Mike wallace 60 minutes depression

Mike Wallace's Battle With Depression and Suicide

At his lowest and most desperate, a bottle of pills and a suicide note seemed like the only answer for the legendary journalist Mike Wallace.

The CBS 60 Minutes correspondent could make some of the most powerful leaders in the world sweat with nervousness, but Wallace will also be remembered as a voice and face for those who have suffered in silence with depression and other mental illnesses.

During a candid interview with psychiatrist Dr. Jeffrey Borenstein in 2009, Wallace said his first major bout of depression was triggered in 1984 after U.S. Army General William C. Westmoreland sued Wallace, along with several other names, for libel. Westmoreland was featured in the CBS documentary, "The Uncounted Enemy: A Vietnam Deception," in 1982, and Wallace was the chief correspondent for the investigative report.

"I was on trial for my life," Wallace, who died Saturday at 93, told Borenstein.

The public humiliation and questions of integrity made him feel "dead inside," Wallace wrote in January 2002 in an article for Guideposts. He couldn't eat, couldn't sleep and took sleeping pills in an attempt to get some shuteye. Even after revealing to a family doctor that he worried about his mental state, Wallace said the doctor told him, "You're a tough guy. You'll get through it."

When Wallace's wife Mary asked whether her husband could be suffering from clinical depression, the doctor reportedly told the couple, "Forget the word 'depression' because that'll be bad for your image."

But depression consumed him. Wallace described his rock bottom point, when he attempted suicide. "I have to get out of here," he recalled thinking.

"So I took a bunch of sleeping pills, wrote a note and ate them, and, as a result, I fell asleep," he said.

Mary found him unconscious in bed around 3 a.m. Doctors were able to pump his stomach and revive the journalist before he underwent psychological treatment.

In Guidepost, Wallace wrote of his life post-suicide attempt. "Before the new year, I was admitted to the hospital, 'suffering from exhaustion,' a CBS spokesman announced. "

"

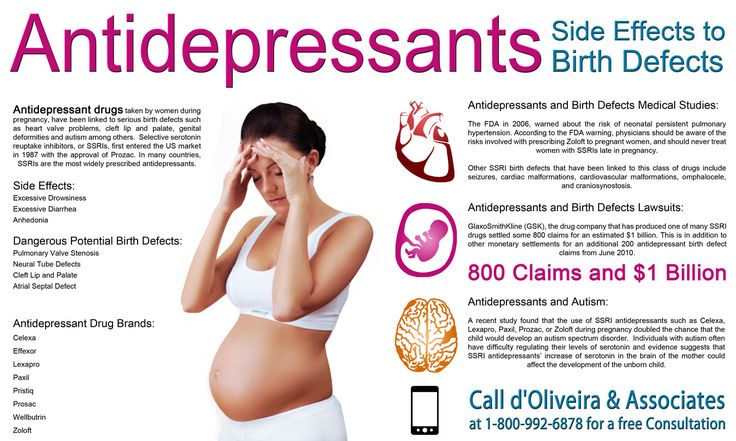

Talk therapy and antidepressant medications pulled Wallace through the severe bout of depression in the mid-1980s. While he admittedly had suffered a few more episodes, treatments allowed for better coping methods in the years after his suicide attempt.

When asked what advice he had for those suffering from depression, Wallace said, find a "good psychiatrist."

"You're not a nutcase if you want to go see a psychiatrist."

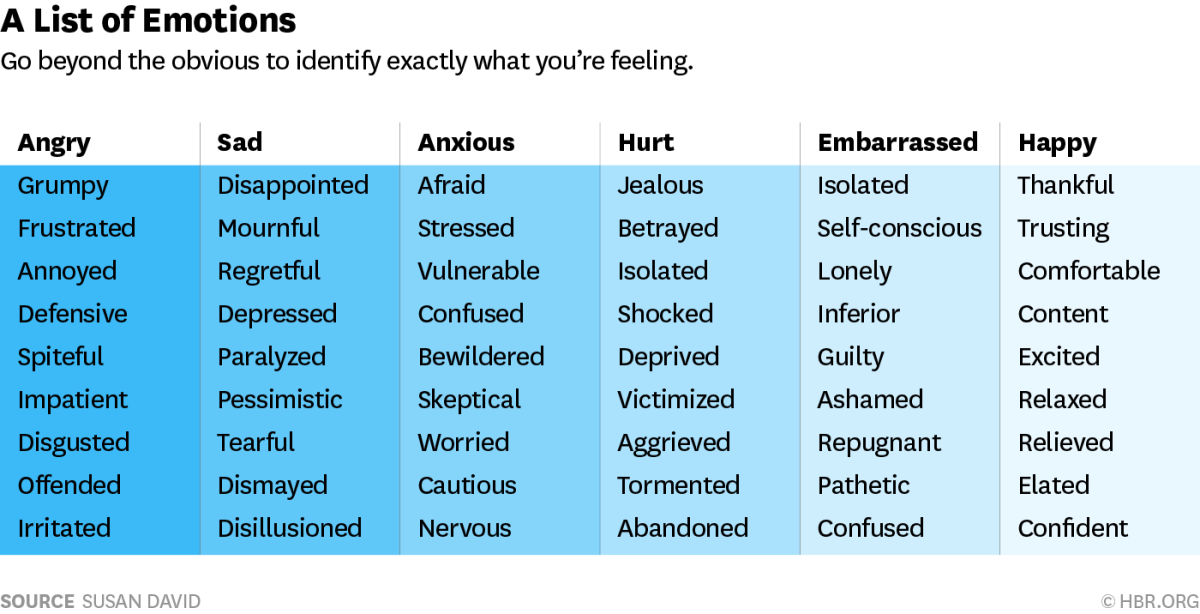

About 17 million Americans will suffer from depression at some point in their lives and according to the World Health Organization, about 5.8 percent of men and 9.5 percent of women worldwide will experience a depressive episode in any given year. Symptoms of depression include changes in sleep and appetite, inability to enjoy oneself and thoughts of hurting oneself.

Wallace acknowledged that the stigma of mental illness left many people, including himself, undiagnosed and untreated. While awareness and advocacy has curbed some of that taboo, there is still work to be done to remedy such perception of mental illness.

