Ptsd from childhood abuse

Childhood Abuse – PTSD UK

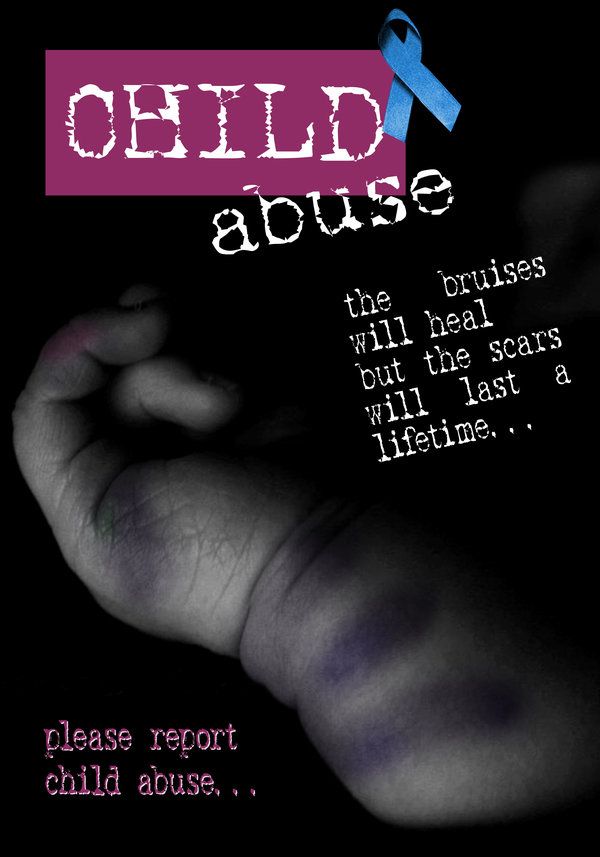

The relationship between childhood abuse and post-traumatic stress disorder is clear and indisputable. Even one deeply traumatic incident in your early years can have serious mental health repercussions.

However, what is not always fully appreciated, is the way abuse in childhood can cause PTSD and C-PTSD to appear in adulthood.

There is sometimes an assumption that with the right support and more positive experiences, a child can ‘put the abuse behind them’. When in fact, the imprint of the trauma can manifest in a myriad of different ways.

The individual may have symptoms that appear – or last for – many years after the abuse stops. Prolonged or repeated childhood abuse can also create complex PTSD (or C-PTSD).

This article provides insights on this highly sensitive topic and the way an abusive childhood can cause PTSD in adults.

