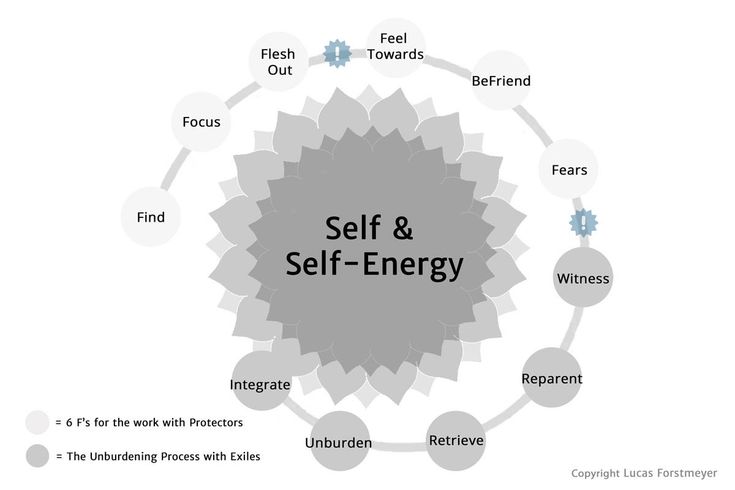

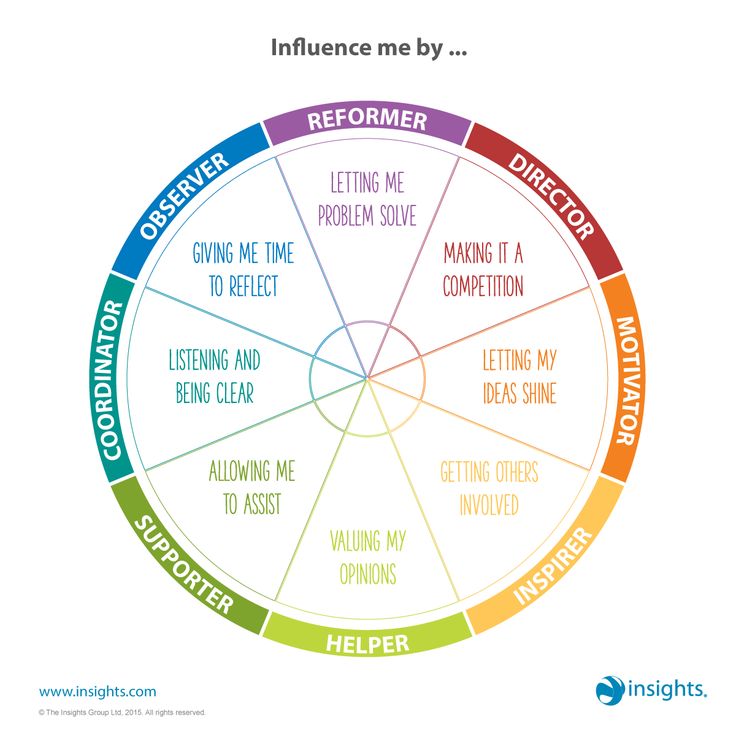

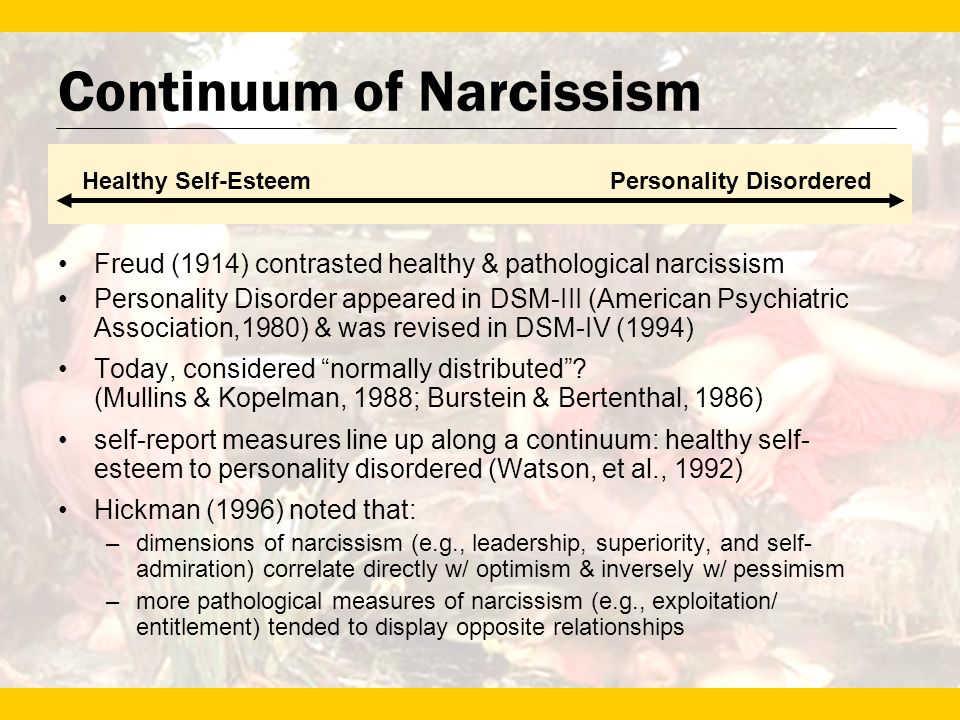

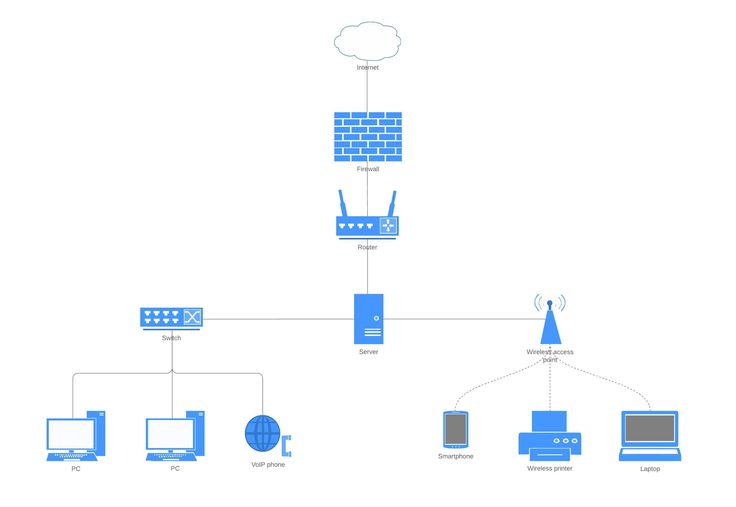

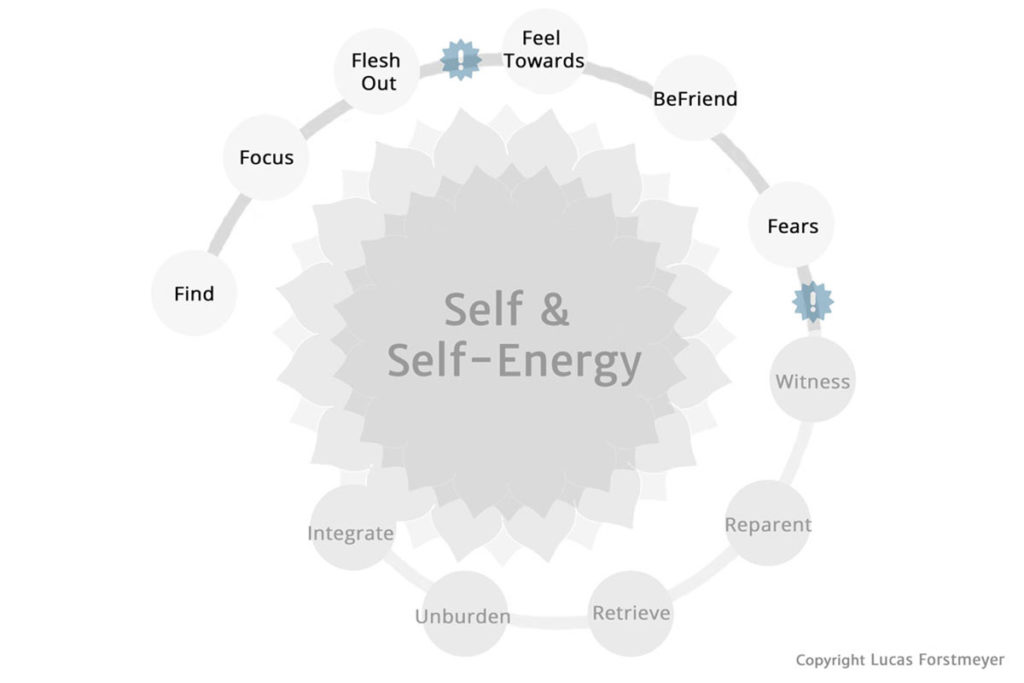

Internal family systems diagram

The Internal Family Systems Model Outline

I. BASIC ASSUMPTIONS OF THE IFS MODEL

- It is the nature of the mind to be subdivided into an indeterminate number of subpersonalities or parts.

