Optimism or pessimism

Pessimism vs. Optimism: How Mindset Impacts Wellbeing

Life experiences are interpreted through our own internal filters.

How we explain events to ourselves (i.e., explanatory style) is a key factor in how we respond.

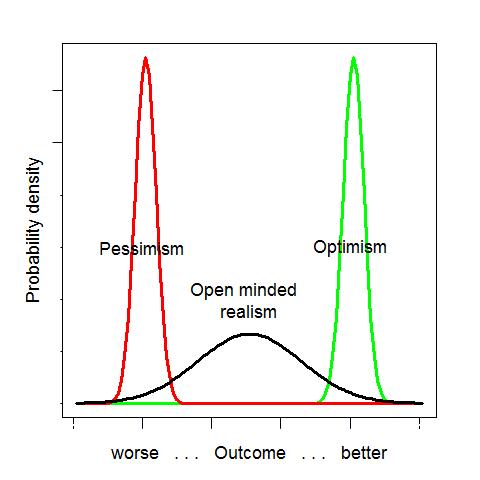

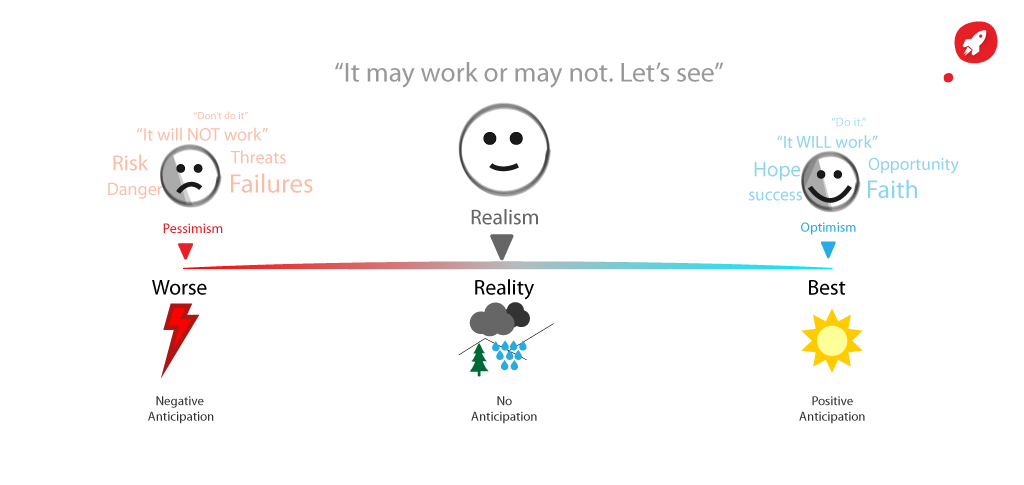

Pessimism, optimism, and realism represent three particularly salient and interconnected explanatory styles.

This article will describe these mindsets and their relationship to psychological health. Tips, books, quotes, and resources from PositivePsychology.com are also included. So please follow along as we inspect how our mindsets influence how we navigate our way through the world.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free. These science-based exercises explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology, including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

- What Is Pessimism in Psychology?

- Pessimism vs Optimism and Realism

- 3 Examples of the Different Mindsets

- The Pessimism Bias: Its Role in Anxiety & Depression

- Can Pessimism Be Good?

- A Note on Changing Your Mindset: 12 Tips

- 3 Books on the Topic

- PositivePsychology.

com’s Resources

- 9 Popular Quotes

- A Take-Home Message

- References

What Is Pessimism in Psychology?

Pessimism is a type of explanatory style in which individuals “expect the disadvantageous outcome when facing events of unknown emotional impact” (Herwig et al., 2010, p. 789).

Humans consistently search for meaning to explain life events. When a person views situations from a pessimistic mindset, this is considered a negative bias (Dember, Martin, Hummer, Howe, & Melton, 1989).

Individuals who are pessimistic will often interpret negative events as internal, global, and stable; whereas positive events are often viewed as external, specific, and unstable (Gillham, Shatte, Reivich, & Seligman, 2001). These relationships are presented in Figure 1 below.

Explanatory style affects many aspects of life. For example, a person with a negative bias is less likely to feel resilient when dealing with stressors because they will feel a lack of personal control.

Viewing undesirable events as due to stable, internal causes has a negative impact on self-esteem (Gillham et al., 2001). In contrast, an optimistic disposition is associated with reduced depression and physical symptoms (Gillham et al., 2001).

Importantly, however, an association between pessimism and negative outcomes is not always straightforward, as it is possible to feel simultaneously pessimistic and optimistic about a situation. Moreover, defensive pessimism may actually be beneficial in some situations.

Figure 1: Relationship between explanatory style, event, and perception

Pessimism vs Optimism and Realism

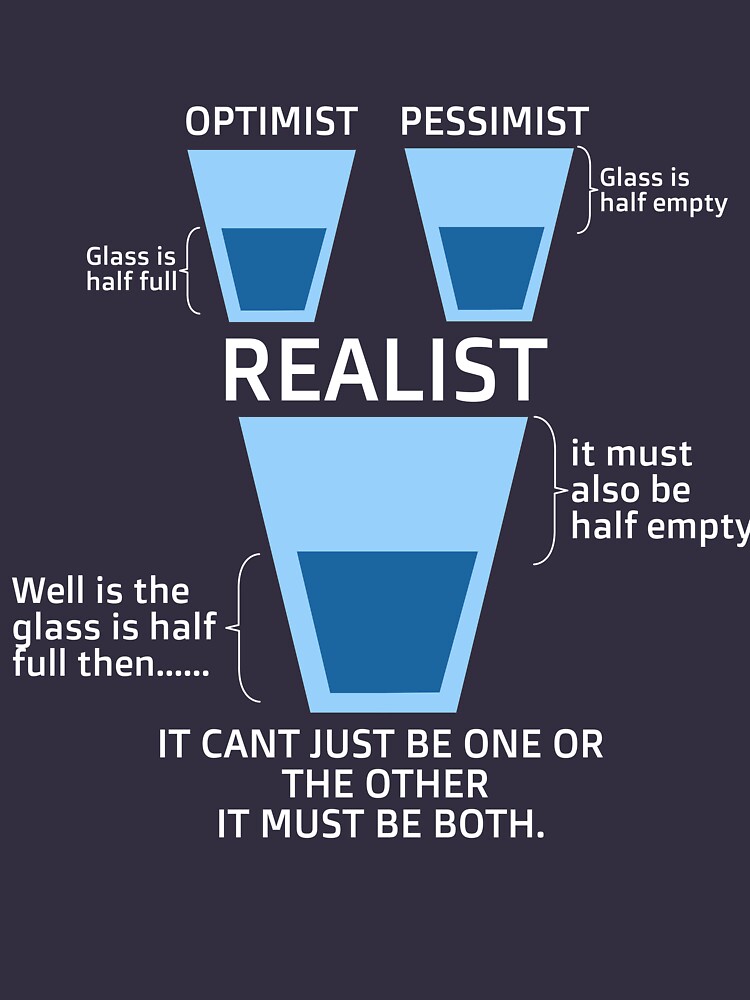

While studies have often reported better outcomes from optimists versus pessimists (Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994), more recent research has also addressed the role of a realistic mindset, in which expectations are based in reality versus fantasy or illusion.

As a notable example, Chipperfield et al. (2019) addressed the role of explanatory styles in an 18-year longitudinal study assessing health expectations and health outcomes among elderly Canadians.

(2019) addressed the role of explanatory styles in an 18-year longitudinal study assessing health expectations and health outcomes among elderly Canadians.

The researchers found that having realistically pessimistic (versus unrealistically optimistic) health expectations was related to both reduced depressive symptoms and risk of death. Similarly, unrealistic optimism (versus realistic optimism) when health is deteriorating was associated with a 313% higher death rate.

Clearly, optimism versus pessimism is not black and white. There is room for realism in this equation; realistic optimism serves a protective function by allowing a person to remain optimistic while accepting the reality of difficult situations.

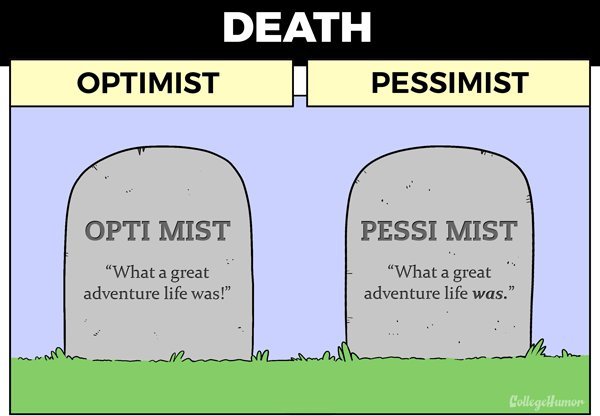

A pessimist sees a dark tunnel.

An optimist sees light at the end of the tunnel.

A realist sees a freight train.

A train driver sees three idiots standing on the tracks.

3 Examples of the Different Mindsets

The following vignettes highlight how mindsets affect how a person responds to a challenging situation.

Stephanie is an active 32-year-old woman who has been feeling fatigued lately, with a great deal of muscle pain and stiffness. She has also noticed that she’s been clumsy, forgetting things, and that one of her eyes is blurry.

When she goes to a specialist, Stephanie is diagnosed with recurring multiple sclerosis (MS), an autoimmune inflammatory disease that causes a wide range of neurological symptoms such as muscle weakness, vision problems, muscle numbness, and difficulty moving. Stephanie’s mindset will play a key role in how she manages her illness as noted below.

