Mixed mood state

Mixed Bipolar Disorder Symptoms, Causes, and Treatments

Written by Matthew Hoffman, MD

In this Article

- What Are Mixed Episodes in Bipolar Disorder?

- Who Gets Mixed Bipolar Episodes?

- What Are the Symptoms of a Mixed Features Episode?

- What Are the Risks of Mixed Features During Mood Episodes of Bipolar Disorder?

- What Are the Treatments for Mood Episodes With Mixed Features in Bipolar Disorder?

What Are Mixed Episodes in Bipolar Disorder?

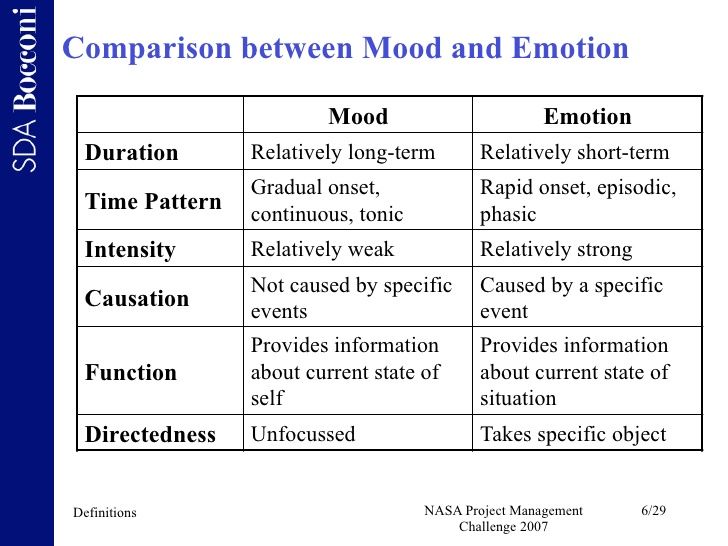

Mixed features refers to the presence of high and low symptoms occurring at the same time, or as part of a single episode, in people experiencing an episode of mania or depression. In most forms of bipolar disorder, moods alternate between elevated and depressed over time. A person with mixed features experiences symptoms of both mood "poles" -- mania and depression -- simultaneously or in rapid sequence.

Who Gets Mixed Bipolar Episodes?

Virtually anyone can develop bipolar disorder. About 2.5% of the U.S. population -- nearly 6 million people -- has some form of bipolar disorder.

Mixed episodes are common in people with bipolar disorder -- half or more of people with bipolar disorder have at least some mania symptoms during a full episode of depression. Those who develop bipolar disorder at a younger age, particularly in adolescence, may be more likely to have mixed episodes. People who develop episodes with mixed features may also develop "pure" depressed or "pure" manic or hypomanic phases of bipolar illness. People who have episodes of major depression but not full episodes of mania or hypomania also can sometimes have low-grade mania symptoms. These are symptoms that are not severe or extensive enough to be classified as bipolar disorder. This is referred to as an episode of "mixed depression" or a unipolar (major) depressive episode with mixed features.

Most people are in their teens or early 20s when symptoms from bipolar disorder first start. It is rare for bipolar disorder to develop for the first time after age 50. People who have an immediate family member with bipolar are at higher risk.

It is rare for bipolar disorder to develop for the first time after age 50. People who have an immediate family member with bipolar are at higher risk.

What Are the Symptoms of a Mixed Features Episode?

Mixed episodes are defined by symptoms of mania and depression that occur at the same time or in rapid sequence without recovery in between..

- Mania with mixed features usually involves irritability, high energy, racing thoughts and speech, and overactivity or agitation.

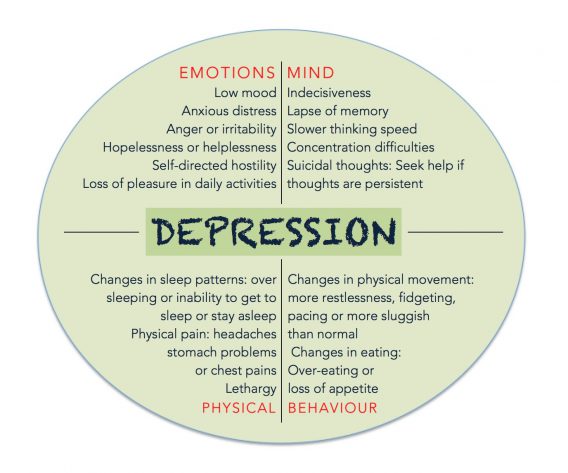

- Depression during episodes with mixed features involves the same symptoms as in "regular" depression, with feelings of sadness, loss of interest in activities, low energy, feelings of guilt and worthlessness, and thoughts of suicide.

This may seem impossible. How can someone be manic and depressed at the same time? The high energy of mania with the despair of depression are not mutually exclusive symptoms, and their co-occurrence may be much more common than people realize.

For example, a person in an episode with mixed features could be crying uncontrollably while announcing they have never felt better in their life. Or they could be exuberantly happy, only to suddenly collapse in misery. A short while later they might suddenly return to an ecstatic state.

Mood episodes with mixed features can last from days to weeks or sometimes months if untreated. They may recur ,and recovery can be slower than during episodes of "pure" bipolar depression or "pure" mania or hypomania.

What Are the Risks of Mixed Features During Mood Episodes of Bipolar Disorder?

The most serious risk of mixed features during a manic or depressive episode is suicide. People with bipolar disorder are 10 to 20 times more likely to commit suicide than people without bipolar disorder. Tragically, as many as 10% to 15% of people with bipolar disorder eventually lose their lives to suicide.

Evidence shows that during episodes with mixed features, people may be at even higher risk for suicide than people in episodes of bipolar depression.

Treatment reduces the likelihood of serious depression and suicide. Lithium (Eskalith, Lithobid) in particular, taken long term, may help to reduce the risk of suicide.

People with bipolar disorder are also at higher risk for substance abuse. Nearly 60% of people with bipolar disorder abuse drugs or alcohol. Substance abuse is associated with more severe or poorly controlled bipolar disorder.

What Are the Treatments for Mood Episodes With Mixed Features in Bipolar Disorder?

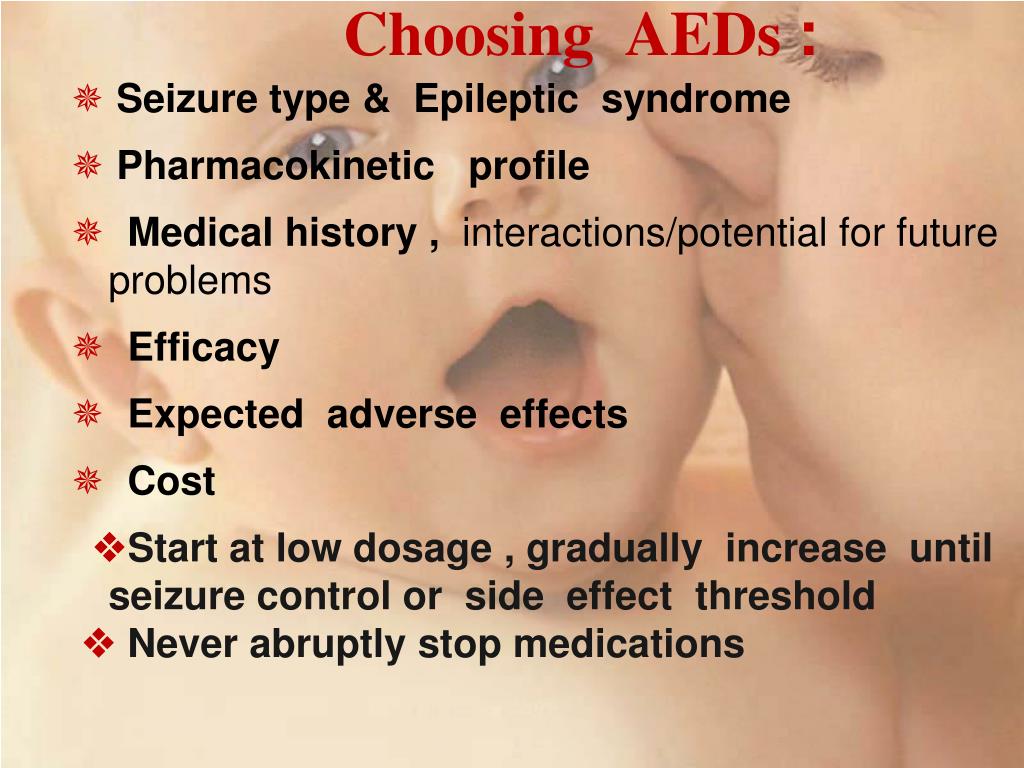

Manic or depressive episodes with mixed features generally require treatment with medication. Unfortunately, such episodes are more difficult to control than an episode of pure mania or depression. The main drugs used to treat episodes with mixed features are mood stabilizers and antipsychotics.

