Attachment and substance abuse

Attachment and Substance Use Disorders—Theoretical Models, Empirical Evidence, and Implications for Treatment

1. Schindler A, Thomasius R, Sack PM, Gemeinhardt B, Küstner UJ, Eckert J. Attachment and substance use disorders: a review of the literature and a study in drug dependent adolescents. Attach Hum Dev (2005) 7(3):207–28. 10.1080/14616730500173918 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. West R, Brown J. Theory of Addiction. Oxford, UK: Wiley Addiction Press; (2013). 10.1002/9781118484890 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. Vol.1: attachment. New York: Basic Books; (1969). [Google Scholar]

4. Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. Vol.2: separation: anxiety and anger. New York: Basic Books; (1973). [Google Scholar]

5. Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. Vol.3: loss: sadness and depression. New York: Basic Books; (1980). [Google Scholar]

6. Bateman AW, Fonagy P. Borderline personality disorder. In: Bateman, AW, and Fonagy, P, editors. Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice.Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing; (2012). p. 273–88. [Google Scholar]

7. Holmes J. Exploring in security. London UK: Routledge; (2010). [Google Scholar]

8. Schindler A, Bröning S. A review on attachment and adolescent substance abuse: empirical evidence and implications for prevention and treatment. Subs Abuse J (2015), 36(3):304–13. 10.1080/08897077.2014.983586 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. Attachment representations in mothers, fathers, adolescents and clinical groups: a meta-analytic search for normative data. J Consult Clin Psychol (1996) 64/1:8–21. 10.1037/0022-006X.64.1.8 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment in adulthood. Guilford: New York; (2007). [Google Scholar]

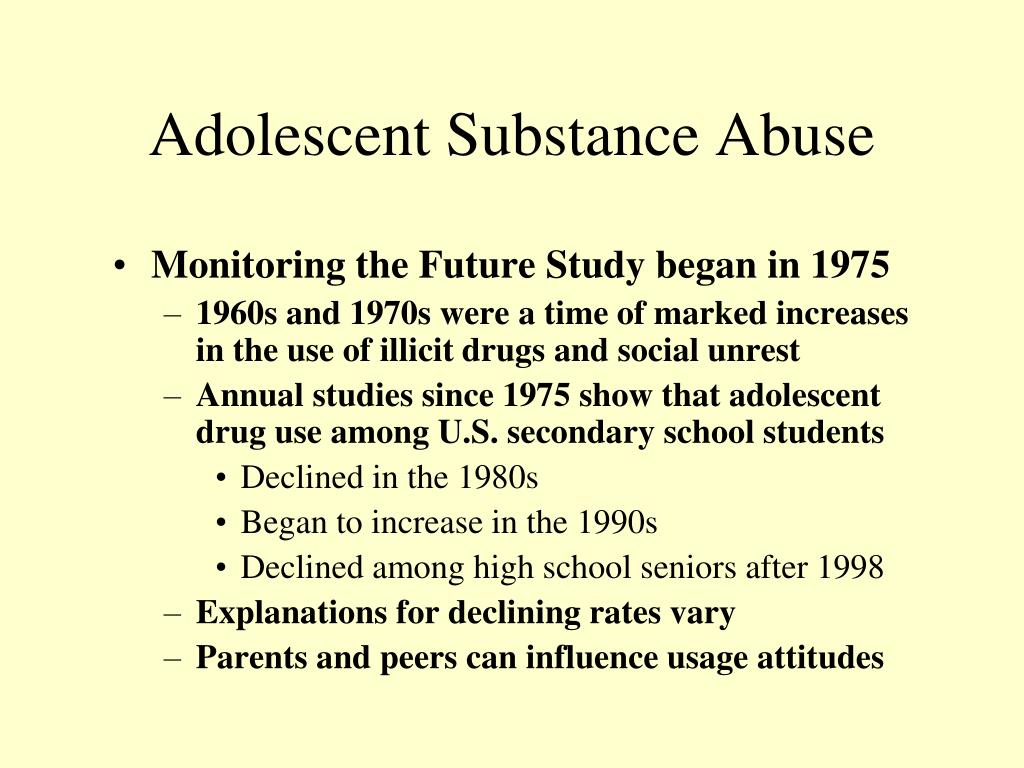

11. Petraitis J, Flay BR, Miller TQ, Torpy EJ, Greiner B. Illicit substance use among adolescents: a matrix of prospective predictors. Subst Use Misuse (1998) 33(13):2561–604. 10.3109/10826089809059341 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Subst Use Misuse (1998) 33(13):2561–604. 10.3109/10826089809059341 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applications. Harv Rev Psychiatry (1997) 4:231–44. 10.3109/10673229709030550 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Unterrainer HF, Hiebler-Ragger M, Rogen L, Kapfhammer HP. Sucht als Bindungsstörung. [Addiction as an attachment disorder]. Nervenarzt (2018) 89:1043–8. 10.1007/s00115-017-0462-4 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Iglesias EB, Fernández Del Río E, Calafat A, Fernadez-Hermida JR. Attachment and substance use in adolescence: a review of conceptual and methodological aspects. Adicciones (2014) 26(1):77–86. 10.20882/adicciones.137 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Julien RM, Advokat CD, Comaty J. A primer of drug action. New York: Worth Publishers; (2010). [Google Scholar]

16. Klein M. Psychosoziale Aspekte des Risikoverhaltens Jugendlicher im Umgang mit Suchtmitteln. Gesundheitswesen 2004 (2004) 66:56–60. 10.1055/s-2004-812769 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Gesundheitswesen 2004 (2004) 66:56–60. 10.1055/s-2004-812769 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Philips B, Kahn U, Bateman AW. Drug addiction. In: Bateman AW, Fonagy P, editors. Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing; (2012). p. 445–62. [Google Scholar]

