Problems listening to people

ADHD Listening Problems: Focus and Attention

People often mistake listening for a passive activity, but it’s actually an active process. You have to make a conscious effort to hear what someone’s saying, and by doing so, you make that person feel understood.

Good listening shows others that they’re important to you, so naturally, when your listening skills improve, so do your relationships.

While effective listening is a highly regarded social skill, it doesn’t come easily to people with ADHD, who have a hard time concentrating. Fortunately, it’s a skill you can learn. To become a good listener, you need to identify how you listen.

The following listening (or not-listening) styles are common in many adults with ADHD. If you recognize yourself in any of these scenarios, practice the accompanying strategies. With some effort, you can turn your listening habits around.

Non-Stop Talk

If you talk at the speed of light, feel compelled to voice every thought running through your overactive mind, and keep others from getting a word in, there’s no time for listening. This trait, found in fidgety adults with hyperactive ADHD, can be a serious detriment to relationships.

[Click to Read: “You’re Not Listening!” How ADHD Impulsivity and Insecurity Broke (Then Saved) My Relationships]

CHALLENGE: To take a breather.

STRATEGIES:

- Slow down. A breath between sentences will help you control the rush of words bursting out of your mouth and give others a chance to take in what you have to say.

- Wait your turn. ADHD “talkers” have difficulty controlling the impulse to jump in and interrupt. Aside from being annoying to others, the behavior makes it hard to focus on what someone is saying. When someone’s speaking, concentrate on waiting until he ends his sentence before you jump in. If you have a question, ask permission before asking it. “Excuse me, may I ask a question?”

- Talk about what you hear. When someone is talking to you, focus on finding a key point to comment on, rather than running off in all directions.

This lets others know you’re listening, helps you follow along, and it opens the door to social acceptance.

This lets others know you’re listening, helps you follow along, and it opens the door to social acceptance.

- See what you hear. To think about what someone is saying to you, visualize the story in your mind. Pretend that you’ll be quizzed, and that you’ll have to summarize the conversation. Could you do it?

[Get This Free Download: Become a Small-Talk Superstar]

No Words for It

When someone else is talking, you don’t make a peep. While talking too much makes it difficult to listen effectively, not saying enough – common in folks with inattentive ADHD – can be equally problematic. Your mind may wander from what’s being said. By failing to participate in conversation, you are implying that you’re not listening, you don’t understand, or worse – you just don’t care.

CHALLENGE: To follow along.

STRATEGIES:

- Make a move. Use nonverbal cues, like nods and smiles, to signal that you’re tuned in.

- Utter sounds. Say brief words or sounds, like “uh-huh,” or “go on,” to encourage others to continue.

- Look for opportunities to comment politely. (Interrupting isn’t polite.) If you need more time to process your thoughts, ask the person who’s speaking to pause a moment while you decide what to say.

Let’s Talk About Me

Conversations work best as dialogues, not monologues, and if yours always revolves around your work, your life, and your relationships, you’re probably talking too much and not listening at all. When you’re engaged in a conversation, picture a seesaw in your mind, and remember the fun is in the up and down.

CHALLENGE: To let others participate in the conversation.

STRATEGIES:

- Ask about them. Make a point to see how others are doing before you start in about your own interests and concerns. Just as when you start a letter (“Dear Mom, How are you doing?”), it’s the polite thing to do.

Also, this way you won’t have to remember to ask them later.

Also, this way you won’t have to remember to ask them later.

- Listen for the me-me-me words. If you constantly say I, me, and my, try to use you and yours more often. (Avoid the cliché: “Enough about me. Now, what do you think about me?”)

- Ask questions. Come up with some questions that would apply to most anyone you’re talking with: “What was the best thing you did today?” “How is your family doing?” “Did you have a good day at work?” Aside from allowing back-and-forth banter, this helps you focus on someone besides yourself.

In and Out

A characteristic of both inattentive and hyperactive ADHD is an attention span that drifts from one thing to the next without any warning. This trait causes people to tune in and out during conversations, to miss important information, and be accused of selective hearing. It’s especially detrimental at work, when the person talking is your boss.

CHALLENGE: To gather information from a conversation.

STRATEGIES:

- Say it again. Before beginning an assignment at work, repeat what you’ve heard to make sure you understand correctly and have all the information.

- Take notes. If you’re in a meeting or conversation at work, write down the information you hear. The act of writing will help you listen.

- Tape record conversations, if possible.

- Echo conversations. Ask those you talk with regularly to have you repeat what they’ve said to you.

[Get This Free Guide: 6 Ways to Retain Focus (When Your Brain Says ‘No!’)]

SUPPORT ADDITUDE

Thank you for reading ADDitude. To support our mission of providing ADHD education and support, please consider subscribing. Your readership and support help make our content and outreach possible. Thank you.

Previous Article Next Article

Reasons You Don't Listen I Psych Central

Listening is a part of our waking hours, but sometimes it’s easy to tune out. Understanding why you’re not listening well and how to improve your listening skills can open your ears to hear more.

Understanding why you’re not listening well and how to improve your listening skills can open your ears to hear more.

Every day we hear words coming out of people’s mouths. However, listening to those words is different than just hearing them.

According to the Oxford English dictionary, the word “hear” is defined as “perceive with the ear the sound made by (someone or something),” whereas the word “listen” is defined as “make an effort to hear something; be alert and ready to hear something.”

“Listening is hard work,” Michael P Nichols, PhD, professor of psychological sciences and author of “The Lost Art of Listening,” says. “It takes concentration and effort and self-restraint.”

While it’s not necessary to listen with concentrated attention all the time – such as during casual conversations – Nichols says that listening is important when talking with people you care about or when someone is talking about something they care about.

“Then you need to listen with effort,” Nichols says. “When someone is talking about something important to them, or they are moved by strong feelings, they need to be listened to more carefully.”

“When someone is talking about something important to them, or they are moved by strong feelings, they need to be listened to more carefully.”

Understanding why people don’t listen can help improve your listening skills. Here are few to consider.

You have the urge to tell your story

When someone is talking, Nichols says, instead of listening, we want to talk about what’s on our mind.

“We frequently interrupt to tell a similar story or say something about our own experience,” Nichols states. “It’s a natural impulse, but it needs to be restrained if someone is talking, and they need to be listened to.”

You want to give advice

When someone is sharing something that is upsetting or if the person talking is unhappy, it can be uncomfortable to listen to them. In hopes of getting the person to feel better, so you don’t have to feel uncomfortable, you might be inclined to tell them how to solve their unhappiness or tell them not to feel upset.

“We know that it’s not OK to say something like, ‘Well, if your dog died, why don’t you go out and get a new one?’ but we get around to that eventually,” says Nichols.

