Post partum psychosis dsm 5

Essential Reads - Postpartum Psychosis: A Diagnosis for the DSMV

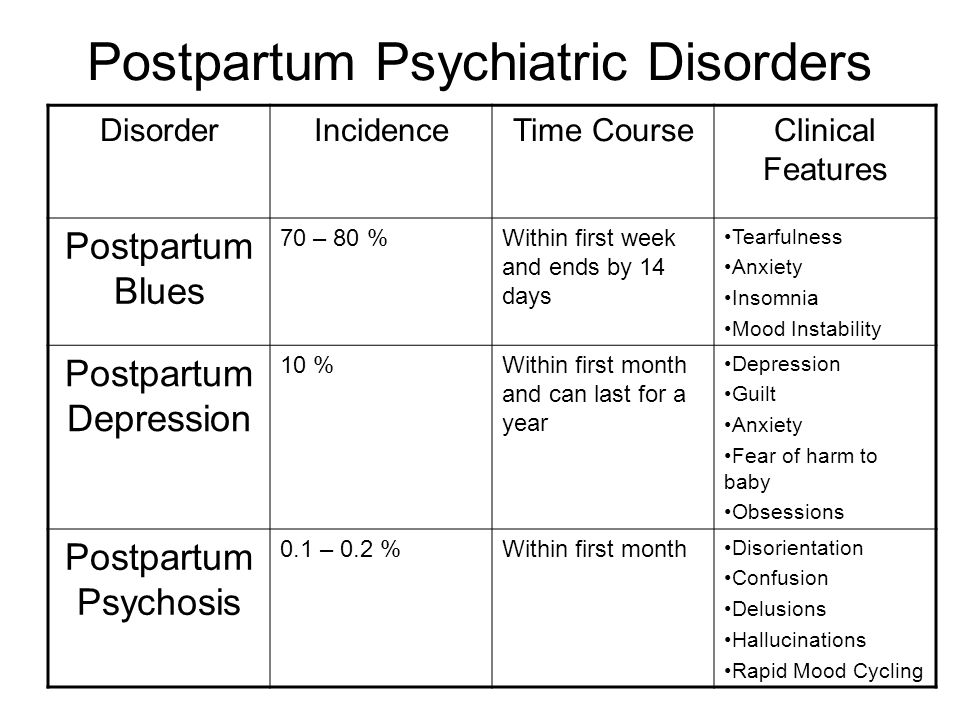

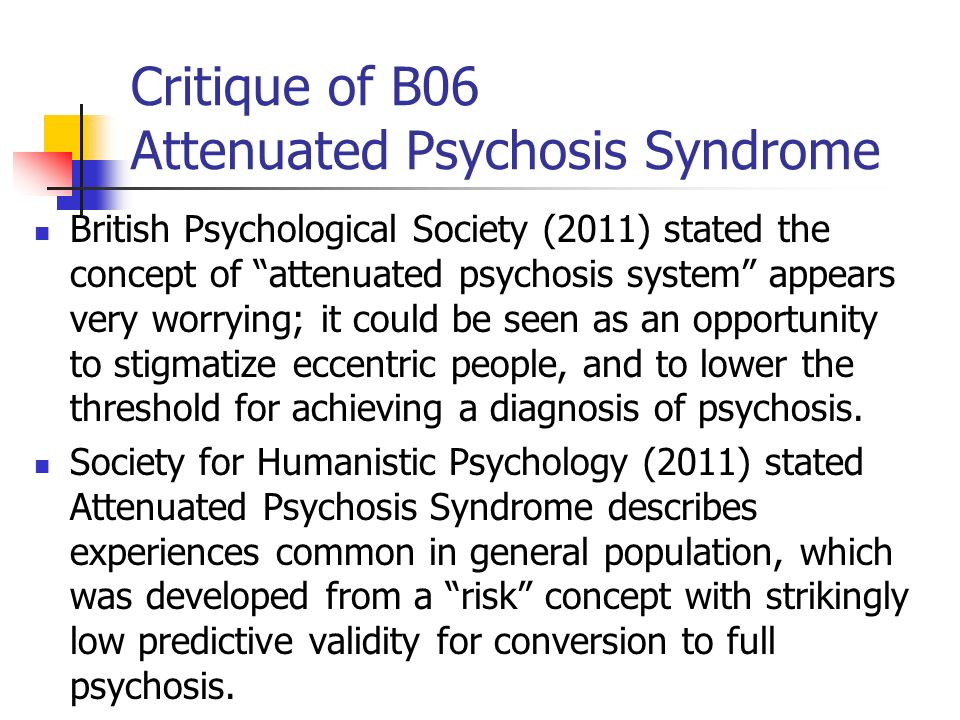

In a recent article, Margaret Spinelli, MD describes a proposal to the DSM-V committee of the American Psychiatric Association in 2020 arguing for the inclusion of postpartum psychosis as a unique diagnosis based on the cognitive disorganization that accompanies postpartum psychotic symptoms. The article clearly lays out the rationale for the inclusion of postpartum psychosis in the DSM, highlighting the distinctive features of postpartum psychosis and describing how the failure to appreciate these features may hinder the diagnosis and treatment of postpartum psychosis.

