Meta communication meaning

What Is Metacommunication in Interpersonal Relations?

Communication about communication is known as metacommunication — a powerful indicator of someone’s thoughts and intentions.

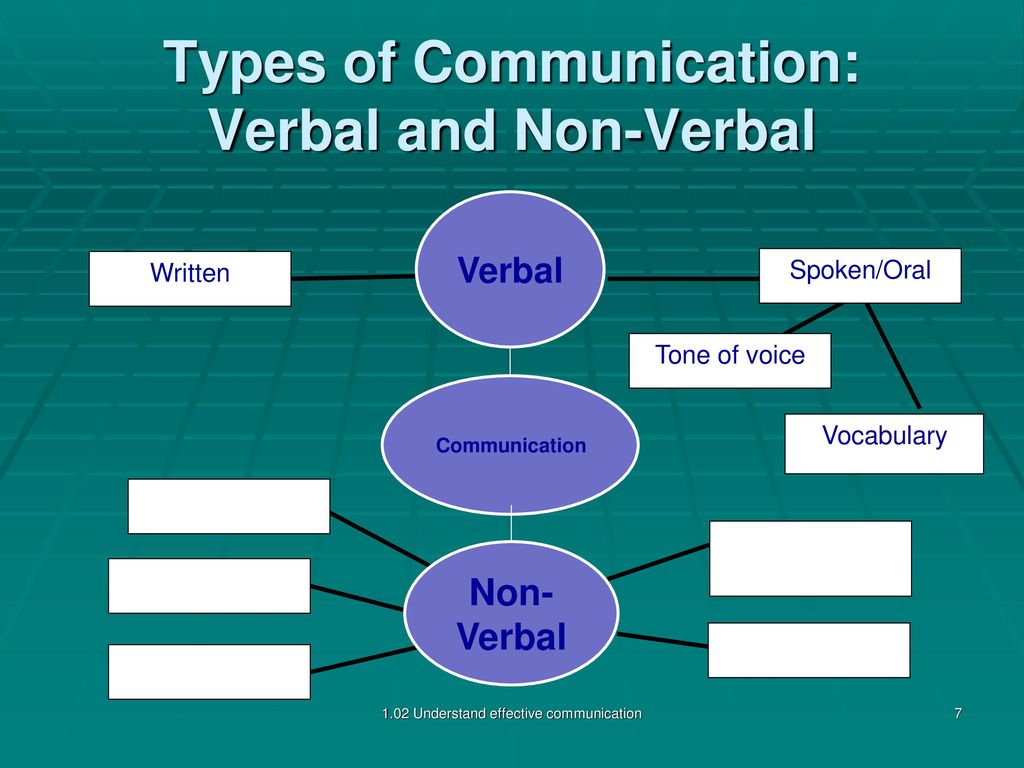

Being able to communicate effectively offers advantages, whether it’s in a relationship or during a casual interaction. Communication can convey your intent and needs and guide others in how they interact with you.

