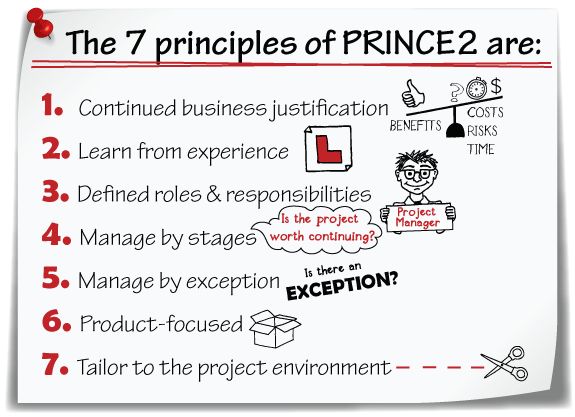

7 principles of aba

7 Dimensions of Applied Behavior Analysis | by Carlyle Center

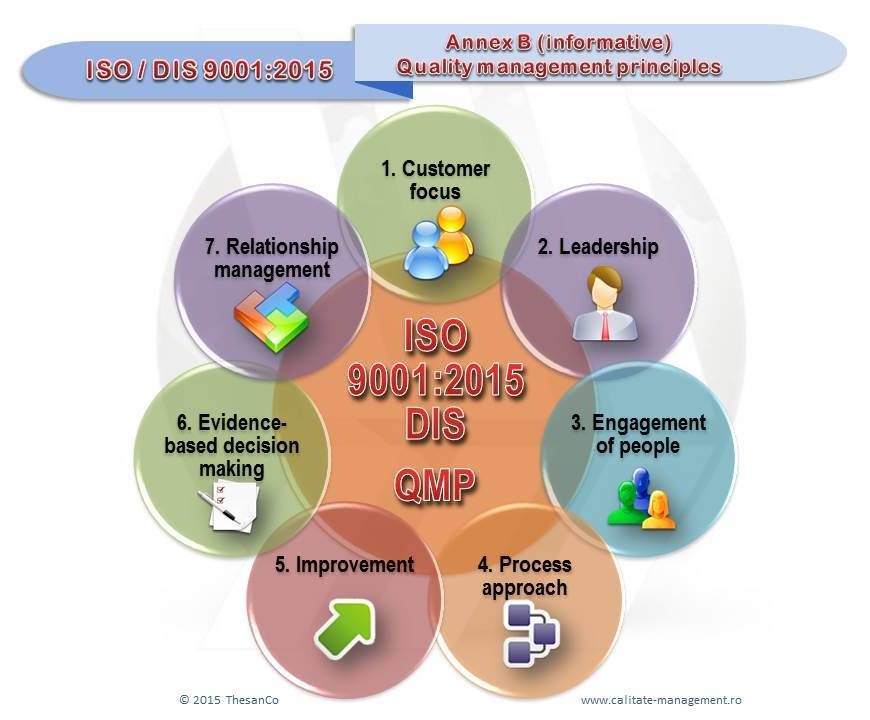

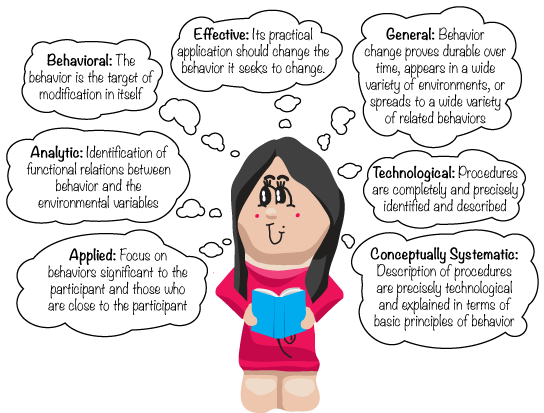

This week we are taking a deeper look into the field of Applied Behavior Analysis, otherwise referred to as “ABA.’ ABA) is based on evidenced-based scientific methods using the 7 dimensions (Baer, Wolf, Risley, 1968) that all practitioners should follow. It is important that an individual’s treatment plan has goals following these 7 dimensions: 1) Generality, 2) Effective, 3) Technological, 4) Applied, 5) Conceptually Systematic, 6) Analytic, 7) Behavioral. The ultimate goal of a Behavior Analyst is to bring about meaningful change to their children and families and for that change to occur in situations other than where it was explicitly taught, (i.e., community, school, with family members, etc.). That meaningful change can happen when Behavior Analysts are using the 7 dimensions of ABA #getacab.

