Miracle question solution focused therapy

“Suppose that Tonight, While You're Asleep, a Miracle Happens:” Pragmatic Solution-Focused Therapy for Substance Abuse

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

- PMC3125538

Front Psychol. 2010; 1: 149.

Published online 2010 Oct 11. Prepublished online 2010 Aug 16. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00149

PMCID: PMC3125538

Reviewed by 1,*

A book review on Solution-focused substance abuse treatment by Terri Pichot (with Sara A. Smock). New York: Routledge, 2009. 232 pp. ISBN 978-0-7890-3723-7 (soft cover). $ 34.95d

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

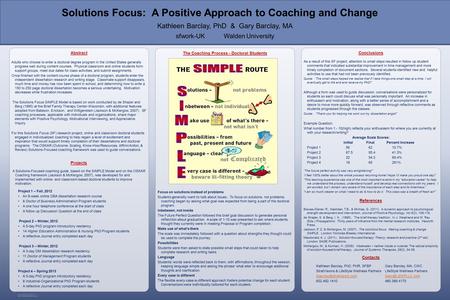

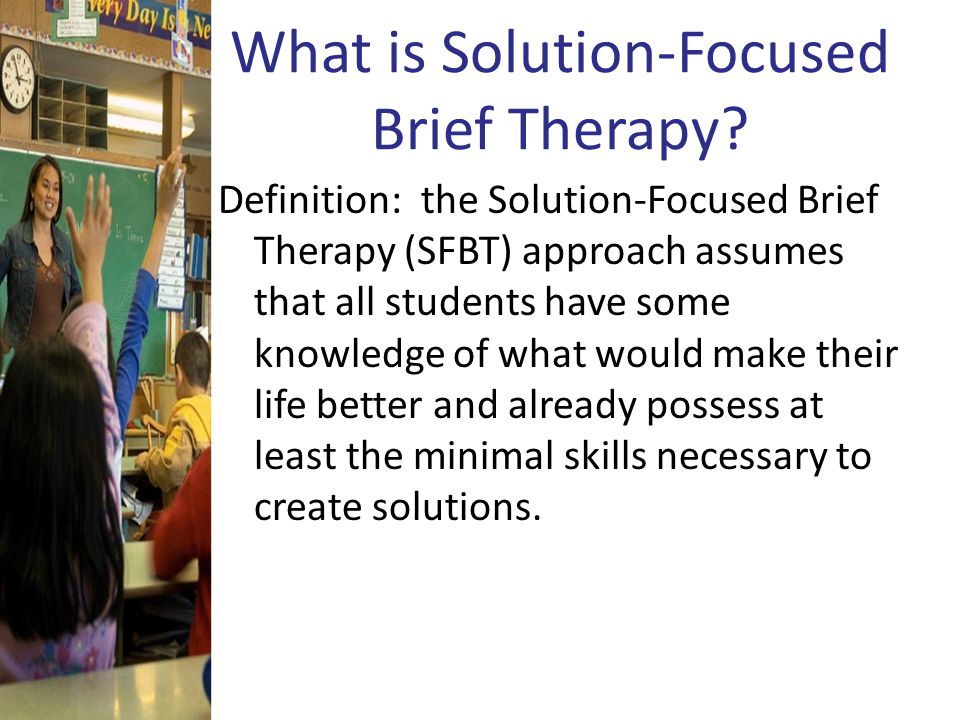

Solution-focused therapy (SFT), developed by Steve De Shazer and Insoo Kim Berg is a social constructivist model of brief therapy emphasizing the role of language in problem resolution (Nichols, 2008).

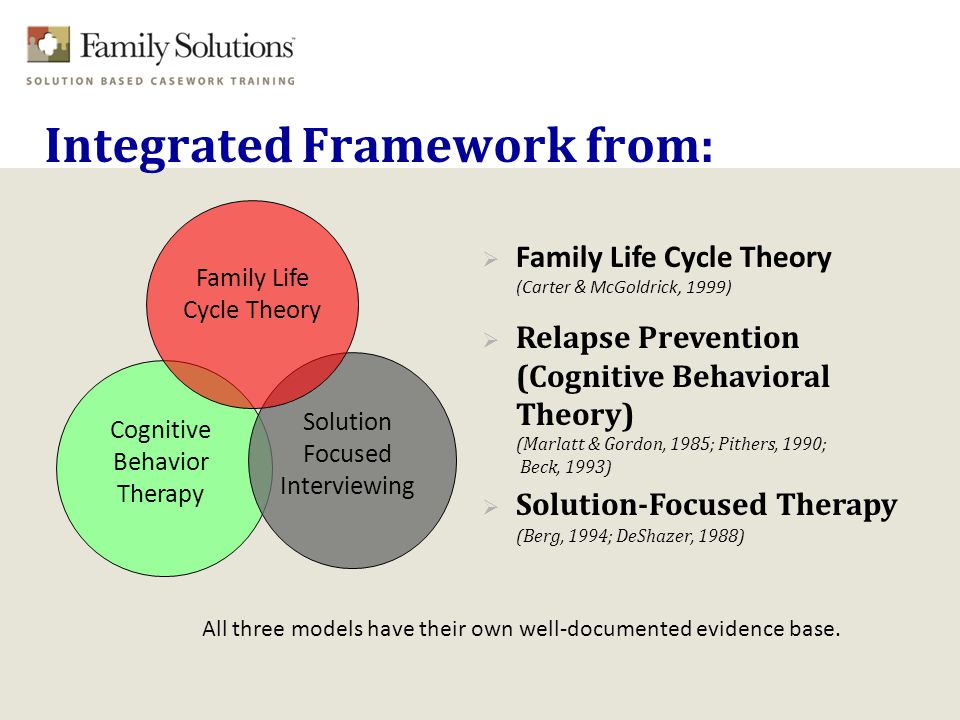

Pichot, having studied and trained with De Shazer and Berg, has thoughtfully applied this approach to treating patients with significant substance abuse problems. Pichot's book, along with other newer approaches to substance abuse treatment such as motivational interviewing (Rollnick et al., 2007) and relapse prevention (Marlatt and Donovan, 2005), reflect a major shift in the field away from the disease model and an often confrontational treatment style, to a more collaborative, client-centered approach which downplays individual pathology.

Solution-focused therapy has its origins in postmodern-family therapy developed in the late 1980s and 1990s (Nichols, 2008). De Shazer, along with other systemic therapists of the time, was strongly influenced by anthropologist Gregory Bateson's writings about epistemology. Bateson's theoretical writing, while often difficult to digest, contains a core concept in solution-focused therapy: “…the difference that makes a difference or an idea that is news of difference” (De Shazer, 1982, p. 5). Bateson's influence on SFT is evident by its central technique, the miracle question:

5). Bateson's influence on SFT is evident by its central technique, the miracle question:

Now, I want to ask you a strange question. Suppose that while you were sleeping tonight and the entire house is quiet, a miracle happens. The miracle is that the problem which brought you here is solved. However, because you're sleeping, you don't know that the miracle has happened. So, when you wake up tomorrow morning, what will be different that will tell you a miracle has happened and the problem which bought you here is solved? (DeJong and Berg, 1998, pp. 77–78, cited in Pichot, 2009, p. 27).

In working with clients, Pichot is always on the alert for exceptions – episodes in which they responded to stress without drug use. She then encourages clients to reflect on how they achieved this self-control and its implications for their view of themselves.