Mood Stabilizers

While lithium is often considered a gold standard treatment for mania, it may be less effective when mania and depression occur simultaneously, as in a manic episode with mixed features. Lithium has been used for more than 60 years to treat bipolar disorder. It can take weeks to work fully, making it better for maintenance treatment than for acute manic episodes. Blood levels of lithium and other lab test results must be monitored to avoid side effects.

Lithium has been used for more than 60 years to treat bipolar disorder. It can take weeks to work fully, making it better for maintenance treatment than for acute manic episodes. Blood levels of lithium and other lab test results must be monitored to avoid side effects.

Valproic acid (Depakote) is an antiseizure medication that also levels out moods in bipolar disorder. It has a more rapid onset of action, and in some studies has been shown to be more effective than lithium for the treatment of manic episodes with mixed features.

Some other antiseizure drugs, such as and carbamazepine (Tegretol) and lamotrigine (Lamictal), are also effective mood stabilizers.

Antipsychotics

Many atypical antipsychotic drugs are effective FDA-approved treatments for manic episodes with mixed features. These includearipiprazole (Abilify), asenapine (Saphris), cariprazine (Vraylar), olanzapine (Zyprexa), quetiapine (Seroquel), risperidone (Risperdal), and ziprasidone (Geodon). Antipsychotic drugs are also sometimes used alone or in combination with mood stabilizers for preventive treatment.

Antipsychotic drugs are also sometimes used alone or in combination with mood stabilizers for preventive treatment.

Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT)

Despite its frightening reputation, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an effective treatment for any phase of bipolar disorder, including manic episodes with mixed features. ECT can be helpful if medication fails or can't be used.

Treatment for Depression in Mixed Bipolar Disorder

Common antidepressants such as fluoxetine (Prozac, Sarafem), paroxetine (Paxil), and sertraline (Zoloft) have been shown to worsen mania symptoms without necessarily improving depressive symptoms when depressive and manic symptoms occur together. Most experts therefore advise against using antidepressants during episodes with mixed features. Mood stabilizers (particularly Depakote), as well as atypical antipsychotic drugs, are considered the first-line treatments for mood episodes with mixed features.

Bipolar disorder usually involves recurrences of mixed, manic, or depressed phases of illness. Therefore, it is usually recommended that medications be continued in an ongoing fashion after an acute episode resolves in order to prevent relapses. This is sometimes called maintenance treatment.

Therefore, it is usually recommended that medications be continued in an ongoing fashion after an acute episode resolves in order to prevent relapses. This is sometimes called maintenance treatment.

Bipolar Disorder Guide

- Overview

- Symptoms & Types

- Treatment & Prevention

- Living & Support

Mixed States in Bipolar Disorder: Etiology, Pathogenesis and Treatment

1. Trede K, Salvatore P, Baethge C, Gerhard A, Maggini C, Baldessarini RJ. Manic-depressive illness: evolution in Kraepelin's textbook, 1883-1926. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2005;13:155–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Verdolini N, Agius M, Ferranti L, Moretti P, Piselli M, Quartesan R. The state of the art of the DSM-5 “with mixed features” specifier. ScientificWorldJournal. 2015;2015:757258. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. McIntyre RS, Soczynska JK, Cha DS, Woldeyohannes HO, Dale RS, Alsuwaidan MT, et al. The prevalence and illness characteristics of DSM-5-defined “mixed feature specifier” in adults with major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder: results from the International Mood Disorders Collaborative Project. J Affect Disord. 2015;172:259–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

