Projection psychology meaning

Projection | Psychology Today

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

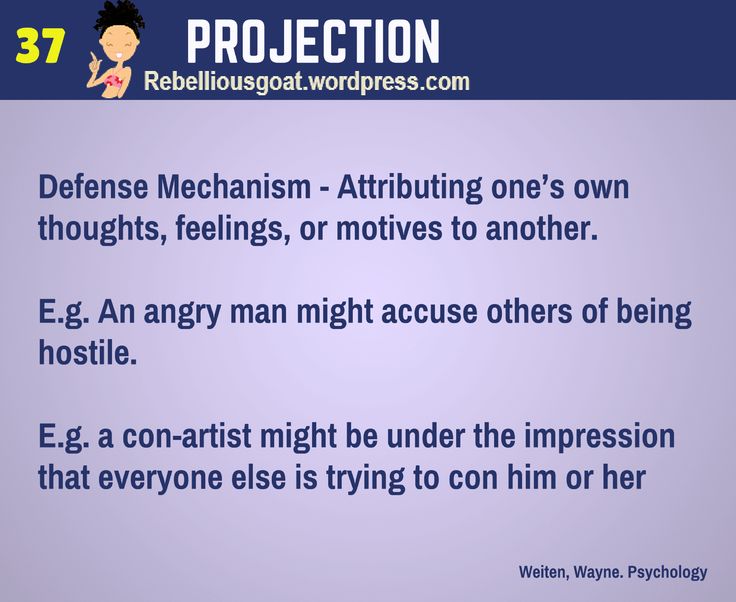

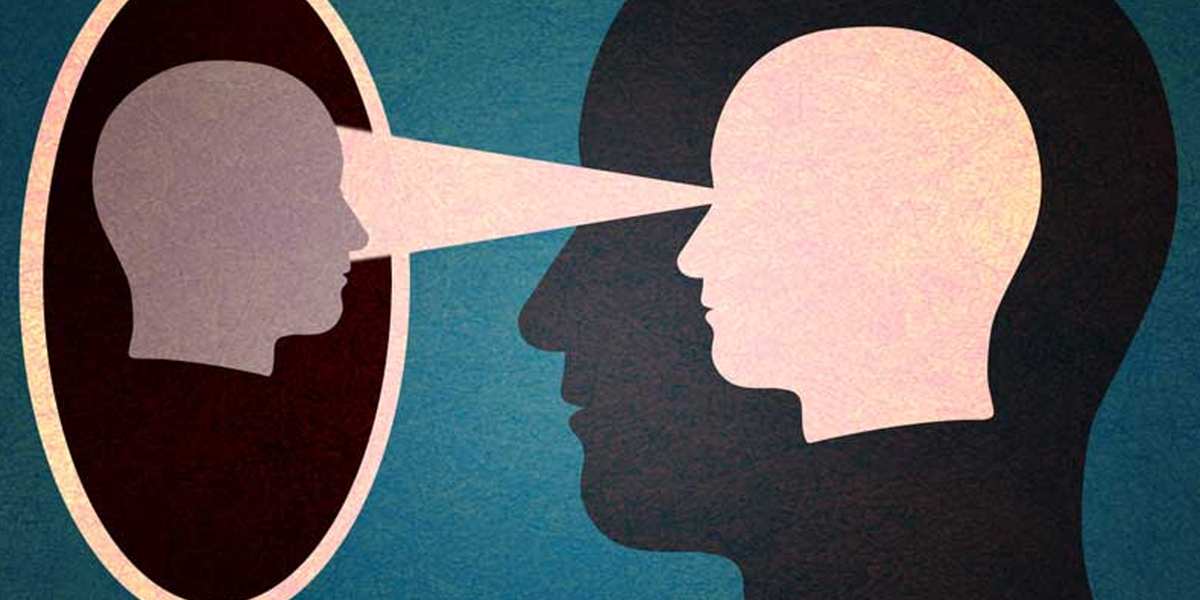

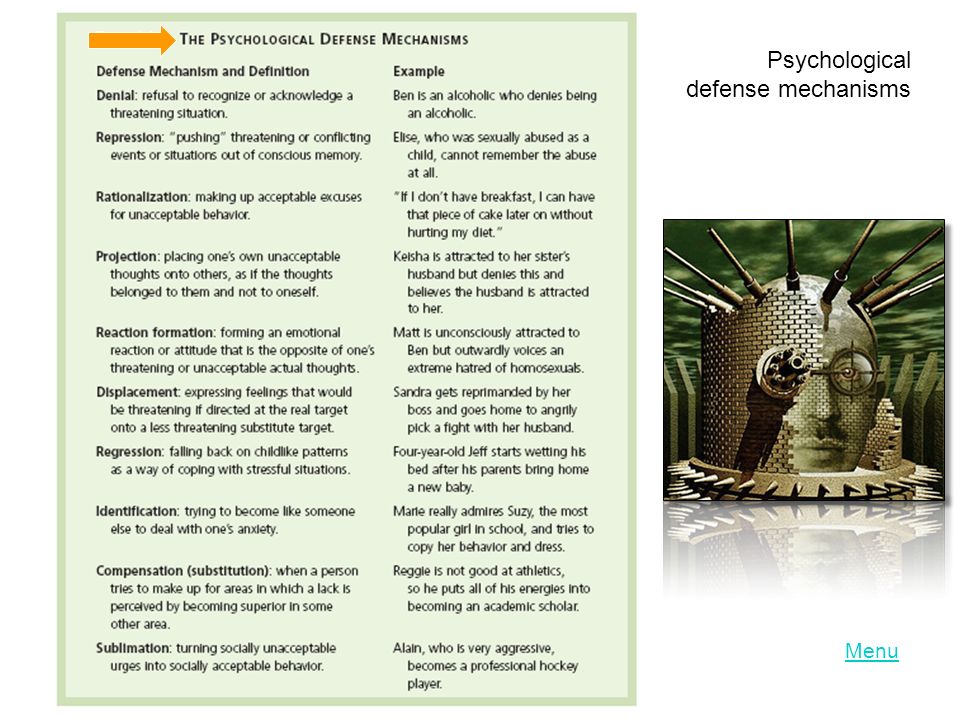

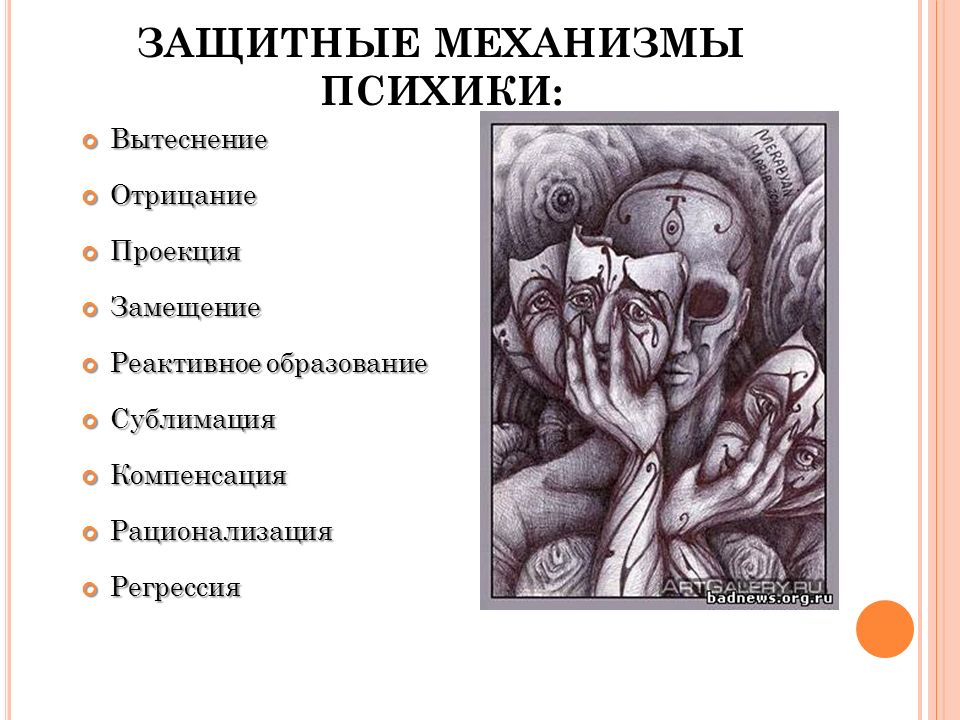

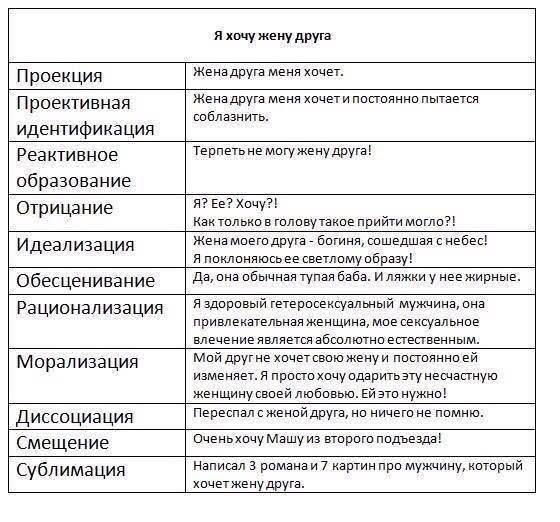

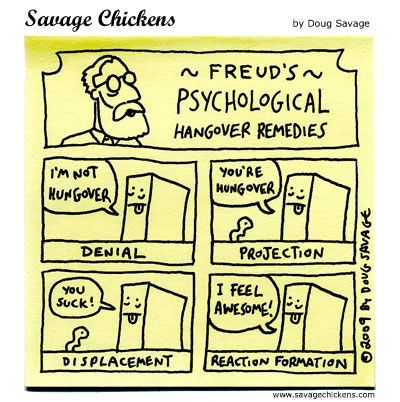

Projection is the process of displacing one’s feelings onto a different person, animal, or object. The term is most commonly used to describe defensive projection—attributing one’s own unacceptable urges to another. For example, if someone continuously bullies and ridicules a peer about his insecurities, the bully might be projecting his own struggle with self-esteem onto the other person.

The concept emerged from Sigmund Freud’s work on defense mechanisms and was further refined by his daughter, Anna Freud, and other prominent figures in psychology.

Contents

- What Is Projection?

- Projection in Everyday Life

- Projection in Therapy

What Is Projection?

Unconscious discomfort can lead people to attribute unacceptable feelings or impulses to someone else to avoid confronting them. Projection allows the difficult trait to be addressed without the individual fully recognizing it in themselves.

Who developed the concept of projection?

Freud first reported on projection in an 1895 letter, in which he described a patient who tried to avoid confronting her feelings of shame by imagining that her neighbors were gossiping about her instead. Psychologists Carl Jung and Marie-Louise von Franz later argued that projection is also used to protect against the fear of the unknown, sometimes to the projector’s detriment. Within their framework, people project archetypal ideas onto things they don’t understand as part of a natural response to the desire for a more predictable and clearly-patterned world.

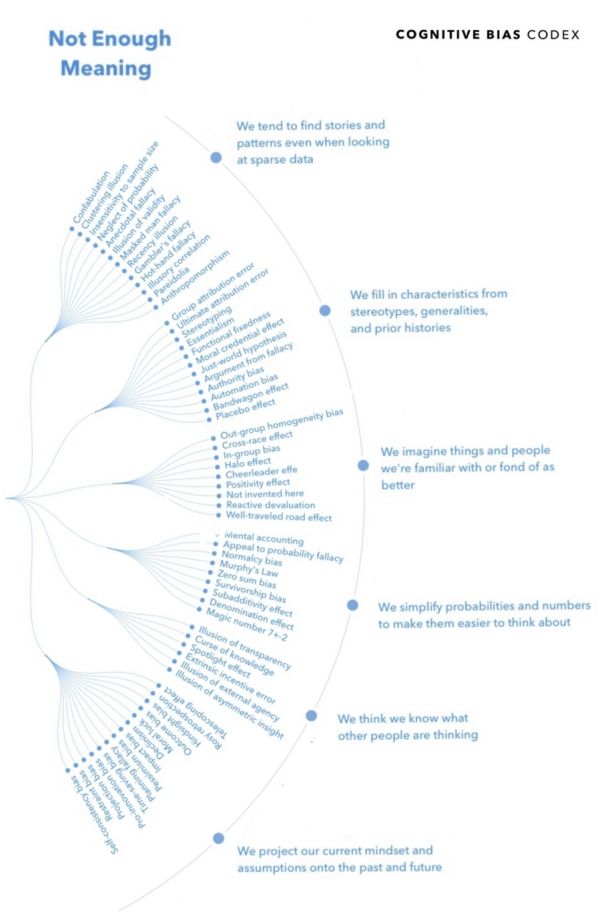

More recent research has challenged Freud’s hypothesis that people project to defend their egos. Projecting a threatening trait onto others may be a byproduct of the mechanism that defends the ego, rather than a part of the defense itself. Trying to suppress a thought pushes it to the mental foreground, psychologists have argued, and turns it into a chronically accessible filter through which one views the world.

Trying to suppress a thought pushes it to the mental foreground, psychologists have argued, and turns it into a chronically accessible filter through which one views the world.

What’s an example of projection?

An example of projection would be the following: A married man who is attracted to a female coworker, but rather than admit this to himself, he might accuse her of flirting with him. Another would be a woman wrestling with the urge to steal, who comes to believe that her neighbors are trying to break into her home.

Why do people project?

People tend to project because they have a trait or desire that is too difficult to acknowledge. Rather than confronting it, they cast it away and onto someone else. This functions to preserve their self-esteem, making difficult emotions more tolerable. It’s easier to attack or witness wrongdoing in another person than confront that possibility in one's own behavior. How a person acts toward the target of projection might reflect how they really feel about themselves.

How a person acts toward the target of projection might reflect how they really feel about themselves.

Is projection conscious or unconscious?

