Psychosis and autism

Recognizing Psychosis in Autism Spectrum Disorder

1. Bleuler E. Dementia praecox oder Gruppe der Schizophrenien. Leipzig: Deuticke; (1911). [Google Scholar]

2. Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Acta Paedopsychiatr. (1968) 35:100–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Konstantareas MM, Hewitt T. Autistic disorder and schizophrenia: diagnostic overlaps. J Autism Dev Disord. (2001) 31:19–28. 10.1023/A:1005605528309 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Kastner A, Begemann M, Michel TM, Everts S, Stepniak B, Bach C, et al.. Autism beyond diagnostic categories: characterization of autistic phenotypes in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. (2015) 15:115. 10.1186/s12888-015-0494-x [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Crespi BJ. Revisiting Bleuler: relationship between autism and schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. (2010) 196:495. 10.1192/bjp.196.6.495 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Parnas J, Bovet P. Autism in schizophrenia revisited. Compr Psychiatry. (1991) 32:7–21. 10.1016/0010-440X(91)90065-K [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Volkmar FR, McPartland JC. From Kanner to DSM-5: autism as an evolving diagnostic concept. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. (2014) 10:193–212. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153710 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Skokauskas N, Gallagher L. Psychosis, affective disorders and anxiety in autistic spectrum disorder: prevalence and nosological considerations. Psychopathology. (2010) 43:8–16. 10.1159/000255958 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. de Lacy N, King BH. Revisiting the relationship between autism and schizophrenia: toward an integrated neurobiology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. (2013) 9:555–87. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185627 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Deste G, Barlati S, Gregorelli M, Lisoni J, Turrina C, Valsecchi P, et al.. Looking through autistic features in schizophrenia using the PANSS Autism Severity Score (PAUSS). Psychiatry Res. (2018) 270:764–8. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.10.074 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10.1016/j.psychres.2018.10.074 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Kincaid DL, Doris M, Shannon C, Mulholland C. What is the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder and ASD traits in psychosis? A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. (2017) 250:99–105. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.017 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Chisholm K, Lin A, Abu-Akel A, Wood SJ. The association between autism and schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a review of eight alternate models of co-occurrence. Neurosci Biobehav R. (2015) 55:173–83. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.04.012 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Mazza M, Pino MC, Keller R, Vagnetti R, Attanasio M, Filocamo A, et al.. Qualitative differences in attribution of mental states to other people in autism and schizophrenia: what are the tools for differential diagnosis? J Autism Dev Disord. (2021) 52:1283–98. 10.1007/s10803-021-05035-3 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Bakken TL. Behavioural equivalents of schizophrenia in people with intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder: A selective review. Int J Dev Disabil. (2021) 67:310–7. 10.1080/20473869.2021.1925402 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Int J Dev Disabil. (2021) 67:310–7. 10.1080/20473869.2021.1925402 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Dsm-5. American Psychiatric Publishing, Incorporated; (2013). 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Jaspers K. General Psychopathology. JHU Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

17. Esquirol E, Hunt EK. Mental Maladies; A Treatise on Insanity Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard; (1845). 10.1097/00000441-184507000-00020 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Kirkpatrick B, Fenton WS, Carpenter WT, Jr., Marder SR. The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms. Schizophr Bull. (2006) 32:214–9. 10.1093/schbul/sbj053 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Kiran C, Chaudhury S. Understanding delusions. Ind Psychiatry J. (2009) 18:3–18. 10.4103/0972-6748.57851 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Bebbington P, Freeman D. Transdiagnostic extension of delusions: schizophrenia and beyond. Schizophr Bull. (2017) 43:273–82. 10.1093/schbul/sbw191 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Bebbington P, Freeman D. Transdiagnostic extension of delusions: schizophrenia and beyond. Schizophr Bull. (2017) 43:273–82. 10.1093/schbul/sbw191 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Dykens E, Volkmar F, Glick M. Though disorder in high-functioning autistic adults. J Autism Dev Disord. (1991) 21:291–301. 10.1007/BF02207326 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22. Darr GC, Worden FG. Case report twenty-eight years after an infantile autistic disorder. Am J Orthopsychiatry. (1951) 21:559–70. 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1951.tb00012.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. Wolff S, Barlow A. Schizoid personality in childhood: a comparative study of schizoid, autistic and normal children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (1979) 20:29–46. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1979.tb01704.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

24. Mahler MS, Ross JR Jr, De Fries Z. Clinical studies in benign and malignant cases of childhood psychosis (schizophrenia-like). Am J Orthopsychiatry. (1949) 19:295–305. 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1949.tb05149.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

(1949) 19:295–305. 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1949.tb05149.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Ekstein R, Wallerstein J. Observations on the psychotherapy of borderline and psychotic children. Psychoanal Study Child. (1956) 11:303–11. 10.1080/00797308.1956.11822790 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Geleerd ER. Borderline states in childhood and adolescence. Psychoanal Study Child. (1958) 13:279–95. 10.1080/00797308.1958.11823183 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

27. Singer MB. Fantasies of a borderline patient. Psychoanal Study Child. (1960) 15:310–56. 10.1080/00797308.1960.11822581 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

28. Weil AP. Certain severe disturbances of EGO development in childhood. Psychoanal Study Child. (1953) 8:271–87. 10.1080/00797308.1953.11822772 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Abell F, Hare DJ. An experimental investigation of the phenomenology of delusional beliefs in people with Asperger syndrome. Autism. (2005) 9:515–31. 10.1177/1362361305057857 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

30. Clarke D, Baxter M, Perry D, Prasher V. The diagnosis of affective and psychotic disorders in adults with autism: seven case reports. Autism. (1999) 3:149–64. 10.1177/1362361399003002005 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Clarke D, Baxter M, Perry D, Prasher V. The diagnosis of affective and psychotic disorders in adults with autism: seven case reports. Autism. (1999) 3:149–64. 10.1177/1362361399003002005 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

31. Tantam D. Asperger Syndrome in Adulthood. Autism and Asperger syndrome. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; (1991). p. 147–83. 10.1017/CBO9780511526770.005 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

32. Szatmari P. Asperger's syndrome: diagnosis, treatment, and outcome. Psychiatr Clin North Am. (1991) 14:81–93. 10.1016/S0193-953X(18)30326-5 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

33. Rutter M, Lockyer LA. five to fifteen year follow-up study of infantile psychosis. I Description of sample. Br J Psychiatry. (1967) 113:1169–82. 10.1192/bjp.113.504.1169 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

34. Rutter M. Childhood schizophrenia reconsidered. J Autism Child Schizophr. (1972) 2:315–37. 10.1007/BF01537622 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

35. Evans B. How autism became autism: the radical transformation of a central concept of child development in Britain. Hist Human Sci. (2013) 26:3–31. 10.1177/0952695113484320 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Hist Human Sci. (2013) 26:3–31. 10.1177/0952695113484320 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

36. Bisagni F. Delusional development in child autism at the onset of puberty: vicissitudes of psychic dimensionality between disintegration and development. Int J Psychoanal. (2012) 93:667–92. 10.1111/j.1745-8315.2012.00596.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

37. Gillberg C. Asperger's syndrome and recurrent psychosis–a case study. J Autism Dev Disord. (1985) 15:389–97. 10.1007/BF01531783 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

38. Petty LK, Ornitz EM, Michelman JD, Zimmerman EG. Autistic children who become schizophrenic. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1984) 41:129–35. 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790130023003 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

39. Volkmar FR, Cohen DJ, Paul R. An evaluation of DSM-III criteria for infantile autism. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. (1986) 25:190–7. 10.1016/S0002-7138(09)60226-0 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

40. Baron-Cohen S, Leslie AM, Frith U. Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind” ? Cognition. (1985) 21:37–46. 10.1016/0010-0277(85)90022-8 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind” ? Cognition. (1985) 21:37–46. 10.1016/0010-0277(85)90022-8 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

41. Bora E, Yucel M, Pantelis C. Theory of mind impairment in schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. (2009) 109:1–9. 10.1016/j.schres.2008.12.020 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

42. Chung YS, Barch D, Strube M. A meta-analysis of mentalizing impairments in adults with schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder. Schizophr Bull. (2014) 40:602–16. 10.1093/schbul/sbt048 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

43. Bliksted V, Videbech P, Fagerlund B, Frith C. The effect of positive symptoms on social cognition in first-episode schizophrenia is modified by the presence of negative symptoms. Neuropsychology. (2017) 31:209–19. 10.1037/neu0000309 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

44. Frith CD. The Cognitive Neuropsychology of Schizophrenia: Classic Edition. Psychology Press; (2015). 10.4324/9781315785011 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

45. Pilowsky T, Yirmiya N, Arbelle S, Mozes T. Theory of mind abilities of children with schizophrenia, children with autism, and normally developing children. Schizophr Res. (2000) 42:145–55. 10.1016/S0920-9964(99)00101-2 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Pilowsky T, Yirmiya N, Arbelle S, Mozes T. Theory of mind abilities of children with schizophrenia, children with autism, and normally developing children. Schizophr Res. (2000) 42:145–55. 10.1016/S0920-9964(99)00101-2 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

46. Tin LNW, Lui SSY, Ho KKY, Hung KSY, Wang Y, Yeung HKH, et al.. High-functioning autism patients share similar but more severe impairments in verbal theory of mind than schizophrenia patients. Psychol Med. (2018) 48:1264–73. 10.1017/S0033291717002690 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

47. Blackshaw AJ, Kinderman P, Hare DJ, Hatton C. Theory of mind, causal attribution and paranoia in Asperger syndrome. Autism. (2001) 5:147–63. 10.1177/1362361301005002005 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

48. Craig JS, Hatton C, Craig FB, Bentall RP. Persecutory beliefs, attributions and theory of mind: comparison of patients with paranoid delusions, Asperger's syndrome and healthy controls. Schizophr Res. (2004) 69:29–33. 10. 1016/S0920-9964(03)00154-3 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

1016/S0920-9964(03)00154-3 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

49. Pinkham AE, Harvey PD, Penn DL. Paranoid individuals with schizophrenia show greater social cognitive bias and worse social functioning than non-paranoid individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res Cogn. (2016) 3:33–8. 10.1016/j.scog.2015.11.002 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

50. Kaney S, Bentall RP. Persecutory delusions and attributional style. Br J Med Psychol. (1989) 62(Pt 2):191–8. 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1989.tb02826.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

51. Corcoran R, Mercer G, Frith CD. Schizophrenia, symptomatology and social inference - investigating theory of mind in people with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. (1995) 17:5–13. 10.1016/0920-9964(95)00024-G [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

52. Smari J, Stefansson S, Thorgilsson H. Paranoia, self-consciousness, and social cognition in schizophrenics. Cognitive Ther Res. (1994) 18:387–99. 10.1007/BF02357512 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

53. Schneider K. Clinical Psychopathology. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton; (1959). [Google Scholar]

Schneider K. Clinical Psychopathology. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton; (1959). [Google Scholar]

54. Waters F, Fernyhough C. Hallucinations: a systematic review of points of similarity and difference across diagnostic classes. Schizophr Bull. (2017) 43:32–43. 10.1093/schbul/sbw132 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

55. Van Schalkwyk GI, Peluso F, Qayyum Z, McPartland JC, Volkmar FR. Varieties of misdiagnosis in ASD: an illustrative case series. J Autism Dev Disord. (2015) 45:911–8. 10.1007/s10803-014-2239-y [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

56. Ben-Sasson A, Hen L, Fluss R, Cermak SA, Engel-Yeger B, Gal E, et al.. A meta-analysis of sensory modulation symptoms in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. (2009) 39:1–11. 10.1007/s10803-008-0593-3 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