18. Thorberg FA, Livers M. Attachment, fear of intimacy and differentiation of self among clients in substance disorder treatment facilities. Addict Behav (2006) 31(4):732–7. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.050 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Alvarez-Monjaras M, Mayes LC, Potenza MN, Rutherford HJ. A developmental model of addictions: integrating neurobiological and psychodynamic theories through the lens of attachment. Attach Hum Dev (2018) 18:1–22. 10.1080/14616734.2018.1498113 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Suchman NE, DeCoste CL. Substance abuse and addiction—implications for early relationships and interventions. Zero Three (2018) 38(5):17–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zero Three (2018) 38(5):17–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Lyons-Ruth K, Jacobvitz D. Attachment disorganization. In: Cassidy, J, and Shaver, PR, editors. Handbook of attachment. New York, NY: Guilford; (2008). p. 666–97. [Google Scholar]

22. Shaver PR, Mikulincer M. Attachment-related psychodynamics. Attach Hum Dev (2002) 4(2):133–61. 10.1080/14616730210154171 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. J Pers Soc Psychol (1991) 61(2):226–44. 10.1037//0022-3514.61.2.226 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

24. Ravitz P, Maunder R, Hunter J, Sthankiva B, Lancee W. Adult attachment measures: a 25-year review. J Psychosom Res (2010) 69(4):419–32. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.08.006 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Trigo JM, Martin-García E, Berrendero F, Robledo P, Maldonado R. The endogenous opioid system: a common substrate in drug addiction. Drug Alcohol Depend (2010) 108(3):183–94. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.10.011 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Drug Alcohol Depend (2010) 108(3):183–94. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.10.011 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Burkett JP, Young LJ. The behavioral, anatomical and pharmacological parallels between social attachment, love and addiction. Psychopharmacology (2012) 224(1):1–26. 10.1007/s00213-012-2794-x [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

27. Zellner MR, Watt DF, Solms M, Panksepp J. Affective neuroscientific and neuropsychoanalytic approaches to two intractable psychiatric problems: why depression feels so bad and what addicts really want. Neurosci Biobehav Rev (2011) 35(9):2000–8. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.01.003 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

28. Insel TR. Is social attachment an addictive disorder? Physiol Behav (2003) 79:351–7. 10.1016/S0031-9384(03)00148-3 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Panksepp J, Knutson B, Burgdorf J. The role of brain emotional systems in addictions: a neuro-evolutionary perspective and a newself-reportanimal model. Addiction (2002) 97(4):459–69. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00025.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Addiction (2002) 97(4):459–69. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00025.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

30. Nutt DJ, Lingford-Hughes A, Erritzoe D, Stokes PR. The dopamine theory of addiction: 40 years of highs and lows. Nat Rev Neurosci (2015) 16(5):305–12. 10.1038/nrn3939 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

31. Blum K, Thanos PK, Oscar-Berman M, Febo M, Baron D, Badgaiyan RD, et al. dopamine in the brain: hypothesizing surfeit or deficit links to reward and addiction. J Reward Defic Syndr (2015) 1(3):95–104. 10.17756/jrds.2015-016 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

32. Byng-Hall J. Family and couple therapy: toward greater security. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment. New York, NY: Guilford; (1999). p. 625–45. [Google Scholar]

33. Allen JP, Land D. Attachment in adolescence. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment. New York, NY: Guilford; (1999). p. 319–35. [Google Scholar]

34. Main M, Goldwyn R. Adult attachment scoring and classification system. Unpublished manuscript. Berkeley, CA: University of California at Berkeley; (1998). [Google Scholar]

Adult attachment scoring and classification system. Unpublished manuscript. Berkeley, CA: University of California at Berkeley; (1998). [Google Scholar]

35. Melnick S, Finger B, Hans S, Patrick M, Lyons-Ruth K. Hostile–helpless states of mind in the Adult Attachment Interview: a proposed additional AAI category with implications for identifying disorganized infant attachment in high-risk samples. In: Steele H, Steele M, editors. Clinical applications of the Adult Attachment Interview. New York, NY: Guilford; (2008). p. 399–423. [Google Scholar]

36. George C, West M. The development and preliminary validation of a new measure of adult attachment: the adult attachment projective. Attach Hum Dev (2001) 3(1):30–61. 10.1080/14616730010024771 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

37. Hazan C, Shaver P. Conceptualizing romantic love as an attachment process. J Pers Soc Psychol (1987) 52:511–24. 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

38. Collins NL, Read SJ. Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. J Personal Soc Psychol (1990) 58(4):644. 10.1037/0022-3514.58.4.644 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. J Personal Soc Psychol (1990) 58(4):644. 10.1037/0022-3514.58.4.644 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

39. Griffin DW, Bartholomew K. The metaphysics of measurement: the case of adult attachment. In: Bartholomew K, Perlman D, editors. Attachment processes in adulthood. Advances in personal relationships., vol. 5 London, UK: Jessica Kingsley; (1994). p. 17–52. [Google Scholar]

40. Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult romantic attachment: an integrative overview. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. New York NY:Guilford Press; (1998). p. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

41. Cooper ML, Shaver PR, Collins NL. Attachment styles, emotion regulation and adjustment in adolescence. J Pers Soc Psychol (1998) 74(5):1380–97. 10.1037//0022-3514.74.5.1380 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

42. Delvecchio E, Di Riso D, Lis A, Salcuni S. Adult attachment, social adjustment, and well-being in drug-addicted inpatients. Psychol. Rep. (2016) 118(2):587–607. 10.1177/0033294116639181 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Adult attachment, social adjustment, and well-being in drug-addicted inpatients. Psychol. Rep. (2016) 118(2):587–607. 10.1177/0033294116639181 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