Projection is thought to be an unconscious process that protects the ego from unacceptable thoughts and impulses. Attributing those tendencies to others allows the person to place themselves above and beyond those urges, while still being able to observe them from afar. Although this occurs unconsciously, these patterns can be brought to conscious awareness, especially with the help of a therapist.

What is projective identification?

Projective identification occurs when the target of projection identifies with and expresses the feelings projected onto them. This represents a deeper stage of the distortions raised by projection, one that often occurs in relationships. For instance, a man could displace his own feelings of frustration towards a distant parent onto a romantic partner, who then withdraws emotionally after an argument.

Projection in Everyday Life

Projection can occur in a variety of contexts, from an isolated incident with a casual acquaintance to a regular pattern in a romantic relationship. But learning to recognize and respond to projection can help people understand and navigate social conflict.

How can you tell if you’re projecting?

When your fears or insecurities are provoked, it’s natural to occasionally begin projecting. If you think you might be projecting, the first step is to step away from the conflict. Time away will allow your defensiveness to fade so that you can think about the situation rationally. Then you can 1) Describe the conflict in objective terms 2) Describe the actions that you took and the assumptions you made and 3) Describe the actions the other person took and the assumptions they made in order. These questions can help you explore whether and why you may have been projecting.

How can you tell if someone is projecting on you?

If someone has an unusually strong reaction to something you say, or there doesn’t seem to be a reasonable explanation for their reaction, they might be projecting their insecurities onto you. Taking a step back, and determining that their response doesn’t align with your actions, may be a signal projection.

A harmful consequence of continual projection is when the trait becomes incorporated into one’s identity. For example, a father who never built a successful career might tell his son, “You won’t amount to anything” or, “Don’t even bother trying.” He is projecting his own insecurities onto his son, yet his son might internalize that message, believing that he will never be successful.

Although it’s difficult to do so, individuals who experience this can try to remember that the criques are about the other person, and to be confident in who they are outside of that relationship.

How does projection affect romantic relationships?

A common source of projection in romantic relationships emerges when unconscious feelings toward a parent are projected onto the person’s partner. If the partner then identifies with and expresses the feelings projected onto them, projective identification is at play.

Signs of projective identification in a relationship include having the same fight over and over again, feeling upset with your partner but not knowing why, and confusion about your reaction or your partner’s reaction to a situation. Couples can overcome projective identification by recognizing it, slowing down in conflicts, checking to make sure that they understand each other correctly, and considering couples therapy if needed.

How do narcissists use projection?