The prevalence and illness characteristics of DSM-5-defined “mixed feature specifier” in adults with major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder: results from the International Mood Disorders Collaborative Project. J Affect Disord. 2015;172:259–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Vieta E, Valentí M. Mixed states in DSM-5: implications for clinical care, education, and research. J Affect Disord. 2013;148:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Shim IH, Woo YS, Bahk WM. Prevalence rates and clinical implications of bipolar disorder “with mixed features” as defined by DSM-5. J Affect Disord. 2015;173:120–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Fagiolini A, Coluccia A, Maina G, Forgione RN, Goracci A, Cuomo A, et al. Diagnosis, epidemiology and management of mixed states in bipolar disorder. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:725–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Tundo A, Musetti L, Benedetti A, Berti B, Massimetti G, Dell’Osso L. Onset polarity and illness course in bipolar I and II disorders: the predictive role of broadly defined mixed states. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;63:15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Compr Psychiatry. 2015;63:15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Palma M, Ferreira B, Borja-Santos N, Trancas B, Monteiro C, Cardoso G. Efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy in bipolar disorder with mixed features. Depress Res Treat. 2016;2016:8306071. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Muneer A. Staging models in bipolar disorder: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2016;14:117–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Fornaro M, De Berardis D, Koshy AS, Perna G, Valchera A, Vancampfort D, et al. Prevalence and clinical features associated with bipolar disorder polypharmacy: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:719–735. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Smolensky MH, Hermida RC, Reinberg A, Sackett-Lundeen L, Portaluppi F. Circadian disruption: New clinical perspective of disease pathology and basis for chronotherapeutic intervention. Chronobiol Int. 2016;33:1101–1119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Bechtel W. Circadian rhythms and mood disorders: are the phenomena and mechanisms causally related? Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bechtel W. Circadian rhythms and mood disorders: are the phenomena and mechanisms causally related? Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Wang B, Chen D. Evidence for seasonal mania: a review. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19:301–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Milhiet V, Boudebesse C, Bellivier F, Drouot X, Henry C, Leboyer M, et al. Circadian abnormalities as markers of susceptibility in bipolar disorders. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2014;6:120–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Moreira J, Geoffroy PA. Lithium and bipolar disorder: impacts from molecular to behavioural circadian rhythms. Chronobiol Int. 2016;33:351–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Lee HJ, Son GH, Geum D. Circadian rhythm hypotheses of mixed features, antidepressant treatment resistance, and manic switching in bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Investig. 2013;10:225–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Gustafson CL, Partch CL. Emerging models for the molecular basis of mammalian circadian timing. Biochemistry. 2015;54:134–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Biochemistry. 2015;54:134–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Landgraf D, McCarthy MJ, Welsh DK. Circadian clock and stress interactions in the molecular biology of psychiatric disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16:483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Bauer M, Beaulieu S, Dunner DL, Lafer B, Kupka R. Rapid cycling bipolar disorder--diagnostic concepts. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:153–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Young JW, Dulcis D. Investigating the mechanism(s) underlying switching between states in bipolar disorder. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;759:151–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Koszewska I, Rybakowski JK. Antidepressant-induced mood conversions in bipolar disorder: a retrospective study of tricyclic versus non-tricyclic antidepressant drugs. Neuropsychobiology. 2009;59:12–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Leverich GS, Altshuler LL, Frye MA, Suppes T, McElroy SL, Keck PE, Jr, et al. Risk of switch in mood polarity to hypomania or mania in patients with bipolar depression during acute and continuation trials of venlafaxine, sertraline, and bupropion as adjuncts to mood stabilizers. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:232–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:232–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Post RM, Altshuler LL, Leverich GS, Frye MA, Nolen WA, Kupka RW, et al. Mood switch in bipolar depression: comparison of adjunctive venlafaxine, bupropion and sertraline. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:124–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Santangelo G, Barone P, Trojano L, Vitale C. Pathological gambling in Parkinson’s disease. A comprehensive review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2013;19:645–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Vaughan RA, Foster JD. Mechanisms of dopamine transporter regulation in normal and disease states. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2013;34:489–496. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. van Enkhuizen J, Janowsky DS, Olivier B, Minassian A, Perry W, Young JW, et al. The catecholaminergic-cholinergic balance hypothesis of bipolar disorder revisited. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;753:114–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Anand A, Darnell A, Miller HL, Berman RM, Cappiello A, Oren DA, et al. Effect of catecholamine depletion on lithium-induced long-term remission of bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:972–978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Effect of catecholamine depletion on lithium-induced long-term remission of bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:972–978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Hannestad JO, Cosgrove KP, DellaGioia NF, Perkins E, Bois F, Bhagwagar Z, et al. Changes in the cholinergic system between bipolar depression and euthymia as measured with [123I]5IA single photon emission computed tomography. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:768–776. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Saricicek A, Esterlis I, Maloney KH, Mineur YS, Ruf BM, Muralidharan A, et al. Persistent β2*-nicotinic acetylcholinergic receptor dysfunction in major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:851–859. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. McIntyre RS, Cha DS, Kim RD, Mansur RB. A review of FDA-approved treatment options in bipolar depression. CNS Spectr. 2013;18(Suppl 1):4–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. McGirr A, Berlim MT, Bond DJ, Fleck MP, Yatham LN, Lam RW. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of ketamine in the rapid treatment of major depressive episodes. Psychol Med. 2015;45:693–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychol Med. 2015;45:693–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. van Enkhuizen J, Minassian A, Young JW. Further evidence for ClockΔ19 mice as a model for bipolar disorder mania using cross-species tests of exploration and sensorimotor gating. Behav Brain Res. 2013;249:44–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Abreu T, Bragança M. The bipolarity of light and dark: a review on bipolar disorder and circadian cycles. J Affect Disord. 2015;185:219–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Levenson JC, Wallace ML, Anderson BP, Kupfer DJ, Frank E. Social rhythm disrupting events increase the risk of recurrence among individuals with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17:869–879. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Akhter A, Fiedorowicz JG, Zhang T, Potash JB, Cavanaugh J, Solomon DA, et al. Seasonal variation of manic and depressive symptoms in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15:377–384. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Sit D, Wisner KL, Hanusa BH, Stull S, Terman M. Light therapy for bipolar disorder: a case series in women. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:918–927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Light therapy for bipolar disorder: a case series in women. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:918–927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Geoffroy PA, Bellivier F, Scott J, Etain B. Seasonality and bipolar disorder: a systematic review, from admission rates to seasonality of symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2014;168:210–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Lee HJ, Woo HG, Greenwood TA, Kripke DF, Kelsoe JR. A genome-wide association study of seasonal pattern mania identifies NF1A as a possible susceptibility gene for bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;145:200–207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Nievergelt CM, Kripke DF, Barrett TB, Burg E, Remick RA, Sadovnick AD. Suggestive evidence for association of the circadian genes PERIOD3 and ARNTL with bipolar disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006;141B:234–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. McClung CA. How might circadian rhythms control mood? Let me count the ways. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:242–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Roybal K, Theobold D, Graham A, DiNieri JA, Russo SJ, Krishnan V, et al. Mania-like behavior induced by disruption of CLOCK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6406–6411. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Del'Guidice T, Latapy C, Rampino A, Khlghatyan J, Lemasson M, Gelao B, et al. FXR1P is a GSK3β substrate regulating mood and emotion processing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E4610–E4619. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Mukherjee S, Coque L, Cao JL, Kumar J, Chakravarty S, Asaithamby A, et al. Knockdown of Clock in the ventral tegmental area through RNA interference results in a mixed state of mania and depression-like behavior. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:503–511. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Sidor MM, Spencer SM, Dzirasa K, Parekh PK, Tye KM, Warden MR, et al. Daytime spikes in dopaminergic activity drive rapid mood-cycling in mice. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:1406–1419. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Clemente AS, Diniz BS, Nicolato R, Kapczinski FP, Soares JC, Firmo JO, et al. Bipolar disorder prevalence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2015;37:155–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Muneer A. Pharmacotherapy of acute bipolar depression in adults: an evidence based approach. Korean J Fam Med. 2016;37:137–148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Ostergaard SD, Bertelsen A, Nielsen J, Mors O, Petrides G. The association between psychotic mania, psychotic depression and mixed affective episodes among 14,529 patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;147:44–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Seo HJ, Wang HR, Jun TY, Woo YS, Bahk WM. Factors related to suicidal behavior in patients with bipolar disorder: the effect of mixed features on suicidality. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;39:91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Carvalho AF, Dimellis D, Gonda X, Vieta E, Mclntyre RS, Fountoulakis KN. Rapid cycling in bipolar disorder: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75:e578–e586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rapid cycling in bipolar disorder: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75:e578–e586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Fornaro M, Stubbs B, De Berardis D, Perna G, Valchera A, Veronese N, et al. Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of acute bipolar depression with mixed features: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis of placebo-controlled clinical trials. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Chue P, Chue J. A critical appraisal of paliperidone long-acting injection in the treatment of schizoaffective disorder. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2016;12:109–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Devanand DP, Polanco P, Cruz R, Shah S, Paykina N, Singh K, et al. The efficacy of ECT in mixed affective states. J ECT. 2000;16:32–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Singh V, Bowden CL, Mintz J. Relative effectiveness of adjunctive risperidone on manic and depressive symptoms in mixed mania. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;28:91–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2013;28:91–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Macfadden W, Adler CM, Turkoz I, Haskins JT, Turner N, Alphs L. Adjunctive long-acting risperidone in patients with bipolar disorder who relapse frequently and have active mood symptoms. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Tohen M, McIntyre RS, Kanba S, Fujikoshi S, Katagiri H. Efficacy of olanzapine in the treatment of bipolar mania with mixed features defined by DSM-5. J Affect Disord. 2014;168:136–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Vieta E, Suppes T, Ekholm B, Udd M, Gustafsson U. Long-term efficacy of quetiapine in combination with lithium or divalproex on mixed symptoms in bipolar I disorder. J Affect Disord. 2012;142:36–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Muneer A. Pharmacotherapy of bipolar disorder with quetiapine: a recent literature review and an update. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13:25–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Warrington L, Lombardo I, Loebel A, Ice K. Ziprasidone for the treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar disorder. CNS Drugs. 2007;21:835–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ziprasidone for the treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar disorder. CNS Drugs. 2007;21:835–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Patkar AA, Pae CU, Vöhringer PA, Mauer S, Narasimhan M, Dalley S, et al. A 13-week, randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial of ziprasidone in bipolar spectrum disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35:319–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Vita A, De Peri L, Siracusano A, Sacchetti E ATOM Group. Efficacy and tolerability of asenapine for acute mania in bipolar I disorder: meta-analyses of randomized-controlled trials. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;28:219–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Sawyer L, Azorin JM, Chang S, Rinciog C, Guiraud-Diawara A, Marre C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of asenapine in the treatment of bipolar I disorder patients with mixed episodes. J Med Econ. 2014;17:508–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. McIntyre RS, Cucchiaro J, Pikalov A, Kroger H, Loebel A. Lurasidone in the treatment of bipolar depression with mixed (subsyndromal hypomanic) features: post hoc analysis of a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:398–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:398–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Muneer A. The treatment of adult bipolar disorder with aripiprazole: a systematic review. Cureus. 2016;8:e562. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Ketter TA, Miller S, Dell’Osso B, Wang PW. Treatment of bipolar disorder: Review of evidence regarding quetiapine and lithium. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:256–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Cipriani A, Reid K, Young AH, Macritchie K, Geddes J. Valproic acid, valproate and divalproex in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(10):CD003196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Weisler RH, Hirschfeld R, Cutler AJ, Gazda T, Ketter TA, Keck PE, et al. Extended-release carbamazepine capsules as monotherapy in bipolar disorder: pooled results from two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. CNS Drugs. 2006;20:219–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Vasudev A, Macritchie K, Vasudev K, Watson S, Geddes J, Young AH. Oxcarbazepine for acute affective episodes in bipolar disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(12):CD004857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Oxcarbazepine for acute affective episodes in bipolar disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(12):CD004857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Grunze H, Kotlik E, Costa R, Nunes T, Falcão A, Almeida L, et al. Assessment of the efficacy and safety of eslicarbazepine acetate in acute mania and prevention of recurrence: experience from multicentre, double-blind, randomised phase II clinical studies in patients with bipolar disorder I. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:70–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Amann B, Born C, Crespo JM, Pomarol-Clotet E, McKenna P. Lamotrigine: when and where does it act in affective disorders? A systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25:1289–1294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Vieta E, Sánchez-Moreno J, Goikolea JM, Colom F, Martínez-Arán A, Benabarre A, et al. Effects on weight and outcome of long-term olanzapine-topiramate combination treatment in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:374–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Bialer M. Why are antiepileptic drugs used for nonepileptic conditions? Epilepsia. 2012;53(Suppl 7):26–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Why are antiepileptic drugs used for nonepileptic conditions? Epilepsia. 2012;53(Suppl 7):26–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Medda P, Toni C, Perugi G. The mood-stabilizing effects of electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT. 2014;30:275–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mixed affective states in adolescence (historical aspect, current state of the problem, psychopathology)

Until now, one of the most controversial and controversial in the field of affective pathology remains the problem of mixed affective states. More than 100 years have passed since their first clinical descriptions appeared in the scientific psychiatric literature, but even today there are ongoing discussions regarding the content of the concept of "mixed affective states", their boundaries have not been clarified, there is no agreement regarding their nosological belonging to the group affective disorders, there is no unambiguous understanding of the mechanisms of their formation, there is no complete clarity in assessing the prognosis of these disorders and the characteristics of therapeutic tactics. These difficulties increase when trying to assess mixed affective states that are formed with the participation of an additional pathogenetic factor - age, which has a powerful influence on the clinical and psychopathological manifestations of mixed disorders that manifest during age-related crises, including in adolescence and adolescence. The relevance of studying mixed states in adolescence is also due to their extremely high suicidal risk - up to 60% of patients with mixed states report suicidal intentions, and every second completed suicide in adolescent patients with bipolar disorder occurs in a mixed state. According to many researchers (C. Nunn [58]; R. Post et al. [63]; S. McElroy et al. [53-55]), the onset of an affective illness in adolescence is associated with a high degree of frequency with the dominance mixed states. According to J. Weckerly [66], mixed states in bipolar disease are observed in adolescents and young men in ⅓ of cases. B. Birmaher and D. Axelson [28] give prevalence rates of mixed states in the range of 38-66%, and according to B.