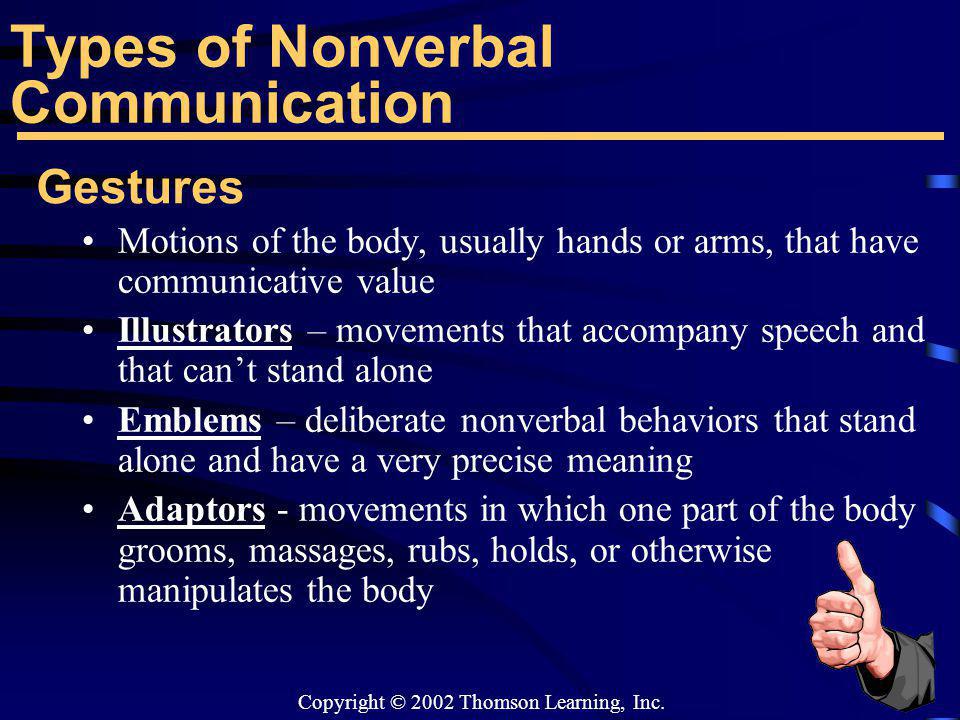

Communication is not just verbal, however. The tone of your voice, stance, facial expressions, and other gestures you make may also send a message.

This subtle relay of information about what you’re saying is known as metacommunication.

Metacommunication is a secondary expression of intent that either supports or conflicts with what you’re saying verbally. In other words, it’s the non-verbal message you send when interacting with someone.

“I work with my clients to understand metacommunication as the character of our communication; our cues and messages we broadcast independently of whatever we are saying,” says Dr. Crystal Shelton, a licensed clinical social worker from Silver Spring, Maryland.

This process of covert messaging or metacommunication may involve:

- body language

- facial expression

- tonality

- vocalizations (sighing, laughing)

- touch

- eye contact

- personal space

- appearance

- objects

- media elements (profile picture, posts, or chosen quotes)

Often, metacommunication is missed unless it conveys the opposite of what someone says, but research suggests metacommunication is always happening.

Metacommunication beyond human interaction

You can see metacommunication in real time by interacting with an unfamiliar animal.

For example, you’re at the dog park, and a dog approaches you. The dog may not be able to understand your words, but the eye contact you make, the posture you hold, and your tonality can indicate to that dog if you’re a friend or foe.

Similarly, you know through the dog’s behaviors if it’s affectionate or guarded. No words are needed.

No words are needed.

Being able to “read between the lines” can be an important tool in a therapeutic setting. Not only may it help a mental health professional gain insight into underlying challenges, but it may also help facilitate a relationship between you and your therapist.

“Metacommunication can be used to mask or conceal the real feeling of the person when a person is unable to express their true feelings,” explains Jacqueline Connors, a licensed marriage and family therapist from Napa, California. “Unmasking the underlying expression helps the therapeutic process by getting to the root of the issue.”

For a therapist, guaranteeing personal metacommunication aligns with expressions of empathy can help establish a bond of trust and confidence.

“A skilled therapist works to communicate a client’s value, build their agency, and establish empathy through many cues beyond verbal exchange,” Shelton adds.

Sarcasm and irony in metacommunication

According to Shelton, metacommunication often implies nonverbal processes but can also include

how language is used.

Sarcasm and irony are two forms of linguistics that use metacommunication to relay meanings beyond those of the exact words being said.

“If I am trying to tell you that I am happy to be at a party you have thrown, but I am constantly checking my watch, yawning, and looking at the door, my direct communication might be that I am happy, but my metacommunication is suggesting something different,” explains Shelton.

Other examples of metacommunication are:

- What’s said: “I am fine. Everything is OK.”

- What’s metacommunicated: A sigh, accompanied by face rubbing and a slight frown, might suggest it wasn’t as good of a day as said.

- What’s said: “I’m so excited to meet you!”

- What’s metacommunicated: Arriving late to the meeting, appearing unkempt, and looking around distractedly might indicate a lack of interest.

- What’s said: “I would never do that.

”

” - What’s metacommunicated: Fidgeting movements and avoidant eye contact can convey the presence of guilt or uneasiness.

- What’s said: “I am so glad you were able to come!”

- What’s metacommunicated: A warm embrace, eye contact, and welcoming smile support the verbal assertion of enthusiasm.

