Complicated grief therapy

SAMHSA’s National Helpline | SAMHSA

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Main page content

-

SAMHSA’s National Helpline is a free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year treatment referral and information service (in English and Spanish) for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

Also visit the online treatment locator.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357) (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

Also visit the online treatment locator, or send your zip code via text message: 435748 (HELP4U) to find help near you. Read more about the HELP4U text messaging service.

The service is open 24/7, 365 days a year.

English and Spanish are available if you select the option to speak with a national representative. Currently, the 435748 (HELP4U) text messaging service is only available in English.

In 2020, the Helpline received 833,598 calls. This is a 27 percent increase from 2019, when the Helpline received a total of 656,953 calls for the year.

The referral service is free of charge. If you have no insurance or are underinsured, we will refer you to your state office, which is responsible for state-funded treatment programs. In addition, we can often refer you to facilities that charge on a sliding fee scale or accept Medicare or Medicaid. If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

In addition, we can often refer you to facilities that charge on a sliding fee scale or accept Medicare or Medicaid. If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

The service is confidential. We will not ask you for any personal information. We may ask for your zip code or other pertinent geographic information in order to track calls being routed to other offices or to accurately identify the local resources appropriate to your needs.

No, we do not provide counseling. Trained information specialists answer calls, transfer callers to state services or other appropriate intake centers in their states, and connect them with local assistance and support.

-

Suggested Resources

What Is Substance Abuse Treatment? A Booklet for Families

Created for family members of people with alcohol abuse or drug abuse problems. Answers questions about substance abuse, its symptoms, different types of treatment, and recovery. Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.

Answers questions about substance abuse, its symptoms, different types of treatment, and recovery. Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.It's Not Your Fault (NACoA) (PDF | 12 KB)

Assures teens with parents who abuse alcohol or drugs that, "It's not your fault!" and that they are not alone. Encourages teens to seek emotional support from other adults, school counselors, and youth support groups such as Alateen, and provides a resource list.After an Attempt: A Guide for Taking Care of Your Family Member After Treatment in the Emergency Department

Aids family members in coping with the aftermath of a relative's suicide attempt. Describes the emergency department treatment process, lists questions to ask about follow-up treatment, and describes how to reduce risk and ensure safety at home.Family Therapy Can Help: For People in Recovery From Mental Illness or Addiction

Explores the role of family therapy in recovery from mental illness or substance abuse. Explains how family therapy sessions are run and who conducts them, describes a typical session, and provides information on its effectiveness in recovery.

Explains how family therapy sessions are run and who conducts them, describes a typical session, and provides information on its effectiveness in recovery.For additional resources, please visit the SAMHSA Store.

Last Updated: 08/30/2022

Alcohol, Tobacco, and Other Drugs

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Misusing alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs can have both immediate and long-term health effects.The misuse and abuse of alcohol, tobacco, illicit drugs, and prescription medications affect the health and well-being of millions of Americans. NSDUH estimates allow researchers, clinicians, policymakers, and the general public to better understand and improve the nation’s behavioral health. These reports and detailed tables present estimates from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH).

Alcohol

Data:

- Among the 133.1 million current alcohol users aged 12 or older in 2021, 60.0 million people (or 45.1%) were past month binge drinkers. The percentage of people who were past month binge drinkers was highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 (29.2% or 9.8 million people), followed by adults aged 26 or older (22.4% or 49.3 million people), then by adolescents aged 12 to 17 (3.8% or 995,000 people). (2021 NSDUH)

- Among people aged 12 to 20 in 2021, 15.1% (or 5.9 million people) were past month alcohol users. Estimates of binge alcohol use and heavy alcohol use in the past month among underage people were 8.3% (or 3.2 million people) and 1.6% (or 613,000 people), respectively. (2021 NSDUH)

- In 2020, 50.0% of people aged 12 or older (or 138.5 million people) used alcohol in the past month (i.e., current alcohol users) (2020 NSDUH)

- Among the 138.5 million people who were current alcohol users, 61.6 million people (or 44.

4%) were classified as binge drinkers and 17.7 million people (28.8% of current binge drinkers and 12.8% of current alcohol users) were classified as heavy drinkers (2020 NSDUH)

4%) were classified as binge drinkers and 17.7 million people (28.8% of current binge drinkers and 12.8% of current alcohol users) were classified as heavy drinkers (2020 NSDUH) - The percentage of people who were past month binge alcohol users was highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 (31.4%) compared with 22.9% of adults aged 26 or older and 4.1% of adolescents aged 12 to 17 (2020 NSDUH)

- Excessive alcohol use can increase a person’s risk of stroke, liver cirrhosis, alcoholic hepatitis, cancer, and other serious health conditions

- Excessive alcohol use can also lead to risk-taking behavior, including driving while impaired. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that 29 people in the United States die in motor vehicle crashes that involve an alcohol-impaired driver daily

Programs/Initiatives:

- STOP Underage Drinking interagency portal - Interagency Coordinating Committee on the Prevention of Underage Drinking

- Interagency Coordinating Committee on the Prevention of Underage Drinking

- Talk.

They Hear You.

They Hear You. - Underage Drinking: Myths vs. Facts

- Talking with your College-Bound Young Adult About Alcohol

Relevant links:

- National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors

- Department of Transportation Office of Drug & Alcohol Policy & Compliance

- Alcohol Policy Information Systems Database (APIS)

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

Tobacco

Data:

- In 2020, 20.7% of people aged 12 or older (or 57.3 million people) used nicotine products (i.e., used tobacco products or vaped nicotine) in the past month (2020 NSDUH)

- Among past month users of nicotine products, nearly two thirds of adolescents aged 12 to 17 (63.1%) vaped nicotine but did not use tobacco products. In contrast, 88.9% of past month nicotine product users aged 26 or older used only tobacco products (2020 NSDUH)

- Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable death, often leading to lung cancer, respiratory disorders, heart disease, stroke, and other serious illnesses.

The CDC reports that cigarette smoking causes more than 480,000 deaths each year in the United States

The CDC reports that cigarette smoking causes more than 480,000 deaths each year in the United States - The CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health reports that more than 16 million Americans are living with a disease caused by smoking cigarettes

Electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use data:

- In 2021, 13.2 million people aged 12 or older (or 4.7%) used an e-cigarette or other vaping device to vape nicotine in the past month. The percentage of people who vaped nicotine was highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 (14.1% or 4.7 million people), followed by adolescents aged 12 to 17 (5.2% or 1.4 million people), then by adults aged 26 or older (3.2% or 7.1 million people).

- Among people aged 12 to 20 in 2021, 11.0% (or 4.3 million people) used tobacco products or used an e-cigarette or other vaping device to vape nicotine in the past month. Among people in this age group, 8.1% (or 3.1 million people) vaped nicotine, 5.4% (or 2.1 million people) used tobacco products, and 3.

4% (or 1.3 million people) smoked cigarettes in the past month. (2021 NSDUH)

4% (or 1.3 million people) smoked cigarettes in the past month. (2021 NSDUH) - Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2020 National Youth Tobacco Survey. Among both middle and high school students, current use of e-cigarettes declined from 2019 to 2020, reversing previous trends and returning current e-cigarette use to levels similar to those observed in 2018

- E-cigarettes are not safe for youth, young adults, or pregnant women, especially because they contain nicotine and other chemicals

Resources:

- Tips for Teens: Tobacco

- Tips for Teens: E-cigarettes

- Implementing Tobacco Cessation Programs in Substance Use Disorder Treatment Settings

- Synar Amendment Program

Links:

- Truth Initiative

- FDA Center for Tobacco Products

- CDC Office on Smoking and Health

- National Institute on Drug Abuse: Tobacco, Nicotine, and E-Cigarettes

- National Institute on Drug Abuse: E-Cigarettes

Opioids

Data:

- Among people aged 12 or older in 2021, 3.

3% (or 9.2 million people) misused opioids (heroin or prescription pain relievers) in the past year. Among the 9.2 million people who misused opioids in the past year, 8.7 million people misused prescription pain relievers compared with 1.1 million people who used heroin. These numbers include 574,000 people who both misused prescription pain relievers and used heroin in the past year. (2021 NSDUH)

3% (or 9.2 million people) misused opioids (heroin or prescription pain relievers) in the past year. Among the 9.2 million people who misused opioids in the past year, 8.7 million people misused prescription pain relievers compared with 1.1 million people who used heroin. These numbers include 574,000 people who both misused prescription pain relievers and used heroin in the past year. (2021 NSDUH) - Among people aged 12 or older in 2020, 3.4% (or 9.5 million people) misused opioids in the past year. Among the 9.5 million people who misused opioids in the past year, 9.3 million people misused prescription pain relievers and 902,000 people used heroin (2020 NSDUH)

- According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Understanding the Epidemic, an average of 128 Americans die every day from an opioid overdose

Resources:

- Medications for Substance Use Disorders

- Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit

- TIP 63: Medications for Opioid Use Disorder

- Use of Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Criminal Justice Settings

- Opioid Use Disorder and Pregnancy

- Clinical Guidance for Treating Pregnant and Parenting Women With Opioid Use Disorder and Their Infants

- The Facts about Buprenorphine for Treatment of Opioid Addiction

- Pregnancy Planning for Women Being Treated for Opioid Use Disorder

- Tips for Teens: Opioids

- Rural Opioid Technical Assistance Grants

- Tribal Opioid Response Grants

- Provider’s Clinical Support System - Medication Assisted Treatment Grant Program

Links:

- National Institute on Drug Abuse: Opioids

- National Institute on Drug Abuse: Heroin

- HHS Prevent Opioid Abuse

- Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America

- Addiction Technology Transfer Center (ATTC) Network

- Prevention Technology Transfer Center (PTTC) Network

Marijuana

Data:

- In 2021, marijuana was the most commonly used illicit drug, with 18.

7% of people aged 12 or older (or 52.5 million people) using it in the past year. The percentage was highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 (35.4% or 11.8 million people), followed by adults aged 26 or older (17.2% or 37.9 million people), then by adolescents aged 12 to 17 (10.5% or 2.7 million people).

7% of people aged 12 or older (or 52.5 million people) using it in the past year. The percentage was highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 (35.4% or 11.8 million people), followed by adults aged 26 or older (17.2% or 37.9 million people), then by adolescents aged 12 to 17 (10.5% or 2.7 million people). - The percentage of people who used marijuana in the past year was highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 (34.5%) compared with 16.3% of adults aged 26 or older and 10.1% of adolescents aged 12 to 17 (2020 NSDUH)

- Marijuana can impair judgment and distort perception in the short term and can lead to memory impairment in the long term

- Marijuana can have significant health effects on youth and pregnant women.