These difficulties increase when trying to assess mixed affective states that are formed with the participation of an additional pathogenetic factor - age, which has a powerful influence on the clinical and psychopathological manifestations of mixed disorders that manifest during age-related crises, including in adolescence and adolescence. The relevance of studying mixed states in adolescence is also due to their extremely high suicidal risk - up to 60% of patients with mixed states report suicidal intentions, and every second completed suicide in adolescent patients with bipolar disorder occurs in a mixed state. According to many researchers (C. Nunn [58]; R. Post et al. [63]; S. McElroy et al. [53-55]), the onset of an affective illness in adolescence is associated with a high degree of frequency with the dominance mixed states. According to J. Weckerly [66], mixed states in bipolar disease are observed in adolescents and young men in ⅓ of cases. B. Birmaher and D. Axelson [28] give prevalence rates of mixed states in the range of 38-66%, and according to B. Geller et al. [34, 35], the proportion of patients with mixed affective disorders with affective illness with onset at puberty reaches 55% of cases. nine0003

Geller et al. [34, 35], the proportion of patients with mixed affective disorders with affective illness with onset at puberty reaches 55% of cases. nine0003

For a correct understanding of the current state of the problem of mixed affective disorders of adolescence, it is necessary to briefly review the disputes that took place in general psychopathology in the 19th-20th centuries and led to the creation of various psychopathological concepts of mixed states that differ in diagnostic criteria, and also gave rise to contradictions that remain relevant up to present tense.

According to A. Marneros and F. Goodwin [51], the first scientific information about the clinical manifestations of mixed states was obtained in the 19th century by the German psychiatrist J. Heinroth in 1818 [38], who described ecstatic melancholy (ecstasies melancholica), furiously - frantic (melancholica furens), erotic (melancholia erotica), galloping (melancholia saltans). A little later in France, J. Guislain [37] singled out grumpy depression, grumpy exaltation, and depression with exaltation and foolishness. nine0003

Guislain [37] singled out grumpy depression, grumpy exaltation, and depression with exaltation and foolishness. nine0003

More detailed systematic and evidence-based descriptions of the clinical picture of various variants of mixed states were given by E. Kraepelin, who first introduced the term "mixed states" in the 5th edition of his textbook on psychiatry [46]. Almost simultaneously, his student and colleague W. Weygandt, in his doctoral dissertation (1899) on the problem of mixed states in manic-depressive psychosis [69], confirmed the basic principle that was put by E. Kraepelin as the basis for distinguishing mixed disorders. It consisted in the fact that in these cases, in the structure of the affective phase, there were simultaneously separate components inherent in affective disorders of opposite poles. The Kraepelin-Weygandt typology was gradually refined and finally took shape by 1913 g. It included six varieties of mixed states, formed on the principle of replacing elements of one pole of affective disorders with elements of the opposite. Anxiety-depressive mania (depressive oder angstliche manie), exalted (excited) depression (erregte depression), mania with ideational poverty (unproductive mania, ideenarme manie), manic stupor (manischer stupor), depression with a leap of ideas (ideenfluchtige depression) have been described. and inhibited mania (gehemmte manie) [46, 69].

Anxiety-depressive mania (depressive oder angstliche manie), exalted (excited) depression (erregte depression), mania with ideational poverty (unproductive mania, ideenarme manie), manic stupor (manischer stupor), depression with a leap of ideas (ideenfluchtige depression) have been described. and inhibited mania (gehemmte manie) [46, 69].

After the publications of E. Kraepelin and W. Weygandt, the concept of mixed states was recognized as controversial and doubtful and caused critical opposition from such prominent representatives of the Heidelberg psychiatric school as K. Jaspers [40] and K. Schneider [64]. The main objections of Kraepelin's opponents were threefold. Firstly, K. Jaspers was very skeptical about the possibility of a purely speculative subdivision of an affective syndrome into its constituent elements (the ideational, motor and thymic components of the triad), and, consequently, the possibility of combining and isolating typical ("pure") and atypical (“mixed”) affective states. He carefully wrote in General Psychopathology that it is not yet known in what terms the alleged components of affective disorders should be defined, as well as their combinations, and therefore “and, despite seeming simplicity and clarity, classical affective syndromes and mixed affective disorders inconsistent with typical manifestations” [40]. The second objection belongs to K. Schneider [64], who more definitely took the position of denying the legitimacy of distinguishing mixed states and wrote in Clinical Psychopathology that mixed states are not an independent type of affective disorders and “what in extreme cases may even look as a mixed state, is nothing more than a simple change of affective state, the usual transition from one pole of affective disorders to another. The third objection was also put forward by K. Schneider [64]. He did not share the position of E. Kraepelin regarding the nosological affiliation of mixed affective states to manic-depressive psychosis, unambiguously emphasizing their procedural-schizophrenic nature [64].

He carefully wrote in General Psychopathology that it is not yet known in what terms the alleged components of affective disorders should be defined, as well as their combinations, and therefore “and, despite seeming simplicity and clarity, classical affective syndromes and mixed affective disorders inconsistent with typical manifestations” [40]. The second objection belongs to K. Schneider [64], who more definitely took the position of denying the legitimacy of distinguishing mixed states and wrote in Clinical Psychopathology that mixed states are not an independent type of affective disorders and “what in extreme cases may even look as a mixed state, is nothing more than a simple change of affective state, the usual transition from one pole of affective disorders to another. The third objection was also put forward by K. Schneider [64]. He did not share the position of E. Kraepelin regarding the nosological affiliation of mixed affective states to manic-depressive psychosis, unambiguously emphasizing their procedural-schizophrenic nature [64]. nine0003

nine0003

Authoritative opponents of the Kraepelin-Weygandt concept were representatives of the German psychiatric school Wernicke-Kleist-Leonhard, which continued the tradition of the French psychiatrists J. Falret [32, 33] and J. Baillarger [24]. C. Wernicke [67, 68], K. Kleist [41-44], and then K. Leonhard [49] developed their own, different from the concept of E. Kraepelin, a complex classification of phasic psychoses in a continuum of endogenous diseases with multiple subgroups or separately selected categories: monopolar phasic affective psychoses, manic-depressive psychosis, cycloid psychoses, unsystematized and systematized forms of schizophrenia. It should be emphasized that K. Leonhard referred to manic-depressive psychosis only bipolar varieties of affective illness (according to modern terminology) and insisted on the nosological independence of both individual affective episodes (for example, the so-called "pure melancholia", "pure mania"), and recurrent affective phases of the same polarity. K. Leonhard did not attach significant importance to mixed states in the understanding of E. Kraepelin, noting their extreme rarity. Instead, he introduced the concepts of "partial mania" and "partial melancholia" (teilzustande), which were incompletely developed pictures of manic or depressive affect and could occur in manic-depressive (bipolar) illness [49].

K. Leonhard did not attach significant importance to mixed states in the understanding of E. Kraepelin, noting their extreme rarity. Instead, he introduced the concepts of "partial mania" and "partial melancholia" (teilzustande), which were incompletely developed pictures of manic or depressive affect and could occur in manic-depressive (bipolar) illness [49].