43. Amann U. Bindungsrepräsentationen suchmittelabhängiger Jugendlicher und ihrer Eltern [Attachment representations in drug addicted youths and their parents]. Norderstedt, Germany: GRIN; (2009). [Google Scholar]

44. Branstetter SA, Furman W, Cottrell L. The influence of representations of attachment, maternal–adolescent relationship quality, and maternal monitoring on adolescent substance use: a two-year longitudinal examination. Child. Dev. (2009) 80(5):1448–62. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01344.x [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

45. Finger B. Exploring the intergenerational transmission of Attachment disorganization. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago IL; (2006). [Google Scholar]

46. Caspers KM, Cadoret RJ, Langbehn D, Yucuis R, Troutman B. Contributions of attachment style and perceived social support to lifetime use of illicit substances. Addict Behav (2005) 30(5):1007–11. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.09.001 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Addict Behav (2005) 30(5):1007–11. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.09.001 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

47. Caspers KM, Yucuis R, Troutman B, Spinks R. Attachment as an organizer of behavior: implications for substance abuse problems and willingness to seek treatment. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy (2006) 1(32). 10.1186/1747-597X-1-32 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

48. Riggs SA, Jacobvitz D. Expectant parents’ representations of early attachment relationships: associations with mental health and family history. J Consult Clin Psychol (2002) 70(1):195–204. 10.1037//0022-006X.70.1.195 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

49. Fonagy P, Leigh T, Steele M, Steele H, Kennedy R, Mattoon G, et al. The relation of attachment status, psychiatric classification and response to psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol (1996) 64(1):22–31. 10.1037/0022-006X.64.1.22 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

50. Rosenstein DS, Horowitz HA. Adolescent attachment and psychopathology. J. Consult Clin Psychol (1996) 642:244–53. 10.1037/0022-006X.64.2.244 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J. Consult Clin Psychol (1996) 642:244–53. 10.1037/0022-006X.64.2.244 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

51. Allen JP, Hauser ST, Borman-Spurell E. Attachment theory as a framework for understanding sequelae of severe adolescent psychopathology: an 11-year follow-up study. J Consult Clin Psychol (1996) 64(2):254–63. 10.1037//0022-006X.64.2.254 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

52. Finzi-Dottan R, Cohen O, Iwaniec D, Sapir Y, Weizman A. The drug-user husband and his wife: attachment styles, family cohesion and adaptability. Subst Use Misuse (2003) 38(2):271–92. 10.1081/JA-120017249 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

53. Mickelson KD, Kessler RC, Shaver PR. Adult attachment in a nationally representative sample. J Pers Soc Psychol (1997) 73(5):1092–106. 10.1037//0022-3514.73.5.1092 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

54. Brennan KA, Shaver PR. Dimensions of adult attachment, affect regulation, and romantic relationship functioning. Pers Soc Psychol Bull (1995) 21:267–83. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

55. Senchak M, Leonard KE. Attachment styles and marital adjustment among newlywed couples. J Soc Pers Relat (1992) 9:61–4. 10.1177/0265407592091003 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

56. Durjava L. Relationship between recalled parental bonding, adult attachment patterns and severity of heroin addiction. MOJ Addict Med Ther (2018) 54:168–74. 10.15406/mojamt.2018.05.00114 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

57. Unterrainer HF, Hiebler-Ragger M, Koschutnig K, Fuchshuber J, Tscheschner S, Url M, et al. Addiction as an attachment disorder—white matter impairment is linked to increased negative affective states in polydrug use. Fron (2017) 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00208 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Mortazavi Z, Sohrabi F, Hatami HR. Comparison of attachment styles and emotional maturity between opiate addicts and non-addicts. Ann Biol Res (2012) 31:409–14. [Google Scholar]

59. Shin SE, Kim NS, Jang EY. Comparison of problematic internet and alcohol use and attachment styles among industrial workers in Korea. Cyberpsychol. Behav Soc Netw (2011) 14(11):665–72. 10.1089/cyber.2010.0470 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Cyberpsychol. Behav Soc Netw (2011) 14(11):665–72. 10.1089/cyber.2010.0470 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

60. Kassel JD, Wardle M, Roberts JE. Adult attachment security and college student substance use. Addict Behav (2007) 32(6):1164–76. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.08.005 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

61. Vaz-Serra A, Canavarro MC, Ramalheira C. The importance of family context in alcoholism. Alcohol Alcohol (1998) 331:37–41. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a008345 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

62. Gidhagen Y, Holmqvist R, Philips B. Attachment style among outpatients with substance use disorders in psychological treatment. Psychol Psychother (2018) 91(4):490–508. 10.1111/papt.12172 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

63. Le TL, Levitan RD, Mann RE, Maunder RG. Childhood adversity and hazardous drinking: the mediating role of attachment insecurity. Subst Use Misuse (2018) 3:53(8):1387–98. 10.1080/10826084.2017.1409764 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

64. Schindler A, Sack PM. Comorbid substance use disorders are related to avoidant attachment in individuals with borderline disorders. Journal of Mental and Nervous Diseases (2015) 203:820–6. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000377 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Schindler A, Sack PM. Comorbid substance use disorders are related to avoidant attachment in individuals with borderline disorders. Journal of Mental and Nervous Diseases (2015) 203:820–6. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000377 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

65. Wedekind D, Bandelow B, Heitmann S, Havemann-Reinecke U, Engel KR, Huether G. Attachment style, anxiety coping, and personality-styles in withdrawn alcohol addicted inpatients. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy (2013) 8:1. 10.1186/1747-597X-8-1 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