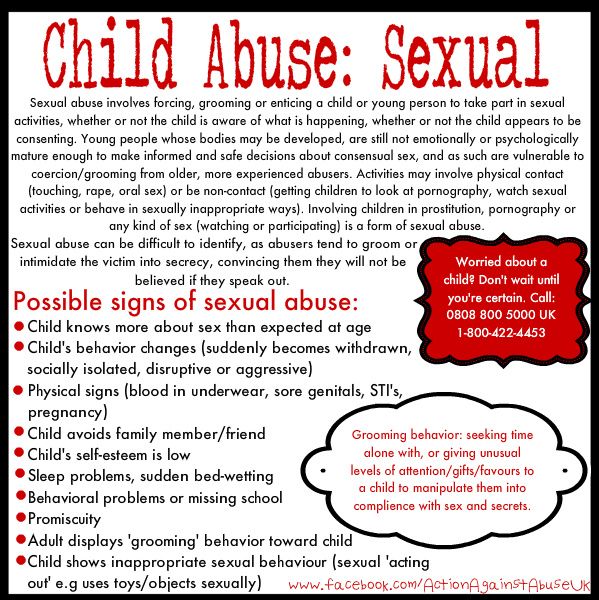

Understanding what’s meant by childhood abuse

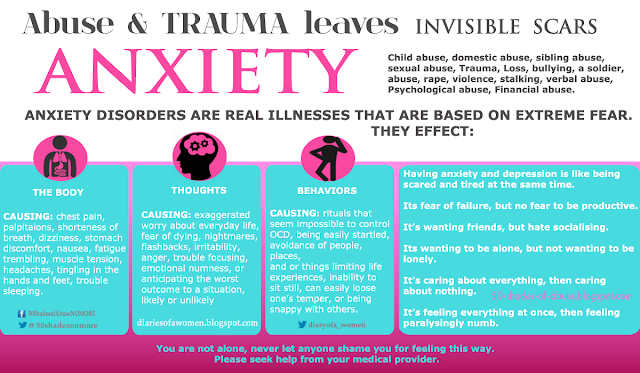

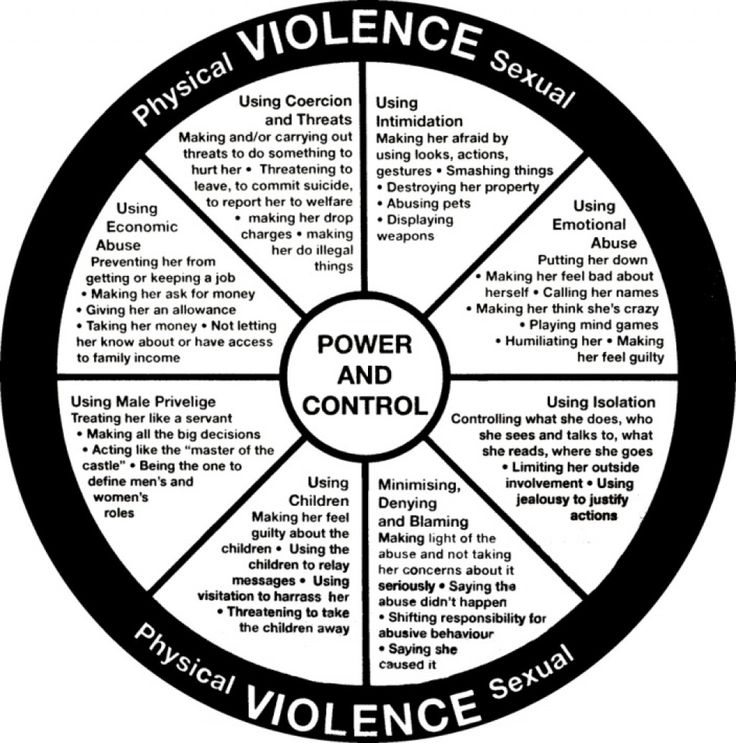

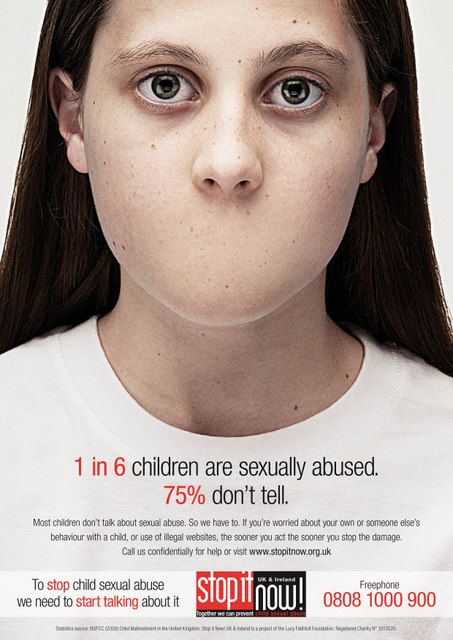

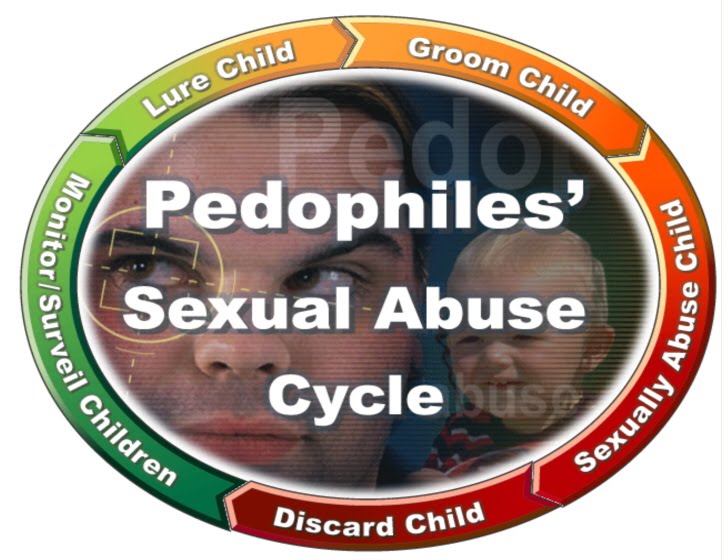

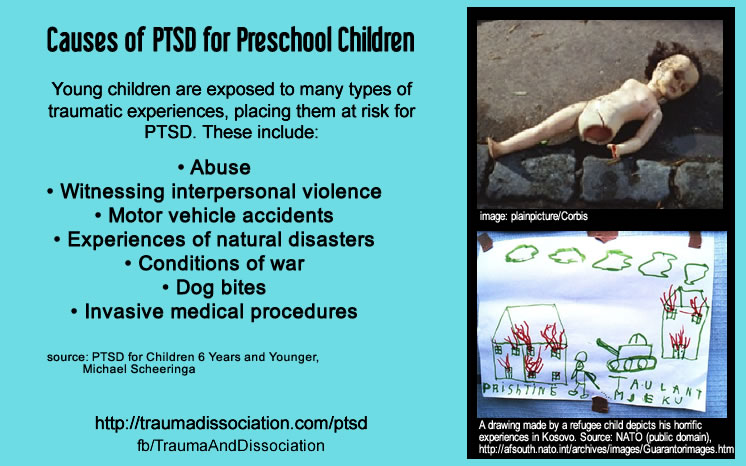

First, it needs to be clarified that the term ‘childhood abuse’ is being used as a collective term for diverse types of trauma; sexual and physical, but also emotional abuse and neglect.

Any of these can cause PTSD and C-PTSD. A caregiver who denies a child their basic needs to comfort, food and a safe living environment can create trauma just as damaging as physical blows or sexual contact.

In fact, there are bodies of opinion that suggest that emotional abuse from a caregiver can be particularly damaging and be even more likely to cause severe PTSD or C-PTSD.

A 2021 study into Child Abuse & Neglect found: “Emotional abuse (rather than any other type of maltreatment) was associated with more severe PTSD symptoms in all symptom clusters.”

How common is PTSD from an abusive childhood?

