Choosing not to eat

NIMH » Eating Disorders: About More Than Food

What are eating disorders?

Eating disorders are serious, biologically influenced medical illnesses marked by severe disturbances to one’s eating behaviors. Although many people may be concerned about their health, weight, or appearance from time to time, some people become fixated or obsessed with weight loss, body weight or shape, and controlling their food intake. These may be signs of an eating disorder.

Eating disorders are not a choice. These disorders can affect a person’s physical and mental health. In some cases, they can be life-threatening. With treatment, however, people can recover completely from eating disorders.

Who is at risk for eating disorders?

Eating disorders can affect people of all ages, racial/ethnic backgrounds, body weights, and genders. Although eating disorders often appear during the teen years or young adulthood, they may also develop during childhood or later in life (40 years and older).

Remember: People with eating disorders may appear healthy, yet be extremely ill.

The exact cause of eating disorders is not fully understood, but research suggests a combination of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors can raise a person’s risk.

What are the common types of eating disorders?

Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder, and avoidant restrictive food intake disorder. Each of these disorders is associated with different but sometimes overlapping symptoms. People exhibiting any combination of these symptoms may have an eating disorder and should be evaluated by a health care provider.

What is anorexia nervosa?

Anorexia nervosa is a condition where people avoid food, severely restrict food, or eat very small quantities of only certain foods. They also may weigh themselves repeatedly. Even when dangerously underweight, they may see themselves as overweight.

There are two subtypes of anorexia nervosa: a restrictive subtype and a binge-purge subtype.

Restrictive: People with the restrictive subtype of anorexia nervosa severely limit the amount and type of food they consume.

Binge-Purge: People with the binge-purge subtype of anorexia nervosa also greatly restrict the amount and type of food they consume. In addition, they may have binge-eating and purging episodes—eating large amounts of food in a short time followed by vomiting or using laxatives or diuretics to get rid of what was consumed.

Symptoms of anorexia nervosa include:

- Extremely restricted eating and/or intensive and excessive exercise

- Extreme thinness (emaciation)

- A relentless pursuit of thinness and unwillingness to maintain a normal or healthy weight

- Intense fear of gaining weight

- Distorted body or self-image that is heavily influenced by perceptions of body weight and shape

- Denial of the seriousness of low body weight

Over time, anorexia nervosa can lead to numerous serious health consequences, including:

- Thinning of the bones (osteopenia or osteoporosis)

- Mild anemia

- Muscle wasting and weakness

- Brittle hair and nails

- Dry and yellowish skin

- Growth of fine hair all over the body (lanugo)

- Severe constipation

- Low blood pressure

- Slowed breathing and pulse

- Damage to the structure and function of the heart

- Drop in internal body temperature, causing a person to feel cold all the time

- Lethargy, sluggishness, or feeling tired all the time

- Infertility

- Brain damage

- Multiple organ failure

Anorexia nervosa can be fatal. It has an extremely high death (mortality) rate compared with other mental disorders. People with anorexia are at risk of dying from medical complications associated with starvation. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for people diagnosed with anorexia nervosa.

It has an extremely high death (mortality) rate compared with other mental disorders. People with anorexia are at risk of dying from medical complications associated with starvation. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for people diagnosed with anorexia nervosa.

If you or someone you know is in immediate distress or is thinking about hurting themselves, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline toll-free at 1-800-273-TALK (8255). You also can text the Crisis Text Line (HELLO to 741741) or use the Lifeline Chat on the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline website. If you suspect a medical emergency, seek medical attention or call 911 immediately.

What is bulimia nervosa?

Bulimia nervosa is a condition where people have recurrent episodes of eating unusually large amounts of food and feeling a lack of control over their eating. This binge eating is followed by behaviors that compensate for the overeating to prevent weight gain, such as forced vomiting, excessive use of laxatives or diuretics, fasting, excessive exercise, or a combination of these behaviors. Unlike those with anorexia nervosa, people with bulimia nervosa may maintain a normal weight or be overweight.

Unlike those with anorexia nervosa, people with bulimia nervosa may maintain a normal weight or be overweight.

