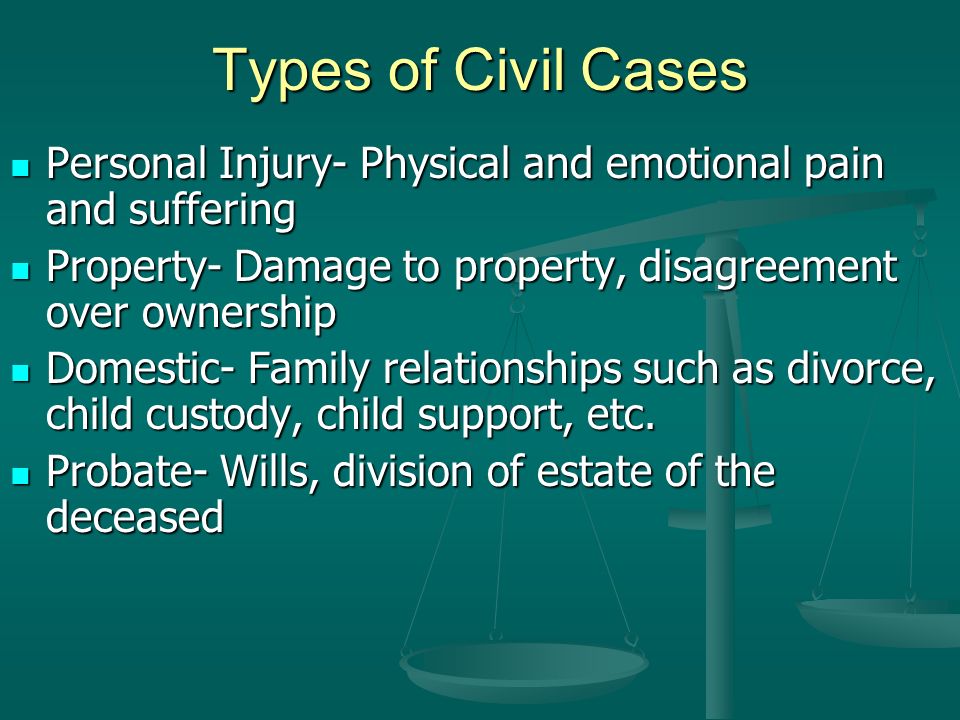

Physical and emotional pain

The Key to Treating Physical and Emotional Pain – New Harbinger Publications, Inc

August 15, 2019 | hilarycollins | Clinicians Corner

By Rachel Zoffness, author of The Chronic Pain and Illness Workbook for Teens

Everyone knows what it’s like to be in pain.

Some 100 million Americans know what it’s like to cope with unremitting chronic pain: pain lasting three months or more without respite.