- Everyone has a Self, and the Self can and should lead the individual's internal system.

- The non-extreme intention of each part is something positive for the individual. There are no "bad" parts, and the goal of therapy is not to eliminate parts but instead to help them find their non-extreme roles.

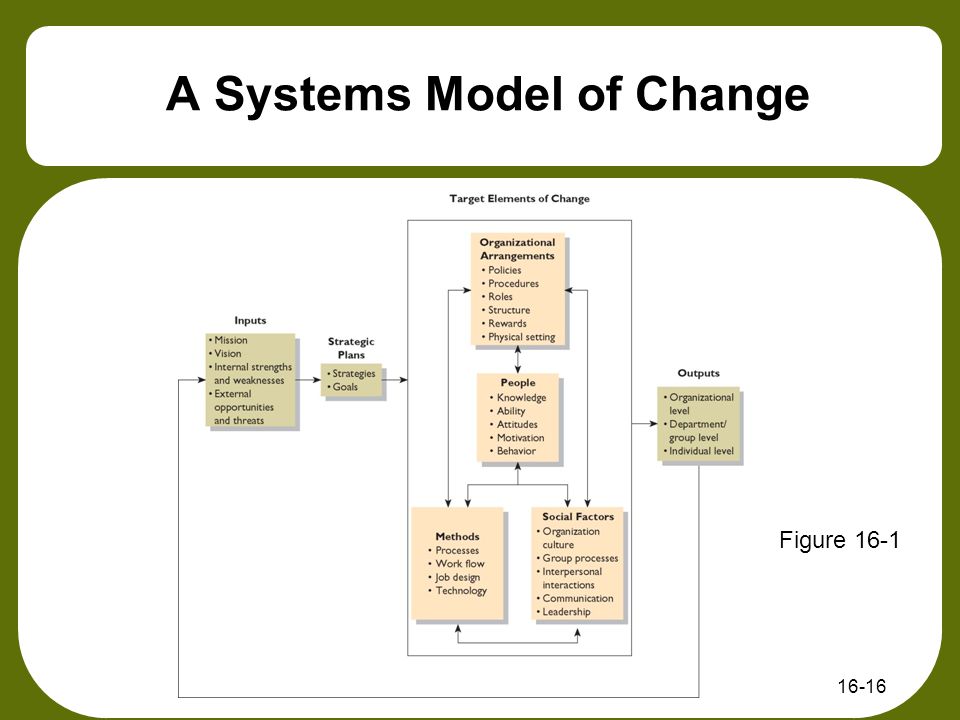

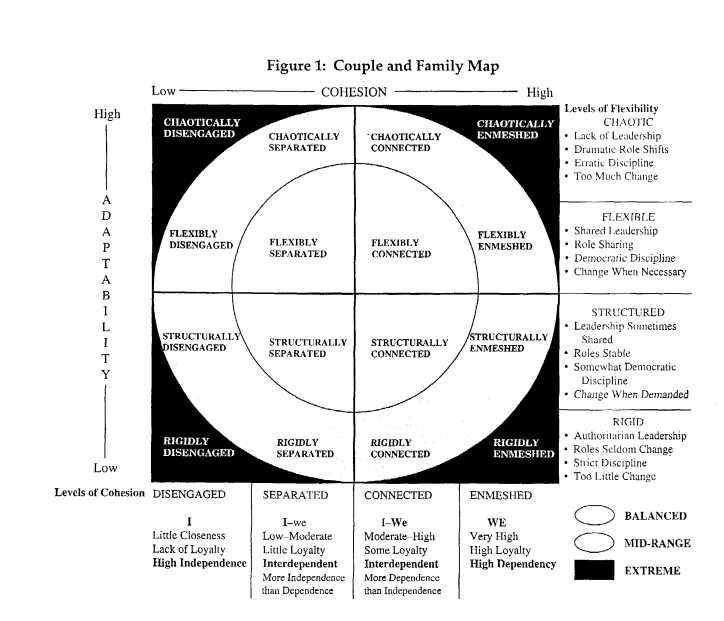

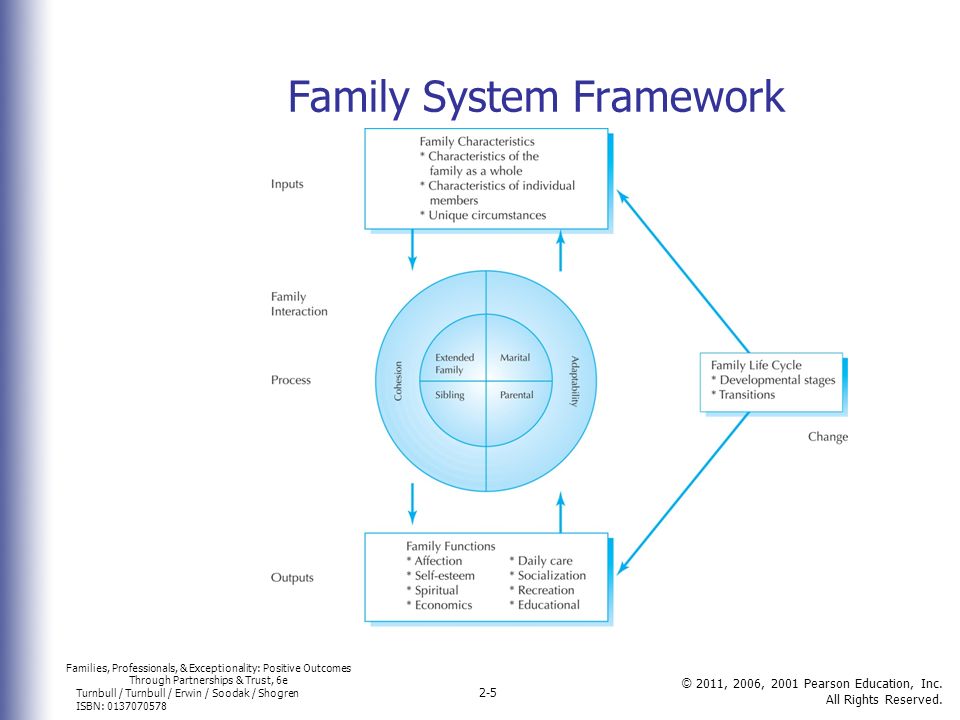

- As we develop, our parts develop and form a complex system of interactions among themselves; therefore, systems theory can be applied to the internal system. When the system is reorganized, parts can change rapidly.

- Changes in the internal system will affect changes in the external system and vice versa. The implication of this assumption is that both the internal and external levels of system should be assessed.

II. OVERALL GOALS OF THERAPY

- To achieve balance and harmony within the internal system

- To differentiate and elevate the Self so it can be an effective leader in the system

- When the Self is in the lead, the parts will provide input to the Self but will respect the leadership and ultimate decision making of the Self.

- All parts will exist and lend talents that reflect their non-extreme intentions.

III. PARTS

- Subpersonalities are aspects of our personality that interact internally in sequences and styles that are similar to the ways in which people interact.