Symptoms and health consequences of bulimia nervosa include:

- Chronically inflamed and sore throat

- Swollen salivary glands in the neck and jaw area

- Worn tooth enamel and increasingly sensitive and decaying teeth from exposure to stomach acid when vomiting

- Acid reflux disorder and other gastrointestinal problems

- Intestinal distress and irritation from laxative abuse

- Severe dehydration from purging

- Electrolyte imbalance (too low or too high levels of sodium, calcium, potassium, and other minerals), which can lead to stroke or heart attack

What is binge-eating disorder?

Binge-eating disorder is a condition where people lose control of their eating and have reoccurring episodes of eating unusually large amounts of food. Unlike bulimia nervosa, periods of binge eating are not followed by purging, excessive exercise, or fasting. As a result, people with binge-eating disorder are often overweight or obese.

As a result, people with binge-eating disorder are often overweight or obese.

Symptoms of binge-eating disorder include:

- Eating unusually large amounts of food in a short amount of time, for example, within two hours

- Eating rapidly during binge episodes

- Eating even when full or not hungry

- Eating until uncomfortably full

- Eating alone or in secret to avoid embarrassment

- Feeling distressed, ashamed, or guilty about eating

- Frequently dieting, possibly without weight loss

What is avoidant restrictive food intake disorder?

Avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), previously known as selective eating disorder, is a condition where people limit the amount or type of food eaten. Unlike anorexia nervosa, people with ARFID do not have a distorted body image or extreme fear of gaining weight. ARFID is most common in middle childhood and usually has an earlier onset than other eating disorders. Many children go through phases of picky eating, but a child with ARFID does not eat enough calories to grow and develop properly, and an adult with ARFID does not eat enough calories to maintain basic body function.

Many children go through phases of picky eating, but a child with ARFID does not eat enough calories to grow and develop properly, and an adult with ARFID does not eat enough calories to maintain basic body function.

Symptoms of ARFID include:

- Dramatic restriction of types or amount of food eaten

- Lack of appetite or interest in food

- Dramatic weight loss

- Upset stomach, abdominal pain, or other gastrointestinal issues with no other known cause

- Limited range of preferred foods that becomes even more limited (“picky eating” that gets progressively worse)

How are eating disorders treated?

Eating disorders can be treated successfully. Early detection and treatment are important for a full recovery. People with eating disorders are at higher risk for suicide and medical complications.

A person’s family can play a crucial role in treatment. Family members can encourage the person with eating or body image issues to seek help. They also can provide support during treatment and can be a great ally to both the individual and the health care provider. Research suggests that incorporating the family into treatment for eating disorders can improve treatment outcomes, particularly for adolescents.

They also can provide support during treatment and can be a great ally to both the individual and the health care provider. Research suggests that incorporating the family into treatment for eating disorders can improve treatment outcomes, particularly for adolescents.

Treatment plans for eating disorders include psychotherapy, medical care and monitoring, nutritional counseling, medications, or a combination of these approaches. Typical treatment goals include:

- Restoring adequate nutrition

- Bringing weight to a healthy level

- Reducing excessive exercise

- Stopping binge-purge and binge-eating behaviors

People with eating disorders also may have other mental disorders (such as depression or anxiety) or problems with substance use. It’s critical to treat any co-occurring conditions as part of the treatment plan.

Specific forms of psychotherapy (“talk therapy”) and cognitive-behavioral approaches can treat certain eating disorders effectively. For general information about psychotherapies, visit the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) psychotherapies webpage.

For general information about psychotherapies, visit the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) psychotherapies webpage.

Research also suggests that medications may help treat some eating disorders and co-occurring anxiety or depression related to eating disorders. Information about medications changes frequently, so talk to your health care provider. Visit the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) website for the latest warnings, patient medication guides, and FDA-approved medications.

Where can I find help?

If you're unsure where to get help, your health care provider is a good place to start. Your health care provider can refer you to a qualified mental health professional, such as a psychiatrist or psychologist, who has experience treating eating disorders.

You can learn more about getting help and finding a health care provider on NIMH's Help for Mental Illnesses webpage. If you need help identifying a provider in your area, call the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Treatment Referral Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357). You also can search SAMHSA’s online Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator, which lists facilities and programs that provide mental health services.

