Personality disorder lack of empathy

Empathy and Personality Disorders | HealthyPlace

One thing that separates narcissists and psychopaths from the rest of society is their apparent lack of empathy. Read about empathy and personality disorders.

What is Empathy?

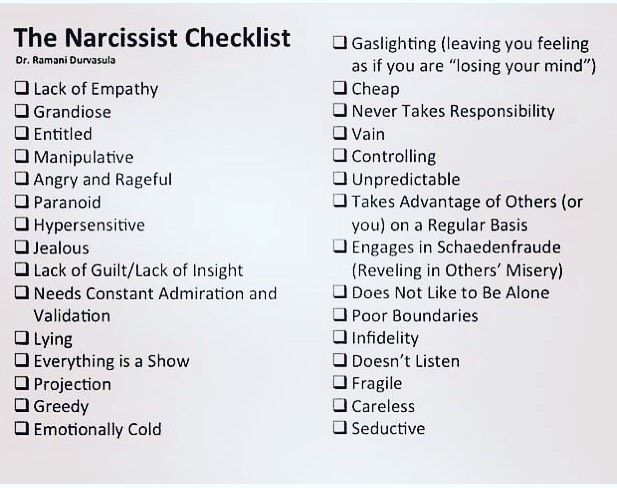

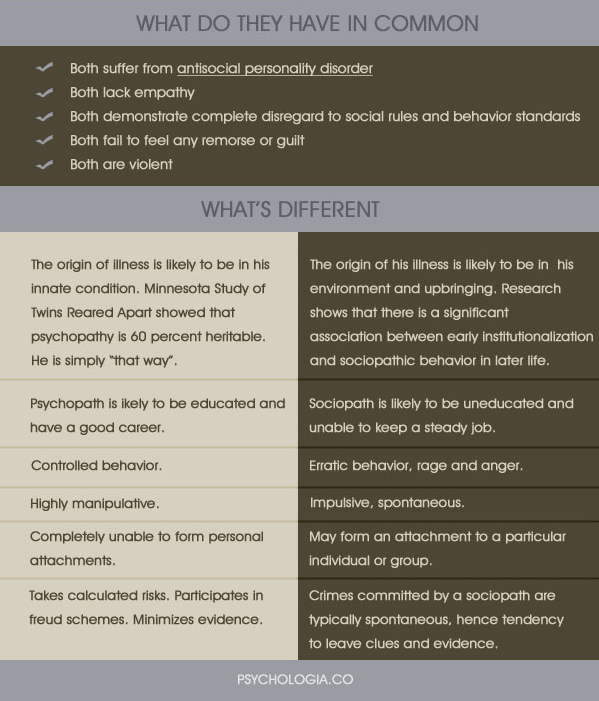

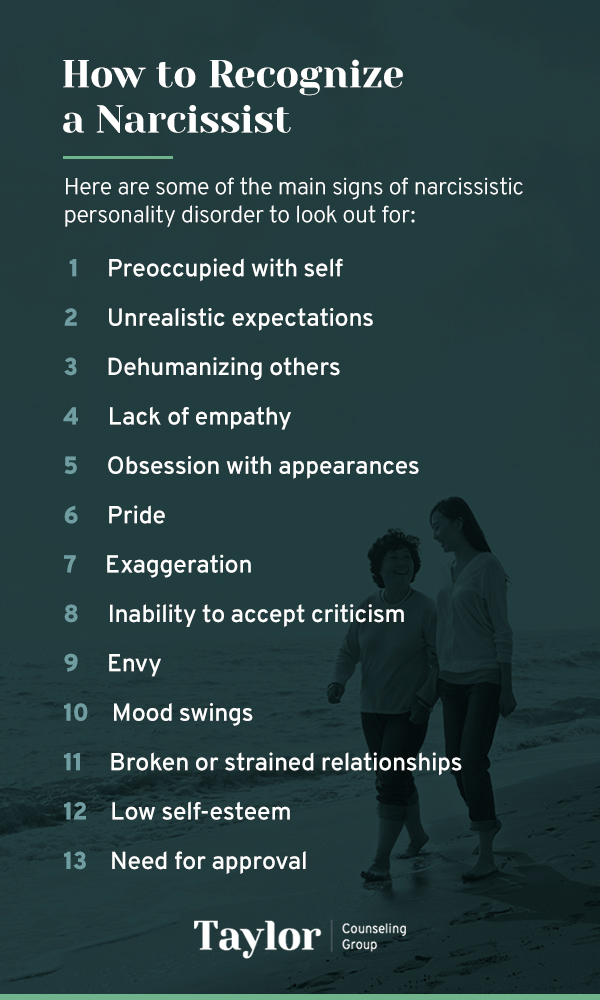

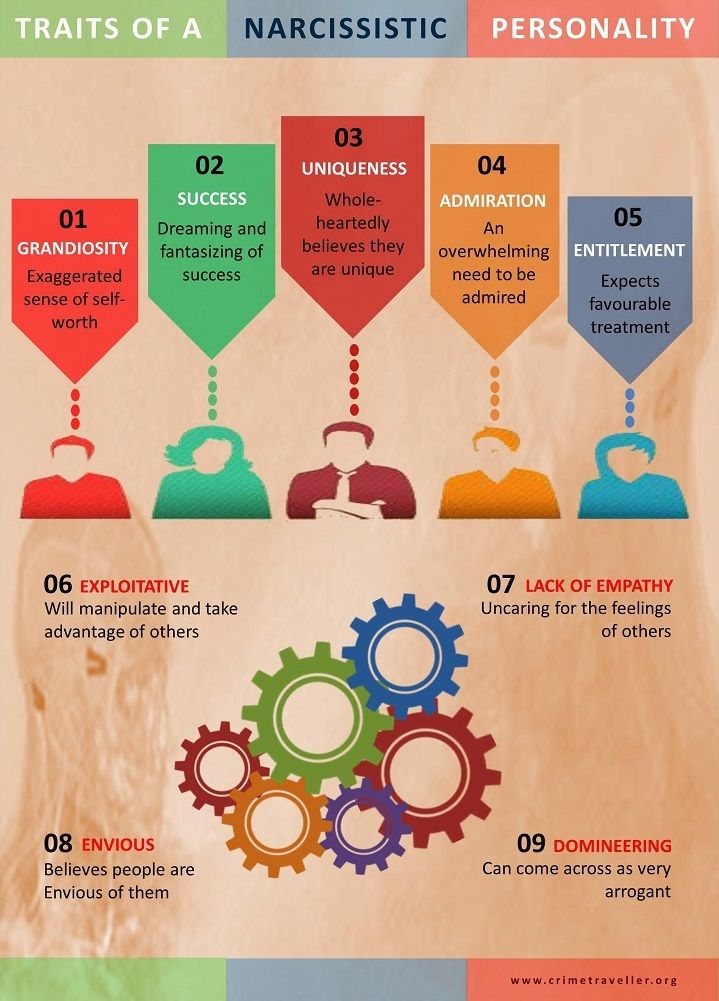

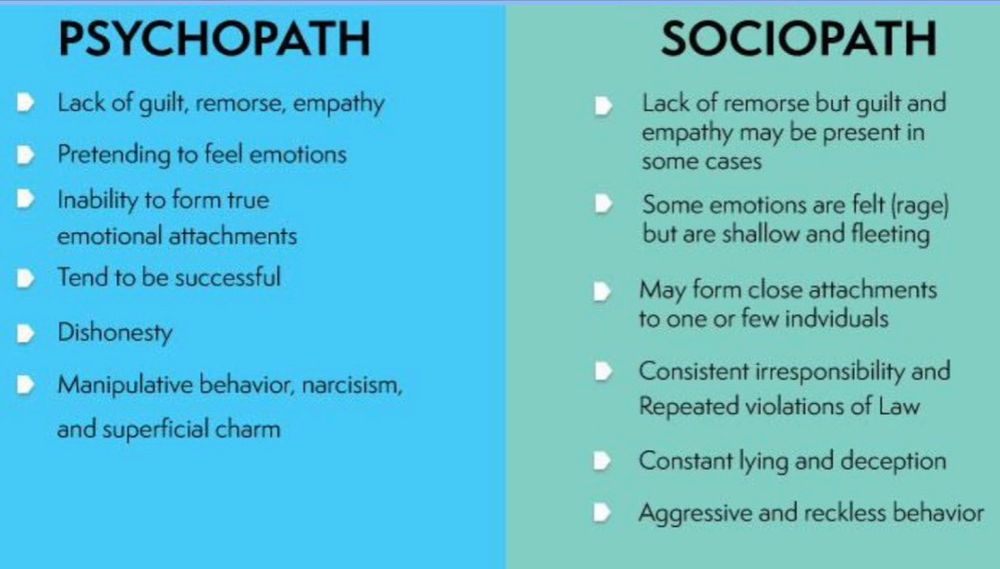

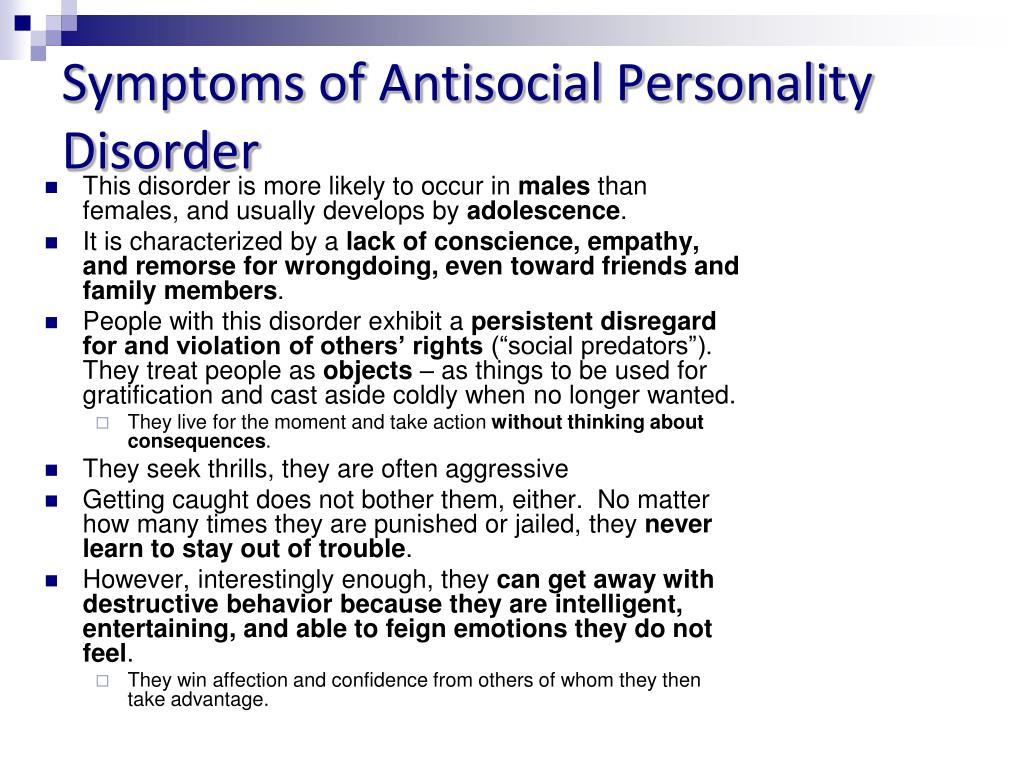

