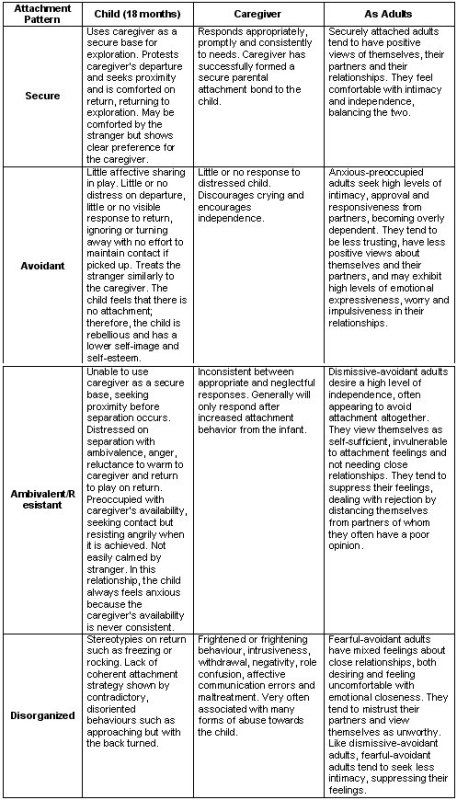

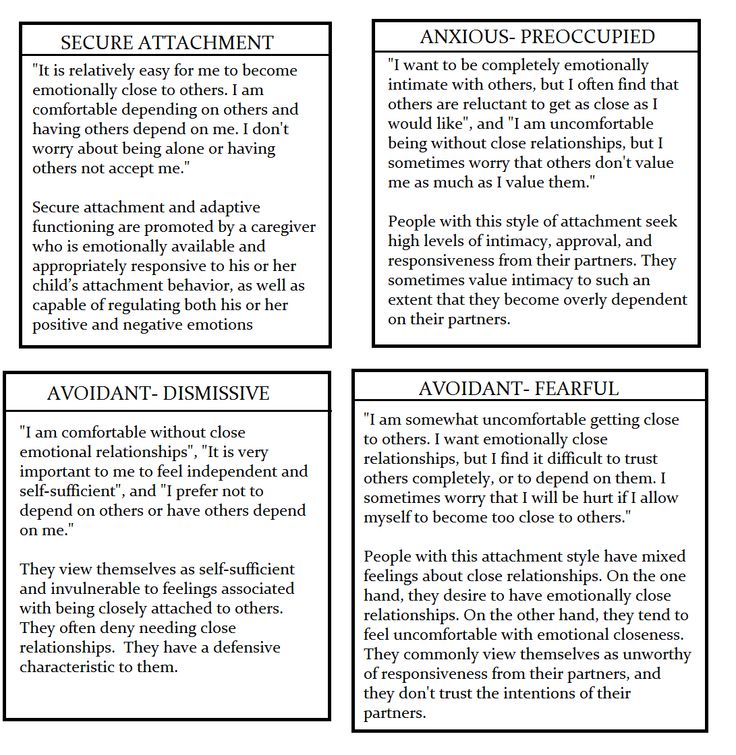

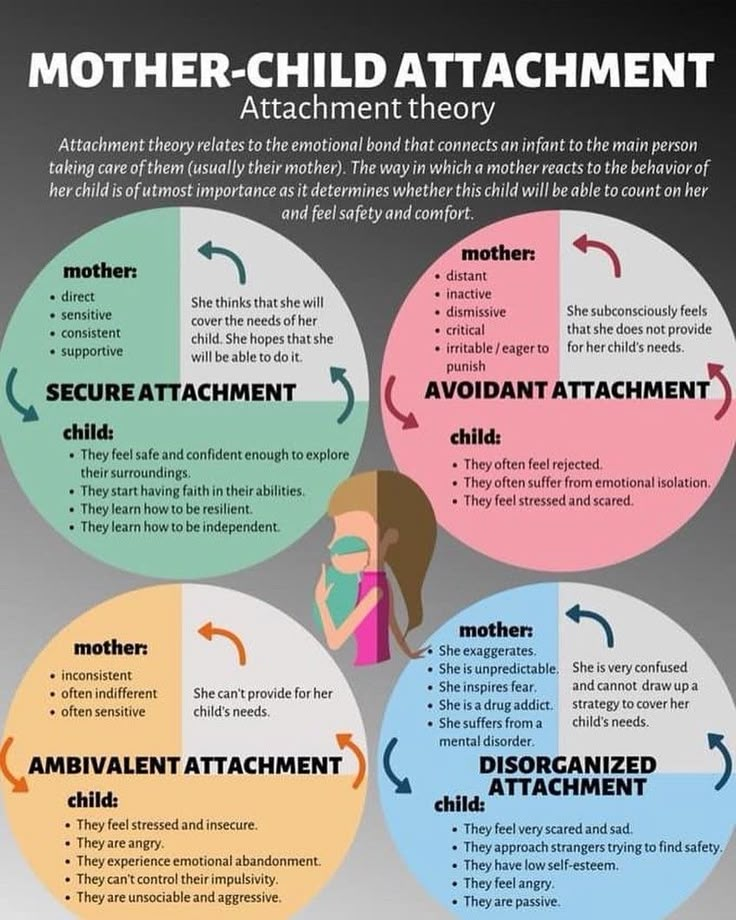

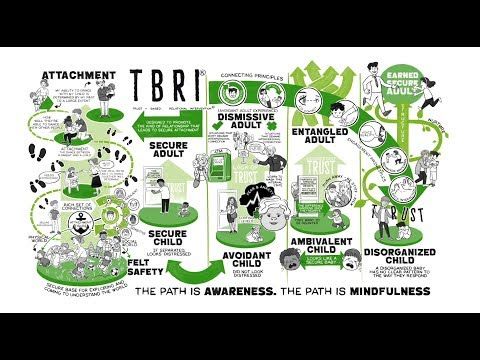

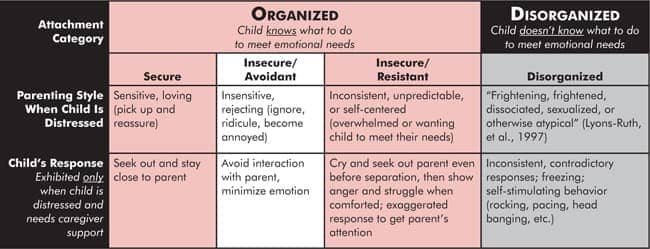

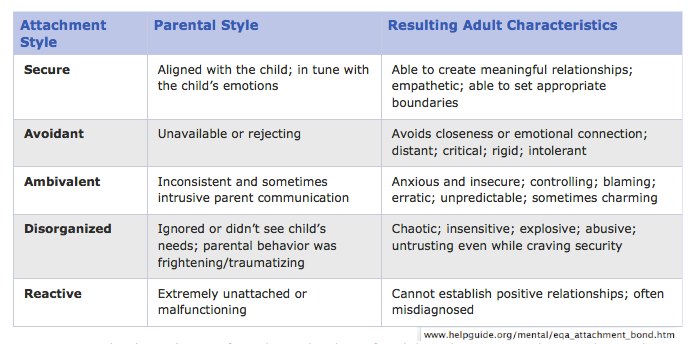

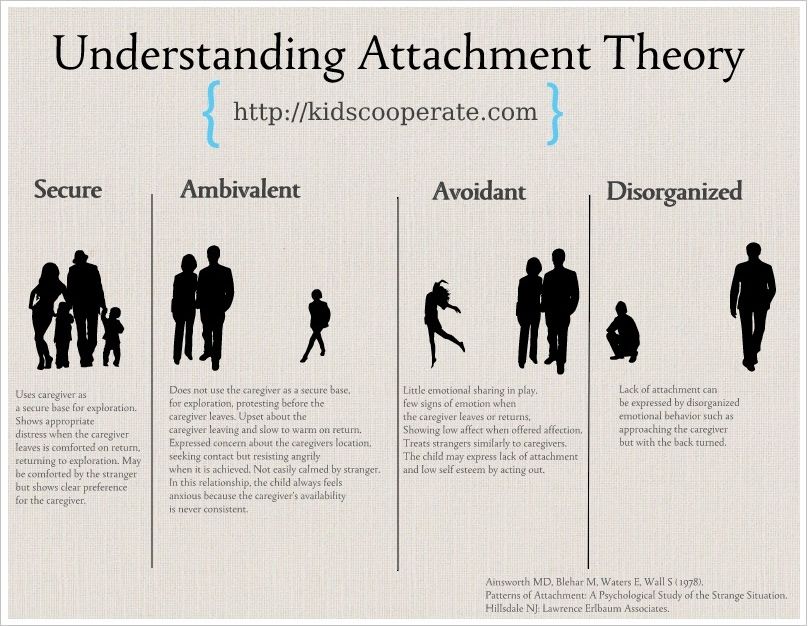

Securely-attached children: Free exploration, and happiness upon the mother’s returnSecurely-attached children explore the room freely when their mothers are present, and they act friendly towards the stranger. After their mothers leave the room, they may become distressed and inhibited – exploring less, and avoiding the stranger. But when they are reunited with their mothers, they quickly recover. If they cry, they approach their mothers and hold them tightly. They are comforted by being held, and, once comforted, they are soon ready to resume their independent exploration of the world. Their mothers are responsive to their needs. As a result, securely-attached children know they can depend on their others when they are under stress (Ainsworth et al 1978).

But when they are reunited with their mothers, they quickly recover. If they cry, they approach their mothers and hold them tightly. They are comforted by being held, and, once comforted, they are soon ready to resume their independent exploration of the world. Their mothers are responsive to their needs. As a result, securely-attached children know they can depend on their others when they are under stress (Ainsworth et al 1978).

Children with an avoidant attachment style don’t explore much, and they don’t show much emotion when their mothers leave. They don’t seem upset about being left alone with the stranger, and, when the mother returns, these children tend to ignore her or avoid eye contact with her (Ainsworth et al 1978).

