Schizophrenia and relationships

Finding Love When You Have Schizophrenia: Tips on Dating

Written by Camille Noe Pagán

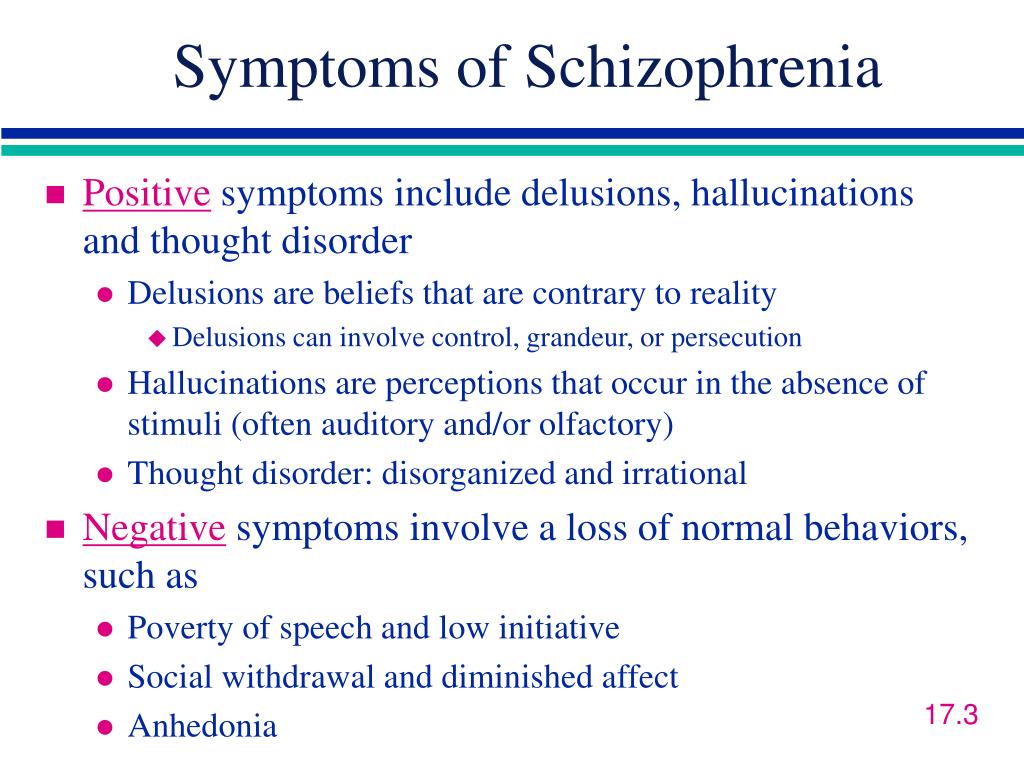

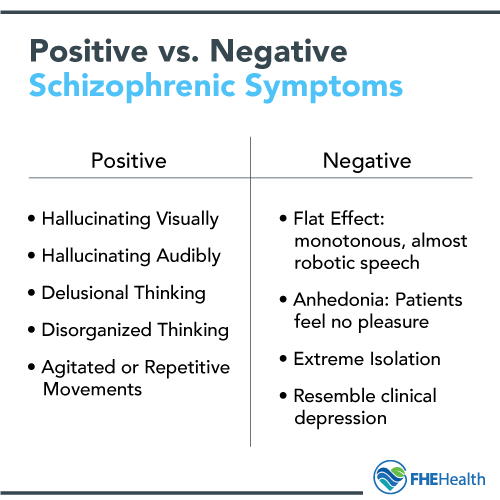

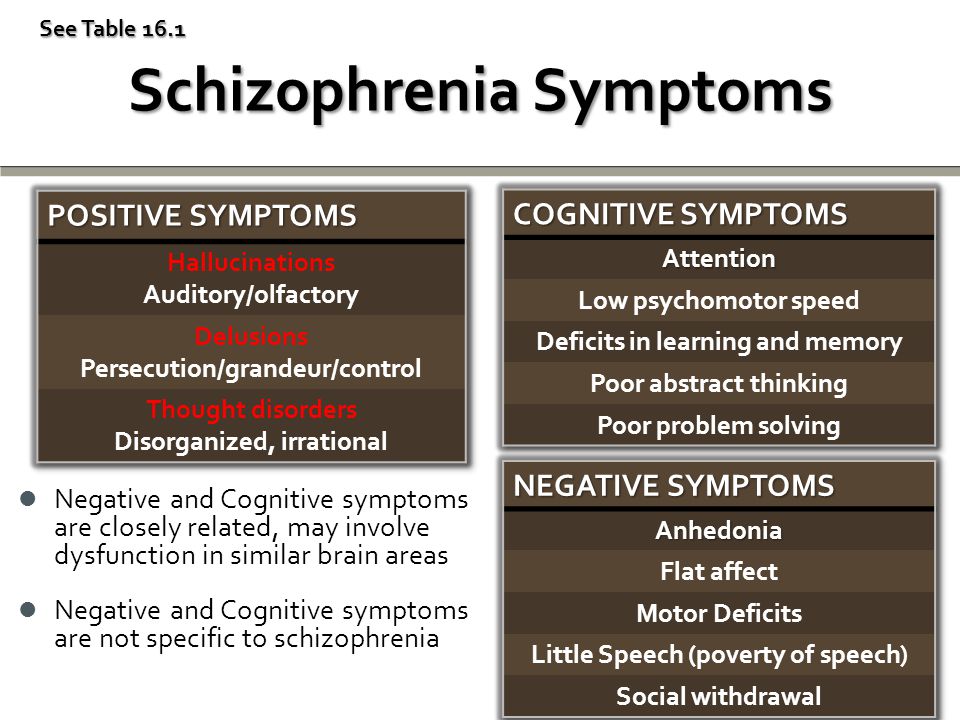

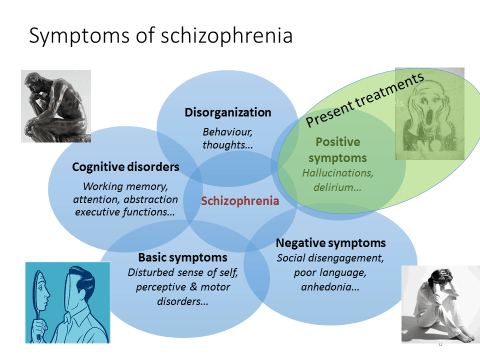

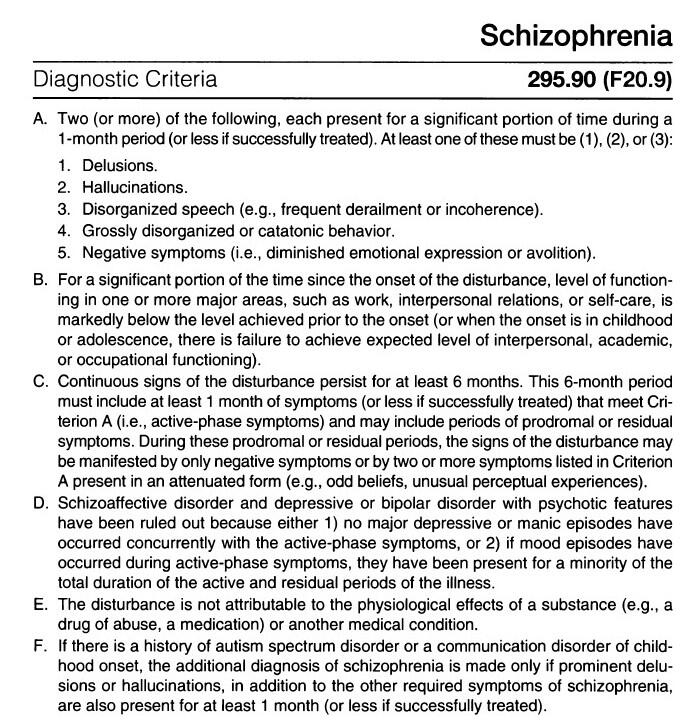

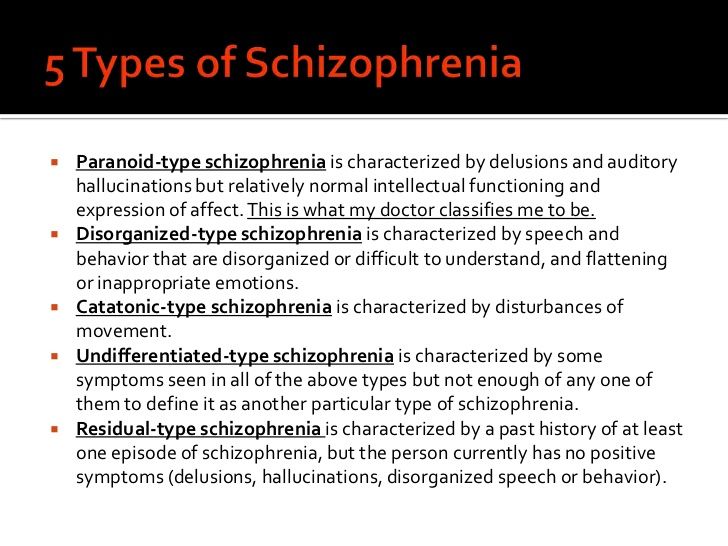

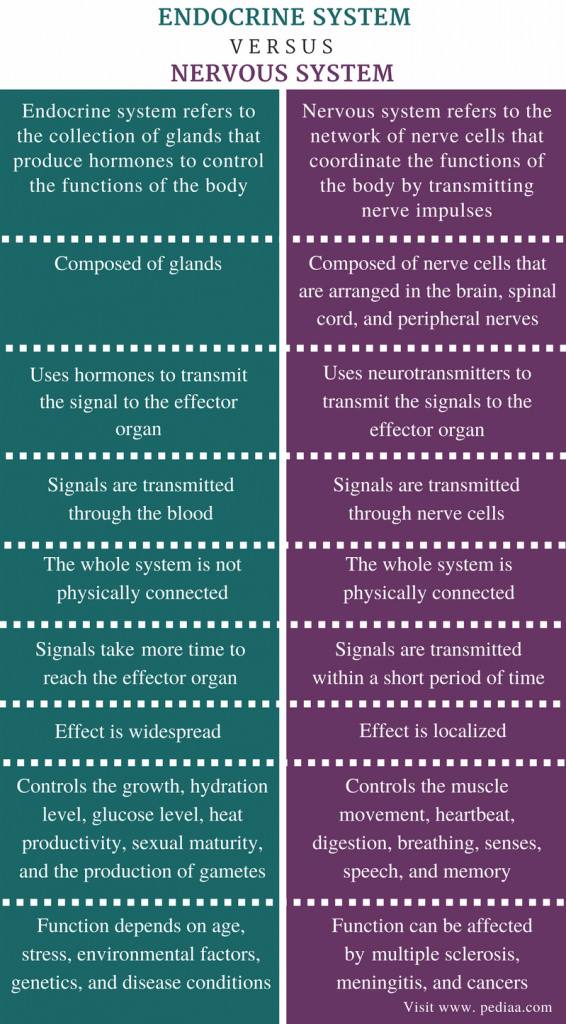

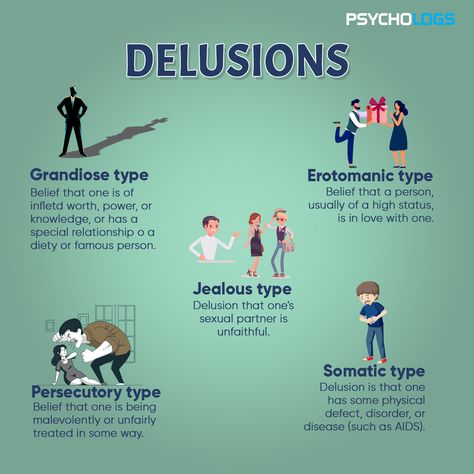

Dating can be tough for anyone. A serious mental health condition like schizophrenia adds even more challenges to the mix. At times, it can cause psychotic behaviors, like hallucinations and delusional thought processes. In severe cases, dating is probably out of the question. Even if your condition is well-treated, you may have trouble enjoying activities. It might be difficult for you to show your emotions, too.