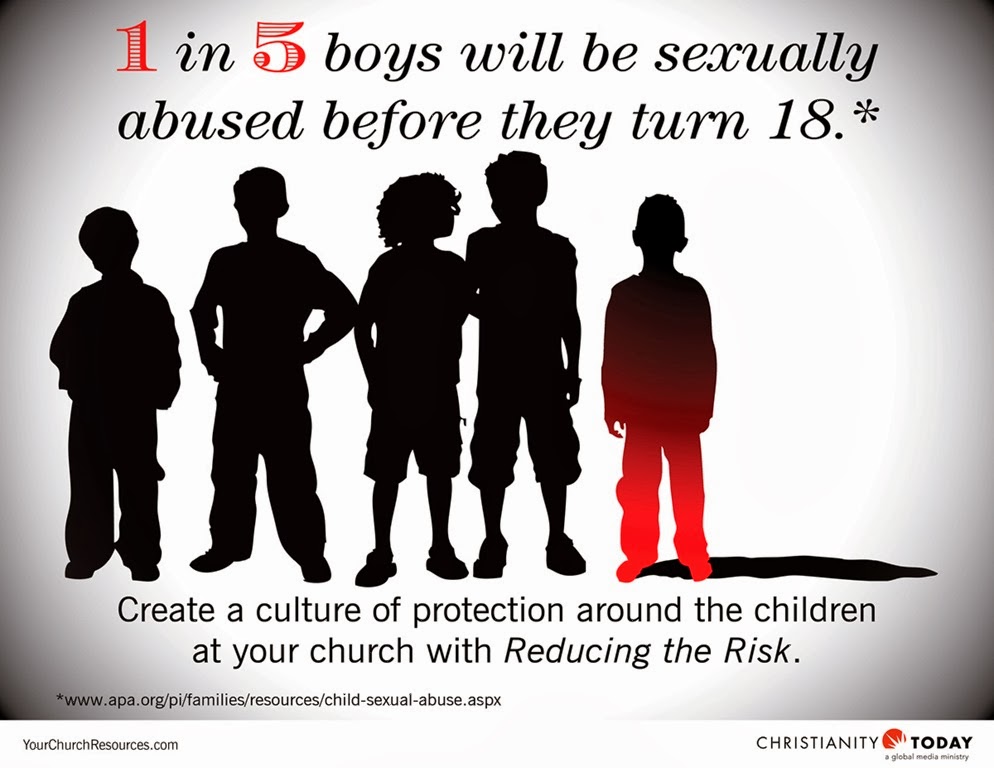

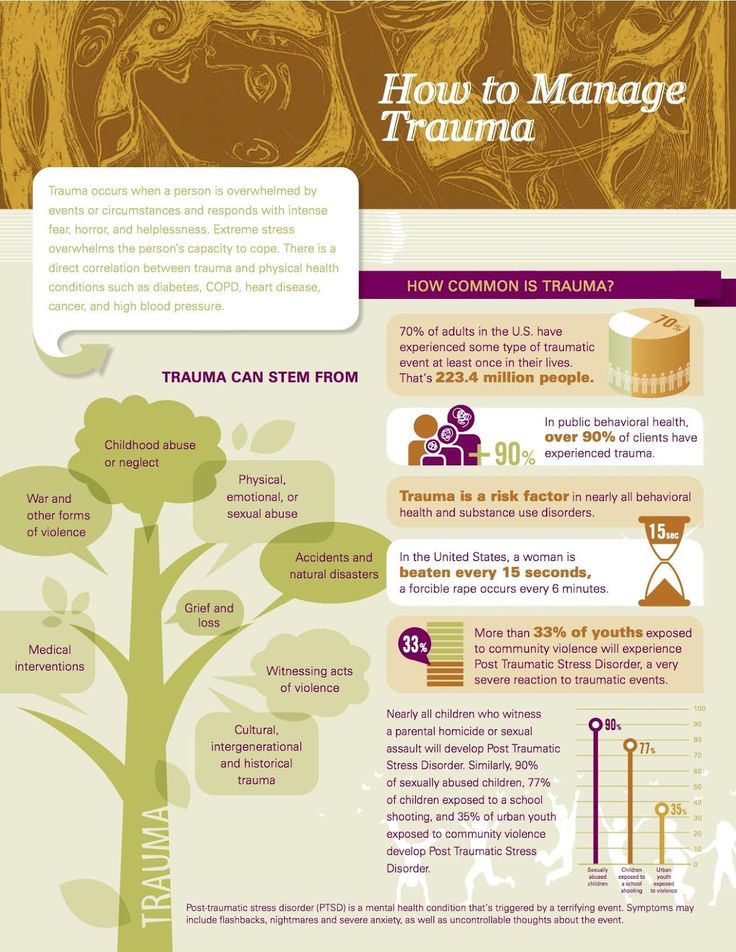

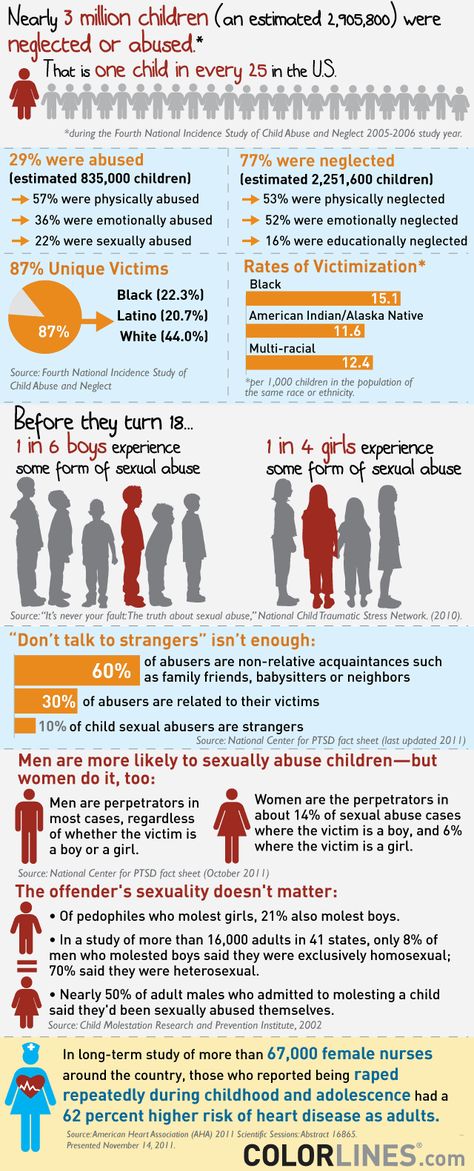

The likelihood of trauma in childhood is possibly more common than you would imagine.

The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services reported that over two-thirds of children experience one traumatic event by the time they are 16. This is not always abuse of course but includes witnessing acts of violence, accidents or deaths, and the sudden loss of a significant family member.

Accurate figures on child abuse in the UK are impossible to find, as so much of it goes unreported. In many cases, the child is unaware that they have been abused, particularly if abusive behaviours are commonplace in their lives.

According to a 1999 study into PTSD and child victimisation: “Slightly more than a third of the childhood victims of sexual abuse (37.5%), 32.7% of those physically abused, and 30.6% of victims of childhood neglect met DSM-III-R criteria for lifetime PTSD.”