"Until very recently, individuals in positions of power, influence, and authority went to great lengths to hide their mental illness, such as depression, out of fear that the stigma associated with the illness might negatively impact their careers," said Dr. Amir Afkhami, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavior sciences at George Washington University. "However, the illness also allowed Wallace to have a familiarity with despair that allowed him to have empathy and a deep sense of connection with victims of injustice. This came across in his interviews during his tenure on 60 minutes and his work as a producer."

Experts say any time a public figure like Wallace opens up a discussion about mental illness, it is easier for others who may be suffering in silence to come forward and get treatment.

"What Mike Wallace did by his willingness to talk about his depressive illness was extraordinary," said Dr. Carol Bernstein, associate professor psychiatry at New York University School of Medicine. "That kind of openness with something that is usually shunned, avoided and stigmatized in our society was very brave and courageous of him."

"That kind of openness with something that is usually shunned, avoided and stigmatized in our society was very brave and courageous of him."

Guideposts Classics: Mike Wallace on Coping with Depression

In this story from January 2002, legendary newsman Mike Wallace shared his battle with depression with Guideposts readers.

Like most people, I’d had days when I felt blue and it took more of an effort than usual to get through the things I had to do.

But I always snapped out of it.

Before I knew it, I would be corralling another reluctant interview subject for 60 Minutes or trying to whip a crosscourt forehand past my opponent in a tennis match.

Relentless as ever, basically. (And a pain in the neck to my colleagues at CBS News, who claim that “Mike Wallace is here” are the four most dreaded words in the English language.)

So my down times invariably passed. Until the fall of 1984, that is, when I found myself suddenly struck, then overwhelmed, by something—an emptiness, a helplessness, an emotional and physical collapse—I’d never experienced before.

CBS News was embroiled in a high-profile lawsuit filed by General William Westmoreland over a documentary we had made about the Vietnam War, a special report for which I’d been the chief correspondent.

The case went to trial in early October. Every morning after Mary and I had breakfast, instead of heading to my office in the mid-Manhattan CBS News building on West 57th Street, I went downtown to the federal courthouse in Foley Square.

As I made my way into the courtroom, past the phalanx of reporters, I had a feeling their eyes on me were skeptical. A pretty jarring reversal of roles.

Still, that was nothing compared to having to listen to the other side’s lawyers call into question not only the accuracy of our documentary but also my own professional integrity.

You’d think I’d have just let the allegations roll off my back. After all, they weren’t true. Plus, as Mary reminded me, I had nearly 50 years in broadcasting to back up my good name.

But day after day, I sat trapped in room 318 at the courthouse, hearing people I didn’t even know attack the work I’d done. Given the way trials proceed, I didn’t have a chance to defend myself right then, so the accusations ate at me.

Given the way trials proceed, I didn’t have a chance to defend myself right then, so the accusations ate at me.

Doubts started to haunt me. Did I do something wrong? It was as if all my experience in radio and TV news didn’t count for anything anymore. What if I really am dishonest as a reporter? Dishonest as a person?

I tried to keep going on with life as usual. Whenever court was out of session, I worked on stories for 60 Minutes, doing research and interviews at night if necessary. But I had a hard time concentrating. Me, the guy who was famous for never giving up on a story, for asking such pointed questions, they made everyone from gangsters to movie stars to political leaders sweat.

In November I had a brief escape from the courtroom. I went to Ethiopia to cover the famine. The tragedy unfolding before my eyes in that drought-ravaged country, the human suffering I witnessed, resharpened my focus.

With something approaching my usual vigor, I did a segment for 60 Minutes. We edited it and got it on the air. Things are getting back to normal, I told myself.

We edited it and got it on the air. Things are getting back to normal, I told myself.

But as soon as I returned to the daily grind of the trial, that strange, dark malaise set in again. If anything, it was more pervasive than before, casting a pall over every part of my life the way the chill gray of winter seemed to blanket all of New York City.

I didn’t have an appetite, no matter what Mary put on the table. I could barely summon up the energy to get out of bed each morning, let alone run after balls hit to the corners of the tennis court. But at night I would lie awake, restless.

Sometimes I’d give up on sleep and switch on the television, looking for something on the late-night shows to get my mind off all my dark thoughts. And even when I could go back to the office and do the work I loved, I felt dead inside.

Maybe the only constant, the only part of my day-to-day life that hadn’t changed since the trial began, was what I said before I fell into bed at night. The Shema, one of the oldest and most important prayers of the Jewish faith.

The Shema, one of the oldest and most important prayers of the Jewish faith.

“Shema Yisrael Adonai Eloheinu Adonai Echad,” I would recite each night, as I had every night since I learned those words growing up in Brookline, Massachusetts. “Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One.”

I tried to draw strength from that prayer. And from Mary, who was always at my side, incredibly patient with me and my moods. Still, I’d catch her looking at me, her eyes full of worry.

One evening after we came home from the courthouse, she said, “Mike, you need to go see a doctor. Something’s wrong.”

I denied it. “The pressure of the trial’s getting to me,” I said. “I’ll be myself again once it’s over.”

Mary insisted on taking me to the doctor. I told him what I’d been experiencing, even swallowed my pride and asked, “What can you do to help me?”

“You don’t need help,” the doctor said. “You’re tough. Everybody knows that. You’ll bounce back in no time.” He warned me about the damage to my reputation if word got out I was having these emotional difficulties.

Mary was still concerned. “I don’t want to be right about this,” she told me on our way home, “but I think what you’re feeling goes way beyond being under stress. It’s taken over your life.”

Why is it that the people you love so often know you better than you know yourself? It took a complete physical collapse on the heels of a bout of the flu in December to make me concede I might be in as bad shape as Mary feared.

Right before the new year, I was admitted to the hospital, “suffering from exhaustion,” a CBS spokesman announced.

The truth, I was to learn from Dr. Marvin Kaplan, the psychiatrist I started seeing, was something I’d never imagined. My defenses were pretty much broken down by then.

When Dr. Kaplan asked me to give him a complete history of my symptoms, I poured out everything to this man who was all but a stranger to me. I told him about the trial; about the doubts that plagued me; about not being able to eat, sleep or enjoy the things I used to. “I just don’t see any way out of this,” I confessed. “It’s like I’m going out of my mind, I feel so low, so…hopeless. No, copeless.”