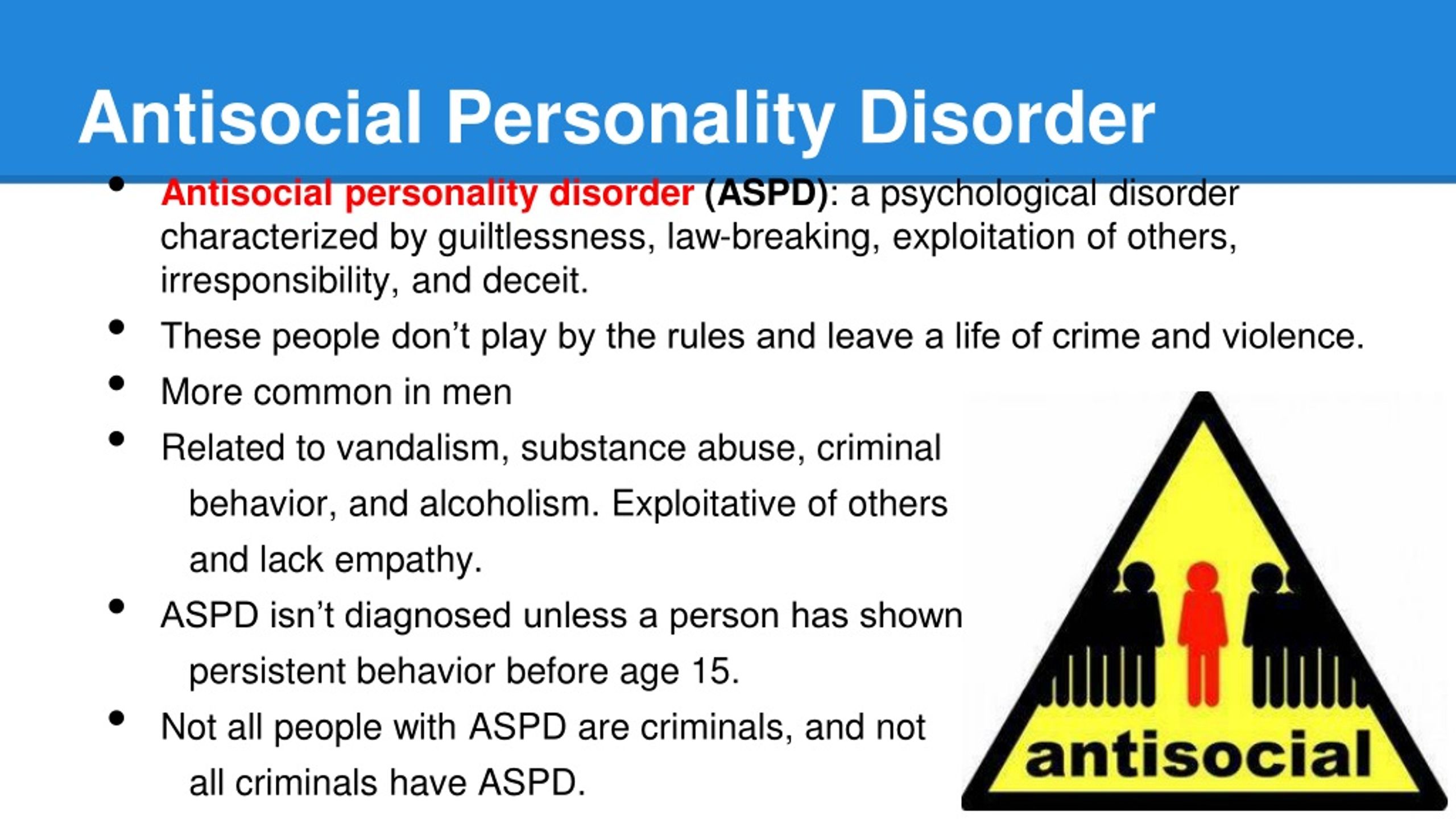

Normal people use a variety of abstract concepts and psychological constructs to relate to other persons. Emotions are such modes of inter-relatedness. Narcissists and psychopaths are different. Their "equipment" is lacking. They understand only one language: self-interest. Their inner dialog and private language revolve around the constant measurement of utility. They regard others as mere objects, instruments of gratification, and representations of functions.