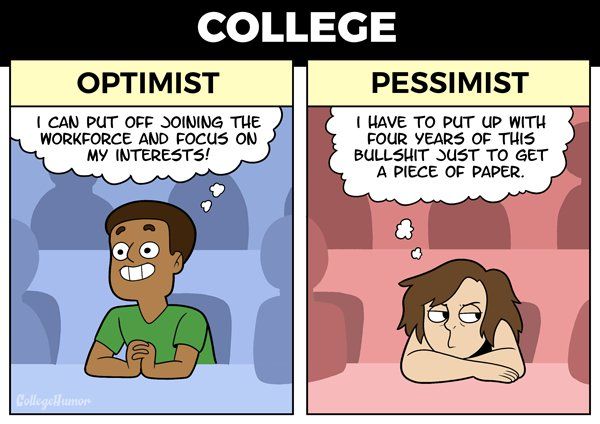

Unrealistically optimistic Stephanie

If Stephanie is unrealistically optimistic, she is likely to view her condition as manageable, stable, and unlikely to worsen. She will not fault herself for her condition and will believe it to be a fluke, since things usually go her way.

Although upset by her diagnosis, she firmly believes that she has the least serious type of MS. She is confident that she will conquer her disease and get on with her life

just as before.

Stephanie immediately begins an anti-inflammatory diet, attends physical therapy, and takes her medicine regularly. Stephanie feels better, but then fails to maintain her lifestyle adjustments because she thinks she’s fine now. As a result, she has a bad flare-up, ends up in the ER, and feels terribly disappointed.

Unrealistically pessimistic Stephanie

If Stephanie is an unrealistic pessimist, she is likely to view life challenges as stable, with this diagnosis serving as no exception. She might believe that the illness is a result of her lifestyle and that she could have prevented it somehow. She believes MS will ruin her life in many areas, such as work and relationships.

Stephanie takes her medicines, but doesn’t engage in physical therapy or change her lifestyle because she feels there’s no point, given that she has a disease she can’t control. Because she doesn’t make necessary health changes, Stephanie’s MS gets much worse, and it’s not long before she finds herself depressed and unemployed..png)

Realistically optimistic Stephanie

If Stephanie is realistically optimistic, she will receive her MS diagnosis with a healthy balance of positivism and acceptance. She will inform herself about the disease and have no illusions about her prognosis. She will take the necessary steps to reduce the impact of the disease and to enable her to maintain a meaningful, healthy lifestyle. She will change her diet and follow all of her doctor’s orders.

Because Stephanie is fully aware of the potential progression of MS, she won’t be knocked down if she has a flare-up. She will face her disease with resilience and will continue to partake in many activities that bring her joy.

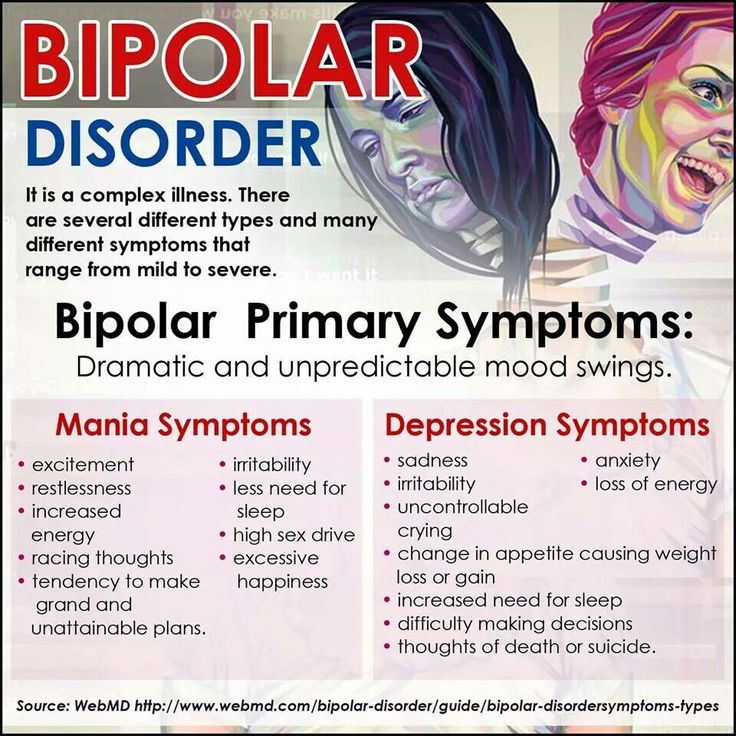

The Pessimism Bias: Its Role in Anxiety & Depression

The ability to anticipate the future has been referred to as “a hallmark of cognition” (Sharot, 2011, p. R941).

Anticipation is necessary for survival, as it enables us to prepare for difficult situations. However, when we make sense of the world through a pessimistic lens, it leaves us vulnerable to anxiety and sadness.

However, when we make sense of the world through a pessimistic lens, it leaves us vulnerable to anxiety and sadness.

If you are depressed, you are living in the past. If you are anxious, you are living in the future. If you are at peace, you are living in the present.

Lao Tzu

Pessimism & anxiety

Let’s first consider anxiety, which generally involves worry, fear, and rumination about the future (i.e., anticipatory anxiety). A highly anxious person often has a stream of what-if’s running through their mind, making it difficult to enjoy the moment.

If a person is pessimistic, they are more inclined to see the worst-case scenario, which only feeds anxiety. Additionally, a person who is chronically anxious is more likely to gauge ambiguous future events as unrealistically negative (Hartley & Phelps, 2012).

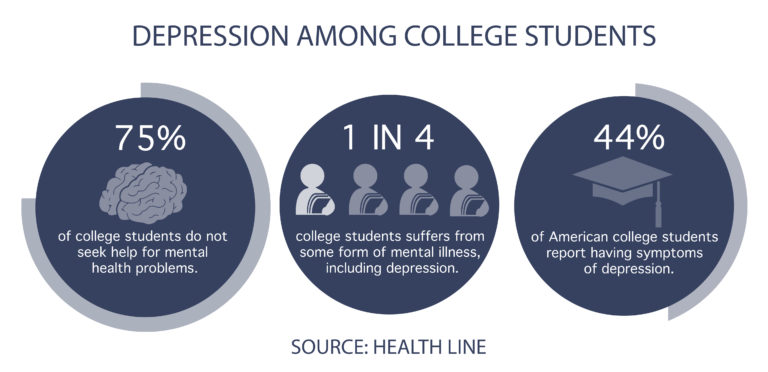

The link between cognitive bias and anxiety has been supported by the literature. For example, optimism has been associated with reduced anxiety and depression among cancer patients (Zenger, Brix, Borowski, Stolzenburg, & Hinz, 2010) and with lower anxiety among college students in both China (Yu, Chen, Liu, Yu, & Zhao, 2015) and India (Singh & Jha, 2013).

Similarly, in a large-scale longitudinal study including Australian adolescents, those who were the most optimistic were almost half as likely to be at risk for depressive symptoms (Patton et al., 2011).

Finally, in their meta-analysis, Alarcon, Bowling, and Khazon (2013) found that optimism was related to many aspects of positive wellbeing, including happiness and life satisfaction. Unsurprisingly, optimism also was negatively correlated with anxiety and depression.

Pessimism & depression

An explanatory style in which negative outcomes are anticipated also represents an integral ingredient of major depression (Herwig et al., 2010). Individuals with depression often feel helpless and don’t believe they have the coping resources to deal with challenges. They may be particularly hard on themselves, engaging in what Aaron Beck (1967, p. 234) has termed “systematic bias against the self.”

A person who is depressed may view themselves in a variety of negative ways that are untrue or grossly amplified (e. g., “I’m no good,” “I’ll never amount to anything,” “I’m worthless”). This pessimistic mindset increases depressive thinking, which serves to exacerbate pessimism. It’s a vicious cycle.

g., “I’m no good,” “I’ll never amount to anything,” “I’m worthless”). This pessimistic mindset increases depressive thinking, which serves to exacerbate pessimism. It’s a vicious cycle.

Empirical research supports a positive relationship between pessimistic bias and depressive symptoms (Strunk, Lopez, & DeRubeis, 2006). Significant associations between optimism and increased resilience and reduced depression among adolescents have also been reported (Niu, Fan, Zhou, Tian, & Lian, 2015).

Similarly, dispositional optimism among college students has been found to predict future depression (Vickers & Vogeltanz, 2000). Among males middle-aged and older, optimism has also been linked to better mental health and vitality (Achat, Kawachi, Spiro, DeMolles, & Sparrow, 2000).

Can Pessimism Be Good?

Like most everything in life, moderation is a key factor when it comes to explanatory style. For example, some people see the world through rose-colored glasses.

In doing so, they fail to notice, much less cope, with challenges. This repressive way of looking at things has drawbacks; just because you refuse to see a problem doesn’t mean it’s not there.

As with the prior example, ‘unrealistically optimistic Stephanie’ fails to comprehend the full nature of her illness, which leads to further health problems and enormous disappointment. Instead, allowing oneself to process the potential ramifications of a situation is a form of mental preparedness that helps to soften the fall during hard times.

The downside of a ‘Pollyanna’ approach is indeed supported by the literature. For example, Chipperfield et al. (2019) found that overly optimistic forecasting was related to reduced psychological wellbeing and a greater risk of death.

Similarly, Forgeard and Seligman’s (2012) review suggests that ‘unmitigated and unrealistic optimism’ may lead to a range of undesirable outcomes. Of course, it’s not healthy to always expect the worst-case scenario, but by nurturing realistic optimism, we can search for “positive experiences while acknowledging what we do not know and accepting what we cannot know” (Schneider, 2001, p. 253).