“I just don’t see any way out of this,” I confessed. “It’s like I’m going out of my mind, I feel so low, so…hopeless. No, copeless.”

“You feel as you do, Mr. Wallace, because you are experiencing clinical depression. Any stressful change in one’s life can trigger an episode, and some people are more prone to it than others.”

Depression? Wasn’t that some sign of emotional weakness?

“Depression is a disease,” Dr. Kaplan explained. “A disease that millions suffer from. The good news is that almost all depressed people can get better with treatment.”

First, he prescribed an antidepressant to relieve my symptoms. “Once it takes effect, it will put a pharmaceutical floor underneath your depression, so that you don’t sink any lower.” Then psychotherapy to help me gain insight into myself and figure out ways to cope with what was troubling me.

Within a week I was released from the hospital, continued my sessions with Dr. Kaplan and went back to work, nowhere near functioning at full capacity, and still too ashamed to tell people in the office what was going on. They must have wondered why Mike wasn’t acting like his usual demanding, abrasive self.

They must have wondered why Mike wasn’t acting like his usual demanding, abrasive self.

I was due to testify at the trial, so while the CBS attorneys prepared me legally, Dr. Kaplan got me ready emotionally. “You believe that if your side loses, it will be the end of your professional life,” he observed. “Why don’t we talk about how you will go on if you do lose?” A seemingly simple exercise, but it helped me regain some perspective.

Nearly five long months after the trial began, the day before I was to take the witness stand, the other side dropped the lawsuit. Obviously I was hugely relieved, but why didn’t I feel well again?

“That’s not how depression works,” Dr. Kaplan told me. “You don’t just snap out of a serious illness. You have to stay on the treatment and give it time to work.”

I did what he said, and sure enough, within a couple months I felt better. So much better, in fact, that I disregarded Dr. Kaplan’s advice and stopped taking the medication. Less than a week later, I happened to fall playing tennis and busted my left wrist.

And just like that, I was in deep again. As deep as the first time. I’d look out the window at all the people on the streets of New York. So much energy out there, so much going on, and all I wanted to do was turn my back on it. I didn’t care about anything except how miserable I felt and how I might end this pain.

Even so, I was still reluctant to acknowledge that I had what I had. The only ones who knew were Mary, Dr. Kaplan (who put me back on medication), and my son and daughter. And two good friends who were going through the same thing and were much braver than I in sharing their experiences: writer William Styron and humorist Art Buchwald.

Arty called me night after night. It was so reassuring to know that what I was feeling was normal for a depressed person, to talk to someone who’d been through it himself and come out the other side.

I continued to take refuge in prayer. When I couldn’t sleep at night, I’d turn to the affirmation that had been a mainstay for nearly as long as I could remember.

Shema Yisrael Adonai Eloheinu Adonai Echad. Those old, familiar words brought me back to my boyhood in Brookline, a town that was simply wonderful to grow up in. Back to a place and a time as far away from this oppressive darkness as I could imagine.

Eventually the depression lifted, as it had the first time, and I went back to doing what I loved—reporting stories, playing tennis, going out on the town with Mary. But grateful as I was for the help I’d been given during my darkest days, I still worried that people might think less of me if they knew about my depression, so I kept quiet about it.

Then came the night I was a guest on the late-night TV interview show Later with Bob Costas. Bob planned to devote the show to my work, but while I was talking to him about 60 Minutes, it suddenly occurred to me who might be watching television at one o’clock in the morning.

There are probably a lot of people listening at this moment who can’t get to sleep because they’re depressed, I thought. People who need to know that there’s hope.

People who need to know that there’s hope.

That’s when I finally went public about my depression. I wanted whoever might be listening and suffering to understand how low I’d sunk and how I was getting better every day with treatment. Help was out there for them too.

Depression, I’d come to see, was a part of me, something I’d always have to watch out for. The difference was, if it hit me again (and it did in 1993), I knew I couldn’t retreat into its depths. I had to keep taking my medication and going to therapy, keep talking to people.

In a way, that’s been the key to my still going strong for all these years. Every time I reach out beyond myself—to my family and friends, to my doctor, to my coworkers and the public to whom we bring the news, to the whole community of people who battle depressive disorders, and to the one I have turned to ever since I was a boy in Brookline—I find the hope that has led me out of the darkness.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.

Download your free ebook on happiness and personal growth.

Mike Wallace - Mike Wallace

For other people named Mike Wallace, see Michael Wallace.

