My brain is itchy

Definition, diagnosis, treatment, and outlook

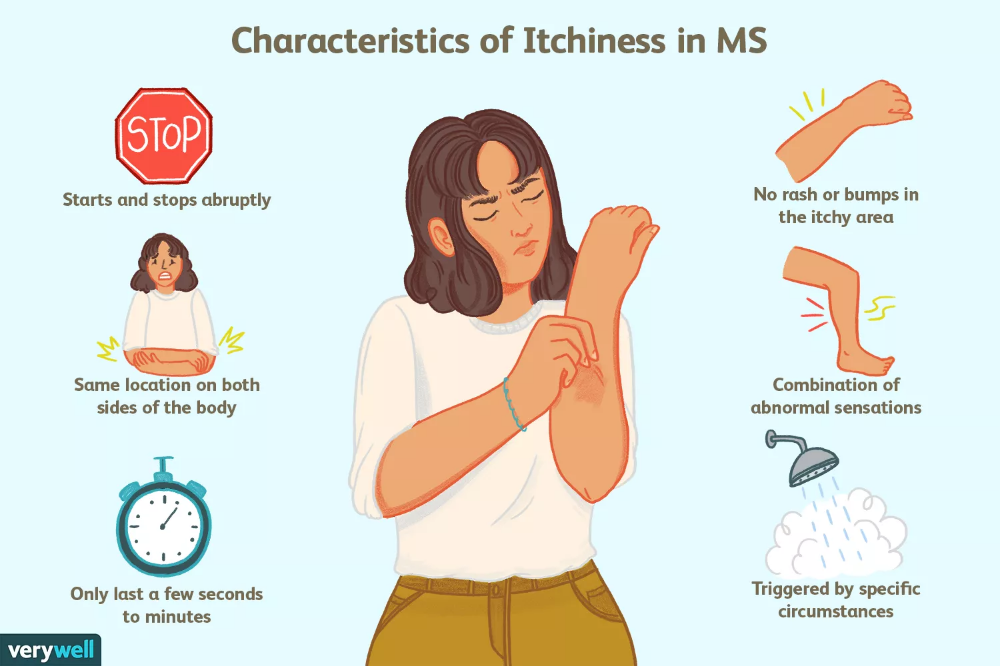

A neuropathic itch is an itch that results from nervous system damage rather than issues with the skin.

Itching is a normal sensation to experience from time to time. However, when an itch results from nervous system damage, doctors call it a neuropathic itch.

A neuropathic itch can feel different than a normal itching sensation. It can occur for various reasons, including stroke. Scratching may not provide relief from this type of itch.

Below, we look at the symptoms, causes, and treatment of neuropathic itch. We also discuss the outlook for people with this condition.

A neuropathic itch happens when there is damage to the nervous system.

