Antipsychotic for bipolar depression

An Overview of Atypical Antipsychotics for Bipolar Depression

Chris Aiken, MD

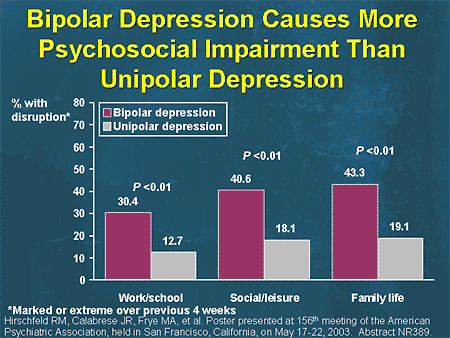

For most patients, bipolar is a disorder of depression. It’s here that they spend the majority of their days...

For most patients, bipolar is a disorder of depression. It’s here that they spend the majority of their days, so an atypical antipsychotic that has benefits in depression is usually the best choice.1

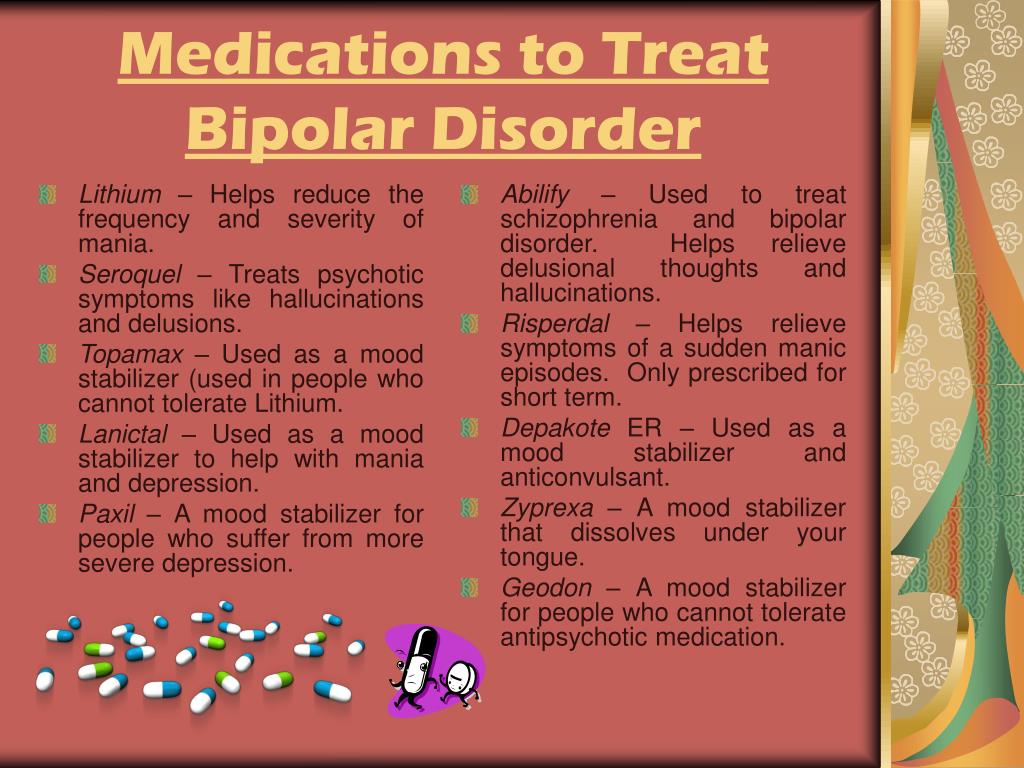

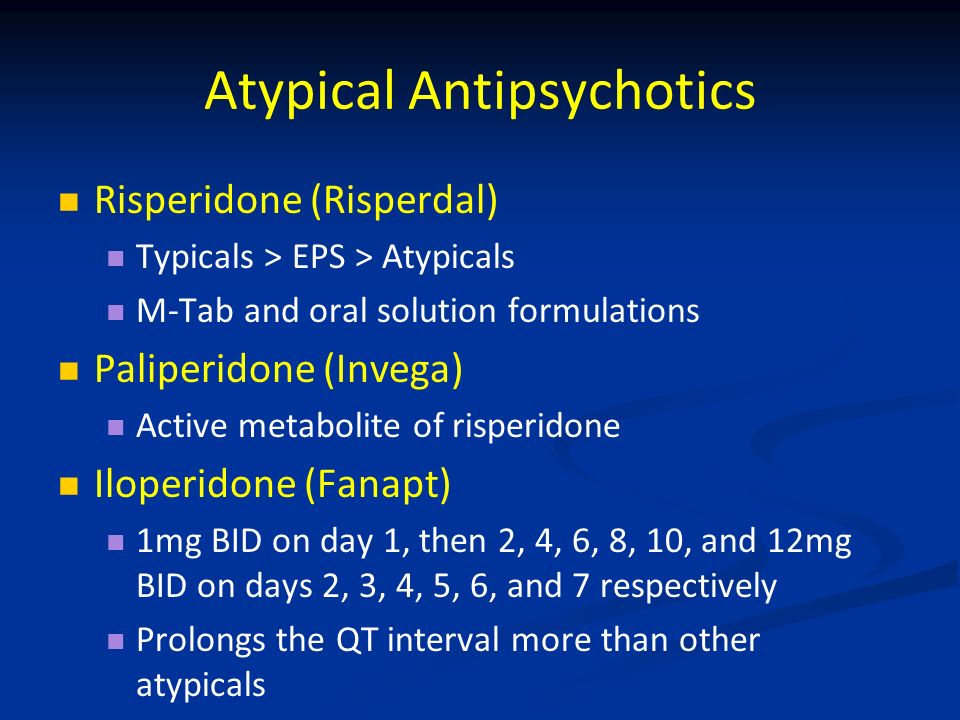

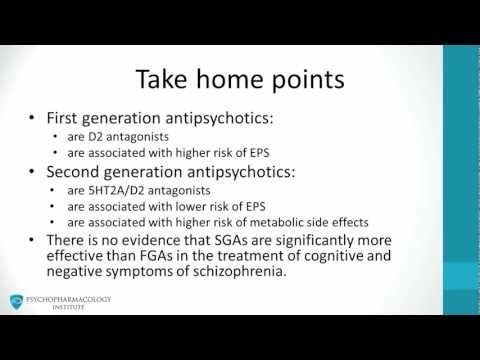

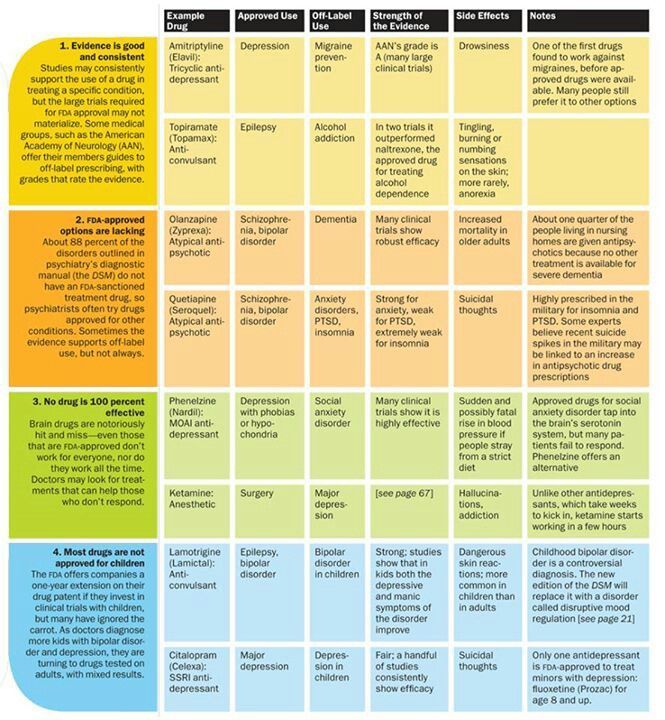

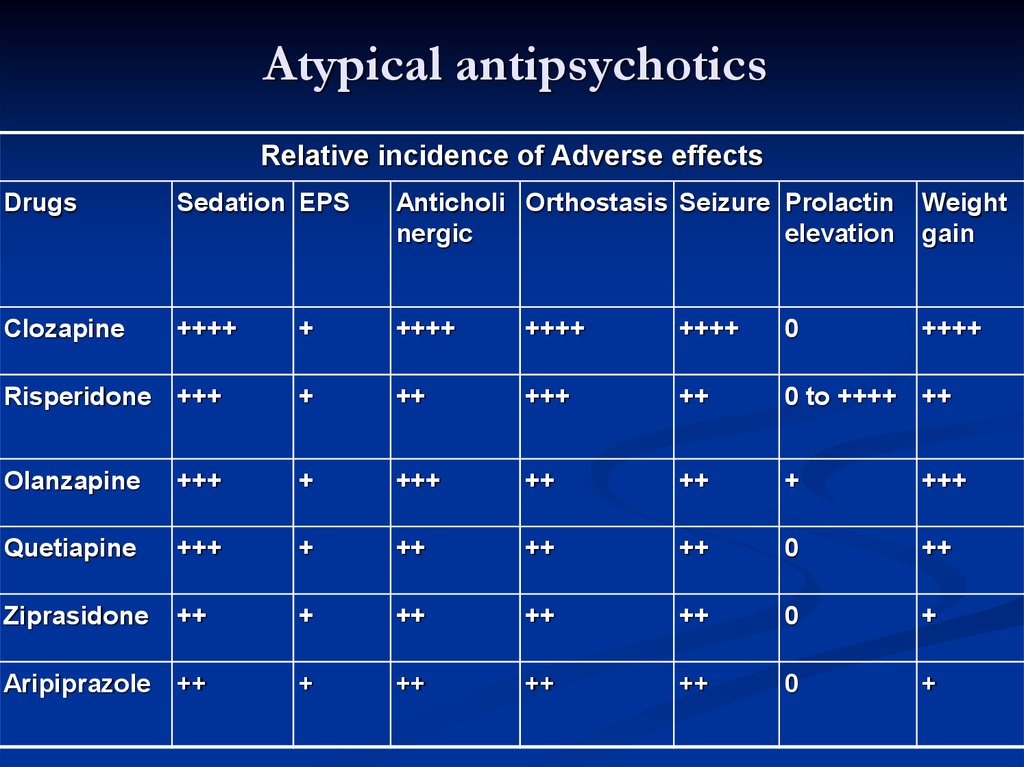

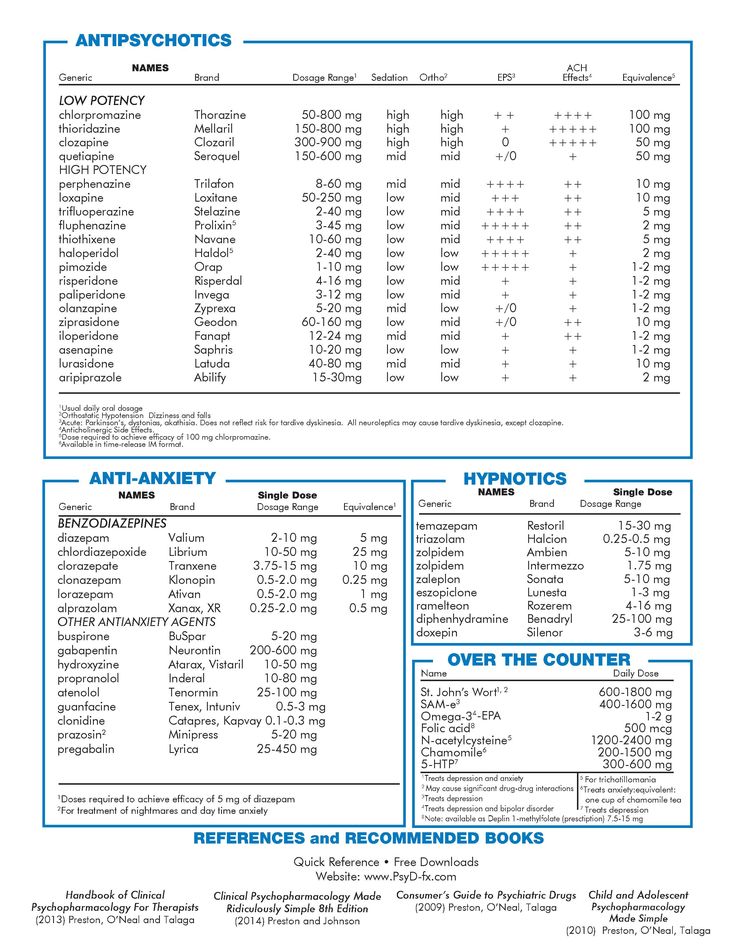

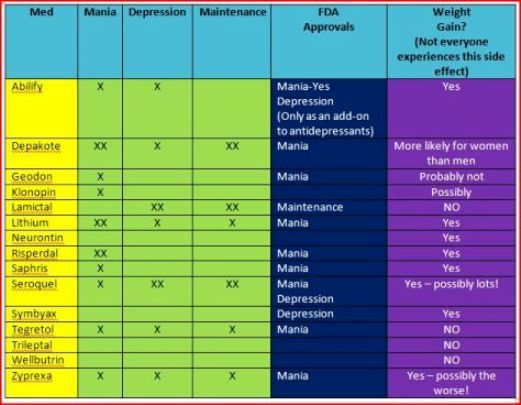

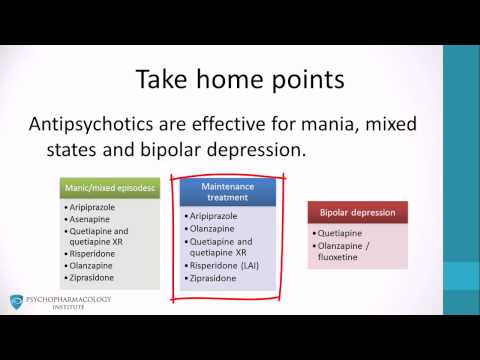

The atypical antipsychotics are complex drugs. No two have the same profile, and the line between their receptor profile and clinical effects is a hard one to follow. Only four are FDA-approved in bipolar depression: cariprazine (Vraylar

®), lurasidone (Latuda®), olanzapine-fluoxetine combination (Symbyax®), and quetiapine (Seroquel®). The Tableprovides dosage ranges for the four atypical antipsychotics that are FDA-approved for bipolar depression. Most of the other atypical antipsychotics have been tried but failed to show efficacy in bipolar depression, including a few that work in unipolar depression: aripiprazole, ziprasidone, and risperidone.2 Asenapine (Saphris®), brexpiprazole (Rexulti®), and paliperidone (Invega®) are untested.

Cariprazine (Vraylar®)

Cariprazine (no equivalent generic version equivalent in the US) is FDA-approved for both manic and depressive episodes in bipolar disorder. It has favorable rates of weight gain and fatigue, especially in the lower dose range. Adverse effects that get in the way for patients include akathisia and extrapuramidal symptoms. The number needed to treat is higher than for other atypical antipsychotics for bipolar depression (10 versus 2 to 6 for remission and response).3

To minimize akathisia, start with 1.5 mg every other day. Cariprazine’s long half-life (2-5 days) allows this kind of dosing.

Lurasidone (Latuda®)

Lurasidone (no equivalent generic version available in the US) is FDA-approved for bipolar depression in patients as young as 12 years. It has favorable rates of weight gain and fatigue and is the only atypical antipsychotic with evidence to improve cognition in bipolar disorder, based on a small controlled trial in euthymic bipolar I patients.4

No studies have been undertaken in patients with mania, although it does work in unipolar depression with mixed features. It must be taken with a meal of more than 350 kcal. Nausea and akathisia are common causes of discontinuation.

We don’t know the ideal dose of lurasidone because it was dosed flexibly in the bipolar depression trials. An analysis of that data suggests it that higher doses are more effective, with a linear dose-response relationship between 20 and 120 mg.5