Resistant-insecure (also called “anxious” or “ambivalent”) children: Little exploration, great separation anxiety, and an ambivalent response to the mother upon her returnLike avoidant children, kids with a resistant or anxious attachment style don’t explore much on their own. But unlike avoidant children, they are wary of strangers, and they may become very distressed when the mother leaves.

But unlike avoidant children, they are wary of strangers, and they may become very distressed when the mother leaves.

When the mother returns, resistant children are ambivalent. Although they want to re-establish close proximity to the mother, they are also resentful—even angry—at the mother for leaving them in the first place. As a result, resistant kids may cling to the mother, but fail to find solace in her attempts to offer comfort. They aren’t easily soothed (Ainsworth et al 1978).

Disorganized-insecure children: Little exploration, and a confused response to the mother.The disorganized child may exhibit a mix of avoidant and resistant behaviors, but the main theme is one of confusion and disruption – hence the label “disorganized” (Main and Solomon 1986). With kids who are avoidantly or resistantly attached, there is a consistent strategy being followed. The avoidant child is keeping up a strategy of disengagement from the caregiver. The resistant child is pretty consistent about signaling his or her negative emotions to the caregiver – expressing inconsolable distress in response to separation, displaying anxiety and anger.

By contrast, children with a disorganized attachment style don’t seem to have settled on a playbook. They want to approach their attachment figure for reassurance, but they feel fear as well, and this leads them to vacillate between approach and retreat, and to display odd behaviors during the Strange Situation – like freezing in place, or moving in repetitive, apparently purposeless ways (Granqvist et al 2017).

Are there other ways to measure attachment security?

Yes. The Strange Situation test was designed for the very young. As kids get older, researchers try other approaches, like the narrative story stem technique, where kids are presented with fictional scenarios (featuring a young protagonist who is experiencing trouble or distress) and asked to describe what happens next (Allen et al 2018).

If a child’s answer depicts secure attachment behavior (where the protagonist seeks out a primary caregiver and receives effective help), this is viewed as evidence that the child is securely-attached. Other responses may suggest an insecure attachment style, such as avoidant (the protagonist refuses to seek help) or resistant (the protagonist seeks help, but the caregiver’s intervention fails to remedy the situation).

Other responses may suggest an insecure attachment style, such as avoidant (the protagonist refuses to seek help) or resistant (the protagonist seeks help, but the caregiver’s intervention fails to remedy the situation).

There are also questionnaires and interviews for diagnosing attachment styles, such as the Attachment Interview for Childhood and Adolescence (AICA), and the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI).

What causes secure attachments? What causes insecure attachments?

Evidence that parenting influences infant attachment style

Numerous studies report the same link: When caregivers are sensitive and responsive, they are more likely to have kids with secure attachments. For instance, in one recent study, mothers who showed high sensitivity to their infants – and who experienced surges of oxytocin while interacting with their babies – were more likely to have children who were securely-attached (Kohlhoff et al 2022).

Does this prove causation? Not by itself. Maybe infants develop secure attachments because they’ve inherited certain genes from their parents — genes that give rise both to the tendency to develop secure attachments, and to the tendency to be sensitive and responsive toward infants.

Maybe infants develop secure attachments because they’ve inherited certain genes from their parents — genes that give rise both to the tendency to develop secure attachments, and to the tendency to be sensitive and responsive toward infants.

But there are compelling arguments against the idea that genetic differences are driving individual differences in attachment security.

For instance, consider adopted children. They haven’t inherited any genes from their parents, yet studies show that adopted infants – like other babies – are more likely to develop secure attachments when their parents are sensitive, responsive, and emotionally available (Verissimo and Salvaterra 2006; Almeida et al 2022).

Moreover, studies show that early intervention — teaching new parents how to increase their sensitivity — improves attachment security (Mountain et al 2017).

And when researchers have tracked genes that we’d expect to correlate with attachment – genes that affect the regulation of dopamine, serotonin, and oxytocin, and influence the development of social relationships – the evidence hasn’t panned out. A few, small studies have reported links with attachment security (e.g., Lakatos et al 2000; Barry et al 2008). But larger studies have failed to replicate the results, and — overall — there is little or no evidence that these genes play a substantial role in determining a child’s attachment style (Leerkes et al 2017; Khan et al 2020).

A few, small studies have reported links with attachment security (e.g., Lakatos et al 2000; Barry et al 2008). But larger studies have failed to replicate the results, and — overall — there is little or no evidence that these genes play a substantial role in determining a child’s attachment style (Leerkes et al 2017; Khan et al 2020).

So we’ve got a strong case for the impact of parenting. But this begs the question. What does it mean to be a sensitive, responsive parent, and what specific behaviors should caregivers be directing at their babies?

Is cuddling the key to infant attachment security?

Ainsworth and others have created coding guidelines for judging whether or not a parent is behaving in “sensitive” and “responsive” ways. Typically, researchers look for evidence that parents are

- noticing a baby’s signals (e.g., fussing or crying),

- accurately interpreting these signals (e.g., the baby is crying because he is hungry), and

- responding promptly and appropriately.

Parents are given scores, and scores correlate with outcomes. For instance, parents who score high on Mary Ainsworth’s Maternal Sensitivity Scale are more likely to have infants who are securely-attached.

Yet the correlations are moderate at best. Not high. And correlations are actually pretty weak among some populations, including Americans of low socioeconomic status. This inspired Susan Woodhouse and her colleagues to question the importance of certain components of sensitivity and responsiveness — like being a good “mind-reader” and responding quickly to an infant’s distress.

Instead, Woodhouse’s team wondered about a very basic, very physical behavior: holding a crying baby, chest-to-chest, until that baby has fully calmed down. The researchers call this “secure base provision”, and they monitored its use in a study of more than 80 mother-offspring pairs – all of them from low-income families. What did Woodhouse’s team discover?

Traditional measures of maternal sensitivity were uncorrelated with attachment security. But “secure base provision” had a big impact, more than doubling a baby’s chances of developing a secure attachment (Woodhouse et al 2020).

But “secure base provision” had a big impact, more than doubling a baby’s chances of developing a secure attachment (Woodhouse et al 2020).

What’s more, the mothers in this study didn’t have to engage in this form of soothing every single time their babies were distressed. Even when moms were observed to provide a secure base less frequently – as little as 50% of the time – babies had a higher probability of developing a secure attachment.

What about predictors of

insecure attachment? Are there specific childhood experiences that put babies at higher risk?Woodhouse’s team looked at these questions, too, and they found that infants were more likely to end up with insecure attachments if their mothers responded to crying in ways that interfered with soothing. This included behavior like speaking in a harsh tone of voice; telling the infant not to cry; and ending the chest-to-chest soothing session before the baby had stopped crying.

Woodhouse and her colleagues also found connections between insecure attachment and maternal behavior that is frightening – like yelling at a crying baby, or suddenly looming over a baby’s face. As Woodhouse explains in Lehigh University press release, such behavior was predictive of insecure attachment, “even if it happened only one time” during the observational period of the study.

As Woodhouse explains in Lehigh University press release, such behavior was predictive of insecure attachment, “even if it happened only one time” during the observational period of the study.

“Similarly,” says Woodhouse, “if the mother did anything really frightening even when the baby wasn’t in distress, like saying ‘bye-bye’ and pretending to leave, throwing the baby in the air to the point they would cry, failure to protect the baby, like walking away from the changing table or not protecting them from an aggressive sibling, or even what we call ‘relentless play’ — insisting on play and getting the baby worked up when it is too much — that also leads to insecurity” (White 2019).

The findings are consistent with previous research, and some believe that frightening parental behavior may be especially linked with the development of disorganized attachment.

Children who are abused or neglected are more likely to suffer from disorganized attachment (Barnett et al 1999). But babies don’t have to be abused or neglected to develop disorganized attachment. In some cases, parents themselves may be anxious or frightened – or dealing with unresolved trauma – so that they inadvertently transmit these fearful emotions to their infants (Main and Hess 1990; Granqvist et al 2017). In other cases, parents might simply be insensitive to what babies find scary (David and Lyons-Ruth 2007; Gedaly and Leerkes 2016).

But babies don’t have to be abused or neglected to develop disorganized attachment. In some cases, parents themselves may be anxious or frightened – or dealing with unresolved trauma – so that they inadvertently transmit these fearful emotions to their infants (Main and Hess 1990; Granqvist et al 2017). In other cases, parents might simply be insensitive to what babies find scary (David and Lyons-Ruth 2007; Gedaly and Leerkes 2016).

If this sounds like you, is there anything you can do about it? Research suggests you can. In studies where parents from at-risk families were coached on how to better read their children’s cues, kids were less likely to develop disorganized attachments (Wright et al 2017).

How does infant temperament affect attachment security?

Some babies are more easily distressed than others, and these individual differences reflect a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Is it possible that temperamentally “difficult” infants might require higher levels of parental responsiveness to develop secure attachments (Seifer at al 1992; van den Boom 1994 Fuertes et al 2006)?

If so, we might expect that some kids with difficult temperaments won’t get the support they need, and this could lead to higher rates of insecure attachment. But what does the evidence tell us? When researchers analyzed the results of more than 100 study samples, they found only a modest correlation between temperament and resistant attachment, and little or no link between temperament and other attachment styles (Groh et al 2017).

But what does the evidence tell us? When researchers analyzed the results of more than 100 study samples, they found only a modest correlation between temperament and resistant attachment, and little or no link between temperament and other attachment styles (Groh et al 2017).

Does stress influence the development of a child’s attachment style?

In theory, stress could cause insecure attachment by interfering with a child’s ability to perceive and interpret parental behavior. Stress could also make it difficult for a child to select the most appropriate, healthy response to being separated from, and reunited with, his or her mother (Waters and Valenzuela 1999). This may help explain why children from families of low socioeconomic status are less likely to develop secure attachments.

But there’s good news, too: Secure attachments have a protective effect – buffering children from the damage caused by toxic stress. Read more about it in my article, “Secure attachment relationships protect kids from toxic stress”.

Do early life attachment relationships have an impact on adult outcomes?

As noted, secure attachments help children cope with toxic stress, so it isn’t surprising that kids with insecure attachments are at higher risk for adult health problems.