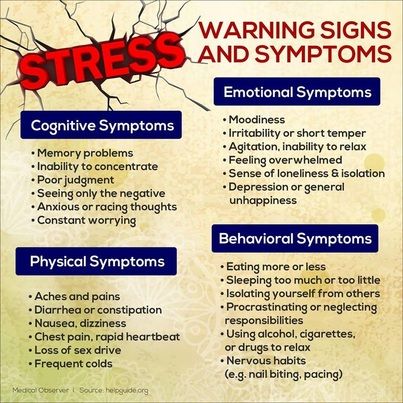

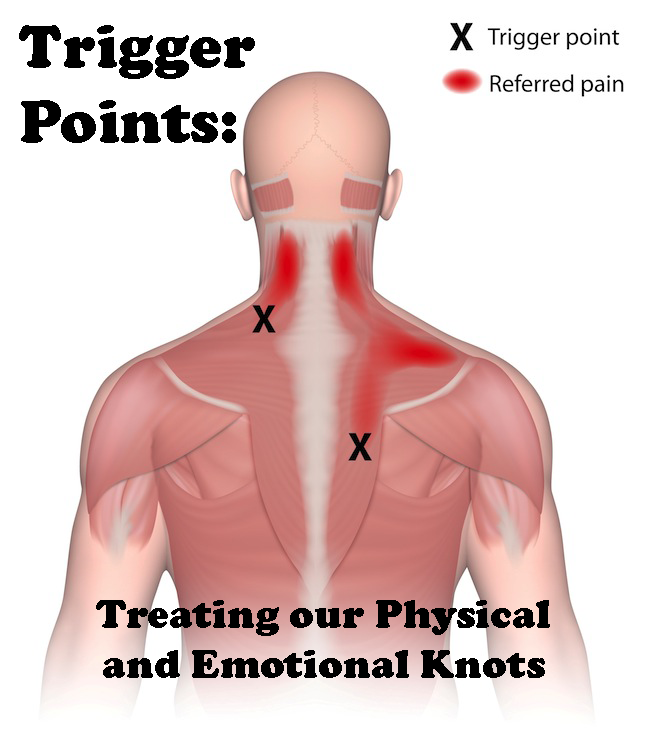

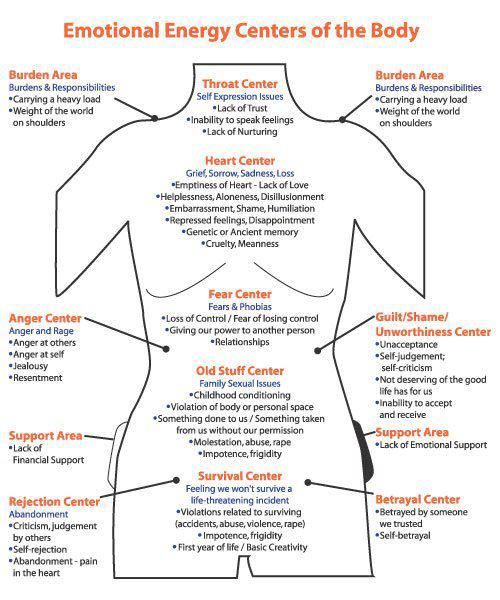

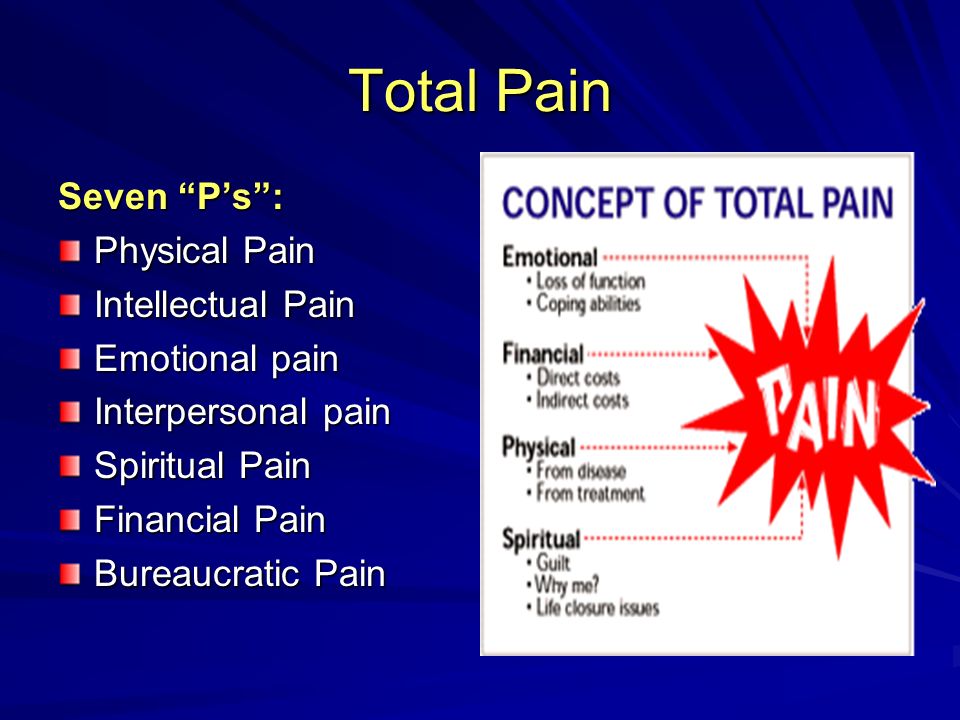

If you’re a therapist or health care provider, chances are high you’ve worked with a client in pain. The reason this is unsurprising and even expected is because “physical pain” is never just physical: it’s also emotional. Research shows that multiple parts of the brain process pain, including the prefrontal cortex (attentional and executive processes), the cerebral cortex (thoughts, beliefs), and the limbic system—your brain’s

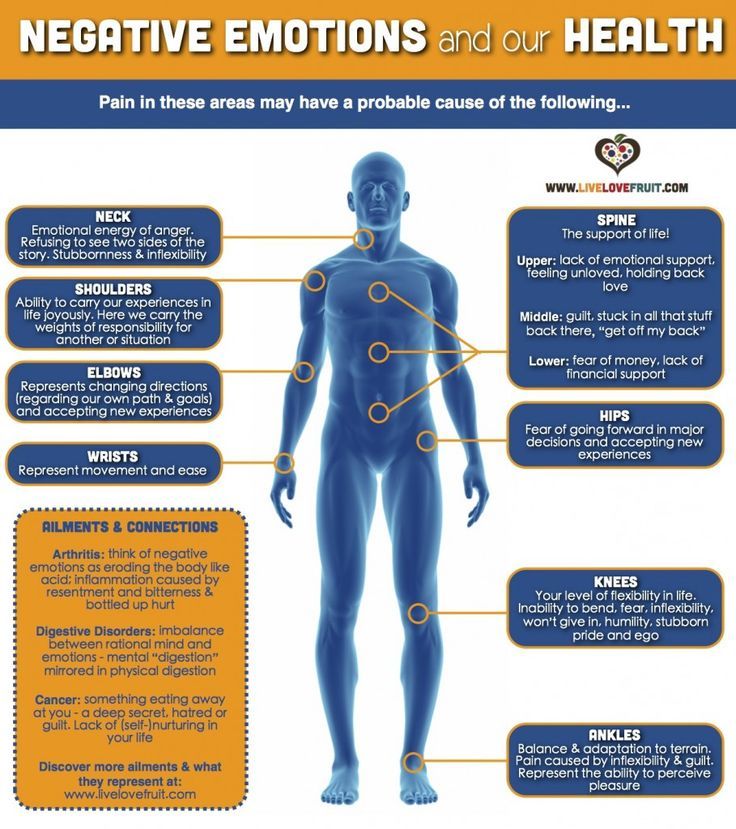

emotion center. In fact, neuroscience demonstrates that negative emotions like anxiety, stress, depression, and anger actually amplify pain, while relaxation, happiness, joy, and gratitude can reduce it.

This means that pain is never just physical; it’s also emotional. Indeed, this is the question I am asked most: “Do you treat physical pain, or emotional pain?” My answer is always: “Yes.” The brain-body divide created by Western medicine is just that: a creation. Physiologically, this divide does not exist. The brain and body are connected 100 percent of the time.

