Psychology of patients

Use psychology to improve patient satisfaction

Rebekah Bernard MD

Medical Economics JournalDecember 25, 2018 edition

Volume 95

Issue 24

Doctors can use the psychological techniques of deep listening and emotional validation to help patients feel heard and understood.

Editor's Note: Welcome to Medical Economics' blog section which features contributions from members of the medical community. These blogs are an opportunity for bloggers to engage with readers about a topic that is top of mind, whether it is practice management, experiences with patients, the industry, medicine in general, or healthcare reform. The opinions expressed here are that of the authors and not UBM / Medical Economics.

My last article discussed how psychology can help us to cope with the impact negative patient reviews have on our physician psyche.

Today I will take a more proactive approach and share how we can prevent bad reviews in the first place by using the psychological techniques of deep listening and emotional validation to build empathy and improve patient satisfaction.

Even when we spend a great deal of time with our patients or do something really important for them like making a critical diagnosis, or heck, maybe even saving their lives, patients may leave their visit feeling unsatisfied. This can be intensely frustrating for the us since we try our best to care for the patient and simply cannot understand what went wrong.

More importantly, feeling unable to make patients happy leads to physician burnout. Doctors who receive negative feedback from patients may begin to feel a lack of accomplishment in their work, or a sense that what they are doing doesn’t matter. They may also begin to develop negative feelings towards patients, which can cause cynicism and detachment.

The good news is that there is a simple way to improve patient satisfaction-and in return, to improve our own satisfaction as physicians. And no, it doesn’t mean giving in to every patient demand for antibiotics or pain medications. The key is learning how to help patients feel heard and understood, which we can do using psychology.

And no, it doesn’t mean giving in to every patient demand for antibiotics or pain medications. The key is learning how to help patients feel heard and understood, which we can do using psychology.

What leads to patient dissatisfaction?

The biggest cause of dissatisfaction occurs when patients leave the office without feeling that their doctor really listened to them.

Unfortunately, sometimes doctors unknowingly give that impression to their patients. Although we may be listening, it may not always be obvious to our patients as we click away on the keyboard and scroll through computer screens. And with the increasing demands of EHRs, computerized physician-order entry, and mandatory check-boxes, we can become so distracted by our role as data entry clerks and paper pushers that we sometimes lose our focus.

By bringing our attention back to the patient–at least at the beginning of the visit-we can dramatically improve patient satisfaction. The bonus is that when we focus on building relationships with our patients, we will find that we get the information we need from them more quickly, and our office visits become more efficient.

Show empathy

The key to patient satisfaction is learning how to show empathy-that you understand their concerns, and you care. Most doctors do care about their patients, but not all are naturally good at projecting empathy to make patients feel cared about and understood.

The simplest way to show empathy is to start with a smile. Even if you don’t feel happy, smile anyway. Psychology shows us that emotions are contagious, so when you smile at patients, even a brief smile, they will automatically smile back. This alone will make them feel more welcome and happier.

Next, engage with the patient in a small physical way. Shake hands. Touch them on the shoulder or elbow. This type of expressive touch has been shown to improve interactions between physicians and patients.

Sit down at the same level as the patient and look them in the eye. Spend just a few moments making small talk before you start scrolling around on the computer–this helps to build a bond that may help the patient to open up more quickly when you begin discussing health issues. You can ask about the patient’s family or hobbies, upcoming holiday plans, or even just chat about the weather.

You can ask about the patient’s family or hobbies, upcoming holiday plans, or even just chat about the weather.

When you start to talk about the patient’s medical concerns, really listen to the patient, and demonstrate that you are listening by giving the patient your full and complete attention. This can be very difficult with the EHR–but at least during the patient’s introductory statements, don’t even look at the computer!

As the patient begins to describe concerns or symptoms, avoid interrupting so the patient feels completely heard. Use active listening techniques, such as eye contact, leaning forward, and verbal cues (“yes..,” “go on..” “uh huh..”), to show you are listening. Repeat back what the patient says to you, so to demonstrate you heard and understood what was said.

Now, I know what you are thinking.

“I can’t possibly sit there and listen to everything that the patient has to tell me! I will be there all day!”

First, you may be surprised at how quickly your patient finishes talking if you simply let them talk without interrupting. Studies show that the average patient finishes talking in 92 seconds, and most patients will be done within two minutes.

Studies show that the average patient finishes talking in 92 seconds, and most patients will be done within two minutes.

Also, keep in mind that you don’t have to act today on everything that the patient is telling you. You must simply acknowledge that you have heard the patient’s concerns and say that you understand.

Use emotional mirroring and validation

Imagine you are seeing a patient with a chief complaint of abdominal pain. As you are addressing the abdominal pain, the patient then says: “Oh, by the way, Doctor, I’m also having this really weird pain in my foot.”

If you ignore this “add-on” complaint, even if you cure their main issue of abdominal problem, the patient may go away complaining of that “no-good doctor” who didn’t do anything to help them (because you didn’t deal with their foot pain). On the other hand, if you take the time to deal with their foot pain, now you are running behind for your next patient, who is going to be upset with you. It’s a no-win situation!

It’s a no-win situation!

But there is a solution! You can quickly help the patient feel heard and understood without taking much time by using the psychology technique of emotional mirroring and validation.

Here’s what you do: Simply repeat back the concern that the patient has stated, check for clarification (making it clear that you understand), and show empathy by acknowledging the patient’s concern. Then redirect the patient back to the main problem at hand (in this case, the abdominal pain).