Below we are going to focus on each one of the aforementioned seven dimensions in further detail with the goal of helping grow your understanding in each.

Generality

When a behavior is targeted for change, that change should not just be programmed to occur in the moment, or for a short time thereafter. The behavior change, meaning the skills gained within treatment, should stand the test of time. Moreover, it should maintain across different people and environments well after treatment has ended.

Often times ABA is conducted in a sterile environment, or more clinical type setting. Although programming is initially occurring in this setting, the treatment should be designed in such a way that reflects the individual’s natural environment. By doing so, we help ensure the behavior generalizes across different environments outside of treatment, and that it will maintain across time. It is best practice to have consistent staff during your child’s treatment, but the child should have access to practice learned skills with other children and staff. A treatment is not considered effective or successful until generality is achieved.

Effective

Goals should reflect and be relevant to the client and the culture of their community, but just as important- the interventions being used must be effective. Important questions to ask are: “Is the intervention working? “Am I seeing the data going in the desired direction?” These questions can be answered by frequent progress monitoring of data collection and observing the interventions being utilized.

Technological

An intervention should be written in a way where it describes all of the components clearly and detailed enough for anyone else to replicate it. To make this possible, all of the techniques that comprise an intervention should be fully identified and described. As an example, think about your favorite Pinterest recipe for baking a cake- it’s well written, easy to understand and executable. So much so that even my husband can do it!. Applying behavioral analytic interventions to individuals is clearly more complex, however, it should follow the same rules. Let’s pretend the intervention outlined is difficult to understand or not clearly written; the chances that everyone on the treatment team are implementing treatment in the same way is low. When a behavior intervention is technological, intervention is easy to replicate and treatment integrity is high.

Let’s pretend the intervention outlined is difficult to understand or not clearly written; the chances that everyone on the treatment team are implementing treatment in the same way is low. When a behavior intervention is technological, intervention is easy to replicate and treatment integrity is high.

Applied

The term applied refers to implementing ABA interventions in society, after it’s gone through research in a laboratory. Behavior Analyst’s must focus on these implementation principles of ABA to change socially significant behaviors. The particular treatment goals decided upon as a prioritizing focus is based on its importance to the individual, and individuals family. Each individual’s socially significant behaviors are individual to them, and are the skills that will allow this individual to more easily, and successfully, function within their environment. For intervention to be socially valid, it must produce a significant meaningful change that maintains over time.

For example, if a child is engaging in tantrum behaviors because they are not able to effectively communicate their wants and needs, what would be a meaningful behavior to target? Teaching the child how to effectively communicate their wants and needs would be a socially valid goal. It would immediately affect the client’s everyday life, as well as the lives of those who interact with the child on a daily basis (family members, teachers, friends). When considering treatment interventions, the team must always consider how immediately important the targeted behavior change will be to the client.

Conceptually systematic

To say that an intervention is conceptually systematic, says that the intervention is research- based and represents principles of applied behavior analysis. An important question to ask: “Is this intervention consistent with principals that have determined to be effective as defined in the research?”

Analytic

Being analytical means looking at the data to make data-based decisions, which means data must be collected on interventions. When looking at the data, if an intervention being used is not showing a change/ increase in the desired behavior then a change is warranted. Once the intervention is modified and data shows an increase in desired direction, then we can prove a reliable relationship between our intervention and the increase in positive behavior. This addresses the issue of believability: is the intervention being used and data showing the change be sufficient enough to prove a reliable functional relationship?

When looking at the data, if an intervention being used is not showing a change/ increase in the desired behavior then a change is warranted. Once the intervention is modified and data shows an increase in desired direction, then we can prove a reliable relationship between our intervention and the increase in positive behavior. This addresses the issue of believability: is the intervention being used and data showing the change be sufficient enough to prove a reliable functional relationship?