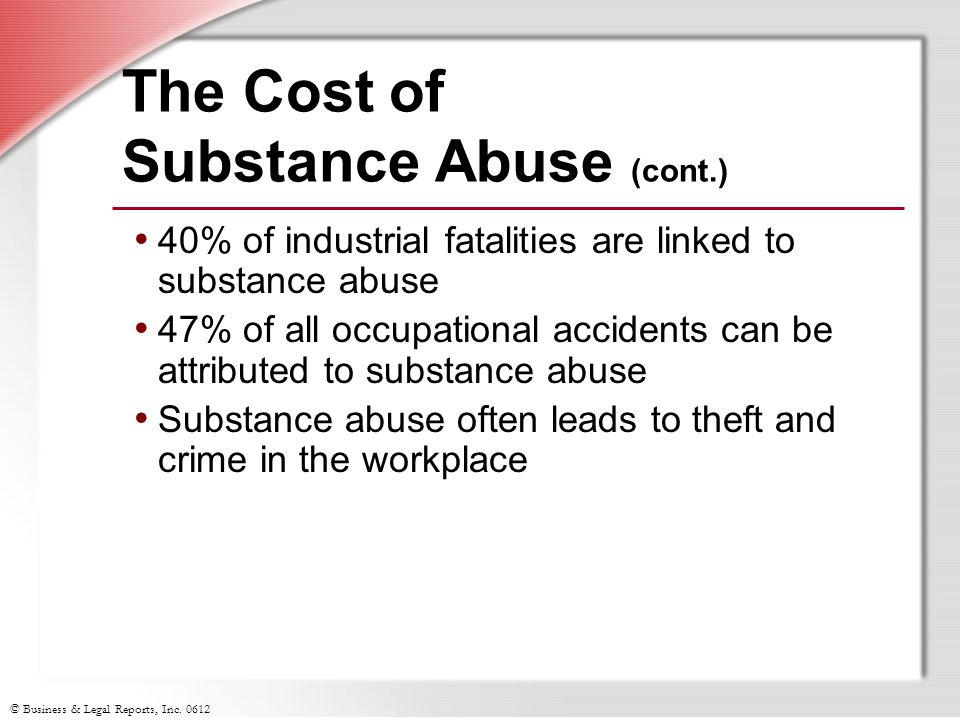

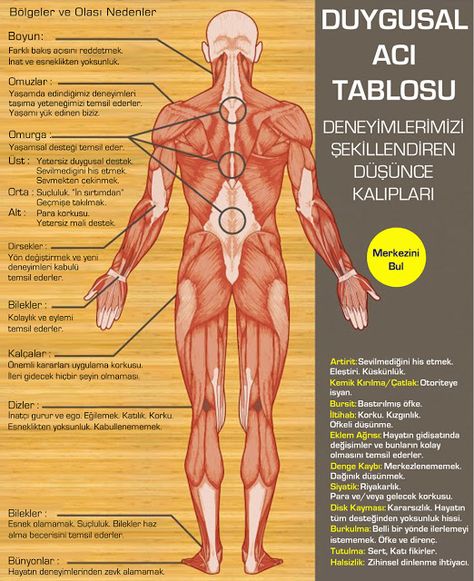

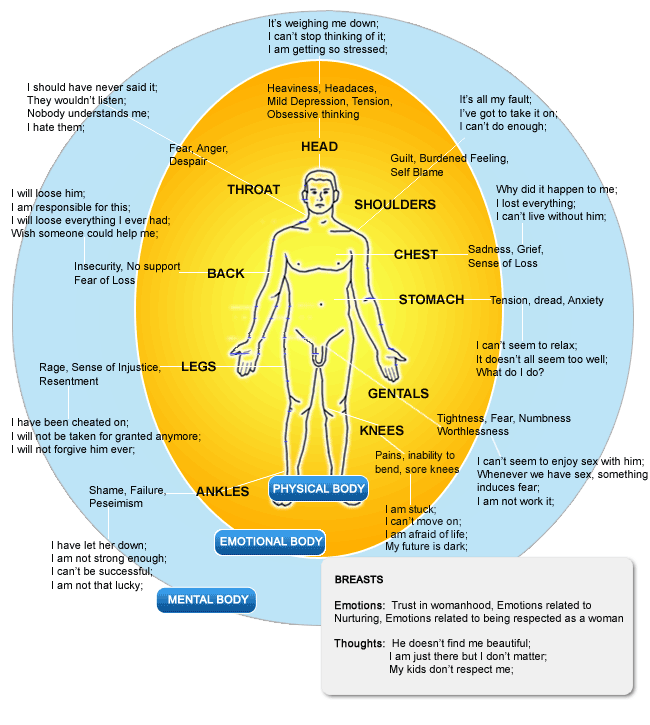

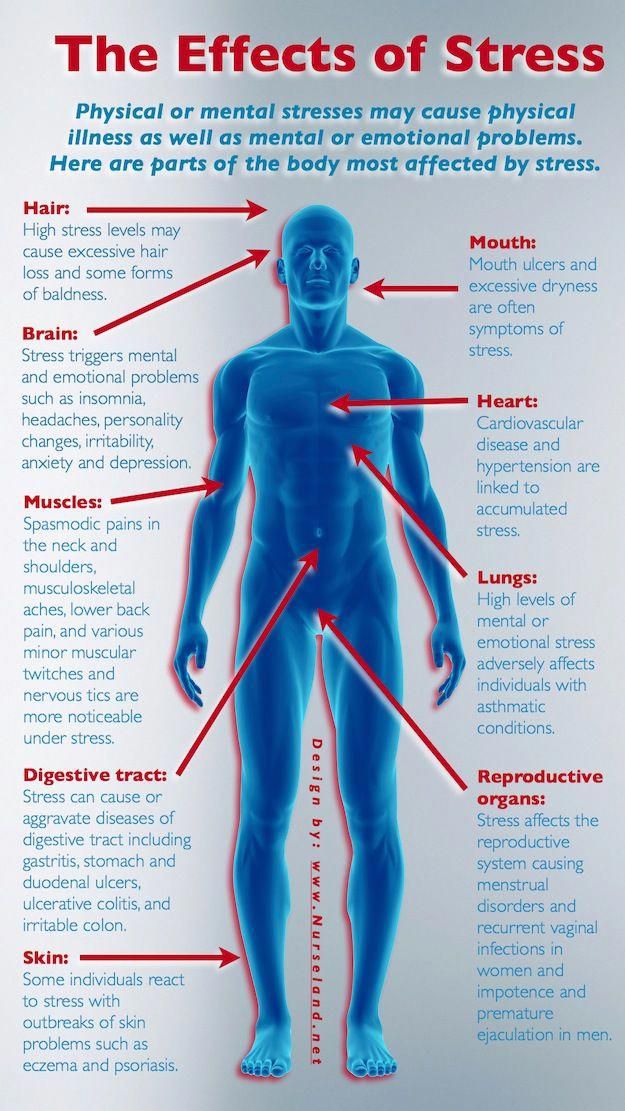

Therapists therefore necessarily treat “physical pain” because we treat emotional pain. Patients with depression, anxiety, stress, and anger regularly present with physical expressions of these difficult emotions, because emotions manifest in the body. Most of us know the experience of “butterflies” in the stomach, the terrible ache of a tension headache, the grey hairs that sprout in times of stress, “feeling something in your gut,” and the insidious shoulder-and-back pain from too much work and too little play.