- Parts may be experienced in any number of ways -- thoughts, feelings, sensations, images, and more.

- All parts want something positive for the individual and will use a variety of strategies to gain influence within the internal system.

- Parts develop a complex system of interactions among themselves. Polarizations develop as parts try to gain influence within the system.

- While experiences affect parts, parts are not created by the experiences. They are always in existence, either as potential or actuality.

- Parts that become extreme are carrying "burdens" -- energies that are not inherent in the function of the part and don't belong to the nature of the part, such as extreme beliefs, emotions, or fantasies. Parts can be helped to "unburden" and return to their natural balance.

- Parts that have lost trust in the leadership of the Self will "blend" with or take over the Self.

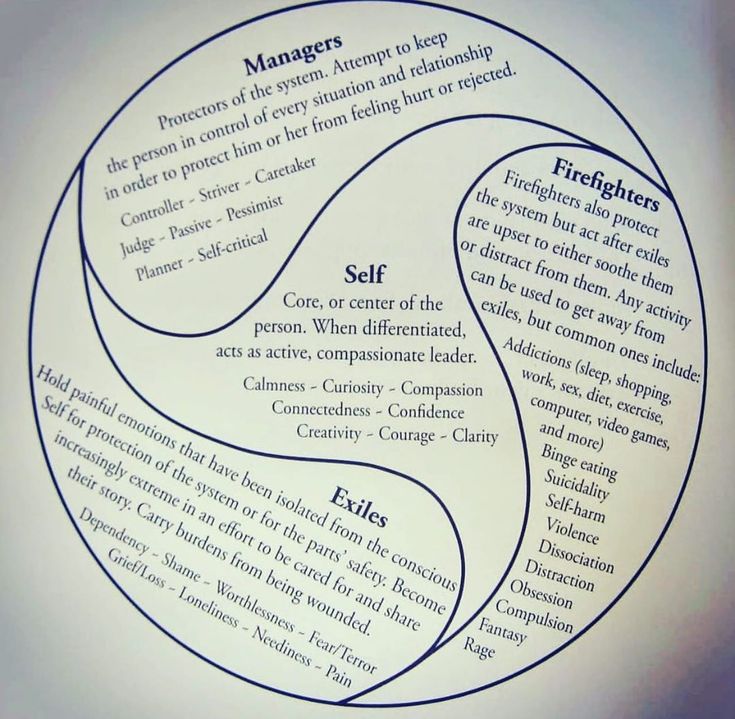

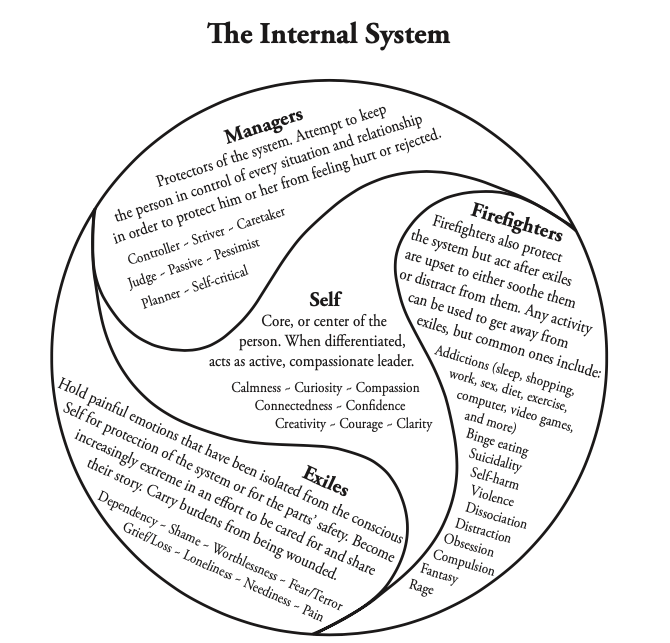

IV. SELF

- Different level of entity than the parts -- often in the center of the "you" that the parts are talking to or that likes or dislikes, listens to, or shuts out various parts

- When differentiated, the Self is competent, secure, self-assured, relaxed, and able to listen and respond to feedback.

- The Self can and should lead the internal system.

- Various levels of experience of the Self:

- When completely differentiated from all parts (Self alone), people describe a feeling of being "centered.

"

" - When the individual is "in Self" or when the Self is in the lead while interacting with others (day-to-day experience), the Self is experienced along with the non-extreme aspects of the parts.

- When completely differentiated from all parts (Self alone), people describe a feeling of being "centered.

- An empowering aspect of the model is that everyone has a Self.

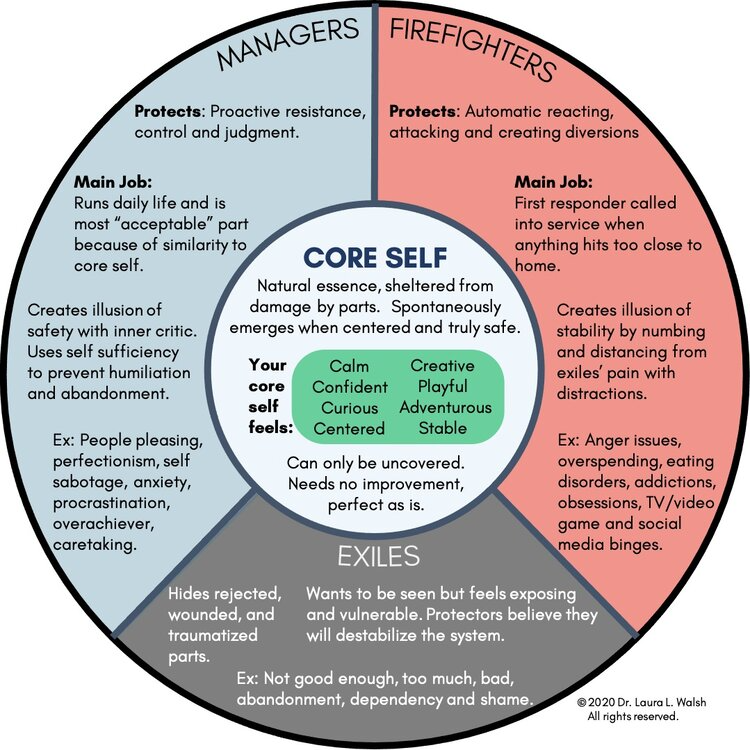

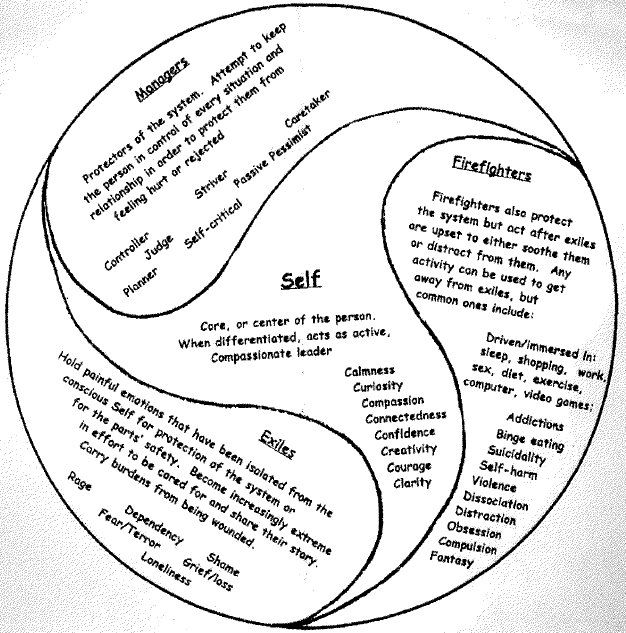

V. GENERAL GROUPS OF PARTS

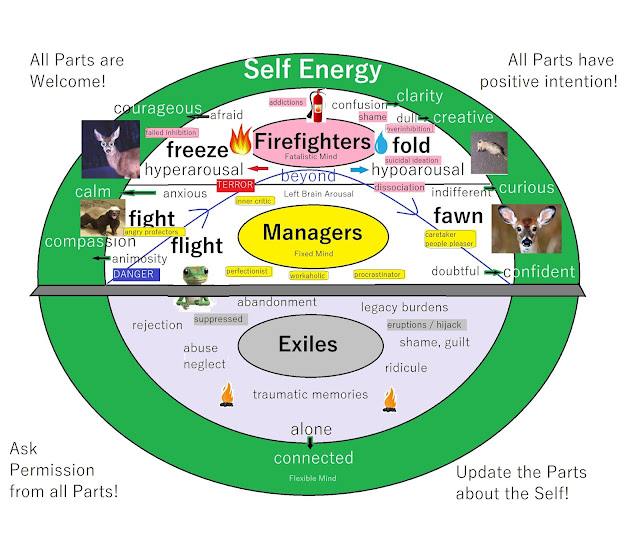

- EXILES

- Young parts that have experienced trauma and often become isolated from the rest of the system in an effort to protect the individual from feeling the pain, terror, fear, and so on, of these parts