For example, in a study tracking more than 160 individuals from infancy, researchers found that people were more likely to report health complaints at the age of 32 years if they had been identified as insecurely attached as babies and toddlers (Puig et al 2013).

There are also links between attachment security and a child’s developing emotional and cognitive skills. For instance, children with secure attachments tend to show a more advanced understanding of emotions (Cooke et al 2016) and they score higher on tests of effortful control (Pallini et al 2018). In studies around the world, kids with insecure attachments are at a moderately increased risk for becoming depressed (Spruit et al 2020).

So it’s easy to imagine that this would lay the groundwork for better social functioning, and research supports the idea that early attachment security foreshadows how adults handle conflict. In another long-term study, researchers found children with insecure attachments at 12 and 18 months were more likely – as young adults –to respond to difficulties with romantic partners by becoming disengaged and suppressing their emotions (Girme et al 2021).

In another long-term study, researchers found children with insecure attachments at 12 and 18 months were more likely – as young adults –to respond to difficulties with romantic partners by becoming disengaged and suppressing their emotions (Girme et al 2021).

Yet it’s important to understand that early caregiving experiences don’t irrevocably define us. Attachment relationships can change over time (Opie et al 2021), and while infant attachments can pave the way for adult attachments, they don’t determine adult outcomes (Fraley end Roisman 2019).

What about cultural differences?

International studies of the Strange Situation

In studies recognizing three attachment classifications (secure, avoidant-insecure, and resistant-insecure), about 21% of American infants have been classified as avoidant-insecure, 65% as secure, and 14% as resistant-insecure. The same distribution is found when researchers pool the results of studies conducted worldwide (van Ijzendoorn and Kroonenberg 1988).

However, there are local variations. For instance, a study conducted in Bielfeld, Germany has reported relatively high rates of avoidantly-attached infants (52%–Grossman et al 1981). And research conducted elsewhere–in Indonesia, Japan, and the kibbutzim of Israel—has reported relatively high rates of resistantly-attached infants (Zevalkink et al 1999; van IJzendoorn and Kroonenberg 1988).

Studies recognizing the fourth classification — disorganized attachment — also indicate the existence of population differences.

The prevalence of disorganized attachment among middle class, white American children is about 12% (Main and Solomon 1990), but it’s much higher among children of low socioeconomic status. Disorganized attachment has also been reported to be relatively common among the Dogon of Mali (~25%, True et al 2001), infants living on the outskirts of Cape Town, South Africa (~26%, Tomlinson et al 2005), children from low income families in Zambia (~29%, Mooya et al 2016), and undernourished children in Chile (Waters and Valenzuela 1999).

Why local populations differ

In some cases, these outcomes may reflect differences in the way infants perceive the Strange Situation, rather than real differences in attachment.

For instance, Israeli children raised in kibbutzim rarely meet strangers. As a result, their high rates of resistant behavior during the Strange Situation test may have had more to do with heightened fear than with the nature of their maternal bonds (Sagi et al 1991).

Similarly, the Japanese results were probably skewed by the facts that Japanese infants are virtually never separated from their mothers (Miyake et al 1995). Nor do Japanese people value independence and independent exploration to the same degree that Westerners do, with the result that otherwise securely-attached babies may explore less (Rothbaum et al 2000).

But in other cases, results of the Strange Situation may reveal genuine cultural differences in the way that children have attached to their mothers. For example, researchers analyzing a variety of attachment studies concluded that German and American infants perceived the Strange Situation in similar ways (Sagi et al 1991). So the relatively high incidence of avoidant-insecure attachments in Germany may reflect real differences in the way that some Germans approach parenting.

So the relatively high incidence of avoidant-insecure attachments in Germany may reflect real differences in the way that some Germans approach parenting.

Has attachment research placed too much emphasis on mothers?

Some evolutionary considerations.

One criticism of the Strange Situation procedure is that it has focused almost exclusively on the mother-infant bond. In part, this may reflect a cultural bias. Many people who study attachment come from industrialized societies where mothers usually bear most of the responsibility for childcare.

But in some families, fathers spend a great deal of time with their children. And in many parts of the world, grandmothers, aunts, uncles, and siblings make substantial — even crucial –contributions to childcare. In fact, among some modern-day foragers, like the Aka and Efe of central Africa, infants spend the much of the day being held by someone other than their mothers (Hewlett 1991; Konner 2005). You can read more about the cooperative nature of hunter-gatherer childcare in my article, “Hunter-gatherers subsidize families…for the benefit of everyone”.

Such evidence has inspired evolutionary anthropologists to “rethink…assumptions about the exclusivity of the mother-infant relationship” (Hrdy 2005). For instance, anthropologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy has argued that non-maternal caregivers may have played an important role in human evolution (Hrdy 2005). When infants have multiple caregivers, their mothers bear less of the cost of child-rearing. Mothers can afford to have more children, and their children can afford to grow up more slowly.

Interestingly, these life-history traits—higher fertility and an extended childhood—distinguish humans from our closest living relatives, the great apes (Smuts et al 1989). And ape mothers—unlike many human mothers—must raise their kids without helpers.

So perhaps “allocare” (non-maternal childcare) gave our ancestors the edge—allowing us to reproduce at faster rates than our nonhuman cousins. If so, it’s foolish to assume that human babies are designed for exclusive attachments to a single, maternal caregiver.

While this point doesn’t detract from the importance of Strange Situation studies, it reminds us that infants can bond with more than one person.

Research confirms that infants form secure attachment relationships with both their mothers and their fathers (Boldt et al 2017). Studies show that toddlers can form secure attachments to their daycare providers (Colonnesi et al 2017). School children can form secure attachments with their teachers (Verschueren 2015). And when they do — when children expand their network of secure relationships — they are more likely to thrive.

More reading

For more readings about the importance of secure, personal relationships, see these articles

- The health benefits of sensitive, responsive parenting

- How toxic stress affects child development

- The science of attachment parenting

- Mind-minded parenting

- Stress in babies: An evidence-based guide to keeping babies calm, happy, and emotionally healthy

- Preschool stress: What causes it, and how we can help kids?

- Student-teacher relationships: The overlooked ingredient for success

References: The Strange Situation

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum.

D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum.

Allen B, Bendixsen B, Babcock Fenerci R, Green J. 2018. Assessing disorganized attachment representations: a systematic psychometric review and meta-analysis of the Manchester Child Attachment Story Task. Attach Hum Dev. 20(6):553-577.

Almeida AS, Giger JC, Mendonça S, Fuertes M, Nunes C. 2022. Emotional Availability in Mother-Child and Father-Child Interactions as Predictors of Child’s Attachment Representations in Adoptive Families. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Apr 13;19(8):4720.

Barnett D, Ganiban J, and Cicchetti D. 1999. Atypical attachment in infancy and early childhood among children at developmental risk. V. Maltreatment, negative expressivity, and the development of type D attachments from 12 to 24 months of age. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 64(3):97-118.

Boldt LJ, Kochanska G, Jonas K. 2017. Infant Attachment Moderates Paths From Early Negativity to Preadolescent Outcomes for Children and Parents. Child Dev. 88(2):584-596.

Infant Attachment Moderates Paths From Early Negativity to Preadolescent Outcomes for Children and Parents. Child Dev. 88(2):584-596.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A Secure Base. New York: Basic Books.

Broussard ER. 1995. Infant attachment in a sample adolescent mothers.Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 25(4):211-9.

Clark CL, St John N, Pasca AM, Hyde SA, Hornbeak K, Abramova M, Feldman H, Parker KJ, Penn AA. 2013. Neonatal CSF oxytocin levels are associated with parent report of infant soothability and sociability. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 38(7):1208-12.

Colonnesi C, van Polanen M, Tavecchio LWC, Fukkink RG. 2017. Mind-Mindedness of Male and Female Caregivers in Childcare and the Relation to Sensitivity and Attachment: An Exploratory Study. Infant Behav Dev. 48(Pt B):134-146.

Cooke JE, Stuart-Parrigon KL, Movahed-Abtahi M, Koehn AJ, Kerns KA. 2016. Children’s emotion understanding and mother-child attachment: A meta-analysis. Emotion. 2016 Dec;16(8):1102-1106.

David D and Lyons-Ruth K. 2007. Differential attachment responses of male and female infants to frightening maternal behavior: tend or befriend versus fight or flight? Infant Ment Health J. 2005; 21(1): 1–18.

2007. Differential attachment responses of male and female infants to frightening maternal behavior: tend or befriend versus fight or flight? Infant Ment Health J. 2005; 21(1): 1–18.

Fraley RC and Roisman GI. 2019. The development of adult attachment styles: four lessons. Current Opin Psychol 25:26-30.

Fuertes M, Santos PL, Beeghly M, and Tronick E. 2006. More than maternal sensitivity shapes attachment: infant coping and temperament. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1094:292-6.

Gedaly LR, Leerkes EM. 2016. The role of sociodemographic risk and maternal behavior in the prediction of infant attachment disorganization. Attach Hum Dev. 18(6):554-569.

Girme YU, Jones RE, Fleck C, Simpson JA, Overall NC. 2021. Infants’ Attachment Insecurity Predicts Attachment-Relevant Emotion Regulation Strategies in Adulthood. Emotion. 2021 Mar; 21(2): 260–272.

Granqvist P, Sroufe LA, Dozier M, Hesse E, Steele M, van Ijzendoorn M, Solomon J, Schuengel D, et al. 2017. Disorganized attachment in infancy: a review of the phenomenon and its implications for clinicians and policy-makers. Attach Hum Dev. 19(6):534-558.

Attach Hum Dev. 19(6):534-558.

Groh AM, Narayan AJ, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Roisman GI, Vaughn BE, Fearon RMP, van IJzendoorn MH. 2017. Attachment and Temperament in the Early Life Course: A Meta-Analytic Review. Child Dev. 88(3):770-795.

Grossman KE, Grossman K, Huber F and Wartner U. 1981. German children’s behavior towards their mothers at 12 months and their fathers at 18 months in Ainsworth’s Strange Situation. International Journal of Behavioral Development 4: 157-181.

