Mood incongruent psychosis

Mood-incongruent psychotic features in bipolar disorder: familial aggregation and suggestive linkage to 2p11-q14 and 13q21-33

Save citation to file

Format: Summary (text)PubMedPMIDAbstract (text)CSV

Add to Collections

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Name your collection:

Name must be less than 100 characters

Choose a collection:

Unable to load your collection due to an error

Please try again

Add to My Bibliography

- My Bibliography

Unable to load your delegates due to an error

Please try again

Your saved search

Name of saved search:

Search terms:

Test search terms

Email: (change)

Which day? The first SundayThe first MondayThe first TuesdayThe first WednesdayThe first ThursdayThe first FridayThe first SaturdayThe first dayThe first weekday

Which day? SundayMondayTuesdayWednesdayThursdayFridaySaturday

Report format: SummarySummary (text)AbstractAbstract (text)PubMed

Send at most: 1 item5 items10 items20 items50 items100 items200 items

Send even when there aren't any new results

Optional text in email:

Create a file for external citation management software

Full text links

Atypon

Full text links

Case Reports

. 2007 Feb;164(2):236-47.

doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.236.

Fernando S Goes 1 , Peter P Zandi, Kuangyi Miao, Francis J McMahon, Jo Steele, Virginia L Willour, Dean F Mackinnon, Francis M Mondimore, Barbara Schweizer, John I Nurnberger Jr, John P Rice, William Scheftner, William Coryell, Wade H Berrettini, John R Kelsoe, William Byerley, Dennis L Murphy, Elliot S Gershon, Bipolar Disorder Phenome Group, J Raymond Depaulo Jr, Melvin G McInnis, James B Potash

Affiliations

Affiliation

- 1 Johns Hopkins Hospital, 600 North Wolfe St., Meyer 4-119, Baltimore, MD 21287-7419, USA.

- PMID: 17267786

- DOI: 10.

1176/ajp.2007.164.2.236

1176/ajp.2007.164.2.236

Case Reports

Fernando S Goes et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2007 Feb.

. 2007 Feb;164(2):236-47.

doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.236.

Authors

Fernando S Goes 1 , Peter P Zandi, Kuangyi Miao, Francis J McMahon, Jo Steele, Virginia L Willour, Dean F Mackinnon, Francis M Mondimore, Barbara Schweizer, John I Nurnberger Jr, John P Rice, William Scheftner, William Coryell, Wade H Berrettini, John R Kelsoe, William Byerley, Dennis L Murphy, Elliot S Gershon, Bipolar Disorder Phenome Group, J Raymond Depaulo Jr, Melvin G McInnis, James B Potash

Affiliation

- 1 Johns Hopkins Hospital, 600 North Wolfe St.

, Meyer 4-119, Baltimore, MD 21287-7419, USA.

, Meyer 4-119, Baltimore, MD 21287-7419, USA.

- PMID: 17267786

- DOI: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.236

Abstract

Objective: Mood-incongruent psychotic features in bipolar disorder may signify a more severe form of the illness and might represent phenotypic manifestations of susceptibility genes shared with schizophrenia. This study attempts to characterize clinical correlates, familial aggregation, and genetic linkage in subjects with these features.

Method: Subjects were drawn from The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Genetics Initiative Bipolar Disorder Collaborative cohort, consisting of 708 families recruited at 10 academic medical centers. Subjects with mood-incongruent and mood-congruent psychotic features were compared on clinical variables. Familial aggregation was tested using a proband-predictive model and generalized estimating equations. A genome-wide linkage scan incorporating a mood-incongruence covariate was performed.

Subjects with mood-incongruent and mood-congruent psychotic features were compared on clinical variables. Familial aggregation was tested using a proband-predictive model and generalized estimating equations. A genome-wide linkage scan incorporating a mood-incongruence covariate was performed.

Results: Mood-incongruent psychotic features were associated with an increased rate of hospitalization and attempted suicide. A proband with mood-incongruence predicted mood-incongruence in relatives with bipolar I disorder when compared with all other subjects and when compared with subjects with mood-congruent psychosis. The presence of mood-incongruent psychotic features increased evidence for linkage on chromosomes 13q21-33 and 2p11-q14. These logarithm of the odds ratio (LOD) scores and their increase from baseline met empirical genome-wide suggestive criteria for significance.

Conclusions: Mood-incongruent psychotic features showed evidence of a more severe course, familial aggregation, and suggestive linkage to two chromosomal regions previously implicated in major mental illness susceptibility. The 13q21-33 finding supports prior evidence of bipolar disorder/schizophrenia overlap in this region, while the 2p11-q14 finding is, to the authors' knowledge, the first to suggest that this schizophrenia linkage region might also harbor a bipolar disorder susceptibility gene.

The 13q21-33 finding supports prior evidence of bipolar disorder/schizophrenia overlap in this region, while the 2p11-q14 finding is, to the authors' knowledge, the first to suggest that this schizophrenia linkage region might also harbor a bipolar disorder susceptibility gene.

Similar articles

-

Suggestive linkage to chromosomal regions 13q31 and 22q12 in families with psychotic bipolar disorder.

Potash JB, Zandi PP, Willour VL, Lan TH, Huo Y, Avramopoulos D, Shugart YY, MacKinnon DF, Simpson SG, McMahon FJ, DePaulo JR Jr, McInnis MG. Potash JB, et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2003 Apr;160(4):680-6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.680. Am J Psychiatry. 2003. PMID: 12668356

-

The familial aggregation of psychotic symptoms in bipolar disorder pedigrees.

Potash JB, Willour VL, Chiu YF, Simpson SG, MacKinnon DF, Pearlson GD, DePaulo JR Jr, McInnis MG. Potash JB, et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2001 Aug;158(8):1258-64. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1258. Am J Psychiatry. 2001. PMID: 11481160

-

Genotype-phenotype studies in bipolar disorder showing association between the DAOA/G30 locus and persecutory delusions: a first step toward a molecular genetic classification of psychiatric phenotypes.

Schulze TG, Ohlraun S, Czerski PM, Schumacher J, Kassem L, Deschner M, Gross M, Tullius M, Heidmann V, Kovalenko S, Jamra RA, Becker T, Leszczynska-Rodziewicz A, Hauser J, Illig T, Klopp N, Wellek S, Cichon S, Henn FA, McMahon FJ, Maier W, Propping P, Nöthen MM, Rietschel M. Schulze TG, et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2005 Nov;162(11):2101-8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2101. Am J Psychiatry. 2005.

PMID: 16263850

PMID: 16263850 -

The genetics of psychotic bipolar disorder.

Goes FS, Sanders LL, Potash JB. Goes FS, et al. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2008 Apr;10(2):178-89. doi: 10.1007/s11920-008-0030-5. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2008. PMID: 18474212 Review.

-

An overview of the genetics of psychotic mood disorders.

Tsuang MT, Taylor L, Faraone SV. Tsuang MT, et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2004 Jan;38(1):3-15. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(03)00096-7. J Psychiatr Res. 2004. PMID: 14690766 Review.

See all similar articles

Cited by

-

Psychotic symptoms in bipolar disorder and their impact on the illness: A systematic review.

Chakrabarti S, Singh N. Chakrabarti S, et al. World J Psychiatry. 2022 Sep 19;12(9):1204-1232. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v12.i9.1204. eCollection 2022 Sep 19. World J Psychiatry. 2022. PMID: 36186500 Free PMC article.

-

Phenotypes, mechanisms and therapeutics: insights from bipolar disorder GWAS findings.

Li M, Li T, Xiao X, Chen J, Hu Z, Fang Y. Li M, et al. Mol Psychiatry. 2022 Jul;27(7):2927-2939. doi: 10.1038/s41380-022-01523-9. Epub 2022 Mar 29. Mol Psychiatry. 2022. PMID: 35351989 Review.