Resources:

- Know the Risks of Marijuana

- Marijuana and Pregnancy

- Tips for Teens: Marijuana

Relevant links:

- National Institute on Drug Abuse: Marijuana

- Addiction Technology Transfer Centers on Marijuana

- CDC Marijuana and Public Health

Emerging Trends in Substance Misuse:

- Methamphetamine—In 2019, NSDUH data show that approximately 2 million people used methamphetamine in the past year.

Approximately 1 million people had a methamphetamine use disorder, which was higher than the percentage in 2016, but similar to the percentages in 2015 and 2018. The National Institute on Drug Abuse Data shows that overdose death rates involving methamphetamine have quadrupled from 2011 to 2017. Frequent meth use is associated with mood disturbances, hallucinations, and paranoia.

Approximately 1 million people had a methamphetamine use disorder, which was higher than the percentage in 2016, but similar to the percentages in 2015 and 2018. The National Institute on Drug Abuse Data shows that overdose death rates involving methamphetamine have quadrupled from 2011 to 2017. Frequent meth use is associated with mood disturbances, hallucinations, and paranoia. - Cocaine—In 2019, NSDUH data show an estimated 5.5 million people aged 12 or older were past users of cocaine, including about 778,000 users of crack. The CDC reports that overdose deaths involving have increased by one-third from 2016 to 2017. In the short term, cocaine use can result in increased blood pressure, restlessness, and irritability. In the long term, severe medical complications of cocaine use include heart attacks, seizures, and abdominal pain.

- Kratom—In 2019, NSDUH data show that about 825,000 people had used Kratom in the past month. Kratom is a tropical plant that grows naturally in Southeast Asia with leaves that can have psychotropic effects by affecting opioid brain receptors.

It is currently unregulated and has risk of abuse and dependence. The National Institute on Drug Abuse reports that health effects of Kratom can include nausea, itching, seizures, and hallucinations.

It is currently unregulated and has risk of abuse and dependence. The National Institute on Drug Abuse reports that health effects of Kratom can include nausea, itching, seizures, and hallucinations.

Resources:

- Tips for Teens: Methamphetamine

- Tips for Teens: Cocaine

- National Institute on Drug Abuse

More SAMHSA publications on substance use prevention and treatment.

Last Updated: 03/22/2023

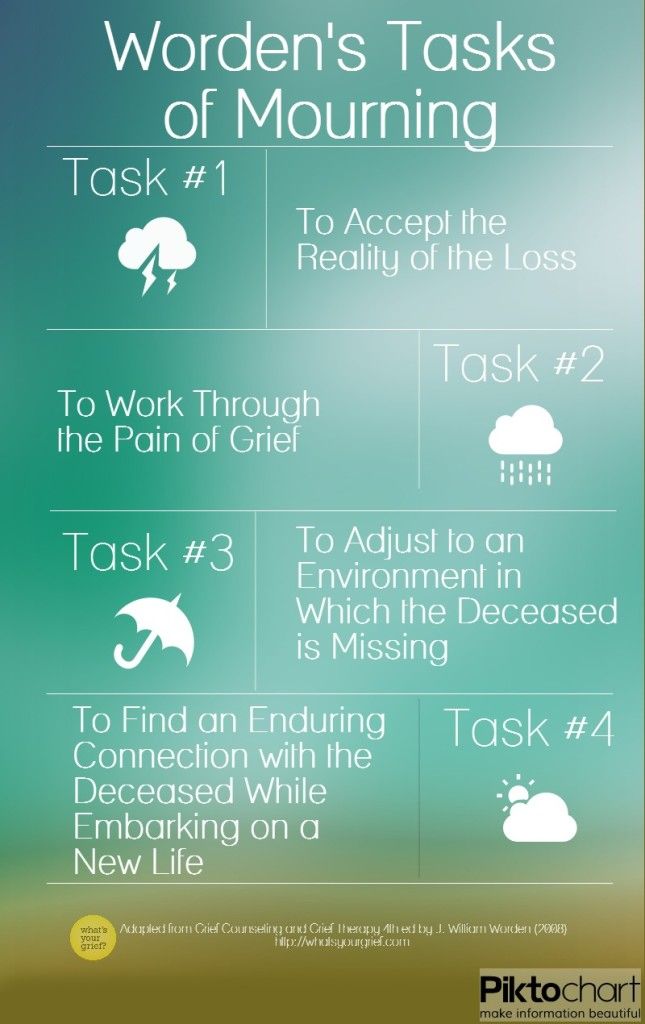

Four tasks of grief | Journal of Practical Psychology and Psychoanalysis

Year of publication and journal number:

2001, №1-2

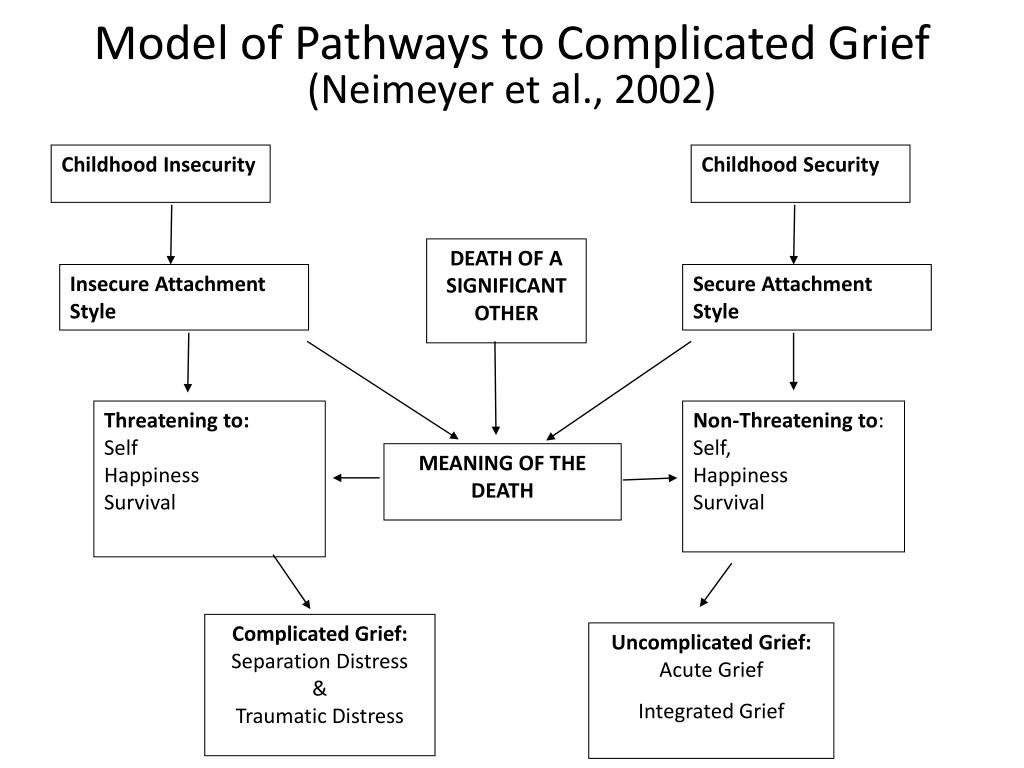

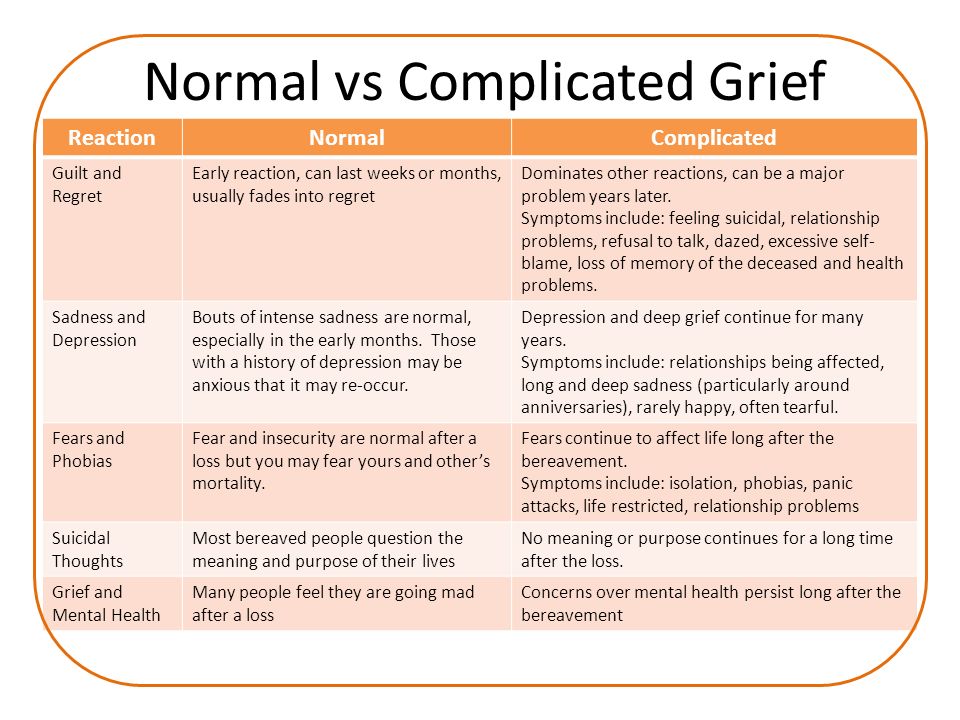

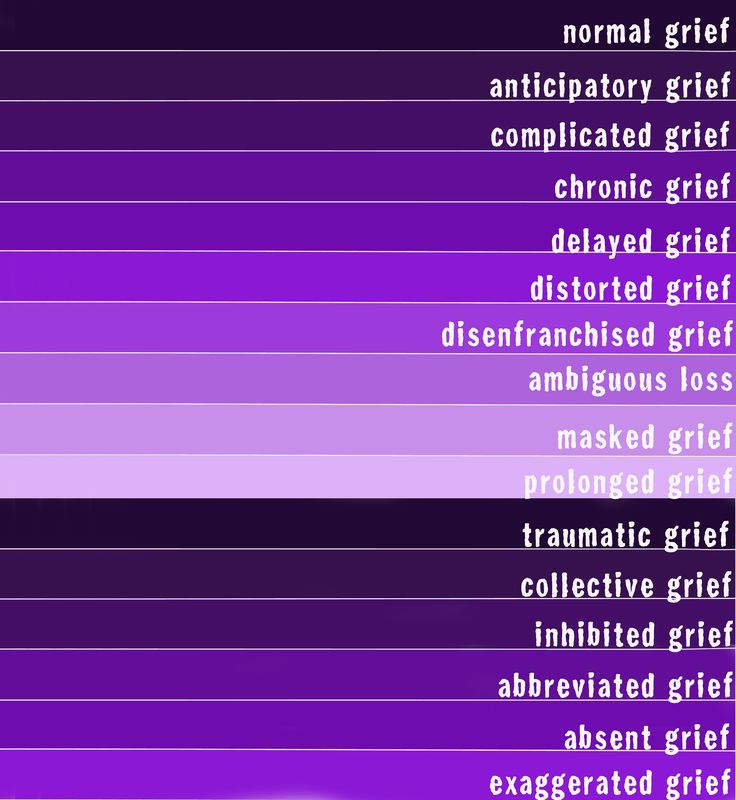

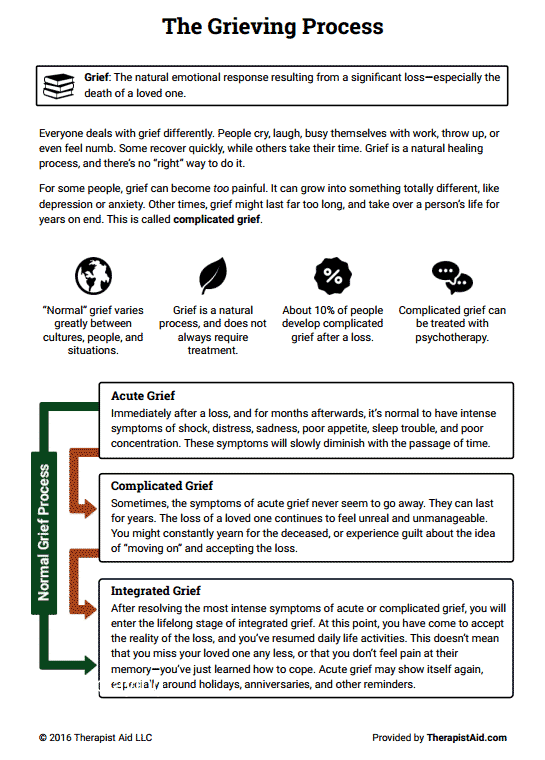

Grief is a reaction to the loss of a significant object, part of an identity, or an expected future. It is well known that the reaction to the loss of a significant object is a specific mental process that develops according to its own laws. The essence of this process is universal, unchanging and does not depend on what exactly the subject has lost. The experience of grief always proceeds in the same way. Only its duration and intensity differ, which depend on the significance of the lost object and on the personality traits of the grieving person. Many attempts have been made to describe the process of grief in a formal way in order to facilitate practical work with it.

The experience of grief always proceeds in the same way. Only its duration and intensity differ, which depend on the significance of the lost object and on the personality traits of the grieving person. Many attempts have been made to describe the process of grief in a formal way in order to facilitate practical work with it.

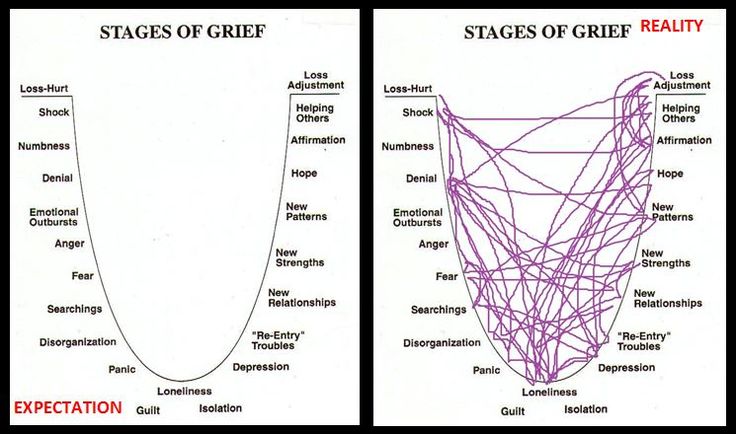

Initially, they tried to describe grief as a series of successive stages. The number of stages in different authors ranged from four to twelve. The therapist was supposed to help the client move from stage to stage. However, as it turned out, the stages do not have clear boundaries and sometimes an already lived stage gives relapses at later stages. In addition, sometimes certain stages were missing or were so poorly expressed that they could not be traced and worked out accordingly. In addition, the manifestations of grief at all stages are very individual, therefore, it often remained unclear where the efforts of the psychotherapist should be directed. All this made the practical application of these descriptions of the grief process difficult and inconvenient.

J. William Vorden's new approach to dealing with a grieving client has recently become widespread. Worden's concept, while not the only one, remains the most popular among people working with loss today. It is very convenient for diagnosing and working with actual grief, as well as if you have to deal with grief that was not experienced many years ago and was revealed during therapy started at a completely different request.

Vorden proposed a variant of describing the grief reaction not in terms of stages or phases, but in terms of four tasks that must be performed by the mourner during the normal course of grief. These tasks are essentially similar to those tasks that a child solves as he grows up and separates from his mother. Vorden considers this approach to be the most convenient for clinicians and the closest to Freud's theory of grief at work.

Vorden believes that although the forms of grief and their manifestations are very individual, the immutability of the content of the process allows us to highlight those universal steps that the mourner must take in order to return to normal life, and to the implementation of which the attention of the therapist should be directed. The tasks of grief are unchanged, because they are determined by the process itself, and the forms and methods of their solution are individual and depend on the personal and social characteristics of the grieving person. Four tasks of grief are solved by the subject sequentially. This is convenient for diagnosis, since it is much easier to understand which psychological problem has been solved and which has not, than to determine a poorly expressed stage of grief. In addition, since it is clear that there is a solution to this problem, it is clear where the psychotherapeutic process should be directed.

The tasks of grief are unchanged, because they are determined by the process itself, and the forms and methods of their solution are individual and depend on the personal and social characteristics of the grieving person. Four tasks of grief are solved by the subject sequentially. This is convenient for diagnosis, since it is much easier to understand which psychological problem has been solved and which has not, than to determine a poorly expressed stage of grief. In addition, since it is clear that there is a solution to this problem, it is clear where the psychotherapeutic process should be directed.

If the tasks of grief are not solved by the grieving person, the grief will not develop further and tend to end, therefore, problems may arise in connection with this even after many years. The grief reaction can be blocked on any of the tasks, and behind this there can be a different level of pathology. Stopping the reaction at the stage of solving each of the problems of grief has certain symptoms.

In this article, I would like to make a summary of the four tasks that the grieving person must solve, based mainly on Warden's seminal book Counseling and Grief Therapy, using the example of the reaction to the death of a loved one. This example most fully illustrates the reaction of loss, and it is important to remember that any reaction of loss will always develop in a similar way in content, only the duration and intensity differ. The forms of manifestation of the process are purely individual.

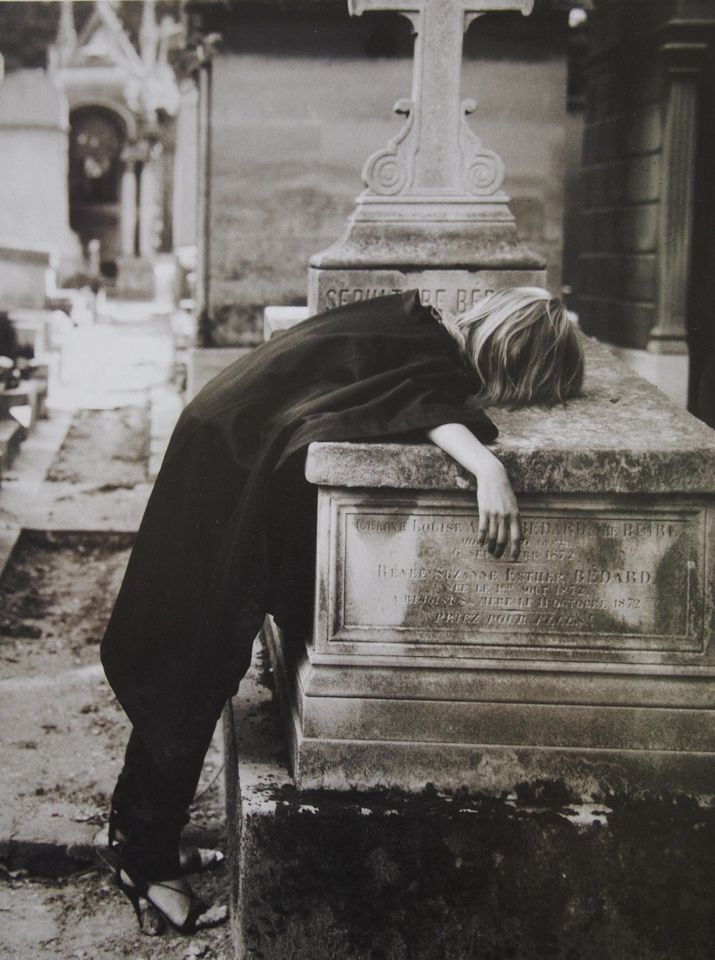

So, obviously, it is impossible to begin to experience loss until the very fact of loss is recognized. Thus, the first task is recognition of the fact of the loss of .

When someone dies, even in the event of an expected death, it is normal to feel as if nothing has happened. Therefore, first of all, you need to recognize the fact of loss, to realize that a loved one has died, he left and will never return. During this period, just as a lost child is looking for a mother, a person mechanically tries to get in touch with the deceased - mechanically dials his phone number, "sees" among passers-by on the street, buys food for him, etc. This "searching" behavior described by Bowlby and Parks is aimed at reconnecting. Normally, this behavior should be replaced by behavior aimed at refusing to communicate with the deceased loved one. A person who performs the actions described above normally catches himself and says to himself: "What am I doing, because he (she) is dead." Quite often there is the opposite behavior - denial (denial) of what happened. If a person does not overcome denial, then the work of grief is blocked in the earliest stages. Denial can be used at different levels and take many forms, but generally involves either denying the fact of the loss, or its significance, or irreversibility.

This "searching" behavior described by Bowlby and Parks is aimed at reconnecting. Normally, this behavior should be replaced by behavior aimed at refusing to communicate with the deceased loved one. A person who performs the actions described above normally catches himself and says to himself: "What am I doing, because he (she) is dead." Quite often there is the opposite behavior - denial (denial) of what happened. If a person does not overcome denial, then the work of grief is blocked in the earliest stages. Denial can be used at different levels and take many forms, but generally involves either denying the fact of the loss, or its significance, or irreversibility.