253).

So, go ahead and practice optimism, but make sure it is balanced with a good dose of flexibility and realism.

A Note on Changing Your Mindset: 12 Tips

Explanatory styles are not fixed aspects of our personality; rather, they are malleable cognitive states.

Here are 12 ways to become more realistically optimistic:

- Change your expectations

How much time and energy is wasted by feeling bad about things and people over which we have no control? Maya Angelou understood this concept when she said: “When someone shows you who they are, believe them the first time.” Imagine how much better you would feel if you simply modified your expectations to be consistent with that which you cannot change. - Enjoy the small things

If you postpone happiness for big events in life, you are limiting your happiness to very few experiences. Consider the smaller, more frequent aspects of life that make you happy and you will reap the benefits.

- Seek beauty

Beauty is subjective. Find what is beautiful to you, such as a sunset or a garden, and savor it. - Visualize positivity

Whether you use a vision board or simply your imagination, by visualizing what you desire, it feels more attainable. - Be realistic

There is a happy medium between pessimism and radical optimism. Be realistic about yourself and the world around you, and it will better prepare you for what tomorrow brings. - Practice gratitude

Gratitude is the antithesis of negativity. Consider and appreciate the great things in your life. - Start the day on a positive note

A day goes more smoothly if it begins with a positive outlook. Remember to start the day with hope and positivity. - Be a positive role model

When you behave like the optimistic person you would like your children, friends, or coworkers to emulate, you are likely to become that person. - Do something creative

Creative flow is a positive and enjoyable experience. Find a creative pursuit you enjoy and your mindset will shift accordingly.

Find a creative pursuit you enjoy and your mindset will shift accordingly. - Don’t be too hard on yourself

Self-love is a key aspect of a positive attitude. If you consistently berate yourself, seek ways to create more kind and loving self-talk. - Practice mindful meditation

This approach enables a person to calm their ‘monkey mind’ and allow unwanted thoughts to float on by. It is an excellent way to minimize the impact of negative thoughts on emotional wellbeing. - Find your ikigai

‘Ikigai’ refers to a reason to live. It is a mindset and lifestyle that involves kindness, community, acceptance, beauty, healthy behaviors, and living in the moment. If you find your ikigai, you are far more likely to experience joy, excellent health, and a zest for life.

3 Books on the Topic

There is plenty of reading material that promotes a healthy explanatory style; here are three examples:

1.

Don’t Sweat the Small Stuff… And It’s All Small Stuff – Richard CarlsonThis highly successful book provides several simple ways to avoid overblowing difficult situations. By maintaining perspective, readers are better able to minimize anxiety.

By maintaining perspective, readers are better able to minimize anxiety.

Among the book’s many insights, readers are advised to trust their intuitions, focus on one thing at a time, and reframe challenges as teaching opportunities.

Find the book on Amazon.

2.

Learned Optimism – Martin SeligmanAuthored by a renowned expert in positive psychology, this informative book is the product of over 20 years of research. It contains many simple methods for embracing a constructive explanatory style and learned optimism.

With tips that help to enhance happiness and wellbeing, this book applies to individuals of all ages.

Find the book on Amazon.

3.

A Year of Positive Thinking: Daily Inspiration, Wisdom, and Courage – Cyndie SpiegelThe goal of this book is to help readers develop a more positive mindset by following daily prompts for an entire year.

It contains a full year of tips, exercises, mantras, and other techniques aimed at promoting positive life changes.

Grounded in psychological research, this inspirational guide provides actionable ways to enhance self-respect, courage, and positivity.

Find the book on Amazon.

PositivePsychology.com’s Resources

You’ll find many materials and further reading throughout our site that can help you or your clients develop a healthy, positive outlook.

Here are just a few links to get you started.

11 Optimism Tools, Examples, and Exercises to Help Improve Your Outlook

This comprehensive article includes information about optimism theory, along with ways to encourage optimism in therapy and among children. It also contains several optimism tests and questionnaires, worksheets, activities, and exercises.

Finding Silver Linings

This exercise helps individuals find the bright side of difficult situations. It contains the following four steps:

- Shift into a positive mindset by listing five things that are meaningful, enjoyable, or worthwhile.

- Identify a recent difficulty by describing a recent event that resulted in distress or frustration.

- Identify costs by writing down the costs associated with the event noted above.

- Find silver linings by listing at least three positive outcomes of the above difficulty.

Overall, by engaging in this exercise for two weeks, readers are more equipped to approach challenges with a positive perspective that promotes resilience.

You can access a pre-prepared version of this exercise, complete with facilitation instructions, with a subscription to the Positive Psychology Toolkit©.

The Yes-Brain Versus the No-Brain

This tool is aimed at helping individuals experience both a ‘yes’ mindset and a ‘no’ mindset in order to learn the benefits of the former. It includes the following four steps:

- Saying ‘No.’ Individuals first engage in a mindfulness exercise in which they become aware of the present moment and what happens within their bodies.

The practitioner then says ‘No’ eight times in a row using a stern, low, hard voice. As this is happening, the client is asked to notice what’s happening in their body.

The practitioner then says ‘No’ eight times in a row using a stern, low, hard voice. As this is happening, the client is asked to notice what’s happening in their body. - Saying ‘Yes.’ Individuals now consider how their bodies respond when the practitioner repeats the word ‘Yes’ eight times in a row, using a warm, encouraging, gentle voice.

- Reflection. Individuals reflect on the prior steps by following prompts, such as “Did you feel differently when hearing ‘No’ and when hearing ‘Yes?’”

- Discussion. The practitioner now describes the client’s reactions in terms of a fight-or-flight response and how it relates to the ‘Yes’ versus ‘No’ brain. Individuals also learn that they can train their brain to become more emotionally stable, resilient, insightful, and empathetic.

By participating in this exercise, individuals are in a better position to foster a more positive and healthy mindset.

Again, you can access a done-for-you template for this exercise, and over 400 more exercises, with a subscription to the Positive Psychology Toolkit©.

17 Positive Psychology Exercises

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others enhance their wellbeing, this signature collection contains 17 validated positive psychology tools for practitioners. Use them to help others flourish and thrive.

9 Popular Quotes

Quotes often represent inspirational tools for embracing an optimistic explanatory style.

Here are nine examples:

Be optimistic like a flower. A flower never loses her optimism and will bloom with all of her beauty despite tremendous adversity.

Debasish Mridha

Optimism is the foundation of courage.

Nicholas M. Butler

Optimism is the madness of insisting that all is well when we are miserable.

Voltaire

The optimism of a healthy mind is indefatigable.

Margery Allingham

A pessimist is a man who thinks everybody is as nasty as himself, and hates them for it.

George Bernard Shaw

If you change the way you look at things, the things you look at change.

Wayne Dyer

Only those who attempt the absurd can achieve the impossible.

Albert Einstein

I’m a pessimist because of intelligence, but an optimist because of will.

Antonio Gramsci

Pessimists try to convince you the world sucks, optimists already know it does and smile anyway.

Jonathan Harnisch

A Take-Home Message

There are many ways to adjust our mindsets to promote a healthy, positive approach to problems.

In fact, a combination of realism and optimism enables us to maintain positivity while bracing ourselves for disappointment.

Fortunately, our explanatory styles can be changed.

There is no reason to hide behind rose-colored glasses; by embracing both reality and optimism, we are able to face life’s inevitable challenges with courage and perseverance.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free.

- Achat, H., Kawachi, I., Spiro, A., DeMolles, D., & Sparrow, D. (2000). Optimism and depression as predictors of physical and mental health functioning: The normative aging study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 22, 127–130.

- Alarcon, G., Bowling, N., & Khazon, S. (2013). Great expectations: A meta-analytic examination of optimism and hope. Personality & Individual Differences, 54, 821–827.

- Beck, A. (1967). Depression: Clinical, experimental and theoretical aspects. Harper & Row.

- Carlson, R. (1997). Don’t sweat the small stuff… And it’s all small stuff. Hyperion.

- Chipperfield, J., Hamm, J., Perry, R., Parker, P., Ruthig, J., & Lang, F. (2019). A healthy dose of realism: The role of optimistic and pessimistic expectations when facing a downward spiral in health.

Social Science & Medicine, 232, 444–452.

Social Science & Medicine, 232, 444–452. - Dember, W., Martin, S., Hummer, M., Howe, S., & Melton, R. (1989). The measurement of optimism and pessimism. Current Psychology, 8, 102–119.

- Forgeard, M., & Seligman, M. (2012). Seeing the glass half full: A review of the causes and consequences of optimism. Pratiques Psychologiques, 18, 107–120.

- Gillham, J., Shatte, A., Reivich, K., & Seligman, M. (2001). Optimism, pessimism, and explanatory style. In E. C. Chang (Ed.). Optimism and pessimism: Implications for theory, research, and practice (pp. 53–75). American Psychological Association.

- Hartley, C., & Phelps, E. (2012). Anxiety and decision-making. Biological Psychiatry, 72, 113–118.

- Herwig, U., Brühl, A., Kaffenberger, T., Baumgartner, T., Boeker, H., & Jäncke, L. (2010). Neural correlates of ‘pessimistic’ attitude in depression. Psychological Medicine, 40, 789–800.

- Niu, G., Fan, C., Zhou, Z., Tian, Y., & Lian, S. (2015). The effect of adolescents’ optimism on depression: The mediating role of resilience. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 23, 709–711.

- Patton, G., Tollit, M., Romaniuk, H., Spence, S., Sheffield, J., & Sawyer, M. (2011). A prospective study of the effects of optimism on adolescent health risks. Pediatrics, 127, 308–316.