Hazen NL, Allen SD, Christopher CH, Umemura T, Jacobvitz DB. 2015. Very extensive nonmaternal care predicts mother-infant attachment disorganization: Convergent evidence from two samples. Dev Psychopathol. 27(3):649-61.

Hewlett BS. 1991. Intimate fathers: The nature and context of Aka pygmy paternal care. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Hrdy SB. 2005. Comes the child before the man: How cooperative breeding and prolonged postweaning dependence shaped human potential. In: Hunter-Gatherer childhoods: Evolutionary, Developmental and Cultural Perspectives. BS Hewlett and ME Lamb (eds). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

In: Hunter-Gatherer childhoods: Evolutionary, Developmental and Cultural Perspectives. BS Hewlett and ME Lamb (eds). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Khan F, Chong JY, Theisen JC, Fraley RC, Young JF, Hankin BL. 2020. Development and change in attachment: A multiwave assessment of attachment and its correlates across childhood and adolescence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 118(6):1188-1206.

Konner M. 2005. Hunter-gatherer infancy and childhood: The !Kung and others. In: Hunter-gatherer childhoods: Evolutionary, developmental and cultural perpectives. BS Hewlett and ME Lamb (eds). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Lakatos K, Toth I, Nemoda Z, Ney K, Sasvari-Szekely M, and Gervai J. 2000. Dopamine D4 receptor (DRD4) gene polymorphism is associated with attachment disorganization in infants. Molecular Psychiatry 5(6): 633-637.

Leerkes EM, Gedaly LR, Zhou N, Calkins S, Henrich VC, Smolen A. 2017. Further evidence of the limited role of candidate genes in relation to infant-mother attachment outcomes. Attach Hum Dev. 2017 Feb;19(1):76-105.

Attach Hum Dev. 2017 Feb;19(1):76-105.

Lyons-Ruth, K.; Jacobvitz, D. Attachment disorganization: unresolved loss, rational violence, and lapses in behavioral and attentional strategies. In: J. Cassidy and P. Shaver (eds), Handbook of attachment: theory, research, and clinical implications. Guilford; New York: 1999. pp. 520–44.

Main M and Solomon J. 1986. Discovery of an insecure-disorganized/ disoriented attachment pattern: Procedures, findings and implications for the classification of behavior. In T. B. Brazelton & M. Yogman (eds), Affective Development in Infancy, 95-124. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Main M and Hesse E. 1990. Parents’ unresolved traumatic experiences are related to infant disorganized attachment status: Is frightened and/or frightening parental behavior the linking mechanism? In: M Greenberg, D Cicchetti, and EM Cummings (eds), Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research and intervention. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, pp. 161–184.

Miyake K, Chen S-J, and Campos J. 1985. Infant temperament and mother’s mode of interaction and attachment in Japan; an interim report. In: I Bretherton and E Waters (eds), Growing points of attachment theory and research. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50, Serial No 209, 276-297.

Mooya H, Sichimba F, and Bakermans-Kranenburg M. 2016. Infant-mother and infant-sibling attachment in Zambia. Attach Hum Dev. 18(6):618-635.

Mountain G, Cahill J, Thorpe H. 2017. Sensitivity and attachment interventions in early childhood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infant Behav Dev. 46:14-32.

Opie JE, McIntosh JE, Esler TB, Duschinsky R, George C, Schore A, Kothe EJ, Tan ES, Greenwood CJ, Olsson CA. 2021. Early childhood attachment stability and change: A meta-analysis. Attach Hum Dev. 23(6): 897–930.

Pallini S, Chirumbolo A, Morelli M, Baiocco R, Laghi F, Eisenberg N. 2018. The relation of attachment security status to effortful self-regulation: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2018 May;144(5):501-531.

Psychol Bull. 2018 May;144(5):501-531.

Puig J, Englund ME, Simpson JA, and Andrew Collins W. 2013. Predicting Adult Physical Illness from Infant Attachment: A Prospective Longitudinal Study. Health Psychol. 32(4): 409–417.

Roisman GI, Booth-Laforce C, Belsky J, Burt KB, Groh AM. 2013. Molecular-genetic correlates of infant attachment: a cautionary tale. Attach Hum Dev. 15(4):384-406.

Rothbaum F, Weisz J, Pott M, Miyake K, Morelli G. 2000. Attachment and culture. Security in the United States and Japan.Am Psychol. 55(10):1093-104.

Sagi A, Lamb ME, Lewkowicz KS, Shoham R, Dvir R, and Estes D. 1985. Security of infant-mother, father, metapelet attachments among kibbutz-reared Israeli children. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1985;50(1-2):257-75

Sagi A, Van IJendoorn, and Koren-Karie. 1991. Primary Appraisal of the Strange Situation: A cross-cultural analysis of preseparation episodes. Developmental Psychology 27(4): 587-596.

Seifer, R., Schiller, M. , Sameroff, A. J., Resnick, S. & Riordan, K. 1996. Attachment, maternal sensitivity, and infant temperament during the first year of life. Develomental Psychology, 32, 12-25.

, Sameroff, A. J., Resnick, S. & Riordan, K. 1996. Attachment, maternal sensitivity, and infant temperament during the first year of life. Develomental Psychology, 32, 12-25.

Smuts BB, Cheney DL, Seyfarth RM, Wrangham RW, and Struhsaker TT. 1987. Primate Societies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Solomon J and George C. 1999 Attachment Disorganization. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Spruit A, Goos L, Weenink N, Rodenburg R, Niemeyer H, Stams GJJM, and Colonnesi C. 2020. The Relation Between Attachment and Depression in Children and Adolescents: A Multilevel Meta-Analysis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 23(1): 54–69.

Suizzo M-A. 2002. French parents’ cultural models and child-rearing beliefs. International journal of behavioral development 26: 297-307.

Tomlinson M, Cooper P, Murray L. 2005. The Mother-Infant Relationship and Infant Attachment in a South African Peri-Urban Settlement. Child Development 76 (5): 1044–1054.

True MM, Pisani L, and Oumar F. 2001.Infant-mother attachment among the Dogon of Mali. Child Development 72(5):1451-66.

2001.Infant-mother attachment among the Dogon of Mali. Child Development 72(5):1451-66.

van den Boom DC. 1994. The influence of temperament and mothering on attachment and exploration: an experimental manipulation of sensitive responsiveness among lower-class mothers with irritable infants. Child Dev. 65(5):1457-77.

Van Ijzendoorn MH and Kroonenberg PM 1988. Cross-cultural patterns of attachment: A meta-analysis of the strange situation. Child Development 59(1): 147-156.

Valentin S. 2005. Commentary: Sleep in German Infants—The “Cult” of Independence 115 (1): 269-271.

Veríssimo M, Salvaterra F. 2006. Maternal secure-base scripts and children’s attachment security in an adopted sample. Attach Hum Dev. 8(3):261-73.

Verschueren K. 2015. Middle Childhood Teacher-Child Relationships: Insights From an Attachment Perspective and Remaining Challenges. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2015(148):77-91.

Vieth G, Englund MM, Simpson JA. 2022. Developmental antecedents of friendship satisfaction in adulthood. Dev Psychol. 2022 Aug 18. doi: 10.1037/dev0001437.

Dev Psychol. 2022 Aug 18. doi: 10.1037/dev0001437.

Waters, E. 1995. The Attachment Q-Set. In E. Waters, B. E. Vaughn, G. Posada, and K. Kondo-Ikemura (eds), Caregiving, cultural, and cognitive perspectives on secure-base behavior and working models. Monograph of the Society for Research in Child Development, 60(2/3, serial No. 244, 247-254.

Waters E and Valenzuela M. 1999. Explaining disorganized attachment: Clues from research on mildly to moderately undernourished children in Chile. In: J. Solomon and C. George (eds), Attachment disorganization. New York: Guildford Press.

Wazana A, Moss E, Jolicoeur-Martineau A, Graffi J, Tsabari G, Lecompte V, Pascuzzo K, Babineau V, Gordon-Green C, Mileva V, Atkinson L, Minde K, Bouvette-Turcot AA, Sassi R, St-André M, Carrey N, Matthews S, Sokolowski M, Lydon J, Gaudreau H, Steiner M, Kennedy JL, Fleming A, Levitan R, Meaney MJ. 2015. The interplay of birth weight, dopamine receptor D4 gene (DRD4), and early maternal care in the prediction of disorganized attachment at 36 months of age. Dev Psychopathol. 27(4 Pt 1):1145-61.

Dev Psychopathol. 27(4 Pt 1):1145-61.

White A. 2019. “Susan Woodhouse: ‘Good Enough’ Parenting is Good Enough” Lehigh University, May 9, 2019. https://www2.lehigh.edu/news/susan-woodhouse-good-enough-parenting-is-good-enough.

Wright B, Hackney L, Hughes E, Barry M, Glaser D, Prior V, Allgar V, Marshall D, Barrow J, Kirby N, Garside M, Kaushal P, Perry A, McMillan D. 2017. Decreasing rates of disorganised attachment in infants and young children, who are at risk of developing, or who already have disorganised attachment. A systematic review and meta-analysis of early parenting interventions. PLoS One. 12(7):e0180858.

Zevalkink J, Riksen-Walraven JM, and Van Lieshout CFM. 1999. Attachment in the Indonesian Caregiving Context Social Development 8(1): 21–40.

Content last modified 8/2022. Portions of the text are derived from an earlier version of this article, written by the same author.

Image credits for “The Strange Situation”:

Title image by digitalskillet / istock

What is a Secure Attachment? And Why Doesn’t "Attachment Parenting" Get You There? — Developmental Science

photo credit: Emily Dorrien

A few months ago, a young friend of mine had a baby. She began a home birth with a midwife, but after several hours of labor, the baby turned to the side and became stuck. The midwife understood that the labor wouldn’t proceed, so she hustled the laboring Amelie into the car and drove the half-mile to the emergency room while Amelie’s husband followed. The birth ended safely, and beautiful, tiny Sylvie emerged with a full head of black hair. The little family of three went home.