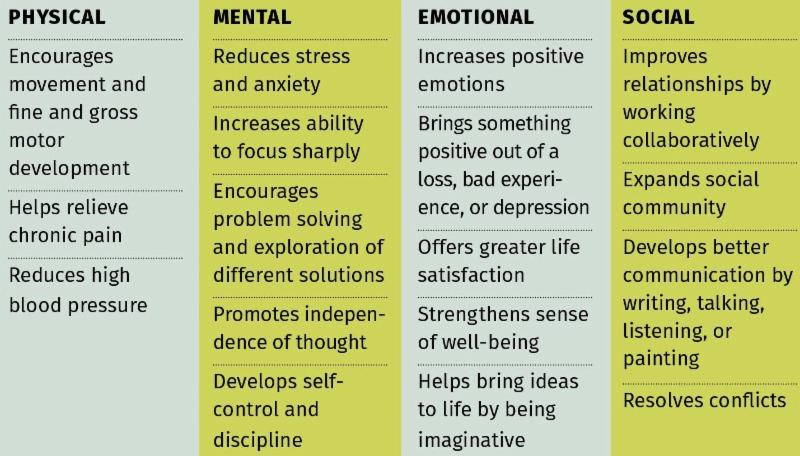

But while it’s one thing to be familiar with this phenomenon, it’s yet another to treat it. The good news is this: research demonstrates that psychosocial treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) can effectively ameliorate chronic pain. If pain is a “medical” condition, how can this possibly be? Decades of neuroscientific studies indicate that pain is not purely biomedical, produced exclusively by anatomical dysfunction or mechanical damage. Rather, chronic pain is biopsychosocial—the product of biological, psychological, and social factors all interacting to generate this condition. Therefore, successful treatments must be biopsychosocial, too. Victims of the opiate epidemic know all too well that a pill for pain simply isn’t enough.

If pain is a “medical” condition, how can this possibly be? Decades of neuroscientific studies indicate that pain is not purely biomedical, produced exclusively by anatomical dysfunction or mechanical damage. Rather, chronic pain is biopsychosocial—the product of biological, psychological, and social factors all interacting to generate this condition. Therefore, successful treatments must be biopsychosocial, too. Victims of the opiate epidemic know all too well that a pill for pain simply isn’t enough.

Pain is your body’s warning system, an adaptive response to perceived threat. If you believe you’re in danger, your brain will make pain. The words “perceived” and “believe” are not used here coincidentally. While acute pain signals danger of harm—a broken bone in need of repair, a dangerous concussion requiring rest, an infected cut requiring attention—chronic pain is the result of a sensitive false alarm, a hyperactive car alarm ringing in the absence of a burglar. After weeks and months of pain, the nervous system can become so sensitive that the sensation of pain, while very real, is no longer a reliable indicator of tissue damage. That is: the “hurt” you feel is no longer indicative of danger, or “harm.”

After weeks and months of pain, the nervous system can become so sensitive that the sensation of pain, while very real, is no longer a reliable indicator of tissue damage. That is: the “hurt” you feel is no longer indicative of danger, or “harm.”

CBT and MBSR offers skills that can teach chronic pain sufferers to quiet the overactive fight-or-flight response amplifying pain, desensitize the pain system, and turn off this false alarm. This is achieved via techniques like pacing, relaxation strategies, cognitive restructuring, biofeedback, and mindfulness to turn the volume down on pain, so that clients can resume functioning and return to life. If you are a therapist or health care provider, you can be part of the solution to America’s pain epidemic by learning more about psychosocial techniques for chronic pain.

For additional resources check out The Chronic Pain and Illness Workbook for Teens.

Rachel Zoffness, PhD, is a clinical psychologist, medical consultant, educator, and author specializing in chronic pain, medical illness, and injury. She provides cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to teens and adults, provides lectures and trainings, and serves as a consultant to hospitals and health professionals. Zoffness—also known as ‘Dr. Z’—teaches at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine, providing pain neuroscience education to medical residents and interns. She was trained at Brown; Columbia; the University of California, San Diego; San Diego State University; the New York University Child Study Center; Mount Sinai West; and the Mindful Center.

She provides cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to teens and adults, provides lectures and trainings, and serves as a consultant to hospitals and health professionals. Zoffness—also known as ‘Dr. Z’—teaches at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine, providing pain neuroscience education to medical residents and interns. She was trained at Brown; Columbia; the University of California, San Diego; San Diego State University; the New York University Child Study Center; Mount Sinai West; and the Mindful Center.

Search Our Blog

Search for:Sign Up for Our Email List

New Harbinger is committed to protecting your privacy. It's easy to unsubscribe at any time.