- If exiled, can become increasingly extreme and desperate in an effort to be cared for and tell their story

- Can leave the individual feeling fragile and vulnerable

- MANAGERS

- Parts that run the day-to-day life of the individual

- Attempt to keep the individual in control of every situation and relationship in an effort to protect parts from feeling any hurt or rejection

- Can do this in any number of ways or through a combination of parts -- striving, controlling, evaluating, caretaking, terrorizing, and so on.

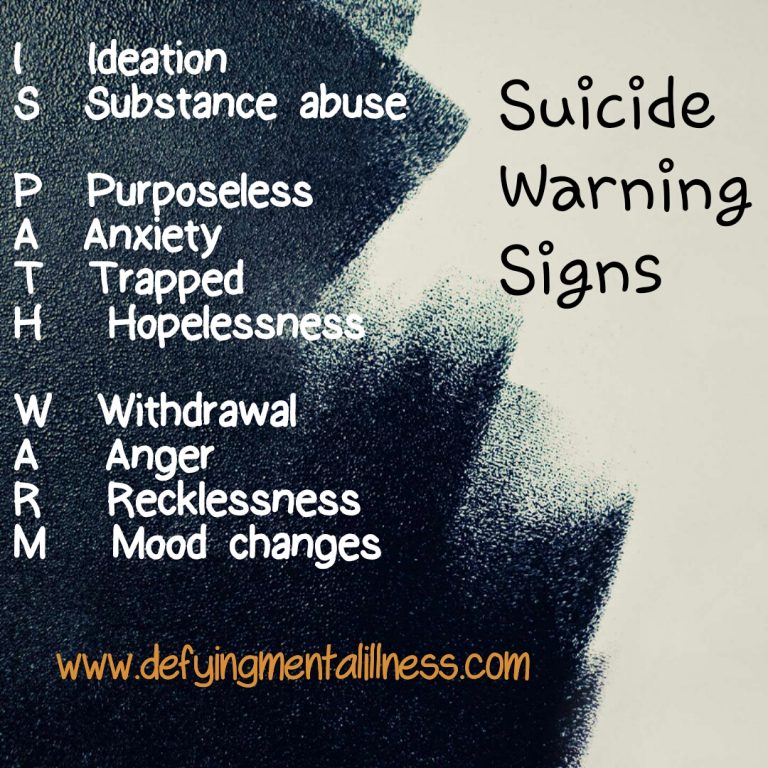

- FIREFIGHTERS

- Group of parts that react when exiles are activated in an effort to control and extinguish their feelings

- Can do this in any number of ways, including drug or alcohol use, self-mutilation (cutting), binge-eating, sex binges

- Have the same goals as managers (to keep exiles away) but different strategies

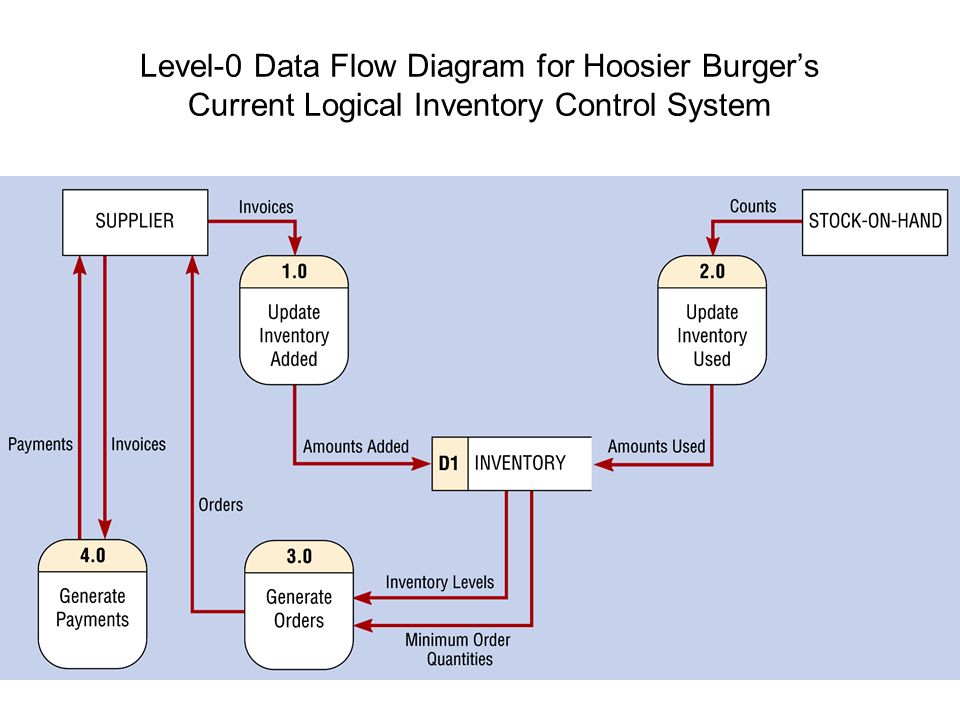

VI. BEGINNING TO USE THE MODEL

- Assess client's parts and sequences around the problem.

- Look for polarizations:

- Within individuals

- Among family members

- Look for parallel dynamics: The way you relate to your own parts parallels the way you relate to those parts of others.

- Introduce the language of the model.

- Check for individual's awareness of parts -- ask how he or she experiences the part: thoughts, feelings, sensations, images, and so on.

- When working with families, check for the family's awareness of parts in self and others.

- Make a decision about how to begin using the model: language, direct access, imagery, and so on.

- Come to agreement with client on initial goals of therapy in terms of the internal system -- create a "contract."

- Assess the fears of manager parts and value the roles of the managers; explain how the therapy can work without the feared outcomes of the managers happening.

- Inventory dangerous firefighters; work with managers' fears about triggering firefighters.

- Assess client's external context and constraints to doing this work.

VII. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL SYSTEMS

- The way you relate to your own parts parallels the way you relate to those parts of others.

- Individual's internal system affects and is affected by the external system of which he or she is a part.

- Internal and external systems often parallel each other.

VIII. WORKING WITH INDIVIDUALS

- Protective Parts

- Important to assess protective parts and work with them first.

- Develop a direct relationship with the part.

- May need to negotiate pace of work -- give the part an opportunity to talk about concerns.

- Work out a system for the part to let you know when things are moving too fast.

- Respect the concerns of the part.

- Important to assess protective parts and work with them first.