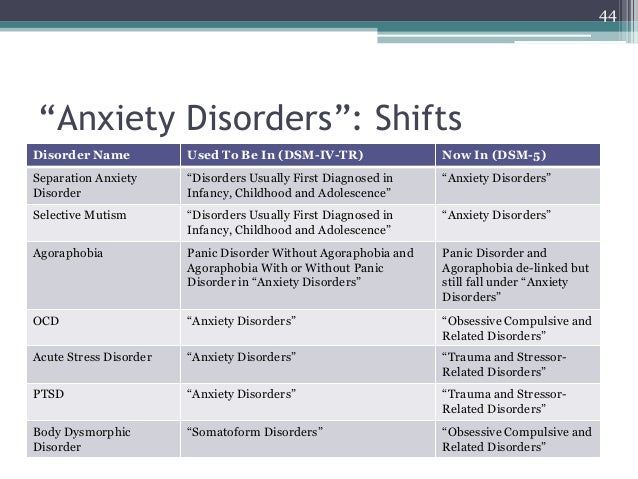

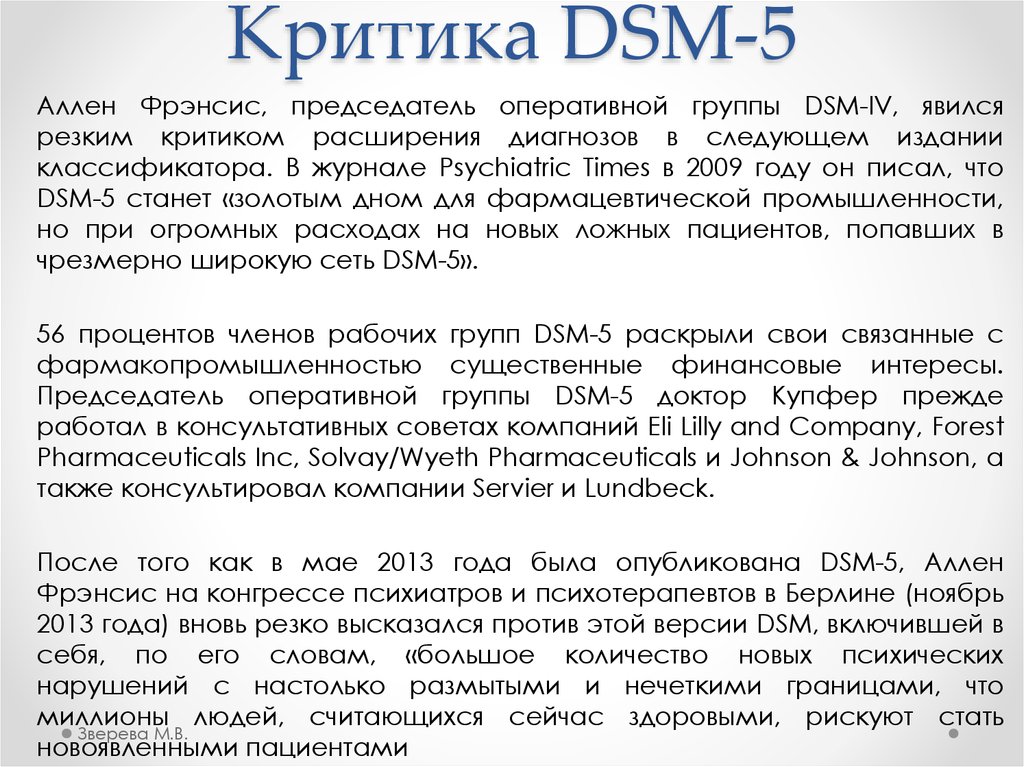

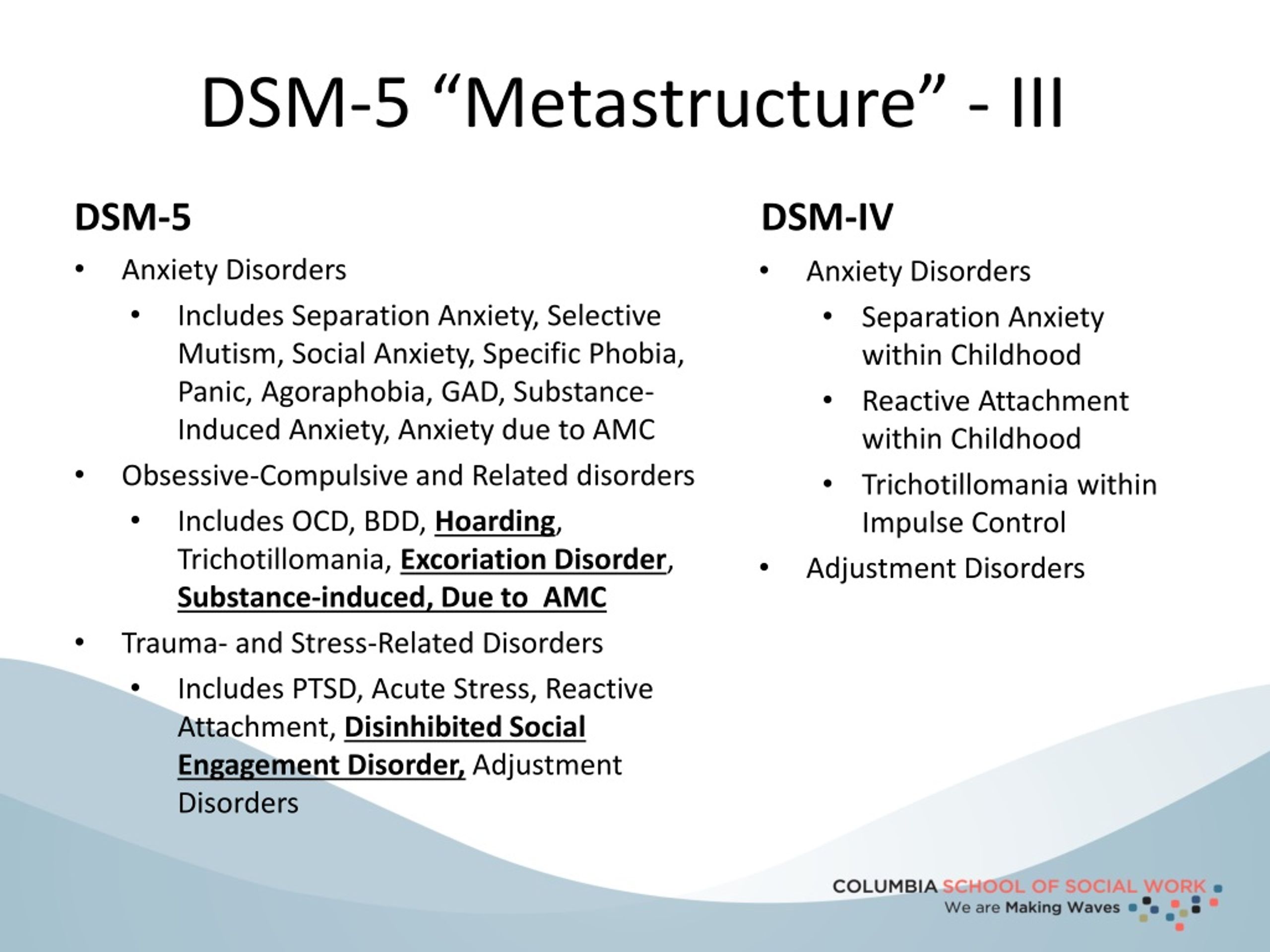

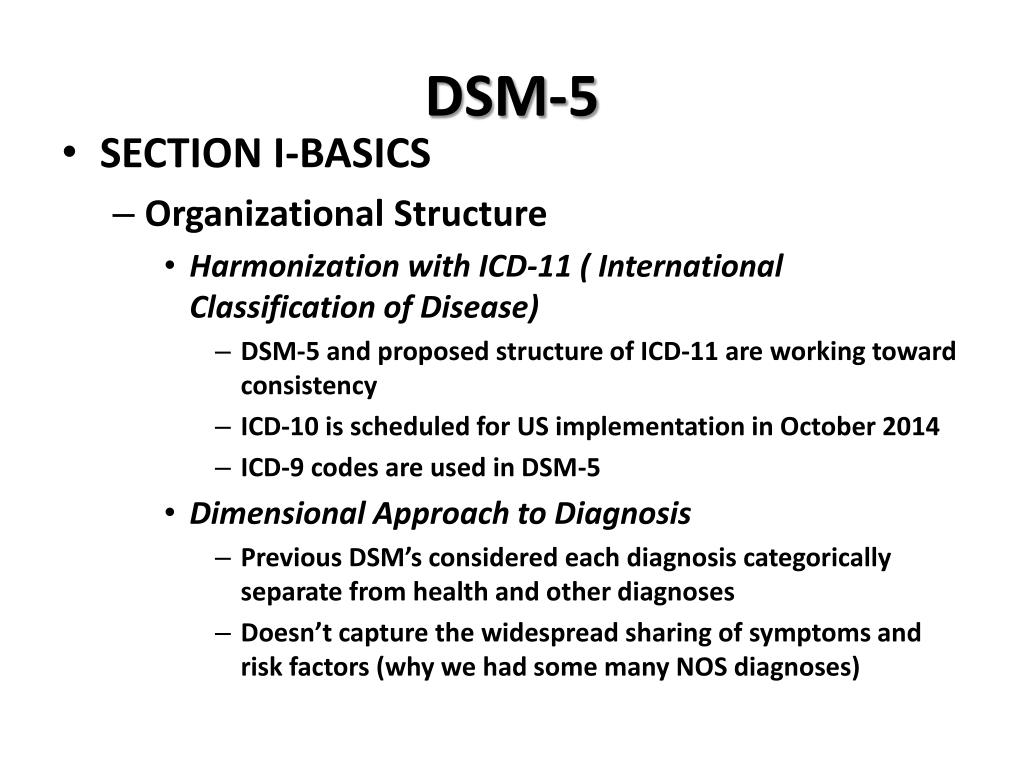

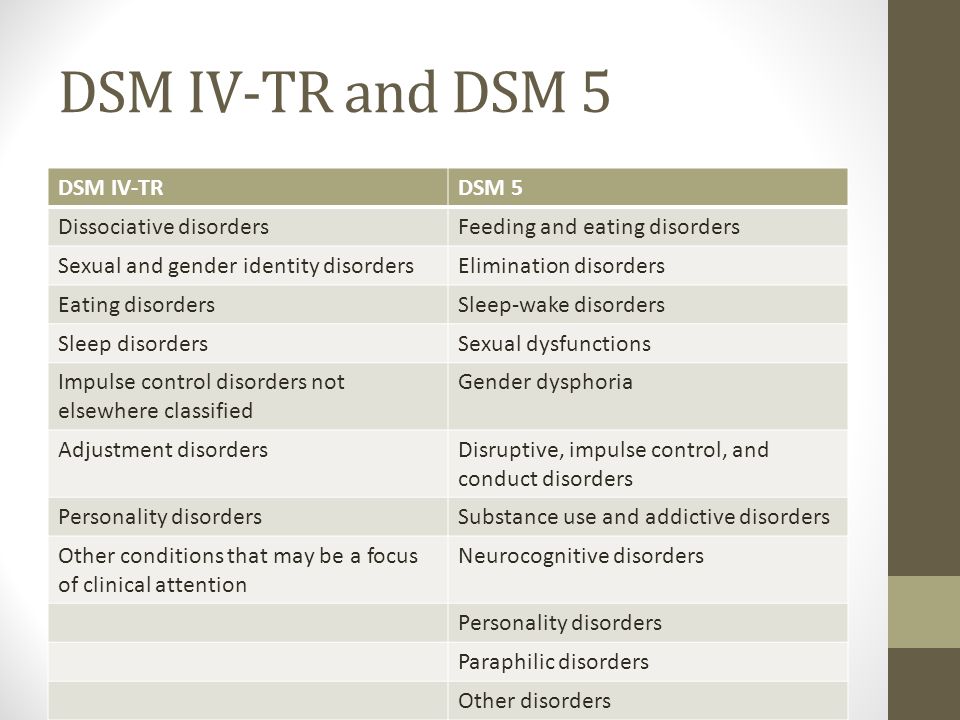

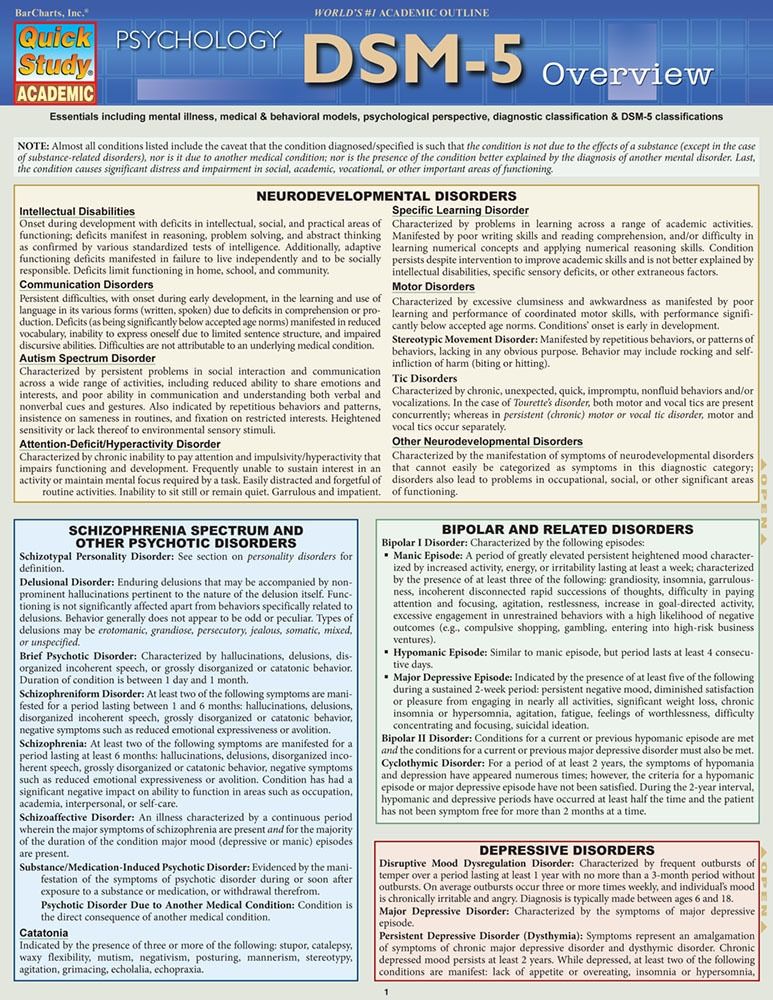

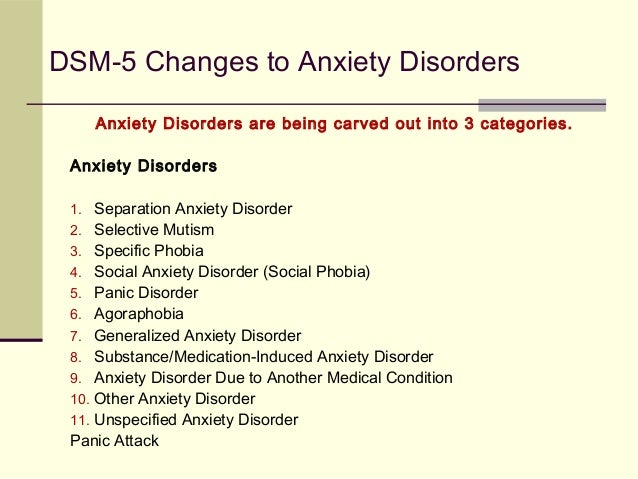

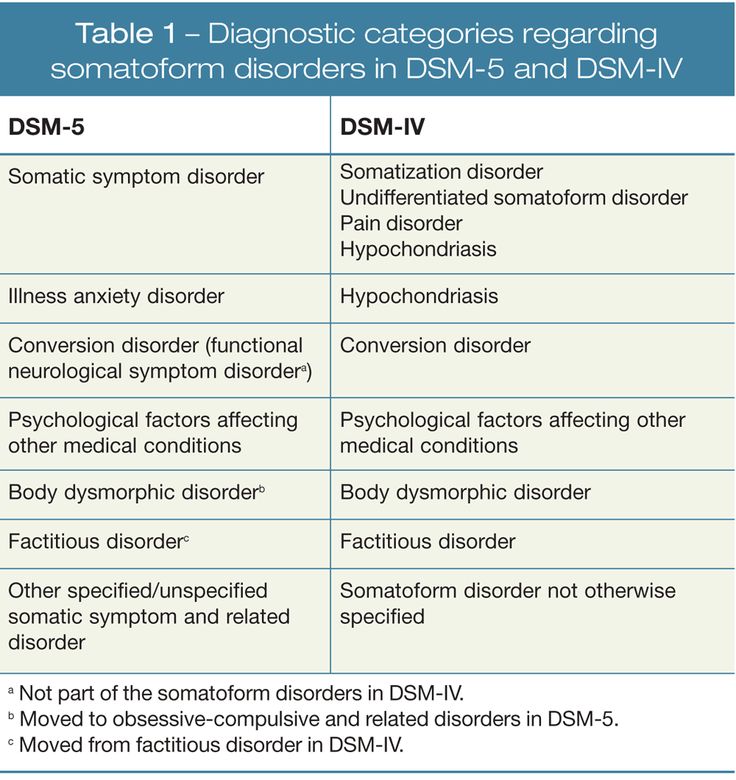

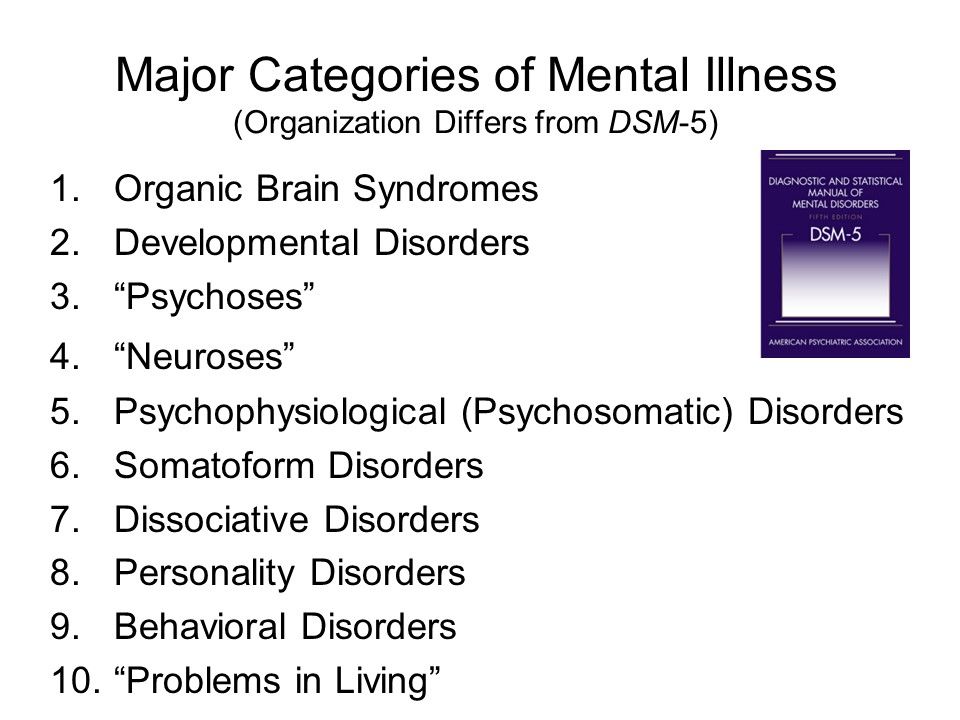

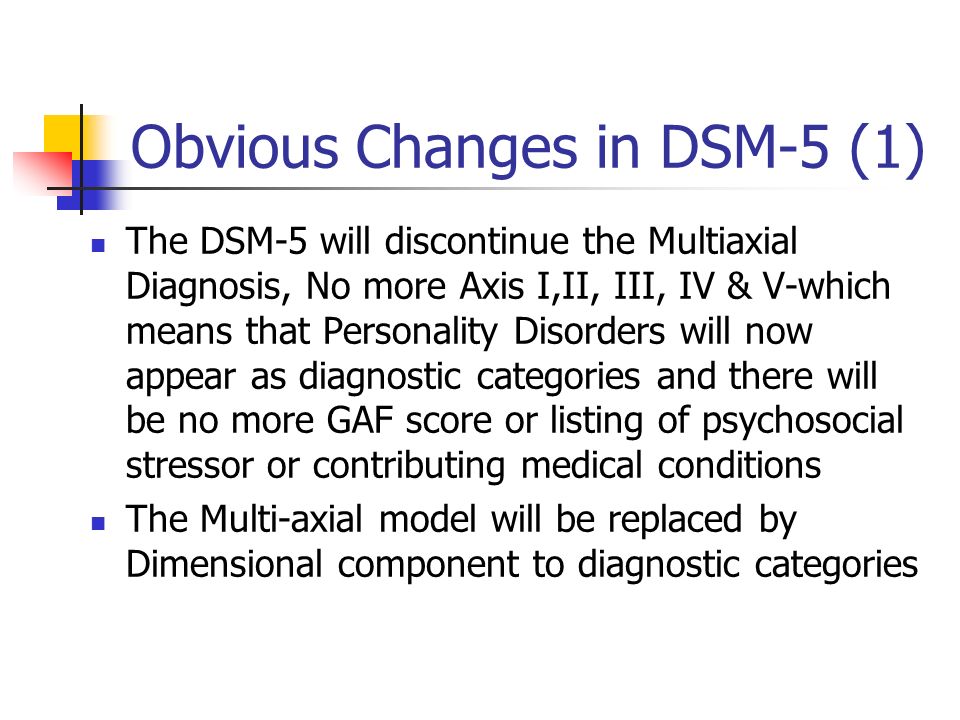

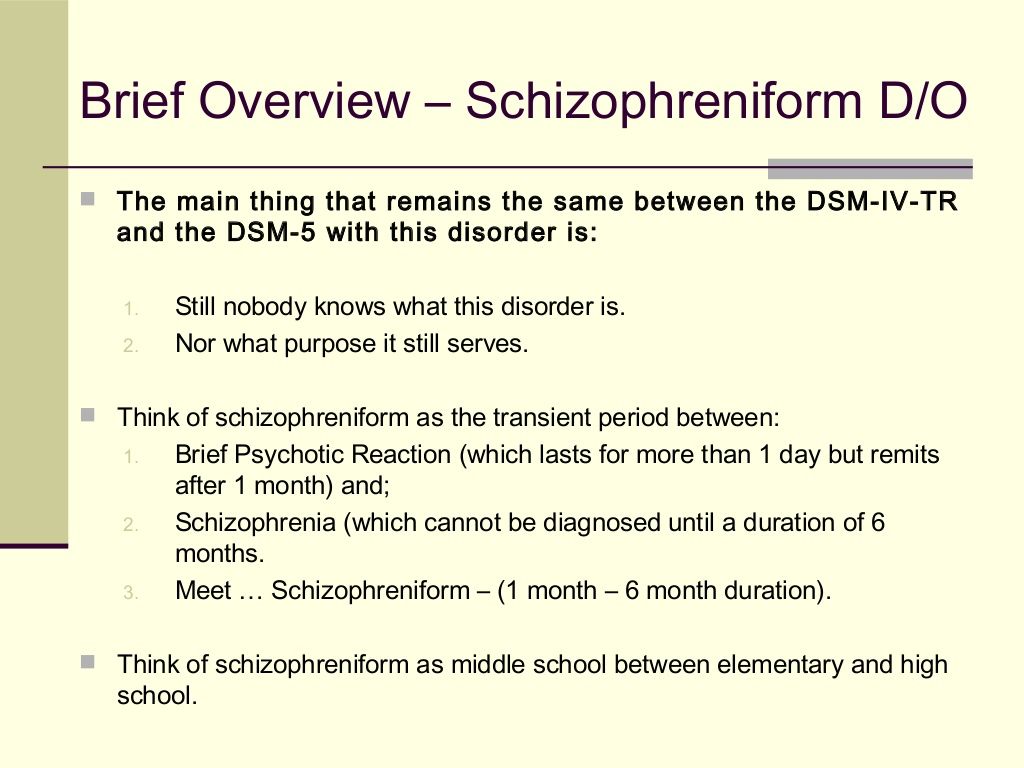

Spinelli starts by giving a historical perspective of the inclusion of postpartum psychiatric illness in the DSM. The first version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) was published in 1952 to aid clinicians in the recognition and consistent classification of specific psychiatric illnesses. In this first version, postpartum psychosis was included as

Involutional Psychotic Reaction. In the second version of the DSM (1968), postpartum psychosis was again included, this time as Psychosis with Childbirth. However, postpartum psychosis was dropped from the DSM in 1980. In fact, the word “postpartum” was expunged from the next two versions of the DSM. Despite an increased interest in and awareness of perinatal mood disorders in the following twenty years, postpartum psychiatric disorders, including postpartum psychosis, did not find their way back into the DSM until 1994.