Recent Posts

- Justice vs. Change: Helping Clients Find Their Power October 25, 2022

- Mental Health, Mindfulness, and Teens October 19, 2022

- How to Help Teens Deal with a Breakup October 18, 2022

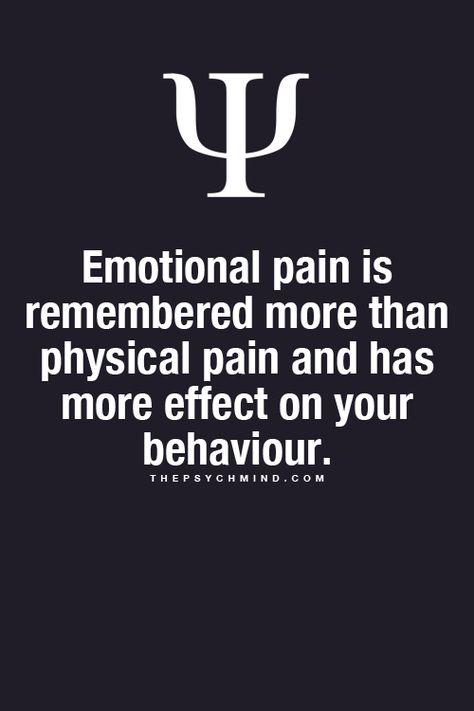

Why Emotional Pain Is Worse than Physical Pain | by Vivian Dee

While physical pain is easy to understand, emotional pain can be much trickier.

It is hard to define, hard to pinpoint the source and you never really know what to expect.Photo by Aaron Blanco on Unsplash

It is hard to define, hard to pinpoint the source and you never really know what to expect.Photo by Aaron Blanco on UnsplashEmotional pain is a feeling of hurt, anguish, or sorrow. It can come from many different sources. An example would be the death of a loved one leaving you lost and lonely.

Emotional pain is also caused by our thoughts and feelings. Guilt can come from your own sense of wrongdoing when you forget to pick up your friend’s lunch on the way home, or maybe you ate all of their cookies.

Although emotional pain is not physical, it can still be very real. It hurts us in the same way that physical pain would hurt us. The only difference is that emotional pain does not have any specific location in the body and is often described as a feeling of “tightness” in the chest or abdomen.

Many people do not understand that emotional pain, although less visible, can be far more devastating. Reasons for this include:

Emotional pain has no specific cause, so there is no specific solution to it. This means you can’t find a quick fix for it. You can’t just sprinkle some magic fairy dust on your feelings and expect them to go away.

This means you can’t find a quick fix for it. You can’t just sprinkle some magic fairy dust on your feelings and expect them to go away.

When we feel physical pain, we know it is a sign that something is wrong with the body. It is a warning to take action. But although emotions are often as painful or worse, they are rarely reliable signals. So we end up feeling emotional pain and not knowing why we feel that way.

Physical pain, for example, when you cut yourself, will go away after a while. The body will heal itself. It will be fine again in a few days or weeks. But our minds can not heal themselves when it comes to our emotions. We would have to put in conscious effort to understand those feelings.

Additionally, emotional pain is more of mental anguish and an exhaustion feeling.

Then there is the fact that we can get used to physical pain, however, we can never get used to emotional pain. It only multiplies, causing us to feel even worse than before. This is because our mind is on overdrive trying to figure out how to fix whatever has caused the emotional pain.

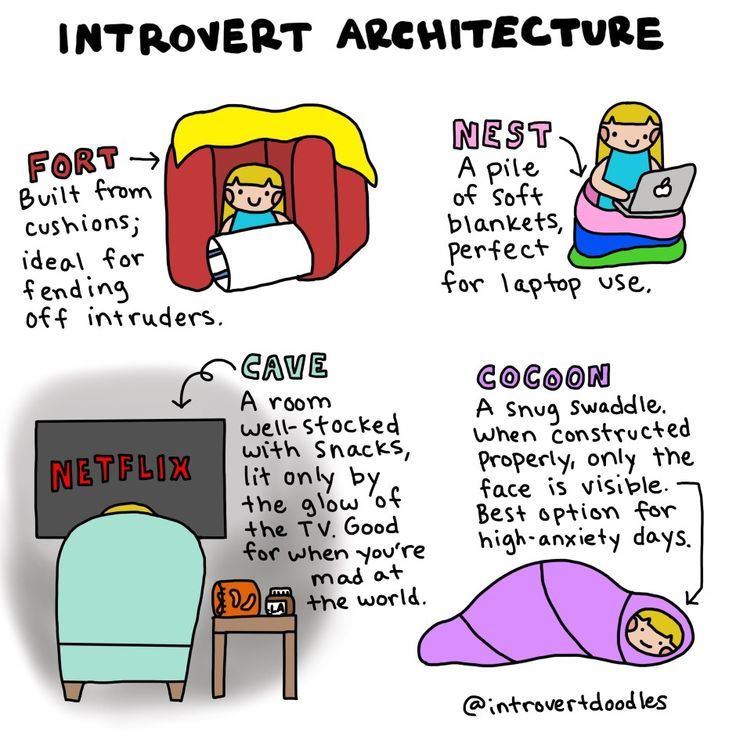

Everyone experiences emotional pain at some point, but we do not know how to cope with it. The reason for this is simple: it is not physical.

We tend to handle physical pain by avoiding it, and that works. But when we avoid our emotions, they follow us, often getting worse. So how can we deal with emotional pain?

By embracing it! By understanding it!

- Accept that you are experiencing emotional pain. It is not a weakness. We all experience emotional pain, but the way you go through it makes all the difference.

- Feel the pain. This is not to say that you need to wallow in it, but rather that you need to acknowledge its presence and allow yourself to experience it fully. You cannot heal when you ignore your pain.

- You need to figure out the cause of the emotional pain. What upset you? Maybe something happened. Did someone say something? Did something not happen? Be as specific as you can about what has caused you pain.

- Consider whether similar situations made you feel that way in the past or whether you had an underlying childhood trauma that contributed to your pain.

Reflecting on the experience helps you understand it better.

Reflecting on the experience helps you understand it better. - To let go, remind yourself that you will get through your emotional pain. You will be alright. If you made a mistake, remember that you are not perfect and mistakes are okay. Mistakes help you learn.

