Mothers with bipolar

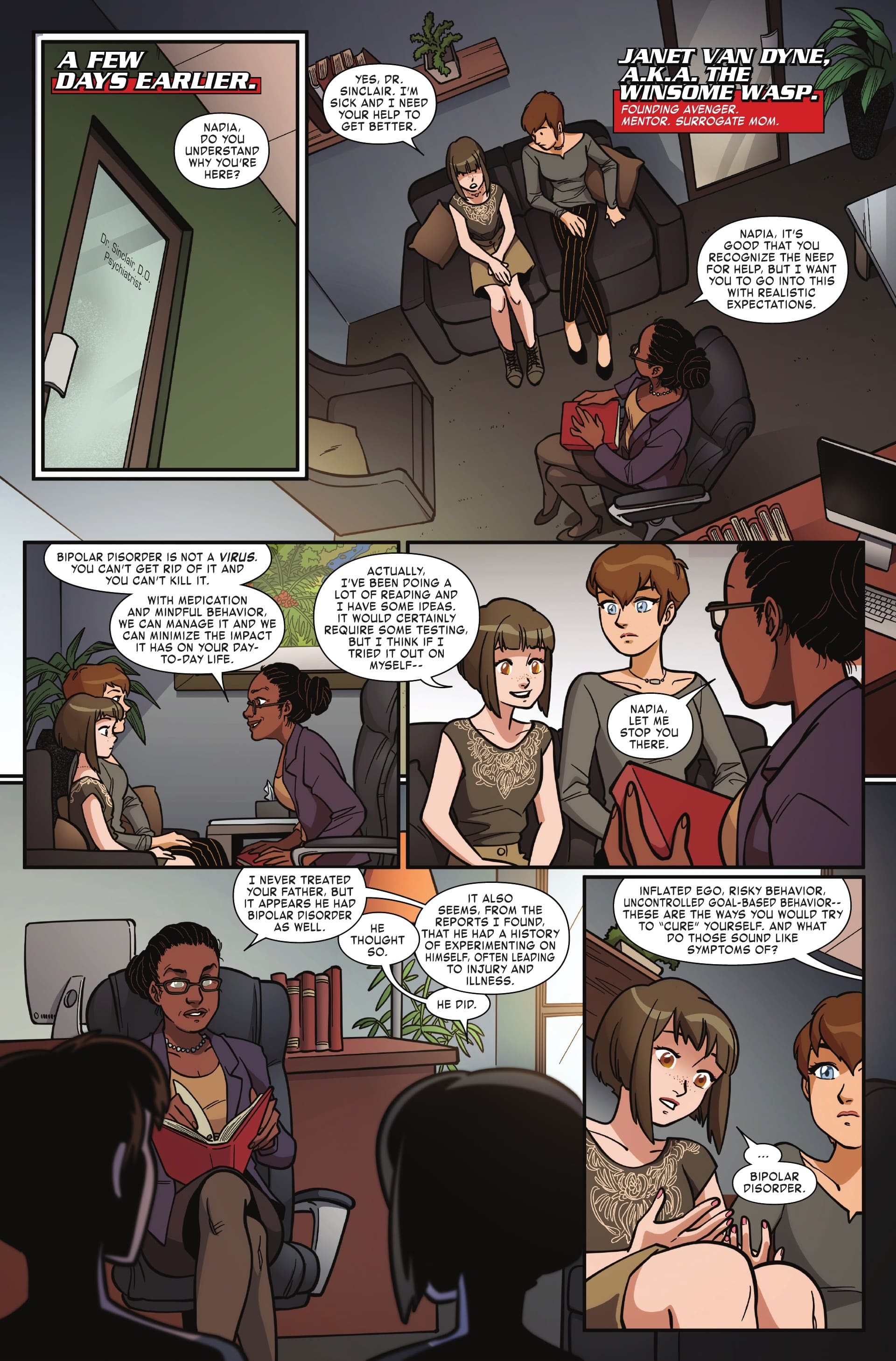

When a parent has bipolar disorder - What kids want to know

The Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) is conducting repairs to the streetcar tracks, streetcar platforms and bike lanes along College Street. The repairs are expected to start on September 5, 2022 and end in December 2022.

Learn more

If you are in an emergency, in crisis or need someone to talk to, there is help.

View Crisis Resouces

Skip to content

Search results for...What kids want to know

Children have a lot of questions when someone in their family is sick. When children don’t have answers to their questions, they tend to come up with their own, which can be incorrect and scary!

When the family member’s illness is bipolar disorder, it often becomes a secret that nobody talks about. All children need some explanation and support, geared to their age, to help them understand bipolar disorder.

Each parent and child’s “beginning conversation” about bipolar disorder will be different depending on the child’s age and ability to manage the information. You know your children best.

This brochure will help prepare you (whether you are the well parent, the parent with bipolar disorder, a grandparent or another adult in the child’s life) to take the first step. If you have already started talking to a child about bipolar disorder, this brochure will give you more information to keep the conversation going. It lists common questions children have about their parent’s bipolar disorder, as well as suggestions for how to answer their questions.

Questions kids have

What is bipolar disorder? How does bipolar disorder work?

- Bipolar disorder is an illness that affects how a person feels, thinks and acts. It is a sickness in the brain.

- When people have bipolar disorder, their brain works differently from the usual way. Our brains help us to think, feel and act in certain ways. When people have bipolar disorder, they think, feel and act differently from how they do when they’re well.

- There is almost always two different phases with bipolar disorder — lows called depression and highs called mania. During a low phase, the person is sad and often withdrawn. This is called depression. During a high phase, the person is either way too happy or way too angry. The person is very energetic and more outgoing than usual. This is called mania. At other times, the person is his or her usual self.