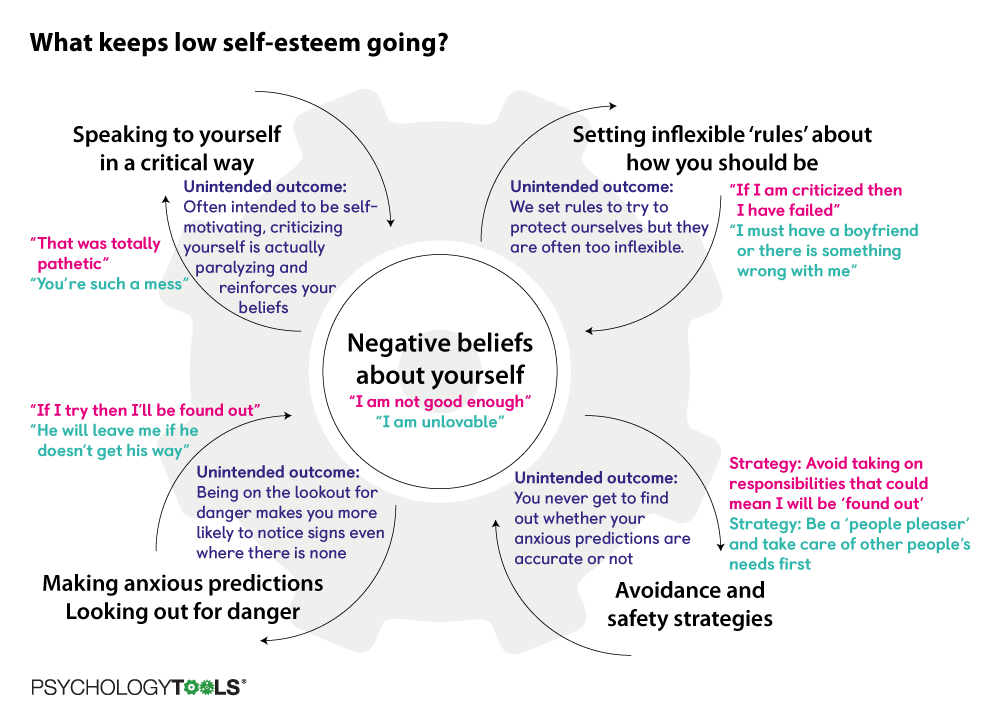

Narcissistic people often resort to projection to protect their self-image. Complaining about how someone else is so “showy” or “always needs attention” is one example of how a narcissist might project. They may also blame others for things that have gone wrong, rather than taking responsibility themselves. As the narcissist projects more shame and criticism onto another person, that individual’s self-doubt often grows, leading to a self-reinforcing cycle.

Complaining about how someone else is so “showy” or “always needs attention” is one example of how a narcissist might project. They may also blame others for things that have gone wrong, rather than taking responsibility themselves. As the narcissist projects more shame and criticism onto another person, that individual’s self-doubt often grows, leading to a self-reinforcing cycle.

How do you respond to projection?

Setting boundaries can help you respond to projection. Responding with clear statements such as “I disagree” or “I don’t see it that way” can deflect the projection and may prompt the person to reflect or take responsibility. It can also prevent you from internalizing unfair criticism or blame. But if the person continues to project, and seems unable to move forward, it may be necessary to remove yourself from the conversation.

Projection in Therapy

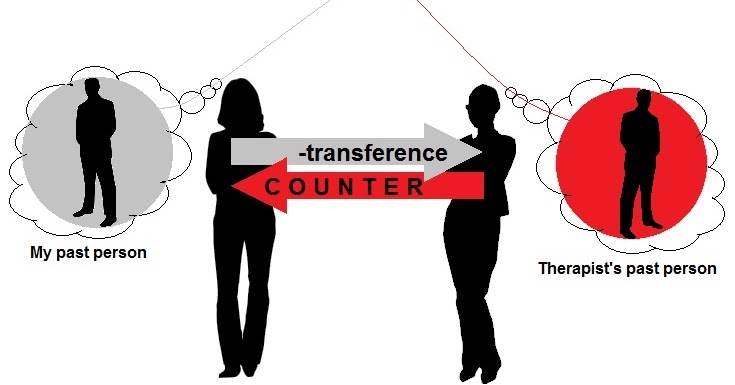

Projection can reveal hidden insecurities or beliefs that are valuable to explore in therapy. It also relates to the phenomenon of transference, in which a patient transfers feelings he or she has toward another important figure in their life onto a therapist. While projection can occur in different contexts, transference is primarily understood through a therapeutic lens. (For more, see Transference.)

It also relates to the phenomenon of transference, in which a patient transfers feelings he or she has toward another important figure in their life onto a therapist. While projection can occur in different contexts, transference is primarily understood through a therapeutic lens. (For more, see Transference.)

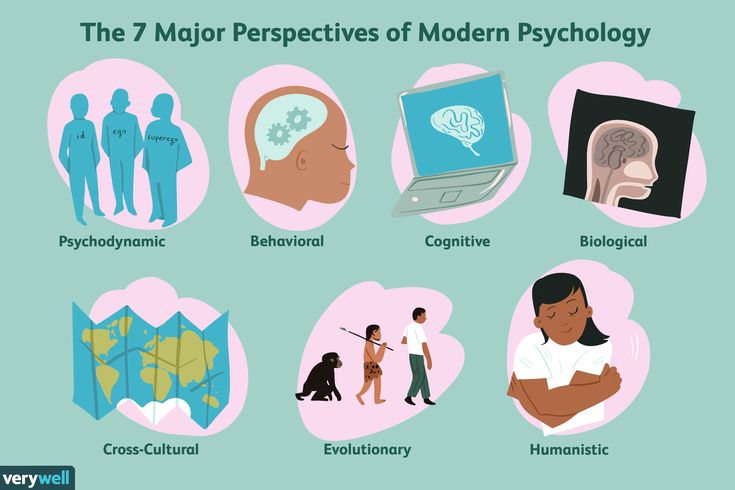

While psychodynamic and psychoanalytic therapists are more likely than others to invoke projection as a behavior of note, therapists trained in all modalities are familiar with the construct. Some may discuss a person misattributing or misunderstanding their own biases, without labeling such behavior "projection."

How does projection work in therapy?

Through their conversations, a therapist may observe that a patient seems to be projecting, either onto the therapist or toward other people in the patient’s life. For example, a therapist might realize that a patient continuously posits that their partner is having an affair, with no evidence. The therapist might explore whether the patient is secure in the relationship or is perhaps the one struggling to remain faithful. Projection can be an opportunity to identify difficult emotions that need to be processed.

The therapist might explore whether the patient is secure in the relationship or is perhaps the one struggling to remain faithful. Projection can be an opportunity to identify difficult emotions that need to be processed.

How do therapists respond to projection?

If a therapist suspects that a patient is projecting—either onto the therapist or onto other people in the patient’s life—they will likely explore the patient’s reaction. Understanding why the patient is reacting to the therapist with such a strong emotion, or misinterpreting a therapist’s statements, can help reveal underlying relationship challenges that should be discussed and resolved.

Essential Reads

Recent Posts

Projection | Definition, Theories, & Facts

Sigmund Freud

See all media

- Related Topics:

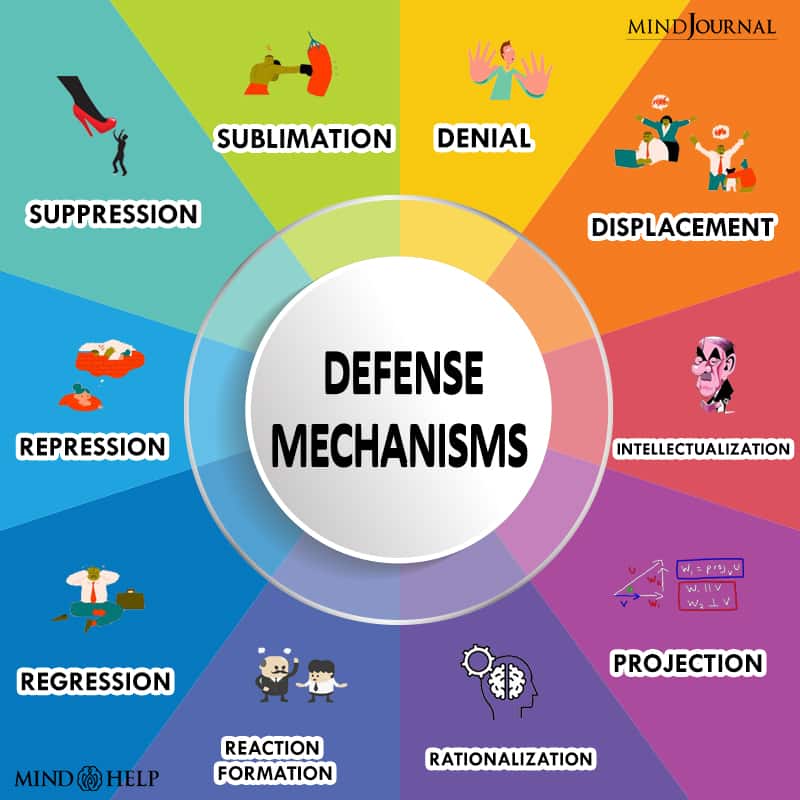

- defense mechanism

See all related content →

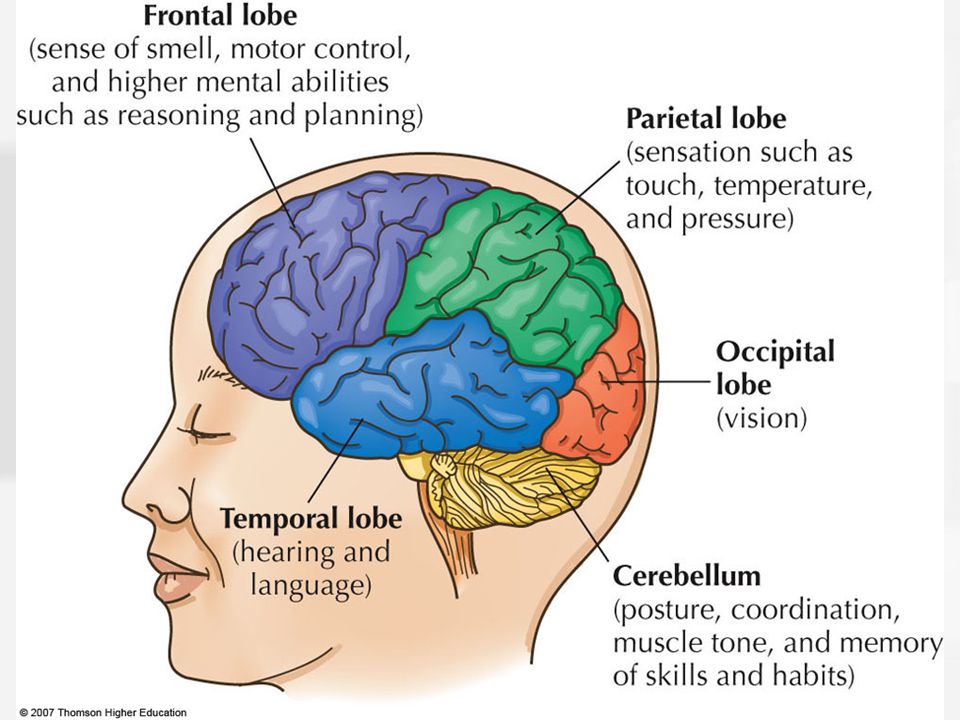

projection, the mental process by which people attribute to others what is in their own minds. For example, individuals who are in a self-critical state, consciously or unconsciously, may think that other people are critical of them. The concept was introduced to psychology by the Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), who borrowed the word projection from neurology, where it referred to the inherent capacity of neurons to transmit stimuli from one level of the nervous system to another (e.g., the retina “projects” to the occipital cortex, where raw sensory input is rendered into visual images). In contemporary psychological science the term continues to have the meaning of seeing the self in the other. This presumably universal tendency of the human social animal has both positive and negative effects. Depending on what qualities are projected and whether or not they are denied in the self, projection can be the basis of both warm empathy and cold hatred.

For example, individuals who are in a self-critical state, consciously or unconsciously, may think that other people are critical of them. The concept was introduced to psychology by the Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), who borrowed the word projection from neurology, where it referred to the inherent capacity of neurons to transmit stimuli from one level of the nervous system to another (e.g., the retina “projects” to the occipital cortex, where raw sensory input is rendered into visual images). In contemporary psychological science the term continues to have the meaning of seeing the self in the other. This presumably universal tendency of the human social animal has both positive and negative effects. Depending on what qualities are projected and whether or not they are denied in the self, projection can be the basis of both warm empathy and cold hatred.

In projection, what is internal is seen as external. People cannot get inside the minds of others; to understand someone else’s mental life, one must project one’s own experience. When someone projects what is consciously true of the self and when the projection “fits,” the person who is the object of projection may feel deeply understood. Thus, a sensitive father infers from his daughter’s facial expression that she is feeling sad; he knows that when he himself is sad, his face is similar. If he names the child’s assumed emotion, she may feel recognized and comforted. Intuition, leaps of nonverbal synchronicity (as when two persons in a relationship suddenly find themselves making similar gestures or thinking of the same image simultaneously), and peak experiences of mystical union (as when one feels perfectly attuned with an idealized other person, such as a romantic partner) involve a projection of the self into the other, often with powerful emotional rewards. Neuroscientific discoveries regarding mirror neurons and right-brain-to-right-brain communication processes (in which intuitive, emotional, nonverbal, and analogical thinking is shared between caregivers and children via intonation, facial affect, and body language) are establishing the neurological bases of such long-noted projective phenomena.

When someone projects what is consciously true of the self and when the projection “fits,” the person who is the object of projection may feel deeply understood. Thus, a sensitive father infers from his daughter’s facial expression that she is feeling sad; he knows that when he himself is sad, his face is similar. If he names the child’s assumed emotion, she may feel recognized and comforted. Intuition, leaps of nonverbal synchronicity (as when two persons in a relationship suddenly find themselves making similar gestures or thinking of the same image simultaneously), and peak experiences of mystical union (as when one feels perfectly attuned with an idealized other person, such as a romantic partner) involve a projection of the self into the other, often with powerful emotional rewards. Neuroscientific discoveries regarding mirror neurons and right-brain-to-right-brain communication processes (in which intuitive, emotional, nonverbal, and analogical thinking is shared between caregivers and children via intonation, facial affect, and body language) are establishing the neurological bases of such long-noted projective phenomena.

On the other hand, projection frequently functions as a psychological defense against painful internal states (“I am not the person feeling this; you are!”). When people project aspects of the self that are denied, unconscious, and hated and when they distort the object of projection in the process, projection can be felt as invalidating and destructive. At a social level, racism, sexism, xenophobia, homophobia, and other malignant “othering” mindsets have been attributed at least partly to projection. There is research evidence, for example, that men with notably homophobic attitudes have higher-than-average same-sex arousal, of which they are unaware. Projection of disowned states of mind is also a central dynamic in paranoia as traditionally conceptualized. Paranoid states such as fears of persecution, irrational hatred of an individual or group, consuming jealousy in the absence of evidence of betrayal, and the conviction that a desired person desires oneself (i.e., erotomania, the psychology behind stalking) result from the projection of unconscious negative states of mind (e. g., hostility, envy, hatred, contempt, vanity, sadism, lust, greed, weakness, etc.). In other words, paranoia involves both the disowning of a personal tendency and the conviction that this tendency is “coming at” oneself from external sources.

g., hostility, envy, hatred, contempt, vanity, sadism, lust, greed, weakness, etc.). In other words, paranoia involves both the disowning of a personal tendency and the conviction that this tendency is “coming at” oneself from external sources.

The Austrian-born British psychoanalyst Melanie Klein (1882–1960) wrote about a primal form of projection, “projective identification,” that she assumed to derive from the earliest mental life of children, before they feel psychologically separate from caregivers. Via this process, which has become an important concept in contemporary psychoanalytic thinking, a person tries to expel a state of mind by projecting it but remains identified with what is projected, is convinced of the accuracy of the attribution, and induces in the object of projection the feelings or impulses that have been projected. For example, a man in a rage projects his anger onto his wife, whom he now sees as the angry one. He insists it is her hostility that stimulated his rage, and almost immediately his wife becomes angry. Projective identification exerts emotional pressure that evokes in the other whatever has been projected. Another example: A woman in psychotherapy experiences her therapist’s ending a session on time as a sadistic attack. She loudly berates him for abusing her, accusing him of enjoying hurting her. In response to this denunciation and its misrepresentation of his motives, the normally compassionate therapist notices that he is having sadistic thoughts. The projection has become a self-fulfilling fantasy. Because projective identification is a particularly challenging defense to deal with in psychotherapy, it has spawned an extensive psychoanalytic literature.

Projective identification exerts emotional pressure that evokes in the other whatever has been projected. Another example: A woman in psychotherapy experiences her therapist’s ending a session on time as a sadistic attack. She loudly berates him for abusing her, accusing him of enjoying hurting her. In response to this denunciation and its misrepresentation of his motives, the normally compassionate therapist notices that he is having sadistic thoughts. The projection has become a self-fulfilling fantasy. Because projective identification is a particularly challenging defense to deal with in psychotherapy, it has spawned an extensive psychoanalytic literature.

Contrary to widespread professional opinion, however, projective identification is not simply a defense used by people with disorders of development and personality (see also mental disorders: Personality disorders). It operates in everyday life in numerous subtle ways, many of which are not pathological. For example, when what is projected and identified with involves loving, joyful affects, a group can experience a rush of good feeling. People in love can sometimes read one another’s minds in ways that cannot be accounted for logically. Because such emotional contagion occurs ubiquitously, many contemporary psychoanalysts have reframed as “intersubjective” what was once seen as the patient’s one-way projection onto the therapist. That is, both parties in a therapeutic relationship (or any relationship) inevitably share a mutually determined emotional atmosphere.