You also can search SAMHSA’s online Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator, which lists facilities and programs that provide mental health services.

For tips on talking with your health care provider about your mental health, read NIMH’s fact sheet, Taking Control of Your Mental Health: Tips for Talking With Your Health Care Provider.

For additional resources, visit the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality website.

Are there clinical trials studying eating disorders?

NIMH supports a wide range of research, including clinical trials that look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat diseases and conditions, including eating disorders. Although individuals may benefit from being part of a clinical trial, participants should be aware that the primary purpose of a clinical trial is to gain new scientific knowledge so that others may be better helped in the future.

Researchers at NIMH and around the country conduct clinical trials with patients and healthy volunteers. Talk to your health care provider about clinical trials, their benefits and risks, and whether one is right for you. For more information about clinical research and how to find clinical trials being conducted around the country, visit NIMH's clinical trials webpage.

Talk to your health care provider about clinical trials, their benefits and risks, and whether one is right for you. For more information about clinical research and how to find clinical trials being conducted around the country, visit NIMH's clinical trials webpage.

Reprints

This publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without permission from NIMH. Citation of NIMH as a source is appreciated. To learn more about using NIMH publications, please contact the NIMH Information Resource Center at 1-866 615 6464, email [email protected], or refer to NIMH’s reprint guidelines.

For More Information

MedlinePlus (National Library of Medicine) (en español)

ClinicalTrials.gov (en español)

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

National Institutes of Health

NIH Publication No. 21-MH-4901

Revised 2021

Overview – Eating disorders - NHS

An eating disorder is a mental health condition where you use the control of food to cope with feelings and other situations.

Unhealthy eating behaviours may include eating too much or too little or worrying about your weight or body shape.

Anyone can get an eating disorder, but teenagers between 13 and 17 are mostly affected.

With treatment, most people can recover from an eating disorder.

Types of eating disorders

The most common eating disorders are:

- anorexia nervosa – trying to control your weight by not eating enough food, exercising too much, or doing both

- bulimia – losing control over how much you eat and then taking drastic action to not put on weight

- binge eating disorder (BED) – eating large portions of food until you feel uncomfortably full

Other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED)

A person may have an OSFED if their symptoms do not exactly fit the expected symptoms for any specific eating disorders.

OSFED is the most common eating disorder.

Find out more about OSFED on the Beat website

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID)

ARFID is when someone avoids certain foods, limits how much they eat or does both.

Beliefs about weight or body shape are not reasons why people develop ARFID.

Possible reasons for ARFID include:

- negative feelings over the smell, taste or texture of certain foods

- a response to a past experience with food that was upsetting, for example, choking or being sick after eating something

- not feeling hungry or just a lack of interest in eating

Find out more about ARFID on the Beat website

Check if you have an eating disorder

If you or people around you are worried that you have an unhealthy relationship with food, you could have an eating disorder.

Symptoms of eating disorders include:

- spending a lot of time worrying about your weight and body shape

- avoiding socialising when you think food will be involved

- eating very little food

- making yourself sick or taking laxatives after you eat

- exercising too much

- having very strict habits or routines around food

- changes in your mood such as being withdrawn, anxious or depressed

You may also notice physical signs, including:

- feeling cold, tired or dizzy

- pains, tingling or numbness in your arms and legs (poor circulation)

- feeling your heart racing, fainting or feeling faint

- problems with your digestion, such as bloating, constipation or diarrhoea

- your weight being very high or very low for someone of your age and height

- not getting your period or other delayed signs of puberty

You can read more about the symptoms of:

- anorexia

- bulimia

- binge eating disorder

Warning signs of an eating disorder in someone else

It can be very difficult to identify that a loved one or friend has developed an eating disorder.

Warning signs to look out for include:

- dramatic weight loss

- lying about how much they've eaten, when they've eaten, or their weight

- eating a lot of food very fast

- going to the bathroom a lot after eating

- exercising a lot

- avoiding eating with others

- cutting food into small pieces or eating very slowly

- wearing loose or baggy clothes to hide their weight loss

Getting help for an eating disorder

If you think you may have an eating disorder, see a GP as soon as you can.