This deficiency renders the narcissist and psychopath rigid and socially dysfunctional. They don't bond - they become dependent (on narcissistic supply, on drugs, on adrenaline rushes). They seek pleasure by manipulating their dearest and nearest or even by destroying them, the way a child interacts with his toys.

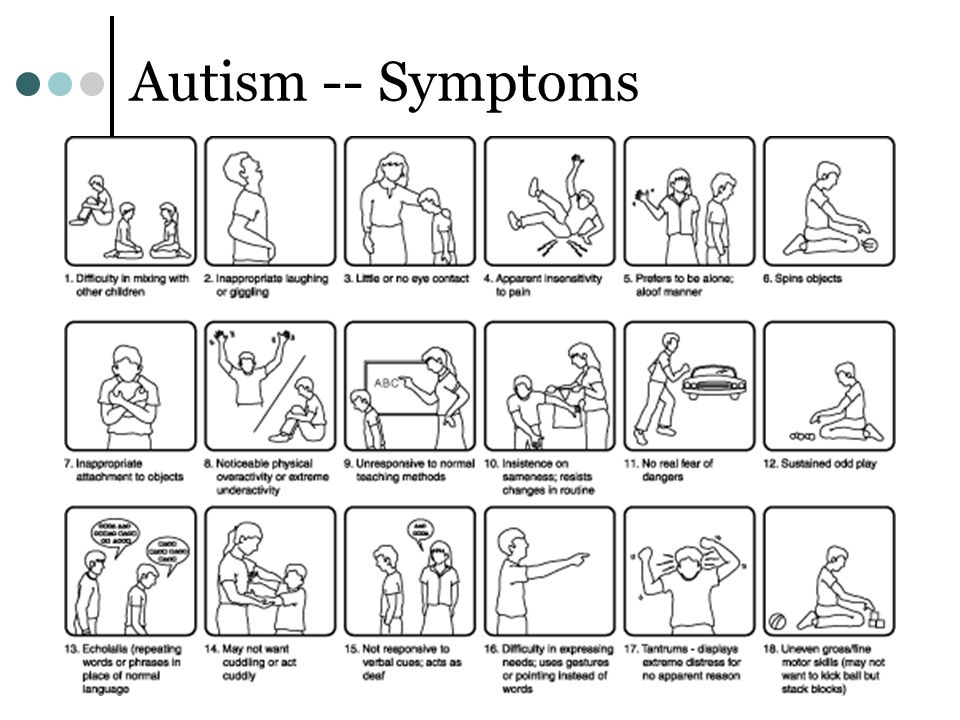

Like autists, they fail to grasp cues: their interlocutor's body language, the subtleties of speech, or social etiquette.