Olanzapine-fluoxetine combo (OFC) (Symbyax)

Statistically speaking, OFC may be the most effective therapy for acute bipolar depression, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 2 compared with 5 to 11 for other FDA-approved atypical antipsychotics. 3

3

Olanzapine does not treat depression on its own so it requires the fluoxetine component to work. This is a potential draw-back because fluoxetine may worsen manic or mixed symptoms. The prescription can be written as a single combo pill, which helps some patients save on their copays, or as the two medications, which is cheaper for patients who pay full price for the medicine.

Weight gain and metabolic adverse effects are also significant risks with this medicine, but they can be ameliorated somewhat with metformin. This anti-diabetic agent has the best preventative effects for weight gain on atypical antipsychotics, and it works better when started earlier (500-1000 mg/d with food).6

Although ost meta-analyses rank OFC at the top of the efficacy list in bipolar depression, the story is different in unipolar depression, where its efficacy usually ranks near the bottom among atypical antipsychotic anugmentation agents.7

Quetiapine (Seroquel)

Quetiapine is FDA-approved for both manic and depressed episodes in bipolar disorder. Moreover, it may improve sleep quality and comorbid anxiety.8,9 Quetiapine has favorable rates of akathisia and extrapyramidal effects.

Moreover, it may improve sleep quality and comorbid anxiety.8,9 Quetiapine has favorable rates of akathisia and extrapyramidal effects.

However, quetiapine’s adverse effects, particularly sedation and hypotension, are a common cause of discontinuation and emergency department visits.10 Weight gain and metabolic effects are significant long-term problems. Furthermore, despite early hopes, patients on quetiapine are at risk for tardive dyskinesia.11

Both the extended release (XR) and instant release (IR) versions of quetiapine are FDA-approved for bipolar depression. For reasons that have more to do with its patent than its pharmacology, only the XR is approved in unipolar depression.

Quetiapine IR can be dosed all-at-night, and this strategy usually results in less daytime fatigue than the XR version. Hypotension, however, is lessened with the smoother peaks of quetiapine XR, particularly in doses higher that 300 mg.12

Conclusion

None of the atypical antipsychotics stands out as the best choice for bipolar depression. Both of the generic options are low on tolerability, but OFC is the most likely to work and quetiapine has additional benefits in sleep and anxiety. Cariprazine and lurasidone are better tolerated overall, unless the problem is akathisia or out-of-pocket expense.

Both of the generic options are low on tolerability, but OFC is the most likely to work and quetiapine has additional benefits in sleep and anxiety. Cariprazine and lurasidone are better tolerated overall, unless the problem is akathisia or out-of-pocket expense.

