Methadone treatment during pregnancy

Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder Before, During, and After Pregnancy

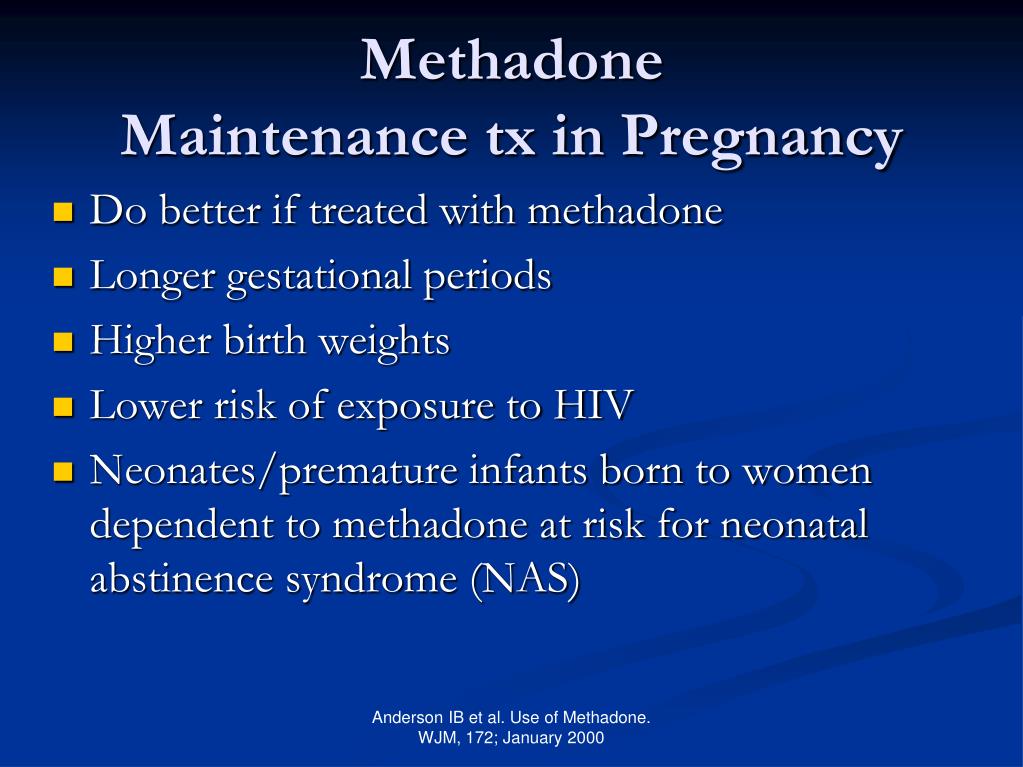

Creating a treatment plan for opioid use disorder (OUD), that may include a medication for OUD such as methadone or buprenorphine, before pregnancy can help increase the chances of a healthy pregnancy.

Clinical guidance for pregnant people with OUD is available from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). As noted in their recommendations, quickly stopping opioids during pregnancy is not recommended, as it can have serious consequences, including preterm labor, fetal distress, or miscarriage. Current clinical recommendations for pregnant people with OUD include medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), rather than supervised withdrawal, due to a higher likelihood of better outcomes and a reduced risk of relapse.

Medication for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD) During Pregnancy

Medication for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD) refers to the use of medication to treat opioid use disorder. This type of treatment can lead to more favorable outcomes.

Methadone and buprenorphine are first-line therapy options for pregnant people with OUD. ACOG and SAMHSA recommend treatment with methadone or buprenorphine for pregnant people with OUD, in conjunction with behavioral therapy and medical services. While some treatment centers use naltrexone to treat OUD in pregnant people, current information on its safety during pregnancy is limited. ACOG recommends that if a woman is stable on naltrexone prior to pregnancy, the decision regarding whether to continue naltrexone treatment during pregnancy should involve a careful discussion between the provider and the patient, weighing the limited safety data on naltrexone with the potential risk of relapse with discontinuation of treatment.

Pregnant people with OUD should be encouraged to start treatment with methadone or buprenorphine. Like many medications taken during pregnancy, MOUD has unique benefits and risks to pregnant women and their babies. It is important for healthcare providers to and people who are pregnant with OUD to work together to manage medical care during pregnancy and after delivery. Coordination of care between a prenatal care provider and a specialist with expertise in opioid use is important for pregnant people with OUD.