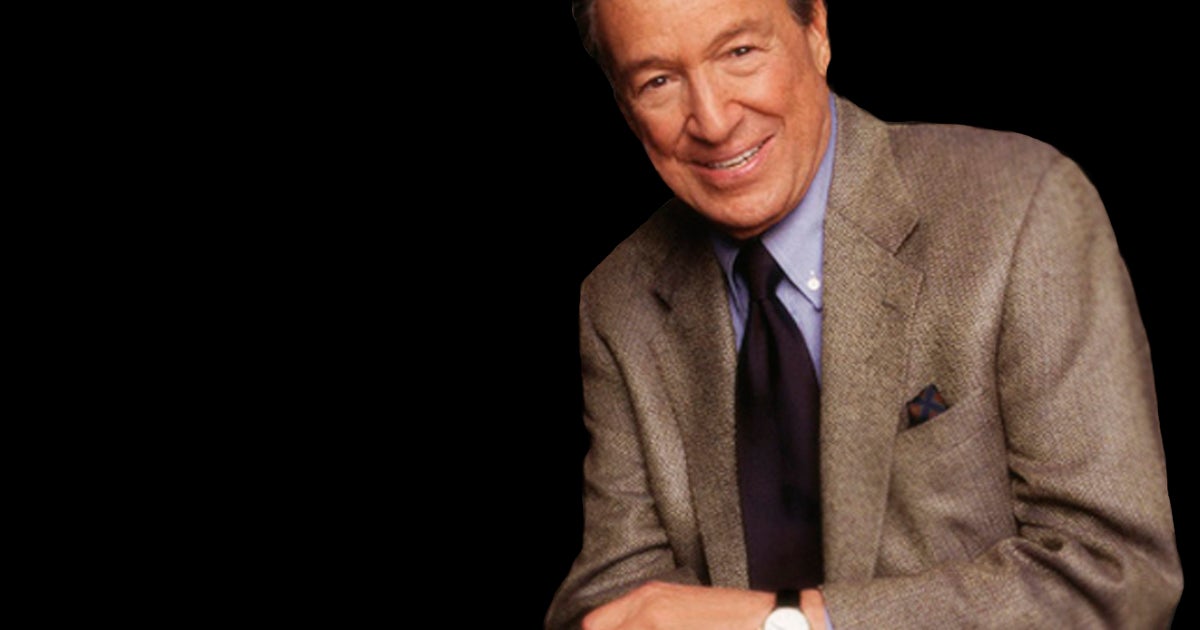

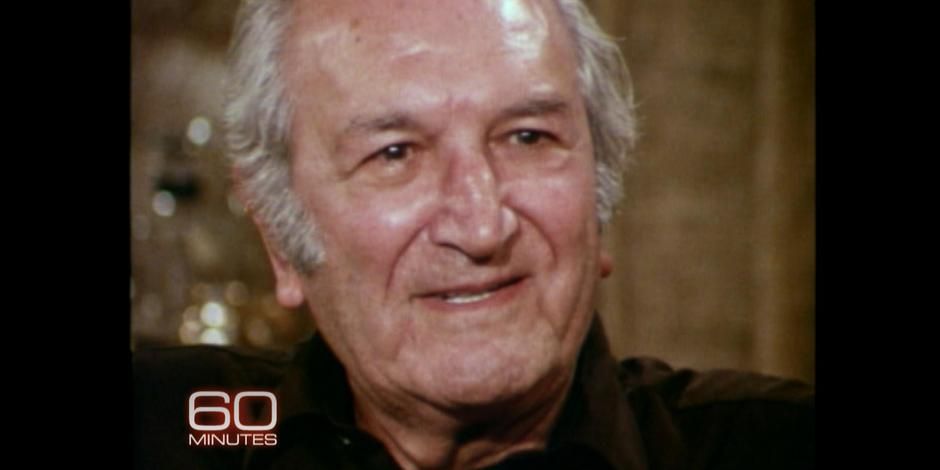

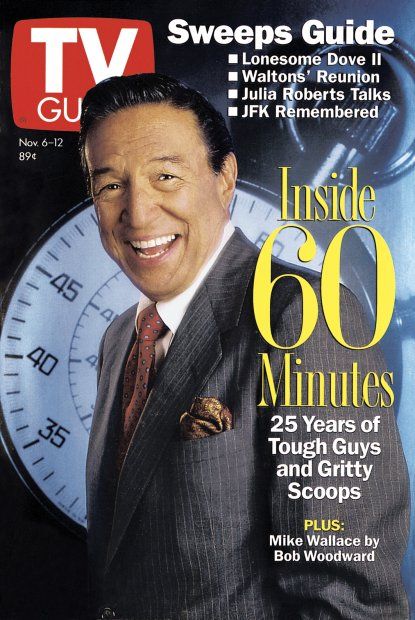

Myron Leon " Mike " Wallace (May 9, 1918 – April 7, 2012) was an American journalist, game show host, actor, and media personality. During his seventy-year career, he has interviewed a wide range of well-known newsmakers. He was one of the original correspondents for CBS' 60 Minutes , which debuted in 1968. Wallace retired as regular correspondent in 2006, but still made occasional appearances on the series until 2008.

Wallace interviewed many politicians, celebrities and scholars such as Pearl S. Buck, Deng Xiaoping, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Jiang Zemin, Ruhollah Khomeini, Kurt Waldheim, Frank Lloyd Wright, Yasser Arafat, Menachem Begin, Anwar Sadat, Manuel Noriega, John Nash, Gordon B. Hinckley, Vladimir Putin, Maria Callas, Barbra Streisand, Salvador Dali, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, William Carlos Williams, Mickey Cohen, Dean Reed, Jimmy Fratianno, Aldous Huxley, and Ayn Rand. [1] [2] [3]

[1] [2] [3]

Content

- 1 early years

- 2 Careers

- 2.1 1930–1940s: Radio

- 2.2 1940–1960s: Television

- 2.3 1960–2000: 60 60 60 minutes

- 3 Personal life

- 4 Death

- 5 Awards

- 6 Picturers

- 7 Biography

- 8 Autobiography

- 9 See also

- 10 used literature 9

- 11 further reading

- 12 external links

Early Years

Wallace, whose last name was originally Wallick [4] was born May 9, 1918 in Russian Massachusetts Jewish immigrant parents. [4] [5] He identified as a Jew and throughout his life claimed that this was his nationality (and not religion). His father was a grocer and insurance broker. [6] Wallace attended Brooklyn High School, Issue 1935 [7] Graduated from the University of Michigan four years later with a Bachelor of Arts. While in college, he was a reporter for Michigan Daily and belonged to the alpha-gamma chapter of the Zeta Beta Tau fraternity. [8]

While in college, he was a reporter for Michigan Daily and belonged to the alpha-gamma chapter of the Zeta Beta Tau fraternity. [8]

Career

1930s–1940s: radio

Wallace appeared as a guest on the popular radio quiz show Info Please on February 7, 1939, during his senior year at the University of Michigan. He spent his first summer after graduation on the air at the Interlochen Art Center. [9] His first radio job was as an announcer and continuity writer for WOOD radio in Grand Rapids, Michigan. This continued until 1940, when he moved to WXYZ radio in Detroit, Michigan as an announcer. He then became a freelance radio personality in Chicago.

Wallace enlisted in the US Navy in 1943 and during World War II served as liaison officer on USS Anthedon as a submarine tender. He did not see combat, but traveled to Hawaii, Australia and Subic Bay in the Philippines, then patrolled the South China Sea, the Philippine Sea and southern Japan. After demobilization at 19Wallace returned to Chicago in 1946.

After demobilization at 19Wallace returned to Chicago in 1946.

Wallace announced for the radio shows Curtain time , Ned Jordan: Secret Agent , King , Green Hornie , [10] Curtain time , [10] and Show spikes and Show spike Jones . [10] Sometimes reported [ by whom? ] Wallace announced The Lone Ranger , but Wallace said he never did. [11] C 1946 to 1948, he portrayed the title character on Flamond's Crime Papers on WGN and in syndication.

