Cognitive behavioral therapy questions for clients

Cognitive Restructuring Techniques for Reframing Thoughts

Do you ever find yourself following a certain train of thought, without consciously deciding to go down that path, that takes you to a sad or upsetting conclusion?

I’m going to assume you answered affirmatively since you’re human! (If you’re not a human, feel free to skip this piece.)

It’s in our nature to come up with schemas, or thought patterns and assumptions, about how things work. Without them, we would have to approach every problem as a brand new one, with no pre-existing experiences, problem-solving techniques, or lessons learned to draw from.

The issue with these schemas is that they are not always accurate. We do not always come up with the best and most effective methods for solving problems, but these methods can get saved to our subconscious anyway.

Fortunately, all hope is not lost if you have internalized a faulty perspective! There is an effective, evidence-backed process of reframing or restructuring these faulty ways of thinking that can help you right the biased, skewed, or just plain inaccurate beliefs you hold.

Read on to learn about cognitive restructuring and how it can help you improve your thinking.

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our 3 Positive CBT Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will provide you with a detailed insight into Positive CBT and will give you the tools to apply it in your therapy or coaching.

This Article Contains:

- What Is Cognitive Restructuring or Cognitive Reframing? A Definition

- What Role Does CR Play in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy?

- Magnification, Overgeneralization, and Other Cognitive Distortions

- Cognitive Restructuring Techniques: Socratic Questioning, Guided Imagery, and More

- 9 Cognitive Restructuring Worksheets (PDF)