You just want everything to be OK

Because it’s unpleasant to be around someone frustrated or upset, especially if you care about the person, Nichols says you might tend to want to make their pain or frustration go away rather than sit with them in their pain.

For example, if someone tells you they lost a job or were diagnosed with an illness, rather than listening to the details of their situation, he says people tend to say things like, “You’ll get through this” or “Things will look up.”

You react emotionally

If you are being criticized, emotions are triggered, and it is natural to get defensive and not listen to what the person is saying.

This can also happen if a person is talking about something you don’t agree with.

“For instance, if I tell you, I wouldn’t get vaccinated because it’s a government hoax, this might make you upset, and you might fire back right away without listening to my entire reasoning,” states Nichols. “It might be better if you hear me out and then acknowledge what I’m saying before saying your opinion. ”

”

You’re bored

Even if someone is talking about something that feels important to them, it might not be interesting or important to you. Feeling bored can make it harder to tap into your listening skills.

Nichols adds, “One of the reasons people get bored is that they listen without interest and passively. So, if someone is talking to you, ask questions and get involved in the conversation.”

You’re distracted

Distractions – internal or external – are sometimes hard to ignore.

How many of us will turn our heads when we hear a loud noise? If you’re watching an action film with lots of explosions and car chases, it’s pretty hard to carry on a conversation at the same time.

Loud noises aren’t the only distractions, either. Sometimes instead of listening, we might find our minds wandering to things we need to do later.

While someone is talking, you might be occupied thinking about what you’re going to cook for dinner or what time the pharmacy or dry cleaner closes.

To focus on the person when they’re talking, it’s important to get rid of both internal and external distractions.

You think you know what people are thinking

While people tend to think they communicate better with close friends than with strangers, an older study found that sociologists believe that closeness can lead to closeness-communication bias – an overestimation of how you communicate.

As a result, sociologists suggest that people actively pay attention to strangers’ perspectives because they don’t know them well. However, when it comes to a friend, they rely more on their own perspective or assume that they always understand what they are saying because they know the person.

“If you are close to someone, you think you know what they’re going to say, so you tend to interrupt and say, ‘Yeah, I know what you mean,’ or you don’t hear them out,” says Nichols.

If you’re looking to improve how you listen, the following tips can be helpful.

Realize it takes effort

Understanding that listening, not just hearing, takes hard work is the first step to becoming a better listener, says Nichols.

“When someone is talking about something important, [consider] making an effort to understand not only what they are saying, but what they are trying to express,” he encourages.

Empathize with the person

When someone is talking, try to acknowledge what the person is saying with a brief empathic comment.

“Often punctuated with an exclamation point like, ‘Oh man!’ or ‘Gee, that’s a shame!’” says Nichols.

Invite more conversation

A good listener will ask questions that encourage the person to expand on what they are sharing.

“Questions designed not to be a detective, but rather to invite the person to say more,” says Nichols.

Phrases like, “Tell me more about that,” or “How did that happen?” can keep the conversation going.

Acknowledge you are listening

Repeating back what you think the person is saying can let them know you’re making the effort to understand them.

“People often acknowledge with a brief statement that says, ‘I know exactly what you mean,’ which suggests you’re really saying, ‘I got it. Let’s move on,’” states Nichols.

Let’s move on,’” states Nichols.

He suggests using phrases that show you are trying to understand but want to make sure you do, like, “OK, so you’re saying we shouldn’t get a vaccine. Do I have that right?” or “Is it the way he talked to you that upset you?”

Don’t overdo body language

While many people think direct eye contact, nodding, and making sounds like ‘ooh’ and ‘aah’ show someone you are listening to them, Nichols warns that overdoing this can look insincere.

“All those are motivated by the desire to look like you’re a good listener, but if you do listen well, maybe you nod and make eye contact, but making a point of it is saying, ‘Look at me; I’m a good listener,” he suggests.

Try not to multitask

While the urge to multitask is always there, consider putting activities like scrolling on your phone, cleaning the dishes, and others on hold when someone is talking with you.

“If you care about someone, pay attention to them and what they are saying,” says Nichols.

However, when it comes to technology and communication, such as texts and emails from family and friends, he adds that failing to respond can come across as not listening.

“Try to answer and acknowledge tasks. [Consider] responding no matter what they said. It makes people feel understood,” Nichols says.

Practice mindful listening

Practicing mindfulness helps you stay present. This practice isn’t useful only for meditation and lowering stress. It can also help you become a more active listener.

If you tend to zone out when listening, practicing mindful listening will help you learn to focus on what the person is saying without distractions.

Before you start your conversation, remove all distractions such as phones, electronic devices, or computers. If you’re watching a movie, turn it off and turn your attention to the person who’s talking. Take the time while you’re silencing or shutting off your electronics to practice some deep breathing techniques to help prepare yourself to listen.

When you train your mind to become more focused in the moment, you will learn to listen more effectively.

Listening is hard work and takes effort, however, there are ways you can learn to become a better listener.

The influence of music on a person: memory, concentration and intelligence

How the brain of professional musicians differs from the brain of amateur musicians and what is wrong with the "Mozart effect" - in the chapter from the book "Music and the brain"

Listening to music is not only nice, but also useful. Music has the ability to influence our emotions, so singing and even just listening to songs can make it easier to deal with mood disorders, depression, anxiety disorders, and other mental health issues. Many researchers believe that music can affect different parts of the brain and improve its individual functions due to neuroplasticity. Norwegian professors of neuroscience of music Are Brean and Geir Ulve Skeie talk about whether it really has an effect on memory, willpower and other cognitive abilities.

RBC Trends publishes a chapter from the book Music and the Brain. How music affects emotions, health and intelligence. The material was prepared in collaboration with the Alpina Publisher publishing house.

Executive functions

Executive functions are processes in the brain that are responsible for cognitive control (that is, attention, concentration, the ability to resist temptation), working memory, and mental flexibility (the ability to quickly switch attention between different tasks). These abilities are controlled by the frontal lobes - thanks to them we are able to focus on ends and means and change behavior with the help of willpower, based on changes in the external environment.

Learning to play a musical instrument requires the development of precisely such qualities as focusing attention, working memory, the ability to switch attention between different tasks (reading notes, interacting with other musicians, solving complex technical problems), as well as endurance. Music education really has an effect on these qualities. For example, one study showed improvement in children's executive function as early as day 20 of class. Another study found that children who were exposed to music for 18 months had an increase in working memory when compared to a control group who had a general science program during the same period (Roden-led study, 2012). But again, it is very difficult to distinguish the effect that the music has, from the overall effect that is achieved through systematic practice.