As a result, many people with schizophrenia find it hard to start relationships and keep them. Others avoid it all together. But some are able to have healthy relationships. If you have schizophrenia or you’re romantically involved with someone who does, here’s what you need to know.

It May Not Be Right for You

You may not ever feel like or be able to pursue a romantic relationship – and that’s OK. “Your symptoms might get in the way of socializing or make you anxious,” says Lionel S. Wininger, PhD, a psychologist at Montefiore Medical Center in New York City.

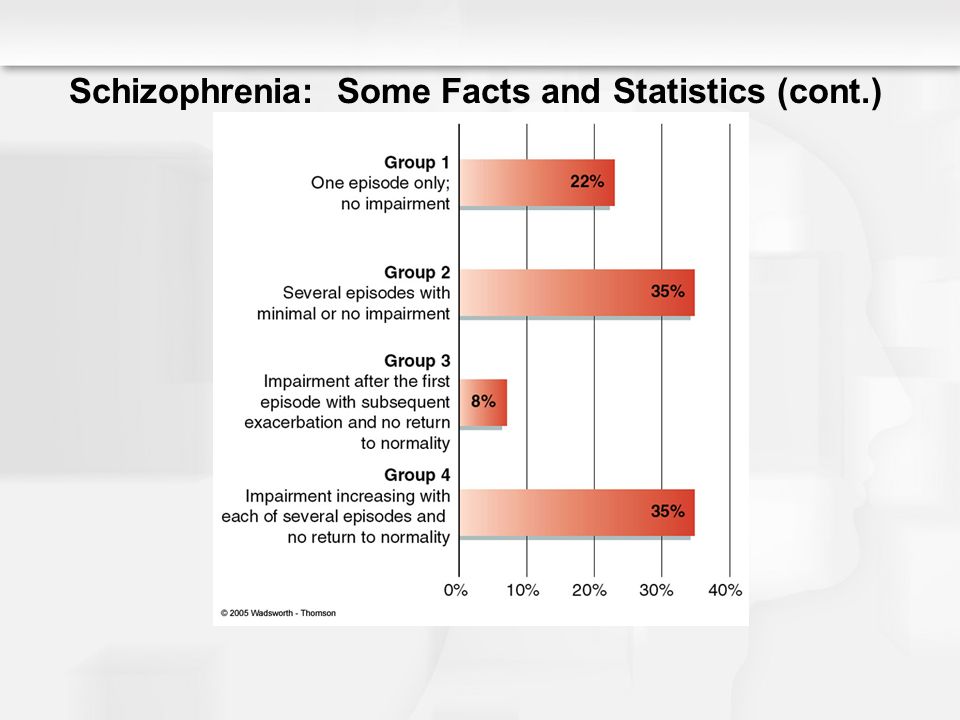

If you’re in treatment and your condition is well-controlled, it could be something to try. Though many people with schizophrenia do get worse, others do improve and can have successful relationships.

