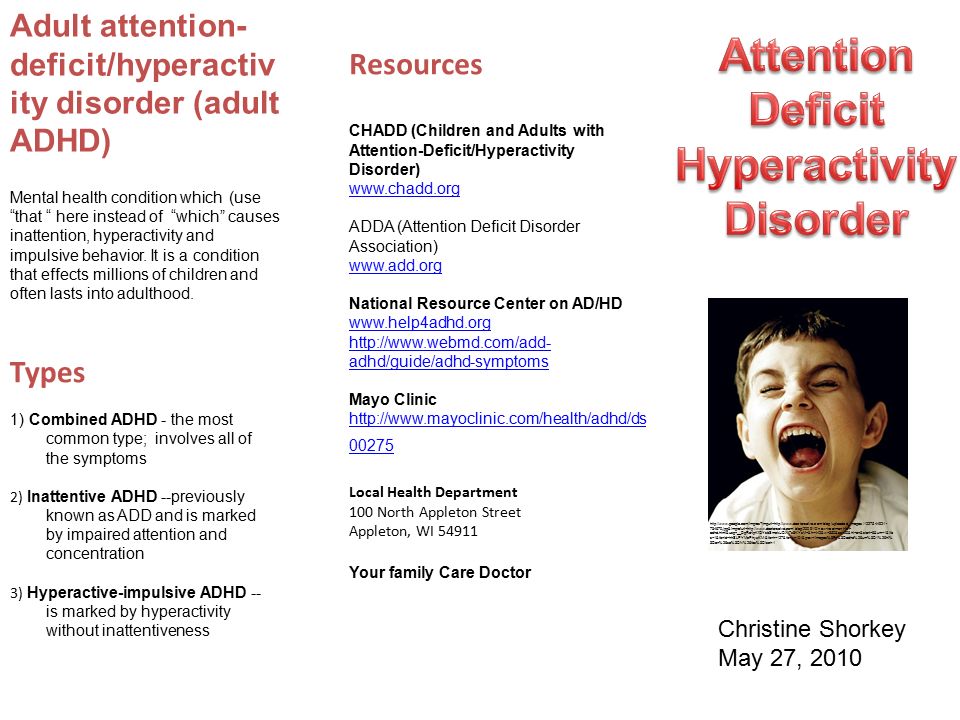

Anger issues in children with adhd

Why is My Child So Mad & Aggressive?

Anne dreads waking up in the morning. Her son, Sam — who has ADHD and an anger disorder — is unpredictable. Sometimes he just goes along with the morning routine. Other times, he’ll lash out at the smallest thing — a request to get dressed, an unplanned stop on the way to school, or a simple “No” to a request for pizza for dinner.

“On any given day, I never know what to expect from him,” says Anne, a public relations manager for an independent high school in New England. “He’ll start yelling and kicking when anything doesn’t go his way.”

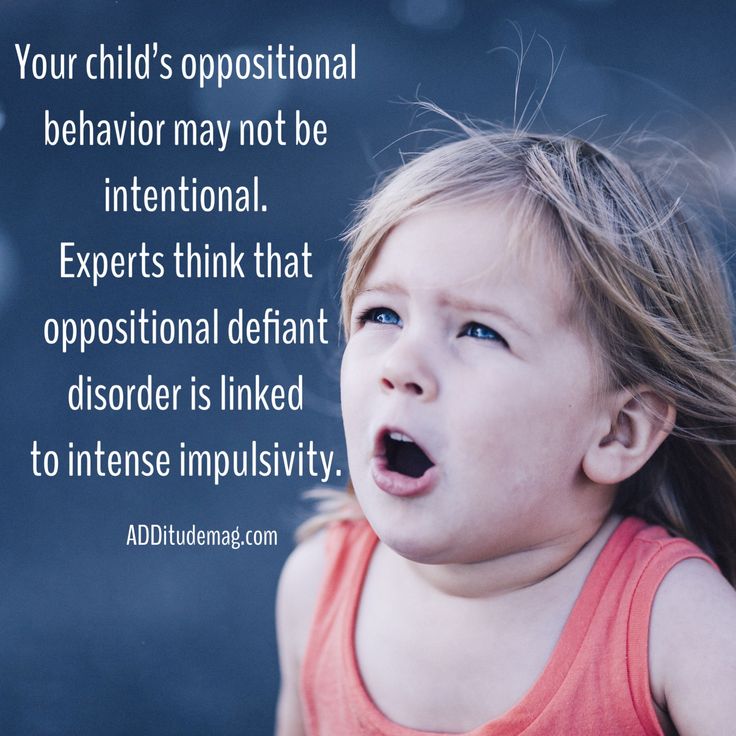

Sam was diagnosed with attention deficit disorder (ADHD or ADD) at five, and while that explained some of his difficulties in school, it never explained his aggressive and defiant temperament. It wasn’t until the beginning of this school year that Anne sought additional help for her son’s behavior, which was becoming stressful to her family. The pediatrician determined that Sam was suffering from ADHD and ODD (oppositional defiant disorder).

How Do You Recognize ODD in a Child with ADHD?

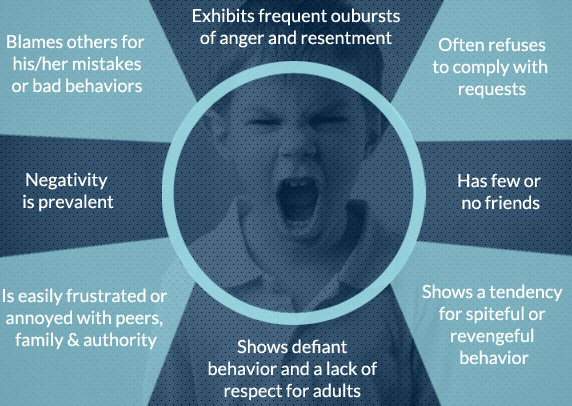

Children with ODD have a pattern of angry, violent, and disruptive behaviors toward parents, caretakers, and other authority figures. Before puberty, ODD is more common in boys, but, after puberty, it is equally common in both genders. Sam is not alone in his dual diagnosis of ADHD and ODD; up to 40 percent of children with ADHD are estimated to have ODD.

Every child will act out and test his boundaries from time to time, and ODD seems like typical adolescent behavior: arguing, anger, and aggression. The first step to fixing a child’s problematic behavior is recognizing ODD. How do you know whether your child is just being a child or if he needs professional help?

[Could Your Child Have Oppositional Defiant Disorder? Take This Symptoms Test]

There is no clear line between “normal defiance” and ODD, says Ross Greene, Ph.D., associate clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and author of The Explosive Child and Lost at School (#CommissionsEarned). The lack of clear criteria explains why professionals often disagree as to whether a child should be diagnosed with ODD.

The lack of clear criteria explains why professionals often disagree as to whether a child should be diagnosed with ODD.

Greene emphasizes that it is up to parents to decide when to get help for a defiant child. “If you’re struggling with your child’s behavior, and it is causing unpleasant interactions at home or at school, then you’ve easily met the criteria for having a problem,” says Greene. “And I’d suggest you seek professional help.”

Anne had never heard of ODD when she called a cognitive behavioral therapist to discuss coping strategies for her son’s erratic behavior. After spending some time in the family’s home, observing Sam and his interactions with his mother, the therapist saw signs of ODD. “I didn’t know what she was talking about,” says Anne. At Sam’s next doctor’s visit, Anne asked whether ODD could explain Sam’s behavior, and the physician said yes.

“When I thought about it, the diagnosis made sense,” says Anne. “Nothing I used with my older daughter – like counting down to some set consequence before punishing her – to control her behavior ever worked for Sam. ”

”

[Get This Free Download: How to Treat ODD in Kids]

Another mother, Jane Gazdag, an accountant from New York, began noticing troubling behavior in her son, Seamus Brady, now eight, when he was four. “He would scream for two or three hours over the smallest thing,” says Jane. “He fought everything.”

When Jane realized that she had stopped trying to do fun things with her son, like spending the day in Manhattan, because they were too stressful for her, she suspected that he had ODD and spoke to her pediatrician about it. Seamus was diagnosed as having it.

Signs of ODD can be seen in a child’s behavior toward his primary caregiver. The defiant behavior may spread to a secondary caregiver and to teachers or other authority figures, but if it appears in a child with ADHD, ODD will appear within two years of an ADHD diagnosis.

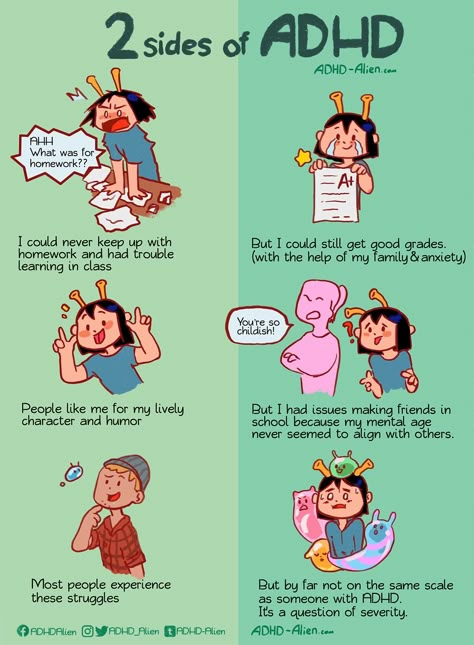

If a child does start to become defiant, there is an easy way to tell whether that behavior is a consequence of ADHD or is a sign of ODD. “ADHD isn’t a problem with starting a task, it’s a problem with finishing a task,” says Russell Barkley, Ph.D., a clinical professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the Medical University of South Carolina. “If a child can’t start a task, that’s ODD.”

“ADHD isn’t a problem with starting a task, it’s a problem with finishing a task,” says Russell Barkley, Ph.D., a clinical professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the Medical University of South Carolina. “If a child can’t start a task, that’s ODD.”