57. Baker AE, Lane A, Angley MT, Young RL. The relationship between sensory processing patterns and behavioural responsiveness in autistic disorder: a pilot study. J Autism Dev Disord. (2008) 38:867–75. 10.1007/s10803-007-0459-0 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J Autism Dev Disord. (2008) 38:867–75. 10.1007/s10803-007-0459-0 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

58. Baranek GT, David FJ, Poe MD, Stone WL, Watson LR. Sensory Experiences Questionnaire: discriminating sensory features in young children with autism, developmental delays, and typical development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2006) 47:591–601. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01546.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

59. Tomchek SD, Dunn W. Sensory processing in children with and without autism: a comparative study using the short sensory profile. Am J Occup Ther. (2007) 61:190–200. 10.5014/ajot.61.2.190 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

60. Leekam SR, Nieto C, Libby SJ, Wing L, Gould J. Describing the sensory abnormalities of children and adults with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. (2007) 37:894–910. 10.1007/s10803-006-0218-7 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

61. Horder J, Wilson CE, Mendez MA, Murphy DG. Autistic traits and abnormal sensory experiences in adults. J Autism Dev Disord. (2014) 44:1461–9. 10.1007/s10803-013-2012-7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

62. Milne E, Dickinson A, Smith R. Adults with autism spectrum conditions experience increased levels of anomalous perception. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0177804. 10.1371/journal.pone.0177804 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

63. Cesaroni L, Garber M. Exploring the experience of autism through firsthand accounts. J Autism Dev Disord. (1991) 21:303–13. 10.1007/BF02207327 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

64. Jones RSP, Quigney C, Huws JC. First-hand accounts of sensory perceptual experiences in autism: a qualitative analysis. J Intellect Dev Dis. (2003) 28:112–21. 10.1080/1366825031000147058 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

65. Kjelgaard MM, Tager-Flusberg H. An investigation of language impairment in autism: implications for genetic subgroups. Lang Cogn Process. (2001) 16:287–308. 10.1080/01690960042000058 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

66. Fogler J, Kuhn J, Prock L, Radesky J, Gonzalez-Heydrich J. Diagnostic uncertainty in a complex young man: autism versus psychosis. J Dev Behav Pediatr. (2019) 40:72–4. 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000635 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Fogler J, Kuhn J, Prock L, Radesky J, Gonzalez-Heydrich J. Diagnostic uncertainty in a complex young man: autism versus psychosis. J Dev Behav Pediatr. (2019) 40:72–4. 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000635 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

67. Dossetor DR. 'All that glitters is not gold': misdiagnosis of psychosis in pervasive developmental disorders–a case series. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2007) 12:537–48. 10.1177/1359104507078476 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

68. Carpenter WT J, Heinrichs DW, Alphs LD. Treatment of negative symptoms. Schizophr Bull. (1985) 11:440–52. 10.1093/schbul/11.3.440 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

69. Andreasen NC. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS): conceptual and theoretical foundations. Br J Psychiatry. (1989) 155:49–52. 10.1192/S0007125000291496 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

70. Lewine RR, Fogg L, Meltzer HY. Assessment of negative and positive symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (1983) 9:368–76. 10.1093/schbul/9.3.368 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10.1093/schbul/9.3.368 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

71. Kirkpatrick B, Buchanan RW, McKenney PD, Alphs LD, Carpenter WT Jr. The Schedule for the Deficit syndrome: an instrument for research in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. (1989) 30:119–23. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90153-4 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

72. Horan WP, Kring AM, Gur RE, Reise SP, Blanchard JJ. Development and psychometric validation of the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS). Schizophr Res. (2011) 132:140–5. 10.1016/j.schres.2011.06.030 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

73. Aleman A, Lincoln TM, Bruggeman R, Melle I, Arends J, Arango C, et al.. Treatment of negative symptoms: where do we stand, and where do we go? Schizophr Res. (2017) 186:55–62. 10.1016/j.schres.2016.05.015 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

74. Millan MJ, Andrieux A, Bartzokis G, Cadenhead K, Dazzan P, Fusar-Poli P, et al.. Altering the course of schizophrenia: progress and perspectives. Nat Rev Drug Discov. (2016) 15:485–515. 10.1038/nrd.2016.28 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Nat Rev Drug Discov. (2016) 15:485–515. 10.1038/nrd.2016.28 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

75. Harvey PD, Strassnig M. Predicting the severity of everyday functional disability in people with schizophrenia: cognitive deficits, functional capacity, symptoms, and health status. World Psychiatry. (2012) 11:73–9. 10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.05.004 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

76. Rabinowitz J, Levine SZ, Garibaldi G, Bugarski-Kirola D, Berardo CG, Kapur S. Negative symptoms have greater impact on functioning than positive symptoms in schizophrenia: analysis of CATIE data. Schizophr Res. (2012) 137:147–50. 10.1016/j.schres.2012.01.015 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

77. Haslam J. Illustrations of Madness: Exhibiting a Singular Case of Insanity, and a No Less Remarkable Difference in Medical Opinion: Developing the Nature of Assailment, and the Manner of Working Events: With a Description of the Tortures Experienced by Bomb-bursting, Lobster-cracking, and Lenghthening the Brain. Embellished with a Curious Plate. London: G Hayden; (1810). [Google Scholar]

Embellished with a Curious Plate. London: G Hayden; (1810). [Google Scholar]

78. Kraepelin E. Psychiatrie. In: Ein Lehrbuch f,r Studierende und rzte Leipzig. JA Barth; (1913). [Google Scholar]

79. Berrios GE. The History of Mental Symptoms: Descriptive Psychopathology Since the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; (1996). 10.1017/CBO9780511526725 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

80. Minkowski E. La schizophrÈnie: psychopathologie des schizoÔdes et de schizophrËnes. Paris: Payot & Rivages; (2010). [Google Scholar]

81. Dide M, Guiraud P, Psychiatrie du mÈdecin praticien. Paris: Masson et Cie; (1922). [Google Scholar]

82. Jackson JH, Taylor J, Holmes G, Walshe F. Selected writings of John Hughlings Jackson: evolution and dissolution of the nervous system. In: Speech Various Papers, Addresses, and Lectures. Staples: (1958). [Google Scholar]

83. Crow TJ, Frith CD, Johnstone EC, Owens DGC, Weinberger D, Jed Wyatt R, et al.. Atrophy. Lancet. (1980) 315:1129–30. 10.1016/S0140-6736(80)91569-X [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Lancet. (1980) 315:1129–30. 10.1016/S0140-6736(80)91569-X [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

84. Crow TJ. The biology of schizophrenia. Experientia. (1982) 38:1275–82. 10.1007/BF01954914 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

85. Crow TJ. The two-syndrome concept: origins and current status. Schizophr Bull. (1985) 11:471–88. 10.1093/schbul/11.3.471 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

86. Andreasen NC, Olsen S. Negative v positive schizophrenia. Definition and validation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1982) 39:789–94. 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290070025006 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

87. Andreasen NC. Positive vs. negative schizophrenia: a critical evaluation. Schizophr Bull. (1985) 11:380–9. 10.1093/schbul/11.3.380 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

88. Carpenter WT Jr, Heinrichs DW, Wagman AM. Deficit and nondeficit forms of schizophrenia: the concept. Am J Psychiatry. (1988) 145:578–83. 10.1176/ajp.145.5.578 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

89. Lincoln TM, Dollfus S, Lyne J. Current developments and challenges in the assessment of negative symptoms. Schizophr Res. (2017) 186:8–18. 10.1016/j.schres.2016.02.035 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Lincoln TM, Dollfus S, Lyne J. Current developments and challenges in the assessment of negative symptoms. Schizophr Res. (2017) 186:8–18. 10.1016/j.schres.2016.02.035 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

90. Galderisi S, Mucci A, Buchanan RW, Arango C. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: new developments and unanswered research questions. Lancet Psychiatry. (2018) 5:664–77. 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30050-6 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

91. Kaiser S, Lyne J, Agartz I, Clarke M, Morch-Johnsen L, Faerden A. Individual negative symptoms and domains - relevance for assessment, pathomechanisms and treatment. Schizophr Res. (2017) 186:39–45. 10.1016/j.schres.2016.07.013 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

92. Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child. (1943) 2:217–50. [Google Scholar]

93. Kolvin I. Studies in the childhood psychoses. I Diagnostic criteria and classification. Br J Psychiatry. (1971) 118:381–4. 10.1192/bjp.118.545.381 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

94. Hommer RE, Swedo SE. Schizophrenia and autism-related disorders. Schizophr Bull. (2015) 41:313–4. 10.1093/schbul/sbu188 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Hommer RE, Swedo SE. Schizophrenia and autism-related disorders. Schizophr Bull. (2015) 41:313–4. 10.1093/schbul/sbu188 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

95. Schmidt SJ, Behar A, Schultze-Lutter F. Asperger syndrome and/or clinical high risk of psychosis? A differential diagnostic challenge. Prax Kinderpsychol Kinderpsychiatr. (2018) 67:274–93. 10.13109/prkk.2018.67.3.274 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

96. De Crescenzo F, Postorino V, Siracusano M, Riccioni A, Armando M, Curatolo P, et al.. Autistic symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:78. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00078 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

97. van Ommeren TB, Begeer S, Scheeren AM, Koot HM. Measuring reciprocity in high functioning children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. (2012) 42:1001–10. 10.1007/s10803-011-1331-9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

98. World Health Organization . The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. Geneva: World Health Organization; (1993). [Google Scholar]

World Health Organization . The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. Geneva: World Health Organization; (1993). [Google Scholar]

99. Cochran DM, Dvir Y, Frazier JA. “Autism-plus” spectrum disorders: intersection with psychosis and the schizophrenia spectrum. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. (2013) 22:609–27. 10.1016/j.chc.2013.04.005 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

100. Larson FV, Wagner AP, Jones PB, Tantam D, Lai MC, Baron-Cohen S, et al.. Psychosis in autism: comparison of the features of both conditions in a dually affected cohort. Br J Psychiatry. (2017) 210:269–75. 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.187682 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

101. Tezenas du Montcel C, Pelissolo A, Schurhoff F, Pignon B. Obsessive-compulsive symptoms in schizophrenia: an up-to-date review of literature. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2019) 21:64. 10.1007/s11920-019-1051-y [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

102. Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, Phillips LJ, Kelly D, Dell'Olio M, et al. . Mapping the onset of psychosis: the comprehensive assessment of at-risk mental states. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2005) 39:964–71. 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01714.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the comprehensive assessment of at-risk mental states. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2005) 39:964–71. 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01714.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

103. Di Michele V, Bolino F. The natural course of schizophrenia and psychopathological predictors of outcome. A community-based cohort study. Psychopathology. (2004) 37:98–104. 10.1159/000078090 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

104. Miettunen J, Immonen J, McGrath JJ, Isohanni M, Jääskeläinen E. The age of onset of schizophrenia spectrum disorders. In: Age of Onset of Mental Disorders Springer: (2019). p. 55–73. 10.1007/978-3-319-72619-9_4 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

105. Chawarska K, Klin A, Paul R, Macari S, Volkmar F. A prospective study of toddlers with ASD: short-term diagnostic and cognitive outcomes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2009) 50:1235–45. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02101.x [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

106. Parr JR, Le Couteur A, Baird G, Rutter M, Pickles A, Fombonne E, et al. . Early developmental regression in autism spectrum disorder: evidence from an international multiplex sample. J Autism Dev Disord. (2011) 41:332–40. 10.1007/s10803-010-1055-2 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