Behavioral

Behavior must be observable and measurable in order for it to be changed. If we can observe and see behavior, we can measure it with data, and then we can change it (Gilmore, 2019). When we say the term “behavior” it doesn’t just have to mean “bad” behavior, but behavior can also be appropriate or desirable behavior. Behavior Analysts want to increase some behaviors and decrease others. It is also important to describe “behavior change” in terms of how the child’s life is changed, rather than just their behavior.

Understanding the 7 dimensions of Applied Behavior Analysis and how it is implemented within your son or daughter’s goals and programming will help create more meaningful changes and produce a greater impact.

Citation

Baer, D. M., Wolf, M. M., & Risley, T. R. (1968). Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis1. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1(1), 91–97. doi:10.1901/jaba.1968.1–91

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2007). Applied behavior analysis(2nd ed.). Columbus, OH: Merrill Prentice Hall

Gilmore, Heather. “Seven Dimensions of ABA (Applied Behavior Analysis): Changing Human Behavior the Scientific Way.” Reflections from a Children’s Therapist, 30 Jan. 2019, pro.psychcentral.com/child-therapist/2015/07/seven-dimensions-of-aba-applied-behavior-analysis-changing-human-behavior-the-scientific-way/.

The Seven Dimensions of ABA

Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) is defined as “the science in which the principles of the analysis of behavior are applied systematically to improve socially significant behavior and experimentation is used to identify the variables responsible for behavior change. ” This definition can be overwhelming, but in this post we break down the defining characteristics and dimensions of ABA in a way that is much easier to understand.

” This definition can be overwhelming, but in this post we break down the defining characteristics and dimensions of ABA in a way that is much easier to understand.

1. Applied

We focus on behaviors that are socially significant to the individual and their life. We target behaviors that matter to them and that will affect their lives in a positive way. For example, we aren’t going to focus on teaching an individual who lives with his parents in Florida how to shovel snow. However, that might be a socially significant behavior for an individual living by himself in Nebraska.

2. Behavioral

We only target behaviors that can be seen and measured. For example, your child’s Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA) can’t target anxiety, because that is something that happens inside the body and mind and can’t be directly seen or measured. However, behaviors that often associated with anxiety could be targeted, such as crying, pacing, and running away.

3. Analytic

First and foremost, ABA is an evidence-based science. What does this mean? It means that everything we do and every intervention we use has years of data, research, and evidence behind it, proving objectively that it is effective in making the changes we want to see. While there may be some trial-and-error when finding out which data-driven intervention works best for your child, nothing is ever subjective or made up on the spot.

What does this mean? It means that everything we do and every intervention we use has years of data, research, and evidence behind it, proving objectively that it is effective in making the changes we want to see. While there may be some trial-and-error when finding out which data-driven intervention works best for your child, nothing is ever subjective or made up on the spot.

4. Technological

You will likely hear the word “objective” quite often throughout your experience with ABA. This is because everything we do is written out in such a way that only leaves one interpretation. We do this to rid our science of subjectivity, but also to make sure that our interventions can be easily replicated and replicated in the exact same way. Think about it like reading a recipe. You would rather it tell you to use exactly 1.5 teaspoons than “a couple” of teaspoons!

5. Conceptually Systematic

This is similar to Analytic, and simply means that every BCBA around the world will follow and derive their interventions from the theoretical base of ABA, not from guess work or other sciences that are not ABA.

6. Effective

We monitor your child’s progress very closely! Lack of progress is not your child’s fault; it indicates to us that the intervention being run is not effective and lets us know that we need to change something. We want to see significant changes that make your child’s life better, and if we don’t see that after an intervention has been given time to work, then we know it’s time to try something new!

7. Generality

We want your child to be able to use the skills they learn in all environments, across time, and with multiple people. This is called generalization and is something we focus on heavily when teaching your child new skills! Learning a skill in one setting is great, but the idea is to give them the most independence possible. The more ways and places your child can perform a skill, the more independent they can be.