The miracle question, Pichot's central technique, has five key components. First, the change is unpredictable and does not occur naturally. Second, the problem that brought the client to treatment is solved. When working with substance abuse, defining the problem can be challenging since these patients often deny any difficulty. When faced with this response, Pichot, through questioning, usually finds that important others in the client's life, including probation officers and child protective service caseworkers, believe that that the client has a problem. The miracle then becomes successfully convincing these authorities that the client does not have a problem so that a desired outcome, such as regaining custody of children, will occur. This approach is interesting since it takes the therapist out of the role of social control agent as well as eliminates the need to confront the client about their substance use, but still requires the client to address the issue. As a result, a firm alliance between therapist and client is more likely. A third element is that the miracle occurs tonight, indicating a sense of immediacy. By having change occur rapidly, extended treatment is unnecessary.

Second, the problem that brought the client to treatment is solved. When working with substance abuse, defining the problem can be challenging since these patients often deny any difficulty. When faced with this response, Pichot, through questioning, usually finds that important others in the client's life, including probation officers and child protective service caseworkers, believe that that the client has a problem. The miracle then becomes successfully convincing these authorities that the client does not have a problem so that a desired outcome, such as regaining custody of children, will occur. This approach is interesting since it takes the therapist out of the role of social control agent as well as eliminates the need to confront the client about their substance use, but still requires the client to address the issue. As a result, a firm alliance between therapist and client is more likely. A third element is that the miracle occurs tonight, indicating a sense of immediacy. By having change occur rapidly, extended treatment is unnecessary. Fourth, the miracles’ premise is that the client is unaware that change has occurred which leads to the fifth dimension, the client must be attuned to their environment to detect change. Pichot prompts this reflection with specific questions such as “What will be the first things you would notice?” For clients who have difficulty with introspection, an important other's perspective may be elicited, “What would your wife notice?” Pichot emphasizes the power of this question since it permits the client to closely examine what their life would be like without the problem.

Fourth, the miracles’ premise is that the client is unaware that change has occurred which leads to the fifth dimension, the client must be attuned to their environment to detect change. Pichot prompts this reflection with specific questions such as “What will be the first things you would notice?” For clients who have difficulty with introspection, an important other's perspective may be elicited, “What would your wife notice?” Pichot emphasizes the power of this question since it permits the client to closely examine what their life would be like without the problem.

Many of Pichot's examples come from community agency settings with “involuntary” (my word, not Pichot's) clients in court-ordered treatment. To integrate the reality of regular urine drops with postmodernism is no mean feat but Pichot does it well. With an appreciation of the elevated risks for suicide and homicide (both as perpetrators and victims), Pichot does not minimize the clinical challenges posed by her clients. She even includes attention to documentation for risk management.

She even includes attention to documentation for risk management.

I found her description and examples of applying solution-focused philosophy to the problem of “dirty” urines to be particularly useful. The therapist reports the result in a factual, neutral, non-punitive manner. Again, the test result is not presented as the client having failed but, instead as a problematic event that leads, almost immediately, to a solution: “I want you to imagine that it's a couple of months down the road and you haven't had any more positive urine screens…What did you do differently to pull that off ?” (p. 98).

I found Pichot's book to be readable and eminently practical. I do have concerns about, how readily SFT should be employed in many settings. While SFT is incredibly popular, a strong evidence basis lags behind. Available evidence supporting this approach is primarily based on small clinical samples (Conoley et al., 2003; Gingrich and Eisengart, 2004). SFT, similar to many other family therapy models, was developed outside of a university setting. In part, because of this history, empirical findings on therapy process, outcome, and conditions, for which SFT and similar therapies are valid treatments, often lag behind clinical development and popularity.

In part, because of this history, empirical findings on therapy process, outcome, and conditions, for which SFT and similar therapies are valid treatments, often lag behind clinical development and popularity.

The book, itself, is well-written and would be valuable to several audiences. Professionals working in the substance abuse field lacking a firm grounding in SFT will find the book accessible and full of concrete case examples. For those new to the field, Pichot provides useful forms, treatment planning outlines, and an annotated bibliography of both SFT and substance abuse resources, which would be useful regardless of one's orientation. For those wanting to become more familiar with SFT, the book provides a readable overview of the key techniques and clinical principles upon which this approach is founded. Pichot's skill in making SFT accessible would make the book a useful secondary resource for classes in psychotherapy or family therapy.

- Conoley C. W., Graham J.

M., Neu T., Craig M. C., O'Pry A., Cardin S. A., Brossart D. F., Parker R. I. (2003). Solution-focused family therapy with three aggressive and oppositional-acting children: an N = 1 empirical study. Fam. Process 42, 361–374 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2003.00361.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

M., Neu T., Craig M. C., O'Pry A., Cardin S. A., Brossart D. F., Parker R. I. (2003). Solution-focused family therapy with three aggressive and oppositional-acting children: an N = 1 empirical study. Fam. Process 42, 361–374 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2003.00361.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - DeJong P., Berg I. K. (1998). Interviewing for Solutions. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole [Google Scholar]

- De Shazer S. (1982). Patterns of Brief Family Therapy: An Ecosystemic Approach. New York: Guilford [Google Scholar]

- Gingrich W. S., Eisengart S. (2004). Solution-focused brief therapy: a review of the outcome research. Fam. Process 39, 477–498 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2000.39408.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt A. G., Donovan D. M. (2005). Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behavior, 2nd Edn. New York: Guilford [Google Scholar]

- Nichols M. (2008). Family Therapy: Concepts and Methods, 8th Edn. Boston: Allyn & Bacon [Google Scholar]

- Pichot T.

(2009). Solution-Focused Substance Abuse Treatment. New York: Routledge [Google Scholar]

(2009). Solution-Focused Substance Abuse Treatment. New York: Routledge [Google Scholar] - Rollnick S., Miller W. R., Butler C. C. (2007). Motivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change. New York: Guilford [Google Scholar]

Articles from Frontiers in Psychology are provided here courtesy of Frontiers Media SA

Cool Intervention #10: The Miracle Question

The Ten Coolest Therapy Interventions series kicks off with supernatural power. Many clients come to therapy looking for a miracle. Here's a technique built on miracles. I'm honored to speak with Dr. Linda Metcalf, expert on the Miracle Question and Solution Focused Therapy.

The therapeutic intervention is a critical element in most forms of psychotherapy. In this series I survey ten diverse techniques that are, in my opinion, cool. For more information on the series take a look at the introduction.

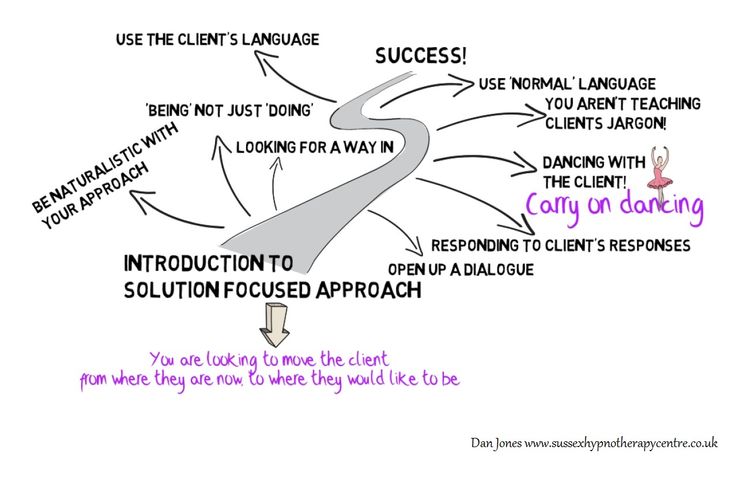

Solution Focused Therapy (aka Brief Therapy) emerged in the 1980's as a branch of the systems therapies. A married therapist couple from Milwaukee, Steve de Shazer and Insoo Kim Berg, are credited with the name and basic practice of SFT. The theory focuses not on the past, but on what the client wants to achieve today. By making conscious all the ways the client is creating their ideal future and encouraging forward progress, clinicians point clients toward their goals rather than the problems that drove them to therapy.

