Nutrition mental health research

Nutrition and mental health: What's the link?

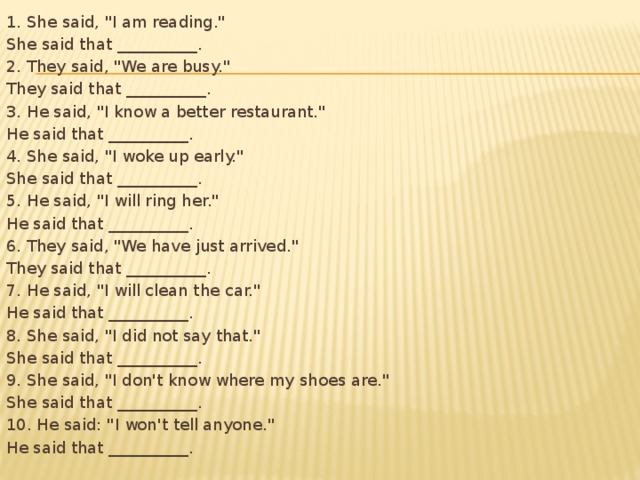

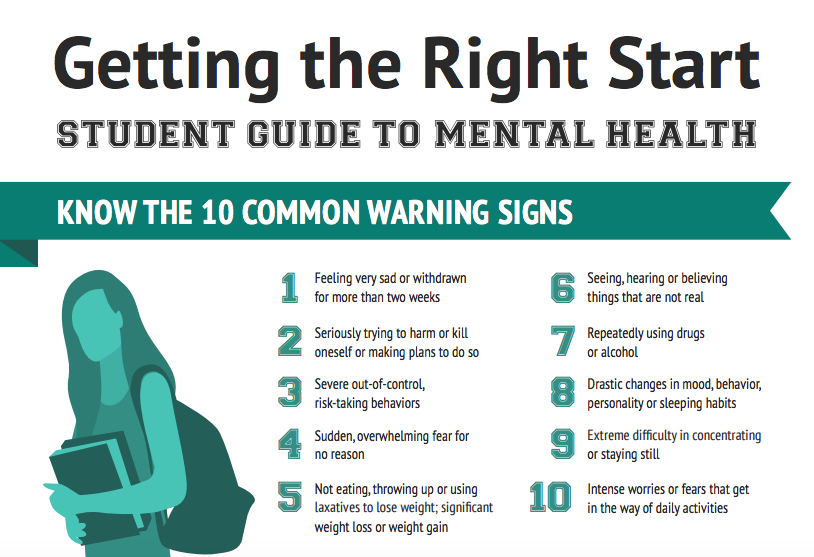

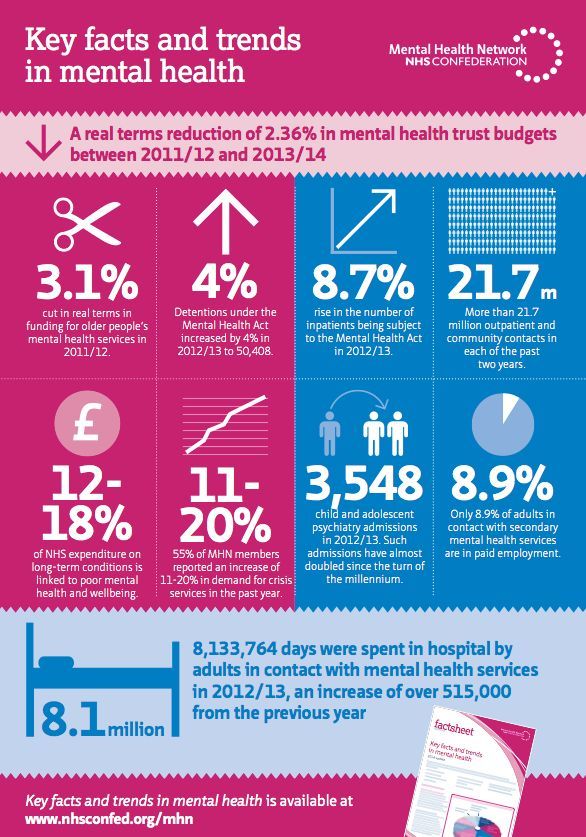

Anxiety and depression are among the most common mental health conditions worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), depression could be one of the top health concerns in the world by 2030.

Therefore, it is not surprising that researchers continue to search for new ways to reduce the impact of mental health conditions, rather than relying on current therapies and medications.

Nutritional psychiatry is an emerging area of research specifically looking at the role of nutrition in the development and treatment of mental health problems.

The two main questions that researchers are asking in relation to the role of nutrition in mental health are, “Does diet help prevent mental health conditions?” and, “Are nutrition interventions helpful in the treatment of these conditions?”

Article highlights:

Several observational studies have shown a link between overall diet quality and the risk of depression.

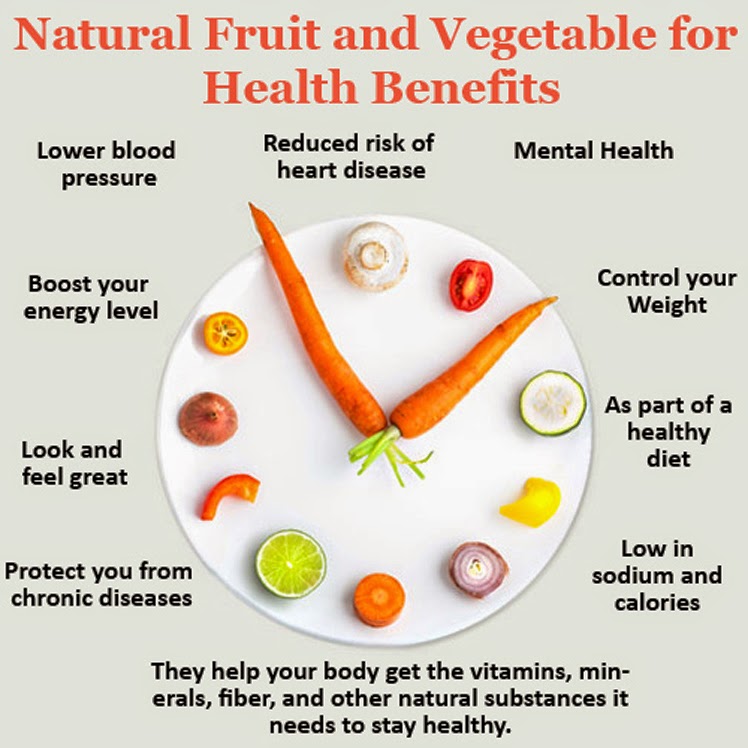

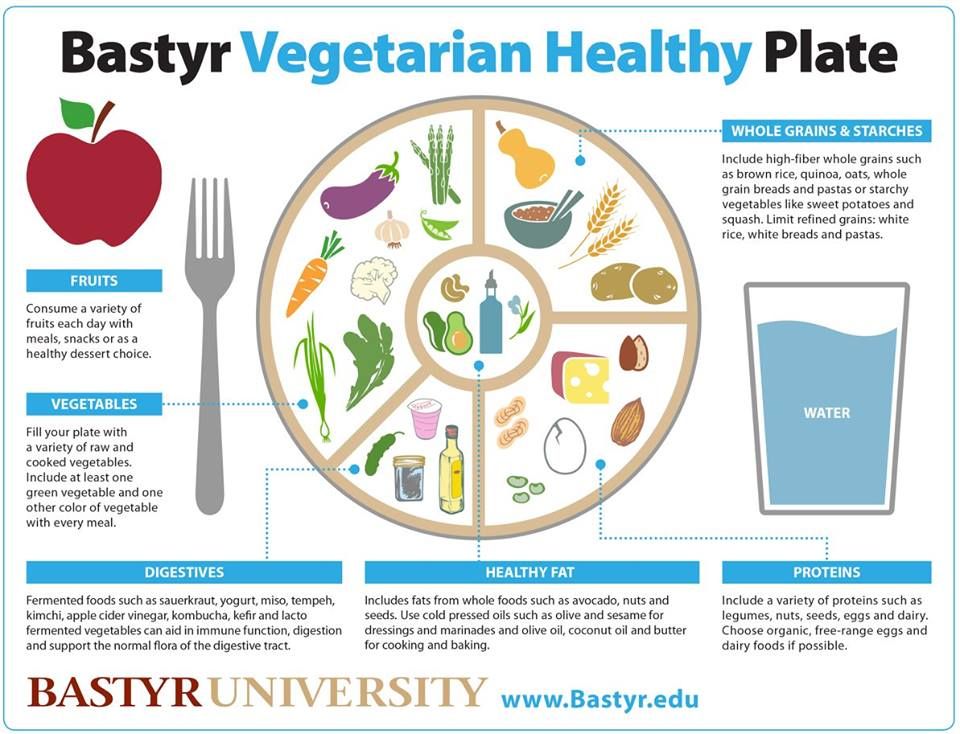

For example, one review of 21 studies from 10 countries found that a healthful dietary pattern — characterized by high intakes of fruit, vegetables, whole grains, olive oil, fish, low fat dairy, and antioxidants, as well as low intakes of animal foods — was associated with a reduced risk of depression.

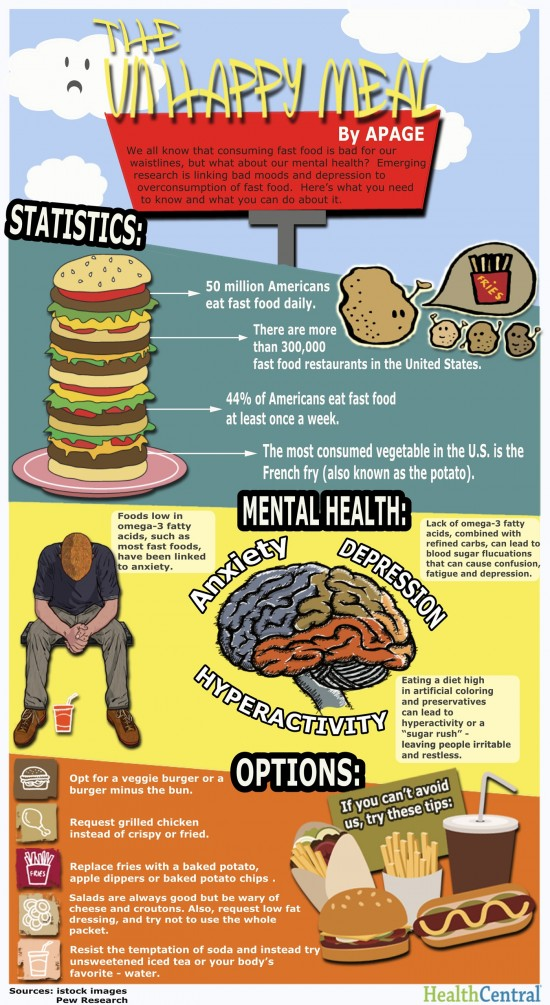

Conversely, a Western-style diet — involving a high intake of red and processed meats, refined grains, sweets, high fat dairy products, butter, and potatoes, as well as a low intake of fruit and vegetables — was linked with a significantly increased risk of depression.

An older review found similar results, with high compliance with a Mediterranean diet being associated with a 32% reduced risk of depression.

More recently, a study looking at adults over the age of 50 years found a link between higher levels of anxiety and diets high in saturated fat and added sugars.