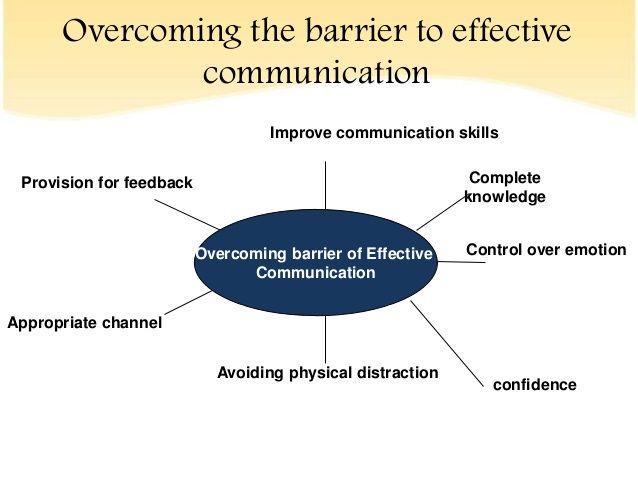

Metacommunication, though often subconscious, can take focused, conscious effort to develop. Doing so can help ensure you send the message you intend when interacting with others.

“Intentionality, intentionality, intentionality,” Shelton says of starting the process. “Be aware of what you intend to communicate and craft your behavioral and emotional behaviors around that.”

These tips can help you match verbal messages and metacommunication:

Studying others

One way to help build your metacommunication is by observing it in others.

For example, what else happens when someone’s metacommunication matches their verbal communication? What happens when you feel as though verbal and meta aren’t aligned?

Reinforcing your direct communication skills

Not all metacommunication with conflicting messages is with the intent to deceive. Sometimes, you might not know how to express yourself appropriately with words or may be trying to be polite or private.

Sometimes, you might not know how to express yourself appropriately with words or may be trying to be polite or private.

By building your assertive communication skills, you may be able to prevent unintentional mis-metacommunication.

Practicing

The saying “practice makes perfect” applies to communication skills as much as any other skill set.

“Focus on your state as you are communicating your words,” suggests Connors. “The state you’re in will help you control your body language and the tonality of your delivery. Practice expressing yourself in a very literal way that clearly defines what you are wanting to say.”

Metacommunicative signals are the mannerisms, behaviors, and cues accompanying your verbal form of communication.

But, while these signals can be nonverbal, sometimes words themselves can also deliberately hide intention, such as with irony or sarcasm.

Honing your metacommunication skills can help ensure your communication is effective and conveys only the information you want.

What Is Metacommunication in Interpersonal Relations?

Communication about communication is known as metacommunication — a powerful indicator of someone’s thoughts and intentions.

Being able to communicate effectively offers advantages, whether it’s in a relationship or during a casual interaction. Communication can convey your intent and needs and guide others in how they interact with you.

Communication is not just verbal, however. The tone of your voice, stance, facial expressions, and other gestures you make may also send a message.

This subtle relay of information about what you’re saying is known as metacommunication.

Metacommunication is a secondary expression of intent that either supports or conflicts with what you’re saying verbally. In other words, it’s the non-verbal message you send when interacting with someone.

“I work with my clients to understand metacommunication as the character of our communication; our cues and messages we broadcast independently of whatever we are saying,” says Dr. Crystal Shelton, a licensed clinical social worker from Silver Spring, Maryland.

Crystal Shelton, a licensed clinical social worker from Silver Spring, Maryland.

This process of covert messaging or metacommunication may involve:

- body language

- facial expression

- tonality

- vocalizations (sighing, laughing)

- touch

- eye contact

- personal space

- appearance

- objects

- media elements (profile picture, posts, or chosen quotes)

Often, metacommunication is missed unless it conveys the opposite of what someone says, but research suggests metacommunication is always happening.

Metacommunication beyond human interaction

You can see metacommunication in real time by interacting with an unfamiliar animal.

For example, you’re at the dog park, and a dog approaches you. The dog may not be able to understand your words, but the eye contact you make, the posture you hold, and your tonality can indicate to that dog if you’re a friend or foe.

Similarly, you know through the dog’s behaviors if it’s affectionate or guarded. No words are needed.

No words are needed.

Being able to “read between the lines” can be an important tool in a therapeutic setting. Not only may it help a mental health professional gain insight into underlying challenges, but it may also help facilitate a relationship between you and your therapist.

“Metacommunication can be used to mask or conceal the real feeling of the person when a person is unable to express their true feelings,” explains Jacqueline Connors, a licensed marriage and family therapist from Napa, California. “Unmasking the underlying expression helps the therapeutic process by getting to the root of the issue.”

For a therapist, guaranteeing personal metacommunication aligns with expressions of empathy can help establish a bond of trust and confidence.

“A skilled therapist works to communicate a client’s value, build their agency, and establish empathy through many cues beyond verbal exchange,” Shelton adds.