- Having bipolar disorder is not a weakness.

- Bipolar disorder can vary from person to person — it can be mild, or it can be a more difficult struggle.

Why does my dad act the way he does? How does it feel to have bipolar disorder? What goes on in my mom’s head when she’s not herself?

- Bipolar disorder causes people to act in ways that are different from how they usually act.

- Bipolar disorder is what causes the mood changes. The moods go in cycles.

- One parent said, “It was very hard because when I was high, I felt I could do anything. I didn't sleep or eat properly, and spent money excessively. The lows were very debilitating; I couldn't get out of bed, lost all interest in my work, in myself, my hobbies and my friends. The depression is the hard part. It makes it difficult to get out of bed.”

What does a “low mood,” or depression, mean? What does it look like?

- When people have low moods, they may be sad and cry a lot. They might also feel impatient and irritable and get more angry than usual.

- A parent in a low mood might not want to do things with the family like playing, talking or driving them places.

- They may get tired more easily and spend a lot of time in bed.

- Sometimes the low moods make them have trouble concentrating or thinking.

- The low moods may make them worry a lot more than usual.

- Their thinking may seem strange.

- They might have a bad attitude about life, or not think highly of themselves.

What does a “high mood”, or mania, mean? What does it look like?

- When people have high moods, they may feel like they are on top of the world, that they have “super powers” and can do anything. One parent described it as feeling really, really excited about something all of the time.

- They might spend more money, dress or act differently and say unusual things.

- However, high moods can also make them feel impatient and angrier.

- They might talk really fast, make quick decisions and seem distracted.

- They might not want to sleep as much and may stay awake longer.

How will bipolar disorder affect me? How will it affect my family?

- Bipolar disorder can affect the person with the illness, as well as other family members, in many different ways.

(*This would be an opportunity for the parent to discuss his or her own symptoms with the child.)

(*This would be an opportunity for the parent to discuss his or her own symptoms with the child.) - It can be very hard living with a parent who has bipolar disorder because that person may do or say things that make children feel bad, scared, sad, angry and often confused. This can happen when the parent is in a high or low mood. Sometimes it can feel like a parent with mood swings thinks mostly about him- or herself and doesn’t care much about what the kids think and feel.

- Bipolar disorder can make people feel ashamed so they don’t always want to talk about it.

- Remember that people with bipolar disorder will have their usual moods between the high and low moods. As the high or low mood improves, the person slowly starts acting more like him- or herself again.

What causes bipolar disorder? How does it start?

- Chemicals in the brain that are off balance cause bipolar disorder. But we don’t know for sure what makes the chemicals go off balance.

In some cases, symptoms can appear suddenly for no known reason. In other cases, the symptoms seem to come after a life crisis, stress or illness.