It can take a while to find a treatment plan that works. You may have to wait weeks or even months before it fully takes effect. Ask the doctor who treats your schizophrenia if they feel your plan is working and you’re ready. Besides medication, you’ll want to discuss lifestyle issues. “For example, if you spend the night at someone else’s house, do you have a plan for making sure you’re able to take your medication on schedule?” says Alex Dimitriu, MD, a psychiatrist and the founder of Menlo Park Psychiatry & Sleep Medicine in California.

You also need think about how the rest of your life is going. “Regularity is important if you have schizophrenia, and dating can disrupt that,” Dimitriu says. If you’re dealing with another big change, like a new job, location, or treatment plan, you may want to wait until you’re settled to try dating.

If you’re dealing with another big change, like a new job, location, or treatment plan, you may want to wait until you’re settled to try dating.

How Do You Let Them Know?

There have been major advances in treatment for this condition over the past several decades.

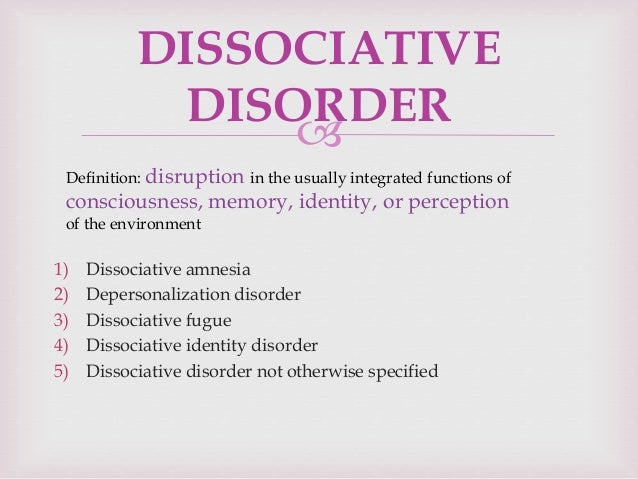

But many people don't understand mental illness well, and there can be stigma or negative labels associated with it. For instance, the person you’re seeing may have wrong ideas about what it is. For example, they may think you have multiple personalities or that you frequently hallucinate.

They may not know that most people who live with it aren’t violent and that treatment can ease and even prevent psychosis.

That’s why you may want to wait until you’ve gone out with someone a few times to tell them you have it. “Once the person has gotten to know you a little, it may be easier for them to see that you don’t fit the stereotype of someone with schizophrenia,” Wininger says.

When you’re ready, let them know you’d like to discuss something personal. You might say something like, “I want to share something important with you. It’s tough to talk about, and I hope you’ll hear me out.” Dimitriu says to stay honest and emphasize the positive.

You might say something like, “I want to share something important with you. It’s tough to talk about, and I hope you’ll hear me out.” Dimitriu says to stay honest and emphasize the positive.

For example, you could say, “I have schizophrenia, but it’s well-managed and I’ve been symptom-free for X number of months or years.” Explain that it’s a lasting mental disorder that can affect how you think, feel, and behave. Also let them know that while it can cause severe symptoms, you can also treat it so that you avoid these problems in the future.

It’s possible that your partner may have a negative reaction after they find out. Know that surprise and discomfort are normal. If the person cares for you and wants to keep seeing you, they’ll find a way to support you.

With schizophrenia, it may seem hard to hone your social skills and build long-lasting relationships. But with effort and proper treatment, it can be done. One way to build those skills is to join a support group where you can meet people who understand and help with what you’re going through. Building strong relationships can help you feel understood and supported in staying on track with your treatment.

Building strong relationships can help you feel understood and supported in staying on track with your treatment.

Of course, support doesn’t have to come from romantic partners. But sometimes, putting yourself out there – when you're ready – can be rewarding.

Tips to Make Dating Better

If your doctor gives you the green light and you feel ready:

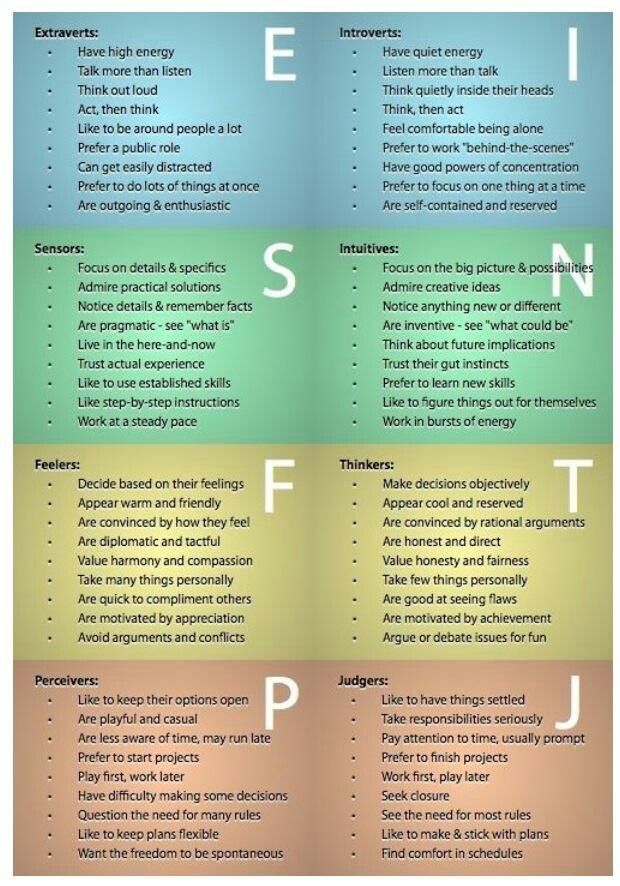

Keep your expectations in check. Even if your condition is well-managed and you feel good, keep in mind that it may cause social anxiety and other issues that can make it a challenge to date. You could have trouble with focus or flat affect (when your voice and facial expressions don’t express your emotions). You may not speak as much as other people do, which can make it tough to communicate. It can help to work through some of these issues with a therapist. You’ll find ways to feel better about yourself and your condition.

Take it slow.Stress can make schizophrenia harder to manage. That’s why it’s smart to ease into a relationship. You may want to choose low-key activities, like a meetup for coffee or a walk together, for your early dates. If it heats up, “It’s important to try to keep the rest of your life as regular as possible so you can stick with your treatment plan,” Dimitriu says.

That’s why it’s smart to ease into a relationship. You may want to choose low-key activities, like a meetup for coffee or a walk together, for your early dates. If it heats up, “It’s important to try to keep the rest of your life as regular as possible so you can stick with your treatment plan,” Dimitriu says.