How PTSD manifests in children

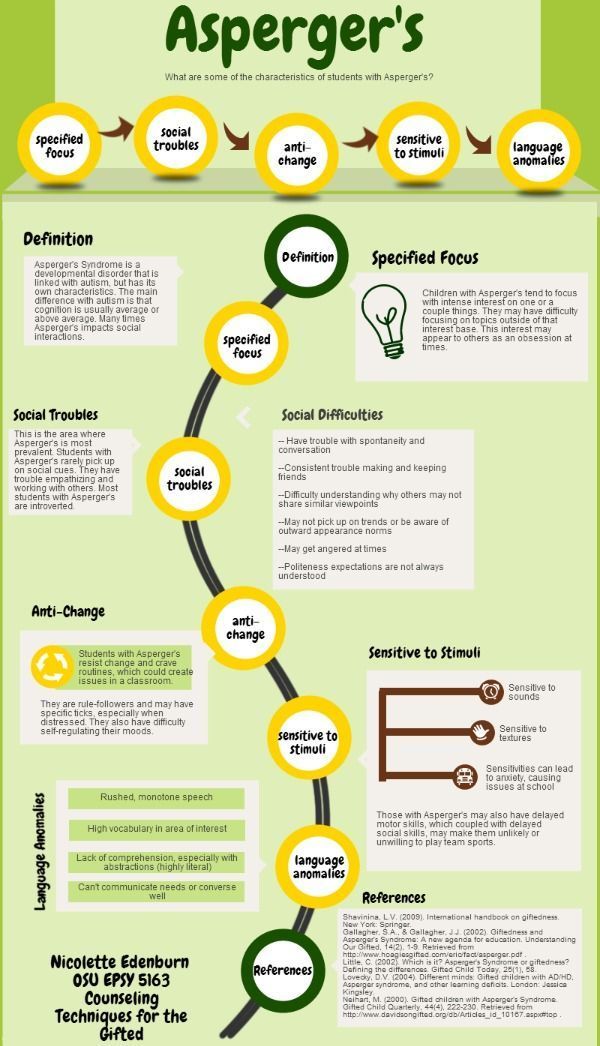

PTSD symptoms displayed by abused children and young people include learning difficulties, poor behaviour at school, depression and anxiety, aggression, risk-taking and criminal behaviours, emotional numbness, and a range of physical issues including poor sleep and headaches.

Diagnosing PTSD in children requires a professional mental health evaluation. Treatment plans would be similar to adults with post-traumatic stress, including Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, and counselling, as well as practical steps to make them feel safer and supported.

One of the important things to dismantle is the shame and guilt that can be interwoven with childhood abuse. Also, children don’t have as many cognitive resources to draw on as adults do. Leading them to possibly rationalise their traumatic experiences or display a “fawn’ response, seeking to please their abuser and win favour.

Family support plays an important role in helping children recover from PTSD. So, when a parent is responsible for the trauma, it makes recovery a more complex and longer-term process.

Childhood abuse and adult PTSD

Some of the effects of childhood abuse outlined above linger into adulthood or don’t even become apparent until later in life.

Children and young people who are abused can become emotionally numb to their trauma, or bury it deep in their psyche. The adaptive or protective mechanisms they use can ask the long-lasting damage.

Undiagnosed and untreated PTSD could make victims of abusive childhoods prone to self-harming, depression, substance abuse and anxiety. Or their symptoms could be difficulties in maintaining healthy relationships, trust issues, poor self-confidence or disassociation (being emotionally distant or shut-down).

Or their symptoms could be difficulties in maintaining healthy relationships, trust issues, poor self-confidence or disassociation (being emotionally distant or shut-down).

The attachment issues associated with the abuse at an early age are categorised as:

- Dismissive-Avoidant Attachment – being highly independent, self-sufficient and focused on avoiding being rejected (as they were in childhood).

- Fearful-Avoidant Attachment – avoiding intimacy and closeness, as they associate these with their childhood abuse and don’t want to give someone ‘power’ to hurt them.

- Anxious-Preoccupied Attachment – someone clingy and needy, who demands constant validation to balance out inherent feelings of insecurity and ‘not being enough’.

Some people go for years without clear symptoms that their childhood abuse is affecting them but an event or experience triggers mental health issues

. For some, this includes the birth of their own child, which reawakens their own fractured relationship with a caregiver. There is also evidence that pregnancy and childbirth can stimulate “risk behaviours” due to “sudden memories of sexual abuse situations.”

For some, this includes the birth of their own child, which reawakens their own fractured relationship with a caregiver. There is also evidence that pregnancy and childbirth can stimulate “risk behaviours” due to “sudden memories of sexual abuse situations.”

The brain, abuse and complex PTSD

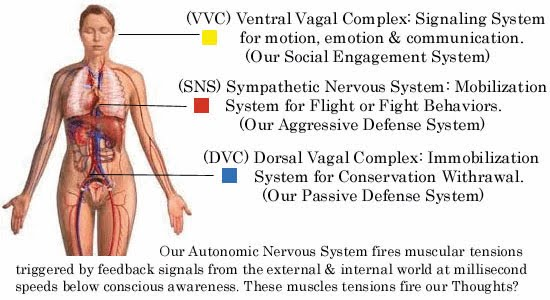

The way PTSD can linger into adulthood – or be diagnosed many years after childhood abuse – is partially due to the way trauma causes physical changes to the human brain. Neglect and all other forms of childhood abuse, occur at key stages in the development of the brain, altering the formation and function of the amygdala, hippocampus and prefrontal cortex.

Once a diagnosis of PTSD or C-PTSD is received, the individual can receive treatment that includes overcoming both the physiological and psychological effects.

The important thing is that you need to accept that your earliest experiences in life can – and do – lead to serious mental disorders in adults.