It is important for healthcare providers to and people who are pregnant with OUD to work together to manage medical care during pregnancy and after delivery. Coordination of care between a prenatal care provider and a specialist with expertise in opioid use is important for pregnant people with OUD.

It is important to recognize that neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) is an expected condition that can follow exposure to MOUD. A concern for NAS alone should not deter healthcare providers from prescribing MOUD. Close collaboration with the pediatric care team can help ensure that infants born to people who used opioids during pregnancy are monitored for NAS and receive appropriate treatment, as well as be referred to needed services.

Talk with your healthcare provider to learn more about treatment options for OUD during pregnancy. If you or someone close to you needs help for a substance use disorder, talk to a healthcare provider or call SAMHSA’s National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

Treatment for an Infant Affected by Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS), including Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome (NOWS)

AAP’s Clinical Report, Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome (NOWS), provides guidelines for managing the care of infants with long-term opioid exposure during pregnancy.

Treatment for NAS depends on many factors:

- The opioids or other medicines the newborn was exposed to during pregnancy;

- The newborn’s overall health; and

- Whether the infant was born full-term (after 37 weeks of pregnancy).

When signs of NOWS are first identified, care that involves and supports the mother is very important. The infant may need treatment with medication if there is no improvement or if the infant develops severe withdrawal.

Other strategies for managing NAS include:

- Placing the infant in a dark, quiet area to lessen both light and sound;

- Swaddling the infant;

- Gently rocking the infant or using other positioning or comforting methods;

- Providing frequent, small amounts of high-calorie formula or breast milk to help with feeding problems; or

- Allowing the infant to stay in the same hospital room as the mother.

Management of NAS with the Use of Medication

NAS conditions result from newborns’ withdrawal from certain substances that they were exposed to before birth. NOWS is a subset of NAS and is specific to opioid withdrawal during the first 28 days of life.

Some babies, especially those with more severe withdrawal signs, may need medications, such as liquid oral morphine or liquid oral methadone, in addition to the other care strategies listed above that do not include the use of medicines (SAHMSA’s Factsheet 10). Medicines can help prevent seizures, improve feeding, stop diarrhea, decrease agitation, and control other severe symptoms. Once the signs of withdrawal seem to be controlled, the dosage of medication is gradually decreased. Babies being treated for NAS with medicines may need to stay longer in the hospital after birth.

Breastfeeding

In general, breastfeeding is encouraged for newborns with NAS. However, sometimes breastfeeding is not recommended. For example, breastfeeding is not recommended if mothers are using illicit drugs, are using more than one drug, or are HIV-positive. For more information, read Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome (NOWS) and Clinical Guidance for Treating Pregnant and Parenting Women with Opioid Use Disorder and their Infants

For example, breastfeeding is not recommended if mothers are using illicit drugs, are using more than one drug, or are HIV-positive. For more information, read Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome (NOWS) and Clinical Guidance for Treating Pregnant and Parenting Women with Opioid Use Disorder and their Infants

After Hospital Discharge

The discharge plan for infants treated for NAS may include home visits and services, such as parenting support and links to home nurses and social workers. The plan may also include referrals to healthcare workers who know about NAS and are available to the family immediately after discharge. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends this simple checklist to help with discharge planning and proper care after leaving the hospital.

Plans of Safe Care

Families and caregivers with an infant treated for NAS or other prenatal substance exposure should receive a Plan of Safe Care. The goals of the plan are to strengthen the family, keep the child safe, and link the family with services in their community. The Plan of Safe Care is individually designed to address the needs for each infant, caregiver, and family. Examples include substance use treatment and available services and support to meet health and developmental needs. Plans can identify agencies within the community that provide services. Plans can also help guide communication and coordination.

The Plan of Safe Care is individually designed to address the needs for each infant, caregiver, and family. Examples include substance use treatment and available services and support to meet health and developmental needs. Plans can identify agencies within the community that provide services. Plans can also help guide communication and coordination.