Know that sexual side effects are common. Your medications may impact your interest in sex or ability to get aroused or achieve orgasm. If you do have sexual side effects from medication, talk to your doctor and partner about them. It could help to switch medications.

Take a team approach. If you and your partner get serious, you may want to bring them to doctor appointments or therapy sessions. “A committed partner probably knows you better than your health care provider does,” Wininger says. “They can check in with you and help you pay attention to important signs [that you need to adjust your treatment], like feeling more down than usual. ” A partner’s support can be one more way to live better with schizophrenia.

” A partner’s support can be one more way to live better with schizophrenia.

Relationships and Schizophrenia | Everyday Health

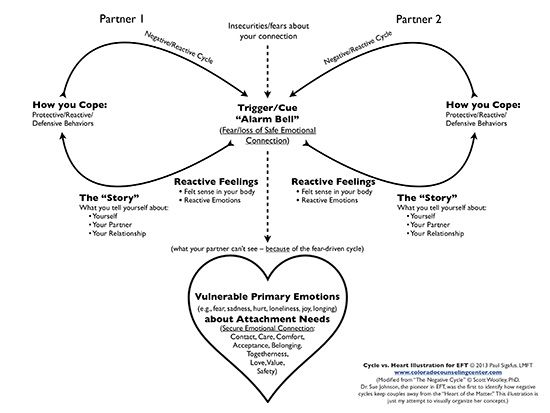

Every relationship has its ups and downs, but when one person is diagnosed with schizophrenia, it’s possible for even stable partnerships to become strained or for couples to break up altogether.

“Schizophrenia makes it hard for people to form close bonds,” says Dost Öngür, MD, clinical director of the Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder Research Program at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts. Often, people with schizophrenia who are married met their partner before being diagnosed with the condition. Single people who have schizophrenia, however, “tend to stay single,” he says.

For people whose partner was healthy when the relationship began, the onset of schizophrenia can come as a shock. The disease can change a person’s behavior and personality, and symptoms can make even the most caring and loving individuals appear distant and cold.

Frank Baron, who has schizoaffective disorder, a type of mental illness that triggers symptoms similar to schizophrenia, says that when someone is newly diagnosed with a disorder like schizophrenia, their loved ones should try to show compassion. “The best thing to say is, ‘I love you and I care about you. This doesn’t change how I feel about you,’” he says.

Caring for a loved one who has schizophrenia can be a huge job that’s both tiring and frustrating at times. The following advice can help keep the relationship going strong. To find more resources, you can also contact your local chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) or ask your doctor or therapist for information about local support groups.

- The caregiver should set up their own support system. If your partner has schizophrenia, they may not be able to meet your emotional needs as well as they once did. Plus, according to a study published in October 2017 in the journal Psychiatric Services, caregivers to people who have schizophrenia tend to experience relatively high levels of distress.

That’s why it’s important to have access to mental health support, such as a counselor or therapist. Friends and family can also provide a listening ear or a much-needed distraction.

That’s why it’s important to have access to mental health support, such as a counselor or therapist. Friends and family can also provide a listening ear or a much-needed distraction. - The person who has schizophrenia must accept treatment. Left untreated, the condition can cause people to behave erratically, leaving their partners to become subject to verbal abuse, emotional neglect, and delusional accusations. No healthy relationship can sustain these behaviors.

- Both partners must communicate. Open and clear communication can help people who have schizophrenia find the support they need as well as understand what’s expected of them in the relationship. In addition to individual therapy, couples therapy can help both partners cope with the effects of schizophrenia on the relationship.

Every couple juggles everyday tasks like household chores and balancing finances, but people who have schizophrenia may need extra help managing their responsibilities. This may include:

This may include:

- Household duties Dr. Öngür explains that schizophrenia impacts the way people read social cues, meaning your partner may not be able to recognize what you want them to do around the house. Counseling can help caregivers learn how to set clear expectations in a supportive and positive way. Defining each partner’s responsibilities around the house is another strategy.

- Finances People who have schizophrenia are not always able to work, even after their symptoms are stabilized. If this is the case, applying for Social Security disability benefits can help. Medications for schizophrenia can be expensive, and frequent co-pays can add up. Let your doctors know about your financial situation as well, because some clinics charge on a sliding scale.

- Intimacy Schizophrenia may cause people to become less interested in sex, as can some antipsychotic medications. Try talking to a couples therapist, who can help you express your needs and wants.

You can also ask your partner’s doctor about switching to medications that are less likely to affect libido or adding drugs that can boost sexual response.

You can also ask your partner’s doctor about switching to medications that are less likely to affect libido or adding drugs that can boost sexual response. - Family interactions People who have schizophrenia can behave irrationally, have trouble thinking clearly, and struggle with everyday emotions, which can be confusing, frightening, or hurtful to family members and lead to conflicts within the family. It’s important to clearly define acceptable and unacceptable behaviors at home and in other settings, especially if you have children.

5 Beneficial Foods for People With Schizophrenia

Potentially life-shortening conditions like diabetes and obesity are common among people with schizophrenia, which is one reason being mindful of food...

By Fran Kritz

Schizophrenia and Pregnancy: What to Know

Medication plays an important role in controlling schizophrenia symptoms. Speak with your doctor before stopping any psychiatric medicines. Schizophrenia...

Speak with your doctor before stopping any psychiatric medicines. Schizophrenia...

By Lindsey Konkel

Schizophrenia Treatment

Schizophrenia, a brain disorder, is not curable, but symptoms can be treated and minimized. Learn about the symptoms of schizophrenia and treating this...

By Lindsey Konkel

What Is Schizophrenia? Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Schizophrenia is a serious mental disorder that can include hallucinations and delusions. Learn about the definition, diagnosis and latest medical treatment...

By Lindsey Konkel

What Is Schizoaffective Disorder?

Schizoaffective disorder is a rare mental illness related to schizophrenia, a brain disorder. People with schizoaffective disorder experience symptoms...

People with schizoaffective disorder experience symptoms...

By Lindsey Konkel

Schizophrenia Signs and Symptoms

Schizophrenia, a brain disorder, can cause hallucinations, delusions, and other unusual behaviors. Learn about schizophrenia signs and symptoms.

By Lindsey Konkel

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia- Healthcare issues »

- A

- B

- B

- G

- D

- E

- and

- 9000 About

- P

- P

- With

- T

- U

- F

- x

- S

- B

- E

- S

- I

005

- Popular Topics

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Data and statistics »

- News bulletin

- The facts are clear

- Publications

- Find country »

- A

- B

- C

- g

- D

- E

- and

- th

- K

- L

- 9000 N

- 9000

- in

- f

- x

- C

- hours

- Sh

- Sh.

- 9000 WHO in countries »

- Reporting

- Regions »

- Africa

- America

- Southeast Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- Media Center

- Press releases

- Statements

- Media messages

- Comments

- Reporting

- Online Q&A

- Events

- Photo reports

- case studies

- Questions and answers

- Speeches

- Update

- Emergencies "

- News "

- Disease Outbreak News

- WHO data »

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Monitoring Dashboard

- Basic moments "

- About WHO »

- CEO

- About WHO

- WHO activities

- Where does WHO work?