People in love can sometimes read one another’s minds in ways that cannot be accounted for logically. Because such emotional contagion occurs ubiquitously, many contemporary psychoanalysts have reframed as “intersubjective” what was once seen as the patient’s one-way projection onto the therapist. That is, both parties in a therapeutic relationship (or any relationship) inevitably share a mutually determined emotional atmosphere.

Klein’s writing led to a general professional acknowledgment that projection has more primitive and more mature forms. In its earliest expressions, self and other are not well differentiated. In mature projection, the other is understood to have a separate subjective life, with motives that may differ from one’s own. Before age three, children tend to assume that the emotional effect of an action was its intention. When caregivers set unwelcome limits, very young children react with normal, temporary hatred and accuse the parents of hating them. A slightly older child understands that when his mother’s limit-setting angers him, her act does not necessarily mean she is angry with him. Philosophers use the term “theory of mind” to denote this capacity to see others as having independent subjectivities. Contemporary psychoanalytic theorists and researchers refer to it as “mentalization.” Although a benign use of projection is the basis for understanding others’ psychologies, in mentalization there is little distortion of the other person’s mind because there is no automatic equation of it with the mind of the observer.

Philosophers use the term “theory of mind” to denote this capacity to see others as having independent subjectivities. Contemporary psychoanalytic theorists and researchers refer to it as “mentalization.” Although a benign use of projection is the basis for understanding others’ psychologies, in mentalization there is little distortion of the other person’s mind because there is no automatic equation of it with the mind of the observer.

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content. Subscribe Now

Empirical studies of defense mechanisms have supported clinical observations about projection, including the idea that it is one of many universal psychological defenses that evolve and mature in normal development. Understanding projection has been critically important to psychiatry, clinical psychology, counseling, and the mental health professions generally. It has also been cited as an explanatory principle in political science, sociology, anthropology, and other social sciences.

Nancy McWilliams

Fundamentals of projective psychology //Psychological newspaper

The psychological matrix of the actions performed, in the structure of which common personality traits are indirectly revealed, including those deeply hidden in the unconscious, each behavioral act of a person, each of his movements, each thought is a reflection of his personality. Working with the manifestations of personality through vigorous activity, one can not only obtain the most valuable clinical material, but also indirectly change the behavioral patterns of a person, which, using therapeutic language, doom the client to a feeling of "suffering". In fact, all psychotherapy works with the client's mental reality indirectly, through its phenomenological manifestations aimed at a specific object. One way or another, the personality is so firmly integrated into the activity that the reality of each person's interaction is unique and inseparable from behavior.

So, we come to the conclusion: all psychology is projective, because each object is perceived not in its pure form, but through mental mediation. After all, there is always a projection, even when psychology timidly hides in standardized and validated methods, meticulously collecting an anamnesis with familiar tools and giving a guarantee that the conclusions made, for example, by MMPI, are undeniable. Of course, each method must be reliable. The psychologist must know the current theories, methods of influence, tested in different conditions - both in the system of projective methods, and in psychological work, in principle. But all this does not exclude flexibility, and flexibility implies active subjectivity, combined with experience and wisdom.

In any case, in order to understand what Projective Psychology is, you must first decide: what is a projection?

For clarity, let's take the four most relevant definitions of projection (lat. projectio - throwing forward):

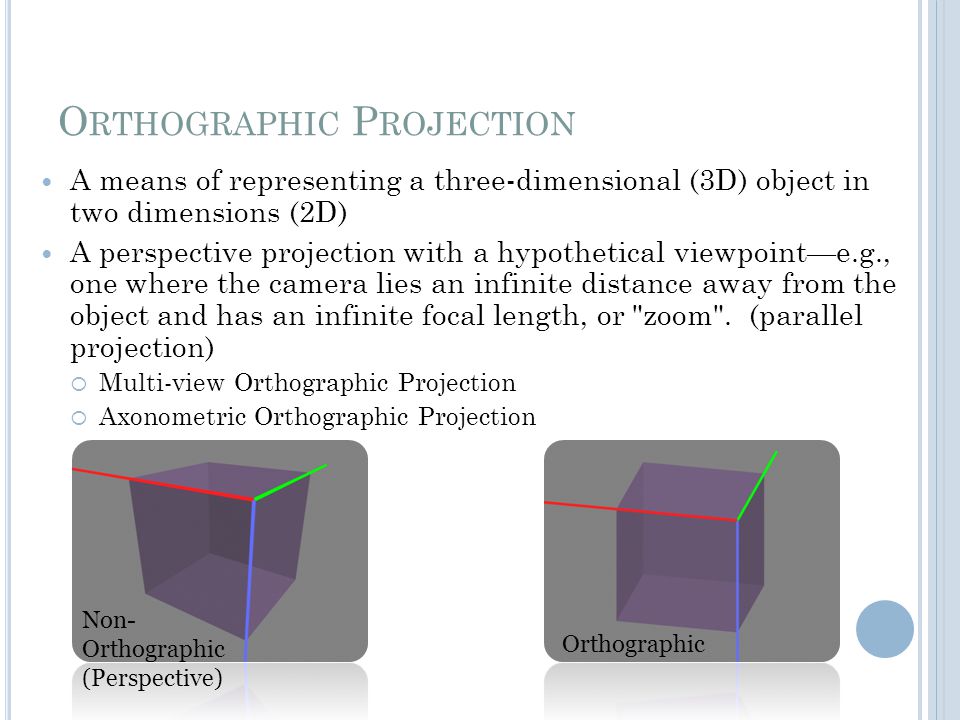

- Projection in geometry : representation of a three-dimensional figure on the so-called picture (projection) plane in a way that is a geometric idealization of optical mechanisms.

In psychological reflection, the phrase takes the form: this is a modeling of the image of a person (as a figure) on an alternative plane;

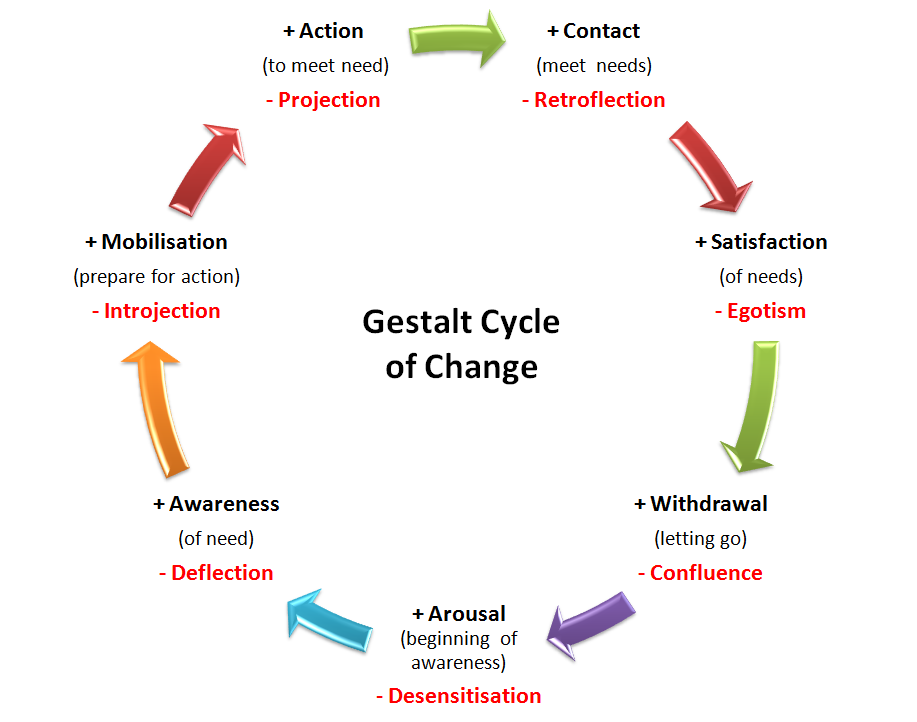

In psychological reflection, the phrase takes the form: this is a modeling of the image of a person (as a figure) on an alternative plane; - In Gestalt psychology projection is the process of involuntary attribution of the subjective processes of one person to others;

- In psychoanalysis, is a defense mechanism, which consists in unconsciously attributing properties, qualities, motives, thoughts and feelings that are unacceptable to oneself to another (this is where the difference lies - in Freud, these motives are already unacceptable, repressed). At the same time, we note that even Freud drew attention to the fact that projection can be not only a protective mechanism.