-

Functional Impairment and Clinical Correlates in Adolescents with Bipolar Disorder Compared to Healthy Controls. A Case-control Study.

Mendez I, Castro-Fornieles J, Lera-Miguel S, Picado M, Borras R, Cosi S, Valenti M, Santamarina P, Font E, Romero S.

Mendez I, et al. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020 Aug;29(3):149-164. Epub 2020 Aug 1. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020. PMID: 32774398 Free PMC article.

Mendez I, et al. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020 Aug;29(3):149-164. Epub 2020 Aug 1. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020. PMID: 32774398 Free PMC article. -

A Novel Cosegregating DCTN1 Splice Site Variant in a Family with Bipolar Disorder May Hold the Key to Understanding the Etiology.

Hallen A, Cooper AJL. Hallen A, et al. Genes (Basel). 2020 Apr 18;11(4):446. doi: 10.3390/genes11040446. Genes (Basel). 2020. PMID: 32325768 Free PMC article.

-

The genetics of bipolar disorder.

Gordovez FJA, McMahon FJ. Gordovez FJA, et al. Mol Psychiatry. 2020 Mar;25(3):544-559. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0634-7. Epub 2020 Jan 6. Mol Psychiatry. 2020. PMID: 31907381 Review.

See all "Cited by" articles

Publication types

MeSH terms

Grant support

- K01 MH072866/MH/NIMH NIH HHS/United States

- K01 MH072866-01/MH/NIMH NIH HHS/United States

Full text links

Atypon

Cite

Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Send To

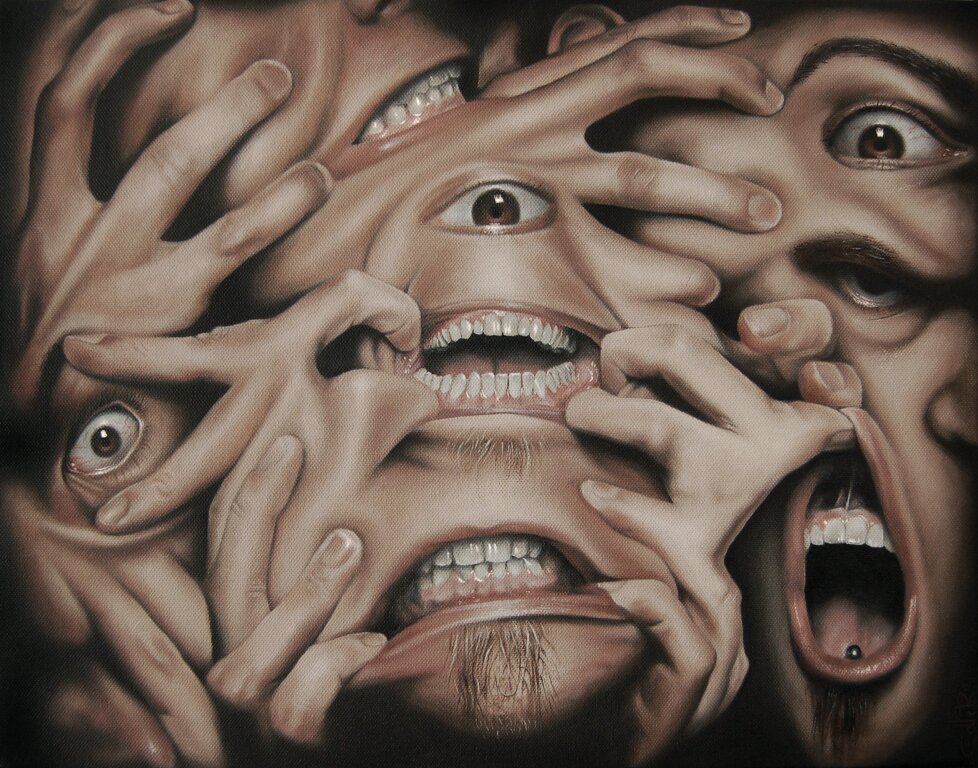

Symptoms & Strategies to Cope

Psychosis if often described as a loss of contact with reality. People who experience episodes of psychosis often aren’t able to recognize what’s real in the world around them.

People who experience episodes of psychosis often aren’t able to recognize what’s real in the world around them.

Psychosis is a legitimate reality for some medical and mental health conditions, including bipolar disorder. Thankfully, episodes of psychosis are manageable. If you know you experience psychosis, you can be prepared with treatments and coping tools.

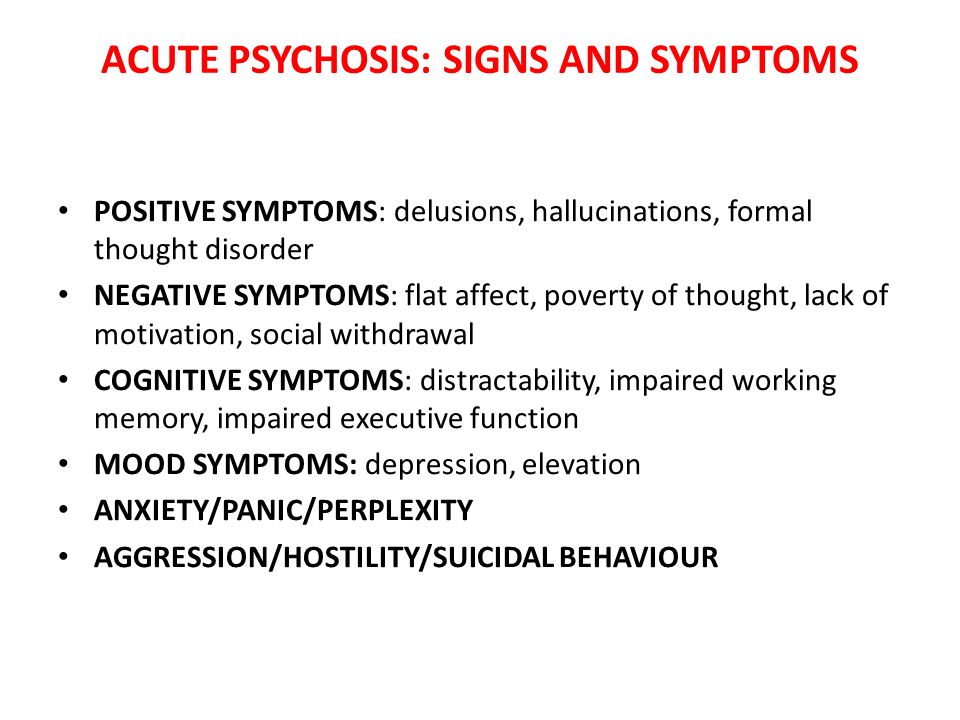

Psychosis is a symptom of a condition, not a disorder. People experiencing psychosis may have hallucinations or delusions.