Music education really has an effect on these qualities. For example, one study showed improvement in children's executive function as early as day 20 of class. Another study found that children who were exposed to music for 18 months had an increase in working memory when compared to a control group who had a general science program during the same period (Roden-led study, 2012). But again, it is very difficult to distinguish the effect that the music has, from the overall effect that is achieved through systematic practice.

Intelligence and education

There is documented evidence that, on average, people who have studied music have a higher level of education and IQ. But what caused this connection? Can one common hidden factor (for example, the socioeconomic status of parents) explain both phenomena - or is there a direct relationship between intelligence and musicality, independent of other factors? There are still no answers to these questions.

Canadian psychologist Professor E. Glenn Schellenberg has attempted to adjust for the socioeconomic background of parents in several studies. He found a positive correlation between music learning and IQ in children aged 6-11, as well as an association between childhood music learning, IQ and academic achievement in young people. There have been a number of long-term studies in which children were observed over time. These studies showed the same results. Apparently, learning music does have a positive effect on overall IQ levels, as well as on academic success. Most researchers believe that music education directly affects executive functions. There's a good reason for this: learning to play music places great demands on a child and develops hand-eye coordination, as well as the ability to concentrate on something for long periods of time, attention, and working memory. This results in measurable changes in the child's body, such as an increase in the size of the corpus callosum, which improves communication between the hemispheres.

Glenn Schellenberg has attempted to adjust for the socioeconomic background of parents in several studies. He found a positive correlation between music learning and IQ in children aged 6-11, as well as an association between childhood music learning, IQ and academic achievement in young people. There have been a number of long-term studies in which children were observed over time. These studies showed the same results. Apparently, learning music does have a positive effect on overall IQ levels, as well as on academic success. Most researchers believe that music education directly affects executive functions. There's a good reason for this: learning to play music places great demands on a child and develops hand-eye coordination, as well as the ability to concentrate on something for long periods of time, attention, and working memory. This results in measurable changes in the child's body, such as an increase in the size of the corpus callosum, which improves communication between the hemispheres. In addition, it is likely that early music education gives the child the experience that intellectual work, which requires concentration, endurance and constant practice, brings joy and positive results. This experience increases the likelihood that the child will work harder at school and decide to devote more attention to learning in the future.

In addition, it is likely that early music education gives the child the experience that intellectual work, which requires concentration, endurance and constant practice, brings joy and positive results. This experience increases the likelihood that the child will work harder at school and decide to devote more attention to learning in the future.

The effect of playing a musical instrument in childhood and adolescence lasts for a long time. Hanna-Pladdy and McKay's study included people aged 60 to 83. It turned out that those who played in the orchestra for more than 10 years in childhood and adolescence, on average, have a better memory, in addition, they also visually perceive space better than people who did not have such experience. Musicians do not lose their abilities. But it's never too late to start learning music - even if you didn't play it as a child. A study of people between the ages of 65 and 80 who only started learning to play the piano at that age found that after six months they had significantly improved working memory, motor skills, and tempo of perception. Their results were compared with the results of a group of those who were engaged in other activities (for example, exercise and painting). In 2014, a group of Swedish scientists led by Balbag examined 157 age-related pairs of twins. It turned out that those who played a musical instrument all their lives were much less likely to develop dementia in old age than their siblings who had never played music.

Their results were compared with the results of a group of those who were engaged in other activities (for example, exercise and painting). In 2014, a group of Swedish scientists led by Balbag examined 157 age-related pairs of twins. It turned out that those who played a musical instrument all their lives were much less likely to develop dementia in old age than their siblings who had never played music.

Brain age can be determined using MRI. Scientists examined the MRI of the brains of patients stored in the database, deriving some average indicators characteristic of different ages. And then compared these indicators with the chronological age of the subjects. This is a bit like an age calculator: you need to enter your resting heart rate, height, weight, waist circumference, and so on, and you will get your biological age, which can be very different from chronological. In 2018, a team of researchers led by Rogenmoser compared the brains of professional musicians, amateur musicians, and those who had never played music. It turned out that, on average, the brains of the musicians were younger (that is, looked younger on MRI images) of the subject's real age. However, according to the results of the study, the dependence of the type of youthfulness of the brain on the number of music lessons was not revealed at all. It turned out that the brain of amateur musicians is the youngest. Professional musicians had younger brains, on average, but to a lesser extent. The results sparked a debate: maybe a professional musician is under so much stress that he reduces the positive effect of music lessons? And does the amateur musician benefit from other intellectual tasks that arise during the working day? Research has shown that a variety of activities is more beneficial than monotony for stimulating the brain. And this also applies to music.

It turned out that, on average, the brains of the musicians were younger (that is, looked younger on MRI images) of the subject's real age. However, according to the results of the study, the dependence of the type of youthfulness of the brain on the number of music lessons was not revealed at all. It turned out that the brain of amateur musicians is the youngest. Professional musicians had younger brains, on average, but to a lesser extent. The results sparked a debate: maybe a professional musician is under so much stress that he reduces the positive effect of music lessons? And does the amateur musician benefit from other intellectual tasks that arise during the working day? Research has shown that a variety of activities is more beneficial than monotony for stimulating the brain. And this also applies to music.

Mozart effect

In 1993, Frances Rauscher published the results of an experiment in Nature. He is often cited as an example when it is said that music is theoretically capable of producing a distant transfer effect. One group of young people listened to Mozart's Sonata in D Major for Two Pianos (K. 448) for 10 minutes. The second group listened to relaxing music, while the third group sat in silence. The groups changed places, and each subject ended up in all three conditions. After each stage of the experiment, the subjects were instructed to mentally fold and cut a sheet of paper, and then imagine what shape the object would be if the sheet was folded again. Tasks of this kind test the ability to spatial perception and are included in all tests to test the level of intelligence. Rauscher found that young people performed best on the task after listening to Mozart, with an increase in IQ of about 8 points. The results were immediately published in the media under headlines like "Mozart will make you smarter" - and now the phrase "Mozart effect" has become a term.

One group of young people listened to Mozart's Sonata in D Major for Two Pianos (K. 448) for 10 minutes. The second group listened to relaxing music, while the third group sat in silence. The groups changed places, and each subject ended up in all three conditions. After each stage of the experiment, the subjects were instructed to mentally fold and cut a sheet of paper, and then imagine what shape the object would be if the sheet was folded again. Tasks of this kind test the ability to spatial perception and are included in all tests to test the level of intelligence. Rauscher found that young people performed best on the task after listening to Mozart, with an increase in IQ of about 8 points. The results were immediately published in the media under headlines like "Mozart will make you smarter" - and now the phrase "Mozart effect" has become a term.