. Early developmental regression in autism spectrum disorder: evidence from an international multiplex sample. J Autism Dev Disord. (2011) 41:332–40. 10.1007/s10803-010-1055-2 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

107. Shattuck PT, Durkin M, Maenner M, Newschaffer C, Mandell DS, Wiggins L, et al.. Timing of identification among children with an autism spectrum disorder: findings from a population-based surveillance study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2009) 48:474–83. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819b3848 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

108. Naito K, Matsui Y, Maeda K, Tanaka K. Evaluation of the validity of the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) in differentiating high-functioning autistic spectrum disorder from schizophrenia. Kobe J Med Sci. (2010) 56:E116–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

109. Bartlett J. Childhood-onset schizophrenia: what do we really know? Health Psychol Behav Med. (2014) 2:735–47. 10.1080/21642850.2014.927738 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

110. Driver DI, Gogtay N, Rapoport JL. Childhood onset schizophrenia and early onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. (2013) 22:539–55. 10.1016/j.chc.2013.04.001 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Driver DI, Gogtay N, Rapoport JL. Childhood onset schizophrenia and early onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. (2013) 22:539–55. 10.1016/j.chc.2013.04.001 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

111. Rapoport J, Chavez A, Greenstein D, Addington A, Gogtay N. Autism spectrum disorders and childhood-onset schizophrenia: clinical and biological contributions to a relation revisited. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2009) 48:10–8. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31818b1c63 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

112. Alaghband-Rad J, McKenna K, Gordon CT, Albus KE, Hamburger SD, Rumsey JM, et al.. Childhood-onset schizophrenia: the severity of premorbid course. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (1995) 34:1273–83. 10.1097/00004583-199510000-00012 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

113. Watkins JM, Asarnow RF, Tanguay PE. Symptom development in childhood onset schizophrenia. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (1988) 29:865–78. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1988.tb00759.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10.1111/j.1469-7610.1988.tb00759.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

114. Coghill D, Bonnar S, Seth S, Duke S, Graham J. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Oxford, MI: Oxford University Press; (2009). 10.1093/med/9780199234998.001.0001 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

115. Taylor JL. The transition out of high school and into adulthood for individuals with autism and for their families. Int Rev Res Mental Retard. (2009) 38:1–32. 10.1016/S0074-7750(08)38001-X [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

116. Buitelaar JK, van der Gaag RJ. Diagnostic rules for children with PDD-NOS and multiple complex developmental disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (1998) 39:911–9. 10.1017/S0021963098002820 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

117. Towbin KE, Dykens EM, Pearson GS, Cohen DJ. Conceptualizing “borderline syndrome of childhood” and “childhood schizophrenia” as a developmental disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (1993) 32:775–82. 10.1097/00004583-199307000-00011 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

118. Xavier J, Vannetzel L, Viaux S, Leroy A, Plaza M, Tordjman S, et al.. Reliability and diagnostic efficiency of the Diagnostic Inventory for Disharmony (DID) in youths with Pervasive Developmental Disorder and Multiple Complex Developmental Disorder. Res Autism Spectr Disord. (2011) 5:1493–9. 10.1016/j.rasd.2011.02.010 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Xavier J, Vannetzel L, Viaux S, Leroy A, Plaza M, Tordjman S, et al.. Reliability and diagnostic efficiency of the Diagnostic Inventory for Disharmony (DID) in youths with Pervasive Developmental Disorder and Multiple Complex Developmental Disorder. Res Autism Spectr Disord. (2011) 5:1493–9. 10.1016/j.rasd.2011.02.010 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

119. Hatila S, Solanki G. Co-occurrence of autistic spectrum disorder and childhood-onset schizophrenia. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. (2020) 22:2515. 10.4088/PCC.19l02515 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

120. Keller R, Piedimonte A, Bianco F, Bari S, Cauda F. Diagnostic characteristics of psychosis and autism spectrum disorder in adolescence and adulthood. A case series. Autism Open Access. (2015) 6:159. 10.4172/2165-7890.1000159 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

121. Addington J, Piskulic D, Liu L, Lockwood J, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, et al.. Comorbid diagnoses for youth at clinical high risk of psychosis. Schizophr Res. (2017) 190:90–5. 10.1016/j.schres.2017.03.043 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10.1016/j.schres.2017.03.043 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

122. Solomon M, Olsen E, Niendam T, Ragland JD, Yoon J, Minzenberg M, et al.. From lumping to splitting and back again: atypical social and language development in individuals with clinical-high-risk for psychosis, first episode schizophrenia, and autism spectrum disorders. Schizophr Res. (2011) 131:146–51. 10.1016/j.schres.2011.03.005 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

123. Barneveld PS, Pieterse J, de Sonneville L, van Rijn S, Lahuis B, van Engeland H, et al.. Overlap of autistic and schizotypal traits in adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Schizophr Res. (2011) 126:231–6. 10.1016/j.schres.2010.09.004 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

124. Foss-Feig JH, Velthorst E, Smith L, Reichenberg A, Addington J, Cadenhead KS, et al.. Clinical profiles and conversion rates among young individuals with autism spectrum disorder who present to clinical high risk for psychosis services. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2019) 58:582–8. 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.09.446 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2019) 58:582–8. 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.09.446 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

125. Fusar-Poli P, Raballo A, Parnas J. What is an attenuated psychotic symptom? On the importance of the context. Schizophr Bull. (2017) 43:687–92. 10.1093/schbul/sbw182 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

126. Schriber RA, Robins RW, Solomon M. Personality and self-insight in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. J Pers Soc Psychol. (2014) 106:112–30. 10.1037/a0034950 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Psychosis in autism: comparison of the features of both conditions in a dually affected cohort

1. King BH, Lord C. Is schizophrenia on the autism spectrum? Brain Res 2011; 1380: 34–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Mouridsen SE, Rich B, Isager T. Psychiatric disorders in adults diagnosed as children with atypical autism. A case control study. J Neural Transm 2008; 115: 135–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Selten J-P, Lundberg M, Rai D, Magnusson C. Risks for non-affective psychotic disorder and bipolar disorder in young people with autism spectrum disorder: a population-based study. JAMA Psychiatry 2015; 72: 483–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Khandaker GM, Stochl J, Zammit S, Lewis G, Jones PB. A population-based longitudinal study of childhood neurodevelopmental disorders, IQ and subsequent risk of psychotic experiences in adolescence. Psychol Med 2014; 44: 3229–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Clarke D, Baxter M, Perry D, Prasher V. The diagnosis of affective and psychotic disorders in adults with autism: seven case reports. Autism 1999; 3: 149–64. [Google Scholar]

6. Lai M-C, Baron-Cohen S. Identifying the lost generation of adults with autism spectrum conditions. Lancet Psychiatry 2015; 2: 1013–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Lord C, Rutter M, Goode S, Heemsbergen J, Jordan H, Mawhood L, et al. Austism Diagnostic Observation Schedule: a standardized observation of communicative and social behavior. J Autism Dev Disord 1989; 19: 185–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Austism Diagnostic Observation Schedule: a standardized observation of communicative and social behavior. J Autism Dev Disord 1989; 19: 185–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 1994; 24: 659–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Castle DJ, Jablensky A, McGrath JJ, Carr V, Morgan V, Waterreus A, et al. The diagnostic interview for psychoses (DIP): development, reliability and applications. Psychol Med 2006; 36: 69–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Prosser H, Moss S, Costello H, Simpson N, Patel P, Rowe S. Reliability and validity of the Mini PAS-ADD for assessing psychiatric disorders in adults with intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res 1998; 42: 264–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. McGuffin P, Farmer A, Harvey I. A polydiagnostic application of operational criteria in studies of psychotic illness: development and reliability of the OPCRIT system. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48: 764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48: 764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. World Health Organisation International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). WHO, 2007. [Google Scholar]

13. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edn) (DSM-IV). APA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

14. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E. Research Diagnostic Criteria: rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35: 773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. The Psychological Corporation, 1999. [Google Scholar]

16. Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Robinson J, Woodbury-Smith M. The Adult Asperger Assessment (AAA): a diagnostic method. J Autism Dev Disord 2005; 35: 807–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Lai M-C, Lombardo M V, Ruigrok AN V, Chakrabarti B, Wheelwright SJ, Auyeung B, et al. Cognition in males and females with autism: similarities and differences. PLoS One 2012; 7: e47198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

PLoS One 2012; 7: e47198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Kirkbride JB, Fearon P, Morgan C, Dazzan P, Morgan K, Tarrant J, et al. Heterogeneity in incidence rates of schizophrenia and other psychotic syndromes: findings from the 3-center AESOP study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63: 250–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd edn). Erlbaum, 1988. [Google Scholar]

20. Green SB, Salkind NJ, Akey T. Using SPSS for Windows: Analyzing and Understanding Data. Prentice-Hall, 1997. [Google Scholar]

21. Tantam D. Lifelong eccentricity and social isolation. I. Psychiatric, social, and forensic aspects. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 153: 777–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Lugnegård T, Hallerbäck MU, Gillberg C. Psychiatric comorbidity in young adults with a clinical diagnosis of Asperger syndrome. Res Dev Disabil 2011; 32: 1910–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Tantam D. Autism Spectrum Disorders through the Life Span. Jessica Kingsley, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Jessica Kingsley, 2012. [Google Scholar]

24. DeLong R. Autism and familial major mood disorder: are they related? J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2004; 16: 199–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Sullivan PF, Magnusson C, Reichenberg A, Boman M, Dalman C, Davidson M, et al. Family history of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder as risk factors for autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012; 69: 1099–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Smalley SL, McCracken J, Tanguay P. Autism, affective disorders, and social phobia. Am J Med Genet 1995; 60: 19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Nuechterlein KH, Dawson ME. A heuristic vulnerability/stress model of schizophrenic episodes. Schizophr Bull 1984; 10: 300–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Happé F, Ronald A. The “fractionable autism triad”: a review of evidence from behavioural, genetic, cognitive and neural research. Neuropsychol Rev 2008; 18: 287–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Tolosa A, Sanjuán J, Dagnall AM, Moltó MD, Herrero N, de Frutos R. FOXP2 gene and language impairment in schizophrenia: association and epigenetic studies. BMC Med Genet 2010; 11: 114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

FOXP2 gene and language impairment in schizophrenia: association and epigenetic studies. BMC Med Genet 2010; 11: 114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Cheniaux E, Landeira-Fernandez J, Versiani M. The diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder and unipolar depression: interrater reliability and congruence between DSM-IV and ICD-10. Psychopathology 2009; 42: 293–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Jones P, Rodgers B, Murray R, Marmot M. Child developmental risk factors for adult schizophrenia in the British 1946 birth cohort. Lancet 1994; 344: 1398–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Hallerback MU, Lugnegard T, Gillberg C. Is autism spectrum disorder common in schizophrenia? Psychiatry Res 2012; 198: 12–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Woodberry KA, Giuliano AJ, Seidman LJ. Premorbid IQ in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165: 579–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Sullivan S, Rai D, Golding J, Zammit S, Steer C. The association between autism spectrum disorder and psychotic experiences in the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children (ALSPAC) birth cohort. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013; 52: 806–14.e2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