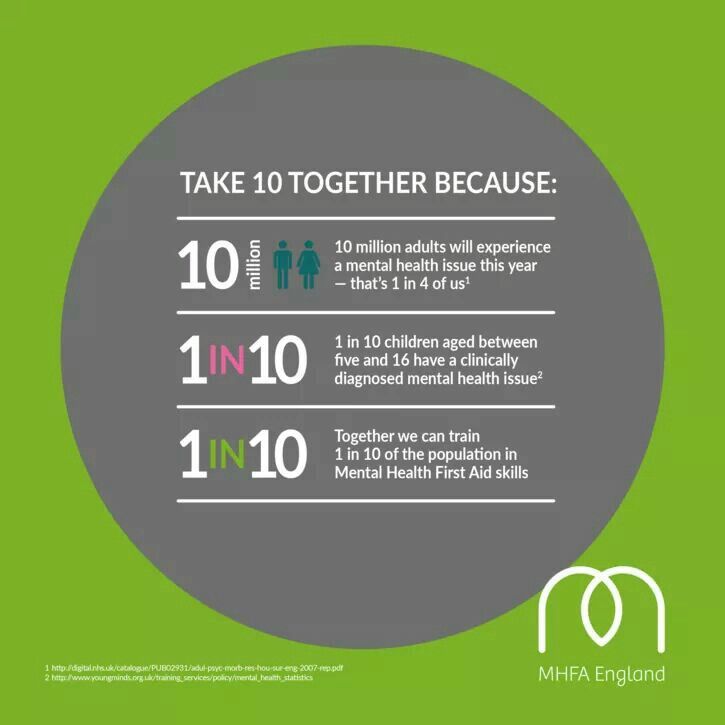

Interestingly, researchers have noted similar findings in kids and teenagers.

For example, a 2019 review of 56 studies found an association between a high intake of healthful foods, such as olive oil, fish, nuts, legumes, dairy products, fruits, and vegetables, and a reduced risk of depression during adolescence.

However, it is important to keep in mind that while observational studies can show an association, they cannot prove cause and effect.

Also, even with randomized controlled trials, there are several limitations when it comes to nutrition research studies, including difficulties with accurately measuring food intake.

Researchers often rely on participants recalling what they have eaten in previous days, weeks, or months, but no one’s memory is perfect.

The research into whether dietary interventions can help treat mental health problems is relatively new and still quite limited.

The SMILES trial was one of the first randomized controlled trials to examine the role of diet in the treatment of depression.

Over 12 weeks, 67 individuals with moderate or severe depression received either dietary counseling or social support in addition to their current treatment.

The dietary intervention was similar to a Mediterranean diet, in that it emphasized vegetables, fruits, whole grains, oily fish, extra virgin olive oil, legumes, and raw nuts. It also allowed for moderate amounts of red meat and dairy.

At the end of the study, those in the diet group had significantly greater improvements in depression symptoms. These improvements remained significant even when the scientists accounted for confounding variables, including body mass index (BMI), physical activity, and smoking.

Furthermore, only 8% of individuals in the control group achieved remission, compared with 32% of those in the diet group.

Although these results seem promising, the SMILES study was a small, short-term study. As a result, larger, longer term studies are necessary to apply its findings to a larger population.

Replicating the findings is important because not all research agrees with them. For instance, in a study that recruited 1,025 adults with overweight or obesity and at least mild depressive symptoms, researchers investigated the impact of both a multinutrient supplement and food-related behavioral activation on mental health outcomes.

The scientists found no significant difference in depressive episodes compared with a placebo after 12 months.

In the same year, though, a meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled studies did find that dietary interventions significantly reduced symptoms of depression, but not those of anxiety.

It is, therefore, difficult to draw solid conclusions from the existing body of research, particularly as the type of dietary intervention under investigation has varied greatly among studies.

Overall, more research is needed on the topic of specific dietary patterns and the treatment of mental health conditions. In particular, there is a need for a more standardized definition of a healthful diet, as well as for larger, long-term studies.

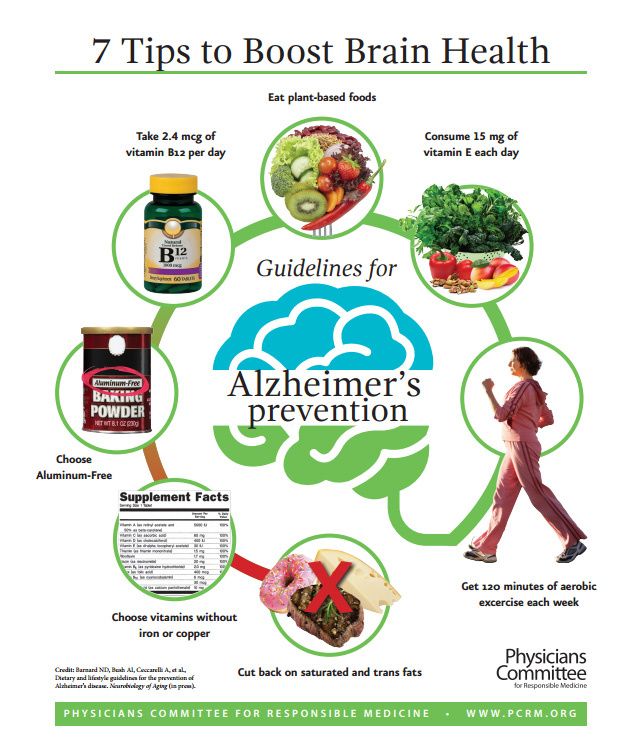

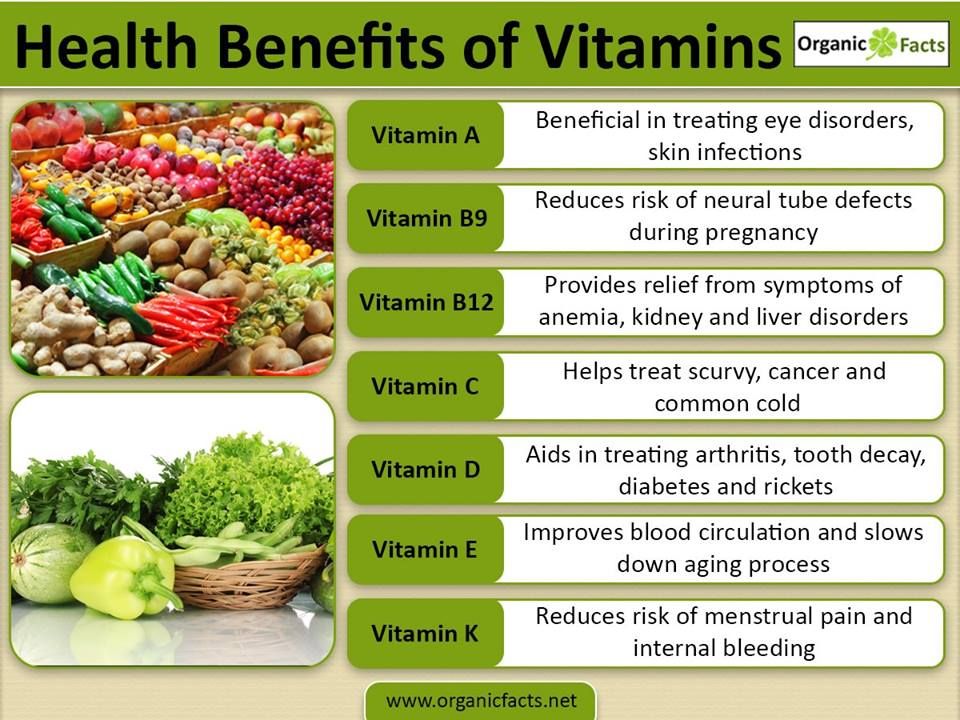

In addition to dietary patterns, scientists are interested in the potential effects that individual nutrients in the form of dietary supplements might have on mental health.

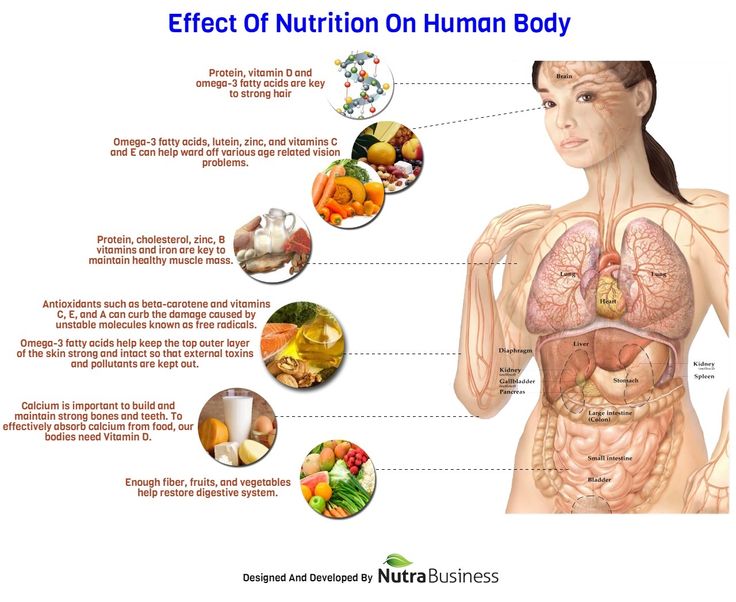

Scientists have found links between low levels of certain nutrients — such as folate, magnesium, iron, zinc, and vitamins B6, B12, and D — and worsening mood, feelings of anxiety, and risk of depression.

However, there is inconclusive evidence on whether consuming extra amounts of these nutrients in supplement form offers further benefits for mental health.

For instance, if someone is deficient in magnesium, for example, taking a magnesium supplement might help improve symptoms. However, if someone is getting adequate amounts of magnesium in their diet, it is unclear whether taking a supplement will provide any benefits.

Omega-3 fatty acids are essential fats that play a key role in brain development and cell signaling. An article in Frontiers in Physiology discusses how they reduce levels of inflammation.

Due to their anti-inflammatory effects and importance in brain health, scientists have investigated omega-3s for their potential effects on mental health.

While more research is still needed, in 2018 and 2019, reviews of randomized controlled trials found omega-3 supplements to be effective in the treatment of anxiety and depression in adults.

However, as with vitamin and mineral supplements, it remains unclear whether omega-3 supplementation can help improve mood in most individuals or whether it is primarily effective in those with the lowest intake of omega-3s.

Overall, when it comes to taking supplements for mental health, there is still a lot we do not know, including what the optimal doses are for various populations and the long-term safety and effectiveness.

Therefore, experts recommend acquiring the majority of these nutrients through a healthful and varied diet. Anyone who is concerned that they are unable to meet their nutrient needs through diet alone should speak with a doctor to discuss whether supplements may be helpful.

How much protein do you need to build muscle?

By Lindsey DeSoto, RDN, LD

Not all plant-based diets are the same: Junk veggie food and its impact on health

By Amber Charles Alexis, MSPH, RDN

Is it better to eat several small meals or fewer larger ones?

By Lindsey DeSoto, RDN, LD

While there is a need for further research, observational studies suggest, overall, that there is a link between what people eat and their mental health. Why nutrition may have this effect is still unknown, though.

There are several theories on how diet may influence mood or the risk of conditions such as depression and anxiety.