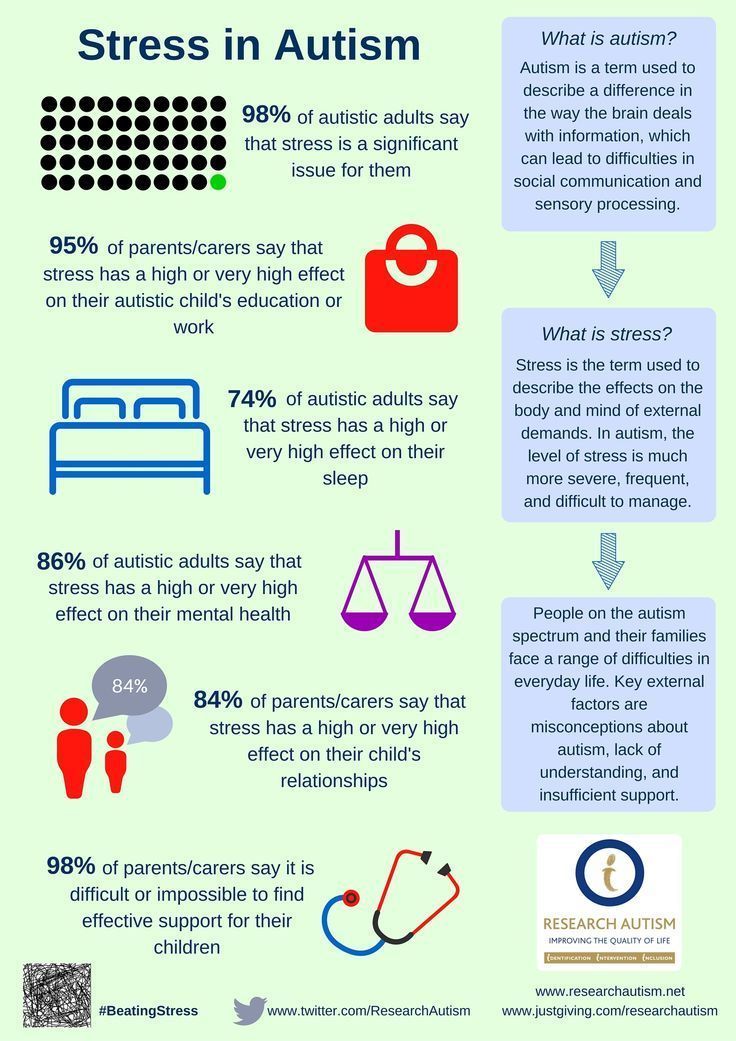

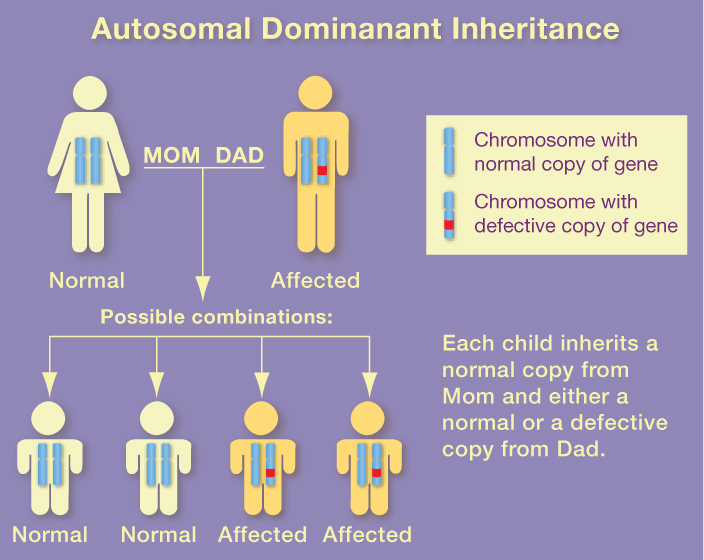

In some cases, symptoms can appear suddenly for no known reason. In other cases, the symptoms seem to come after a life crisis, stress or illness. - Bipolar disorder may also be genetic or inherited. However, it will usually not be passed to children. About one in 10 children of a parent with bipolar disorder will develop the illness. Nine out of 10 will not.

- It’s unclear why, but some people get bipolar disorder more easily than others do.

- The child is not the cause of the parent’s bipolar disorder.

Will the bipolar disorder ever be fixed?

- While there is no cure yet, the good news is that bipolar disorder is treatable. Most people with bipolar disorder manage very well with ongoing treatment and find that the illness is kept under control most of the time so they can lead a normal life.

- Almost everyone who gets treated will improve and some may get completely better. While there is always a chance that the bipolar disorder will come back, medicine can often prevent this from happening.

- If the mood problems do come back, they can be treated again.

How can my mom or dad get better?

- Many different treatments are available, including medicine and talk therapy.

- Medicine helps to make the chemicals in the brain work like usual. It can help people with bipolar disorder to be able to think, feel and behave more like their usual selves.

- Talk therapy gets people with bipolar disorder to talk with a therapist about what they are experiencing. The therapy helps them learn new ways to cope and to think, feel and behave in more positive ways. Sometimes the therapist will talk to the children and the family too, which can also help the person with bipolar disorder get better.

- There are also other kinds of treatment. If a child has questions about the help that a parent is getting, the child should ask to talk with a doctor, nurse or counsellor.

Is there anything I can do to make my mom or dad better?

- Family support is really important for people who have bipolar disorder, but it is the adults (such as doctors and therapists) who are responsible for being the “helpers,” not the kids.

- Even though you can’t fix bipolar disorder, sometimes just knowing what your parent is going through, and understanding that he or she has an illness and can get better, can help your parent.

Will it happen to me? Will I get it too?

- No one can ever know for sure if they will get bipolar disorder at some point in their lives.

- It’s natural to worry about this. Just like other illnesses, such as arthritis and diabetes, having bipolar disorder in your family might put you at greater risk of getting bipolar disorder yourself. But the chance of NOT getting the illness is far greater than the chance of getting the illness.

- It’s more important to focus on what you can do to help yourself deal with stress and lead a balanced life.

- If you are worried about getting bipolar disorder, try and find an adult that you trust to talk about your feelings.

Is there anything I can do so that I don’t get bipolar disorder?

- One of the most important things that kids can do to stay healthy and happy is to be open about how they’re feeling.

It’s healthy to let parents or other grown-ups in their life know what they’re going through.

It’s healthy to let parents or other grown-ups in their life know what they’re going through. - By talking to parents, another family member, teacher or other grown-ups who care, kids can get the help they need to feel better and solve problems in their lives.

- Some kids who have a parent with bipolar disorder don’t always talk about the times when they’re feeling angry, sad, scared or confused. They think they will just give their parents something else to worry about, or that others don’t want to hear about those feelings. But that’s just not true!

- Participating in sports, hobbies and other activities with healthy grown-ups and kids is important because it helps to have fun and feel good about yourself.

- If the child is worried that he or she might have really low moods or really high moods, the child can talk to an adult (parent, teacher and/or family doctor) about it.

Can parents give it to other people? Is it like a cold? Can you catch bipolar disorder?

- No.

Bipolar disorder isn’t like a cold. There’s no germ. It’s not contagious.

Bipolar disorder isn’t like a cold. There’s no germ. It’s not contagious. - There is no way of catching it. So a child could hang out with someone with bipolar disorder without ever having to worry about getting it.

What should I do if I am scared? What can I do when I’m really worried about my parent who has bipolar disorder?

- Sometimes children feel better if they make an action plan with their parents before they see mood changes in the parent with bipolar disorder. This helps them make decisions about what to do when they are scared.

- Action plans can include:

- making a list of “signs” that tell the child the parent is doing well

- making a list of “signs” that tell the child that the parent is not doing well

- having the name and number of an adult the child can call and

- writing down questions or worries.

- If the child is worried and has no one to talk to, he or she can call the Kids Help Phone at 1-800-668-6868 to talk to an adult who can help.

- If there is an emergency and the child needs someone there fast because he or she is worried that someone might get hurt or is hurt, the child can call 911.

- Sometimes people with bipolar disorder need to be in the hospital for a while to get better. If this happens, the child should make sure to get all his or her questions answered. Understanding what is going on will help the child to worry less and feel

better about the situation.

Questions about self-harm

The questions we’ve listed touch on the major issues of interest to children. However, children can ask many different questions about family situations. Once a conversation starts, it is difficult to know exactly what children might ask. Most parents are able to manage “spin-off” questions (e.g., Why is mom in the hospital? When will she come home?). The topic of suicide is harder to handle.