The Impulsive/Defiant Link: How ADHD and Anger Disorders Overlap

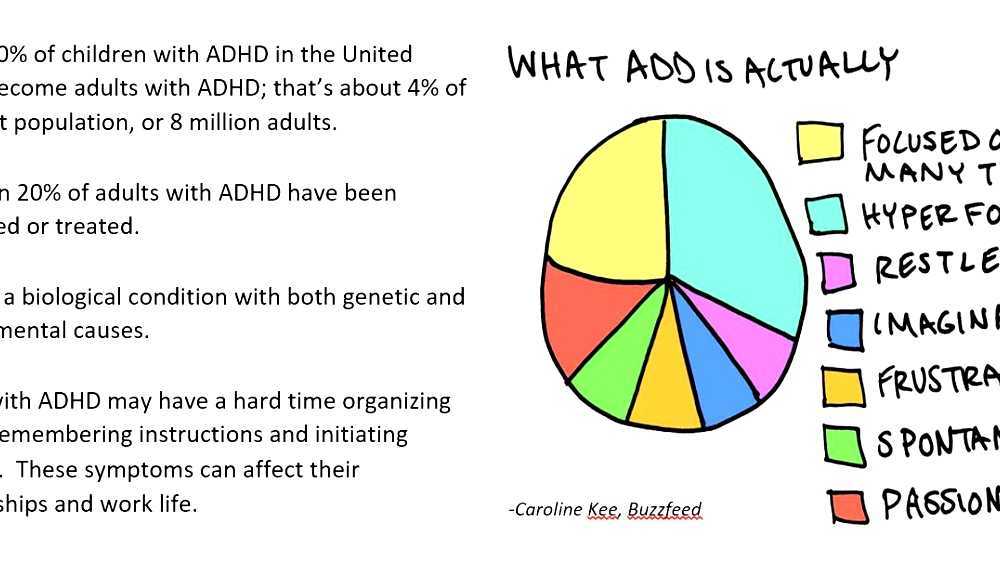

Understanding why ODD is found so frequently in children with ADHD is to understand the two dimensions of the disorder – the emotional and social components, says Barkley. Frustration, impatience, and anger are part of the emotional component. Arguing and outright defiance are part of the social aspect.

Most children with ADHD are impulsive, and this drives the emotional component of ODD. “For people with ADHD, emotions are expressed quickly, whereas others are able to contain their feelings,” says Barkley. This is why the small subset of children who have the inattentive type of ADHD is less likely to develop ODD. Children who have ADHD, along with intense impulsivity, are likely to be diagnosed with ODD.

Anger and frustration are hard to manage in a child with ODD and ADHD, but it is defiance that exacerbates the family stress caused by ODD. The surprising thing is that parents fuel the defiance. If a parent is quick to give in when a child has a tantrum, the child learns that she can manipulate situations by getting angry and putting up a fight. This aspect of ODD is a learned behavior, but it can be unlearned through behavioral therapy.

How Should Parents Treat ADHD and ODD?

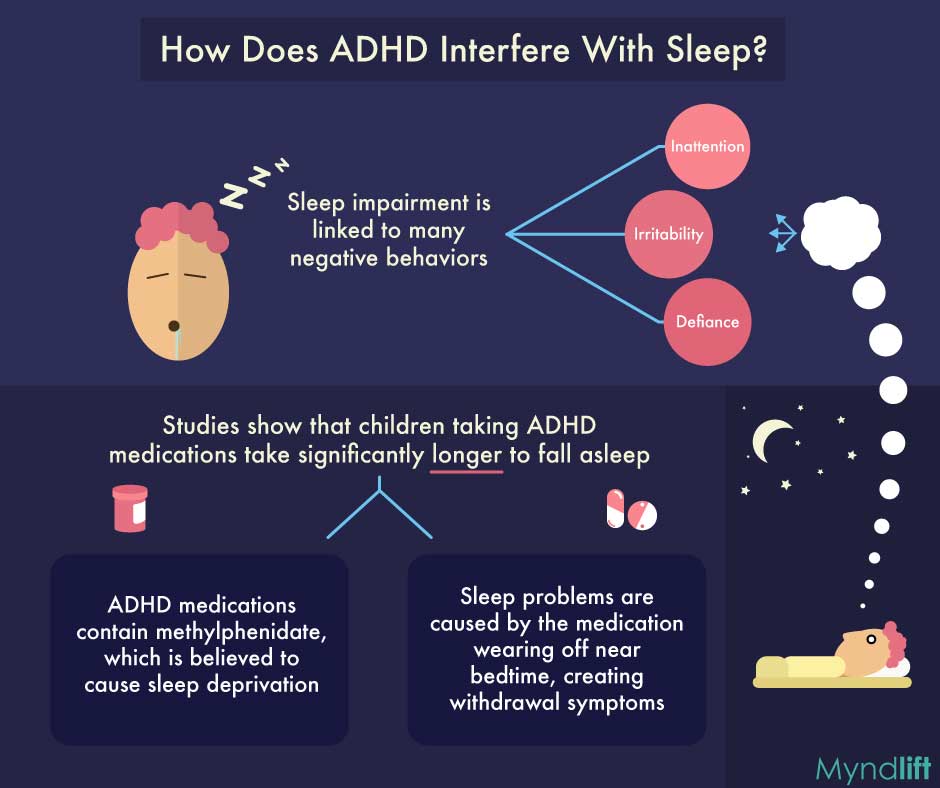

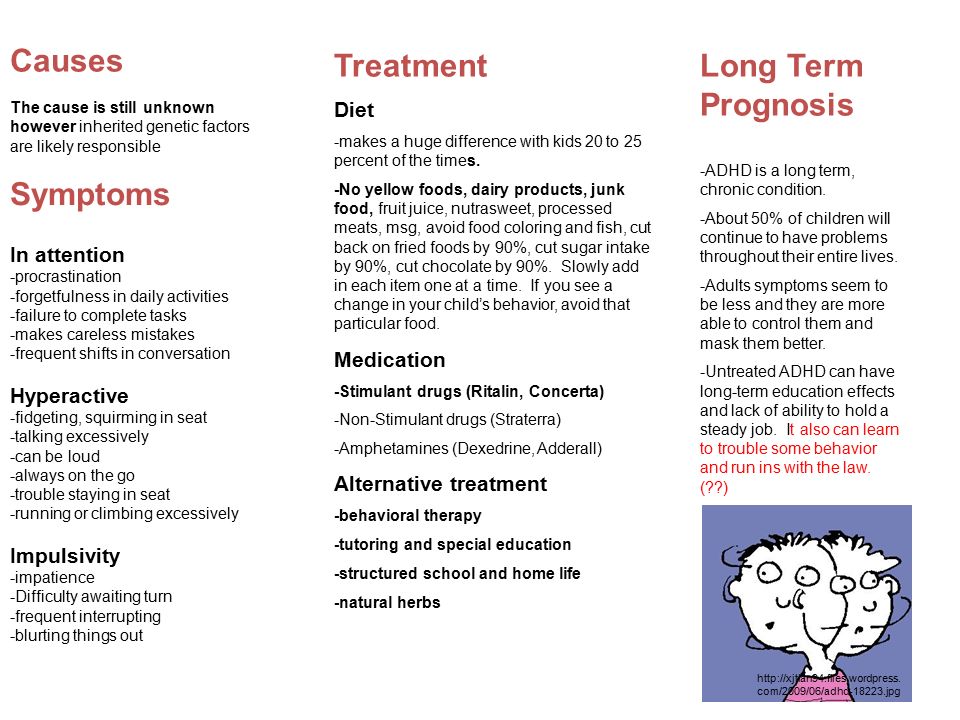

Before tackling a child’s ODD, it is important that his ADHD be controlled. “When we reduce a child’s hyperactivity, impulsiveness, and inattention, perhaps through medication, we see simultaneous improvement in oppositional behavior,” says Greene.

The traditional stimulant medications are the initial drugs of choice because they have been shown to decrease the impairments of ADHD, as well as ODD, by up to 50 percent in more than 25 published studies, says William Dodson, M.D., who specializes in the treatment of ADHD, in Greenwood, Colorado. Non-stimulant medications may also help. In one study, researchers found that the drug atomoxetine, the generic form of the active ingredient found in Strattera, significantly reduces ODD and ADHD symptoms. The researchers note in the study, published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, in March 2005, that higher doses of the medication were needed to control symptoms in children who were diagnosed with both conditions.

Non-stimulant medications may also help. In one study, researchers found that the drug atomoxetine, the generic form of the active ingredient found in Strattera, significantly reduces ODD and ADHD symptoms. The researchers note in the study, published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, in March 2005, that higher doses of the medication were needed to control symptoms in children who were diagnosed with both conditions.

Strattera helped Seamus control his emotions, reducing the number and intensity of his tantrums. “It made a big difference,” says Jane. For some, medication is not enough, and after a child’s ADHD symptoms are under control, it’s time to address ODD behaviors.

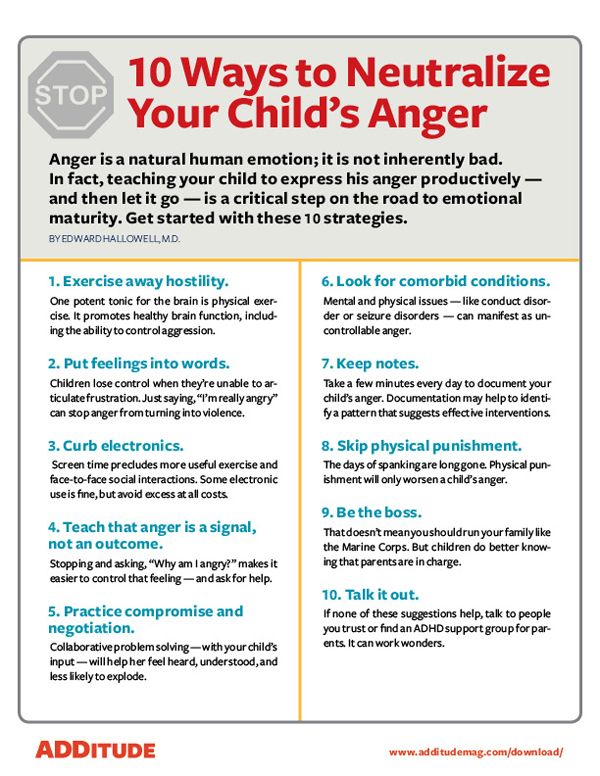

Although there is little evidence to show that any treatment is effective in treating ODD, most professionals agree that behavioral therapy has the most potential to help. There are many forms of behavioral therapy, but the general approach is to reward good behavior and provide consistent consequences for inappropriate actions and behaviors.