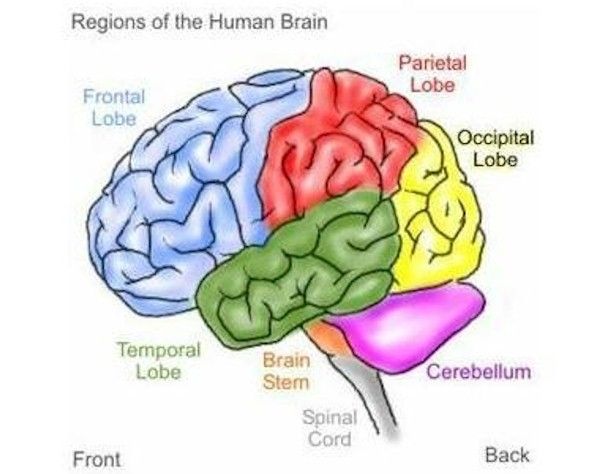

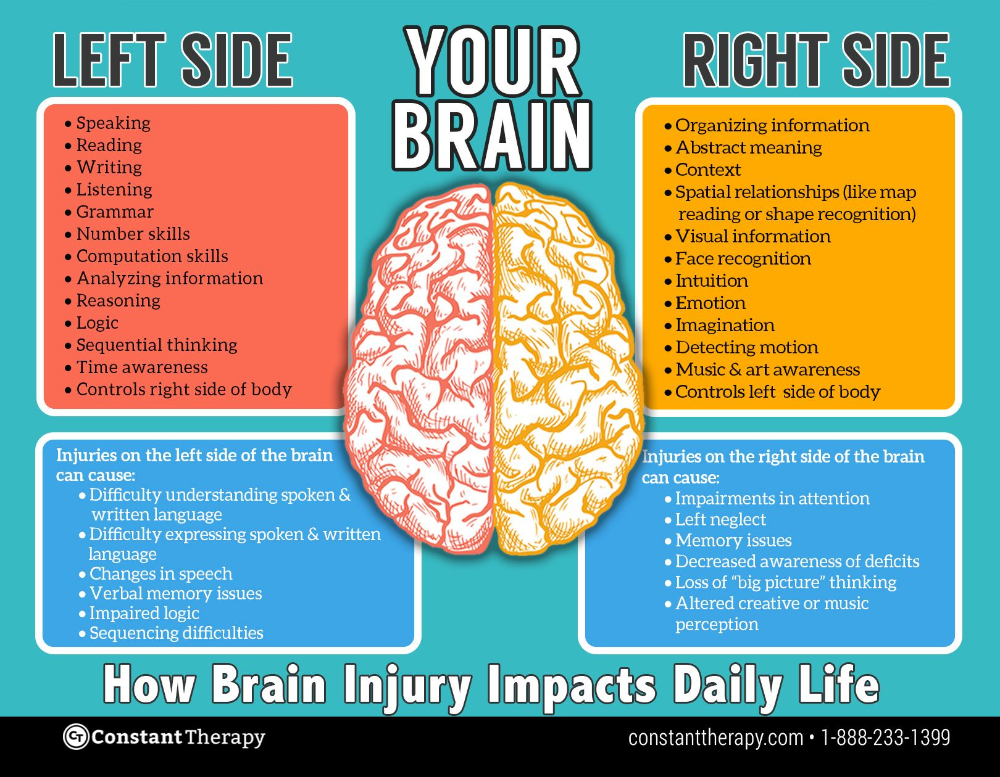

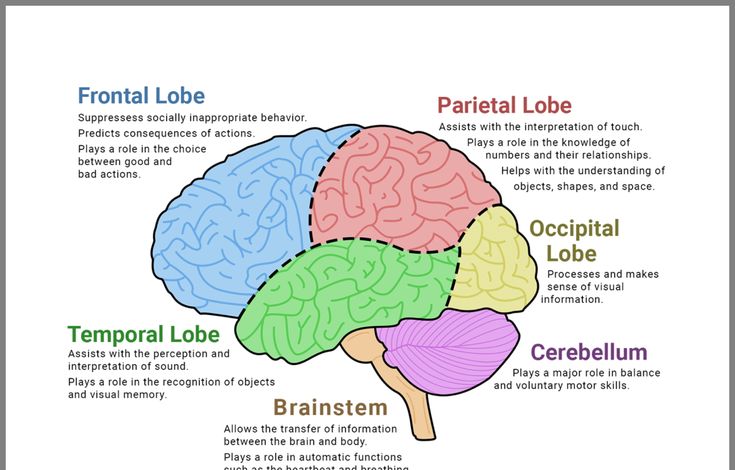

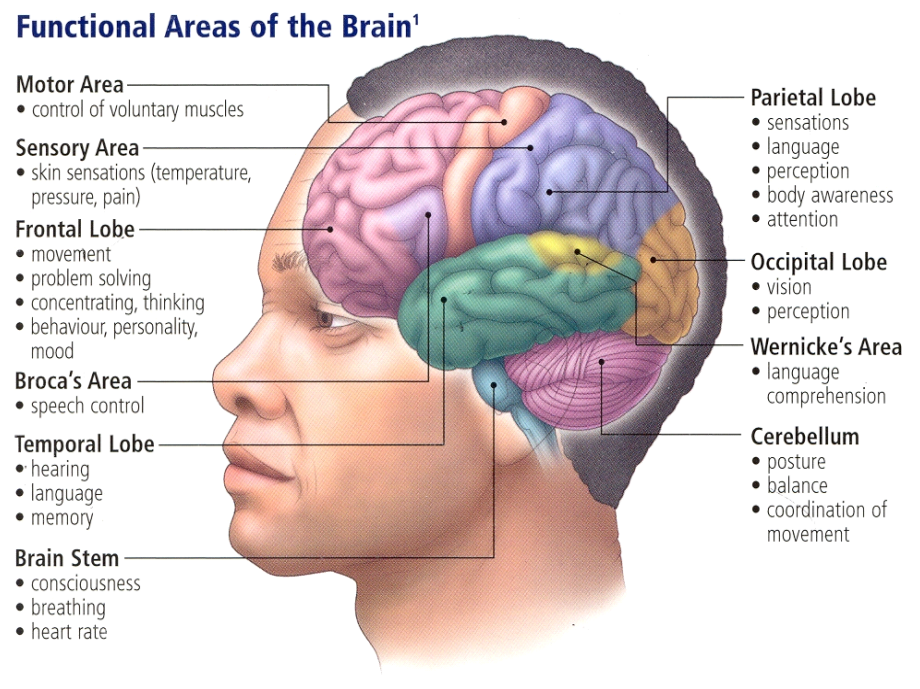

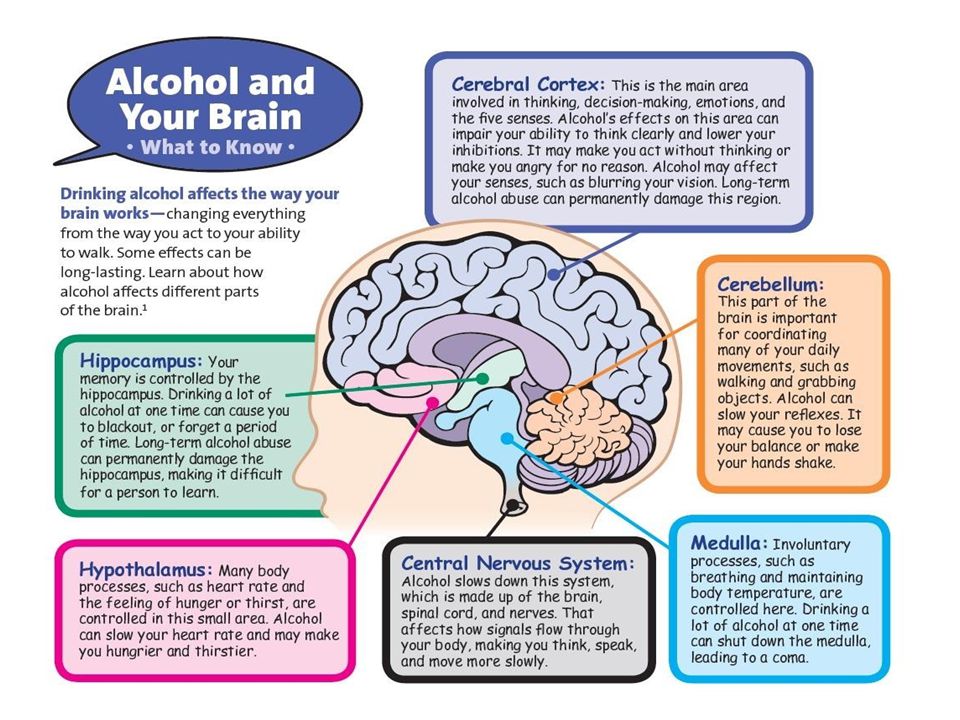

Damage to either the central or peripheral nervous system can cause a neuropathic itch, according to an older article from 2010.

While a regular itch results from some kind of issue with the skin, a neuropathic itch has a different, deeper origin.

A neuropathic itch may produce an itching sensation or a feeling of pins and needles. The itching may be very severe.

Neuropathic itch may also produce the following sensations:

- burning

- wetness

- electric shocks

- pain

- numbness

- crawling

- severe cold

Some people with neuropathic itch may also experience other symptoms such as:

- prickling and chilling of the skin

- increase in skin sensitivity

- decrease in skin sensitivity

In people with neuropathic itch, scratching can also make the itch worse.

There is very little understanding of the bodily mechanisms that create itching sensations.