After the sharp criticism of the concept of mixed states as understood by Kraepelin-Weygandt by the leading representatives of the German psychiatric school, research in this direction practically stopped both in Germany and in France for many decades. Among the single works performed during this period, attention is drawn to the study by E. Stransky [65], who, based on the mechanisms of formation of mixed states, identified two variants of mixed disorders - simultaneous and successive. The simultaneous form is characterized by the simultaneous coexistence in the structure of a mixed state of individual components of affective syndromes (depressive and manic). The successive variant, according to E. Stransky, proceeds according to the type of so-called "rapid alternation" - a quick, within several hours, change of the components of the affective triad with layering manifestations of phases of different polarity on top of each other. nine0003

The successive variant, according to E. Stransky, proceeds according to the type of so-called "rapid alternation" - a quick, within several hours, change of the components of the affective triad with layering manifestations of phases of different polarity on top of each other. nine0003

Only at the end of the 60s of the XX century, 68 years after the publication of the monograph by W. Weygandt, the Hamburg research group Burger-Prinz again turned to this problem. The results were reflected in the monograph by S. Mentzos [56], who described mixed states and the so-called "mixed-like pictures of phasic psychoses" (mischbildhafften phasischen psychosen). According to modern concepts, in cases of true mixed states, it was an affective illness, and in cases similar to mixed states, mixed states in schizoaffective psychoses, acute polymorphic psychoses in paroxysmal schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder with psychotic disorders incongruent to affect. In addition, S. Mentzos introduced the concept of stable mixed states, corresponding to the classical variants of mixed states according to Kraepelin-Weygandt, and unstable mixed states with rapid cycles of affective phases with a large polymorphism of psychopathological manifestations [56]. nine0003

nine0003

The heyday of research interest in the concept of mixed states is associated with the rapid success of psychopharmacology in the late 70s - early 80s of the XX century. Despite the revolutionary achievements of psychopharmacology, a psychopathologically special group of affective disorders has been identified that differ in their clinical presentation and resistance to traditional psychopharmacological biological therapy (atypical dysphoric mania, depression with a jump in ideas, affective disorders with a rapidly cyclic course). This served as the basis for the beginning of a revival of interest in the old diagnostic concepts, their revision, along with the resumption of previous contradictions and disputes [47, 48, 50, 52]. nine0003

Among the variety of views that have existed in the last decade, five different approaches to the problem of mixed affective states can be distinguished (with a certain degree of conventionality). According to the first, mixed states are not an independent psychopathological formation, but represent only a special, most profound stage in the development of severe forms of depression or mania. G. Carlson and F. Goodwin [29], distinguishing three stages of mania, write that in the third stage, at the peak of its severity, irritability, anger, hostility, and depressive manifestations appear, directly correlated with the severity of the manic episode [45, 63]. nine0003

G. Carlson and F. Goodwin [29], distinguishing three stages of mania, write that in the third stage, at the peak of its severity, irritability, anger, hostility, and depressive manifestations appear, directly correlated with the severity of the manic episode [45, 63]. nine0003

In accordance with another point of view, which also does not recognize the existence of mixed disorders as an independent syndrome, the latter represent only a transitional stage from one pole of affective disorders to another, and in some of these cases there is a particularly slow, protracted transition. According to the figurative expression of J. Himmelhoch et al. [39], patients with such disorders "stuck as if in a trap" in the process of changing (switch) one affective pole of the disorder to another. This point of view is supported by the position of J. Court [31], who also regards mixed affective states as an intermediate step between the opposite affective poles of the continuum of bipolar disorder. nine0003

nine0003

The currently dominant position is the recognition of the independence of mixed states as an affective syndrome. At the same time, some authors distinguish stable and unstable mixed states or the so-called "pure mixed states", in which the entire clinical picture of the phase is determined by mixed affective symptoms. It is indicated that these states tend to have a protracted, chronic course, in contrast to short-term transitional states between affective poles with a mixed picture of their psychopathological disorders [30]. nine0003

It is necessary to mention the original concept of mixed affective states, developed by psychiatrists at the Austrian University Hospital in Vienna, who put forward the "tripolar model" of affective illness. According to their point of view, dysphoric disorders represent the third independent pole of affective pathology along with depressive and manic disorders [27, 57]. According to the concept of P. Berner et al. [25, 26], stable mixed states include not only the classic manifestations resulting from the mixing of manic and depressive disorders, but also states resulting from the mixing of manic or depressive disorders with dysphoric disorders. Thus, the authors identified four types of stable mixed affective states: depressive anhedonia, combined with an increase in manic-type drives; manic euphoria with a reduction of drives according to the depressive type; dysphoric affect with an increase in drives and dysphoric affect with a reduction in drives. In contrast, in unstable mixed states, according to P. Berner, there is an extremely fast asynchronous change in mood, motor and ideational activity, and vegetative manifestations that occur discordantly, inconsistently with each other (the so-called "dynamic instability"). The unstable mixed states described by P. Berner with an asynchronous change of components of the affective triad are most consistent with the descriptions of the alternating type of mixed states according to E. Stransky [25, 26, 65]. nine0003

Thus, the authors identified four types of stable mixed affective states: depressive anhedonia, combined with an increase in manic-type drives; manic euphoria with a reduction of drives according to the depressive type; dysphoric affect with an increase in drives and dysphoric affect with a reduction in drives. In contrast, in unstable mixed states, according to P. Berner, there is an extremely fast asynchronous change in mood, motor and ideational activity, and vegetative manifestations that occur discordantly, inconsistently with each other (the so-called "dynamic instability"). The unstable mixed states described by P. Berner with an asynchronous change of components of the affective triad are most consistent with the descriptions of the alternating type of mixed states according to E. Stransky [25, 26, 65]. nine0003

Finally, it should be noted that some researchers adhere to the point of view put forward by H. Akiskal in 1981 [19], according to which mixed states are the result of a “modifying effect” on depressive and manic disorders of numerous additional factors of various etiologies (psychopharmacotherapy with antidepressants, abuse of narcotic substances, alcohol) or they arise when the premorbid temperament (depressive, hyperthymic or cyclothymic warehouse) is superimposed on the affective phase of opposite polarity [20-23]. nine0003

nine0003

Given such a wide difference in the opinions of researchers from various psychiatric schools on the psychopathological content and pathogenesis of mixed affective states, it becomes clear that even the terminological boundaries of the concept of "mixed state" are still undefined. As rightly noted by G. Perugi and H. Akiskal [59], to date, in the psychiatric literature, there is a “regrettable tendency” to use the terms “mixed depression”, “dysphoric mania”, “depression during mania”, “mixed mania” as equivalent , "mixed disorder". nine0003

In the last decade, as a result of the efforts of various research teams, diagnostic criteria for mixed conditions have been developed, which can be divided into three groups according to the severity of the use of diagnostic features. According to the proposed "broad diagnostic criteria", a mixed disorder can be stated if at least one depressive disorder occurs during the manic state (or vice versa). The “narrow diagnostic criteria” for defining a state as mixed requires the presence of a combination of criteria for a complete syndromic picture of mania and a major depressive episode of at least 2 weeks or at least 7 days for a manic episode (according to the ICD-10 and DSM-IV criteria). The so-called "moderate diagnostic criteria" suggest the presence during the current manic state of a set of certain depressive symptoms (depressed mood, anhedonia, fluctuating affective background, irritability, feelings of hopelessness, guilt, suicidal intentions or actions). The minimum set of features that make it possible to establish a mixed state, according to various diagnostic approaches, varies depending on the severity of the diagnostic parameters. According to the Cincinnati criteria (University of Cincinnati, USA), at least three depressive symptoms are required [53, 54], according to the Pisa criteria (Department of Psychiatry, University of Pisa, Italy), at least two symptoms are required [59-61]. The so-called "Viennese research criteria" (Vienna-criteria) are less strict and suggest the presence of one to three features [26, 27]. Such a significant difference in diagnostic approaches leads to different detectability of mixed disorders. The rates of prevalence of mixed states vary widely from 5 to 73% of all cases of affective pathology [52].

The so-called "moderate diagnostic criteria" suggest the presence during the current manic state of a set of certain depressive symptoms (depressed mood, anhedonia, fluctuating affective background, irritability, feelings of hopelessness, guilt, suicidal intentions or actions). The minimum set of features that make it possible to establish a mixed state, according to various diagnostic approaches, varies depending on the severity of the diagnostic parameters. According to the Cincinnati criteria (University of Cincinnati, USA), at least three depressive symptoms are required [53, 54], according to the Pisa criteria (Department of Psychiatry, University of Pisa, Italy), at least two symptoms are required [59-61]. The so-called "Viennese research criteria" (Vienna-criteria) are less strict and suggest the presence of one to three features [26, 27]. Such a significant difference in diagnostic approaches leads to different detectability of mixed disorders. The rates of prevalence of mixed states vary widely from 5 to 73% of all cases of affective pathology [52].