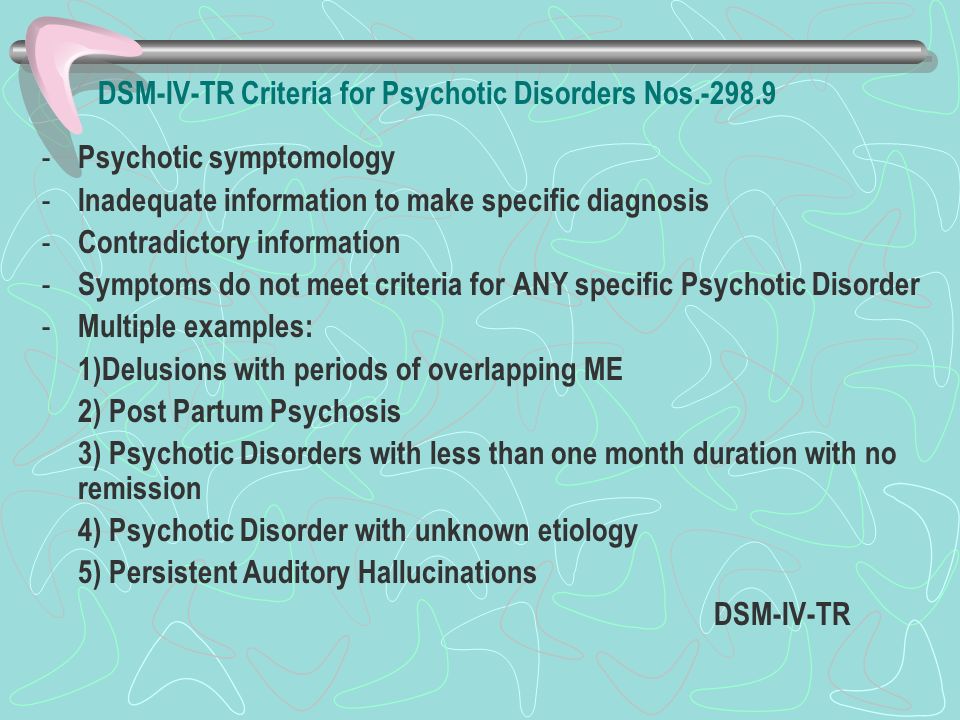

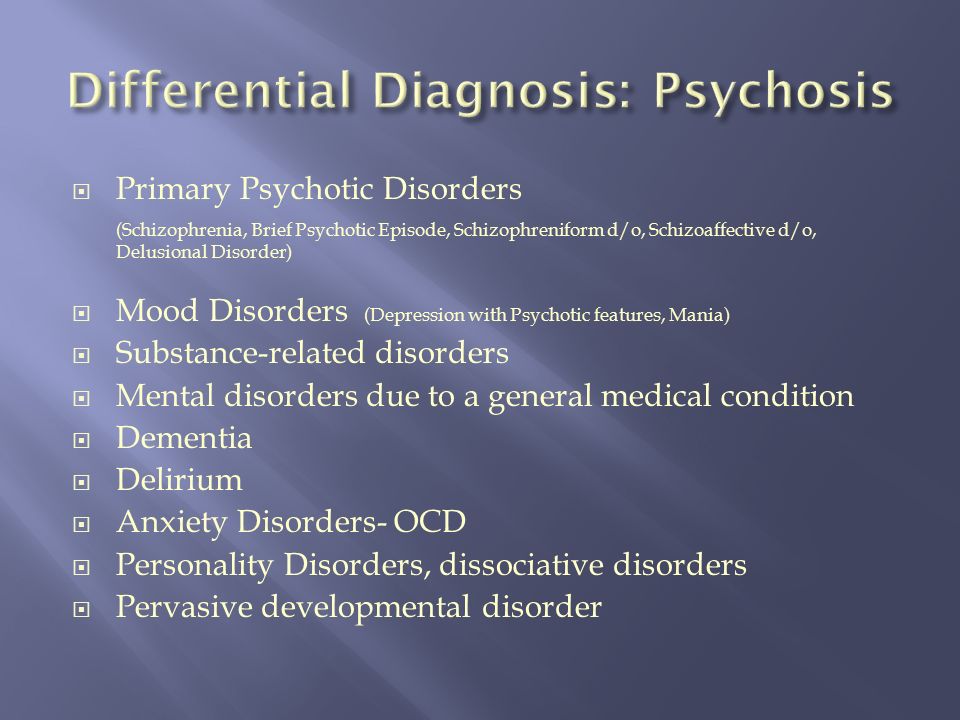

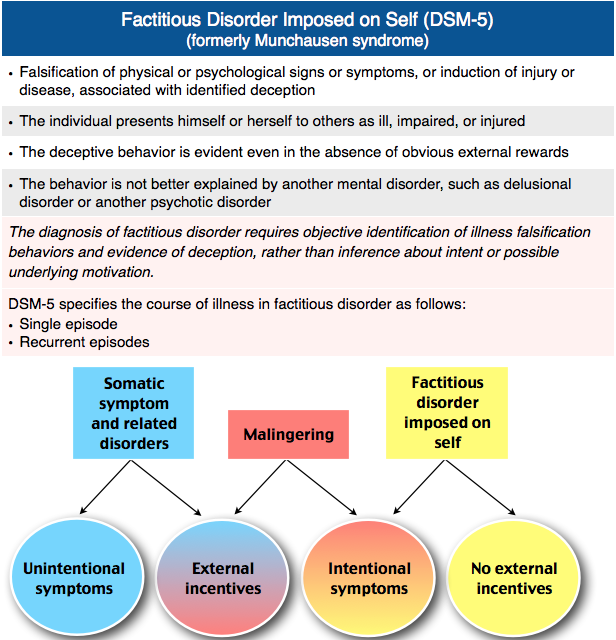

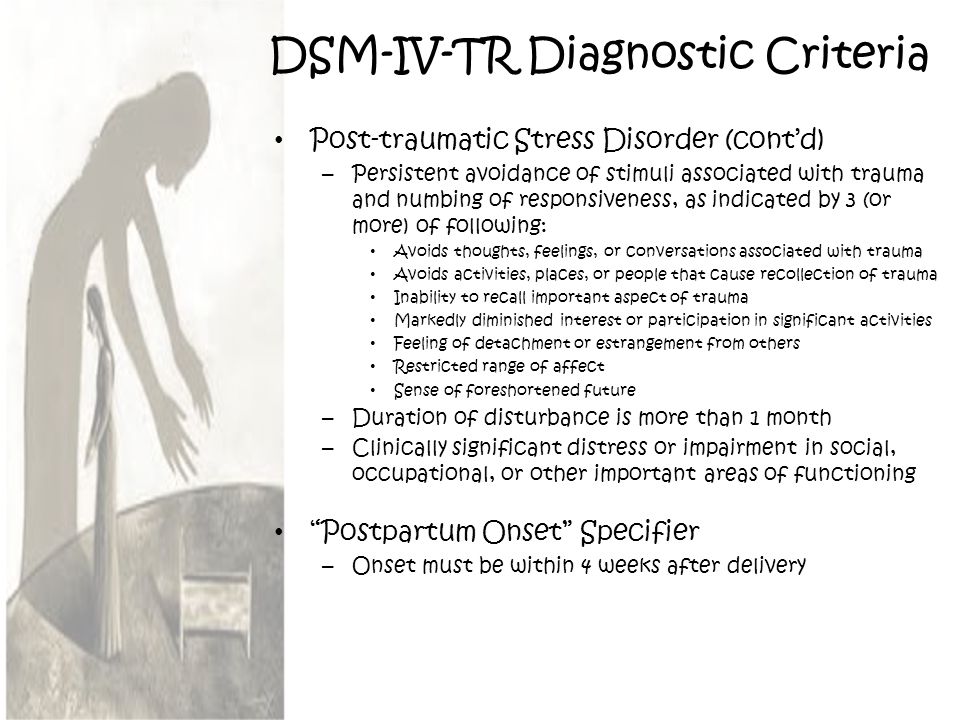

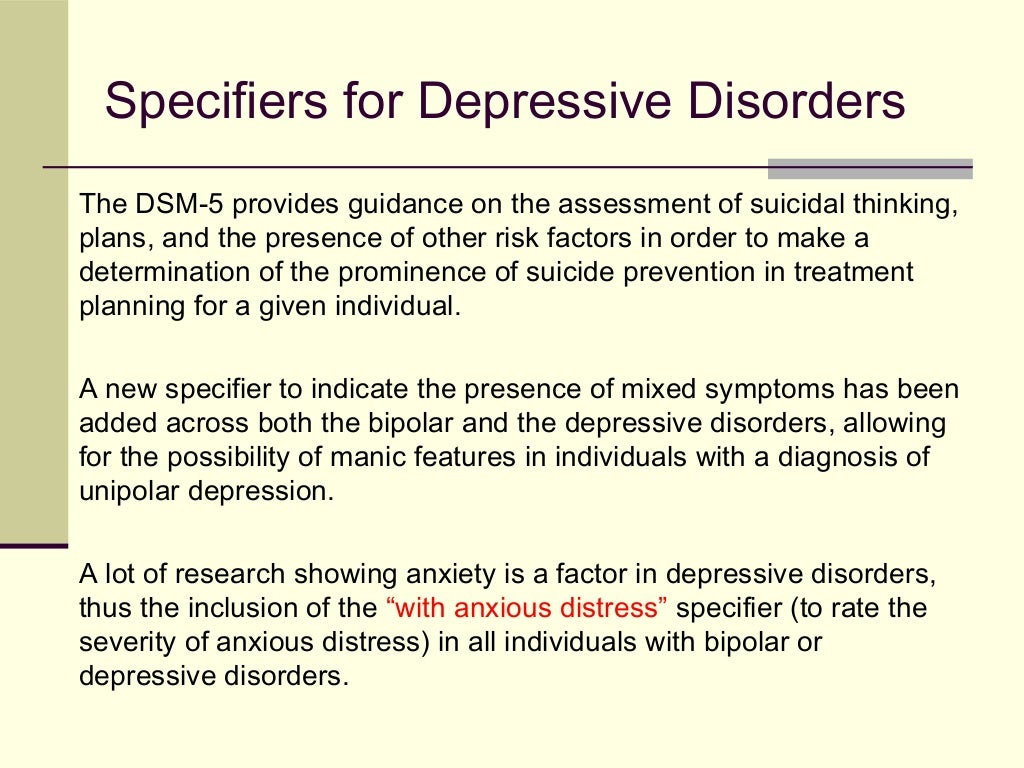

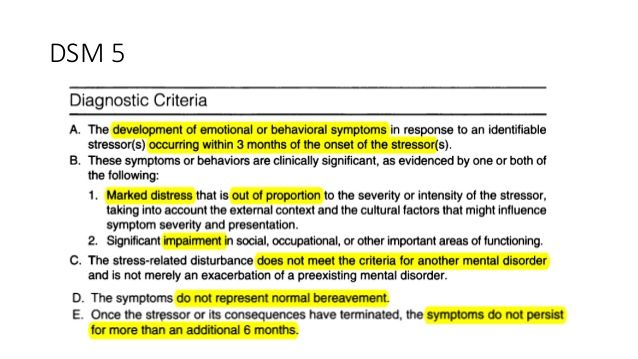

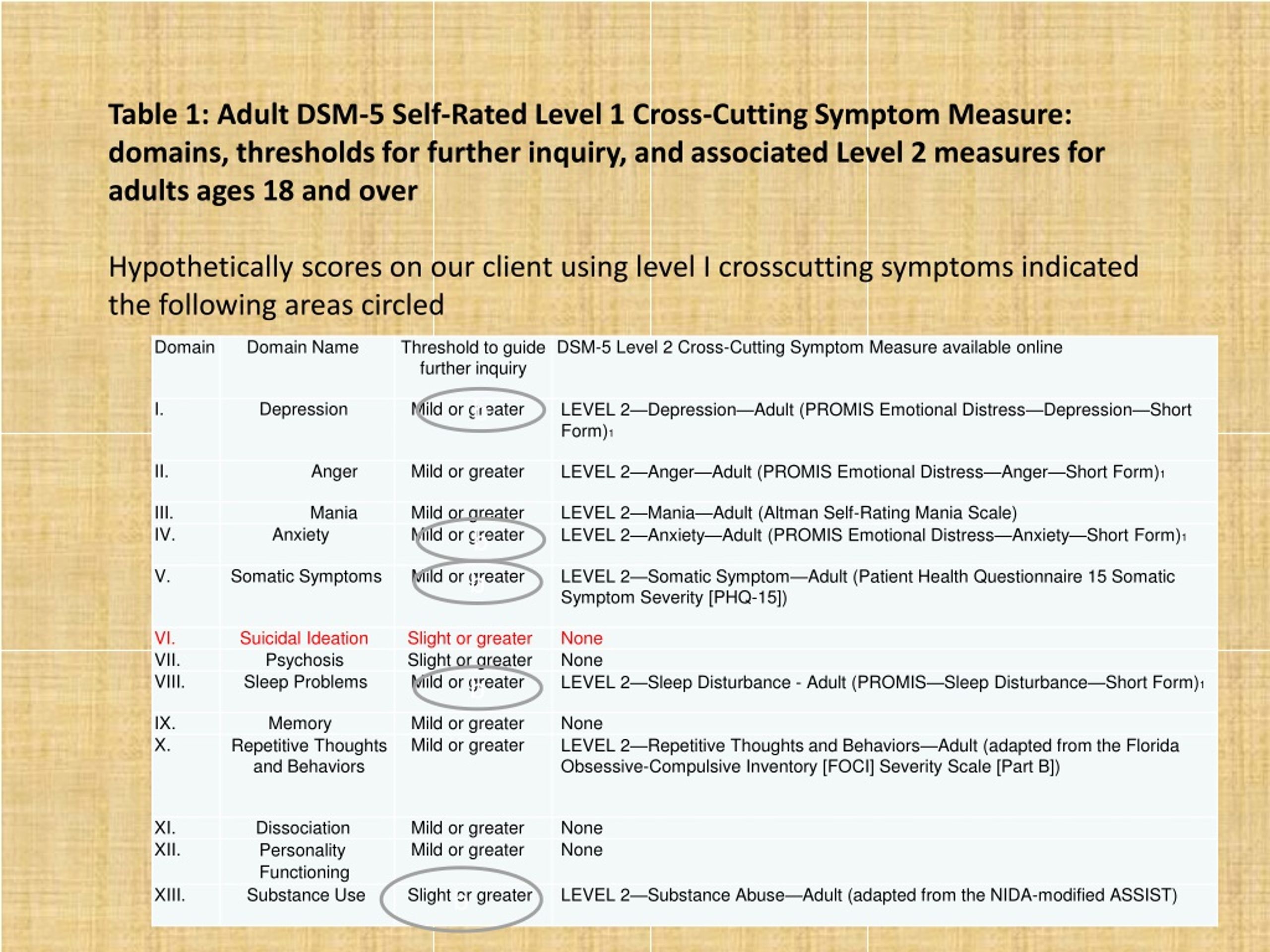

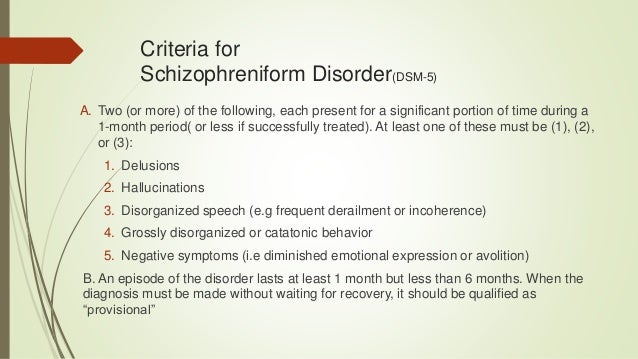

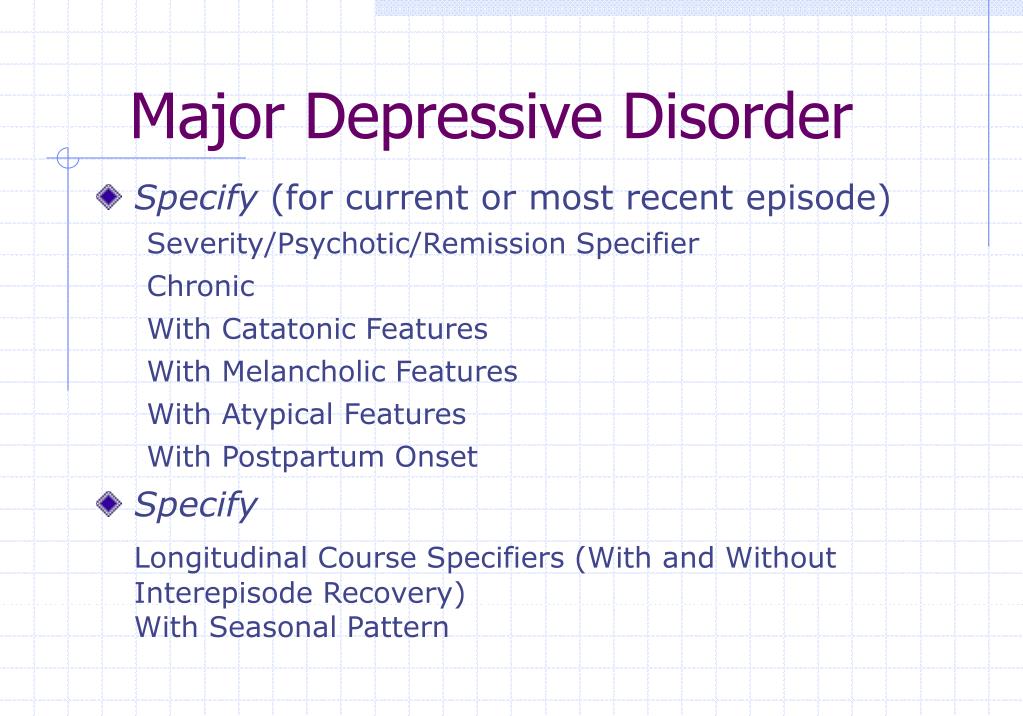

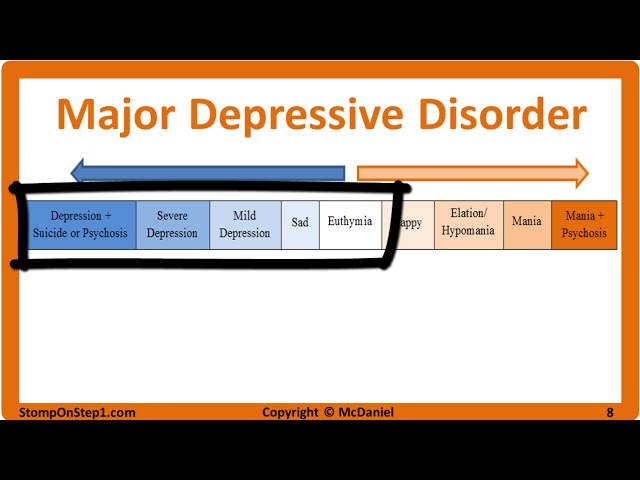

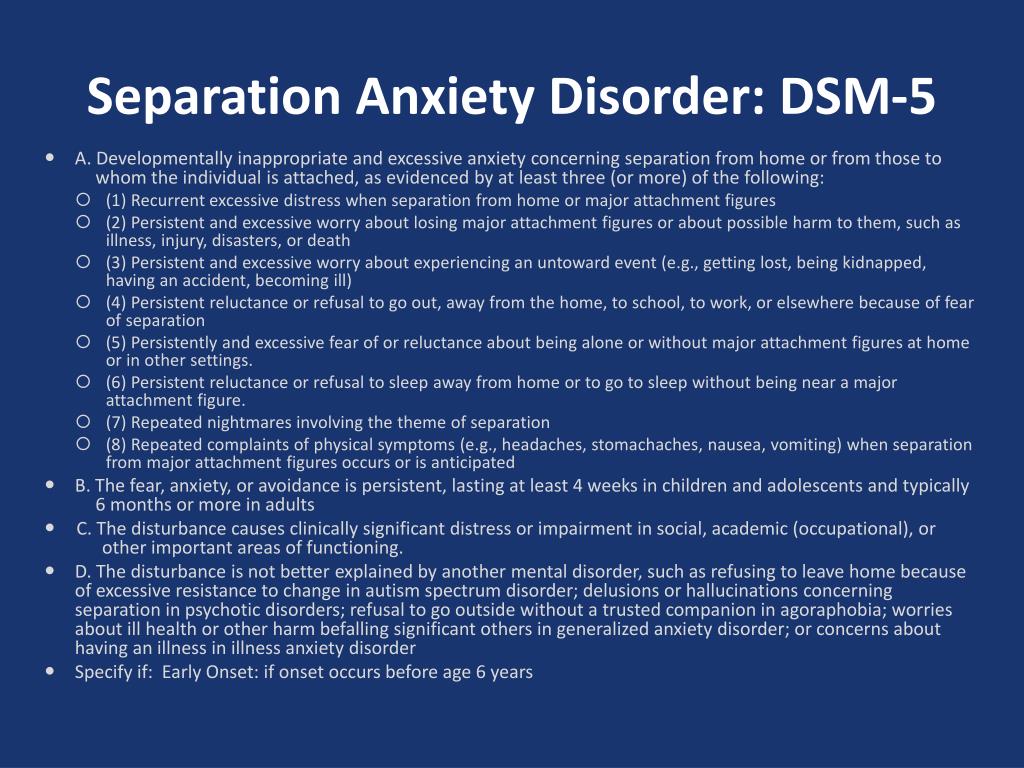

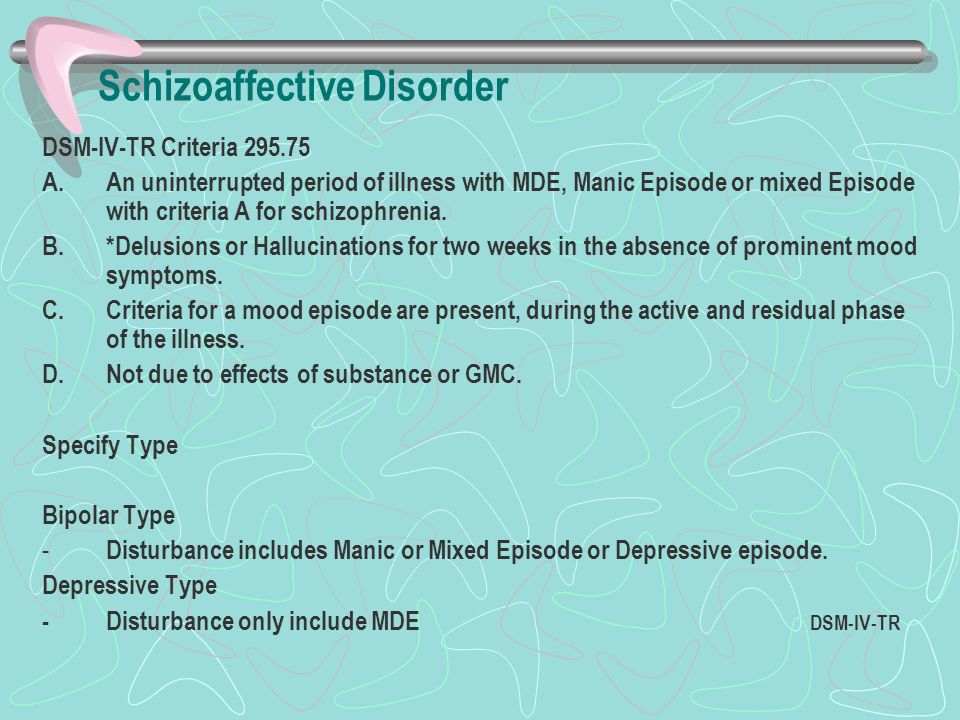

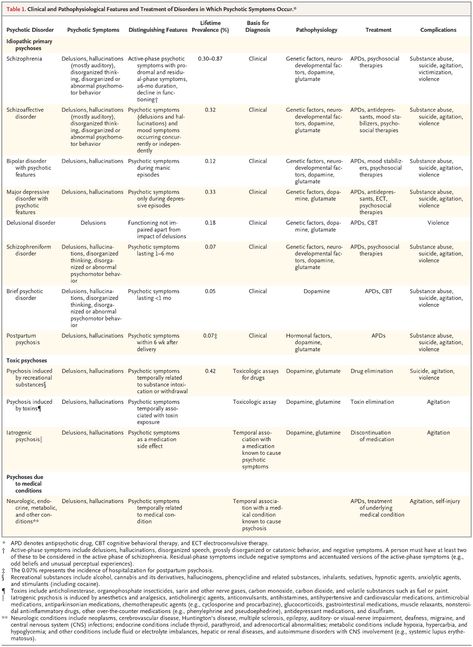

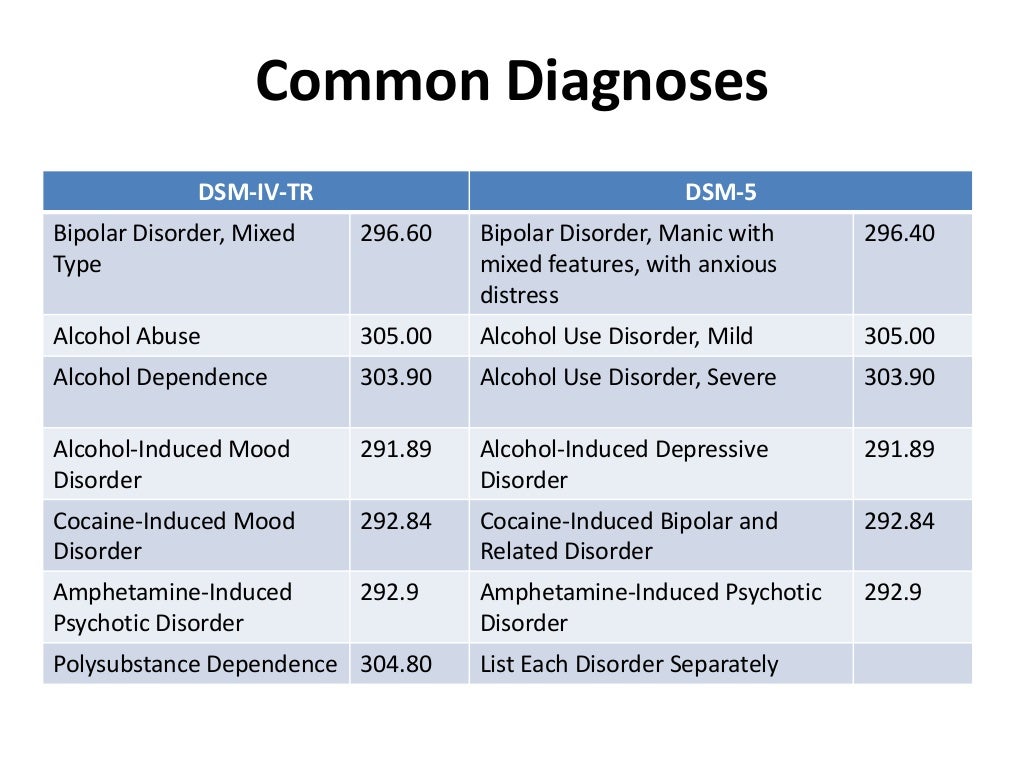

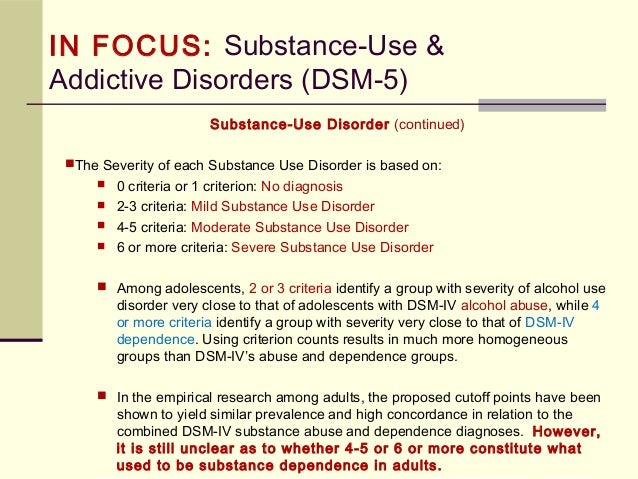

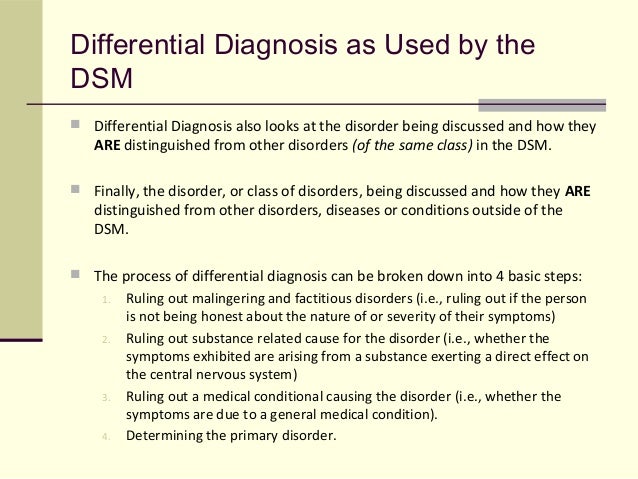

When the diagnosis of postpartum psychosis reappeared in the DSM IV-TR in 1994, it was incorporated using the specifier “with postpartum onset” which could be used to describe a brief psychotic disorder or a major depressive, manic, or mixed episode with psychotic features in an individual with either major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder, if the onset occurred within 4 weeks postpartum.

The postpartum onset specifier recognizes the temporal association of postpartum psychosis with childbirth; however, it fails to acknowledge how postpartum psychosis may differ from other types of psychotic experiences. While this may seem like a minor semantic issue, not recognizing the distinctive features of postpartum psychosis may hinder diagnosis and treatment.

While this may seem like a minor semantic issue, not recognizing the distinctive features of postpartum psychosis may hinder diagnosis and treatment.