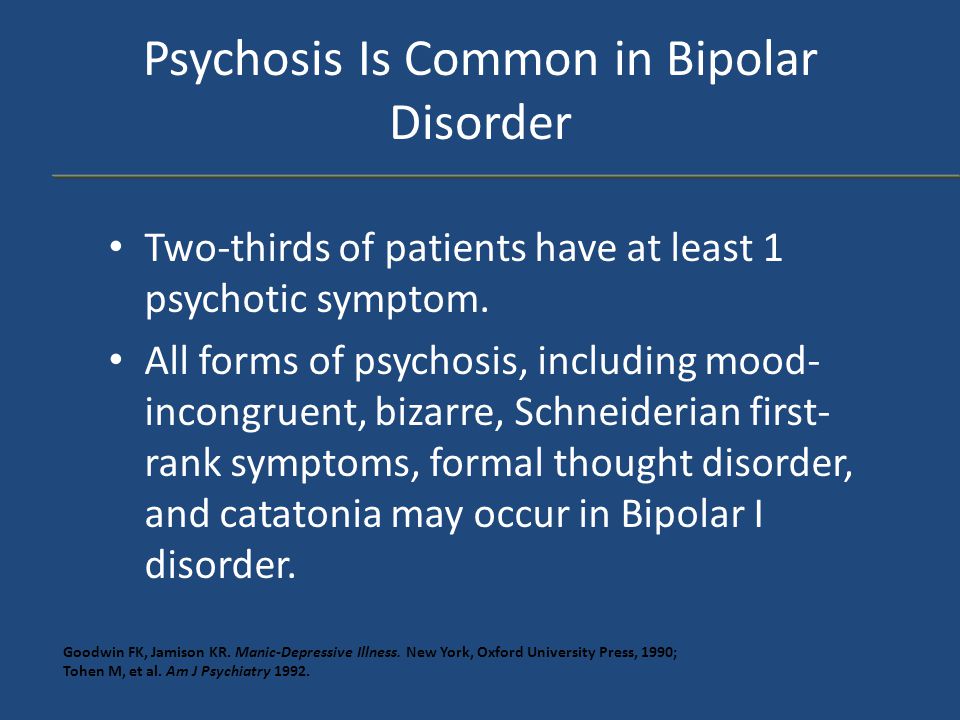

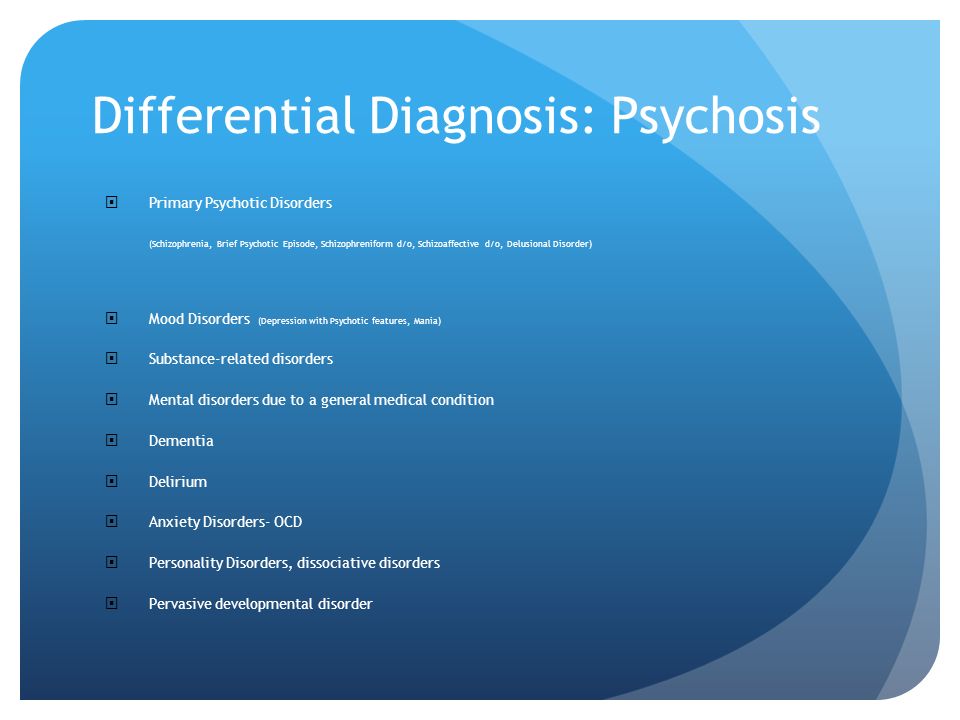

Sometimes, a person with bipolar disorder may experience symptoms of psychosis. This often occurs during a severe episode of mania or depression.

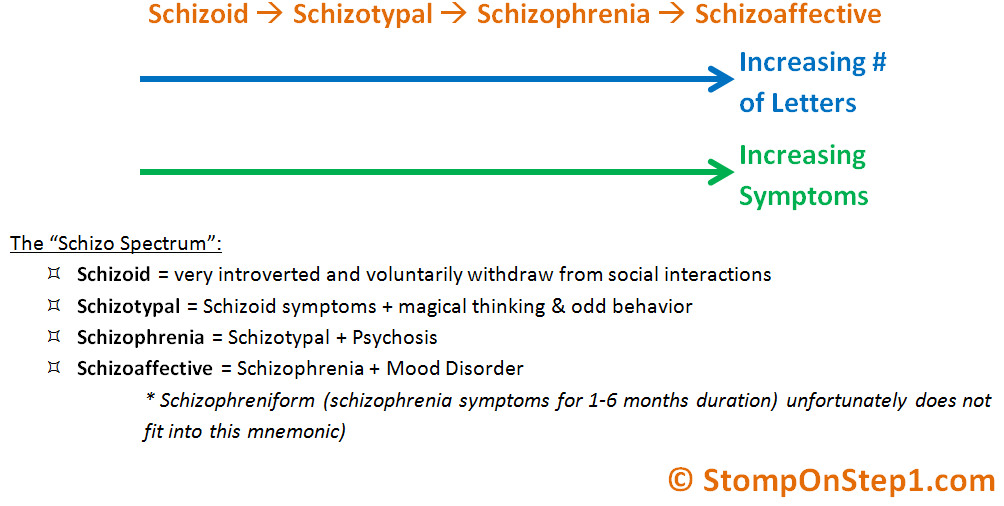

While psychosis is often associated with mental health conditions like bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, it can occur due to other medical conditions and causes.

Hallucinations and delusions can also be experienced as a result of:

- a brain tumor or cyst

- dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease

- neurological conditions such as epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease

- HIV and other sexually transmitted infections that can affect the brain

- malaria

- multiple sclerosis (MS)

- a stroke

Psychosis in bipolar disorder can happen during manic or depressive episodes. But it’s more common during episodes of mania.

But it’s more common during episodes of mania.

Many people believe that psychosis is a sudden, severe break with reality. But psychosis usually develops slowly.

The initial symptoms of psychosis include:

- decreased performance at work or in school

- less than normal attention to personal hygiene

- difficulty communicating

- difficulty concentrating

- reduced social contact

- unwarranted suspicion of others

- less emotional expression

- anxiety

Symptoms of psychosis in bipolar disorder may include:

- hallucinations

- delusions

- incoherent or irrational thoughts and speech

- lack of awareness

Hallucinations

When people hallucinate, they experience things that aren’t real to anyone but themselves. They may hear voices, see things that aren’t there, or have unexplained sensations.

Hallucinations can encompass all the senses.

Delusions

Delusions are an unshakable belief in something that isn’t real, true, or likely to happen.

People may have grandiose delusions. This means they believe they’re invincible or have special powers or talents. In bipolar disorder, delusions of grandeur are common during episodes of mania.

If a person with bipolar disorder experiences depressive episodes, they may experience paranoid delusions. They might believe someone is out to get them or their property.

Jumbled or irrational thoughts and speech

People with psychosis often experience irrational thoughts. Their speech may be fast, rambling, or hard to follow. They may move from subject to subject, losing track of their train of thought.

Lack of awareness

Many people experiencing psychosis may not be aware that their behavior isn’t consistent with what’s actually happening.

They may not recognize that their hallucinations or delusions aren’t real, or notice that other people aren’t experiencing them.