- The last step is to determine your course of action. We cannot control what happens to us, but we can decide how we respond. So, what are you going to do about your emotional pain?

Ultimately, knowing what you feel, why you feel it, and then knowing what to do about what you feel is how you overcome emotional pain.

In conclusion, physical pain is terrible because we can see it. However, emotional pain is much worse because we cannot see it and so we often ignore it. Learning how to deal with emotional pain is something that every person needs to do.

I hope this article has been insightful. For more articles like this:

Why Childhood Trauma Affects Adults

It is difficult to know if bad experiences during childhood will remain traumatizing for an individual in adulthood…

link. medium.com

medium.com

Is Our PERSPECTIVE Really REALITY?

If I asked what reality is, you might answer that reality is what you see, hear, taste, touch, or smell. However, this…

link.medium.com

6 Easy INFJ Self Improvement Exercises

Being an INFJ-a highly sensitive person-is a blessing but sometimes it doesn't feel that way. If you're an INFJ then…

link.medium.com

Mental pain affects the brain like physical pain, scientists say - RIA Novosti, 03/29/2011

Mental pain affects the brain like physical pain, scientists say Sciences.

2011-03-29T09:05

2011-03-29T09:05

2011-03-29T09:09

/html/head/meta[@name='og:title']/@content

3 /html/head/meta[@name='og:description']/@content

RIA Novosti

1

5

4.7

96

7 495 645-6601

Rossiya Segodnya

https: //xn---c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/Awards/

2011

RIA Novosti

1

5

4. 7

7

9000 9000

49000 7 645-6601

FSUE MIA Rossiya Segodnya

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

News

ru-RU

https://ria.ru/docs/about /copyright.html

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/

RIA Novosti

1,000 .xn--p1ai/awards/

1920

1080

True

1920

1440

True

https://cdnn21.img.ria.ru/images/20419/92/204199235_144:0: 2811:2000_1920x0_80_0_0_01bec378ea7902b2ed1ea569065342a0.jpg

1920

1920

True

RIA Novosti

1

5

4.7

9000

7 495 645-6601 9000

Federal State Unitary Enterprise MIA “Russia Today”

https: //xn---c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/Awards/

RIA Novosti

1

5

4.7

96 9000

7 495 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 646 646 495 64 64 64 646 646 495 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 646 646 495 64 646 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64 64AP

Federal State Unitary Enterprise MIA "Russia Today"

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og. xn--p1ai/awards/

xn--p1ai/awards/

MOSCOW, March 29 - RIA Novosti. Physical trauma and a strong sense of social rejection cause the same reactions in the human brain, American scientists write in an article published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Social psychologist Ethan Kross of the University of Michigan (USA) and colleagues have shown that the same areas of the brain are activated both in response to pain sensations and in response to experiences caused by strong feelings of loneliness and rejection.

"At first glance, the feeling of spilling hot coffee on yourself and the feeling of being rejected should cause very different types of pain. But our research shows that they may be even more similar than thought ", - said Cross, whose words are quoted in the message of the university.

The authors of the article showed for the first time that pain and the "feeling of abandonment" cause activity in two areas of the brain - in the secondary somatosensory and insular cortex.

For the study, scientists selected 40 people (of which 21 were women) who had experienced a breakup in a romantic relationship in the last six months and felt rejected. Each participated in two parts of the experiment - one was associated with the feeling of "social" pain, and the second - with the feeling of physical pain.

During the first part of the experiment, subjects looked at a photograph of their former partner and had to think of the most positive experience they had with that person.

During the second part of the experiment, using a special heating device applied to the left forearm of the participant, the experimenters caused pain. Subjects felt sometimes a slight warmth, and sometimes the temperature of a cup of hot coffee.

The brain activity of all participants in the experiment was monitored using functional magnetic resonance imaging. The researchers studied the brain as a whole or focused on specific areas that had previously been identified as being associated with physical pain. They also compared the data obtained with the results of 500 previous tomographic studies of reactions to pain, emotions, memory, attention switching.

They also compared the data obtained with the results of 500 previous tomographic studies of reactions to pain, emotions, memory, attention switching.

"We found that the induced feeling of rejection activates brain regions that are involved in the sensation of physical pain," concludes the scientist.

The authors of the study note that their data will help to understand how emotional experiences can cause bodily illness and lead to a wide variety of pain and mental disorders.

Naomi Eisenberger on why it hurts physically to be rejected - T&P

Biologist and social psychologist Naomi Eisenberger argues that the experience of social or emotional pain is not a fantasy out of thin air, but an evolutionary mechanism that has formed as a result of the need for social association - which ultimately leads to survival.

If you listen closely to how people describe their experiences of social exclusion, you'll notice an interesting pattern: we use words for physical pain to describe psychologically distressing events, such as "my heart is broken. " In fact, there are several ways of expressing feelings of rejection in English, not just those that usually refer to physical pain. However, the use of such words to denote alienation or isolation is typical of other languages, not just English.

" In fact, there are several ways of expressing feelings of rejection in English, not just those that usually refer to physical pain. However, the use of such words to denote alienation or isolation is typical of other languages, not just English.

Why do we describe experiences of social exclusion in terms of physical pain? Is the feeling of social isolation really comparable to physical pain, or is it just a figure of speech? In a laboratory study, we suggested that the "pain" of social rejection (social pain) is not just a lexical expression. Through a series of studies, my colleagues and I have shown that socially painful experiences, such as separation or isolation, excite processes in the same nerve regions as physical pain. Here I present the data that led us to believe that processes in physical and social pain overlap, as well as studies that directly test this overlap. I will show some, perhaps unexpected, consequences of this coincidence, as well as what this general neural circuit means for us and what it says about social pain.