66. Jenkins CO, Tonigan JS. Attachment avoidance and anxiety as predictors of 12-step group engagement. J Stud Alcohol Drugs (2011) 72(5):854–63. 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.854 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

67. Harnic D, Digiacomantonio V, Innamorati M, Mazza M, Di Marzo S, Sacripanti F, et al. Temperament and attachment in alcohol addicted patients of type 1 and 2. Riv Psichiatr (2010) 45(5):311–9. 101708/ 530.6319 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

101708/ 530.6319 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Molnar DS, Sadava SW, DeCourville NH, Perrier CP. Attachment, motivations, and alcohol: testing a dual-path model of high-risk drinking and adverse consequences in transitional clinical and student samples. Can J Behav (2010) 42(1):1–13. 10.1037/a0016759 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

69. DeRick A, Vanheule S. Attachment styles in alcoholic inpatients. Addict Res (2007) 13:101–8. 10.1159/000097940 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

70. DeRick A, Vanheule S, Verhaeghe P. Alcohol addiction and the attachment system: an empirical study of attachment style, alexithymia, and psychiatric disorders in alcoholic inpatients. Subst Use Misuse (2009) 44(1):99–104. 10.1080/10826080802525744 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

71. Schindler A, Thomasius R, Petersen K, Sack PM. Heroin as an attachment substitute? Attach. Hum. Dev. (2009) 11:307–30. 10.1080/14616730902815009 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

72. Doumas DM, Blasey CM, Mitchell S. Adult attachment, emotional distress, and interpersonal problems in alcohol and drug dependency treatment. Alcohol Treat Q (2006) 24(4):41–54. 10.1300/J020v24n04_04 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Adult attachment, emotional distress, and interpersonal problems in alcohol and drug dependency treatment. Alcohol Treat Q (2006) 24(4):41–54. 10.1300/J020v24n04_04 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

73. Vungkhanching M, Sher KJ, Jackson KM, Parra GR. Relation of attachment style to family history of alcoholism and alcohol use disorders in early adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend (2004) 75(1):47–53. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.01.013 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

74. McNally AM, Palfai TP, Levine RV, Moore BM. Attachment dimensions and drinking-related problems among young adults: the mediational role of coping motives. Addict Behav (2003) 28(6):1115–27. 10.1016/S0306-4603(02)00224-1 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

75. Zeid D, Carter J, Lindberg M. Comparisons of alcohol and drug dependence in terms of attachments and clinical issues. Subst Use Misuse (2017) 53(1):1–8. 10.1080/10826084.2017.1319865 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

76. Zhai ZW, Kirisci L, Tarter RE, Ridenour TA. Psychological dysregulation during adolescence mediates the association of parent–child attachment in childhood and substance use disorder in adulthood. Am. J Drug Alcohol Abuse (2014) 40(1):67–74. 10.3109/00952990.2013.848876 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Psychological dysregulation during adolescence mediates the association of parent–child attachment in childhood and substance use disorder in adulthood. Am. J Drug Alcohol Abuse (2014) 40(1):67–74. 10.3109/00952990.2013.848876 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

77. Danielsson AK, Romelsjoe A, Tengstroem A. Heavy episodic drinking in early adolescence: gender specific risk and protective factors. Subst Use Misuse (2011) 46(5):633–43. 10.3109/10826084.2010.528120 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

78. Jordan S, Sack PM. Schutz- und Risikofaktoren [Protective factors and risk factors]. In: Thomasius R, Schulte-Markwort M, Küstner UJ, Riedesser P, editors. Suchtstoerungen im Kindes- und Jugendalter–Das Handbuch: Grundlagen und Praxis. Stuttgart, Germany: Schattauer; (2009). p. 127–38. [Google Scholar]

79. Leonard KE, Eiden RD. Marital and family processes in the context of alcohol use and alcohol disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol (2007) 3:285–310. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091424 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091424 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

80. Fairbairn CE, Briley DA, Kang D, Fraley RC, Hankin BL, Ariss T. A meta-analysis of longitudinal associations between substance use and interpersonal attachment security. Psychol Bull (2018) 144(5):532–55. 10.1037/bul0000141 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

81. Schäfer I. Traumatisierung und Sucht [Trauma and addiction]. In: Seidler G, Freyberger H, Maercker A. editors. Handbuch psychotraumatologie. Stuttgart, Germany: Klett-Cotta; (2011). p. 255–63. [Google Scholar]

82. Fowler JC, Groat M, Ulanday M. Attachment style and treatment completion among psychiatric inpatients with substance use disorders. Am J Addict (2013) 22(1):14–7. 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.00318.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

83. Rowe CL. Family therapy for drug abuse: review and updates 2003-2010. J Marital Fam Ther (2012) 38(1):59–81. 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011. 00280.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

00280.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

84. von Sydow K, Retzlaff R, Beher S, Haun ML, Schweitzer J. (2013). The efficacy of systemic therapy for childhood and adolescent externalizing disorders: A Systematic Review of 47 RCT. Fam Process 52(4):576–618. 10.1111/famp.12047 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

85. Diamond GM, Diamond GS, Hogue A. Attachment-based family therapy: adherence and differentiation. J Marital Fam Ther (2007) 33:177–91. 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2007.00015.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

86. Asen E, Fonagy P. Mentalization-based family therapy. In: Bateman AW, Fonagy P, editors. Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing; (2012). p. 107–28. [Google Scholar]

87. Schindler A, Thomasius R, Sack PM, Gemeinhardt B, Küstner U. Insecure family bases and adolescent drug abuse: a new approach to family patterns of attachment. Attach Hum Dev (2007) 9(2):111–26. 10.1080/14616730701349689 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