- Non-imaging techniques

- Assessing internal dialogue

- Using the IFS language

- Location/sense of a part in the body

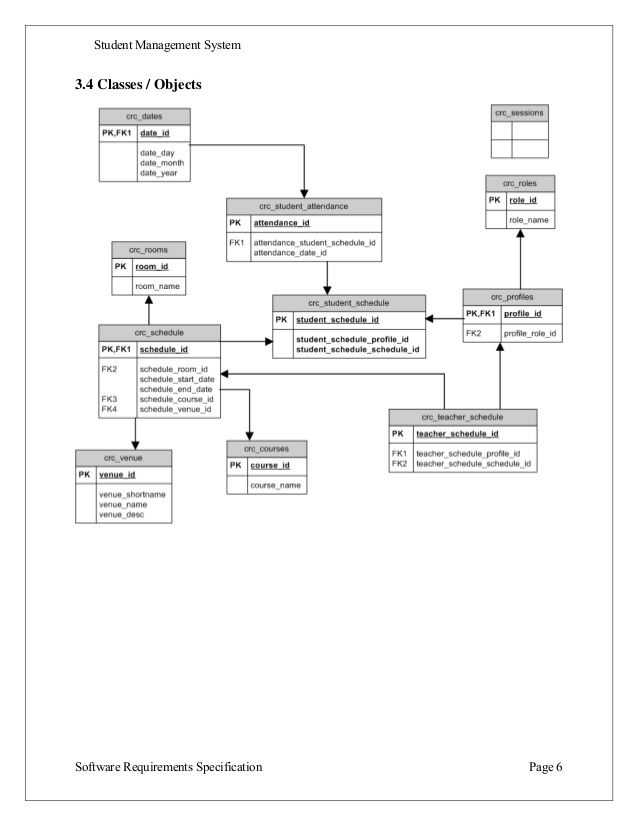

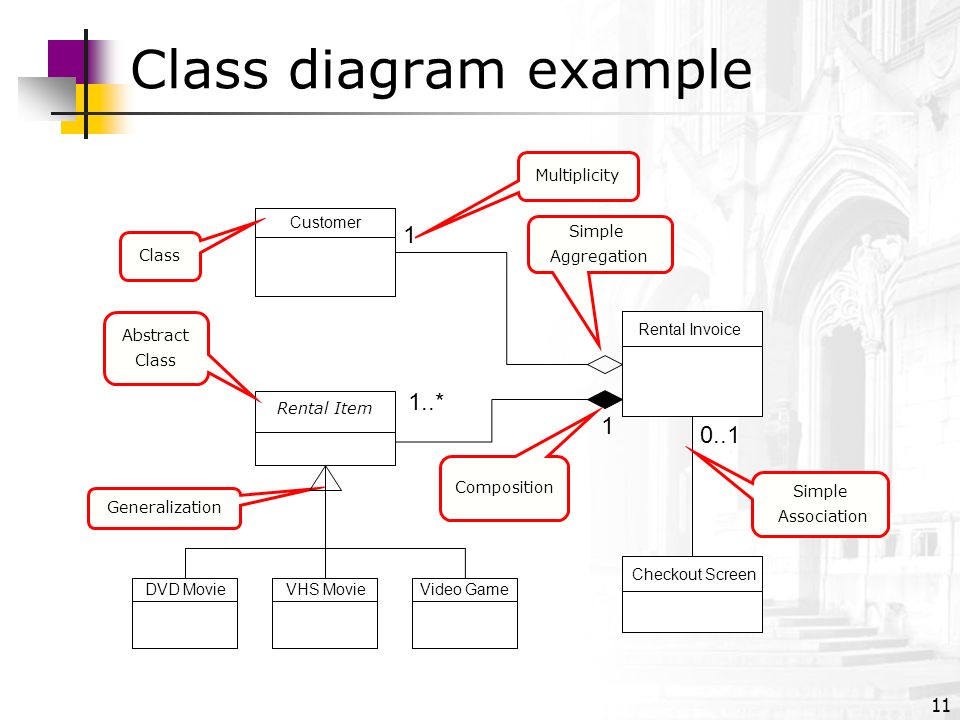

- Diagrams -- relationships among parts

- Journaling

- Direct access:

- Therapist to parts

- Self to parts

- Part to part

- Imaging

- Room technique

- Mountain or path exercise

- Going back in time with a part, then "unburdening"

- Bringing parts into the present -- "retrieval"

- Future imaging

- Working with more than one part

- Confronting abuse/significant others

- Horizon/healing place

- Use of light

- Concept of Blending: keeping the feelings of the part from overwhelming the Self

- Working with the Self to understand why/how not to blend

- Working with the part to understand why/how not to blend

- Working with young children

- Assess developmental level of child and whether need to be concrete or able to use imaging techniques

- Be creative, use modalities comfortable to child -- art, play techniques

- Children respond well to techniques that externalize parts and then involve interacting with the parts, such as sandtray, puppets, and so on.

IX. WORKING WITH FAMILIES

- Introduce IFS language (power of IFS language vs. monolithic language)

- Language is powerful in changing sequences.

- Language frees people from seeing themselves (and others) in extreme ways.

- Looking for parts that are activated in session.

- Identifying sequences (both internal and external)

- Selves working together to keep extreme parts of each family member from interfering

- Enactments

- Set up enactments of family.

- Set up enactments of sequences/relationship among parts of individual family members.

- Work with one family member while others watch.

- Establish safety: Family members not to analyze parts outside of session

- Contract not to talk about others' parts; can talk about own parts

- No matter what others are doing, individual always responsible for own parts

- Ask for reactions of others who are watching.

- Try to alternate among family members.

- Working with one member outside of family sessions

- Emphasize taking responsibility for own parts and help practice accessing Self.

- General frame of Selves working together to keep extreme parts of each family member from interfering

X. CONSTRAINTS TO THE WORK

- Therapist's parts (rational/scientific, approval, worrier, protective)

- Protective parts of client

- Protective parts of other family members

- External system unsupportive or abusive

XI. COMMON THERAPIST MISTAKES

- Working with exile before system is ready.

- Therapist assumes he/she is talking to person's Self when is talking to a part.

- Therapist thinks Self is doing the work, but it's really a part.

XII. TROUBLESHOOTING PROBLEMS

- Helping Self to distance from/unblend from parts

- Dealing with extreme parts

XIII. STRENGTHS OF THE MODEL

STRENGTHS OF THE MODEL

- Focuses on strengths: the undamaged core of the Self, the ability of parts to shift into positive roles

- IFS language provides a way to look at oneself and others differently.

- Language encourages self-disclosure and taking responsibility for behavior.

- IFS language is powerful.

- Provides a way to work with "resistance" and denial

- Ecological understanding of entire therapy system, including therapist

- Respect for individual's experience of the problem

- Clients provide the material -- the therapist doesn't have to have all the ideas.

- Therapist looks at client's Self as "co-therapist" and trusts the wisdom of the internal system.

Internal Family Systems Therapy: 8 Worksheets and Exercises

What if the idea that we each have a single personality is entirely wrong?

Instead of the one-mind view, maybe you, I, and everyone else have multiple personalities.

Richard Schwartz (2021), the creator of the Internal Family Systems (IFS) Therapy model, suggests we have all been born with many sub-minds interacting with one another.

Haven’t we all heard conflicting inner voices saying “Go for it” and “Don’t you dare” (Sweezy & Ziskind, 2013)?

This article explores how the IFS model helps treat individuals and couples by directing these inner players, while introducing several tools and techniques to help the process.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Self-Compassion Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help you increase the compassion and kindness you show yourself and give you the tools to help your clients, students, or employees show more compassion to themselves.

This Article Contains:

- What Is Internal Family Systems Therapy?

- 6 Internal Family Systems Therapy Worksheets

- Top 2 IFS Exercises for Your Sessions

- Resources From PositivePsychology.

com

com - A Take-Home Message

- References

What Is Internal Family Systems Therapy?

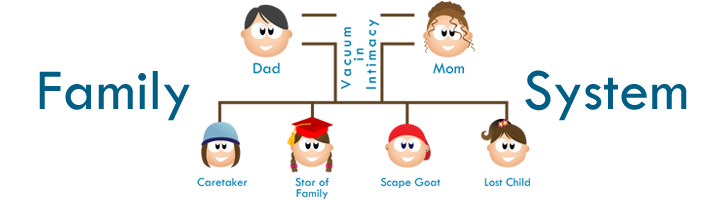

The idea that “the mind is not a singular entity or self, but is multiple, composed of parts” is at the core of Richard Schwartz’s internal family systems (IFS) model (Sweezy & Ziskind, 2013, p. xviii).