Many people with bipolar disorder do not have suicidal thoughts. This is why we do not include this material in question-and-answer format. If questions arise around suicide or a parent self-harming, here are some ideas on how to share information with the child.

This is why we do not include this material in question-and-answer format. If questions arise around suicide or a parent self-harming, here are some ideas on how to share information with the child.

When children hear that someone is ill, they naturally wonder if the person might die. Children have asked if bipolar disorder can kill a person. While suicide is a risk with bipolar disorder, it is only one of the many symptoms a person might have. Children should understand that bipolar disorder does not cause the body to stop working, like a heart attack might. So no, it doesn’t kill people. But there are times when people with bipolar disorder might feel so bad while depressed that they say things like, “I want to die.” This can be a scary thing for a child to hear. And, once in a while, some people with bipolar disorder do try to hurt or kill themselves when they think and feel this way. When people feel this way, they need to see their doctor and/or therapist who can help.

If discussing this issue with children, it is important to reassure them that:- The parent has never wanted to hurt or kill him or herself.

(Say this only if it’s true.)

(Say this only if it’s true.) - If the parent were feeling so bad that he or she wanted to die, a doctor, therapist or other adult could help the parent keep safe and stop feeling that way.

Brochures in the When a Parent Series

When a parent drinks too much: What kids want to know

When a parent is depressed: What kids want to know

When a parent has psychosis: What kids want to know

Before the new year, help us create hope for those living with mental illness.