She began a home birth with a midwife, but after several hours of labor, the baby turned to the side and became stuck. The midwife understood that the labor wouldn’t proceed, so she hustled the laboring Amelie into the car and drove the half-mile to the emergency room while Amelie’s husband followed. The birth ended safely, and beautiful, tiny Sylvie emerged with a full head of black hair. The little family of three went home.

When the baby was six weeks old, Amelie developed a severe breast infection. She struggled to continue breastfeeding and pumping, but it was extremely painful, and she was taking antibiotics.[1] Finally she gave in to feeding her baby formula, but she felt distraught and guilty. “Make sure you find some other way to bond with your baby,” her pediatrician said, adding to her distress.

Piglet sidled up to Pooh from behind. “Pooh!” he whispered.— A. A. Milne

”Yes, Piglet?”

”Nothing,” said Piglet, taking Pooh’s paw. “I just wanted to be sure of you.

Fortunately, sleep came easily to Sylvie; she slumbered comfortably in a little crib next to Amelie’s side of the bed. Still, at four months, Amelie worried that the bond with her baby wasn’t forming properly and she wanted to remedy the problem by pulling the baby into bed. Baby Sylvie wasn’t having it. When she was next to her mother, she fussed; when Amelie placed her back in the crib, she settled. Again, Amelie worried about their relationship.

“Amelie” is an amalgam of actual friends and clients I have seen in the last month, but all of the experiences are real. And as a developmental psychologist, I feel distressed by this suffering. Because while each of the practices—home birth, breastfeeding, and co-sleeping—has its benefits, none of them is related to a baby’s secure attachment with her caregiver, nor are they predictive of a baby’s mental health and development.

Attachment is a relationship in the service of a baby’s emotion regulation and exploration.— Alan SroufeIt is the deep, abiding confidence a baby has in the availability and responsiveness of the caregiver.

“Attachment is not a set of tricks,” says Alan Sroufe, a developmental psychologist at the Institute for Child Development at the University of Minnesota. He should know. He and his colleagues have studied the attachment relationship for over 40 years.

Why the confusion about a secure attachment?

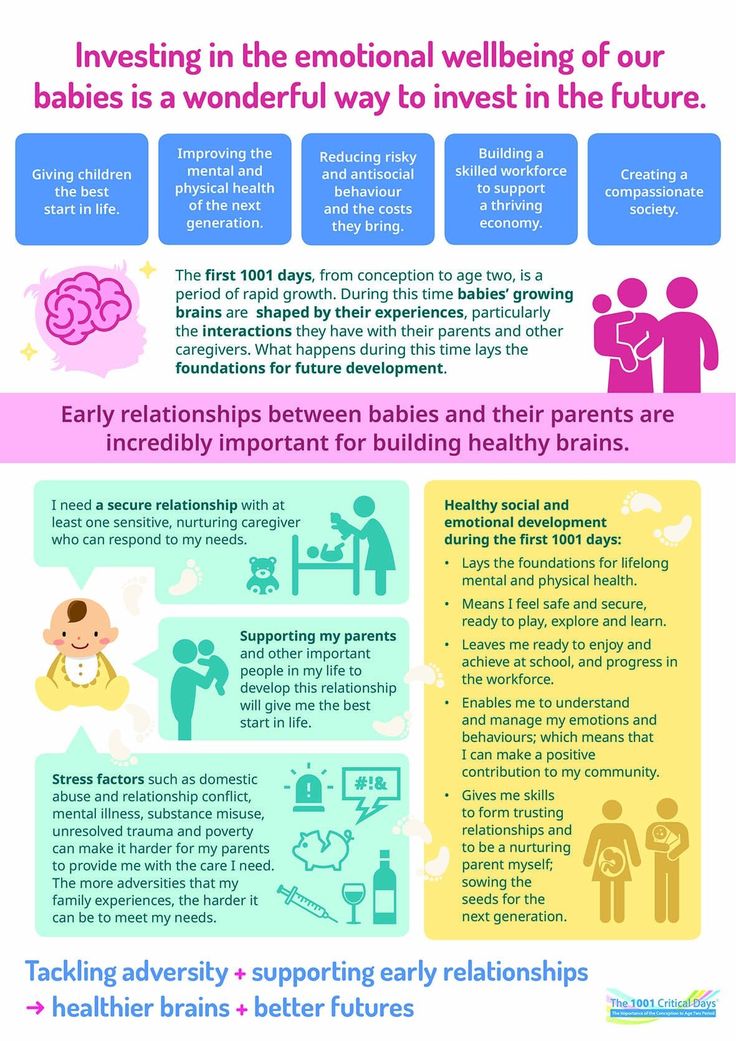

Over the last 80 years, developmental scientists have come to understand that some micro-dynamics that take place between a baby and an adult in a caring relationship have a lifelong effect, in very specific ways, on the person that baby will become.

“Attachment,” Sroufe explains, “is a relationship in the service of a baby’s emotion regulation and exploration. It is the deep, abiding confidence a baby has in the availability and responsiveness of the caregiver.”

A secure attachment has at least three functions:

Provides a sense of safety and security

Regulates emotions, by soothing distress, creating joy, and supporting calm

Offers a secure base from which to explore

In spite of the long scientific history of attachment, psychologists have done a rather poor job of communicating what a secure attachment is and how to create one. In the meantime, the word “attachment” has been co-opted by a well-meaning pediatrician and his wife, William and Martha Sears, along with some of their children and an entire parenting movement. The “attachment parenting” philosophy promotes a lifestyle and a specific set of practices that are not proven to be related to a secure attachment. As a result, the movement has sown confusion (and guilt and stress) around the meaning of the word “attachment.”

In the meantime, the word “attachment” has been co-opted by a well-meaning pediatrician and his wife, William and Martha Sears, along with some of their children and an entire parenting movement. The “attachment parenting” philosophy promotes a lifestyle and a specific set of practices that are not proven to be related to a secure attachment. As a result, the movement has sown confusion (and guilt and stress) around the meaning of the word “attachment.”

The attachment parenting philosophy inspired by the Searses and promoted by an organization called Attachment Parenting International is centered on eight principle concepts, especially breastfeeding, co-sleeping, constant contact like baby-wearing, and emotional responsiveness. The approach is a well-intentioned reaction to earlier, harsher parenting advice, and the tone of the guidance tends to be baby-centered, supportive, and loving. Some of the practices are beneficial for reasons other than attachment. But the advice is often taken literally and to the extreme, as in the case of my “Amelie,” whose labor required hospital intervention and who suffered unduly in the belief that breastfeeding and co-sleeping are necessary for a secure attachment.

Attachment parenting has also been roundly critiqued for promoting a conservative Christian, patriarchal family structure that keeps women at home and tied tightly to their baby’s desires. Additionally, the philosophy seems to have morphed in the public consciousness into a lifestyle that also includes organic food, cloth diapers, rejection of vaccinations, and homeschooling. The Searses have sold millions of books, and they profit from endorsements of products that serve their advice.

“These [attachment parenting principles] are all fine things,” observes Sroufe “but they’re not the essential things. There is no evidence that they are predictive of a secure attachment.”

Sroufe unpacks feeding as an example: A mother could breastfeed, but do it in a mechanical and insensitive way, potentially contributing to an insecure attachment. On the other hand, she could bottle-feed in a sensitive manner, taking cues from the baby and using the interaction as an opportunity to look, talk, and play gently, according to the baby’s communication—all behaviors that are likely to create secure attachment. In other words, it is the quality of the interaction that matters. Now, one might choose breastfeeding for its digestibility or nutrition (though the long-term benefits are still debated), but to imply, as Amelie’s pediatrician did, that bottle-feeding could damage her bond with her baby is simply uninformed.

In other words, it is the quality of the interaction that matters. Now, one might choose breastfeeding for its digestibility or nutrition (though the long-term benefits are still debated), but to imply, as Amelie’s pediatrician did, that bottle-feeding could damage her bond with her baby is simply uninformed.

There is also confusion about what “constant contact” means. Early on, the Searses were influenced by the continuum concept, a “natural” approach to parenting inspired by indigenous practices of wearing or carrying babies much of the time. This, too, might have been taken up in reaction to the advice of the day, which was to treat children in a more businesslike manner. There is no arguing that skin-to-skin contact, close physical contact, holding, and carrying are all good for babies in the first few months of life, as their physiological systems settle and organize. Research also shows that the practice can reduce crying in the first few months. But again, what matters for attachment is the caregiver’s orientation and attunement: Is the caregiver stressed or calm, checked out or engaged, and are they reading a baby’s signals? Some parents misinterpret the prescription for closeness as a demand for constant physical closeness (which in the extreme can stress any parent), even though the Searses do advise parents to strive for a balanced life.

“There’s a difference between a ‘tight’ connection and a secure attachment,” Sroufe explains. “A tight attachment—together all the time—might actually be an anxious attachment.”

And what of emotional responsivity? This, too, has a kernel of truth, yet can be taken too far. It is safe to say that all developmental scientists encourage emotional responsiveness on the part of caregivers: The back-and-forth, or serve-and-return, is crucial to brain development, cognitive and emotional development, the stress regulation system, and just authentic human connection. But in my observation, well-meaning parents can become overly-responsive—or permissive—in the belief that they need to meet every request of the child. While that is appropriate for babies in the first half to one-year year of life (you can’t spoil a baby), toddlers and older children benefit from age-appropriate limits in combination with warmth and love. On the other hand, some parents feel stressed that they cannot give their child enough in the midst of their other responsibilities. Those parents can take some comfort in the finding that even within a secure attachment, parents are only attuned to the baby about 30% of the time. What is important, researchers say, is that the baby develops a generalized trust that their caregiver will respond and meet their needs, or that when mismatches occur, the caregiver will repair them (and babies, themselves, will go a long way toward soliciting that repair). As long as the caregiver returns to the interaction much of the time and rights the baby’s boat, this flow of attunements, mismatches, and repairs offers the optimal amount of connection and stress for a baby to develop both confidence and coping, in balance.