According to Schwartz (2021, p. 6), thinking involves parts “talking to each other and to you constantly about things you have to do or debating the best course of action, and so on.”

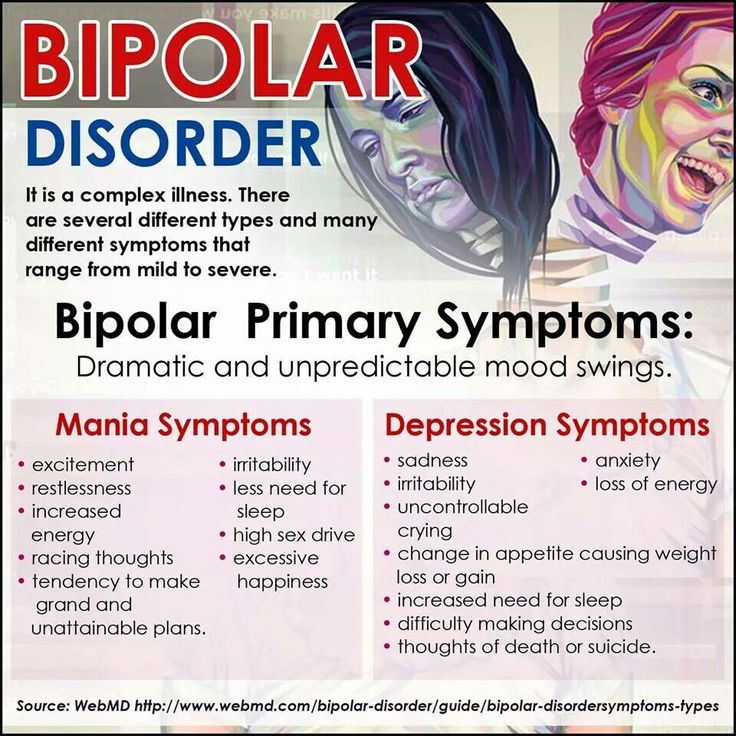

Each part has its own beliefs, feelings, and characteristics and a distinct role in the overall system. They are clustered into the following three groups (Sweezy & Ziskind, 2013; IFS Institute, n.d.):

- Managers

Managers are a protective group of parts that attempt to keep us organized and safe, running our day-to-day lives. Over time, they may push for perfectionism and even inflict harm in their pursuit of safety. - Exiles

Exiles are the injured parts of us and have typically experienced trauma. Exiled by the managers, they can become increasingly extreme, ultimately overriding the managers to become who we are.

Exiled by the managers, they can become increasingly extreme, ultimately overriding the managers to become who we are. - Firefighters

Firefighters are another form of protection that “put out the emotional fire at any cost,” often starting backfires. They do so in several ways, including unhealthy or unhelpful behavior, such as alcohol and drug abuse and eating disorders (Sweezy & Ziskind, 2013, p. xviii).

Other theories relying on the single or mono-mind model may lead us to fear or dislike ourselves, believing “we only have one mind (full of primitive or sinful aspects) that we can’t control” (Schwartz, 2021, p. 12). Therapies based on this model often require clients to “correct irrational beliefs or meditate them away” (Schwartz, 2021, p. 12).

On the other hand, Schwartz’s IFS model argues that the ego comprises multiple parts trying to keep us safe. IFS Therapy finds ways to help our ego relax, allowing those parts of our personality we have buried (exiles) to ascend, freeing memories, emotions, and beliefs associated with them (burdens) that were previously locked away (Schwartz, 2021).

With this in mind, Schwartz’s (2021, p. 32) IFS Therapy has four goals:

- To liberate parts from the roles they have been forced into, freeing them to be who they were designed to be.

- To restore faith in the self and in self-leadership.

- To re-harmonize the inner system.

- To encourage the client to become increasingly self led in their interactions with the world.

While IFS Therapy is a powerful approach for helping individuals, it can be equally successful with couples. According to Herbine-Blank (n.d.), “once the individuals in a couple have more access to Self, transformation is natural,” and they can find the space and capacity to choose a response rather than simply react to it, even if the other cannot at the time.

Each partner is encouraged to bring compassion to their wounded inner parts and heal their past, gaining control over their present (Herbine-Blank, n.d.).

6 Internal Family Systems Therapy Worksheets

IFS Therapy helps clients form a deeply satisfying relationship with themselves and others, unburdening their trauma and accessing their self-energy (Herbine-Blank, n. d.).

d.).

While there are many aspects to IFS as a theory and treatment model, the primary healing relationship “is between the client’s Self and her young, injured parts” (Sweezy & Ziskind, 2013, p. 1).

The notion of parts is crucial to the IFS model. Therapy using the IFS model addresses and communicates with these parts, attempting to help the client find balance and harmony within their mind and elevate their self to the system’s leadership. To those unfamiliar with IFS Therapy, the language and conversation style may seem unusual, involving talking directly to the different parts of the self (IFS Institute, n.d.).

The following worksheets offer a range of tools for facilitating various aspects of this powerful and complex treatment to engage with and better understand the many parts of the self (modified from Anderson, Sweezy, & Schwartz, 2017; Sweezy & Ziskind, 2013; Schwartz, 2021):

All Parts Are Welcome

The All Parts Are Welcome exercise was created by Schwartz and his team to help the client welcome all parts of their self, using their attention and a few simple questions (Anderson et al. , 2017).

, 2017).

The Six Fs

A key aspect of IFS Therapy is to “find, focus on and flesh out” the client’s protective parts and help them “unblend and notice the client’s Self” (Anderson et al., 2017, p. 93). Next, the client can recognize their feelings toward and befriend the target part, explore its fears, and invite it to do something new.

Experienced practitioners can use the Six Fs Internal Family Systems worksheet to successfully differentiate the protective parts from the self and form vital alliances.

Understanding Our Relationship With a

PartAfter identifying a part of the self, clients can explore it in greater detail to better understand whether it is doing its job.

Use the Understanding Our Relationship With a Part worksheet to identify the role and intent of the part under scrutiny by asking a series of questions:

- What is its role, and how does it help you manage your life?

- What is its relationship with other people?

- What positive intent does it have for you?

- How does it try to protect you?

- What is it trying to protect you from?

- Is it happy with its job? Or would it prefer something else?

As clients focus and make notes during the exercise, they may find that their relationship toward the part changes.

Identifying Parts of Yourself Through Drawing

It is not easy to recognize all the parts of the self. Drawing or doodling can provide a more intuitive, less concrete way to capture, describe, and show the connections between each part.

In the Identifying Parts of Yourself Through Drawing worksheet, clients can create a picture to capture the various parts of the self and how they combine.

Drawing the picture and working through this exercise can help them form a clearer understanding of the parts and their relationship to the self.

Identifying Managers and Firefighters

While managers help us plan and shape our lives and avoid discomfort and pain, firefighters rush in and try to fix the problem. We may recognize both in how we cope. For example, when life is calm, we may plan; when we’re hectic or stressed, we may eat or drink too much.

The Identifying Managers and Firefighters Using IFS Therapy worksheet helps identify manager and firefighter parts using the senses and asking a series of questions, including:

- What bodily sensations accompany the part?

- How do you feel regarding each part?

- How does each part feel about you?

It should be clear from the answers whether the part is a manager or a firefighter.

What the Self Is and Isn’t in IFS Therapy

Having used IFS Therapy with many clients to explore their self, Schwartz (2021) identified eight Cs engaged in self-energy and self-leadership shared by almost everyone.

The What the Self Is and Isn’t in IFS Therapy worksheet explores the eight Cs, encourages the client to notice the quality in themselves, and asks what each means to them:

- Curiosity

- Calm

- Confidence

- Compassion

- Creativity

- Clarity

- Courage

- Connectedness

Considering each one will make you feel more connected to humanity. And “when people sense how connected they are to humanity, they feel more curious about others and have more courage to help them” (Schwartz, 2021, p. 93).