Give OnceGive Monthly

My gift is in memory or honour of someone

I am donating on behalf of an organization

Other Ways to Give

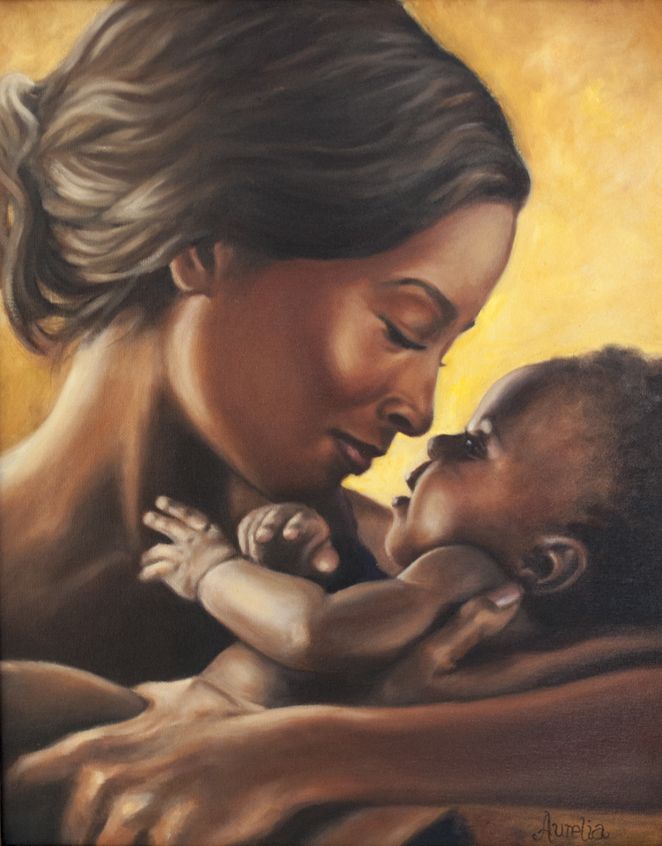

Mother-to-Infant Bonding in Women With a Bipolar Spectrum Disorder

1. Mesman E, Nolen WA, Reichart CG, Wals M, Hillegers MHJ. The dutch bipolar offspring study: 12-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. (2013) 170:542–9. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030401 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Mesman E, Nolen WA, Reichart CG, Wals M, Hillegers MHJ. The dutch bipolar offspring study: 12-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. (2013) 170:542–9. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030401 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. Lau P, Hawes DJ, Hunt C, Frankland A, Roberts G, Mitchell PB. Prevalence of psychopathology in bipolar high-risk offspring and siblings: a meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2018) 27:823–37. 10.1007/s00787-017-1050-7 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Sandstrom A, Sahiti Q, Pavlova B, Uher R. Offspring of parents with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression: a review of familial high-risk and molecular genetics studies. Psychiatr Genet. (2019) 29:160–9. 10.1097/YPG.0000000000000240 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Wescott DL, Morash-Conway J, Zwicker A, Cumby J, Uher R, Rusak B. Sleep in offspring of parents with mood disorders. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:1–8. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00225 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Santucci AK, Singer LT, Wisniewski SR, Luther JF, Eng HF, Sit DK, et al.. One-year developmental outcomes for infants of mothers with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. (2017) 78:1083–90. 10.4088/JCP.15m10535 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Santucci AK, Singer LT, Wisniewski SR, Luther JF, Eng HF, Sit DK, et al.. One-year developmental outcomes for infants of mothers with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. (2017) 78:1083–90. 10.4088/JCP.15m10535 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Bora E, Özerdem A. A meta-analysis of neurocognition in youth with familial high risk for bipolar disorder. Eur Psychiatry. (2017) 44:17–23. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.02.483 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Klimes-Dougan B, Jeong J, Kennedy KP, Allen TA. Intellectual functioning in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: a review of the literature. Brain Sci. (2017) 7:21–3. 10.3390/brainsci7110143 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Bella T, Goldstein T, Axelson D, Obreja M, Monk K, Hickey MB, et al.. Psychosocial functioning in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. (2011) 133:204–11. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.022 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Iacono V, Beaulieu L, Hodgins S, Ellenbogen MA. Parenting practices in middle childhood mediate the relation between growing up with a parent having bipolar disorder and offspring psychopathology from childhood into early adulthood. Dev Psychopathol. (2018) 30:635–49. 10.1017/S095457941700116X [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Iacono V, Beaulieu L, Hodgins S, Ellenbogen MA. Parenting practices in middle childhood mediate the relation between growing up with a parent having bipolar disorder and offspring psychopathology from childhood into early adulthood. Dev Psychopathol. (2018) 30:635–49. 10.1017/S095457941700116X [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Freed RD, Tompson MC, Otto MW, Nierenberg AA, Hirshfeld-Becker D, Wang CH, et al.. Early risk factors for psychopathology in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: the role of obstetric complications and maternal comorbid anxiety. Depress Anxiety. (2014) 31:583–90. 10.1002/da.22254 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Schreuder MM, Vinkers CH, Mesman E, Claes S, Nolen WA, Hillegers MHJ. Childhood trauma and HPA axis functionality in offspring of bipolar parents. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2016) 74:316–23. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.09.017 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Koenders MA, Mesman E, Giltay EJ, Elzinga BM, Hillegers MHJ. Traumatic experiences, family functioning, and mood disorder development in bipolar offspring. Br J Clin Psychol. (2020) 59:277–89. 10.1111/bjc.12246 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Traumatic experiences, family functioning, and mood disorder development in bipolar offspring. Br J Clin Psychol. (2020) 59:277–89. 10.1111/bjc.12246 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Doucette S, Levy A, Flowerdew G, Horrocks J, Grof P, Ellenbogen M, et al.. Early parent–child relationships and risk of mood disorder in a Canadian sample of offspring of a parent with bipolar disorder: findings from a 16-year prospective cohort study. Early Interv Psychiatry. (2016) 10:381–9. 10.1111/eip.12195 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Winston R, Chicot R. The importance of early bonding on the long-term mental health and resilience of children. London J Prim Care (Abingdon). (2016) 8:12–4. 10.1080/17571472.2015.1133012 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Bicking Kinsey C, Hupcey JE. State of the science of maternal-infant bonding: a principle-based concept analysis. Midwifery. (2013) 29:1314–20. 10.1016/j.midw.2012.12.019 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Fuchs A, Möhler E, Reck C, Resch F, Kaess M. The early mother-to-child bond and its unique prospective contribution to child behavior evaluated by mothers and teachers. Psychopathology. (2016) 49:211–6. 10.1159/000445439 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Fuchs A, Möhler E, Reck C, Resch F, Kaess M. The early mother-to-child bond and its unique prospective contribution to child behavior evaluated by mothers and teachers. Psychopathology. (2016) 49:211–6. 10.1159/000445439 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Mason ZS, Briggs RD, Silver EJ. Maternal attachment feelings mediate between maternal reports of depression, infant social-emotional development, and parenting stress. J Reprod Infant Psychol. (2011) 29:382–94. 10.1080/02646838.2011.629994 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. de Cock ESA, Henrichs J, Klimstra TA, Janneke A, Vreeswijk CMJM, Meeus WHJ, et al.. Longitudinal associations between parental bonding, parenting stress, and executive functioning in toddlerhood. J Child Fam Stud. (2017) 26:1723–33. 10.1007/s10826-017-0679-7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Cuijlits I, de Wetering AP, Endendijk JJ, Baar AL, Potharst ES, Pop VJM. Risk and protective factors for pre- and postnatal bonding. Infant Ment Health J. (2019) 40:768–85. 10.1002/imhj.21811 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Infant Ment Health J. (2019) 40:768–85. 10.1002/imhj.21811 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Dubber S, Reck C, Müller M, Gawlik S. Postpartum bonding: the role of perinatal depression, anxiety and maternal–fetal bonding during pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health. (2015) 18:187–95. 10.1007/s00737-014-0445-4 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Hornstein C, Trautmann-Villalba P, Hohm E, Rave E, Wortmann-Fleischer S, Schwarz M. Maternal bond and mother-child interaction in severe postpartum psychiatric disorders: Is there a link? Arch Womens Ment Health. (2006) 9:279–84. 10.1007/s00737-006-0148-6 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22. Noorlander Y, Bergink V, Van Den Berg MP. Perceived and observed mother-child interaction at time of hospitalization and release in postpartum depression and psychosis. Arch Womens Ment Health. (2008) 11:49–56. 10.1007/s00737-008-0217-0 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. Tichelman E, Westerneng M, Witteveen AB, van Baar AL, van der Horst HE, de Jonge A, et al. . Correlates of prenatal and postnatal mother-to-infant bonding quality: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. (2019) 14:e0222998. 10.1371/journal.pone.0222998 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

. Correlates of prenatal and postnatal mother-to-infant bonding quality: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. (2019) 14:e0222998. 10.1371/journal.pone.0222998 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

24. O'Higgins M, Roberts ISJ, Glover V, Taylor A. Mother-child bonding at 1 year; Associations with symptoms of postnatal depression and bonding in the first few weeks. Arch Womens Ment Health. (2013) 16:381–9. 10.1007/s00737-013-0354-y [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Anke TMS, Slinning K, Skjelstad DV. “What if I get ill?” perinatal concerns and preparations in primi- and multiparous women with bipolar disorder. Int J Bipolar Disord. (2019) 7:7. 10.1186/s40345-019-0143-2 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Truijens SEM, Meems M, Kuppens SMI, Broeren MAC, Nabbe KCAM, Wijnen HA, et al.. The HAPPY study (Holistic Approach to Pregnancy and the first Postpartum Year): design of a large prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2014) 14:1–12. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-312 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

(2014) 14:1–12. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-312 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

27. Cuijlits I, Van de Wetering A, Potharst E, Truijens S, Van Baar A, Pop V. Development of a Pre- and Postnatal Bonding Scale (PPBS). J Psychol Psychother. (2016) 6:282. 10.4172/2161-0487.1000282 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

28. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. (1987) 150:782–6. 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Cox JL, Chapman G, Murray D, Jones P. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in non- postnatal women. J Affect Disord. (1996) 39:185–9. 10.1016/0165-0327(96)00008-0 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

30. Bergink V, Kooistra L, Lambregtse-van den Berg MP, Wijnen H, Bunevicius R, van Baar A, et al.. Validation of the Edinburgh Depression Scale during pregnancy. J Psychosom Res. (2011) 70:385–9. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.07.008 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.07.008 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

31. Pop VJ, Komproe IH, van Son MJ. Characteristics of the Edinburgh PostNatal Depression Scale in The Netherlands. J Affect Disord. (1992) 26:105–10. 10.1016/0165-0327(92)90041-4 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

32. Meltzer-Brody S, Boschloo L, Jones I, Sullivan PF, Penninx BW. The EPDS-lifetime: assessment of lifetime prevalence and risk factors for perinatal depression in a large cohort of depressed women. Arch Womens Ment Health. (2013) 16:465–73. 10.1007/s00737-013-0372-9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

33. Wesseloo R, Kamperman AM, Munk-Olsen T, Pop VJM, Kushner SA, Bergink V. Risk of postpartum relapse in bipolar disorder and postpartum psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. (2016) 173:117–27. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15010124 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

34. Barsky AJ. Forgetting, fabricating, and telescoping. Arch Intern Med. (2002) 162:981. 10.1001/archinte.162.9.981 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

(2002) 162:981. 10.1001/archinte.162.9.981 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

35. Statistics the Netherlands . Population; Educational Level; Gender, Age and Migration Background (Bevolking; Onderwijsniveau; Geslacht, Leeftijd en Migratieachtergrond). (2019). Available online at: https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/82275NED/table?fromstatweb (accessed October 22, 2019).

36. Werner EA, Gustafsson HC, Lee S, Feng T, Jiang N, Desai P, et al.. PREPP: postpartum depression prevention through the mother–infant dyad. Arch Womens Ment Health. (2016) 19:229–42. 10.1007/s00737-015-0549-5 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

37. Letourneau NL, Dennis CL, Cosic N, Linder J. The effect of perinatal depression treatment for mothers on parenting and child development: a systematic review. Depress Anxiety. (2017) 34:928–66. 10.1002/da.22687 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

38. de Cock ESA, Henrichs J, Vreeswijk CMJM, Maas AJBM, Rijk CHAM, van Bakel HJA. Continuous feelings of love? The parental bond from pregnancy to toddlerhood. J Fam Psychol. (2016) 30:125–34. 10.1037/fam0000138 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Continuous feelings of love? The parental bond from pregnancy to toddlerhood. J Fam Psychol. (2016) 30:125–34. 10.1037/fam0000138 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

What mental illnesses are inherited - Atlant, medical center

Are mental illnesses hereditary? This question worries many parents. After all, it is very scary to “reward” your child with a mental disorder.

How mental illness is transmitted

The fact that mental illness can be inherited has been noticed for a long time. Today, geneticists confirm: indeed, mental disorders are more likely to appear in a child in a family where a relative suffered from a similar illness. And the reason for this are violations in the structure of genes.

There is such a thing as the coefficient of hereditary risk. The higher this coefficient, the higher the likelihood that the child will inherit the disease of relatives.

Only some mental illnesses are directly related to breakdowns in the genes, for example, Huntington's chorea, the hereditary risk coefficient of which is 5000. For comparison, for such a mental illness as schizophrenia, it is 9.

How does the degree of relationship affect hereditary diseases?

The risk of developing a mental illness depends on the degree of relationship with a sick family member and on the number of sick relatives.

The highest probability of transmission of the disease in identical twins, followed by 1st degree relationship (parents, children, brothers, sisters). In 2nd degree relatives, the risk is significantly reduced

So, with schizophrenia, which is present in the mother and father, the probability of its occurrence in children is 46%, if one parent is sick - about 13%, if the grandfather or grandmother is sick - 5%.

Which mental illnesses are most often inherited

1. Disorders of the mental development of children

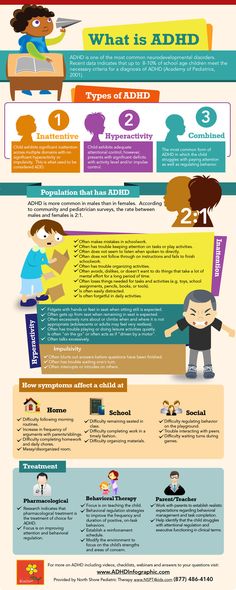

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is manifested by impulsivity, difficulty concentrating, increased physical activity.

Often this disorder is combined with depression, behavioral disorders.

Often this disorder is combined with depression, behavioral disorders. - Dyslexia - the inability to read, compare what is written with speech in some cases is hereditary.

- Autism is a severe mental disorder, expressed in violation of social adaptation. An autistic child is closed, he does not want to communicate with the outside world, he exists in his personal space. He does not tolerate any change, he has his own rituals, which he strictly observes. He constantly repeats stereotypical movements (rocking, bouncing) or the same phrases.

Autism is usually diagnosed in the first three years of a child's life.

It is believed that the role of heredity in the occurrence of this disease is great.