Wallace announced wrestling in Chicago in the late 1940s and early 1950s, sponsored by Tavern Pale beer.

In the late 1940s, Wallace was a staff announcer for the CBS radio network. He showed off his comic skills when he appeared opposite Spike Jones in dialogue. He was also the voice of Elgin-American in the company's advertisements for Groucho Marx with You Bet Your Life . As Myron Wallace, he portrayed New York detective Lou Kagel in a short-lived radio series. Waterfront Crime .

Waterfront Crime .

1940s-1960s: Television

In 1949, Wallace began to switch to new television. That same year, he starred under the name Myron Wallace in the short-lived police drama, Crime Ready . [12]

Wallace hosted a number of game shows in the 1950s, including Big Surprise , Who's the Boss? and Who pays? . Early in his career, Wallace was not primarily known as a broadcaster. During this period, it was not uncommon for newscasters to announce, run ads, and host game shows; Douglas Edwards, John Daly, John Cameron Swayze and Walter Cronkite hosted game shows. Wallace also hosted the pilot episode of Nothing but the Truth run by Bud Collier when it aired as Tell the Truth . Wallace occasionally acted as panelist on Tell the Truth during the 1950s. He has also filmed commercials for various products, including Procter & Gamble's signature acronym Fluffo.

Publicity photo for TV program Mike Wallace Interview , 1957

Wallace also hosted two nighttime interview programs, Night Beat (broadcast New York 1955–1957, only on DuMont with WABD) and Mike Wallace Interview on ABC 1957–1958. See also Profiles in Courage , section: Authorship disputes.

See also Profiles in Courage , section: Authorship disputes.

In 1959 Louis Lomax told Wallace about the Nation of Islam. Lomax and Wallace produced a five-part documentary about the organization, Hate Spawned by Hate , which aired during the week of July 13, 1959. The program marked the first time white people heard of the nation, its leader, Elijah Muhammad, and his charismatic spokesman, Malcolm X. [13]

By the early 1960s, Wallace's main income came from advertising Parliament cigarettes touting his "male meekness" (he had a contract with Philip Morris to offer his cigarettes as a result of the company's initial sponsorship of Mike Wallace Interview ) . From June 1961 to June 1962 he and Joyce Davidson conducted the New York interview program for Westinghouse Broadcasting [14] called PM East for one hour; it was paired with a half hour PM West which was hosted by San Francisco Chronicle television critic Terrence O'Flaherty. Westinghouse syndicated the series to its own TV stations and to several other cities. Residents of the southern and southwestern states and metropolitan areas of Chicago and Philadelphia were unable to watch it.

Westinghouse syndicated the series to its own TV stations and to several other cities. Residents of the southern and southwestern states and metropolitan areas of Chicago and Philadelphia were unable to watch it.

A frequent guest on the PM East segment was Barbra Streisand, although only audio recordings of some of her conversations with Wallace survive, [14] while Westinghouse was wiping down the videotapes. Also early 19In the 60s, Wallace was the host of the David Wolper –Produced biography series.

After the death of his eldest son in 1962, Wallace decided to return to the news and hosted an early version of CBS Morning News from 1963 to 1966. In 1964, he interviewed Malcolm X, who remarked half-jokingly, "I must be dead by now." [15] The black leader was assassinated a few months later in February 1965.

In 1967, Wallace anchored documentary CBS Records: Homosexuals . "The average homosexual, if there is one, is promiscuous," Wallace said in the article. "He is not interested in and incapable of a long-term relationship like that of a heterosexual marriage. His sex life, his personal life consists of a series of casual meetings in the clubs and bars that he inhabits. And even on the streets of the city. The city is a pickup truck, a one night, these are the characteristics of a homosexual relationship.” [16] Wallace later regretted his part in this episode. "I should have known better," he said in 1992. [17] Speaking in 1996, Wallace stated: "That is - God help us - what we understood about the homosexual lifestyle only twenty-five years ago, because no one came out of the closet and because it is what we heard from doctors is what [psychiatrist Charles] Socarides told us it was a disgrace." [17]

"He is not interested in and incapable of a long-term relationship like that of a heterosexual marriage. His sex life, his personal life consists of a series of casual meetings in the clubs and bars that he inhabits. And even on the streets of the city. The city is a pickup truck, a one night, these are the characteristics of a homosexual relationship.” [16] Wallace later regretted his part in this episode. "I should have known better," he said in 1992. [17] Speaking in 1996, Wallace stated: "That is - God help us - what we understood about the homosexual lifestyle only twenty-five years ago, because no one came out of the closet and because it is what we heard from doctors is what [psychiatrist Charles] Socarides told us it was a disgrace." [17]

0011 60 minutes

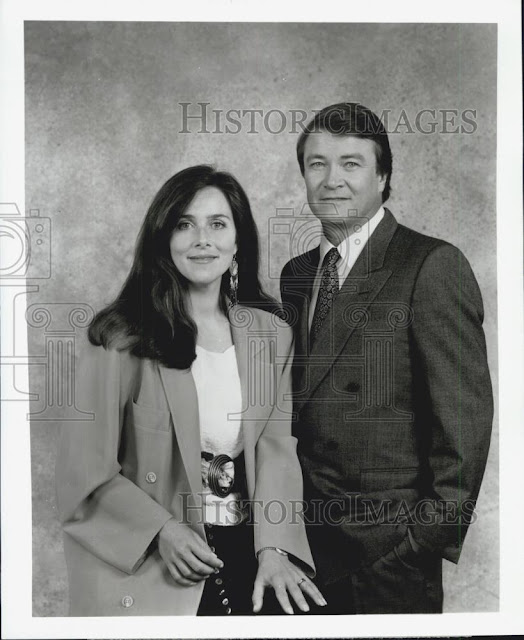

Wallace and Harry Reasoner on 60 minutes premiere 1968

Wallace's career as lead reporter on 60 minutes has led to clashes with interviewees and allegations of misconduct by female colleagues. During an interview with Louis Farrakhan, Wallace claimed that Nigeria was the most corrupt country in the world. Farrakhan immediately responded that Americans were incapable of judging morality, stating: “Did Nigeria drop the atomic bomb that killed people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki? They killed millions of Native Americans? »« Can you imagine a more corrupt country? Wallace asked. "I live in one of them," Farrakhan said. [18]

During an interview with Louis Farrakhan, Wallace claimed that Nigeria was the most corrupt country in the world. Farrakhan immediately responded that Americans were incapable of judging morality, stating: “Did Nigeria drop the atomic bomb that killed people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki? They killed millions of Native Americans? »« Can you imagine a more corrupt country? Wallace asked. "I live in one of them," Farrakhan said. [18]

Wallace interviewed General William Westmoreland for special Enemy Unaccounted for: The Vietnam Deception which aired on January 23, 1982. [19] Westmoreland then sued Wallace and CBS for defamation. The trial ended in February 1985 when the case was settled out of court just before it went to the jury. Each party agreed to pay their own expenses and attorneys' fees, and CBS released a clarification of their intentions for the original story.