Treating Opioid Use Disorder During Pregnancy

Policy Brief

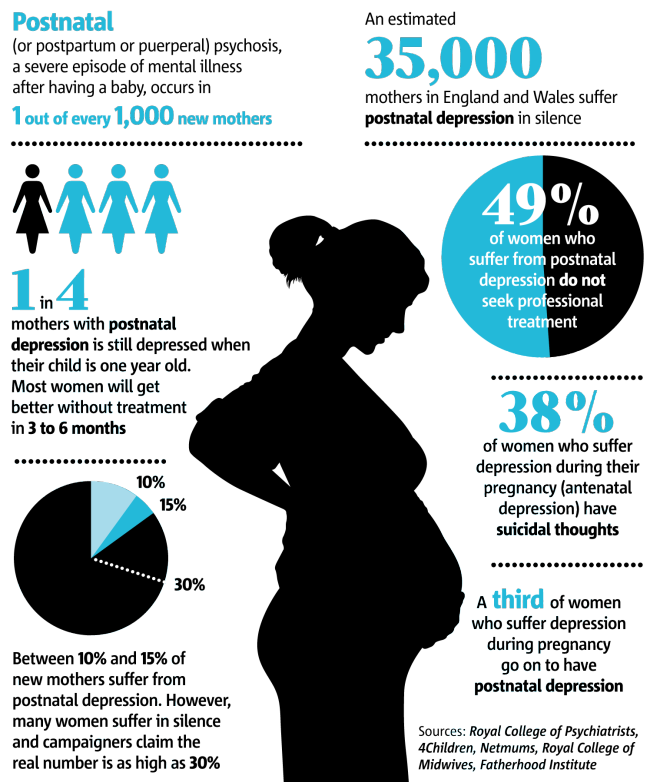

Risks of Opioid Misuse During Pregnancy

Untreated opioid use disorder during pregnancy can have devastating consequences for the unborn baby. Fluctuating levels of opioids in the mother may expose the fetus to repeated periods of withdrawal, which can harm placenta function.1,2

Other direct physical risks include:1-3

- neonatal abstinence syndrome

- stunted growth

- preterm labor

- fetal convulsions

- fetal death

Image

Source: Villapiano NLG, Winkelman TNA, Kozhimannil KB, Davis MM, Patrick SW. Rural and Urban Differences in Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome and Maternal Opioid Use, 2004 to 2013. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(2):194-196. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.3750.

Rural and Urban Differences in Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome and Maternal Opioid Use, 2004 to 2013. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(2):194-196. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.3750. Other indirect risks to the fetus include:

- increased risk for maternal infection (e.g., HIV, HBV, HCV)4

- malnutrition and poor prenatal care3

- dangers from drug seeking (e.g., violence and incarceration)1,3

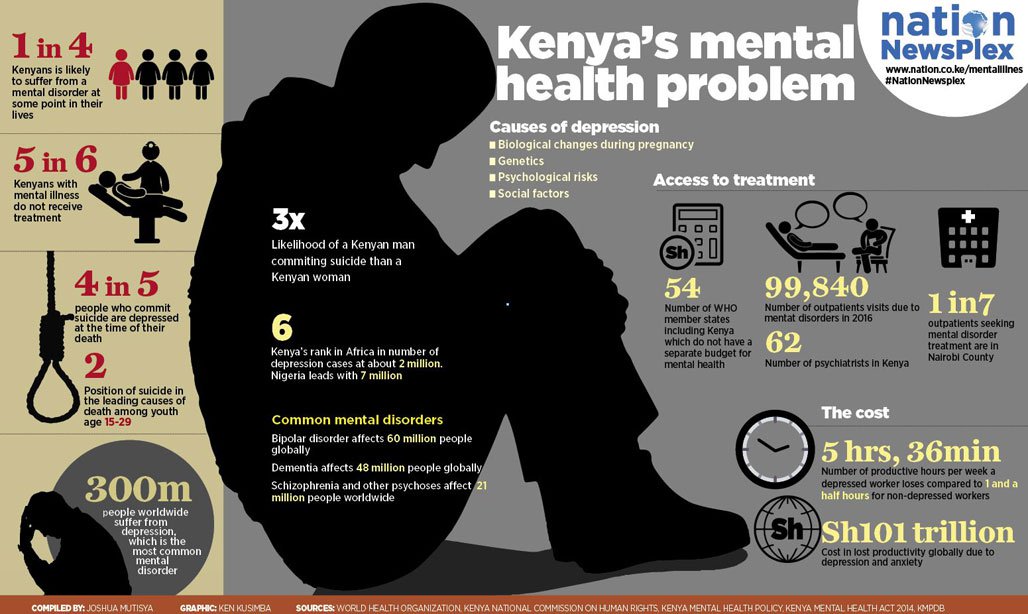

What is Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome?

Neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) occurs when an infant becomes dependent on opioids or other drugs used by the mother during pregnancy. The infant experiences withdrawal symptoms that can include (but are not limited to) tremors, diarrhea, fever, irritability, seizures, and difficulty feeding.5

NAS increased nearly fivefold nationally between 2000 to 2012,6,7 coinciding with rising rates of opioid prescribing to pregnant women.8,9

Science Driven SolutionsEvidence-Based Treatment

Buprenorphine and methadone have both been shown to be safe and effective treatments for opioid use disorder during pregnancy. 11 While NAS may still occur in babies whose mothers received these medications, it is less severe than in the absence of treatment.10,12 Research does not support reducing medication dose to prevent NAS, as it may lead to increased illicit drug use, resulting in greater risk to the fetus.2

11 While NAS may still occur in babies whose mothers received these medications, it is less severe than in the absence of treatment.10,12 Research does not support reducing medication dose to prevent NAS, as it may lead to increased illicit drug use, resulting in greater risk to the fetus.2

Methadone vs. Buprenorphine

A recent meta-analysis showed that methadone is associated with higher treatment retention. However, buprenorphine resulted in:10

- 10 percent lower incidence of NAS

- decreased neonatal treatment time by 8.46 days

- less morphine needed for NAS treatment by 3.6mg

Patients should work with their doctor to determine which medication is best for them.

Breastfeeding During Treatment

Although breastfeeding is typically low among mothers with opioid use disorder,11 studies have found that breastfeeding can reduce length of hospital stay and need for morphine treatment in infants. Unless there are specific medical concerns (e.g., maternal HIV infection), encouraging mothers to breastfeed and swaddle newborns may ease infant NAS symptoms and improve bonding.1,2,13

Unless there are specific medical concerns (e.g., maternal HIV infection), encouraging mothers to breastfeed and swaddle newborns may ease infant NAS symptoms and improve bonding.1,2,13

Methadone and Buprenorphine Can Effectively Treat Opioid Use Disorder During Pregnancy

Methadone has been used to treat pregnant women with opioid use disorder since the 1970s and was recognized as the standard of care by 1998.1,4 Since then, studies have shown that buprenorphine is also an effective treatment option.10 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Society of Addiction Medicine support methadone and buprenorphine treatment as best practice for opioid use disorder during pregnancy.1

Benefits of Treatment During Pregnancy. Treatment with methadone or buprenorphine improves infant outcomes by:

- stabilizing fetal levels of opioids, reducing repeated prenatal withdrawal2

- linking mothers to treatment for infectious diseases (e.

g., HIV, HBV, HCV), reducing likelihood of transmittal to the unborn baby1,3,4

g., HIV, HBV, HCV), reducing likelihood of transmittal to the unborn baby1,3,4 - providing opportunity for better prenatal care1,3

- improving long-term health outcomes for the mother and baby

Compared to untreated pregnant women, women treated with methadone or buprenorphine had infants with: 10,12

- lower risk of NAS

- less severe NAS

- shorter treatment time

- higher gestational age, weight, and head circumference at birth

Increasing Treatment Prescribing

NIDA-funded studies are evaluating key barriers and facilitators to prescribing methadone and buprenorphine for pregnant women. Current projects include:

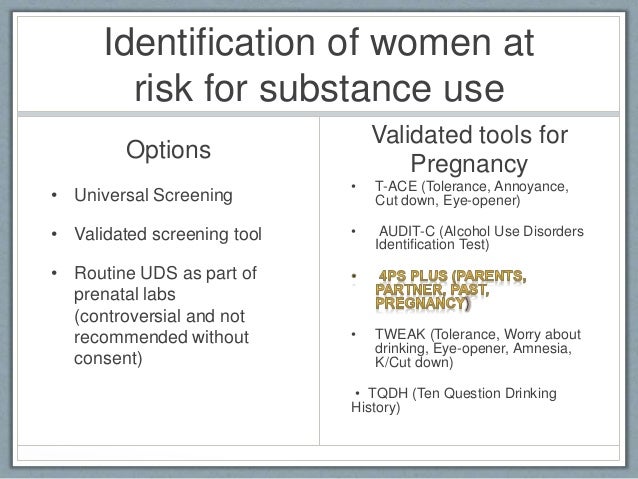

- validating reliable screening tools to identify pregnant women in need of treatment

- analyzing infant outcomes to inform medication selection for opioid use disorder during pregnancy

- evaluating behavioral interventions for opioid misuse in pregnancy

Improving Treatment Strategies

Treatment with methadone or buprenorphine does pose some risk for NAS. Divided dosing with methadone—taking smaller doses more often—reduces fetal exposure to withdrawal periods. Mothers treated with divided doses of methadone have babies with lower NAS severity.16 Currently, an NIH-funded study is examining buprenorphine during pregnancy and how to improve buprenorphine dosing regimens.

Divided dosing with methadone—taking smaller doses more often—reduces fetal exposure to withdrawal periods. Mothers treated with divided doses of methadone have babies with lower NAS severity.16 Currently, an NIH-funded study is examining buprenorphine during pregnancy and how to improve buprenorphine dosing regimens.

Improving Engagement in Treatment

- Stigma and bias among healthcare providers can result in both under-reporting of drug use and insufficient medication dosing, which often lead to delayed or ineffective treatments.14,15

- Eighteen states classify maternal drug use as child abuse, and three states consider it as reason for involuntary hospitalization, disincentivizing women from seeking treatment.5

- Women who are allowed to stay with their children during treatment are more likely to start treatment and maintain abstinence.14

Supporting access to treatment. Health insurance providers that cover treatment for substance use disorders are required to provide coverage equivalent to what is provided for other health conditions. Visit HHS' website to learn more about parity protections and insurance help for mental health or addiction services.

Visit HHS' website to learn more about parity protections and insurance help for mental health or addiction services.

Where Can I Get More Information?

If you or someone you care about is pregnant and has an opioid use disorder:

- Ask your healthcare provider about treatment options.

- To find treatment services in your area, visit SAMHSA's treatment locator and HRSA's Find a Health Center.

- Visit NIDA's webpages: NAS, heroin and pregnancy, and Effective Treatments for Opioid Addiction. Visit SAMHSA’s webpage: NAS.

References

- ACOG & ASAM. Obstet Gynecol (2012).

- Kaltenbach K, et al. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am (1998).

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. TIP Series 43 (2005).

- National Consensus Development Panel on Effective Medical Treatment of Opiate Addiction. JAMA (1998).

- Ko JY, et al. MMWR (2017).

- Patrick SW, et al. JAMA (2012).

- Patrick SW, et al. J Perinatol (2015).

- Epstein RA, et al. Ann Epidemiol (2013).

- Tolia VN, et al. NEJM (2015).

- Brogly SB, et al. Am J Epidemiol (2014).

- Jones HE, et al. NEJM (2010).

- Fajemirokun-Odudeyi O, et al. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol (2006).

- Klaman SL, et al. J Addic Med (2017).

- OWH. White Paper: Opioid Use, Misuse, and Overdose in Women (2016).

- Thigpen J & Melton ST. J Ped Pharm Ther (2014).

- McCarthy JJ, et al. J Addict Med (2015).

This publication is available for your use and may be reproduced in its entirety without permission from NIDA. Citation of the source is appreciated, using the following language: Source: National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Institutes of Health; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Pregnancy and drug use