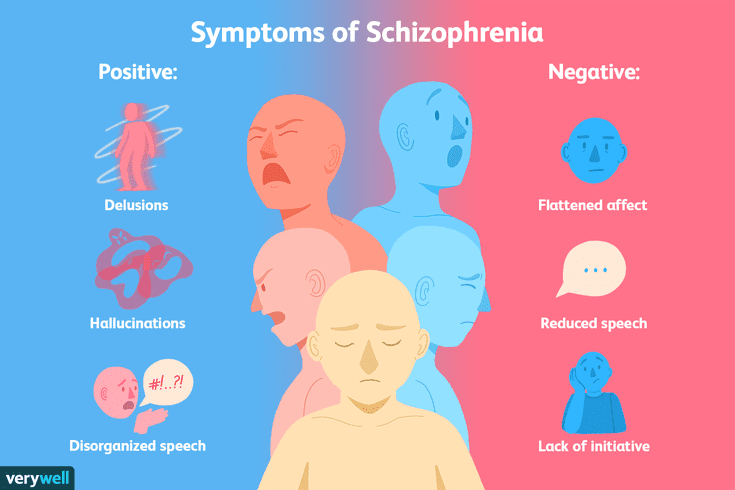

2. Schizophrenia

This is a mental illness, which is characterized by disturbances in thinking, perception of the world, inappropriate behavior and an abnormal reaction to stimuli. The disease may be accompanied by agitation, delusions, hallucinations. Patients are prone to depression and suicidal.

Patients are prone to depression and suicidal.

As a rule, the onset of the disease falls on the age of 20-22 to 30 years.

Heredity plays a significant role in the occurrence of this disease, but other factors are no less important: complications during gestation, difficult childbirth in the mother, infections, difficult psycho-emotional situations, and even birth in winter.

3. Affective bipolar disorder

Otherwise, this mental illness is called manic-depressive psychosis. It proceeds with an alternation of phases: depression and excitement, sometimes with aggression. There may be gaps between these phases.

4. Alzheimer's disease

This disease develops after the age of 65 and is expressed first in forgetfulness, difficulty concentrating. Then there is confusion, loss of orientation in space. Irritability, unmotivated aggression appear, speech is disturbed. Dementia develops.

Rarely enough, the disease begins earlier, and here the hereditary factor, the pathological gene, plays a significant role.

Other hereditary mental illnesses:

- epilepsy;

- psychopathy;

- alcohol dependence;

- dementia;

- Down syndrome;

- Huntington's chorea;

- "cat cry" syndrome;

- Klinefelter's syndrome.

All of these mental illnesses can be inherited. At the same time, they can appear in a family where no one has suffered from such disorders. True, the risk of disease in this case is less, but it exists. So, you can get schizophrenia in a completely “healthy” family with a probability of 1%.

If there is a risk

Many people are afraid of passing on hereditary diseases to their children (even if distant relatives suffered from them), especially mental disorders, and therefore prefer not to have a child. Is such an approach correct?

A hereditary disease does not mean at all that a child will definitely have it. Yes, there is such a risk, but it is also present in children from "hereditarily safe" families. Moreover, the chance of passing on a hereditary disease can be very low. It all depends on what kind of genetic disease exists in the family history, which of the relatives had a pathology, how severe the deviation was, and many other factors.

Moreover, the chance of passing on a hereditary disease can be very low. It all depends on what kind of genetic disease exists in the family history, which of the relatives had a pathology, how severe the deviation was, and many other factors.

You can understand how big the risk is after passing a medical genetic examination. Therefore, in case of doubts and fears of “bad heredity”, the most correct approach would be to contact a geneticist.

Maternal burnout: personal experience

Marina lives in Berlin. She has a husband and two children. Doctors diagnosed Marina with bipolar affective disorder, which seriously affects her life. It took several years to make a diagnosis, and the selection of treatment also took time.

Website editor

Tags:

Mental disorders

Documentary film

postpartum depression

Emotional burnout

bipolar disorder

Marina is one of the characters in the second season of the documentary series Am I Psycho?, which aims to destigmatize mental illness, tell and show how people with depression, bipolar disorder and other illnesses live and what they face every day.

Marina and I talked about maternal burnout, the pandemic, bipolar disorder and family support, and the film's director Daria Belova told how the film was made.

“Without my husband, I definitely wouldn't have coped”

Berlin is a small city. I was invited to participate by my friend, who was casting for this project. I thought that I have something to say to women who find themselves in a difficult situation of motherhood and cannot fully realize that they are not alone. I wanted them to hear that they were not alone. I am convinced that loneliness makes things worse, and knowing that there are other mothers like her in the same difficult circumstances with the same feelings makes life a little easier.

My story began a long time ago. Initially, the first depressive crisis happened at the age of 16, when I was in the 11th grade. There was severe depression and a suicide attempt. Parents did not know what to do, we turned to the most ordinary district psychiatrist. He didn’t even diagnose me, wrote in the card, like many others, “sluggish schizophrenia”, prescribed drugs that didn’t suit me, I spent a whole year on them, until my parents realized that something was going wrong. Then I didn't get any treatment.

Parents did not know what to do, we turned to the most ordinary district psychiatrist. He didn’t even diagnose me, wrote in the card, like many others, “sluggish schizophrenia”, prescribed drugs that didn’t suit me, I spent a whole year on them, until my parents realized that something was going wrong. Then I didn't get any treatment.

I was 20 when I met my husband. He perfectly observed the "swings", changes in my condition over many years: he well distinguished my manic phase, while I recognized only the depressive one. We have been together for almost 17 years, and he knows me better than I do myself. I am very grateful to him for his support, without him I definitely would not have done well.

“Not a good enough mother”

I was 25 when our eldest son Andrei was born. After he was born, I had severe postpartum depression. Then I didn’t know such words, I didn’t go into details, but I just felt terrible. We had a difficult baby: he cried a lot and often, it was difficult to rock him, to establish a routine.

We had a difficult baby: he cried a lot and often, it was difficult to rock him, to establish a routine.