The association between autism spectrum disorder and psychotic experiences in the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children (ALSPAC) birth cohort. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013; 52: 806–14.e2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Miller GA, Chapman JP. Misunderstanding analysis of covariance. J Abnorm Psychol 2001; 110: 40–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Holtmann M, Bölte S, Poustka F. Autism spectrum disorders: sex differences in autistic behaviour domains and coexisting psychopathology. Dev Med Child Neurol 2007; 49: 361–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Peralta V, Cuesta MJ. A dimensional and categorical architecture for the classification of psychotic disorders. World Psychiatry 2007; 6: 100–1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Läge D, Egli S, Riedel M, Strauss A, Möller H-J. Combining the categorical and the dimensional perspective in a diagnostic map of psychotic disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2011; 261: 3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Autism and Mental Health | Foundation Exit, autism in Russia

04/04/17

Review of studies on the prevalence and treatment of mental disorders in autism

Source: Autism Speaks

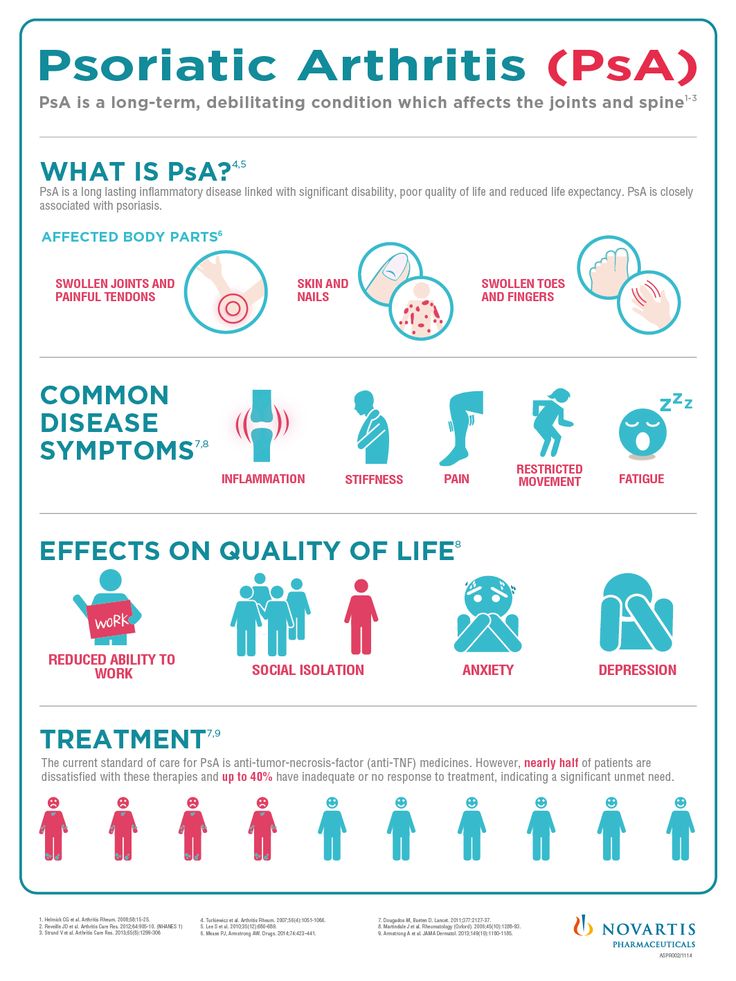

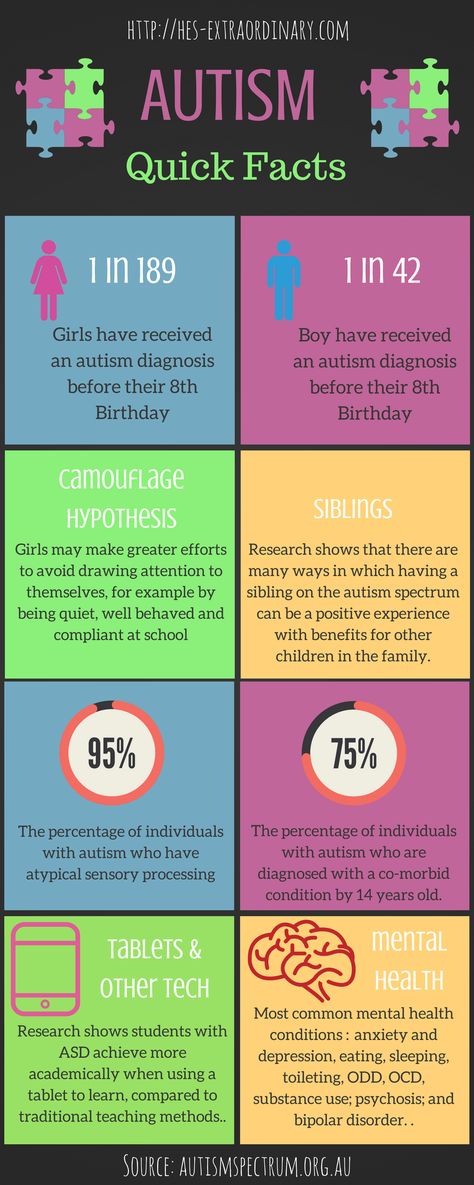

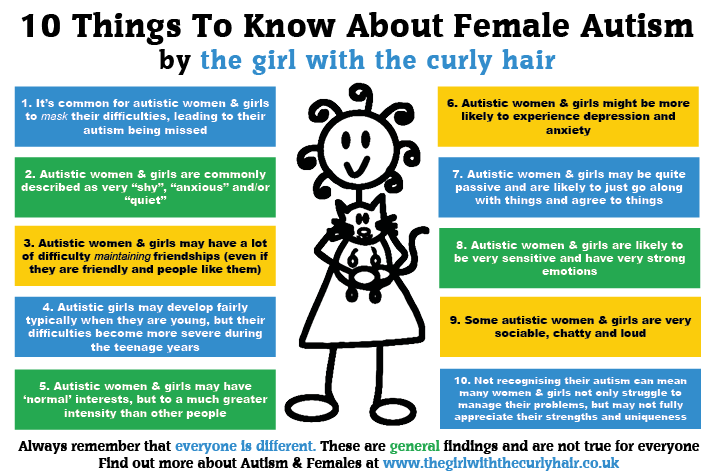

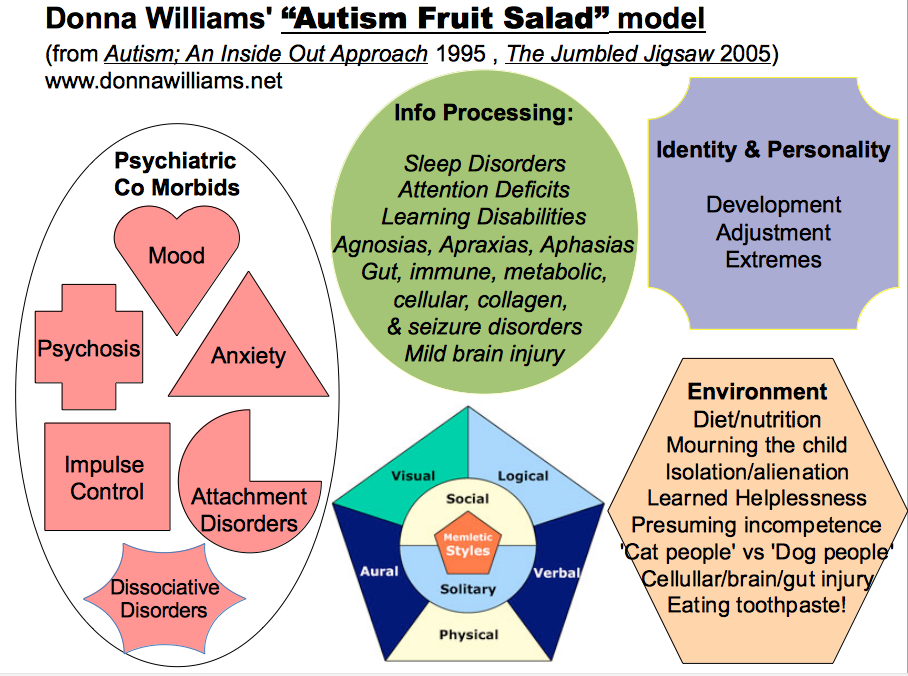

Epidemiological studies suggest that from 54% to 70 to 70 to 70 to 70 to 70 to 70 to 70 to 70 % of people with autism have one or more mental disorders (Simonoff 2008, Hofvander 2009, Croen 2015, Romero 2016).

With regard to their prevalence, the following data currently exist:

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) occurs in 30-61% of people with autism (Goldstein 2004, Lee 2006, Gadow 2006, Romero 2016).

- Anxiety disorders affect 11-42% of people with autism (Vasa 2016, White 2009, Croen 2015, Romero 2016).

- Depression affects 7% of children and 26% of adults with autism (Greenlee 2016, Croen 2015).

- Schizophrenia occurs in 4-35% of adults with autism (Chisolm 2015).

- Bipolar affective disorder occurs in 6-27% of people with autism (Munesue 2008, Rosenberg 2011, Vannucchi 2014, Guinchat 2015, Croen 2015). nine0003

ADHD, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, like autism, are caused by neurobiological features of the brain that are associated with the earliest stages of its development (Munesue 2008, Sikora 2012, Rapoport 2012). As for anxiety disorders and depression, at least in part, they may be related to daily stress, social isolation, and poor overall quality of life among people with autism (Vasa 2016, Greenlee 2016).

Left untreated, psychiatric disorders can lead to a dramatic worsening of behavioral problems in autism. However, due to similar symptoms, the diagnosis of such disorders in autism can be very difficult (Levy 2010, Sikora 2012, Miodovnik 2015). For example, social avoidance in depression or schizophrenia is difficult to distinguish from social interaction disorders associated with autism. In addition, people with autism may find it difficult to identify or express their emotions and other inner experiences. nine0003

Over the past few years, autism specialists have developed guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of some of the most common mental disorders in children, adolescents and adults with autism. The following is an overview of the latest data on this topic.

Autism and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Over the past ten years, studies have shown that 30% to 61% of people with autism also have symptoms of ADHD (Goldstein 2004, Lee 2006, Gadow 2006, Romero 2016). By comparison, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that ADHD occurs in 6-7% of the general population (Perou 2013). nine0003

By comparison, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that ADHD occurs in 6-7% of the general population (Perou 2013). nine0003

In addition, geneticists have discovered that many genetic variations that increase the risk of autism also increase the risk of ADHD (Lionel 2011).

Symptoms of ADHD include consistent problems with inattention, hyperactivity, and/or impulsivity that interfere with daily living, social development, and learning. People with ADHD often find it difficult to pay attention to details and make many mistakes at school or at work through sheer inattention. They often do not seem to hear when spoken to and find it difficult to organize their activities, follow instructions and complete tasks, especially when they require concentration (DSM-5 2013). nine0003

In 2012, a study of ADHD symptoms was conducted among 3,000 autistic patients aged 2 to 18 years (Sikora 2012). Multiple symptoms of ADHD have been found in more than half of children and adolescents with autism. Further evaluation showed that the combination of ADHD and autism results in poorer daily functioning, health, and overall quality of life. At the same time, only a few of these children (11%) received ADHD treatment.

Further evaluation showed that the combination of ADHD and autism results in poorer daily functioning, health, and overall quality of life. At the same time, only a few of these children (11%) received ADHD treatment.

Differentiating autism and ADHD can be especially tricky because both disorders involve social interaction problems and difficulties with attention, learning, and communication. nine0003

In 2012 Pediatrics published the first guidelines for diagnosing ADHD in children and adolescents with autism, along with guidelines for selecting and evaluating ADHD medications for these patients (Mahajan 2012). The guide also provides information about the benefits and side effects of ADHD medications and their dosages in consultation with the family.