Disclosures:

Dr Aiken is the Director of the Mood Treatment Center and an Instructor in Clinical Psychiatry at the Wake Forest University School of Medicine. As the Editor in Chief of The Carlat Psychiatry Report, he hosts a weekly podcast with Kellie Newsome on psychiatric practice. He is the coauthor with Jim Phelps, MD, of Bipolar, Not So Much. He does not accept honoraria from pharmaceutical companies.

References:

1. Taylor DM, Cornelius V, Smith L, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of drug treatments for bipolar depression: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130:452-469.

2. Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Akiskal HS, et al. Long-term symptomatic status of bipolar I vs bipolar II disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;6:127-137.

Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;6:127-137.

3. Pinto JV, Saraf G, Vigo D, et al. Cariprazine in the treatment of bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bipolar Disord. Oct 16, 2019 [Epub ahead of print].

4. Yatham LN, Mackala S, Basivireddy J, et al. Lurasidone versus treatment as usual for cognitive impairment in euthymic patients with bipolar I disorder: a randomised, open-label, pilot study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:208-217.

5. Chapel S, Chiu YY, Hsu J, et al. Lurasidone dose response in bipolar depression: a population dose-response analysis. Clin Ther. 2016;38:4-15.

6. Hendrick V, Dasher R, Gitlin M, et al. Minimizing weight gain for patients taking antipsychotic medications: the potential role for early use of metformin. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2017;29:120-124.

7. Spielmans G, Berman MI, Linardatos E, et al. Adjunctive atypical antipsychotic treatment for major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of depression, quality of life, and safety outcomes. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001403.

PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001403.

8. Gedge L, Lazowski L, Murray D, et al. Effects of quetiapine on sleep architecture in patients with unipolar or bipolar depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2010;6:501-508.

9. Lydiard RB, Culpepper L, Schiöler H, et al. Quetiapine monotherapy as treatment for anxiety symptoms in patients with bipolar depression: a pooled analysis of results from 2 double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Prim Care Comp J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11:215-225.

10. Hampton LM, Daubresse M, Chang HY, et al. Emergency department visits by adults for psychiatric medication adverse events. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:1006-10014.

11. Carbon M, Kane JM, Leucht S, et al. Tardive dyskinesia risk with first- and second-generation antipsychotics in comparative randomized controlled trials: a meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2018;17:330-340.

12. Kishi T, Ikuta T, Sakuma K, et al. Comparison of quetiapine immediate- and extended-release formulations for bipolar depression: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Psychiatr Res. 2019;115:121-128.

J Psychiatr Res. 2019;115:121-128.

Related Article >>>

Atypical antipsychotics for bipolar disorder

Save citation to file

Format: Summary (text)PubMedPMIDAbstract (text)CSV

Add to Collections

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Name your collection:

Name must be less than 100 characters

Choose a collection:

Unable to load your collection due to an error

Please try again

Add to My Bibliography

- My Bibliography

Unable to load your delegates due to an error

Please try again

Your saved search

Name of saved search:

Search terms:

Test search terms

Email: (change)

Which day? The first SundayThe first MondayThe first TuesdayThe first WednesdayThe first ThursdayThe first FridayThe first SaturdayThe first dayThe first weekday

Which day? SundayMondayTuesdayWednesdayThursdayFridaySaturday

Report format: SummarySummary (text)AbstractAbstract (text)PubMed

Send at most: 1 item5 items10 items20 items50 items100 items200 items

Send even when there aren't any new results

Optional text in email:

Create a file for external citation management software

Full text links

Elsevier Science

Full text links

Review

. 2005 Jun;28(2):325-47.

2005 Jun;28(2):325-47.

doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2005.01.001.

Lakshmi N Yatham 1

Affiliations

Affiliation

- 1 Mood Disorders Clinical Research Unit, University of British Columbia, Room 2C7-2255 Wesbrook Mall, Vancouver, BC V6T 2A1, Canada. [email protected]

- PMID: 15826735

- DOI: 10.1016/j.psc.2005.01.001

Review

Lakshmi N Yatham. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2005 Jun.

. 2005 Jun;28(2):325-47.

2005 Jun;28(2):325-47.

doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2005.01.001.

Author

Lakshmi N Yatham 1

Affiliation

- 1 Mood Disorders Clinical Research Unit, University of British Columbia, Room 2C7-2255 Wesbrook Mall, Vancouver, BC V6T 2A1, Canada. [email protected]

- PMID: 15826735

- DOI: 10.1016/j.psc.2005.01.001

Abstract

Atypical antipsychotic agents have been widely investigated for their efficacy in acute mania. The data to date suggest that olanzapine,risperidone, quetiapine, aripiprazole, and ziprasidone are effective, with no significant differences in antimanic efficacy among these agents. These agents are effective as an alternative to lithium or divalproex as monotherapy or in combination with these mood stabilizers. The data concerning their utility in acute bipolar depression and maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder are limited. The studies to date suggest that olanzapine has modest acute antidepressant properties but probably has efficacy comparable to lithium and divalproex in preventing manic and depressive episodes. Quetiapine seems to have robust antidepressant properties, but these data need to be replicated in further trials before quetiapine can be recommended as a first-line agent for acute bipolar depression. Aripiprazole has shown promise in preventing manic episodes in one 6-month study, but further studies with at least 1-year duration and larger sample sizes are needed before this agent can be recommended as a monotherapy for prophylaxis of bipolar disorder. It is currently unknown if risperidone, aripiprazole, and ziprasidone have any efficacy in treating acute bipolar depression.

These agents are effective as an alternative to lithium or divalproex as monotherapy or in combination with these mood stabilizers. The data concerning their utility in acute bipolar depression and maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder are limited. The studies to date suggest that olanzapine has modest acute antidepressant properties but probably has efficacy comparable to lithium and divalproex in preventing manic and depressive episodes. Quetiapine seems to have robust antidepressant properties, but these data need to be replicated in further trials before quetiapine can be recommended as a first-line agent for acute bipolar depression. Aripiprazole has shown promise in preventing manic episodes in one 6-month study, but further studies with at least 1-year duration and larger sample sizes are needed before this agent can be recommended as a monotherapy for prophylaxis of bipolar disorder. It is currently unknown if risperidone, aripiprazole, and ziprasidone have any efficacy in treating acute bipolar depression. Similarly, long-term studies are needed to ascertain the role of risperidone, quetiapine, and ziprasidone in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Overall, the atypical antipsychotic agents as a group represent an effective and relatively safe addition to the armamentarium for the treatment of bipolar disorder.

Similarly, long-term studies are needed to ascertain the role of risperidone, quetiapine, and ziprasidone in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Overall, the atypical antipsychotic agents as a group represent an effective and relatively safe addition to the armamentarium for the treatment of bipolar disorder.

Similar articles

-

Treatment of bipolar mania with atypical antipsychotics.

Chengappa KN, Suppes T, Berk M. Chengappa KN, et al. Expert Rev Neurother. 2004 Nov;4(6 Suppl 2):S17-25. doi: 10.1586/14737175.4.6.S17. Expert Rev Neurother. 2004. PMID: 16279862 Review.

-

[Antipsychotics in bipolar disorders].

Vacheron-Trystram MN, Braitman A, Cheref S, Auffray L. Vacheron-Trystram MN, et al.

Encephale. 2004 Sep-Oct;30(5):417-24. doi: 10.1016/s0013-7006(04)95456-5. Encephale. 2004. PMID: 15627046 Review. French.

Encephale. 2004 Sep-Oct;30(5):417-24. doi: 10.1016/s0013-7006(04)95456-5. Encephale. 2004. PMID: 15627046 Review. French. -

Monotherapy versus combined treatment with second-generation antipsychotics in bipolar disorder.

Ketter TA. Ketter TA. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69 Suppl 5:9-15. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008. PMID: 19265635 Review.

-

Quetiapine in the treatment of acute bipolar mania: efficacy across a broad range of symptoms.

McIntyre RS, Konarski JZ, Jones M, Paulsson B. McIntyre RS, et al. J Affect Disord. 2007;100 Suppl 1:S5-14. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.02.007. Epub 2007 Mar 27. J Affect Disord. 2007. PMID: 17391773

-

Mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics: bimodal treatments for bipolar disorder.

Ketter TA, Nasrallah HA, Fagiolini A. Ketter TA, et al. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2006;39(1):120-46. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2006. PMID: 17065977 Review.

See all similar articles

Cited by

-

Dopamine Receptor Partial Agonists for the Treatment of Bipolar Disorder.

Azorin JM, Simon N. Azorin JM, et al. Drugs. 2019 Oct;79(15):1657-1677. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-01189-8. Drugs. 2019. PMID: 31468317 Review.

-

Dopamine transporter gene may be associated with bipolar disorder and its personality traits.

Huang CC, Lu RB, Yen CH, Yeh YW, Chou HW, Kuo SC, Chen CY, Chang CC, Chang HA, Ho PS, Liang CS, Cheng S, Shih MC, Huang SY. Huang CC, et al.

Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015 Jun;265(4):281-90. doi: 10.1007/s00406-014-0570-0. Epub 2014 Dec 30. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015. PMID: 25547317

Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015 Jun;265(4):281-90. doi: 10.1007/s00406-014-0570-0. Epub 2014 Dec 30. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015. PMID: 25547317 -

Reversible lithium neurotoxicity: review of the literatur.