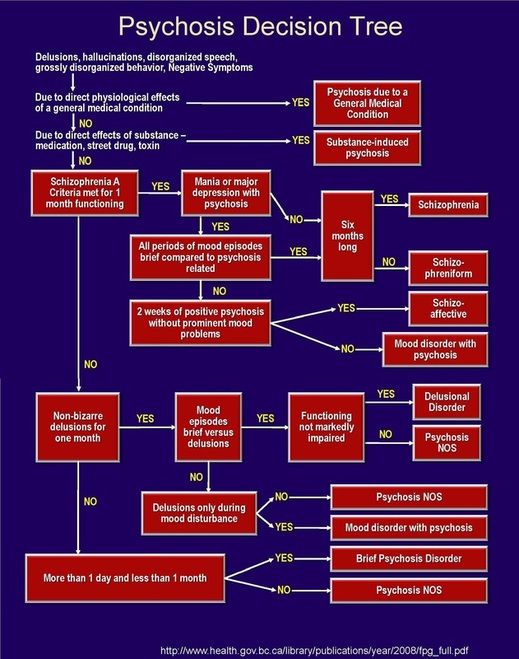

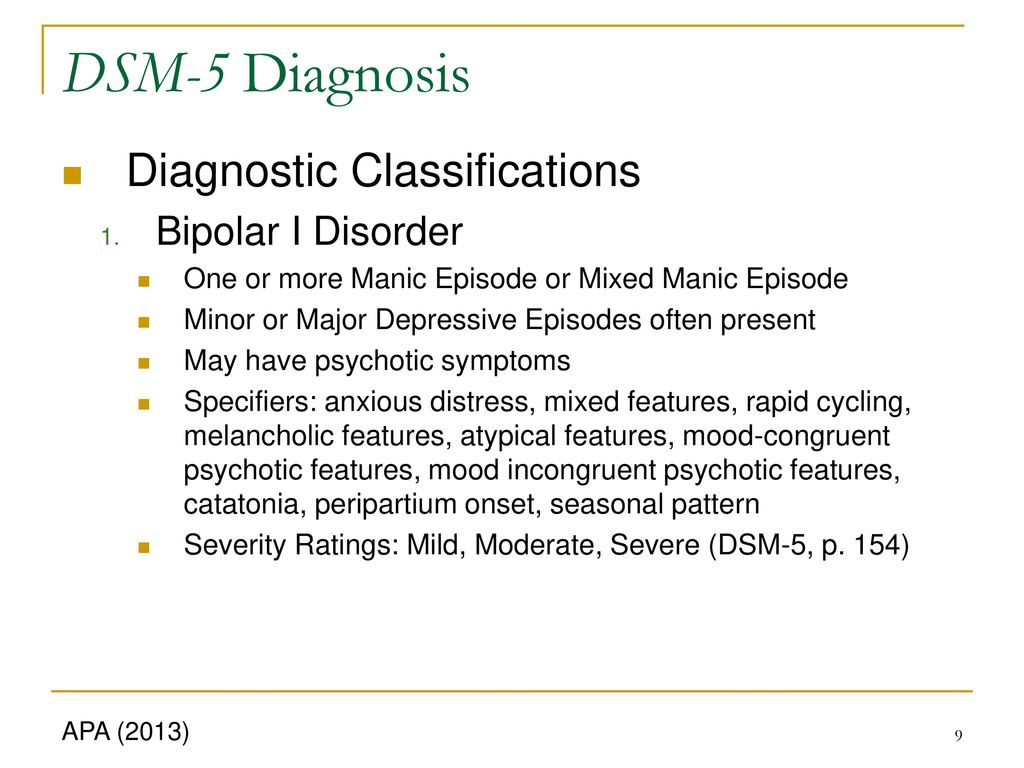

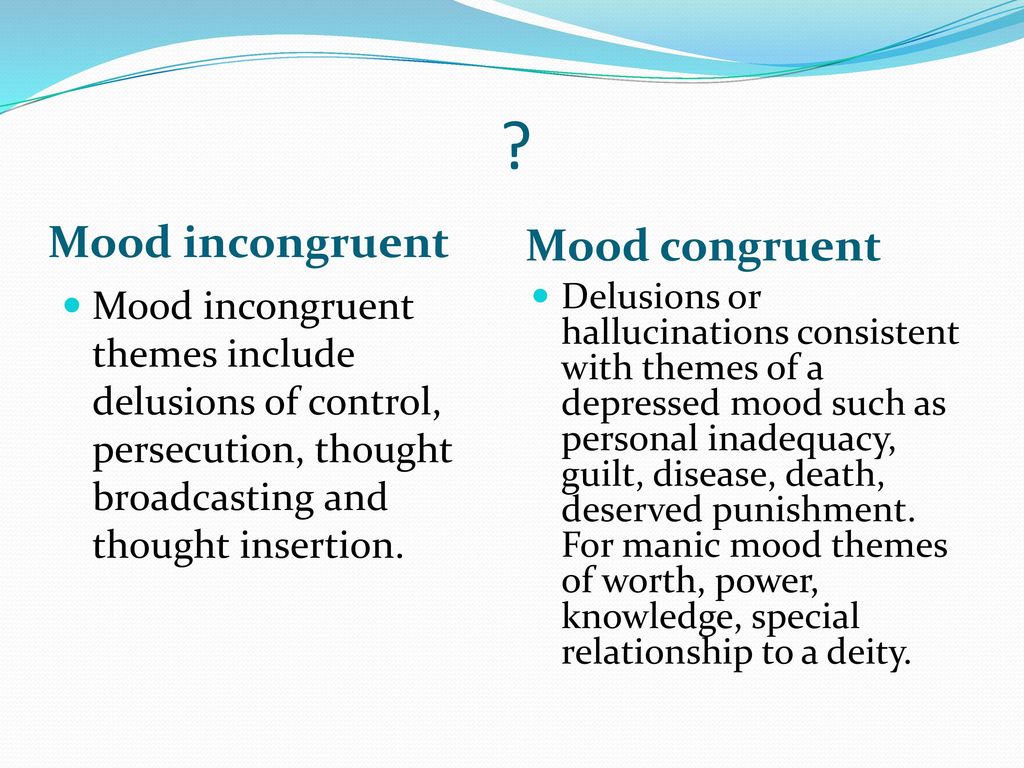

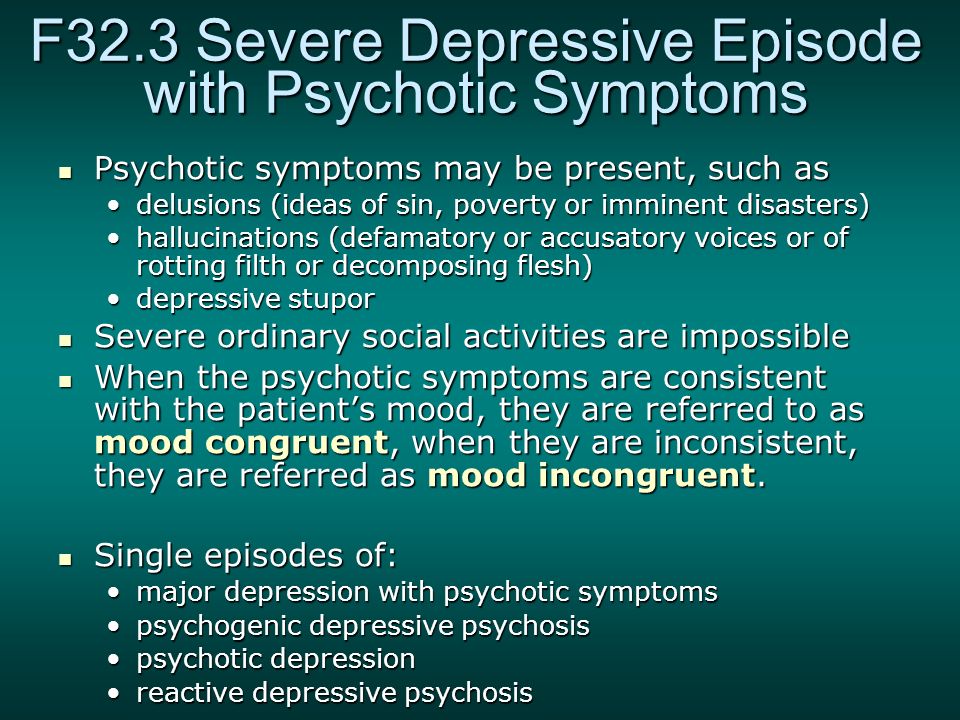

There are two types (or features) of psychosis in people with bipolar disorder: mood congruent and mood incongruent. This means symptoms are either amplifying or reflecting your mood before a manic or depressive episode (congruent), or contradicting your mood (incongruent).