As one researcher into the neurobiological effects of childhood mistreatment said: “Our brains are sculpted by our early experiences. Maltreatment is a chisel that shapes a brain to contend with strife but at the cost of deep, enduring wounds. Childhood abuse isn’t something you ‘get over.’

Maltreatment is a chisel that shapes a brain to contend with strife but at the cost of deep, enduring wounds. Childhood abuse isn’t something you ‘get over.’

NICE guidance updated in 2018 recommends the use of trauma focused psychological treatments for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in adults, specifically the use of Eye Movement Desensitisation Reprocessing (EMDR) and trauma focused cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT).

Please remember, these aren’t meant to be medical recommendations. Be sure to work with a professional to find the best methods for you.

For direct support for Child Abuse, please see the resources below:

- Help for Adult Victims of Child Abuse (HAVOCA) provide information and support for adults who have experienced any type of childhood abuse, run by survivors. havoca.org

- The National Association for People Abused in Childhood (NAPAC) supports adult survivors of any form of childhood abuse.

Offers a helpline, email support and local services. Call them on 0808 801 0331 napac.org.uk

Offers a helpline, email support and local services. Call them on 0808 801 0331 napac.org.uk - Childline provides support for children and young people in the UK, including a free helpline and 1-2-1 online chats with counsellors. You can call them on 0800 1111 childline.org.uk

- YoungMinds are committed to improving the mental health of babies, children and young people, including support for parents and carers. Call the parents helpline on 0808 802 5544 or Young People can contact the crisis messenger by texting the letter YM to 85258

- Respond provide services for people with a learning disability, autism or both, who have experienced abuse or trauma. Call them on 0207 383 0700 respond.org.uk

Posttraumatic stress disorder in abused and neglected children grown up

Save citation to file

Format: Summary (text)PubMedPMIDAbstract (text)CSV

Add to Collections

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Name your collection:

Name must be less than 100 characters

Choose a collection:

Unable to load your collection due to an error

Please try again

Add to My Bibliography

- My Bibliography

Unable to load your delegates due to an error

Please try again

Your saved search

Name of saved search:

Search terms:

Test search terms

Email: (change)

Which day? The first SundayThe first MondayThe first TuesdayThe first WednesdayThe first ThursdayThe first FridayThe first SaturdayThe first dayThe first weekday

Which day? SundayMondayTuesdayWednesdayThursdayFridaySaturday

Report format: SummarySummary (text)AbstractAbstract (text)PubMed

Send at most: 1 item5 items10 items20 items50 items100 items200 items

Send even when there aren't any new results

Optional text in email:

Create a file for external citation management software

Full text links

Atypon

Full text links

. 1999 Aug;156(8):1223-9.

1999 Aug;156(8):1223-9.

doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1223.

C S Widom 1

Affiliations

Affiliation

- 1 School of Criminal Justice, University at Albany, NY 12222, USA.

- PMID: 10450264

- DOI: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1223

C S Widom. Am J Psychiatry. 1999 Aug.

. 1999 Aug;156(8):1223-9.

doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1223.

Author

C S Widom 1

Affiliation

- 1 School of Criminal Justice, University at Albany, NY 12222, USA.

- PMID: 10450264

- DOI: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1223

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to describe the extent to which childhood abuse and neglect increase a person's risk for subsequent posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and to determine whether the relationship to PTSD persists despite controls for family, individual, and lifestyle characteristics associated with both childhood victimization and PTSD.

Method: Victims of substantiated child abuse and neglect from 1967 to 1971 in a Midwestern metropolitan county area were matched on the basis of age, race, sex, and approximate family socioeconomic class with a group of nonabused and nonneglected children and followed prospectively into young adulthood. Subjects (N = 1,196) were located and administered a 2-hour interview that included the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule to assess PTSD.

Subjects (N = 1,196) were located and administered a 2-hour interview that included the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule to assess PTSD.

Results: Childhood victimization was associated with increased risk for lifetime and current PTSD. Slightly more than a third of the childhood victims of sexual abuse (37.5%), 32.7% of those physically abused, and 30.6% of victims of childhood neglect met DSM-III-R criteria for lifetime PTSD. The relationship between childhood victimization and number of PTSD symptoms persisted despite the introduction of covariates associated with risk for both.

Conclusions: Victims of child abuse (sexual and physical) and neglect are at increased risk for developing PTSD, but childhood victimization is not a sufficient condition. Family, individual, and lifestyle variables also place individuals at risk and contribute to the symptoms of PTSD.

Similar articles

-

A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up.

Widom CS, DuMont K, Czaja SJ. Widom CS, et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007 Jan;64(1):49-56. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.49. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007. PMID: 17199054

-

Childhood victimization and crime victimization.

McIntyre JK, Widom CS. McIntyre JK, et al. J Interpers Violence. 2011 Mar;26(4):640-63. doi: 10.1177/0886260510365868. Epub 2010 May 26. J Interpers Violence. 2011. PMID: 20505112

-

Antisocial personality disorder in abused and neglected children grown up.

Luntz BK, Widom CS. Luntz BK, et al. Am J Psychiatry. 1994 May;151(5):670-4. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.5.670. Am J Psychiatry. 1994. PMID: 8166307

-

Gender differences in the prevalence of childhood sexual abuse and in the development of pediatric PTSD.

Walker JL, Carey PD, Mohr N, Stein DJ, Seedat S. Walker JL, et al. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2004 Apr;7(2):111-21. doi: 10.1007/s00737-003-0039-z. Epub 2004 Jan 8. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2004. PMID: 15083346 Review.

-

The link between substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder in women. A research review.

Najavits LM, Weiss RD, Shaw SR. Najavits LM, et al. Am J Addict. 1997 Fall;6(4):273-83. Am J Addict. 1997. PMID: 9398925 Review.

See all similar articles

Cited by

-

Individual and Social Risk and Protective Factors as Predictors of Trajectories of Post-traumatic Stress Symptoms in Adolescents.