Research suggests that lesions in the nervous system that damage itch-related neurons may cause neuropathic itch. Conditions and diseases that may cause neuropathic itch include:

- notalgia paresthetica, which is nerve pain that may involve itching of the back

- brachioradial pruritus, a nerve disorder that affects the arms

- peripheral neuropathy, the term for damage to the peripheral nerves that often produces symptoms in the hands and feet

- nerve irritation

- shingles

- stroke

- diabetes

- vitamin deficiencies

- toxin exposure

- trigeminal trophic syndrome, a rare condition that happens because of trigeminal nerve damage

- burns or keloids

- spinal tumor

- brain tumor

- multiple sclerosis

Doctors may have difficulty diagnosing neuropathic itch, as they may initially assume that the problem is skin-related.

However, a dermatologist can rule out any dermatological causes of itching.

Doctors usually prescribe topical treatments to people who present with itching. They may suspect neuropathic itch when these treatments do not work.

However, it can be tough to find the exact cause. If traditional anti-itch therapies do not work, people should consult a neurologist.

Doctors may perform a skin biopsy to check for neuropathic itch.

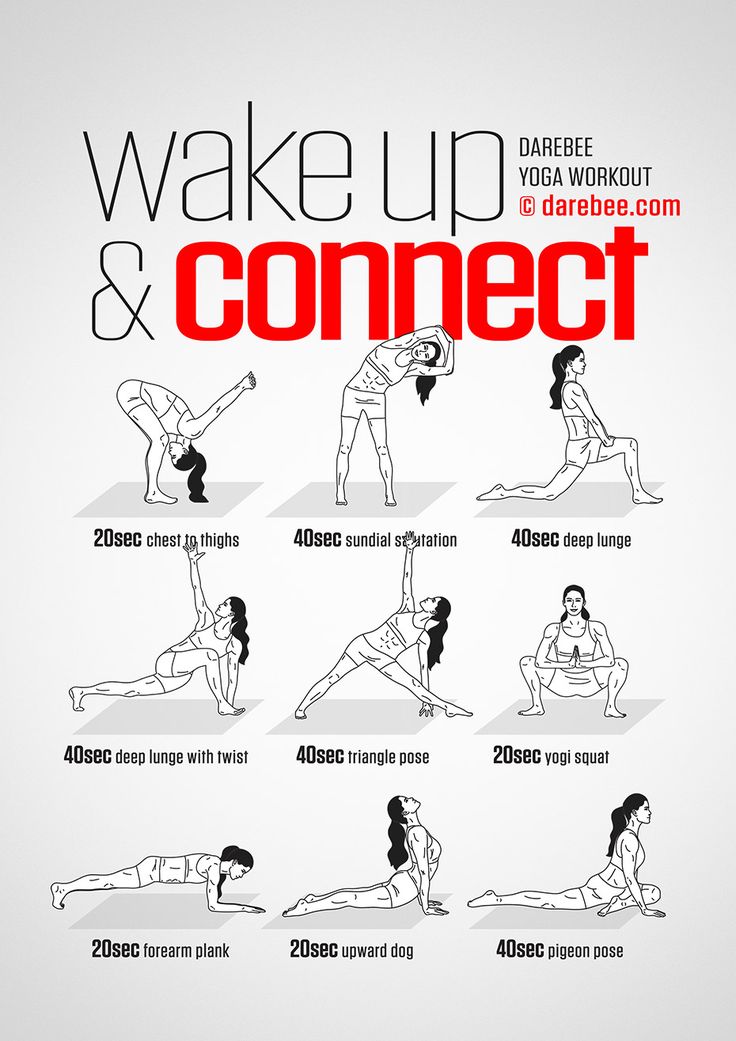

Treating neuropathic itch is difficult because most anti-itch medications do not provide relief.

Treatments typically involve local anesthetics or physical barriers to prevent scratching, as scratching too much or too hard can cause painful lesions or other unintentional self-injury.

Other treatments and therapies may include:

- lidocaine creams or patches

- anti-seizure drugs, such as gabapentin

- botox injections

- neurostimulation techniques

- some antidepressants

- acupuncture

- meditation and mindfulness

- cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

Other behavioral interventions may include:

- cutting the fingernails

- wearing protective garments

- applying moisturizer regularly

- avoiding warm or hot temperatures

- wearing loose clothing

There is no research on the associated risk factors for neuropathic itch. It is possible for two people to have the same health condition and only one of them experience neuropathic itch as a symptom.

It is possible for two people to have the same health condition and only one of them experience neuropathic itch as a symptom.

In some people, the nervous system injury also causes loss of sensation, leading to constant scratching and eventual self-injury.

In one case, a woman who had neuropathic itch after contracting shingles scratched her head so vigorously that she scratched through her skin and skull right to her brain without experiencing pain. As a result, she had to wear a locked helmet when sleeping.

Skin changes due to constant itching can also occur. If people scratch so much that they break the skin, this can also lead to an infection.

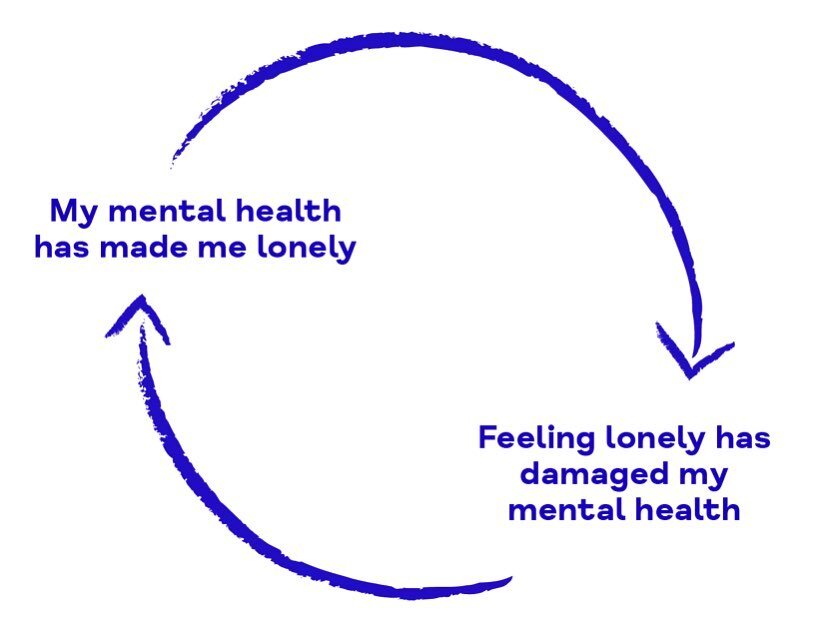

It can be challenging for people to cope with neuropathic itch.