Top 2 IFS Exercises for Your Sessions

Richard Schwartz’s (2021) latest book, No Bad Parts, is an accessible read for those interested in his IFS approach to therapy, clarifying the nature of parts and the techniques to uncover them. According to Schwartz (2021. p. 17), “each part is like a person with a true purpose” that can be uncovered.

According to Schwartz (2021. p. 17), “each part is like a person with a true purpose” that can be uncovered.

The following exercises are two of the most powerful techniques in this fascinating and powerful model (simplified from Schwartz, 2021):

The path of self

This exercise uses visualization to explore self and self-energy, using the metaphor of a journey.

Ask the client to perform the following steps:

- Find a comfortable position and begin by taking slow, deep breaths.

- Imagine yourself meeting your parts at the beginning of a path.

- Ask the parts to wait there as you head off on a journey.

- Notice how they react. Are they afraid? Some days, they may not want you to go. And that’s okay. You can wait for another day to continue.

- If it’s okay to proceed, head out on your imagined journey.

- As you progress, if you find you are still thinking or watching yourself, then some parts are likely to have remained with you.

See if they are willing to stay behind. Repeat as many times as required.

See if they are willing to stay behind. Repeat as many times as required. - As you remove parts, feel yourself becoming lighter, moving toward pure awareness without thought.

- You should begin to experience, among other things, clarity, a sense of wellbeing, and confidence.

- Invite the energy you are feeling into your body.

- Pause and experience what it is like to have so much self in your body.

- When you’re ready, take some deep breaths and return your focus to the room.

Repeat this exercise regularly, trying to remember how it feels throughout your day.

Fire drill

The following reflective exercise is a valuable way to revisit parts in life and learn self-leadership through practice and experience.

Ask the client to perform the following steps:

- Picture someone in your life (past or present) who triggers anger or sadness in you.

- Imagine them in a room from which they cannot leave.

- Watch the person from outside the room through a one-way mirror. You can see them, but they cannot see you.

- Now have them do or say the things that upset you.

- Notice what happens to your body and mind as your protector part kicks in (your muscles, heart rate, breathing, thoughts, and emotions).

- Now look at the person through the eyes of your protector. Reassure your protector that you will not be entering that room.

- Encourage the protector to recognize that you are not at risk, so it can stand down.

- See if your protector is prepared to separate its energy from you. Encourage it to take the energy away.

- Now recheck yourself. What changes do you notice in your muscles, heart rate, breathing, thoughts, and emotions?

- How does the person in the room look now?

- How would it feel if you were to go into the room and be with that person, self led rather than accompanied by the protector?

- Ask the protector if it can begin to trust you.

If not, why not?

If not, why not? - When you’re ready, thank the protector for the support it has given you and the new trust it has in you.

- Take some deep breaths and return your focus to the room.

“If your protector did step to the side, you probably noticed a big shift” (Schwartz, 2021, p. 130). Repeating the exercise can help clients learn about the parts that protect and how vulnerable they have previously been.

Resources From PositivePsychology.com

Self-compassion is a vital aspect of IFS Therapy. We have various resources that can help clients look at themselves with more kindness.

Why not download our free self-compassion tool pack and try out the powerful tools contained within? Here are some examples:

- Self-Care Vision Board

Use this exercise to help clients create a visual representation to increase self-care and self-compassion. - Learning to Rate Behavior Rather Than the Self

This exercise separates the evaluation of behavior from that of the self to accept that we do not have to define ourselves by our weaknesses.

Other free resources include:

- I Will Survive

Reflect on a past event and identify the strengths that helped you cope. - Easing Empathy Distress

Feeling another’s pain or sadness can lead to empathy distress. This tool helps turn empathy into compassion.

More extensive versions of the following tools are available with a subscription to the Positive Psychology Toolkit©, but they are described briefly below:

- From Inner Critic to Inner Coach Meditation

This tool aims to help clients differentiate between their threat defense system (i.e., their inner critic) and their caregiving system (i.e., their inner coach), learning to let go of the former.

Ask the client to:

-

- Practice mindful meditation, bringing to mind a recent time when they were critical or judgmental of themselves.

- Notice their inner critic and how it makes them feel.

- Now imagine replacing the inner critic with an inner coach.

- What would it say to them, and how would they feel?

- Embracing Your Humanness

We use this tool to help people cultivate self-compassion by developing an appreciation for common humanity in a group setting.

Guide the members of the group through the following steps:

-

- Step one – Write down one self-criticism on a piece of paper.

- Step two – Collect all the folded notes.

- Step three – Choose and share a note at random.

- Step four – Discuss self-criticism within the group and share common experiences.

The aim is to recognize that each person in the group is not alone in having self-critical thoughts.

- 17 Self-Compassion Exercises

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others develop self-compassion, check out this collection of 17 validated self-compassion tools for practitioners. Use them to help others create a kinder and more nurturing relationship with the self.

A Take-Home Message

The internal family systems model proposes that the mind is not a singular entity or self but is composed of multiple parts that try to keep us safe (Sweezy & Ziskind, 2013).

IFS Therapy uses self-compassion to encourage buried parts of our personality to ascend, freeing memories, emotions, and previously locked-away beliefs.

Not only that, it enables clients to unburden trauma, access self-energy, and form deeply satisfying relationships with themselves and others.

While IFS is a complex, sometimes unlikely, theory, it does provide a valuable model for therapy, healing the relationship between the client’s self and their “young, injured parts” (Sweezy & Ziskind, 2013, p. 1).

The treatment offers hope to clients wishing to find balance and harmony within their mind and facilitate the self to regain control.

Why not try out some of the worksheets and exercises with your clients to help the self, rather than the therapist, become the primary, caring attachment figure necessary to heal the client’s injured parts?

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Self-Compassion Exercises for free.

Don’t forget to download our three Self-Compassion Exercises for free.

- Anderson, F., Sweezy, M., & Schwartz, R. (2017). Internal family systems skills training manual: Trauma-informed treatment for anxiety, depression, PTSD & substance abuse. PESI.

- Herbine-Blank, T. (n.d.). Couples & marriage counseling with internal family systems therapy. IFS Institute. Retrieved November 18, 2021, from https://ifs-institute.com/resources/articles/couples-marriage-counseling-internal-family-systems-therapy

- IFS Institute. (n.d.). The internal family systems model outline. Retrieved November 18, 2021, from https://ifs-institute.com/resources/articles/internal-family-systems-model-outline

- Schwartz, R. C. (2021). No bad parts: Healing trauma and restoring wholeness with the internal family systems model. Sounds True.

- Sweezy, M., & Ziskind, E. L. (2013). Internal family systems therapy: New dimensions.

Routledge.

Routledge.

New from Scientific World Publishing!

Internal family systems. System skills training manual.

Treatment of anxiety, depression, PTSD, and the effects of substance abuse in trauma survivors.

Authors - Frank G. Anderson, Martha Sweezy, Richard S. Schwartz.

Scientific editor of the book - Chernikov Alexander Viktorovich.

Foreword by Science Editor.

If you are interested in counseling psychology or psychotherapy, then the idea of working with parts of the personality is clearly not new to you. More than a hundred years have passed since Assagioli's psychosynthesis (one of the first models in this field), and many types of therapy use the idea of subpersonalities. Some of them, such as Gestalt therapy and psychodrama, use the phenomenon of the plurality of the psyche without creating special classifications of parts of the self. Others go much further, and their theories of internal structure are much more sophisticated. They talk about different types of internals and, accordingly, different protocols for working with them. One such highly developed and researched model is Richard Schwartz's Internal Systems Therapy.

Others go much further, and their theories of internal structure are much more sophisticated. They talk about different types of internals and, accordingly, different protocols for working with them. One such highly developed and researched model is Richard Schwartz's Internal Systems Therapy.

What is the advantage of this approach? What is its attraction for professionals? The uniqueness of Schwartz's approach is that he combined the ideas of family therapy with the concept of a plurality of personality, introducing the idea of a systemic approach. Schwartz's concept is most radical in recognizing subpersonalities as separate characters, special characters that live inside us and form an inner family. Such a view allows not only to directly build dialogues with the parts, but also to trace the cycles of interaction between them, to take into account their influence on each other. As a result, work with the client becomes more gentle and the therapist encounters less resistance.