- Scheier, M., Carver, C., & Bridges, M. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the life orientation test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 1063–1078.

- Schneider, S. (2001). In search of realistic optimism: Meaning, knowledge, and warm fuzziness. American Psychologist, 56, 250–263.

- Seligman, M. (2006). Learned optimism: How to change your mind and your life. Vintage.

- Sharot, T.

(2011). The optimism bias. Current Biology, 21, R941–R945.

(2011). The optimism bias. Current Biology, 21, R941–R945. - Singh, I., & Jha, A. (2013). Anxiety, optimism and academic achievement among students of private medical and engineering colleges: A comparative study. Journal of Educational & Developmental Psychology, 3, 222–233.

- Spiegel, C. (2018). A year of positive thinking: Daily inspiration, wisdom, and courage. Althea Press.

- Strunk, D., Lopez, H., & DeRubeis, R. (2006). Depressive symptoms are associated with unrealistic negative predictions of future life events. Behaviour Research & Therapy, 44, 861–882.

- Vickers, K., & Vogeltanz, N. (2000). Dispositional optimism as a predictor of depressive symptoms over time. Personality & Individual Differences, 28, 259–272.

- Yu, X., Chen, J., Liu, J., Yu, X., & Zhao, K. (2015). Dispositional optimism as a mediator of the effect of rumination on anxiety.

Social Behavior & Personality, 43, 1233–1242.

Social Behavior & Personality, 43, 1233–1242. - Zenger, M., Brix, C., Borowski, J., Stolzenburg, J., & Hinz, A. (2010). The impact of optimism on anxiety, depression and quality of life in urogenital cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology, 19, 879–886.

The Psychology of Optimism and Pessimism: Theories and Research Findings

Published: 2009-10-24

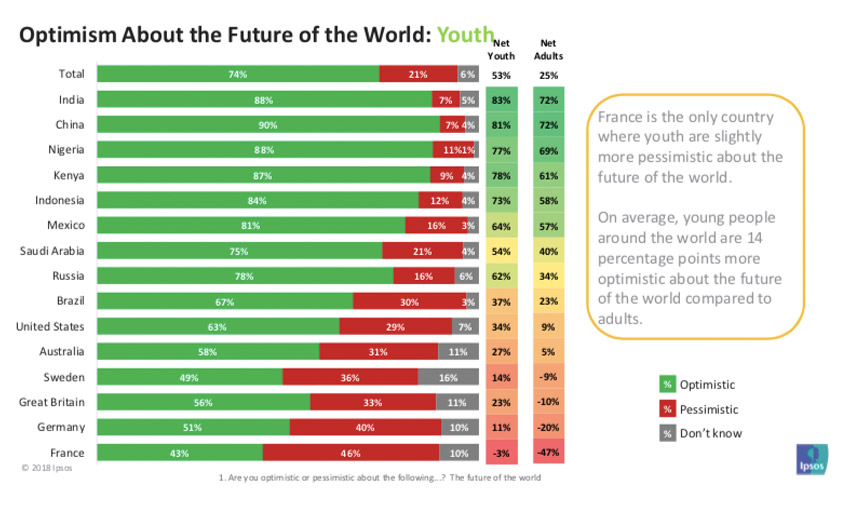

Research in optimism is a burgeoning field. There have been more studies on optimism in the last seven years than in the previous twenty. Reviewing the field of research on optimism, one is at first struck by the overwhelming number of positive outcomes associated with optimism and then by the widespread propensity that humans have for optimism or for a positive bias in their outlook on life and their self assessment.

Psychologists classify the population as largely optimistic by their measurements. i.e. Segerstrom (2006) claims some 80% of people are classified as optimistic, and Seligman (1990) claims 60% of people are somewhat optimistic. Optimism has been highlighted as being an important evolutionary part of survival. In his book Optimism: The Biology of Hope, Tiger (1979) argued that it is one of our most defining and adaptive characteristics.

Optimism has been highlighted as being an important evolutionary part of survival. In his book Optimism: The Biology of Hope, Tiger (1979) argued that it is one of our most defining and adaptive characteristics.

Research has shown that optimism is correlated with many positive life outcomes including increased life expectancy, general health, better mental health, increased success in sports and work, greater recovery rates from heart operations and better coping strategies when faced with adversity.

In order to evaluate whether this research has indeed proven that optimism is such a positive virtue, we need to understand the historical background that gave rise to the first wave of studies into optimism.

Optimism had historically had a view of being associated with simplistic and unrealistic people, perpetuated more in literature (i.e. Voltaire 1700s, Porter’s Pollyanna), and in Freud’s psychoanalytical theorising (optimism was illusory denial) than in psychological fact.

As is often the case in all emerging fields, the pendulum strikes one way, then the other and then settles somewhere in the middle. This article argues that this is what has happened in the research documenting the effects of optimism.

The first wave of research focused on defining optimism and creating measurement tools. This then allowed researchers to investigate what optimistic people could do and would do. The resulting studies showed an almost startlingly positive picture in favour of the benefits of an optimistic outlook, whether this is dispositional (Carver and Scheier) or the way we explain events that happen to us (Seligman and Peterson).

This coupled with the work of Shelley Taylor who argued strongly in her book Positive Illusions (1989) that positive distortions of personal attributes, mastery and assessment of the future are widespread and actually the sign of healthy, well adjusted people, heralded optimism as a desirable and positive trait.

Carver and Scheier -Dispositional Optimism

Charles Carver and Michael Scheier coined the term ‘dispositional optimism’ to describe their approach – the global expectation that good things will be plentiful in the future and bad things scarce.

They argued that optimism is associated with, and leads to, securing positive outcomes whereas pessimism is associated with greater negative outcomes (Scheier and Carver 1992, Scheier, Carver and Bridges 2001). For example, in studies of young adults, optimism has been found to be associated with greater life satisfaction (Chang, Maydeu-Olivares & D’Zurilla, 1997) whereas pessimism has been found to be associated with greater depressive symptoms (Chang et al 1997).

Carver and Scheier see optimism as dispositional. They have found that optimists report fewer physical symptoms, better health habits and better coping strategies. Even among a group who had experienced the bad outcome of being diagnosed with breast cancer (Carver et al 1997) found that optimistic personality types experienced less distress, engaged in more active coping and were less likely to engage in avoidance or denial strategies.

Explanatory Style

Arising from Seligman’s famous “learned helplessness” research in the 70s and 80s, i.e. the reaction of giving up when faced with the belief that whatever you do does not matter, was the related concept of “explanatory style”. This was developed from the analysis and patterns of how people explained events that happened to them.

Seligman developed this analysis into the field of optimism with several other colleagues. He authored the books Learned Optimism and later The Optimistic Child to highlight the relationship between optimism and pessimism and certain styles of explanatory style. Seligman claimed in the former book,

“An optimistic explanatory style stops helplessness, whereas pessimistic explanatory style spreads helplessness” (p. 15).

Seligman developed attributional retraining to help people “learn optimism”. According to this perspective, those who explain away bad events with internal (caused by themselves), stable (will continue to occur) and global (will happen in other spheres of life) causes are described as pessimistic whilst those who favour external, unstable and specific causes are described as optimistic. (Buchanan &Seligman, 1995)

(Buchanan &Seligman, 1995)

The theory was devised in the context of learned helplessness and, as such, it may rely too heavily on the notion that the absence of pessimism creates optimism. The application of “learned optimism” focuses on reducing helplessness/depression through the cognitive therapy models developed by Beck (1967, 1979) and Ellis (Ellis and Harper, 1975).

These cognitive behavioural techniques may not actually be teaching people “optimism”, but instead may just be reducing pessimism. Peterson, himself a proponent of explanatory style, warns that

“Research on optimism (i.e. optimistic explanatory style) will not be as substantial if it remains closely tied to helplessness theory.” (Peterson, 2006 p. 122)

The Pendulum Swings the Other Way

With so many positive correlates, questions abounded with the corollary raft of research which challenged the notion of the ubiquity of optimism benefits.

These largely fall into three key areas;

The main areas of challenge and qualification were as follows:-

- Questioning the “demonisation” of pessimism

- Challenging the notion rising from explanatory style that optimism can’t be learned

- Highlighting the underbelly or dark side of optimism.

Taking these in detail let us look at each area in turn:

The “Demonisation” of Pessimism

“Pessimism is an entrenched habit of mind that has sweeping and disastrous consequences: depressed mood, resignation, underachievement and even unexpectedly poor physical health.” Seligman states in his 1995 book The Optimistic Child.

A tranche of studies sought to highlight the fact that pessimism had been somewhat demonised as the opposite end of optimism. These fall mainly into 3 camps;

a) Showing that pessimism is not uni-dimensional with optimism but a separate construct, and as such does not always have the negative outcomes that juxtapose it with optimism’s positive results.

Bromberger and Matthews (1996) found that although pessimism seemed to be associated with greater depressive symptoms and greater negative affectivity in middle aged women, pessimism was not a significant statistical predictor of later depressive symptoms once they had controlled for certain variables.

Studies looking at lung cancer patients (Schofield, Ball, Smith, Barland, O’Brien, Davis et al., 2004) and HIV patients (Tomakowsky et al., 2001, Reed et al., 1994) show no difference between optimistic and pessimistic recovery rates.

b) Some research highlighted that pessimism was actually more of a predictor for certain outcomes than optimism. Peterson and Chang raise the point that upon closer look at many studies the more exact conclusion is that pessimism is associated with undesirable characteristics, not that optimism is associated with positive ones.