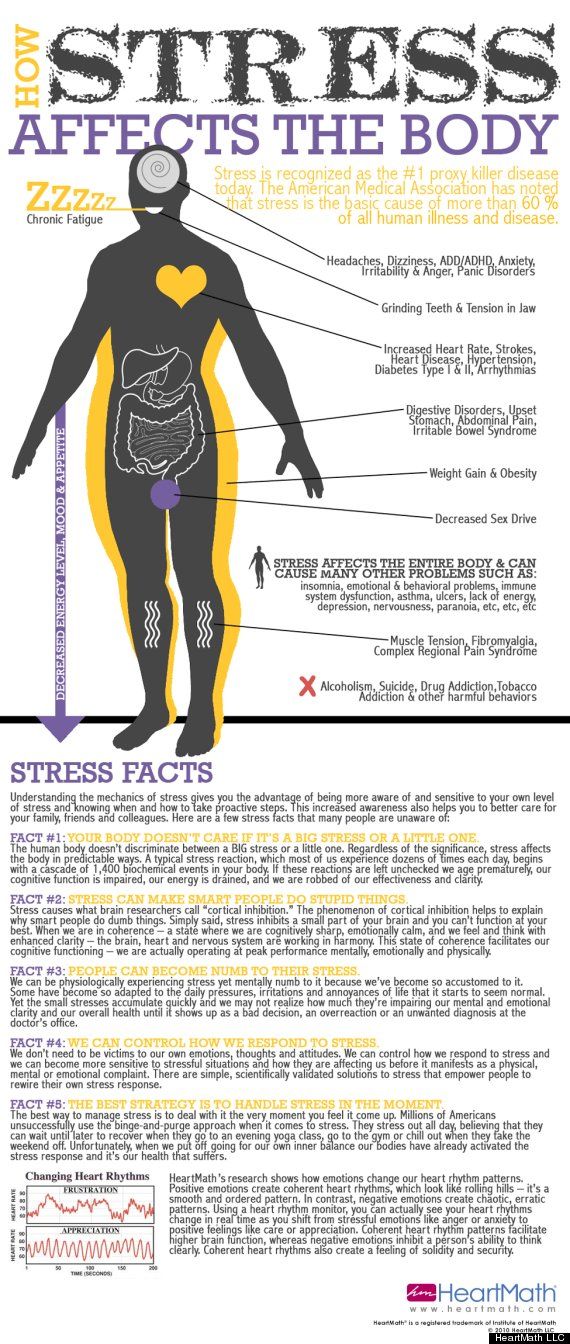

Some scientists believe that the inflammatory effects of certain dietary patterns might help explain the relationship between diet and mental health.

Several mental health conditions appear to have links with increased levels of inflammation. The authors of journal articles in Frontiers in Immunology and Current Neuropharmacology discuss this relationship.

The authors of journal articles in Frontiers in Immunology and Current Neuropharmacology discuss this relationship.

For example, diets associated with benefits for mental health tend to be high in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and healthful fats — all of which are foods rich in anti-inflammatory compounds.

A review of observational studies supports this theory, as diets high in antioxidants and anti-inflammatory foods were associated with a reduced risk of depression.

Still, the exact relationship between diet, inflammation, and alterations in mental health is not well-understood.

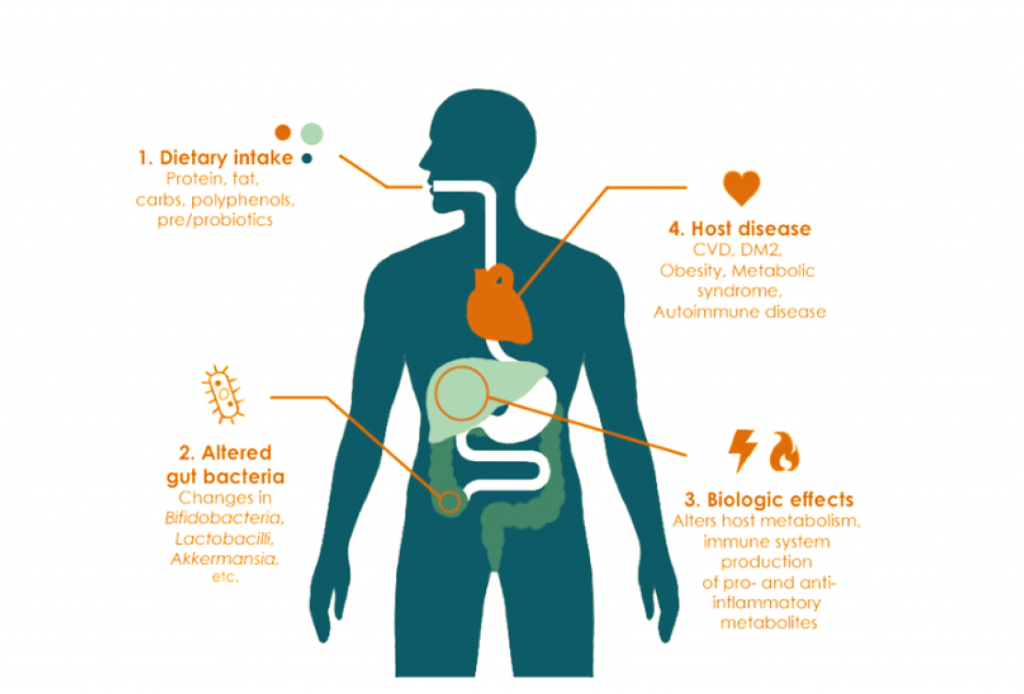

Another possible explanation is that diet may affect the bacteria in the gut, which people often refer to as the gut microbiome.

Ongoing research has found a strong link between gut health and brain function. For example, healthy bacteria in the gut produce approximately 90% of the neurotransmitter serotonin, which affects mood.

Furthermore, early research shows a potential link between a healthy gut microbiome and lower rates of depression.

As diet plays a major role in the health and diversity of the gut microbiome, this theory is a promising explanation for how what we eat may be affecting our mental well-being.

Finally, there is the possibility that diet plays a more indirect role in mental health.

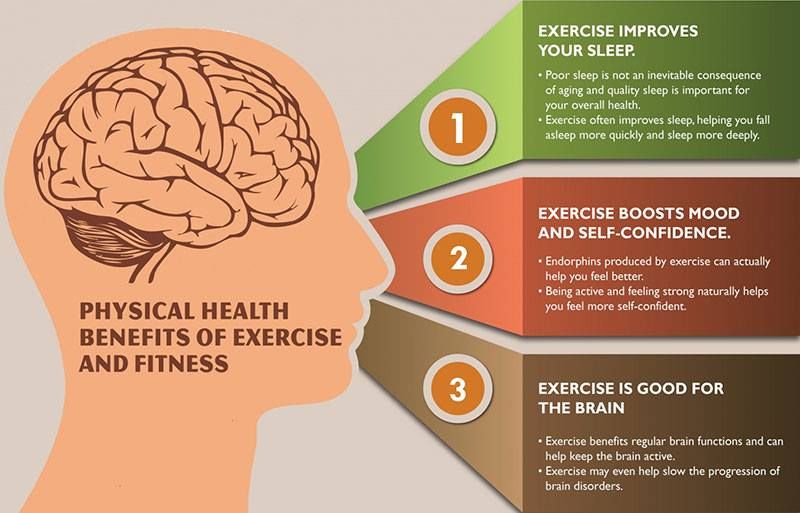

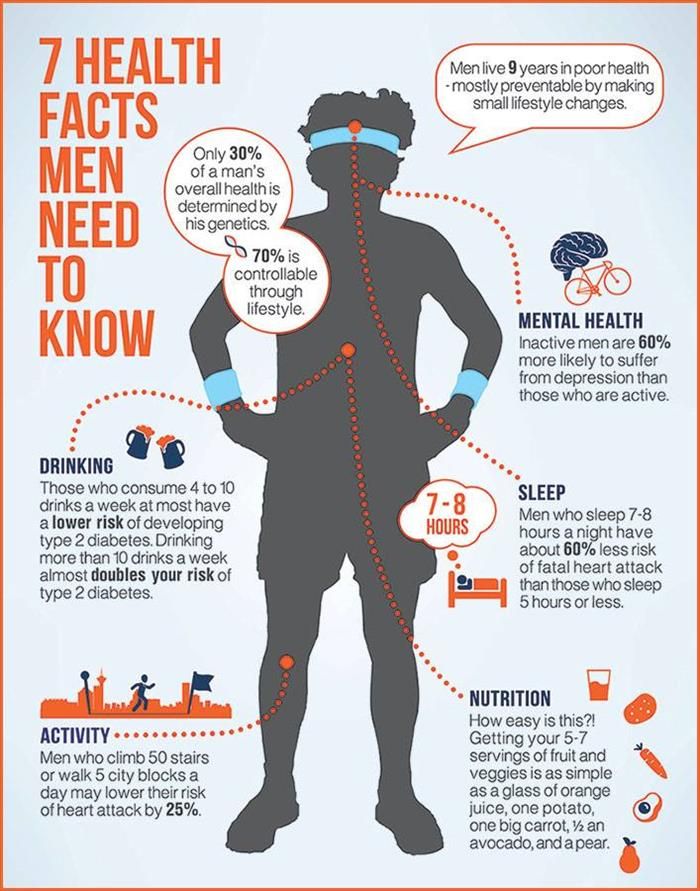

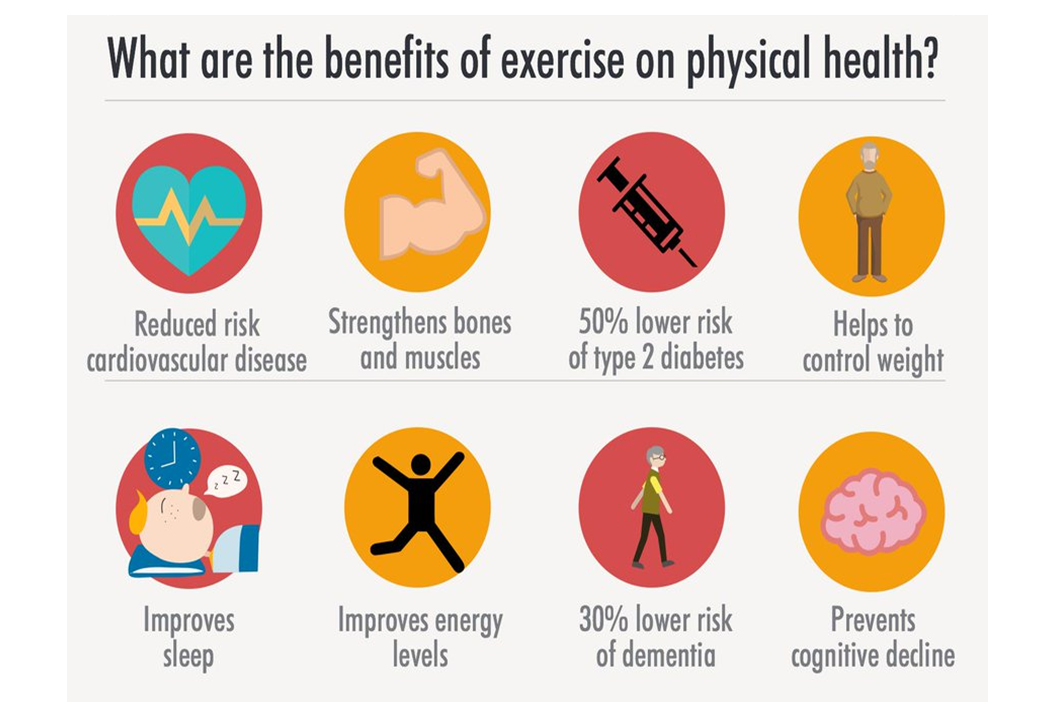

It may be that individuals with healthful diets are more likely to engage in behaviors that are also linked with a reduced risk of mental health conditions, such as engaging in regular physical activity, practicing good sleep habits, and refraining from smoking.

It is important to keep in mind that many factors can influence both eating habits and mental health.