But let's take our time and think, isn't there anything strange about the form of the research itself? The chosen work of Mozart is able to cheer up and invigorate a person and, of course, is very different from relaxing music or complete silence (from which we become lethargic). In addition, such tasks are considered one of the most difficult in tests to determine the level of intelligence. A high level of concentration and intellectual effort is also required, and there is ample evidence of how much arousal and mood affect the ability to perform complex intellectual tasks. Positive emotions increase the amount of dopamine in the prefrontal cortex. According to a relatively new theory, it is this fact that explains why subjects perform many cognitive tasks much faster and more successfully in the presence of mental stimulation. Perhaps the decisive factor in the question of how all groups coped with the task was precisely the level of arousal, as well as the ability to apply some kind of effort associated with it?

In addition, such tasks are considered one of the most difficult in tests to determine the level of intelligence. A high level of concentration and intellectual effort is also required, and there is ample evidence of how much arousal and mood affect the ability to perform complex intellectual tasks. Positive emotions increase the amount of dopamine in the prefrontal cortex. According to a relatively new theory, it is this fact that explains why subjects perform many cognitive tasks much faster and more successfully in the presence of mental stimulation. Perhaps the decisive factor in the question of how all groups coped with the task was precisely the level of arousal, as well as the ability to apply some kind of effort associated with it?

In the years that followed, countless researchers tried to test and challenge Frances Rauscher's results. In a 1999 experiment, Nantais and Schellenberg gave three groups IQ tasks after listening to the same piece by Mozart, a piano piece by Schubert, and an audiotape with the voice of an announcer. According to the results of this experiment, no difference was found in the results obtained from different groups. In addition, when the subjects were asked what they liked more - Mozart, Schubert, or the story told by the announcer, a surprising pattern was revealed. Those who liked Mozart did better on the task after listening to Mozart, and those who liked Schubert or the story told by the announcer, respectively, did better after listening to them.

According to the results of this experiment, no difference was found in the results obtained from different groups. In addition, when the subjects were asked what they liked more - Mozart, Schubert, or the story told by the announcer, a surprising pattern was revealed. Those who liked Mozart did better on the task after listening to Mozart, and those who liked Schubert or the story told by the announcer, respectively, did better after listening to them.

Another test was carried out by a research group led by Thompson (2001). The scientists chose Albinoni's Adagio, a slow and melancholy work, to work with. The subjects performed better after the Mozart sonata than after sitting in silence, and after Albinoni and silence, no difference was found in how well the task was performed. And as soon as the researchers began to monitor the level of arousal and mood of the subjects, the Mozart effect completely disappeared. Experiments were also carried out on children aged 10–12 years. They were more affected by popular tunes than by Mozart, but only for a short time. As a result, in all such studies, the effect of both Mozart and other music was very short-lived. No experiment has ever proven that music can have a lasting effect on the ability to solve intellectual problems.

As a result, in all such studies, the effect of both Mozart and other music was very short-lived. No experiment has ever proven that music can have a lasting effect on the ability to solve intellectual problems.

In general, one can refute the fact that music has a special influence on the human intellect. However, it is not surprising that all of these studies have highlighted the unusual ability of music to influence our emotions. But many of us need music precisely to cheer up or calm down, relax or have fun, rejoice or mourn. This is the magic of music - and perhaps this is the very Mozart effect.

Four main questions about music and depression

Does listening to music help with depression?

A native iPod with a library studied inside and out, or a streaming service with thousands of playlists, on the covers of which there are rain-splattered windows, gloomy silhouettes and other clichéd images of sadness ... What person has not resorted to this elementary therapy at least once in sad moments?

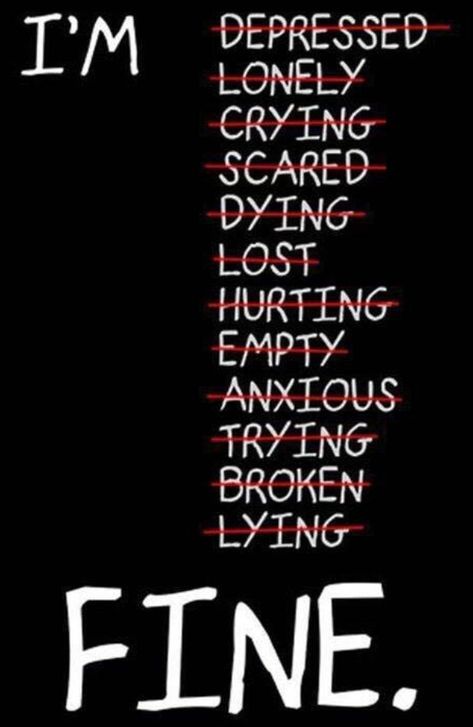

Many people think that the right songs really help. Hearing just a few exact lines, a person feels in this acceptance of his feelings and support. For some, it is easier to understand yourself and consider your problems from the outside. It is sometimes even encouraging that some strangers put together several sounds in such a way that they fit exactly into your mood and allowed you to mourn. But these simple ways are more relevant in the fight against the usual bad mood. And can listening to music help those whose problem is a serious illness that requires treatment?

Hearing just a few exact lines, a person feels in this acceptance of his feelings and support. For some, it is easier to understand yourself and consider your problems from the outside. It is sometimes even encouraging that some strangers put together several sounds in such a way that they fit exactly into your mood and allowed you to mourn. But these simple ways are more relevant in the fight against the usual bad mood. And can listening to music help those whose problem is a serious illness that requires treatment?

At the moment there is no clear answer to this question. Some researchers emphasize the positive role of music in the treatment of depression when used in combination with other standard methods. Others believe that listening to music not only does not weaken, but even provokes and aggravates the disease.

Music therapy is not a new idea. It is used with a wide range of patients, such as children who have developmental or mental disorders, and older people who develop Alzheimer's disease. This method can include listening, creating music, discussing it, and even dancing. Not every song you turn on will be healing. Music therapy is done by specially trained people who know a lot of not only musical, but also psychological and biological subtleties.

This method can include listening, creating music, discussing it, and even dancing. Not every song you turn on will be healing. Music therapy is done by specially trained people who know a lot of not only musical, but also psychological and biological subtleties.

Some have suggested that music therapy is also effective in helping people with depression. Scientists at the Cochrane Library found and analyzed five studies on this topic. Four of them showed positive results. People who received music therapy recovered faster than those who were not attracted to it.

Unfortunately, the samples of these studies were small and the quality was inconclusive, so the question remained open. However, it was clear that the effect of listening to music on the treatment of depression is possible and deserves further study. This is what the Cochrane Library has done. And in November 2017, she presented a new work, summing up nine studies already, in which 421 people of different ages took part. The conclusions were confirmed, albeit with the same caveat. The researchers suggested that listening to music could enhance the effect of conventional therapy on patients with depressive and anxiety disorders.