Although an itch may seem innocuous to many people, being unable to find relief from chronic, severe itching can significantly affect a person’s quality of life.

For instance, it can impair their ability to sleep and perform regular activities.

According to an older 2011 study, living with neuropathic itch is similar to living with any other condition that causes chronic pain.

People with this type of chronic pain may benefit from joining a support group or going to therapy sessions.

As neuropathic itch is difficult to treat, management of the condition often involves taking measures to prevent scratching.

People who end up scratching vigorously in their sleep, for example, may need to protect the skin by covering it with a helmet or bandages.

A person with an itch that feels impossible to relieve may be experiencing neuropathic itch.

They should first see a dermatologist to rule out any skin-related conditions, such as eczema or rash.

If topical anti-itch treatments do not work, a consultation with a neurologist may be necessary.

Getting help is essential to prevent complications, which commonly involve skin infection or damage.

People with neuropathic itch may find it helpful to join a support group or get therapy to cope with this form of chronic pain.

Definition, diagnosis, treatment, and outlook

A neuropathic itch is an itch that results from nervous system damage rather than issues with the skin.

Itching is a normal sensation to experience from time to time. However, when an itch results from nervous system damage, doctors call it a neuropathic itch.

A neuropathic itch can feel different than a normal itching sensation. It can occur for various reasons, including stroke. Scratching may not provide relief from this type of itch.

Below, we look at the symptoms, causes, and treatment of neuropathic itch. We also discuss the outlook for people with this condition.

A neuropathic itch happens when there is damage to the nervous system.

Damage to either the central or peripheral nervous system can cause a neuropathic itch, according to an older article from 2010.

While a regular itch results from some kind of issue with the skin, a neuropathic itch has a different, deeper origin.

A neuropathic itch may produce an itching sensation or a feeling of pins and needles. The itching may be very severe.

The itching may be very severe.

Neuropathic itch may also produce the following sensations:

- burning

- wetness

- electric shocks

- pain

- numbness

- crawling

- severe cold

Some people with neuropathic itch may also experience other symptoms such as:

- prickling and chilling of the skin

- increase in skin sensitivity

- decrease in skin sensitivity

In people with neuropathic itch, scratching can also make the itch worse.

There is very little understanding of the bodily mechanisms that create itching sensations.

Research suggests that lesions in the nervous system that damage itch-related neurons may cause neuropathic itch. Conditions and diseases that may cause neuropathic itch include:

- notalgia paresthetica, which is nerve pain that may involve itching of the back

- brachioradial pruritus, a nerve disorder that affects the arms

- peripheral neuropathy, the term for damage to the peripheral nerves that often produces symptoms in the hands and feet

- nerve irritation

- shingles

- stroke

- diabetes

- vitamin deficiencies

- toxin exposure

- trigeminal trophic syndrome, a rare condition that happens because of trigeminal nerve damage

- burns or keloids

- spinal tumor

- brain tumor

- multiple sclerosis

Doctors may have difficulty diagnosing neuropathic itch, as they may initially assume that the problem is skin-related.

However, a dermatologist can rule out any dermatological causes of itching.

Doctors usually prescribe topical treatments to people who present with itching. They may suspect neuropathic itch when these treatments do not work.

However, it can be tough to find the exact cause. If traditional anti-itch therapies do not work, people should consult a neurologist.

Doctors may perform a skin biopsy to check for neuropathic itch.

Treating neuropathic itch is difficult because most anti-itch medications do not provide relief.

Treatments typically involve local anesthetics or physical barriers to prevent scratching, as scratching too much or too hard can cause painful lesions or other unintentional self-injury.

Other treatments and therapies may include:

- lidocaine creams or patches

- anti-seizure drugs, such as gabapentin

- botox injections

- neurostimulation techniques

- some antidepressants

- acupuncture

- meditation and mindfulness

- cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

Other behavioral interventions may include:

- cutting the fingernails

- wearing protective garments

- applying moisturizer regularly

- avoiding warm or hot temperatures

- wearing loose clothing

There is no research on the associated risk factors for neuropathic itch. It is possible for two people to have the same health condition and only one of them experience neuropathic itch as a symptom.

It is possible for two people to have the same health condition and only one of them experience neuropathic itch as a symptom.

In some people, the nervous system injury also causes loss of sensation, leading to constant scratching and eventual self-injury.

In one case, a woman who had neuropathic itch after contracting shingles scratched her head so vigorously that she scratched through her skin and skull right to her brain without experiencing pain. As a result, she had to wear a locked helmet when sleeping.

Skin changes due to constant itching can also occur. If people scratch so much that they break the skin, this can also lead to an infection.

It can be challenging for people to cope with neuropathic itch.

Although an itch may seem innocuous to many people, being unable to find relief from chronic, severe itching can significantly affect a person’s quality of life.

For instance, it can impair their ability to sleep and perform regular activities.

According to an older 2011 study, living with neuropathic itch is similar to living with any other condition that causes chronic pain.

People with this type of chronic pain may benefit from joining a support group or going to therapy sessions.

As neuropathic itch is difficult to treat, management of the condition often involves taking measures to prevent scratching.

People who end up scratching vigorously in their sleep, for example, may need to protect the skin by covering it with a helmet or bandages.

A person with an itch that feels impossible to relieve may be experiencing neuropathic itch.

They should first see a dermatologist to rule out any skin-related conditions, such as eczema or rash.

If topical anti-itch treatments do not work, a consultation with a neurologist may be necessary.

Getting help is essential to prevent complications, which commonly involve skin infection or damage.

People with neuropathic itch may find it helpful to join a support group or get therapy to cope with this form of chronic pain.