Herd T, Haag AC, Selin C, Palmer L, S S, Strong-Jones S, Jackson Y, Bensman HE, Noll JG. Herd T, et al. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol. 2022 Sep 21. doi: 10.1007/s10802-022-00960-y. Online ahead of print. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol. 2022. PMID: 36129567

-

A Public Health Perspective of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Al Jowf GI, Ahmed ZT, An N, Reijnders RA, Ambrosino E, Rutten BPF, de Nijs L, Eijssen LMT. Al Jowf GI, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 May 26;19(11):6474. doi: 10.3390/ijerph29116474.

Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022. PMID: 35682057 Free PMC article. Review.

Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022. PMID: 35682057 Free PMC article. Review. -

Risk Factors for Moral Injury Among Canadian Armed Forces Personnel.

Easterbrook B, Plouffe RA, Houle SA, Liu A, McKinnon MC, Ashbaugh AR, Mota N, Afifi TO, Enns MW, Richardson JD, Nazarov A. Easterbrook B, et al. Front Psychiatry. 2022 May 11;13:892320. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.892320. eCollection 2022. Front Psychiatry. 2022. PMID: 35633790 Free PMC article.

-

Evaluating the challenges and reproducibility of studies investigating DNA methylation signatures of psychological stress.

Zhang Y, Liu C. Zhang Y, et al. Epigenomics. 2022 Apr;14(7):405-421. doi: 10.2217/epi-2021-0190. Epub 2022 Feb 16. Epigenomics. 2022.

PMID: 35170363 Review.

PMID: 35170363 Review. -

Post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and the associated factors among children and adolescents with a history of maltreatment in Uganda.

Ainamani HE, Weierstall-Pust R, Bahati R, Otwine A, Tumwesigire S, Rukundo GZ. Ainamani HE, et al. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2022 Jan 10;13(1):2007730. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2021.2007730. eCollection 2022. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2022. PMID: 35028113 Free PMC article.

See all "Cited by" articles

Publication types

MeSH terms

Grant support

- MH-49467/MH/NIMH NIH HHS/United States

Full text links

Atypon

Cite

Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Send To

The effects of bullying are lifelong

Childhood abuse can be seen as a form of "captivity", prolonged bullying where the child sees no way to escape.

Author: Shahida Arabi

Abbreviated translation: Anna Skavitina, psychotherapist

“Complex trauma bills for a lifetime. Many abused children cling to the hope that growing up will bring them liberation. But the personality, formed in a situation of coercive control, is poorly adapted to adult life. The trauma survivor is left with fundamental problems with trust, autonomy, and initiative. The challenge of early adulthood through independence and intimacy faces significant challenges in developing self-care, cognition and memory, identity, and the ability to form stable relationships. They are still prisoners of their childhood; trying to create a new life, they encounter trauma again.” – Judith Herman, “Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence – From Domestic Violence to Political Terror”

Survivors of complex trauma face a dilemma that few people understand: they are forced to confront new stressors while simultaneously trying to eliminate triggers from the past. It takes courage, support, and time to overcome these layers of trauma. The path to healing for a person who has experienced complex trauma, which has several sources, is multifaceted. The everyday reality of a person with complex trauma is filled with small horrors embedded in larger cracks in the zone of psychological warfare that is their psyche. Survivors of violence and other traumas face a double challenge: not only are they oppressed by their peers, but they are also often oppressed by family members, authority figures, and other life circumstances. When violence is combined with other microaggressions or violent life events, the trauma undoubtedly has a greater impact. What happens when a child is bullied both at school and at home, where it should be safe? What effects persist and remain far beyond childhood, when not only peers but also parents terrorize the victim? What about the impact of chronic severe abuse - a form of bullying that occurs over many years throughout a child's school life - that is not short term?

It takes courage, support, and time to overcome these layers of trauma. The path to healing for a person who has experienced complex trauma, which has several sources, is multifaceted. The everyday reality of a person with complex trauma is filled with small horrors embedded in larger cracks in the zone of psychological warfare that is their psyche. Survivors of violence and other traumas face a double challenge: not only are they oppressed by their peers, but they are also often oppressed by family members, authority figures, and other life circumstances. When violence is combined with other microaggressions or violent life events, the trauma undoubtedly has a greater impact. What happens when a child is bullied both at school and at home, where it should be safe? What effects persist and remain far beyond childhood, when not only peers but also parents terrorize the victim? What about the impact of chronic severe abuse - a form of bullying that occurs over many years throughout a child's school life - that is not short term?

Consequences of bullying last a lifetime

When a person has experienced multiple incidents of abuse during their lifetime, including but not limited to bullying, emotional neglect, or parental abuse, witnessed domestic violence and/or even sexual abuse From early childhood, the simultaneous exposure to several factors literally rewires the brain, disrupting identity, self-image, and interpersonal relationships.

According to Bessel van der Kolk, trauma causes the brain to rewire itself to deal with danger rather than remember today's activities. Trauma survivors become programmed to experience an all-consuming, all-pervasive sense of fear and helplessness. Bullying poses a serious social, emotional, and academic threat to victims who experience it; victims of bullying are more likely to drop out of school, commit suicide, abuse substances, struggle with anxiety and depression, and have low self-esteem.

If a child is bullied without support from family members or authority figures, the toxic stress in the child's life is exacerbated and poses high risks for continued early development. A child left behind by family members or school administrators in difficult circumstances undoubtedly suffers more.