A married therapist couple from Milwaukee, Steve de Shazer and Insoo Kim Berg, are credited with the name and basic practice of SFT. The theory focuses not on the past, but on what the client wants to achieve today. By making conscious all the ways the client is creating their ideal future and encouraging forward progress, clinicians point clients toward their goals rather than the problems that drove them to therapy.

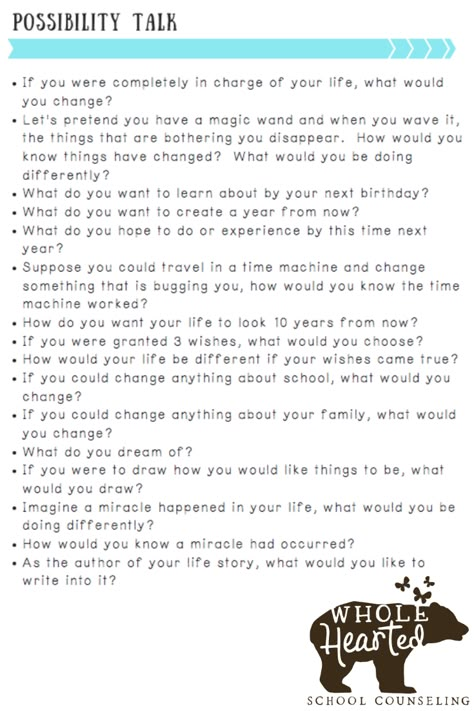

The Miracle Question fits perfectly with this model. Imagining an ideal future and connecting it to the present immediately actualizes the work. Clients are challenged to look past their obstacles and hopelessness and focus on the possibilities.

It's cool because it's a relatively simple intervention that can have a powerful impact. Just take a look at the question (response #2). You're probably crafting your response already. It's creative, bold, healing, a bit mysterious and definitely has a cool name. The Top Ten designation is well deserved.

Don't just listen to me, hear it from an expert. Linda Metcalf, Ph.D. is founder of the Solution Focused Institute of Fort Worth, Texas and author of ten books including The Miracle Question: Answer It and Change Your Life. Beyond writing and therapy, she speaks internationally to schools, agencies and universities. She was kind enough to share her wisdom with us today.

Linda Metcalf, Ph.D. is founder of the Solution Focused Institute of Fort Worth, Texas and author of ten books including The Miracle Question: Answer It and Change Your Life. Beyond writing and therapy, she speaks internationally to schools, agencies and universities. She was kind enough to share her wisdom with us today.

1. When would a clinician use the Miracle Question?

The Miracle Question is a goal setting question that is useful when a client simply does not know what a preferred future would look like. It can be used with individuals to set the course for therapy, with couples, to clarify what each person needs from each other and with families, who too often see one person as the culprit. By using the Miracle Question and asking each person what a better life would look like, it is apparent, perhaps for the first time, what others need from each other.

2. What does it look like?

"Suppose tonight, while you slept, a miracle occurred. When you awake tomorrow, what would be some of the things you would notice that would tell you life had suddenly gotten better?"

When you awake tomorrow, what would be some of the things you would notice that would tell you life had suddenly gotten better?"

The therapist stays with the question even if the client describes an "impossible" solution, such as a deceased person being alive, and acknowledges that wish and then asks "how would that make a difference in your life?" Then as the client describes that he/she might feel as if they have their companion back again, the therapist asks "how would that make a difference?" With that, the client may say, "I would have someone to confide in and support me." From there, the therapist would ask the client to think of others in the client's life who could begin to be a confidant in a very small manner.

3. How does it help the client?

It catapults the client from a problem saturated context into a visionary context where he/she has a moment of freedom, to step out of the problem story and into a story where they are more problem free. But, more importantly, it helps the therapist to know exactly what the client wants from therapy...and this is what makes Solution Focused Therapy so efficient and brief.

But, more importantly, it helps the therapist to know exactly what the client wants from therapy...and this is what makes Solution Focused Therapy so efficient and brief.

4. In your opinion, what makes the Miracle Question a cool intervention?

It helps the therapist see where the client wants to go. Too often, therapists assume that a client needs to grieve, leave their spouse, quit their job, after the client describes why he/she has come to therapy. The Miracle Question helps the client and therapist to address exactly what the client wants, not what the therapist thinks is best.

Solution-Oriented Approach: Solution-Oriented Psychiatry

Translated by Xenia Chistopolskaya, edited by Olga Zotova.

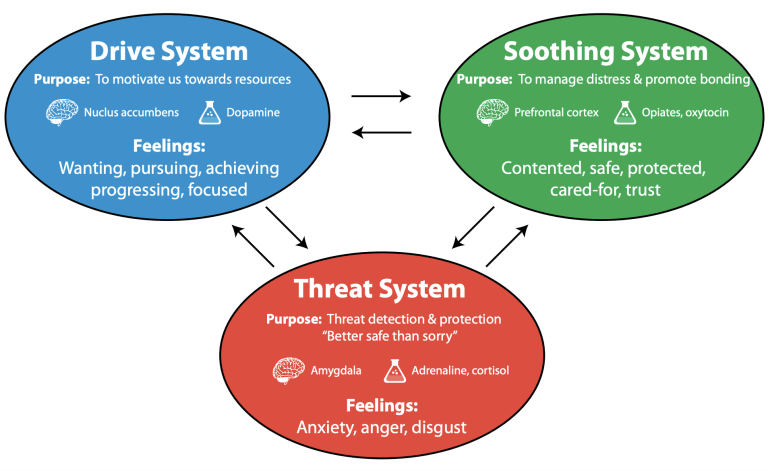

Solution Focused Brief Therapy (SORT) can be widely introduced into psychiatric practice as a short form of psychotherapy that enhances the client's autonomy and focuses on what the client wants rather than the problem.![]() It was created in a process of continuously eliminating from existing forms of therapy those elements that have not been proven to lead to positive results for clients. Research indicates that SBCT is an effective and cost-effective way of working, and when applied in practice, it contributes to greater job satisfaction for the psychiatrist. It can be used as a method of intervention, for example, in times of crisis, as the main method of psychotherapy or as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy.

It was created in a process of continuously eliminating from existing forms of therapy those elements that have not been proven to lead to positive results for clients. Research indicates that SBCT is an effective and cost-effective way of working, and when applied in practice, it contributes to greater job satisfaction for the psychiatrist. It can be used as a method of intervention, for example, in times of crisis, as the main method of psychotherapy or as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy.