In the domestic psychiatric literature, the problem of mixed disorders is also extremely insufficiently developed and elucidated. There are only separate articles devoted to this issue [10, 16, 17]. Some studies emphasize the rarity of such conditions [5] and their unfavorable prognostic value [13, 16, 18]. In recent years, leading domestic psychiatrists, although they recognize the legitimacy of distinguishing mixed states [7], as a rule, describe only certain aspects of their clinical, psychopathological and pharmacotherapeutic characteristics. A.B. Smulevich [15], studying mixed disorders in non-psychotic forms of affective diseases, notes as a typical manifestation of mixed states at a young age an increased tendency to form protracted phases, a high suicidal risk in these patients. S.N. Mosolov [3] emphasizes that mixed states, having a significant proportion in bipolar affective disorder, are characterized by a high suicidal risk, are more difficult to diagnose and are characterized by low efficiency of routine psychopharmacotherapy (including the use of lithium salts), as well as a longer duration of affective phases. nine0003

nine0003

The most thorough and comprehensive clinical and psychopathological study of mixed states in the study of endogenous affective psychoses was carried out by O.O. Sosyukalo [16] and G.P. Panteleeva [11] at the Mental Health Research Center (NTSPZ) of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences. The study was conducted from the standpoint of clinical psychiatry with an analysis of the characteristics of the triad of disorders as the main component of the structure of the affective syndrome, taking into account the psychopathological features and ratios of the individual components of the triad. The authors revealed the heterogeneity of the psychopathological structure and mechanisms of the formation of mixed states and identified three typological options: 1) mixed states that are formed by the type of substitution of individual components of the affective triad of one pole with psychopathological affective disorders related to the components of the affective triad of the opposite affective pole - the so-called "typical mixed states"; 2) manifestations formed by joining the affective triad of one pole of disorders of manifestations that are phenomenologically related to the opposite pole of affect (for example, joining the manic triad of asthenic, hypochondriacal disorders) - the so-called "atypical mixed states"; 3) formed as a result of a complete or partial sequential replacement of the components of the triad of a different-pole affective state. In this case, the transition from one pole to another occurs without "light gaps" with "layering" (mixing) of components of opposite polarity - the so-called "alternating mixed states". nine0003

In this case, the transition from one pole to another occurs without "light gaps" with "layering" (mixing) of components of opposite polarity - the so-called "alternating mixed states". nine0003

It must be emphasized that little attention has been paid to the comparative age aspect of the study of mixed affective disorders. In the works of foreign researchers, although there is a high prevalence of mixed disorders in adolescence and adolescence and emphasizes the high suicidal risk of such patients, the emphasis, as a rule, is placed only on the pharmacotherapy of these conditions, while almost no attention is paid to the clinical and psychopathological features of mixed disorders, in At best, only the legitimacy of using certain psychometric scales for diagnosing these disorders is discussed. In the domestic literature, studies are also scarce; at best, they rather mention mixed states in the dynamics of affective diseases in adolescence and adolescence, rather than a detailed clinical and psychopathological analysis. The age preference for mixed states for the adolescent-adolescent period was noted in the works of V.M. Bashina [1], L.A. Ermolina and V.M. Voloshin [4], A.E. Lichko [8] (the latter leaned toward the schizophrenic nature of these states). N.M. Iovchuk [6] notes the short duration of mixed disorders in childhood and adolescence. I.A. Martsenkovsky [9] among adolescents with bipolar affective disorder found a high proportion - up to 70% of mixed affective disorders and a significant frequency - 27% of affective phases with fast and ultrafast cycles.

The age preference for mixed states for the adolescent-adolescent period was noted in the works of V.M. Bashina [1], L.A. Ermolina and V.M. Voloshin [4], A.E. Lichko [8] (the latter leaned toward the schizophrenic nature of these states). N.M. Iovchuk [6] notes the short duration of mixed disorders in childhood and adolescence. I.A. Martsenkovsky [9] among adolescents with bipolar affective disorder found a high proportion - up to 70% of mixed affective disorders and a significant frequency - 27% of affective phases with fast and ultrafast cycles.

The purpose of this study is to study the structure and dynamics of endogenous juvenile mixed states to clarify diagnostic criteria, develop a psychopathological typology, differentiated therapy, and clinical and social prognosis. The objectives of the study included the study of psychopathological features and phenomenology of juvenile mixed states; clarification of the comparative age parameters of the manifestation of juvenile mixed disorders and some clinical and pathogenetic patterns of the formation of these conditions; development of differentiated approaches to therapy and prevention, depending on the clinical and psychopathological structure of syndromes. nine0003

nine0003

Material and methods

A group of patients was examined - 174 adolescents, of which 118 (68%) were boys and 56 (32%) were girls.

At the time of the manifestation of phase states (depressive, manic or mixed), patients were aged 17 to 25 years (mean - 20.4 years).

All of them were hospitalized in the clinic of the National Center for Health Care of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences in the period from 1992 to 2000 due to an affective illness. In the course of the study, clinical-psychopathological and clinical-catamnestic methods were used, the duration of follow-up was in all cases at least 10 years. The proportion of depressive states was 65%, manic - 16%, mixed states - 19%.

This article presents the results of a study of mixed states in the picture of affective phases that manifested in adolescence. When constructing a classification of mixed states of adolescence, typological variants of mixed disorders were taken into account, which were developed in the Department for the Study of Endogenous Mental Disorders and Affective States of the Scientific Center for Health and Human Development of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences [11, 16]. According to the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria, these patients were classified under the heading "Mood Disorders" (affective disorders): F31 (bipolar affective disorder), F33 (recurrent depressive disorder) and F38 (other mood disorders - affective disorders). nine0003

According to the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria, these patients were classified under the heading "Mood Disorders" (affective disorders): F31 (bipolar affective disorder), F33 (recurrent depressive disorder) and F38 (other mood disorders - affective disorders). nine0003

Statistical analysis of the obtained results was carried out using parametric and non-parametric methods together with the staff of the Laboratory of Evidence-Based Medicine and Biostatistics of the National Center for Health Sciences of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences (headed by A.N. Simonov, Candidate of Technical Sciences).

Results and discussion

Clinical differentiation of mixed states of adolescence was carried out taking into account the dominant pole of affective disorders proper (thymic component of the triad of affective syndromes). Accordingly, the manic and depressive types of mixed states were distinguished, an alternating variant of mixed states. As the study showed, in adolescence, not all variants of mixed states were observed, which are described in patients of mature age O. O. Sosyukalo [16], and, accordingly, there were dysphoria-like mania, associative-accelerated depression, and an alternating type of mixed states with an extremely rapid change in the pole of affective disorders. The ratio between the selected variants of mixed states in adolescence was as follows: associative-accelerated depression occurred in 38% of cases, dysphoria-like mania - in 34%, an alternating variant of mixed disorders - in 28%. Let's dwell on each of them in more detail. nine0003

O. Sosyukalo [16], and, accordingly, there were dysphoria-like mania, associative-accelerated depression, and an alternating type of mixed states with an extremely rapid change in the pole of affective disorders. The ratio between the selected variants of mixed states in adolescence was as follows: associative-accelerated depression occurred in 38% of cases, dysphoria-like mania - in 34%, an alternating variant of mixed disorders - in 28%. Let's dwell on each of them in more detail. nine0003

The depressive type of mixed states proceeded according to the type of associative-accelerated depression (depression with a leap of ideas according to Kraepelin [46]). It was observed most often - in 38% of cases. The thymic component of the disorder in this group of examined patients belonged to the depressive pole of affective states and was of a polymodal and labile nature: along with depression, gloominess, despondency, it was possible to detect irritability with physically felt internal discomfort, tension in the chest, which could sometimes be replaced by apathy. Depressive mood during the affective phase could fluctuate in severity. At the height of the state, as a rule, there were suicidal thoughts. The main feature of this variant of mixed states was distinct signs of a manic state dissociating with depressive affect, among which the acceleration of associative thinking, as a rule, characteristic of the manic pole of affect, dominated. These patients willingly and in detail told about their experiences, constantly returning to complaints of low mood, poor health, loss of previous abilities, failure in school or work. In some cases, especially in the pursuit of the attention of the interlocutor, they were carried away by the analysis of the causes of their condition, their speech became wordy, acquired features reminiscent of speech pressure. At the same time, in conversation, the patients were easily distracted, could quickly switch to other topics of conversation, animatedly discussing, for example, sports, fashion, but at the same time they also quickly returned to their previous depressive complaints, accompanying them with ironic mockery of themselves or caustic remarks in their own words.