Loss denial can range from mild to severe psychotic, where the person spends several days in the apartment with the deceased before noticing that the person has died. Gardiner and Pritcher described six such cases as extreme forms of the psychotic reaction to death.

The most common and less pathological form of manifestation of denial was called mummification by the English author Gorer. In such cases, a person keeps everything as it was with the deceased, in order to be ready for his return all the time. For example, parents keep the rooms of dead children. This is normal if it does not last long, thus creating a kind of "buffer" that should soften the most difficult stage of experiencing and adjusting to the loss. But if such behavior drags on for years, the experience of grief stops and the person refuses to recognize the changes that have occurred in his life, "keeping everything as it was" and not moving from his place in his mourning, this is a manifestation of denial. An even milder form of denial is when a person "sees" the deceased in someone else - for example, a widowed woman sees her husband in her grandson. "Poured grandfather." Such a mechanism can alleviate the pain of loss, but rarely fully satisfies - the grandson is still not a grandfather, and if "he continues to live in children", then you still cannot enter into the same relationship with them (children) as with the deceased.

In such cases, a person keeps everything as it was with the deceased, in order to be ready for his return all the time. For example, parents keep the rooms of dead children. This is normal if it does not last long, thus creating a kind of "buffer" that should soften the most difficult stage of experiencing and adjusting to the loss. But if such behavior drags on for years, the experience of grief stops and the person refuses to recognize the changes that have occurred in his life, "keeping everything as it was" and not moving from his place in his mourning, this is a manifestation of denial. An even milder form of denial is when a person "sees" the deceased in someone else - for example, a widowed woman sees her husband in her grandson. "Poured grandfather." Such a mechanism can alleviate the pain of loss, but rarely fully satisfies - the grandson is still not a grandfather, and if "he continues to live in children", then you still cannot enter into the same relationship with them (children) as with the deceased. And in the end, this situation ends with the acceptance of the reality of loss.

And in the end, this situation ends with the acceptance of the reality of loss.

Another way people avoid the reality of loss is to deny the significance of the loss. In this case, they say things like "we weren't close", "he was a bad father" or "I don't miss him". Sometimes people hastily remove all the personal belongings of the deceased, all that can remind of him is the opposite behavior of mummification. In this way, bereaved ones keep themselves from coming face to face with the reality of loss. Those who exhibit this behavior are at risk of developing pathological grief reactions.

Another manifestation of denial is "selective forgetting". In this case, the person forgets something concerning the deceased. For example, Gorer's client, a 35-year-old man who lost his father at the age of fifteen, could not remember his appearance, not even his height or hair color. After successful grief therapy, he remembered the appearance of his father, lived through all the feelings associated with the loss and was able to return to normal life.

The third way to avoid awareness of the loss is to deny the irreversibility of the loss. Vorden gave an example from his practice - a woman who lost her mother and twelve-year-old daughter in a fire, repeated aloud for two years, like a spell: "I don't want you to die." She spoke as if her loved ones had not yet died and she could save their lives with this spell. Another example is when, after the death of a child, parents console each other - "we will have other children and everything will be fine." It is understood that we will give birth to a dead child again and everything will be as it was. Another variant of this behavior is the fascination with spiritualism. The irrational hope of reuniting with the deceased is normal in the first weeks after the loss, when behavior is directed to reconnect, but if this hope becomes stable, this is not normal. For religious people, this behavior looks a little different, because they have a different picture of the world. Then the critical attitude of the grieving to what is happening will be the norm, he understands that in this life he will never be with the deceased and will reunite with him only after living his life in this world the way a good Christian or a respectable Muslim should live it. This expectation of reunion after death does not need to be destroyed, since it is part of the normal picture of the world of deeply religious people.

This expectation of reunion after death does not need to be destroyed, since it is part of the normal picture of the world of deeply religious people.

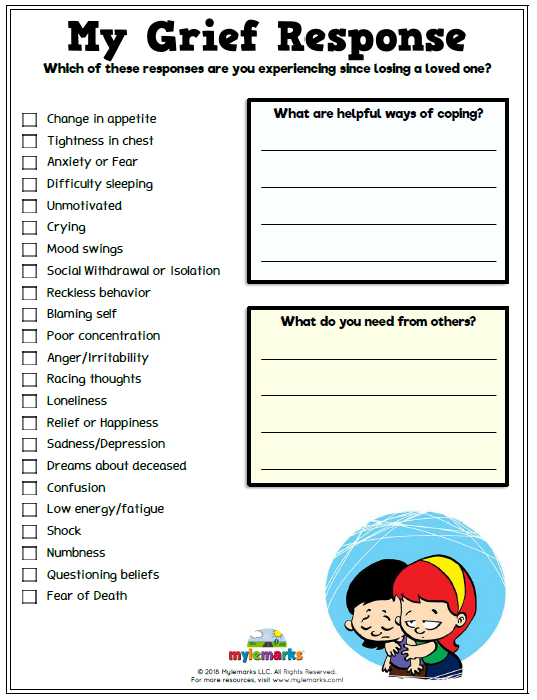

The second task of grief, according to Vorden, is to survive the pain of losing . This means that you need to go through all the complex feelings that accompany the loss.

If a grieving person cannot feel and live the pain of loss, which is absolutely always there, it must be identified and worked through with the help of a therapist, otherwise the pain will manifest itself in other forms, for example, through psychosomatics or behavioral disorders.

Parkes wrote: "If the grieving person must experience the pain of loss in order for the work of overcoming that loss to be done, then anything that avoids or suppresses that pain will prolong the period of mourning." Pain reactions are individual and not everyone experiences pain of the same intensity.

A grieving person often loses contact not only with external reality, but also with inner experiences. “I don’t seem to feel anything, it’s even strange,” “I thought it happens differently, some strong feelings, but here - nothing.” The pain of loss is not always felt, sometimes loss is experienced as apathy, lack of feelings, but it must be worked through.

“I don’t seem to feel anything, it’s even strange,” “I thought it happens differently, some strong feelings, but here - nothing.” The pain of loss is not always felt, sometimes loss is experienced as apathy, lack of feelings, but it must be worked through.

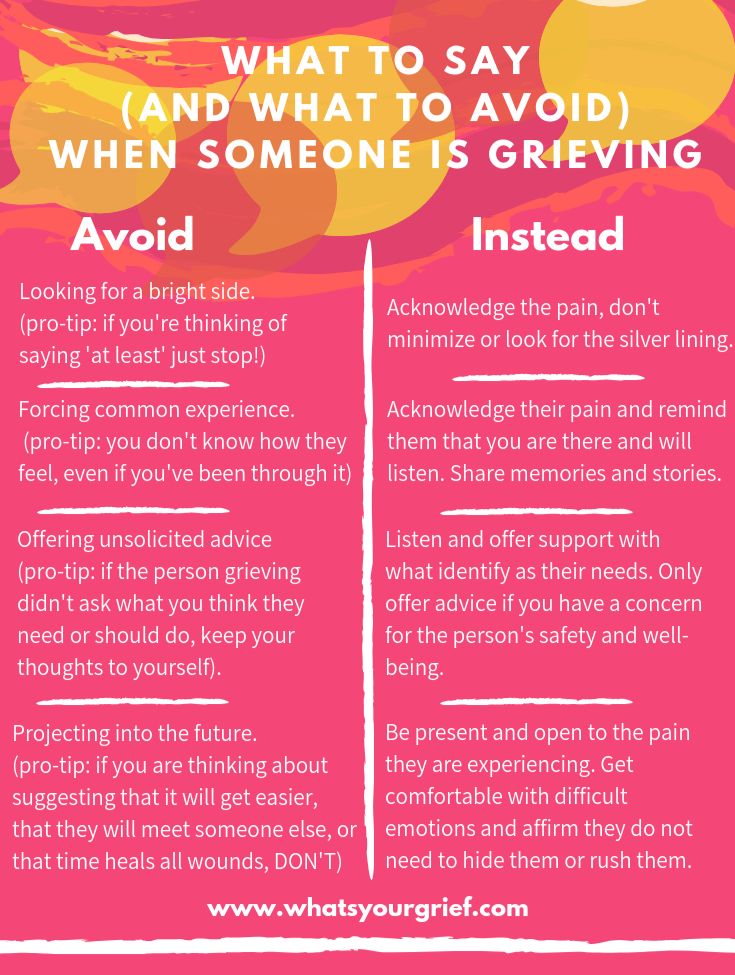

This task is made difficult by others. Often people around are uncomfortable with the intense pain and feelings of the grieving, they do not know what to do with it and consciously or unconsciously tell him: "You should not grieve." This unspoken wish of others often interacts with the bereaved person's own psychological defenses, leading to a denial of the necessity or inevitability of the grief process. Sometimes it is even expressed in the following words: "I must not cry for him" or "I must not grieve", "Now is not the time to grieve." Then the manifestations of grief are blocked, emotions do not react and do not come to their logical conclusion.

The second task is avoided in different ways. This may be denial (negation) of the presence of pain or other painful feelings. In other cases, it may be the avoidance of painful thoughts. For example, only positive, "pleasant", in Vorden's words, thoughts about the deceased, up to complete idealization, can be allowed. It also helps to avoid unpleasant experiences associated with death. It is possible to avoid all sorts of memories of the deceased. Some people start using alcohol or drugs for this purpose. Others use the "geographical way" - continuous travel or continuous work with great tension, which does not allow you to think about anything other than everyday affairs. I know of a case where a man went to work on the day his mother died, even though he was a lecturer. Such public work does not allow you to relax for a second. He did the same on the day of the funeral, and specifically asked to change the schedule. It was a very purposeful behavior to avoid the experience of the mother's death. Parks described cases where the reaction to death was euphoria. Usually it is associated with a refusal to believe that death has occurred and is accompanied by a constant feeling of the presence of the deceased.

In other cases, it may be the avoidance of painful thoughts. For example, only positive, "pleasant", in Vorden's words, thoughts about the deceased, up to complete idealization, can be allowed. It also helps to avoid unpleasant experiences associated with death. It is possible to avoid all sorts of memories of the deceased. Some people start using alcohol or drugs for this purpose. Others use the "geographical way" - continuous travel or continuous work with great tension, which does not allow you to think about anything other than everyday affairs. I know of a case where a man went to work on the day his mother died, even though he was a lecturer. Such public work does not allow you to relax for a second. He did the same on the day of the funeral, and specifically asked to change the schedule. It was a very purposeful behavior to avoid the experience of the mother's death. Parks described cases where the reaction to death was euphoria. Usually it is associated with a refusal to believe that death has occurred and is accompanied by a constant feeling of the presence of the deceased. These conditions are usually unstable. Bowlby wrote: "Sooner or later, everyone who avoids the feelings associated with grief breaks down, most often falling into depression." One of the goals of therapeutic work with loss is to help people solve this difficult task of mourning, to open up and live the pain without collapsing in front of it. It must be lived so as not to be carried through life. If this is not done, therapy may be needed later and it will be more painful and difficult to return to these experiences than to immediately experience them. The delayed experience of pain is also more difficult because if the pain of loss is experienced after a considerable time, the person can no longer receive the sympathy and support from others who usually appear immediately after the loss and who help to cope with grief.