Sarcasm and irony in metacommunication

According to Shelton, metacommunication often implies nonverbal processes but can also include how language is used.

Sarcasm and irony are two forms of linguistics that use metacommunication to relay meanings beyond those of the exact words being said.

“If I am trying to tell you that I am happy to be at a party you have thrown, but I am constantly checking my watch, yawning, and looking at the door, my direct communication might be that I am happy, but my metacommunication is suggesting something different,” explains Shelton.

Other examples of metacommunication are:

- What’s said: “I am fine. Everything is OK.”

- What’s metacommunicated: A sigh, accompanied by face rubbing and a slight frown, might suggest it wasn’t as good of a day as said.

- What’s said: “I’m so excited to meet you!”

- What’s metacommunicated: Arriving late to the meeting, appearing unkempt, and looking around distractedly might indicate a lack of interest.

- What’s said: “I would never do that.

”

” - What’s metacommunicated: Fidgeting movements and avoidant eye contact can convey the presence of guilt or uneasiness.

- What’s said: “I am so glad you were able to come!”

- What’s metacommunicated: A warm embrace, eye contact, and welcoming smile support the verbal assertion of enthusiasm.

Metacommunication, though often subconscious, can take focused, conscious effort to develop. Doing so can help ensure you send the message you intend when interacting with others.

“Intentionality, intentionality, intentionality,” Shelton says of starting the process. “Be aware of what you intend to communicate and craft your behavioral and emotional behaviors around that.”

These tips can help you match verbal messages and metacommunication:

Studying others

One way to help build your metacommunication is by observing it in others.

For example, what else happens when someone’s metacommunication matches their verbal communication? What happens when you feel as though verbal and meta aren’t aligned?

Reinforcing your direct communication skills

Not all metacommunication with conflicting messages is with the intent to deceive. Sometimes, you might not know how to express yourself appropriately with words or may be trying to be polite or private.

Sometimes, you might not know how to express yourself appropriately with words or may be trying to be polite or private.

By building your assertive communication skills, you may be able to prevent unintentional mis-metacommunication.

Practicing

The saying “practice makes perfect” applies to communication skills as much as any other skill set.

“Focus on your state as you are communicating your words,” suggests Connors. “The state you’re in will help you control your body language and the tonality of your delivery. Practice expressing yourself in a very literal way that clearly defines what you are wanting to say.”

Metacommunicative signals are the mannerisms, behaviors, and cues accompanying your verbal form of communication.

But, while these signals can be nonverbal, sometimes words themselves can also deliberately hide intention, such as with irony or sarcasm.

Honing your metacommunication skills can help ensure your communication is effective and conveys only the information you want.

Metacommunication - Semiotics

Whoever does not share what he has found is like a light in the hollow of a sequoia (ancient Indian proverb)

Bibliographic record: Metacommunication. - Text: electronic // Myfilology.ru - informational philological resource: [website]. – URL: https://myfilology.ru//semiotika/metakommunikacziya/ (date of access: 27.02.2023)