Those parents can take some comfort in the finding that even within a secure attachment, parents are only attuned to the baby about 30% of the time. What is important, researchers say, is that the baby develops a generalized trust that their caregiver will respond and meet their needs, or that when mismatches occur, the caregiver will repair them (and babies, themselves, will go a long way toward soliciting that repair). As long as the caregiver returns to the interaction much of the time and rights the baby’s boat, this flow of attunements, mismatches, and repairs offers the optimal amount of connection and stress for a baby to develop both confidence and coping, in balance.

What is the scientific view of attachment?

The scientific notion of attachment has its roots in the work of an English psychiatrist named John Bowlby who, in the 1930s, began working with children with emotional problems. Most professionals of the day held the Freudian belief that children were mainly motivated by internal drives like hunger, aggression, and sexuality, and not by their environment. However, Bowlby noticed that most of the troubled children in his care were “affectionless” and had experienced disrupted or even absent caregiving. Though his supervisor forbade him from even talking to a mother of a child (!), he insisted that family experiences were important, and in 1944 he wrote his first account of his observations based on 44 boys in his care. (Around the same time in America, psychologist Harry Harlow was coming to the same conclusion in his fascinating and heart-rending studies of baby monkeys, where he observed that babies sought comfort, and not just food, from their mothers.)

However, Bowlby noticed that most of the troubled children in his care were “affectionless” and had experienced disrupted or even absent caregiving. Though his supervisor forbade him from even talking to a mother of a child (!), he insisted that family experiences were important, and in 1944 he wrote his first account of his observations based on 44 boys in his care. (Around the same time in America, psychologist Harry Harlow was coming to the same conclusion in his fascinating and heart-rending studies of baby monkeys, where he observed that babies sought comfort, and not just food, from their mothers.)

Bowlby went on to study and treat other children who were separated from their parents: those who were hospitalized or homeless. He came to believe that the primary caregiver (he focused mainly on mothers) served as a kind of “psychic organizer” to the child, and that a child needs this influence, especially at certain times, in order to develop successfully. To grow up mentally healthy, then, “the infant and young child should experience a warm, intimate, and continuous relationship with this mother (or permanent mother substitute) in which both find satisfaction and enjoyment. ”

”

But the attachment figure doesn’t have to be the mother or even a parent. According to Bowlby, babies form a “small hierarchy of attachments.” This makes sense from an evolutionary view: The number has to be small since attachment organizes emotions and behavior in the baby, and to have too many attachments would be confusing; yet having multiples provides the safety of backups. And it’s a hierarchy because when the baby is in need of safety, he or she doesn’t have time to analyze the pros or cons of a particular person and must automatically turn to the person already determined to be a reliable comfort. Research shows that children who have a secure attachment with at least one adult experience benefits. Babies can form attachments with older siblings, fathers, grandparents, other relatives, a special adult outside the family, and even babysitters and daycare providers. However, there will still be a hierarchy, and under normal circumstances, a parent is usually at the top.

View fullsize

photo credit: K. Merchant

View fullsize

photo credit: K. Merchant

View fullsize

photo credit: D. Divecha

View fullsize

photo credit: D. Divecha

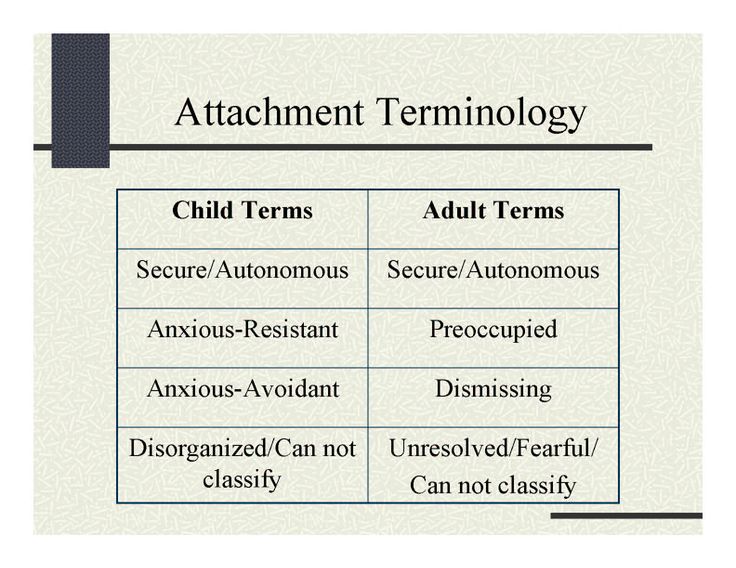

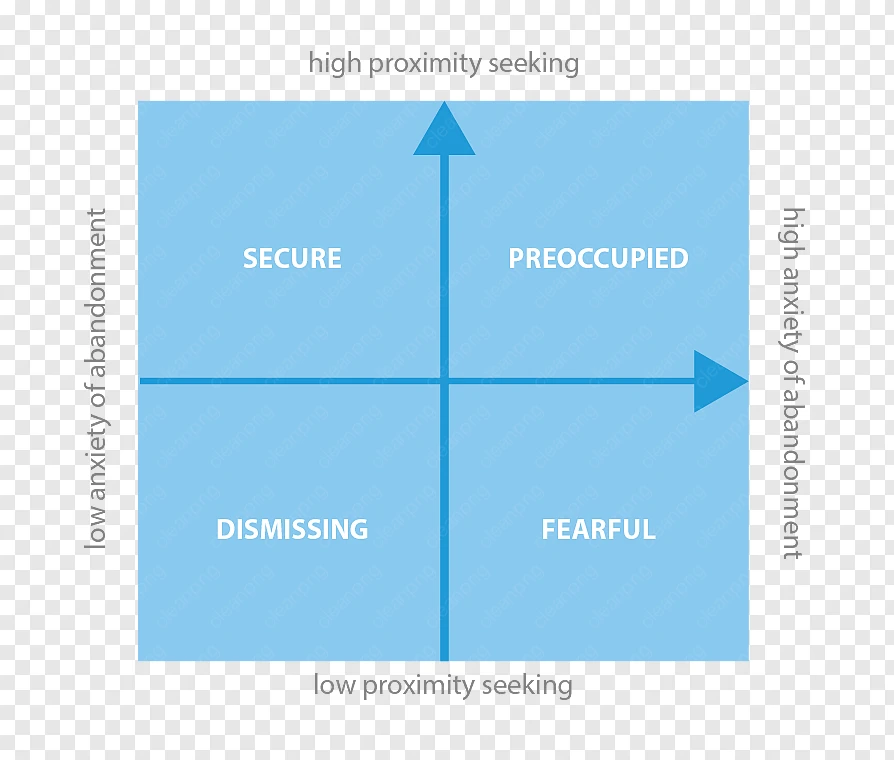

In the 1950s, Mary Ainsworth joined Bowlby in England, and a decade later back in the U.S. began to diagnose different kinds of relationship patterns between children and their mothers in the second year of life.[2] She did this by watching how babies reacted in a sequence of situations: when the baby and mother were together, when they were separated, when the baby was with a stranger, and when baby was reunited with the caregiver after the separation. Ainsworth and colleagues identified the first three of the following patterns, and Mary Main and colleagues identified the fourth:

Ainsworth and colleagues identified the first three of the following patterns, and Mary Main and colleagues identified the fourth:

When babies have a secure attachment, they play and explore freely from the “secure base” of their mother’s presence. When the mother leaves, the baby can become distressed, especially when a stranger is around. When the mother returns, the baby expresses her joy, sometimes from a distance and sometimes reaching to be picked up and held (babies vary, depending on their personality and temperament, even within a secure attachment). Then the baby settles quickly and returns to playing.

The mothers who fall into this pattern are responsive, warm, loving, and emotionally available, and as a result their babies grow to be confident in their mothers’ ability to handle feelings. The babies feel free to express their positive and negative feelings openly and don’t develop defenses against the unpleasant ones.

Babies in insecure-avoidant attachments seem indifferent to the mother, act unstressed when she leaves, and exhibit the same behaviors with a stranger. When the mother returns after a separation, the baby might avoid her, or might “fail to cling” when picked up.

The mothers in insecure-avoidant attachments often seem angry in general and angry, specifically, at their babies. They can be intolerant, sometimes punishing, of distress, and often attribute wrong motivations to the baby, e.g., “He’s just crying to spite me.” One study showed that the insecurely-attached babies are just as physiologically upset (increased heart rates, etc.) as securely attached babies when parents leave but have learned to suppress their emotions in order to stay close to the parent without risking rejection. In other words, the babies “deactivate” their normal attachment system and stop looking to their mothers for help.

As toddlers, insecure-avoidant children don’t pay much attention to their mothers or their own feelings, and their explorations of the physical world are rigid and self-reliant. By preschool, these children tend to be more hostile, aggressive, and have more negative interactions overall. Avoidance and emotional distance become a way of dealing with the world, and instead of problem-solving, they are more likely to sulk or withdraw.

By preschool, these children tend to be more hostile, aggressive, and have more negative interactions overall. Avoidance and emotional distance become a way of dealing with the world, and instead of problem-solving, they are more likely to sulk or withdraw.

Babies with an insecure-ambivalent/resistant attachment are clingy with their mother and don’t explore or play in her presence. They are distressed when the mother leaves, and when she returns, they vacillate between clinging and angry resistance. For example, they may struggle, hit, or push back when the mother picks them up.

These babies are not easily comforted. They seem to want the close relationship, but the mother’s inconsistency and insensitivity undermine the baby’s confidence in her responses. This pattern also undermines the child’s autonomy, because the baby stays focused on the mother’s behavior and changing moods to the exclusion of nearly everything else. In insecure-ambivalent babies, separation anxiety tends to last long after secure babies have mastered it. Longitudinal studies show that these children often become inhibited, withdrawn, and unassertive, and they have poor interpersonal skills.

In insecure-ambivalent babies, separation anxiety tends to last long after secure babies have mastered it. Longitudinal studies show that these children often become inhibited, withdrawn, and unassertive, and they have poor interpersonal skills.