- Governing Bodies »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive committee

- Main page/

- Media Center /

- Newsletters/

- Read more/

- Schizophrenia

Key Facts

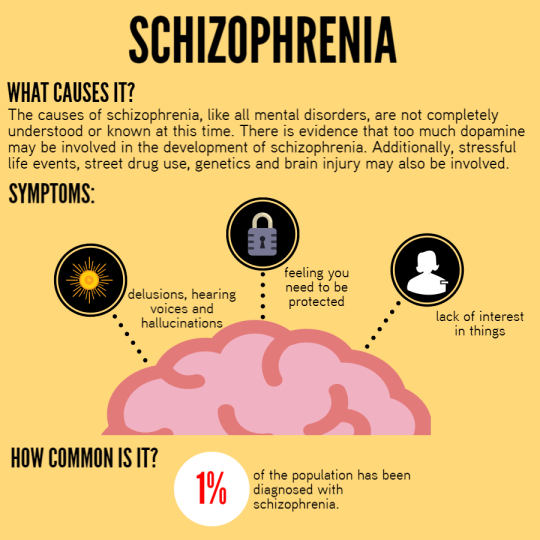

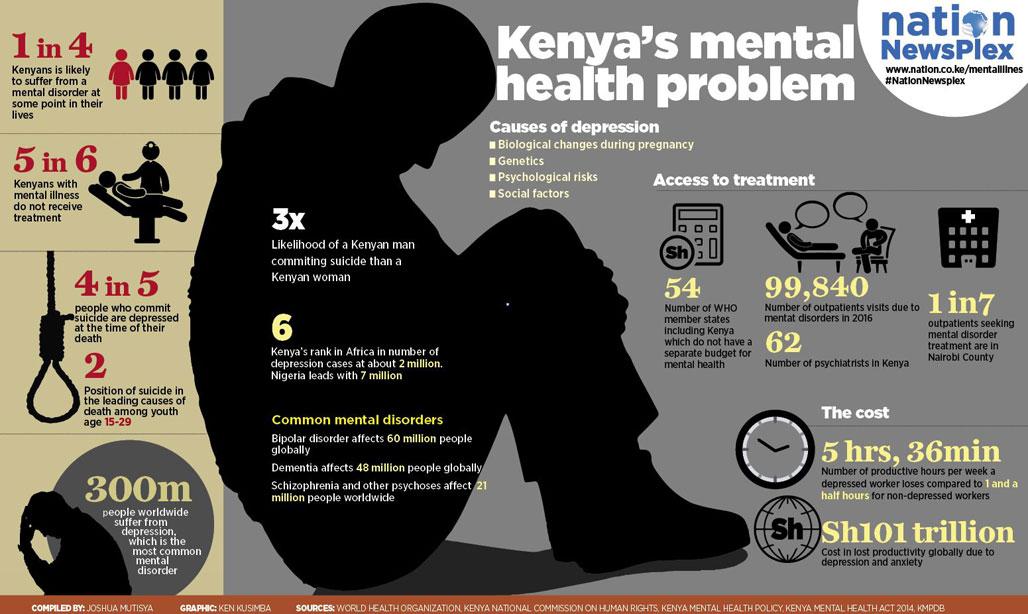

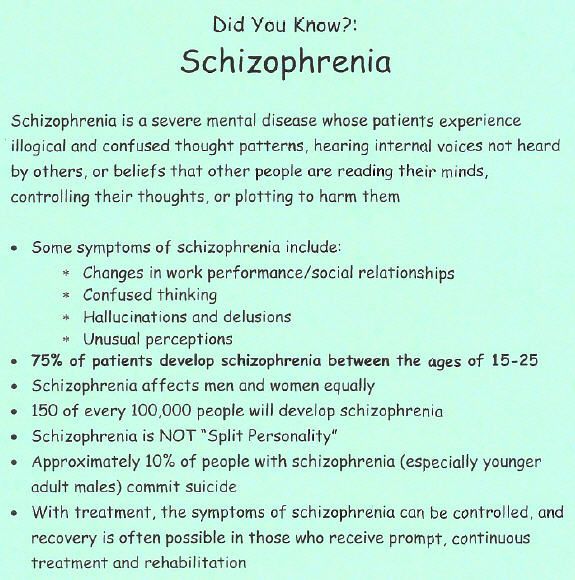

- Schizophrenia is a severe mental disorder that affects approximately 24 million people, or 1 in 300 people worldwide.

- Schizophrenia causes psychosis, is associated with severe disability, and can negatively affect all areas of life, including personal, family, social, academic and work life.

- People with schizophrenia are often subject to stigma, discrimination and human rights violations.

- Worldwide, more than two thirds of people with psychosis do not receive specialized mental health care.

- There are a number of effective options for helping patients with schizophrenia, which can lead to a complete recovery of at least one in three patients.

Symptoms

Schizophrenia is characterized by significant disturbances in the perception of reality and behavioral changes, such as:

People with schizophrenia often also experience persistent cognitive or thinking problems that affect memory, attention, or problem-solving skills.

At least one third of patients with schizophrenia experience complete remission of symptoms (1). In some, periods of remission and exacerbation of symptoms follow each other throughout life, in others there is a gradual increase in symptoms.

Scope and impact

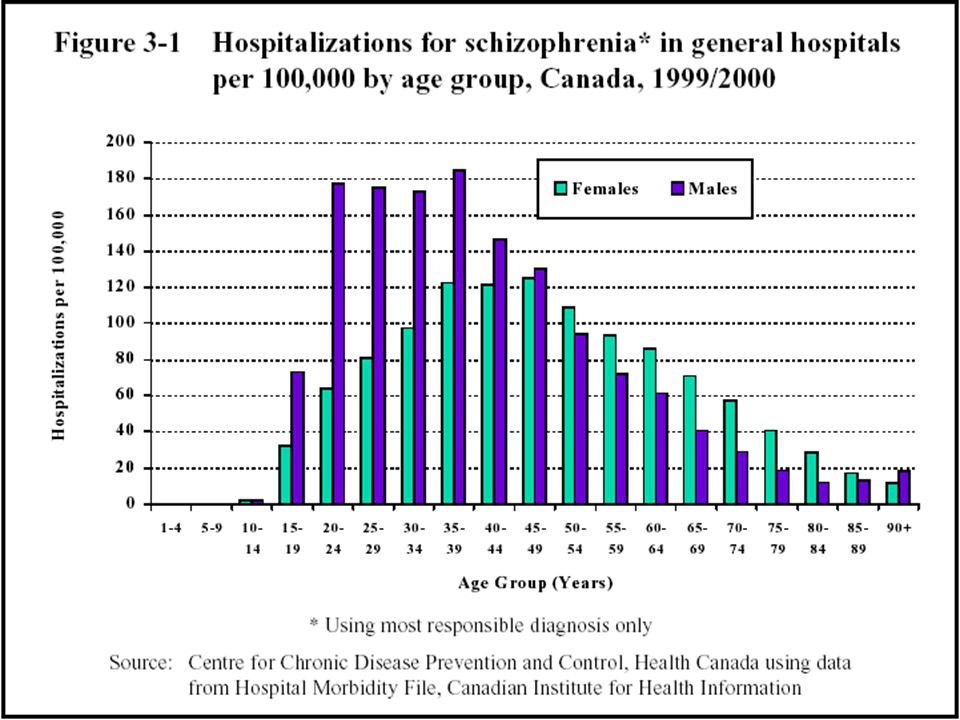

Schizophrenia affects approximately 24 million people, or 1 in 300 people (0.32%) worldwide. Among adults, the rate is 1 in 222 (0.45%) (2). Schizophrenia is less common than many other mental disorders. Onset is most common in late adolescence and between the ages of 20 and 30; while women tend to have a later onset of the disease.