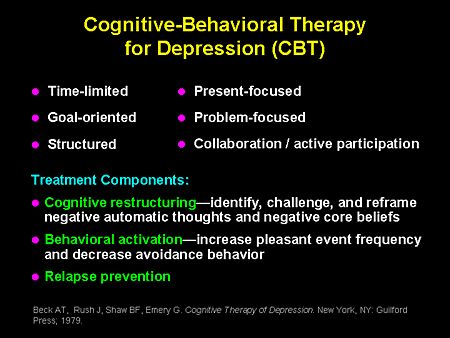

Short-term treatments are now in vogue. As the focus shifts to new forms of medical intervention, such as managed care and stepwise care, clients become more free to demand effective and respectful therapeutic interventions. Short-term therapies include protocol-based, problem-oriented cognitive-behavioral therapy, where diagnosis and treatment are aimed at reducing or eliminating the problem or complaint.

Solution Focused Brief Therapy (SBRT), in which performance and job satisfaction are important motivators, has been gaining popularity since the 1980s. In SRCT, the focus is on identifying and achieving the client's preferred future: what does the client want instead of their problem or complaint? In many parts of the world, mental health services now operate under the provisions of the CSRT. This article proposes ORC as an effective adjunct to current psychiatric practice and explains its application from a psychiatric perspective.

In SRCT, the focus is on identifying and achieving the client's preferred future: what does the client want instead of their problem or complaint? In many parts of the world, mental health services now operate under the provisions of the CSRT. This article proposes ORC as an effective adjunct to current psychiatric practice and explains its application from a psychiatric perspective.

What is ORCT?

Historical Introduction

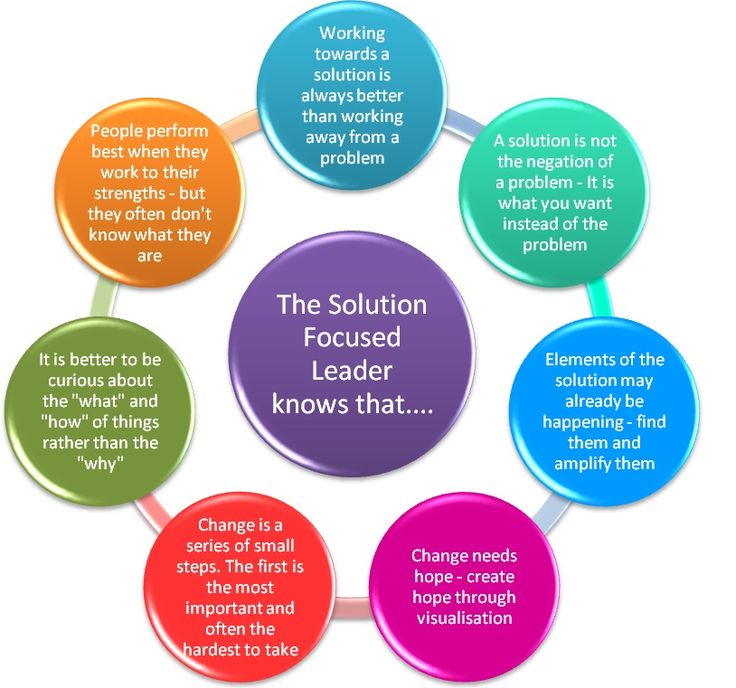

Developed in the 1980s by de Schaiser, Berg, and colleagues at the Center for Brief Family Therapy in the United States, SPRT builds on the ideas of Watzlawick, Wickland, and Fish, who found that attempting a solution often reinforces a problem and understanding The origins of the problem are not always necessary. De Shaser emphasized the importance of strengthening solutions rather than problem solving, and gave the client the role of an expert. The client is invited to reflect on what he would like to replace the problem with and at what stage he would accept the therapy as successful.

Goal Statement

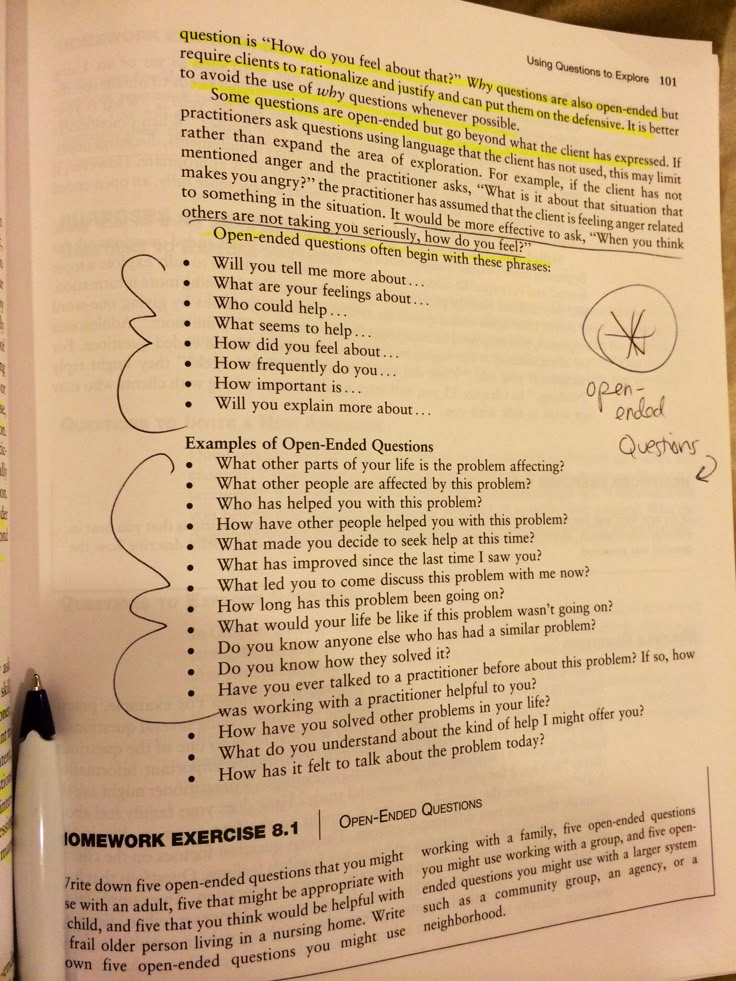

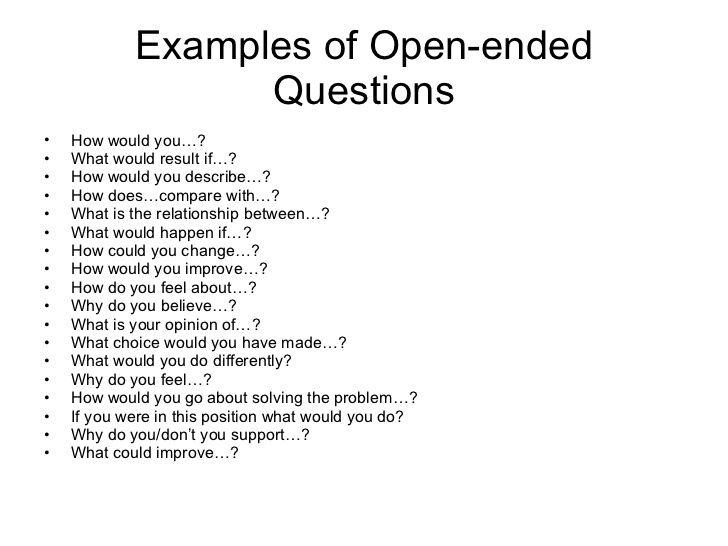

During the initial interview, the client is asked to state the goal in positive, concrete, and achievable behavioral terms: “What should be the outcome of therapy? What do you want instead of your problem? He may also be asked, “What are your best hopes? What will the achievement of the goal bring?