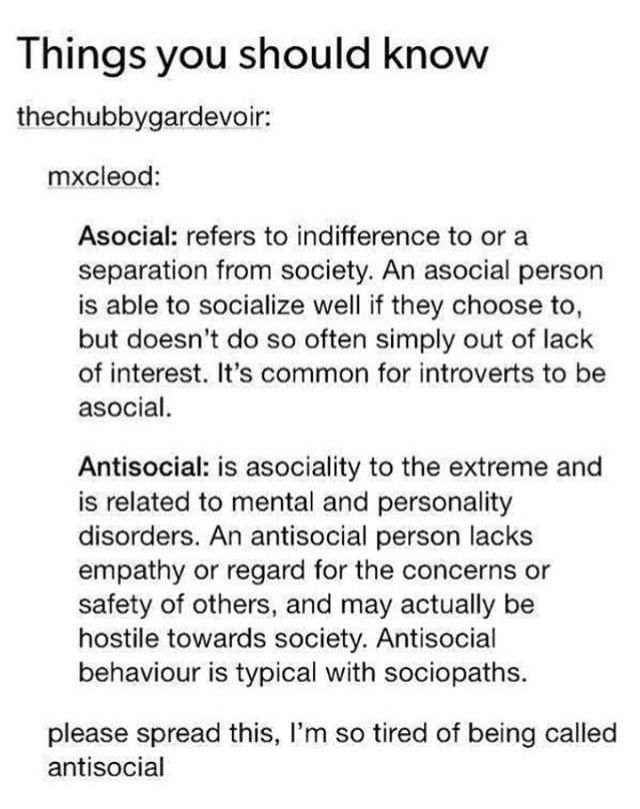

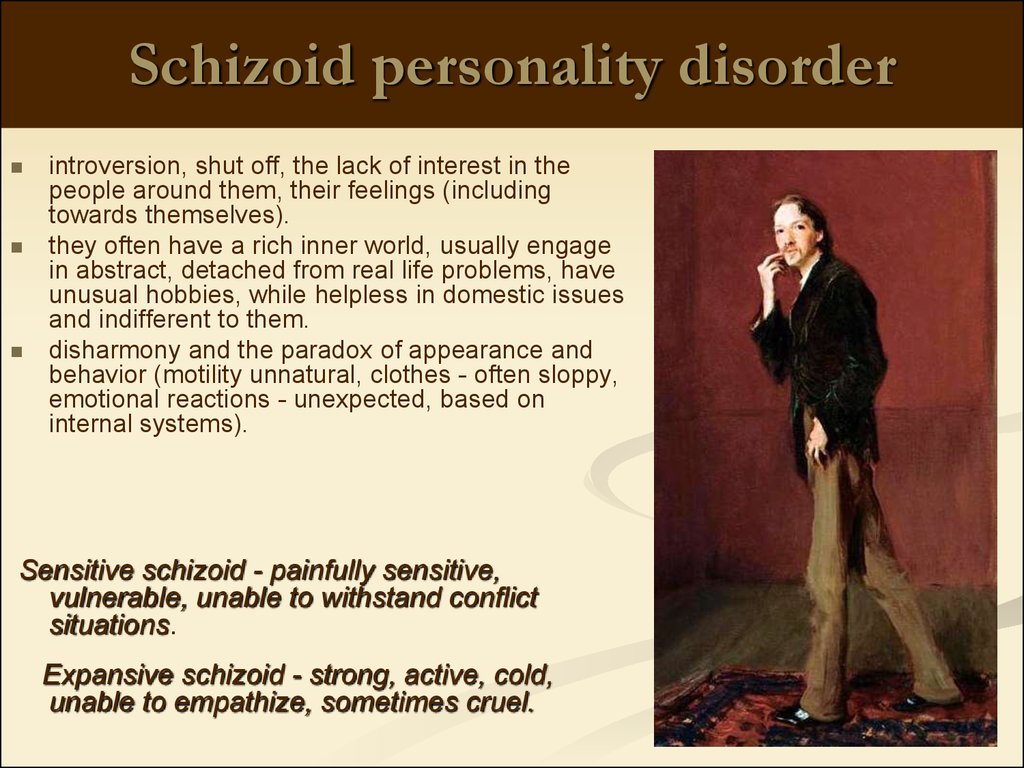

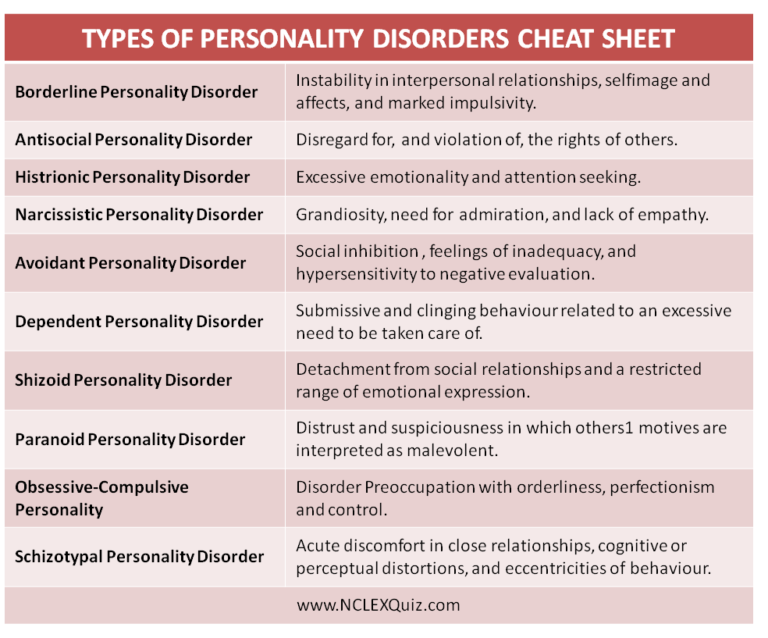

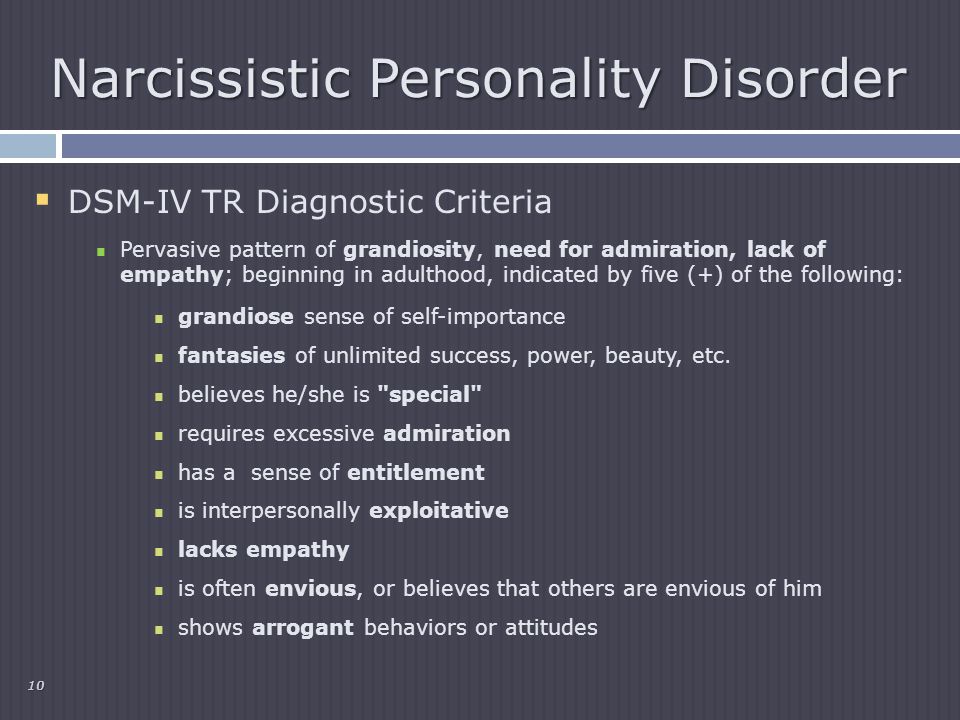

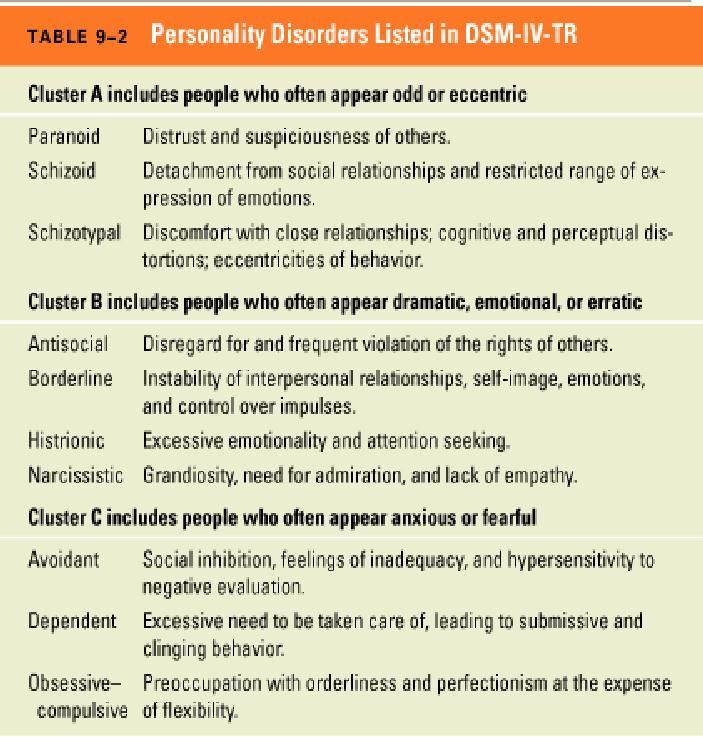

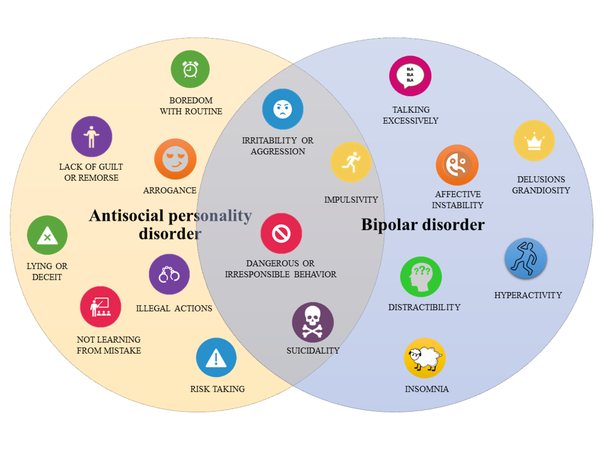

Narcissists and psychopaths lack empathy. It is safe to say that the same applies to patients with other personality disorders, notably the Schizoid, Paranoid, Borderline, Avoidant, and Schizotypal.