According to the Center for Child Development at Harvard University, “Without the care of adults who buffer children, the relentless stress of extreme poverty, neglect, abuse, or severe maternal depression can impair the functioning of the developing brain, with long-term consequences for learning, behavior, as well as physical and mental health. ”

”

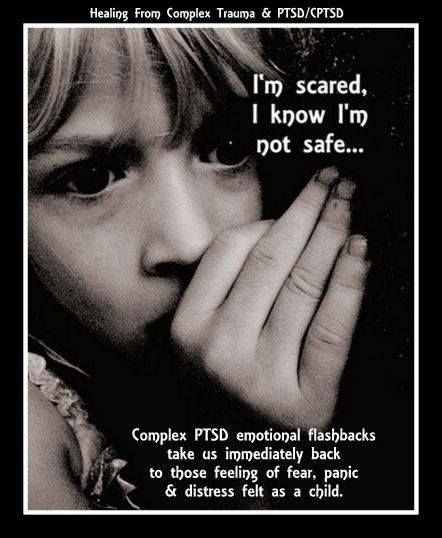

Complex trauma and complex post-traumatic stress disorder

While a single trauma is often associated with the development of post-traumatic stress disorder, complex trauma can cause symptoms beyond the scope of post-traumatic stress disorder - this can lead to complex post-traumatic stress disorder. Judith Herman first coined the term "complex post-traumatic stress disorder" to explain what happens when a person goes through a long period of victimization and loss of freedom, usually experienced in situations such as long-term domestic abuse, long-term child sexual abuse, prison camps, and organized child exploitation companies. In addition to the usual symptoms of PTSD, which include hypervigilance, avoidance, dissociation, nightmares, and flashbacks, a person with complex PTSD also experiences problems with emotional regulation, consciousness, self-perception, a distorted perception of the abuser, and impaired interpersonal relationships.

Childhood abuse can be seen as a form of "captivity", prolonged bullying where the child sees no way to escape. According to trauma therapist Pete Walker, multiple sources of trauma can lead to pervasive feelings of toxic shame, severe internal criticism, and emotional memories that cause the survivor to "regress" back to the original traumas of the past. Although complex PTSD is often associated with long-term sexual or physical abuse, Walker confirms that long-term emotional neglect and abuse can also be a factor in the disorder. Indeed, many studies confirm that verbal and emotional abuse can be just as damaging to the early developing brain as physical abuse (Teicher, 2006; Choi, 2009).; Copeland, 2013).

According to trauma therapist Pete Walker, multiple sources of trauma can lead to pervasive feelings of toxic shame, severe internal criticism, and emotional memories that cause the survivor to "regress" back to the original traumas of the past. Although complex PTSD is often associated with long-term sexual or physical abuse, Walker confirms that long-term emotional neglect and abuse can also be a factor in the disorder. Indeed, many studies confirm that verbal and emotional abuse can be just as damaging to the early developing brain as physical abuse (Teicher, 2006; Choi, 2009).; Copeland, 2013).

Trauma Replay: The Trauma Repetition Cycle

Part of complex PTSD is what therapists call "repetition compulsion." In his book Bonds of Betrayal: Breaking Free from an Exploitative Relationship, Patrick Karnes writes, “Part of the repetition of trauma is the victim's attempt to resolve the traumatic memory. By repeating the experience, the victim again tries to come up with a way to respond in order to get rid of fear. But instead, the victim simply deepens the traumatic wound.” It goes without saying that the amount of trauma a person experiences at the same time will influence the strength of the trauma recurrence cycle. Injuries combined with other injuries increase the overall risk of recurrence of injuries in adulthood.

But instead, the victim simply deepens the traumatic wound.” It goes without saying that the amount of trauma a person experiences at the same time will influence the strength of the trauma recurrence cycle. Injuries combined with other injuries increase the overall risk of recurrence of injuries in adulthood.

Not surprisingly, research has shown that children who are mistreated at home and by peers outside the home are more likely than children who are mistreated only at home to have serious mental health problems later in life. Due to the enormous impact of these traumas, and the emotional and psychological warfare that often accompanies bullying, survivors are accustomed to negative self-talk, blame themselves for the abuse they have suffered, and continue the vicious cycle of abuse.

They can deal with the shame that should belong to their abusers and develop maladaptive ways to deal with it. These maladaptive mechanisms represent lifelong attempts to survive unbearable, overwhelming trauma through destructive means that inevitably reproduce and reinforce the trauma. Survivors of complex trauma may seek unsafe mechanisms to regain control (eg, self-harm, under- or over-eating, drug abuse, etc.) in an attempt to survive a difficult situation. The toxic shame resulting from bullying and abuse can lead to behaviors such as maintaining abusive relationships, addictions, eating disorders, and reckless sexual behavior, futile attempts to avoid trauma, and cause "numbness" in response to symptoms.

Survivors of complex trauma may seek unsafe mechanisms to regain control (eg, self-harm, under- or over-eating, drug abuse, etc.) in an attempt to survive a difficult situation. The toxic shame resulting from bullying and abuse can lead to behaviors such as maintaining abusive relationships, addictions, eating disorders, and reckless sexual behavior, futile attempts to avoid trauma, and cause "numbness" in response to symptoms.

For example, the Adverse Childhood Experience study found that childhood abuse not only increases the risk of health problems such as obesity, heart disease, cancer, stroke, but also increases the risk of alcoholism, depression, suicide attempts, teenage pregnancy , STDs, etc.

Reproduction of past trauma is not a coincidence, but a consequence of the trauma itself.

Social isolation, anxiety and destructive relationships

Another symptom of complex trauma accompanied by bullying is increased social anxiety and self-isolation as a form of self-protection; victims of bullying often forgo school to avoid places where bullying has occurred. They may fear and distrust either their peers or authority figures, especially if they know that these people have done nothing to protect them. This pervasive sense of distrust, unfortunately, does not make the survivor immune to the repetition of these patterns in adult relationships. When childhood trauma is permanent and chronic, it becomes unbearable for the body and leaves the body in a constant state of heightened alertness and heightened arousal (Perry, 2000).

They may fear and distrust either their peers or authority figures, especially if they know that these people have done nothing to protect them. This pervasive sense of distrust, unfortunately, does not make the survivor immune to the repetition of these patterns in adult relationships. When childhood trauma is permanent and chronic, it becomes unbearable for the body and leaves the body in a constant state of heightened alertness and heightened arousal (Perry, 2000).