88. Pedersen CA. Oxytocin, tolerance and the dark side of addiction. Int Rev Neurobiol (2017) 136:239–74. 10.1016/bs.irn.2017.08.003 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Pedersen CA. Oxytocin, tolerance and the dark side of addiction. Int Rev Neurobiol (2017) 136:239–74. 10.1016/bs.irn.2017.08.003 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

How Attachment Style can Impact Addiction

Skip to contentMedicare Is Now Accepted At Most Locations

Where change begins. 844.341.4040February 3, 2020

Those who think addiction is a choice or merely a behavioral defect may be unaware of how early development can significantly influence someone’s susceptibility to addiction, or other behavior health issues, later on in life. Attachment styles are the different kinds of emotional bonds infants form with their caregivers from the time they are born. The interactions they have with their parents during these earliest stages, as well as later into adolescence and early adulthood, all affect psychological, physical and emotional behaviors. The way people learn to connect to their caregivers also gives them a preview of other relationships they will have in the future, along with mechanisms to deal with positive and negative aspects of life.

People’s perceptions of emotional intimacy, communication style, response to conflict and expectations of relationships are dependent on their attachment style experience in early life. Attachment styles all have three primary dimensions with which they can be characterized by:

Dependence/Avoidance: How people feel having others dependent on them or depending on others.

Anxiety: How worried people are about their partner or others abandoning or rejecting them.

Closeness: How comfortable someone is feeling emotionally connected and close to others.

These factors all differ when looking at the different attachment styles below:

- Secure: Low avoidance, low anxiety. Autonomous yet comfortable with intimacy and not concerned with abandonment or rejection. Has the ability to depend on others and have others rely on them. Trusting, empathetic, forgiving, and tolerant of differences.

Open communication style while being able to pick up on nonverbal context clues. Parents with this type of attachment are sensitive, warm, and in-tune with their child’s emotions and needs.

Open communication style while being able to pick up on nonverbal context clues. Parents with this type of attachment are sensitive, warm, and in-tune with their child’s emotions and needs. - Avoidant: High avoidance, low anxiety. Dismissive and uncomfortable with intimacy. Emotionally distant and prioritizes freedom and independence over togetherness. Aloof communication style with a focus on logic and intelligence without touching on emotions. Stoic, self-sufficient, but will hold off on confronting conflict until they erupt with anger. Parents of this type are emotionally unavailable and often disengaged from their child’s cues, causing them to adopt avoidant attachments as well.

- Anxious: Low avoidance, high anxiety. Preoccupied with the desire to be close with others or in a relationship but too anxious and insecure. Often needy and concerned with rejection and abandonment. Holds grudges and is very sensitive to a partner’s mood or actions.

Highly emotional, combative, and has few boundaries. Communication style is deflective and has a hard time accepting blame. Parents with this style are inconsistent with the attention they give their children, causing them to feel anxiously attached, unsure of what the day’s mood will bring.

Highly emotional, combative, and has few boundaries. Communication style is deflective and has a hard time accepting blame. Parents with this style are inconsistent with the attention they give their children, causing them to feel anxiously attached, unsure of what the day’s mood will bring. - Disorganized: High avoidance, high anxiety. Uncomfortable with intimacy and untrusting of others in a relationship. Unresolved emotions make them frightened by past experiences and traumas that have not been mourned or dealt with. Difficulty with emotional intimacy and can be argumentative and often abusive to partners or loved ones. Antisocial tendencies and can be aggressive, unremorseful, and often suffers from depression and PTSD. Parents with this type of attachment often mistreat their children, withhold attention and love, and lead them to have a disorganized attachment to others, often making them susceptible to becoming the victim of abusers.

It’s important to note that most adults have a combination of traits from various types; rarely do people fall precisely into one style exactly. These classifications are passed down from generation to generation and are the way that children learn how to connect with their caregivers, others, and eventually their own children.

These classifications are passed down from generation to generation and are the way that children learn how to connect with their caregivers, others, and eventually their own children.

Healthy attachments are essential for the development of many key characteristics of someone’s personality, like having empathy, resilience, adaptability and the ability to trust others. It impacts a person’s ability to manage stress and emotions, as well as communicate both verbally and non-verbally and maintain functioning inter- and intrapersonal skills. The key factor that relates to addiction is problems with stress management. Security attachment helps people manage independence and take control of their lives and their environment.

Insecure attachment styles can lead people to have abnormal responses or unhealthy coping mechanisms to deal with stress or conditions like depression, anxiety and PTSD. There are long-term consequences that correlate with these attachment styles that can include risky behavior, substance use, homelessness, anger management issues and problems with interpersonal relationships. The issues that come along with these situations and behaviors add to the inability to handle stress, usually pushing the person to seek out some form of release or pleasure in other ways.

The issues that come along with these situations and behaviors add to the inability to handle stress, usually pushing the person to seek out some form of release or pleasure in other ways.

Research has shown that those with insecure attachment who greatly fear intimacy frequently use substances as an escape technique rather than facing their emotional distress, especially avoidant types. Not having any close friends or partners can lead to isolation and dysfunctional view of self. Those who aren’t entirely avoidant but feel distrust in romantic relationships also show an increased rate of drug use, as well as those who have attachment anxiety. Overall, each of these insecure attachment styles ultimately lead to heightened stress-motivated behaviors that have negative consequences. These results add to the multidimensional core of the addiction connection because avoidant types are more likely to turn to drugs or alcohol rather than confide in a friend or loved one or communicate their concerns in a romantic relationship.

If someone with substance use disorder is looking to treat their illness effectively, it’s helpful to become aware of attachment styles and reflect on their upbringing. Successful recovery can be achieved when underlying trauma like problematic family affairs are dealt with as they may have lead a patient to substance use as a coping mechanism. Cognitive-behavioral therapy can help rewire the brain to overcome the adverse effects that unhealthy attachment styles have impressed into the brain’s pathways and teach patients how to deal with their feelings more productively.