This means symptoms are either amplifying or reflecting your mood before a manic or depressive episode (congruent), or contradicting your mood (incongruent).

Sometimes, both features can occur during the same episode.

Mood congruent psychosis

Most people with bipolar disorder psychosis experience mood congruent features. This means that the delusions or hallucinations reflect your moods, beliefs, or current bipolar disorder episode (mania or depression).

For example, in a depressive episode, you might have feelings of guilt or inadequacy. In a manic episode, you may experience delusions of grandeur.

Mood incongruent psychosis

Mood incongruent symptoms are in opposition to your current mood.

This type of psychosis may involve hearing voices or thoughts, or believing you’re being controlled by others. During a depressive episode, you may also not feel guilt or other negative thoughts that are typical during depression.

Mood incongruence may be more severe. Results of an older 2007 study indicated that people with mood incongruent psychosis in bipolar disorder are more likely to need hospitalization.

Results of an older 2007 study indicated that people with mood incongruent psychosis in bipolar disorder are more likely to need hospitalization.

The exact cause of psychosis in bipolar disorder isn’t well understood. But we do know some factors that may play a role in developing psychosis:

- Sleep deprivation. Sleep disturbances have been associated with lower quality of life in general for people with bipolar disorder and may trigger worse symptoms.

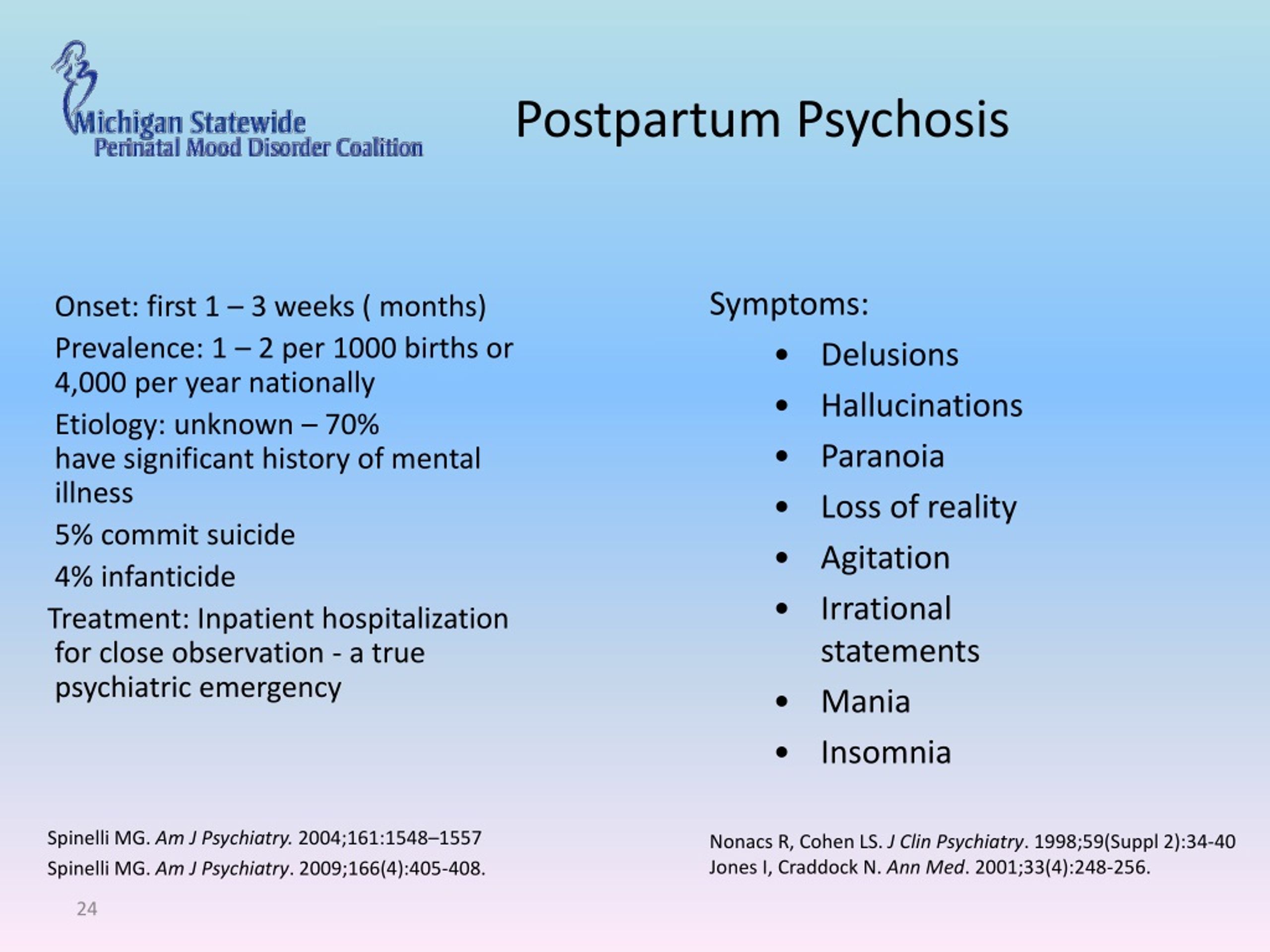

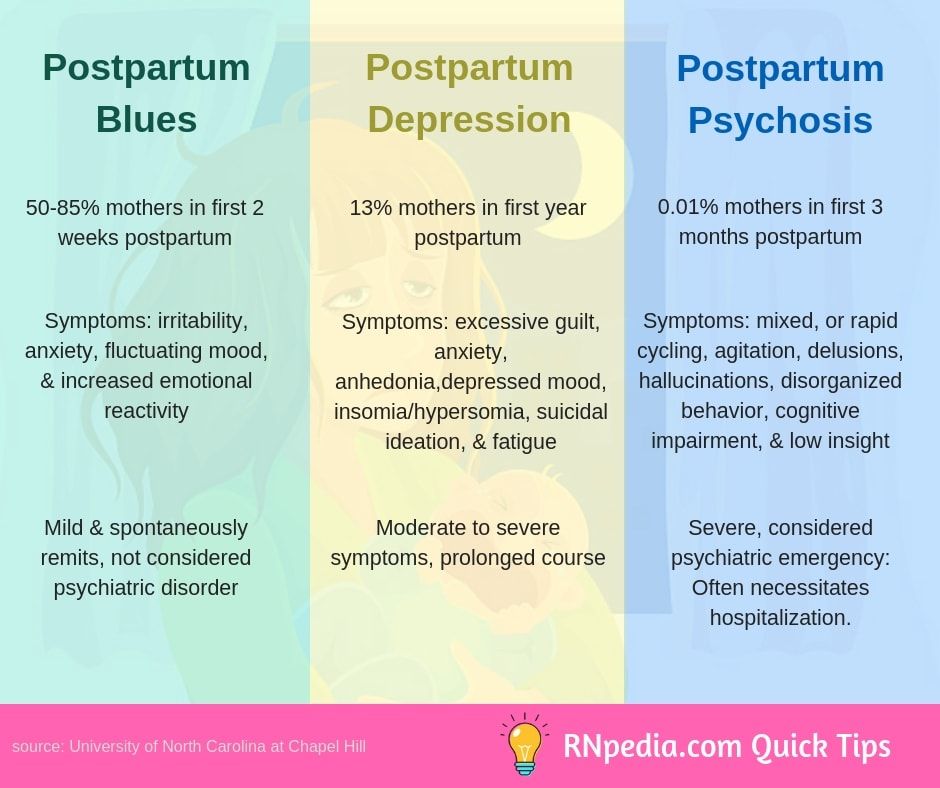

- Sex. Females with bipolar I disorder have a high risk for postpartum mania and psychosis.