The guidelines emphasize that the decision to use drugs is very personal and should be made in consultation with the individual and/or their parents in accordance with their goals and values. nine0003

Autism and anxiety disorders

Research suggests that between 11% and 42% of people with autism suffer from one or more anxiety disorders (Vasa 2016, White 2009, Croen 2015, Romero 2016). By comparison, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 3% of children and 15% of adults in the general population have anxiety disorders (Perou 2013, Kessler 2009). These disorders include parental separation anxiety, panic disorder, and phobias (extremely intense fear of certain sounds, places, and so on). nine0003

By comparison, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 3% of children and 15% of adults in the general population have anxiety disorders (Perou 2013, Kessler 2009). These disorders include parental separation anxiety, panic disorder, and phobias (extremely intense fear of certain sounds, places, and so on). nine0003

Social anxiety—an extreme fear of new people, crowds, and social situations—is very common in children and adults with autism. Many children on the autism spectrum experience an increase in anxiety during adolescence (Bellini 2006). Although there is still very little research in adults with autism, case reports suggest that high levels of anxiety often persist throughout the life of a person with autism (Gillott 2007, Moss 2015).

Even in the absence of an anxiety disorder, many people with autism have trouble controlling their anxiety if something triggers it. For many, anxiety is closely associated with symptoms of autism, especially difficulty in social situations and increased sensory sensitivity to loud noises, lights, tastes or smells. Problems like these can lead to a special form of anxiety where the mere thought or expectation of an anxiety-provoking situation can cause extreme anxiety. nine0003

Problems like these can lead to a special form of anxiety where the mere thought or expectation of an anxiety-provoking situation can cause extreme anxiety. nine0003

Another important source of anxiety for people with autism is their need for routine and sameness. Changes in the daily routine or meeting strangers can cause very strong anxiety, for example, if you suddenly have to deal with a new teacher, a new tutor, or even an unfamiliar salesman.

To date, most research on anxiety in autism has been conducted in verbal children and adults with normal or high intelligence. Experts agree that more research is needed on anxiety among nonverbal or minimally verbal people, which includes one in three people with autism and/or those with an intellectual disability. nine0003

Diagnosis and treatment of anxiety in autism

In 2016, the journal Pediatrics published the first guide to diagnosing and treating anxiety in people with autism (Vasa 2016). Since it is difficult for people with autism to understand and express how they feel, very often the presence of increased anxiety must be determined by behavioral signs. Anxiety can cause severe internal sensations, including increased heart rate, muscle tension, and abdominal pain. For a person with autism, these sensations can cause an increase in repetitive self-soothing behaviors (hand shaking, rocking, spinning, etc.) and/or destructive or self-aggressive behaviors (clothes tearing, head banging on the floor, etc.). Similarly, anxiety can be the reason why a person began to resist and refuse activities that he used to enjoy (going to the beach, birthday party, school, and so on). nine0003

Anxiety can cause severe internal sensations, including increased heart rate, muscle tension, and abdominal pain. For a person with autism, these sensations can cause an increase in repetitive self-soothing behaviors (hand shaking, rocking, spinning, etc.) and/or destructive or self-aggressive behaviors (clothes tearing, head banging on the floor, etc.). Similarly, anxiety can be the reason why a person began to resist and refuse activities that he used to enjoy (going to the beach, birthday party, school, and so on). nine0003

The guidelines call for personalized treatment based on the patient's developmental level, including speech and intellectual development. Data are also provided on the effectiveness of a version of cognitive behavioral therapy adapted for people with autism (Wood 2009, Drahota 2011, Wood 2015). In general, cognitive-behavioral techniques include challenging negative thoughts with logic, role-playing situations, modeling bold behavior, and gradually dealing with fearful situations. Gradual contact can begin by simply looking at a photograph of the situation. A version of psychotherapy adapted for people with autism uses many visual cues that suit the visual learning style of many people with autism. This version also uses the special interests of people with autism to increase their involvement in the psychotherapy process. For example, a therapist might use a child's favorite cartoon character to model how to deal with a fearful situation. Another example is during a therapy session, the therapist takes breaks to talk to the client about a special interest. nine0003

Gradual contact can begin by simply looking at a photograph of the situation. A version of psychotherapy adapted for people with autism uses many visual cues that suit the visual learning style of many people with autism. This version also uses the special interests of people with autism to increase their involvement in the psychotherapy process. For example, a therapist might use a child's favorite cartoon character to model how to deal with a fearful situation. Another example is during a therapy session, the therapist takes breaks to talk to the client about a special interest. nine0003

Some people with autism really enjoy the logical aspects of CBT. In clinical trials, cognitive behavioral therapy has proven effective for verbal people on the autism spectrum with normal to high intelligence (Wood 2009, Wood 2015, Hepburn 2016). Researchers are now working to further modify this approach to suit people with intellectual disabilities and/or speechlessness (Danial 2013). nine0003

Anxiety medications for people with autism

In some cases, counseling and behavioral therapy are not enough to relieve severe anxiety. In these cases, the patient and/or family may consult with a qualified healthcare professional about adding an anti-anxiety medication to the treatment program. There are no medications approved specifically for the treatment of anxiety in children and adults with autism. Autism specialists typically prescribe the same drugs that have been approved for treating anxiety disorders in the general population. These include serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as Prozac and Zoloft. However, some research suggests that anti-anxiety medications may be less effective for people with autism than for other groups (Williams 2010). Perhaps the reason is that the causes of anxiety in autism differ from those in the general population. nine0003

In these cases, the patient and/or family may consult with a qualified healthcare professional about adding an anti-anxiety medication to the treatment program. There are no medications approved specifically for the treatment of anxiety in children and adults with autism. Autism specialists typically prescribe the same drugs that have been approved for treating anxiety disorders in the general population. These include serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as Prozac and Zoloft. However, some research suggests that anti-anxiety medications may be less effective for people with autism than for other groups (Williams 2010). Perhaps the reason is that the causes of anxiety in autism differ from those in the general population. nine0003

Autism and depression

An estimated 7% of children with autism and 26% of adults with autism have depression (Greenlee 2016, Croen 2015). By comparison, 2% of children and 7% of adults in the general population in the US have depression (Perou 2013, NIMH 2015). A recent report in the journal Pediatrics found that rates of depression among children with autism increase rapidly with age, from 5% in elementary grades to over 20% in adolescents (Greenlee 2016). It is assumed that the risk of depression is higher with higher intellectual abilities, as well as with one or more associated medical problems, primarily epilepsy and digestive problems. nine0003

A recent report in the journal Pediatrics found that rates of depression among children with autism increase rapidly with age, from 5% in elementary grades to over 20% in adolescents (Greenlee 2016). It is assumed that the risk of depression is higher with higher intellectual abilities, as well as with one or more associated medical problems, primarily epilepsy and digestive problems. nine0003

The fact that levels of depression increase with age and intellectual ability suggests that painful awareness of social difficulties due to autism and isolation may be the cause of depression, the researchers note. The fact that the level of depression increases with comorbid medical problems suggests how these problems affect the quality of life in autism.

The authors urge healthcare professionals to consider standard screening for symptoms of depression for all adolescents and adults with autism, especially if they have normal or high intelligence or additional medical problems. nine0003

Diagnosis of Depression in Autism

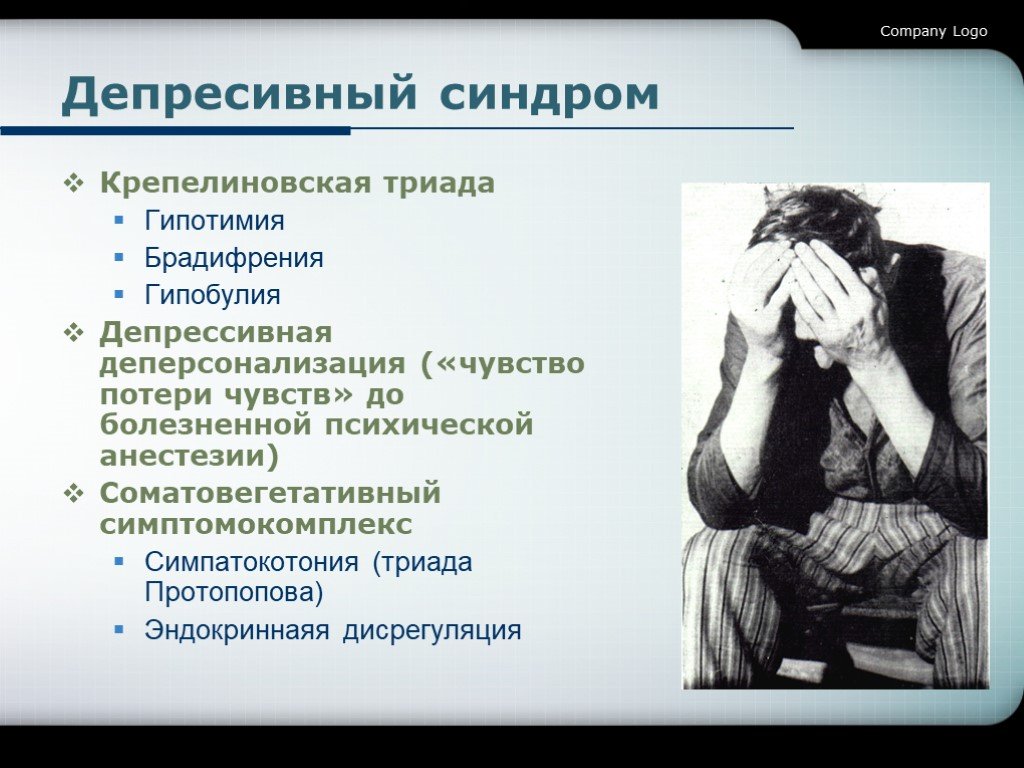

Signs and symptoms of depression include chronic feelings of sadness, hopelessness, worthlessness, inner emptiness and/or irritability. Also common: social isolation, slowness of movement or speech, restlessness, difficulty concentrating or sitting still. In the most severe cases, depression may include frequent thoughts of death and/or suicide.

Also common: social isolation, slowness of movement or speech, restlessness, difficulty concentrating or sitting still. In the most severe cases, depression may include frequent thoughts of death and/or suicide.

However, diagnosing depression in people with autism can be particularly difficult (Gotham 2015). A flat, emotionless facial expression, for example, is characteristic of both autism and depression. The same applies to irritability and social isolation. As a result, it can be difficult to recognize depression behind the manifestations of autism. In addition, many people with autism find it very difficult to identify and express their feelings. For these reasons, autism professionals have begun working to develop and test modified methods for diagnosing depression in children and adolescents on the autism spectrum (Sterling 2015). nine0003

Depression, autism, and suicide

In 2012, researchers at Penn College of Medicine reported that 14% of children with autism under the age of 16 "sometimes" or "very often" thought or attempted suicide—28 times more likely than than children of the same age with typical development (Mayes 2013). The increase in suicidal tendencies becomes significant after 10 years of age, and was most associated with depressive symptoms. Neither the severity of autism nor the level of intelligence affected this level. The authors of the study urge medical professionals to screen all children with autism for suicidal thoughts and attempts, and to inform parents about such risks. nine0003

The increase in suicidal tendencies becomes significant after 10 years of age, and was most associated with depressive symptoms. Neither the severity of autism nor the level of intelligence affected this level. The authors of the study urge medical professionals to screen all children with autism for suicidal thoughts and attempts, and to inform parents about such risks. nine0003

Treating depression in people with autism

Cognitive behavioral therapy may well be successful in treating depression in adolescents and adults with autism (Kuroda 2013). These findings are based on a large body of research on the effectiveness of a modified version of cognitive behavioral therapy for extreme and chronic anxiety in autism.