The last pattern of insecure attachment—which is the most disturbing and destructive—is disorganized attachment, and it was described by Ainsworth’s doctoral student, Mary Main. This pattern can occur in families where there is abuse or maltreatment; the mother, who is supposed to be a source of support, is also the person who frightens the child. Such mothers may be directly maltreating the child, or they might have their own histories of unresolved trauma. Main and her colleague write, “[T]he infant is presented with an irresolvable paradox wherein the haven of safety is at once the source of alarm.”

This pattern can also result when the mother has a mental illness, substance addiction, or multiple risk factors like poverty, substance abuse and a history of being mistreated. Babies of mothers like this can be flooded with anxiety; alternatively, they can be “checked out” or dissociated, showing a flat, expressionless affect or odd, frozen postures, even when held by the mother. Later these children tend to become controlling and aggressive, and dissociation remains a preferred defense mechanism.[3]

Babies of mothers like this can be flooded with anxiety; alternatively, they can be “checked out” or dissociated, showing a flat, expressionless affect or odd, frozen postures, even when held by the mother. Later these children tend to become controlling and aggressive, and dissociation remains a preferred defense mechanism.[3]

The emotional quality of our earliest attachment experience is perhaps the single most important influence on human development.— Alan Sroufe and Dan Siegel

How important is attachment?

“Nothing is more important than the attachment relationship,” says Alan Sroufe, who, together with colleagues, performed a series of landmark studies to discover the long-term impact of a secure attachment. Over a 35-year period, the Minnesota Longitudinal Study of Risk and Adaption (MLSRA) revealed that the quality of the early attachment reverberated well into later childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, even when temperament and social class were accounted for.

One of the most important—and, to some ways of thinking, paradoxical—findings was that a secure attachment early in life led to greater independence later, whereas an insecure attachment led to a child being more dependent later in life. This conclusion runs counter to the conventional wisdom held by some people I’ve observed who are especially eager to make the baby as independent and self-sufficient as possible right from the start. But there is no pushing independence, Sroufe found. It blooms naturally out of a secure attachment.

photo credit: K. Merchant

photo credit: K. Merchant

In school, securely attached children were more well-liked and treated better, by both their peers and their teachers. In one study, teachers who had no knowledge of a child’s attachment history were shown to treat securely attached children with more warmth and respect, set more age-appropriate standards, and have higher expectations. In contrast, teachers were more controlling, had lower expectations, got angry more often, and showed less nurturing toward the children with difficult attachments—and who, sadly, had a greater need than the securely attached kids for kindness from adults.

In contrast, teachers were more controlling, had lower expectations, got angry more often, and showed less nurturing toward the children with difficult attachments—and who, sadly, had a greater need than the securely attached kids for kindness from adults.

The MSLRA studies showed that children with a secure attachment history were more likely to develop:[4]

A greater sense of self-agency

Better emotional regulation

Higher self-esteem

Better coping under stress

More positive engagement in the preschool peer group

Closer friendships in middle childhood

Better coordination of friendships and social groups in adolescence

More trusting, non-hostile romantic relationships in adulthood

Greater social competence

More leadership qualities

Happier and better relationships with parents and siblings

Greater trust in life

A large body of additional research suggests that a child’s early attachment affects the quality of their adult relationships, and a recent longitudinal study of 81 men showed that those who grew up in warm, secure families were more likely to have secure attachments with romantic partners well into their 70s and 80s. A parent’s history of childhood attachment can also affect their ability to parent their own child, creating a cross-generational transmission of attachment styles.

A parent’s history of childhood attachment can also affect their ability to parent their own child, creating a cross-generational transmission of attachment styles.

But early childhood attachment with a parent is not destiny: It depends on what else comes along. For example, a secure preschool child can shift to having an insecure attachment later if there is a severe disruption in the caregiving system—a divorce or death of a parent, for example. But the effect is mediated by how stressed and available the primary attachment figure is. In other words, it’s not what happens, but how it happens that matters. Children who were previously secure, though, have a tendency to rebound more easily.

Sroufe writes in several articles that an insecure attachment is not fate, either; it can be repaired in a subsequent relationship. For example, good-quality childcare that offers emotional support and stress reduction can mitigate a rocky start at home. A later healthy romantic relationship can offset the effects of a difficult childhood. And good therapy can help, too, since some of the therapeutic process mimics the attachment process. Bowlby viewed development as a series of pathways, constrained by paths previously taken but where change is always possible.

And good therapy can help, too, since some of the therapeutic process mimics the attachment process. Bowlby viewed development as a series of pathways, constrained by paths previously taken but where change is always possible.

Without conscious intervention, though, attachment styles do tend to get passed through the generations, and Bowlby observed that becoming a parent particularly activates a parent’s childhood attachment style. One study looked at attachment styles over three generations and found that the mother’s attachment style when she was pregnant predicted her baby’s attachment style at one year of age for about 70% of cases.

What about parents who might not have gotten a good start in life and want to change their attachment style? There’s good news. Research on adult attachment shows that it is not the actual childhood experiences with attachment that matter but rather how well the adult understands what happened to them, whether they’ve learned some new ways of relating, and how well they’ve integrated their experience into the present. In other words, do they have a coherent and realistic story (including both good and bad) of where they’ve been and where they are now?

In other words, do they have a coherent and realistic story (including both good and bad) of where they’ve been and where they are now?

Support matters, too. In one of Sroufe’s studies, half the mothers were teenagers, which is usually a stressful situation. Sroufe found that the teenagers with good social support were able to form secure attachments with their babies, but if they didn’t have support, they were unlikely to form a secure attachment.

How to parent for a secure attachment and how to know if it’s working.

“The baby needs to know that they’re massively important,” says Sroufe. “A caregiver should be involved, attentive, sensitive, and responsive.”

“The baby will tell you what to do,” Sroufe explains. “They have a limited way of expressing their needs, so they’re not that difficult to read: If they’re fussing, they need something. If their arms are out, they want to be picked up. And if you misread them, they will keep on signaling until you get it right. ” He gives the example of bottle-feeding a baby: “The baby might want a break, and she looks around. What does the baby want? To look around! If the parent misreads and forces the bottle back, the baby will insist, maybe snap her head away, or pull away harder.”

” He gives the example of bottle-feeding a baby: “The baby might want a break, and she looks around. What does the baby want? To look around! If the parent misreads and forces the bottle back, the baby will insist, maybe snap her head away, or pull away harder.”

“How can I know if my baby is securely attached?” a client asked me about her six-month old. Clearly observable attachment doesn’t emerge until around nine months, but here are some clues that a secure attachment is underway:

0-3 months:

The baby’s physiology is just settling as the baby cycles quickly among feeding, sleeping, and alert wakefulness. Meeting the baby’s needs at different points in the cycle helps establish stability.

At this point, the baby has no clear preference for one person over another.

In her quiet, alert state, the baby is interested in the faces and voices around her.

4-8 months:

Attempts to soothe the baby are usually effective at calming her down.

(Caveat: An inability to soothe might not be predictive of insecurity but rather point to one of a host of other possible issues.)

(Caveat: An inability to soothe might not be predictive of insecurity but rather point to one of a host of other possible issues.)The primary caregiver has positive interactions with the baby where the back-and-forth is pleasant.

The baby has calm periods where she is interested in the world around her, and she explores and experiments to the extent she is physically able to—looking, grasping, reaching, babbling, beginning crawling, exploring objects with her mouth, hands, etc.

Infants begin to discriminate between people and start to show preferences. They direct most of their emotions (smiles, cries) toward the caregiver but are still interested in strangers.

They are very interested in the people they see often, especially siblings.

9 months:

The baby shows a clear preference for a primary caregiver.

The baby shows wariness toward strangers, though the degree varies with temperament.

The baby is easily upset when separated from her primary caregiver, though that, too, varies with temperament.

The baby is easily soothed after a separation and can resume her exploration or play.

9 months – 3 years:

The child shows a clear emotional bond with a primary person.

The child stays in close proximity to that person but forms close relationships with other people who are around a lot, too, e.g., babysitter, siblings.

Beyond this age, the attachment relationship becomes more elaborated. With language and memory, the rhythms of attachment and separation become more negotiated, talked about, and planned, and there is more of a back-and-forth between parent and child. By toddlerhood and beyond, an authoritative parenting style deftly blends secure attachment with age-appropriate limits and supports. A sensitive parent allows the changing attachment to grow and stretch with a child’s growing skills, yet continues to be emotionally attuned to the child and to protect their safety.