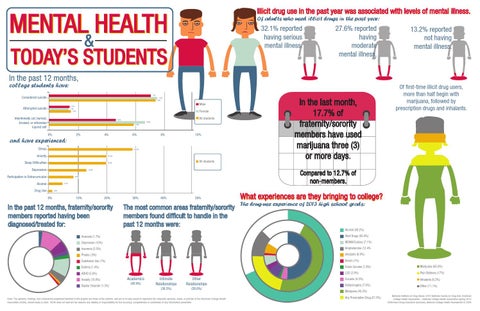

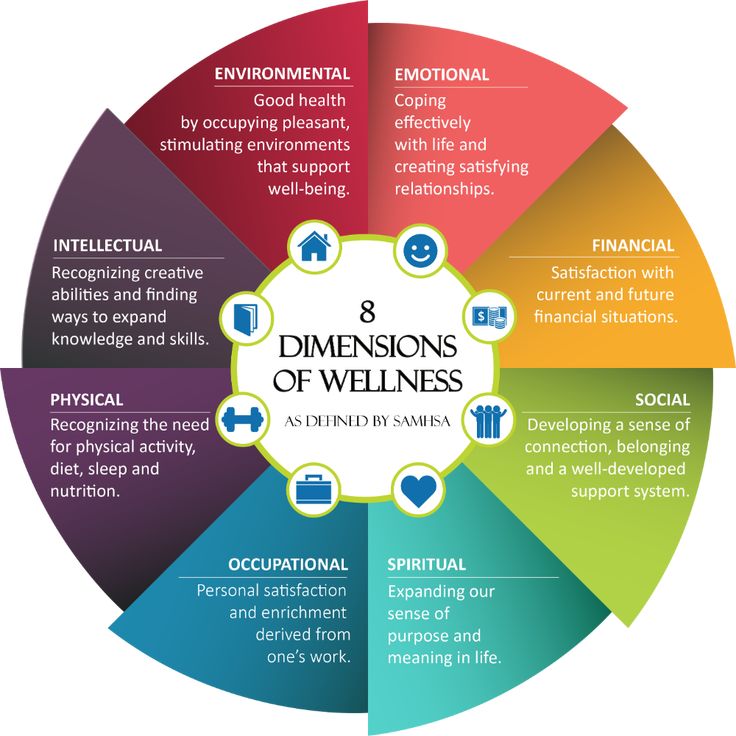

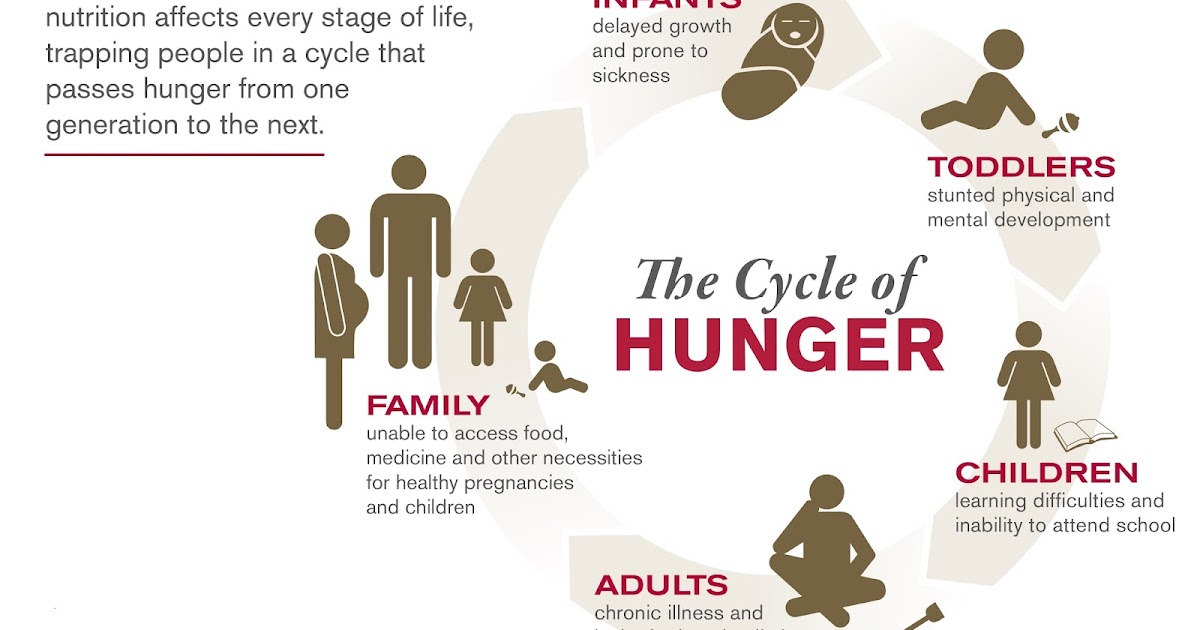

According to MentalHealth.gov, factors that can contribute to mental health conditions include biological factors, such as genetics, life experiences, and family history. Socioeconomic status can also affect mental health, as can access to food and overall diet quality.

Mental health can, in turn, affect eating habits. For example, it is not uncommon to turn to less healthful foods, such as sweets or highly processed snack foods, when feeling angry or upset.

Similarly, many antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications can increase appetite and cravings. In both of these situations, struggling with mental health can make adhering to a healthful diet more difficult.

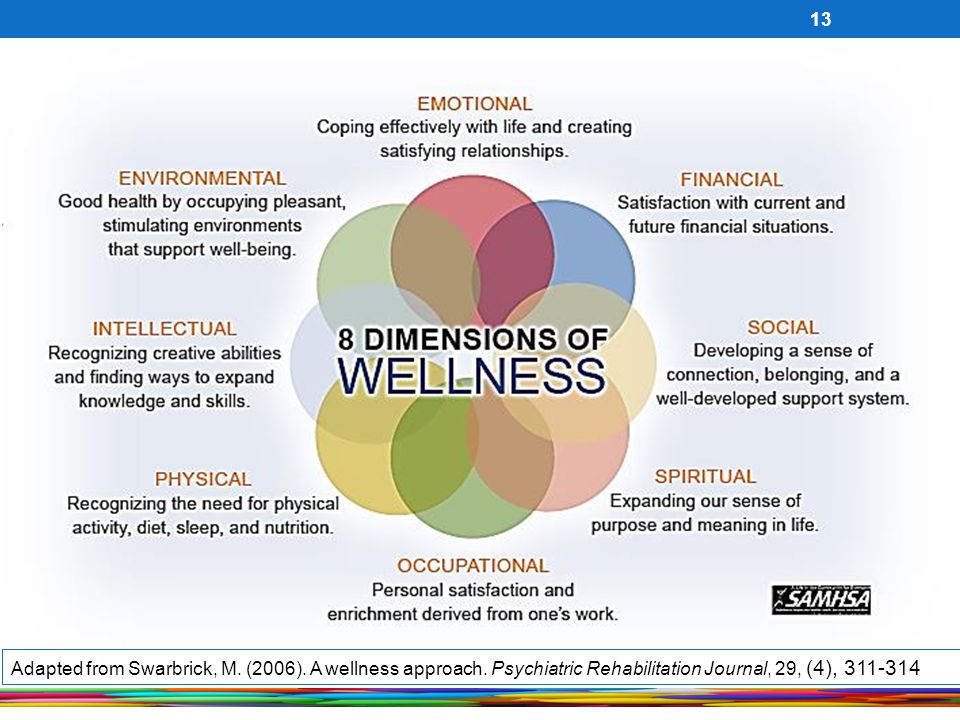

Overall, while diet may be an important factor for mental health, it is important to remember that many other aspects of life can also contribute to mood.

The study of nutrition and how it affects mental health is ongoing.

And while more research is needed, current studies suggest that we may have some influence over our mental health through our food choices.

Still, we need to keep in mind that diet is just one piece of the much more complex topic that is mental health.

As a result, it is important for anyone who is experiencing depression or anxiety symptoms or has general concerns about their mental well-being to work with a trusted healthcare provider to develop a personalized treatment plan.

Food for Thought 2020: Food and mood: how do diet and nutrition affect mental wellbeing?

BMJ. 2020; 369: m2382.

2020; 369: m2382.

Published online 2020 Jun 29. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2382

Food for Thought 2020

, research fellow,1,2, assistant professor,3,4, researcher,5, researcher,6,7,8 and , professor9,10

Author information Copyright and License information Disclaimer

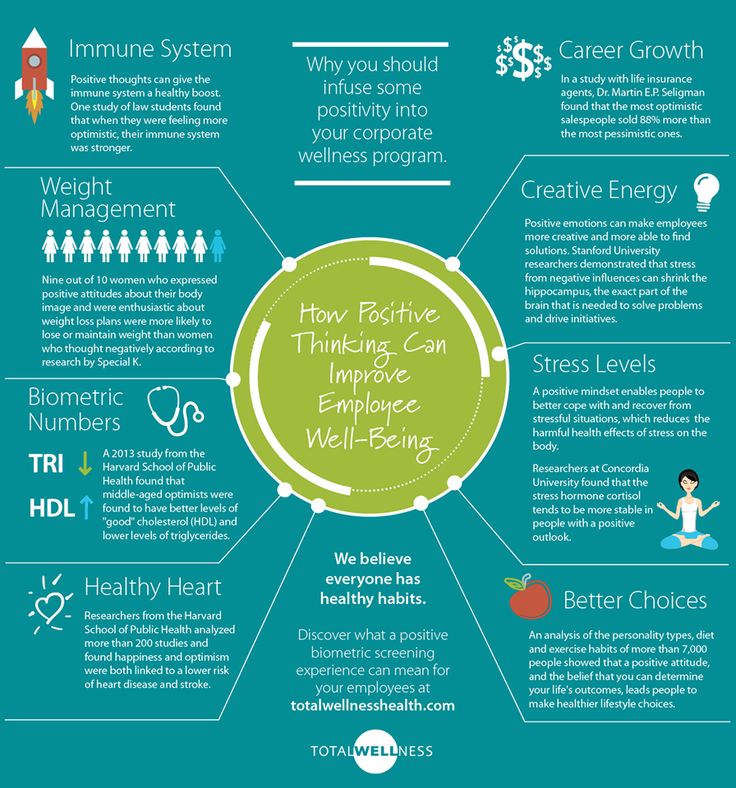

Poor nutrition may be a causal factor in the experience of low mood, and improving diet may help to protect not only the physical health but also the mental health of the population, say Joseph Firth and colleagues

Key messages

Healthy eating patterns, such as the Mediterranean diet, are associated with better mental health than “unhealthy” eating patterns, such as the Western diet

The effects of certain foods or dietary patterns on glycaemia, immune activation, and the gut microbiome may play a role in the relationships between food and mood

More research is needed to understand the mechanisms that link food and mental wellbeing and determine how and when nutrition can be used to improve mental health

Depression and anxiety are the most common mental health conditions worldwide, making them a leading cause of disability. 1 Even beyond diagnosed conditions, subclinical symptoms of depression and anxiety affect the wellbeing and functioning of a large proportion of the population.2 Therefore, new approaches to managing both clinically diagnosed and subclinical depression and anxiety are needed.

1 Even beyond diagnosed conditions, subclinical symptoms of depression and anxiety affect the wellbeing and functioning of a large proportion of the population.2 Therefore, new approaches to managing both clinically diagnosed and subclinical depression and anxiety are needed.

In recent years, the relationships between nutrition and mental health have gained considerable interest. Indeed, epidemiological research has observed that adherence to healthy or Mediterranean dietary patterns—high consumption of fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes; moderate consumption of poultry, eggs, and dairy products; and only occasional consumption of red meat—is associated with a reduced risk of depression.3 However, the nature of these relations is complicated by the clear potential for reverse causality between diet and mental health (). For example, alterations in food choices or preferences in response to our temporary psychological state—such as “comfort foods” in times of low mood, or changes in appetite from stress—are common human experiences. In addition, relationships between nutrition and longstanding mental illness are compounded by barriers to maintaining a healthy diet. These barriers disproportionality affect people with mental illness and include the financial and environmental determinants of health, and even the appetite inducing effects of psychiatric medications.4

In addition, relationships between nutrition and longstanding mental illness are compounded by barriers to maintaining a healthy diet. These barriers disproportionality affect people with mental illness and include the financial and environmental determinants of health, and even the appetite inducing effects of psychiatric medications.4

Open in a separate window

Hypothesised relationship between diet, physical health, and mental health. The dashed line is the focus of this article.

While acknowledging the complex, multidirectional nature of the relationships between diet and mental health (), in this article we focus on the ways in which certain foods and dietary patterns could affect mental health.