A GP will ask about your eating habits and how you're feeling, plus check your overall health and weight.

They may refer you to an eating disorder specialist or team of specialists.

It can be very hard to admit you have a problem and ask for help. It may make things easier if you bring a friend or loved one with you to your appointment.

You can also talk in confidence to an adviser from eating disorders charity Beat by calling their adult helpline on 0808 801 0677 or youth helpline on 0808 801 0711.

Getting help for someone else

It can be difficult to know what to do if you're worried that someone has an eating disorder.

They may not realise they have an eating disorder. They may also deny it, or be secretive and defensive about their eating or weight.

Let them know you're worried about them and encourage them to see a GP. You could offer to go along with them.

Read more about talking to your child about eating disorders and supporting someone with an eating disorder.

The eating disorder charity Beat also has information on:

- Beat: what to do if you're worried about a friend or family member

- Beat: what to do if you're worried about a colleague

Treatment for eating disorders

You can recover from an eating disorder, but it may take time and recovery will be different for everyone.

If you're referred to an eating disorder specialist or team of specialists, they'll be responsible for your care.

They should talk to you about the support you might need, such as for other conditions you have, and include this in your treatment plan.

Your treatment will depend on the type of eating disorder you have, but usually includes a talking therapy.

You may also need regular health checks if your eating disorder is having an impact on your physical health.

Your treatment may also involve working through a guided self-help programme if you have bulimia or binge eating disorder.

Most people will be offered individual therapy, but those with binge eating disorder may be offered group therapy.

Read more about the different treatments for:

- anorexia

- bulimia

- binge eating disorder

Treatment for other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED) will depend on the type of eating disorder your symptoms are most like.

For example, if your symptoms are most like anorexia, your treatment will be similar to the treatment for anorexia.

What causes eating disorders?

We do not know exactly what causes eating disorders.

You may be more likely to get an eating disorder if:

- you or a member of your family has a history of eating disorders, depression, or alcohol or drug misuse

- you've been criticised for your eating habits, body shape or weight

- you're really worried about being slim, particularly if you also feel pressure from society or your job, for example, ballet dancers, models or athletes

- you have anxiety, low self-esteem, an obsessive personality or are a perfectionist

- you've been sexually abused

Find out more

- Beat: eating disorders information and support

- Health for Teens: information and advice about eating disorders

Reasons for vegetarianism | Tervisliku toitumise informatsioon

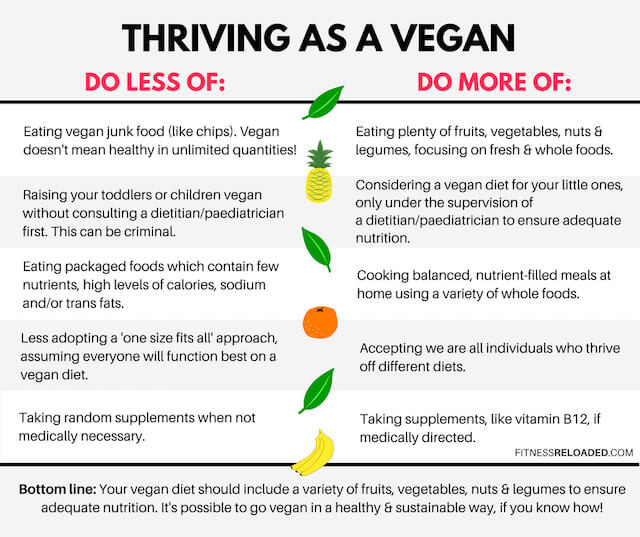

There are three main reasons for avoiding animal products: ethics, health and the environment.

Ethical reasons

Ethical reasons are based on the understanding that animals are living beings who experience pain, fear, joy and pleasure and who want to live and avoid suffering. Therefore, it is unjustified to inflict undue suffering on them. Vegans believe that the consumption of animals as food is not currently vital for humans to survive and maintain good health, and their choice is an example of this.