These conditions are usually unstable. Bowlby wrote: "Sooner or later, everyone who avoids the feelings associated with grief breaks down, most often falling into depression." One of the goals of therapeutic work with loss is to help people solve this difficult task of mourning, to open up and live the pain without collapsing in front of it. It must be lived so as not to be carried through life. If this is not done, therapy may be needed later and it will be more painful and difficult to return to these experiences than to immediately experience them. The delayed experience of pain is also more difficult because if the pain of loss is experienced after a considerable time, the person can no longer receive the sympathy and support from others who usually appear immediately after the loss and who help to cope with grief.

This protective behavior has its own reasons, and they need to be dealt with separately before starting to work with feelings. It is necessary to find out the reasons why a person avoids experiences associated with the pain of loss, and first work through them. For example, work with the fear of difficult feelings. In other cases, it is necessary to change the stereotype of behavior associated with the earlier ban on the open expression of feelings, or you need to understand how to deal with the resistance of others who are uncomfortable being close to a person in acute grief.

For example, work with the fear of difficult feelings. In other cases, it is necessary to change the stereotype of behavior associated with the earlier ban on the open expression of feelings, or you need to understand how to deal with the resistance of others who are uncomfortable being close to a person in acute grief.

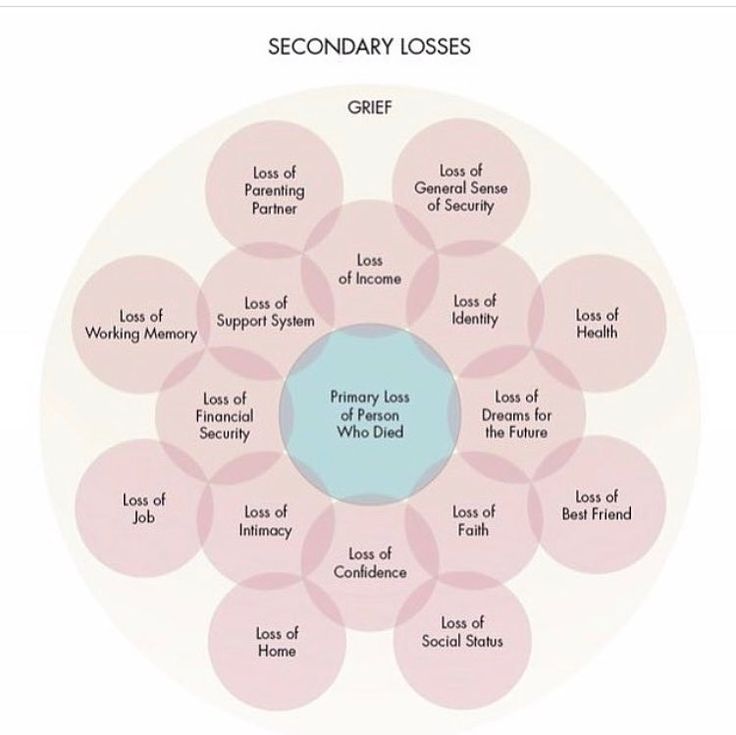

The next task that the mourner must cope with is adjusting the environment where the absence of the deceased is felt. When a person loses a loved one, he loses not only the object to which feelings are addressed and from which feelings are received, he loses a certain way of life. The deceased loved one participated in everyday life, demanded the performance of some actions or certain behavior, the performance of any roles, took on some of the duties. And it goes with him. This void must be filled and life organized in a new way.

Organizing a new environment means different things to different people, depending on the relationship they had with the deceased and the roles the deceased played in their lives. Parkes wrote: “In all mourning, it is not always clear what constitutes a loss. The loss of a husband, for example, may mean, for example, - or not mean - the loss of a sexual partner, companion, accountant, gardener, jester, etc., in depending on the roles that the husband usually performed. The mourner may or may not be aware of the roles that the deceased played in his life. Even if the client is not aware of these roles, the therapist needs to map out for himself what the client has lost and how it can be made up for. Sometimes it's worth talking to the client. Often the client spontaneously starts doing this himself during the session. My client after the death of her mother, feeling very helpless and unprotected, began to reason - what have I lost? An affectionate word, a look, a voice, a touch - yes, this is irreplaceable. But a lot of what my mother did for me and what gave me a sense of security, I can do for myself. I can learn to sew - my mother sewed it, - I can learn to cook and create comfortable conditions for myself when I come home from work - my mother used to meet her with dinner - for example, dinner can be put in the microwave in the morning and all that remains is to press a button .

Parkes wrote: “In all mourning, it is not always clear what constitutes a loss. The loss of a husband, for example, may mean, for example, - or not mean - the loss of a sexual partner, companion, accountant, gardener, jester, etc., in depending on the roles that the husband usually performed. The mourner may or may not be aware of the roles that the deceased played in his life. Even if the client is not aware of these roles, the therapist needs to map out for himself what the client has lost and how it can be made up for. Sometimes it's worth talking to the client. Often the client spontaneously starts doing this himself during the session. My client after the death of her mother, feeling very helpless and unprotected, began to reason - what have I lost? An affectionate word, a look, a voice, a touch - yes, this is irreplaceable. But a lot of what my mother did for me and what gave me a sense of security, I can do for myself. I can learn to sew - my mother sewed it, - I can learn to cook and create comfortable conditions for myself when I come home from work - my mother used to meet her with dinner - for example, dinner can be put in the microwave in the morning and all that remains is to press a button . It helped so much in our work that I started using it as an exercise with other clients. The mourner must acquire new skills. The family can provide support in acquiring them. Vorden cited his client, a young widow, as an example. Her late husband was the type of person who tends to take full responsibility for what is happening and solve all problems on his own. His wife lived with him "like behind a stone wall." Her husband did everything for her. After his death, the widow withdrew and, not knowing how to interact with the outside world and solve problems that arise outside the family world, she practically abandoned social activity. But when one of her children started misbehaving at school, it required her to meet with school staff and social workers. Willy-nilly, she had to overcome her inner resistance and leave the house for the outside world. She learned how to interact with the school staff, solved the problem that arose, and this gave her the necessary experience and the feeling that difficulties of this kind can be overcome.

It helped so much in our work that I started using it as an exercise with other clients. The mourner must acquire new skills. The family can provide support in acquiring them. Vorden cited his client, a young widow, as an example. Her late husband was the type of person who tends to take full responsibility for what is happening and solve all problems on his own. His wife lived with him "like behind a stone wall." Her husband did everything for her. After his death, the widow withdrew and, not knowing how to interact with the outside world and solve problems that arise outside the family world, she practically abandoned social activity. But when one of her children started misbehaving at school, it required her to meet with school staff and social workers. Willy-nilly, she had to overcome her inner resistance and leave the house for the outside world. She learned how to interact with the school staff, solved the problem that arose, and this gave her the necessary experience and the feeling that difficulties of this kind can be overcome. Often, the grieving person develops new ways to overcome the difficulties that have arisen and new opportunities open up before him, so that the fact of loss is reformulated into something that also has a positive meaning. This is a frequent option for successful completion of the third task. For example, a client of mine who lost her mother, with whom she was in a very close symbiotic relationship, once said: "My mother died, and now I began to live. She did not allow me to become an adult, and now I can build my life as I want. I like it."

Often, the grieving person develops new ways to overcome the difficulties that have arisen and new opportunities open up before him, so that the fact of loss is reformulated into something that also has a positive meaning. This is a frequent option for successful completion of the third task. For example, a client of mine who lost her mother, with whom she was in a very close symbiotic relationship, once said: "My mother died, and now I began to live. She did not allow me to become an adult, and now I can build my life as I want. I like it."

In addition to the loss of the object, some people simultaneously experience the feeling of losing themselves, their own Self. Recent studies have shown that women who define their identity through interactions with loved ones or caring for others, having lost the object of care, experience a feeling of losing themselves. Working with such a client should be much more than just developing new skills and the ability to cope with new roles.

Grief often leads a person to a strong regression and the perception of himself as helpless, unable to cope with difficulties and inept, like a child. The attempt to play the role of the deceased may fail, and this leads to even deeper regression and damage to self-esteem. Then you have to work with the client's negative self-image. This takes time, but gradually, relying on a becoming more positive self-image, the client learns to successfully operate in those areas of life that he previously avoided.

The attempt to play the role of the deceased may fail, and this leads to even deeper regression and damage to self-esteem. Then you have to work with the client's negative self-image. This takes time, but gradually, relying on a becoming more positive self-image, the client learns to successfully operate in those areas of life that he previously avoided.

Maintaining a passive, helpless position helps to avoid loneliness - friends and loved ones should help and participate in the life of a bereaved person. At first, after the tragedy, this is normal, but in the future it begins to interfere with returning to a full life. Sometimes inability to adapt to changed circumstances and helplessness serve the family. Other family members must come together to care for someone who has been hit hardest by the loss, and only because of this they feel strong and wealthy. Or the status quo is maintained - the family does not have to change their lifestyle. For example, a grandfather died after a long illness. While he was ill, a certain way of life developed in the family, including caring for the sick, and for some reason this state of affairs suits everyone. In this case, the family begins to disable the widowed grandmother, and with the best of intentions. "You survived such a tragedy. Why do you need to work, we will support you."

While he was ill, a certain way of life developed in the family, including caring for the sick, and for some reason this state of affairs suits everyone. In this case, the family begins to disable the widowed grandmother, and with the best of intentions. "You survived such a tragedy. Why do you need to work, we will support you."

The last, fourth task is to build a new relationship with the deceased and continue to live . In his early writings, Warden formulated this task as "taking the emotional energy out of the old relationship and placing it in the new relationship." However, he later abandoned this formulation, firstly, because of some of its mechanistic nature and, secondly, because it was understood by many as the disappearance of an emotional relationship to a deceased loved one. Therefore Vorden considered it necessary to clarify that the solution of the fourth task does not imply either oblivion or the absence of emotions, but only their restructuring. The emotional attitude towards the deceased must change in such a way that it becomes possible to continue living, to enter into new emotionally rich relationships.