There are no drugs approved to treat depression specifically in patients with autism, so usually psychiatrists prescribe the same drugs for people with autism as for other patients. However, more research is needed, as a 2011 study suggests that antidepressant side effects are more common among people with autism (Boyd 2011). The most common side effects are drowsiness, nervous agitation, increased irritability, increased motor activity and digestive problems. nine0003

The most common side effects are drowsiness, nervous agitation, increased irritability, increased motor activity and digestive problems. nine0003

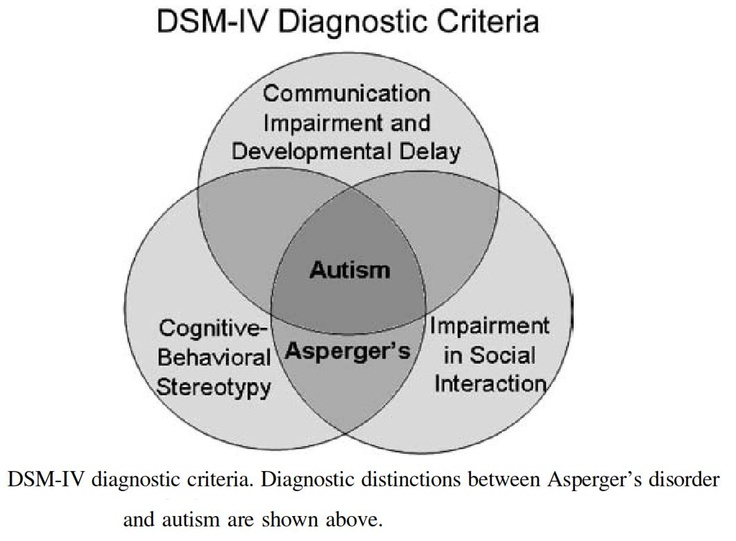

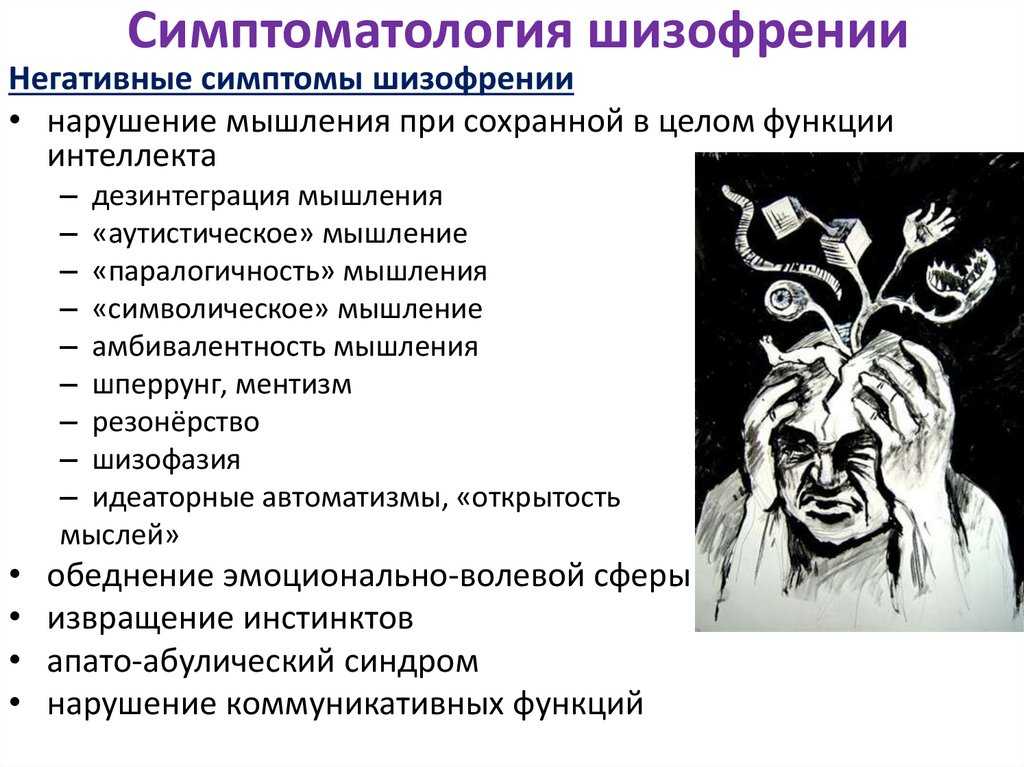

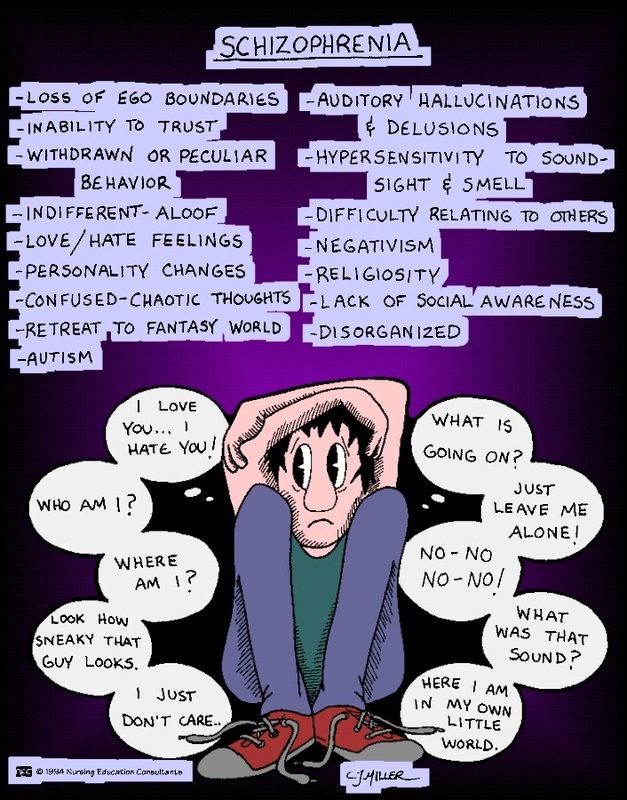

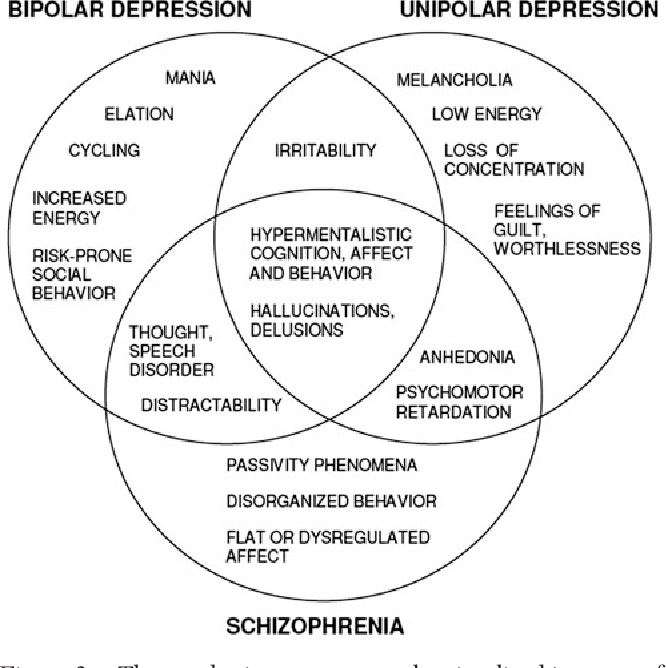

Autism and Schizophrenia

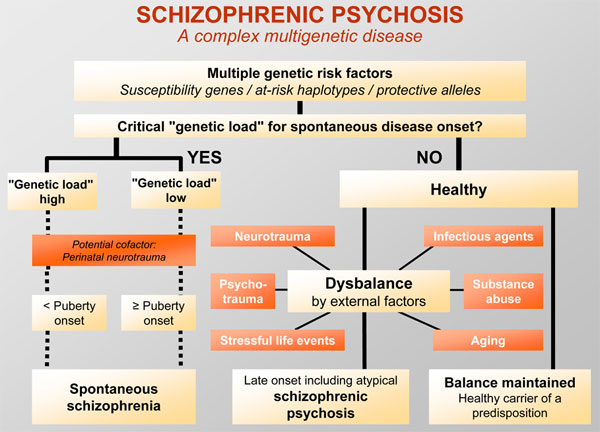

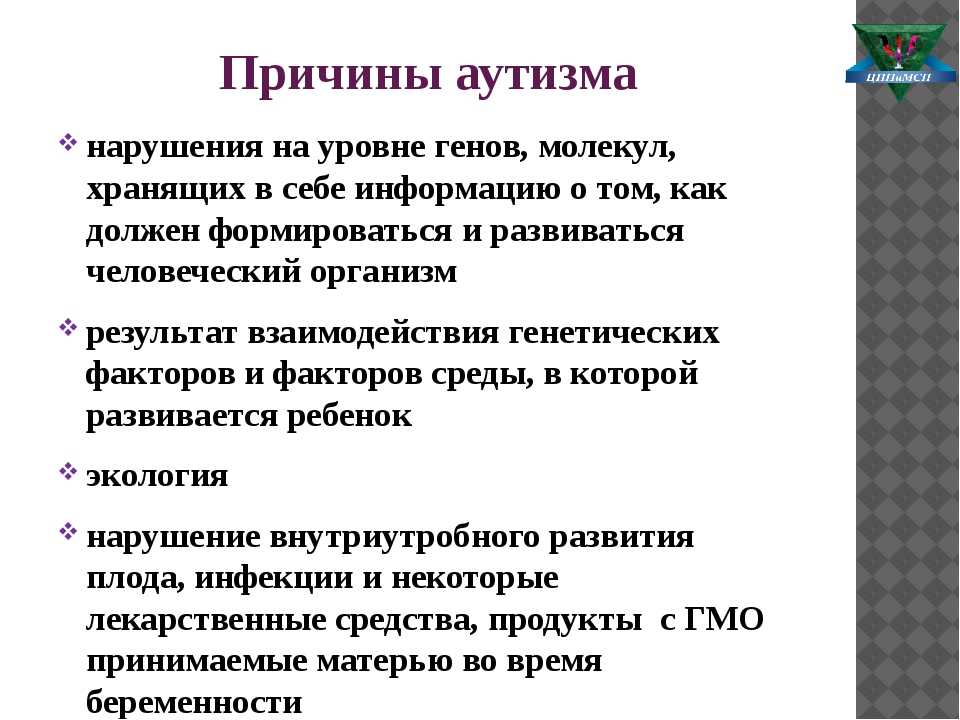

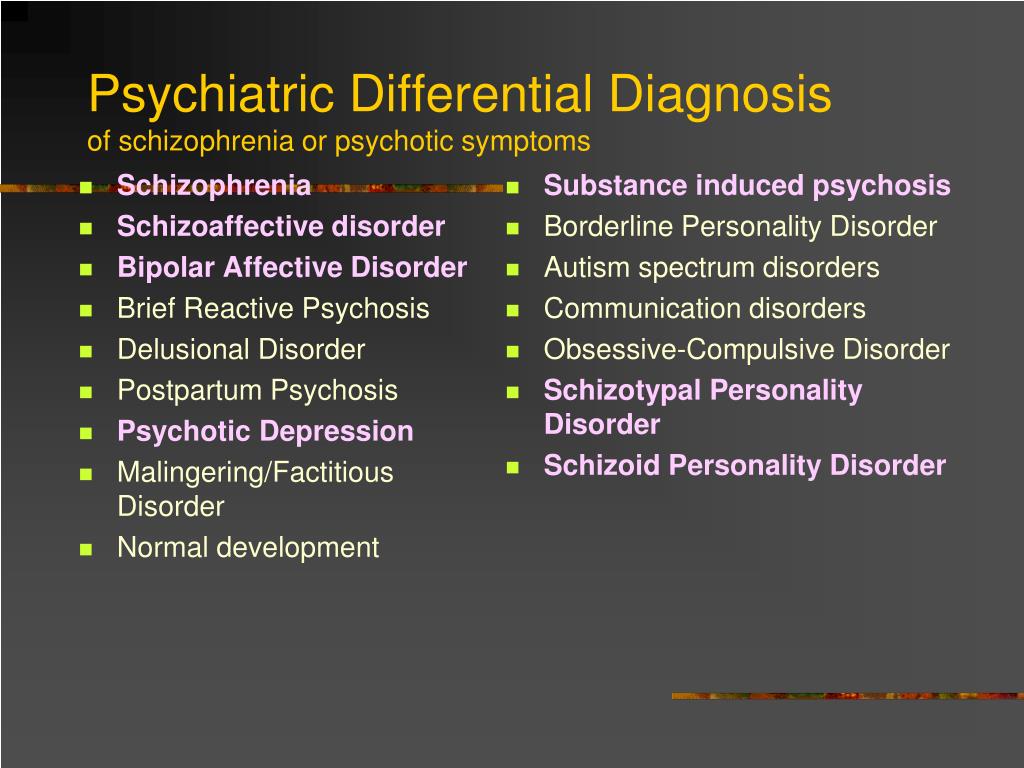

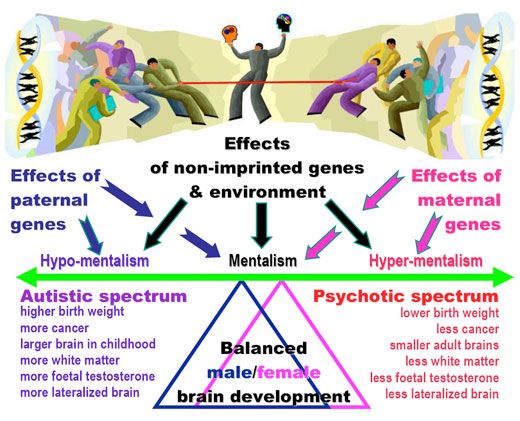

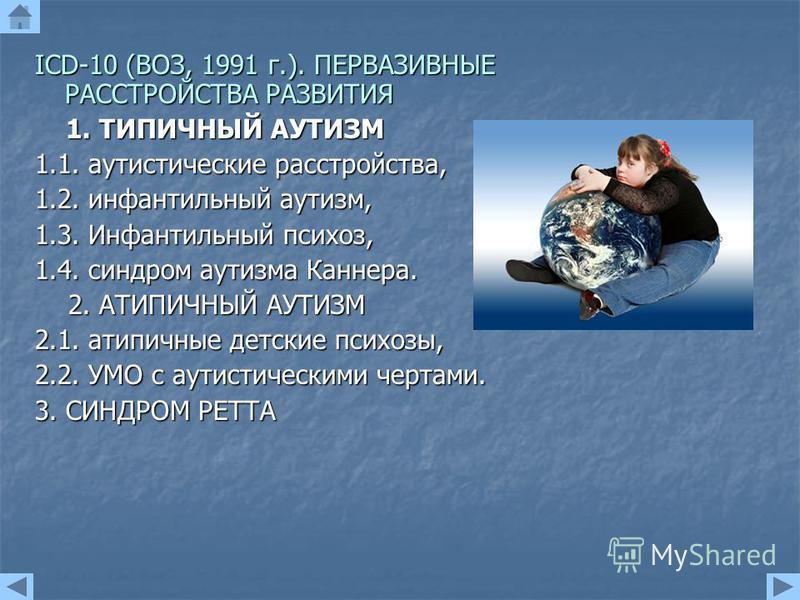