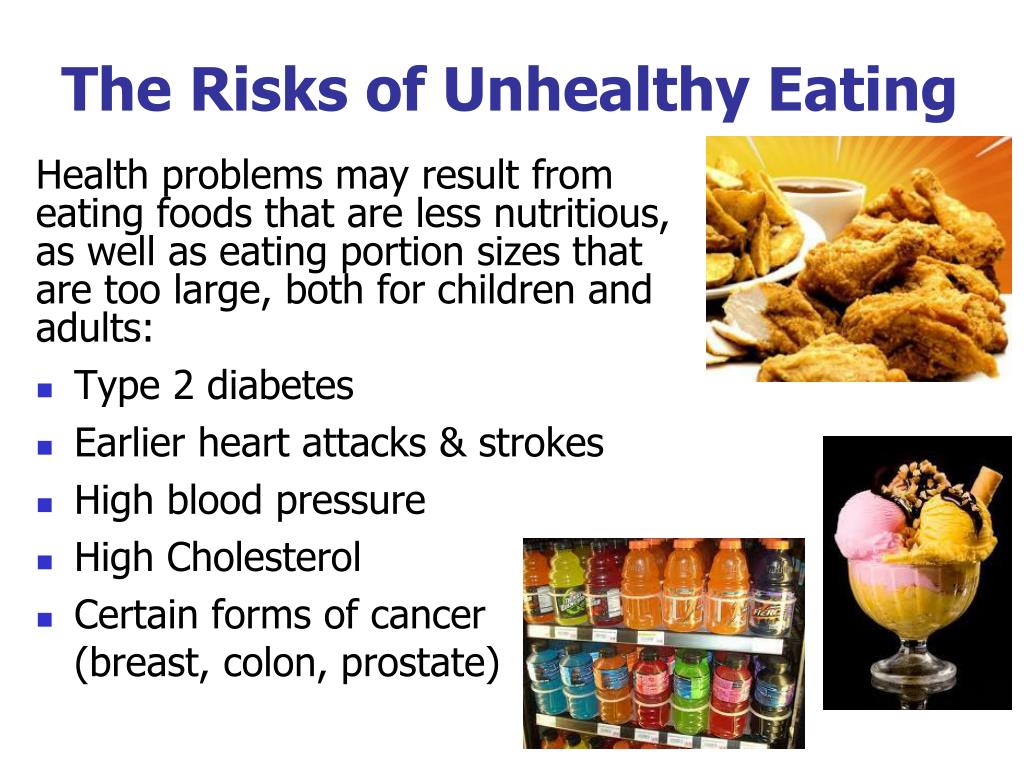

Health reasons

Currently, there is not enough evidence to support a clear benefit of vegetarianism in reducing the risk of chronic disease compared to a balanced and varied mixed diet. Thus, from the point of view of health, it is impossible to unequivocally state that one is better than the other. However, when vegetarians are compared with omnivores whose eating habits do not meet dietary guidelines, the latter are more likely to have high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol, and diabetes, and more overweight and obese people. Vegetarianism may also reduce the risk of cancer and, in men, the risk of death from cardiovascular disease.

Vegetarianism may also reduce the risk of cancer and, in men, the risk of death from cardiovascular disease.

Protecting the environment

The production of food for human consumption causes significant damage to the environment, such as deforestation, soil erosion, lack of fresh water, air and water pollution, climate change and loss of biodiversity.

The environmental impact of food production and consumption (eg greenhouse gases and land use) is highly dependent on the dietary habits of consumers. In general, the production of animal products (both meat and milk) requires more resources and creates more greenhouse gases than the production of plant products.

When studying the impact of food on climate, it was found that a vegetarian diet with eggs and milk reduces the impact of food on the climate by up to a quarter, and a vegan diet by up to half. At the same time, the impact of a mixed diet on the climate is reduced by almost a quarter, if each of the main food groups in the food pyramid is selected for products with a lower environmental impact.

Because the impact on the environment is made up of many interconnected aspects, completely eliminating animal products is not the only or best way to reduce your ecological footprint.

You can make a significant contribution by reducing your consumption of meat, especially meat products, and increasing your consumption of cereals, as well as fruits, vegetables and berries. Replacing red meat (beef, pork, lamb, goat) with other animal products with a more moderate environmental impact (eggs, milk, fish) will also help reduce environmental impact.