The conclusions were confirmed, albeit with the same caveat. The researchers suggested that listening to music could enhance the effect of conventional therapy on patients with depressive and anxiety disorders.

If we take not music therapy accompanied by a professional, but everyday, independent listening, then here everything is still less clear. Dr. Sandra Garrido, who studies psychology and music, believes that some compositions can even harm those suffering from depression.

In her experiment, she divided people prone to clinical depression from the rest of the study participants, and broke the music into “happy” and “sad”. Each person chose suitable tracks for himself, since the perception of music is very subjective. It turned out that the melancholy compositions, according to the researchers, depressed the depressive group more, although all participants in the experiment were sure that they actually got better.

Garrido believes that people suffering from depression often have an increased level of rumination, that is, obsessive thinking about the same topics. Therefore, they perceive sad music differently. It causes them to get stuck in negative thought patterns and instead of being a defense mechanism, it becomes a source of additional problems. A healthy person who has just gone through a breakup and listens to Someone Like You Adele will burst into tears, let these emotions out, become a little stronger from this and just move on with life. A depressed person, on the other hand, will focus on other things, such as how relationships always end in disappointment for him and how no one will ever love him again, and only get deeper into his condition.

Therefore, they perceive sad music differently. It causes them to get stuck in negative thought patterns and instead of being a defense mechanism, it becomes a source of additional problems. A healthy person who has just gone through a breakup and listens to Someone Like You Adele will burst into tears, let these emotions out, become a little stronger from this and just move on with life. A depressed person, on the other hand, will focus on other things, such as how relationships always end in disappointment for him and how no one will ever love him again, and only get deeper into his condition.

There are still a lot of unexplored and incomprehensible things in this topic, which Garrido herself admits. Some fair questions and expressions of disagreement with the results of the experiment were already voiced in the comments to the article on her research in The Conversation. The mechanism of influence of sad lyrics is more or less clear, but what about, in fact, the saddest music? Will the effect be different from the same songs where the vocal track is removed? But what about originally instrumental music or compositions performed in a language that the person listening to them does not know?

Not all people who know well what depression is and read Garrido's article agree that sad music is a deceptive defense mechanism. Many agree that sometimes this deterioration is just what is needed in order to experience a kind of catharsis and ultimately feel better. As they say, you need to reach the bottom, because from there there is only one way back up. “As a depressed person who has to live and work in a world where there is no time or space to suffer from depression, I can say that this focus on escalating crises and running them through me for years has allowed me to be always in working order,” writes Meg Thornton. "So while I may 'feel worse' after sad music, the question is whether 'worse' is good or bad for me."

Many agree that sometimes this deterioration is just what is needed in order to experience a kind of catharsis and ultimately feel better. As they say, you need to reach the bottom, because from there there is only one way back up. “As a depressed person who has to live and work in a world where there is no time or space to suffer from depression, I can say that this focus on escalating crises and running them through me for years has allowed me to be always in working order,” writes Meg Thornton. "So while I may 'feel worse' after sad music, the question is whether 'worse' is good or bad for me."

One Stephen Peabody agrees with her and adds: "And isn't the point of psychotherapy that it helps you get in touch with your thoughts and feelings so that you can process them and find a way out, instead of helping you not to think about them?"

These are reasonable remarks. But let us turn to the experience of those for whom certain music has really become a bad habit. Journalist Sarah Kurchak, who, she says, suffers from "two equally severe mental illnesses (depression and musical addiction)", in an article for Noisey told how Joy Division turned for her from a lifeline into a burden pulling to the bottom. “At some point,” she writes, “the very things that I loved so much about this group became things that pulled me deeper and deeper into despair. (…) I began to identify myself too much with the texts of Curtis and with the portrait of him that his widow Deborah portrayed in the book Touching From a Distance. The only way out I saw in his art and life was death."

“At some point,” she writes, “the very things that I loved so much about this group became things that pulled me deeper and deeper into despair. (…) I began to identify myself too much with the texts of Curtis and with the portrait of him that his widow Deborah portrayed in the book Touching From a Distance. The only way out I saw in his art and life was death."

Ultimately, Sarah took the advice of her therapist, who said that she didn't have to continue listening to them. So she did, and after a while she realized that the doctor was right. Even though she missed some of the songs, she couldn't bring herself to even listen to their first few seconds. “Now I understand that relationships with a group can be just as toxic and unhappy as between people. And sometimes, despite all your history, you have to leave before your love for them tears you to pieces,” she says and admits that she hasn’t listened to Joy Division for several years.

Photo - Mary Mary

Sarah's case reminds us that another interesting topic awaits researchers within the framework of this issue - the impact of musical fandoms on human mental health. In this case, music becomes more than just music for a person. For him, this is already a more voluminous, multifaceted and emotionally significant experience, which is definitely capable of influencing a person’s personality, his views, mood and life in general.

In this case, music becomes more than just music for a person. For him, this is already a more voluminous, multifaceted and emotionally significant experience, which is definitely capable of influencing a person’s personality, his views, mood and life in general.

On the one hand, it is clear to almost anyone how much joy, inspiration and vivid emotions such an intense passion can give. Fandoms bring together like-minded people who, as a rule, share not only musical, but also other interests and values. Connecting with like-minded people brings positive emotions, gives rise to an important sense of community and helps to make new friends. With regard to fans suffering from depression, it is worth noting separately the case when the idol himself also struggles with this problem and talks about it. When a public person, especially one who is a role model for many, talks about his depression, it gives strength to those who are afraid to discuss this problem with loved ones and seek help.

But, of course, the negative effects of fandoms are visible to the naked eye. Sometimes they become the right environment for turning a harmless hobby into an unhealthy addiction. It happens in fandoms and bullying, toxic people, herd rules and requirements, for non-compliance with which the crowd can get angry. In the end, no one is immune from disappointment in idols. The collapse of ideals is experienced hard, especially if before that the whole world of a person, his whole personality and social circle were formed around one group. And such dissolution in idols, when there is simply nothing else in a person’s life, is also not quite healthy behavior.

Interaction between a person and a fandom is a very broad and topical topic. It remains only to wait for studies that will analyze all its aspects.

Some believe that not only a certain group that is of great importance to a person on a personal level, but also music addiction itself can plunge into depression. Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine studied 106 teenagers, including 26 with clinical depression, and what media they regularly consume. It turned out that those who listened to a lot of music are most prone to depression, while book lovers are the least prone to it. The influence of other media forms (magazines, films, games, and even the Internet) on the predisposition to depression could not be established. But there is an important note here as well. "At this point, it's not clear if depressed people start listening to more music to escape reality, or if listening to more music can lead to depression, or both," said Dr. Brian Primak, author of the study.

Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine studied 106 teenagers, including 26 with clinical depression, and what media they regularly consume. It turned out that those who listened to a lot of music are most prone to depression, while book lovers are the least prone to it. The influence of other media forms (magazines, films, games, and even the Internet) on the predisposition to depression could not be established. But there is an important note here as well. "At this point, it's not clear if depressed people start listening to more music to escape reality, or if listening to more music can lead to depression, or both," said Dr. Brian Primak, author of the study.

So far, only one thing can be said with certainty: everything is very complex and individual. There are so many different factors involved in this question (the character of a person, the severity of his condition, sensitivity to music, the model of its perception, personal attitude to specific compositions, and so on) that an unambiguous answer is hardly possible in principle. However, music therapy as a type of treatment may well bring positive changes if used in a complex way.

However, music therapy as a type of treatment may well bring positive changes if used in a complex way.

Does writing and performing music help with depression?

Making music is another recognized form of music therapy. This, unlike ordinary listening to music, is a more active method, involving the creation of something new. It is much easier to understand this concept and admit its existence, even for those who have never composed songs or played musical instruments themselves. Who among us does not know how pleasant it is to do something with our own hands and how many positive emotions any creativity gives?

Reinforcing confidence in the miraculous effect of songwriting on depression and the musicians themselves. Remember how many times you read in album announcements artist revelations like “working on this record saved me / helped me a lot”? Or heard in interviews how they compare songwriting to psychotherapy and even exorcism?

This question is, of course, closely related to the previous one. On the other hand, there are reasons to believe that here a positive answer may be closer and more definite.

On the other hand, there are reasons to believe that here a positive answer may be closer and more definite.

In 2011, Finnish scientists conducted an experiment to test whether music therapy could help treat depression. It involved 79 people, all of whom received standard therapy (communication with a specialist and medication), and only 33 of them also engaged in music therapy, such as playing drums. After three months, this group's depression and anxiety scores improved more than the other participants in the experiment.

"Our study showed that music therapy added to standard care helps people reduce their rates of depression and anxiety," said Professor Christian Gold, one of the study's authors. “There are certain qualities in music therapy that allow people to express themselves and interact non-verbally, even in situations where they cannot find words to describe their inner experiences.”

A larger (total of 251 people), although focused only on children and adolescents, study on this topic was conducted in 2016. It was conducted by researchers from Queen's University Belfast and Bournemouth University. The music therapy group played different instruments of their choice, performed vocal improvisations, and simply moved to the music. The results were confirmed: these girls and boys showed a reduction in depression, as well as the development of communication skills and self-esteem.

It was conducted by researchers from Queen's University Belfast and Bournemouth University. The music therapy group played different instruments of their choice, performed vocal improvisations, and simply moved to the music. The results were confirmed: these girls and boys showed a reduction in depression, as well as the development of communication skills and self-esteem.

These and similar studies concern music therapy specifically as a therapeutic technique, which is carried out only under the supervision of a specialist. It helps a person to direct creative energy in the right direction. Some people find it difficult to open up and express their thoughts. Composing music on doctor's orders, they dig into their unconscious, where the answers to the right questions are often hidden, and release their experiences through means that allow greater freedom of expression. In addition, music is great at evoking memories, which can also be the key to solving the problem.

Is it possible to measure the effectiveness of such treatment in natural conditions, without an experienced consultant over the soul? Many great musicians didn't have any special therapist, and still writing songs helped them to overcome difficult life periods. It's hard to say for sure. But it is obvious that creating music can at least alleviate depression.

It's hard to say for sure. But it is obvious that creating music can at least alleviate depression.

Photo - Mary Mary

Songwriting is often like keeping a diary. The author expresses his feelings in them, returns to strong memories, pulls out of the wilds of the soul all the most important and disturbing. Even if the writer is not inclined to very personal creativity, the result of his work will still bear the imprint of his person and touch on issues that somehow hurt him. Even if he sings on behalf of a fictional lyrical hero, and there will not be a drop of reality in the plot, it is almost impossible to completely discard a personal moment. And in most cases, the compositions are somehow autobiographical, that is, they look like entries in a diary.

A lot has been said about the benefits of keeping a diary for people suffering from depression. James Pennebaker has been researching this topic for about 40 years. His experiments showed that people who regularly wrote about events that affected them or even had a strong negative effect on them began to feel better. You can conduct such a confession in different forms: someone writes letters not intended for sending to relatives and friends, others record their monologues on a dictaphone. This means that music is just another tool, the chances of achieving a similar effect from which - especially in combination with traditional methods of treatment - are quite high.

You can conduct such a confession in different forms: someone writes letters not intended for sending to relatives and friends, others record their monologues on a dictaphone. This means that music is just another tool, the chances of achieving a similar effect from which - especially in combination with traditional methods of treatment - are quite high.

And composing instrumental music will obviously not be in vain. What is so attractive about music therapy? Partly by the fact that a person moves his problems to another space in which it may be easier for him to admit them to himself and analyze them sensibly. Moreover, from composing any music, a person will also receive aesthetic pleasure and rejoice at his small achievements, which can be quite difficult during depression. “Creative effort is really very rewarding,” says Shelley Carson, a professor at Harvard University, “and you get small doses of dopamine in your brain’s reward center.”

Simply put, composing music is not exactly a magic pill for depression, but it is quite capable of helping with some symptoms as part of traditional treatment.

Are musicians more susceptible to depression than others?

Mental illness is being talked about more openly these days, with many celebrities venturing out about their own battles with depression. There are quite a few musicians among them, and some have found the courage to share their experiences with the world even before the rise of a frank conversation about this topic. Not so long ago, music lovers were shocked by the deaths of Chris Cornell and Chester Bennington. Long before that, they talked about their long battle with depression. Unfortunately, the disease won, and the musicians committed suicide. And these are far from the only examples of such a tragic ending. The victims of depression were, for example, Ian Curtis and Nick Drake.

Even those artists who (at least openly) have never spoken about the existence of this problem in their lives sometimes seem to us to be prone to dark moods and introspection. We believe that a person simply could not capture the nuances of spiritual darkness so subtly and accurately if he had not been in it himself.

In a word, it is easy to see that musical talent and a tendency to depression are mystically connected and the first almost necessarily goes along with the second. How is this apparent connection explained, and does it really exist? Perhaps this is only a consequence of the fact that we remember only a few celebrities who fit this idea, but do not see and do not take into account how a much larger number of ordinary people around us are struggling with depression?

The British charity Help Musicians UK conducted the largest ever study on the mental health of musicians in 2016. Its authors found that musicians (regardless of genre) suffer from depression and anxiety three times more often than others. However, the reason for this, according to researchers, is not at all in an innate predisposition.