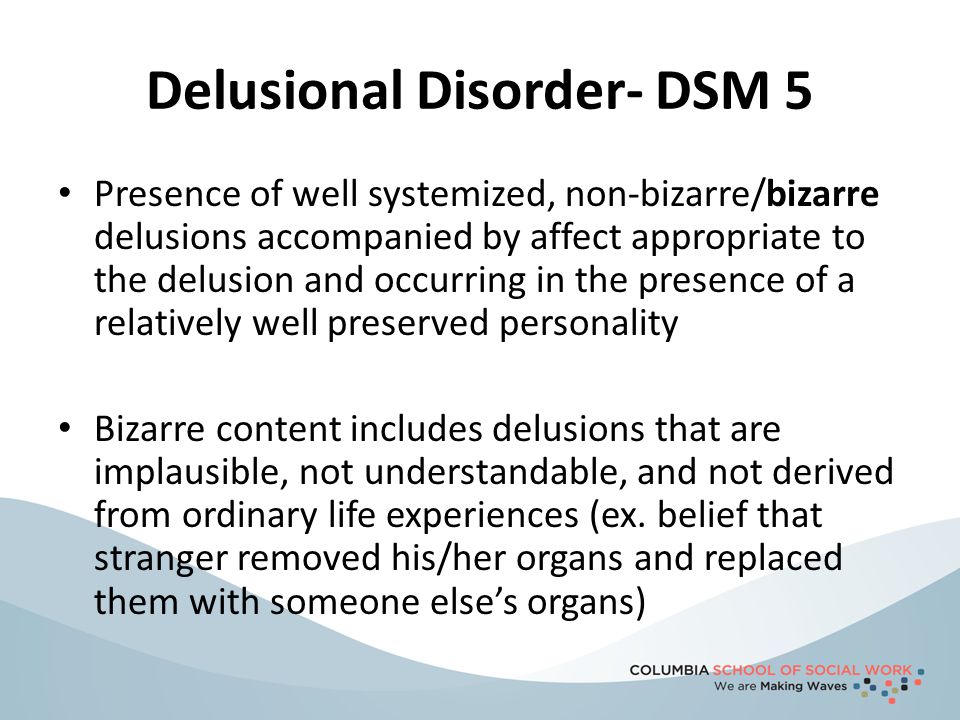

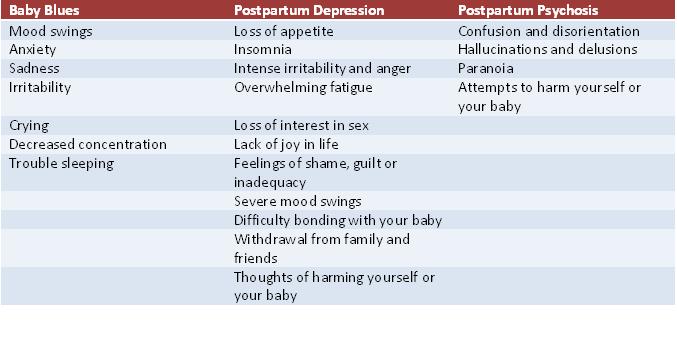

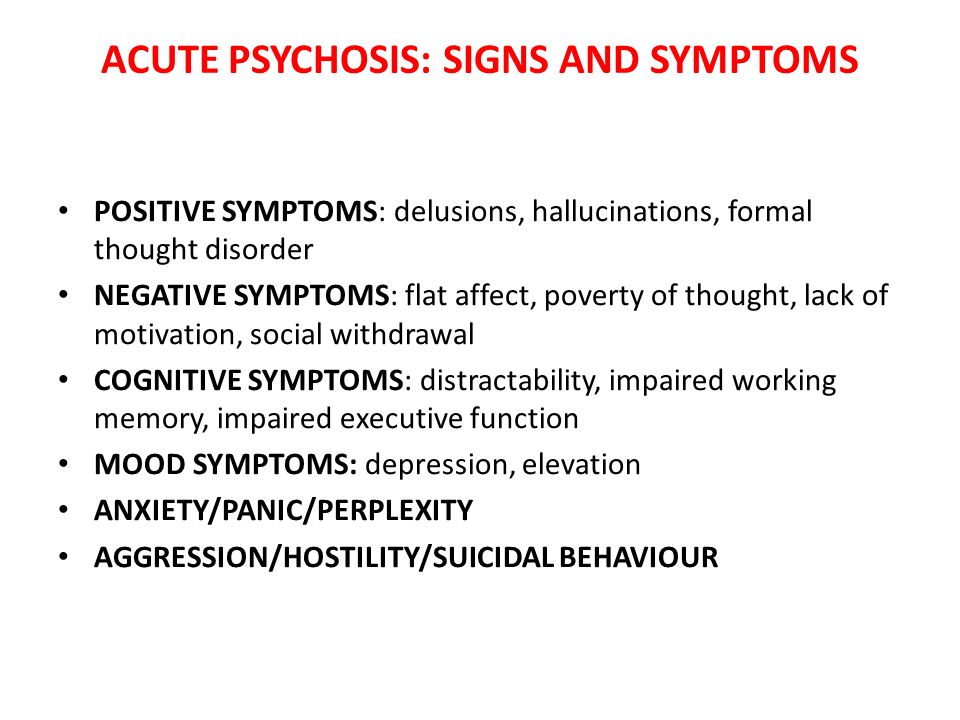

Spinelli notes that since the earliest reports of postpartum psychosis in the medical literature, clinicians, including Esquirol in 1838 and Victor Louis Marce in 1858, have noted the distinctive features of postpartum psychosis. Fairly consistently, postpartum psychosis has been described as a complex clinical picture encompassing a triad of psychiatric symptoms: mood symptoms, psychosis and cognitive disorganization, “ a delirium-like state of confusion and disorientation”.

Cognitive Disorganization or Delirium as a Unique Feature of Postpartum Psychosis

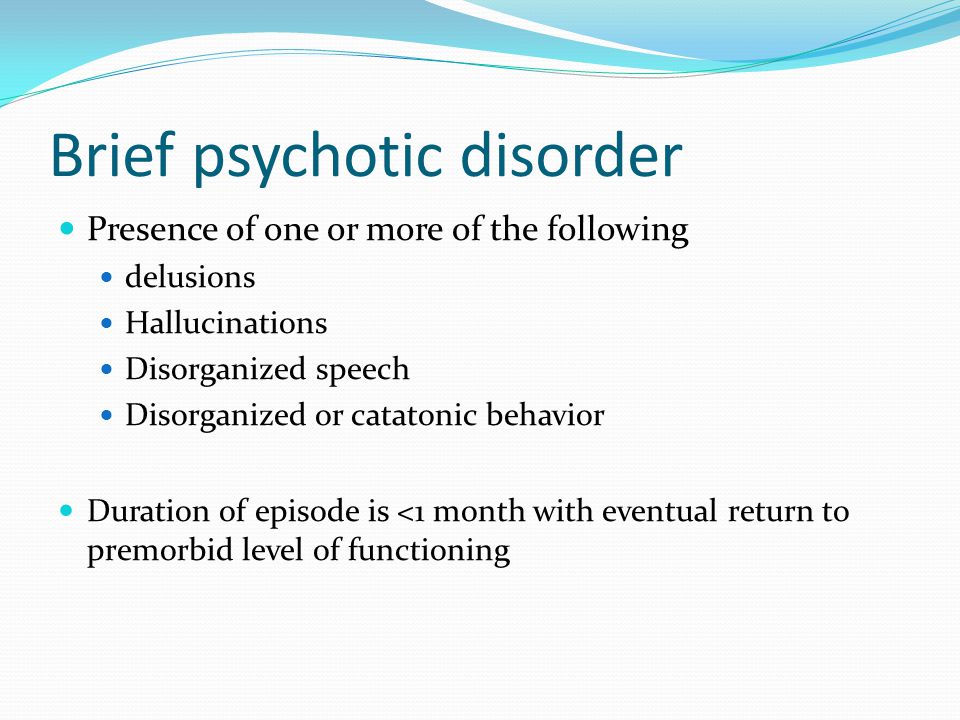

Since clinicians first began to describe postpartum psychosis, they have reported on the unusual cognitive disorganization and disorientation observed in this patient population. Clinicians have reported a spectrum of cognitive symptoms and distortions, including distractibility, difficulties with communication, memory problems, disorientation, confusion, depersonalization, and derealization. These symptoms are similar to those we see with delirium, and like delirium, the symptoms of postpartum psychosis emerge rapidly, within hours or days, and can have a waxing and waning quality.

These symptoms are similar to those we see with delirium, and like delirium, the symptoms of postpartum psychosis emerge rapidly, within hours or days, and can have a waxing and waning quality.

In a report published in 1994, Wisner and colleagues tried to better characterize the differences between postpartum and non-postpartum psychosis. This study prospectively compared women with postpartum psychosis (n?=?21) to those with psychosis unrelated to childbirth (n?=?96) using formal cognitive testing. Women with postpartum psychosis reported higher scores on measures of cognitive disorganization psychosis or delirium. In addition, women with postpartum psychosis were more likely to report homicidal ideation, lack of insight, functional impairment and atypical visual, tactile and olfactory hallucinations. These findings also suggest that postpartum psychosis has many delirium-like features: cognitive disorganization, functional impairment, lack of insight, and unusual perceptual disturbances.

Delirium is a clinical syndrome, characterized by an acute and fluctuating alteration in awareness and cognition resulting from pathophysiological changes. Delirium can have many different causes: severe medical illness, medication toxicity, drug intoxication or withdrawal, fever, infection, metabolic imbalances, sleep deprivation, As a result the clinical presentation is varied and is influenced by the clinical context in which delirium occurs.

While the symptoms of postpartum psychosis — its rapid onset, the waxing and waning quality, and the unusual quality of perceptual disturbances — overlap with delirium, we do not typically consider the physiologic changes that may trigger postpartum psychosis. Spinelli notes that this “disregards the neurohormonal triggering factors of childbirth and the impact of the massive hormone withdrawal at the time of childbirth that generates modifications and dysregulation of brain chemicals.”

Spinelli argues that this cognitive disorganization not only distinguishes postpartum psychosis from other types of psychosis, but it is also the feature that makes postpartum psychosis so dangerous:

The cognitive or delirium-like state must be anticipated because of the waxing and waning, confusion, and disorientation that contributes to the mother’s poor judgment and impulsivity.

“Waxing and waning,” such that the woman seems well at one moment then floridly psychotic in the next, may not be anticipated. Mother must be supervised and separated from the infant. Importantly, clinicians untrained in perinatal psychiatry have often missed the subtle symptoms. Many infants have been killed during this period of “pseudo-wellness.”

Why Postpartum Psychosis Should Be Included in the DSM-V

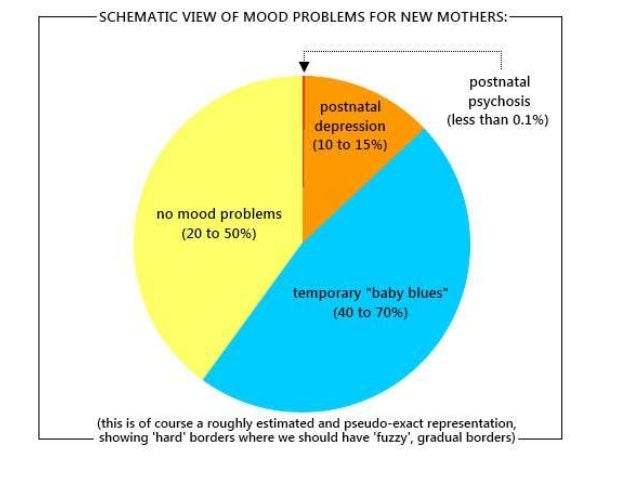

While postpartum psychosis is rare, affecting only one out of every 1000 women after childbirth, it causes significant morbidity and mortality in this population. Women with postpartum psychosis are at significant risk for suicide. In addition, postpartum psychosis puts the infant at risk, with estimates of infanticide ranging form 1 to 4.5%.

The current use of the postpartum onset specifier to classify women with postpartum psychosis is clearly insufficient:

- It fails to include important clinical information, more specifically the cognitive disorganization and delirium-like features which occur more commonly in postpartum psychosis than in non-puerperal psychosis.

- It does not include information on medical conditions specific to the postpartum period which may cause a similar clinical picture, including autoimmune thyroiditis and NMDR encephalitis.

- It fails to communicate important clinical information regarding the need for ensuring the safety of the mother and the infant, given the heightened risk for suicide and infanticide.

- It does not highlight the strong link between postpartum psychosis and bipolar disorder, and thus does not provide important clinical information on risk for non-puerperal recurrence and possible long-term treatment strategies.

- It does not include information to guide the choice of effective treatments. Specifically many women with postpartum psychosis require treatment with antipsychotic medications and a mood stabilizer.

- It does not include information which would ultimately improve clinical outcomes.

Acknowledging the recurrent nature of postpartum psychosis would allow for prophylactic interventions in subsequent pregnancies.

Acknowledging the recurrent nature of postpartum psychosis would allow for prophylactic interventions in subsequent pregnancies.

While the DSM committee reviewing this information did not ultimately approve the inclusion of postpartum psychosis as a distinct diagnosis, the committee did acknowledge that the current “with postpartum onset specifier” is insufficient for women with postpartum psychosis. They proposed that postpartum psychosis should be included in Section 3 of the DSM: “Conditions for Further Study”. The hope is that this would encourage further research. (Premenstrual dysphoric disorder or PMDD was placed in that section in the DSM-IV and ultimately made it into the DSM-V as a distinct diagnosis.)

Given the rarity and rapidly evolving nature of postpartum psychosis, it is extremely difficult to study. It is nearly impossible to collect prospective data using standardized instruments. We are now in the midst of what we call our MGHP3 Study, the MGH Postpartum Psychosis Project. We are collecting clinical and demographic information, as well as genetic samples, from women who have experienced postpartum psychosis, in an effort to better understand the etiology of illness.

We are collecting clinical and demographic information, as well as genetic samples, from women who have experienced postpartum psychosis, in an effort to better understand the etiology of illness.

Ruta Nonacs, MD PhD

Spinelli M. Postpartum psychosis: a diagnosis for the DSMV. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2021 Sep 8.

Related Posts

Postpartum psychiatric disorders: Early diagnosis and management

1. Marcus SM, Flynn HA, Blow FC, Barry KL. Depressive symptoms among pregnant women screened in obstetrics settings. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2003;12:373–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Carter AS, Garrity-Rokous FE, Chazan-Cohen R, Little C, Briggs-Gowan MJ. Maternal depression and comorbidity: Predicting early parenting, attachment security, and toddler social-emotional problems and competencies. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:18–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Platz C, Kendell RE. A matched-control follow-up and family study of ‘puerperal psychoses’ Br J Psychiatry. 1988;153:90–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

1988;153:90–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Robling SA, Paykel ES, Dunn VJ, Abbott R, Katona C. Long-term outcome of severe puerperal psychiatric illness: A 23 year follow-up study. Psychol Med. 2000;30:1263–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Pfuhlmann B, Stöber G, Franzek E, Beckmann H. Cycloid psychoses predominate in severe postpartum psychiatric disorders. J Affect Disord. 1998;50:125–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Text Revision. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

7. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; pp. 186–7. [Google Scholar]

8. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992. World Health Organization. ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders. [Google Scholar]

9. Born L, Zinga D, Steiner M. Challenges in identifying and diagnosing postpartum disorders. Prim Psychiatry. 2004;11:29–36. [Google Scholar]

Challenges in identifying and diagnosing postpartum disorders. Prim Psychiatry. 2004;11:29–36. [Google Scholar]

10. Kumar R. Postnatal mental illness: A transcultural perspective. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1994;29:250–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Okano T, Nomura J, Kumar R, Kaneko E, Tamaki R, Hanafusa I, et al. An epidemiological and clinical investigation of postpartum psychiatric illness in Japanese mothers. J Affect Disord. 1998;48:233–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Dean C, Kendell RE. The symptomatology of puerperal illnesses. Br J Psychiatry. 1981;139:128–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Klompenhouwer JL, van Hulst AM. Classification of postpartum psychosis: A study of 250 mother and baby admissions in The Netherlands. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991;84:255–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Kumar R, Marks M, Platz C, Yoshida K. Clinical survey of a psychiatric mother and baby unit: Characteristics of 100 consecutive admissions. J Affect Disord. 1995;33:11–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

1995;33:11–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Brockington IF, Cernik KF, Schofield EM, Downing AR, Francis AF, Keelan C. Puerperal psychosis. Phenomena and diagnosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:829–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. O’Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risks of post-partum depression – A meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1996;8:37. [Google Scholar]

17. O’Hara MW, Schlechte JA, Lewis DA, Varner MW. Controlled prospective study of postpartum mood disorders: Psychological, environmental, and hormonal variables. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100:63–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Chandran M, Tharyan P, Muliyil J, Abraham S. Post-partum depression in a cohort of women from a rural area of Tamil Nadu, India. Incidence and risk factors. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:499–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Troutman BR, Cutrona CE. Nonpsychotic postpartum depression among adolescent mothers. J Abnorm Psychol. 1990;99:69–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Gautam S, Nijhawan M, Gehlot PS. Post partum psychiatric syndromes-an analysis of 100 consecutive cases. Indian J Psychiatry. 1982;24:383–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Post partum psychiatric syndromes-an analysis of 100 consecutive cases. Indian J Psychiatry. 1982;24:383–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Nott PN, Franklin M, Armitage C, Gelder MG. Hormonal changes and mood in the puerperium. Br J Psychiatry. 1976;128:379–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Steiner M. Psychobiology of mental disorders associated with childbearing. An overview. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1979;60:449–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Handley SL, Dunn TL, Waldron G, Baker JM. Tryptophan, cortisol and puerperal mood. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;136:498–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Shah LP, Parkar S, Pandit AS. 1999. Textbook of Postgraduate Psychiatry; pp. 369–75. [Google Scholar]

25. Paykel ES, Emms EM, Fletcher J, Rassaby ES. Life events and social support in puerperal depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;136:339–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Causey S, Fairman M, Nicholson D, Steiner M. Can postpartum depression be prevented? Arch Women Ment Health. 2001;3(Suppl 1):S24. [Google Scholar]

2001;3(Suppl 1):S24. [Google Scholar]

27. Sharma V, Mazmanian D. Sleep loss and postpartum psychosis. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5:98–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. O’Hara MW, Schlechte JA, Lewis DA, Wright EJ. Prospective study of postpartum blues. Biologic and psychosocial factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:801–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Stein G. The maternity blues. In: Brockington IF, Kumar R, editors. Motherhood and Mental Illness. London, UK: Academic Press; 1982. pp. 119–54. [Google Scholar]