Why does it itch

Reading the introduction to a recent article by Nobel laureate Ardem Pataputyan on itching, I scratched myself at least ten times. The skirt will slide down the ankle. Then a fly will run over your shoulder. Then they hurt an ear rubbed with an earring and a mosquito bite on the knee. Toward the middle of the paragraph, the right hand itched - in several places at once. A couple more times I had to scratch out of empathy for the experimental mice. Then I stopped counting (although I didn’t stop scratching). But I thought: were these ten different reasons for itching or one and the same? It turned out that until now no one knows exactly how many there are. nine0003

If, even before reading this article, I had been asked to classify my impulses to scratch, I would probably have divided them simply into external and internal. I would classify the skirt and the fly as the first, they irritate the surface of the skin. Mosquito and earring - to the second: at the moment when I felt itching, the mosquito had long since pulled its proboscis out of my knee, and my ear got rid of the earring. All that remains of them is inflammation, and it is localized under the skin - it itches there.

Mosquito and earring - to the second: at the moment when I felt itching, the mosquito had long since pulled its proboscis out of my knee, and my ear got rid of the earring. All that remains of them is inflammation, and it is localized under the skin - it itches there.

If you take classification seriously, then everything will turn out to be much more complicated. To recognize the existence of any sensation with neurophysiological accuracy, you need to find at least a separate receptor for it - or better, a separate path of neurons that leads from this receptor to the brain. nine0003

Itching against pain

In the middle of the 20th century, itching was considered a form of pain. Neurophysiologists proved it this way: if you take a painful stimulus (for example, an electric current) and reduce its intensity, then at some point the subject stops feeling pain. There will be only a barely noticeable touch that you want to brush off by scratching. And since one goes into another, it means that there are no special signaling pathways for itching, it uses the channel of pain - and therefore, it cannot be considered a separate feeling. nine0003

And since one goes into another, it means that there are no special signaling pathways for itching, it uses the channel of pain - and therefore, it cannot be considered a separate feeling. nine0003

In the late 1980s, scientists tried to go the other way: they started with a stimulus that caused a slight itch, and gradually increased it. To do this, they used histamine (a signaling molecule that is released during inflammation and allergies): it was injected into the subjects under the skin in increasing concentrations and asked to evaluate the intensity of the resulting itching. It turned out that people appreciate the strength with which they want to scratch - but even at high doses (more than 10 micrograms, if you increase them further, then the strength of the itch no longer grows), this feeling does not turn into pain. nine0003

Since then, the itch has slowly begun to regain its independence. The new feeling needed to find sensory neurons and receptors. But it wasn't that easy. To find the nerve fibers that transmit signals about itching from the skin, it was necessary to solve an even more tricky problem - to come up with some kind of stimuli that would only cause itching, and no other sensations. That is, to act on the subjects in such a way as not to affect other sensory neurons.

To find the nerve fibers that transmit signals about itching from the skin, it was necessary to solve an even more tricky problem - to come up with some kind of stimuli that would only cause itching, and no other sensations. That is, to act on the subjects in such a way as not to affect other sensory neurons.

For the first time, scientists managed to do this again for histamine, at 1997 (at the same time, by the way, David Julius discovered the first pain receptor, TRPV1, and in 2021 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for this, our text “Award for well-being” is about this). The researchers injected microelectrodes under the skin of the legs of the subjects to record the activity of individual fibers in the cutaneous branch of the peroneal nerve. Then, by applying a light current to different areas of the skin, they looked for which area on the leg a particular fiber was taking signals from. And then they checked what kind of stimuli the fiber was responding to. After weeding out those neurons that responded to pressure and temperature, the researchers tried to act on the remaining ones with histamine. And in order not to hurt with an injection (and not immediately spoil the experiment), it was injected using iontophoresis: a sponge with a solution of histamine was placed on a person’s leg and with the help of a weak current they forced it to flow through the skin. nine0003

And in order not to hurt with an injection (and not immediately spoil the experiment), it was injected using iontophoresis: a sponge with a solution of histamine was placed on a person’s leg and with the help of a weak current they forced it to flow through the skin. nine0003

Thus, nerve fibers were found that reacted only to histamine - and made the subjects feel itchy. These were type C axons - thin, slow, without myelin sheath. The same type of neurons transmit pain and warmth signals from the skin.

Later, however, it turned out that these fibers can also respond to certain pain stimuli. And the argument about the independence of itching from pain flared up again. Sensitive neurons for itching, which finally aroused no one's suspicions, were found only in 2009year in mice. When these neurons were killed, histamine could no longer make the animals itch, although they reacted to pain in the same way as before.

Now no one doubts the independence of the itch. But he did not succeed in completely separating himself from the pain. From time to time, common signaling pathways are found in them, and TRPV1 pain receptors are found on some itch neurons. And even articles on itching continue to appear in Pain .

From time to time, common signaling pathways are found in them, and TRPV1 pain receptors are found on some itch neurons. And even articles on itching continue to appear in Pain .

Malaria, allergies and opioids

The human eye detects three basic colors, the tongue responds to five basic tastes, and the number of molecules that make our nose smell is probably in the thousands (we discussed this in the Phenomenology of Spirit text). How many causes of itching is still an open question. And not at all idle. How many different neural pathways transmit a signal about itching, so many drugs may be required for it. Chronic itching can be a very annoying problem, and sometimes it can be deadly. Thus, the American surgeon and writer Atul Gawande relates the story of a woman who scratched the same point on her head for days on end, even in her sleep - and for so long that she once damaged one of the lobes of her brain by rubbing her skull. And if it is not known which way the signal goes, then it is completely incomprehensible (as was the case with this woman) how to treat such an itch. nine0003

And if it is not known which way the signal goes, then it is completely incomprehensible (as was the case with this woman) how to treat such an itch. nine0003

Even at the time when itching was being separated from pain, it was obvious that histamine was not the only causative agent. Non-inflamed areas can also itch, for example, those through which a barely noticeable electric current runs. But to prove that itching can also be caused mechanically was much more difficult. It was necessary to choose a tactile stimulus that, on the one hand, would cause the same strong desire to itch as histamine, and on the other hand, could not turn out to be a very slight pain.