“Music making has a therapeutic effect, but a career in music is destructive,” the researchers concluded after considering the responses of respondents. Among them were not only touring and performing artists, but also songwriters, DJs, producers, live musicians and other people working in this field. It was the industry itself, its rules, difficult conditions, and intense stress that caused a huge proportion of those surveyed to experience depression, anxiety, and panic attacks.

It was the industry itself, its rules, difficult conditions, and intense stress that caused a huge proportion of those surveyed to experience depression, anxiety, and panic attacks.

The study contains the stories of some of the people who took part in the study. Many say that in music, to get at least a small chance to break through, you need to work hard like in no other industry. Giving all their time and energy to this cause, the musicians work out inhuman hours, are forced to move away from family and friends, spend most of their time on the road and play in often not the most pleasant places just to perform at least somewhere. Even with full dedication, success is by no means guaranteed. Holding on to what they love, musicians live in a state of constant uncertainty, lack of recognition, and often poverty. Sometimes even close people cannot accept their choice and somehow make it clear that it's time to find a "normal job".

For more or less established musicians, the issue of recognition and money, of course, is not so acute. However, they face more tangible pressure: from both labels, which, as a rule, are primarily interested in good income from albums and tours, and not the mental and physical health of artists, and fans, who have many expectations associated with the group, sometimes disproportionate , and who can behave in a straining way, and critics with devastating reviews, and other representatives of the industry, and even just ordinary people, who today are quite easy to fall upon any celebrity with not always justified negativity, up to full-scale bullying. In the end, even from their own side, because creative people are often prone to perfectionism and are looking for ideals that are not feasible in real life.

However, they face more tangible pressure: from both labels, which, as a rule, are primarily interested in good income from albums and tours, and not the mental and physical health of artists, and fans, who have many expectations associated with the group, sometimes disproportionate , and who can behave in a straining way, and critics with devastating reviews, and other representatives of the industry, and even just ordinary people, who today are quite easy to fall upon any celebrity with not always justified negativity, up to full-scale bullying. In the end, even from their own side, because creative people are often prone to perfectionism and are looking for ideals that are not feasible in real life.

It is obvious that the efforts put into work by musicians from the big leagues more often pay off. Yet they, too, face catastrophic exhaustion and harsh conditions, especially on long tours, playing one show after the next and not even being able to recover. This is evidenced, for example, by Moby, who refused to tour in 2016. “There has never been such a thing that I went on tour and did not feel anxiety, depression and insomnia,” the musician said. “In the early days, it seemed like a small price to pay. But at this point in my life, I can't, in my right mind, punish myself, my body, and my mental health for having to go on tour."

“There has never been such a thing that I went on tour and did not feel anxiety, depression and insomnia,” the musician said. “In the early days, it seemed like a small price to pay. But at this point in my life, I can't, in my right mind, punish myself, my body, and my mental health for having to go on tour."

Another problem is that working in the music business is very romanticized. This bright myth has been dreamed of since childhood, representing travel, parties, golden figurines and thousands of devoted fans. But those trials and pressures that come along with all this are not customary to talk about. Especially negative attempts to make this topic more open and talk about its not so pleasant details are perceived by relatively successful musicians. Like, what are you complaining about? You have everything that others can not even dream of, be grateful and shut up! Artists understand this themselves, but not everything is so simple, and in a state of depression it is generally difficult to evaluate what is happening rationally and focus on the positive.

The Help Musicians UK study focuses specifically on the influence of the music industry on the mental health of its participants, and not on pre-existing addictions. Therefore, firstly, it is worth distinguishing between these concepts, and secondly, to recognize that even a person who is not prone to depression can be driven into depression by the music business.

As for the predetermined connection, it apparently still exists and is being actively studied by scientists. But usually in connection not only with musicians, but with creative people in general, that is, also with artists, dancers, photographers, actors, etc. In 2005, the Icelandic company deCODE genetics conducted a study on this topic. It turned out that representatives of creative professions are 25% more likely to have genes that are associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (a condition in which depressive phases alternate with manic ones). “The results of this study are not surprising, because to be creative, you need to think differently,” said study leader Dr. Stefansson.

Stefansson.

"There are over 20 studies that suggest that highly creative people are more likely to have bipolar and depressive disorders," says Kay Redfield Jamison, professor of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins University and author of The Restless Mind. “Of course, I think there is a big connection with the temperaments that are behind bipolar disorder and depression, with the propensity to reflect and so on.”

Paul Verhaegen, professor of psychology at the Georgia Institute of Technology, has also done research on this issue. Also an established writer, he was initially interested on a personal scale in whether creativity was associated with mood disorders. For him, both come from the same source. “When you think about the things that are happening in your life and start thinking about them over and over and over again, this spiral of endless thinking about what is happening to you and the world takes you far away,” he says. “I often start thinking things over and over again, and that’s when I start writing. ”

”

Another common source of creativity and depression seems to be hypersensitivity. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, professor of psychology at Claremont-Gradwaite University, put it this way: “Art is more dangerous [than other professions] because it requires a lot of sensitivity. If you go too far, you can pay the price and become too sensitive to live in this world.

Terrence Ketter, professor of psychiatry at Stanford University, gave a creativity test to a group of depressed and bipolar patients and a healthy group. The former coped with the task 50% better than the latter. Ketter himself admits that the results are not final and the topic requires further research. However, it seems that some connection between a creative character and a depressive character is obvious. "It's hard to argue that engaging in creative tasks can create this particular temperament, and it's perhaps a little more likely that such a temperament provides a creative edge," says Ketter.

One of the opponents of this theory is Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard University Albert Rotenberg. He considers it only a legacy of the romantic 19th century, when it was believed that a person of art, opposed to society, constantly struggles with internal demons. Rothenberg suggests that the known examples of great people who suffered from depression are just coincidences, each of which has far more healthy people, and the available evidence is inconclusive.

He considers it only a legacy of the romantic 19th century, when it was believed that a person of art, opposed to society, constantly struggles with internal demons. Rothenberg suggests that the known examples of great people who suffered from depression are just coincidences, each of which has far more healthy people, and the available evidence is inconclusive.

“The problem is that criteria for creativity are usually not very creative,” he says. – Belonging to a creative society or working in painting or literature does not prove that a person is creative. In fact, many people who have mental disorders actually try to work in positions that involve painting and writing, not because they are good at it, but because they are attracted to it. And that can skew the data.”

There is still no consensus on this topic that has been of interest to the world for a long time. What is clear is that there is definitely no obligatory and dominant innate connection between a tendency to depression and musical talent. The findings of the researchers suggest that perhaps not on such a global scale as previously thought, but there is something in this view.

The findings of the researchers suggest that perhaps not on such a global scale as previously thought, but there is something in this view.