Netto I, Phutane VH. Netto I, et al. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012;14(1):PCC.11r01197. doi: 10.4088/PCC.11r01197. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012. PMID: 22690368 Free PMC article.

-

One-year risk of psychiatric hospitalization and associated treatment costs in bipolar disorder treated with atypical antipsychotics: a retrospective claims database analysis.

Kim E, You M, Pikalov A, Van-Tran Q, Jing Y. Kim E, et al. BMC Psychiatry. 2011 Jan 7;11:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-6.

BMC Psychiatry. 2011. PMID: 21214937 Free PMC article.

BMC Psychiatry. 2011. PMID: 21214937 Free PMC article. -

Managing bipolar depression.

Pary R, Matuschka PR, Lewis S, Lippmann S. Pary R, et al. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2006 Feb;3(2):30-41. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2006. PMID: 21103153 Free PMC article.

See all "Cited by" articles

Publication types

MeSH terms

Substances

Full text links

Elsevier Science

Cite

Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Send To

Use of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of depressive episodes in bipolar disorder | Streltsov

Introduction

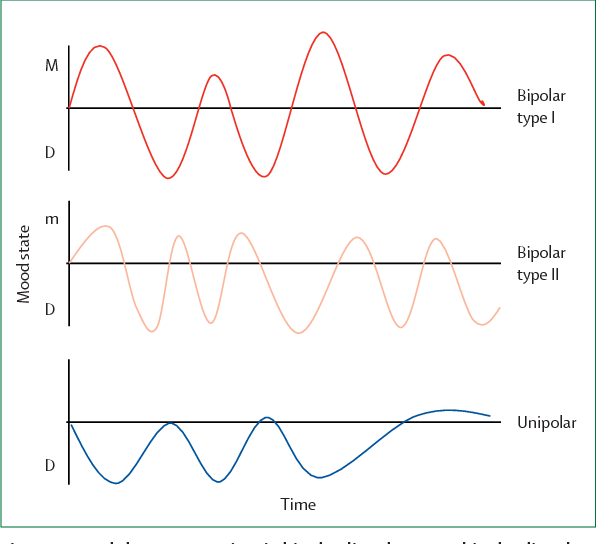

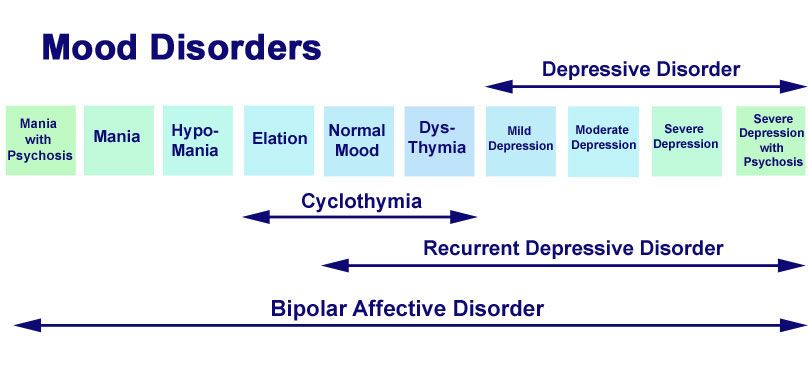

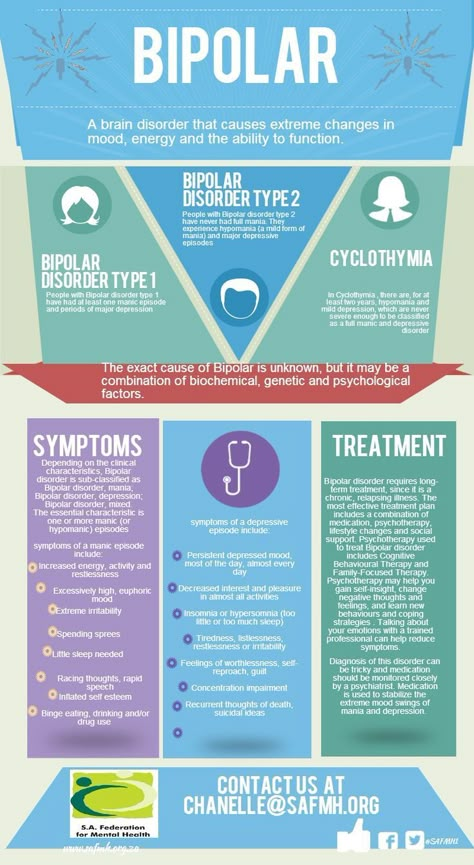

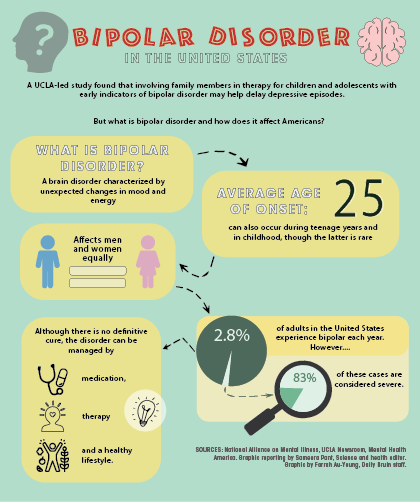

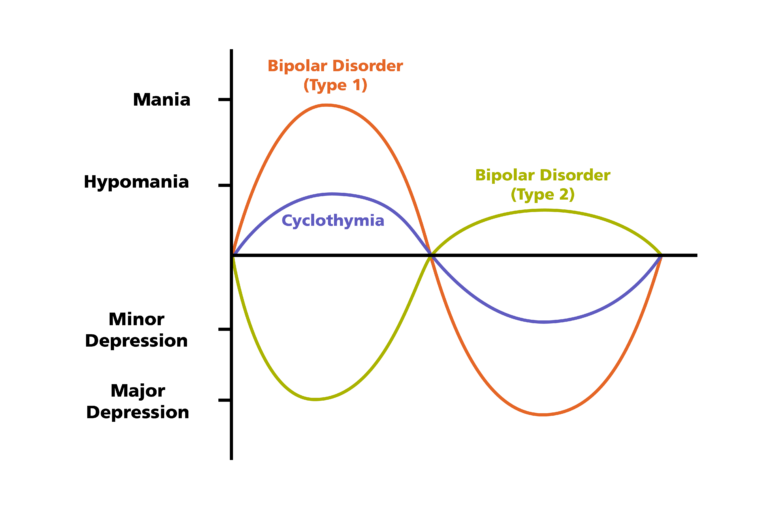

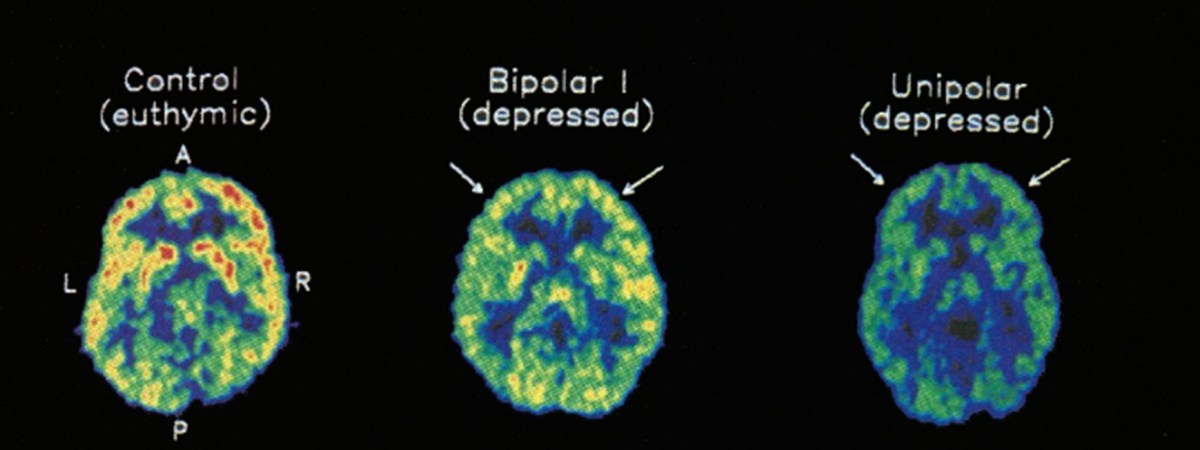

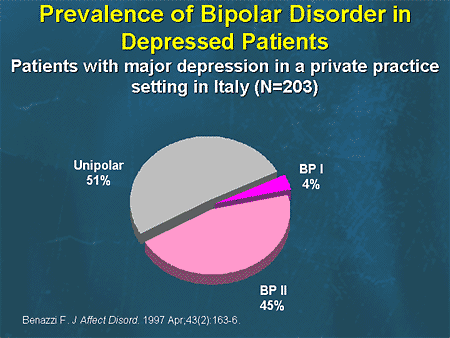

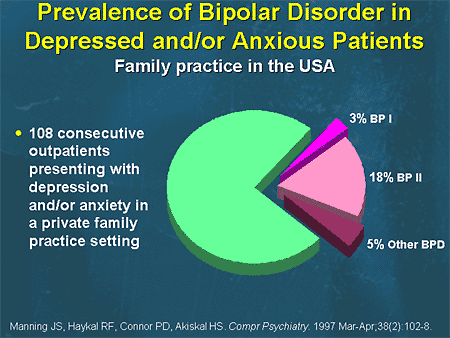

Bipolar disorder is an endogenous affective disorder that manifests itself with episodes of mania (hypomania) and depression [1]. There are currently two types of bipolar disorder: bipolar I disorder and bipolar II disorder [2]. Bipolar I disorder is manifested by mania and mixed states [3]. Type II bipolar disorder is manifested by depressive and hypomanic episodes. Manic episodes do not occur in this type of disorder.