Depressive mood during the affective phase could fluctuate in severity. At the height of the state, as a rule, there were suicidal thoughts. The main feature of this variant of mixed states was distinct signs of a manic state dissociating with depressive affect, among which the acceleration of associative thinking, as a rule, characteristic of the manic pole of affect, dominated. These patients willingly and in detail told about their experiences, constantly returning to complaints of low mood, poor health, loss of previous abilities, failure in school or work. In some cases, especially in the pursuit of the attention of the interlocutor, they were carried away by the analysis of the causes of their condition, their speech became wordy, acquired features reminiscent of speech pressure. At the same time, in conversation, the patients were easily distracted, could quickly switch to other topics of conversation, animatedly discussing, for example, sports, fashion, but at the same time they also quickly returned to their previous depressive complaints, accompanying them with ironic mockery of themselves or caustic remarks in their own words. the address. At the same time, they blamed themselves for sexual promiscuity, exaggerated moral vices, expressed ideas of self-accusation, reported their imaginary sins, stubbornly complained about the loss of their former intellectual abilities, pessimistically assessing their future prospects in school, work or family life. In a small proportion of patients, ideational acceleration could be combined with motor restlessness, expressed to varying degrees: from mild restlessness, reminiscent of manifestations of neuroleptic akathisia, to motor excitation with agitation, with restless complaints to parents or relatives about "unbearable conditions in the hospital", persistent requests to pick them up from the hospital, and in some cases even with early discharge from the clinic. Another distinctive feature of this type of mixed states was the special nature of somatovegetative manifestations: some patients had hyperphagia with increased appetite for sweets, hypersomnia with difficulty falling asleep and late morning awakening in a depressed mood, with difficulty getting up and persistent suicidal thoughts, especially pronounced in the morning.

the address. At the same time, they blamed themselves for sexual promiscuity, exaggerated moral vices, expressed ideas of self-accusation, reported their imaginary sins, stubbornly complained about the loss of their former intellectual abilities, pessimistically assessing their future prospects in school, work or family life. In a small proportion of patients, ideational acceleration could be combined with motor restlessness, expressed to varying degrees: from mild restlessness, reminiscent of manifestations of neuroleptic akathisia, to motor excitation with agitation, with restless complaints to parents or relatives about "unbearable conditions in the hospital", persistent requests to pick them up from the hospital, and in some cases even with early discharge from the clinic. Another distinctive feature of this type of mixed states was the special nature of somatovegetative manifestations: some patients had hyperphagia with increased appetite for sweets, hypersomnia with difficulty falling asleep and late morning awakening in a depressed mood, with difficulty getting up and persistent suicidal thoughts, especially pronounced in the morning. days. The majority of adolescent male patients had hypersexuality, more often in the form of masturbation, which, according to them, made it possible to relieve internal tension and physical discomfort. nine0003

days. The majority of adolescent male patients had hypersexuality, more often in the form of masturbation, which, according to them, made it possible to relieve internal tension and physical discomfort. nine0003

The manic variant of mixed states , designated as dysphoria-like mania, was in second place in frequency and was observed in 34% of cases. At first glance, these patients gave the impression of typical manic patients with their noisy sociability, lack of a sense of distance from the interlocutor, speech pressure, and hyperactivity. They easily made various plans that were not destined to take place, without hesitation, without hesitation, they were ready to take part in any actions in the department. nine0003

A feature of this type of mixed disorders in patients of adolescence was that instead of fun, pleasure from life characteristic of manic patients, the state of patients was dominated by agitation without a sense of joy with a dissatisfied critical assessment of the surrounding reality, a hostile attitude towards others, irritable and sarcastic mockery, and sometimes even vicious remarks about patients, hospital staff, doctors, combined with a gloomy pessimistic assessment of the future. These patients constantly intervened in the conversations of other patients, while quarreling with patients, easily becoming hostile, aggressive, entering into conflicts, threatening the staff with escape in case of refusal, insisting on fulfilling the requirements. nine0003

These patients constantly intervened in the conversations of other patients, while quarreling with patients, easily becoming hostile, aggressive, entering into conflicts, threatening the staff with escape in case of refusal, insisting on fulfilling the requirements. nine0003

An important feature of this type of mixed states was that when the condition worsened, the severity of thymic manifestations of manic disorders increased against the background of increasing insomnia, the patients simultaneously manifested a feeling of helplessness, hopelessness with pessimism and suicidal thoughts. It is important to note that in a certain situation, under the influence of external failures, disappointments, these ideas were actualized and could be realized in serious suicidal acts. In these patients, there was a simultaneous coexistence of ideas of reassessment of one's own personality and suicidal depressive ideas. According to J. Goldberg et al. [36], G. Perugi and H. Akiskal [62], suicidal intentions are one of the most important diagnostic markers of the manic variety of mixed affective disorders. nine0003

nine0003

Another important distinguishing feature of this type of mixed states of adolescence was a combination of motor hyperactivity with signs of increased exhaustion, which was expressed in a feeling of physical fatigue, weakness, which occurred repeatedly during the day. At such moments, the patients demanded rest, they could lie down and fall asleep for half an hour or an hour.

The alternating type of mixed disorders was more rare - 28% of cases. It was characterized by a rapid, within a few hours - 1 day, change of the thymic component of one pole of affective disorders to another. In these cases, against the background of an affective state of one pole, approaching a typical manic one, there was a sudden, within 2-3 hours, a complete change in the pole of mood with the appearance of depression, depression, often the mood acquired a shade of tearfulness. At the same time, speech remained accelerated, movements were fast, although motor activity was limited to aimless walking along the corridor. The patients sobbed, moaned, lamented, expressed self-reproach, experienced a feeling of their own low value. Such states lasted for several hours and, as a rule, repeated several times during the day, giving way again to the picture of a typical manic symptom complex. The above-described variability in mood with a change in the pole of the thymic component of the triad usually persisted for several weeks. nine0003

The patients sobbed, moaned, lamented, expressed self-reproach, experienced a feeling of their own low value. Such states lasted for several hours and, as a rule, repeated several times during the day, giving way again to the picture of a typical manic symptom complex. The above-described variability in mood with a change in the pole of the thymic component of the triad usually persisted for several weeks. nine0003

Thus, the following psychopathological and phenomenological features of juvenile mixed states were revealed.

The polymodal nature of the thymic component of the affective triad, atypia of its manifestations, the absence of clear manifestations of the components of the affective triad, which gave a special flavor to mixed states. The presence of phenomenological signs that are common to both mania and depression (irritability, sleep disturbance, suicidal thoughts, etc.), which did not correspond only to this particular affect (atypical mixed states according to O. O. Sosyukalo [16], mixed states according to J. Goldberg [36] and H. Akiskal [19]). Dissociation in the manifestations of the affect itself, characteristic of one particular pole, i.e. in juvenile mixed states, it was not about the complete replacement of the components of one pole by the components of the other, but the addition of individual manifestations of another pole of affect without a complete replacement of the entire thymic component as a whole was noted. For example, in patients with manic affect, separate phenomena of depressive experiences were added - hopelessness and pessimism, suicidal thoughts. In the studied patients, there was a more complex structure of the formation of mixed states: not only was the replacement of the components of the triad of one pole with another (classical, typical mixed states), but also the addition of phenomena phenomenologically alien to this pole (atypical mixed states according to O.O. Sosyukalo [ 16]), which were constant or episodic in the dynamics of this affective state, as if "windows" from another pole of disorders.

O. Sosyukalo [16], mixed states according to J. Goldberg [36] and H. Akiskal [19]). Dissociation in the manifestations of the affect itself, characteristic of one particular pole, i.e. in juvenile mixed states, it was not about the complete replacement of the components of one pole by the components of the other, but the addition of individual manifestations of another pole of affect without a complete replacement of the entire thymic component as a whole was noted. For example, in patients with manic affect, separate phenomena of depressive experiences were added - hopelessness and pessimism, suicidal thoughts. In the studied patients, there was a more complex structure of the formation of mixed states: not only was the replacement of the components of the triad of one pole with another (classical, typical mixed states), but also the addition of phenomena phenomenologically alien to this pole (atypical mixed states according to O.O. Sosyukalo [ 16]), which were constant or episodic in the dynamics of this affective state, as if "windows" from another pole of disorders. nine0003

nine0003

Lability of mixed states in dynamics with a change in the pattern of mixed states.

In order to study the influence of the age factor on the prevalence of mixed states among all syndromes of affective illness, a comparative age analysis of the features of clinical and psychopathological manifestations of an affective illness was carried out based on a comparison of clinical data obtained as a result of a clinical and follow-up study of 174 patients examined by us with endogenous affective diseases of juvenile age (the follow-up duration is over 10 years), with the data obtained by B.S. Belyaev [2] when examining 244 adult patients with an affective illness (affective endogenous psychosis), and data obtained by O.O. Sosyukalo [16], - 38 patients of mature age with an affective illness (manic-depressive psychosis). The diagnosis of mixed states was carried out on the basis of uniform standards set forth in well-known guidelines of recent years [12, 14]. The analysis performed showed the presence of a number of phenomenological and clinical age-related features in the dynamics of juvenile affective disorders. The most significant differences that make it possible to identify the role of the age factor include the following: a high proportion (19%) of mixed states in the picture of juvenile affective illness; in adolescent patients, mixed conditions occur 3 times more often (6%) than in adults. In terms of their structure, mixed affective disorders in juvenile affective illness are characterized by a large proportion of atypical and alternating variants of mixed conditions, while their typical variants were found much less frequently.

The most significant differences that make it possible to identify the role of the age factor include the following: a high proportion (19%) of mixed states in the picture of juvenile affective illness; in adolescent patients, mixed conditions occur 3 times more often (6%) than in adults. In terms of their structure, mixed affective disorders in juvenile affective illness are characterized by a large proportion of atypical and alternating variants of mixed conditions, while their typical variants were found much less frequently.