Chang (1998) has found that it may be the decreased use of passive and ineffective coping strategies rather than the increased use of active coping efforts that distinguishes dispositional optimism and pessimism.

c) Some studies have even proven that indeed there are times when pessimism paid off. Norem and Cantor (1989) highlight defensive pessimism as a coping style, which focuses around a specific context. They looked at academic performance. The defensive pessimist in this context is one who anticipates and worries about a poor result despite a prior good track record.

They looked at academic performance. The defensive pessimist in this context is one who anticipates and worries about a poor result despite a prior good track record.

This is perceived as self protective and thus defensive in two ways, either acting as a buffer if it turns out to be right, or acting as a spur into action. The result is that defensive pessimists tend to perform as well as academic optimists. Interestingly however, this is not true over the long term. After 3 years the defensive pessimists were no longer performing as well as the optimists, and moreover were reporting less life satisfaction and more psychopathological symptoms.

Can Optimism Be Learned?

Seligman’s work with the Penn Resiliency Programme, and the programme outlined in his books, Learned Optimism and The Optimistic Child suggested optimism can be learned, but whether this was learning optimism or reducing pessimism is a point to consider. The programme was based on Beck and Ellis’s cognitive behavioural techniques devised to conquer depression.

The concept of psychological immunity to depression is an exciting concept. However, the learned optimism programme as it stands may be more focused on stopping pessimism than enhancing optimism which is its own and different skill. Furthermore, in the specific area of learning optimism amongst children, there have been eleven replications, of which eight replicated the results, whilst three found no effects. Whilst the results are impressive in the studies that work (depression significantly reduced in children taught the optimism programme) and with no boosters the optimistic child programme prevents depression for two years.

However, by the third year the prevention effects fade (Gillham and Reivich et al, 1995) .Segerstrom’s recent work, highlighted in her book Breaking Murphy’s Law (2006), demonstrates the connection between optimists and their investment in goal setting and perseverance in attainment. Segerstrom argues that learning strategies that create the benefits associated with optimists are achievable.

She cites evidence that shows that optimistic people pursue their goals more doggedly, leading them to build resources through goal pursuit or effective coping with stress. Segerstrom (2006) seems dismissive of the link between explanatory style and learning optimism

“Although this trait and dispositional optimism share the optimism label they are actually fairly unrelated to each other.“

The Dark Side of Optimism

Other research has proven that optimism has a dark side too and that there are potential pitfalls to an optimistic personality. Robins and John (1997) have found that optimistic illusions of performance are more likely to be associated with narcissism than mental health.

This research challenges the notion that optimism as a precursor for a happy and successful life is a given. This area of research shows examples where optimism has proven to have poor outcomes. Another angle has been in “quantifying” optimism, proving the hypothesis that too much of a supposed good thing can be bad for you.

In his studies of unrealistic optimism, Weinstein (1989, 1984, Weinstein and Kliein, 1996) has proved evidence of the harmful effects of optimistic biases in risk perception related to a host of health hazards. Those who underestimate the risk, take less action.

For example, Weinstein, Lyons, Sandman, and Cuite (1998) found that those who underestimated the risk of radon in their homes were less likely than others to engage in risk detection and risk reduction behaviours.

The pendulum is swinging back now into a healthy middle ground which requests depth rather than breadth of study. The last decade has brought us research that is more sophisticated in terms of its preciseness in measurement. There is now a general acceptance that optimism is separate from extraversion and neuroticism and positive effect.

Carver and Scheier conclude that neuroticism is the most interesting and may hold sub-points connected to optimism and pessimism which they encourage researchers to analyse. The evidence strongly supports the notion that optimism is a strong predictor for positive outcomes even when controlling for mood, affect, and other personality dimensions.

The evidence strongly supports the notion that optimism is a strong predictor for positive outcomes even when controlling for mood, affect, and other personality dimensions.

More studies show positive outcomes than not, and no studies to date have shown pessimism as a predictor for healthy outcomes related to physical health.

Research is encouraging that, whilst optimism may be dispositional, it can indeed be learned. It has less inherited aspects than some of the other dispositional traits and as such is responsive to interventions. Segerstrom asserts her thesis in her book Breaking Murphy’s Law, “The thesis of this book is that optimists are happy and healthy not because of who they are but because of how they act” (p.167).

Optimism is more what we do than what we are, and thereby can be learned. This has exciting implications for application and interventions.

References and Further Reading:

Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: Clinical, experimental and theoretical aspects. New York: Hoeber.

T. (1967). Depression: Clinical, experimental and theoretical aspects. New York: Hoeber.

Bromberger JT, Matthews KA. (1996). A longitudinal study of the effects of pessimism, trait anxiety, and life stress on depressive symptoms in middle-aged women. Psychology & Aging, 11, 001–007.

Buchanan, G. M., & Seligman, M. E. P. (Eds.). (1995). Explanatory style. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum

Carver, C. S., & Gaines, J. G. (1987). Optimism, pessimism, and postpartum depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 11, 449-462.

Chang, E. C. (1998a). Dispositional optimism and primary and secondary appraisal of a stressor: Controlling for confounding influences and relations to coping and psychological and physical adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1109-1120.

Chang, E. C. (1998b). Distinguishing between optimism and pessimism: A second look at the “optimism-neuroticism hypothesis.” In R. R. Hoffman, M. F. Sherrik, & J. S. Warm (Eds.), Viewing psychology as a whole: The integrative science of William N. Dember (pp. 415-432). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

R. Hoffman, M. F. Sherrik, & J. S. Warm (Eds.), Viewing psychology as a whole: The integrative science of William N. Dember (pp. 415-432). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Chang, E. C., Maydeu-Olivares, A., & D’Zurilla, T. J. (1997). Optimism and pessimism as partially independent constructs: Relations to positive and negative affectivity and psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 23, 433-440.

Ellis, A., & Harper, R. A. (1975).A new guide to rational living. North Hollywood, California: Wilshire Books.

Gillham, J. E., Reivich, K. J., Jaycox, L. H., & Seligman, M. E. P. (1995). Prevention of depressive symptoms in school children: Two-year follow-up. Psychological Science, 6, 343-351.

Norem, J. K., & Cantor, N. (1986). Defensive pessimism: Harnessing anxiety as motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1208-1217.

Peterson, C. (2006). A Primer In Positive Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

A Primer In Positive Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Reed, G. M., Kemeny, M. E., Taylor, S. E., Wang, H. Y. J., & Visscher, B. R. (1994). Realistic acceptance as predictor of decreased survival time in gay men with AIDS. Health Psychology, 13, 299-307.

Robins, R. W., & John, O. P. (1997). The quest for self-insight: Theory and research on accuracy and bias in self perception. In R. Hogan, J. Johnson, & S. Briggs, Handbook of personality psychology (pp. 649-679). New York: Academic Press.

Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1992). Effects of optimism on psychological and physical well-being: Theoretical overview and empirical update. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 16, 201-228.

Scheier, M.F., Carver, C.S., & Bridges, M.W. (2001). Optimism, pessimism, and psychological well-being. In E.C. Chang (ed.), Optimism and pessimism: Implications for theory, research, and practice (pp. 189-216). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Schofield, P., Ball, D., Smith, J. G., Borland, R., O’Brien, P., Davis, S., et al. (2004). Optimism and survival in lung carcinoma patients. Cancer, 100, 1276-1282.

Seligman, M. E. P. (1990). Learned Optimism. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc

Segerstrom, Suzanne C. (2006). Breaking Murphy’s Law. New York: The Guildford Press.

Taylor, S. E. (1989). Positive Illusions :creative self-deception and the healthy mind. New York: Basic Books.

- Tiger, L. (1979). Optimism: the biology of hope. New York, Simon & Schuster, Inc.

- Tomakowsky, J., Lumley, M. A., Markowitz, N., & Frank, C. (2001). Optimistic explanatory style and dispositional optimism in HIV-infected men. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 51, 577-587.

Weinstein, N. D. (1980). Unrealistic optimism about future life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 806-820.

Weinstein, N.D. (1984). Why it won’t happen to me: perceptions of risk factors and susceptibility. Health Psychology, 3, 431-457.

Weinstein, N. D. (1989). Optimistic biases about personal risks. Science, 246, 1232-1233.

Weinstein, N.D. & Klein. (1996). Unrealistic optimism: present and future. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 15, 1-8.

Weinstein, N.D., Lyons, J.E., Sandman, P.M., Cuite, C.L. (1998). Experimental evidence for stages of health behaviour change: The precaution adoption process applied to home radon testing. Health Psychology, 17(5), 445-453.

90,000 What do psychological studies say?Headings : Translations, Latest articles, Psychology

Did you find something useful here? Help us stay free, independent and free with any donation:

Donate

Optimism or pessimism, depressive realism or rose-colored glasses, objectivity or flexible thinking? We are publishing a translation of an article from The New Yorker magazine, in which columnist Maria Konnikova says that many years of psychological research shows the pros and cons of pessimism, how depression helps us get rid of the illusion of control that we are all prone to, and why, despite all this, a positive life attitude gives us much more than an objective view of things.

As Ambrose Bierce put it in his The Devil's Dictionary, a cynic is "a scoundrel whose misguided eye sees things as they are and not as they should be." A century after Bierce's death, science agreed with him. Cynicism - in all its guises - makes us look at the world more realistically, although such a view can turn out to be a high price for us.

The phenomenon known to psychologists as "depressive realism" was first discovered by Lauren Alloy and Lyn Abramson, psychologists at Northwestern University and the State University of New York at Stony Brook, who studied the illusion of control: situations in which people seemed to be in control of something when nothing depended on them.