Behavioral therapy programs don’t start with the child; they start with the adult. Because a child with ODD usually has a caretaker who gives in to tantrums and violent behavior, or offers inconsistent punishment for bad behavior, the child thinks that acting out will get him what he wants. Therefore, a child’s primary caretaker has to be educated to effectively respond to a child with ODD. Another part of parental training is to consider whether ADHD has gone undiagnosed in the parent; adults with the condition are likely to be inconsistent in managing a child’s behavior.

Implementing consistent punishment is only one part of a behavioral therapy program; a parent must learn to use positive reinforcement when a child behaves himself.

How Long Will It Take to Improve an Anger Disorder?

A behavioral therapist works with parent and child together to reduce troubling behaviors. At the top of Anne’s list was her son’s “Shut up,” which he shouted at anyone. Anne kept a tally sheet to list the number of times her son would shout it in a day. At the end of the day, Anne and her son looked at the total together. If the number was under the set goal for the day, she gave him a small reward, a toy or time spent playing video games. Day by day, Sam tried to reduce the number of times he said “shut up,” and Anne tried to be consistent in her punishments.

At the end of the day, Anne and her son looked at the total together. If the number was under the set goal for the day, she gave him a small reward, a toy or time spent playing video games. Day by day, Sam tried to reduce the number of times he said “shut up,” and Anne tried to be consistent in her punishments.

All of a child’s caregivers should participate in the program. Grandparents, teachers, nannies, and other adults who spend time alone with your child must understand that the need for consistency in behavioral therapy extends to them as well.

“ODD has a deleterious effect on relationships and communication between kids and adults,” says Greene. “You want to start improving things as soon as you can.”

Anne believes that her diligence will pay off. “We hope that all the work we’ve done will one day click for Sam,” she says.

[Read This Next: The Facts About Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) and ADHD]

#CommissionsEarned

As an Amazon Associate, ADDitude earns a commission from qualifying purchases made by ADDitude readers on the affiliate links we share. However, all products linked in the ADDitude Store have been independently selected by our editors and/or recommended by our readers. Prices are accurate and items in stock as of time of publication.

However, all products linked in the ADDitude Store have been independently selected by our editors and/or recommended by our readers. Prices are accurate and items in stock as of time of publication.

SUPPORT ADDITUDE

Thank you for reading ADDitude. To support our mission of providing ADHD education and support, please consider subscribing. Your readership and support help make our content and outreach possible. Thank you.

Previous Article Next Article

Emotional Dysreguation, DMDD & Bipolar Disorder

Anger issues stemming from emotional dysregulation – while noticeably missing from diagnostic criteria for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD or ADD) – are a fundamental part of the ADHD experience for a significant number of children and adults. Even when controlling for related comorbid conditions, individuals with ADHD experience disproportionate problems with anger, irritability, and managing other emotions. These problems walk in lock step with the general difficulties in self-regulation that characterize ADHD. Recent findings, however, suggest that problems with emotional regulation, including anger and negative emotions, are genetically linked to ADHD, too.

These problems walk in lock step with the general difficulties in self-regulation that characterize ADHD. Recent findings, however, suggest that problems with emotional regulation, including anger and negative emotions, are genetically linked to ADHD, too.

Ultimately, emotional dysregulation is one major reason that ADHD is subjectively difficult to manage, and why it also poses such a high risk for other problems like depression, anxiety, or negative self-medication. Scientific and clinical attention are now increasingly turning to correct the past neglect of this integral aspect of ADHD.

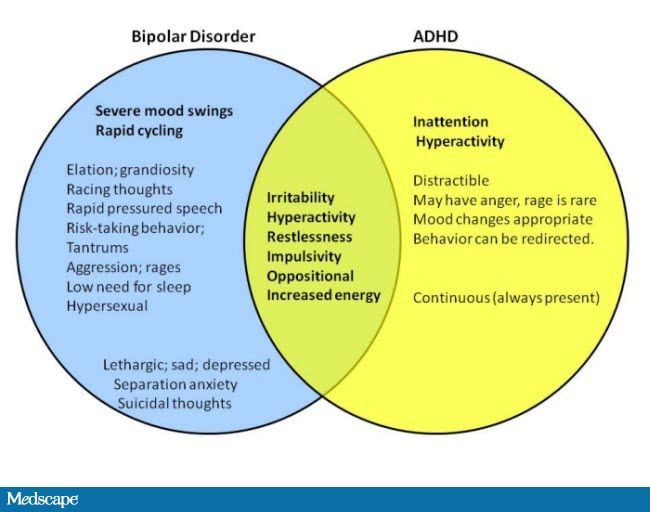

Recognizing this inherent relationship between emotional dysregulation and ADHD is also important when discerning between related and similar conditions, like disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD), bipolar disorder, intermittent explosive disorder (IED), depression, anxiety disorders, and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD). In all, paying mind to anger issues and emotionality in patients with ADHD is crucial for successful treatment and symptom management in the long term.

Anger Issues and ADHD: Theories & Research

Though separated from ADHD in official nomenclature today, emotional dysregulation and anger were connected to ADHD in the mid-20th century before current diagnostic norms were created, and have continued to form part of personal and clinical experiences. Decades ago, when ADHD was known as “minimal brain dysfunction,” criteria for diagnosis actually included aspects of negative emotionality.

Anger problems and emotional dysregulation in individuals with ADHD are sometimes explained by co-occurring mood disorders, such as anxiety or depression. However, these associated disorders do not explain the near universal anger and emotional issues that ADHD individuals experience.

[Click to Read: When It’s Not Just ADHD: Symptoms of Comorbid Conditions]

A critical aspect to consider, then, is ADHD’s nature as a disorder of self-regulation across behavior, attention, and emotion. In other words, any difficulties in regulating our thoughts, emotions, and actions – as is common with ADHD – may explain the irritability, tantrums, and anger regulation issues these individuals experience. And the majority do.

And the majority do.

About 70 percent of adults with ADHD report problems with emotional dysregulation1, going up to 80 percent in children with ADHD2. In clinical terms1, these problem areas include:

- Irritability: issues with anger dysregulation – “tantrum” episodes as well as chronic or generally negative feelings in between episodes.

- Lability: frequent, reactive mood changes during the day. .

- Recognition: the ability to accurately recognize other people’s feelings. Individuals with ADHD may tend to not notice other people’s emotions until pointed out.

- Affective intensity: felt intensity – how strongly an emotion is experienced. People with ADHD tend to feel emotions very intensely.

- Emotional dysregulation: global difficulty adapting emotional intensity or state to situation.

Explaining ADHD and Anger via Emotional Profiles

Emotional dysregulation remains a constant in ADHD even when analyzing personality traits, making the case for emotional profiles or subtypes around ADHD.

[Read: Could High-Tech Brain Scans Help Diagnose ADHD?]

Our own study of children with ADHD that used computational methods to identify consistent temperament profiles found that about 30 percent of kids with ADHD clearly fit a profile strongly characterized by irritability and anger2. These children have very high levels of anger, and low levels of rebound back to baseline – when they get angry, they can’t get over it.

Another 40% had extreme dysregulation around so-called positive affect or hyperactive traits — like excitability and sensation-seeking. Children with this profile also had above-average levels of anger, but not as high as those with the irritable profile.

Thinking of ADHD in terms of temperament profiles also becomes meaningful when considering the role of brain imaging in diagnosing ADHD. Brain scans and other physiological measures are not diagnostic for ADHD because of wide variation in results among individuals with ADHD. However, if we consider brain scans based on temperament profiles, the situation may become clearer. Data from brainwave recordings makes the case that there is distinct brain functioning among children who fall under our proposed irritable and exuberant ADHD profiles2.

Data from brainwave recordings makes the case that there is distinct brain functioning among children who fall under our proposed irritable and exuberant ADHD profiles2.

In eye-tracking tests among the participants, for example, children in this irritable subgroup struggled more than those in any other identified subgroup to take their attention off negative, unhappy faces shown to them. Their brains would activate in the same areas when they saw negative emotions; this did not happen when they saw positive emotions.

Genetic Basis for ADHD and Anger Issues

From a genetics standpoint, it appears that emotional dysregulation is strongly associated with ADHD. Our recent findings suggest that genetic liability for ADHD is related directly to most traits under emotional dysregulation, like irritability, anger, tantrums, and overly exuberant sensation-seeking3. What’s more, irritability appears to have the biggest overlap with ADHD versus other traits, like excessive impulsivity and excitement, in children.

These findings refute the idea that mood problems in ADHD are necessarily part of an undetected depression — even though they do indicate higher future risk for depression as well as higher possibility of depression being present.

Anger Issues: DMDD, Bipolar Disorder & ADHD

ADHD, DMDD, and bipolar disorder are all associated in different ways with anger and irritability. Understanding how they relate (and don’t) is critical to ensuring proper diagnosis and targeted treatment for anger issues in patients.