In Totem and Taboo, he wrote: “However, the projection is not created specifically for the purpose of protection, it also takes part in a conflict-free being. The projection of internal perceptions outwards is a primitive mechanism which, for example, also affects our perception of sensory experience, and therefore, as a rule, takes a very active part in the formation of our external world. Under still insufficiently defined circumstances, even internal perceptions of thought and emotional processes are projected outward, like perceptions of sensations ... "and further:" What we, like primitive people, project into external reality can hardly be anything else than recognition a state in which this phenomenon takes place for feelings and consciousness, next to which there is another state where it is hidden, but can reappear, that is, the coexistence of perception and memory, or, generalizing, the existence of an unconscious mental process next to the conscious. This thought of Freud, which has not been further developed or expressed systematically elsewhere, contains everything necessary for a coherent theory of projection and general perception.

Under still insufficiently defined circumstances, even internal perceptions of thought and emotional processes are projected outward, like perceptions of sensations ... "and further:" What we, like primitive people, project into external reality can hardly be anything else than recognition a state in which this phenomenon takes place for feelings and consciousness, next to which there is another state where it is hidden, but can reappear, that is, the coexistence of perception and memory, or, generalizing, the existence of an unconscious mental process next to the conscious. This thought of Freud, which has not been further developed or expressed systematically elsewhere, contains everything necessary for a coherent theory of projection and general perception.

In psychodiagnostics (L. Frank) - the process and result of the interaction of the subject with objectively neutral unstructured material, during which identification and projection proper are carried out, that is, endowment with one's own thoughts, feelings, experiences.

In the school of projective psychology, we combine the first and last definitions, as well as the little-known definition of Z. Freud, approaching the above-described vision of the projection by D. Rapoport, that is:

Projection is any manifestation of the psychic reality of an individual in his activity, and projective psychology, respectively, is a direction for working with a client in the context of interaction with the images he creates, which have the largest number of indirect mediated connections with his personality.

The term itself is most widely used in the context of projective psychological tests. However, in modern articles, books, as well as in practical psychology and psychotherapy, one can see that this term is used somewhat more widely.

In our practice, we turn to such areas as psychodrama, metaphorical associative cards, fairy tale therapy, sand therapy.

What can all these areas have in common? All of them, one way or another, are focused on working with structures or motivators hidden from consciousness. The degree of orientation to the unconscious part of the personality is different, different methods, language, tools, but one way or another there is an initial installation that there are many hidden, uncontrollable layers in a person, and you can find ways and language to address these structures and even make changes at this level .

The degree of orientation to the unconscious part of the personality is different, different methods, language, tools, but one way or another there is an initial installation that there are many hidden, uncontrollable layers in a person, and you can find ways and language to address these structures and even make changes at this level .

If we turn to the history of psychology, the first who drew the attention of the world community to the existence of the unconscious was Sigmund Freud. Thus, each of the schools listed above originates from the Freudian theory of the unconscious.

Let's briefly talk about the concept of the unconscious formulated by Freud. Speaking about the topographic model, it must be said that Freud singled out several levels of the mental, depending on how accessible they are for human awareness.

Freud's concept of personality is most conveniently viewed as a stepped topographical model. The lower level is the unconscious, material inaccessible to awareness, and at the same time the foundation of the entire psyche, the true aspirations and motives of a person. The middle level is the preconscious, material that can be brought into consciousness. And the highest level is consciousness, a structure that provides a person with contact with the outside world.

The middle level is the preconscious, material that can be brought into consciousness. And the highest level is consciousness, a structure that provides a person with contact with the outside world.

Later, Freud expanded his understanding of the structure of the psyche, clarifying the functional tasks of individual components. Here we are talking about the well-known construction Id - Ego - Superego, where Id is the basic needs of the individual (libidinal and aggressive), Superego is a reflection of external norms, prohibitions and dogmas, and Ego is a structure that provides a person’s ability to redirect his original urges in such a way that be in tune with the outside world.

If we combine the two structures proposed by Freud, we get the following scheme:

Figure 1. Freud's Unconscious

Thus, only a part of the psychic, belonging to the Ego structure, and a part of the Superego structure fall into the sphere of the conscious. Most of the processes of these structures belong to the area of “preconscious”. The id completely falls into the inaccessible unconscious, informing about itself through a change in the processes in the ego.

Most of the processes of these structures belong to the area of “preconscious”. The id completely falls into the inaccessible unconscious, informing about itself through a change in the processes in the ego.

Z. Freud considered his main scientific goal to study the possibilities of bringing unconscious tendencies into consciousness, since, in his opinion, this is the only therapeutic possibility for harmonizing the personality.

At the moment, part of the therapeutic schools have abandoned the task of conducting therapy precisely through the bringing into consciousness of all possible motives. The work is carried out at the level of the preconscious and even the unconscious.

Student and opponent of Z. Freud, C. G. Jung (1916) supplemented the understanding of the unconscious with the term “collective unconscious” and the doctrine of archetypes. The collective unconscious is understood as a repository of all the main knowledge of mankind, which is inherited by a person, regardless of his individual characteristics. The key figures of the collective unconscious are archetypes; structures that embody the leading universal, common ideas, needs, roles.

The key figures of the collective unconscious are archetypes; structures that embody the leading universal, common ideas, needs, roles.

Figure 2. Unconscious according to K.G. Jung

The process of therapy according to Jung is to release the signals of the repressed unconscious to some extent, and to equalize the balance between consciousness and the unconscious. Accordingly, according to Jung, the release of the unconscious is therapeutic in itself. This one is closer to the ideas that art therapy and some other projective methods of psychology rely on.

An extended model of the unconscious was proposed by Roberto Assagioli in 1958. Assagioli tried to bring together seemingly heterogeneous even contradictory manifestations of the unconscious.

The following areas are distinguished in the proposed scheme.

1. Lower unconscious. It includes: - elementary mental activity that governs the life of the body; - basic instincts and primitive aspirations; - a large number of various emotionally charged complexes; - dreams and fantasies of the lowest quality; - various pathological manifestations, such as phobias, obsessions, compulsive desires, paranoid hallucinations.

2. Middle unconscious. It is formed by elements of the psyche, reminiscent of the elements of the awakening consciousness and easily accessible to him. A variety of experiences are collected in this inner region, and ordinary mental and imaginary actions are nurtured and mature here before they finally take shape and appear in the light of consciousness.

3. Higher unconscious or superconscious. This is the area from which we receive insights and inspirations of a higher nature - artistic, philosophical, scientific. From here the “requirements” of morality come to us, here the need to perform humane and heroic deeds is born. It is the source of such higher feelings as altruistic love, the source of spirituality, states of enlightenment, illumination and spiritual ecstasy. Here, in a hidden form, higher mental functions and spiritual energy are hidden.

4. Area of consciousness. This term refers to that part of our personality that we are directly aware of. This includes an unceasing stream of sensations, images, thoughts, feelings, desires and impulses that are available to our observation, analysis and evaluation.

5. Conscious "I". "I" is the stable center of our personality. "I", a point of pure self-awareness.

6. Higher "I". "Higher Self", located somewhere outside or above our "I". It is a kind of divine prototype of our personality and helps to keep the stability of the conscious “I”, as if there was a model with which the personality is correlated.

7. Collective unconscious. The process of “psychological exchange” is constantly taking place both between individuals and in a wider psychological environment, which generally corresponds to what C. Jung called the “collective unconscious”.

This theory is not the most popular model in the discussion of specialists about the unconscious, but it resolves many contradictions in the understanding of the unconscious and the unconscious in different schools. In addition, it allows us to navigate the material that we receive in the process of working with projective technologies.

Figure 3. The Unconscious according to R. Assogioli

The Unconscious according to R. Assogioli

Based on R. Assogioli's personality model, it is possible to single out the areas of action of various psychological methods.

Figure 4. Mental levels and methods of correction

The next necessary “stop” on the way to discussing the conceptual field of projective psychology will be a conversation on the topic of projective methods of psychodiagnostics.

One of the first projective tests that has not lost its applied value is still the “Rorschach Spots” test.

The test was developed by the Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach (1921). Rorschach found that those subjects who see the correct symmetrical figure in a shapeless ink blot usually understand the real situation well, are capable of self-criticism and self-control. So the specificity of perception indicates the personality traits of a given individual.

Studying self-control, understood mainly as mastery over emotions, Rorschach used ink blots of different colors (red, pastel shades) and different intensities of gray and black to introduce factors that have an emotional impact. The interplay of intellectual control and emerging emotion determines what the subject sees in the inkblot. Rorschach found that individuals whose different emotional states were known from clinical observation did indeed respond differently to colors and hues. It turned out that ink blots can reveal deeply hidden desires or fears that underlie long-term unresolved personality conflicts. Significant information about the needs of the individual, about what makes a person happy or sad, what excites him, and what he is forced to repress and translate into subconscious fantasies, can be extracted from the content or "plot" of the associations caused by inkblots.