This was only possible in 2013. To do this, the scientists assembled a setup in which a thin wire swung along the skin on the subjects' faces so as to touch only the hairs on it, but not its surface. Thus, the researchers ruled out pain sensitivity - because the endings of pain neurons are recessed inside the epidermis. However, the C-fibers in the skin started working in response to such a stimulus. And according to the estimates of the participants in the experiment, the itching turned out to be no weaker than histamine. But it felt differently: the subjects did not feel any burning and tingling, which occur with inflammation. nine0003

However, the C-fibers in the skin started working in response to such a stimulus. And according to the estimates of the participants in the experiment, the itching turned out to be no weaker than histamine. But it felt differently: the subjects did not feel any burning and tingling, which occur with inflammation. nine0003

Later, special neurons were found in the spinal cord for such itching: their shutdown blocked the desire to scratch in response to mild irritation, but did not affect the response to histamine. So neurophysiologists divided itching into chemical and mechanical.

Such a classification at first glance differs little from the division into external and internal. Mechanical stimuli, like a fly and a skirt, are external, while chemical stimuli, like a mosquito bite, would seem to be internal. But in fact, everything is arranged more cunningly. nine0003

For example, chemical itching can be caused not only by histamine, but by a whole bunch of different substances - and each has its own receptor. So, in the early stages of studying itching, scientists often tested volunteers with the help of burning mucuna. The hairs on its fruits cause an intense desire to scratch - and this desire, if succumbed to it, easily spreads over the skin. This is because a person with his own hands only smears pruritogen (that is, an itchy substance) over himself. In Mucuna, this is mucunain, a serine protease that appears to act on PAR-2 and PAR-4 receptors. In a similar way - by releasing proteases - dust mites provoke itching. nine0003

So, in the early stages of studying itching, scientists often tested volunteers with the help of burning mucuna. The hairs on its fruits cause an intense desire to scratch - and this desire, if succumbed to it, easily spreads over the skin. This is because a person with his own hands only smears pruritogen (that is, an itchy substance) over himself. In Mucuna, this is mucunain, a serine protease that appears to act on PAR-2 and PAR-4 receptors. In a similar way - by releasing proteases - dust mites provoke itching. nine0003

It turns out that sometimes chemical itching can be caused by an external stimulus, which means that the division into internal-chemical and external-mechanical no longer works.

Internal chemical itching is also not necessarily associated with histamine. So, if I was bitten not by an ordinary mosquito, but by a malarial one, I might have an additional reason to itch. I would then have to start taking chloroquine - and Mgpr receptors react to it, causing itching.

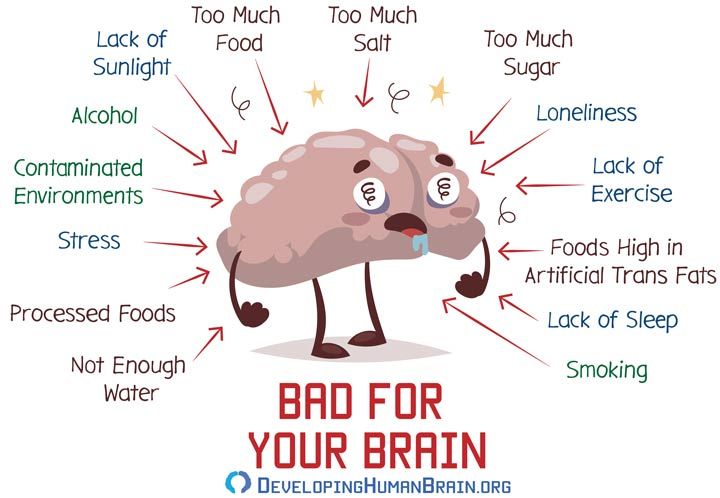

Non-histamine itching is also caused by opioids, and also by bile acids, when bile stasis accumulates in the blood and tissues, where they are recognized by the TGR5 receptor. Finally, chemical pruritus neurons respond to a variety of pro-inflammatory molecules, such as interleukins, that are released by both immune and normal skin cells in a variety of situations, such as atopic dermatitis or allergies. nine0003

So there may be more than two reasons that make me itch. Other than skirt flies and histamine, I may be tormented by some kind of non-histamine chemical stimulus. And although I do not suffer from malaria or bile stasis, it can be, for example, an allergy that I find myself from time to time - either to wool, or to dust, or to unknown flowering bushes. But what about the itching that occurs literally out of the blue - without bites, running flies and allergic spots?

Where it itches from

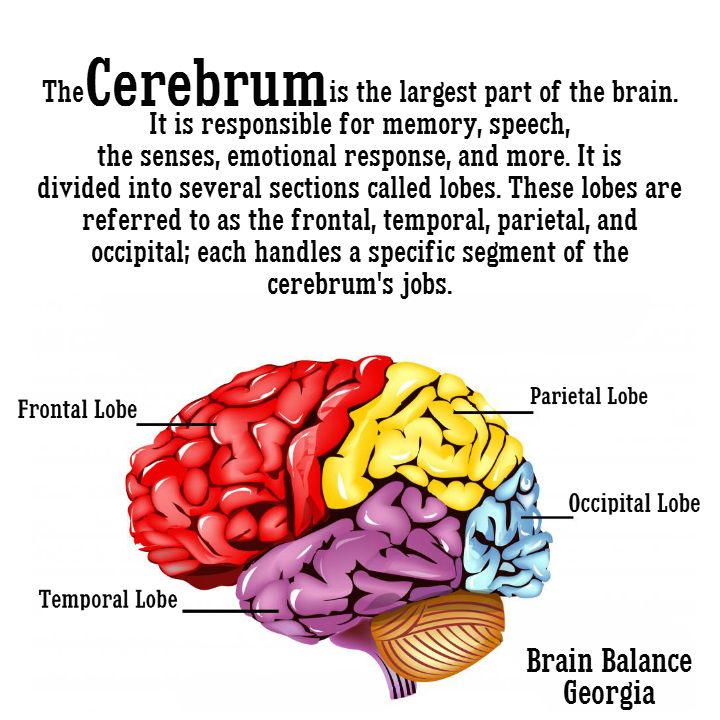

Like any other sensation, itching is produced by a complex network of neurons - and many of them are not even in the skin, but in the central nervous system. Neurons in the spinal cord, on their way to and from it, support or, conversely, plug each other in order to adjust the strength of the signal depending on the circumstances. And then already in the brain there is a desire to itch - which a person can satisfy or (if the itch is not too strong) ignore. And on this long journey, anything can break. nine0003

Neurons in the spinal cord, on their way to and from it, support or, conversely, plug each other in order to adjust the strength of the signal depending on the circumstances. And then already in the brain there is a desire to itch - which a person can satisfy or (if the itch is not too strong) ignore. And on this long journey, anything can break. nine0003

It may turn out that there is no external stimulus at all, but the desire to scratch still appears as if from nowhere. This is because some of the neurons in the itch transmission chain are themselves too excited - this is called sensitization . Therefore, even paralyzed parts of the body or those that have lost other types of sensitivity can itch (this is somewhat similar to chronic and phantom pains - which we wrote about in the text “It just hurts”).