Anger Issues and Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD)

DMDD is a new disorder in the DSM-5 primarily characterized by:

- Severe tantrums, either verbal or behavioral, that are grossly out of proportion to the situation

- A baseline mood of persistent grumpiness, irritability, and/or anger

DMDD was established in DSM-5 after a crisis in child mental health in the 1990s in which rates of bipolar disorder diagnoses and associated treatment with psychotropic mediation in children skyrocketed – inaccurately. Clinicians at that time assumed, in error, that irritability in children could be substituted for actual mania, a symptom of bipolar disorder. We now know from further epidemiological work that, in the absence of mania, irritability is not a symptom of hidden bipolar disorder in children. When mania is present, irritability can also emerge as a side feature of the mania. But mania is the primary feature of bipolar disorder.

Clinicians at that time assumed, in error, that irritability in children could be substituted for actual mania, a symptom of bipolar disorder. We now know from further epidemiological work that, in the absence of mania, irritability is not a symptom of hidden bipolar disorder in children. When mania is present, irritability can also emerge as a side feature of the mania. But mania is the primary feature of bipolar disorder.

Mania means a notable change from normal in which a child (or adult) has unusually high energy, less need for sleep, and grandiose or elevated mood, sustained for at least a couple of days — not just a few hours. True bipolar disorder remains very rare in pre-adolescent children. The average age of onset for bipolar disorder is 18 to 20 years.

Thus, DMDD was created to give a place for children older than 6 years of age with severe, chronic temper tantrums who also do not have elevated risk for bipolar disorder in their family or in the long run. It opens the door for research on new treatments targeted these children, most of whom meet criteria for severe ADHD, often with associated oppositional defiant disorder.

DMDD is also somewhat similar to intermittent explosive disorder (IED). The difference is that a baseline negative mood is absent in the latter. IED is also usually reserved for adults.

As far as ADHD, it is important to recognize that most patients who meet criteria for DMDD actually have severe ADHD, sometimes with comorbid anxiety disorder or ODD. This diagnosis, however, is given to help avoid a bipolar disorder diagnosis and take advantage of new treatment insights.

[Self-Test: Could Your Child Have DMDD?]

Anger Issues and ADHD: Treatment Approaches

Most treatment studies for ADHD look at how core symptoms of ADHD change. Treating anger problems in individuals with ADHD has only recently become a major research focus, with useful insights revealed for patient care. Alternative and experimental approaches are also increasingly showing promise for patients with emotional dysregulation and anger issues.

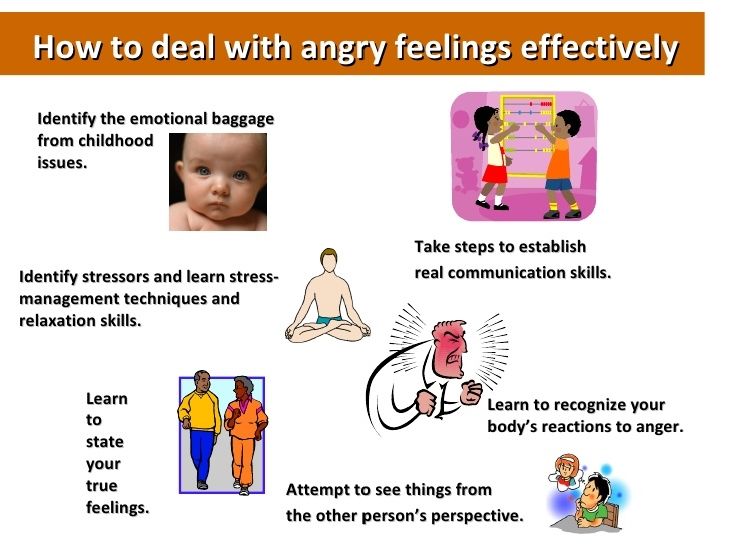

Interventions for Children with Anger Issues

1.

Behavioral Therapy4

Behavioral Therapy4- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Some children with anger issues have a tendency to over-perceive threat – they over-react to an unclear or ambiguous situation (someone accidentally bumps you in line) when no threat is actually present. For these children, CBT can help the child with understanding that something ambiguous isn’t necessarily threatening.

- Counseling: Anger problems can also be caused by difficulties with tolerating frustration. Counseling can help children learn how to tolerate normal frustrations and develop better coping mechanisms.

- Parent Counseling: Parents have a role in how a child’s anger manifests. A parent’s angry reaction can lead to negative and mutual escalation, such that parents and kids both start to lose their balance. This can form a negative loop. With counseling, parents can learn to react differently to their child’s tantrums, which can help reduce them over time.

2. Medication:

Regular stimulant medication for ADHD helps ADHD symptoms much of the time, but is only about half as helpful with anger problems. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) may be next for treating severe anger problems. A recent double-blind study, for example found that children with severe tantrums, DMDD, and ADHD who were on stimulants saw a reduction in irritability and tantrums only after being given Citalopram (Celexa, an SSRI antidepressant) as a second medication5. While only one study, these findings do suggest that when mainline stimulant medications are not working, and severe anger problems are a core issue, then adding an SSRI may be a reasonable step.

Interventions for Adults with Anger Issues

Behavioral counseling (as in CBT) has clear evidence pointing to its benefits in treating emotional regulation problems for adults with ADHD. Specifically, these therapies improve skills in the following:

- Interior regulation: refers to what individuals can do within themselves to manage out-of-control anger.

The key element here is learning coping skills, practicing them, and checking back with a counselor for refining. Important for patients to understand is that learning about coping skills without practice, or trying some self-help without professional consultation is generally not as effective. Some examples of coping skills include:

The key element here is learning coping skills, practicing them, and checking back with a counselor for refining. Important for patients to understand is that learning about coping skills without practice, or trying some self-help without professional consultation is generally not as effective. Some examples of coping skills include: - anticipatory coping, or devising an exit plan to the triggering situation – “I know I’m going to get angry next time this happens. What am I going to plan ahead of time to avoid that situation?”

- appraisals and self-talk to keep temper under control (“Maybe that was an accident, or they’re having a bad day.”)

- shifting attention to focus elsewhere instead of on the upsetting situation.

- Exterior supports

- Social connections – talking to others and having their support –are tremendously beneficial for adults struggling with ADHD and anger

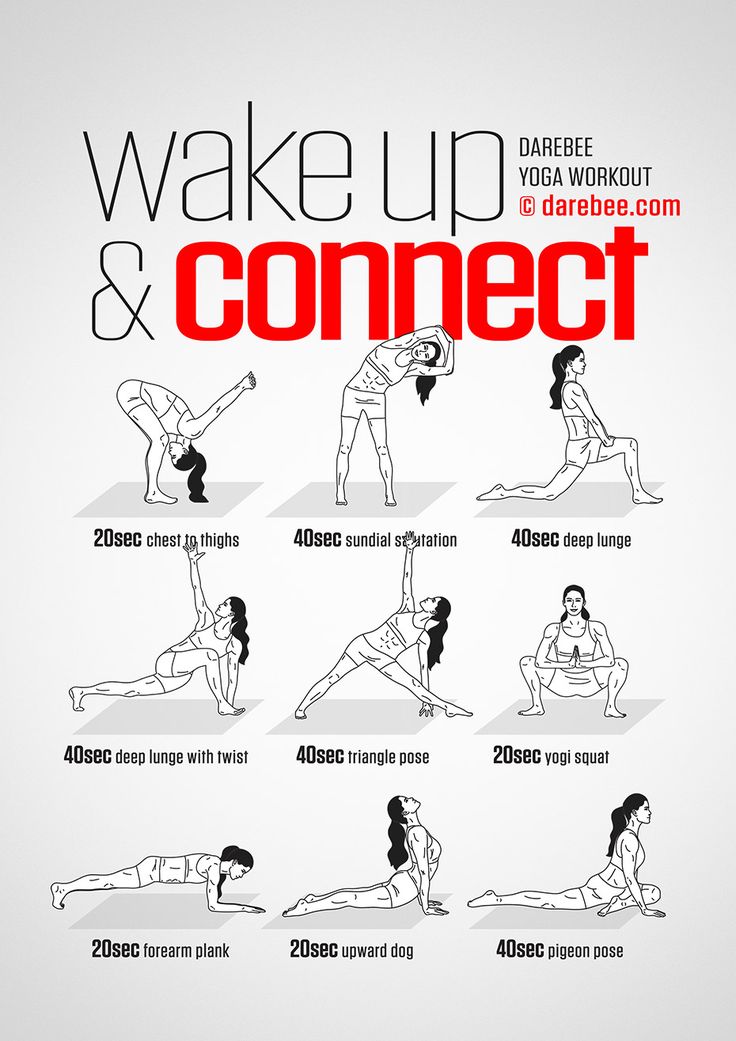

- Exercise, stress reduction, and other self-care strategies can help.

Strategies with Limited Benefits

- Typical ADHD medication helps with core symptoms, but has only modest benefits on emotional dysregulation for adults with ADHD6

- Meditation classes offer some benefits7 for managing ADHD symptoms and emotional dysregulation for teens and adults (and for children if parents join in the practice too), but most studies on this intervention tend to be of low quality so it is difficult to draw strong conclusions.

- High-dose micronutrients may help adults with ADHD emotionality, based on a small but robust study8. Omega-3 supplementation also appears to have a small effect in bettering emotional control in children with ADHD9.

Problems with emotional dysregulation, in particular with anger reactivity, are very common in people with ADHD. You are not alone in struggling in this area. Anger may indicate an associated mood problem but often is just part of the ADHD. Either way, changes in traditional ADHD treatment can be very helpful.

Either way, changes in traditional ADHD treatment can be very helpful.

Anger Issues and ADHD: Next Steps

- Read: Why Is My Child So Angry?!