Schizophrenia is often accompanied by significant stress and difficulties in personal relationships, family life, social contacts, studies, work or other important areas of life.

People with schizophrenia are 2-3 times more likely to die early than the population average (2). It is often associated with physical illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic disease, and infectious disease.

It is often associated with physical illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic disease, and infectious disease.

Patients with schizophrenia often become the object of human rights violations both within the walls of psychiatric institutions and in everyday life. Significant stigmatization of people with this disease is a widespread phenomenon that leads to their social isolation and has a negative impact on their relationships with others, including family and friends. This creates grounds for discrimination, which in turn limits access to health services in general, education, housing and employment.

Humanitarian emergencies and health crises can cause intense stress and fear, disrupt social support mechanisms, lead to isolation and disruption of health services and supply of medicines. All these shocks can have a negative impact on the lives of people with schizophrenia, in particular by exacerbating existing symptoms of the disease. People with schizophrenia are more vulnerable during emergencies to various human rights violations and, in particular, face neglect, abandonment, homelessness, abuse and social exclusion.

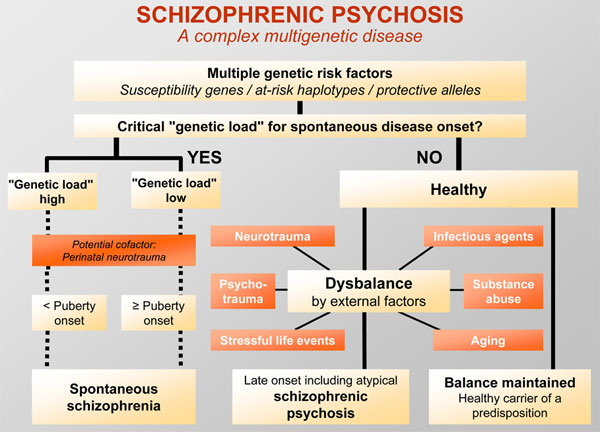

Causes of schizophrenia

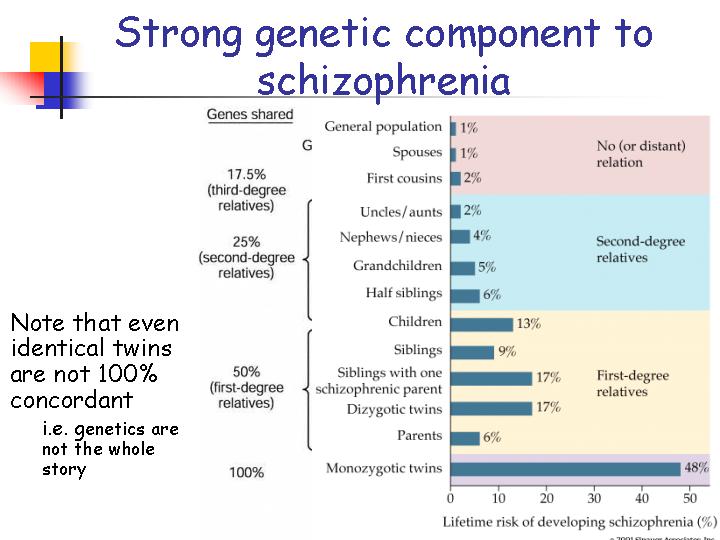

Science has not established any single cause of the disease. It is believed that schizophrenia may be the result of the interaction of a number of genetic and environmental factors. Psychosocial factors may also influence the onset and course of schizophrenia. In particular, heavy marijuana abuse is associated with an increased risk of this mental disorder.

Assistance services

At present, the vast majority of people with schizophrenia do not receive mental health care worldwide. Approximately 50% of patients in psychiatric hospitals are diagnosed with schizophrenia (4). Only 31.3% of people with psychosis get specialized mental health care (5). Much of the resources allocated to mental health services are inefficiently spent on the care of patients admitted to psychiatric hospitals.

Available scientific evidence clearly indicates that hospitalization in psychiatric hospitals is not an effective way of providing care for mental disorders and is regularly associated with the violation of the fundamental rights of patients with schizophrenia. Therefore, it is necessary to ensure the expansion and acceleration of work on the transfer of functions in the field of mental health care from psychiatric institutions to the level of local communities. Such work should begin with the organization of the provision a wide range of quality community-based mental health services. Options for community-based mental health care include integrating this type of care into primary health care and hospital care. general care, setting up community mental health centres, outpatient care centres, social housing with nursing care and social home care services. Involvement in the care process is important the patient with schizophrenia, his family members and members of local communities.

Therefore, it is necessary to ensure the expansion and acceleration of work on the transfer of functions in the field of mental health care from psychiatric institutions to the level of local communities. Such work should begin with the organization of the provision a wide range of quality community-based mental health services. Options for community-based mental health care include integrating this type of care into primary health care and hospital care. general care, setting up community mental health centres, outpatient care centres, social housing with nursing care and social home care services. Involvement in the care process is important the patient with schizophrenia, his family members and members of local communities.

Schizophrenia management and care

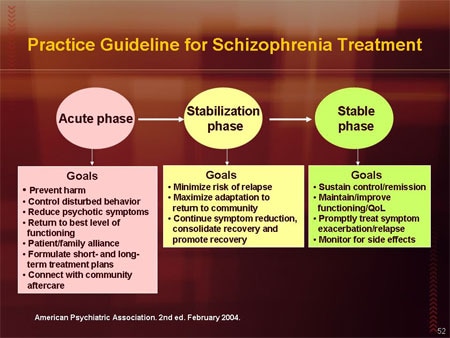

There are a number of effective approaches to treating people with schizophrenia, including medication, psychoeducation, family therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and psychosocial rehabilitation (eg, life skills education). The most important interventions for helping people with schizophrenia are assisted living, special housing and employment assistance. It is extremely important for people with schizophrenia and their families and/or caregivers to a recovery-centered approach that empowers people to participate in decisions about their care.

The most important interventions for helping people with schizophrenia are assisted living, special housing and employment assistance. It is extremely important for people with schizophrenia and their families and/or caregivers to a recovery-centered approach that empowers people to participate in decisions about their care.

WHO activities

the steps necessary to ensure that appropriate services are provided to people with mental disorders, including schizophrenia. One of the key recommendations The action plan is to transfer the function of providing assistance from institutions to local communities. WHO Special Mental Health Initiative aims to further progress towards the goals of the Comprehensive Plan mental health action 2013–2030 by ensuring that 100 million more people have access to quality and affordable mental health care.

The WHO Mental Health Gap Action Program (mhGAP) is working to develop evidence-based technical guidelines, tools and training packages to scale up services in countries, especially in low-resource settings. The program focuses on a priority list of mental health disorders, including psychosis, and aims to strengthen the capacity of non-specialized health workers in as part of an integrated approach to mental health care at all levels of care. To date, the mhGAP Program has been implemented in more than 100 WHO Member States.