The emotional attitude towards the deceased must change in such a way that it becomes possible to continue living, to enter into new emotionally rich relationships.

Many misunderstand this problem and therefore need therapeutic help to solve it, especially in the event of the death of one of the spouses. It seems to people that if their emotional connection with the deceased weakens, then by doing so they will offend his memory and this will be a betrayal. In some cases, there may be a fear that new close relationships may also end and have to go through the pain of loss again - this is especially common if the feeling of loss is still fresh. In other cases, the fulfillment of this task may be opposed by the close environment, for example, conflicts begin with children in the event of a new attachment from a widowed mother. There is often resentment behind this - a mother has found a replacement for her dead husband for herself, and for a child there is no replacement for a dead father. Or vice versa - if one of the children has found a partner, the widowed parent may have a protest, jealousy, a feeling that the son or daughter is going to lead a full life, and the father or mother is left alone. Often, the completion of the fourth task is hindered by the romantic belief that one loves only once, and everything else is immoral. This is supported by culture, especially in women. The behavior of the "faithful widow" is approved by society. According to the Harvard Grief Study, only 25% of older widows remarried, slightly higher percentage of young widows and widowers. And this despite the fact that 75% of divorced people remarry.

Or vice versa - if one of the children has found a partner, the widowed parent may have a protest, jealousy, a feeling that the son or daughter is going to lead a full life, and the father or mother is left alone. Often, the completion of the fourth task is hindered by the romantic belief that one loves only once, and everything else is immoral. This is supported by culture, especially in women. The behavior of the "faithful widow" is approved by society. According to the Harvard Grief Study, only 25% of older widows remarried, slightly higher percentage of young widows and widowers. And this despite the fact that 75% of divorced people remarry.

This task is interrupted by a ban on love, fixation on a past connection, or avoidance of the possibility of re-experiencing the loss of a loved one. All these barriers are usually accompanied by guilt.

A sign that this task is not being solved, grief does not subside and the period of mourning does not end, there is often a feeling that "life stands still", "after his death I do not live", anxiety grows. The completion of this task can be considered the emergence of a feeling that you can love another person, love for the deceased has not become less because of this, but after the death of, for example, a husband, you can love another man. That it is possible to honor the memory of a deceased friend, but at the same time adhere to the opinion that new friends may appear in life. Vorden cites as an example a letter from a girl who lost her father to her college mother: "There are other people to love. This does not mean that I love my father less."

The completion of this task can be considered the emergence of a feeling that you can love another person, love for the deceased has not become less because of this, but after the death of, for example, a husband, you can love another man. That it is possible to honor the memory of a deceased friend, but at the same time adhere to the opinion that new friends may appear in life. Vorden cites as an example a letter from a girl who lost her father to her college mother: "There are other people to love. This does not mean that I love my father less."

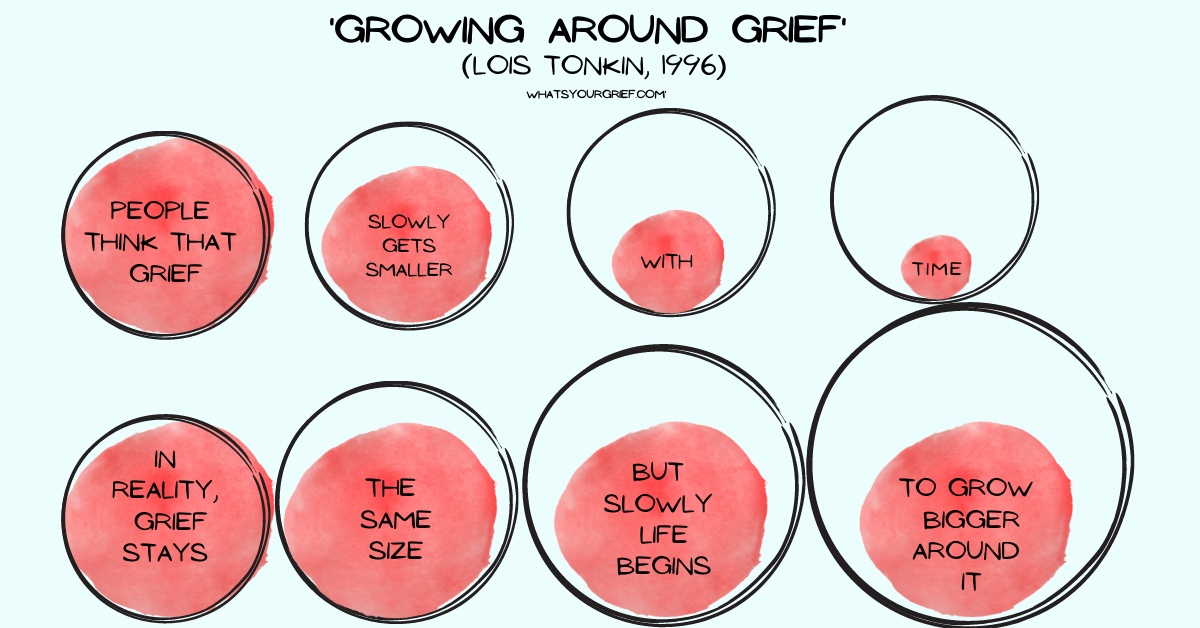

The moment that can be considered the end of mourning is not obvious. Some authors name specific time periods - a month, a year or two. Vorden believes that it is impossible to determine a specific period during which the experience of loss will unfold. It can be considered complete when a person who has experienced a loss has taken all four steps, solved all four tasks of grief. A sign of this, Vorden considers the ability to direct most of the feelings not to the deceased, but to other people, to be receptive to new impressions and life events, the ability to talk about the deceased without severe pain. Sadness remains, it is natural when a person speaks or thinks about someone he loved and lost, but this is already calm, "bright" sadness. The work of grief is completed when the one who has experienced the loss is again able to lead a normal life, he feels adapted, when there is an interest in life, new roles are mastered, a new environment has been created and he can function in it adequately to his social status and character.

Sadness remains, it is natural when a person speaks or thinks about someone he loved and lost, but this is already calm, "bright" sadness. The work of grief is completed when the one who has experienced the loss is again able to lead a normal life, he feels adapted, when there is an interest in life, new roles are mastered, a new environment has been created and he can function in it adequately to his social status and character.

Work of grief — About Palliative

Psychologist Larisa Pyzhyanova herself experienced the loss of loved ones and, working in the Ministry of Emergency Situations, hundreds of times helped people whose relatives died tragically and suddenly. We publish an excerpt from her book “Sharing the pain. The experience of a psychologist from the Ministry of Emergency Situations, which is useful to everyone, ”which tells about what the work of grief is, what processes and why a person experiences after the death of a loved one, how long it can last, what is considered the norm, and what should alert.

The book can be bought on the site of the publishing house "Nikeya".

Crisis of grief

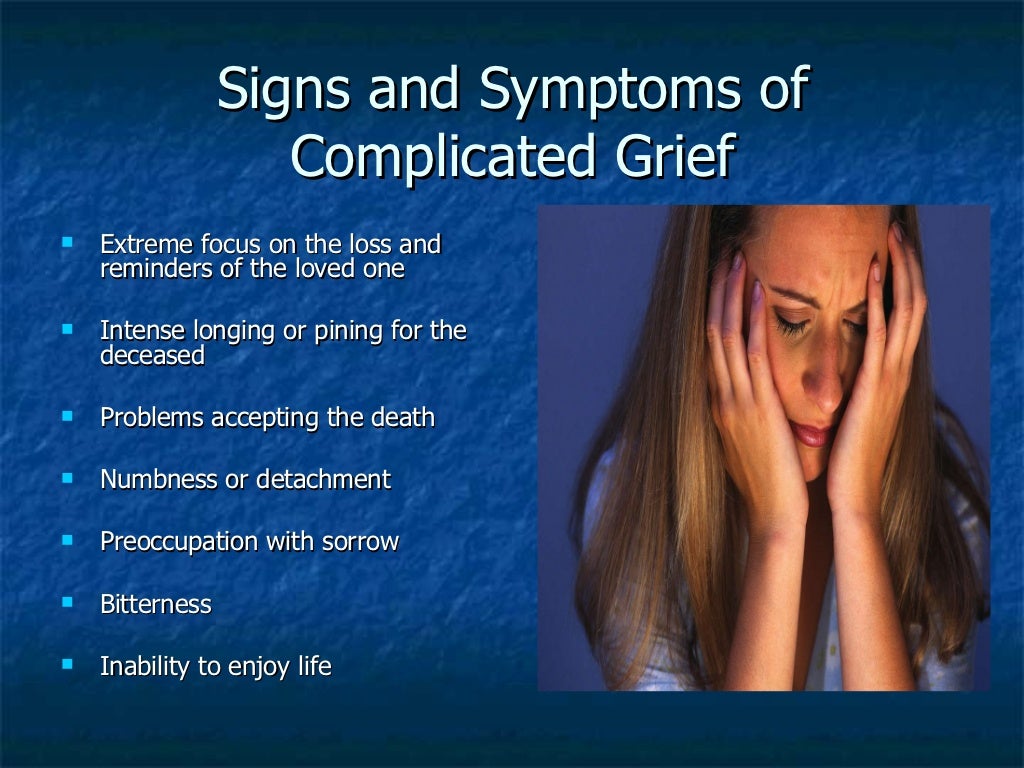

It is impossible to draw a clear framework and determine exactly whether the experience of loss is complicated or not complicated in a person. But still, it is possible to indicate when the process of natural grief goes through certain stages, each of which is characterized by its own set of physical and psychological symptoms.

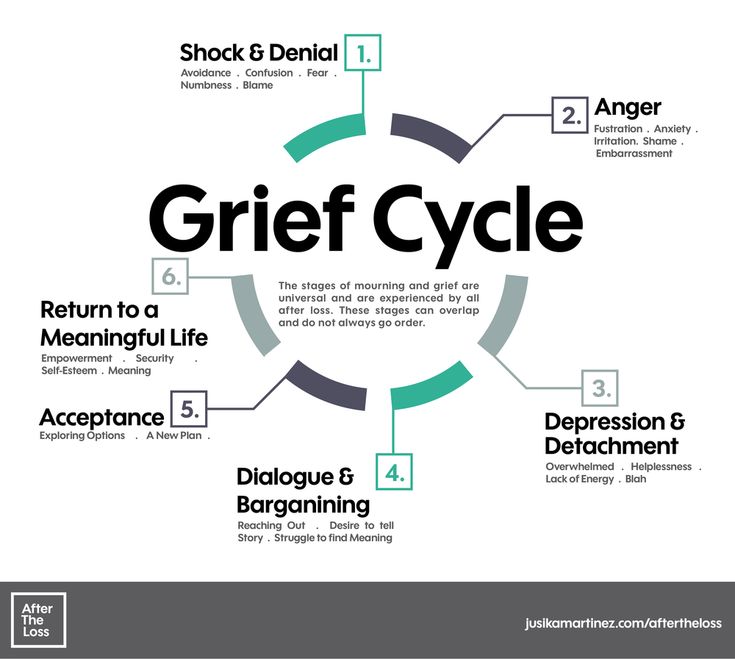

The symptoms of "normal" grief in the middle of the last century were identified by the German-American psychiatrist, a specialist in social psychiatry, Erich Lindemann. The mourning process is divided into two main stages: the grief crisis and the work of grief.