Those who grow up with a healthy and secure attachment style with their caregivers are often very lucky but also somewhat rare. With addiction becoming more prevalent across the country and through all walks of life, it’s become evident that there are more underlying factors that can lead people to misuse substances. Being mindful of these risk factors that can predispose people to substance use disorder can aid in addiction recovery and also the upbringing of future generations.

Learn More About Treatment at BAART

Reach out to us today to get more details about BAART Programs and medication-assisted therapy (MAT) for opioid addiction at any of our centers near you.

SHARE THIS POST

POSTS YOU MAY LIKE:

OPIOID ADDICTION TREATMENT:

SHARE THIS POST

844.341.4040

90,000 HistoryRemote training

Professional retraining

Professional training

Classes

Teachers Teachers, educators

9000 palliative care

June 19 — Day of the Medical Worker

Congratulation of the Governor of the Rostov Region on the Day of the Medical Worker

June 12 - Day of Russia

June 1 - International Children's Day

May 28 - International Women's Health Day

workers with secondary medical and pharmaceutical education. In accordance with the ever-growing requirements of practical healthcare to the level and quality of training of specialists, the material and technical base and educational and methodological support of the school developed dynamically.

In accordance with the ever-growing requirements of practical healthcare to the level and quality of training of specialists, the material and technical base and educational and methodological support of the school developed dynamically.

In 2004, the ROUPK was renamed into the state educational institution of additional professional education "Center for Advanced Training of Specialists with Secondary Medical and Pharmaceutical Education" of the Rostov Region, and in 2011 - into the state budgetary educational institution of additional professional education of the Rostov Region "Center for Advanced Training of Specialists with secondary medical and pharmaceutical education”

Currently, the center is a large educational institution in the South of Russia, which has an educational building with an area of 1571 sq.m. and strong material and technical base.

The head of the advanced training center is the Honored Doctor of the Russian Federation Dimitrova L.V.

The purpose of the center is to provide educational services for advanced training at a modern and high quality level. Over 8,000 specialists in 32 specialties study at the center every year.

Over 8,000 specialists in 32 specialties study at the center every year.

Created conditions for the provision of educational services:

- advanced material and technical base,

- team with high creative potential,

- modern pedagogical and health-saving technologies in education.

The educational process is being actively modernized:

- A unified information environment of the center has been formed

- Transition to multimedia technology 9 completed0057

| Multimedia equipment for the lesson (using an interactive whiteboard, document camera, etc.) | In the emergency medicine class, students work with the training computer program for cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

| Computational final testing of students is carried out | Multimedia presentations are in the arsenal of every teacher. Example: developments of Garlikov N.N. Example: developments of Garlikov N.N. |

The achievement of our center is the introduction of the latest developments in the educational process:

- In the field of safety of the professional environment of medical workers

| Operation with needle destructor and portable autoclave | New in laboratory diagnostics (work with express analyzers) |

- In training students in the section "Ambulance and emergency care"

| Use of vacuum splints and heart massage with cardio pump | Ambulance paramedics performing ventilation after tracheal intubation using a laryngoscope |

- Nursing Technology

| Mastering the technology of blood sampling using vacuum systems | Peripheral Catheter Training |

Our contribution to the implementation of the Priority National Project "Health" goes in the following directions:

- Formation of a healthy lifestyle

In order to achieve the best results in this area, a study room "Health" was opened

| Demonstration of hardware and software complex "Health-Express" | Tobacco control work organized |

Competitions are held among students for the best creative work to promote a healthy lifestyle

| The winner of the competition - the film "Radiant Smile" - the series "Dental Care for the Population" |

- Improving the provision of medical care to victims of road accidents

113 specialists trained to provide assistance to victims on the M-4 Federal Highway

- Improving medical care for patients with cardiovascular diseases

422 specialists trained to work in new vascular centers for minimally invasive surgery and cardiac surgery departments

Particular attention is paid to cooperation with the International Committee of the Red Cross in the North Caucasus

74 medical workers have studied for five years of cooperation. The activities of the center in this direction were highly appreciated by the head of the International Committee of the Red Cross in the North Caucasus, Michel Masson.

The activities of the center in this direction were highly appreciated by the head of the International Committee of the Red Cross in the North Caucasus, Michel Masson.

The Center for Advanced Studies has ample opportunities to provide high-quality educational services for training specialists with secondary medical and pharmaceutical education in accordance with the ever-growing requirements of practical healthcare.

Development and support of the site - JSC "Regional intersectoral center of information and technology"

What is addiction and how does it differ from dependence?

The word "addiction" is used when they are ready to say "addiction", but they stumble for literally a second before calling someone addict out loud. It is used to distinguish between a person who is addicted to other people and a person who abuses alcohol. In fact, the meaning of this word is much more complex and deeper.

We tell you what it means and why it applies not only to alcoholics and smokers.

We tell you what it means and why it applies not only to alcoholics and smokers. What was before - dependence or addiction?