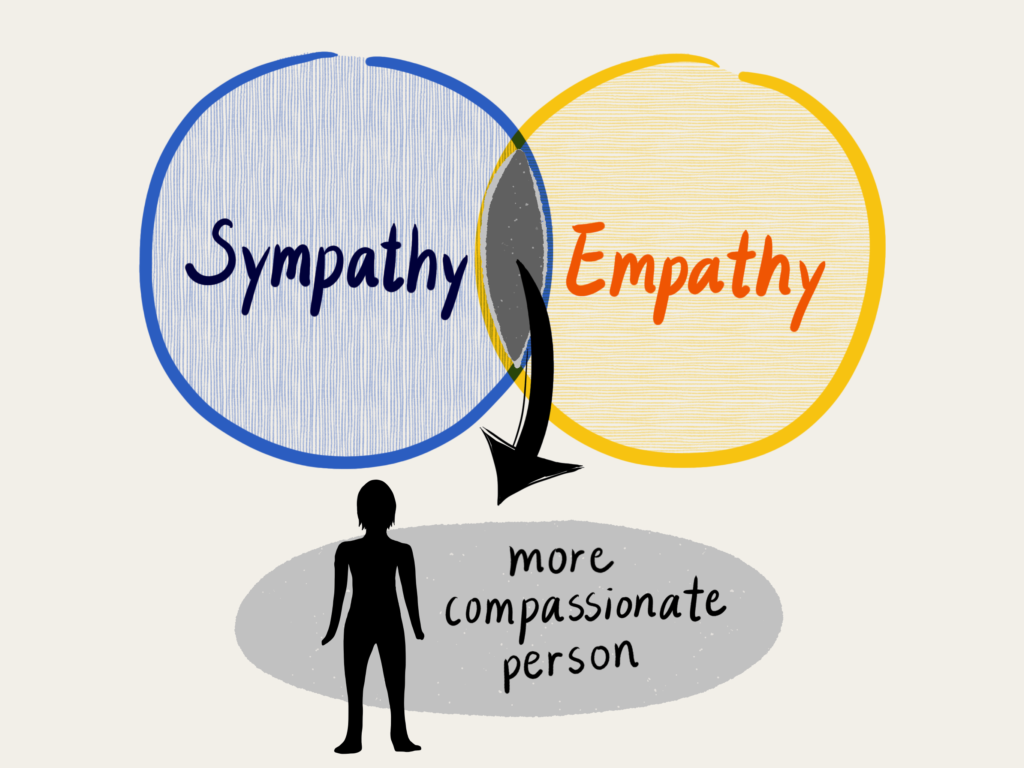

Empathy lubricates the wheels of interpersonal relationships. The Encyclopaedia Britannica (1999 edition) defines empathy as:

"The ability to imagine oneself in anther's place and understand the other's feelings, desires, ideas, and actions. It is a term coined in the early 20th century, equivalent to the German Einfühlung and modelled on "sympathy." The term is used with special (but not exclusive) reference to aesthetic experience. The most obvious example, perhaps, is that of the actor or singer who genuinely feels the part he is performing. With other works of art, a spectator may, by a kind of introjection, feel himself involved in what he observes or contemplates. The use of empathy is an important part of the counselling technique developed by the American psychologist Carl Rogers."

The use of empathy is an important part of the counselling technique developed by the American psychologist Carl Rogers."

This is how empathy is defined in "Psychology - An Introduction" (Ninth Edition) by Charles G. Morris, Prentice Hall, 1996:

"Closely related to the ability to read other people's emotions is empathy - the arousal of an emotion in an observer that is a vicarious response to the other person's situation... Empathy depends not only on one's ability to identify someone else's emotions but also on one's capacity to put oneself in the other person's place and to experience an appropriate emotional response. Just as sensitivity to non-verbal cues increases with age, so does empathy: The cognitive and perceptual abilities required for empathy develop only as a child matures... (page 442)

In empathy training, for example, each member of the couple is taught to share inner feelings and to listen to and understand the partner's feelings before responding to them. The empathy technique focuses the couple's attention on feelings and requires that they spend more time listening and less time in rebuttal." (page 576).

The empathy technique focuses the couple's attention on feelings and requires that they spend more time listening and less time in rebuttal." (page 576).

Empathy is the cornerstone of morality.

The Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1999 Edition:

"Empathy and other forms of social awareness are important in the development of a moral sense. Morality embraces a person's beliefs about the appropriateness or goodness of what he does, thinks, or feels... Childhood is ... the time at which moral standards begin to develop in a process that often extends well into adulthood. The American psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg hypothesized that people's development of moral standards passes through stages that can be grouped into three moral levels...

At the third level, that of postconventional moral reasoning, the adult bases his moral standards on principles that he himself has evaluated and that he accepts as inherently valid, regardless of society's opinion. He is aware of the arbitrary, subjective nature of social standards and rules, which he regards as relative rather than absolute in authority.

He is aware of the arbitrary, subjective nature of social standards and rules, which he regards as relative rather than absolute in authority.

Thus the bases for justifying moral standards pass from avoidance of punishment to avoidance of adult disapproval and rejection to avoidance of internal guilt and self-recrimination. The person's moral reasoning also moves toward increasingly greater social scope (i.e., including more people and instituhttp://www.healthyplace.com/administrator/index.php?option=com_content§ionid=19&task=edit&cid[]=12653tions) and greater abstraction (i.e., from reasoning about physical events such as pain or pleasure to reasoning about values, rights, and implicit contracts)."

"... Others have argued that because even rather young children are capable of showing empathy with the pain of others, the inhibition of aggressive behaviour arises from this moral affect rather than from the mere anticipation of punishment. Some scientists have found that children differ in their individual capacity for empathy, and, therefore, some children are more sensitive to moral prohibitions than others.

Some scientists have found that children differ in their individual capacity for empathy, and, therefore, some children are more sensitive to moral prohibitions than others.

Young children's growing awareness of their own emotional states, characteristics, and abilities leads to empathy--i.e., the ability to appreciate the feelings and perspectives of others. Empathy and other forms of social awareness are in turn important in the development of a moral sense... Another important aspect of children's emotional development is the formation of their self-concept, or identity--i.e., their sense of who they are and what their relation to other people is.

According to Lipps's concept of empathy, a person appreciates another person's reaction by a projection of the self into the other. In his Ästhetik, 2 vol. (1903-06; 'Aesthetics'), he made all appreciation of art dependent upon a similar self-projection into the object. "

"

Empathy - Social Conditioning or Instinct?

This may well be the key. Empathy has little to do with the person with whom we empathize (the empathee). It may simply be the result of conditioning and socialization. In other words, when we hurt someone, we don't experience his or her pain. We experience OUR pain. Hurting somebody - hurts US. The reaction of pain is provoked in US by OUR own actions. We have been taught a learned response: to feel pain when we hurt someone.

We attribute feelings, sensations and experiences to the object of our actions. It is the psychological defence mechanism of projection. Unable to conceive of inflicting pain upon ourselves - we displace the source. It is the other's pain that we are feeling, we keep telling ourselves, not our own.

Additionally, we have been taught to feel responsible for our fellow beings (guilt). So, we also experience pain whenever another person claims to be anguished. We feel guilty owing to his or her condition, we feel somehow accountable even if we had nothing to do with the whole affair.

In sum, to use the example of pain:

When we see someone hurting, we experience pain for two reasons:

1. Because we feel guilty or somehow responsible for his or her condition

2. It is a learned response: we experience our own pain and project it on the empathee.

We communicate our reaction to the other person and agree that we both share the same feeling (of being hurt, of being in pain, in our example). This unwritten and unspoken agreement is what we call empathy.

The Encyclopaedia Britannica:

"Perhaps the most important aspect of children's emotional development is a growing awareness of their own emotional states and the ability to discern and interpret the emotions of others. The last half of the second year is a time when children start becoming aware of their own emotional states, characteristics, abilities, and potential for action; this phenomenon is called self-awareness... (coupled with strong narcissistic behaviours and traits - SV). ..

..

This growing awareness of and ability to recall one's own emotional states leads to empathy, or the ability to appreciate the feelings and perceptions of others. Young children's dawning awareness of their own potential for action inspires them to try to direct (or otherwise affect) the behaviour of others...

...With age, children acquire the ability to understand the perspective, or point of view, of other people, a development that is closely linked with the empathic sharing of others' emotions...

One major factor underlying these changes is the child's increasing cognitive sophistication. For example, in order to feel the emotion of guilt, a child must appreciate the fact that he could have inhibited a particular action of his that violated a moral standard. The awareness that one can impose a restraint on one's own behaviour requires a certain level of cognitive maturation, and, therefore, the emotion of guilt cannot appear until that competence is attained. "

"

Still, empathy may be an instinctual REACTION to external stimuli that is fully contained within the empathor and then projected onto the empathee. This is clearly demonstrated by "inborn empathy". It is the ability to exhibit empathy and altruistic behaviour in response to facial expressions. Newborns react this way to their mother's facial expression of sadness or distress.