Start by restating the patient’s concern.

Doctor: “You say that you are having a really weird pain in your foot?”

The patient may respond: “Yes, it comes and goes. It’s not there right now, though.”

Again, repeat the patient’s words and ask for clarification.

Doctor: “So, the pain comes and goes, but it’s not there right now, is that right?”

Patient: “Yes, it isn’t bothering me right now.”

Show empathy by validating the patient’s concern.

Doctor: (with an expression of genuine concern) “Pain that comes and goes can be frustrating-I’m sure that must be uncomfortable when it happens. But since your foot is not hurting right now and your stomach is, let’s focus on that area. We can make another appointment to discuss your foot pain.”

The key to this technique is repeating back what the patient says when validating so that they feel heard and understood, even if you don’t act medically on the information offered right at that moment.

Emotional mirroring and validation can be especially useful when dealing with emotionally charged situations or difficult patients, which we will explore more in the next article in this series.

Rebekah Bernard is a family physician and the author of Physician Wellness: The Rock Star Doctor’s Guide. Change Your Thinking, Improve Your Life. She can be reached at her self-titled site, Rebekah Bernard, MD.

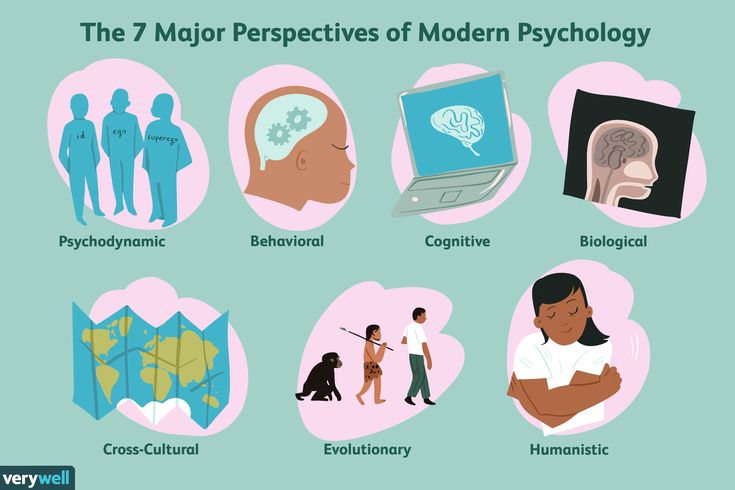

The Importance of Patient Psychology in Health and Clinical Research

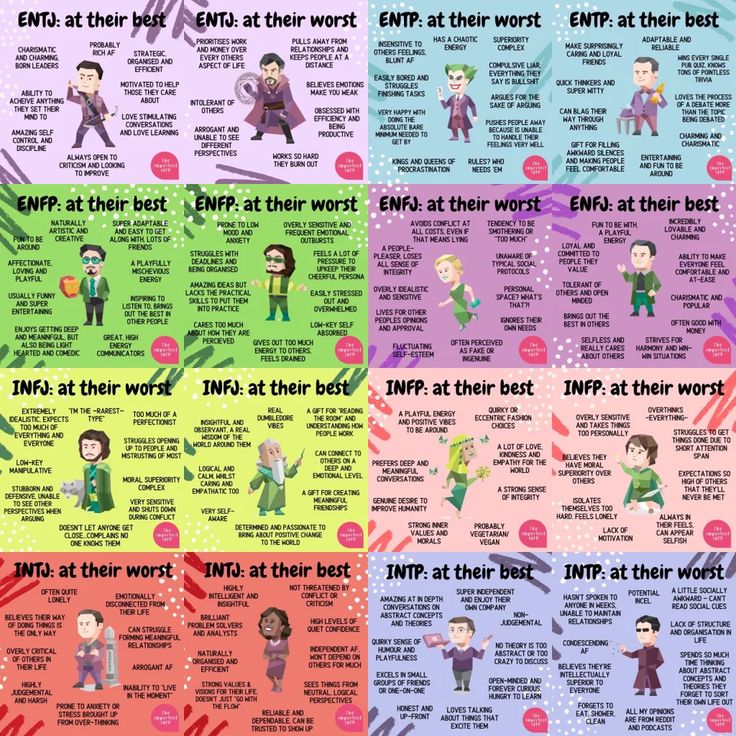

When we think about patient characteristics that influence health, disease, and clinical research, we tend to think about things like vital statistics, medical history and genetic makeup – while patient personality or psychology is often overlooked. In reality, the importance of personality has been under scrutiny for centuries and dates back to Greek and Roman times1. More recently, the emergence of psychoanalysis in the 1950’s led to hypotheses on the connection between the body and the mind. Truly, however, the emergence of the Big Five approach ((extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and intellect/openness) to quantify personality2 has enabled better understanding of the relationship between personality traits and health.

In reality, the importance of personality has been under scrutiny for centuries and dates back to Greek and Roman times1. More recently, the emergence of psychoanalysis in the 1950’s led to hypotheses on the connection between the body and the mind. Truly, however, the emergence of the Big Five approach ((extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and intellect/openness) to quantify personality2 has enabled better understanding of the relationship between personality traits and health.

Several seminal studies have related the Big Five to self-reported mental and physical health. In one study, Big Five traits of conscientiousness and emotional stability were consistently and strongly related to better health3. In other research, longitudinal studies have been conducted to evaluate the relationship between mortality risk and personality traits. Some works have reported that people with higher neuroticism are at higher risk of dying4,5, while the reverse is true for openness6–8.