A crisis of grief begins with the death of a loved one or the discovery of an imminent loss, for example, when a loved one is diagnosed with a fatal illness and his days are numbered. Human consciousness rejects the fact of loss, rushes between denial, splitting, persuasion, anxiety and guilt.

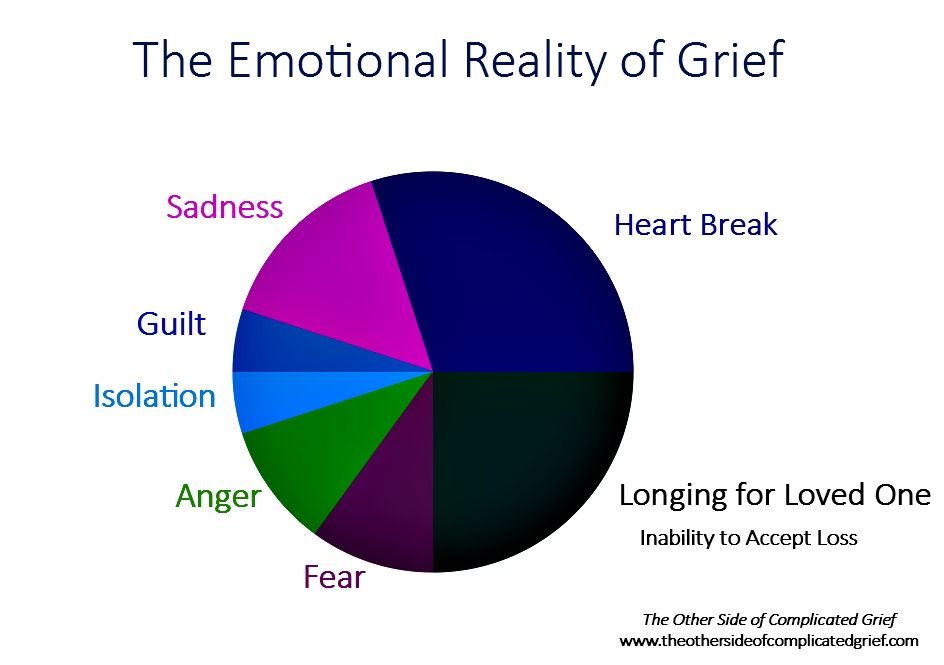

According to Lindemann, the first hours after loss are usually characterized by the presence of periodic bouts of physical suffering, spasms in the throat, fits of suffocation with rapid breathing, a constant need to breathe - this breathing disorder is especially noticeable when a person talks about his grief. At the spiritual level, grief manifests itself as tension or acute suffering. Usually the grieving person feels the unreality of what is happening, deafness, the feeling that everything is happening as if not with him. He has the so-called "tunnel vision", a veil is growing before his eyes. Time speeds up or, conversely, stops. The perception of the surrounding reality is dulled, sometimes in the future there will be gaps in the memories of this period.

Lindemann noted that with a deep emotional experience, changes and disorders of consciousness can be observed. He describes a typical case in which it seemed to the patient that he saw his dead daughter, who was calling him from a telephone booth.

He was so captured by this scene that he stopped noticing his surroundings.

It happens that a grieving person has no manifestations of strong feelings at all. Despite the deceptive external well-being, in reality the person is in a serious condition, and one of the dangers is that at any moment this imaginary calmness can be replaced by an acute reactive state.

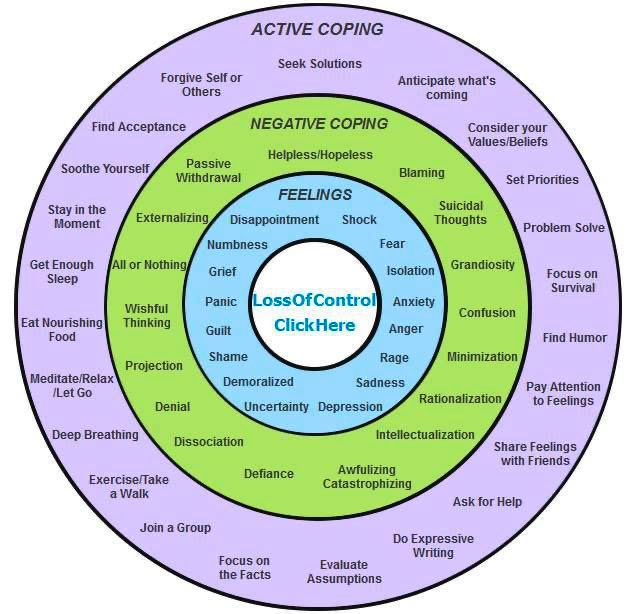

It is possible to single out the mechanisms that are necessary for living through a crisis of grief: denial, splitting, persuasion, anxiety and guilt. When the first shock passes and the person begins to realize the reality of what is happening, the physical reactions weaken, and often there is an acute desire to return everything as it was before the loss. At this time, it seems to people that this is just a bad dream, you just need to wake up, and the nightmare will pass.

The well-known Russian psychotherapist, doctor of psychological sciences, professor Fedor Efimovich Vasilyuk, in his work “Surviving grief”, says that denial at this stage of mourning is not a denial of the fact that the deceased is no more, but a denial of the fact that I, “mourning”, Here. But loss denial allows a person to maintain the illusion that the world remains unchanged. This softens the shock and helps to gradually accept reality, which is facilitated by the rituals of farewell to the deceased adopted in different religions. Such important actions as a funeral service in the church, a memorial meal, help to accept the death of a loved one as a fait accompli.

But loss denial allows a person to maintain the illusion that the world remains unchanged. This softens the shock and helps to gradually accept reality, which is facilitated by the rituals of farewell to the deceased adopted in different religions. Such important actions as a funeral service in the church, a memorial meal, help to accept the death of a loved one as a fait accompli.

Farewell to the deceased Farewell in the mortuary, funeral service, funeral service - what you need to know about them

Without such contact with reality, a person can get stuck in denial of the loss.

This is well illustrated by cases of missing people. Their death is very difficult to accept for loved ones. Splitting allows one part of the mind to know about the loss when the other denies it - this is when a person understands with the mind that a loved one has died, but feels his invisible presence. This is such a common phenomenon that many experts perceive it as part of the normal process of grief - people find comfort in this, the last chance to say goodbye to a loved one.

Vasilyuk writes: “There is… ‘a kind of double being’ (“I live as if on two planes,” says the mourner), where behind the fabric of reality one constantly senses another existence implicitly going through, breaking through islands of ‘meetings’ with the dead. Hope, which constantly gives rise to faith in a miracle, coexists in a strange way with a realistic attitude that guides all the external behavior of the mourner.

Persuasion manifests itself in the resistance of consciousness to what happened in such a way that, trying to deceive fate, as it were, a person concludes an internal deal, again and again remembering the last days, hours before parting, as if wishing to change the course of events: "Oh, if only ... I would give everything so that ... "Grieving people constantly scroll through the events associated with the loss in their heads: they remember what they did not have time to do for the departed; they regret that they paid little attention to him, did not fulfill some requests, were not affectionate enough, did not have time to say “I love”, unfairly offended and did not have time to ask for forgiveness.

When the reality of loss hits people, they experience anxiety and helplessness. For a person who feels very insecure without his loved one, life is full of fears. Sometimes it is, for example, the fear of sleeping in the same bed or room, living in the same house.

The heaviest feeling when experiencing grief is guilt. Sometimes it can be real, more often far-fetched, but it must always be taken with great seriousness. Death exacerbates the problems that have ever taken place in a relationship, and the “stumbling blocks” that were hardly noticeable before turn into an insurmountable obstacle after the death of a loved one. Lindemann describes it this way: “A person who has suffered a loss tries to find in the events that preceded death evidence that he did not do what he could for the deceased. He accuses himself of inattention and exaggerates the significance of his slightest missteps. The person repeats the word "should" like a spell: "I should have done this" or "I should not have done this. " There are many heavy thoughts, a feeling of emptiness and meaninglessness. Over time, a rational explanation of what happened will soften the feeling of guilt, but usually it returns until there is full acceptance of the loss.

" There are many heavy thoughts, a feeling of emptiness and meaninglessness. Over time, a rational explanation of what happened will soften the feeling of guilt, but usually it returns until there is full acceptance of the loss.

Feelings of guilt before a deceased loved one: how to deal with it? When a loved one dies, a feeling of guilt often arises: you didn’t give enough, you didn’t say it, you didn’t do it, and now you can’t fix anything. Is this guilt always just, or is there something else behind it?

Israeli director Shmuel Maoz told an episode from his life. It was about his teenage daughter, who constantly woke up late, missed her school bus, and had to call her a taxi, which cost the family dearly. Once he told his daughter to take the bus, like all children, and if she oversleeps and is late, let this be a lesson for her. The next morning, the girl got up on time, left the house, and half an hour later, her father heard a message that there had been an explosion in this bus - a terrorist attack, dozens of people had died. He rushed to call his daughter, but could not get through. In the next hour, he experienced more than he had experienced in his entire life. And then the daughter returned home alive and unharmed - she still missed that bus. Shmuel Maoz said that later he tormented himself for a long time with the thought that he seemed to have done the right thing, logically, but how would he live if his daughter died?

He rushed to call his daughter, but could not get through. In the next hour, he experienced more than he had experienced in his entire life. And then the daughter returned home alive and unharmed - she still missed that bus. Shmuel Maoz said that later he tormented himself for a long time with the thought that he seemed to have done the right thing, logically, but how would he live if his daughter died?

Probably, this “but” always confronts a person when trouble happens to his loved ones. It seems that he did everything, but ... But he could have done more, better, could have foreseen everything, warned, averted trouble.

The stages of grief come in waves, one wave of denial, splitting, persuasion, anxiety, guilt is rarely enough to accept the loss.