You now have a better understanding of the seven dimensions of ABA! The process of starting therapy with your child is daunting, so we hope that knowing more about the therapy you are starting will help bring some clarity and comfort to the situation. If you have any questions about these dimensions do not hesitate to ask your child’s BCBA.

If you have any questions about these dimensions do not hesitate to ask your child’s BCBA.

*Informed consent was obtained from the participants in this article. This information should not be captured and reused without express permission from Hopebridge, LLC.

Review of some principles of behaviorism and concepts of learning. Applied behavior analysis. ~ Autism | ABA

According to behaviorism, learning includes the principles of respondent (classical learning) and operant conditioning (learning by consequences). The systematic application of these principles is often referred to as Applied Behavior Analysis or, for short, ABA or ABA Therapy. Applied Behavior Analysis is the systematic application and adaptation of behavioral principles using a single subject model. The one-subject model considers a single individual and analyzes his individual behavioral responses to antecedent and subsequent factors.

ABA therapists follow the ABC model. The A-B-C model assumes that the therapist evaluates and manipulates antecedents, behaviors, and consequences. Antecedents are any specific stimulus (ie, any event in the environment) that consistently predicts the occurrence of a reward or a reduction/punishment. As the child experiences various events in the environment, based on these events, he begins to predict what will happen next. He changes his behavior in an attempt to influence the consequences that are foreshadowed by the events around him. After the impact on his behavior, a second environmental event occurs for the child in the form of a consequence of his behavior. The experience of experiencing the consequences leads to the fact that the child changes his behavior in the future.

Consequences can be viewed in different ways. The standard point of view is to determine the consequences depending on whether a given consequence was realized or, on the contrary, eliminated, in combination with whether the behavior increased or, conversely, decreased as a result. Subsequent factors can be seen as positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive attenuation, and negative attenuation, depending on whether something was added to or removed from the environment, combined with whether the behavior increased or decreased as a result.

Subsequent factors can be seen as positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive attenuation, and negative attenuation, depending on whether something was added to or removed from the environment, combined with whether the behavior increased or decreased as a result.

| Increase behavior | Decrease behavior | |

| Presentation incentive | positive reinforcement | positive attenuation (Relaxation of the first type) |

| Removal of stimulus | negative reinforcement | negative Weaken (Debuff Type 2) |

If you provide the child with something he likes and the target behavior increases in the future, then it is said that there has been a positive reinforcement. If you provide the child with something that he does not like and his behavior decreases in the future, then we are talking about weakening the first type. If you eliminate something that the child does not want and the target behavior in similar circumstances decreases in the future, this is considered a negative or type II impairment. And if you eliminate something that had negative characteristics for the child, and the behavior in similar circumstances increases in the future, then it is considered that there was a negative amplification. The table above makes it easy to see and think about the different types of consequences. In reality, the consequences are not so clear cut. Positive gain, negative gain, type 1 and type 2 attenuations always work together and cannot be separated from each other. This is indeed a very important nuance.

If you provide the child with something that he does not like and his behavior decreases in the future, then we are talking about weakening the first type. If you eliminate something that the child does not want and the target behavior in similar circumstances decreases in the future, this is considered a negative or type II impairment. And if you eliminate something that had negative characteristics for the child, and the behavior in similar circumstances increases in the future, then it is considered that there was a negative amplification. The table above makes it easy to see and think about the different types of consequences. In reality, the consequences are not so clear cut. Positive gain, negative gain, type 1 and type 2 attenuations always work together and cannot be separated from each other. This is indeed a very important nuance.

Applied behavior analysis involves using the behavioral research strategies of a single subject model to change behavior. Learning happened if behavior changed. The main strategy of ABA therapy involves the operational definition of the target behavior, the collection of data on some dimensions and magnitudes of this behavior, the implementation of treatment and observation, and the registration of changes in the data obtained.

The main strategy of ABA therapy involves the operational definition of the target behavior, the collection of data on some dimensions and magnitudes of this behavior, the implementation of treatment and observation, and the registration of changes in the data obtained.