In 1979, they formed two experimental groups: one included students from colleges with depression, the other included students without signs of depression (1). They were given the task of assessing how much they could influence the light, which would either turn on or off when they pressed the button. In fact, there was no exact correspondence between the subject's action and the appearance of light. The light turned on when the participant pressed the button, then when he did not. From experiment to experiment, only the frequency with which the action coincided with the result varied. The researchers found that depressed people were much better at identifying times when they were out of control, while non-depressed students tended to overestimate their influence on the light.

In fact, there was no exact correspondence between the subject's action and the appearance of light. The light turned on when the participant pressed the button, then when he did not. From experiment to experiment, only the frequency with which the action coincided with the result varied. The researchers found that depressed people were much better at identifying times when they were out of control, while non-depressed students tended to overestimate their influence on the light.

The difference became even more interesting when Elloy and Abramson added money to the experiment. In some cases, students' actions were associated with losing. Participants started with five dollars and gradually lost money as the light did not respond to their actions (25 cents for each failed attempt). In other cases, the appearance of the light brought financial benefits: the participants started from scratch, but received twenty-five cents each time the light was turned on. In the end, each person was eliminated when they either lost $5 (in the first situation) or won the money (in the second situation).

When psychologists asked participants how much they were in control of the situation during the entire experiment, those who were not depressed believed that they had more influence on the world than they actually did - but only in winning situations. When these participants lost money, they estimated they were less in control than they really were.

Depressed participants, by contrast, were much more accurate in their judgments about these situations. Thus, Elloy and Abramson suggested that depression prevents an unwarranted illusion of control when someone wins and provides a sense of responsibility when someone loses. Research following Elloy and Abramson's experiments also showed that depressive realism can be the result of general pessimism and yes, cynicism (2, 3).

By 1992, Elloy and Abramson were able to replicate their original findings in multiple contexts and continued the logic of the research (4). It's not just that depressed people are more realistic in their judgments, the scientists say, but that the illusion of control prevalent among non-depressed participants likely protected them from becoming depressed. In other words, looking at the world through rose-colored glasses, no matter how justified, allowed people to maintain a healthy mental state.

In other words, looking at the world through rose-colored glasses, no matter how justified, allowed people to maintain a healthy mental state.

Depression leads to objectivity. Lack of objectivity leads to healthier well-being, greater adaptability and more flexible thinking. A meta-analysis conducted in 2004 by Abramson and colleagues at the University of Wisconsin-Madison confirmed that the positive bias (“positive bias”) is independent of age or ethnicity (5). They concluded that the found and discovered effect "may represent one of the largest effects demonstrated in psychological research on cognition to date."

Why is this so? As it turns out, how we explain the world can have a very real impact on our physical and emotional well-being, both positive and negative. Harvard University psychologist Daniel Gilbert has called this phenomenon the “psychological immune system,” which is the feedback between how we think and how we feel. If we think more optimistically, we tend to feel better, which in turn makes us think more optimistically.

The notion that our outlook on life is linked to our well-being is not new. In the 1960s at the University of Connecticut, psychologist Julian Rotter suggested that we can see/perceive external events in one of two ways: either we believe we are in control of them, or we prefer to think that they are the result of circumstances. She found that successful people tend to repeat the same patterns of behavior. They perceive success as the result of their actions and do not take into account negative results.

See also: Half empty or half full? Developing optimism as a key to future success

Ten years later, psychologists Bobbi Fibel and W. Daniel Hale found that the effect has an even bigger effect: when you think you can do something well (a mentality that scientists call "general attitude to success") - you are likely to be able to avoid negative life scenarios (6). It doesn't matter if you are in control or not, what matters is your belief that only positive things can happen to you. Of course, optimistic people are not immune to lightning strikes and can still be run over by a car, and an overabundance of optimism can lead to extremely negative consequences related to self-confidence, from poor financial decisions to disastrous political blunders. But as Feibel and Hale found, positive expectations tend to lead to positive outcomes.

Of course, optimistic people are not immune to lightning strikes and can still be run over by a car, and an overabundance of optimism can lead to extremely negative consequences related to self-confidence, from poor financial decisions to disastrous political blunders. But as Feibel and Hale found, positive expectations tend to lead to positive outcomes.

More recently, psychologists Michael Scheier and Charles Carver have gone even further in their research, suggesting that positive effects cannot be due to control and expectations alone (7). Instead, they suggested that what matters is your overall outlook on life, or, as they called it, your "life orientation." Their Life Orientation Test, or LOT, measures how a person responds to a range of statements that range from "It's hardly worth waiting for everything to go the way I want" to "In troubled times, I usually count on the best" .

Positive responses are associated with overall success, while negative responses are associated with depression and feelings of helplessness. In a review of the positive health effects of an optimistic outlook on life, psychologists found that a more positive outlook, even if misguided, was associated with a better ability to cope with stressful situations. Moreover, it prevents the development of depression: a study of women observed during the last trimester of pregnancy and during the first three weeks after they gave birth showed that the initial level of optimism predicted a low likelihood of postpartum depression. In addition, students who showed a high level of optimism in a number of psychological assessments during the first days of their stay in an educational institution showed better educational results and were more successful after three months.

In a review of the positive health effects of an optimistic outlook on life, psychologists found that a more positive outlook, even if misguided, was associated with a better ability to cope with stressful situations. Moreover, it prevents the development of depression: a study of women observed during the last trimester of pregnancy and during the first three weeks after they gave birth showed that the initial level of optimism predicted a low likelihood of postpartum depression. In addition, students who showed a high level of optimism in a number of psychological assessments during the first days of their stay in an educational institution showed better educational results and were more successful after three months.

But the effects found may go beyond psychological limits. Men who were more optimistic before they had coronary artery bypass surgery were less likely to have heart attacks during surgery and recover faster afterward.

In a new review (1), Carver and Scheier further expanded on their original findings to show that increased optimism—albeit with other factors—also leads to more successful careers, protects against end-of-life loneliness, strengthens marriage and friendships, reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality in women, protects against strokes, reduces the need for rehospitalization after surgery, and improves the quality of sleep in children. In all cases, optimism serves as a screen that allows us to see life in a light that ensures our mental and physical well-being.

In all cases, optimism serves as a screen that allows us to see life in a light that ensures our mental and physical well-being.

Going deeper: Resilience: what it depends on and how to develop it

As Daniel Gilbert (8) says, everything comes back to expectations. When we expect to get through something, we move on. When we look down, we stop resisting. Depressed realists and cynics set themselves a lower bar when they start something and then give up when they find themselves hopelessly behind. As the pessimist Eeyore, familiar to everyone, said in the work of A.A. Milna, “We all can't, and some of us don't want to. That, in fact, is all.” Eeyore does not find his tail or home - yes, a lot of things. In fact, his expectations are so low that they don't even seem worth the effort. The negative outlook is self-defining: you set lower expectations, did less, achieved less, and had a negative experience that in turn matches your initial negative attitude.

Of course, unjustified optimism can also cost us dearly. This is the mindless optimism of Tigra, who finds himself stuck in a tree and eating thistles. The optimism of the Tiger, constantly getting into all sorts of trouble. When we're overconfident and think we're in control, we may find ourselves fooled by trying to solve hopeless problems.

Optimism and pessimism require a balance. If you set the bar too high, the consequences can be just as dangerous. If you aim for an Olympic medal in figure skating when you can barely complete a double Axel, you can hardly avoid disappointment.

However, it seems to be much more useful to think like a Tigger than like an Eeyore. At least that's what the study tells us.

Based on Maria Konnikova's article "Don't Worry, Be Happy", published in The New Yorker.

Cover: Pablo Picasso, In Lapin Agile (1905).

Research links

1. Alloy LB, Abramson LY. "Judgment of contingency in depressed and nondepressed students: sadder but wiser?" / J Exp Psychol Gen. 1979 Dec;108(4):441-85.

1979 Dec;108(4):441-85.

2. Carver C.S., Scheier M. F. “Dispositional optimism”/Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Volume 18, Issue 6, p293–299, June 2014; DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2014.02.003.

3. Neuvonen E., Rusanen M. “Late-life cynical distrust, risk of incident dementia, and mortality in a population-based cohort”/Neurology, May 28, 2014$ doi: http://dx.doi. org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000000528.

4. Alloy L.B., Clements C. M. “Illusion of control: invulnerability to negative affect and depressive symptoms after laboratory and natural stressors”/J Abnorm Psychol. 1992 May;101(2):234-45.

5. Mezulis A.H., Abramson L.Y., Hyde J.S., Hankin B.L. “Is there a universal positivity bias in attributions? A meta-analytic review of individual, developmental, and cultural differences in the self-serving attributional bias”/Psychol Bull. 2004 Sep;130(5):711-47.

6. Fibel B.; Hale W. D. "The Generalized Expectancy for Success Scale: A new measure"/Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Vol 46(5), Oct 1978, 924-931.

7. Scheier M.F, Carver C.S. "Optimism, coping, and health: assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies"/Health Psychol. 1985;4(3):219-47.

8. Sarit G.A.; Daniel G.T.; Timothy W. D. "Anticipating one's troubles: The costs and benefits of negative expectations"/Emotion, Vol 9(2), Apr 2009, 277-281. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0014716.

If you find an error, please select a piece of text and press Ctrl+Enter .

depressionresearchpsychology

An optimist and a pessimist - what are their advantages and disadvantages0001

Hello friends!