In the 1960s, psychiatrists mistakenly believed that autism was a form of childhood schizophrenia (DSM II 1968). However, by the 1990s, psychiatry had made a clear distinction between these disorders (Rapoport 2009).

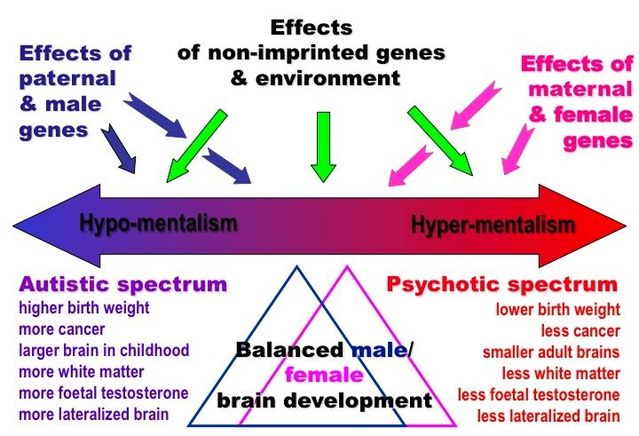

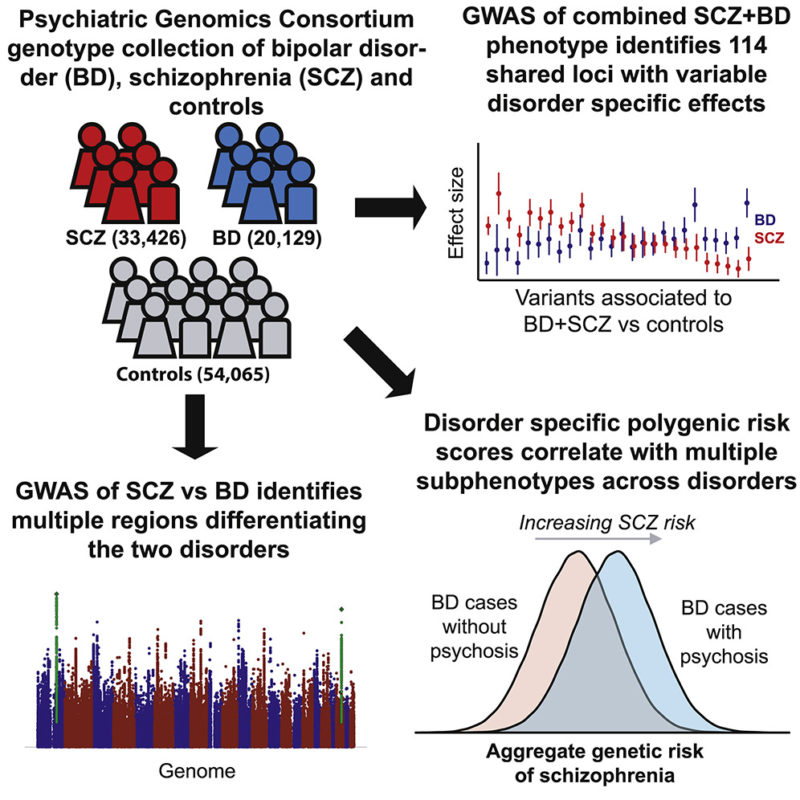

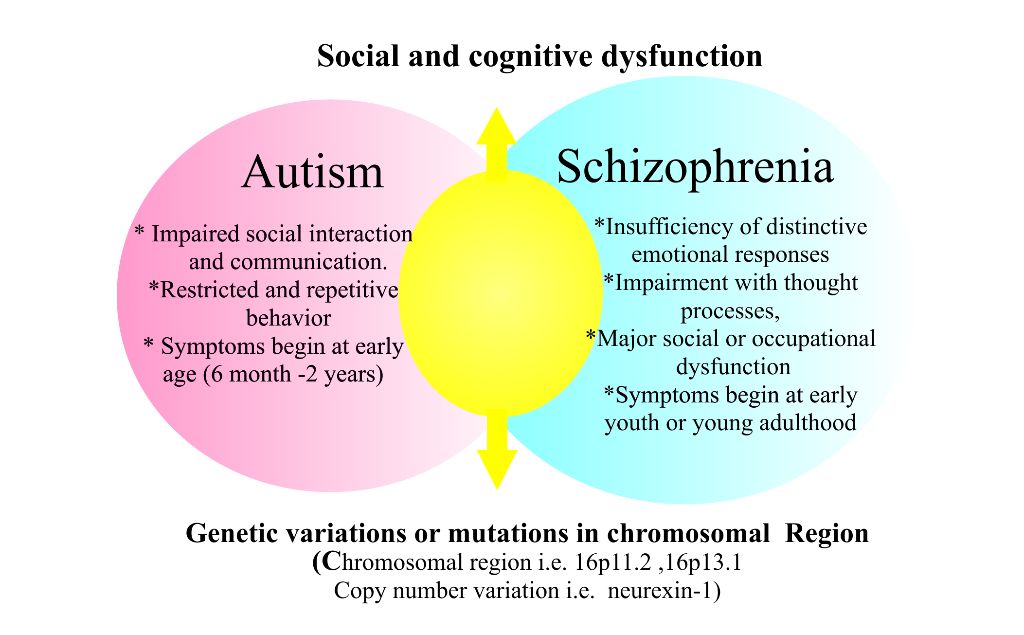

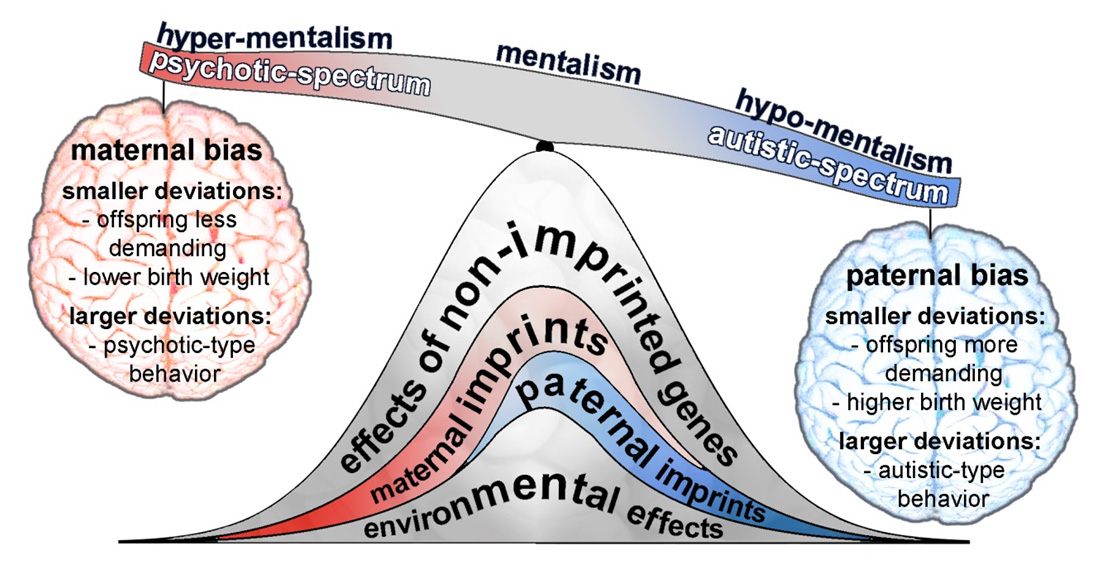

Although autism and schizophrenia are distinct disorders, they share biological characteristics. The roots of both disorders seem to be related to the development of the child's brain even before birth. The same factors are associated with an increased risk of both autism and schizophrenia. These include infectious and inflammatory diseases of the mother during pregnancy, as well as the age of both parents at the time of conception (Patterson 2009, Menon 2011, Insel 2010). Research has also identified many genetic risk factors for both disorders. In other words, there are many genetic variations that can increase the risk of both autism and schizophrenia (Guilmatre 2009, McCarthy 2014).