Betrayal by close friends, family members, or even partners can cause what Patrick Carnes calls "betrayal bonding" and psychological trauma. Bonds of trauma are bonds that develop between victims and their abusers; these bonds act as defense mechanisms to enable victims to survive in a turbulent and hostile environment.

Survivors of bullying, both at home and at school, may develop habits that endear others because they had to walk on eggshells as children. Conditions in which survivors become deaf to emotional and psychological abuse during adolescence may also force them to seek out partners and friends who remind them of their first abusers as adults.

As bullied children become adults, they experience emotional abuse as a "familiar", dangerous comfort zone that keeps them trapped in a cycle of trauma repetition. This is why so many complex trauma survivors often blame themselves and continue to "bully" themselves into self-harm when they engage in self-destructive behavior, unaware that trauma replay is often a symptom of their complex post-traumatic stress disorder.

Healing of complex trauma

Despite the complex nature of the trauma, there is hope for healing and self-reflection. Survivors of complex trauma can tap into their subconscious mind using a variety of healing methods, including traditional therapies, EMDR, art therapy, hypnosis, sound therapy, meditation, yoga, and other forms of bodywork that allow them to relax.

Healing methods should always be discussed with a certified trauma specialist to ensure that the survivor is aware of their unique needs and triggers. Survivors can learn to mourn the losses they experienced both in childhood and adulthood, to comprehend all the emotions that arose as a result of complex trauma. They can learn to distance themselves from negative self-talk and learn to "repair" their inner child through self-soothing techniques.

They can learn to distance themselves from negative self-talk and learn to "repair" their inner child through self-soothing techniques.

They can seek support through group therapy with other survivors, trusted friends or mentors, survivor forums and online communities. Most importantly, they can rewrite their tales of helplessness into tales of power and free will.

About the author Shahida Arabi is a graduate of Columbia University where she has studied the impact of violence on survivors' lives. She is also the author of three bestsellers. You can find her blog on abuse and trauma at Self-Care Haven.

Abuse of a child leads to his depression in the future | All the news Bank of the Hornets0003

Without a New Year's surprise: who will build the main ice town of Chelyabinsk this year and for how much

A missing man was found stuck in the sewers of another city. How it was rescued — footage from the scene

The Smolino embankment project was submitted to public hearings two years after its creation

In Chelyabinsk, companies will be helped with the transportation of products abroad

In the color of snow: 10 best manicure ideas that will be at the peak of fashion this in winter - show them to your master

“No matter how old or how big you are, you can be beautiful”: a bank employee became a model at the age of 50 crushed two workers

Lost weight, makes films and puts on performances: how Mikhail Efremov's life has changed in two years in prison

A mobilized man with many children from the Chelyabinsk region died two weeks after being sent to the service

“I received an offer, but refused”: the convict told about recruitment to PMCs — how it happened and what he was promised

“The situation with partial mobilization gave a kick”: how a 27-year-old Russian left everything and went to live in South Africa

B A 20-year-old orphan who died during a special military operation was buried in Magnitogorsk

Payments to the mobilized were exempted from taxes

A kindergarten teacher was sued in Chelyabinsk for trying to feed a three-year-old child by force

Lucky or hard worker: the most successful businesses in Chelyabinsk were named — who to take an example from

“There should be no slippery topics here”: an urbanist — about how services (in) cope with the cleaning of Chelyabinsk

The Ministry of Digital Development will stop accepting applications from IT people for deferment from mobilization

Round trip. Which foreign brands have returned to Russia

Which foreign brands have returned to Russia

Popular burger shops in gastroparks in Chelyabinsk have closed

The Ministry of Internal Affairs has named the number of schools that were hit by a wave of "mining" in Chelyabinsk

“Water gushed from an electric pole”: a public emergency near Lenta left the AMZ village without water (video)

“I call this time hell”: how a large family returned home a mobilized ambulance driver

Find a job in the evening: in Yekaterinburg "Career Time" campaign will be held

Children and workers were evacuated from a school in Chelyabinsk due to a report of mining

In 2023, seven child allowances will be replaced by one. What is known about him?

Russian provider opened a new season of optical construction in the Chelyabinsk region

Chelyabinsk mayor's office dismissed Vladimir Shamne, deputy head of the city for construction

“Let them hire me as a machine gunner, I will fight next to my son”: how soldiers’ mothers react to mobilization – an honest interview

The Business Success award was presented in Chelyabinsk

“ Become the blacksmith of your success”: how to make the right decision when choosing a working specialty

Money to money: how to save on utility bills

Fragile on the outside and strong on the inside: at the forum “Steel Lace of the Urals” women will be taught how to deal with crises

“The house is growing by leaps and bounds”: who and why “built up” the skyscraper next to the Shopping Center in Chelyabinsk

Just to remind you: how do we relax and work in 2023 — calendar

“Puck” was abandoned? Why the surrender of the regional hockey center in Chelyabinsk spilled over into overtime They studied data from almost two hundred Americans aged 18 to 25. Most of the participants in the study were from the middle class with a high level of education. The scientists were interested in the abuse of parents with volunteers in childhood, as well as the lack of parental attention.

Most of the participants in the study were from the middle class with a high level of education. The scientists were interested in the abuse of parents with volunteers in childhood, as well as the lack of parental attention.

Approximately a quarter of the volunteers were diagnosed with major depressive disorder, and seven percent were diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. At the same time, 16 percent of participants experienced abuse in at least several forms - physical abuse, verbal abuse, as well as lack of attention from parents. In this group, depression was diagnosed in 53 percent of volunteers, and 40 percent suffered from post-traumatic depression.

The scientists used tomography to evaluate the participants' brains. Regardless of the state of mind at the time of the survey, two areas of the hippocampus (a region of the brain involved in the formation of emotions and the consolidation of memory) in young survivors of abuse showed a decrease in the volume of nervous tissue by six percent.