In 1981, Wallace was forced to apologize for the racial slurs he had made against blacks and Hispanics. During a prep break 60 minutes In a bank report that was accused of defrauding low-income Californians, Wallace was caught on tape joking that "you bet [contracts] are hard to read if you read them over a watermelon or tacos!" [20] [21] [22]

During a prep break 60 minutes In a bank report that was accused of defrauding low-income Californians, Wallace was caught on tape joking that "you bet [contracts] are hard to read if you read them over a watermelon or tacos!" [20] [21] [22]

Attention was drawn to this incident again a few years later when protests erupted after Wallace was chosen to deliver the university admissions address during a ceremony in during which Nelson Mandela was awarded an honorary doctorate in absentia for his fight against racism. Wallace initially called the protesters' complaint "absolutely stupid". [23] However, he subsequently apologized for his earlier remark and added that when he was a student decades ago on the same campus, “although it never caused me any serious difficulty here ... I was acutely aware that that I am Jewish, and to be quick to discover grievances, real or imagined... We Jews felt a kind of kinship [with blacks]," but "Lord knows, we didn't ride the same ship of slaves. " [24]

" [24]

Wallace's reputation was retrospectively affected by his admission that he harassed female colleagues at 60 minutes for many years. "Back in the 1970s and 1980s, 60 minutes Correspondent Mike Wallace was famous for placing his hand on the backs of CBS News employees and unfastening their bras. "It was no secret. I did it," Wallace said Rolling Stone Magazine 1991. " [25] In 2018, sexual harassment complaints on 60 minutes led to the resignation of executive producer Jeff Fager, who ran the news show for 36 years. He resigned a few months after Ronan Farrow's July 27 story. New Yorker . [26] Farrow's story not only accuses Fager of ignoring and allowing misconduct by several high-profile male producers. 60 minutes , but Farrow also cited former employees who accused Fager himself of wrongdoing. [27]

On March 14, 2006, Wallace announced his retirement. 60 minutes after 37 years of working with the program. He continued to work for CBS News as "Correspondent of Honor", albeit at a slower pace. [28] In August 2006, Wallace interviewed the President of Iran. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. [29] Wallace's last CBS interview was with former baseball star Roger Clemens in January 2008. 60 minutes . [30] Wallace's previously good health (described by Morley Safer in 2006 as "an energetic man half his age") began to deteriorate, and in June 2008 his son Chris said his father would not return to television. [31]

He continued to work for CBS News as "Correspondent of Honor", albeit at a slower pace. [28] In August 2006, Wallace interviewed the President of Iran. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. [29] Wallace's last CBS interview was with former baseball star Roger Clemens in January 2008. 60 minutes . [30] Wallace's previously good health (described by Morley Safer in 2006 as "an energetic man half his age") began to deteriorate, and in June 2008 his son Chris said his father would not return to television. [31]

Wallace expressed regret at not being interviewed by First Lady Pat Nixon. [32]

Personal life

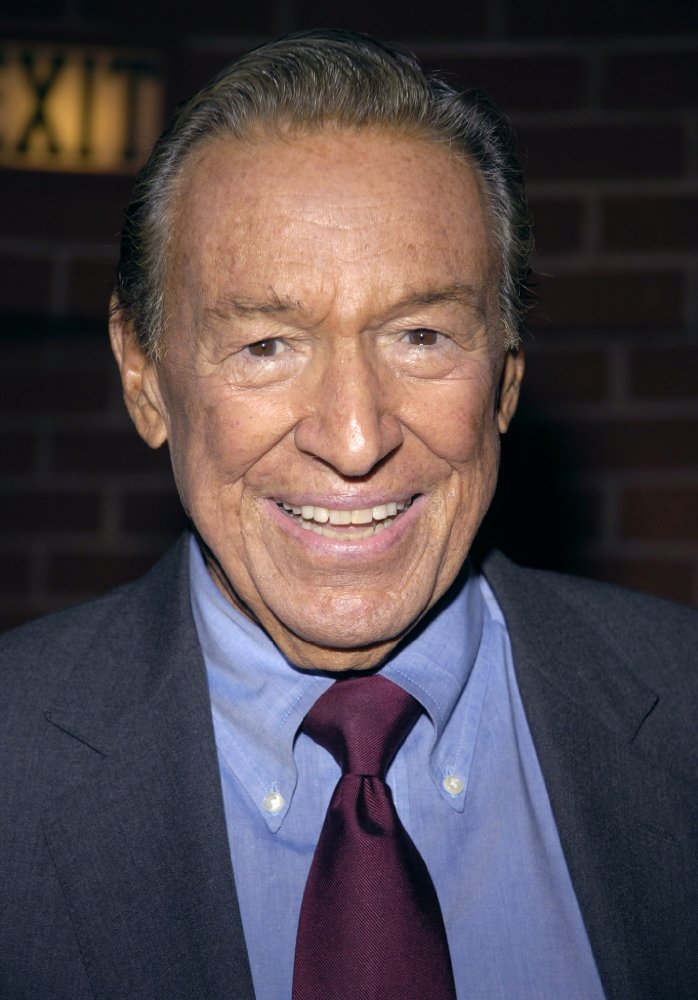

Wallace in 2007

Wallace had two children with his first wife, Norma Kafan. [33] Wallace's youngest son, Chris, is also a journalist. His eldest son Peter died at age 19 in a mountaineering accident in Greece in 1964. [34]