This itch does not have a special receptor and a separate neural pathway, it's just a failure in the system. But there is a name, neuropathic pruritus, and this is a serious challenge for doctors. Since the problem lies deep in the nervous system, it is quite difficult to treat it - it is not enough just to block some receptor or bind excess histamine. And such itching causes a lot of trouble for patients, even if you do not take into account physical discomfort and a reduced quality of life. It can be so strong that people comb their skin to non-healing wounds. And the woman who combed through her skull, too, most likely had neuropathic itching - she had previously had shingles, and the herpes virus that caused it may have killed the neurons that inhibited extra itching signals from the scalp. nine0003

Since the problem lies deep in the nervous system, it is quite difficult to treat it - it is not enough just to block some receptor or bind excess histamine. And such itching causes a lot of trouble for patients, even if you do not take into account physical discomfort and a reduced quality of life. It can be so strong that people comb their skin to non-healing wounds. And the woman who combed through her skull, too, most likely had neuropathic itching - she had previously had shingles, and the herpes virus that caused it may have killed the neurons that inhibited extra itching signals from the scalp. nine0003

Sometimes itching appears literally “from the head”: a constant desire to scratch can be a companion of various mental problems (that is, disorders already at the brain level) - such as anxiety or obsessive-compulsive disorder. In this case, too, the external stimulus does not matter much. And then, of course, there is what I feel like empathy for experimental mice, and neuroscientists call the contagious itch - but how it actually works is not really clear.

Sensitization can manifest itself in another way - the desire to scratch occurs in response to stimuli that are too weak to cause itching normally. For example, mechanical itching is easier to provoke around a mosquito bite than on healthy skin. This phenomenon is called allocnesia , and it is still not easy to deal with.

It is not known exactly why the nerve fibers become more sensitive than they should be. Previously, it was thought that this is the result of a collision of several signals at the level of the spinal cord. For example, if a person has an inflamed area of \u200b\u200bthe skin - like after a mosquito bite - then the neurons of the histamine pathway continuously send signals to the spinal cord. Because of this, the receiving neurons of the spinal cord are constantly excited - and more easily respond to any stimulus from the neurons of mechanical itching, even if it is subthreshold and should normally be ignored. nine0003

Then it turned out that sensitization can occur right on the spot, without reaching the spinal cord. It turned out that other sensory fibers - Merkel cells, they are responsible for touch - block the itch neurons. Perhaps this is necessary so that a double signal does not go into the nervous system, that is, so that the place with which we feel something does not itch. But it happens that the blocking stops working - for example, with age, when there are fewer tactile fibers in the skin. And the itching is getting worse. nine0003

It turned out that other sensory fibers - Merkel cells, they are responsible for touch - block the itch neurons. Perhaps this is necessary so that a double signal does not go into the nervous system, that is, so that the place with which we feel something does not itch. But it happens that the blocking stops working - for example, with age, when there are fewer tactile fibers in the skin. And the itching is getting worse. nine0003

And now the team of Ardem Pataputyan, the scientist who shared the 2021 Nobel Prize for pain and mechanoreception with David Julius, has found a third mechanism. Pataputyan and colleagues found that sensitization can occur even at the level of a single cell - and through her own fault.

Too touching

In 2010 Pataputyan discovered mechanical sensitivity receptors: Piezo1 and Piezo2. Both of them were found in the cells of the internal organs - there they perceive pressure and stretching and help coordinate their work (for example, with their help the nervous system decides that it is time to inhale or exhale). In addition, Piezo2 Pataputyan found in the upper layers of the skin - there they sit on the membranes of Merkel cells, which transmit mechanical tactile signals. But they are not directly involved in the appearance of itching - it was believed that only one type of fiber with other receptors, LTMR, transmits signals of mechanical itching. nine0003

In addition, Piezo2 Pataputyan found in the upper layers of the skin - there they sit on the membranes of Merkel cells, which transmit mechanical tactile signals. But they are not directly involved in the appearance of itching - it was believed that only one type of fiber with other receptors, LTMR, transmits signals of mechanical itching. nine0003

In the article that made me count my scratching impulses, Pataputian and his colleagues write that they noticed something new: it turns out that there is also Piezo1 in the sensory neurons of the skin (at least in mice). But not in those that are responsible for tactile sensations. And in the neurons that are responsible for histamine itch.

This finding does not look like a mistake or an accident: the researchers checked that the receptors are working, that is, they cause an impulse in a neuron in response to a blunt needle touching its surface. In addition, mice lacking gene Piezo 1 itch much less in response to mechanical stimuli, which means that Piezo1 is involved in their perception. Thus, the same sensory neurons were found to be responsible for both chemical itch and mechanical itch.

Thus, the same sensory neurons were found to be responsible for both chemical itch and mechanical itch.

Then the scientists acted on these neurons with two stimuli in a row: first they pricked the mice with histamine, and then they tickled them with a thread that is too thin to make the animals itch normally. And it turned out that sensitization works: after these neurons were treated with histamine, their threshold of mechanical sensitivity dropped, and the mice began to itch from a barely noticeable touch. It turned out that allocnesia can work at the level of a single neuron: first, the cell is excited by a chemical stimulus, and then it gives out a pathologically strong response to touching with a thread. nine0003

Now it's even harder to figure out why people feel itchy in any given situation—and how many different scenarios made me itchy. If until now neurophysiologists unequivocally divided itching into mechanical and chemical (and also neuropathic, without external stimulus), now it becomes clear that the signaling pathways for these types of sensitivity overlap. And the mechanical itch itself was not so simple. It will also have to be divided.

And the mechanical itch itself was not so simple. It will also have to be divided.