Thus, the results of the study indicate the preferred formation of alternating and atypical variants of mixed conditions in adolescence. These features of mixed disorders can most likely be explained by the influence of a special biological background characteristic of adolescence, which has a powerful pathoplastic and pathogenetic influence. The lability and polymorphism of psychopathological symptoms in general and affective symptoms in particular, the insufficiently completed formation and immaturity of the emotional and cognitive spheres inherent in this age period determine the atypicality of affective manifestations in general, the expression of which can be a high frequency and a special syndromic picture of mixed states of adolescence compared to affective diseases. mature age. nine0003

mature age. nine0003

Bipolar Disorder | Symptoms, complications, diagnosis and treatment

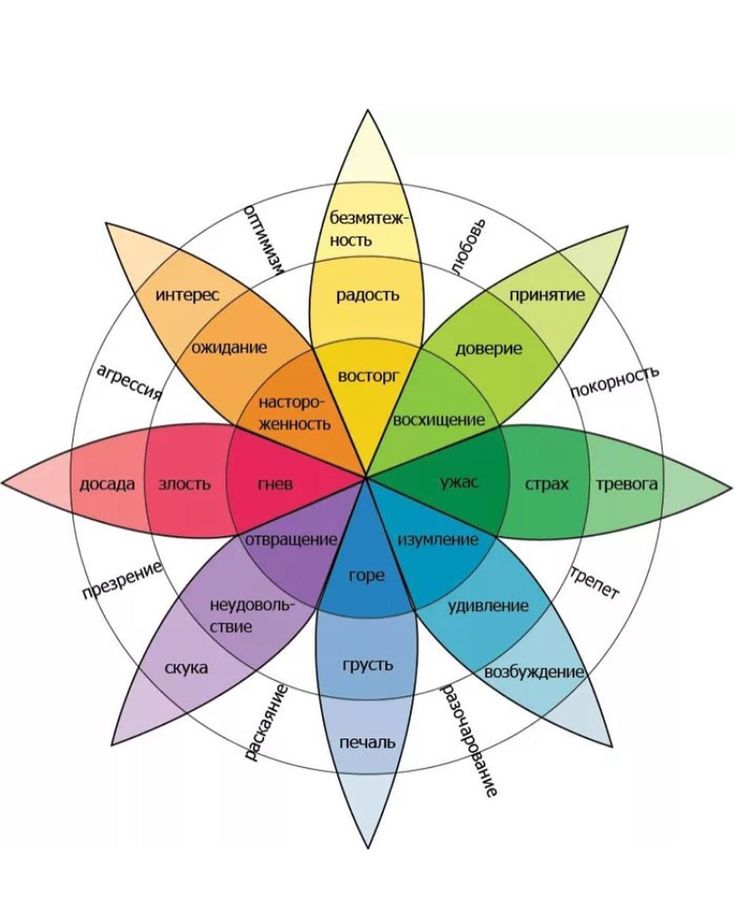

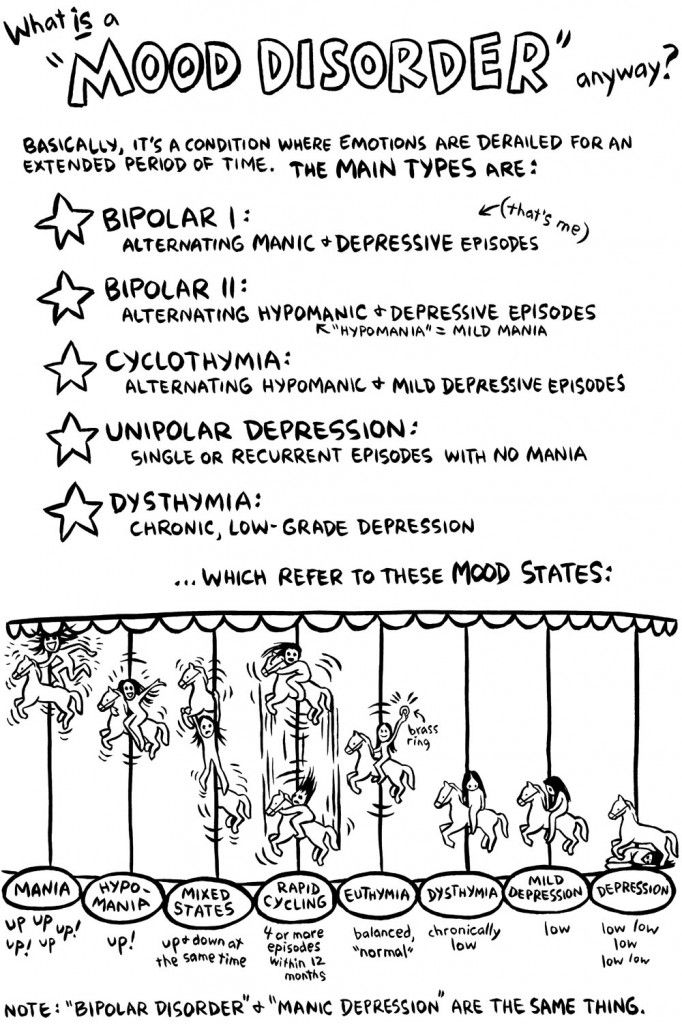

Bipolar disorder, formerly called manic depression, is a mental health condition that causes extreme mood swings that include emotional highs (mania or hypomania) and lows (depression). Episodes of mood swings may occur infrequently or several times a year.

When you become depressed, you may feel sad or hopeless and lose interest or pleasure in most activities. When the mood shifts to mania or hypomania (less extreme than mania), you may feel euphoric, full of energy or unusually irritable. These mood swings can affect sleep, energy, alertness, judgment, behavior, and the ability to think clearly. nine0003

Although bipolar disorder is a lifelong condition, you can manage your mood swings and other symptoms by following a treatment plan. In most cases, bipolar disorder is treated with medication and psychological counseling (psychotherapy).

Symptoms

There are several types of bipolar and related disorders. They may include mania, hypomania, and depression. The symptoms can lead to unpredictable changes in mood and behavior, leading to significant stress and difficulty in life. nine0003

- Bipolar I. You have had at least one manic episode, which may be preceded or accompanied by hypomanic or major depressive episodes. In some cases, mania can cause a break with reality (psychosis).

- Bipolar disorder II. You have had at least one major depressive episode and at least one hypomanic episode, but never had a manic episode. nine0105 Cyclothymic disorder. You have had at least two years - or one year in children and adolescents - many periods of hypomanic symptoms and periods of depressive symptoms (though less severe than major depression).

- Other types. These include, for example, bipolar and related disorders caused by certain drugs or alcohol, or due to health conditions such as Cushing's disease, multiple sclerosis, or stroke.

nine0108

nine0108

Bipolar II is not a milder form of Bipolar I but is a separate diagnosis. Although bipolar I manic episodes can be severe and dangerous, people with bipolar II can be depressed for longer periods of time, which can cause significant impairment.

Although bipolar disorder can occur at any age, it is usually diagnosed in adolescence or early twenties. Symptoms can vary from person to person, and symptoms can change over time. nine0003

Mania and hypomania

Mania and hypomania are two different types of episodes, but they share the same symptoms. Mania is more pronounced than hypomania and causes more noticeable problems at work, school, and social activities, as well as relationship difficulties. Mania can also cause a break with reality (psychosis) and require hospitalization.

Both a manic episode and a hypomanic episode include three or more of these symptoms:

- Abnormally optimistic or nervous

- Increased activity, energy or excitement

- Exaggerated sense of well-being and self-confidence (euphoria)

- Reduced need for sleep

- Unusual talkativeness

- Distractibility

- Poor decision-making - for example, in speculation, in sexual encounters or in irrational investments

Major depressive episode

Major depressive episode includes symptoms that are severe enough to cause noticeable difficulty in daily activities such as work, school, social activities, or relationships. Episode includes five or more of these symptoms:

Episode includes five or more of these symptoms:

- Depressed mood, such as feeling sad, empty, hopeless, or tearful (in children and adolescents, depressed mood may present as irritability)

- Marked loss of interest or feeling of displeasure in all (or nearly all) activities

- Significant weight loss with no diet, weight gain, or decreased or increased appetite (in children, failure to gain weight as expected may be a sign of depression)

- Either insomnia or sleeping too much

- Either restlessness or slow behavior

- Fatigue or loss of energy nine0105 Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt

- Decreased ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness

- Thinking, planning or attempting suicide

Other features of bipolar disorder

Signs and symptoms of bipolar I and bipolar II disorder may include other signs such as anxiety disorder, melancholia, psychosis, or others.