The program focuses on a priority list of mental health disorders, including psychosis, and aims to strengthen the capacity of non-specialized health workers in as part of an integrated approach to mental health care at all levels of care. To date, the mhGAP Program has been implemented in more than 100 WHO Member States.

The WHO QualityRights project aims to improve the quality of care and better protect human rights in mental health and social care settings and to expand opportunities of various organizations and associations to defend the rights of persons with mental disorders and psychosocial disabilities.

The WHO guidelines on community mental health services and human rights-based approaches provide information for all stakeholders who intend to develop or transform mental health systems and services. health in accordance with international human rights standards, including the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Bibliography

(1) Harrison G, Hopper K, Craig T, Laska E, Siegel C, Wanderling J. Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:506-17.

Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:506-17.

(2) Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx). http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool?params=gbd-api-2019-permalink/27a7644e8ad28e739382d31e77589dd7 (accessed 25 September 2021)

(3) LaursenTM, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB. Excess early mortality in schizophrenia. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology , 2014;10, 425-438.

(4) WHO. Mental health systems in selected low- and middle-income countries: a WHO-AIMS cross-national analysis. WHO: Geneva, 2009

(5) Jaeschke K et al. Global estimates of service coverage for severe mental disorders: findings from the WHO Mental Health Atlas 2017 Glob Ment Health 2021;8:e27.

Peculiarities of attitude to humor and laughter in patients with schizophrenia

Recently, sense of humor has been considered [1] as not only a socially desirable personality trait, but also an important component of mental health. Great importance is given to the study of humor as a way of stimulating positive emotions and resisting negative ones, the mechanism of coping behavior, the role of humor in establishing and maintaining social contacts. Worthy of attention were questions about the adequacy of the use of humor, the intellectual features of its understanding, as well as the features of emotional reactions to the humor of others.

Great importance is given to the study of humor as a way of stimulating positive emotions and resisting negative ones, the mechanism of coping behavior, the role of humor in establishing and maintaining social contacts. Worthy of attention were questions about the adequacy of the use of humor, the intellectual features of its understanding, as well as the features of emotional reactions to the humor of others.

Features of the sense of humor and the attitude towards it in mentally ill people have been studied little. There are two points of view in the existing literature. According to one of them [2], with mental disorders, a decrease in the sense of humor is supposed. According to the second, its nosological conditionality matters [3-6]. So, some researchers have found that patients with schizophrenia have difficulty understanding humor, patients with affective disorders understand humor well, but are characterized by suppressed laughter activity and a decrease in the ability to produce humor, with epilepsy, the viscosity of patients does not allow them to understand the essence of a joke in many details, which leads to to the loss of its meaning, patients with organic brain pathology are characterized by a decrease in the ability to understand the meaning of a joke.

A little over 10 years ago, within the framework of clinical studies by M. Titze [7], the concept of gelotophobia (from the Greek "gelos" - laughter) was first introduced - the fear of looking ridiculous, as a form of social phobia, the criteria for which are formulated in the ICD-10. The key symptoms of gelotophobia are the belief in one's own comicality, the patient's expectation that they will be laughed at, "frozenness" of physiological manifestations, expressiveness, loss of spontaneity and increased self-control [7, 8].

Clinical studies of gelotophobia have shown that the fear of being ridiculed in mental disorders is higher than in healthy individuals [6, 7, 9]. M. Titze [7] noted the severity of gelotophobia in patients with depression. G. Forabosco et al. [6] found that the severity of gelotophobia is higher in patients with schizophrenia and patients with personality disorders than with mood disorders, anxiety and eating disorders. The results of a study by domestic authors [9] indicate that gelotophobia in patients with mental disorders is associated with feelings of fear, while in healthy individuals it is more with a sense of shame.

Within the framework of the concept of gelotophobia, two new phenomena were also identified: gelotophilia - the tendency to expose oneself as an object of laughter and catagelasticism - the tendency to ridicule others [10]. Gelotophiles look for or create situations in which they can make others laugh. Such people perceive humor not as a belittling of their own merits, but as a way to attract the attention of others and an opportunity to experience positive emotions. Catagelasticists actively seek out and prefer situations in which they can make fun of others.

The study of these phenomena in mentally healthy subjects showed [10] that gelotophobia and catagelasticism are significantly associated with gelotophilia, but gelotophobia is negative, and catagelasticism is positive. This means that "gelotophobes" do not tend to specifically look for situations in which they can be the object of ridicule, and "gelotophiles" not only create such situations, but also will not miss the chance to make fun of others, if any. Among the “gelotophobes” there are both “non-catagelasticists” and “catagelasticists”, who, despite experiencing the trauma of ridicule, can also laugh at others.

Among the “gelotophobes” there are both “non-catagelasticists” and “catagelasticists”, who, despite experiencing the trauma of ridicule, can also laugh at others.

The aim of the study was to study the severity of gelotophobia, gelotophilia and catagelasticism in patients with schizophrenia in comparison with a group of mentally healthy individuals.

Based on the analysis of data available in the literature, two hypotheses were formulated: 1. Gelotophobia is more pronounced, while gelotophilia and catagelasticism are less pronounced in the group of patients with schizophrenia compared to mentally healthy people. 2. Gelotophobia in patients with schizophrenia decreases as the duration of the disease increases.

Material and methods

The clinical study was carried out at the Mental Health Research Center of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, as well as at the Moscow Psychiatric Hospital No. 13.

The main group of the surveyed consisted of 86 patients with schizophrenia, 66 men and 20 women, aged 18 to 35 years. In this group, there were 25 people with schizotypal disorder (sluggish schizophrenia) according to ICD-10, heading F 21.0; 61 patients were diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia (F 20.0). Within the framework of paranoid schizophrenia, subgroups of 21 patients with one attack of the disease and 40 with more than one attack were identified. The duration of the disease (the period from the beginning of the diagnosis according to the anamnesis to the moment of psychological examination) in the studied cases ranged from 1 to 15 years. All patients were examined at the exit from the acute state before discharge from the hospital.

In this group, there were 25 people with schizotypal disorder (sluggish schizophrenia) according to ICD-10, heading F 21.0; 61 patients were diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia (F 20.0). Within the framework of paranoid schizophrenia, subgroups of 21 patients with one attack of the disease and 40 with more than one attack were identified. The duration of the disease (the period from the beginning of the diagnosis according to the anamnesis to the moment of psychological examination) in the studied cases ranged from 1 to 15 years. All patients were examined at the exit from the acute state before discharge from the hospital.

The study did not include patients with severe thinking disorders and organic brain pathology.

The control group consisted of practically healthy individuals (mostly students of Moscow universities) - 125 people, 78 men and 47 women aged 18 to 35 years.

The main research method was the questionnaire of gelotophobia, gelotophilia and catagelasticism (PhoPhiKat), developed by W. Ruch and R. Proyer [8, 11] and tested by us [12] on a Russian-speaking sample. The initial version is a questionnaire of 45 items, but during testing it was decided to exclude 10 of them with unsatisfactory psychometric characteristics. Therefore, the short version recommended for use consists of 30 affirmatively worded sentences, which are proposed to be evaluated on a scale from 1 to 4, where 1 - “strongly disagree”, 4 - “strongly agree”; each scale includes 10 items.