Sometimes the “wonderful question” is asked: “Imagine that a miracle happened at night that (sufficiently) solved your problems that brought you here, but you don’t know this, since it happened while you were sleeping. What will be the first sign tomorrow morning by which you will determine that this miracle has happened? Next, the client is asked to describe in as much detail and specificity as possible how his day will go after the miracle happened.

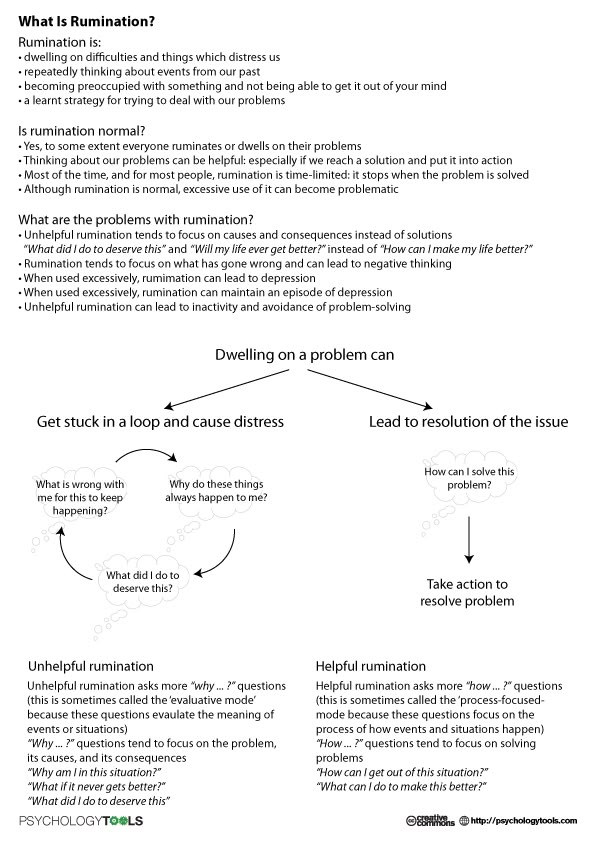

Exceptions

Solution-oriented brief therapy begins with the assumption that exceptions can always be found to a problem: no problem or complaint is ever present with the same force. These positive exceptions, where the problem or complaint is felt less severe or not felt for a while, are often overlooked by the client or discounted as something insignificant due to blindness to the problem. The solution-focused therapist emphasizes these exceptions and asks, “At what points is the problem or complaint less or less pronounced, and how are these points different? What are you doing differently at this time?” The client can also be asked questions when the described miracle or preferred situation is already happening to some extent: what then does he do differently?

These positive exceptions, where the problem or complaint is felt less severe or not felt for a while, are often overlooked by the client or discounted as something insignificant due to blindness to the problem. The solution-focused therapist emphasizes these exceptions and asks, “At what points is the problem or complaint less or less pronounced, and how are these points different? What are you doing differently at this time?” The client can also be asked questions when the described miracle or preferred situation is already happening to some extent: what then does he do differently?

Scale and competency questions

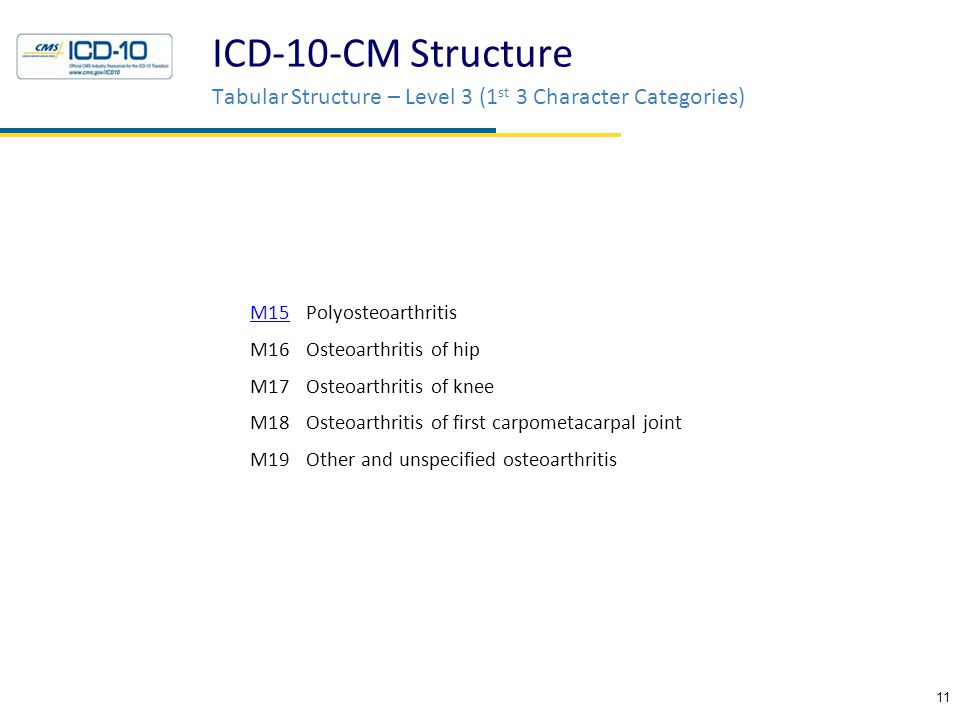

The client is asked to indicate the extent to which their goal has already been achieved on a scale from 0 to 10, where 10 is the most desirable outcome and 0 is the worst state of affairs that has ever been . “What did you do / or have already done to achieve this score? What would one point up on the scale look like? What will you do differently? What point on the scale do you want to get to so that the goal is (sufficiently) achieved? At what number would you feel ready to end therapy?”

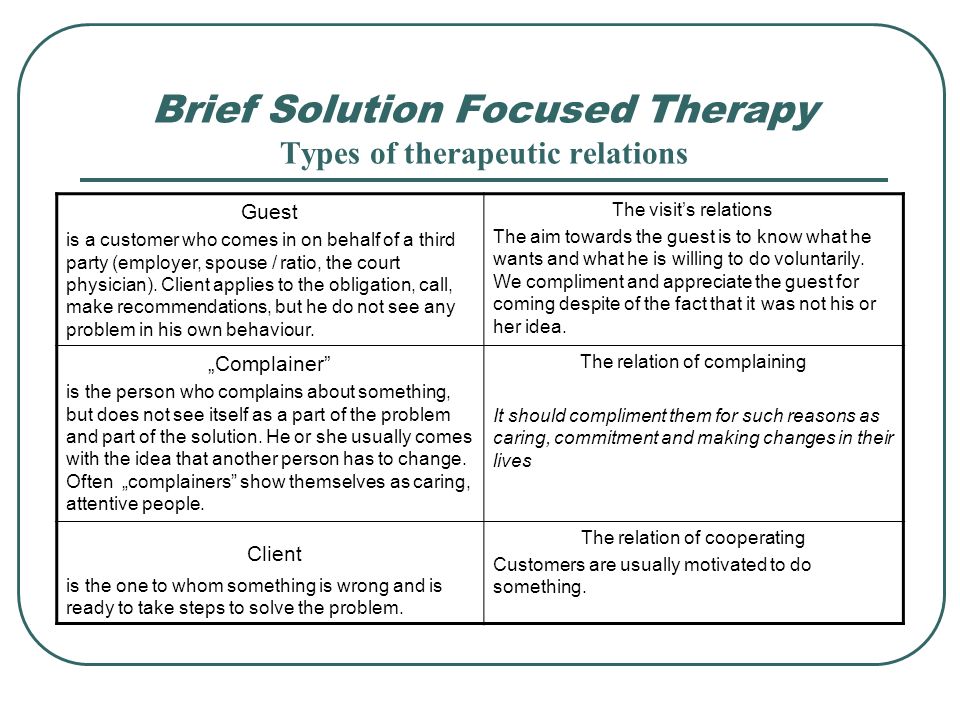

Relations of the therapist and client: “ Visitor ” , “ complainant ” and “Customer ”

VCC FOOCETICATIONS IN in terms of changing his behavior. There are three types of relationship between the client and the therapist: "visitor", "complainer" and "customer". The "visitor" is guided by others and believes that he is not experiencing a problem, except perhaps some pressure from the referrer. The complainer suffers emotionally but does not see himself as part of the problem and/or solution: the other person or the world needs to change, not the client. The "customer" sees himself as part of the problem and / or solution and is motivated to change his behavior. Given the client's motivation, the solution-oriented therapist is able to apply interventions that encourage "visitors" and "complainers" to become "customers."