Let's first try to define behavior operationally. The target behavior must be defined in observable terms. For example, it is necessary to change the level of frustration in a child. How can frustration be defined in such a way that the description can be observed and recorded? Frustration can be defined as acts of physical aggression towards the environment or towards other people. You can go further and discuss what will be considered acts of aggression. Pushing other people, throwing objects, hitting objects, hitting people can all be defined as targeted aggressive behavior. It will be easy for an independent observer to count how many times one child has hit another and then to sum up how many times the child has been frustrated.

Operational definition of terms allows independent observers to accurately record data on how often a behavior occurs.

Once we have a definition of the behavior we want to change, we need to collect data on the baseline of that behavior. Before implementing the intervention, the frequency, duration, latency period, intensity and quality of behavior should be recorded. The purpose of collecting baseline data is to understand how often problematic behavior occurs. If we don't collect baseline data, but just start tracking data after the treatment is implemented, we will have no idea if the therapy we are implementing is working.

As soon as we have the initial baseline data, we need to start implementing the treatment. Changing the data in the right direction suggests that the manipulation of environmental factors was successful. A change in frequency, latency, intensity, or quality of behavior after therapy tells us that the therapy is working. The absence of changes in the above behavioral measures suggests that the therapy attempt was unsuccessful. When treatment efficacy is not reflected in the data collected, there is likely to be no functional relationship between the target behavior and the variables targeted for the intervention. In this case, such variables are evaluated and a different treatment strategy is formed.

When treatment efficacy is not reflected in the data collected, there is likely to be no functional relationship between the target behavior and the variables targeted for the intervention. In this case, such variables are evaluated and a different treatment strategy is formed.

There are many methods for recording data on each of the behavioral measures, such as measuring the frequency of a behavior, measuring the duration of a behavior, a time trial method, and the like.

There are three types of time trial behavior measurements: partial intervals, full intervals and instantaneous time trials (Rudrud, 2007). Once the method for recording data on any of the behavioral indicators is determined, it is necessary to choose a model for designing the experiment. The basic model for a single-subject experiment is the A-B model. Phase A collects behavioral data. Intervention (B) is then implemented and data collection continues. Another model of the experiment with one subject is the A-B-A-B model and the multilevel model. In the A-B-A-B model, data is collected, a treatment is added, then a treatment is removed, and another baseline data collection occurs, and only then the treatment is implemented again.

In the A-B-A-B model, data is collected, a treatment is added, then a treatment is removed, and another baseline data collection occurs, and only then the treatment is implemented again.

You will notice that if the therapy is effective, there is always a significant difference between the baseline data and the data collected in the intervention setting. Baseline data should be collected when the data is stable and shows a stable trend line (Rudrud, 2007).

There are ethical considerations that need to be taken into account when choosing an experimental model. As a rule, the A-B model is currently used by many specialists, since the withdrawal of effective treatment in most cases will be unethical. Baseline data is collected on some measure of behavior (A), a therapeutic strategy is implemented (B), and data is collected further to understand how the trend line in the target data is changing. Changing the trend regulates the direction of therapy.

For example, suppose a child hits his peers. To begin, data must be collected on antecedents, behaviors, and consequences. Johnny most often hits other kids when he plays with blocks. Whenever Johnny fights, another kid comes up to him, wanting to play with the blocks and himself. Johnny hits the baby, who cries and runs away.

To begin, data must be collected on antecedents, behaviors, and consequences. Johnny most often hits other kids when he plays with blocks. Whenever Johnny fights, another kid comes up to him, wanting to play with the blocks and himself. Johnny hits the baby, who cries and runs away.

From this information, we obtain data on the antecedents in the form of cubes and the approximation of another child. We also note the behavior (hitting) and the consequence of this behavior (running and crying child). In order to assess what are the controlling variables in a given situation, we can manipulate some of them. Remove the blocks and let Johnny play with the cars and then see if he reacts the same way to the other kids. In the above situation, Johnny's kicks are probably supported by the departure of another child. Johnny experiences an aversive situation due to the presence of a child. He hits him because in the past when he hit other kids, they left. That way, Johnny doesn't have to endure having them play with him and his blocks. When Johnny hits the therapist, the therapist continues to play with Johnny and ignores his punches. Since punches no longer solve the problem, Johnny will find some other solution for her. We, in turn, need to provide Johnny with alternative tools to solve this problem. We can also play more with Johnny so that he finds playing with other people rewarding compared to playing alone.