- Hormones. Since psychosis has been associated with both childbirth and early signs occurring during puberty, hormones may play a role in developing bipolar disorder psychosis.

- Cannabis. Cannabis is the most frequently used drug among those diagnosed with bipolar disorder. What’s more, some research suggests that the frequency of cannabis use increases in proportion to the risk for psychotic disorders.

- Genetic differences. It’s been suggested there may be some genetic differences present in both people with schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.

People who have experienced bipolar disorder psychosis report a holistic approach as the most effective.

This means your treatment might benefit from including:

- Monitoring psychosis on a planner or calendar, and noting your setting, diet, and events before and after the episode.

- Having an accountability partner or support group to advise if you’re at the onset of an episode, or think you may be in the middle of one. Keep your treatment team in this loop as well.

- Avoiding alcohol, which is known to intensify everyday bipolar disorder symptoms and possibly be a trigger for mania and psychosis.

- Developing a routine for wellness that includes consistent sleep, taking medications as prescribed, a whole food diet, and healthy social time.

- Keeping space for your favorite activities that help you stay grounded like a custom playlist, movie, exercise, or what usually gets you laughing.

These strategies are recommended alongside the following formal treatments:

- Prescriptions: Your doctor may prescribe mood stabilizers, antidepressants, or antipsychotic medications.

- Psychotherapy: Therapy may include one-on-one counseling, family therapy and education, group therapy, or peer support.

- Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT): You may be offered ECT when medication and psychotherapy don’t lessen psychosis. It’s an outpatient procedure utilized to “reboot” the brain.

It’s not unusual for people to have only one episode of psychosis and recover with treatment. Early diagnosis and creating a treatment plan are important to manage your symptoms and improve quality of life.

Bipolar disorder and psychosis aren’t yet curable, but they’re both treatable. For many people, symptoms can be managed successfully so you can live well and fully.

If a friend or loved one is experiencing psychosis, there are also ways to effectively help them and communicate when they’re having an episode.

How to communicate with someone experiencing psychosis

Do:

- mirror the same language they use to describe their experience

- speak clearly and in short sentences

- actively listen to validate their experience, but aim to redirect the conversation

- speak privately, without distractions, if possible

- accept if they don’t want to talk to you, but be available in case they change their mind

- be mindful if they’re distressed by the experience

Don’t:

- talk down to the person, challenge, or “egg on” a delusion or hallucination

- verbally or nonverbally judge, disapprove, or argue

- label with combative stereotypes like “crazy,” “psychotic,” “postal,” or “raging”

- try to touch or physically move the person

People with bipolar disorder may experience episodes of psychosis, but thankfully, both psychosis and bipolar disorder are treatable.

With tools, knowledge, and by working with your healthcare team, you can manage your condition and maintain well-being.

The Healthline FindCare tool can provide options in your area if you need help finding a therapist.

90,000 unpacking episodes of psychosis and bipolar disorderAdmin

Content

- Bipolar psychosis

- Symptoms of bipolar psychosis

- Migrations

- EXCENTIONALS AND IRRARENTY WITHOUTIONAL INFORMATIONS AND IRRARENTIONAL PLACES AND IRRARITIONAL INFORMATIONS AND IRRARTIONAL PLACES AND IRRARTIONAL INFORMATIONS AND IRRARTIONAL INFORMATIONS Types of psychosis

- Mood psychosis

- Incongruent mood psychosis

- Do we know what causes bipolar disorder psychosis?

- Treating psychosis in bipolar disorder

- Moving on from episodes of bipolar psychosis

- How to deal with the loss of a person with psychosis

- P:

- Not recommended:

- Psychosis is often described as contact with reality.

People experiencing episodes of psychosis often fail to recognize what is real in the world around them.

People experiencing episodes of psychosis often fail to recognize what is real in the world around them. Psychosis is a legal reality for some medical and mental conditions, including bipolar disorder. Fortunately, episodes of psychosis are treatable. If you know you are suffering from psychosis, you can prepare with treatment and coping strategies.

Bipolar psychosis

Psychosis is a symptom of a condition, not a disorder. People with psychosis may have hallucinations or delusions.

Occasionally, a person with bipolar disorder may experience symptoms of psychosis. This often occurs during a severe episode of mania or depression.

Although psychosis is often associated with psychiatric disorders such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, it can occur due to other diseases and causes.

Hallucinations and delusions can also result from:

- brain tumor or cyst

- dementia, including Alzheimer's disease

- neurological conditions such as epilepsy, Parkinson's disease and Huntington's disease

- HIV and other communicable infections sexually, which can affect the brain

- malaria

- multiple sclerosis (MS)

- stroke

Symptoms of bipolar psychosis

Psychosis in bipolar disorder can occur during manic or depressive episodes.

But it is more common during episodes of mania.

But it is more common during episodes of mania. Many people think that psychosis is a sudden, severe break from reality. But psychosis usually develops slowly.

Initial symptoms of psychosis include:

- reduced performance at work or school

- less attention to personal hygiene than usual

- difficulty communicating

- difficulty concentrating

- reduced social contact

- unreasonable suspicion of others

- less emotional expression

- anxiety in bipolar disorder

- :

- hallucinations

- delusions

- incoherent or irrational thoughts and speech

- lack of awareness

Hallucinations

When people hallucinate, they experience things that are not real to anyone but themselves. They may hear voices, see things that aren't there, or experience inexplicable sensations.

Hallucinations can involve all the senses.

Delusion

Delusion is the unshakable belief that something is not real, not true, or cannot happen.

People can have grandiose illusions. This means that they consider themselves invincible or have special abilities or talents. Delusions of grandeur often occur during episodes of mania in bipolar disorder.

If a person with bipolar disorder experiences depressive episodes, they may experience paranoid delusions. They may believe that someone wants to get their hands on them or their property.

Random or irrational thoughts and speech

People with psychosis often experience irrational thoughts. Their speech may be fast, incoherent, or difficult to understand. They may jump from topic to topic, losing their train of thought.

Lack of awareness

Many people with psychosis may not realize that their behavior does not correspond to what is actually happening.

They may not realize that their hallucinations or delusions are not real, or they may notice that other people do not experience them.

Types of psychosis

There are two types (or features) of psychosis in people with bipolar disorder: mood congruent and mood incongruent.

This means that the symptoms either heighten or reflect your mood before the manic or depressive episode (congruent) or contradict your mood (incongruent).

This means that the symptoms either heighten or reflect your mood before the manic or depressive episode (congruent) or contradict your mood (incongruent). Sometimes both functions may occur during the same episode.

Mood related psychosis

Most people with bipolar psychosis experience mood related symptoms. This means that the delusions or hallucinations reflect your mood, beliefs, or current episode of bipolar disorder (mania or depression).

For example, during a depressive episode you may feel guilty or inadequate. In a manic episode, megalomania may occur.

Incongruent mood psychosis

Symptoms that don't match your mood are inconsistent with your current mood.