There are three types of relationship between the client and the therapist: "visitor", "complainer" and "customer". The "visitor" is guided by others and believes that he is not experiencing a problem, except perhaps some pressure from the referrer. The complainer suffers emotionally but does not see himself as part of the problem and/or solution: the other person or the world needs to change, not the client. The "customer" sees himself as part of the problem and / or solution and is motivated to change his behavior. Given the client's motivation, the solution-oriented therapist is able to apply interventions that encourage "visitors" and "complainers" to become "customers."

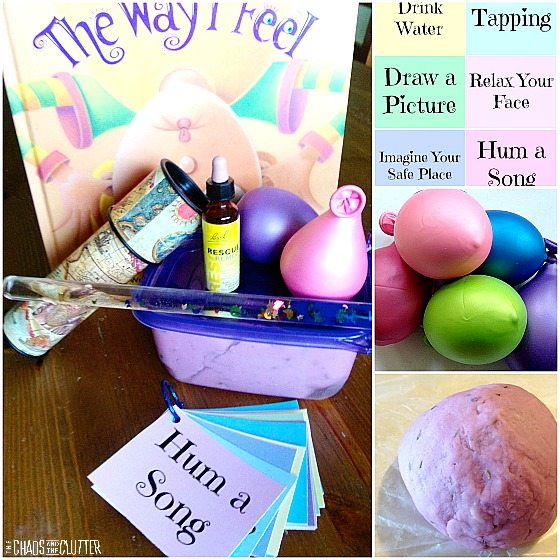

Feedback

At the end of each session, the solution-oriented therapist provides feedback to the client that includes compliments and, depending on the therapeutic relationship, suggestions for homework. The "customer" is asked to perform a behavioral task, such as doing more of what will bring the desired goal closer, or pretending that the miracle has already happened. The “complainer” can be asked to perform an observational task, such as paying attention to what is going well and does not need to be changed. The “visitor” receives information, but not offers, since he is not yet (yet) motivated to take independent actions.

The “complainer” can be asked to perform an observational task, such as paying attention to what is going well and does not need to be changed. The “visitor” receives information, but not offers, since he is not yet (yet) motivated to take independent actions.

Therapist's position

The solution-oriented therapist's position is one of ignorance: he allows himself to be an informed client whose context in his own life will help determine how solutions will be developed. Another aspect of the therapist's position is the "lead while being one step behind" position. The therapist, in a metaphorical sense, stands behind the client and asks him questions focused on the solution, inviting him to look at his preferred future and imagine a wide horizon of personal possibilities to achieve the goal.

Follow-up conversations

In follow-up conversations, client and therapist carefully explore what has improved. “What has gotten better since our last meeting?” - an invaluable beginning of any contact, even if the client has been visiting the therapist for many years. The therapist asks for detailed descriptions of positive exceptions, compliments, and emphasizes the client's personal contribution to the solutions found. At the end of each conversation, the client is asked if he thinks he needs another meeting and, if so, when he would prefer to return. In fact, in many cases the client feels that he does not need to return, or makes an appointment further than is usually the case in therapy.

The therapist asks for detailed descriptions of positive exceptions, compliments, and emphasizes the client's personal contribution to the solutions found. At the end of each conversation, the client is asked if he thinks he needs another meeting and, if so, when he would prefer to return. In fact, in many cases the client feels that he does not need to return, or makes an appointment further than is usually the case in therapy.

Evidence

Stams et al. The results demonstrate the positive effect of ORCT on the same level as other forms of psychotherapy. Interventions in recent studies appear to be the most effective - according to the authors, this follows from a better mastery of the technique. They conclude that ORCT is as effective as traditional forms of therapy. However, SRCT achieves a positive effect in a shorter time frame and encourages client autonomy. Similar results were obtained from a meta-analysis of 22 studies by Kim 5 . In the McDonald 6 review of studies (available at www. solutionsdoc.co.uk), 80 studies spanned 2 weeks to 6 years, including 2 meta-analyses, 9 randomized controlled trials and 27 comparative studies. Comparative studies have included short and long term psychodynamic psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and substance abuse programs. The results show that unlike other psychological therapies, SBCT is effective in more than 60% of cases and, unlike other therapies, SBCT has been shown to be equally effective for all social classes. The therapy has been used in intellectual disability services, education and the justice system, including cases of domestic violence.

solutionsdoc.co.uk), 80 studies spanned 2 weeks to 6 years, including 2 meta-analyses, 9 randomized controlled trials and 27 comparative studies. Comparative studies have included short and long term psychodynamic psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and substance abuse programs. The results show that unlike other psychological therapies, SBCT is effective in more than 60% of cases and, unlike other therapies, SBCT has been shown to be equally effective for all social classes. The therapy has been used in intellectual disability services, education and the justice system, including cases of domestic violence.

Psychiatrist and ORCT

Indications and contraindications

Depending on the nature of the complaint, a problem-focused approach (e.g., pharmacotherapy) may be chosen, in which it is often valuable to additionally use ORCT. It is a mistake to think that SPRT can be applied to "easier" problems - O'Hanlon and Rowan 7 describe how SBCT has been used in cases of chronic and severe mental disorders such as psychotic disorders.

Since ORCT does not require a formal structure, it can be useful even in a busy outpatient practice (all three authors work in such settings). The therapist's attitude, attention to the client's goal formulation, and immersion in the often surprisingly wide arsenal of competencies that the client and his environment possess seem to be key components of effectiveness. Both the client and the treatment team may add to the goals as they work, and some discrepancies in goals can be acknowledged and discussed. The therapy is also suitable for the treatment of addiction problems, in part because of the attention paid to motivating the client to change their behaviour.

Can SBCT be applied to disorders of the 2nd axis (Axis II in DSM-5)? The answer is yes, or rather, the question is incorrectly posed, as it implies that the goal is to make the mental disorder disappear. However, the OCCT asks the client what his goal is, which in practice turns out to be a different, more achievable goal than the one in the therapist's head.

Contraindications for SSRT include: a situation where it is impossible to establish a dialogue with the client, a well-executed solution-oriented therapy that has produced unsatisfactory results, or a situation in which the therapist is not ready or able to put aside his expert position.

Diagnosis

Solution-oriented brief therapy is a form of treatment that does not require a thorough diagnosis. One can choose to start treatment immediately and, if required, to attend to the diagnosis at a later stage. Severe psychiatric disorders, or suspicion of such, justify the decision to make a thorough diagnosis, since tracking down "comorbid" organic pathology, for example, has direct therapeutic implications.