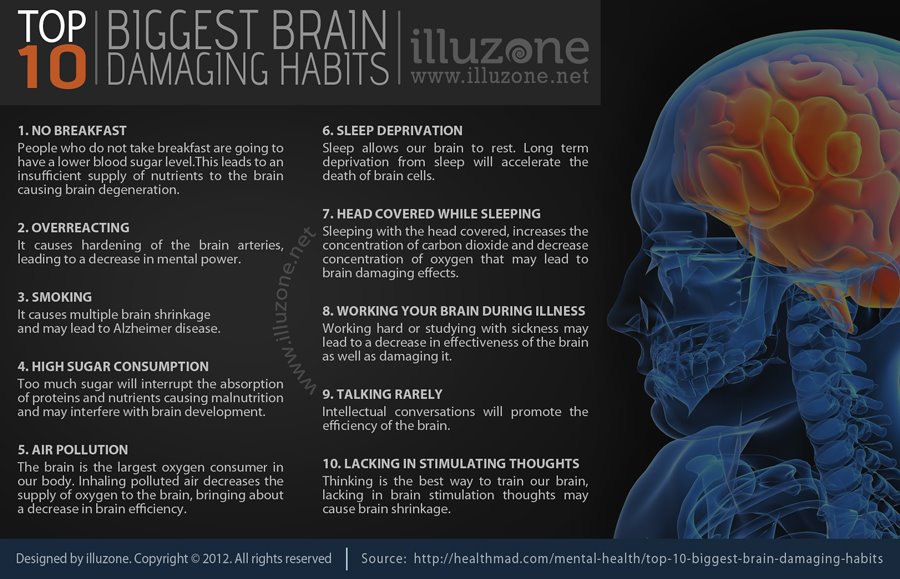

Consumption of highly refined carbohydrates can increase the risk of obesity and diabetes.5 Glycaemic index is a relative ranking of carbohydrate in foods according to the speed at which they are digested, absorbed, metabolised, and ultimately affect blood glucose and insulin levels. As well as the physical health risks, diets with a high glycaemic index and load (eg, diets containing high amounts of refined carbohydrates and sugars) may also have a detrimental effect on psychological wellbeing; data from longitudinal research show an association between progressively higher dietary glycaemic index and the incidence of depressive symptoms.6 Clinical studies have also shown potential causal effects of refined carbohydrates on mood; experimental exposure to diets with a high glycaemic load in controlled settings increases depressive symptoms in healthy volunteers, with a moderately large effect.7

As well as the physical health risks, diets with a high glycaemic index and load (eg, diets containing high amounts of refined carbohydrates and sugars) may also have a detrimental effect on psychological wellbeing; data from longitudinal research show an association between progressively higher dietary glycaemic index and the incidence of depressive symptoms.6 Clinical studies have also shown potential causal effects of refined carbohydrates on mood; experimental exposure to diets with a high glycaemic load in controlled settings increases depressive symptoms in healthy volunteers, with a moderately large effect.7

Although mood itself can affect our food choices, plausible mechanisms exist by which high consumption of processed carbohydrates could increase the risk of depression and anxiety—for example, through repeated and rapid increases and decreases in blood glucose. Measures of glycaemic index and glycaemic load can be used to estimate glycaemia and insulin demand in healthy individuals after eating. 8 Thus, high dietary glycaemic load, and the resultant compensatory responses, could lower plasma glucose to concentrations that trigger the secretion of autonomic counter-regulatory hormones such as cortisol, adrenaline, growth hormone, and glucagon.59 The potential effects of this response on mood have been examined in experimental human research of stepped reductions in plasma glucose concentrations conducted under laboratory conditions through glucose perfusion. These findings showed that such counter-regulatory hormones may cause changes in anxiety, irritability, and hunger.10 In addition, observational research has found that recurrent hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar) is associated with mood disorders.9

8 Thus, high dietary glycaemic load, and the resultant compensatory responses, could lower plasma glucose to concentrations that trigger the secretion of autonomic counter-regulatory hormones such as cortisol, adrenaline, growth hormone, and glucagon.59 The potential effects of this response on mood have been examined in experimental human research of stepped reductions in plasma glucose concentrations conducted under laboratory conditions through glucose perfusion. These findings showed that such counter-regulatory hormones may cause changes in anxiety, irritability, and hunger.10 In addition, observational research has found that recurrent hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar) is associated with mood disorders.9

The hypothesis that repeated and rapid increases and decreases in blood glucose explain how consumption of refined carbohydrate could affect psychological state appears to be a good fit given the relatively fast effect of diets with a high glycaemic index or load on depressive symptoms observed in human studies. 7 However, other processes may explain the observed relationships. For instance, diets with a high glycaemic index are a risk factor for diabetes,5 which is often a comorbid condition with depression.411 While the main models of disease pathophysiology in diabetes and mental illness are separate, common abnormalities in insulin resistance, brain volume, and neurocognitive performance in both conditions support the hypothesis that these conditions have overlapping pathophysiology.12 Furthermore, the inflammatory response to foods with a high glycaemic index13 raises the possibility that diets with a high glycaemic index are associated with symptoms of depression through the broader connections between mental health and immune activation.

7 However, other processes may explain the observed relationships. For instance, diets with a high glycaemic index are a risk factor for diabetes,5 which is often a comorbid condition with depression.411 While the main models of disease pathophysiology in diabetes and mental illness are separate, common abnormalities in insulin resistance, brain volume, and neurocognitive performance in both conditions support the hypothesis that these conditions have overlapping pathophysiology.12 Furthermore, the inflammatory response to foods with a high glycaemic index13 raises the possibility that diets with a high glycaemic index are associated with symptoms of depression through the broader connections between mental health and immune activation.

Studies have found that sustained adherence to Mediterranean dietary patterns can reduce markers of inflammation in humans.14 On the other hand, high calorie meals rich in saturated fat appear to stimulate immune activation. 1315 Indeed, the inflammatory effects of a diet high in calories and saturated fat have been proposed as one mechanism through which the Western diet may have detrimental effects on brain health, including cognitive decline, hippocampal dysfunction, and damage to the blood-brain barrier.15 Since various mental health conditions, including mood disorders, have been linked to heightened inflammation,16 this mechanism also presents a pathway through which poor diet could increase the risk of depression. This hypothesis is supported by observational studies which have shown that people with depression score significantly higher on measures of “dietary inflammation,”317 characterised by a greater consumption of foods that are associated with inflammation (eg, trans fats and refined carbohydrates) and lower intakes of nutritional foods, which are thought to have anti-inflammatory properties (eg, omega-3 fats). However, the causal roles of dietary inflammation in mental health have not yet been established.

1315 Indeed, the inflammatory effects of a diet high in calories and saturated fat have been proposed as one mechanism through which the Western diet may have detrimental effects on brain health, including cognitive decline, hippocampal dysfunction, and damage to the blood-brain barrier.15 Since various mental health conditions, including mood disorders, have been linked to heightened inflammation,16 this mechanism also presents a pathway through which poor diet could increase the risk of depression. This hypothesis is supported by observational studies which have shown that people with depression score significantly higher on measures of “dietary inflammation,”317 characterised by a greater consumption of foods that are associated with inflammation (eg, trans fats and refined carbohydrates) and lower intakes of nutritional foods, which are thought to have anti-inflammatory properties (eg, omega-3 fats). However, the causal roles of dietary inflammation in mental health have not yet been established.

Nonetheless, randomised controlled trials of anti-inflammatory agents (eg, cytokine inhibitors and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) have found that these agents can significantly reduce depressive symptoms.18 Specific nutritional components (eg, polyphenols and polyunsaturated fats) and general dietary patterns (eg, consumption of a Mediterranean diet) may also have anti-inflammatory effects,141920 which raises the possibility that certain foods could relieve or prevent depressive symptoms associated with heightened inflammatory status.21 A recent study provides preliminary support for this possibility.20 The study shows that medications that stimulate inflammation typically induce depressive states in people treated, and that giving omega-3 fatty acids, which have anti-inflammatory properties, before the medication seems to prevent the onset of cytokine induced depression.20

However, the complexity of the hypothesised three way relation between diet, inflammation, and depression is compounded by several important modifiers. For example, recent clinical research has observed that stressors experienced the previous day, or a personal history of major depressive disorders, may cancel out the beneficial effects of healthy food choices on inflammation and mood.22 Furthermore, as heightened inflammation occurs in only some clinically depressed individuals, anti-inflammatory interventions may only benefit certain people characterised by an “inflammatory phenotype,” or those with comorbid inflammatory conditions.18 Further interventional research is needed to establish if improvements in immune regulation, induced by diet, can reduce depressive symptoms in those affected by inflammatory conditions.

For example, recent clinical research has observed that stressors experienced the previous day, or a personal history of major depressive disorders, may cancel out the beneficial effects of healthy food choices on inflammation and mood.22 Furthermore, as heightened inflammation occurs in only some clinically depressed individuals, anti-inflammatory interventions may only benefit certain people characterised by an “inflammatory phenotype,” or those with comorbid inflammatory conditions.18 Further interventional research is needed to establish if improvements in immune regulation, induced by diet, can reduce depressive symptoms in those affected by inflammatory conditions.

A more recent explanation for the way in which our food may affect our mental wellbeing is the effect of dietary patterns on the gut microbiome—a broad term that refers to the trillions of microbial organisms, including bacteria, viruses, and archaea, living in the human gut. The gut microbiome interacts with the brain in bidirectional ways using neural, inflammatory, and hormonal signalling pathways. 23 The role of altered interactions between the brain and gut microbiome on mental health has been proposed on the basis of the following evidence: emotion-like behaviour in rodents changes with changes in the gut microbiome,24 major depressive disorder in humans is associated with alterations of the gut microbiome,25 and transfer of faecal gut microbiota from humans with depression into rodents appears to induce animal behaviours that are hypothesised to indicate depression-like states.2526 Such findings suggest a role of altered neuroactive microbial metabolites in depressive symptoms.

23 The role of altered interactions between the brain and gut microbiome on mental health has been proposed on the basis of the following evidence: emotion-like behaviour in rodents changes with changes in the gut microbiome,24 major depressive disorder in humans is associated with alterations of the gut microbiome,25 and transfer of faecal gut microbiota from humans with depression into rodents appears to induce animal behaviours that are hypothesised to indicate depression-like states.2526 Such findings suggest a role of altered neuroactive microbial metabolites in depressive symptoms.

In addition to genetic factors and exposure to antibiotics, diet is a potentially modifiable determinant of the diversity, relative abundance, and functionality of the gut microbiome throughout life. For instance, the neurocognitive effects of the Western diet, and the possible mediating role of low grade systemic immune activation (as discussed above) may result from a compromised mucus layer with or without increased epithelial permeability. Such a decrease in the function of the gut barrier is sometimes referred to as a “leaky gut” and has been linked to an “unhealthy” gut microbiome resulting from a diet low in fibre and high in saturated fats, refined sugars, and artificial sweeteners.152327 Conversely, the consumption of a diet high in fibres, polyphenols, and unsaturated fatty acids (as found in a Mediterranean diet) can promote gut microbial taxa which can metabolise these food sources into anti-inflammatory metabolites,1528 such as short chain fatty acids, while lowering the production of secondary bile acids and p-cresol. Moreover, a recent study found that the ingestion of probiotics by healthy individuals, which theoretically target the gut microbiome, can alter the brain’s response to a task that requires emotional attention29 and may even reduce symptoms of depression.30 When viewed together, these studies provide promising evidence supporting a role of the gut microbiome in modulating processes that regulate emotion in the human brain.

Such a decrease in the function of the gut barrier is sometimes referred to as a “leaky gut” and has been linked to an “unhealthy” gut microbiome resulting from a diet low in fibre and high in saturated fats, refined sugars, and artificial sweeteners.152327 Conversely, the consumption of a diet high in fibres, polyphenols, and unsaturated fatty acids (as found in a Mediterranean diet) can promote gut microbial taxa which can metabolise these food sources into anti-inflammatory metabolites,1528 such as short chain fatty acids, while lowering the production of secondary bile acids and p-cresol. Moreover, a recent study found that the ingestion of probiotics by healthy individuals, which theoretically target the gut microbiome, can alter the brain’s response to a task that requires emotional attention29 and may even reduce symptoms of depression.30 When viewed together, these studies provide promising evidence supporting a role of the gut microbiome in modulating processes that regulate emotion in the human brain. However, no causal relationship between specific microbes, or their metabolites, and complex human emotions has been established so far. Furthermore, whether changes to the gut microbiome induced by diet can affect depressive symptoms or clinical depressive disorders, and the time in which this could feasibly occur, remains to be shown.