-

The first one is classical, described in 2013. LTMR receptors (low threshold) are responsible for it, the same ones that are involved in the appearance of tactile sensations. The fibers that carry the signals of this itch belong to the Aβ group - these are relatively thick and fast axons. nine0003

-

The second is a newly discovered one that works through chemical itch neurons. These are cells with markers Nppb and Sst , they usually respond to histamine - but, as it has now become clear, they can also respond to mechanical stimuli. And send signals over C-fibers, thin and slow.

Pataputyan and colleagues suggest that these two types of itch have different purposes. Quick signals are needed for a quick response - to straighten the hem of a skirt or drive a fly off your shoulder. It is useless to transmit such information along slow axons. They are needed, apparently, for something else - to signal a problem that will not go anywhere quickly - for example, about subcutaneous parasites. When meeting with them, neurons respond to a chemical stimulus, that is, to histamine, which is released during inflammation, and at the same time lower the excitability threshold for mechanical stimuli. And they begin to react to every smallest movement of the parasite, causing the host to have an acute desire to itch, until he kicks the stranger out from under the skin. nine0003

They are needed, apparently, for something else - to signal a problem that will not go anywhere quickly - for example, about subcutaneous parasites. When meeting with them, neurons respond to a chemical stimulus, that is, to histamine, which is released during inflammation, and at the same time lower the excitability threshold for mechanical stimuli. And they begin to react to every smallest movement of the parasite, causing the host to have an acute desire to itch, until he kicks the stranger out from under the skin. nine0003

But even here, perhaps, attempts to classify itching will not end. Pataputian's group discovered another group of neurons that has Piezo1. These are also chemical itch neurons, but different - they carry Mrgprd receptors, which usually respond to the non-canonical amino acid beta-alanine. How their signaling pathway works and what role they play in this system has yet to be understood.

So we are not yet ready to unequivocally list all the mechanisms that trigger itching in our body. And it may turn out that each of those times that I scratched myself while writing this text, my body gave me completely different signals. nine0003

And it may turn out that each of those times that I scratched myself while writing this text, my body gave me completely different signals. nine0003

Polina Loseva

To scratch or not to scratch, that is the question. Scientists answer

Subscribe to our newsletter "Context": it will help you understand the events.

Image copyright, Getty Images

There isn't much scientific knowledge about itching and scabies, but this under-appreciated field of medicine can reveal some amazing facts about the human brain.

We have collected 12 facts that will make you scratch your head. nine0003

1. You scratch yourself about 97 times a day

Image copyright, Getty Images

According to research, each of us itches about 100 times a day. Probably, and at you now something itches. Scratch, no one will notice.

2. The urge to scratch is caused by toxins left on the skin by animals or plants.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Toxins cause the release of histamine, part of the body's immune response. As a result, nerve fibers begin to send "itchy" signals to the brain. The simplest example is a meeting with a jellyfish. nine0003

3. Scratching has its own nervous system

Image credit: Getty Images itching respond to certain nerve fibers.

4. Signals that something itches are transmitted very slowly

Image copyright, Getty Images

Nerve fibers have different speeds:

- touch signal transmission speed - 321 km/h

- "rapid pain" (which you experience if, for example, you accidentally touch a hot stove) is transmitted at a speed of 128 km/h

5.

The desire to scratch is contagious

The desire to scratch is contagious Image credit: Getty Images

Scientists proved this by showing groups of mice videos of other mice scratching. The watching group also began to scratch themselves.

6. The suprachiasmatic nucleus is responsible for contagious scratching

Image copyright, Getty Images

Neuroscientists don't yet know how a tiny part of our brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus is involved in observing scratching and generating the desire to scratch.

7. The desire to scratch is the best way to deal with itching caused by insects or plants

Image copyright, Getty Images

It helps get rid of any pesky insects or poisonous plants, and also dilates the blood vessels, allowing white blood cells and plasma to wash away toxins. It is because of this flush that the skin becomes red and blotchy. nine0003

nine0003

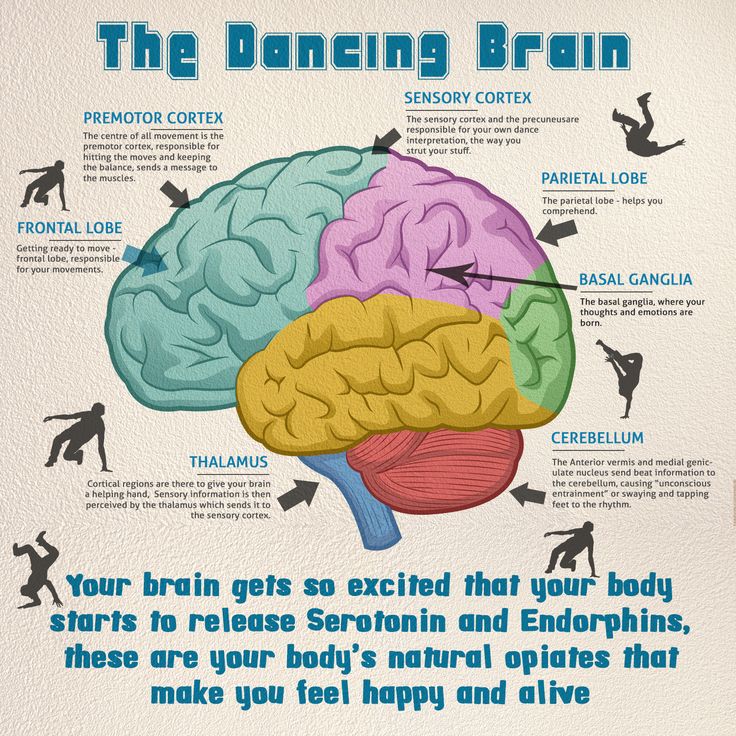

8. Scratching is pleasant because it releases serotonin into the brain.

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that scientists attribute to feelings of well-being and happiness. The more serotonin circulates throughout the body, the happier you feel. No wonder it's sometimes hard to stop scratching.

9. The most pleasant place to scratch is the ankle...

Image copyright, Getty Images

At least according to a study published in the British Journal of Dermatology in 2012. nine0003

Results have shown that itching is felt most intensely at the ankle, but this is also where the pleasure of scratching is felt most strongly and lasts the longest.

Are you scratching your ankle just now to test the findings of British scientists? Just be honest.

10. The more you scratch, the more it itches

When you scratch your skin, histamine is released into the bloodstream, and more itchy signals are sent to the brain.