Contents

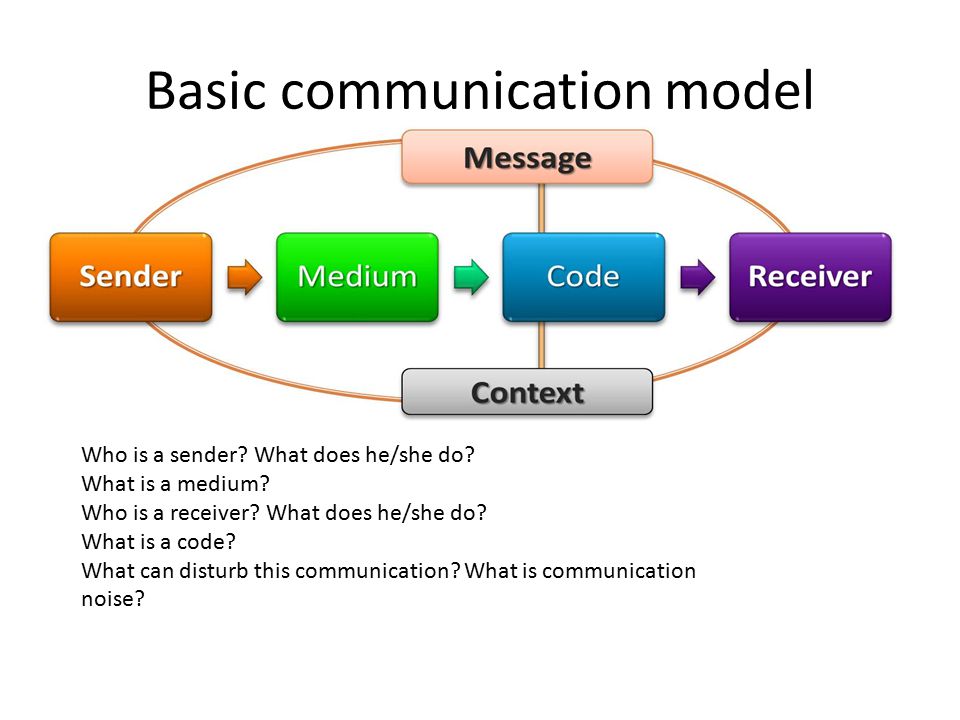

Metacommunication is a special kind of communication, the subject of which is the process of communication itself. In other words, metacommunication is communication about communication. Most often, the functions of metacommunication are commenting, explaining, stating or evaluating communicative messages - both one's own and others'. Below, metacommunication will be understood as any message aimed at commenting, explaining, stating or evaluating a person's own communicative actions. At the same time, almost any activity that manifests itself in the context of significant contacts with other people falls into the category of communicative actions.

At the same time, almost any activity that manifests itself in the context of significant contacts with other people falls into the category of communicative actions.