This serves to prove that empathy has very little to do with the feelings, experiences or sensations of the other (the empathee). Surely, the infant has no idea what it is like to feel sad and definitely not what it is like for his mother to feel sad. In this case, it is a complex reflexive reaction. Later on, empathy is still rather reflexive, the result of conditioning.

The Encyclopaedia Britannica quotes some fascinating research that support the model I propose:

"An extensive series of studies indicated that positive emotion feelings enhance empathy and altruism. It was shown by the American psychologist Alice M. Isen that relatively small favours or bits of good luck (like finding money in a coin telephone or getting an unexpected gift) induced positive emotion in people and that such emotion regularly increased the subjects' inclination to sympathize or provide help.

It was shown by the American psychologist Alice M. Isen that relatively small favours or bits of good luck (like finding money in a coin telephone or getting an unexpected gift) induced positive emotion in people and that such emotion regularly increased the subjects' inclination to sympathize or provide help.

Several studies have demonstrated that positive emotion facilitates creative problem solving. One of these studies showed that positive emotion enabled subjects to name more uses for common objects. Another showed that positive emotion enhanced creative problem solving by enabling subjects to see relations among objects (and other people - SV) that would otherwise go unnoticed. A number of studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of positive emotion on thinking, memory, and action in pre-school and older children."

If empathy increases with positive emotion, then it has little to do with the empathee (the recipient or object of empathy) and everything to do with the empathor (the person who does the empathizing).

Cold Empathy vs. Warm Empathy

Contrary to widely held views, Narcissists and Psychopaths may actually possess empathy. They may even be hyper-empathic, attuned to the minutest signals emitted by their victims and endowed with a penetrating "X-ray vision". They tend to abuse their empathic skills by employing them exclusively for personal gain, the extraction of narcissistic supply, or in the pursuit of antisocial and sadistic goals. They regard their ability to empathize as another weapon in their arsenal.

I suggest to label the narcissistic psychopath's version of empathy: "cold empathy", akin to the "cold emotions" felt by psychopaths. The cognitive element of empathy is there, but not so its emotional correlate. It is, consequently, a barren, cold, and cerebral kind of intrusive gaze, devoid of compassion and a feeling of affinity with one's fellow humans.

ADDENDUM - Interview granted to the National Post, Toronto, Canada, July 2003

Q. How important is empathy to proper psychological functioning?

How important is empathy to proper psychological functioning?

A. Empathy is more important socially than it is psychologically. The absence of empathy - for instance in the Narcissistic and Antisocial personality disorders - predisposes people to exploit and abuse others. Empathy is the bedrock of our sense of morality. Arguably, aggressive behavior is as inhibited by empathy at least as much as it is by anticipated punishment.

But the existence of empathy in a person is also a sign of self-awareness, a healthy identity, a well-regulated sense of self-worth, and self-love (in the positive sense). Its absence denotes emotional and cognitive immaturity, an inability to love, to truly relate to others, to respect their boundaries and accept their needs, feelings, hopes, fears, choices, and preferences as autonomous entities.

Q. How is empathy developed?

A. It may be innate. Even toddlers seem to empathize with the pain - or happiness - of others (such as their caregivers). Empathy increases as the child forms a self-concept (identity). The more aware the infant is of his or her emotional states, the more he explores his limitations and capabilities - the more prone he is to projecting this new found knowledge unto others. By attributing to people around him his new gained insights about himself, the child develop a moral sense and inhibits his anti-social impulses. The development of empathy is, therefore, a part of the process of socialization.

Even toddlers seem to empathize with the pain - or happiness - of others (such as their caregivers). Empathy increases as the child forms a self-concept (identity). The more aware the infant is of his or her emotional states, the more he explores his limitations and capabilities - the more prone he is to projecting this new found knowledge unto others. By attributing to people around him his new gained insights about himself, the child develop a moral sense and inhibits his anti-social impulses. The development of empathy is, therefore, a part of the process of socialization.

But, as the American psychologist Carl Rogers taught us, empathy is also learned and inculcated. We are coached to feel guilt and pain when we inflict suffering on another person. Empathy is an attempt to avoid our own self-imposed agony by projecting it onto another.

Q. Is there an increasing dearth of empathy in society today? Why do you think so?

A. The social institutions that reified, propagated and administered empathy have imploded. The nuclear family, the closely-knit extended clan, the village, the neighborhood, the Church- have all unraveled. Society is atomized and anomic. The resulting alienation fostered a wave of antisocial behavior, both criminal and "legitimate". The survival value of empathy is on the decline. It is far wiser to be cunning, to cut corners, to deceive, and to abuse - than to be empathic. Empathy has largely dropped from the contemporary curriculum of socialization.

The nuclear family, the closely-knit extended clan, the village, the neighborhood, the Church- have all unraveled. Society is atomized and anomic. The resulting alienation fostered a wave of antisocial behavior, both criminal and "legitimate". The survival value of empathy is on the decline. It is far wiser to be cunning, to cut corners, to deceive, and to abuse - than to be empathic. Empathy has largely dropped from the contemporary curriculum of socialization.

In a desperate attempt to cope with these inexorable processes, behaviors predicated on a lack of empathy have been pathologized and "medicalized". The sad truth is that narcissistic or antisocial conduct is both normative and rational. No amount of "diagnosis", "treatment", and medication can hide or reverse this fact. Ours is a cultural malaise which permeates every single cell and strand of the social fabric.

Q. Is there any empirical evidence we can point to of a decline in empathy?

Empathy cannot be measured directly - but only through proxies such as criminality, terrorism, charity, violence, antisocial behavior, related mental health disorders, or abuse.

Moreover, it is extremely difficult to separate the effects of deterrence from the effects of empathy.

If I don't batter my wife, torture animals, or steal - is it because I am empathetic or because I don't want to go to jail?

Rising litigiousness, zero tolerance, and skyrocketing rates of incarceration - as well as the ageing of the population - have sliced intimate partner violence and other forms of crime across the United States in the last decade. But this benevolent decline had nothing to do with increasing empathy.

The statistics are open to interpretation but it would be safe to say that the last century has been the most violent and least empathetic in human history. Wars and terrorism are on the rise, charity giving on the wane (measured as percentage of national wealth), welfare policies are being abolished, Darwinian models of capitalism are spreading. In the last two decades, mental health disorders were added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association whose hallmark is the lack of empathy. The violence is reflected in our popular culture: movies, video games, and the media.

The violence is reflected in our popular culture: movies, video games, and the media.

Empathy - supposedly a spontaneous reaction to the plight of our fellow humans - is now channeled through self-interested and bloated non-government organizations or multilateral outfits. The vibrant world of private empathy has been replaced by faceless state largesse. Pity, mercy, the elation of giving are tax-deductible. It is a sorry sight.

Click on this link to read a detailed analysis of empathy:

On Empathy

Other People's Pain - click on this link:

Narcissists Enjoy Other People's Pain

This article appears in my book, "Malignant Self Love - Narcissism Revisited"

next: Psychosis, Delusions, and Personality Disorders

APA Reference

Vaknin, S. (2009, October 2). Empathy and Personality Disorders, HealthyPlace. Retrieved on 2023, March 25 from https://www.healthyplace.com/personality-disorders/malignant-self-love/empathy-and-personality-disorders

Retrieved on 2023, March 25 from https://www.healthyplace.com/personality-disorders/malignant-self-love/empathy-and-personality-disorders

Borderline personality traits linked to lowered empathy -- ScienceDaily

Those with borderline personality disorder, or BPD, a mental illness marked by unstable moods, often experience trouble maintaining interpersonal relationships. New research from the University of Georgia indicates that this may have to do with lowered brain activity in regions important for empathy in individuals with borderline personality traits.

The findings were recently published in the journal Personality Disorders: Theory, Research and Treatment.