Wallace was married from 1949 to 1954 to Patricia "Buff" Cobb, an actress and stepdaughter of Gladys Swarthut . The couple hosted the show "Mike and Buff" on CBS television in early 1950s. They also hosted "All Around Town" in 1951 and 1952. [35]

The couple hosted the show "Mike and Buff" on CBS television in early 1950s. They also hosted "All Around Town" in 1951 and 1952. [35]

For many years, Wallace unknowingly suffered from depression. In an article he wrote for Landmarks , Wallace said, "I had days when I felt sad and needed more effort than usual to get through what I needed to do." [36] His condition worsened in 1984 after General William Westmoreland filed a lawsuit. $120 million libel lawsuit against Wallace and CBS over claims made in Documentary Enemy Countless: Vietnam Deception (1982). Westmoreland claimed that in the documentary he looked like he was being manipulated by the intellect. Lawsuit, Westmoreland v. CBS Later dropped after CBS released a statement explaining that it was never their intention to portray the general as disloyal or unpatriotic. During the proceedings, Wallace was hospitalized with a diagnosis of exhaustion. His wife Mary forced him to see a doctor, who diagnosed Wallace with clinical depression. He was prescribed an antidepressant and underwent psychotherapy. Believing it would be seen as a weakness, Wallace kept his depression a secret until he revealed it in an interview with Bob Costas on Costas' late-night talk show, Later . [36] In a later interview with colleague Morley Seifer, he admitted to having attempted suicide around 1986. [37]

He was prescribed an antidepressant and underwent psychotherapy. Believing it would be seen as a weakness, Wallace kept his depression a secret until he revealed it in an interview with Bob Costas on Costas' late-night talk show, Later . [36] In a later interview with colleague Morley Seifer, he admitted to having attempted suicide around 1986. [37]

Wallace received a pacemaker over 20 years before his death and underwent triple bypass surgery in January 2008. [4] He spent the last few years of his life in an institutional setting. [4] In 2011, CNN host Larry King visited him and reported that he was in good spirits, but his physical condition was deteriorating noticeably.

Wallace considered himself a moderate in politics. He was a friend of Nancy Reagan and her family for over 75 years. [38] Nixon wanted Wallace to be his press secretary. Fox News stated, "He didn't fit the stereotype of an Eastern liberal journalist. " Interviewed by his son on Fox News Sunday , he was asked if he understands why people are angry with the mainstream media. “They think they are wide-eyed communists; liberals,” Mike replied, dismissing the idea as “damn stupid.” [39]

" Interviewed by his son on Fox News Sunday , he was asked if he understands why people are angry with the mainstream media. “They think they are wide-eyed communists; liberals,” Mike replied, dismissing the idea as “damn stupid.” [39]

Death

Wallace died at his residence in New Canaan, Connecticut of natural causes on April 7, 2012 at the age of 93. [4] [40] The night after Wallace's death, Morley Seifer announced his death 60 minutes . On April 15, 2012, the full episode of aired 60 minutes aired in memory of Wallace. [41] [42] [43]

Awards

In 1989, Wallace was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from the University of Pennsylvania. [44] Among Wallace's professional awards are 21 Emmy Awards, [4] among them a report a few weeks before the 9/11 attack for investigating the Soviet Union's first smallpox program and concern for terrorism. He has also won three Columbia DuPont University Alfred Awards, three George Foster Peabody Awards, a Robert E. Sherwood Award, a University of Southern California School of Journalism Excellence Award, Gold Plate American Academy of Achievement, [45] and the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award in the International Broadcasting category. In September 2003, Wallace received the 20th Primetime Emmy Lifetime Achievement Award. [ citation needed ] Most recently, on October 13, 2007, Wallace received the University of Illinois Journalism Lifetime Achievement Award.

He has also won three Columbia DuPont University Alfred Awards, three George Foster Peabody Awards, a Robert E. Sherwood Award, a University of Southern California School of Journalism Excellence Award, Gold Plate American Academy of Achievement, [45] and the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award in the International Broadcasting category. In September 2003, Wallace received the 20th Primetime Emmy Lifetime Achievement Award. [ citation needed ] Most recently, on October 13, 2007, Wallace received the University of Illinois Journalism Lifetime Achievement Award.

- 1991: Paul White Digital News Radio and Television Association Award [46]

- 1999: Gerald Loeb Award for Network and Major Market Television for research into the international pharmaceutical industry [47]

Fictional portrayals

Wallace was played by actor Christopher Plummer in the 1999 feature film Insider . The script was based on the Vanity Fair article "The Man Who Knew Too Much" by Marie Brenner, in which Wallace succumbed to corporate pressure to kill a story about Jeffrey Wiegand, as a whistleblower attempting to expose Brown and Williamson's dangerous business practices in the manufacture of cigarettes. Wallace disliked his on-screen portrayal and claimed that he actually really wanted Wigand's story to be broadcast in full.

Wallace disliked his on-screen portrayal and claimed that he actually really wanted Wigand's story to be broadcast in full.

Wallace was played by actor Stephen Rowe in the stage version of Frost/Nixon , but he was left out of the script for the 2008 film adaptation and hence the film itself. In the 1999 American television film Hugh Hefner: Unauthorized , Wallace is portrayed by Mark Harelik. In the film A Face in the Crowd (1957), Wallace portrayed himself.

Biographies

- Reider, Peter. Mike Wallace: A Life of . New York: Thomas Dunn Books, 2012. ISBN 0-312-54339-5.