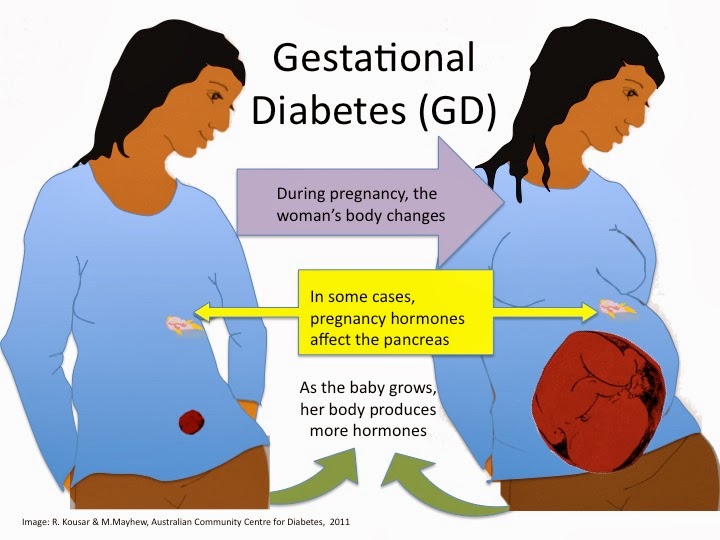

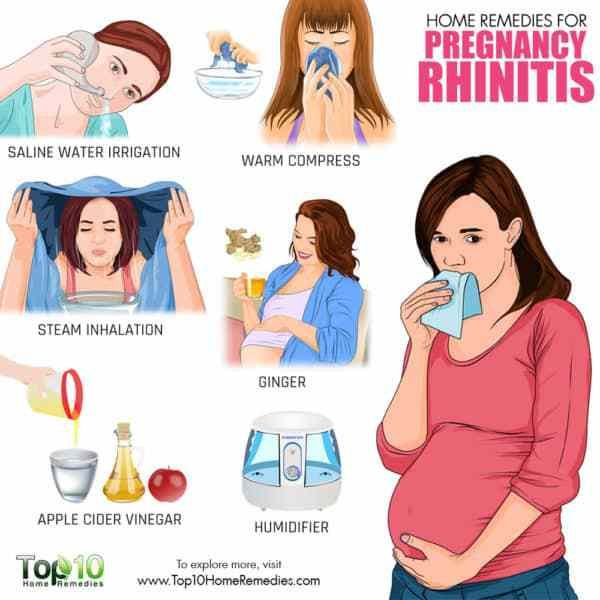

The use of opioid drugs affects the menstrual cycle in most women, causing a reduction or cessation of menstruation. This situation creates a careless attitude of drug addicted women to the need for contraception. However, the likelihood of pregnancy in this case is quite high and women who use drugs have a fairly high risk of unplanned pregnancy. In this case, the difficult life situation in which these women often find themselves is exacerbated by the need to create conditions for bearing and giving birth to a child. Often women are afraid to go to the doctor because of stigmatization, biased attitude of the staff of medical institutions accepting pregnant drug addicted women for treatment, fear of detention. Very often IDU women are in a difficult financial situation, so they have less opportunity to eat a balanced diet, take vitamins and keep a daily routine. Taking drugs every day, a woman can often forget about the time of taking the necessary medications and regular visits to the doctor, which often makes it difficult to notice and identify pregnancy complications in a timely manner. nine0004 The role of a social worker in this situation is to support the expectant mother psychologically, provide all the information about the possibility of organizing observation and treatment during pregnancy and childbirth, and facilitate the establishment of effective and comfortable communication between the client and the medical staff.

This situation creates a careless attitude of drug addicted women to the need for contraception. However, the likelihood of pregnancy in this case is quite high and women who use drugs have a fairly high risk of unplanned pregnancy. In this case, the difficult life situation in which these women often find themselves is exacerbated by the need to create conditions for bearing and giving birth to a child. Often women are afraid to go to the doctor because of stigmatization, biased attitude of the staff of medical institutions accepting pregnant drug addicted women for treatment, fear of detention. Very often IDU women are in a difficult financial situation, so they have less opportunity to eat a balanced diet, take vitamins and keep a daily routine. Taking drugs every day, a woman can often forget about the time of taking the necessary medications and regular visits to the doctor, which often makes it difficult to notice and identify pregnancy complications in a timely manner. nine0004 The role of a social worker in this situation is to support the expectant mother psychologically, provide all the information about the possibility of organizing observation and treatment during pregnancy and childbirth, and facilitate the establishment of effective and comfortable communication between the client and the medical staff.