The interplay of intellectual control and emerging emotion determines what the subject sees in the inkblot. Rorschach found that individuals whose different emotional states were known from clinical observation did indeed respond differently to colors and hues. It turned out that ink blots can reveal deeply hidden desires or fears that underlie long-term unresolved personality conflicts. Significant information about the needs of the individual, about what makes a person happy or sad, what excites him, and what he is forced to repress and translate into subconscious fantasies, can be extracted from the content or "plot" of the associations caused by inkblots.

The test has been further developed both in theory and practice. The validity, adequacy and effectiveness of the Rorschach test has not yet been definitively established. Nevertheless, it helps the psychologist and psychiatrist to obtain important data for the diagnosis of personality and its disorders, which can be clinically tested.

Projective methods and approach, in general, is characterized by the creation of an experimental situation that allows for a plurality of possible interpretations when perceived by the subjects. The most essential feature of projective methods is the use of indefinite stimuli in them, which the subject must himself supplement, interpret, develop, etc. Thus, the subjects are asked to interpret the content of plot pictures, complete unfinished sentences, give an interpretation of indefinite outlines, etc.

Let's take a brief look at the general classification of projective methods.

Methods of Projective Psychology

Methods can be structured using the Frank-Noss classification. OK. Frank introduced the term itself - the projective method and created their first classification, I.N. Noss - Doctor of Psychology, Associate Professor, specializing in the study of problems of professional and acmeological diagnostics. He added, and in our opinion significantly improved the original classification.

Many of the techniques mentioned below are used in the School of Projective Psychology as diagnostic and therapeutic tools. You can read more about the experience of applying these methods in the School group: http://vk.com/proektpsy.

So, projective methods can be structured as follows.

- Constitutive. The client works with structureless materials, creating a certain form from it, giving it a certain meaning. Respectively (Wartegg test, Rorschach test, finger painting test)

- Constructive. Creation of an image according to the task. Usually, constructive methods are understood as free drawing tests. (Tree test, House-Tree-Man test, Non-Existent Animal test)

- Interpretive. Interpretive methods are based on assigning their own meaning to stimulus situations. (TAT, Incomplete Sentence Test, Word Association Test, Hand Test)

- Semantic. Identification of emotional reactions to different stimuli as a reflection of the mental state (Kelly's Repertory Grids, Nonverbal Semantic Differential)

- Refractive.

The battery of tests got its name from G. Allport. It contains descriptive methods for diagnosing a person according to the signs present in his daily life (graphology, the study of behavior, clothing, interaction with people).

The battery of tests got its name from G. Allport. It contains descriptive methods for diagnosing a person according to the signs present in his daily life (graphology, the study of behavior, clothing, interaction with people).

There are very few researchers of handwriting in Russia now. All modern Russian books provide only some methods of analysis in this direction. At the same time, in Germany, for example, or in the USA, the price of handwriting analysis is quite high (up to 1,500 euros!) In Israel, there is a whole institute for graphic analysis, now this area is actively developing. In St. Petersburg, our School of Projective Psychology conducts classes in graphology and consultations with a graphologist with a qualitative analysis of handwriting (the specialist studied graphology in Germany and already has extensive experience in this area).

Cathartic methods are the most widely represented in the School of Projective Psychology.

Cathartic methods are a set of projective methods that are used not as tests, but as a way of working with the ego image through an act of activity. As we have already indicated above, in our School we pay the most attention to such areas as sand therapy, psychodrama, fairy tale therapy, and metaphorical cards. Let's describe these methods in more detail.

As we have already indicated above, in our School we pay the most attention to such areas as sand therapy, psychodrama, fairy tale therapy, and metaphorical cards. Let's describe these methods in more detail.

1. The Rorschach test is conceptually the progenitor of such a therapeutic method as working with metaphorical associative maps (MAC). MACs go back to abstract inkblots; they then went through a series of transformations into drawings and photographs, which were first used as a diagnostic tool in psychology, later as a projective therapy tool, and as stimuli for creating metaphorical stories. At the moment, the MAC is already dozens of decks of cards, mostly pictures with realistic or abstract content, some decks use word cards. In symbolic form, they depict a variety of situations, objects and environments, both traumatic and resource content.

Cards are a stimulus material that helps the client, together with the therapist, to access different layers of the client's experiences with minimal resistance. The client chooses and works with those cards that evoke the greatest response in him. With their help, you can “pull out” unconscious aspects of the self-concept, actualize both recent and deeper experiences and traumas, enable the client to come up with a positive outcome for a problem situation, work with both therapeutic and corrective, and even coaching requests.

The client chooses and works with those cards that evoke the greatest response in him. With their help, you can “pull out” unconscious aspects of the self-concept, actualize both recent and deeper experiences and traumas, enable the client to come up with a positive outcome for a problem situation, work with both therapeutic and corrective, and even coaching requests.

The next therapeutic method studied in our School is fairy tale therapy. The fairy tale therapist creates conditions in which the client, working with a fairy tale (reading, inventing, acting out, continuing), finds solutions to his life's difficulties and problems. Simultaneously with this leading task, with the help of a fairy tale, a system of rules and norms can be identified or formed, since by listening and perceiving fairy tales, a person builds them into his life scenario and values.

Fairy tale therapy is a wonderful tool for development. In the process of listening, inventing and discussing a fairy tale, a child develops the fantasy and creativity necessary for effective existence. He learns the basic mechanisms of search and decision making. The same mechanisms work in adults, which is why many trainers and coaches use fairy tales in their work to help clients find a more effective way to solve life's problems.

He learns the basic mechanisms of search and decision making. The same mechanisms work in adults, which is why many trainers and coaches use fairy tales in their work to help clients find a more effective way to solve life's problems.

The fairy tale therapist touches several levels at once in his work. On the one hand, in a fairy tale the client shows his archetypes and social attitudes, they are clearly displayed and can have a key influence on the plot, on the other hand, the fairy tale touches on early childhood experiences and in the plot it is possible to trace the genesis of the client’s personality, thirdly, the client fills the fairy tale with his up-to-date content. And then the fairy tale therapist decides which layer to pay attention to during the session, depending on what will be most useful to the client now.

Let's talk about sand therapy. Classic sand therapy uses a wooden tray, sand, water and a collection of miniature figurines. The collection includes all possible objects that are only found in the surrounding world. Real and mythological figurines are used, created by man and nature, attractive and terrible. The use of natural materials allows you to feel a connection with nature, and man-made miniatures allow you to accept what already exists.

Real and mythological figurines are used, created by man and nature, attractive and terrible. The use of natural materials allows you to feel a connection with nature, and man-made miniatures allow you to accept what already exists.

This process differs from other forms of art therapy by the possibility of inventing new forms, the short duration of the existence of created images. The possibility of destruction of the sand composition, its reconstruction, as well as the repeated creation of new plots, gives the work a certain kind of ritual. The creation of successive sand compositions reflects the cyclical nature of mental life, the dynamics of mental changes. Due to the fact that the client uses ready-made figurines, it is easier for him to overcome embarrassment and doubt about his creative abilities at the beginning. Miniature figurines, natural materials, the possibility of creating three-dimensional compositions give the image additional properties, reflect different levels of mental content, and help establish access to preverbal levels of the psyche. When working in psychotherapy on disorders originating from the time of early childhood, when the child could not yet speak, the visual image is very important.

When working in psychotherapy on disorders originating from the time of early childhood, when the child could not yet speak, the visual image is very important.

The modern development of sand therapy also suggests the abandonment of the sandbox and figurines in favor of the innovative “living sand”. The therapy emphasizes bodily interaction with the sand and immerses the client in the earliest childhood experiences that belong to the deepest levels of the unconscious.

Psychodrama stands apart from other areas we study. This method does not use any special stimulus material, and conceptually has a broader ideological basis.

Psychodrama is a method of psychotherapy and psychological counseling created by Jacob Moreno. Classical psychodrama is a therapeutic group process that uses the instrument of dramatic improvisation to explore the inner world of a person. This is done to develop the creative potential of a person and expand the possibilities of adequate behavior and interaction with people.

Psychodrama is the world's first method of group psychotherapy (actually, the term "group psychotherapy" itself was introduced into Moreno's psychology). Moreno proceeded from the fact that, since any person is a social being, a group can solve his problems more effectively than one person.