- A Take-Home Message

- References

What Is Cognitive Restructuring or Cognitive Reframing? A Definition

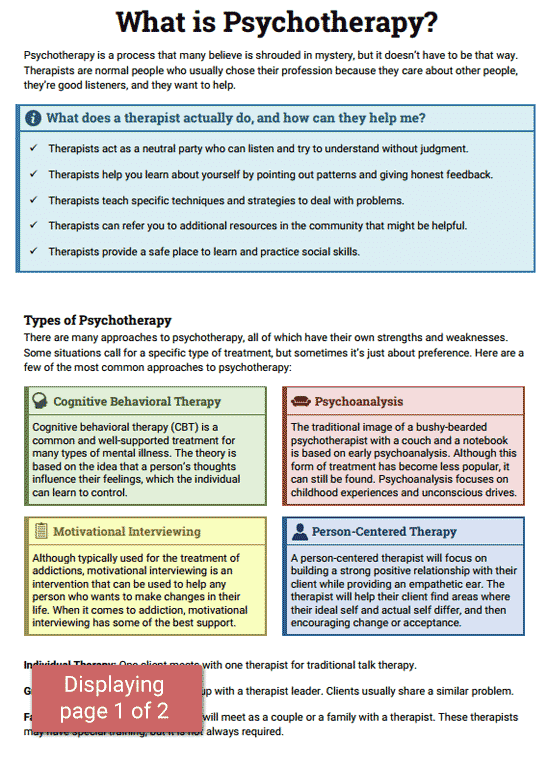

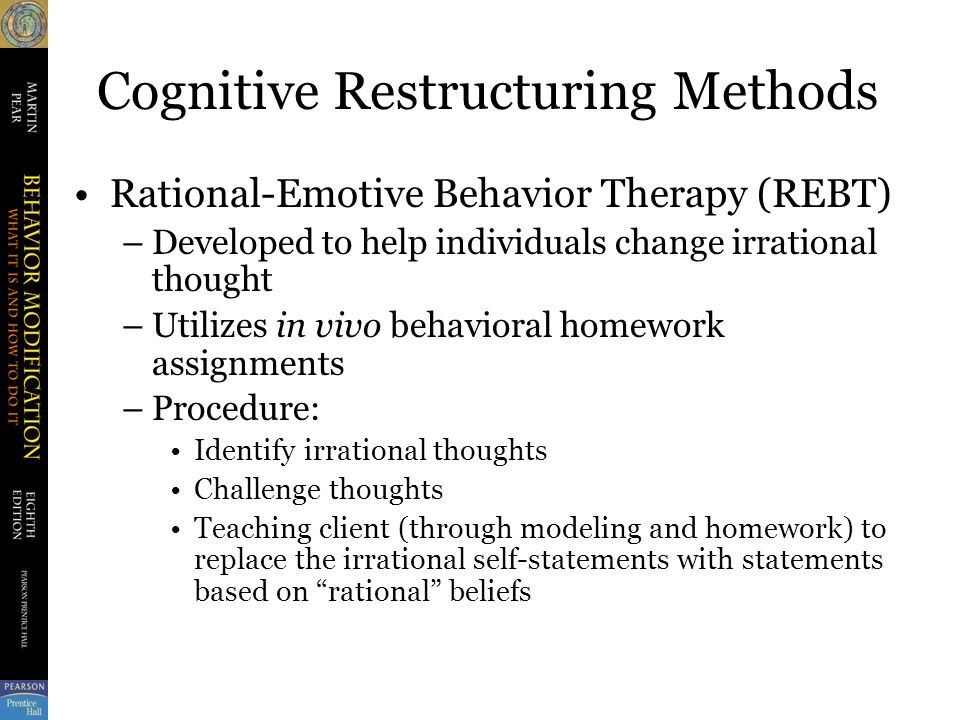

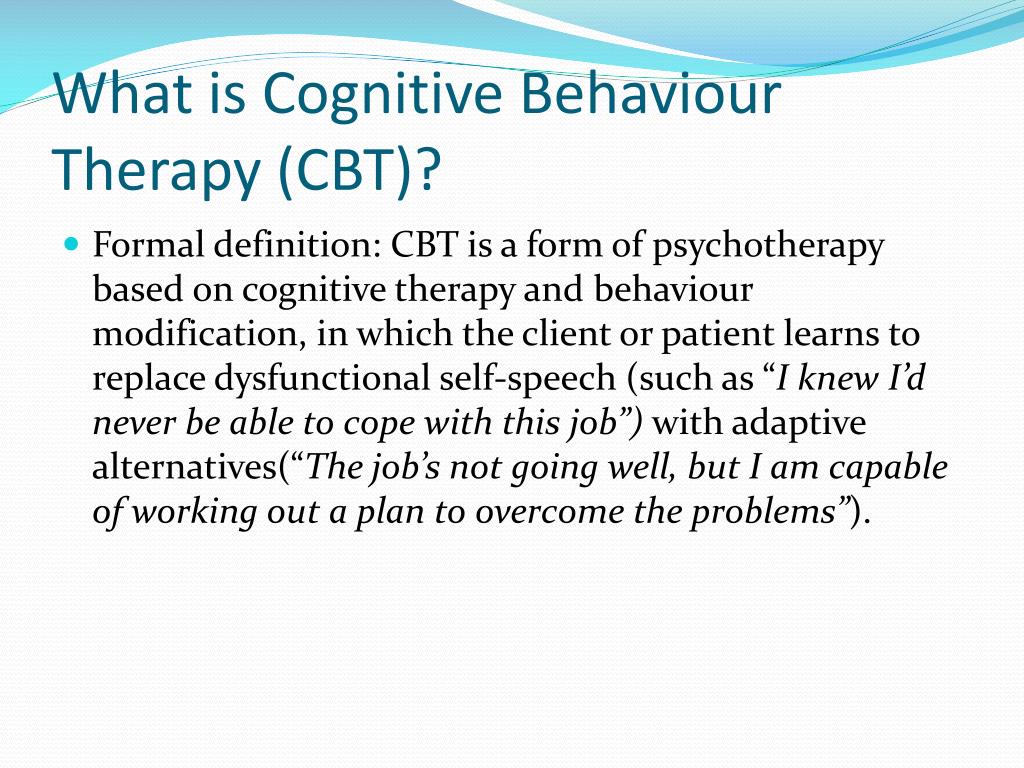

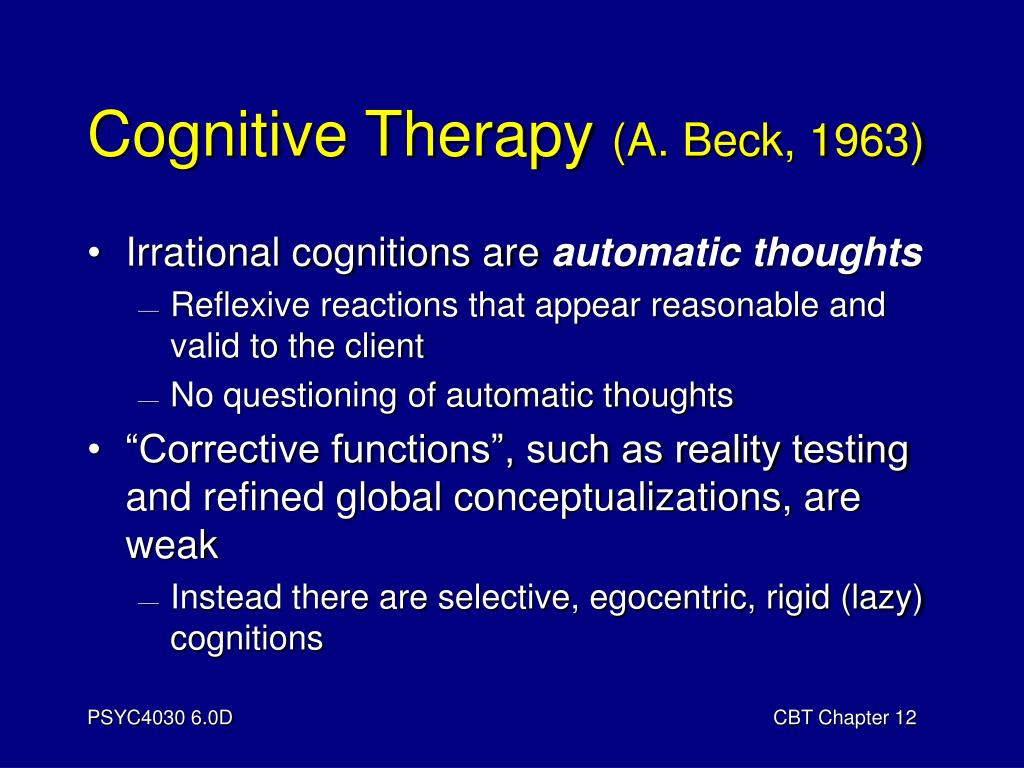

Cognitive restructuring, or cognitive reframing, is a therapeutic process that helps the client discover, challenge, and modify or replace their negative, irrational thoughts (or cognitive distortions; Clark, 2013).

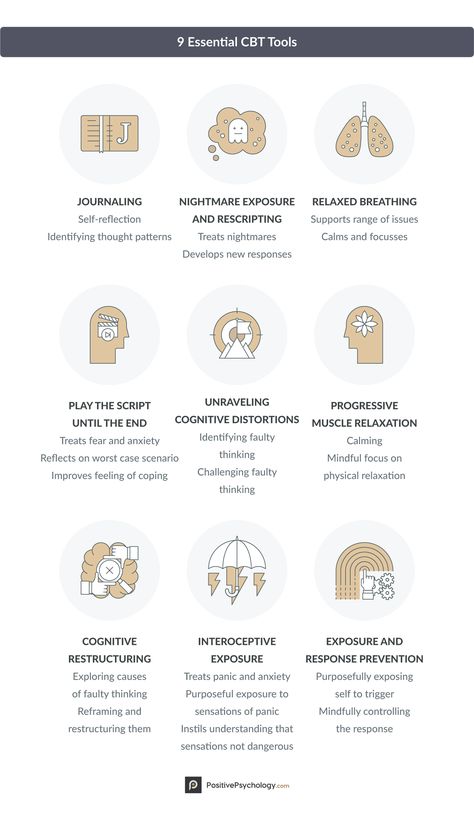

It is a staple of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and a frequently used tool in a therapist’s toolbox because many of our problems are caused by faulty ways of thinking about ourselves and the world around us. Cognitive restructuring aims to help people reduce their stress through cultivating more positive and functional thought habits (Mills, Reiss, & Dombeck, 2008).

Although it may seem overwhelmingly difficult to change your own ways of thinking, it is actually comparable to any other skill – it is hard when you first begin, but with practice, you will find it easier and easier to challenge your own negative thoughts and beliefs.

What Role Does CR Play in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy?