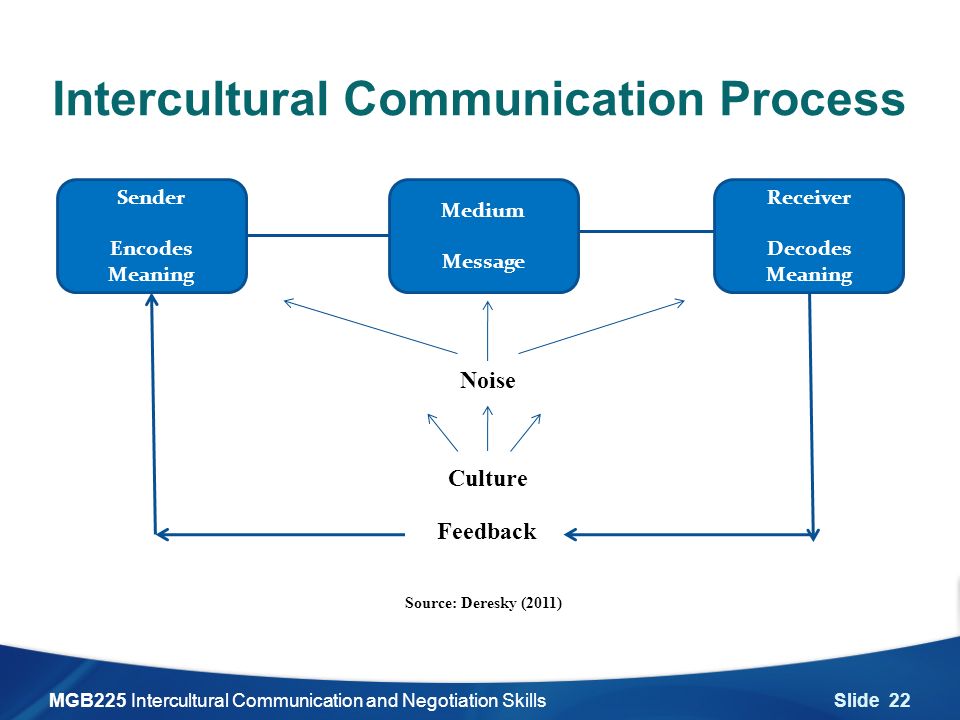

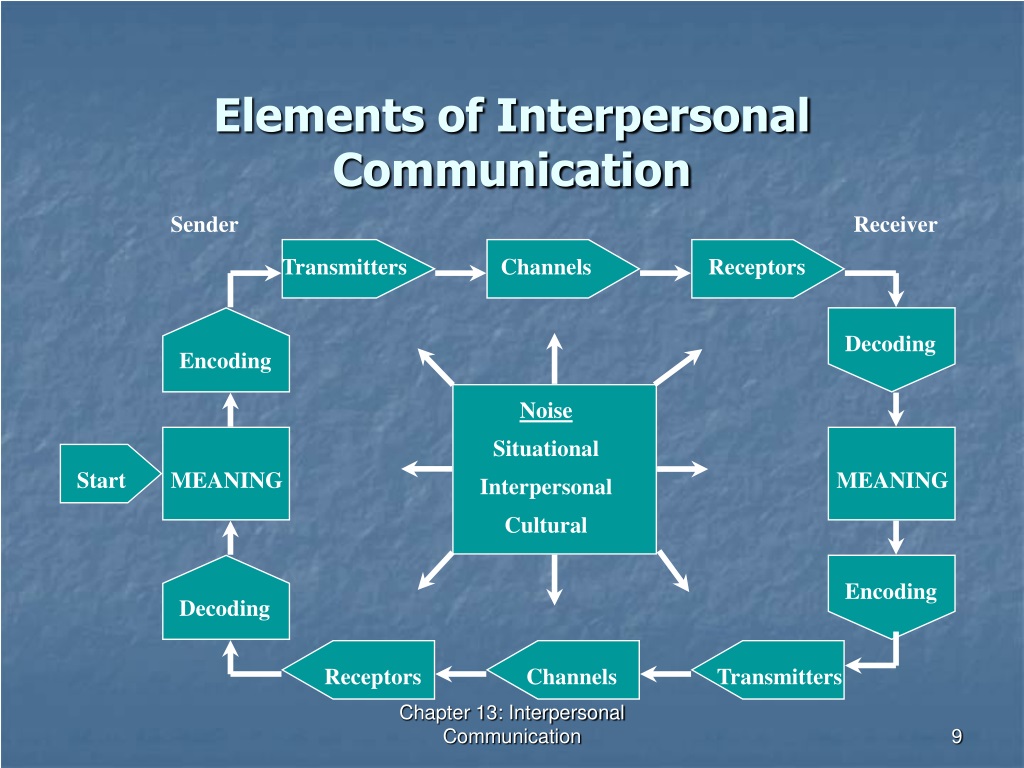

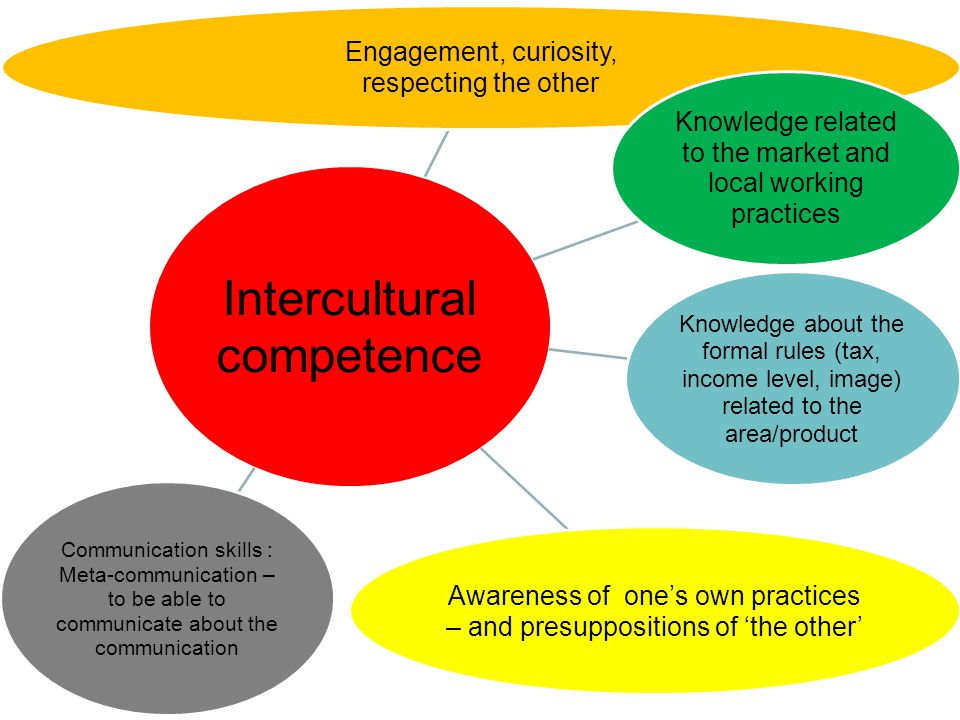

It has already become customary, based on the means used in communicative activity, to talk about verbal and non-verbal communication. The first includes exclusively linguistic means, and the second includes a huge range of bodily, mimic, intonational, tactile and other means. And since metacommunication is a kind of communicative activity in general, it can also use both verbal and non-verbal means. This conditional division of communication and metacommunication into verbal and nonverbal messages leads to the formation of four types of metacommunicative messages (metamessages).