Autobiographies

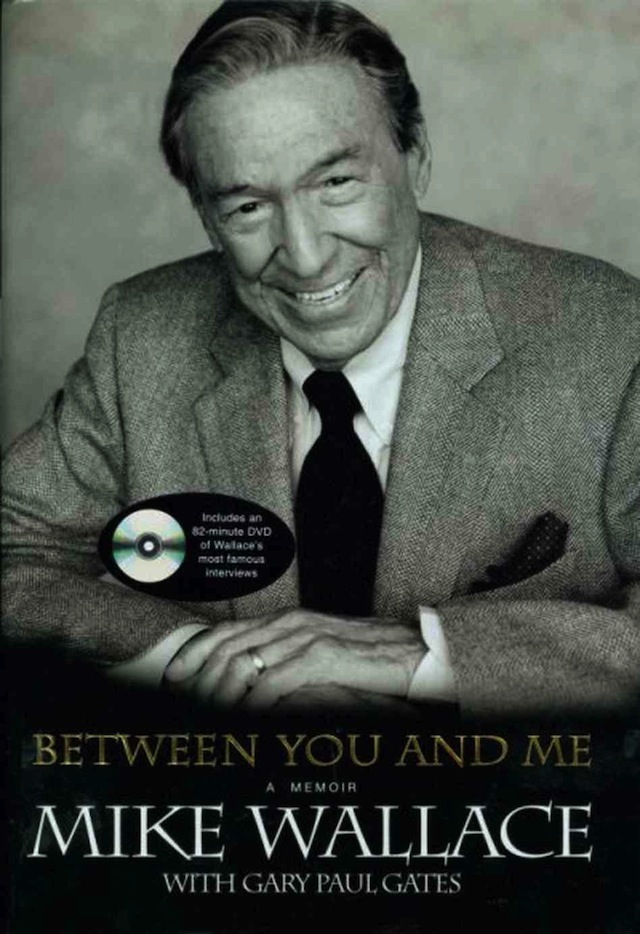

- Close Encounters: Mike Wallace's Own Story . New York: William Morrow, 1984. ISBN 0-688-01116-0 (co-authored with Gary Paul Gates).

- Between you and me: memories . New York: Hyperion, 2005 (co-authored with Gary Paul Gates).

See also

- Hatred born of hate

- Mike Wallace interview

- 9 Brozan, Nadine.

"Chronicle", NYT , March 16, 1993 Retrieved February 5, 2008 "Mike Wallace helps his old school, Brookline High School, at a charity event - unusual for a Massachusetts public school - tomorrow night in New York Mr. Wallace, class of '35, interviews Acting Principal Dr. Robert J. Weintraub at a cocktail party expected to bring about 60 Brooklyn alumni to the varsity club on West 54th Street.'9 "Media: Reporting Prizes Announced". New York Times . May 26, 1999. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

"Chronicle", NYT , March 16, 1993 Retrieved February 5, 2008 "Mike Wallace helps his old school, Brookline High School, at a charity event - unusual for a Massachusetts public school - tomorrow night in New York Mr. Wallace, class of '35, interviews Acting Principal Dr. Robert J. Weintraub at a cocktail party expected to bring about 60 Brooklyn alumni to the varsity club on West 54th Street.'9 "Media: Reporting Prizes Announced". New York Times . May 26, 1999. Retrieved February 6, 2019. - Cooper, Rand Richards (September 27, 2019). "From Muckraking to Clickbait: 'Mike Wallace is here'".0028

- 1986 interviews

- Mike Wallace interviews archives of his late 1950s New York interview show. Hosted by the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

- Mike Wallace starts "NewsBeat" on WNTA, March/1959.

- "Mike Wallace collected news and commentary." New York Times .

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Mike Wallace on Charlie Rose

- Mike Wallace interview on Archives of American Television

- Works by or about Mike Wallace in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Mike Wallace on Topic

- Mike Wallace on Fresh Air

- One on One with Mike Wallace on The Saturday Evening 2 9002 Post Mike

Wallace at Find a Grave - FBI Records: Vault - Myron Leon "Mike" Wallace on vault.fbi.gov

further reading

Mike Wallace - biography and family

BiographyMike joined the US Navy at 1943rd and served as a liaison officer during World War II aboard a submarine. For three years he did not see combat, traveling to the Hawaiian Islands, Australia and Subic Bay in the Philippines and patrolling the South China and Philippine Seas and waters south of Japan. After the war, Wallace returned to Chicago.

Mike Wallace was born May 9, 1918. Veteran American television journalist, host of game shows and media projects.

As a correspondent for the CBS news program '60 Minutes', Wallace made his debut at 1969th. During his 35-year career, he has interviewed a range of distinguished people, including Ayatollah Khomeini, Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, Ronald and Nancy Reagan, Vladimir Putin, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Manuel Noriega, Jeffrey Wigand, John F. Nash and many others. His program was very popular, and the impartial tactics he chose during a conversation with invited guests only fueled interest in his show. In 2006, an outstanding TV journalist filed a resignation

but still appears frequently on '60 Minutes'.

Myron Leon 'Mike' Wallace (Wollechinsky) was born on May 9, 1918 in Brooklyn, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston, USA, to Russian-Jewish parents. He graduated from Brookline High School in 1935 and then received a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Michigan in 1939.

As a student, Wallace appeared as a guest on the popular radio quiz show 'Information Please'. And the first work on the radio was the position of an announcer on the wave of 'WOOD' in Grand Rapids, Michigan. After a position as an announcer at radio station 'WXYZ' in Detroit, Wallace became a freelance radio worker in Chicago, Illinois.

Mike joined the US Navy in 1943 and served as a communications officer

and during World War II aboard a submarine. For three years he did not see combat, traveling to the Hawaiian Islands, Australia and Subic Bay in the Philippines and patrolling the South China and Philippine Seas and waters south of Japan. After the war, Wallace returned to Chicago.

By the late 1940s, Mike was a full-time news anchor for the CBS radio network. He was given the rare opportunity to showcase his comic talents by participating in a dialogue program with noted satirist musician Spike Jones. At 19Mike hosted a number of TV game shows in the 1950s, including the game shows 'The Big Surprise', 'Who's the Boss?' and 'Who Pays?'.

He also hosted the pilot episode of

He also hosted the pilot episode of 'Nothing but the Truth' and occasionally appeared on the game show 'To Tell the Truth'.

Wallace hosted the nightly programs 'Night Beat' and 'The Mike Wallace Interview', and by the early 1960s, with advertising experience under his belt, his main income was from advertising campaigns for 'Parliament' cigarettes. He became the host of the hour-long talk show 'PM East' and after the death of his eldest son Peter in the mountains, he decided to return to the news. From 19From 1963 to 1966, he hosted the original version of CBS's 'Morning News' morning newscast.

In 1968, Wallace became the creator of the popular TV show '60 Minutes', which turned the TV interview genre into a real art. He interviewed politicians, actors, writers, musicians and businessmen, and after 37 years devoted to his news program on CBS, on March 14, 2006, he decided to leave the honorary position of a television journalist, but to continue working in CBS news in as an honorary correspondent.

Learn more - 9 Brozan, Nadine.