However, no causal relationship between specific microbes, or their metabolites, and complex human emotions has been established so far. Furthermore, whether changes to the gut microbiome induced by diet can affect depressive symptoms or clinical depressive disorders, and the time in which this could feasibly occur, remains to be shown.

In moving forward within this active field of research, it is firstly important not to lose sight of the wood for the trees—that is, become too focused on the details and not pay attention to the bigger questions. Whereas discovering the anti-inflammatory properties of a single nutrient or uncovering the subtleties of interactions between the gut and the brain may shed new light on how food may influence mood, it is important not to neglect the existing knowledge on other ways diet may affect mental health. For example, the later consequences of a poor diet include obesity and diabetes, which have already been shown to be associated with poorer mental health. 11313233 A full discussion of the effect of these comorbidities is beyond the scope of our article (see ), but it is important to acknowledge that developing public health initiatives that effectively tackle the established risk factors of physical and mental comorbidities is a priority for improving population health.

11313233 A full discussion of the effect of these comorbidities is beyond the scope of our article (see ), but it is important to acknowledge that developing public health initiatives that effectively tackle the established risk factors of physical and mental comorbidities is a priority for improving population health.

Further work is needed to improve our understanding of the complex pathways through which diet and nutrition can influence the brain. Such knowledge could lead to investigations of targeted, even personalised, interventions to improve mood, anxiety, or other symptoms through nutritional approaches. However, these possibilities are speculative at the moment, and more interventional research is needed to establish if, how, and when dietary interventions can be used to prevent mental illness or reduce symptoms in those living with such conditions. Of note, a recent large clinical trial found no significant benefits of a behavioural intervention promoting a Mediterranean diet for adults with subclinical depressive symptoms. 34 On the other hand, several recent smaller trials in individuals with current depression observed moderately large improvements from interventions based on the Mediterranean diet.353637 Such results, however, must be considered within the context of the effect of people’s expectations, particularly given that individuals’ beliefs about the quality of their food or diet may also have a marked effect on their sense of overall health and wellbeing.38 Nonetheless, even aside from psychological effects, consideration of dietary factors within mental healthcare may help improve physical health outcomes, given the higher rates of cardiometabolic diseases observed in people with mental illness.33

34 On the other hand, several recent smaller trials in individuals with current depression observed moderately large improvements from interventions based on the Mediterranean diet.353637 Such results, however, must be considered within the context of the effect of people’s expectations, particularly given that individuals’ beliefs about the quality of their food or diet may also have a marked effect on their sense of overall health and wellbeing.38 Nonetheless, even aside from psychological effects, consideration of dietary factors within mental healthcare may help improve physical health outcomes, given the higher rates of cardiometabolic diseases observed in people with mental illness.33

At the same time, it is important to be remember that the causes of mental illness are many and varied, and they will often present and persist independently of nutrition and diet. Thus, the increased understanding of potential connections between food and mental wellbeing should never be used to support automatic assumptions, or stigmatisation, about an individual’s dietary choices and their mental health. Indeed, such stigmatisation could be itself be a casual pathway to increasing the risk of poorer mental health. Nonetheless, a promising message for public health and clinical settings is emerging from the ongoing research. This message supports the idea that creating environments and developing measures that promote healthy, nutritious diets, while decreasing the consumption of highly processed and refined “junk” foods may provide benefits even beyond the well known effects on physical health, including improved psychological wellbeing.

Indeed, such stigmatisation could be itself be a casual pathway to increasing the risk of poorer mental health. Nonetheless, a promising message for public health and clinical settings is emerging from the ongoing research. This message supports the idea that creating environments and developing measures that promote healthy, nutritious diets, while decreasing the consumption of highly processed and refined “junk” foods may provide benefits even beyond the well known effects on physical health, including improved psychological wellbeing.

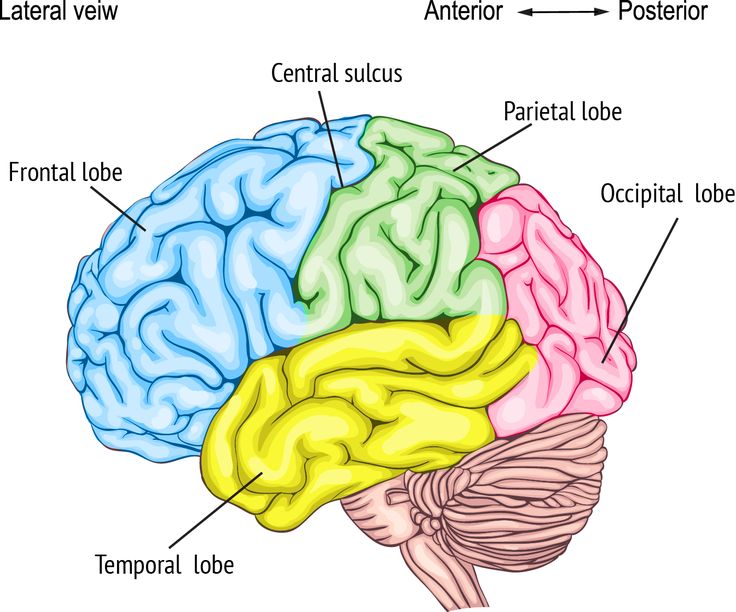

Contributors and sources: JF has expertise in the interaction between physical and mental health, particularly the role of lifestyle and behavioural health factors in mental health promotion. JEG’s area of expertise is the study of the relationship between sleep duration, nutrition, psychiatric disorders, and cardiometabolic diseases. AB leads research investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying the effect of stress and inflammation on human hippocampal neurogenesis, and how nutritional components and their metabolites can prevent changes induced by those conditions. REW has expertise in genetic epidemiology approaches to examining casual relations between health behaviours and mental illness. EAM has expertise in brain and gut interactions and microbiome interactions. All authors contributed to, read, and approved the paper, and all the information was sourced from articles published in peer reviewed research journals. JF is the guarantor.

REW has expertise in genetic epidemiology approaches to examining casual relations between health behaviours and mental illness. EAM has expertise in brain and gut interactions and microbiome interactions. All authors contributed to, read, and approved the paper, and all the information was sourced from articles published in peer reviewed research journals. JF is the guarantor.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following: JF is supported by a University of Manchester Presidential Fellowship and a UK Research and Innovation Future Leaders Fellowship and has received support from a NICM-Blackmores Institute Fellowship. JEG served on the medical advisory board on insomnia in the cardiovascular patient population for the drug company Eisai. AB has received research funding from Johnson & Johnson for research on depression and inflammation, the UK Medical Research Council, the European Commission Horizon 2020, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, and King’s College London. REW receives funding from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol. EAM has served on the external advisory boards of Danone, Viome, Amare, Axial Biotherapeutics, Pendulum, Ubiome, Bloom Science, Mahana Therapeutics, and APC Microbiome Ireland, and he receives royalties from Harper & Collins for his book The Mind Gut Connection. He is supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the US Department of Defense. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the organisations above.

REW receives funding from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol. EAM has served on the external advisory boards of Danone, Viome, Amare, Axial Biotherapeutics, Pendulum, Ubiome, Bloom Science, Mahana Therapeutics, and APC Microbiome Ireland, and he receives royalties from Harper & Collins for his book The Mind Gut Connection. He is supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the US Department of Defense. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the organisations above.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is part of series commissioned by The BMJ. Open access fees are paid by Swiss Re, which had no input into the commissioning or peer review of the articles. The BMJ thanks the series advisers, Nita Forouhi, Dariush Mozaffarian, and Anna Lartey for valuable advice and guiding selection of topics in the series.

1. Friedrich MJ. Depression is the leading cause of disability around the world. JAMA 2017;317:1517. 10.1001/jama.2017.3826 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. Johnson J, Weissman MM, Klerman GL. Service utilization and social morbidity associated with depressive symptoms in the community. JAMA 1992;267:1478-83. 10.1001/jama.1992.03480110054033 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Lassale C, Batty GD, Baghdadli A, et al. Healthy dietary indices and risk of depressive outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Mol Psychiatry 2019;24:965-86. 10.1038/s41380-018-0237-8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Firth J, Siddiqi N, Koyanagi A, et al. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: a blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry 2019;6:675-712. 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30132-4 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Ludwig DS. The glycemic index: physiological mechanisms relating to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. JAMA 2002;287:2414-23. 10.1001/jama.287.18.2414 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

JAMA 2002;287:2414-23. 10.1001/jama.287.18.2414 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Gangwisch JE, Hale L, Garcia L, et al. High glycemic index diet as a risk factor for depression: analyses from the Women’s Health Initiative. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;102:454-63. 10.3945/ajcn.114.103846 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Salari-Moghaddam A, Saneei P, Larijani B, Esmaillzadeh A. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr 2019;73:356-65. 10.1038/s41430-018-0258-z [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Bao J, de Jong V, Atkinson F, Petocz P, Brand-Miller JC. Food insulin index: physiologic basis for predicting insulin demand evoked by composite meals. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;90:986-92. 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27720 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Seaquist ER, Anderson J, Childs B, et al.American Diabetes Association. Endocrine Society Hypoglycemia and diabetes: a report of a workgroup of the American Diabetes Association and the Endocrine Society. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:1845-59. 10.1210/jc.2012-4127 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:1845-59. 10.1210/jc.2012-4127 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Towler DA, Havlin CE, Craft S, Cryer P. Mechanism of awareness of hypoglycemia. Perception of neurogenic (predominantly cholinergic) rather than neuroglycopenic symptoms. Diabetes 1993;42:1791-8. 10.2337/diab.42.12.1791 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Salvi V, Hajek T. Brain-metabolic crossroads in severe mental disorders. Front Psychiatry 2019;10:492. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00492 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. McIntyre RS, Kenna HA, Nguyen HT, et al. Brain volume abnormalities and neurocognitive deficits in diabetes mellitus: points of pathophysiological commonality with mood disorders? Adv Ther 2010;27:63-80. 10.1007/s12325-010-0011-z [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. O’Keefe JH, Gheewala NM, O’Keefe JO. Dietary strategies for improving post-prandial glucose, lipids, inflammation, and cardiovascular health. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:249-55. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.016 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:249-55. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.016 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Kastorini C-M, Milionis HJ, Esposito K, Giugliano D, Goudevenos JA, Panagiotakos DB. The effect of Mediterranean diet on metabolic syndrome and its components: a meta-analysis of 50 studies and 534 906 individuals. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:1299-313. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.073 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Noble EE, Hsu TM, Kanoski SE. Gut to brain dysbiosis: mechanisms linking western diet consumption, the microbiome, and cognitive impairment. Front Behav Neurosci 2017;11:9. 10.3389/fnbeh.2017.00009 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Yuan N, Chen Y, Xia Y, Dai J, Liu C. Inflammation-related biomarkers in major psychiatric disorders: a cross-disorder assessment of reproducibility and specificity in 43 meta-analyses. Transl Psychiatry 2019;9:233. 10.1038/s41398-019-0570-y [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Firth J, Stubbs B, Teasdale SB, et al. Diet as a hot topic in psychiatry: a population-scale study of nutritional intake and inflammatory potential in severe mental illness. World Psychiatry 2018;17:365-7. 10.1002/wps.20571 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Firth J, Stubbs B, Teasdale SB, et al. Diet as a hot topic in psychiatry: a population-scale study of nutritional intake and inflammatory potential in severe mental illness. World Psychiatry 2018;17:365-7. 10.1002/wps.20571 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Köhler-Forsberg O, N Lydholm C, Hjorthøj C, Nordentoft M, Mors O, Benros ME. Efficacy of anti-inflammatory treatment on major depressive disorder or depressive symptoms: meta-analysis of clinical trials. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2019;139:404-19. 10.1111/acps.13016 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Yahfoufi N, Alsadi N, Jambi M, Matar C. The immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory role of polyphenols. Nutrients 2018;10:E1618. 10.3390/nu10111618 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Su K-P, Lai H-C, Yang H-T, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids in the prevention of interferon-alpha-induced depression: results from a randomized, controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry 2014;76:559-66. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.01.008 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.01.008 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Borsini A, Alboni S, Horowitz MA, et al. Rescue of IL-1β-induced reduction of human neurogenesis by omega-3 fatty acids and antidepressants. Brain Behav Immun 2017;65:230-8. 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.05.006 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Fagundes CP, Andridge R, et al. Depression, daily stressors and inflammatory responses to high-fat meals: when stress overrides healthier food choices. Mol Psychiatry 2017;22:476-82. 10.1038/mp.2016.149 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. Osadchiy V, Martin CR, Mayer EA. Gut microbiome and modulation of CNS function. Compr Physiol 2019;10:57-72. 10.1002/cphy.c180031 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

24. Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci 2012;13:701-12. 10.1038/nrn3346 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Kelly JR, Borre Y, O’Brien C, et al. Transferring the blues: depression-associated gut microbiota induces neurobehavioural changes in the rat. J Psychiatr Res 2016;82:109-18. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.07.019 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Kelly JR, Borre Y, O’Brien C, et al. Transferring the blues: depression-associated gut microbiota induces neurobehavioural changes in the rat. J Psychiatr Res 2016;82:109-18. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.07.019 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Kelly JR, Keane VO, Cryan JF, Clarke G, Dinan TG. Mood and microbes: gut to brain communication in depression. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2019;48:389-405. 10.1016/j.gtc.2019.04.006 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

27. Sonnenburg ED, Sonnenburg JL. The ancestral and industrialized gut microbiota and implications for human health. Nat Rev Microbiol 2019;17:383-90. 10.1038/s41579-019-0191-8 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

28. Ghosh TS, Rampelli S, Jeffery IB, et al. Mediterranean diet intervention alters the gut microbiome in older people reducing frailty and improving health status: the NU-AGE 1-year dietary intervention across five European countries. Gut 2020;69:1218-28. 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319654 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Tillisch K, Labus J, Kilpatrick L, et al. Consumption of fermented milk product with probiotic modulates brain activity. Gastroenterology 2013;144:1394-401, 1401.e1-4. 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.043. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Tillisch K, Labus J, Kilpatrick L, et al. Consumption of fermented milk product with probiotic modulates brain activity. Gastroenterology 2013;144:1394-401, 1401.e1-4. 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.043. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

30. Liu RT, Walsh RFL, Sheehan AE. Prebiotics and probiotics for depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2019;102:13-23. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.03.023 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

31. Wootton RE, Lawn RB, Millard LAC, et al. Evaluation of the causal effects between subjective wellbeing and cardiometabolic health: Mendelian randomisation study. BMJ 2018;362:k3788. 10.1136/bmj.k3788 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

32. Jebeile H, Gow ML, Baur LA, Garnett SP, Paxton SJ, Lister NB. Association of pediatric obesity treatment, including a dietary component, with change in depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2019;173:e192841. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.2841 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

JAMA Pediatr 2019;173:e192841. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.2841 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

33. Ma J, Rosas LG, Lv N, et al. Effect of integrated behavioral weight loss treatment and problem-solving therapy on body mass index and depressive symptoms among patients with obesity and depression: the RAINBOW randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019;321:869-79. 10.1001/jama.2019.0557 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

34. Bot M, Brouwer IA, Roca M, et al.MooDFOOD Prevention Trial Investigators Effect of multinutrient supplementation and food-related behavioral activation therapy on prevention of major depressive disorder among overweight or obese adults with subsyndromal depressive symptoms: the MooDFOOD randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019;321:858-68. 10.1001/jama.2019.0556 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

35. Francis HM, Stevenson RJ, Chambers JR, Gupta D, Newey B, Lim CK. A brief diet intervention can reduce symptoms of depression in young adults – a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One 2019;14:e0222768. 10.1371/journal.pone.0222768 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

PLoS One 2019;14:e0222768. 10.1371/journal.pone.0222768 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

36. Jacka FN, O’Neil A, Opie R, et al. A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’ trial). BMC Med 2017;15:23. 10.1186/s12916-017-0791-y. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

37. Parletta N, Zarnowiecki D, Cho J, et al. A Mediterranean-style dietary intervention supplemented with fish oil improves diet quality and mental health in people with depression: A randomized controlled trial (HELFIMED). Nutr Neurosci 2019;22:474-87. 10.1080/1028415X.2017.1411320. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

38. Rozin P, Fischler C, Imada S, Sarubin A, Wrzesniewski A. Attitudes to food and the role of food in life in the USA, Japan, Flemish Belgium and France: possible implications for the diet-health debate. Appetite 1999;33:163-80. 10.1006/appe.1999.0244 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

39. Hunt A, Harrington D, Robinson S. Vitamin B12 deficiency. BMJ 2014;349:g5226. 10.1136/bmj.g5226 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Hunt A, Harrington D, Robinson S. Vitamin B12 deficiency. BMJ 2014;349:g5226. 10.1136/bmj.g5226 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

How are nutrition and mental health related?

07/27/2020

Our gut health is affected by what we eat. A new field of research called nutritional psychiatry is showing a strong link between nutrition and mental health.

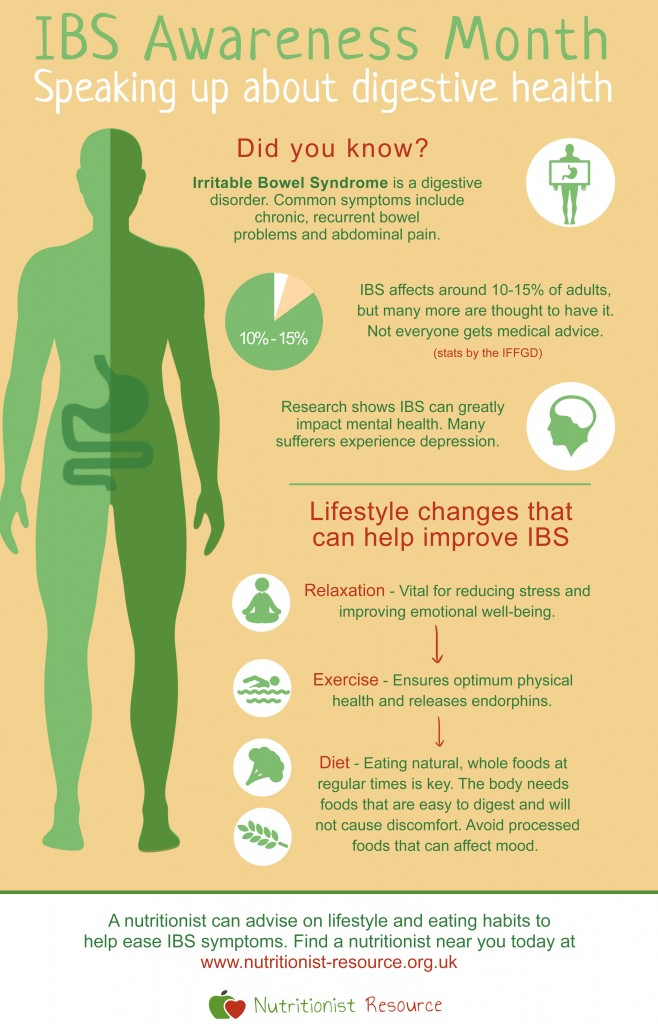

Research indicates that improper bowel function not only leads to poor mental health, but also increases the risk of other diseases. In turn, when you consume the right food, it releases the "happiness hormone" known as serotonin. Appropriate levels of this neurotransmitter keep your mood upbeat, sleep well, and overall health on track.

What is the relationship between nutrition and mental health?

Serotonin is a hormone that affects everything from emotions to motor skills. This substance regulates mood, sleep and hunger. It is also considered a natural mood stabilizer.

About 95% of the serotonin produced by the body is located inside the intestines. The amount of serotonin and other neurotransmitters produced depends on the state of your intestinal microflora. When the intestines do not receive adequate healthy food, they lose most of the bacteria they need. This, in turn, reduces serotonin levels and can lead to chronic diseases such as:

- Asthma

- Obesity

- Diabetes mellitus

- Metabolic syndrome

- Inflammatory bowel disease

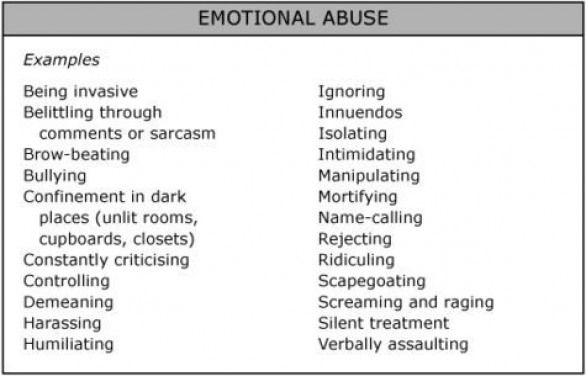

Serotonin deficiency is also associated with psychological problems such as:

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Aggression

- Insomnia

- Irritability

- Bad memory

- Low self-esteem

- Impulsive behavior

The gut microflora requires a delicate balance of bacteria, viruses and fungi. Beneficial bacteria create a strong barrier against toxins and "pathogenic" bacteria. They also prevent inflammation, aid in the absorption of nutrients, and activate the nerve pathways that link the gut and brain.

They also prevent inflammation, aid in the absorption of nutrients, and activate the nerve pathways that link the gut and brain.

Nutritional psychiatry has attracted researchers studying nutritional approaches for the prevention and treatment of psychiatric disorders.

You are what you eat: nutrition against mental disorders

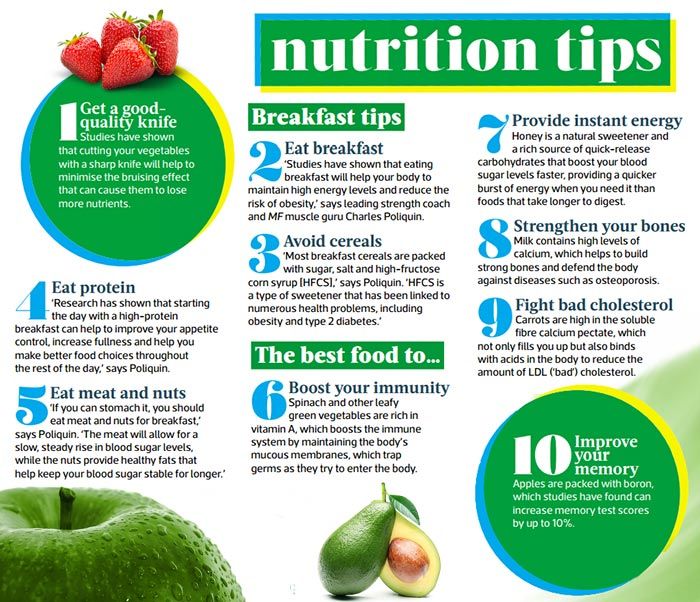

The foods you eat throughout your life affect how diverse your microflora is. A healthy diet low in processed foods and refined sugars is not only good for physical health, but also for mental health. Many studies show that depression is linked to inflammatory bowel disease, which explains why traditional antidepressants don't always work.

A 2018 study published in the World Journal of Psychiatry describes antidepressant products that prevent depression. Key foods containing these nutrients are oysters, mussels, salmon, watercress, spinach, romaine lettuce, cauliflower, and strawberries. This Mediterranean diet helps reduce the risk of depression by 25-35% compared to diets full of processed foods and sugar.

A few other important points:

● Choose foods rich in probiotics: plain yogurt with no added sugar, unsweetened kefir, sauerkraut, or kimchi help maintain gut health.

● Drink more water - keeping your intestines working properly will keep you feeling alert and fresh. Sweetened water and sports drinks do not count.