1. Type “VV”: a verbal metamessage about a verbal message.

2. Type “VN”: a verbal metamessage about a nonverbal message.

3. Type “NV”: non-verbal metamessage about a verbal message.

4. Type "NN": non-verbal metamessage about a non-verbal message.

The first two types of messages are well known, since this is exactly what is usually meant by metacommunication - a verbal commentary on the process of communication. Our task is to draw attention to the fact that this comment may be non-verbal, but perform the same metacommunicative functions (stating, evaluation, explanation, etc.).

One of the typical examples of non-verbal metamessage about one's own verbal message (NV-metamessage) is “quotes”, which in live speech are formed by a specific intonation. I speak and at the same time present some words in a certain way, namely, intonationally singling them into quotation marks and thereby, as it were, saying: “These words are not mine” or “I am speaking in a figurative sense.” (Not so long ago, a specific two-handed gesture appeared, indicating: “I say this in quotation marks.”)

Another situation: a person talks about serious things with a smile on his face. One of the common interpretations of this “incongruent situation” is that, they say, a person verbally “deceives”, and “non-verbal gives him away”. Perhaps this simplified interpretation has the right to exist. Nevertheless, I propose to explain the phenomenon of “incongruence” from the point of view of non-verbal metacommunication. In addition to the verbal message (let's take the case when it is true), a person simultaneously comments on it bodily (NV-metamessage). In this case, the bodily gesture (“inappropriate smile”) can be represented as a verbal equivalent: “Really, I look funny when I talk about serious things?”.

Perhaps this simplified interpretation has the right to exist. Nevertheless, I propose to explain the phenomenon of “incongruence” from the point of view of non-verbal metacommunication. In addition to the verbal message (let's take the case when it is true), a person simultaneously comments on it bodily (NV-metamessage). In this case, the bodily gesture (“inappropriate smile”) can be represented as a verbal equivalent: “Really, I look funny when I talk about serious things?”.

Another example of metacommunication (this time a VV metamessage) from V. Nabokov's story "Spring in Fialta": -funny) a long lollipop of moonlight ... ”(Nabokov V.V. Stories. Memoirs. M .: Sovremennik, 1991. P. 295).

Since metamessages make sense only in connection with the messages about which they were made, we usually deal with whole “communicative-metacommunicative complexes”. Therefore, in real communication, we most often encounter not just speech, but speech with a certain presentation of this speech (VV-, NV-metamessages), not just an action, but an action with a certain presentation of this action (VN-, NN-metamessages).

Here are examples of “complex messages” that include verbal comments on bodily actions: 1) a person enters a room with a jug of water and says: “I will water the flowers”; 2) a person gets up to leave, and accompanies this with the words: “Something I stayed too long.” In these "complex messages" there is just a communicative component and a comment component (VN-metamessage). The presence (and necessity) of the latter is proved by the fact that, theoretically, these same actions could be performed without comments (that is, silently), but something makes people comment on their actions.

Here we come close to explaining the meaning of the phenomenon of metacommunication. The source of metacommunication is the ability to see (hear) one's actions (one's own words) on the part of the interlocutor, to perceive them in the way that he possibly perceives them. In other words, metacommunication has a deep reflective and empathic basis. Metacommunication (more than any other communication) is always oriented towards the interlocutor. Only the interlocutor here is rather not explicit, but imaginary, and what is imagined here is not so much the interlocutor as his thoughts and feelings. It is this projective-empathic prediction that calls metacommentary to life. (In this case, it does not matter if these imaginary thoughts and feelings correspond to reality or not, the main thing is that they are assumed and therefore require a response.)

Only the interlocutor here is rather not explicit, but imaginary, and what is imagined here is not so much the interlocutor as his thoughts and feelings. It is this projective-empathic prediction that calls metacommentary to life. (In this case, it does not matter if these imaginary thoughts and feelings correspond to reality or not, the main thing is that they are assumed and therefore require a response.)

Thus, metacommunication can be defined as answers to the supposed questions of the interlocutor: why are you talking about this? why did you come? What are you doing? and many others. Metacommunication is a consequence of the social skills of predicting other people's opinions and evaluating it, it is a consequence of caring for the preservation of the image of oneself in the minds of significant people, the need to understand oneself and one's behavior by other people.

the art of talking about how to talk - Reverse engineering managerial unconsciousness

My Telegram channel lives here.