Outpatients in primary or secondary health care are eligible for a solution-oriented approach. During the first or subsequent interview, it will automatically become clear whether a detailed diagnosis is required, for example, if there is a noticeable deterioration in the client's condition, or if the treatment does not give positive results. Likewise, stepwise diagnosis should be considered in stepwise treatment.

Likewise, stepwise diagnosis should be considered in stepwise treatment.

Practice Guides and Protocols

Diagnosis-oriented practice guidelines do not yet mention SBCT. However, if there is no "customer" type relationship, work on guidelines and protocols will be difficult, since the client is not (yet) motivated to take appropriate orders. Solution-oriented brief therapy can help transition the therapeutic alliance from a complainer relationship to a customer relationship, after which protocol-based, problem-focused interventions can be used or solution-oriented therapy can continue. SBCT can be seen as a form of behavioral therapy that starts with preferred behaviors and functional cognitions rather than problematic behaviors and dysfunctional cognitions 9 .

Since 2006 the Dutch Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy has included a section on decision-oriented cognitive behavioral therapy.

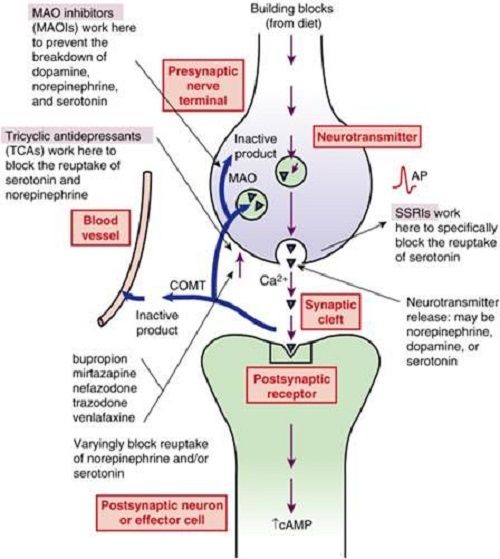

Medical aspects

Biological forms of treatment used by psychiatrists appear to be strictly problem-oriented. However, there is a difference in whether the client wants "depression to disappear" or for him to become "energetic, active or relaxed." A decision-oriented approach in pharmacological treatment may be to encourage the client to give a detailed description of what the first signs of cure will look like, assuming that the treatment will work, and how recovery will manifest itself in the future. Clients are asked what they can add to the effect of the drugs, or what they can do to create a favorable environment in which the drug can have the maximum effect in helping to overcome them.

Crisis interventions

Solution-oriented brief therapy is often very helpful in a crisis situation. The time available usually does not allow for a thorough diagnosis and, moreover, it is very helpful for a client in a crisis to gain confidence in personal competencies and direct their attention to the future. Think about questions such as: “How do you keep going? What has helped you in recent weeks, even if only slightly?” Usually the client delegates his competence to the therapist ("you tell me what to do") - this is a trap that can be avoided with SPRT 10 .

Think about questions such as: “How do you keep going? What has helped you in recent weeks, even if only slightly?” Usually the client delegates his competence to the therapist ("you tell me what to do") - this is a trap that can be avoided with SPRT 10 .

Job satisfaction

With an inquisitive ignorant approach, the therapist encourages the client to take action. To the extent possible, the conversations focus on the client's imagined future, the stage where the client is already in it, or what steps they can take to facilitate future progress. In ORCT, the client does most of the work, which benefits both therapist and client. The frustrations of the therapist (“the client is resisting”) and the client (“therapist doesn’t understand me”) are avoided when the therapist addresses the client’s existing motivation and avoids referring to the “visitor” or “complainer” as a “customer” during conversations or giving im behavioral homework assignments 11 12 . Basic training in SICT for a healthcare professional usually requires 20-40 hours and several months of supervision after that.

Basic training in SICT for a healthcare professional usually requires 20-40 hours and several months of supervision after that.

Clients and therapists generally find ORCT to be a pleasant form of therapy. Inviting them to describe their preferred future situation and the client's experience in their area of expertise makes conversations easier and more positive than problem-focused conversations. In this sense, SSRT also reduces the possibility of "burnout" for those who use this approach, including psychiatrists.

Conclusion

Solution-oriented brief therapy goes beyond the need for a thorough diagnosis, satisfies performance requirements, maintains the client's competence and autonomy, and makes the therapist's work more satisfying. This form of treatment is becoming more widely used in psychiatric practice, complementing the "classic" problem-focused approach of ORCT.

References

1. Bakker J.M., Bannink F.P. Oplossingsgerichte therapie in de psychiatrische praktijk. [Solution focused therapy in psychiatric practice.] Tijdschr Psychiatr 2008; 50:55-9.

[Solution focused therapy in psychiatric practice.] Tijdschr Psychiatr 2008; 50:55-9.

2. Watzlawick P, Weakland JH, Fisch R. Change. Principles of Problem Formation and Problem Resolution. WW Norton, 1974.

3. De Shazer S. Keys to Solution in Brief Therapy. WW Norton, 1985.

4. Stams GJJ, Dekovic M, Buist K, de Vries L. Effectiviteit van oplossingsgerichte korte therapie. Een meta-analysis. [Efficacy of solution-focused brief therapy. A meta-analysis.] Gedragstherapie (Dutch Journal of Behavior Therapy) 2006; 39: 81-94.

5. Kim JS. Examining the effectiveness of solution-focused brief therapy: a meta-analysis. Res Social Work Pract 2008; 18:107-16.

6. Macdonald AJ. Solution-Focused Therapy: Theory, Research and Practice. Sage, 2007.

7. O'Hanlon B, Rowan T. Solution-Oriented Therapy for Chronic and Severe Mental Illness. WW Norton, 2003.

8. Berg IK, Miller SD. Working with the Problem Drinker. A Solution-Focused Approach. WW Norton, 2007.

9. Bannink FP. Oplossingsgerichte vragen. Handboek oplossingsgerichte gespreksvoering. [Solution Focused Questions. Handbook Solution Focused Interviewing.] Pearson, 2006.

10. Bannink FP. posttraumatic success. Solution Focused Brief Therapy. Brief Treat Crisis Interv 2008; 7:1-11.

11. Bannink FP. Gelukkig zijn en geluk hebben. Zelf oplossingsgericht werken. [Being Happy and Being Lucky. Solution Focused Self-Help.] Pearson, 2007.

12. Bannink FP. Solution-focused brief therapy. J Contemp Psychother 2007; 37:87-94.

5 H 63

5 H 63  The authors of the book have tried to make a special emphasis on the practical side of each approach, its methods and techniques. The reader will meet on the pages of the book with the founders of family psychology - Bateson, Ackerman, Minukhin, Whitaker and others, as well as with new names, with those who create family therapy today. 9Published by Arrangement with the original publisher, Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as ALLYN & BACON, a Company

The authors of the book have tried to make a special emphasis on the practical side of each approach, its methods and techniques. The reader will meet on the pages of the book with the founders of family psychology - Bateson, Ackerman, Minukhin, Whitaker and others, as well as with new names, with those who create family therapy today. 9Published by Arrangement with the original publisher, Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as ALLYN & BACON, a Company  About four decades later, theory and practice appear to be questionable and uncertain, which is characteristic of maturity. But first, historians say, was Gregory Bateson on the West Coast—a tall, clean-shaven, angular intellectual, an idea generator who saw the family as a system. On the east coast was Nathan Ackerman, a short man with a bushy beard who was the epitome of a charismatic healer, for whom the family was a collection of individuals struggling to maintain a balance of feelings, irrationality, and desire. Bateson, a man of ideas, and Ackerman, a man of passions, perfectly complemented each other. This is Don Quixote and Sancho Panza family systemic revolution.