For a variety of protein sources, products that do not grow in Estonia are often used. This in turn leads to additional transportation costs, environmental pollution and other problems. Therefore, even vegetarians are encouraged to monitor the environmental impact of their food and prioritize local protein sources and local and seasonal fruits and vegetables.

Find out more about sustainable food.

Who are Vegetarians, Vegans and Reductians? – Zira.

uz

uz How vegetarians differ from vegans, how such a diet affects health, we tell in this article.

In the realities of our region and our eating habits, it is very difficult to imagine people who have given up eating meat. However, many of you have heard of vegetarianism. We decided to talk about the different categories of nutrition associated with the rejection of food of animal origin, how such diets affect health and what is the difference.

Vegetarianism

As defined by the Vegetarian Society, a vegetarian shall not eat foods that consist of any part of the body of a living or dead animal, poultry, fish, shellfish, insects, slaughter by-products, or any food made from them.

"A vegetarian is a person whose diet consists of grains, legumes, nuts, seeds, vegetables, fruits, mushrooms, algae, yeast, and/or certain other foods that do not contain animal slaughter products."

There are various types of vegetarians :

- Lacto-ovo vegetarians eat both dairy products and eggs; this is the most common type of vegetarianism.

- Lacto-vegetarians eat dairy products but do not eat eggs. Lacto is derived from the Latin word for milk.

- Ovo-vegetarians ("ovo" - from the Latin for "egg") eat eggs, but not dairy products.

Those who do not eat poultry and game but eat fish are called pescatarians , those who sometimes refuse meat, flexetarians . Since pescatarians and flexetarians eat fish and meat, they are not considered as categories of vegetarianism, but are designated by such terms.

Conclusion: Vegetarianism is a way of life that involves the rejection of the products of the slaughter of any animals for food.

Vegan

Vegans do not eat dairy products, eggs, or any other products derived from animals other than meat.

Veganism is considered strict vegetarianism. Veganism, as defined by the Vegan Community, is a way of life that excludes as much as possible all forms of exploitation and cruelty to animals. Not only in terms of the food industry, but in any form. That is, a vegan does not use woolen clothing, cosmetics and medicines that are tested on animals.

Not only in terms of the food industry, but in any form. That is, a vegan does not use woolen clothing, cosmetics and medicines that are tested on animals.

The vegan diet excludes any food of animal origin. And this is not only meat, eggs and dairy products, this means you can not use gelatin, honey, cheese based on rennet, whey obtained from animals.

Conclusion: veganism is a lifestyle that aims to exclude the consumption of any products associated with the exploitation or cruelty to animals.

What is the difference between a vegan and a vegetarian?

Vegetarians and vegans often avoid animal products for similar reasons. The biggest difference lies in the extent to which they consider animal products acceptable.

For example, both vegans and vegetarians may exclude meat from their diets for health or environmental reasons. However, vegans prefer to avoid any animal by-products as they believe it has the greatest impact on their health and the environment.

Ethically, vegetarians are against killing animals for food, but consider it acceptable to consume animal by-products such as milk and eggs as long as the animals are kept in adequate conditions.

On the other hand, vegans believe that animals have a right to be free from human use, whether for food, clothing, cosmetics, science or entertainment. As such, they strive to eliminate all animal by-products, regardless of the conditions under which the animals were bred or housed.

The desire to avoid all forms of animal exploitation is why vegans choose to forego dairy and eggs, foods that many vegetarians can easily include in their diets.

Conclusion: Vegetarians and vegans differ in their conviction regarding the use of animals by humans. This is why some vegetarians may consume animal products while vegans do not.

Nutrition questions for vegetarians and vegans

Studies show that vegetarian and vegan diets are low in saturated fat and cholesterol. They are also high in vitamins, minerals, fiber and healthy plant compounds. What's more, both diets are high in nutrients, with plenty of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, seeds, and soy products.

They are also high in vitamins, minerals, fiber and healthy plant compounds. What's more, both diets are high in nutrients, with plenty of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, seeds, and soy products.