Although the effect of drugs on a woman's body has not been studied enough, all researchers agree that drug use during pregnancy can cause multiple pathologies and delay the development of the child. nine0005

As a rule, women addicted to drugs use alcohol and tobacco in parallel, which causes significant harm to the body of a pregnant woman and a child. Pregnancy always takes place against the background of a change in immunity, and if additional effects of toxic substances are added to this, this leads to an exacerbation of chronic processes in the body, the appearance of anemia, the addition of infections, incl. viral, placental lesions, threatened miscarriage, intrauterine growth retardation, malformations of its internal organs. nine0005

However! Abrupt discontinuation of opioid drugs may result in miscarriage or premature birth. The best option in this situation is the transition to substitution maintenance therapy (RRT).

RRT is the global standard of care for opioid dependence in pregnant women. Methadone is generally considered the drug of choice for the treatment of pregnant women based on years of experience with its use. There is no need to fear that methadone will adversely affect the health of the child. There is no evidence that stable doses are associated with additional risks to fetal development. However, the use of methadone also has a number of studied negative aspects. A child can be born in a state of the so-called neonatal withdrawal syndrome. It is characterized by increased excitability of the central nervous system, disorders of the gastrointestinal tract, cardiovascular and respiratory systems of newborns. The most common manifestations are: tremor, sleep disturbance, irritable and shrill cry, increased muscle tone, convulsions, decreased appetite, compulsive sucking, vomiting, diarrhea, poor weight gain, sweating, fever, palpitations, nasal congestion. If the mother believes that the child has withdrawal symptoms, it is necessary to tell the doctor about it.

Methadone is generally considered the drug of choice for the treatment of pregnant women based on years of experience with its use. There is no need to fear that methadone will adversely affect the health of the child. There is no evidence that stable doses are associated with additional risks to fetal development. However, the use of methadone also has a number of studied negative aspects. A child can be born in a state of the so-called neonatal withdrawal syndrome. It is characterized by increased excitability of the central nervous system, disorders of the gastrointestinal tract, cardiovascular and respiratory systems of newborns. The most common manifestations are: tremor, sleep disturbance, irritable and shrill cry, increased muscle tone, convulsions, decreased appetite, compulsive sucking, vomiting, diarrhea, poor weight gain, sweating, fever, palpitations, nasal congestion. If the mother believes that the child has withdrawal symptoms, it is necessary to tell the doctor about it. Withdrawal symptoms can be relieved under medical supervision in a few days without any long-term effects. Between feedings, you need to give the child as much rest as possible and not take him out into bright light. Under no circumstances should you try to relieve your child of withdrawal symptoms or give him methadone - this can be dangerous for his life! nine0005

Withdrawal symptoms can be relieved under medical supervision in a few days without any long-term effects. Between feedings, you need to give the child as much rest as possible and not take him out into bright light. Under no circumstances should you try to relieve your child of withdrawal symptoms or give him methadone - this can be dangerous for his life! nine0005

If a woman taking methadone wants to breastfeed and has no specific contraindications, such as some infectious diseases and illicit drug use, her doctor should support her decision. Breastfeeding is good for babies and mothers, and breastfeeding is not contraindicated while taking methadone. Small amounts of methadone can be found in milk, but there is no clear estimate of how long after the start of treatment it gets there. Small amounts of methadone in milk may prevent or reduce withdrawal symptoms in a newborn. It is possible that similar recommendations could be made for breastfeeding while on buprenorphine, but here they are based on a shorter follow-up period and fewer cases studied. nine0005

nine0005

Women who use , stimulants should, if possible, stop taking drugs under the supervision of a doctor or, in extreme cases, refuse to inject them (for example, switch to oral use).

It is necessary to explain to drug addicted pregnant women that the doctor and obstetrician need to know about the methadone treatment she is undergoing, as well as about all other drugs that she has taken or is taking. This is important for the correct selection of methods and drugs for anesthesia. nine0005

Recommendations during social worker consultation pregnant injecting drug user :

- Make sure you are pregnant (take a pregnancy test).

- Visit a gynecologist (contact a community organization for support/accompaniment).

- Do not stop taking drugs abruptly! Do this under medical supervision.

- If using opiates, become a client of a substitution therapy program.

- If this is not an option for you, try switching to less toxic drugs and safer ways of using (smoking, snorting, swallowing).

- If you are already an RRT client, don't interrupt your treatment!