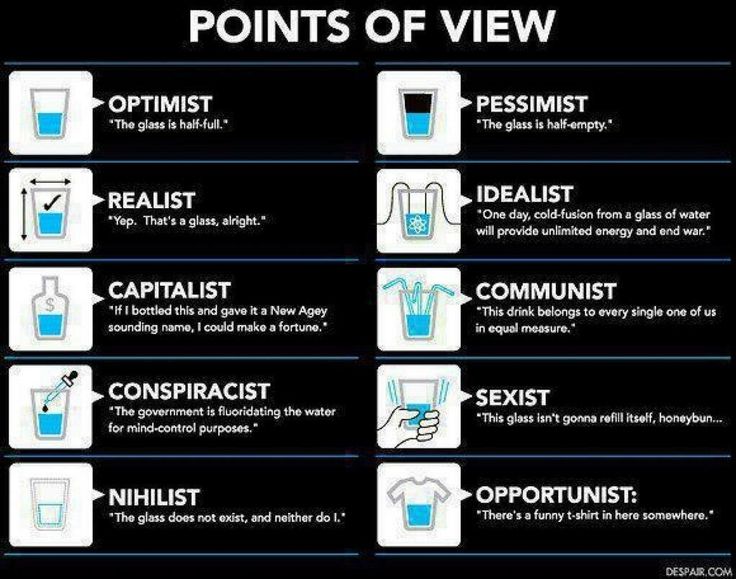

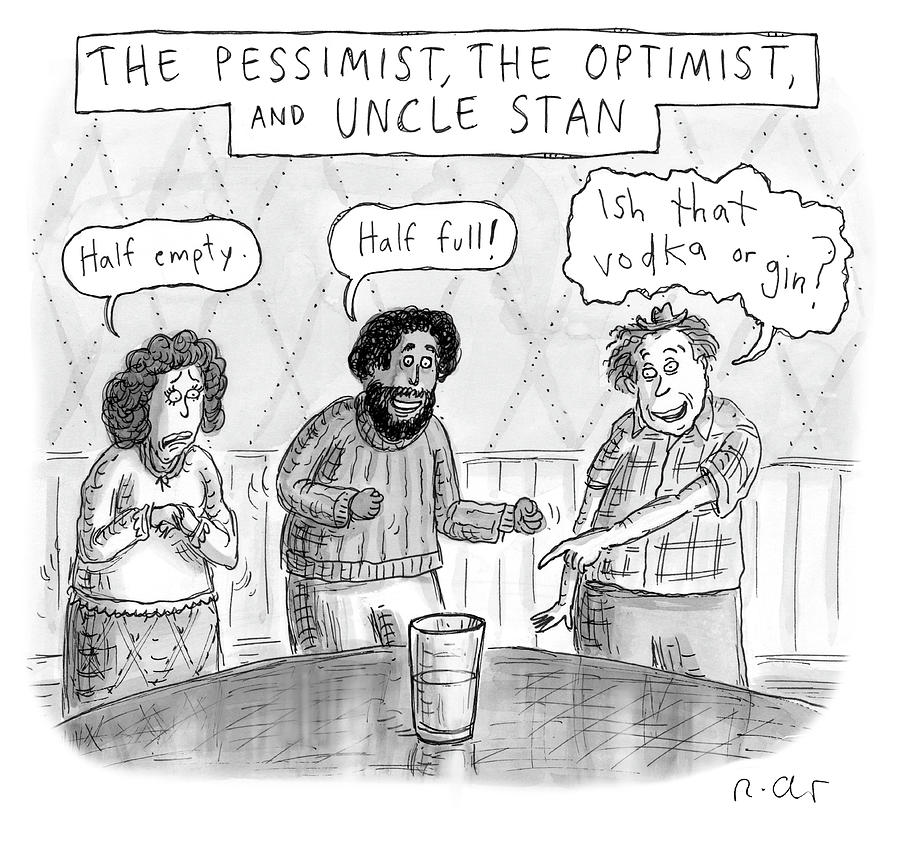

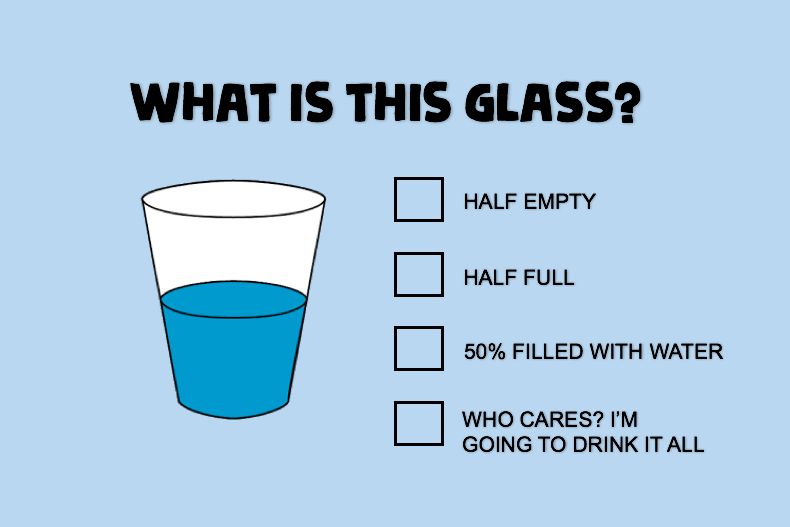

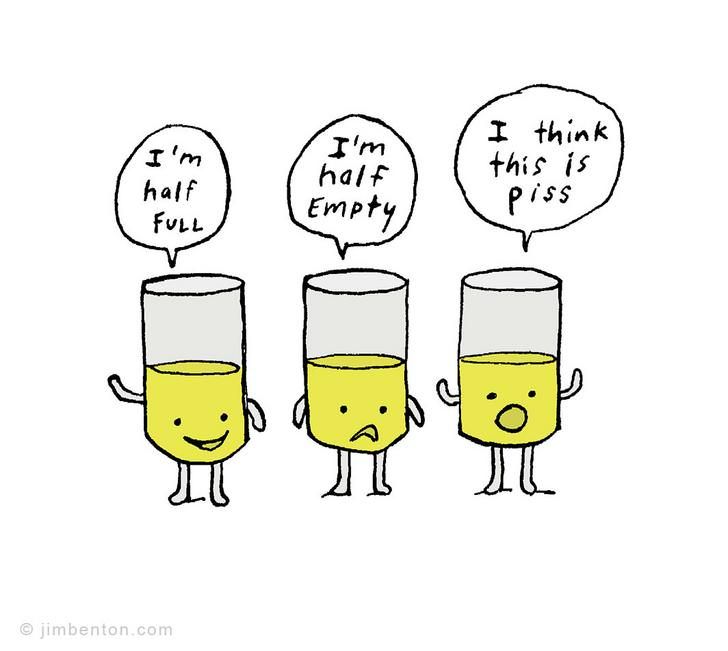

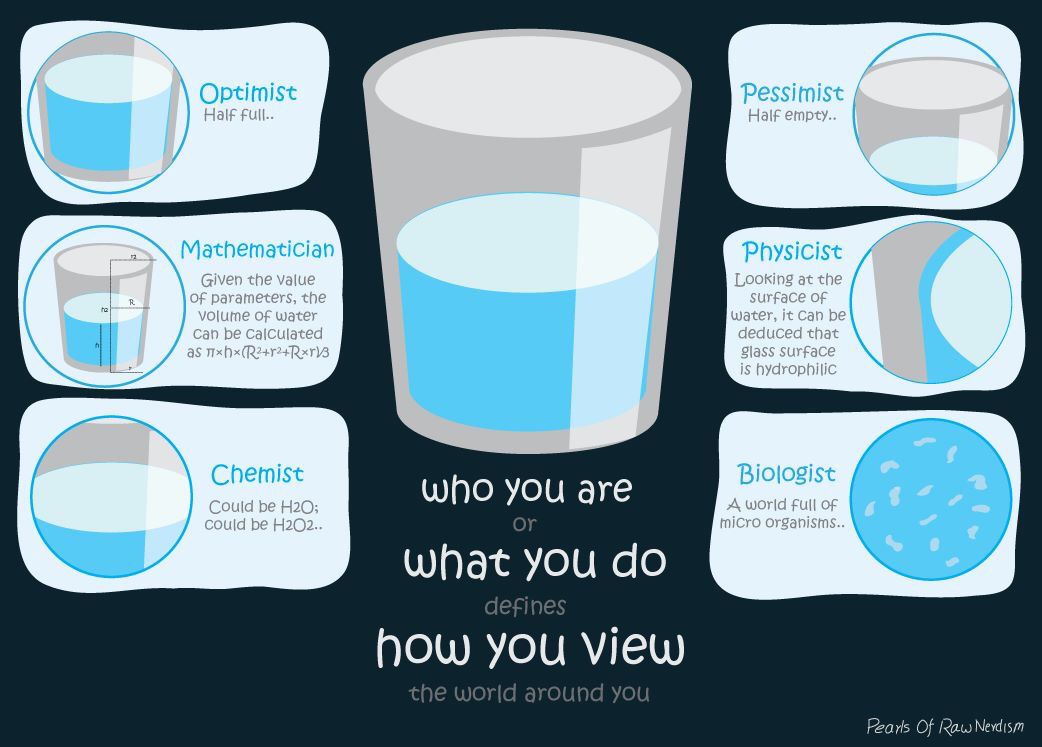

Is the glass half full or empty? Surely you are familiar with this rhetorical question, which allows you to determine the attitude of a person and shows whether he is a pessimist or an optimist. We tend to think that optimism is always better than pessimism. But is it really so?

Today we will tell you who an optimist and a pessimist are and why everything is not so simple in this story.

Definitions of concepts

Optimism in Latin optimus means “the best”. This is a positive attitude towards life, reflecting faith and hope for a positive or desired outcome of any events.