When Johnny hits the therapist, the therapist continues to play with Johnny and ignores his punches. Since punches no longer solve the problem, Johnny will find some other solution for her. We, in turn, need to provide Johnny with alternative tools to solve this problem. We can also play more with Johnny so that he finds playing with other people rewarding compared to playing alone.

Behavior can be classified as excessive/excessive and deficient/insufficient. Deficient behavior is a behavior that does not occur often enough. Excessive behavior is behavior that occurs too often. In order to increase behavior, a reinforcement procedure is used. To reduce the behavior, a relaxation procedure is applied.

Rudrud (2007) describes a proactive approach to reduce the overuse of attenuation in the behavior change process. Many problematic behaviors are behaviors that occur excessively often. Typically, problem behaviors are described as extreme by teachers or parents: "Johnny fights too much and yells too much", etc. The problem with identifying target behavior with such emotional utterances is that it is necessary to apply attenuation procedures in order to reduce the behavior. The proactive approach encourages therapists to pick up opposite, incompatible deficient behaviors and use reinforcement strategies to increase that deficient behavior.

The problem with identifying target behavior with such emotional utterances is that it is necessary to apply attenuation procedures in order to reduce the behavior. The proactive approach encourages therapists to pick up opposite, incompatible deficient behaviors and use reinforcement strategies to increase that deficient behavior.

Relaxation routines tell the child what NOT to do. Reinforcement procedures, on the other hand, tell the child what to do.

For example, Johnny often hits kids on the playground and in class every time he gets frustrated. Hitting is excessive, redundant behavior. We can provide a consequence (timeout) every time Johnny hits someone. The problem with using the relaxation procedure is that Johnny is taught what he shouldn't do, but he is not taught the alternative behavior. Another problem is that all of the behaviors that do occur come about because they are reinforced. That is, in essence, when we use the attenuation procedure, we impose an attenuation on the base of the gain. When the debilitating factor disappears, the behavior will continue to be reinforced and is likely to reappear.

When the debilitating factor disappears, the behavior will continue to be reinforced and is likely to reappear.

The proactive approach involves identifying the opposite alternative deficient behavior that we can encourage. In the case of Johnny's pugnacity, the deficient behavior can be defined as standing with arms relaxed at your sides. Then it is necessary to develop a program according to which an increase in calm standing with arms lowered to the sides will be carried out when Johnny is in a state of frustration. This is a strategy that uses differential reinforcement of incompatible behavior and is commonly referred to as replacing unwanted behavior with a more acceptable form of desirable behavior (DRI).

Another alternative would be to use the DRO (Derivative No Unwanted Behavior Gain) procedure. DRO stands for Differential Reinforcement of Other Behavior. In general, Johnny will be rewarded for not fighting during a certain scheduled time frame. If by the end of the agreed interval, Johnny has never hit anyone, he receives a promotion.

The final means of reducing undesirable behavior is the blanking procedure, or stopping the amplification. If the behavior is supported by the reaction Johnny gets when he fights, we can ignore the punches and not react. Since Johnny is no longer rewarded for his behavior, this behavior will decrease.

When teaching new behavior using the Applied Behavior Analysis approach, it is always necessary to start with task analysis. The behavior to be taught is broken down into its component parts. Task analysis provides learning consistency and allows you to evaluate learner skills (Rudrud, 2007).

Many of the tasks that therapists teach children to do are tasks that the child has not mastered. Since the child failed to learn these tasks, he could not progress in terms of development. There are a number of skills and tasks that need to be taught to a child for his normal development. Initially, it is desirable to start working with simple tasks, since more advanced skills are built on the basis of earlier skills and abilities.