On the other hand, poorly planned vegan or vegetarian diets result in deficiencies in nutrients, especially iron, calcium, zinc, and vitamin D. Also, diets lacking animal products contain limited amounts of vitamin B12 and long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, levels of these nutrients are generally lower in vegans than in vegetarians.

Conclusion: Vegetarians and vegans generally consume similar levels of most nutrients. However, a poorly planned diet can lead to low intake of certain nutrients.

How does vegetarianism and veganism affect health?

Oddly enough, the scientific community has different points of view on vegetarianism and veganism in terms of the impact on human health. Below are different views on the essence of the issue.

According to a report from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and several scientific reviews, vegetarian and vegan diets can be considered appropriate for all life stages as long as the diet is well planned (Study 1, Study 2, Study 3, Study 4).

Insufficient intake of nutrients such as omega-3 fatty acids, calcium, and vitamins D and B12 can adversely affect various aspects of health, including mental and physical health (Study 5, Study 6, Study 7, Study 8).

Vegetarians and vegans may not be able to get enough of these nutrients due to their diet. However, studies show that vegetarians tend to consume slightly more calcium and vitamin B12 than vegans (Study 9, study 10).

Both vegetarians and vegans need to constantly monitor the amount of nutrients and form a diet based on their content in plant products.

Fortified foods and supplements may also be required, especially for nutrients such as iron, calcium, omega-3s, and vitamins D and B12.

Studies directly comparing vegetarian to vegan diets report that vegans have a lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and various cancers than vegetarians (study 11, study 12, study 13, study 14).

In addition, vegans have a lower body mass index than vegetarians and gain less weight with age.

However, most studies so far have been observational. This means that it is not possible to definitively say which aspect of the vegan diet is responsible for these effects, or confirm that diet is the sole determining factor.

Conclusion: A vegan diet may be superior to a vegetarian diet in terms of weight control and reduced risk of certain diseases. However, if not well planned, a vegan diet will lead to nutrient deficiencies.

Veganism

Veganism is more than an attitude to nutrition. While vegetarians and vegans may avoid animal products in their diets, this choice often goes beyond a particular diet. In practice, veganism is often considered an attitude towards animals.

So many vegans refuse to buy items of clothing containing silk, wool, leather or suede. What's more, many vegans are boycotting companies that test on animals and buy cosmetics that are free of animal by-products.

Those who share a vegan lifestyle also tend to avoid circuses, zoos, rodeos, horse races, and any other activity that uses animals for entertainment.

Finally, many environmentalists promote vegetarianism as one way to reduce the harmful effects on the Earth's resources and influence climate change (Article 1, Article 2, Article 3).

Conclusion: For many, veganism is not just a food habit, but a way of life. This explains why many vegans do not buy clothes, beauty products, or indulge in certain animal exploitation activities.

Reductianism

A new trend that advocates the humane treatment of animals is reductionism. The ideas of the movement were formed by Brian Kathman, co-founder of the movement and one of the authors of the New York Times. He also released a book, The Reducetarian Solution, detailing the concept.

Reductionism is a lifestyle that focuses on eating less meat, poultry, seafood, milk, and eggs, regardless of quality or motivation.

The idea is considered attractive because not everyone is ready to radically change the diet. However, it is perfectly possible to include vegans, vegetarians, and anyone who reduces the amount of animal products in their diet under the concept of reductionism.

According to the Vegan Society, there were more vegans in 2016 than 10 years ago. Over 1.2 million people in the UK are vegetarians. A YouGov poll found that 25% of people in the UK have reduced their meat intake. Despite this, many still hold on to the idea that eating less meat means eating nothing.

“The main premise of reducers is that vegans and vegetarians who have successfully reduced their consumption of animals are part of the same spectrum as people who are unhappy with factory farming,” says Kathman. “It’s specifically about moderation for omnivores.”

Most vegans and vegetarians are tolerant and balanced people who understand that we must be pragmatic about this. Changing something in the diet is the way to go.

According to the Reducers, not eating meat is an achievement. But eating it periodically is not a failure. You cannot "fail" or "relapse" if you want to do something for yourself. And you are not a hypocrite if you do everything possible to give up something completely.