Another area of interest has been the relationship between response to treatment and personality. For example, in a recent publication, Angela Fang and co-authors showed that patients suffering from body dysmorphic disorder displayed higher levels of neuroticism and lower levels of extraversion than a normed reference group and that higher baseline neuroticism was a significant predictor of nonresponse to escitalopram treatment9. Other studies have shown relationships between personality traits and response to treatments for depression10, substance abuse11, heart disease12 and even tinnitus13.

In reality, this body of research is so broad that it would be impossible to cover it in a simple blog. It does, however, demonstrate that we cannot underestimate the link between who we are and how we react to heatlh disorders, diagnosis, and even treatment.

While these observations were made in “real world” scenarios, similar impacts might be observed when conducting clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of new treatments. The gold standard of drug development involves evaluating treatment efficacy in patients receiving active drug vs. those receiving placebo – and both treatment response and placebo response are inevitably influenced by patient personality. Indeed, extensive research has been conducted on the relationship between placebo response and patient psychological traits. The placebo response clearly varies between patients and is heavily influenced by the patient’s expectations (in terms of drug efficacy and overall well-being) and certain well-defined personality traits14–18. Consequently, the patient-specific nature of the placebo effect may introduce bias and/or variability in randomized clinical trials.

The gold standard of drug development involves evaluating treatment efficacy in patients receiving active drug vs. those receiving placebo – and both treatment response and placebo response are inevitably influenced by patient personality. Indeed, extensive research has been conducted on the relationship between placebo response and patient psychological traits. The placebo response clearly varies between patients and is heavily influenced by the patient’s expectations (in terms of drug efficacy and overall well-being) and certain well-defined personality traits14–18. Consequently, the patient-specific nature of the placebo effect may introduce bias and/or variability in randomized clinical trials.

While the relationship between the placebo response and patient personality has been well-documented in academic settings, capitalizing on this understanding in a way that is applicable and scalable for industry-sponsored clinical trials has proven to be much more difficult. After nearly a decade of research, the Placebell©™ method combined a sophisticated evaluation of key components of patient psychology critical to the placebo response with machine learning to reduce the impact of the placebo response in clinical trials. Now, using Placebell©™, drug developers can quantify patient personality and reduce its contribution to data variability using the covariate approach, thus improving the ability to distinguish treatment efficacy.

After nearly a decade of research, the Placebell©™ method combined a sophisticated evaluation of key components of patient psychology critical to the placebo response with machine learning to reduce the impact of the placebo response in clinical trials. Now, using Placebell©™, drug developers can quantify patient personality and reduce its contribution to data variability using the covariate approach, thus improving the ability to distinguish treatment efficacy.

For more information about how Placebell©™ can improve clinical trial success rates by considering the impact of individual patient psychology, please contact us.

References:

1. Hampson SE. Personality and Health. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology. Published online December 19, 2017. doi:10.1093/ACREFORE/9780190236557.013.121

2. Costa PT, Mccrae RR. The Five-Factor Model, Five-Factor Theory, and Interpersonal Psychology. Handbook of Interpersonal Psychology: Theory, Research, Assessment, and Therapeutic Interventions. Published online March 16, 2012:91-104. doi:10.1002/9781118001868.CH6

Published online March 16, 2012:91-104. doi:10.1002/9781118001868.CH6

3. Goodwin RD, Friedman HS. Health Status and the Five-factor Personality Traits in a Nationally Representative Sample: http://dx.doi.org/101177/1359105306066610. 2016;11(5):643-654. doi:10.1177/1359105306066610

4. Wilson RS, Mendes de Leon CF, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Personality and Mortality in Old Age. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2004;59(3):P110-P116. doi:10.1093/GERONB/59.3.P110

5. Grossardt BR, Bower JH, Geda YE, Colligan RC, Rocca WA. Pessimistic, Anxious, and Depressive Personality Traits Predict All-Cause Mortality: The Mayo Clinic Cohort Study of Personality and Aging. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71(5):491-500. doi:10.1097/PSY.0B013E31819E67DB

6. E F, PA B. Openness to experience and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis and r(equivalent) from risk ratios and odds ratios. British journal of health psychology. 2012;17(1):85-102. doi:10.1111/J.2044-8287.2011.02055.X

2012;17(1):85-102. doi:10.1111/J.2044-8287.2011.02055.X

7. Roberts BW, Kuncel NR, Shiner R, Caspi A, Goldberg LR. The Power of Personality: The Comparative Validity of Personality Traits, Socioeconomic Status, and Cognitive Ability for Predicting Important Life Outcomes: https://doi.org/101111/j1745-6916200700047.x. 2016;2(4):313-345. doi:10.1111/J.1745-6916.2007.00047.X

8. Turiano NA, Chapman BP, Gruenewald TL, Mroczek DK. Personality and the leading behavioral contributors of mortality. Health Psychology. 2015;34(1):51-60. doi:10.1037/HEA0000038

9. Fang A, Porth R, Phillips KA, Wilhelm S. Personality as a Predictor of Treatment Response to Escitalopram in Adults with Body Dysmorphic Disorder. Journal of psychiatric practice. 2019;25(5):347. doi:10.1097/PRA.0000000000000415

10. Kim SY, Stewart R, Bae KY, et al. Influences of the Big Five personality traits on the treatment response and longitudinal course of depression in patients with acute coronary syndrome: A randomised controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2016;203:38-45. doi:10.1016/J.JAD.2016.05.071