Most approaches to working with subpersonalities use chairs as a way to highlight and recognize them. Richard Schwartz uses what he calls internal communication or "insight" more often. He, as a family therapist and a follower of Minukhin's structural therapy, found that if we do a simple action - draw a line between parts, for example, ask one part to give space for contact with another part, then the core of the personality, the internal leader of the system, is revealed. Schwartz called this instance Self. He believes that Self is present in all categories of clients, even the most traumatized. The problem here is not its absence, but its greater fusion with the extreme protective parts of the Self.

Recognizing the existence of this inner leader and interacting with him makes therapy especially graceful and collaborative. In fact, the presence of this instance means the discovery of an internal system of self-healing. Self does not need to be taught to be confident, conscious and compassionate, it is not necessary to cultivate a Healthy adult, as is customary, for example, in Schema therapy. You just need to give Self space and use its inherent healing potential. Then the separation of parts, acquaintance and strengthening of contact with this inner leader becomes the main strategy of the therapist. And the therapy here actually turns into a joint co-therapy Self of the client and the therapist himself.

You just need to give Self space and use its inherent healing potential. Then the separation of parts, acquaintance and strengthening of contact with this inner leader becomes the main strategy of the therapist. And the therapy here actually turns into a joint co-therapy Self of the client and the therapist himself.

The book "Internal Family Systems" is the third book on this method in Russian. Ten years have passed since the publication of the first book by Nauchny Mir*, and a large number of domestic specialists working in this model have been formed. Actively undergoes training and development of the community of IFS therapists. This manual is a very structured tutorial, where the protocol for working in this model is described in steps. Of particular note is the ability of the authors to draw parallels between in-depth work with parts and the latest advances in neuroscience in the field of brain research.

The authors give many examples of the use of techniques and discussions with clients about where and why to move in therapy. This book is very reader friendly and really rich in ideas. Of course, it cannot replace a full-fledged training in the method, but I am sure that it will be a reference book for specialists and all those interested in working with parts of the personality.

This book is very reader friendly and really rich in ideas. Of course, it cannot replace a full-fledged training in the method, but I am sure that it will be a reference book for specialists and all those interested in working with parts of the personality.

Chernikov Alexander Viktorovich - Candidate of Sciences in Psychology, Chairman of the Expert Council of the Society of Family Counselors and Psychotherapists, Head of Family Psychotherapy Training Programs at the Institute of Family and Group Therapy, Professor at the Moscow Institute of Psychoanalysis.

#psychology #psychotherapy #richardschwartz #familysystems #internalfamilysystems

Systemic family therapy of subpersonalities

The main thing is to get along with yourself

Voltaire

Many prominent minds, in search of a definition of happiness, came to the conclusion that its basis is in harmony with oneself, in the feeling of a truly ongoing process of self-organization while realizing the potential inherent in nature.

However, each of us knows the state of uncertainty, the impossibility of making a choice, or the state of internal disharmony - when both decisions seem important, and neither can be missed, or vice versa, neither decision is suitable. Treat yourself with a new purchase or save money? Satisfy your evening desire to eat something sweet or abstain and take care of your figure? Or even more serious questions: stay in an unhappy marriage, but keep a full family for children, or divorce, following your desire, but as a consequence of facing children's emotions in connection with their experience of divorce?

It also happens that having made a decision, we continue to doubt whether we did the right thing. You can simultaneously think about how brave / brave I am and blame myself for the possible consequences of the decision I made, or not dare to act and criticize myself for being shy. As if one part of us supports and is proud, while the other blames and doubts the decision made.

So, 20-year-old (let's call him) Ivan came to me for psychological help. He described the difficulties that he found it difficult to voice his true thoughts. For example, his girlfriend allowed herself unpleasant remarks about him in front of mutual acquaintances. It was easier for him to laugh it off than to let her know how unpleasant it really was for him to hear her say this in front of everyone. And after such situations, he reproached himself for insecurity and lack of courage, for not being able to “here and now” be real and tell the truth. In everyday life, Ivan spent a lot of energy maintaining conflict-free communication. Anyone he knew would rate him as a positive and cheerful person. However, Vanya himself, being alone with himself, was sad and lonely.

A visit to a psychologist created a space for Ivan where he could be himself and say what you think. Although it took time and work on trust. When my contact with Vanya took place, he began to share the details of his experiences. For convenience, I suggested switching to the language of subpersonalities, the client liked this idea ...

For convenience, I suggested switching to the language of subpersonalities, the client liked this idea ...

Psychologist Richard Schwartz, working with people with eating disorders, noticed that before an overeating attack, several internal voices sound in the heads of clients, as if there were several personalities inside. Being a student of Salvador Minukhin, the creator of the structural approach to family therapy, and based on the idea of a plurality of the psyche, Richard Schwartz created a therapeutic approach called systemic family therapy of subpersonalities.

Subpersonalities are internal parts of us. They appear at various moments of our lives in difficult, sometimes traumatic situations. To cope with such a situation, the psyche comes up with a new algorithm of actions (or part = subpersonality that is responsible for this algorithm), which becomes in a number of other ways from our arsenal of reactions. With an optimal picture, a person is able to control such parts. But if a person has an experience when he did not cope with the situation, subpersonalities cease to trust him and begin to live their own uncontrolled life, appearing where a person would not want to see them. These subpersonalities still strive to fulfill the function for which they were created - to demonstrate a coping reaction.

But if a person has an experience when he did not cope with the situation, subpersonalities cease to trust him and begin to live their own uncontrolled life, appearing where a person would not want to see them. These subpersonalities still strive to fulfill the function for which they were created - to demonstrate a coping reaction.

.... So, I began to ask what was happening with Vanya, at the very moment when his girlfriend was sarcastic at him in front of mutual acquaintances. It turned out that he was very angry, but he kept his anger to himself. Translating into the language of subpersonalities, one part of Vanya was angry with her friend, and the other part stood guard over this anger and was responsible for ensuring that the anger did not break out and no one saw it. Recall that when Ivan came home, he scolded himself. Thus, there was a third part, criticizing ...

It turns out that each person can have about a hundred such subpersonalities - this is the figure of the accepted norm.

…I asked Ivan which part brings him the most discomfort, who would he like to deal with first. The containment part became the target.

What did this part want for Vanya? It turned out that she was implementing the task of adaptation. Her main intentions were to avoid conflicts with others. It was very important not to quarrel with anyone, otherwise ... Here is the most important point: what was this part afraid of? She was afraid of Vanya's loneliness and rejection by his friends as a reaction to his expressing his opinion. This part remembers how lonely Vanya was at school, when he allowed his anger to come out, clashed with classmates and, as a result, was rejected by most of the class. Then he felt like a "black sheep", and it was a difficult period of his life. The restraining part could not allow him to touch these difficult feelings again, so she made a decision about Vanya's behavior instead of him - to restrain himself and be silent!

To find care in the actions of the restraining part was amazing for Ivan! He saw the situation from the other side: this is not a cowardly part, this is a protective, anticipatory part. It remained to negotiate with her so that he would take over the functions of protection against loneliness. So that he himself could assess the threat of the situation and choose the appropriate behavior for it.

It remained to negotiate with her so that he would take over the functions of protection against loneliness. So that he himself could assess the threat of the situation and choose the appropriate behavior for it.

I must say that it is always difficult to act in a new way, in a different way: if only because it is less safe: the result is unpredictable. But actions "in a different way" lead to a new result. Vanya dared to tell his girlfriend how he felt in that situation. The girlfriend practically did not relent, but it was a precedent when Ivan told her how he felt and what he really thought. The inner critic, seeing Vanya's new bold behavior, subsided.

In the process of therapeutic work, authority is returned to the core of the personality, and a new sphere of responsibility is offered to the subpersonalities.

Schwartz considers subpersonalities as parts of the internal family system, assuming that they obey the laws of family functioning. This understanding opened up a special look at the methods and goals of therapeutic intervention.