Does rejection really hurt? While it may seem a bit of a stretch to say that rejection “hurts,” it makes some evolutionary sense that the suffering of physical and social pain overlaps. As a mammalian species, humans are born quite immature, unable to provide themselves with food and protection. Therefore, babies, in order to survive, need to be always close to those who care for them. Later, belonging to a social group becomes critical to survival; its members benefit from the shared responsibility of foraging for food, fighting predators, and caring for children. Based on the fact that social isolation is so detrimental to humans, it has been suggested that during our evolutionary history, the social attachment system has evolved along the lines of the physical pain system, borrowing the pain signal as a stimulus from social separation. It is likely that social bonding was so important to survival that the pain associated with physical injury was included to provide the same anguish of social isolation—so that people would strive to avoid isolation and remain close to others.

Subsequent studies have confirmed these initial findings. Subjects who admitted to feeling unwanted more often in everyday life showed more neural activity in response to an episode of social rejection. In some cases, simply looking at stimulus pictures activates nerves associated with bodily pain.

Human and animal studies have shown that similar processes occur in physical and social pain. They originate in two areas of the brain: in the anterior cingulate cortex and, to a lesser extent, in the anterior lobe of the brain. Both are involved when mammals are in physical pain or suffer from isolation.

With regard to physical pain, the anterior cingulate cortex and the anterior lobe of the brain convey the emotional, unpleasant, element of the painful experience. It can be divided into two components: sensory, which provides information about where the pain stimulus is felt, and emotional, which captures the unpleasant sensations from the stimulus - as trivial as it is, it is. After neurosurgery, during which the anterior cingulate cortex is removed to relieve intractable chronic pain, patients have reported that they can still locate the stimulus but are no longer bothered by the pain. Similar symptoms were observed with damage to the anterior lobe. Damage to the somatosensory cortex - the area responsible for the localization of pain - makes it difficult for patients to determine where the pain comes from, but leaves sensory suffering. Neuroimaging also confirms this separation. Subjects who, under hypnosis, had an increase in the pain of a stimulus without changing the sensory component showed increased activity in the anterior cingulate cortex, and not in the primary somatosensory cortex, which is responsible for the sensory element of pain.

After neurosurgery, during which the anterior cingulate cortex is removed to relieve intractable chronic pain, patients have reported that they can still locate the stimulus but are no longer bothered by the pain. Similar symptoms were observed with damage to the anterior lobe. Damage to the somatosensory cortex - the area responsible for the localization of pain - makes it difficult for patients to determine where the pain comes from, but leaves sensory suffering. Neuroimaging also confirms this separation. Subjects who, under hypnosis, had an increase in the pain of a stimulus without changing the sensory component showed increased activity in the anterior cingulate cortex, and not in the primary somatosensory cortex, which is responsible for the sensory element of pain.

Interestingly, some of the neural pathways associated with pain also contribute to specific separation behaviors that manifest in the expression of suffering. Infants of many mammalian species make special pained sounds (for example, human children cry) when weaned from a caring subject. These sounds have an adaptive purpose (for adults, this is a signal to find a baby), that is, they prevent a long separation. The dorsal and ventral divisions play a major role in the production of these voiced sufferings. Damage to these zones in monkeys is eliminated by the vocalization of suffering, while electrical stimulation in macaques leads to spontaneous painful cries.

These sounds have an adaptive purpose (for adults, this is a signal to find a baby), that is, they prevent a long separation. The dorsal and ventral divisions play a major role in the production of these voiced sufferings. Damage to these zones in monkeys is eliminated by the vocalization of suffering, while electrical stimulation in macaques leads to spontaneous painful cries.

On the basis of data revealing neural regions involved in human physical pain and separation suffering in mammals, we decided to investigate whether these regions would play a role in human socially painful experiences. In one such study, each participant was told that they would be connected via the Internet to two other people and together they would play a game of passing the ball. The participant of the experiment was connected to the MRI scanner. Through special glasses, he saw virtual incarnations of two other players with their names, as well as his own hand. By pressing a button, the participant decided who to throw the ball to.

There were no other players in reality; the participants of the experiment played with a pre-installed computer program. In the first round they were included in the game all the time, and in the second round they were socially excluded because the other two players stopped throwing the ball to them. As a response to this rejection, subjects showed strong activation in the anterior cingulate cortex and in the anterior lobes of the brain, two regions associated with physical pain. Moreover, subjects who felt more strongly about the isolation episode ("I felt rejected", "I felt unwanted") also showed higher activity in the anterior cingulate cortex, supporting the suggestion that rejection does "pain".

Finally, separation or rejection are not the only triggers for the neural activity associated with pain. Other socially painful experiences, such as bereavement, also engage these neural pathways.

Subsequent studies confirmed these initial data. Subjects who admitted to feeling unwanted more often in everyday life showed more neural activity in response to an episode of social rejection. In some cases, simply looking at stimulus pictures activates nerves associated with bodily pain. For example, viewing paintings by Edward Hopper activated the anterior cingulate cortex and the anterior lobe of the brain. In addition, socially sensitive people, when watching a video of someone making a disapproving facial expression (a possible sign of social rejection), showed higher activity in the anterior cingulate gyrus.

Subjects who admitted to feeling unwanted more often in everyday life showed more neural activity in response to an episode of social rejection. In some cases, simply looking at stimulus pictures activates nerves associated with bodily pain. For example, viewing paintings by Edward Hopper activated the anterior cingulate cortex and the anterior lobe of the brain. In addition, socially sensitive people, when watching a video of someone making a disapproving facial expression (a possible sign of social rejection), showed higher activity in the anterior cingulate gyrus.

Finally, separation or rejection are not the only triggers for the neural activity associated with pain. Other socially painful experiences, such as bereavement, also engage these neural pathways. In response to viewing images of a recently deceased mother or sister (along with photographs of unfamiliar women), the participants in the experiment showed increased activity in the anterior cingulate gyrus and anterior lobe. What's more, women who lost a baby due to induced abortion showed higher activity in the anterior cingulate cortex when viewing photos of smiling babies compared to those who gave birth to a healthy baby. So, various kinds of socially painful events, from rejection to loss, rely in part on those neural regions that play a direct role in bodily pain.