- Just before you give birth, make sure your doctor and midwife know about your methadone treatment and any other drugs you have taken or are taking. nine0042

- Give up tobacco and alcohol.

- Get all the tests your doctor orders.

- Regularly see a doctor, attend a school of responsible motherhood, do not neglect the advice of a psychologist, try to be as honest as possible at the appointment, do not hesitate to ask questions and talk about complaints.

It is important for a social worker to know that counseling is a mandatory component of assistance to HIV-infected women with drug addiction (according to the order of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine dated May 16, 2016 No. 449). It should include a discussion of the following questions:

- drug harm to the fetus and newborn;

- maternal and fetal benefits of RRT;

- risk of stress in the fetus due to drug withdrawal attempts in the absence of medical and psychological assistance;

- the effect of pregnancy on the dosage of the drug in substitution therapy and the possible need to increase it;

- interactions between RRT drugs and ARV drugs; nine0042

- adherence to substitution therapy and ART.

Lessons in this course:

Supportive care for pregnant women with opiate dependence

Review question

This review pools studies comparing different types of pharmacological maintenance treatment in pregnant women with opiate dependence

Key Information

Methadone and buprenorphine may be very similar in efficacy and safety for the treatment of opioid-dependent pregnant women and their infants. There is insufficient evidence to draw conclusions for a comparison between methadone and slow release morphine. Overall, the body of evidence is too small to draw firm conclusions.

Relevance

Some women continue to use opiates during pregnancy, but heroin crosses the placenta easily. Women who are addicted to opiates have a sixfold increase in obstetric complications and may have low birth weight babies. A newborn baby may experience drug withdrawal syndrome (neonatal withdrawal syndrome) and developmental problems. Neonatal mortality is also increasing and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome is 74 times higher. Methadone maintenance therapy provides a constant concentration of opiates in the blood of a pregnant woman and thus prevents the adverse effects on the fetus of repeated withdrawal syndromes. Buprenorphine is also used. nine0005

A newborn baby may experience drug withdrawal syndrome (neonatal withdrawal syndrome) and developmental problems. Neonatal mortality is also increasing and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome is 74 times higher. Methadone maintenance therapy provides a constant concentration of opiates in the blood of a pregnant woman and thus prevents the adverse effects on the fetus of repeated withdrawal syndromes. Buprenorphine is also used. nine0005

Search date

The evidence is current to 18 February 2020.

Study profile

Only four randomized controlled trials with 271 participants met the inclusion criteria for the review: two from Austria (outpatient), one from the US (inpatient) and the fourth multicenter international study conducted in Austria, Canada and the US. The trials lasted from 15 to 18 weeks. Three trials compared methadone with buprenorphine (223 participants), and one compared methadone with slow-release oral morphine (48 participants). nine0005

nine0005

Research funding sources

The National Institute for Drug Abuse has funded two studies, one of which received a grant from the Mayor of Vienna, and for the fourth study Schering-Plug provided the first author with a training grant to recruit the staff needed to conduct this study.

Main results nine0005

This review found little difference in neonatal or maternal outcomes when opiate-dependent pregnant women received methadone, buprenorphine, or slow-release oral morphine from a mean gestational age of 23 weeks until delivery.

Comparing methadone with buprenorphine, it can be assumed that there is little or no difference in the number of women who stop treatment. Differences in primary substance use and in the number of newborns treated for neonatal withdrawal syndrome between the methadone and buprenorphine groups may be small or non-existent. We are very uncertain whether newborn babies born to mothers receiving buprenorphine may have higher birth weights. nine0005

nine0005

Comparison of methadone with slow-release oral morphine - there were no dropouts in the only included study. Heroin use in the third trimester may be lower with slow-release morphine. However, differences in birth weight or duration of neonatal abstinence syndrome may be small or non-existent.

The number of participants in the trials was small and may not be sufficient to draw firm conclusions. All included studies ended immediately after the baby was born. No serious complications were noted. nine0005

Quality of evidence

When comparing methadone with buprenorphine, the quality of the evidence varied from moderate to very low due to inconsistent study results for some outcomes, a large proportion of participants dropping out of studies, and a small sample size of included studies. When comparing methadone with slow-release morphine, the quality of the evidence was low due to the small sample size of the study.