There are currently two types of bipolar disorder: bipolar I disorder and bipolar II disorder [2]. Bipolar I disorder is manifested by mania and mixed states [3]. Type II bipolar disorder is manifested by depressive and hypomanic episodes. Manic episodes do not occur in this type of disorder.

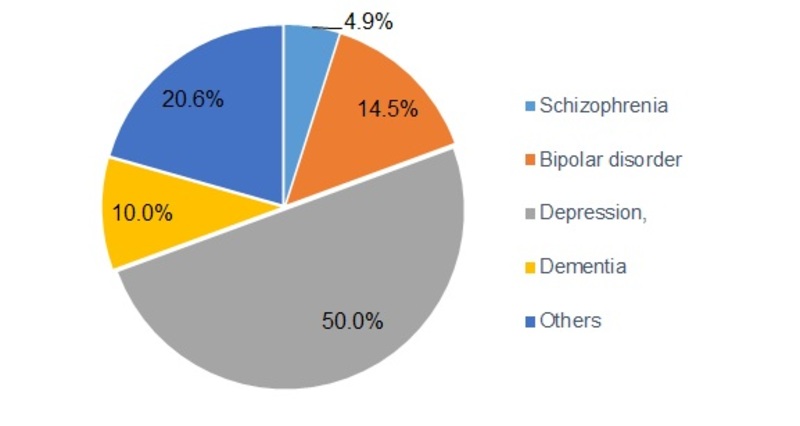

Depressive episodes are more pronounced in type II bipolar disorder than in type I [4]. Depressive episodes are the leading manifestation of the disease in patients with bipolar disorder [5]. In a systematic literature review of long-term treated patients with bipolar I disorder, researchers concluded that depression accounts for approximately 70% of affective episodes [6].

The prevalence of bipolar disorder ranges from 1% to 2.4% [7]. The percentage of suicides in patients with bipolar disorder is 4 - 19% [eight].

Problems in the treatment of depressive episodes in bipolar disorder

Adequate treatment of recurrent depressive episodes in bipolar disorder has long been a clinical problem, as antidepressants have failed to demonstrate sufficient efficacy in bipolar depression in short- and long-term studies [9].

Long-term treatment for bipolar type 2 disorder is primarily "prophylactic" in that it aims to prevent and/or reduce the frequency and severity of relapses of affective symptoms through a combination of pharmacological and complementary psychological interventions [10]. Compared with bipolar I disorder, there are limited studies demonstrating sufficient efficacy of one treatment option over others in bipolar II disorder [11].

Use of atypical antipsychotics in bipolar depression

Lurasidone

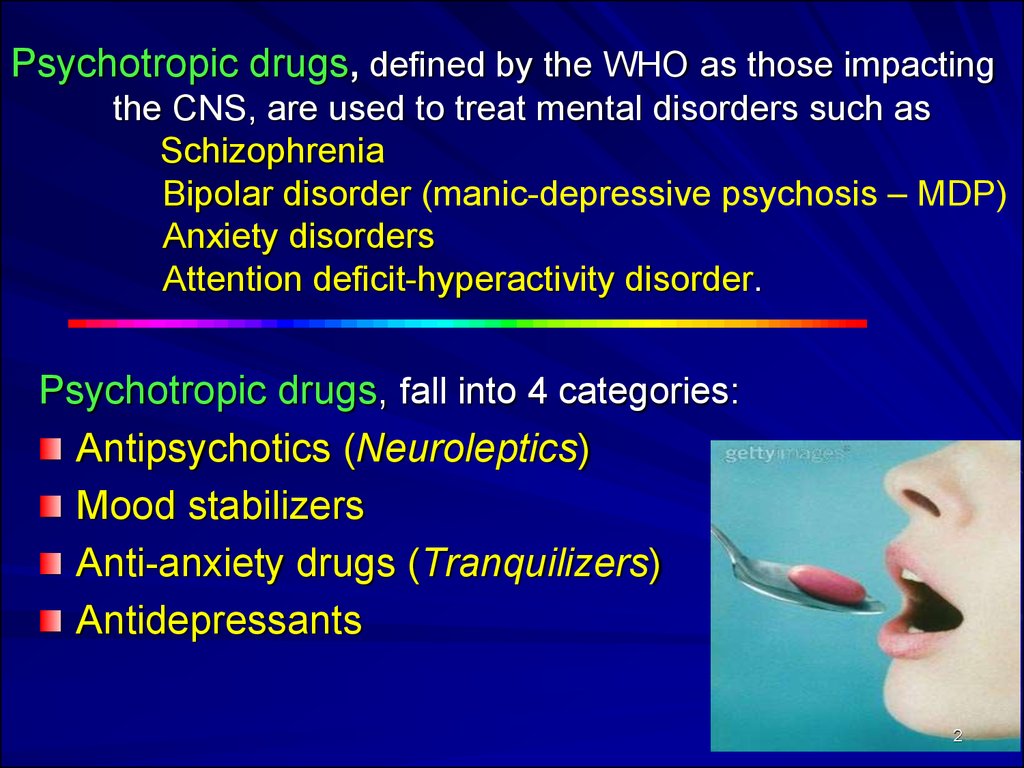

Lurasidone is an atypical antipsychotic drug with high affinity for dopamine D2 receptors, serotonin 5-HT7 and 5-HT2A receptors, moderate affinity for seroton-HT5 receptor the absence of a noticeable affinity for h2-histamine and M1-muscarinic receptors [12].

Ishigooka J., Kato T., Miyajima M. et al. conducted a 28-week study of the safety and efficacy of lurasidone. For this, patients were selected from a 6-week, double-blind, randomized study, in which patients were divided into three groups: taking the drug at dosages from 20 to 60 mg, taking 80-120 mg and taking placebo. Efficacy was assessed using the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). By the end of week 28, the overall mean MADRS score decreased as in the group previously treated with lurasidone for 6 weeks (by 8.9points) and in the group previously treated with placebo (by 11.3 points). Side effects included akathisia, headache, and drowsiness [13].

Efficacy was assessed using the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). By the end of week 28, the overall mean MADRS score decreased as in the group previously treated with lurasidone for 6 weeks (by 8.9points) and in the group previously treated with placebo (by 11.3 points). Side effects included akathisia, headache, and drowsiness [13].

Raison C.L., Siu C., Pikalov A. et al. performed a double-blind, 6-week, placebo-controlled study to investigate the association between pre-treatment levels of highly sensitive C-reactive protein (CRP) and changes in depressive symptoms and cognitive functioning in 10 patients – 17 years old with bipolar disorder. Patients were divided into groups taking flexible doses of lurasidone (20-80 mg) and groups taking placebo. The study found that patients with high baseline CRP levels responded better to lurasidone treatment than those with low baseline CRP levels, but only in patients with normal or low body mass index (BMI) levels. Lurasidone was more effective than placebo regardless of baseline CRP [14].

Cariprazine

Cariprazine is a partial agonist of dopamine receptors D 2 and D 3 , and serotonin receptor 5-HT 1A [15]. The unique affinity for the D 3 receptor may mediate the anti-anhedonic, procognitive, and antidepressant effects of cariprazine [16][17].

Durgam S., Earley W., Lipschitz A. et al. conducted an 8-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to investigate the efficacy and safety of cariprazine in patients with major depressive episodes in bipolar disorder. Patients were randomly assigned to either placebo or cariprazine at doses of 0.75, 1.5, and 3.0 mg/day. Efficacy was assessed using the MADRS and the severity subscale of the Global Clinical Impression Scale (GCI-S). Cariprazine at 1.5 mg/day showed a significant reduction in MADRS scores from baseline by week 6 compared with placebo (least squares mean difference was -4.0). When taking cariprazine at a dosage of 3 mg/day, the difference in the mean least squares was -2. 5. The 0.75 mg daily dose was similar to the placebo dose.

5. The 0.75 mg daily dose was similar to the placebo dose.

The most commonly reported adverse events in patients treated with cariprazine were akathisia and insomnia. Weight gain was slightly higher in patients treated with cariprazine than with placebo [18].

Another double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the safety and efficacy of cariprazine by Earley W., Burgess M.V., Rekeda L. et al. reported similar results. Patients aged 18 to 65 years who met the DSM-5 criteria for bipolar I disorder with a current depressive episode were selected for the study. Patients were divided into three groups: taking 3 mg cariprazine per day, taking 1.5 mg cariprazine per day and taking placebo. Efficacy was assessed using MADRS and GCI-S. After 6 weeks, data were obtained that both doses of cariprazine were significantly more effective than placebo. Both doses of cariprazine were associated with lower CGI-S scores compared with placebo, but the differences did not reach statistical significance. Side effects in the groups taking cariprazine were recorded twice as often as in the placebo group. The most common side effects were nausea, akathisia and dizziness [19].