30. Kendell RE, McGuire RJ, Connor Y, Cox JL. Mood changes in the first three weeks after childbirth. J Affect Disord. 1981;3:317–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Henshaw C. Mood disturbance in the early puerperium: A review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2003;6(Suppl 2):S33–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Altshuler LL, Cohen L, Szuba MP, Burt VK, Gitlin M, Mintz J. Pharmacologic management of psychiatric illness during pregnancy: Dilemmas and guidelines. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:592–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:592–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Kendell RE, Chalmers JC, Platz C. Epidemiology of puerperal psychoses. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:662–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. McNeil TF. A prospective study of postpartum psychoses in a high-risk group 2. Relationships to demographic and psychiatric history characteristics. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1987;75:35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Nonacs R, Cohen LS. Postpartum mood disorders: Diagnosis and treatment guidelines. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 2):34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Spinelli MG. Postpartum psychosis: Detection of risk and management. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:405–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Wisner KL, Peindl K, Hanusa BH. Symptomatology of affective and psychotic illnesses related to childbearing. J Affect Disord. 1994;30:77–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Friedman SH, Cavney J, Resnick PJ. Child murder by parents and evolutionary psychology. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35:781–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2012;35:781–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Bydlowski M, Raoul-Duval A. A psychological manifestation unknown within paediatrics: The posttraumatic obstetric neurosis. Perspect Psychiatr. 1978;4:321–8. [Google Scholar]

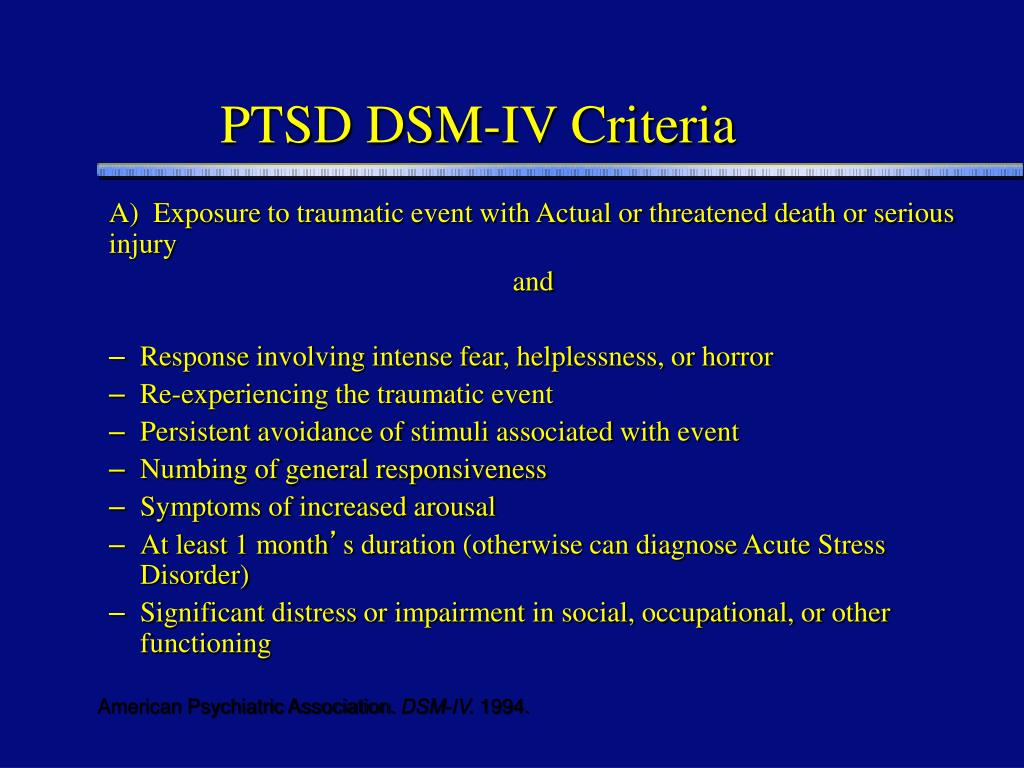

40. Creedy DK, Shochet IM, Horsfall J. Childbirth and the development of acute trauma symptoms: Incidence and contributing factors. Birth. 2000;27:104–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Menage J. Post-traumatic stress disorder in women who have undergone obstetric and/or gynaecological procedures. A consecutive series of 30 cases of PTSD. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 1993;11:221–8. [Google Scholar]

42. Matthey S, Barnett B, Howie P, Kavanagh DJ. Diagnosing postpartum depression in mothers and fathers: Whatever happened to anxiety? J Affect Disord. 2003;74:139–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. De Armond M. A type of post partum anxiety reaction. Dis Nerv Syst. 1954;15:26–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Sved-Williams AE. Phobic reactions of mothers to their own babies. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1992;26:631–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1992;26:631–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Weightman H, Dalal BM, Brockington IF. Pathological fear of cot death. Psychopathology. 1998;31:246–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Neziroglu F, Anemone R, Yaryura-Tobias JA. Onset of obsessive-compulsive disorder in pregnancy. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:947–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Abramowitz JS, Schwartz SA, Moore KM, Luenzmann KR. Obsessive-compulsive symptoms in pregnancy and the puerperium: A review of the literature. J Anxiety Disord. 2003;17:461–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Brockington I. Postpartum psychiatric disorders. Lancet. 2004;363:303–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Morris-Rush JK, Freda MC, Bernstein PS. Screening for postpartum depression in an inner-city population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1217–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Dennis CL. Can we identify mothers at risk for postpartum depression in the immediate postpartum period using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale? J Affect Disord. 2004;78:163–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2004;78:163–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Hirschfeld RM, Holzer C, Calabrese JR, Weissman M, Reed M, Davies M, et al. Validity of the mood disorder questionnaire: A general population study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:178–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Stamp GE, Williams AS, Crowther CA. Predicting postnatal depression among pregnant women. Birth. 1996;23:218–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Georgiopoulos AM, Bryan TL, Wollan P, Yawn BP. Routine screening for postpartum depression. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:117–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Weissman MM. The hidden patient: Unrecognized panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51(Suppl):5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Dell DL, Halford JJ. Dementia presenting as postpartum depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(5 Pt 2):925–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Stavrou P, Sgouros S. Frontal lobe tuberculoma masquerading as postnatal depression. Br J Neurosurg. 2002;16:74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Gautam P, Bhatia MS, Rathi A, Kaur J. Sheehan's syndrome with psychosis: A rare case presentation. Delhi J Psychiatry. 2014;17:211–3. [Google Scholar]

Gautam P, Bhatia MS, Rathi A, Kaur J. Sheehan's syndrome with psychosis: A rare case presentation. Delhi J Psychiatry. 2014;17:211–3. [Google Scholar]

58. Jaigobin C, Silver FL. Stroke and pregnancy. Stroke. 2000;31:2948–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Lanska DJ, Kryscio RJ. Risk factors for peripartum and postpartum stroke and intracranial venous thrombosis. Stroke. 2000;31:1274–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Thase ME, Mallinger AG, Swartz HA, Fagiolini AM, et al. Two-year outcomes for interpersonal and social rhythm therapy in individuals with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:996–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. O’Hara MW. Social support, life events, and depression during pregnancy and the puerperium. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:569–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Sit DK, Perel JM, Helsel JC, Wisner KL. Changes in antidepressant metabolism and dosing across pregnancy and early postpartum. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:652–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2008;69:652–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Turner KM, Sharp D, Folkes L, Chew-Graham C. Women's views and experiences of antidepressants as a treatment for postnatal depression: A qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2008;25:450–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Pearlstein TB, Zlotnick C, Battle CL, Stuart S, O’Hara MW, Price AB, et al. Patient choice of treatment for postpartum depression: A pilot study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9:303–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Bledsoe SE, Grote NK. Treating depression during pregnancy and in the postpartum: A preliminary meta-analysis. Res Soc Work Pract. 2006;16:109–20. [Google Scholar]

66. Appleby L, Warner R, Whitton A, Faragher B. A controlled study of fluoxetine and cognitive-behavioural counselling in the treatment of postnatal depression. BMJ. 1997;314:932–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Cohen LS, Viguera AC, Bouffard SM, Nonacs RM, Morabito C, Collins MH, et al. Venlafaxine in the treatment of postpartum depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:592–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:592–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Suri R, Burt VK, Altshuler LL, Zuckerbrow-Miller J, Fairbanks L. Fluvoxamine for postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1739–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Weissman AM, Levy BT, Hartz AJ, Bentler S, Donohue M, Ellingrod VL, et al. Pooled analysis of antidepressant levels in lactating mothers, breast milk, and nursing infants. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1066–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Klinger G, Stahl B, Fusar-Poli P, Merlob P. Antipsychotic drugs and breastfeeding. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2013;10:308–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Chaudron LH, Jefferson JW. Mood stabilizers during breastfeeding: A review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:79–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Sachs HC. Committee on Drugs. The transfer of drugs and therapeutics into human breast milk: An update on selected topics. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e796–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Bergink V, Bouvy PF, Vervoort JS, Koorengevel KM, Steegers EA, Kushner SA. Prevention of postpartum psychosis and mania in women at high risk. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:609–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Prevention of postpartum psychosis and mania in women at high risk. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:609–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Bergink V, Lambregtse-van den Berg MP, Koorengevel KM, Kupka R, Kushner SA. First-onset psychosis occurring in the postpartum period: A prospective cohort study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:1531–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Focht A, Kellner CH. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in the treatment of postpartum psychosis. J ECT. 2012;28:31–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Brockington IF. New York, USA: Oxford University Press; 1996. Puerperal psychosis. In: Motherhood and Mental Illness; pp. 200–84. [Google Scholar]

77. Pfuhlmann B, Stoeber G, Beckmann H. Postpartum psychoses: Prognosis, risk factors, and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002;4:185–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Postpartum psychosis. What is postpartum psychosis?

IMPORTANT

The information in this section should not be used for self-diagnosis or self-treatment. In case of pain or other exacerbation of the disease, only the attending physician should prescribe diagnostic tests. For diagnosis and proper treatment, you should contact your doctor.

In case of pain or other exacerbation of the disease, only the attending physician should prescribe diagnostic tests. For diagnosis and proper treatment, you should contact your doctor.

Postpartum psychosis is an acute mental disorder that develops in the first weeks after childbirth. Manifested by depression, insomnia, confusion, delusional ideas about the incurable illness of the child, delusions of persecution, hallucinations. The behavior of the patients becomes inadequate: they refuse to care for the newborn, harm him, and attempt suicide. Diagnosis is carried out by a psychiatrist, the main methods are clinical conversation and observation. Medical treatment, antipsychotics, antidepressants, tranquilizers are used. When the condition improves, sessions of psychotherapy and family counseling are introduced. nine0006

ICD-10

F53.1 Severe mental and behavioral disorders associated with the puerperium, not elsewhere classified

- Causes

- Pathogenesis

- Symptoms of postpartum psychosis

- Complications

- Diagnostics

- Treatment of postpartum psychosis

- Prognosis and prevention

- Prices for treatment

General

Postpartum psychosis is also called postnatal. This disorder was first described by Hippocrates in 460 BC. e. Its origin was explained by large blood loss during childbirth. More accurate studies date back to the middle of the 19th century. French psychiatrists J.-E. Esquirol and L.-V. Marse described the psychoses of young mothers as the consequences of severe somatic complications of childbirth. Currently, the prevalence of psychotic disorders has significantly decreased. In economically developed countries, their frequency is 1-1.2 cases per 1,000 women who gave birth no more than 3 months ago. The peak incidence is observed within the first 30 days after the birth of a child. nine0006

This disorder was first described by Hippocrates in 460 BC. e. Its origin was explained by large blood loss during childbirth. More accurate studies date back to the middle of the 19th century. French psychiatrists J.-E. Esquirol and L.-V. Marse described the psychoses of young mothers as the consequences of severe somatic complications of childbirth. Currently, the prevalence of psychotic disorders has significantly decreased. In economically developed countries, their frequency is 1-1.2 cases per 1,000 women who gave birth no more than 3 months ago. The peak incidence is observed within the first 30 days after the birth of a child. nine0006

postpartum psychosis

Causes

Official data confirm that more than half of women with postnatal psychosis have mental disorders (schizophrenia, depression, MDP) or a hereditary predisposition to them. The exact causes of the pathology are unknown, but several groups of triggers have been identified - factors contributing to its debut:

- Complications of pregnancy, childbirth.

An acute psychotic state is often caused by the death of a newborn, premature birth, threatened miscarriage. The association of the disorder with massive blood loss and sepsis, identified in ancient times, is confirmed. nine0016

An acute psychotic state is often caused by the death of a newborn, premature birth, threatened miscarriage. The association of the disorder with massive blood loss and sepsis, identified in ancient times, is confirmed. nine0016 - Hormonal disorders. The end of pregnancy is always associated with a change in the level of hormones in a woman's body. Mental disorders develop on the basis of a sharp decrease in the synthesis of progesterone, estrogen, thyroxine.

- CNS lesion. Psychosis often occurs with neurological diseases, after brain injuries, neuroinfections, intoxications. Sometimes the disorder is provoked by the use of scopolamine in combination with lidol for pain relief in childbirth.

- Anxious and suspicious personality traits. Women with high emotional tension, low adaptive abilities, and a tendency to predict failures are more prone to depression and the formation of delusional ideas. The process of childbirth becomes a stressful situation for them, triggering a mental disorder.

nine0016

nine0016 - Unfavorable psychosocial environment. Risk factors are unwanted pregnancy, rejection of the child by the mother, financial difficulties, unsettled life, divorce from a spouse. Psychoses are often diagnosed in parturient women leading an asocial lifestyle (drug addiction, alcoholism, prostitution).