As soon as Andrei grew up and began to walk, he began to show signs of hyperactivity. He exhausted me terribly: from depression, I smoothly flowed into maternal burnout. Andrei scattered the books that I tried to read to him, threw the toys that I tried to play with him, in the end I gave up these attempts, I stopped coping, I lost the desire to do something.

I had a tremendous sense of guilt, because other mothers take care of children and somehow develop them, and I do nothing. I'm a bad mother, just a terrible one, that's what I thought at the time.

When he was 6 years old, our youngest son Slava was born. The birth was very good, unlike the first experience, there was a lot of oxytocin, depression after the birth was not so pronounced, rather, the usual maternal exhaustion.

And then there was a move. Despite the fact that I really wanted to live in Berlin, the move was very difficult for me. I "fell" into such a deep depression, which I have not yet had. I was hurt and bitter, I did not see the point in anything, I felt emotional emptiness. Complete apathy, I couldn't do anything. Ultimately, this began to affect my physical condition, I felt a strong weakness. I had to pick up my son from the garden - I got out of the car and rested, climbed the stairs and rested, there was severe shortness of breath, my pulse went off scale, my head was spinning.

Despite the fact that I really wanted to live in Berlin, the move was very difficult for me. I "fell" into such a deep depression, which I have not yet had. I was hurt and bitter, I did not see the point in anything, I felt emotional emptiness. Complete apathy, I couldn't do anything. Ultimately, this began to affect my physical condition, I felt a strong weakness. I had to pick up my son from the garden - I got out of the car and rested, climbed the stairs and rested, there was severe shortness of breath, my pulse went off scale, my head was spinning.

“I am a person with a mental disorder”

I lived in this state for almost a year until my husband persuaded me to go to a psychiatrist. Remembering my previous experience, I was very reluctant to go to the doctor. My first psychiatrist in Berlin turned out to be an unpleasant person: the appointment lasted two minutes, she prescribed me completely inappropriate doses of drugs, as a result of which, after three days, I was literally “thrown out of deep depression” into the upper, manic phase.

Soon I arrived in Moscow, where I went to see another specialist, my friend, a psychotherapist, referred me to him. We had several meetings, detailed conversations, adequate diagnostics. In the very first session, the dosage of the drugs was adjusted for me, and I soon began to feel normal.

A German psychiatrist prescribed medication without a diagnosis, which could have done me a lot of harm. Thanks to my husband that he feels and understands me and my impulses, knows how to correct it with words. And I trust him.

The Moscow doctor said that I have bipolar affective disorder. My life has changed: I was diagnosed, I started taking drugs in the right dosage. After some time, my husband said that now he is not afraid to go home from work in the evening. It turned out that earlier he went home with fear, not knowing what he would see there. I didn't know any of this, he never told me. He became much calmer, I felt much better.

Now I am used to my diagnosis. I should not suffer every day because I am a person with a mental disorder. I treat this normally and even with irony. You can live with a mental disorder, build a family, have children. This is not a "cross for life" - you can live with it, but not exist.

“I know for sure that I am not alone”

The feeling of “not being a good enough mother” has not gone away. This can be corrected, for this you need a good long-term psychotherapy. I had psychotherapy, but I was not ready to return to a past life, dig deeper and "pull out demons." It hurts too much - now the choice is clear for me. I don't want to dive into pain to make my life better. But maternal burnout is definitely common in many, as is postpartum depression. It's terrible that it exists, but you don't have to blame yourself.

Medications are also incapable of changing my attitude towards motherhood - they work differently, affecting only the biochemical processes in the brain. Fatigue does not disappear, it does not go away, the children are here, and I continue to boil in it.

Fatigue does not disappear, it does not go away, the children are here, and I continue to boil in it.

In the lockdown, when this film was being shot, it got really bad. We settled in all the houses, the children stopped going to the garden and school. Home schooling has begun, and we must become teachers for our children. It shouldn’t be like this: a parent should remain a parent, and not a pushy teacher who demands assignments. At some point, I started yelling at Andrey to do his tasks. There was a home office at home - my husband had meetings all day long, this noise stream was very difficult.

I know for sure that I am not alone. It is generally accepted that motherhood is happiness and the only female destiny. In fact, this is not so: the happiness of a woman should and does consist in different things, and is not limited to motherhood. But talking about it is not accepted. There are a lot of people around who do not understand this and do not want to know. There is no gender among such people: they are both men and women, different people with different experiences, who believe that they know how to love children.

There is no gender among such people: they are both men and women, different people with different experiences, who believe that they know how to love children.

I came to the project with the goal of saying: it happens otherwise. Yes, we get tired of our children, getting tired is normal. Feeling different emotions in relation to yourself is normal. We cannot force ourselves not to be angry, we cannot force ourselves not to experience any emotions. Another thing is that we can lock up these emotions, the longer we do this, the more this stone presses on us.

My husband thought for a long time, he didn't want to put our lives on display. On the other hand, he understands that I have something to tell. In the end, we agreed, he agreed. The shooting took place very delicately and carefully - it did not cause us any discomfort. The hardest thing for me was to record my own video diaries, which is why there are few of my diaries in the film.

It's not a fact that this film will change people, but a drop wears away a stone. If we talk more about it, then people will become more patient, more gentle, or maybe more sympathetic. They will understand that not everything is as simple as it may seem to them.

“All our heroes are very brave”

youtube

Click and watch consists of 9 episodes, which tell the stories of five heroes. The series details borderline personality disorder, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic disorder, anxiety depression, and major depressive disorder. The problem of maternal burnout is also touched upon, the symptoms of anxiety and depression are discussed, the impact of lockdown on mental instability, and some methods of cognitive behavioral therapy are shown.

“I am a film director, and making documentaries is not really my profile, but I agreed to participate in this important project,” says Daria Belova.