What's more, women who lost a baby due to induced abortion showed higher activity in the anterior cingulate cortex when viewing photos of smiling babies compared to those who gave birth to a healthy baby. So, various kinds of socially painful events, from rejection to loss, rely in part on those neural regions that play a direct role in bodily pain.

Within the intersection of physical and social pain, interesting results can be expected - for example, that people who are more sensitive to physical pain feel more acutely social pain, and vice versa. This is not a contrived hypothesis, it has been tested in several studies. The best evidence for this is found in patient records—people with chronic illness are much more concerned about their relationship with their partner than healthy people, and depressed people with high social sensitivity are more susceptible to pain than those who are in control.

The second result of the intersection of physical and social pain is that the factors of increase or decrease of one affect the other in the same measure. Thus, factors that are thought to reduce social pain (such as feeling socially supported) should also reduce physical pain, and those that reduce bodily pain (such as pain medication) also reduce social pain. We found evidence for both of these claims. To investigate whether social support reduces physical pain, we asked women to rate the discomfort of having a hot stimulus applied to their forearm while they performed various tasks. During one of the tasks they received social support (namely, holding the hand of a lover), during others they did not (for example, they held either the hand of a stranger or a soft ball). We found that the participants felt much less pain when holding their partner's hand than when they were with strangers. More interestingly, we found that participants felt much less pain when looking at pictures of their loved ones than when looking at pictures of strangers or objects. Obviously, even the thought of social support can reduce both physical and social pain.

Thus, factors that are thought to reduce social pain (such as feeling socially supported) should also reduce physical pain, and those that reduce bodily pain (such as pain medication) also reduce social pain. We found evidence for both of these claims. To investigate whether social support reduces physical pain, we asked women to rate the discomfort of having a hot stimulus applied to their forearm while they performed various tasks. During one of the tasks they received social support (namely, holding the hand of a lover), during others they did not (for example, they held either the hand of a stranger or a soft ball). We found that the participants felt much less pain when holding their partner's hand than when they were with strangers. More interestingly, we found that participants felt much less pain when looking at pictures of their loved ones than when looking at pictures of strangers or objects. Obviously, even the thought of social support can reduce both physical and social pain.

When I talk about this experiment, people often ask, "If this is true, then painkillers can reduce the suffering of social pain?" The question is asked as a joke, because it seems incredible, but in fact, the answer to it is yes, they can. To test this idea, we investigated whether the drug Tylenol could reduce feelings of social pain. In the first such study, participants took a normal dose of Tylenol or a placebo for three weeks. They were asked to rate their daily level of pain. Those who took Tylenol reported a reduction in pain from 9days to 21, while those who took placebo did not notice any changes. In another study, people took Tylenol or a placebo for three weeks and then played a virtual ball-passing game (in which they were socially excluded at the end). As the MRI scanner showed, those who took Tylenol had less neural activity in response to social isolation. These studies prove that, as surprising as it may seem, the Tylenol pain reliever also relieves social suffering.

Although painful, the anguish and pain of broken social relationships serve a valuable function in maintaining close social bonds. Since rejection hurts, people are motivated to avoid situations where rejection is possible.

Several other consequences of the intersection of physical and social pain have also been investigated. One phenomenon can be better understood in light of this intersection - rejection-induced aggression. For years, people have puzzled over evidence that socially alienated subjects are more likely to act aggressively towards others. In fact, this is close to the truth - one has only to recall the frequent news about the shooting at the school, which was arranged by students who were later described as outsiders. In fact, there is some merit to the idea that rejection provokes aggression; although, it would seem, given the importance of maintaining social ties, why in a situation of isolation a person is predisposed to aggression rather than to prosocial behavior? Wouldn't it make more sense if he tried to restore social ties? However, in light of the intersection of physical and social pain, an aggressive response to isolation is more justified. It is well known from research that animals, as a reaction to a painful stimulus, attack those who are nearby. This is probably such an adaptive function: when there is a threat of physical damage, they attack. If the social pain system does include parts of the physical system, an aggressive response to social rejection may be a by-product of the response to bodily pain—such an inadequate adaptive function in a social context.

It is well known from research that animals, as a reaction to a painful stimulus, attack those who are nearby. This is probably such an adaptive function: when there is a threat of physical damage, they attack. If the social pain system does include parts of the physical system, an aggressive response to social rejection may be a by-product of the response to bodily pain—such an inadequate adaptive function in a social context.

Another possible consequence of this intersection is the physiological stress that occurs in response to socially dangerous situations. It is well known that instances of physical threat elicit a physiological response (such as an increase in cortisol levels) to mobilize energy and resources. However, it has also been shown that socially dangerous situations - such as speaking in front of a strict or hostile audience - can lead to the same physiological reactions, also to an increase in cortisol levels. While it seems logical to mobilize energy in a physically dangerous situation, it is not clear why the body needs it when it can be negatively evaluated or rejected by others. However, if the threat of social rejection is interpreted by the brain in the same way as the threat of physical harm, physiological stress can be triggered in both situations.

However, if the threat of social rejection is interpreted by the brain in the same way as the threat of physical harm, physiological stress can be triggered in both situations.

One of the conclusions of the described discoveries is that separation or separation can undermine the body just as much as physical pain. Even if we take bodily pain more seriously and consider it a more legitimate cause for concern, the pain of social loss can be just as severe, as evidenced by the activation of the nervous system.

One might wonder why people have to bear this heavy burden of social and physical pain? Although painful, the anguish and heartache due to broken social relationships serve a valuable function, namely the maintenance of close social ties. Since rejection hurts, people are motivated to avoid situations where rejection is possible. Throughout evolutionary history, maintaining social ties has increased a person's chances of life and reproduction. The experience of social pain, although temporarily painful, is an evolutionary adaptation that promotes social cohesion and hence survival.