- Learn: Mapping the ADHD Brain – MRI Scans May Unlock Better Treatment and Even Symptom Prevention

- For Clinicians: Comorbid Considerations Q&A – Treating Bipolar Disorder, Depression, Anxiety, or Autism Alongside ADHD

The content for this webinar was derived from the ADDitude Expert Webinar “You’re So Emotional: Why ADHD Brains Wrestle with Emotional Regulation” by Joel Nigg, Ph.D., which was broadcast live on July 28, 2020.

SUPPORT ADDITUDE

Thank you for reading ADDitude. To support our mission of providing ADHD education and support, please consider subscribing. Your readership and support help make our content and outreach possible. Thank you.

View Article Sources

1 Beheshti, A. , Chavanon, M. & Christiansen, H. (2020). Emotion dysregulation in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 20, 120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-2442-7

, Chavanon, M. & Christiansen, H. (2020). Emotion dysregulation in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 20, 120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-2442-7

2 Karalunas, S. L., Gustafsson, H. C., Fair, D., Musser, E. D., & Nigg, J. T. (2019). Do we need an irritable subtype of ADHD? Replication and extension of a promising temperament profile approach to ADHD subtyping. Psychological Assessment, 31(2), 236–247. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000664

3 Nigg, J., et. al. (2019). Evaluating chronic emotional dysregulation and irritability in relation to ADHD and depression genetic risk in children with ADHD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 61, 2. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13132

4 Stringaris, A., Vidal-Ribas, P., et. al. (2017). Practitioner Review: Definition, recognition, and treatment challenges of irritability in young people. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59 (7). https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12823

https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12823

5 Towbin, K., Vidal-Ribas, P., et. al. (2020). A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial of Citalopram Adjunctive to Stimulant Medication in Youth With Chronic Severe Irritability. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2019.05.015

6 Lenzi, F., Cortese, S. et. al. (2018). Pharmacotherapy of emotional dysregulation in adults with ADHD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 84, 359-367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.08.010

7 Xue, J et. al. (2019). A meta-analytic investigation of the impact of mindfulness-based interventions on ADHD symptoms. Medicine 98(23). 10.1097/MD.0000000000015957

8 Rucklidge, J., Frampton, C., Gorman, B., & Boggis, A. (2014). Vitamin–mineral treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults: Double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 204(4), 306-315. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.113.132126

British Journal of Psychiatry, 204(4), 306-315. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.113.132126

9 Cooper, R., Tye, C. et.al. (2016). The effect of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation on emotional dysregulation, oppositional behaviour and conduct problems in ADHD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 190, 474-482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.053

Previous Article Next Article

a new look at emotional dysregulation and treatment recommendations

People with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder often experience emotions with greater intensity than people who do not have this disorder. Moreover, comorbid conditions such as impulsive aggression and oppositional defiant disorder, as well as the side effects of medications, can make a person more likely to feel short-tempered, aggressive, impatient, and angry.

Natalya Chebakova

legion-media

Irritability, anger and emotional dysregulation in general have a strong impact on the psychosocial well-being of children and adults with attention deficit disorder (ADHD). Recent studies show that these problems may require special treatment. What is ADHD? It manifests itself with symptoms such as difficulty concentrating, hyperactivity, and poorly controlled impulsivity. nine0003

What is anger

Anger is an emotion, often of an aggressive nature, directed towards something or someone with the aim of destroying, suppressing, subjugating (often inanimate objects). Often the reaction of this negative emotion is short-lived.

Anger can literally burst a person from the inside. During an emotional outburst, a person’s facial muscles tense up, the body becomes like a stretched string, teeth and fists clench, the face begins to burn, there is a feeling that something is “boiling” inside, while there is no control over the mind. nine0003

nine0003

What is emotional dysregulation

Emotional dysregulation is the inability, even with considerable effort, to effectively influence and manage one's emotional experiences (anger, guilt, shame, rage, resentment), actions, verbal and non-verbal reactions and manage them. Emotional dysregulation manifests itself in many different life situations and leads to suffering and maladjustment of a person.

Ultimately, emotional dysregulation is one of the main reasons why ADHD is subjectively difficult to treat and why this disorder leads to a high risk of other problems such as depression, bipolar disorder, and anxiety disorders. nine0003

In general, attention to anger and emotionality issues in ADHD patients is critical to successful treatment and symptom management in the long term.

Anger problems and ADHD

Emotional dysregulation and anger have been associated with ADHD since the mid-20th century, before modern diagnostic standards were established.

The most important aspect to consider is the nature of ADHD as a disorder of self-regulation of behavior, attention and emotions. In other words, any difficulty in regulating our thoughts, emotions, and actions—which is characteristic of ADHD—may explain the irritability, tantrums, and anger regulation problems that these people experience. nine0003

About 70% of adults with ADHD report problems with emotional dysregulation, and among children with ADHD this rises to 80%.

These problems include:

- Irritability: anger dysregulation problems - episodes of "tantrums" and chronic or generally negative feelings between episodes.

- Lability: frequent, reactive mood swings during the day.

- Recognition is the ability to accurately recognize the feelings of others. People with ADHD may tend not to notice other people's emotions until they are pointed out.

nine0052

nine0052 - Affective intensity: people with ADHD tend to experience emotions very strongly.

- Emotional dysregulation: inability to control emotions.

The genetic basis of ADHD and anger

From a genetic point of view, emotional dysregulation is closely related to ADHD. Such people often have irritability, anger, tantrums, and excessive pursuit of sensations, and more often than excessive impulsivity and arousal.

Anger problems and destructive mood dysregulation disorder

What is Destructive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD)

DMDD is a psychiatric disorder predominantly found in children and adolescents characterized by persistent irritable moods and frequent outbursts of anger that are disproportionate to the situation and significantly more severe than typical human responses the same age. Symptoms of ADHD resemble those of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), anxiety disorders, and bipolar disorder. nine0003

nine0003

Characteristics of ADDD

- Severe and recurring temper tantrums three or more times per week. These outbursts can be verbal or behavioral. Verbal outbursts are often described by observers as rage, fits, or tantrums. Children may scream, yell and cry for excessively long periods of time, sometimes without much provocation. Physical flashes can be directed at people or property. Children can throw objects; hitting, spanking or biting others; destroy toys or furniture; or otherwise act in a harmful or destructive manner. nine0052

- Constant irritable or angry mood. Parents, teachers, and classmates describe these children as usually angry, resentful, grumpy, or easily excitable. Unlike irritability, which can be a symptom of other disorders such as ODD, anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder, irritability and anger in children with DDDD is not episodic or situational. They are very pronounced and appear most of the day, almost every day in various conditions, and continue for one or several years.

nine0052

nine0052

Problems with anger and bipolar disorder

What is bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder (previously manic -depressive psychosis) -endogenous mental disorder, manifested in the form of affective conditions: manic and depressive, and nervous state . Bipolar disorder is highly genetic and usually presents in late adolescence or early adulthood. The average age of onset of bipolar disorder is 18 to 20 years. nine0003

Mania means a marked change from normal in which a child or adult has an unusually high level of energy, less need for sleep, and an elated mood that lasts for at least a couple of days.

ADHD, ADHD, and bipolar disorder are all associated with anger and irritability in different ways. Understanding how they are related (and not related) is critical to ensuring proper diagnosis and targeted treatment of anger problems in patients. nine0003

Anger and ADHD Treatment Approaches

Behavior Therapy

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

when in fact there is no threat (for example, someone accidentally pushed in line). For such people, cognitive behavioral therapy helps them understand that something ambiguous is not necessarily a threat. nine0003

For such people, cognitive behavioral therapy helps them understand that something ambiguous is not necessarily a threat. nine0003

Internal regulation

Refers to what people can do to themselves to deal with uncontrollable anger. The key element here is the study of coping skills, their development and discussion with a specialist.

Here are some examples of coping skills:

- coping proactively or developing a plan to get out of a trigger situation: “I know that the next time this happens, I will be angry. What should I do to avoid this situation?” nine0052

- self-assessment and self-talk to keep yourself in check: "It was an accident" or "This person is just having a bad day and I don't react to it";

- shifting attention to something other than the upsetting situation.

Patient Counseling

Problems with anger can also be caused by difficulties with the transfer of frustration - this is a typical reaction to disappointment, the unfulfillment of hopes, the impossibility of self-realization. Counseling can help people with ADHD learn to tolerate common frustrations and develop better coping mechanisms. nine0003

Counseling can help people with ADHD learn to tolerate common frustrations and develop better coping mechanisms. nine0003

Parent counseling

Parents of children with ADHD play a role in the child's anger. An angry reaction from parents can lead to a negative and mutual escalation, so that both parents and children begin to lose control of their emotions. By consulting with specialists, parents can learn how to respond differently to their child's tantrums, which will help reduce them over time.

Medications

Typical ADHD medications help with major symptoms but have modest results for anger problems. nine0003

Vitamins, minerals and trace elements

High doses of micronutrients can help adults with emotional attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Omega-3 supplementation has been shown to improve emotional control in children with ADHD.

youtube

Click and watch

Do you often get angry?

Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Epidemiology, Comorbidity and Diagnosis

nine0002 Elis Charach, MSc, MD

Hospital for Sick Children, Canada

(English). Translation: November 2015 PDF Document

Epidemiology of ADHD

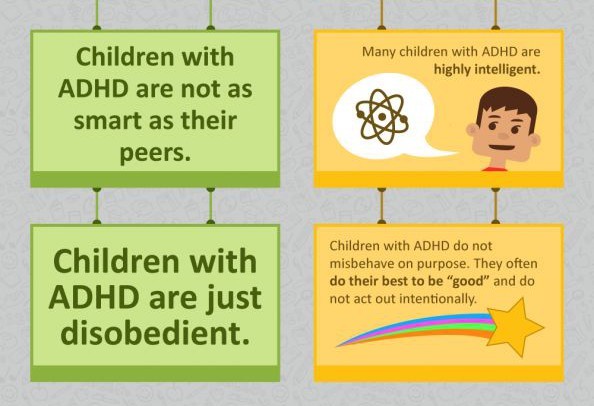

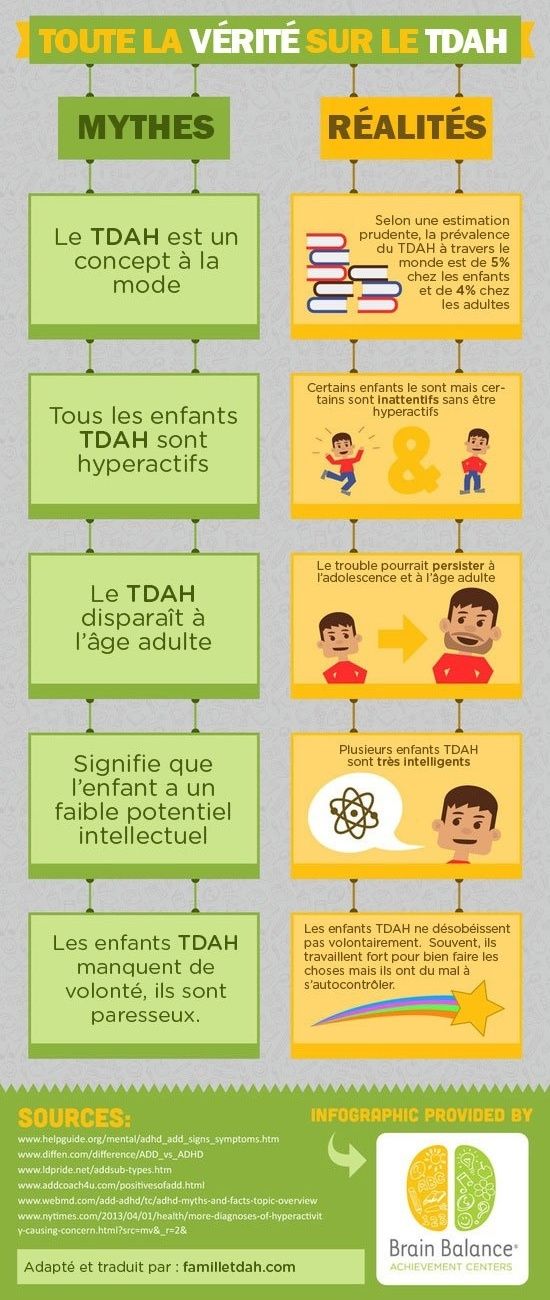

Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), which is characterized by age-appropriate levels of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity, are most often identified and treated in primary school. Studies around the world have identified an ADHD prevalence rate equivalent to 5. 29% (95% CI: 5.01-5.56) among children and adolescents. 1 Rates are higher for boys than for girls and for children under 12 years of age compared to adolescents. nine0178 1.2 Estimates of prevalence depend on the method of determination, the diagnostic criteria used, and whether criteria for assessing functional disorders are included. 1 In general, rates are almost the same across countries, with the exception of countries in Africa and the Middle East, where prevalence rates are lower than in North America and Europe. 1

29% (95% CI: 5.01-5.56) among children and adolescents. 1 Rates are higher for boys than for girls and for children under 12 years of age compared to adolescents. nine0178 1.2 Estimates of prevalence depend on the method of determination, the diagnostic criteria used, and whether criteria for assessing functional disorders are included. 1 In general, rates are almost the same across countries, with the exception of countries in Africa and the Middle East, where prevalence rates are lower than in North America and Europe. 1

Typically, symptoms cause functional difficulties with behavior and schoolwork, and often disrupt family and peer relationships. nine0178 3.4 Children with ADHD are more likely to seek health care services and have a higher percentage of injuries compared to children without the condition. 5.6 While symptoms of hyperactivity decrease during adolescence, most children with ADHD continue to show some cognitive impairment (eg, executive function deficits, working memory impairment) compared to their peers in adolescence and adulthood. 7.8 Research has found lower high school completion rates, earlier initiation of alcohol and illegal substance use, higher rates of cigarette smoking and car accidents among adolescents with ADHD. nine0178 9-14 Hyperactivity in childhood is also associated with the subsequent occurrence of other psychiatric disorders, including anxiety, behavioral disorders, affective disorders, suicidal behavior and antisocial personality disorder. 13.15-18 Adults with a childhood history of ADHD have higher than expected rates of injuries and accidents, marital and work difficulties, teenage pregnancies, and children born out of wedlock. 15,17,19-21 ADHD is an important public health issue, not only because of the long-term hardship experienced by individuals and families, but also because of the heavy burden placed on the education, health care, and criminal justice systems. 22-24

7.8 Research has found lower high school completion rates, earlier initiation of alcohol and illegal substance use, higher rates of cigarette smoking and car accidents among adolescents with ADHD. nine0178 9-14 Hyperactivity in childhood is also associated with the subsequent occurrence of other psychiatric disorders, including anxiety, behavioral disorders, affective disorders, suicidal behavior and antisocial personality disorder. 13.15-18 Adults with a childhood history of ADHD have higher than expected rates of injuries and accidents, marital and work difficulties, teenage pregnancies, and children born out of wedlock. 15,17,19-21 ADHD is an important public health issue, not only because of the long-term hardship experienced by individuals and families, but also because of the heavy burden placed on the education, health care, and criminal justice systems. 22-24

Population studies have found that child inattention and hyperactivity are more common in single-parent families, as well as in families with low parental education, parental unemployment and low income. nine0178 17,25,26 Data from family studies suggest that ADHD symptoms are highly heritable, 27 however, early environmental factors also play a role. Smoking and maternal alcohol consumption in the prenatal (antenatal) period, low birth weight, and developmental problems are associated with high levels of inattention and hyperactivity. 26.28 More recently, a review of longitudinal data from The Canadian National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth found that approximately 7% of children show sustained high levels of parental inherited hyperactivity from two years of age to the first grades of primary schools. nine0178 29 Maternal smoking during the prenatal period, maternal depression, poor parenting practices, and living in a disadvantaged neighborhood in the early years are all associated with later childhood behavioral problems, including inattention and hyperactivity 4 years later. 29-31

nine0178 17,25,26 Data from family studies suggest that ADHD symptoms are highly heritable, 27 however, early environmental factors also play a role. Smoking and maternal alcohol consumption in the prenatal (antenatal) period, low birth weight, and developmental problems are associated with high levels of inattention and hyperactivity. 26.28 More recently, a review of longitudinal data from The Canadian National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth found that approximately 7% of children show sustained high levels of parental inherited hyperactivity from two years of age to the first grades of primary schools. nine0178 29 Maternal smoking during the prenatal period, maternal depression, poor parenting practices, and living in a disadvantaged neighborhood in the early years are all associated with later childhood behavioral problems, including inattention and hyperactivity 4 years later. 29-31

Clinical detection and treatment of ADHD in North America may vary geographically, presumably reflecting differences in community practices or access to services. 32-34 Treatment of symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity with stimulant drugs increased in frequency from early to mid 1990s and likely reflects longer periods of use with continued treatment into adolescence, as well as an increase in the number of girls diagnosed and treated for the disease. 35-38

32-34 Treatment of symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity with stimulant drugs increased in frequency from early to mid 1990s and likely reflects longer periods of use with continued treatment into adolescence, as well as an increase in the number of girls diagnosed and treated for the disease. 35-38

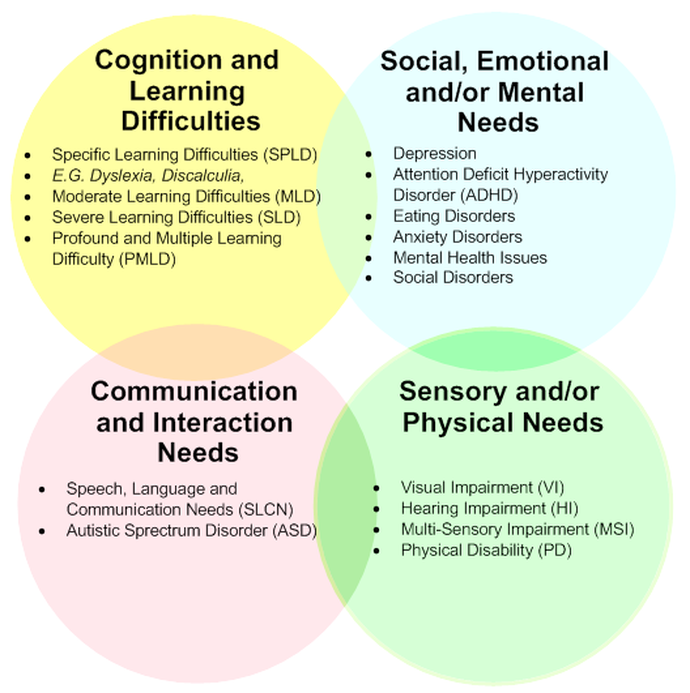

Comorbid (or comorbid) disorders

Half to two-thirds of children diagnosed with ADHD also have comorbid psychiatric and developmental disorders, including rebelliousness and aggressive behavior, anxiety, low self-esteem, tic disorders, disorders motility, learning disabilities and speech disorders. nine0178 39-46 Sleep problems, including enuresis (bedwetting), are common, along with disturbed sleep breathing, which is a potentially modifiable cause for increased inattention. 47.48 The global decline in well-being in children with ADHD increases with the number of comorbidities. 13.49 Concomitant diagnoses also increase the likelihood of additional difficulties for children as they progress into adolescence and adulthood. nine0178 10,15,16,50-55

nine0178 10,15,16,50-55

Neurocognitive difficulties are an important source of deterioration in well-being in children with ADHD. Areas of executive functioning and working memory, as well as specific speech and learning disorders, are common in the clinical group. 56.57-64 Approximately one third of children referred for psychiatric, often behavioral, problems may have previously undiagnosed speech problems. 65 Potential cognitive problems should be diagnosed whenever possible to ensure appropriate correction in educational settings. nine0003

ADHD in preschool children

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) usually begins before the child enters school. However, in preschool children, ADHD is characterized not only by attention deficits, excessive impulsivity, and hyperactivity, but is often accompanied by violent outbursts of anger, demanding, confrontational behavior, and aggressiveness, which can interfere with attendance at daycare centers or lead to avoidance of family gatherings, and also represent a heavy burden of care for the family and contribute to distress. nine0178 66,67,68 These disruptive behaviors are often a concern for parents, many of which are 66 diagnosed as oppositional defiant disorder. Early identification of the disorder can be helpful in addressing a number of developmental issues that children with ADHD may have.

nine0178 66,67,68 These disruptive behaviors are often a concern for parents, many of which are 66 diagnosed as oppositional defiant disorder. Early identification of the disorder can be helpful in addressing a number of developmental issues that children with ADHD may have.