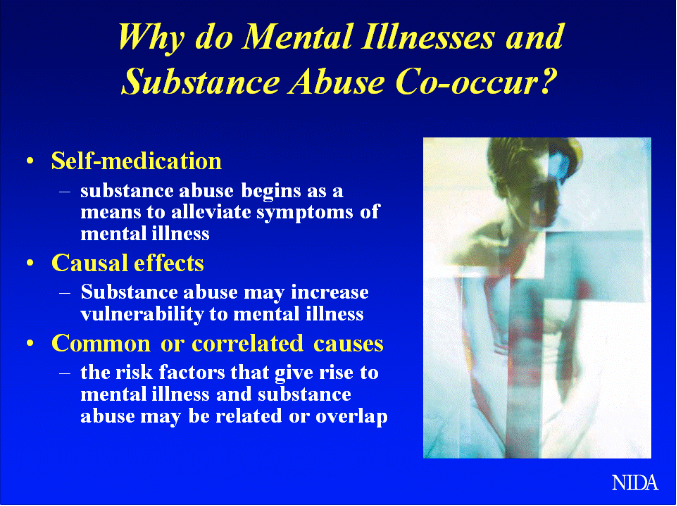

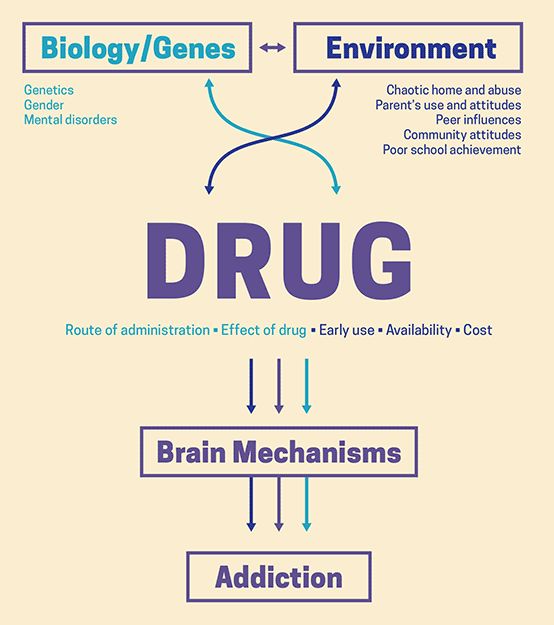

At first, in the medical environment, as a term, there was only "addiction" and its other synonym - "drug addiction". For quite a long time, until enough research was done in the field of addictive and deviant behavior, any abuse was called addiction. However, as we study how human behavior changes with the formation of addiction at the physiological level, addiction has taken a separate niche in this process.