Side effects in the groups taking cariprazine were recorded twice as often as in the placebo group. The most common side effects were nausea, akathisia and dizziness [19].

Olanzapin

Olanzapin-a drug that has an affinity to serotonin 5-nt 2a , 5-nt 2C , 5-nt 3 , 5-nt 6 , D 1 , D 3333 2 , D 3 , D 4 and D 5 , muscarinic, adrenergic α 1 and histamine H 1 receptors [20].

Katagiri H., Tohen M., McDonnell D.P. et al. conducted a 6-week, double-blind, randomized trial of the efficacy and safety of olanzapine in bipolar depression. Compared with placebo, patients in the olanzapine group showed a decrease in MADRS scores. But in this group, side effects were more common, such as weight gain, increased levels of cholesterol, triglycerides, low-density lipoproteins, and a decrease in high-density lipoproteins [21].

Pan P. Y., Lee M.S., Lo M.C. found that olanzapine

Y., Lee M.S., Lo M.C. found that olanzapine

was more effective than lamotrigine in preventing

depressive episodes in patients with bipolar disorder [22].

Quetiapine

Quetiapine is an atypical antipsychotic that blocks dopamine D2 and serotonin 5-HT2 receptors [23].

Kishi T., Ikuta T., Matsuda Y. et al. studied the efficacy and safety of extended-release quetiapine 300 mg/day and olanzapine 5-20 mg/day in patients with bipolar depression using a Bayesian analysis. As a result, it was found that there is no significant difference in effectiveness between the drugs. In patients treated with quetiapine, drowsiness was a common side effect, and in the olanzapine group, frequent side effects were: weight gain, increased blood prolactin levels, and decreased high-density lipoprotein levels [24].

Simon J., Geddes J.R., Gardiner A. conducted a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled study comparing quetiapine alone versus quetiapine plus lamotrigine. It was found that the combination of quetiapine with lamotrigine was more effective than quetiapine alone [25].

It was found that the combination of quetiapine with lamotrigine was more effective than quetiapine alone [25].

Risperidone

Lindström L., Lindström E., Nilsson M. et al. conducted a meta-analysis of 15 RCTs to investigate the efficacy of atypical antipsychotics from 6 months to 4 years in bipolar disorder in 6142 patients. As monotherapy, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone were found to be superior to placebo in reducing the overall risk of relapse [26].

A retrospective study of the effectiveness of taking risperidone to reduce the risk of affective episodes in patients with bipolar disorder showed that additional administration of the drug reduced the risk of developing manic episodes, but did not reduce the risk of developing depressive episodes [27].

In the course of comparing the safety of quetiapine and risperidone in patients with bipolar disorder, it was found that side effects such as weight gain, increased prolactin levels were detected when taking risperidone [28].

Aripiprazole and ziprasidone

Bahji A., Ermacora D., Stephenson C. et al. conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs on the efficacy and safety of pharmacological therapy for bipolar depression. During which 50 studies with 11448 patients were analyzed. aripiprazole and ziprasidone were ineffective compared with placebo in the treatment of bipolar depression. Aripiprazole had more side effects than placebo.

Olanzapine, quetiapine and cariprazine were more effective than placebo in the treatment of bipolar depression [29].

In another systematic review and meta-analysis conducted to investigate the efficacy and safety of aripiprazole in bipolar disorder, it was found that the drug was effective in the treatment of mania, psychosis, but did not show efficacy in the treatment of bipolar depression [30].

Conclusion

Lurasidone, cariprazine, olanzapine, and quetiapine were significantly more effective than placebo.

Risperidone, aripiprazole and ziprasidone have been shown to be ineffective in the treatment of bipolar depression.

Olanzapine causes more serious side effects (weight gain, increased cholesterol, triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein and decreased high-density lipoprotein) than lurasidone, cariprazine, and quetiapine.

Combination of quetiapine with lamotrigine is more effective than antipsychotic alone.

In normal weight children and adolescents with higher pre-treatment CRP levels, lurasidone was associated with a better response to antidepressant therapy than placebo. CRP and BMI may be useful diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in the treatment of children and adolescents with bipolar depression with lurasidone.

1. Tondo L, Vázquez GH, Baldessarini RJ. Depression and Mania in Bipolar Disorder. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(3):353-358. DOI: 10.2174/1570159X14666160606210811

2. Geddes JR, Miklowitz DJ. treatment of bipolar disorder. Lancet. 2013;381(9878):1672-82. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60857-0

Lancet. 2013;381(9878):1672-82. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60857-0

3. Zargar F, Haghshenas N, Rajabi F, Tarrahi MJ. Eff ectiveness of Dialectical Behavioral Thrapy on Executive Function, Emotional Control and Severity of Symptoms in Patients with Bipolar I Disorder. Adv Biomed Res. 2019;8:59. DOI: 10.4103/abr.abr_42_19

4. Novick DM, Swartz HA. Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Bipolar Disorder. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2019;17(3):238-248. DOI: 10.1176/appi.focus.201

5. Baldessarini RJ, Vieta E, Calabrese JR, Tohen M, Bowden CL. Bipolar depression: overview and commentary. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2010;18(3):143-57. DOI: 10.3109/10673221003747955

6. Forte A, Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Vázquez GH, Pompili M, Girardi P. Long-term morbidity in bipolar-I, bipolar-II, and unipolar major depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2015;178:71-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.02.011

7. Rowland TA, Marwaha S. Epidemiology and risk factors for bipolar disorder. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2018;8(9):251-269. DOI: 10.1177/2045125318769235

Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2018;8(9):251-269. DOI: 10.1177/2045125318769235

8. Dome P, Rihmer Z, Gonda X. Suicide Risk in Bipolar Disorder: A Brief Review. Medicine (Kaunas). 2019;55(8):403. DOI: 10.3390/medicina55080403

9. Liu B, Zhang Y, Fang H, Liu J, Liu T, Li L. Efficacy and safety of long-term antidepressant treatment for bipolar disorders – A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Affect Disord. 2017;223:41-48. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.023

10. Grande I, Berk M, Birmaher B, Vieta E. Bipolar disorder. Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1561-1572. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00241-X

11. Yatham LN. Diagnosis and management of patients with bipolar II disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66 Suppl 1:13-7.PMID: 15693747.

12. Ishibashi T, Horisawa T, Tokuda K, Ishiyama T, Ogasa M, et al. Pharmacological profile of lurasidone, a novel antipsychotic agent with potent 5-hydroxytryptamine 7 (5-HT7) and 5-HT1A receptor activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;334(1):171-81. DOI: 10.1124/jpet.110.167346

DOI: 10.1124/jpet.110.167346

13. Ishigooka J, Kato T, Miyajima M, Watabe K, Masuda T, et al. Lurasidone in the Long-Term Treatment of Bipolar I Depression: A 28-week Open Label Extension Study. J Affect Disord. 2021;281:160-167. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.005

14. Raison CL, Siu C, Pikalov A, Tocco M., Loebel A. C-reactive protein and response to lurasidone treatment in children and adolescents with bipolar I depression: Results from a placebo-controlled trial. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;84:269-274. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.12.010

15. Duric V, Banasr M, Franklin T, Lepack A, Adham N, et al. Cariprazine Exhibits Anxiolytic and Dopamine D3 Receptor- Dependent Antidepressant Effects in the Chronic Stress Model. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;20(10):788-796. DOI: 10.1093/ijnp/pyx038

16. Neill JC, Grayson B, Kiss B, Gyertyán I, Ferguson P, Adham N. Effects of cariprazine, a novel antipsychotic, on cognitive defi cit and negative symptoms in a rodent model of schizophrenia symptomatology. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26(1):3-14. DOI: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.11.016

Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26(1):3-14. DOI: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.11.016

17. Watson DJG, King MV, Gyertyán I, Kiss B, Adham N, Fone KCF. Th e dopamine D₃-preferring D₂/D₃ dopamine receptor partial agonist, cariprazine, reverses behavioral changes in a rat neurodevelopmental model for schizophrenia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26(2):208-224. DOI: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.12.020

18. Durgam S, Earley W, Lipschitz A, Guo H, Laszlovszky I, et al. An 8-Week Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Evaluation of the Safety and Efficacy of Cariprazine in Patients With Bipolar I Depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(3):271-81. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15020164

19. Earley W, Burgess MV, Rekeda L, Dickinson R, Szatmári B, et al. Cariprazine Treatment of Bipolar Depression: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(6):439-448. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18070824

20. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, McGlashan TH, Miller AL, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(2 Suppl):1-56. PMID: 15000267.

Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(2 Suppl):1-56. PMID: 15000267.