This type of psychosis may involve hearing voices or thoughts, or believing others are controlling you. During a depressive episode, you may also not feel guilt or other negative thoughts that are typical of depression.

Mood mismatch may be more serious. Findings from an earlier study in 2007 showed that people with psychosis inconsistent with mood in bipolar disorder were more likely to need hospitalization.

Do we know what causes bipolar disorder psychosis?

The exact cause of psychosis in bipolar disorder is not fully understood. But we know some factors that may play a role in the development of psychosis:

- Lack of sleep. Sleep disturbances are associated with a lower overall quality of life in people with bipolar disorder and may cause worsening of symptoms.

- Sex. Women with bipolar I disorder are at high risk of developing postpartum mania and psychosis.

- Hormones. Since psychosis is associated with both childbirth and early signs during puberty, hormones may play a role in the development of psychosis in bipolar disorder.

- Cannabis. Cannabis is the most commonly used drug among those diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Moreover, some research suggests that the frequency of cannabis use increases in proportion to the risk of psychotic disorders.

- Genetic differences.

It has been suggested that there may be some genetic differences in both people with schizophrenia and people with bipolar disorder.

It has been suggested that there may be some genetic differences in both people with schizophrenia and people with bipolar disorder.

Treatment of psychosis in bipolar disorder

People who have experienced psychosis with bipolar disorder find an integrated approach to be the most effective.

This means that your treatment can benefit from the inclusion of:

- Monitor psychosis on a planner or calendar, noting the setting, diet, and events before and after the episode.

- Having an accountability partner or support group to let you know if you are at the beginning of the episode or think you might be in the middle. Keep your treatment group on this cycle as well.

- Avoid alcohol, which is known to exacerbate day-to-day symptoms of bipolar disorder and may be a trigger for mania and psychosis.

- Develop a wellness routine that includes consistent sleep, medication as prescribed, a whole food diet, and healthy time.

- Make room for your favorite activities that keep you connected, such as your own playlist, movie, exercise, or anything that usually makes you laugh.

These strategies are recommended along with the following formal treatments:

- Prescriptions: Your doctor may prescribe mood stabilizers, antidepressants, or neuroleptics.

- Psychotherapy: Therapy may include individual counseling, family therapy and education, group therapy, or peer support.

- Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT): You may be offered ECT if medication and psychotherapy do not improve psychosis. This is an outpatient procedure used to "reboot" the brain.

Moving on from episodes of bipolar psychosis

It is not uncommon for people to endure only one episode of psychosis and recover with treatment. Early diagnosis and creating a treatment plan are important to manage your symptoms and improve your quality of life.

Bipolar disorder and psychosis are not yet curable, but both are treatable. For many people, symptoms can be successfully controlled so you can live well and fully.

If a friend or loved one has psychosis, there are also ways to effectively help and communicate during an attack.

How to communicate with a person with psychosis

S:

- reflect the same language they use to describe their experience

- speak clearly and in short sentences

- listen actively to validate your experience but seek to redirect the conversation

- talk in private without distractions if possible

- agree if they don't want to talk to you, but be available if they change their mind

- be considerate if they are distressed by the experience

Not recommended: hallucination

- verbally or non-verbally judging, disapproving or arguing

- a label with militant stereotypes such as "crazy", "psychotic", "mail" or "rabid"

- try to touch or physically move the person

People with bipolar disorder can experience episodes of psychosis, but fortunately, both psychosis and bipolar disorder are treatable.

With the help of tools, knowledge and cooperation with your doctor, you can manage your condition and maintain good health.

The Drink-Drink FindCare tool can provide options in your area if you need help finding a therapist.

HealthSchizophrenia in children, treatment of manic depressive psychosis at IsraClinic

There are several forms of childhood schizophrenia, almost all of which are acutely progressive and have negative symptoms. In Israel, specialists always check the diagnosis made in the CIS countries - often signs of a disease diagnosed as schizophrenia can be symptoms of other, less serious mental disorders. Accordingly, a thorough diagnosis helps to make an accurate diagnosis and prescribe effective treatment.

Submit an application for diagnosis and treatment

I confirm that I accept the terms of consent to the processing of personal data.

According to Russian statistics, schizophrenia manifests itself very rarely in children (1.

66 per 1000 children from 0 to 14 years old), but when it occurs, it can cause irreparable harm to the development of the child, significantly slowing down or distorting it, radically changing the personality of the baby and his attitude to the world. Most often in children, schizophrenia occurs after the age of seven, very rarely at an earlier age. The causes of schizophrenia in children are not fully understood. Among the most common causes of schizophrenia in children are brain anomalies and a genetic factor; less often, intoxication, trauma, or a serious illness become the cause of early manifestation.

66 per 1000 children from 0 to 14 years old), but when it occurs, it can cause irreparable harm to the development of the child, significantly slowing down or distorting it, radically changing the personality of the baby and his attitude to the world. Most often in children, schizophrenia occurs after the age of seven, very rarely at an earlier age. The causes of schizophrenia in children are not fully understood. Among the most common causes of schizophrenia in children are brain anomalies and a genetic factor; less often, intoxication, trauma, or a serious illness become the cause of early manifestation. Factors provoking the disorder

It should be noted right away that the exact, final cause of childhood schizophrenia has not yet been clarified, and presumable ones can be defined as combined. Both biological and social factors play a role here. Among the biological predisposing factors, first of all, genetics and heredity are distinguished.

It has been established that most of the children suffering from the disorder have sick relatives, close or even secondary. Biological causes also include damage to the central nervous system. Damage to the structure of the brain plays an important role in the manifestation of the disorder. They are divided into perinatal and postnatal. Perinatal risk factors are defects born in the womb. They can develop due to:

It has been established that most of the children suffering from the disorder have sick relatives, close or even secondary. Biological causes also include damage to the central nervous system. Damage to the structure of the brain plays an important role in the manifestation of the disorder. They are divided into perinatal and postnatal. Perinatal risk factors are defects born in the womb. They can develop due to: - intrauterine fetal hypoxia;

- intrauterine infections;

- placental abruption;

- lack of nutrition;

- toxic effects on the fetus - mother's abuse of alcohol, drugs during pregnancy; taking medications prohibited for pregnant women; if the pregnant woman was exposed to toxic substances.

Postnatal risk factors are those that affect the baby after birth. Traumatic brain injuries play a special role here. This group also includes neuroinfections, that is, infections that destroy brain tissue: encephalitis, meningitis, neurosyphilis.

Conditions that cause brain hypoxia predispose to the development of the disease. But all these reasons may be powerless if the child is surrounded by a prosperous social environment. The risk appears if the child grows up and is brought up in an unfriendly, oppressive atmosphere. This applies to violence to which the baby is exposed: beatings, aggression from parents, systematic accusations, inadequate assessment of actions. Often, child abuse is manifested in families where parents are drug addicts or abuse alcohol. Another model of behavior is when parents raise their child in excessive severity, make excessive demands on him, dictate their preferences, and establish increased control. That is, education from the cycle: "a step to the left, a step to the right - execution." In another family, the child seems to live and be brought up according to the rules, but the relationship between the parents does not add up. Constant quarrels, scandals, misunderstandings between spouses leave a negative imprint on the child's psyche, especially if he becomes a witness to violence.

Conditions that cause brain hypoxia predispose to the development of the disease. But all these reasons may be powerless if the child is surrounded by a prosperous social environment. The risk appears if the child grows up and is brought up in an unfriendly, oppressive atmosphere. This applies to violence to which the baby is exposed: beatings, aggression from parents, systematic accusations, inadequate assessment of actions. Often, child abuse is manifested in families where parents are drug addicts or abuse alcohol. Another model of behavior is when parents raise their child in excessive severity, make excessive demands on him, dictate their preferences, and establish increased control. That is, education from the cycle: "a step to the left, a step to the right - execution." In another family, the child seems to live and be brought up according to the rules, but the relationship between the parents does not add up. Constant quarrels, scandals, misunderstandings between spouses leave a negative imprint on the child's psyche, especially if he becomes a witness to violence.