Ruch and R. Proyer [8, 11] and tested by us [12] on a Russian-speaking sample. The initial version is a questionnaire of 45 items, but during testing it was decided to exclude 10 of them with unsatisfactory psychometric characteristics. Therefore, the short version recommended for use consists of 30 affirmatively worded sentences, which are proposed to be evaluated on a scale from 1 to 4, where 1 - “strongly disagree”, 4 - “strongly agree”; each scale includes 10 items.

Statistical processing of data was performed using the statistical package IBM SPPS Statistics 20, using Student's t-test, Pearson correlation analysis, univariate analysis of variance (general multivariate).

Results and discussion

It was found that the mean index (M) of gelotophobia in the group of patients with schizophrenia was significantly higher than in the control group ( t =6.1, with p <0.001; Mcontrol=1.78, Mschizophrenia=2.19), which corresponds to the literature data [6, 9]. When analyzing gelotophobia in subgroups of patients with schizophrenia, it turned out that gelotophobia is more pronounced in the subgroup of paranoid schizophrenia with one attack than with a larger number of them ( t \u003d 2.68 at p <0.01; Mod one attack \u003d 1.81, M more than one seizure = 2.09).

When analyzing gelotophobia in subgroups of patients with schizophrenia, it turned out that gelotophobia is more pronounced in the subgroup of paranoid schizophrenia with one attack than with a larger number of them ( t \u003d 2.68 at p <0.01; Mod one attack \u003d 1.81, M more than one seizure = 2.09).

As for catagelasticism, in the control group its indicators were significantly higher than in patients with schizophrenia ( t = -2.45 at p <0.01; M healthy = 2.59; Mschizophrenia=2.36). No differences were found between subgroups of patients.

When comparing the average indicators of gelotophilia, no significant differences were found between the main and control groups. However, there were significant differences between patients with indolent schizophrenia and the subgroup with paranoid schizophrenia with one attack ( t = 2.56 vs. p < 0.05; M = 1.89 and M = 2.35, respectively).

It has already been mentioned above that gelotophilia may not be associated with shame, and in some age groups it may even negatively correlate with it [10, 13]. In this case, our result is correlated with the point of view [14], according to which the feeling of shame is much more typical for people with schizoid personality disorder than for people with schizophrenia, for whom the opinions of others are often indifferent. Patients with personality disorders believe that they have a certain quality that elevates them above the rest of the "ordinary" people, although they realize that in fact this opinion is not supported by others. It is natural that the desire to be in the center of attention in this group will be much less pronounced due to the fear of a negative assessment from others [14]. At the same time, there are no significant differences in the severity of gelotophilia in sluggish and paranoid schizophrenia with more than one attack. This is probably due to a significant emotional and personality defect in such patients, combined with indifference to the opinions of others.

In this case, our result is correlated with the point of view [14], according to which the feeling of shame is much more typical for people with schizoid personality disorder than for people with schizophrenia, for whom the opinions of others are often indifferent. Patients with personality disorders believe that they have a certain quality that elevates them above the rest of the "ordinary" people, although they realize that in fact this opinion is not supported by others. It is natural that the desire to be in the center of attention in this group will be much less pronounced due to the fear of a negative assessment from others [14]. At the same time, there are no significant differences in the severity of gelotophilia in sluggish and paranoid schizophrenia with more than one attack. This is probably due to a significant emotional and personality defect in such patients, combined with indifference to the opinions of others.

The use of Pearson's correlation analysis made it possible to establish a positive correlation between gelotophilia and catagelasticism in the group of both patients with schizophrenia and mentally healthy people ( r = 0. 620 with p = 0.000; r = 0.432 with p

620 with p = 0.000; r = 0.432 with p

Correlation analysis also found that in a subgroup of patients with paranoid schizophrenia with more than one attack, the severity of gelotophobia significantly decreases as the duration of the disease increases ( r = -0.727 at p <0. 001). In the subgroup of patients with one attack and the group of patients with indolent schizophrenia, no changes in gelotophobia were noted depending on the duration of the disease.

001). In the subgroup of patients with one attack and the group of patients with indolent schizophrenia, no changes in gelotophobia were noted depending on the duration of the disease.

The most pronounced defective states in schizophrenia [15] with apatoabulic syndrome may be the cause of indifference to the assessment of others. Presumably, patients with the first attack and patients with indolent schizophrenia at a young age do not have time to achieve this degree of defectiveness, while patients who have had several attacks have higher values of gelotophobia. Characteristic neurosis-like symptoms, increased sensitivity, and emotional lability may be an additional reason to explain the high values of gelotophobia in this group [16].

In a univariate analysis of variance, it was found that in men and women, differences in the severity of gelotophilia and catagelasticism between the main and control groups are of the opposite nature: compared with the control group in schizophrenia, gelotophilia is significantly higher in women, and significantly lower in men (F = 7. 024 at p = 0.009). A similar effect is observed in the case of catagelasticism (F=15.89 at p =0.000). Thus, high values of catagelasticism and gelotophilia, which are typical for normal men, are more characteristic of women in schizophrenia. These results are consistent with literature data [13] that healthy men are more likely to look for a reason to laugh at others, more often use humor for competitive purposes, while women are more likely to use it for social support. Few studies of the gender characteristics of schizophrenia indicate that women are more likely to be diagnosed with affective symptoms, emotional expressiveness, anger and incontinence, which correlates with high gelotophilia and catagelasticism in this group of subjects. In men, cognitive deficits and negative symptoms, complaisance and passivity are observed, which may correspond to low values of gelotophilia and catagelasticism in this group [17]. Thus, we can talk about an increase in activity in relation to humor and laughter in women with schizophrenia and a decrease in men.

024 at p = 0.009). A similar effect is observed in the case of catagelasticism (F=15.89 at p =0.000). Thus, high values of catagelasticism and gelotophilia, which are typical for normal men, are more characteristic of women in schizophrenia. These results are consistent with literature data [13] that healthy men are more likely to look for a reason to laugh at others, more often use humor for competitive purposes, while women are more likely to use it for social support. Few studies of the gender characteristics of schizophrenia indicate that women are more likely to be diagnosed with affective symptoms, emotional expressiveness, anger and incontinence, which correlates with high gelotophilia and catagelasticism in this group of subjects. In men, cognitive deficits and negative symptoms, complaisance and passivity are observed, which may correspond to low values of gelotophilia and catagelasticism in this group [17]. Thus, we can talk about an increase in activity in relation to humor and laughter in women with schizophrenia and a decrease in men.

The study allows us to draw the following conclusions: gelotophobia in the group of patients with schizophrenia is more pronounced, and catagelasticism is less than in the group of mentally healthy people. This is a confirmation of the maladaptiveness of gelotophobia and its correspondence to mental illness and the greater adaptability of catagelasticism and its correspondence to mental health.

In schizophrenia, the severity of gelotophobia varies depending on the form of the course, the number of attacks and the duration of the disease. The greatest severity of gelotophobia is observed in a subgroup of patients with sluggish schizophrenia, as well as paranoid schizophrenia with one attack. In the group of patients with paranoid schizophrenia with more than one attack, the indicators of gelotophobia are significantly lower and decrease as the duration of the disease increases. If high indicators of gelotophobia in healthy individuals may reflect personality traits, then similar indicators in patients with schizophrenia correspond to a less pronounced emotional and personality defect and less gross violations of thinking.