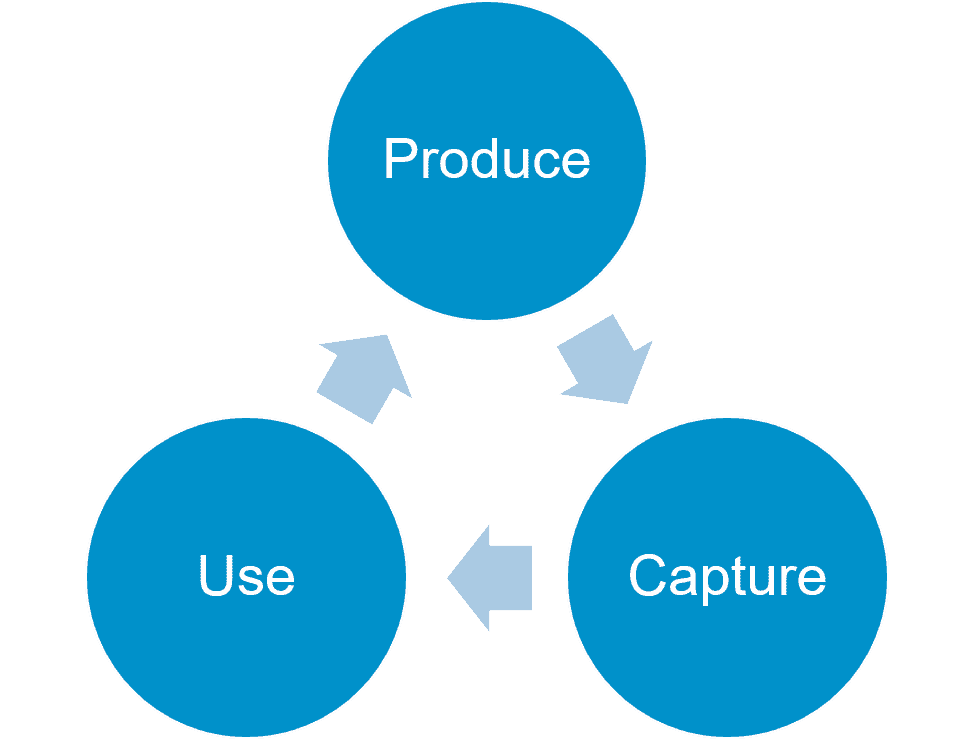

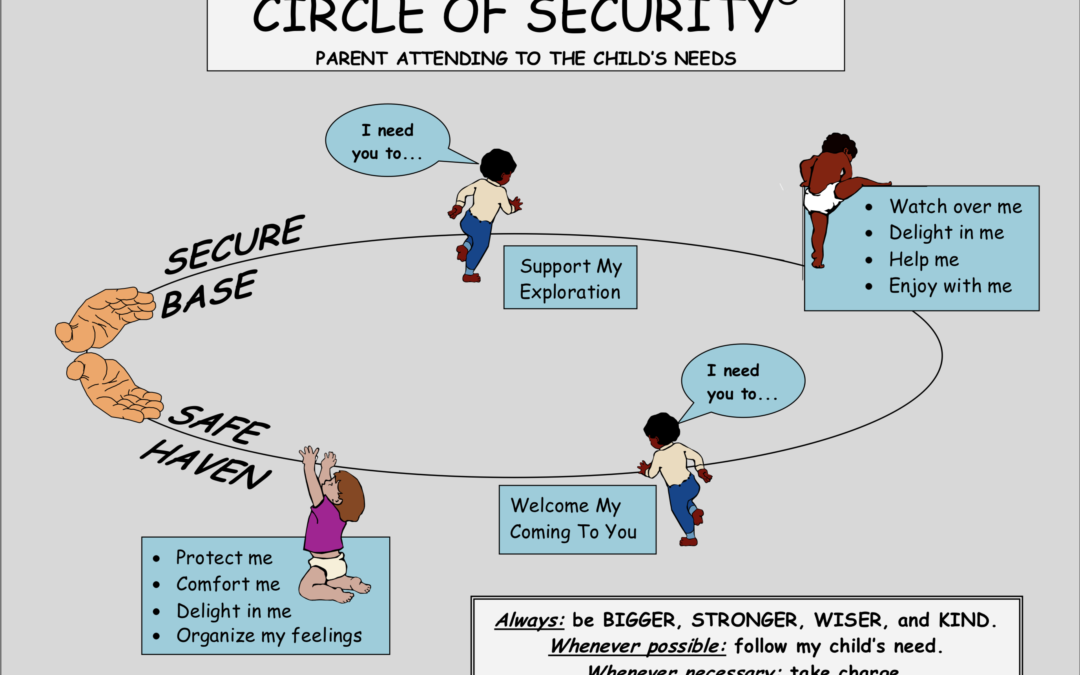

One of the best resources for how to parent for a secure attachment in the first few years of life is the new book Raising A Secure Child by Kent Hoffman, Glen Cooper, and Bert Powell, all therapists who have worked with many different kinds of families for decades. Their work is based squarely on the science of attachment, and they call their approach the Circle of Security. The circle represents the seamless ebb and flow of how babies and young children need their caregivers, at times coming close for care and comfort, and at other times following their inspiration to explore the world around them. The caregivers’ role is to tune into where on the circle their child is at the moment and act accordingly. Parenting for a secure attachment, the authors say, is not a prescriptive set of behaviors but more a state of mind, a way of “being with” the baby, a sensitivity to what they are feeling. The authors also help parents see the ways that their own attachment history shows up in their parenting and help them to make the necessary adjustments.

The neurobiology of attachment

“Attachment theory is essentially a theory of regulation,” explains Allan Schore, a developmental neuroscientist in the Department of Psychiatry at the UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine. A clinician-scientist, he has elaborated modern attachment theory over the last three decades by explaining how the attachment relationship is important to the child’s developing brain and body.

Early brain development, Schore explains, is not driven just by genetics. The brain needs social experiences to take shape. “Mother Nature and Mother Nurture combine to shape Human Nature,” he writes.

Infants grow new synapses, or neural connections, at a rate of 40,000 new synapses a second, and the brain more than doubles in volume across the first year. Genetic factors drive this early overproduction of neurons, Schore explains, but the brain awaits direction from the social environment, or epigenetic processes, to determine which synapses or connections are to be pruned, which should be maintained, and which genes are turned on or off.

One of the first areas of the brain that begins to grow and differentiate is the right brain, the hemisphere that processes emotional and social information. The right brain begins to differentiate in the last trimester in utero, whereas the left-brain development picks up in the second year of life. Some of the regions that process emotion are already present in infants’ brains at birth—the amygdala, hypothalamus, insula, cingulate cortex, and orbitofrontal cortex. But the connections among these areas develop in specific patterns over the first years of life. That’s where input from the primary relationship becomes crucial—organizing the hierarchical circuitry that will eventually process, communicate, and regulate social and emotional information.[5]

“What the primary caregiver is doing, in being with the baby,” explains Schore, “is allowing the child to feel and to identify in his own body these different emotional states. By having a caregiver simply ‘be with’ him while he feels emotions and has experiences, the baby learns how to be,” Schore says.

The part of the brain that the primary caregiver uses for intuition, feeling, and empathy to attune to the infant is also the caregiver’s right brain. So it is through “right-brain-to-right brain” reading of each other, that the parent and child synchronize their energy, emotions, and communication. And the behaviors that parents are inclined to do naturally—like eye contact and face-to-face interaction, speaking in “motherese” (higher-pitched and slower than normal speech), and holding—are just the ones shown to grow the right-brain regions in the baby that influence emotional life and especially emotion regulation.

The evidence for epigenetic effects on emotion regulation is quite solid: Early caregiving experiences can affect the expression of the genes that regulate a baby’s stress and they can shape how the endocrine system will mobilize to stress. Caregiving behaviors like responsiveness affect the development of the baby’s vagal tone (the calming system) and the hypothalamic-pituitary axis (the system that activates the body to respond to perceived danger). High quality caregiving, then, modulates how the brain and body respond to and manage stress.

High quality caregiving, then, modulates how the brain and body respond to and manage stress.

Schore points out that the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, a brain region in the right hemisphere, both has the most complex emotion and stress-regulating systems of any part in the brain and is also the center of Bowlby’s attachment control system. Neurobiological research confirms that this region is “specifically influenced by the social environment.” [6]

Stress management is not the only important part of emotion regulation. In the past, Schore explains, there was an overemphasis in the field of emotion regulation on singularly lowering the baby’s distress. But now, he says, we understand that supporting positive emotional states is equally important to creating [what he quotes a colleague as calling] a “background state of well-being.” In other words, enjoy your baby. It’s protective.

A baby’s emotion regulation begins with the caregiver, and the Goldilocks principle applies: If the caregiver’s emotions are too high, the stimulation could be intrusive to the baby, Schore explains. Too low, and the baby’s “background state” settles at a low or possibly depressive emotional baseline. Just right, from the baby’s point of view is best.

Too low, and the baby’s “background state” settles at a low or possibly depressive emotional baseline. Just right, from the baby’s point of view is best.

And babies are surprisingly perceptive at registering their feeling environment. Hoffman, Cooper and Powell write:

The youngest babies can sense ease versus impatience, delight versus resentment or irritation, comfort versus restlessness, genuine versus pretending, or other positive versus negative responses in a parent when these reactions aren’t evident to a casual observer. Little babies may pick up on the smallest sigh, the subtlest shift in tone of voice, a certain glance, or some type of body language and know the parent is genuinely comfortable or definitely not pleased.

Schore explains that in a secure attachment, the baby learns to self-regulate in two ways: One he calls “autoregulation” which is self-soothing, or using his own mind and body to manage feelings. The second is “interactive regulation” which is going to other people to help up- or down-regulate feelings. This twin thread of self-reliance and reliance on others, then, begins in the earliest months, becomes very important in the first two years of life, and continues in more subtle ways throughout the life span.

This twin thread of self-reliance and reliance on others, then, begins in the earliest months, becomes very important in the first two years of life, and continues in more subtle ways throughout the life span.

This all might sound daunting for a new parent, who could still be tempted to overdo the focus on the infant and how the connection is going—potentially leading to the same kinds of stress and guilt that the attachment parenting movement creates.

But fortunately, the caregiver doesn’t have to be 100% attuned to the baby and ongoing repairs are an important part of the process:

“The idea that a mother should never stress a baby is problematic,” Schore says. “Insecure attachments aren’t created just by a caregiver’s inattention or missteps. It also comes from a failure to repair ruptures. What is essential is the repair. Maybe the caregiver is coming in too fast and needs to back off, or maybe the caregiver has not responded, and needs to show the baby that she’s there.![]() Either way, repair is possible, and it works. Stress is a part of life, and what we’re trying to do here is to set up a system by which the baby can learn how to cope with stress.” Optimal stress, he explains, is important for stimulating the stress-regulating system.

Either way, repair is possible, and it works. Stress is a part of life, and what we’re trying to do here is to set up a system by which the baby can learn how to cope with stress.” Optimal stress, he explains, is important for stimulating the stress-regulating system.

Still, both Sroufe and Schore acknowledge the emotional labor of parenting. And they are vehement that parents need to be supported in order to have the space and freedom to care for babies.

“It takes time for parents to learn to read their baby’s signals,” Sroufe said.

Schore calls America’s failure to provide paid family leave—and we’re the only country in the world that doesn’t—the “shame of America.”

“We are putting the next generation at risk,” he explains, pointing to rising rates of insecure attachments and plummeting mental health among American youth. Parents should have at least six months of paid leave and job protection for the primary caregiver, and at least two months of the same for the secondary one, according to Schore, and Sroufe goes further, advocating for one full year of paid leave and job protection. And a recent study showed that it takes mothers a year to recover from pregnancy and delivery.

And a recent study showed that it takes mothers a year to recover from pregnancy and delivery.