Assessment of ADHD in school-age children

In elementary school, teachers often bring to the attention of parents their concerns about the learning style and behavioral difficulties of their children. Educators generally expect kindergarten and first grade children to be able to follow classroom routines, follow simple directions, play cooperatively with peers, and stay focused for 15 to 20 minutes during classwork. The issues raised by educators, especially experienced educators, are a source of important information about the child's academic and social functioning. nine0003

The formal diagnosis of ADHD reflects pervasive and damaging levels of inattention, distractibility, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. The child's symptoms should be beyond the normal age range and cause impairment of functioning, most commonly in academic or social skills, relationships with peers, and family. Difficulties are usually present in the preschool years, although they are not always diagnosed. The harassing behavior recurs in more than one context - in the family, at school, or in public places, such as on a trip to the park or at the grocery store. nine0003

The child's symptoms should be beyond the normal age range and cause impairment of functioning, most commonly in academic or social skills, relationships with peers, and family. Difficulties are usually present in the preschool years, although they are not always diagnosed. The harassing behavior recurs in more than one context - in the family, at school, or in public places, such as on a trip to the park or at the grocery store. nine0003

There are two sets of formal diagnostic rules used in Canada, DSM IV TR (Diagnostic and Stratistical Manual, Fourth Edition, Text Revised; Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Revised) and ICD-10 (International Classification of Disorders , Tenth Edition; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition). The DSM IV diagnosis of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) largely reflects the consensus understanding of the diagnosis in the United States. There are three types of ADHD (see Table 1 for diagnostic symptoms). nine0003

nine0003

Type I - predominantly inattentive type, the child exhibits 6 of the 9 symptoms of inattention described;

type II - predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type, the child has 6 out of 9 hyperactive-impulsive symptoms;

type III - combined type, where the child shows high levels of development of symptoms of both types (see diagnostic symptoms in Table 1).

The ICD-10 diagnosis of hyperkinetic disorder is most commonly used by physicians who practice outside of North America. The theoretical underpinnings of ADHD and hyperkinetic disorder overlap to a large extent: the MCD-10 diagnosis of hyperkinetic disorder covers a narrower group of children who must meet both criteria - both hyperactivity and inattention and distractibility. However, when considering aspects of the overall clinical picture, children with ADHD, especially of the combined type, show similar impairments in functioning and need intervention in the same way as children with hyperkinetic disorder. nine0178 69

nine0178 69

Clinical diagnosis of a child with ADHD is best done by professionals trained in child mental health and psychosocial development tests. Because young children often respond to stressful situations with increased levels of activity and distractibility, and have learning and social difficulties, identification of alternative explanations for these complicating symptoms requires diagnostic evaluation of the child's age, family, and social contexts. Physical symptoms such as poor sleep or chronic illness should also be considered as potential causes or contributing factors to a child's difficulty. Ideally, the doctor should obtain information about the child's social and school life from more than one informant who has the opportunity to observe him in various situations, for example, this may be the child's parent and his teacher. Self-report surveys of parents and educators are widely used to obtain information about the behavior of a particular child at home or in the school environment, respectively. nine0178 4 In addition, it is essential to conduct detailed clinical interviews with parents of young children and, for older children, with the child or adolescent himself. Reviewing school records over several years is also useful for getting a longitudinal view of a child from multiple educators. The identification of comorbid disorders is one of the important aspects of the diagnostic evaluation, including the learning and speech disorders discussed in the last section. In addition, psychosocial problems and age-related difficulties should be identified, as they can complicate the treatment of ADHD and affect the long-term prognosis. nine0003

nine0178 4 In addition, it is essential to conduct detailed clinical interviews with parents of young children and, for older children, with the child or adolescent himself. Reviewing school records over several years is also useful for getting a longitudinal view of a child from multiple educators. The identification of comorbid disorders is one of the important aspects of the diagnostic evaluation, including the learning and speech disorders discussed in the last section. In addition, psychosocial problems and age-related difficulties should be identified, as they can complicate the treatment of ADHD and affect the long-term prognosis. nine0003

Table 1: DSM IV TR Criteria for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

A. Choice of option (1) or (2):

(1) Six or more of the following symptoms persist during inattention6 months, are expressed to the degree of inadequacy and do not correspond to the age level:

Inattention

- often does not pay close attention to details or makes careless mistakes

- often has difficulty maintaining attention during tasks or play activities

- often the child does not seem to listen when spoken to directly

- often unable to follow directions and complete lessons, homework, or chores (not due to disobedience or inability to understand directions)

- often has difficulty organizing assignments and other activities

- often avoids, dislikes, or does not want to participate in tasks that require prolonged mental effort

- often loses items needed at school and at home (eg toys, school supplies, pencils, books, work tools)

- easily distracted by extraneous stimuli

- forgetful in everyday situations

(2) Six or more of the following symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity persist for 6 months, are expressed to the degree of inadequacy and do not correspond to the age norm:

Hyperactivity

- frequent restless movements in the hands and feet, fidgeting in a chair

- often gets up from his seat in the classroom during lessons or in other situations in which you need to stay in place.

- often runs or climbs things beyond measure in situations where this is unacceptable

- cannot play quietly and engage in leisure activities

- is often in constant motion or behaves as if "it has a motor attached to it"

- often talkative

Impulsivity

- often answers questions without thinking or listening to the end

- usually has difficulty waiting in line

- often interferes with or pesters others (for example, interferes in conversations or games)

B. Some symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity or inattention that worsen well-being were present in a child under the age of 7 years. nine0003

C. Problems associated with these symptoms occur in two or more areas of life (e.g., school and home)

D. There must be clear evidence of clinically significant impairment in social life, academic activities, or studies associated with acquiring a profession.

E. Symptoms do not completely overlap with pervasive developmental disorder, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorder, and cannot be explained by other mental disorders (eg, mood disorder, anxiety disorder, dissociative disorder, or personality disorder). nine0003

Literature

- Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry 2007;164(6):942-948.

- Waddell C, Offord DR, Shepherd CA, Hua JM, McEwan K. Child psychiatric epidemiology and Canadian public policy-making: the state of the science and the art of the possible. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2002;47(9):825-832.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder and Committee on Quality Improvement. Clinical practice guideline: treatment of the school-aged child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Pediatrics 2001;108(4):1033-1044.

Pediatrics 2001;108(4):1033-1044. - Pliszka S, AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. nine0289 Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2007;46(7):894-921.

- Bruce B, Kirkland S, Waschbusch D. The relationship between childhood behavioral disorders and unintentional injury events. Pediatrics & Child Health 2007;12(9):749-754.

- Leibson CL, Katusic SK, Barbaresi WJ, Ransom J, O'Brien PC. Use and costs of medical care for children and adolescents with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA-Journal of the American Medical Association 2001;285(1):60-66.

- Brassett-Harknett A, Butler N. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an overview of the etiology and a review of the literature relating to the correlates and lifecourse outcomes for men and women.

Clinical Psychology Review 2007;27(2):188-210.

Clinical Psychology Review 2007;27(2):188-210. - Spencer TJ, Biederman J, Mick E. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis, lifespan, comorbidities, and neurobiology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 2007;32(6):631-642.

- Barkley RA, Fischer M, Edelbrock C, Smallish L. The adolescent outcome of hyperactive children diagnosed by research criteria III. Mother-child interactions, family conflicts and maternal psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 1991;32(2):233-255.

- Barkley RA, Fischer M, Edelbrock CS, Smallish L. The adolescent outcome of hyperactive children diagnosed by research criteria: I. An 8-year prospective follow-up study. nine0289 Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1990;29(4):546-557.

- Biederman J, Faraone S, Milberger S, Guite J, Mick E, Chen L, Mennin D, Marrs A, Ouellette C, Moore P, Spencer T, Norman D, Wilens T, Kraus I, Perrin J. A prospective 4- year follow-up study of attention-deficit hyperactivity and related disorders.

Archives of General Psychiatry 1996;53(5):437-446.

Archives of General Psychiatry 1996;53(5):437-446. - Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Konig PH, Giampino TL. Hyperactive boys almost grown up. IV. Criminality and its relationship to psychiatric status. nine0289 Archives of General Psychiatry 1989;46(12):1073-1079.

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Early onset cannabis use and psychosocial adjustment in young adults. Addiction 1997;92(3):279-296.

- Barkley RA, Guevremont DC, Anastopoulos AD, DuPaul GJ, Shelton TL. Driving-related risks and outcomes of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adolescents and young adults: a 3- to 5-year follow-up survey. Pediatrics 1993;92(2):212-218. nine0051 Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Show me the child at seven: the consequences of conduct problems in childhood for psychosocial functioning in adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2005;46(8):837-849.

- Copeland WE, Miller-Johnson S, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello EJ.

Childhood psychiatric disorders and young adult crime: a prospective, population-based study. American Journal of Psychiatry 2007;164(11):1668-1675.