● Focus on overall well-being: Insufficient sleep and excessive stress can also affect your gut health. Too much stress can lead to sleep disturbance. Try to sleep 7-8 hours a day.

● While a healthy diet can help your mood and overall health, don't hesitate to seek professional counseling if you feel the need.

About Food Compass, the impact of nutrition on mental health and the unobvious benefits of pets - Sektascience: a popular science magazine

Food Compass - a new way to assess the health benefits or harms of foods scientists from the USA. It helps to evaluate the health impact of more than 8,000 foods, drinks and dishes (hereinafter referred to as foods).

All products are ranked on a scale from 1 to 100 based on extensive and up-to-date scientific data on their properties.

How the evaluation works

Products are evaluated on nine characteristics: for example, the ratio of nutrients, the presence of vitamins, trace elements, additives, the composition of fats and other components, the degree of processing.

The scores for each area are summed up. The final score of the product is formed in the range from 1 - the least healthy to 100 - the most healthy.

Authors rated foods on nine characteristicsRatings:

70-100 foods for main diet;

69-31 - products for moderate consumption;

30-1 - products that need to be minimized.

Why this system is needed

This system is needed to help consumers, food companies and food service businesses select and produce healthier food. And also to officials - to develop a reasonable state policy in the field of nutrition.

How Food Compass differs from other classifications

Compared to other classifications, Food Compass contains more information about the amount of nutrients and ingredients, uses consistent criteria in the classification, and takes into account the latest scientific achievements.

Foods are ranked from healthiest to least healthyComment #SEKTA: We found the new approach to classification interesting. It is important to bear in mind that the composition of some of the studied products is specific to the United States. However, Food Compass once again confirmed that the basic approaches to healthy eating remain the same: preference for vegetables and fruits, whole grains, fish and unprocessed meat, a minimum of added sugar, trans fats and processed foods.

SourceFood Compass. Publication on the Tufts University website (English)

Children who eat plenty of fruits and vegetables and don't skip breakfast and lunch have better mental health.

It turned out that children who eat five or more servings of vegetables and fruits a day are mentally healthier than those who eat less.

It turned out that children who eat five or more servings of vegetables and fruits a day are mentally healthier than those who eat less. Breakfast and lunch also matter. A traditional breakfast: an egg, toast, porridge, cereal, yogurt, fruit has a more positive effect on mental health than its absence or replacement with an energy drink.

Those who ate lunch also had a better mental state than those who skipped lunch.

#SEKTA comment: we now know that 5 or more servings of vegetables and fruits a day, as well as breakfast and lunch, are good not only for physical but also for mental health.

SourceAssociating schoolchildren's fruit and vegetable consumption and food choices with their mental well-being: a cross-sectional study. Article in BMJ

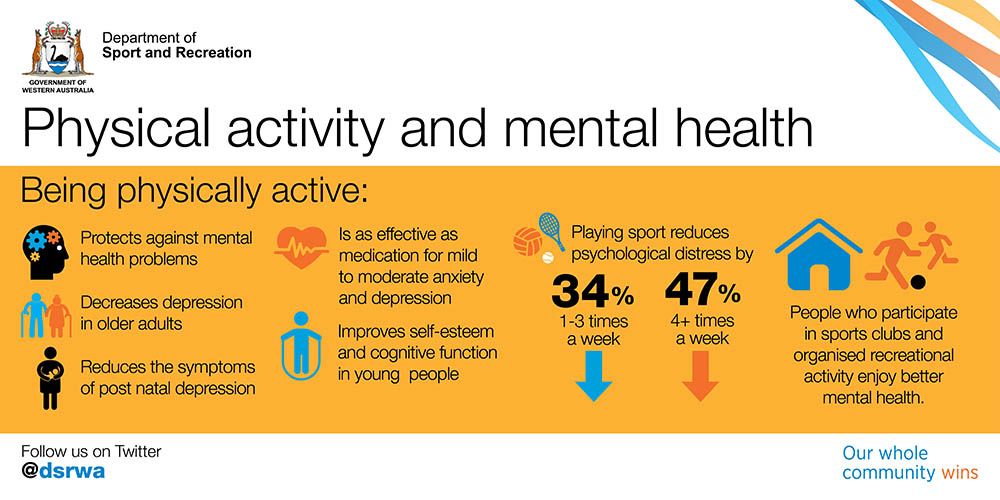

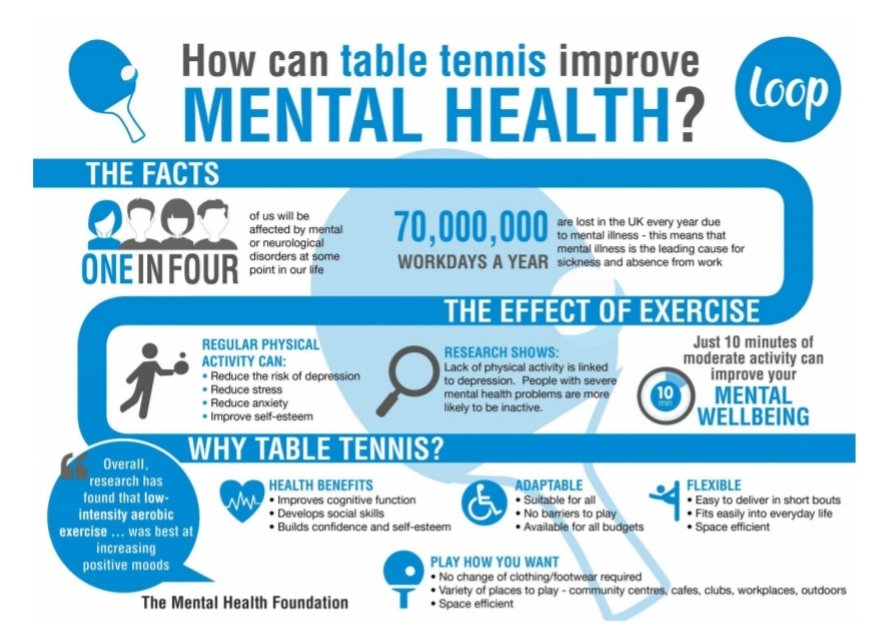

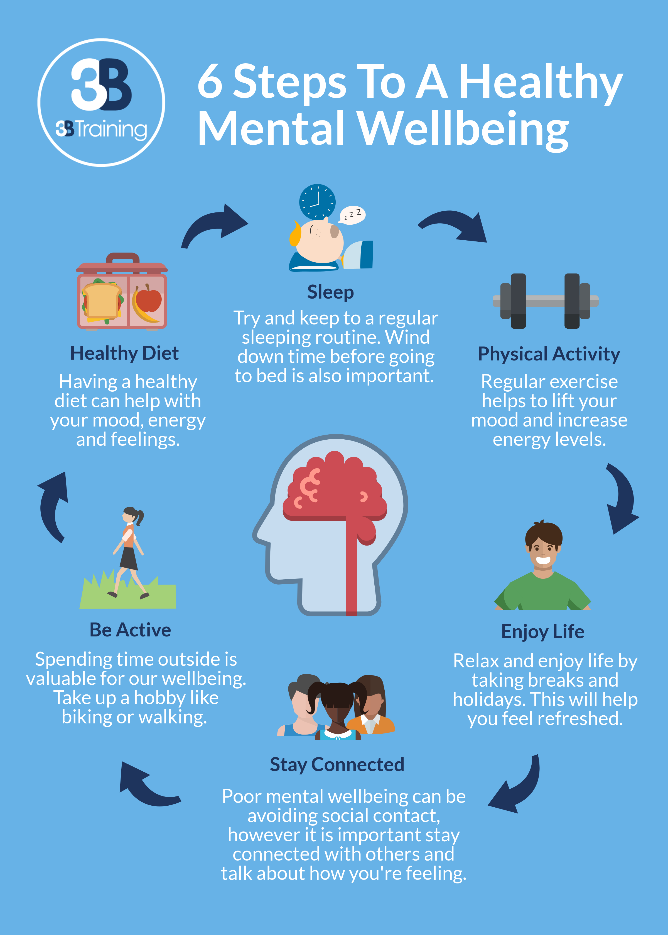

Outdoor activities improve mood and reduce anxiety

Outdoor activities have a positive effect on mood and reduce anxiety. Maximum results are achieved with classes from 20 to 90 minutes for 8-12 weeks or more.

This conclusion was made by the researchers as a result of a systematic review and meta-analysis of more than 14 thousand records and 50 studies of adults, including those with mental health problems.

Activities in nature here include gardening and horticulture, garbage collection in the forest, walking, jogging, arts in nature, therapeutic visits to the forest.

Comment #SEKTA: If you rarely go out into nature, you can start by simply taking regular walks in the nearest park. The main thing is to dress for the weather.

Ret.Outdoor activities for mental and physical health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Article in SSM-Population Health (English)

Fruits, vegetables and physical activity increase life satisfaction

Researchers compared the diet of 14,000 participants and their sports activity with measures of life satisfaction and came to the conclusion that those who ate more vegetables and fruits and exercised more generally felt happier with life than those who exercised less and ate fewer fruits and vegetables.

The authors attribute this to the ability to see the long-term benefits of these lifestyle factors.

Vegetables, fruits, and physical activity are often perceived by people as an investment in a healthier future, rather than as an immediate gratification. Therefore, only these two indicators of lifestyle were considered in the work.

Satisfaction with life was measured on a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 is not at all satisfied, 7 is completely satisfied.

The results of the study are valid for people of different sexes, ages, education, living in rural and urban areas.

Comment #SEKTA: we think that if you add outdoor activities to vegetables, fruits and physical activity, life satisfaction will only increase 😉

SourceLifestyle and life satisfaction: the role of delayed gratification. Article in the Journal of Happiness Studies

Regular adequate physical activity contributes to a milder course of COVID-19

“Adherence to recommendations for regular physical activity was strongly associated with a reduction in the risk of severe COVID-19 outcomesamong infected adults,” says a US study with data from more than 48,000 people.

Findings show that coronavirus patients who were inactive in the two years leading up to the spring 2020 lockdown were more likely to require hospitalization, require intensive care, and die than those who consistently adhered to recommendations for physical activity.

#SEKTA comment: By the way, maintaining the recommended level of physical activity can not only protect against the severe course of COVID-19but also reduce the risks of hundreds of other diseases. If you've been waiting for a sign to start moving more, here it is.

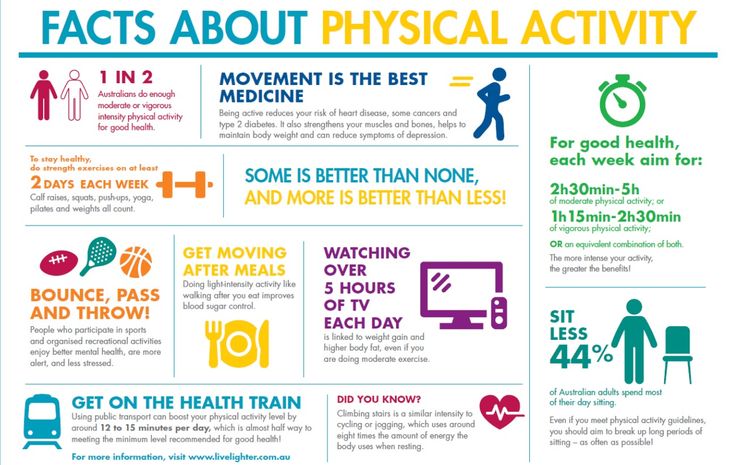

As a reminder, WHO recommends at least 150-300 minutes per week of moderate-intensity activity or at least 75-150 minutes of vigorous intensity.

SourcePhysical inactivity is associated with a higher risk of adverse COVID-19 outcomes: a study of 48,440 adults. Article in BMJ

Pets are good for the host gut microbiota

Recent studies show that having a dog at home improves the diversity of the healthy gut microbiota, which is closely linked to the immune system and many other body systems.