Journal of Affective Disorders. 2016;203:38-45. doi:10.1016/J.JAD.2016.05.071

11. Müller SE, Weijers H-G, Böning J, Wiesbeck GA. Personality Traits Predict Treatment Outcome in Alcohol-Dependent Patients. Neuropsychobiology. 2008;57(4):159-164. doi:10.1159/000147469

12. Denollet J, Vaes J, Brutsaert DL. Inadequate Response to Treatment in Coronary Heart Disease. Circulation. 2000;102(6):630-635. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.102.6.630

13. Simões J, Schlee W, Schecklmann M, Langguth B, Farahmand D, Neff P. Big Five Personality Traits are Associated with Tinnitus Improvement Over Time. Scientific Reports 2019 9:1. 2019;9(1):1-9. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53845-4

14. Kern A, Kramm C, Witt CM, Barth J. The influence of personality traits on the placebo/nocebo response: A systematic review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2020;128(March 2019):109866. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.109866

15. Peciña M, Azhar H, Love TM, et al. Personality trait predictors of placebo analgesia and neurobiological correlates. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(4):639-646. doi:10.1038/npp.2012.227

Personality trait predictors of placebo analgesia and neurobiological correlates. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(4):639-646. doi:10.1038/npp.2012.227

16. Jakšic N, Aukst-Margetic B, Jakovljevic M. Does personality play a relevant role in the placebo effect? Psychiatria Danubina. 2013;25(1):17-23.

17. Geers AL, Helfer SG, Kosbab K, Weiland PE, Landry SJ. Reconsidering the role of personality in placebo effects: Dispositional optimism, situational expectations, and the placebo response. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2005;58(2):121-127. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.08.011

18. Corsi N, Colloca L. Placebo and Nocebo Effects: The Advantage of Measuring Expectations and Psychological Factors. Frontiers in Psychology. 2017;8(MAR):308. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00308

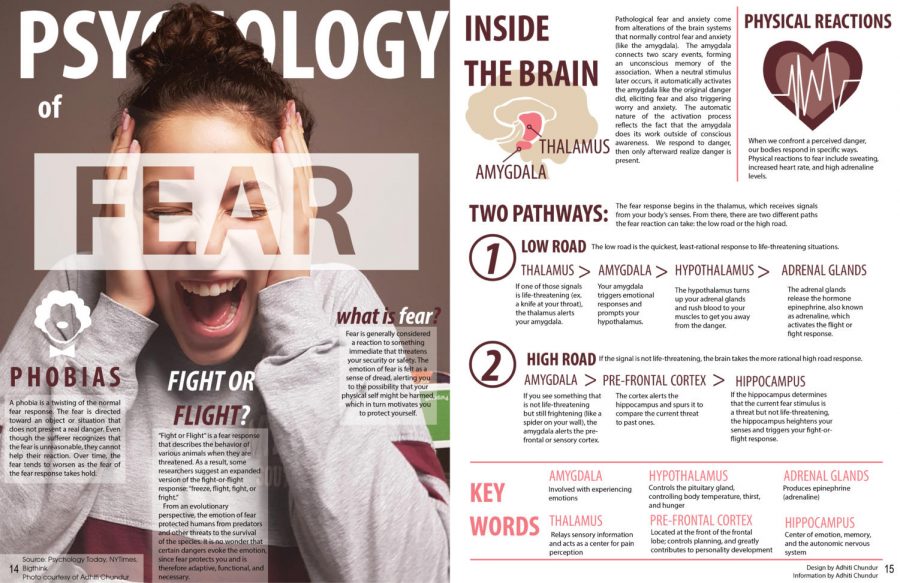

Psychological reactions of the patient to illness

Psychological consultations for oncologists, anonymity is maintained

Phone: 8-800 100-0191

(call within Russia is free, consultation is available around the clock)

The reflection of the disease in a person's experiences is usually defined by the concept of the internal picture of the disease (VKB). It was introduced by the domestic therapist R.A. Luria is still widely used in medical psychology. This concept, according to the definition of the scientist, combines everything “that the patient feels and experiences, the whole mass of his sensations, his general well-being, self-observation, his ideas about his illness, about its causes - all that huge world of the patient, which consists of very complex combinations of perception and sensation, emotions, affects, conflicts, mental experiences and traumas.

It was introduced by the domestic therapist R.A. Luria is still widely used in medical psychology. This concept, according to the definition of the scientist, combines everything “that the patient feels and experiences, the whole mass of his sensations, his general well-being, self-observation, his ideas about his illness, about its causes - all that huge world of the patient, which consists of very complex combinations of perception and sensation, emotions, affects, conflicts, mental experiences and traumas.

As a complex structured formation, the internal picture of the disease includes several levels: sensitive, emotional, intellectual, volitional, rational. VKB is determined not by a nosological unit, but by a person's personality, it is also individual and dynamic, like the inner world of each of us. At the same time, there are a number of studies that reveal the characteristic features of the patient's experience of his condition.

Thus, the concept of V. D. Mendelevich ("Terminological foundations of phenomenological diagnostics") is the idea that the type of response to a particular disease is determined by two characteristics: the objective severity of the disease (determined by the criterion of mortality and the likelihood of disability) and the subjective severity of the disease (the patient's own assessment of his condition).

D. Mendelevich ("Terminological foundations of phenomenological diagnostics") is the idea that the type of response to a particular disease is determined by two characteristics: the objective severity of the disease (determined by the criterion of mortality and the likelihood of disability) and the subjective severity of the disease (the patient's own assessment of his condition).