Accordingly, an optimist is someone who sees the positive aspects in everything, looks at life with an open heart and always hopes for the best.

In opposition to this concept, the word “pessimism” is used. From the Latin pessimus is translated as "the worst" and means a negative outlook on life.

A pessimist is a person who finds a reason for discontent and despondency in everything, always relies on a negative outcome and complains about life.

In simple words, optimism and pessimism are two sides of the same coin, two opposite views on the same conditions and circumstances.

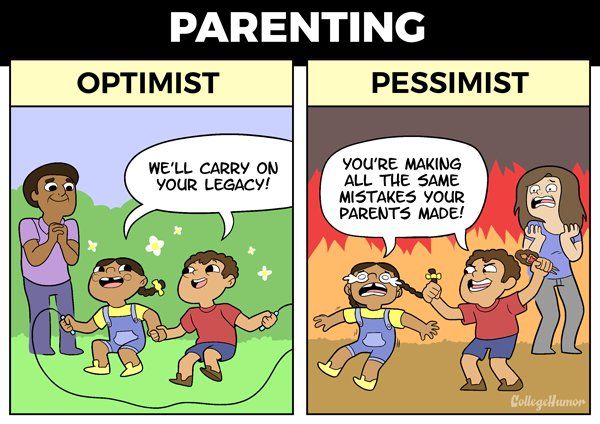

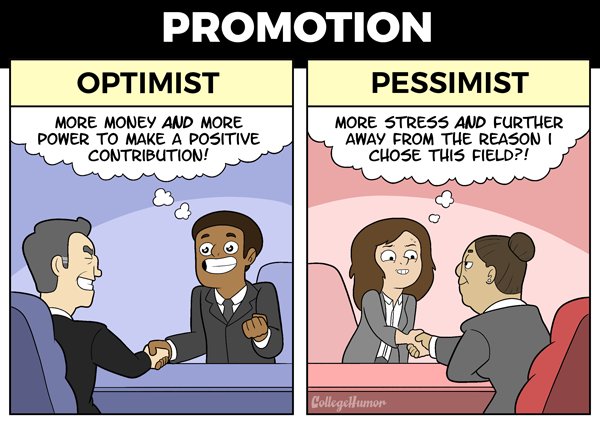

Pros and cons of optimists

Looking at a glass of water, an optimist will call it half full. He considers the world beautiful, and sees the people around him as good. Such a person will not blame the government, neighbors, housing and communal services for all his failures. Optimists are drawn to, it is pleasant to communicate with them, they cheer up and inspire.

He considers the world beautiful, and sees the people around him as good. Such a person will not blame the government, neighbors, housing and communal services for all his failures. Optimists are drawn to, it is pleasant to communicate with them, they cheer up and inspire.

What other nice bonuses do people with a positive way of thinking have:

- energy;

- high performance;

- initiative;

- good resistance to stress and depression;

- lower risk of developing psychosomatic diseases;

- sociability, the ability to find a common language with everyone;

- cheerfulness;

- the ability to take risks and not be afraid of defeat.

But is everything so rosy? Few people think about the fact that excessive optimism can be even more dangerous than chronic pessimism.

We list the negative aspects of optimism:

- Optimism often goes hand in hand with an unwillingness to enter into conflicts.

A person tries his best to smooth corners even in cases where it is simply necessary to fight back and protect his personal boundaries. For example, if neighbors flooded, an optimist can think like this: “Why quarrel, they didn’t do it on purpose, but I still wanted to make a new repair.” In this case, the positive-minded person and his family will bear the losses. But if this happened at work, the negative consequences can affect the entire business.

A person tries his best to smooth corners even in cases where it is simply necessary to fight back and protect his personal boundaries. For example, if neighbors flooded, an optimist can think like this: “Why quarrel, they didn’t do it on purpose, but I still wanted to make a new repair.” In this case, the positive-minded person and his family will bear the losses. But if this happened at work, the negative consequences can affect the entire business. - Another shortcoming is seeing the world through rose-colored glasses. A person sees what he wants, sometimes not noticing the obvious facts.

- Irrational attitude to finances. You only live once! Here is a common phrase of optimists. Often this leads to multiple loans that meet less important needs. Life beyond its means can drag you into a debt hole, and at the same time a person will underestimate the riskiness of the situation.

Advantages and disadvantages of pessimists

Since pessimism is traditionally associated with negative qualities, let's start with the minuses:

- the predominance of negative emotions;

- quarrelsomeness, conflict;

- frequent complaints and discontent, tediousness;

- shifting blame and responsibility onto others;

- lack of purposefulness;

- high susceptibility to stress;

- hypochondria.

As a consequence, such people usually have very few friends. Due to the fact that a pessimist most often stays in the negative, talks about problems and shortcomings, it is very difficult to discern an interesting interlocutor in him.

At the same time, this type of attitude also has positive aspects:

- A pessimist is always ready for undesirable scenarios, and therefore often calculates his every step, weighing all the pros and cons. He does not rush into the pool with his head and looks at life more pragmatically than an inveterate optimist.

- A person who is set to fail will not panic and be upset if his predictions come true. Less hope means less disappointment.

- He is less likely to get into dangerous and unpleasant situations, because he does not trust strangers and shows increased vigilance and caution. A pessimist will not go on a trip without a first aid kit, will not leave the house without an umbrella when clouds are gathering in the sky, will not go to play in a casino, predicting his loss in advance.

- At the slightest ailment, such a person is likely to immediately go to the doctor, which will help to recognize the disease at an early stage and prevent the development of the disease.

An interesting fact. The teachings of the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer were often called the philosophy of universal pessimism. He believed that life was given not for happiness, but for suffering. It is to him that the phrase “This world is the worst possible” belongs. Another thinker, Eduard von Hartmann, was also a supporter of his pessimistic philosophy.

Is there a golden mean

Both optimism and pessimism represent a distorted perception of reality. Both types of people see the world differently than it really is. The difference is that a pessimist sees only the bad, not noticing the good. And the optimist, on the contrary, focuses on one positive, without distinguishing between risks.

None of them sees the whole picture, creating a one-sided view in their head.

It's like always using only the left hand, considering the right hand unsuitable for personal worldview or desires.

But apart from the two extremes, there is also the so-called golden mean. This is the third type of worldview, which is endowed with the most optimal outlook on life. It's called realism.

The realist sees the situation as a whole: both good and bad, without ignoring or masking anything. He knows that the world is multifaceted and can present both pleasant surprises and obstacles. Such a person does not console himself with the phrase “Tomorrow will definitely be better,” but he also does not spoil his mood with thoughts about possible troubles that may not happen.

He objectively evaluates circumstances, people, himself and his abilities, makes decisions based on the real state of affairs and prefers his own type of reaction to events.

How to become more optimistic

As we found out, optimism does not at all guarantee success and happiness. At the same time, a positive outlook on life makes it more pleasant, joyful, attracts many interesting people, gives hope and inspires confidence. In addition, according to research, the physical and emotional health of optimists is stronger than that of those who are prone to discouragement.

At the same time, a positive outlook on life makes it more pleasant, joyful, attracts many interesting people, gives hope and inspires confidence. In addition, according to research, the physical and emotional health of optimists is stronger than that of those who are prone to discouragement.

That is why recommendations on how to develop optimism in yourself will never be superfluous.

So, how to stop being a pessimist and look at the world more positively:

- Monitor your speech and stop any attempts to complain about anyone or anything. Over time, you will begin to notice how there are fewer reasons for dissatisfaction, and life becomes easier.

- Practice positive affirmations and visualization. Do you know that our brain has neuroplasticity? It is able to build new neural connections and erase old ones. The more we work on creating a new habit, whether it is cooking porridge in the morning or positive thinking, the faster new chains will form in the brain, gradually oppressing the old, unnecessary ones.

- Try to look at successes and failures differently. Do not consider victory as an accident, praise yourself for achievements and gratefully accept praise from others. Also, do not blame yourself for failures, because they happen to everyone.

- Find your passion. The one who burns with his hobby has no time for moping and complaining. Do what you like, what brings pleasure and distracts from everyday life.

- Associate with positive people. In a circle of like-minded pessimists, you are unlikely to become more optimistic. Keep away from whiners and complainers who spoil the mood not only for themselves, but also for others.

- Learn to relax. This will help meditation, listening to classical music, massage, sauna - choose what suits you personally. Tension leads to stress, and this is not the best companion for positive thinking. You may need information on how to deal with stress.

- Practice with the breath. In yoga, there are a lot of breathing exercises that help renew energy in the body and clear thoughts of negativity.

For example, try to do the following a couple of times during the day: close the right nostril and breathe with the left for 30 seconds, after 1-2 minutes repeat the exercise, only with the other nostril.

For example, try to do the following a couple of times during the day: close the right nostril and breathe with the left for 30 seconds, after 1-2 minutes repeat the exercise, only with the other nostril. - Move more. Have you heard the phrase that movement is life? These are not empty words. Sport helps not only to stay in good shape and maintain health, but also significantly improves mood.

- Smile. It sounds too banal, but just listen to what arguments are given by experts who recommend smiling more often. We are used to thinking that positive emotions affect facial expressions, that is, something made us happy - we smiled. In fact, this process also works in reverse. If you smile for 2-3 minutes, your mood is guaranteed to improve. Check it out!

Conclusion

We have learned what optimism, pessimism and realism are, and also analyzed how these types of attitude differ from each other.

If we give the same analogy with a glass of water, then the optimist will consider it almost full and will drink it all in one gulp, and then will suffer from thirst.