21. Katagiri H, Tohen M, McDonnell DP, Fujikoshi S, Case M, et al. Efficacy and safety of olanzapine for treatment of patients with bipolar depression: Japanese subpopulation analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. B.M.C. Psychiatry. 2013;13:138. DOI: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-138

22. Pan PY, Lee MS, Lo MC, Yang EL, Yeh CB. Olanzapine is superior to lamotrigine in the prevention of bipolar depression: a naturalistic observational study. B.M.C. Psychiatry. 2014;14:145. DOI: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-145

23. Sanford M, Keating GM. Quetiapine: A review of its use in the management of bipolar depression. CNS Drugs. 2012;26(5):435-60. doi: 10.2165/11203840-000000000-00000

24. Kishi T, Ikuta T, Matsuda Y, Iwata N. Quetiapine extendedrelease vs olanzapine for Japanese patients with bipolar depression: A Bayesian analysis. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2019;39(3):256-259. DOI: 10.1002/npr2.12070

Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2019;39(3):256-259. DOI: 10.1002/npr2.12070

25. Simon J, Geddes JR, Gardiner A, Rendell J, Goodwin GM, Mayer S. Comparative economic evaluation of quetiapine plus lamotrigine combination vs quetiapine monotherapy (and folic acid vs placebo) in patients with bipolar depression (CEQUEL). Bipolar Discord. 2018;20(8):733-745. DOI: 10.1111/bdi.12713

26. Lindström L, Lindström E, Nilsson M, Höistad M. Maintenance therapy with second generation antipsychotics for bipolar disorder – A systematic review and metaanalysis. J Affect Disord. 2017;213:138-150. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.02.012

27. Valdes M, Bertolin S, Qian H, Wong H, Lam RW, Yatham LN. Risperidone adjunctive therapy duration in the maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder: A post hoc analysis. J Affect Disord. 2019;246:861-866. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.01.003

28. Masi G, Milone A, Stawinoga A, Veltri S, Pisano S. Efficacy and Safety of Risperidone and Quetiapine in Adolescents With Bipolar II Disorder Comorbid With Conduct Disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35(5):587-90. DOI: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000371

J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35(5):587-90. DOI: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000371

29. Bahji A, Ermacora D, Stephenson C, Hawken ER, Vazquez G. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of pharmacological treatments for the treatment of acute bipolar depression: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;269:154-184. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.030

30. Li DJ, Tseng PT, Stubbs B, Chu CS, Chang HY, et al. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of aripiprazole in bipolar disorder: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017;79(PtB):289-301. DOI: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.06.023

Is the prescription of antidepressants for bipolar depression justified in terms of evidence-based medicine? | Potanin

1. Ivanov SV. Valdoxan in the treatment of bipolar depression: results of the Russian multicenter naturalistic study "Chronos" VM Bekhterev Review of Psychiatry and Medical Psychology. 2011;(2):26–29. https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=17701061

2011;(2):26–29. https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=17701061

2. Sorokin SA. Clinical and dynamic features of endogenous affective diseases occurring with the formation of apathetic depressions. Psychiatry. 2018;1(77):26–31. DOI:10.30629/2618-6667-2018-77-26-31

3. Panteleeva GP, Oleichik IV, Abramova LI, Yumatova PE. Treatment of endogenous depressions with venlafaxine: clinical effect, tolerability and personalized indications for prescription. Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry named after S.S. Korsakov. 2015;115(1–2):43–51. DOI:10.17116/jnevro20151152243-51

4. McIntyre RS, Cha DS, Kim RD, Mansur RB. A review of FDA-approved treatment options in bipolar depression. CNS Spectr. 2013;18(1):4–20; quiz 21. DOI:10.1017/S1092852913000746

5. State Register of Medicines. http://grls.rosminzdrav.ru/Default.aspx.

6. Morsel AM, Morrens M, Sabbe B. An overview of pharmacotherapy for bipolar I disorder. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2018;19(3):203–222. DOI:10.1080/14656566.2018.1426746

DOI:10.1080/14656566.2018.1426746

7. Post RM, Altshuler LL, Leverich GS, Frye MA, Nolen WA, Kupka RW, Suppes T, McElroy S, Keck PE, Denicoff KD., Grunze H, Walden J, Kitchen CMR , Mintz J Mood switch in bipolar depression: comparison of adjunctive venlafaxine, bupropion and sertraline. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2006;189:124–131. DOI:10.1192/bjp.bp.105.013045

8. McElroy SL, Weisler RH, Chang W, Olausson B, Paulsson B, Brecher M, Agambaram V, Merideth C, Nordenhem A, Young AH. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of quetiapine and paroxetine as monotherapy in adults with bipolar depression (EMBOLDEN II). J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2010;71(2):163–174. DOI:10.4088/JCP.08m04942gre

9. Agosti V, Stewart JW. Efficacy and safety of antidepressant monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar-II depression. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2007;22(5):309-311. DOI:10.1097/YIC.0b013e3280c28410

10. Nemeroff CB, Evans DL, Gyulai L, Sachs GS, Bowden CL, Gergel IP, Oakes R, Pitts CD Double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of imipramine and paroxetine in the treatment of bipolar depression. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2001;158(6):906–912. 11. Tohen M, Vieta E, Calabrese J, Ketter TA, Sachs G, Bowden C, Mitchell PB, Centorrino F, Risser R, Baker RW, Evans AR, Beymer K , Dube S, Tollefson GD, Breier A. Efficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine-fluoxetine combination in the treatment of bipolar I depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2003;60(11):1079–1088. 12. Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, Maangell LB, Wisniewski SR, Gyulai L, Friedman ES, Bowden CL, Fossey MD, Ostacher MJ, Ketter TA, Patel J, Hauser P, Rapport D, Martinez JM, Allen MH, Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Dennehy EB, Thase ME. Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356(17):1711–1722. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa064135

Am. J. Psychiatry. 2001;158(6):906–912. 11. Tohen M, Vieta E, Calabrese J, Ketter TA, Sachs G, Bowden C, Mitchell PB, Centorrino F, Risser R, Baker RW, Evans AR, Beymer K , Dube S, Tollefson GD, Breier A. Efficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine-fluoxetine combination in the treatment of bipolar I depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2003;60(11):1079–1088. 12. Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, Maangell LB, Wisniewski SR, Gyulai L, Friedman ES, Bowden CL, Fossey MD, Ostacher MJ, Ketter TA, Patel J, Hauser P, Rapport D, Martinez JM, Allen MH, Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Dennehy EB, Thase ME. Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356(17):1711–1722. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa064135

13. Yatham LN, Vieta E, Goodwin GM, Bourin M, de Bodinat C, Laredo J, Calabrese J, Agomelatine Study Group. Agomelatine or placebo as adjunctive therapy to a mood stabiliser in bipolar I depression: randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2016;208(1):78–86. DOI:10.1192/bjp.bp.114.147587

2016;208(1):78–86. DOI:10.1192/bjp.bp.114.147587

14. Ghaemi SN, Vohringer PA, Pakar A. Citalopram for acute and preventive efficacy in bipolar depressiom (CAPE–BD): double-blind randomized, placebo-controlled trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00562861). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00562861?term=citalopram&cond=Bipolar+Depression&draw=2&rank=2 Published 2016

15. Detke HC, Delbello MP, Landry J, Usher RW. Olanzapine/fluoxetine combination in children and adolescents with bipolar i depression: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015;54(3):217–224. DOI:10.1016/Jjaac.2014.12.012

16. Himmelhoch JM, Thase ME, Mallinger AG, Houck P. Tranylcypromine versus imipramine in anergic bipolar depression. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1991;148(7):910–916. 17. Pilhatsch M, Wolf R, Winter C, Lewitzka U, Bauer M. Comparison of paroxetine and amitriptyline as adjunct to lithium maintenance therapy in bipolar depression: A reanalysis of a randomized, double blind study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;126(3):453–457. DOI:10.1016/Jjad.2010.04.025

Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;126(3):453–457. DOI:10.1016/Jjad.2010.04.025

18. Frye MA, Helleman G, McElroy SL, Altshuler LL, Black DO., Keck Jr PE, Nolen WA, Kupka R, Leverich GS, Grunze H, Mintz J, Post RM, Suppes T. Correlates of treatment-emergent mania associated with antidepressant treatment in bipolar depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166(2):164–172. 19. Bocchetta A, Bernardi F, Burrai C, Pedditzi M, Del Zompo M A double-blind study of L-sulpiride versus amitriptyline in lithium-maintained bipolar depressives. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1993;88(6):434–439. DOI:10.1111/J1600-0447.1993.tb03487.x

20. Shelton RC, Stahl SM. Risperidone and paroxetine given singly and in combination for bipolar depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2004;65(12):1715–1719. DOI:10.4088/jcp.v65n1218

21. Silverstone T. Moclobemide vs. imipramine in bipolar depression: a multicentre double-blind clinical trial. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2001;104(2):104–109. DOI:10.1034/J1600-0447. 2001.00240.x

2001.00240.x

22. Mendlewicz J, Youdim MB. Antidepressant potentiation of 5-hydroxytryptophan by L-deprenil in affective illness. J. Affect. Discord. 1980;2(2):137–146. DOI:10.1016/0165-0327(80)

-023. Cohn JB, Collins G, Ashbrook E, Wernicke JF. A comparison of fluoxetine imipramine and placebo in patients with bipolar depressive disorder. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1989;4(4):313–322. DOI:10.1097/00004850-198910000-00006

24. Amsterdam JD, Shults J. Comparison of short-term venlafaxine versus lithium monotherapy for bipolar II major depressive episode: a randomized open-label study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(2):171–181. DOI:10.1097/JCP.0b013e318166c4e6