About four decades later, theory and practice appear to be questionable and uncertain, which is characteristic of maturity. But first, historians say, was Gregory Bateson on the West Coast—a tall, clean-shaven, angular intellectual, an idea generator who saw the family as a system. On the east coast was Nathan Ackerman, a short man with a bushy beard who was the epitome of a charismatic healer, for whom the family was a collection of individuals struggling to maintain a balance of feelings, irrationality, and desire. Bateson, a man of ideas, and Ackerman, a man of passions, perfectly complemented each other. This is Don Quixote and Sancho Panza family systemic revolution.

The very technique that once defined the field was questioned. Inevitably, it will again hide the specifics and rediscover for study its old taboos: personality, intrapsychic life, emotions, biology, past, and the special place of the family in culture and society.

The very technique that once defined the field was questioned. Inevitably, it will again hide the specifics and rediscover for study its old taboos: personality, intrapsychic life, emotions, biology, past, and the special place of the family in culture and society.  Therapy has always been a union of efforts, but the responsibility for leadership rests with the therapist.

Therapy has always been a union of efforts, but the responsibility for leadership rests with the therapist.

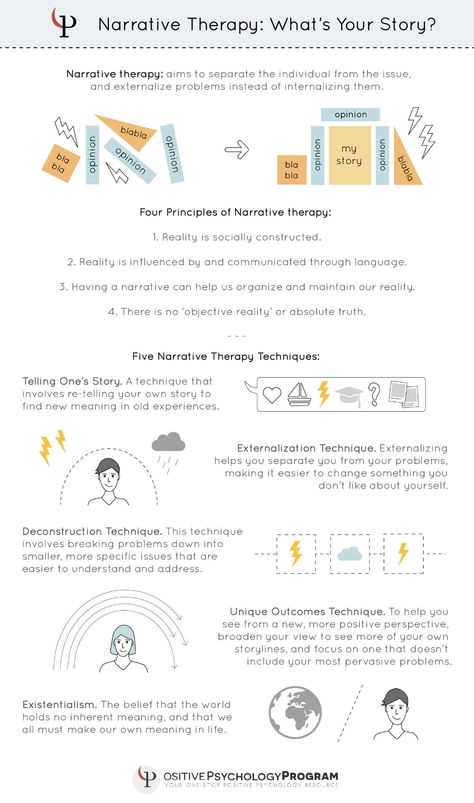

The only way to avoid a sledgehammer-like impact, as many today believe, is to intervene only as a co-constructor of narratives—as if people are not only affected, but are nothing but narratives about themselves.

The only way to avoid a sledgehammer-like impact, as many today believe, is to intervene only as a co-constructor of narratives—as if people are not only affected, but are nothing but narratives about themselves.  A real respect for clients and their integrity may allow the therapist to behave differently from being terribly cautious, may encourage him to be direct and authentic - polite and sympathetic, but at times also frank and probing. Such a therapist recognizes that family members have their own experience and integrity, and that they project their own desires and fantasies into the realm of therapy, which then becomes a field of forces where participants pull each other in different directions.

A real respect for clients and their integrity may allow the therapist to behave differently from being terribly cautious, may encourage him to be direct and authentic - polite and sympathetic, but at times also frank and probing. Such a therapist recognizes that family members have their own experience and integrity, and that they project their own desires and fantasies into the realm of therapy, which then becomes a field of forces where participants pull each other in different directions.  But, of course, these two prototypes are extremely simplified. Most practitioners fall somewhere between these two poles of neutrality and persuasiveness.

But, of course, these two prototypes are extremely simplified. Most practitioners fall somewhere between these two poles of neutrality and persuasiveness.  It is a complete and profound, unbiased and measured guide to the ideas and techniques that make family therapy such an exciting undertaking. Nicolet and Schwartz managed to be exhaustive without being tedious. Perhaps the secret to this is their charming writing style, or perhaps the way they try not to get lost in the abstract while maintaining a clear focus on clinical practice. In any case, this excellent book has long set the standard of excellence as the best introduction and guide to the practice of family therapy. 9Boston, Massachusetts

It is a complete and profound, unbiased and measured guide to the ideas and techniques that make family therapy such an exciting undertaking. Nicolet and Schwartz managed to be exhaustive without being tedious. Perhaps the secret to this is their charming writing style, or perhaps the way they try not to get lost in the abstract while maintaining a clear focus on clinical practice. In any case, this excellent book has long set the standard of excellence as the best introduction and guide to the practice of family therapy. 9Boston, Massachusetts  They have their own opinions on everything, and they bring up global topics for discussion - social constructivism, state provision, etc. While there is a temptation to use the acquaintance situation to say Important Words, I still prefer to be a little more personal. Working with dysfunctional families gives me the deepest pleasure, and I hope you will experience the same experience.

They have their own opinions on everything, and they bring up global topics for discussion - social constructivism, state provision, etc. While there is a temptation to use the acquaintance situation to say Important Words, I still prefer to be a little more personal. Working with dysfunctional families gives me the deepest pleasure, and I hope you will experience the same experience.

Well, more than hopeful, I guess. Some way has been found to make this work: to somehow maintain one's true vision while keeping the collaborator's eye in focus. It's probably the respect and affection for Dick, and something else between us, that makes it possible for us to work together.

Well, more than hopeful, I guess. Some way has been found to make this work: to somehow maintain one's true vision while keeping the collaborator's eye in focus. It's probably the respect and affection for Dick, and something else between us, that makes it possible for us to work together.  In a short period of thirty-three years, Melody witnessed my transformation from a timid young man, completely unintelligent about what it means to be a husband and father, into a shy middle-aged man who is still perplexed and continues his attempts. Sandy and Paul never cease to amaze me. My little red-haired girl (who can show off her abs as well as any football player) has just returned from West Africa after two years in the Peace Corps and is about to start her graduate studies. Am I proud of her? Incredible! And my son Paul (who knows firsthand what 9Williamsburg, Virginia

In a short period of thirty-three years, Melody witnessed my transformation from a timid young man, completely unintelligent about what it means to be a husband and father, into a shy middle-aged man who is still perplexed and continues his attempts. Sandy and Paul never cease to amaze me. My little red-haired girl (who can show off her abs as well as any football player) has just returned from West Africa after two years in the Peace Corps and is about to start her graduate studies. Am I proud of her? Incredible! And my son Paul (who knows firsthand what 9Williamsburg, Virginia  I am overwhelmed with completely mixed emotions - this is both pride in her achievements and nostalgia for our past relationship; confidence in her future and anxiety because of its uncertainty.

I am overwhelmed with completely mixed emotions - this is both pride in her achievements and nostalgia for our past relationship; confidence in her future and anxiety because of its uncertainty.

Thus, this book is a view of family therapy, and not the same truth about family therapy. I have my own addictions (and the model presented in Chapter 13 where those addictions are explored), and Mike has them. Our collaboration produces binocular vision that is more productive than a single glance.

Thus, this book is a view of family therapy, and not the same truth about family therapy. I have my own addictions (and the model presented in Chapter 13 where those addictions are explored), and Mike has them. Our collaboration produces binocular vision that is more productive than a single glance.