Childhood psychiatric disorders and young adult crime: a prospective, population-based study. American Journal of Psychiatry 2007;164(11):1668-1675. - Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Exposure to single parenthood in childhood and later mental health, educational, economic, and criminal behavior outcomes. nine0289 Archives of General Psychiatry 2007;64(9):1089-1095.

- Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Driving outcomes of young people with attentional difficulties in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2000;39(5):627-634.

- Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M. Adult outcome of hyperactive boys. Educational achievement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Archives of General Psychiatry 1993;50(7):565-576.

- Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M. Adult psychiatric status of hyperactive boys grown up. American Journal of Psychiatry 1998;155(4):493-498.

- Biederman J, Petty CR, Fried R, Kaiser R, Dolan CR, Schoenfeld S, Doyle AE, Seidman LJ, Faraone SV. Educational and occupational underattainment in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a controlled study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2008;69(8):1217-1222.

- Birnbaum HG, Kessler RC, Lowe SW, Secnik K, Greenberg PE, Leong SA, Swensen AR. Costs of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the US: excess costs of persons with ADHD and their family members in 2000. Current Medical Research & Opinion 2005;21(2):195-206.

- Leibson CL, Long KH. Economic implications of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder for healthcare systems. Pharmacoeconomics 2003;21(17):1239-1262. nine0051 Secnik K, Swensen A, Lage MJ. Comorbidities and costs of adult patients diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Pharmacoeconomics 2005;23(1):93-102.

- St Sauver JL, Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Jacobsen SJ.

Early life risk factors for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a population-based cohort study. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2004;79(9):1124-1131.

Early life risk factors for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a population-based cohort study. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2004;79(9):1124-1131. - Szatmari P, Offord DR, Boyle MH. Correlates, associated impairments and patterns of service utilization of children with attention deficit disorder: findings from the Ontario Child Health Study. nine0289 Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 1989;30(2):205-217.

- Faraone SV, Perlis RH, Doyle AE, Smoller JW, Goralnick JJ, Holmgren MA, Sklar P. Molecular genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry 2005;57(11):1313-1323.

- Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ, Horwood LJ. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and psychiatric adjustment in late adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry 1998;55(8):721-727. nine0051 Romano E, Tremblay RE, Farhat A, Cote S. Development and prediction of hyperactive symptoms from 2 to 7 years in a population-based sample.

- Elgar FJ, Curtis LJ, McGrath PJ, Waschbusch DA, Stewart SH. Antecedent-consequence conditions in maternal mood and child adjustment: a four-year cross-lagged study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 2003;32(3):362-374.

- Kohen DE, Brooks-Gunn J, Leventhal T, Hertzman C. Neighborhood income and physical and social disorder in Canada: associations with young children's competencies. nine0289 Child Development 2002;73(6):1844-1860.

- Brownell MD, Yogendran MS. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in Manitoba children: medical diagnosis and psychostimulant treatment rates. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2001;46(3):264-272.

- Rappley MD, Gardiner JC, Jetton JR, Houang RT. The use of methylphenidate in Michigan. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 1995;149(6):675-679.

- Jensen PS, Kettle L, Roper MT, Sloan MT, Dulcan MK, Hoven C, Bird HR, Bauermeister JJ, Payne JD.

Are stimulants overprescribed? Treatment of ADHD in four U.S. communities. nine0289 Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1999;38(7):797-804.

Are stimulants overprescribed? Treatment of ADHD in four U.S. communities. nine0289 Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1999;38(7):797-804. - Charach A, Cao H, Schachar R, To T. Correlates of methylphenidate use in Canadian children: a cross-sectional study. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2006;51(1):17-26.

- Miller AR, Lalonde CE, McGrail KM, Armstrong RW. Prescription of methylphenidate to children and youth, 1990-1996. CMAJ ̶ Canadian Medical Association Journal 2001;165(11):1489-1494.

- Robison LM, Sclar DA, Skaer TL, Galin RS. National trends in the prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and the prescribing of methylphenidate among school-age children: 1990-1995. Clinical Pediatrics 1999;38(4):209-217.

- Safer DJ, Zito JM, Fine EM. Increased methylphenidate usage for attention deficit disorder in the 1990s. Pediatrics 1996;98(6 Pt 1):1084-1088.

- Fliers E, Vermeulen S, Rijsdijk F, Altink M, Buschgens C, Rommelse N, Faraone S, Sergeant J, Buitelaar J, Franke B. ADHD and Poor Motor Performance From a Family Genetic Perspective. nine0289 Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2009;48(1):25-34.

- Drabick D, Gadow K, Sprafkin J. Co-occurrence of conduct disorder and depression in a clinic-based sample of boys with ADHD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2006;47(8):766-774.

- Baeyens D, Roeyers H, Van Erdeghem S, Hoebeke P, Vande Walle J. The prevalence of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder in children with nonmonosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis: a 4-year followup study. nine0289 Journal of Urology 2007;178(6):2616-2620.

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 1999;40(1):57-87.

- Corkum P, Moldofsky H, Hogg-Johnson S, Humphries T, Tannock R. Sleep problems in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: impact of subtype, comorbidity, and stimulant medication.

Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1999;38(10):1285-1293.

Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1999;38(10):1285-1293. - Kadesjo B, Gillberg C. The comorbidity of ADHD in the general population of Swedish school-age children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2001;42(4):487-492.

- Shreeram S, He JP, Kalaydjian A, Brothers S, Merikangas KR. Prevalence of enuresis and its association with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among U.S. children: results from a nationally representative study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2009;48(1):35-41.

- Biederman J, Newcorn J, Sprich S. Comorbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with conduct, depressive, anxiety, and other disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 1991;148(5):564-77.

- Corkum P, Tannock R, Moldofsky H. Sleep disturbances in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1998;37(6):637-646.

- Owens JA, Maxim R, Nobile C, McGuinn M, Msall M. Parental and self-report of sleep in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. nine0289 Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 2000;154(6):549-555.

- Biederman J, Milberger S, Faraone SV, Kiely K, Guite J, Mick E, Ablon JS, Warburton R, Reed E, Davis SG. Impact of adversity on functioning and comorbidity in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1995;34(11):1495-1503.

- Fischer M, Barkley RA, Edelbrock CS, Smallish L. The adolescent outcome of hyperactive children diagnosed by research criteria: II. Academic, attentional, and neuropsychological status. nine0289 Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology 1990;58(5):580-588.

- Fischer M, Barkley RA, Fletcher KE, Smallish L. The adolescent outcome of hyperactive children: predictors of psychiatric, academic, social, and emotional adjustment.

Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1993;32(2):324-332.

Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1993;32(2):324-332. - Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Early conduct problems and later life opportunities. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 1998;39(8):1097-1108.

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. The effects of unemployment on psychiatric illness during young adulthood. Psychological Medicine 1997;27(2):371-381.

- Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Mick E, Spencer T, Wilens TE, Klein KL, Price JE, Faraone SV. Psychopathology in females with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a controlled, five-year prospective study. Biological Psychiatry 2006;60(10):1098-1105. nine0051 Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Federman E, Angold A. Development of psychiatric comorbidity with substance abuse in adolescents: effects of timing and sex. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 1999;28(3):298-311.

- Solanto MV, Gilbert SN, Raj A, Zhu J, Pope-Boyd S, Stepak B, Vail L, Newcorn JH.

Neurocognitive functioning in AD/HD, predominantly inattentive and combined subtypes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2007;35(5):729-744.

Neurocognitive functioning in AD/HD, predominantly inattentive and combined subtypes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2007;35(5):729-744. - Hinshaw SP, Carte ET, Fan C, Jassy JS, Owens EB. Neuropsychological functioning of girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder followed prospectively into adolescence: evidence for continuing deficits? nine0289 Neuropsychology 2007;21(2):263-273.

- Thorell LB, Wahlstedt C. Executive functioning deficits in relation to symptoms of ADHD and/or ODD in preschool children. Infant and Child Development 2006;15(5):503-518.

- Loo SK, Humphrey LA, Tapio T, Moilanen IK, McGough JJ, McCracken JT, Yang MH, Dang J, Taanila A, Ebeling H, Jarvelin MR, Smalley SL.. Executive functioning among Finnish adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder . Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2007;46(12):1594-1604.

- Barkley RA, Edwards G, Laneri M, Fletcher K, Metevia L.

Executive functioning, temporal discounting, and sense of time in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD). Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2001;29(6):541-556.

Executive functioning, temporal discounting, and sense of time in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD). Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2001;29(6):541-556. - Beitchman JH, Brownlie EB, Inglis A, Wild J, Ferguson B, Schachter D, Lancee W, Wilson B, Mathews R. Seven-year follow-up of speech/language impaired and control children: psychiatric outcome. nine0289 Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 1996;37(8):961-970.

- Clark C, Prior M, Kinsella G. The relationship between executive function abilities, adaptive behavior, and academic achievement in children with externalising behavior problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2002;43(6):785-796.

- Calhoun SL, Dickerson Mayes S. Processing speed in children with clinical disorders. Psychology in the Schools 2005; 42(4):333-343 .

- Rabiner D, Coie JD, Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group.

Early attention problems and children's reading achievement: a longitudinal investigation. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2000;39(7):859-867.

Early attention problems and children's reading achievement: a longitudinal investigation. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2000;39(7):859-867. - Cohen NJ, Davine M, Horodezky N, Lipsett L, Isaacson L. Unsuspected language impairment in psychiatrically disturbed children: prevalence and language and behavioral characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1993;32(3):595-603.

- Cunningham CE, Boyle MH. Preschoolers at risk for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder: family, parenting, and behavioral correlates. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2002;30(6):555-569.

- Keown LJ, Woodward LJ. Early parent-child relations and family functioning of preschool boys with pervasive hyperactivity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2002;30(6):541-553. nine0051 Greenhill LL, Posner K, Vaughan BS, Kratochvil CJ. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in preschool children.

Pediatrics 2006;117(6):2101-2110.

Pediatrics 2006;117(6):2101-2110.