If you plan to teach your child to come to you when you call his name, the child must first master the earlier developmental skills, such as the ability to understand and distinguish words, understand the conditioned sequences that have developed in the environment, and he must also be able to stand and walk. Task analysis identifies all the skills involved in the target behavior (approach when called by name). Each skill is then taught individually. Each of the behaviors will be chained together to form a more advanced behavior. If the child cannot learn individual steps in a given chain of behavior, then these steps are broken down into even smaller steps until we get a behavior that can be taught to the child using the block learning format. There are many ways to learn behavior, including end-to-end learning, end-to-end learning, and whole behavior chain learning. Whole chain of behavior training is often used in the case of typically developing children. Autistic children tend to learn faster by teaching behaviors from start to finish or from end to start.

The easiest way to teach a child a new behavior is to shape that behavior. Shaping (behavior shaping) involves the process of differentially rewarding behaviors that are close to the target behavior. Positive reinforcement of behaviors closer and closer to the target is provided. Clean shaping takes a fair amount of time. Therapists often use cues to speed up the learning process. If the individual does not know what behavior is expected of him, it is necessary to give him a hint to the correct behavior. There are various types of cues, including hand-over-hand physical cues, imitative cues or simulations, gesture cues, verbal and graphic cues. Also, clues are included in the environment and present outside of it. After the introduction of hints, they must be systematically gradually eliminated. In general, it's important to use the least invasive hints and eliminate them as soon as possible without losing behavior.

Applied Behavior Analysis uses a very systematic approach to teaching new behaviors. New behaviors are connected in a single chain and create a complex, complex behavior. Often, professionals reduce the amount of distractions so that the behavior is simple enough for autistic children to master. For this reason, the behaviors that a child learns in an environment with little or no distractions must be systematically expanded. Many of the behaviors that autistic children learn are highly situational and environmentally specific. One of the best ways to program response maintenance and stimulus generalization is to link target behaviors to functional skills that are automatically reinforced in natural environments and in the community.

New behaviors are connected in a single chain and create a complex, complex behavior. Often, professionals reduce the amount of distractions so that the behavior is simple enough for autistic children to master. For this reason, the behaviors that a child learns in an environment with little or no distractions must be systematically expanded. Many of the behaviors that autistic children learn are highly situational and environmentally specific. One of the best ways to program response maintenance and stimulus generalization is to link target behaviors to functional skills that are automatically reinforced in natural environments and in the community.

After the child has learned to behave in an environment with little or no distractions, he needs to practice this behavior in a variety of natural environments. People who interact with the child on a daily basis should be knowledgeable about the child's knowledge, and a plan should be developed to systematically generalize learned behaviors to the natural environment. Behaviors that work for the child's benefit and make him more successful in achieving desired goals will be better supported than behaviors that have no practical value for the child. The child will remember the behavior he wants to learn. The amplification modes should be less dense, and the amplification itself should be transferred to the natural environment. The child must learn how to independently manage antecedents and posterior factors (Rudrud, 2007).

Behaviors that work for the child's benefit and make him more successful in achieving desired goals will be better supported than behaviors that have no practical value for the child. The child will remember the behavior he wants to learn. The amplification modes should be less dense, and the amplification itself should be transferred to the natural environment. The child must learn how to independently manage antecedents and posterior factors (Rudrud, 2007).

Source: http://lundvandyke.com/resources/download/autism-treatment

How to teach a child to cooperate? Step 7 ~ Autism | ABA

14:19 Yulia Erz 7 comments

Related Articles

How to teach a child to cooperate? Step one.

How to teach a child to cooperate? Step two.

How to teach a child to cooperate? Step three.

How to teach a child to cooperate? Step 4

How to teach a child to cooperate? Step 5

How to teach a child to cooperate? Step 6.

Show your child that ignoring your instructions or choosing inappropriate behavior will not lead to a reward.

The seventh step in the process of achieving "Guiding Control" is the most difficult, but also indispensable. The whole point is that if the child does not fulfill the requirement or instruction that you give him, then he cannot get access to what he wants.