Man is a social being. It is important for us to feel like full-fledged participants in society, which is why we learn to speak so early. And we do everything that depends on us to convey our thoughts and intentions as best as possible. After all, the success of our social life directly depends on this. But rather quickly we are faced with a situation where what is more important is not what we say, but how we do it.

Communication in its structure resembles a layer cake. Each message contains several levels, conveying the content, our attitude towards it, as well as our attitude towards the addressee. All levels interact very tightly. The content depends on the relationship, and the relationship cannot be conveyed without a specific plan of content.

We learn to communicate throughout our conscious life, so in most cases everything goes well. But sometimes failures happen. As practice shows, communication problems quite often lie in the plane of relationships. This results in the content getting through, but the overall effect that the message has on the recipient leaves much to be desired.

This results in the content getting through, but the overall effect that the message has on the recipient leaves much to be desired.

I will illustrate. Two examples of a manager's message:

Option 1: "It's important to check the report carefully before sending it, otherwise we will have to pay a fine."

Option 2: "Just make a mistake in the report and we won't all be laughing."

The content is the same, but the relationship is different. In the second case, it is likely that the addressee will think about what the leader really wanted to say. Or not, if in this team such a style of communication is perceived as the norm.

Or, for example, sarcasm. Have you ever had to check with your interlocutor whether sarcasm flashed through his statement? I think more than once. The moment you did it, you turned to art metacommunications .

The key to successful communication is the ability of its participants to become observers and evaluate it from the outside. What we say and how, as well as how we feel about it. This is the essence of the mysterious prefix “meta”.

What we say and how, as well as how we feel about it. This is the essence of the mysterious prefix “meta”.

“Meta” means “about oneself”. Metadata is data about data. A metalanguage is the means of a language that allows one to discuss the language itself. Metacommunication (MC) is communication about the communication itself: about its quality, character, success or failure. MC helps to switch attention from the content to how we communicate, how we feel now and in general, how we relate to the addressee and the subject of the conversation. It helps to “open the cards” and give feedback. And also find out the following along the way:0007

- how effectively we convey our message,

- whether everything is clear to our interlocutor,

- whether there is a misunderstanding,

- and what are its causes (problems with content or in relationships).

Metacommunication can proceed in both positive and negative ways.

Positive metacommunication

Positive MC is of great importance in tense moments that arise between people. It helps set boundaries and set a “limit” on the damage that can be done. Whether it's a quarrel between colleagues or a couple in love. A positive MC will keep you from falling into the twilight zone where “getting personal and standing up for yourself” reigns, will reduce tension and anxiety by reminding the parties that they care about each other and are equally interested in solving the problem.

It helps set boundaries and set a “limit” on the damage that can be done. Whether it's a quarrel between colleagues or a couple in love. A positive MC will keep you from falling into the twilight zone where “getting personal and standing up for yourself” reigns, will reduce tension and anxiety by reminding the parties that they care about each other and are equally interested in solving the problem.

Examples of positive MC:

“We're having a very lively argument right now, but I want you to know I'm just trying to figure things out.”

“I think we are both on edge and take each other's statements too literally. I think we'd better discuss this when the emotions cool down.”

“We got off topic. Let's get back to the subject."

“I'm worried about you and appreciate your willingness to work with me to find out what happened.”

“I don't seem to get the gist of what you're saying.” or “You misunderstood me. I did not mean it."

Negative metacommunication

Negative MC in tense moments acts like an atomic explosion: it causes an escalation of the dispute and brings it to a level where the content is almost irrelevant, because the interlocutors are “stunned” by an explosion of emotions.

Examples of negative MC:

“I hope you understand that although we are discussing this all now, I will do as I see fit.”

“Did you notice that you act illogical every time we argue?”

“You don't care what the outcome of our argument is.”

“I see no point in discussing this. We still can't find a solution to this problem. Let everyone stay on their own.”

In a storm of emotions it is very difficult to resist such remarks. But if their effect is known to us in advance and we remember that in 100% of cases this will worsen the situation, perhaps we will resort to them less often.

In the era of instant messengers, when we don't see gestures and don't hear intonations, metacommunication is a great way out. It's important to remember that we tend to paint the picture if we don't get all the details. We think out meanings, read between the lines what is not really there, assign intonations if we do not hear them, and complete the motives.