The idea of the subjective severity of the disease is made up of social and constitutional characteristics, which include sex, age and profession of the individual. Each age group has its own register of the severity of the disease - a kind of distribution of diseases according to socio-psychological significance and severity.

So, in adolescence, the most severe psychological reactions can be caused not by those diseases that are objectively threatening the safety of the body from a medical point of view, but by those that change its appearance, make it unattractive. This is due to the existence in the mind of a teenager of a basic need - "satisfaction with one's own appearance."

This is due to the existence in the mind of a teenager of a basic need - "satisfaction with one's own appearance."

Persons of mature age will react more psychologically to chronic and disabling diseases. “This is connected with the value system and reflects the aspiration of a person of mature age to satisfy such social needs as the need for well-being, well-being, independence, self-sufficiency, etc.” In this respect, the strongest experiences are associated with oncological diseases. For the elderly and the elderly, the most significant are diseases that can lead to death, loss of work and performance.

Individual psychological characteristics that influence the specifics of experiencing a disease include temperamental features (in relation to the following criteria: emotionality, pain tolerance as a sign of emotionality, and restrictions on movements and immobility), as well as features of a person’s character, his personality (ideological attitudes, level of education).

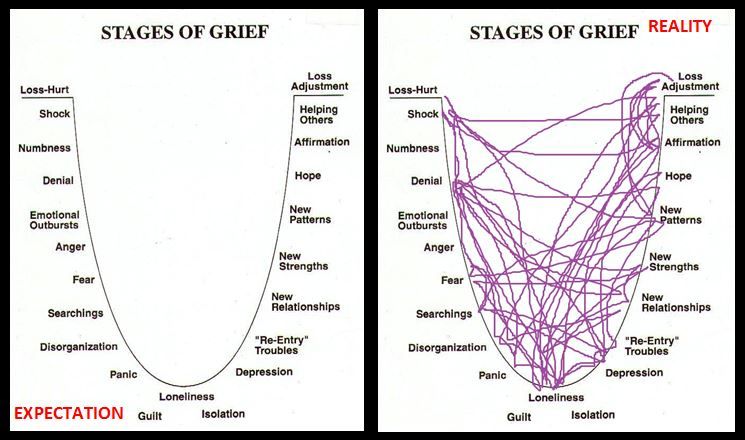

There is a typology of how a patient responds to an illness. Knowing the type of patient's response helps to choose an adequate strategy for interacting with him and his family, to use appropriate methods of communication, motivation for treatment.

Types of psychological response to a severe somatic illness

Typology of response to illness A.E.Lichko and N.Ya. Ivanova (“Medical and psychological examination of somatic patients”) includes 13 types of psychological response to a disease, identified on the basis of an assessment of the influence of three factors: the nature of the somatic disease itself, the type of personality in which the most important component determines the type of character accentuation and attitude to this disease in the reference (significant) group for the patient.

In the first block there are those types of attitude to the disease in which there is no significant adaptation disorder: light, but without underestimating the severity of the disease. The desire to actively contribute to the success of treatment in everything. Unwillingness to burden others with the burdens of self-care. In the case of an unfavorable prognosis in the sense of disability - switching interests to those areas of life that will remain available to the patient. With an unfavorable prognosis, attention, worries, and interests are concentrated on the fate of loved ones, their business.

The desire to actively contribute to the success of treatment in everything. Unwillingness to burden others with the burdens of self-care. In the case of an unfavorable prognosis in the sense of disability - switching interests to those areas of life that will remain available to the patient. With an unfavorable prognosis, attention, worries, and interests are concentrated on the fate of loved ones, their business.

Refusal of examination and treatment, the desire to manage their own means.

Refusal of examination and treatment, the desire to manage their own means. The second block includes types of response to the disease, characterized by the presence of mental maladaptation:

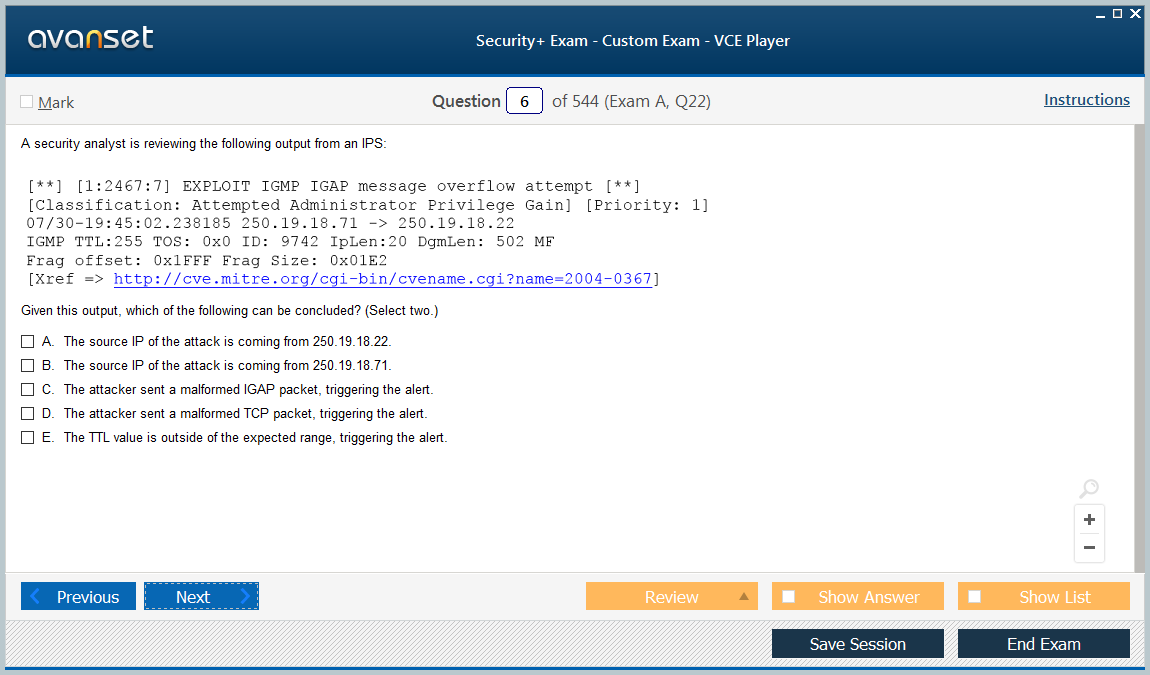

- Anxious : for this type of response, continuous anxiety and suspiciousness regarding the unfavorable course of the disease, possible complications, inefficiency and even the danger of treatment. The search for new methods of treatment, the thirst for additional information about the disease, possible complications, methods of treatment, the continuous search for "authorities". Unlike hypochondria, more interested in objective data about the disease (test results, expert opinions) than their own feelings. Therefore, they prefer to listen more to the statements of others than to endlessly present their complaints. The mood is primarily anxious, depression - as a result of this anxiety).

- Hypochondriacal : focus on subjective painful and other unpleasant sensations.

The desire to constantly talk about them to others. On their basis, the exaggeration of the real and the search for non-existent diseases and suffering. Exaggeration of the side effects of drugs. A combination of desire to be treated and disbelief in success, demands for a thorough examination and fear of harm and painful procedures).

The desire to constantly talk about them to others. On their basis, the exaggeration of the real and the search for non-existent diseases and suffering. Exaggeration of the side effects of drugs. A combination of desire to be treated and disbelief in success, demands for a thorough examination and fear of harm and painful procedures). - Neurasthenic : behavior of the "irritable weakness" type is characteristic. Outbursts of irritation, especially with pain, with discomfort, with treatment failures, adverse examination data. Irritation often pours out on the first person who comes across and often ends with repentance and tears. Pain intolerance. Impatience. Inability to wait for relief. Subsequently - repentance for anxiety and incontinence.

- Melancholic : characterized by depression by the disease, disbelief in recovery, in a possible improvement, in the effect of treatment. Active depressive statements up to suicidal thoughts.

A pessimistic view of everything around, disbelief in the success of treatment even with favorable objective data.

A pessimistic view of everything around, disbelief in the success of treatment even with favorable objective data. - Euphoric : characterized by unreasonably elevated mood, often feigned. Neglect, frivolous attitude to the disease and treatment. Hope that "it will work itself out". The desire to get everything from life, despite the disease. Ease of violation of the regime, although these violations may adversely affect the course of the disease.

- Apathetic : characterized by complete indifference to one's fate, to the outcome of the disease, to the results of treatment. Passive obedience to procedures and treatment with persistent prompting from the outside, loss of interest in everything that previously worried.

- Obsessive-phobic : characterized by anxious suspiciousness primarily concerns fears of not real, but unlikely complications of the disease, treatment failures, as well as possible (but poorly justified) failures in life, work, family situation due to the disease.

Imaginary dangers are more exciting than real ones. Signs and rituals become protection from anxiety.

Imaginary dangers are more exciting than real ones. Signs and rituals become protection from anxiety. - Sensitive : characterized by excessive concern about the possible adverse impression that knowledge of one's illness may make on others. Fear that others will avoid, consider inferior, dismissive or wary, spread gossip or unfavorable information about the cause and nature of the disease. Fear of becoming a burden for loved ones due to illness and hostility on their part in connection with this.

- Egocentric : "Departure into illness" is characteristic, showing off one's sufferings and experiences to relatives and others in order to completely capture their attention. The requirement of exceptional care - everyone should forget and drop everything and take care only of the sick. The conversations of others are quickly translated "on themselves". In others, who also require attention and care, they see only "competitors" and treat them with hostility.

Constant desire to show his special position, his exclusivity in relation to the disease.

Constant desire to show his special position, his exclusivity in relation to the disease. - Paranoid : characterized by the belief that the disease is the result of someone's malicious intent. Extreme suspicion of drugs and procedures. The desire to attribute possible complications of treatment and side effects of drugs to the negligence or malice of doctors and staff. Accusations and demands for punishments in connection with this.

- Dysphoric (characteristically sad and embittered mood).

Interaction with some of these patients can bring significant psychological discomfort to the physician. But knowing the psychological foundations of this type of patient behavior will help the doctor better understand his needs, expectations, fears and emotional reactions, optimally organize the process of interaction with him, and use certain tools of influence. It is important to understand that, even while demonstrating complete indifference to the outcome of treatment, the patient most of all wants to hear words of hope and needs to strengthen his faith in the best. Patients who are constantly worried about their condition need a calm, optimistic and attentive conversation with the doctor, and patients who demonstrate reactions of aggression towards others and the doctor need an authoritative confident position of the doctor, which will help to cope with the strongest fear hidden in the soul for their lives.

Patients who are constantly worried about their condition need a calm, optimistic and attentive conversation with the doctor, and patients who demonstrate reactions of aggression towards others and the doctor need an authoritative confident position of the doctor, which will help to cope with the strongest fear hidden in the soul for their lives.

Thus, understanding the type of patient's response to the disease will help to make the relationship between the doctor and the patient more effective, contributing to the psychological well-being of both participants in the treatment process.