25. Amsterdam JD, Shults J. Efficacy and mood conversion rate of short-term fluoxetine monotherapy of bipolar II major depressive episode. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(3):306–311. DOI:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181da5300

26. van der Loos MLM, Mulder P, Hartong EGTM, Blom MBJ, Vergouwen AC, van Noorden MS, Timmermans MA, Vieta E. , Nolen WA, LamLit Study Group Efficacy and safety of two treatment algorithms in bipolar depression consisting of a combination of lithium, lamotrigine or placebo and paroxetine. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2010;122(3):246–254. DOI:10.1111/J1600-0447.2009.01537.x

, Nolen WA, LamLit Study Group Efficacy and safety of two treatment algorithms in bipolar depression consisting of a combination of lithium, lamotrigine or placebo and paroxetine. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2010;122(3):246–254. DOI:10.1111/J1600-0447.2009.01537.x

27. Amsterdam JD, Shults J. Efficacy and safety of long-term fluoxetine versus lithium monotherapy of bipolar II disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-substitution study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(7):792–800. DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.0

84 28. Kauer-Sant'Anna M, Frey BN, Fijtman A, Loredo-Souza AC, Dargél AA, Pfaffenseller B, Wollenhaupt-Aguiar B, Gazalle FK, Colpo GD, Passos IC , Bücker J, Walz JC, Jansen K, Mendes Ceresér KM, Bürke Bridi KP, dos Santos Sória L, Kunz M, Pinho M, Kapczinski NS, Goi PD, Magalhães PVS, Reckziegel R, Burque RK, de Azevedo Cardoso T, Kapczinski F. Adjunctive tianeptine treatment for bipolar disorder: A 24-week randomized, placebo-controlled, maintenance trial. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2019;33(4):502–510. 29. Altshuler LL, Post RM, Hellemann G, Leverich GS, Nolen WA, Frye MA, Keck Jr PE, Kupka RW, Grunze H, McElroy SL, Sugar CA, Suppes T. Impact of antidepressant continuation after acute positive or partial treatment response for bipolar depression: A blinded, randomized study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009;70(4):450–457. DOI:10.4088/JCP.08m04191

Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2019;33(4):502–510. 29. Altshuler LL, Post RM, Hellemann G, Leverich GS, Nolen WA, Frye MA, Keck Jr PE, Kupka RW, Grunze H, McElroy SL, Sugar CA, Suppes T. Impact of antidepressant continuation after acute positive or partial treatment response for bipolar depression: A blinded, randomized study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009;70(4):450–457. DOI:10.4088/JCP.08m04191

30. McGirr A, Vöhringer PA, Ghaemi SN, Lam RW, Yatham LN. Safety and efficacy of adjunctive second-generation antidepressant therapy with a mood stabiliser or an atypical antipsychotic in acute bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(12):1138–1146. DOI:10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30264-4

31. Ketter TA. Acute and maintenance treatments for bipolar depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2014;75(4):e10. DOI:10.4088/JCP.13010tx2c

32. El–Mallakh RS, Vöhringer PA, Ostacher MM, Baldassano CF, Holtzman NS, Whitham EA, Thommi SB, Goodwin FK, Ghaemi SN. Antidepressants worsen rapid-cycling course in bipolar depression: A STEP-BD randomized clinical trial. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015;184:318–321. DOI:10.1016/Jjad.2015.04.054

Antidepressants worsen rapid-cycling course in bipolar depression: A STEP-BD randomized clinical trial. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015;184:318–321. DOI:10.1016/Jjad.2015.04.054

33. Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, Aronson JK, Barnes T, Cipriani A, Coghill DR, Fazel S, Geddes JR, Grunze H, Holmes EA, Howes O., Hudson S, Hunt N, Jones I, Macmillan IC, McAllister–Williams H, Miklowitz DR, Morriss R, Munaf ò M, Paton C, Saharkian BJ, Saunders K, Sinclair J, Taylor D, Vieta E, Young AH. Evidence-based guidelines for treating third bipolar disorder: Revised edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J. Psychopharmacol (Oxford). 2016;30(6):495–553. DOI:10.1177/0269881116636545

34. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, Schaffer A, Bond DJ, Frey BN, Sharma V, Goldstein BI, Rej S, Beaulieu S, Alda M, MacQueen G, Milev RV, Ravindran A , O'Donovan C, McIntosh D, Lam RW, Vazquez G, Kapczinski F, McIntyre RS, Kozicky J, Kanba S, Lafer B, Suppes T, Calabrese JR, Vieta E, Malhi G, Post RM, Berk M. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Discord. 2018;20(2):97–170. DOI:10.1111/bdi.12609

Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Discord. 2018;20(2):97–170. DOI:10.1111/bdi.12609

35. Fountoulakis KN, Grunze H, Vieta E, Young A, Yatham L, Blier P, Kasper S, Moeller HJ The International College of Neuro-Psychopharmacology (CINP) Treatment Guidelines for Bipolar Disorder in Adults (CINP-BD-2017), Part 3: The Clinical Guidelines. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;20(2):180–195. DOI:10.1093/ijnp/pyw109

36. National Collaborating Center for Mental Health (UK). Bipolar Disorder: The NICE Guideline on the Assessment and Management of Bipolar Disorder in Adults, Children and Young People in Primary and Secondary Care. London: The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2014. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK498655/. Accessed December 23, 2019

37. Grunze H, Vieta E, Goodwin GM, Bowden C, Licht RW, Möller H-J, Kasper S, WFSBP Task Force On Treatment Guidelines For Bipolar Disorders. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for the Biological Treatment of Bipolar Disorders: Update 2010 on the treatment of acute bipolar depression. World J. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;11(2):81–109. DOI:10.3109/15622970903555881

The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for the Biological Treatment of Bipolar Disorders: Update 2010 on the treatment of acute bipolar depression. World J. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;11(2):81–109. DOI:10.3109/15622970903555881

38. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am. J. Psychiatry. 2002;159(4):1–50.

39. Lim PZ, Tunis SL, Edell WS, Jensik SE, Tohen M. Medication prescribing patterns for patients with bipolar I disorder in hospital settings: adherence to published practice guidelines. Bipolar Disorders. 2001;3(4):165–173. DOI:10.1034/J1399-5618.2001.30401.x

40. Baldessarini RJ, Leahy L, Arcona S, Gause D, Zhang W, Hennen J Patterns of Psychotropic Drug Prescription for U.S. Patients With Diagnoses of Bipolar Disorders. PS. 2007;58(1):85–91. DOI:10.1176/ps.2007.58.1.85

41. Freeland KN, Cogdill BR, Ross CA, Sullivan CO, Drayton SJ, VandenBerg AM, Short EB, Garrison KL. Adherence to evidence-based treatment guidelines for bipolar depression in an inpatient setting. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2015;72(23–3):S156–161. DOI:10.2146/sp150023

Adherence to evidence-based treatment guidelines for bipolar depression in an inpatient setting. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2015;72(23–3):S156–161. DOI:10.2146/sp150023

42. Rej S, Herrmann N, Shulman K, Fischer HD, Fung K, Gruneir A. Current psychotropic medication prescribing patterns in late-life bipolar disorder. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2017;32(12):1459–1465. DOI:10.1002/gps.4635

43. Wang Z , Gao K, Hong W, Xing M, Wu Z , Chen J, Zhang C, Yuan C, Huang J, Peng D, Wang Y., Lu W, Yi Z , Yu X, Zhao J, Fang Y. Guidelines Disconcordance in Acute Bipolar Depression: Data from the National Bipolar Mania Pathway Survey (BIPAS) in Mainland China. PLOS ONE 2014;9(4):96096. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0096096

44. Bjørklund L, Horsdal HT, Mors O, Østergaard SD, Gasse C Trends in the psychopharmacological treatment of bipolar disorder: a nationwide register-based study. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2016;28(2):75–84. DOI:10.1017/neu.2015.52

45. Baek JH, Ha K, Yatham LN, Chang JS, Ha TH, Jeon HJ, Hong KS, Chang SM, Ahn YM, Cho HS, Moon E, Cha B, Choi JE, Joo YH, Joo EJ, Lee SY, Park Y. Pattern of Pharmacotherapy by Episode Types for Patients With Bipolar Disorders and Its Concordance With Treatment Guidelines. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2014;34(5):577. DOI:10.1097/JCP.0000000000000175

Pattern of Pharmacotherapy by Episode Types for Patients With Bipolar Disorders and Its Concordance With Treatment Guidelines. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2014;34(5):577. DOI:10.1097/JCP.0000000000000175

46. Karanti A, Kardell M, Lundberg U, Landén M. Changes in mood stabilizer prescription patterns in bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2016;195:50–56. DOI:10.1016/Jjad.2016.01.043

47. Goldberg JF, Freeman MP, Balon R, Citrome L, Thase ME, Kane JM, Fava M. The American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology Survey of Psychopharmacologists' Practice Patterns for the Treatment of Mood Disorders. depression and anxiety. 2015;32(8):605–613. DOI:10.1002/da.22378

48. Viktorin A, Lichtenstein P, Thase ME, Larsson H, Lundholm C, Magnusson PKE, Landén M. The risk of switch to mania in patients with bipolar disorder during treatment with an antidepressant alone and in combination with a mood stabilizer. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2014;171(10):1067–1073.