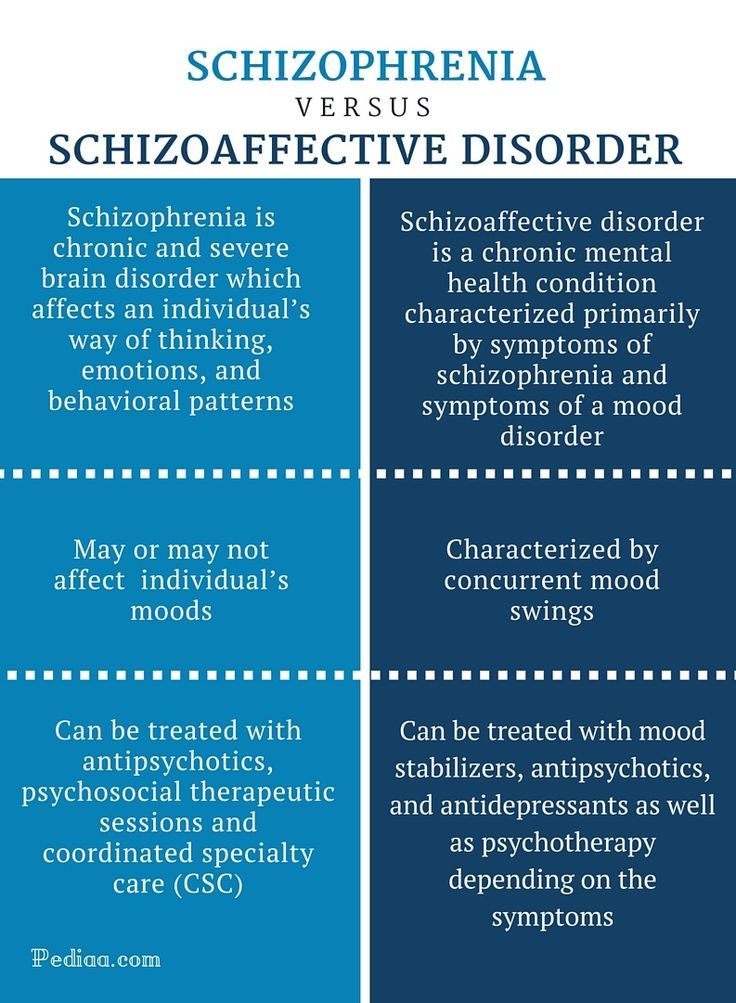

Autism and schizophrenia also have similar symptoms, for example, with both disorders, it can be difficult for a person to understand speech, as well as understand the thoughts and feelings of other people. The most obvious difference between schizophrenia and autism is psychosis, which usually includes hallucinations. In addition, the main symptoms of autism always appear very early - autism can be diagnosed between the ages of 1 and 3 years. The symptoms of schizophrenia usually appear in young adults. nine0003

Many physicians have reported that they have identified previously undiagnosed autism in adults with schizophrenia and vice versa. However, studies on how often autism and schizophrenia coexist have produced conflicting results (Chisolm 2015). Studies have shown that schizophrenia occurs in 4-35% of adults with autism, and that 4-60% of people with schizophrenia have autism. In comparison, schizophrenia occurs in about 1.1% of the general population, and autism occurs in about 1. 5% (NIMH/Regier 1993, Baio 2014).

5% (NIMH/Regier 1993, Baio 2014).

The authors of the studies cited above believe that screening for autism among adults diagnosed with schizophrenia is necessary, and that adolescents and adults with autism should also be monitored for the possible emergence of symptoms of schizophrenia.

Bipolar affective disorder

Bipolar affective disorder is a mood disorder formerly called "manic depressive disorder" or "manic depression". People with bipolar affective disorder may experience periods of agitation called mania and periods of depression. While some people have only episodes of mania, most people with this disorder have alternating states of mania and depression, and they can also be extremely irritable. nine0003

Research shows that children and adults with autism are at increased risk of bipolar disorder (Munesue 2008, Rosenberg 2011, Vannucchi 2014, Guinchat 2015). However, data on the prevalence of this disorder among people with autism vary widely, ranging from 6% to 27%. By comparison, about 4% of the general population has bipolar affective disorder (Kessler 1994).

By comparison, about 4% of the general population has bipolar affective disorder (Kessler 1994).

However, some leading autism experts suggest that bipolar disorder is often misdiagnosed in people with autism. The reason is that autism may be associated with symptoms that resemble bipolar disorder – increased motor activity, irritability, sleep disturbances (Witwer 2014). Experts urge mental health professionals to be careful and try to separate the symptoms of genuine bipolar disorder from those of autism by looking at when the symptoms started and how long they lasted. For example, a child with autism may be very energetic and obsessive during social interactions throughout childhood. In this case, the child's tendency to talk to strangers and make inappropriate comments is consistent with his autism, not symptoms of manic mood swings. nine0003

Treatment of bipolar disorder in autism

Some bipolar medications are problematic and even dangerous to use if the patient has difficulty recognizing and expressing their feelings, which is common in autism. For example, lithium in rare cases can be toxic and even life-threatening. The first signs of such toxicity are increased thirst and trembling. Anticonvulsants that can stabilize mood, such as valproic acid, may be a safer treatment for patients with autism (Witwer 2014). nine0003

For example, lithium in rare cases can be toxic and even life-threatening. The first signs of such toxicity are increased thirst and trembling. Anticonvulsants that can stabilize mood, such as valproic acid, may be a safer treatment for patients with autism (Witwer 2014). nine0003

In addition, antipsychotics such as risperidone and aripiprazole have been approved for the treatment of irritability in children with autism, although both drugs can lead to weight gain and an increased risk of diabetes.

We hope that the information on our website will be useful or interesting for you. You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button.

Psychiatry, Comorbidities

How common are psychiatric disorders in autism

10.10.19

A new study showed that 8 mental health disorders are much more common in people in the Autism spectrum

Source: SPECTRUM News

9000 Scientific Research suggests that eight various mental disorders are much more common in people with autism (1).

Some mental health problems are known to often accompany autism, but estimates of their prevalence among autistic people vary widely (2). (See also: Autism and Mental Health Issues.) nine0003

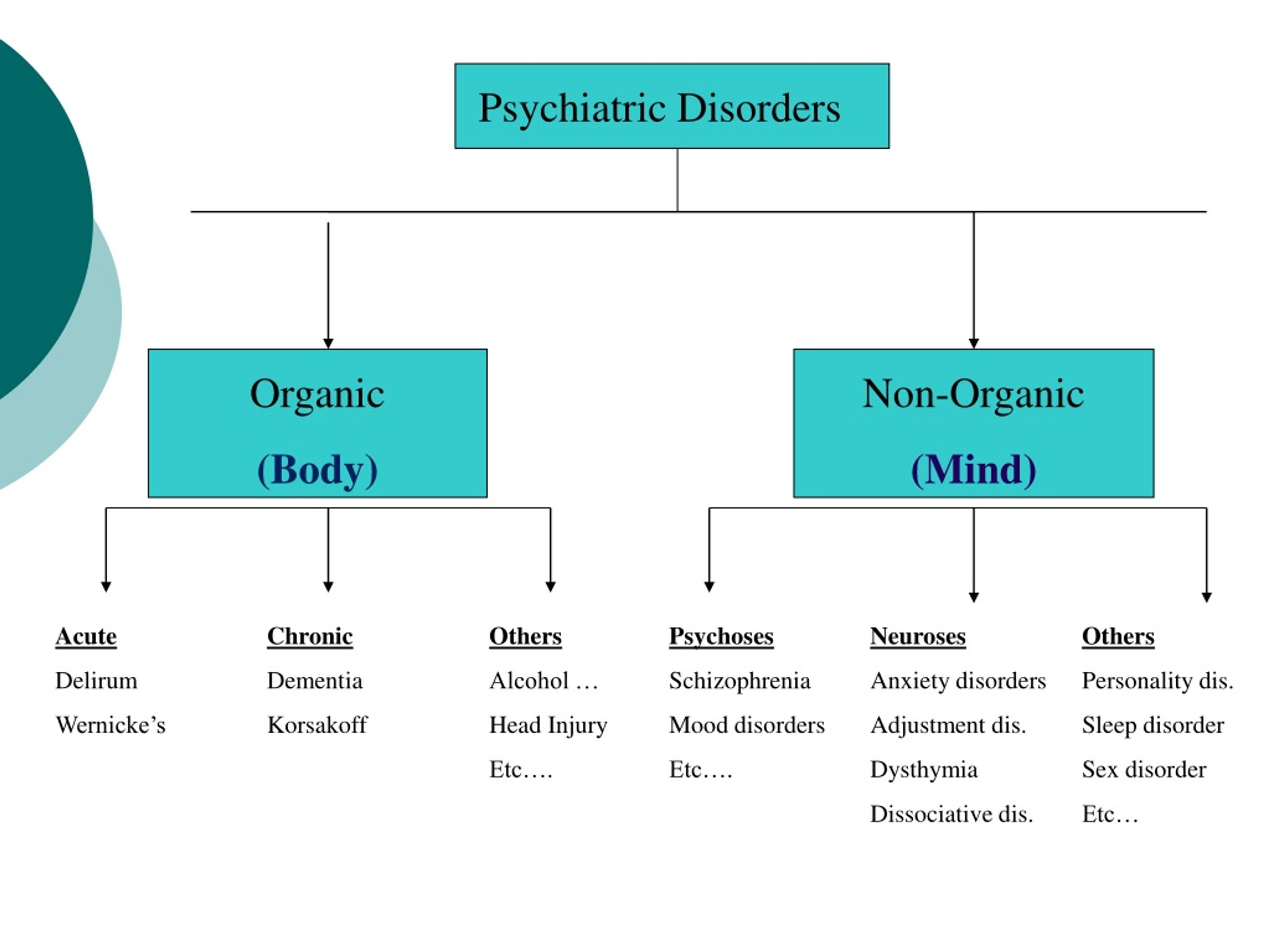

A new study was conducted by pooling and analyzing data from different studies. The authors conducted separate statistical analyzes for various conditions: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety disorders, depression, schizophrenia and psychosis, bipolar affective disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, impulse control and behavior disorders, and sleep and wake disorders.

"This study has provided a more holistic picture of elevated levels of the major and most common psychiatric disorders," says Stephanie Ameis, lead author of the study and professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto in Canada. nine0003

The study also determined that people on the autism spectrum are at increased risk of depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia as they age.

Ameis and colleagues included in their analysis the results of studies of 10,000 people, which were conducted from January 1993 to February 2019, and which included diagnosed mental disorders among people with autism. Studies with 20 or fewer people were excluded from the analysis, as well as studies where the diagnosis was not made according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or the International Classification of Diseases. nine0003

We then excluded from the analysis those studies whose authors asked about the presence of psychiatric disorders during the lifetime, since they did not provide data on the age of diagnosis, the determination of which was one of the objectives of this analysis. As a result, the analysis was carried out on the data of 96 studies. The results were published in the August issue of the Lancet Psychiatry.

The average prevalence of various mental disorders, according to the study, was as follows:

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) occurs in 28% of people on the autism spectrum.