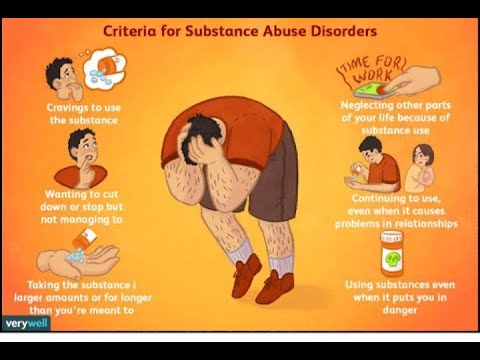

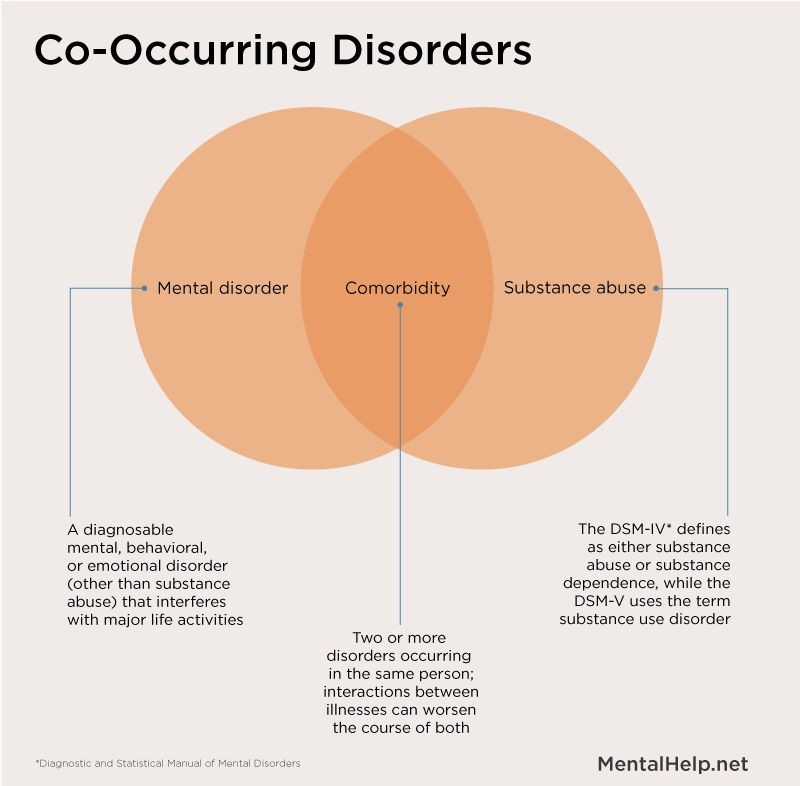

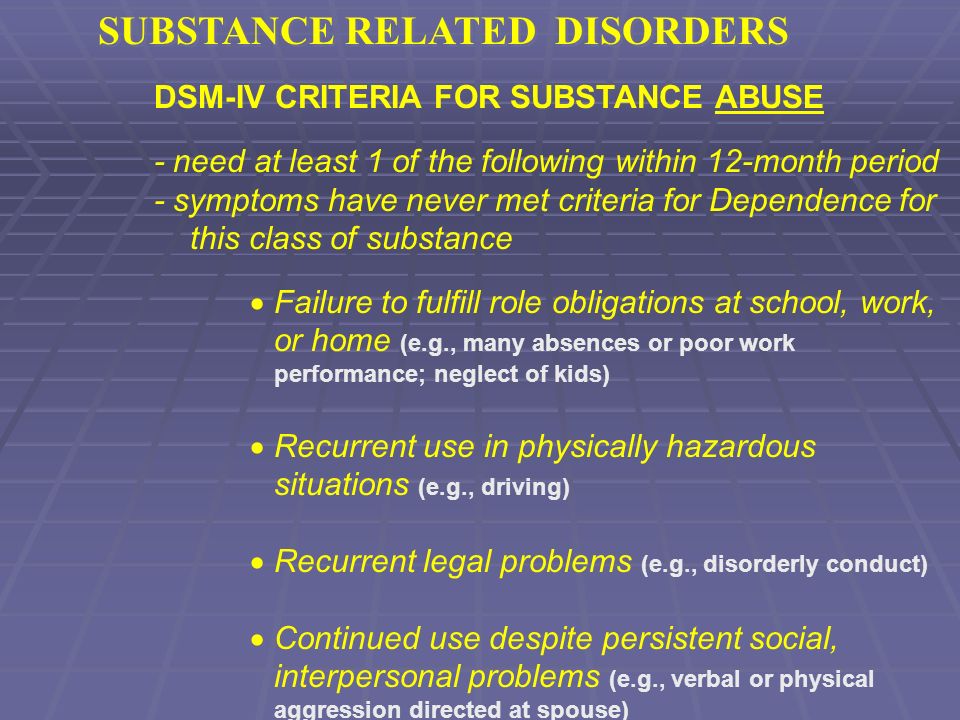

Addiction is a behavioral pattern that includes the abuse of psychoactive or dangerous substances (including nicotine, alcohol), as well as certain practices that are addictive (for example, watching pornography, and gambling or video games). However, at the stage of addiction, only psychological addiction is formed.

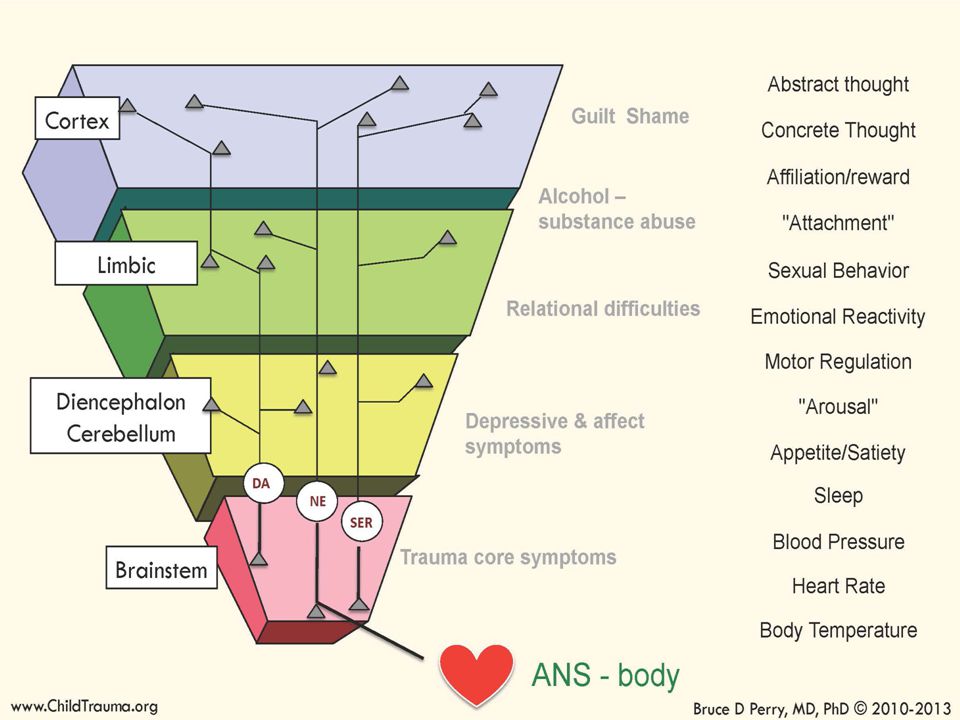

The subsequent physiological dependence, the construction of new neural connections and changes in the functioning of the limbic system of the brain are already considered the consequences of addiction.

How to look at life from the bright side and successfully deal with stress? Learn this in the Antifragility course.

The difference between addiction and dependence

Addiction usually begins before direct physiological dependence. However, it is rare to encounter a situation where there is a rigid separation of the episode, when a person loses psychological attachment, but retains a physical need to satisfy his need. But addiction without addiction can exist.

Addiction is formed by quickly getting a feeling of euphoria, security, or simply pleasure that a substance or repeated practice gives. It is strengthened due to several factors:

-

Additional rituals that the addict associates with the use or repetition of his addictive practices. For example, this connection is tracked in the phrases “I can’t wake up without a cup of espresso,” “I can’t survive a deadline without a smoke break,” or “Therapeutic shopping helps relieve stress.” All of these rituals include a system of motivation and reward that normally starts working (as the evolutionary mechanism intended) when a person escapes danger, finds food, a source of warmth, or a partner with whom it is not scary to raise offspring.

The constant repetition of these rituals already turns addiction into a physiological dependence.

The constant repetition of these rituals already turns addiction into a physiological dependence. -

Support group. They are the same community (if we are talking about gambling addiction) or drinking buddies (if we are talking about more destructive practices). Belonging to a group makes a person more confident, gives a sense of security.

-

Acquired habits. For example, a person could learn them in childhood if, in front of his eyes, his parents nervously smoked, drank, or elevated addictive behavior to the level of tradition or norm.

Actual articles and collections in your smartphone. Subscribe to our Telegram channel and receive all the materials published on our website.

How to get rid of addiction?

Even if a strong physiological dependence has not yet formed, it can be difficult to give up an addiction or practice. In many ways, success depends on the individual characteristics of the person, but here are some tips that can help.