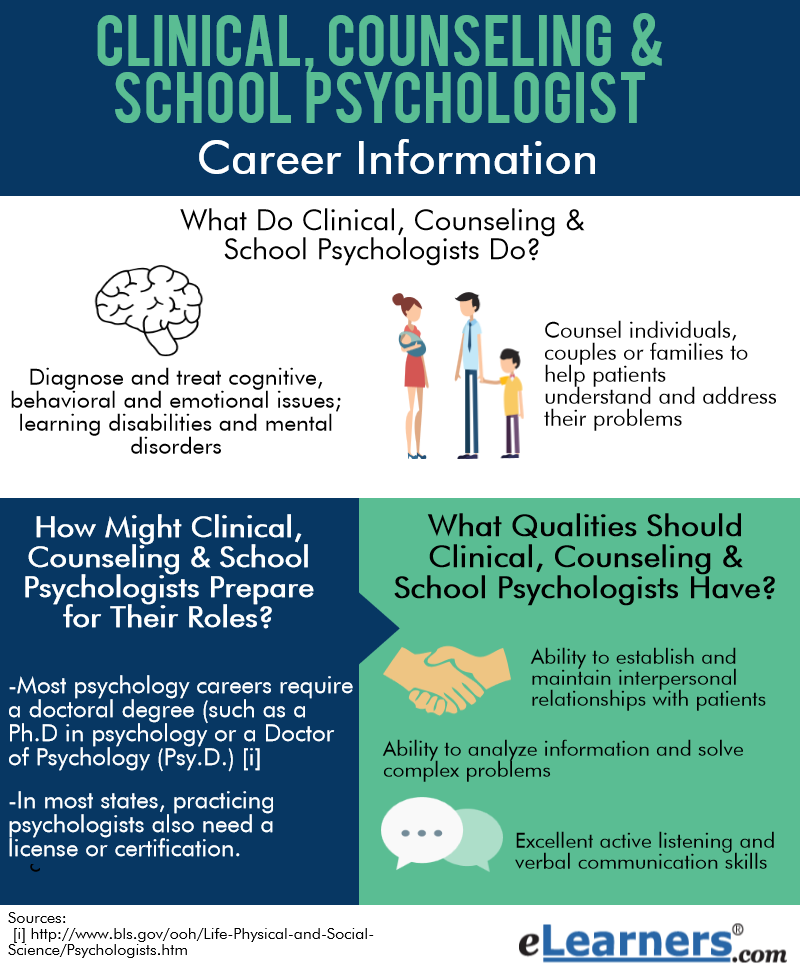

Psychology of the doctor-patient relationship - how to interact with the patient?

Article

January 19, 2021

6451

Listen to audio materials Download audio materials

Article

January 19, 2021

6451

Listen to audio materials Download audio materials

- All specialties

The doctor can cause rather multifaceted reactions in the patient. The hope for recovery and trust in professionalism usually dominate. Depending on the personality characteristics of a person, there may also be sympathy or antipathy, respect, a thirst for attention, a desire for human communication, etc. The success of contact with the patient depends on whether the doctor can correctly interpret these emotions, which ultimately affects the success of treatment.

The hope for recovery and trust in professionalism usually dominate. Depending on the personality characteristics of a person, there may also be sympathy or antipathy, respect, a thirst for attention, a desire for human communication, etc. The success of contact with the patient depends on whether the doctor can correctly interpret these emotions, which ultimately affects the success of treatment.

How to talk to a patient?

In psychology, it is customary to divide people according to the dominant type of perception of information into visuals, auditory and kinesthetics. This classification also helps in the understanding of patients, since the leading receptive system has a significant influence on the behavior of a person in the doctor's office.

Visuals . These are people who perceive most of the information with the help of vision. If a patient begins his speech with the words "You see, doctor ...", "Can you imagine .. ." and uses a description of visual images in his story, his leading receptive system is visual. For such people, it is extremely important that the information is in their field of vision. They can explain the essence of their disease with the help of illustrations, diagrams. When talking about the expected results of treatment, it is worth starting with the words “You will see ...”, “Pay attention to ...”, directly appealing to the patient’s leading organ of perception.

." and uses a description of visual images in his story, his leading receptive system is visual. For such people, it is extremely important that the information is in their field of vision. They can explain the essence of their disease with the help of illustrations, diagrams. When talking about the expected results of treatment, it is worth starting with the words “You will see ...”, “Pay attention to ...”, directly appealing to the patient’s leading organ of perception.

Audials. In this type of patient, the leading receptive system is hearing. They often turn to the interlocutor: "Listen ...", have a clear and measured speech with consistently and logically stated thoughts, and listening, sometimes involuntarily move their lips, following the speech of the doctor. With such patients, you need to speak expressively, explaining the details. When starting a response speech, it is useful to paraphrase the words of the patient: "I heard what you said ...".

Kinesthetics. The instrument of perception of these people is their own body. They are usually very emotional, have a rich supply of gestures to express their emotions. Kinesthetic people love humor and beautiful metaphors, so when explaining their condition, you can give vivid examples, appealing to their imagination. They rely more on intuition than logic and are very good at feeling other people's emotions.

The instrument of perception of these people is their own body. They are usually very emotional, have a rich supply of gestures to express their emotions. Kinesthetic people love humor and beautiful metaphors, so when explaining their condition, you can give vivid examples, appealing to their imagination. They rely more on intuition than logic and are very good at feeling other people's emotions.