Does depression contribute to musical creativity?

The myths about the mad genius and the suffering creator have been around for centuries. Even the ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus wrote that "wisdom comes through suffering." George Byron often said that "all of us in the [poetic] trade are mad." As a result, we got a very tenacious theory, which is closely related to the previous question, but, in addition to the linkage of these phenomena, also suggests the fruitfulness of this combination. In other words, people believe that a person of art must suffer in order to create, and it is from pain that the best works are born.

This assumption has not bypassed music, and has become especially strong in it. An example of this are the long-gone rock legends, whose turbulent lives were the embodiment of the principle “it is better to burn out quickly than slowly fade away. ” And it began even before them, with such classical composers as, for example, Schumann, Mahler and Rachmaninov. The life of many cult musicians of the 20th century was overshadowed by poverty, difficult childhood, failures, losses, mental trauma and other suffering; many legends suffered from various mental disorders, including depressive ones. By addressing these experiences in their music, they created something so sincere and catchy that these songs began to take on a life of their own.

” And it began even before them, with such classical composers as, for example, Schumann, Mahler and Rachmaninov. The life of many cult musicians of the 20th century was overshadowed by poverty, difficult childhood, failures, losses, mental trauma and other suffering; many legends suffered from various mental disorders, including depressive ones. By addressing these experiences in their music, they created something so sincere and catchy that these songs began to take on a life of their own.

Today we are a little further from romanticized rock myths like the 27 Club, but the legacy of theory lives on. When a musician gives up bad habits, pacifies his inner darkness and generally finds himself in a more favorable state of mind (a striking recent example is Pete Doherty, who returned from rehab to musical activity), in a good half of new reviews or even predictions, that the thought that now he would definitely not write anything as good as it was. The idea reigns that happy and healthy people are no longer ways to create something interesting. Some suggest that without all the hardships experienced by the artist, there would be no music, which means that they are useful to some extent.

Some suggest that without all the hardships experienced by the artist, there would be no music, which means that they are useful to some extent.

The musicians themselves sometimes reinforce the conviction. Here's what Thom Yorke says about writing while depressed: “Sometimes I write music when I'm depressed because I suffer [from depression]. Sometimes it's not even suffering. This is a bonus. I really don't like people who reject our music just because it's depressing. Because from this feeling a great creative force is born.

At the same time, anyone who knows anything about real depression and understands how much it differs from ordinary sadness and momentary blues begins to doubt this myth. Until recently, these concepts were often used interchangeably, and many people are only now learning that depression is not just a bad mood that comes and goes, but its owner sits beautifully by the window in the twilight and deftly generates sad captions for Instagram. This is a disease that can last from a few weeks to a lifetime. One of its symptoms is a loss of motivation. It can be difficult for a depressed person to even get out of bed and cook something to eat, let alone write a song. And even if he drags himself to a musical instrument, he will most likely not last long, will be dissatisfied with the result and will plunge into even more self-loathing in a downward spiral. In the end, deep depression can even lead to the most tragic ending, and not to the pinnacle of creativity. In general, if you think realistically, this is not the most suitable starting point for creativity.

One of its symptoms is a loss of motivation. It can be difficult for a depressed person to even get out of bed and cook something to eat, let alone write a song. And even if he drags himself to a musical instrument, he will most likely not last long, will be dissatisfied with the result and will plunge into even more self-loathing in a downward spiral. In the end, deep depression can even lead to the most tragic ending, and not to the pinnacle of creativity. In general, if you think realistically, this is not the most suitable starting point for creativity.

This myth is one of the consequences of the romanticization of depression and its misunderstanding. Creative people are not always grateful to heaven for such a source of inspiration. For example, Van Gogh, who suffered from bouts of severe depression and became one of the most famous unfortunate creators, was not at all happy about this and wrote in letters to his brother Theo: “Oh, if I could work without this damned disease, what things could I create!" Let's get back to music: the potential of Joy Division could have been revealed, perhaps much more vividly, if Ian Curtis's depression had been recognized in time and the 23-year-old musician would not have committed suicide.

Photo - Mary Mary

Such ideas are harmful primarily to the musicians themselves. Believing that all their best songs are born not from talent and work, but from depression, they are afraid to recognize the disease as a problem and seek help. Some are afraid that, having recovered, they will lose themselves, their individuality and musical abilities.

It is not surprising that now, when the psychological literacy of people began to grow, the attitude towards this theory has become more negative and at least skeptical. At the same time, apparently, this is a slightly more complex question that cannot be answered with a simple “yes” or “no”. Especially considering that the answer to the previous question still tends to be positive.

Here is what Kay Redfield Jamison, who studies the relationship of creativity with bipolar disorder, writes about this (keep in mind that the very essence of what was said is quite relevant for depression): “Most manic-depressive patients do not have an outstanding imagination, and most accomplished creators do not suffer from recurring mood swings. To suggest that such illnesses usually enhance creative talent is only to unfairly support the notion of "mad genius." Even worse, such a generalization simplifies a very serious illness and in some way discredits the personality in art.

To suggest that such illnesses usually enhance creative talent is only to unfairly support the notion of "mad genius." Even worse, such a generalization simplifies a very serious illness and in some way discredits the personality in art.

Yet she admits that it would not be entirely correct to reject this concept completely: "Nevertheless, recent studies show that a large number of accomplished artists - much more than one would expect by chance - fit the diagnostic criteria maniacally - depressive or major depressive disorder specified in DSM-IV. In fact, it seems that these illnesses can sometimes enhance or otherwise promote creativity in some people.”

We have already discussed some ways of such assistance above. Consider, for example, the previous section of the article. The opinions cited in it allow us to say that in some way depression can still be useful for people of creativity. That's just not herself, but those common properties-sources that, according to some researchers, she has with creativity: sensitivity, a tendency to think, being different from others, etc.

And if we go even higher, we remember that composing music has a beneficial effect on the level of depression. Therefore, this process may attract musicians, not because depression itself presses a magic button and sets off a creative salute, but because it helps them feel better. Music is a way of escapism, and it turns out that escaping reality into it can be not only pleasant, but also useful. For a person who is engaged in it and loves this activity, this is an affordable and natural way to release some of the experiences. Such “therapy” is more accessible, cheaper and will not answer with some “you just don’t try” or “get it together, rag”, from which it only becomes harder for a person. Perhaps that is why music and creativity in general attract people who are going through hard times?

What about the fact that clearly something does not fit in the pair "lack of strength and motivation in depression" and "explosion of creative energy"? Harvard University's Shelley Carson, already familiar to us, explains it this way: “Recent research into mood disorders and creativity patterns suggests that it may not be depression itself, but recovery after it that inspires creative work.