"Our results showed that people with BPD traits had reduced activity in brain regions that support empathy," said the study's lead author Brian Haas, an assistant professor in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences psychology department. "This reduced activation may suggest that people with more BPD traits have a more difficult time understanding and/or predicting how others feel, at least compared to individuals with fewer BPD traits. "

"

For the study, Haas recruited over 80 participants and asked them to take a questionnaire, called the Five Factor Borderline Inventory, to determine the degree to which they had various traits associated with borderline personality disorder. The researchers then used functional magnetic resonance imaging to measure brain activity in each of the participants. During the fMRI, participants were asked to do an empathetic processing task, which tapped into their ability to think about the emotional states of other people, while the fMRI measured their simultaneous brain activity.

In the empathetic processing task, participants would match the emotion of faces to a situation's context. As a control, Haas and study co-author Joshua Miller also included shapes, like squares and circles, that participants would have to match from emotion of the faces to the situation.

"We found that for those with more BPD traits, these empathetic processes aren't as easily activated," said Miller, a psychology professor and director of the Clinical Training Program.

Haas chose to look at those who scored high on the Five Factor Borderline Inventory, instead of simply working with those previously diagnosed with the disorder. By using the inventory, Haas was able to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between empathic processing, BPD traits and high levels of neuroticism and openness, as well as lower levels of agreeableness and conscientiousness.

"Oftentimes, borderline personality disorder is considered a binary phenomenon. Either you have it or you don't," said Haas, who runs the Gene-Brain-Social Behavioral Lab. "But for our study, we conceptualized and measured it in a more continuous way such that individuals can vary along a continuum of no traits to very many BPD traits."

Haas found a link between those with high borderline personality traits and a decreased use of neural activity in two parts of the brain: the temporoparietal junction and the superior temporal sulcus, two brain regions implicated to be critically important during empathic processing.

The research provides new insight into individuals susceptible to experiencing the disorder and how they process emotions.

"Borderline personality disorder is considered one of the most severe and troubling personality disorders," Miller said. "BPD can make it difficult to have successful friendships and romantic relationships. These findings could help explain why that is."

In the future, Haas would like to study BPD traits in a more naturalistic setting.

"In this study, we looked at participants who had a relatively high amount of BPD traits. I think it'd be great to study this situation in a real life scenario, such as having people with BPD traits read the emotional states of their partners," he said.

10 facts about empathy: Society Articles ➕1, 06/22/2020

The scientific concept of “empathy” is more than a hundred years old, but the term has come into fashion among personal growth consultants and business coaches in recent years. Developing empathy as an integral part of "emotional intelligence" is advised to bosses of any rank, politicians and marketers, as it will help them achieve their goals. Plus-one.ru has collected ten scientific facts about empathy, confirmed by scientific research.

Developing empathy as an integral part of "emotional intelligence" is advised to bosses of any rank, politicians and marketers, as it will help them achieve their goals. Plus-one.ru has collected ten scientific facts about empathy, confirmed by scientific research.

Photo: iStock.com

Fact 1: Lack of empathy can be a sign of mental illness. Empathy is an emotional response, empathy for a communication partner. The term is a tracing-paper from the German Einfühlung, introduced in 1885 by Theodor Lipps when describing the impact of art on people.

British psychologist Simon Baron-Cohen proposed a scale of empathy from zero (complete absence) to six (altruism). A complete lack of empathy is associated with various diseases (narcissistic personality disorder, psychopathy, and so on), and an excess of empathy, when a person is constantly focused on the feelings of other people, is commonly called altruism.

It is believed that a large number of people with a high level of empathy makes both people and entire societies virtuous. However, altruists themselves often face difficulties in building personal boundaries.

Fact 2. Empathy is innate and is associated with the work of mirror neurons . This is evidenced by the behavior of a baby who screams when he hears a baby crying from a nearby crib or copying the mother's emotions. This copying is an important part of growing up as a person “learns” emotions. Mirror neurons are involved in the neurophysiological mechanisms of empathy. During the experiments, it was found that if a person is told about something vile, they excite the very neurons that are responsible for disgust, and if they talk about someone else's pain, the brain reacts as if the pain is experienced by its owner.

Fact 3. Empathy is not unique to humans. The Dutch primatologist Frans de Waal describes examples of helping behavior in animals in the book In Search of Humanity in Primates. Just like in humans, empathic (helping) behavior is based on experience. In a number of experiments, it has been proven that rats try to help their relatives in danger through which they themselves have passed. In the course of experiments at the Japanese Kansei Gakuin University, one rat sank into a tank of water, while the other had the opportunity to open the door of this tank in order to save her. Behind another door, there was a chocolate treat nearby. The second rat first saved the first, and then shared food with her. Those rats that were already drowning in a tank of water reacted faster than the others.

Just like in humans, empathic (helping) behavior is based on experience. In a number of experiments, it has been proven that rats try to help their relatives in danger through which they themselves have passed. In the course of experiments at the Japanese Kansei Gakuin University, one rat sank into a tank of water, while the other had the opportunity to open the door of this tank in order to save her. Behind another door, there was a chocolate treat nearby. The second rat first saved the first, and then shared food with her. Those rats that were already drowning in a tank of water reacted faster than the others.

Fact 4. Empathy is only partially transmitted genetically. This was shown by a study at the University of Cambridge, in which 46,000 people took part: each test subject completed a survey and received an “empathy coefficient” as a result, and also passed saliva samples for a DNA test. In this experiment, scientists looked for differences in genes that could explain why some people are more empathetic than others. Experience has shown that only in 10% of cases the ability to empathize in humans is genetically determined. At the same time, scientists have not yet discovered a specific “empathy gene”. AT 90% empathy is a cultural product.

Experience has shown that only in 10% of cases the ability to empathize in humans is genetically determined. At the same time, scientists have not yet discovered a specific “empathy gene”. AT 90% empathy is a cultural product.

Fact 5: Women are more empathetic than men. Experiments by a group of scientists from the US, Italy and the UK show that women are more empathetic than men. However, this is due not so much to biological characteristics, but to cultural norms: gender attitudes, activities related to caring for loved ones.

Empathy also has a number of "politically incorrect" properties: we are more willing to show it in relation to outwardly attractive people, as well as to people of our own race and nationality. At the same time, in multicultural societies with rich experience in combating xenophobia, this gap is not so clear.

Fact 6. The level of empathy is not constant. Changes depend on many circumstances: experience, state of mind, external factors, and so on. The famous experiment of Professor Stanley Milgram of Yale University proved that people are highly dependent on authorities for manifestations of empathy. As part of the experiment, participants were asked to inflict pain (shock) on another person (in reality, an actor). Despite their doubts, most of the participants agreed to gradually increase the current and cause suffering, as a “scientist” in a white coat stood nearby and encouraged them with the phrases: “Please continue”, “It is absolutely necessary that you continue”, and so on. Of the 40 participants, 26 reached the end of the scale (when the suffering inflicted was the highest).

Changes depend on many circumstances: experience, state of mind, external factors, and so on. The famous experiment of Professor Stanley Milgram of Yale University proved that people are highly dependent on authorities for manifestations of empathy. As part of the experiment, participants were asked to inflict pain (shock) on another person (in reality, an actor). Despite their doubts, most of the participants agreed to gradually increase the current and cause suffering, as a “scientist” in a white coat stood nearby and encouraged them with the phrases: “Please continue”, “It is absolutely necessary that you continue”, and so on. Of the 40 participants, 26 reached the end of the scale (when the suffering inflicted was the highest).

Subsequently, scientists repeated the Milgram experiment several times, and the results turned out to be close to the original ones. In particular, Jerry M. Burger repeated the experiment in 2009, changing several protocols in accordance with ethical requirements. During the experiment, participants could see how others refused to continue the experience, but even in this state, many obeyed the "doctors".