How to treat a patient?

The medical profession implies empathy for the patient. This ability in medical psychology is called empathy. It is important for a physician to learn to be able to empathize, but at the same time not to cross the line beyond which experiences become personal.

Lack of empathy. A doctor who does not have empathy does not inspire confidence in patients. They may perceive him as cold, soulless, try to limit communication, which may adversely affect the results of therapy.

Excessive empathy. An overly sympathetic doctor may take on an extra load of emotions, taking problems to heart, spending a lot of time listening to complaints. Patients, seeing the excessive emotionality of the doctor, may subconsciously begin to exaggerate their problems, enjoying the sympathy they receive.

An overly sympathetic doctor may take on an extra load of emotions, taking problems to heart, spending a lot of time listening to complaints. Patients, seeing the excessive emotionality of the doctor, may subconsciously begin to exaggerate their problems, enjoying the sympathy they receive.

Fake empathy. Sometimes the doctor forces himself to show emotions to the patient, the result is insincere empathy. Lack of empathy is normal. The doctor is an ordinary person and cannot sincerely empathize with everyone. In such cases, it is enough to show a readiness for empathy, starting with the words: “Yes, I understand you ...”

How to resist patient manipulation?

According to experts in the field of clinical psychology, manipulation plays an important role in the relationship between a patient and a doctor. This type of behavior is most often characteristic of older patients who, due to their life experience, believe that they know about their disease better than a doctor. They want to get certain prescriptions from the doctor and with the help of manipulation they try to achieve this, focusing on the necessary symptoms and exaggerating their severity.

They want to get certain prescriptions from the doctor and with the help of manipulation they try to achieve this, focusing on the necessary symptoms and exaggerating their severity.

Signs of manipulation are not always easy to recognize. What betrays the patient most of all is the insistent tone of the narration and the pause during which he expects the doctor to do what the manipulator wants. If this does not happen, the patient repeats his arguments, increasing the pressure. Feeling this, it is advisable for the doctor to stop the dialogue, enter the data into the card, analyze the situation and make a decision on appointments based on their own reasoning.

How to overcome the patient's resistance?

Another common problem described by clinical psychologists is resistance. In this case, the patient, for some reason, resists the tactics of therapy chosen by the specialist. Reasons for resistance in patients may be different:

- Disagreement with the prescribed treatment.

This usually occurs when a person exaggerates the severity of their illness, believing that the prescribed treatment is not serious enough. There are doubts about the competence of the doctor.

This usually occurs when a person exaggerates the severity of their illness, believing that the prescribed treatment is not serious enough. There are doubts about the competence of the doctor.

- Own opinion. Some patients, already coming to the doctor, know which appointment they want to receive. If the doctor prescribed something else, they subconsciously want the therapy to be ineffective in order to prove the doctor's mistake. Such a patient may insist that he has become worse because of the medication he is taking, even if there is a positive trend.

- Prejudice. Today, when the topics of medicine are widely discussed in the press, on television, on the Internet, patients often find somewhere information about the dangers of certain drugs or procedures. A biased attitude towards the method of treatment chosen by the doctor can have a negative impact on the attitude towards the specialist himself.

- Unwillingness to get well.

This feeling can arise in different situations - someone wants to continue to be taken care of, someone does not want to go to work. Such people diligently convince themselves of poor health and themselves believe in it. The physician may be misled by this false feeling of being unwell.

This feeling can arise in different situations - someone wants to continue to be taken care of, someone does not want to go to work. Such people diligently convince themselves of poor health and themselves believe in it. The physician may be misled by this false feeling of being unwell.

All these people have one thing in common - resistance, which is expressed in the lack of cooperation with the doctor. This is a rather complex situation, which is not easy to reverse. In such cases, it is advisable to resort to the help of colleagues - to organize a consultation, a consultation with a related specialist, to get a second medical opinion. This usually helps to convince the patient of the correctness of the decision of the attending physician and provides the basis for the formation of a trusting doctor-patient relationship.

If you use any other life hacks, we will be happy to read them in the comments to the material.

What's in this article

You may be interested

The function of the intestinal microbiota in children

Current events

There is increasing evidence of the role of the intestinal microflora in the development of the immune and nervous systems in children. In this text, we discuss the main conclusions reached by scientists.

Can a doctor refuse a patient? Legal aspects of the issue

Everyday life of a doctor

In some cases, the doctor has the right to refuse a patient. In this text, we understand what reasons we are talking about

Read articleCognitive impairment in patients with arterial hypertension

Actual

In this article, we understand how arterial hypertension affects cognitive functions and what preventive measures a doctor can take to prevent dementia.

Read articleLiver comorbidities

Topical

Some comorbidities are not obvious but cannot be excluded in case management. This also applies to patients with various chronic liver diseases. We show the main connections and their features on the infographic.

History of combined oral contraceptives

Current

Only a century ago, we did not know how to effectively control the birth rate. The invention of combined oral contraceptives (COCs) helped to correct the situation. Let's tell how it was.

Read articleAsthma and COPD: how to treat?

Current

This year, GINA and GOLD updated their guidelines for the management of patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Read articleWhat to do if postmenopausal hormone therapy is contraindicated?

Topical

For some women, the symptoms of menopause become a problem forcing them to see a doctor.

Read articleThe health benefits of the Mediterranean diet

Educational program

What is the essence of the Mediterranean diet, what effect does it have on various aspects of health and which patients should be recommended it?

Read articleQuiz: Difficult patient

Actual

A difficult patient has come to your appointment.