Over time, they change qualitatively and the impulse "I need to call my mother" is gradually replaced by a more urgent need - "I need to be able to call my mother." The weight of the loss begins to be felt. During a crisis of grief, many processes occur at the level of the unconscious; dreams indicate that serious internal work is underway to overcome the feeling of loss. They solve the main task of the crisis of grief - the recognition of the need to accept the death of a loved one.

During a crisis of grief, many processes occur at the level of the unconscious; dreams indicate that serious internal work is underway to overcome the feeling of loss. They solve the main task of the crisis of grief - the recognition of the need to accept the death of a loved one.

Work of grief

The process of mourning is called the work of grief. This is a huge mental work to process tragic events, the main task of which is not to forget, to preserve the memory of a dear person, while building new relationships with a world in which this person no longer exists.

The work of grief begins when a person accepts the fact of death. Then complex processes of overcoming take place, as a result of which the lost relationships gradually become memories, which, ideally, do not completely absorb a person, but transfer grief into a state of light sadness.

It should be noted that with all the variety of Western studies, the experience of grief and loss comes down to one scheme of Sigmund Freud, given by him in Sorrow and Melancholy: "Out of sight, out of mind. " “Freud's theory explains how people forget the departed, but it does not even raise the question of how they remember them. We can say that this is the theory of oblivion,” writes psychotherapist Fyodor Vasilyuk.

" “Freud's theory explains how people forget the departed, but it does not even raise the question of how they remember them. We can say that this is the theory of oblivion,” writes psychotherapist Fyodor Vasilyuk.

In the book of Metropolitan Anthony of Surozh “Life and eternity. 15 Conversations on Death and Suffering” is an important evidence of the attitude towards death of the British: “Here, in England, the attitude towards death is very surprising for a Russian person like me. It has improved somewhat, I dare say, not much, but it has become, let's say, less terrible. And when I first met him, I was amazed. I was under the impression that it was something completely obscene for a good Briton to die, that people should not do this to their friends and relatives, and if they fell so low as to leave this world, they would be hidden in their room until the funeral home will not take them to their place of rest and will not release the family from their presence, because in relation to their relatives a person should not do such an obscene thing as dying.

“Grief is not just one of the feelings, it is a constitutive anthropological phenomenon: not a single most intelligent animal buries its fellows. To bury is to be human. But to bury is not to discard, but to hide and preserve. And on the psychological level, the main acts of the mystery of grief are not the separation of energy from the lost object, but the arrangement of the image of this object for storage in memory. Human grief is not destructive (to forget, tear off, separate), but constructive, it is designed not to scatter, but to collect, not to destroy, but to create - to create memory, ”says Vasilyuk’s work“ Survive Grief.

There are two main components of successful grief work: to re-examine the relationship with the deceased in order to appreciate what they mean to us, and then "translate" them into the category of "memories without a future."

Surviving means realizing what happened, accepting changes in life, adapting to the changed situation and gradually replacing the feeling of suffering and pain with a calm memory.

Freud, in his work "Sorrow and Melancholy", emphasized that we never voluntarily give up our emotional attachments, and that we have been abandoned, rejected or abandoned does not mean that we end relationships with those who did this . After the death of a loved one, we, one way or another, continue to respond to his emotional presence, while realizing that the person is not with us. In order to understand what we lost with the departed and what these relationships were for us, we return to them, look through them over and over again and play them again in memory, dreams, daydreams. Warm memories cause feelings of happiness, unfinished disputes and conflicts make us experience disappointment, anger, sadness again and again. The task of the work of grief is to bring us back again and again to these situations and states until we calmly look at them and accept them as they were.

One of the biggest obstacles to adjusting to a new life, according to Lindemann, is that many people try to avoid the intense pain associated with grief and the emotional expression required for this experience.

That is why painful manifestations are observed in the form of a delay in the reaction or in its various distortions. The ability to perform the work of grief depends on many things, including age, the degree of personal maturity. In the absence of healthy breakups in the past, the work of grief is much slower. Before coming to terms with a new loss, a person is forced to experience the previous unfinished losses.

The work of grief is exhausting. Unconsciously, a person again and again returns to the past and is under its weight. He is constantly faced with loneliness and acute longing. It takes a lot of strength. Time passes, and little by little the demands of the present begin to assert themselves. The person begins to feel the desire to move on. However, a part of him is still gripped by grief. The desire to end the mourning and only from time to time remember the deceased can be unconsciously perceived as a betrayal, cause a feeling of guilt and slow down the processes of grief.

When does grief end?

When grief seems to be over and everything is over, it can sometimes return in the form of acute experiences. In memorable places or on memorable dates. And that's okay.

Let me give you an example from my own life. Two and a half years have passed since my mother's death, and I finally decided to come to her empty apartment to sort things out and prepare the apartment for sale. It seemed to me that I had already experienced everything and accepted everything. My son and I sorted things out, sometimes hovering over something for a long time, sometimes very quickly deciding who to give what to, where to give what. Behind every item were many of my memories. I talked about something, we laughed, joked, sometimes sad, but in general I had the feeling that everything was going well and I was so afraid in vain. And I also thought: “It’s good that my son went with me.” And on the third day, I suddenly had a very familiar and very severe headache, and I said: “How strange, such a state, as if I have been working for an emergency for the third day. ” My son answered me: “And you work for emergency situations.”

” My son answered me: “And you work for emergency situations.”

Loss Oncopsychologist - about personal experience of loss, feelings of guilt and warm memories that illuminate the darkness

Loss can always "come alive" and cause acute pain again, it can return on anniversaries or at moments of important life milestones. But gradually more and more memories appear, freed from pain, guilt, resentment. A person gets the opportunity to escape from the past and turns to the future - he begins to plan his life without the deceased. At this stage, life enters its own track, sleep, appetite, daily activities are restored, the deceased ceases to occupy all thoughts.

The meaning and task of the work of grief is to make a person forgive himself, let go of resentment, and take responsibility for his life. The image of the deceased must take its permanent worthy place in his life, then the person himself will return.

Remembering the deceased, he will no longer experience grief, but sadness - a completely different feeling. And this sadness will forever remain in the heart. If there are tears, they must be wept. But then there comes a time when you can say to yourself: if right now you can restrain yourself and not cry, don’t cry. We must get off the path of tears. If you continue to walk along it, the path can turn into a groove, and then into a trench so deep that it will be impossible to get out of it unless a hand is extended from above. And if you don’t want to reach out in response, then after a while not a single hand will simply be able to reach you - you will be so deep.

Heavy mourning is not a synonym for love, and to stop mourning does not mean to betray the departed. Because it will not go anywhere from the heart, because Love does not go anywhere.

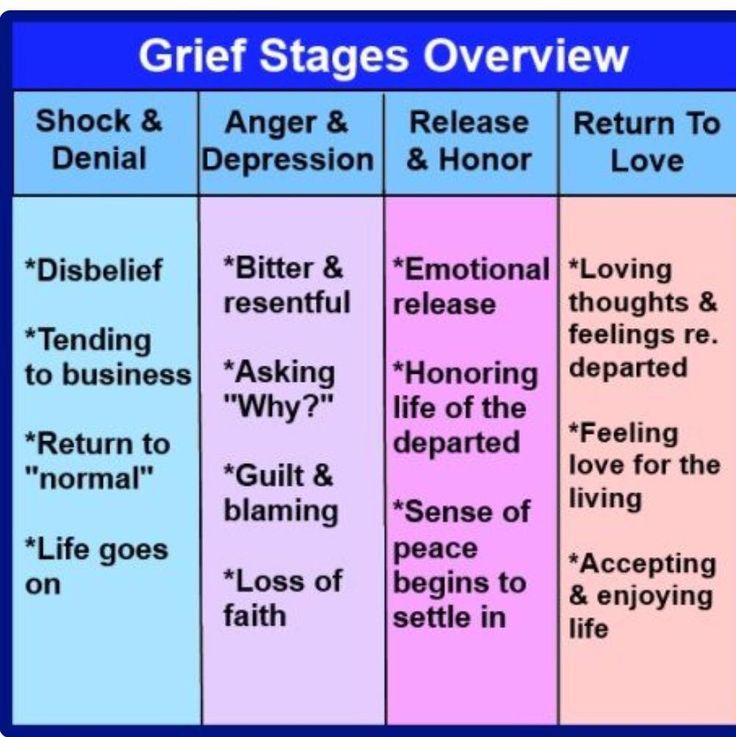

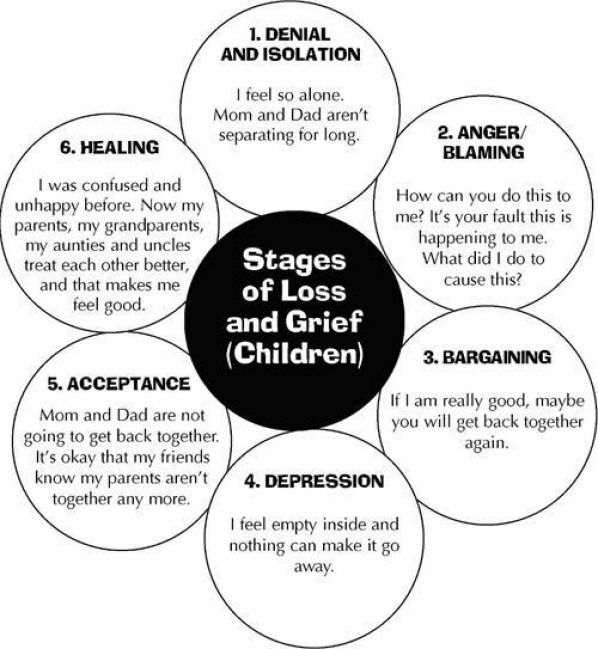

Stages of grief

- Shock and numbness (from a few seconds to several days).

May result in an acute reactive state.

May result in an acute reactive state. - Suffering and disorganization - acute grief (6-7 weeks). Grief work becomes the leading activity.

- Stage of residual shocks and reorganization (up to a year). Loss gradually enters into life.

- Completion (1-1.5 years after loss). Grief is replaced by sadness.

The stage of acute grief may include:

- Denial as a natural defense mechanism to maintain the illusion that the world remains unchanged. It is not the fact of loss that is denied, but its irreversibility.

- Aggression. It is expressed in the form of resentment and hostility towards oneself and others. At this stage, there are reactions of the clinical spectrum.

- Depression. The period of greatest suffering and acute mental pain, the search for the meaning of what happened. Typical is the idealization of the image of the deceased, attributing extraordinary virtues to him. Cooling of relations with others, irritability, desire to retire.

Learn more