During the experiment, participants could see how others refused to continue the experience, but even in this state, many obeyed the "doctors".

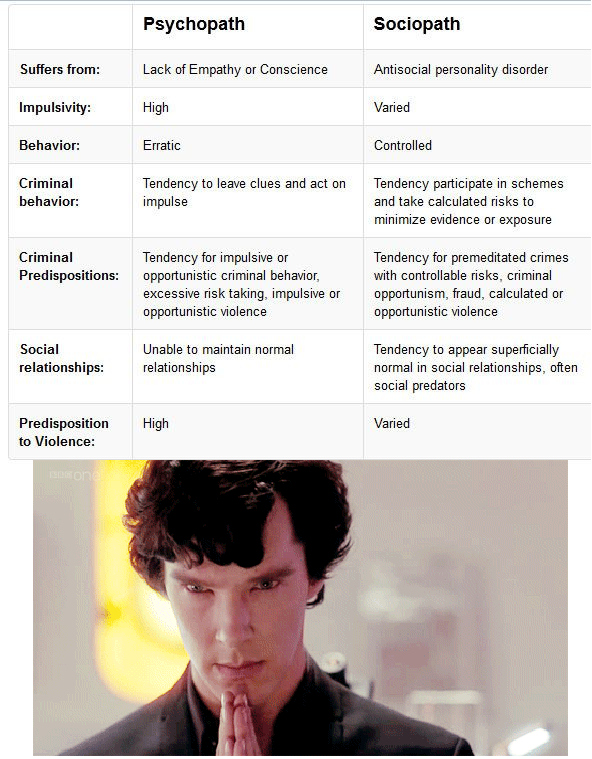

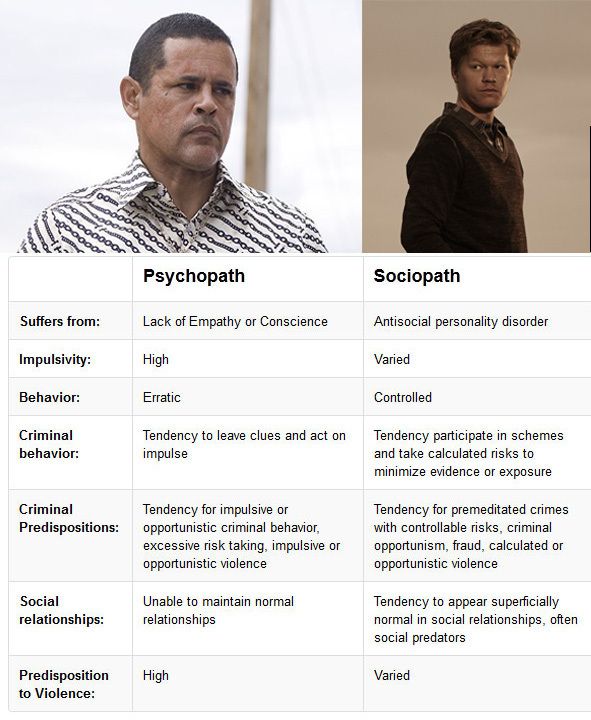

Fact 7. Reduced empathy does not lead to aggressive behavior. A study of several dozen violent offenders found reduced levels of empathy in perpetrators. Aggressive participants in the experiment had a decrease in empathic response to emotional videos of others suffering. However, in people suffering from narcissistic disorders and psychopathy, empathy can also be reduced, but they are not prone to violent actions. It turned out that the decrease in empathy in aggressive men was caused by alexithymia - the inability to describe one's own state, focusing on external events to the detriment of internal experiences, a tendency to utilitarian thinking with a deficit of emotional reactions.

Fact 8. The bystander effect reduces empathy. Empathy tends to "dissipate": hence people's idea of "loneliness in a crowd", of the rigidity of city dwellers compared to village dwellers. Psychologists John Darley and Bibb Latane conducted an experiment they called the "witness effect": experimental students were taken to different rooms, where they were offered to listen to how an actor (students did not know that he was an actor) played out a scene of an epileptic seizure. If the participant in the experiment believed that he was the only witness of the "attack", the victim received help in 85% of cases, if the participants knew that there were two of them - in 62%, if they thought that there were five of them - only in 31% of cases. Scientists have called this effect “responsibility diffusion”.

Psychologists John Darley and Bibb Latane conducted an experiment they called the "witness effect": experimental students were taken to different rooms, where they were offered to listen to how an actor (students did not know that he was an actor) played out a scene of an epileptic seizure. If the participant in the experiment believed that he was the only witness of the "attack", the victim received help in 85% of cases, if the participants knew that there were two of them - in 62%, if they thought that there were five of them - only in 31% of cases. Scientists have called this effect “responsibility diffusion”.

Fact 9. Empathy helps you be more successful. In modern business, empathy has become an important element of management. A joint study on the psychology of hedge fund managers by researchers at the University of Denver and the University of California at Berkeley found that people with reduced empathy and pronounced psychopathic traits are more successful in name than in deed. Ruthlessness and callousness in the modern world help business less. Psychopaths often cause chaos in the workplace, their actions lead to staff drain and reduced employee productivity.

Ruthlessness and callousness in the modern world help business less. Psychopaths often cause chaos in the workplace, their actions lead to staff drain and reduced employee productivity.

Fact 10. Empathy and happiness are related. Happy people tend to be more altruistic and empathetic than unhappy people. Child behavior researchers have found that children who are often punished are less generous than those who are not punished at all or rarely punished. At the same time, helping others improves bad moods and prolongs good ones. Charles Darwin argued that we ourselves need empathy in order to live in harmony with our conscience: “If we, under the influence of selfishness, do not follow the desire to help our neighbor, then later, when we vividly imagine the disaster we are experiencing, the desire to help will arise again and its dissatisfaction will cause in us painful pangs of conscience.

Author

Ekaterina Drankina

"Paradox of borderline empathy" - Information portal

Empathy is an important ability of the human psyche. Through empathy, we can empathize, put ourselves in the place of another, and feel and feel the emotional state of a person.

Through empathy, we can empathize, put ourselves in the place of another, and feel and feel the emotional state of a person.

In mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, there is a violation of empathy. The patient does not understand what another person can feel in various situations, he lacks emotional empathy, sympathy.

In borderline personality disorder, empathy may be enhanced despite impaired interpersonal functioning.

This condition is called the “borderline empathy paradox” (Franzen et al., 2011; Krohn, 1974; Dinsdale, 2013).

In general, it is extremely difficult to notice any disturbances in BPD “in non-regressive states, the patients' sense of reality is perfectly fine, and they do not look particularly “sick”, they can often present themselves in such a way that they arouse the empathy of the therapist. “Perceived competence” may be one reason that borderline personality disorder is overlooked or misdiagnosed” (McWilliams, 1998).

Based on therapeutic interactions with borderline patients, psychoanalyst Alan Krohn (1974) first identified the paradoxical nature of empathy.

People with BPD have an uncanny sensitivity to the subconscious mental content and states of others, despite their inability to consistently integrate such information into the stable beliefs about self and others that are fundamental to healthy interpersonal functioning.

There has been significant research into the hypersensitivity of BPD patients to facial cues; their scores on the mind-in-the-eyes test may be better than usual, giving clinicians the impression that their patients are better than others at empathy (the "borderline empathy paradox"; Dinsdale & Crespi, 2013).

Both Krohn (1974) and Carter and Rinsley (1977) found that heightened empathic sensitivity develops in the borderline child in response to neglected parenting.

The child develops hypersensitivity to behavioral traits indicative of the parent's mental state (Carter & Rinsley, 1977).