The child will not receive the desired object under any circumstances if he does not do what is required of him. His choice is simply not encouraged. In behavioral language, this action is called Extinction or Amplification Stop / Extinction.

If during a game with a child, or during classes, the child runs away - react calmly. You should not grab the child, hold or drag him back to practice by force. On the contrary, turn away and do not even look in his direction, and continue to do what you were doing before. Take care in advance that the child will not be able to start playing with his favorite toys, or eat his favorite treat, or do his favorite thing at this time. All the most interesting and favorite items of the child at this time are under your control, and the only way for the child to get them is to return to the place and continue to cooperate with you.

Take care in advance that the child will not be able to start playing with his favorite toys, or eat his favorite treat, or do his favorite thing at this time. All the most interesting and favorite items of the child at this time are under your control, and the only way for the child to get them is to return to the place and continue to cooperate with you.

In the beginning, the period of time that you are waiting for the child's return may be long, but do not spare time - in the future, it will pay off.

This is not lost time for nothing - at this time training is underway. Your child is learning to cooperate with you and make the right choices. And, gradually, these periods of time will be reduced, and you will be able to come to the conclusion that the child will not only not avoid classes, but will even take the initiative and demand to study.

Using the Extinction Extinction procedure is one of the most effective tools to reduce unwanted behavior. The first six steps to achieving "Guiding Control" help to instantly increase the frequency of the desired behavior, and when used correctly, make everyday interaction with the child much easier. As long as the child cooperates with you, you are having a great and fun time. But the amplification stop effect does not appear instantly. The result comes in the future, and is based on the absence of reinforcing unwanted behavior. You apply the seventh stage of the "Guiding Control" training every time you want to reduce undesirable behavior.

The first six steps to achieving "Guiding Control" help to instantly increase the frequency of the desired behavior, and when used correctly, make everyday interaction with the child much easier. As long as the child cooperates with you, you are having a great and fun time. But the amplification stop effect does not appear instantly. The result comes in the future, and is based on the absence of reinforcing unwanted behavior. You apply the seventh stage of the "Guiding Control" training every time you want to reduce undesirable behavior.

In fact, "not encouraging" unwanted behavior seems easy only in theory. In practice, each time a previously reinforcing behavior stops reinforcing, a so-called "explosion" occurs, and the unwanted behavior may increase for a short period of time, become more intense, and even change form.

For example, if earlier, when a child was called to study and the TV was turned off, he would start squealing and throw himself on the floor, and after that he was allowed to continue watching TV (" God forbid, the child will be injured! Psychological!" ;-), then now, if the TV remains turned off, the child will begin to squeal even more, even more strongly, and may start to beat his head on the floor.

Here, basically, the main mistake of parents and teachers occurs - at the very peak of squealing and screaming, the child turns on the TV to calm down (" Well, to hell with them, with classes, if only there was no trauma! Psychological!" ). And in this way, unwanted behavior, only in an even more severe form, is reinforced and strengthened.

In other words, in order to effectively apply the seventh stage, it is necessary to prepare for the "explosion", both mentally and physically, and always act consistently and not give in. The results will not keep you waiting. If on the first day the child's tantrum lasts 40 minutes, the next day it will last much less, and on the third or fourth day it may not occur at all. Of course,

with sequential application of.

Due to the danger of exacerbating more severe behavior during an explosion, it is advisable to enlist the support of loved ones or specialists who will help you survive the "explosion", and keep your cool, continue life.

Many parents choose not to try to deal with the "explosion" because in the early stages, the behavior becomes too unbearable (" This trauma again! Psychological!" ), and they are afraid to harm the child with their refusal. But, in fact, the increase in a more severe form of behavior causes much more harm to the child than the possible "psychological" trauma. After all, a child who does not know how to cooperate with others will not be able to learn the necessary skills, become independent and integrate into society. And besides this, there is a very high probability that over time the unwanted behavior will become so problematic that it will become necessary to use more unpleasant methods of correction and psychotropic drugs.

Establishing "Guiding control" is hard everyday work, not only for one specific person, but for all those around the child. But, mainly through this work, you can help the child to express himself to the fullest.