Pathogenesis

According to the mechanism of origin, postpartum psychosis is reactive. It develops in response to a traumatic event - childbirth. It is based on the experience of fear of death, violation of the integrity of one's own personality, restriction of freedom, lack of love of others (shift of attention from a woman to a child). An unfavorable background for the onset of psychosis is psychophysiological asthenization - depletion of energy, a decrease in resistance to stress factors. There comes a state of decompensation of nervous adaptive mechanisms. nine0006

At the neurophysiological level, there is a violation of reciprocal inhibitory interactions between the cortex and subcortical brain structures, between the anterior and posterior hypothalamus - the highest centers of regulation of autonomic functions and emotions. The balance of activation of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system, the ratio of the main neurotransmitters (serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, GABA) change. According to psychodynamic theory, postpartum psychosis results from a conflict between the mother's real desires and the situation of motherhood. nine0006

The balance of activation of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system, the ratio of the main neurotransmitters (serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, GABA) change. According to psychodynamic theory, postpartum psychosis results from a conflict between the mother's real desires and the situation of motherhood. nine0006

Symptoms of postpartum psychosis

Psychosis begins to manifest 2-3 days after the completion of childbirth, when a woman is aware of the changes that have occurred in her life. Symptoms may develop gradually or rapidly. Initially, there is insomnia, anxiety, restlessness, fatigue, fatigue. The emotional background is stably reduced. Then suspicion and alertness begin to grow. Overvalued ideas are formed about the state of the child's health, about the presence of diseases in him or in himself. Consciousness becomes confused, speech - abrupt, illogical. nine0006

Suspicion is constantly increasing. Often, mothers closely observe the newborn during sleep and feeding, examining him, listening to his breathing and heartbeat, revealing imaginary incurable, fatal diseases. Patients begin to accuse doctors and close relatives of being indifferent to the condition of the baby, of deliberate unwillingness to treat him. Secretly from those around them, they give him various medicines, carry out “procedures” that can cause real harm (dip in cold water, leave him without clothes and diapers). nine0006

Patients begin to accuse doctors and close relatives of being indifferent to the condition of the baby, of deliberate unwillingness to treat him. Secretly from those around them, they give him various medicines, carry out “procedures” that can cause real harm (dip in cold water, leave him without clothes and diapers). nine0006

In another version of the course of psychosis, mothers lose interest in babies, do not show care and love. Overprotection turns into a feeling of hatred. Delusional thoughts are expressed about the substitution of the child, the infusion of evil spirits, demons into him, about the imminent inevitable death. In severe cases, auditory hallucinations are noted. Voices urge women to kill a newborn, attempts are often made to strangle him. Throughout the disease, the criticism of patients to their condition is disturbed - delusions and hallucinations are not recognized, they are not regarded as pathological. nine0006

Complications

Without timely diagnosis and treatment, postpartum psychosis is a danger to the life, health of the baby and mother. On the basis of hallucinations and delusions, inappropriate behavior is formed - patients try to commit suicide, having previously killed the baby. There are known cases of strangulation, falling from a height of a woman and a newborn. With a sluggish psychotic process, when indifference and detachment gradually increase, the child does not receive sufficient emotional and sensory stimulation, lags behind in physical and mental development, and suffers from neurotic disorders (enuresis, nightmares, phobias) from an early age. nine0006

On the basis of hallucinations and delusions, inappropriate behavior is formed - patients try to commit suicide, having previously killed the baby. There are known cases of strangulation, falling from a height of a woman and a newborn. With a sluggish psychotic process, when indifference and detachment gradually increase, the child does not receive sufficient emotional and sensory stimulation, lags behind in physical and mental development, and suffers from neurotic disorders (enuresis, nightmares, phobias) from an early age. nine0006

Diagnostics

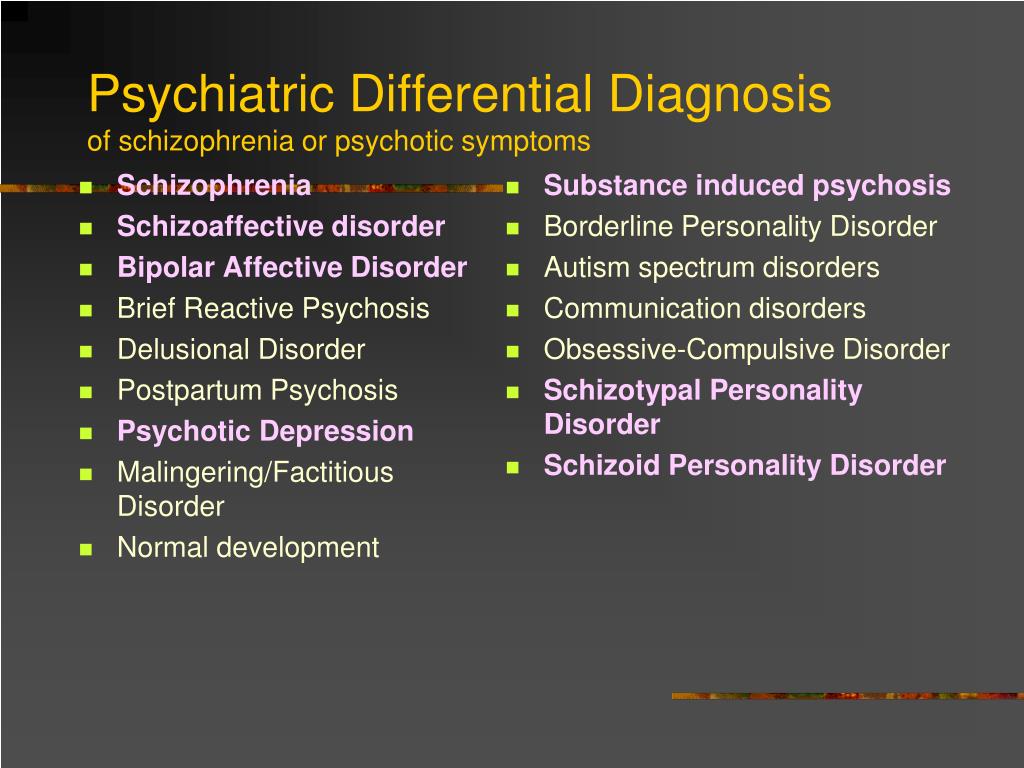

Postpartum psychosis presents with classic signs of acute psychopathology, so making an accurate diagnosis can be difficult. An important role in the process of identifying the disease is played by the patient's relatives, it is they who most often pay attention to changes in the behavior and emotional reactions of a young mother. Professional diagnostics is performed by a psychiatrist, in addition, pathopsychological, gynecological and neurological examinations may be required to differentiate postnatal psychosis from schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder, depression, hypothyroidism, Cushing's syndrome. Specific diagnostic methods include: nine0006

Specific diagnostic methods include: nine0006

- History taking. The doctor examines the medical documentation about the course of childbirth and pregnancy, finds out the presence of a hereditary burden for mental disorders, the patient's existing psychiatric diagnoses, postpartum depression, psychosis after previous pregnancies. The material and living conditions of life, the presence of a spouse, the patient's attitude to conception, pregnancy, and the birth of a child are taken into account.

- Clinical conversation. In direct contact with the patient, the psychiatrist evaluates the productivity of contact, the purposefulness of thinking and speech, and the logic of reasoning. With a psychotic disorder, women express delusional ideas in detail, are concentrated on their own experiences, and do not always answer in accordance with the questions of a specialist. nine0016

- Surveillance. During the conversation, the doctor observes the behavior and emotions, determines their adequacy, the safety of arbitrary control, motivation.

Psychosis is characterized by alertness and distrust, inconsistency of reactions to the examination situation, the predominance of dysphoric and / or depressive affect, and the absence of a critical attitude towards one's behavior.

Psychosis is characterized by alertness and distrust, inconsistency of reactions to the examination situation, the predominance of dysphoric and / or depressive affect, and the absence of a critical attitude towards one's behavior.

Treatment of postpartum psychosis

Therapy of an acute condition is carried out in a hospital setting. Quite often, women are sent to psychiatric departments and neuropsychiatric dispensaries from the maternity hospital. At the time of intensive treatment, the child is separated from the mother, entrusting care to close relatives. Comprehensive assistance includes the following areas: nine0006

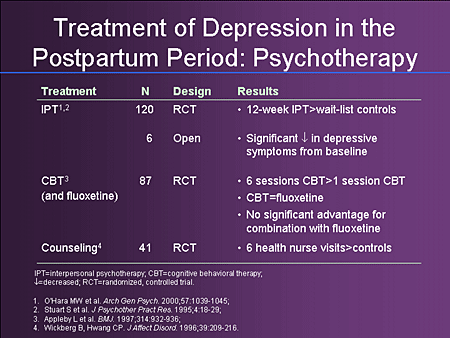

- Pharmacotherapy. At the acute stage of the disorder, the main task is to relieve psychotic symptoms. Neuroleptics, normotimics, tranquilizers, antidepressants are prescribed. For the period of taking medications, it is necessary to exclude breastfeeding by choosing artificial mixtures for feeding the child.

- Psychotherapy.

After the elimination of the symptoms of psychosis, a period of awareness of the patient of her actions, feelings, and the presence of the disease begins. This provokes depression, guilt and self-hatred. To stabilize the emotional state and correct negative attitudes, techniques of the cognitive-behavioral direction, psychoanalysis are used. nine0016

After the elimination of the symptoms of psychosis, a period of awareness of the patient of her actions, feelings, and the presence of the disease begins. This provokes depression, guilt and self-hatred. To stabilize the emotional state and correct negative attitudes, techniques of the cognitive-behavioral direction, psychoanalysis are used. nine0016 - Family assistance and rehabilitation. The support of loved ones and the correct organization of the daily routine are important. Relatives organize round-the-clock monitoring of the patient, perform baby care procedures together with the mother. It is important to spend time with a young mother, talk, distract from painful thoughts, control the regular intake of drugs prescribed by a psychiatrist.

Prognosis and prevention

Postpartum psychosis has a favorable outcome, subject to successful recovery from depression, support from loved ones, and the absence of mental illness. Prevention is based on the correct physical and psychological preparation of a woman for pregnancy and the process of childbirth. Expectant mothers need to pay attention to planning to minimize the risk of complications. It is recommended to attend courses in childcare skills, master breathing and relaxation techniques in childbirth, share your experiences with your husband, parents, close friends, and if you have severe anxiety, seek help from a psychologist. nine0006

Expectant mothers need to pay attention to planning to minimize the risk of complications. It is recommended to attend courses in childcare skills, master breathing and relaxation techniques in childbirth, share your experiences with your husband, parents, close friends, and if you have severe anxiety, seek help from a psychologist. nine0006

You can share your medical history, what helped you in the treatment of postpartum psychosis.

Sources

- Features of clinical manifestations and treatment of postpartum psychosis/ Zhuk TP, Dudal LV// Medicine and ecology. – 2014.

- Postpartum psychosis - a significant problem of modern medicine / Mishchenko AN, Mishchenko MM// Modern scientific research and development. - 2017 - No. 8 (16).

- Pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period: physiology, psychopathology, psychotherapy and psychoprophylactic preparation / Stanko E.P., Liskovich V.A. and others - 2005.

- This article was prepared based on the materials of the site: https://www.

krasotaimedicina.ru/

krasotaimedicina.ru/

IMPORTANT

Information from this section cannot be used for self-diagnosis and self-treatment. In case of pain or other exacerbation of the disease, only the attending physician should prescribe diagnostic tests. For diagnosis and proper treatment, you should contact your doctor.

Mental disorders of the reproductive cycle in women | Medvedev

1. Woods NF, Smith-DiJulio K, Percival DB, Tao EY, Mariella A, Mitchell S. Depressed mood during the menopausal transition and early postmenopause: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study. menopause. 2008;15(2):223–232. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181450fc2

2. Gale S, Harlow BL. Postpartum mood disorders: a review of clinical and epidemiological factors. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;24(4):257–266. doi: 10.3109/01674820309074690 PMID: 14702886

3. Graziottin A, Serani A. Depression and the menopause: why antidepressants are not enough? menopause. 2009;15(2):76–81. doi: 10.1258/ mi.2009.009021

2009;15(2):76–81. doi: 10.1258/ mi.2009.009021

4. Dubnitskaya EB. Non-psychotic depressions associated with the reproductive aging of women (lecture). Mental disorders in general medicine. 2010;4:18–21.

5. Kamenets GY. Depressive disorders developing after oophorectomy. Moscow: MEDpress-inform. 2002:608 p.

6. Mendelevich VD. Gynecological psychiatry. (Clinic, diagnostics, therapy). Kazan. 1996:337 p.

7. Pearlstein TB. Hormones and depression: what are the facts about premenstrual syndrome, menopause, and hormone replacement therapy? Am J Obstet Gynecol. nineteen95;173(2):646–653. doi: 10.1016/00029378(95)

-x PMID: 7645647

8. Seeman MV. Psychopathology in women and men: focus on female hormones. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(12):1641–1647. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.12.1641

9. Tyuvina NA, Voronina EO, Balabanova VV, Goncharova EM. The relationship and mutual influence of menstrual-generative function and depressive disorders in women. Neurology, neuropsychiatry, psychosomatics. 2018;10(2):45–51. doi: 10.14412/2074-2711-2018-2-45-51

2018;10(2):45–51. doi: 10.14412/2074-2711-2018-2-45-51

10. Hippocrates. Works: in 3 volumes. Publishing house "Book on demand". 2015:740 p. nine0006

11. Steiner M, Yonkers KA, Eriksson E. (eds). Mood Disorders in Women. Martin Dunitz: London. 2000:207–232.

12. Freud Z. Introduction to psychoanalysis. Moscow: AST. 2019:544 p. ISBN 978-5-17-092902-3

13. Vasilyeva AV. Problems of women's mental health - an interdisciplinary perspective. breast cancer. Medical review. 2018;2(10):51–56.

14. Mazo GE. Depression associated with the reproductive cycle in women. Materials of the scientific and practical conference (October 29, 2018, Moscow): Collection of materials / Ed. red. G.P. Kostyuk. M.: KDU; University book. 2019:442–448.

15. Frank RT. The hormonal causes of premenstrual tension. Arch of Neur and Psychiatry. Nov. 1931;26:1052–1057.

16. Mazo GE, Gorobets LN. Premenstrual syndrome: a psychiatrist's perspective. Mental disorders in general medicine. 2017;3–4:31–36.

2017;3–4:31–36.

17. Vikhlyaeva EM. Neuroendocrine gynecological syndromes (clinical lecture). M. 1971:49 p.

18. Gold JH. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder. What's that? JAMA. 1997;278(12):1024–1025.

19. Ledina AV, Prilepskaya VN, Akimkin VG. The feasibility and effectiveness of educational programs for patients suffering from premenstrual syndrome (results of a cohort cross-sectional study). Pharmateka. 2014;12(285):38–43.

20. Smetnik VP, Tumilovich LG. Non-operative gynecology: a guide for physicians. 3rd ed., revised. and additional Moscow: Medical Information Agency. 2006.

21. Serova TA. Women's health: the menstrual cycle and hormones in classical and alternative medicine. Rostov-on-Don: Phoenix. 2000:413 p. ISBN 5-222-01061-9

22. Tatarchuk TF, Ventskovskaya IB, Shevchuk TV. Premenstrual syndrome. Kiev: Zapovit. 2003;111–146.

23. Campagne DM, Campagne G. The premenstrual syndrome revisited. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;130(1):4–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.06.020 Epub 2006 Aug 17. PMID: 16916572

2007;130(1):4–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.06.020 Epub 2006 Aug 17. PMID: 16916572

24. Endicott J. History, evolution, and diagnosis of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61 Suppl 12:5–8.

25. Hardoy MC, Serra M, Carta MG, Contu P, Pisu MG, Biggio G. Increased neuroactive steroid concentrations in women with bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26(4):379-384. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000229483.52955.ec

26. Sassoon SA, Colrain IM, Baker FC. Personality disorders in women with severe premenstrual syndrome. Arch Women's Mental Health. 2011;14(3):257–264. doi: 10.1007/s00737-011-0212-8

27. Tyuvina NA, Nikolaev Autonomous Okrug. Infertility and mental disorders in women. Message 1. Neurology, neuropsychiatry, psychosomatics. 2019;11(4):117–124. doi: 10.14412/2074-2711-20194-117-124

28. Davies C, Segre G, Estradé A, Radua J, De Micheli A, Provenzani U, Oliver D, Salazar de Pablo G, Ramella-Cravaro V, Besozzi M, Dazzan P, Miele M, Caputo G, Spallarossa C, Crossland G, Ilyas A, Spada G, Politi P, Murray RM, McGuire P, Fusar-Poli P. Prenatal and perinatal risk and protective factors for psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(5):399–410. doi: 10.1016/S22150366(20)30057-2

Prenatal and perinatal risk and protective factors for psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(5):399–410. doi: 10.1016/S22150366(20)30057-2

. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):422. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-01114-8

30. Loomans EM, van Dijk AE, Vrijkotte TG, van Eijsden M, Stronks K, Gemke RJ, Van den Bergh BR. Psychosocial stress during pregnancy is related to adverse birth outcomes: results from a large multi-ethnic community-based birth cohort. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23(3):485–491. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks097

31. Pearson RM, Fernyhough C, Bentall R, Evans J, Heron J, Joinson C, Stein AL, Lewis G. Association between maternal depressogenic cognitive style during pregnancy and offspring cognitive style 18 years later. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(4):434–441. doi:10.1176/appi. ajp.2012.12050673

32. Srinivasan R, Pearson RM, Johnson S, Lewis G, Lewis G. Maternal perinatal depressive symptoms and offspring psychotic experiences at 18 years of age: a longitudinal study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(5):431–440. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30132-2

Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(5):431–440. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30132-2

33. Udagawa J, Hino K. [Impact of Maternal Stress in Pregnancy on Brain Function of the Offspring]. Nihon Eiseigaku Zasshi. 2016;71(3):188–194. Japanese. doi: 10.1265/jjh.71.188

34. Morel Y, Roucher F, Plotton I, Goursaud C, Tardy V, Mallet D. Evolution of steroids during pregnancy: Maternal, placental and fetal synthesis. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2016;77(2):82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ando.2016.04.023

35. Sandman CA, Glynn L, Schetter CD, Wadhwa P, Garite T, Chicz-DeMet A, Hobel C. Elevated maternal cortisol early in pregnancy predicts third trimester levels of placental corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH): priming the placental clock. Peptides. 2006;27(6):1457–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.10.002

36. Ulrich-Lai YM, Herman JP. Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(6):397–409. doi: 10.1038/nrn2647

37. Yang N, Ginsburg GS, Simmons LA. Personalized medicine in women’s obesity prevention and treatment: implications for research, policy and practice. Obes Rev. 2013;14(2):145–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1467789X.2012.01048.x

Personalized medicine in women’s obesity prevention and treatment: implications for research, policy and practice. Obes Rev. 2013;14(2):145–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1467789X.2012.01048.x

38. Gardanova ZhR, Bresso TI, Esaulov VI. Features of the formation of maternal dominant in young girls. Science, technology and education. 2017;41(11):70–74. nine0006

39. Jansson T, Powell TL. Role of the placenta in fetal programming: underlying mechanisms and potential interventional approaches. Clin Sci (Lond). 2007;113(1):1–13. doi: 10.1042/CS20060339

40. Monk C, Georgieff MK, Xu D, Hao X, Bansal R, Gustafsson H, Spicer J, Peterson BS. Maternal prenatal iron status and tissue organization in the neonatal brain. Pediatric Res. 2016;79(3):482–488. doi: 10.1038/ pr.2015.248

41. Akarachkova ES, Artemenko AR, Belyaev AA. Maternal stress and child health in the short and long term. breast cancer. Medical review. 2019;3(3):26–32.