Moreno developed his ideas in a polemic with Freud, he did not like the passive role of the patient and the fact that the psychotherapeutic process took place "one on one". He brought two new directions to psychotherapy in his school. He allowed the client to be active and active in the process of therapy, and offered him the group space as close as possible to real life and therefore an effective context for therapy.

The meaning of the psychodrama session is as follows. “Protagonist” - a client of a group action, with the help of the group members, dramatically plays the situation that excites him. First, the protagonist chooses from the group members the one who will play himself in those cases when he himself will be in a different role. Then, participants are selected to play the roles of characters that are important for his life situation (these can be both real people and his fantasies, thoughts and feelings). The forms of enactment range from the literal reenactment of real events to the staging of symbolic scenes that never took place in reality. The action step ends when the contract concluded with the protagonist is fulfilled, that is, a solution to the problem situation is found or the protagonist feels that he has received enough information about the situation.

Then, participants are selected to play the roles of characters that are important for his life situation (these can be both real people and his fantasies, thoughts and feelings). The forms of enactment range from the literal reenactment of real events to the staging of symbolic scenes that never took place in reality. The action step ends when the contract concluded with the protagonist is fulfilled, that is, a solution to the problem situation is found or the protagonist feels that he has received enough information about the situation.

What does this technique have in common with other areas? Mainly - this is an appeal to the creative potential of the client and the involvement of unconscious internal dominants. The client, becoming a protagonist, surrenders to the will of his unconscious, as well as the total unconscious of the group, which can also be a reduced model of the collective unconscious. No matter how controlled and understandable for him his actions are, but the abundance of uncontrollable factors when used in the production of other people makes this work projective, and the number of projections is significantly higher than when working with stimulus material.

This article can be summed up in the words of Carl Gustav Jung: “Fantasy is the mother of all possibilities, where, like all opposites, the inner and outer worlds come together.” All of the methods listed above involve fantasy as the leading structure of the personality. With the help of fantasy and creativity, an earlier, possibly traumatic experience is brought into the field of therapy. With the help of fantasy and creativity, a person replenishes himself with new emotions, creates new associative connections, forms new resources and constructs perspectives. Whatever technological solution we choose, the main “accomplice” of both the therapist and the client will be creativity.

Working with creative tasks and manipulating with polysemantic flexible stimulus material returns to childhood and promotes the activation of the “child archetype”, raising repressed childhood experience from the bottom. And in this aspect, the therapist gets the widest freedom to build a therapeutic path, using all the wealth of both theoretical and practical psychology.

Ekaterina Stepanova – psychologist, teacher of psychology, coach, specialist in psychodrama, sand therapy, fairy tale therapy, work with metaphorical associative maps, head of the School of Projective Psychology. Master class of the author of the article - in the program of the All-Russian Festival of Sand Psychotherapy

Chigray Ivan – social psychologist, graphologist, specialist in projective methods of diagnostics.

Physiological basis of perception

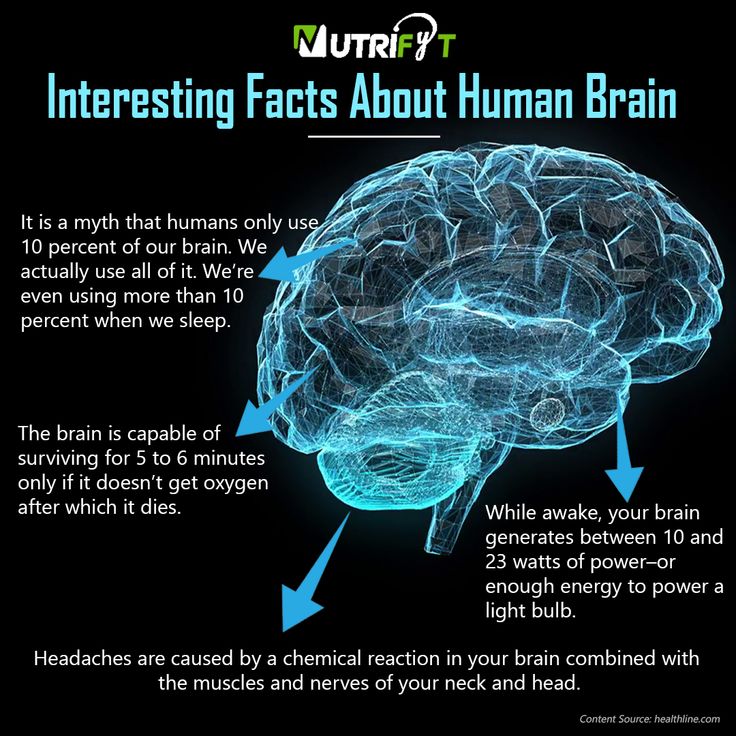

The activity of perception as a mental process is provided by the processes taking place in the sense organs, nerve fibers and the central nervous system.

Under the action of stimuli in the endings of the nerves present in the sense organs, nervous excitation arises, which is transmitted along the conducting paths to the nerve centers and, ultimately, to the cerebral cortex. Here, nervous excitation enters the projection (sensory) zones of the cortex, which thus represent the central projection of the nerve endings present in the sense organs. Different projection zones are associated with different sense organs, and depending on which organ the projection zone is associated with, certain sensory information is formed.

Different projection zones are associated with different sense organs, and depending on which organ the projection zone is associated with, certain sensory information is formed.

The mechanism described up to this point is the mechanism for the generation of sensations. These sensations - almost literally - are a reflection of the surrounding reality. Just as the surrounding objects are reflected in a mirror or in a photograph, the same objects are reflected in the projection zones, only in the form of nervous excitations, from point to point.

The process of perception only begins with sensations. Own physiological mechanisms of perception are included in the process of forming a holistic image of an object at subsequent stages, when the excitation from the projection zones is transmitted to the integrative zones of the cerebral cortex, where the formation of images of real world phenomena is completed. Therefore, the integrative zones of the cerebral cortex, which complete the process of perception, are often called perceptual zones. Their function differs significantly from the functions of the projection zones.

Their function differs significantly from the functions of the projection zones.

The difference in the work of the projection and integrative zones is revealed when the activity of one or another zone is disturbed in a person. If the work of the visual projection zone is disturbed, the so-called central blindness occurs, that is, if the periphery - the sense organs - is in full working order, the person is completely deprived of visual sensations, he sees nothing at all. If the integrative zone is affected (while the projection zone is preserved), the person sees separate light spots, some contours, but does not understand what he sees. He ceases to comprehend what affects him, he does not even recognize well-known objects and people.

A similar picture is observed in other modalities. In violation of the auditory integrative zones, people cease to understand human speech. Such diseases are called agnostic disorders (disorders leading to the impossibility of cognition), or agnosia,

Perception is closely related to motor activity, emotional experiences, thought processes, and this further complicates the understanding of the physiological foundations of perception. Having begun in the sense organs, nervous excitations caused by external stimuli pass to the nerve centers, where they cover various zones of the cortex and interact with other nervous excitations. This whole complex network of excitations grows. Interacting excitations widely cover different areas of the cortex.

Having begun in the sense organs, nervous excitations caused by external stimuli pass to the nerve centers, where they cover various zones of the cortex and interact with other nervous excitations. This whole complex network of excitations grows. Interacting excitations widely cover different areas of the cortex.

Temporal neural connections are of great importance in the process of perception. Just as a pen and a piece of paper help to count in a column, so temporary neural connections provide the perception with the ability to make hypotheses, which are necessary for a deep analysis of the perceived situation. Temporary neural connections that provide the process of perception can be of two types:

- connections formed within the same analyzer,

- interanalyzer connections.

The first type of connections takes place when the organism is exposed to a complex stimulus of one modality. For example, such an irritant is a melody, which is a kind of combination of individual sounds that affect the auditory analyzer. This whole complex acts as one complex stimulus. In this case, neural connections are formed not only in response to the stimuli themselves, but also to their relationship - temporal, spatial, etc. (the so-called reflex to the relationship). As a result, the process of integration, or complex synthesis, takes place in the cerebral cortex.

This whole complex acts as one complex stimulus. In this case, neural connections are formed not only in response to the stimuli themselves, but also to their relationship - temporal, spatial, etc. (the so-called reflex to the relationship). As a result, the process of integration, or complex synthesis, takes place in the cerebral cortex.

Interanalyzer nerve connections are formed under the influence of a complex stimulus. These are connections within different analyzers, the emergence of which I.M. Sechenov explained by the existence of associations (visual, kinesthetic, tactile, etc.). These associations in a person are necessarily accompanied by an auditory image of the word, due to which perception acquires a holistic character.

Thanks to the connections formed between analyzers, we reflect in perception such properties of objects or phenomena for the perception of which there are no specially adapted analyzers (for example, the size of an object, specific gravity).