Signs of schizophrenia in children under 7 years old

In especially severe cases, mental developmental problems are noticeable in infants and children of the first years of life. A focused gaze that is not characteristic of infants, leaving the feeling that the child is looking at something that is not visible to adults. Sometimes the baby does not react and does not follow with his eyes a rattle or other thing that is moved in front of his face. These children sleep poorly, they have an increased reaction to loud noises or bright lights, they are lethargic and often cry. Children suffering from schizophrenia from an early age have delays in the development of speech and fine motor skills. In 75% of cases, children with schizophrenia diagnosed as early as the age of seven had developmental delays in early childhood. In children, one of the signs of schizophrenia in early childhood is the incorrect formation of play activities. The child prefers monotonous play that gives the impression of being obsessed with one or more objects or activities.

Schizophrenia in children is manifested by a violation of interpersonal relationships, lack of attachment to parents or other significant adults. A distinctive feature of children with schizophrenia is aggression, which manifests itself from the first years of life. Such children are slow and awkward, but at the same time excitable tend to scream and tantrum. All these signs increase with age, and by the age of three or four, schizophrenia has developed to such a stage that its characteristic symptoms are visible. It is worth noting that schizophrenia, which began in early childhood or infancy, always proceeds in severe forms, and leads to significant defects in the intellectual sphere. This is due to a violation of cognitive activity, which is only formed in early childhood.

Schizophrenia in children is manifested by a violation of interpersonal relationships, lack of attachment to parents or other significant adults. A distinctive feature of children with schizophrenia is aggression, which manifests itself from the first years of life. Such children are slow and awkward, but at the same time excitable tend to scream and tantrum. All these signs increase with age, and by the age of three or four, schizophrenia has developed to such a stage that its characteristic symptoms are visible. It is worth noting that schizophrenia, which began in early childhood or infancy, always proceeds in severe forms, and leads to significant defects in the intellectual sphere. This is due to a violation of cognitive activity, which is only formed in early childhood. Symptoms of schizophrenia in children

The clinical picture of schizophrenia in children is represented by symptoms of regression, dissociative dysontogenesis, asynchronous development of mental functions, catatonic disorders.

Delusion is manifested rudimentary - fears, obsessions. Schizophrenia in children of early and younger age is accompanied by a decrease in activity, an increase in apathy, indifference to games, favorite activities. There is a desire to protect themselves from others. The child becomes withdrawn, prefers to be alone, refuses to spend time together. The repetition of monotonous actions is characteristic: walking around the perimeter of the room, shifting toys, shading with a pencil. Impulsive behavior, emotional instability is manifested by causeless crying, laughter. Frequent mood swings do not depend on the external situation. In preschoolers, schoolchildren, distortions of perception, qualitative disorders of thinking are determined. Crazy ideas are expressed by children on their own, determined through the inadequacy of behavior. Pathological concepts are rudimentary or have a complex system of pathological causal relationships. The delirium of relationship, persecution, parental substitution prevails.

Delusion is manifested rudimentary - fears, obsessions. Schizophrenia in children of early and younger age is accompanied by a decrease in activity, an increase in apathy, indifference to games, favorite activities. There is a desire to protect themselves from others. The child becomes withdrawn, prefers to be alone, refuses to spend time together. The repetition of monotonous actions is characteristic: walking around the perimeter of the room, shifting toys, shading with a pencil. Impulsive behavior, emotional instability is manifested by causeless crying, laughter. Frequent mood swings do not depend on the external situation. In preschoolers, schoolchildren, distortions of perception, qualitative disorders of thinking are determined. Crazy ideas are expressed by children on their own, determined through the inadequacy of behavior. Pathological concepts are rudimentary or have a complex system of pathological causal relationships. The delirium of relationship, persecution, parental substitution prevails. The older the child, the more pronounced the incoherence of the thinking process, the slippage to secondary signs of objects and events, the fragmentary thoughts. The child is unable to maintain a conversation on a given topic, due to insufficient focus, randomness of associations, speech becomes “broken”, there are no logical connections. The distortion of perception leads to the development of hallucinations. Emotions become impoverished, flattened. The inadequacy of affect is manifested by indifference to the problems of close people (illnesses, partings, death), violent reactions of suffering, happiness in relation to strangers, animals. Children can be goofy, emotionally "cold", euphoric or depressed for no reason. Over time, movements lose their smoothness, posture, posture become disharmonious, the face becomes “mask-like”.

The older the child, the more pronounced the incoherence of the thinking process, the slippage to secondary signs of objects and events, the fragmentary thoughts. The child is unable to maintain a conversation on a given topic, due to insufficient focus, randomness of associations, speech becomes “broken”, there are no logical connections. The distortion of perception leads to the development of hallucinations. Emotions become impoverished, flattened. The inadequacy of affect is manifested by indifference to the problems of close people (illnesses, partings, death), violent reactions of suffering, happiness in relation to strangers, animals. Children can be goofy, emotionally "cold", euphoric or depressed for no reason. Over time, movements lose their smoothness, posture, posture become disharmonious, the face becomes “mask-like”. Prognosis of schizophrenia

The prognosis depends on the form of the disorder. With the malignant development of the disease, a continuous course after 2-3 years, mental functions disintegrate, severe defects are formed, sometimes - a fatal outcome due to severe exhaustion.

In the asthenic form of the flow, a violation of the ability to navigate in space, dependence on others are characteristic, symptoms of autism appear. Children with a depressive form are often in a depressed mood, prone to suspicion, suspiciousness, and severe anxiety. Violations, however, are often less pronounced, although social adaptation is difficult. Often there are symptoms of psychosis. Patients often commit crimes. The risk of suicide is also high.

In the asthenic form of the flow, a violation of the ability to navigate in space, dependence on others are characteristic, symptoms of autism appear. Children with a depressive form are often in a depressed mood, prone to suspicion, suspiciousness, and severe anxiety. Violations, however, are often less pronounced, although social adaptation is difficult. Often there are symptoms of psychosis. Patients often commit crimes. The risk of suicide is also high. Forms of schizophrenia in children, treatment

- Malignant schizophrenia, manifests at an early age (up to 7 years), its peculiarity is the promotion of negative symptoms, while within 1-2 years after the onset of the disease, a stop or regression defect is observed in mental development. The child stops walking, begins to move on all fours, stops talking, communicating, only makes inarticulate sounds, enuresis resumes, in general, his behavior resembles the habits of an animal.

- Paranoid schizophrenia occurs in children from 10 to 12 years old, characterized by fears, fantasies, delusions of poisoning or persecution, aggression is directed primarily against parents and people who love and care for them.

- Sluggish schizophrenia is the most common form of the disease in children, initially it can manifest itself through the super-rapid development of some mental functions: abstract thinking, musical abilities, etc., but over time, development is inhibited, and fears, fantasies, abstruse interests are also among the productive symptoms .

- The paroxysmal-progredient form is manifested by seizures with mild emotional manifestations, fears, delirium. As a result of the development of this form of the disease, an oligophrenic-like defect appears (a defect in the development of the intellect).

- Recurrent schizophrenia is characterized by unreasonable fears, fever, vegetative crises, and occurs very rarely in children.

Diagnosis and treatment of schizophrenia in children

Due to the age of the patient, parents should carefully monitor the development of the child, and if there is the slightest suspicion that something is going wrong, immediately contact the clinic.