42. Beijers R, Buitelaar JK, de Weerth C. Mechanisms underlying the effects of prenatal psychosocial stress on child outcomes: beyond the HPA axis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(10):943–956. doi: 10.1007/ s00787-014-0566-3

Mechanisms underlying the effects of prenatal psychosocial stress on child outcomes: beyond the HPA axis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(10):943–956. doi: 10.1007/ s00787-014-0566-3

43. Evans J, Heron J, Patel RR, Wiles N. Depressive symptoms during pregnancy and low birth weight at term: longitudinal study. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:84–85. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.016568

44. Manchenko DM, Glazova NYu, Levitskaya NG. Experimental studies of the effects of prenatal use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Materials of the scientific-practical conference (29October 2018, Moscow): collection of materials / Ed. G.P. Kostyuk. M.: KDU; University book. 2019:636–644.

45. Maternal mental health and child health and development in low and middle income countries. Report of the WHO meeting. Geneva, World Health Organization. 2008.

46. Staneva AA, Bogossian F, Wittkowski A. The experience of psychological distress, depression, and anxiety during pregnancy: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research. midwifery. 2015;31(6):563–573. doi: 10.1016/j. midw.2015.03.015

midwifery. 2015;31(6):563–573. doi: 10.1016/j. midw.2015.03.015

47. Alder J, Fink N, Bitzer J, Hösli I, Holzgreve W. Depression and anxiety during pregnancy: a risk factor for obstetric, fetal and neonatal outcome? A critical review of the literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;20(3):189–209. doi: 10.1080/14767050701209560

48. Brunton PJ. Effects of maternal exposure to social stress during pregnancy: consequences for mother and offspring. reproduction. 2013;146(5):–R175 - 189. doi: 10.1530/REP-13-0258

49. Martinez-Torteya C, Katsonga-Phiri T, Rosenblum KL, Hamilton L, Muzik M. Postpartum depression and resilience predict parenting sense of competence in women with childhood maltreatment history. Arch Women's Mental Health. 2018;21(6):777–784. doi: 10.1007/s00737-018-0865-7

50. Marques AH, Bjørke-Monsen AL, Teixeira AL, Silverman MN. Maternal stress, nutrition and physical activity: Impact on immune function, CNS development and psychopathology. Brain Res. 2015;1617:28–46. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.10.051

Brain Res. 2015;1617:28–46. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.10.051

51. Beversdorf DQ, Stevens HE, Jones KL. Prenatal Stress, Maternal Immune Dysregulation, and Their Association With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20(9):76. doi: 10.1007/s11920018-0945-4

52. Scheinost D, Sinha R, Cross SN, Kwon SH, Sze G, Constable RT, Ment LR. Does prenatal stress alter the developing connectome? Pediatric Res. 2017;81(1–2):214–226. doi: 10.1038/pr.2016.197

53. Ulmer-Yaniv A, Djalovski A, Priel A, Zagoory-Sharon O, Feldman R. Maternal depression alters stress and immune biomarkers in mother and child. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(12):1145–1157. doi: 10.1002/da.22818

54. Reynolds RM. Antenatal glucocorticoid treatment for preterm birth: considerations for the developing foetus. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2013;78(5):665–666. doi: 10.1111/cen.12073

55. Douros K, Moustaki M, Tsabouri S, Papadopoulou A, Papadopoulos M, Priftis KN. Prenatal Maternal Stress and the Risk of Asthma in Children. Front Pediatrician. 2017;5:202. doi: 10.3389/fped.2017.00202

Front Pediatrician. 2017;5:202. doi: 10.3389/fped.2017.00202

56. Elwenspoek MMC, Kuehn A, Muller CP, Turner JD. The effects of early life adversity on the immune system. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;82:140–154. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.05.012

57. Esquirol É. Des maladies mentales. 1838.

58. Spinelli MG. Psychiatric Disorders During Pregnancy and Postpartum. J Am Med Women's Ass'n. 1998;53:165.

59. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing. nineteen94:886 ISBN 978-0-89042-061-4.

60. Munk-Olsen T, Laursen TM, Mendelson T, Pedersen CB, Mors O, Mortensen PB. Risks and predictors of readmission for a mental disorder during the postpartum period. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(2):189–195. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.528

61. Gilden J, Kamperman AM, Munk-Olsen T, Hoogendijk WJG, Kushner SA, Bergink V. Long-Term Outcomes of Postpartum Psychosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(2):19-r12906. doi: 10.4088/JCP.19r12906

J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(2):19-r12906. doi: 10.4088/JCP.19r12906

62. National Collaborating Center for Mental Health (UK). Antenatal and Postnatal Mental Health: The NICE Guideline on Clinical Management and Service Guidance. Leicester (UK): British Psychological Society. 2007.

63. Matthey S, Barnett B, Howie P, Kavanagh DJ. Diagnosing postpartum depression in mothers and fathers: whatever happened to anxiety? J Affect Discord. 2003;74(2):139–147. doi: 10.1016/s01650327(02)00012-5

64. Reck C, Stehle E, Reinig K, Mundt C. Maternity blues as a predictor of DSM-IV depression and anxiety disorders in the rst three months postpartum. J Affect Discord. 2009;113(1–2):77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.05.003

65. Heron J, Hanson JV, Whitaker D. Effect before cause: supramodal recalibration of sensorimotor timing. PLOS One. 2009;4(11):e7681. doi: 10.1371/journal. pone.0007681

66. Webster JD. An exploratory analysis of a self-assessed wisdom scale. JAdult Dev. 2003;10:13–22. doi: 10.1023/A:1020782619051

2003;10:13–22. doi: 10.1023/A:1020782619051

67. Hirst KP, Moutier CY. Postpartum major depression. Am Fam Physician. 201015;82(8):926–933.

68. Pribytkov AA. Clinical features of depressive disorders of the neurotic level in the postpartum period. Social and clinical psychiatry. 2005;4:63–66. nine0006

69. Mishchenko AN, Mishchenko MM. Postpartum psychosis is a significant problem in modern medicine. Modern scientific research and development. 2017;8(16):360–362.

70. World Health Organization. reproductive health strategy. Geneva: WHO. 2004 (WHO/RHR/04.8).

71. Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, de Mouzon J, Ishihara O, Mansour R, Nygren K, Sullivan E, Vanderpoel S. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) and the World Health Organization (WHO) revised glossary of ART terminology. fertility and sterility. 2009;92(5):15–282. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.09.009

72. Levakov SA, Pavlova SA, Bugrova TI, Kedrova AG. A modern take on a barren marriage. Clinical practice. 2010;1(3):92–97. doi: 10.17816/ clinpract1392-97

A modern take on a barren marriage. Clinical practice. 2010;1(3):92–97. doi: 10.17816/ clinpract1392-97

73. Weidner K, Einsle F, Siedentopf F, Stöbel-Richter Y, Distler W, Joraschky P. Psychological and physical factors influencing the health-related quality of life of patients of a department of gynecology in a university hospital. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;27(4):257–265. doi: 10.1080/01674820600999795

74. Tyuvina NA, Korobkova IG. Comparative characteristics of the clinical features of depression in bipolar affective disorder type I and II. Neurology, neuropsychiatry, psychosomatics. 2016;8(1):22–28. doi: 10.14412/2074-2711-2016-1-2228

75. Van den Broeck U, Emery M, Wischmann T, Thorn P. Counselling in infertility: individual, couple and group interventions. Patient Education Counts. 2010;81(3):422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.10.009

76. Dement'eva NO, Bocharov VV. Psychological aspects of the study of female infertility of "unclear etiology". Bulletin of St. Petersburg State University. 2010;12(1):131–139.

Bulletin of St. Petersburg State University. 2010;12(1):131–139.

77. Rooney KL, Domar AD. The relationship between stress and infertility. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20(1):41–47. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2018.20.1/klrooney PMID: 29946210; PMCID: PMC6016043

78. Karimzadeh M, Rostami M, Teymouri R, Moazzen Z, Tahmasebi S. The association between parental mental health and behavioral disorders in pre-school children. Electron Physician. 2017;9(6):4497–4502. doi: 10.19082/4497

79. Volgsten H, Skoog Svanberg A, Ekselius L, Lundkvist O, Sundström Poromaa I. Risk factors for psychiatric disorders in infertile women and men undergoing in vitro fertilization treatment. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(4):1088–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.11.008 Epub 2008 Dec 31. PMID: 19118826

80. Holley SR, Pasch LA, Bleil ME, Gregorich S, Katz PK, Adler NE. Prevalence and predictors of major depressive disorder for fertility treatment patients and their partners. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(5):1332–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.02.018

doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.02.018

81. Peterson BD, Sejbaek CS, Pirritano M, Schmidt L. Are severe depressive symptoms associated with infertility-related distress in individuals and their partners? Hum reproduction. 2014;29(1):76–82. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det412

82. Shani C, Yelena S, Reut BK, Adrian S, Sami H. Suicidal risk among infertile women undergoing in-vitro fertilization: Incidence and risk factors. Psychiatry Res. 2016;240:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.003

83. Polishchuk YuI, Baranskaya IV, Golubtsova LI, Letnikova ZV. The main factors determining the development of conditions of loneliness with depressive disorders at a later age. Materials of the XIII Congress of Psychiatrists of Russia. October 10–13, 2000: 164–165. nine0006

84. Schmidt PJ, Murphy JH, Haq N, Rubinow DR, Danaceau MA. Stressful life events, personal losses, and perimenopause-related depression. Arch Women's Mental Health. 2004;7(1):19–26. doi: 10.1007/s00737-0030036-2

85. Bloch A. Self-awareness during the menopause. Maturitas. 2002;41(1):61–68. doi: 10.1016/s03785122(01)00252-3

Bloch A. Self-awareness during the menopause. Maturitas. 2002;41(1):61–68. doi: 10.1016/s03785122(01)00252-3

86. Helson R., Soto C.J. Up and down in middle age: monotonic and nonmonotonic changes in roles, status, and personality. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;89(2):194–204. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.2.194

87. Bezerra A.G., Andersen M.L., Tuk S., Hachul H. Approach towards mild depression: shortest way to treat climacteric syndrome? Maturitas. 2013;74(1):105. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.10.009

88. Smetnik VP, Tkachenko NM, Glezer GA. climacteric syndrome. M. 1988: 286 p.

89. Deecher D, Andree TH, Sloan D, Schechter LE. From menarche to menopause: exploring the underlying biology of depression in women experiencing hormonal changes. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33(1):3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.10.006

90. Gibbs Z, Lee S, Kulkarni J. Factors associated with depression during the perimenopausal transition. Women's Health Issues. 2013;23(5):e301-e307. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.07.001

doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.07.001

91. Llaneza P, García-Portilla MP, Llaneza-Suárez D, Armott B, Pérez-López FR. Depressive disorders and the menopause transition. Maturitas. 2012;71(2):120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.11.017

92. Judd FK, Hickey M, Bryant C. Depression and midlife: are we overpathologising the menopause? J Affect Discord. 2012;136(3):199–211. doi: 10.1016/j. jad.2010.12.010

93. Worsley R, Davis SR, Gavrilidis E, Gibbs Z, Lee S, Burger H, Kulkarni J. Hormonal therapies for new onset and relapsed depression during perimenopause. Maturitas. 2012;73(2):127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.06.011

94. Medvedev V.E. Psychopathological aspects of involutionary hysteria. Consillium medica [women's health]. 2012;6:26–29.

95. Mendelevich VD. Psychopathology of menopause. Kazan: Kazan Publishing House. university 1992:166 p. ISBN 5-7464-0587-6

96. Bromberger JT, Assmann SF, Avis NE, Schocken M, Kravitz HM, Cordal A. Persistent mood symptoms in a multiethnic community cohort of preand perimenopausal women. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(4):347–356. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg155

Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(4):347–356. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg155

97. Volel BA, Yanshina TP. Involutionary hysteria within the dynamics of personality disorders. Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakov. 2004;11:47–54.

98. Gannushkin PB. Clinic of psychopathy, their statics, dynamics, systematics. Moscow: Sever.1933.

99. Gilyarovsky VA. Psychiatry. M.: Medgiz. 1954.

100. Kraepelin E. Zur Entartungsfrage. Zentralblatt für Nervenheilkunde und Psychiatrie. 1908;19(31):745–751.

101. Abramowitz JS, Moore EL, Braddock AE, Harrington DL. Self-help cognitive-behavioral therapy with minimal therapist contact for social phobia: a controlled trial. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2009;40(1):98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2008.04.004

102. Geyer TA. To the formulation of the question of "involutionary hysteria". Proceedings of psychiatrists of clinic I of Moscow University. nineteen27;2:45–51.

103. Bumke O. Lehrubuch des Geisteskrankheiter 1924:438–456.

104. Binfa L, Castelo-Branco C, Blümel JE, Cancelo MJ, Bonilla H, Muñoz I, Vergara V, Izaguirre H, Sarrá S, Ríos R.V. Influence of psycho-social factors on climacteric symptoms. Maturitas. 2004;48(4):425–431. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2003.11.002

105. Medvedev VE, Frolova VI, Avdoshenko KE, Vissarionov VA, Shafirova EM, Martynov SE. Pathocharacterological and pathopsychological disorders in patients of a plastic surgeon and cosmetologist. Experimental and clinical dermatocosmetology. 2012;3:60–64. nine0006

106. Medvedev VE, Frolova VI, Gushanskaya EV, Fofanova YUS, Martynov SE, Zuykova NL, Burno AM, Nekrasova SV, Salyntsev IV. Depression with eating disorders: clinic and therapy. Neurology, neuropsychiatry, psychosomatics. 2020;12(4):49–56. doi: 10.14412/2074-2711-2020-4-49-56

107. Medvedev V.E. Mental disorders with unreasonable dissatisfaction with one's own appearance in patients of a plastic surgeon and cosmetologist. Psychiatry and psychopharmacotherapy.