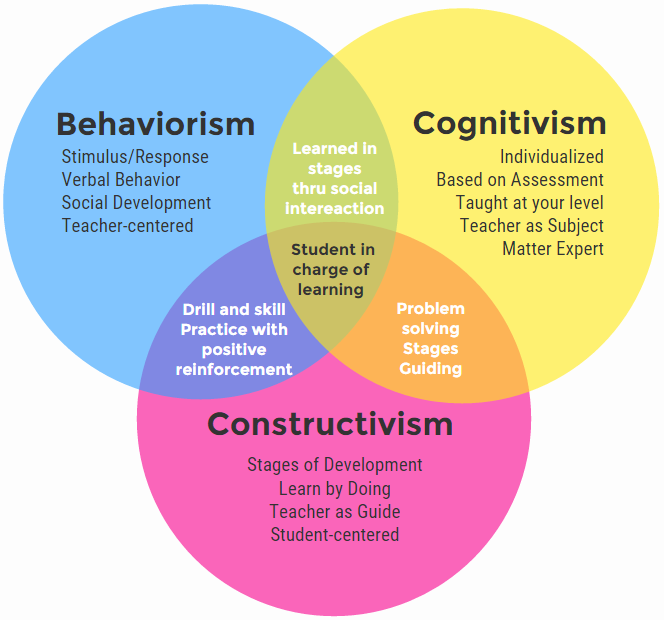

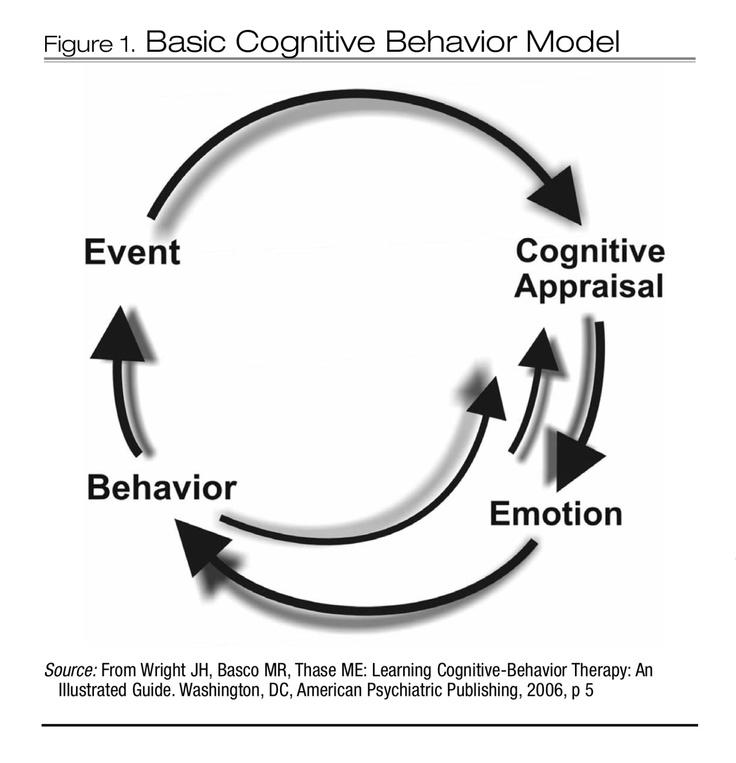

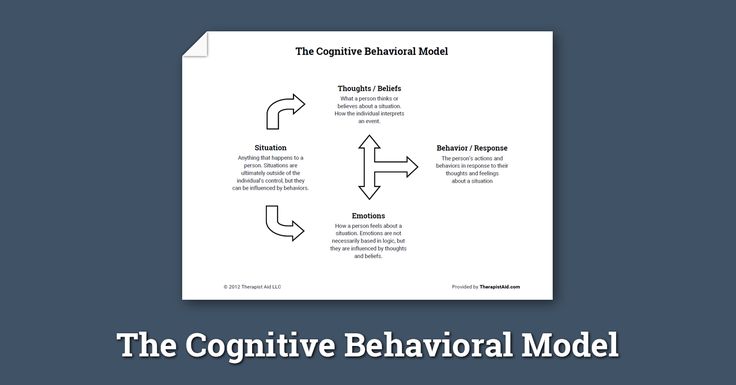

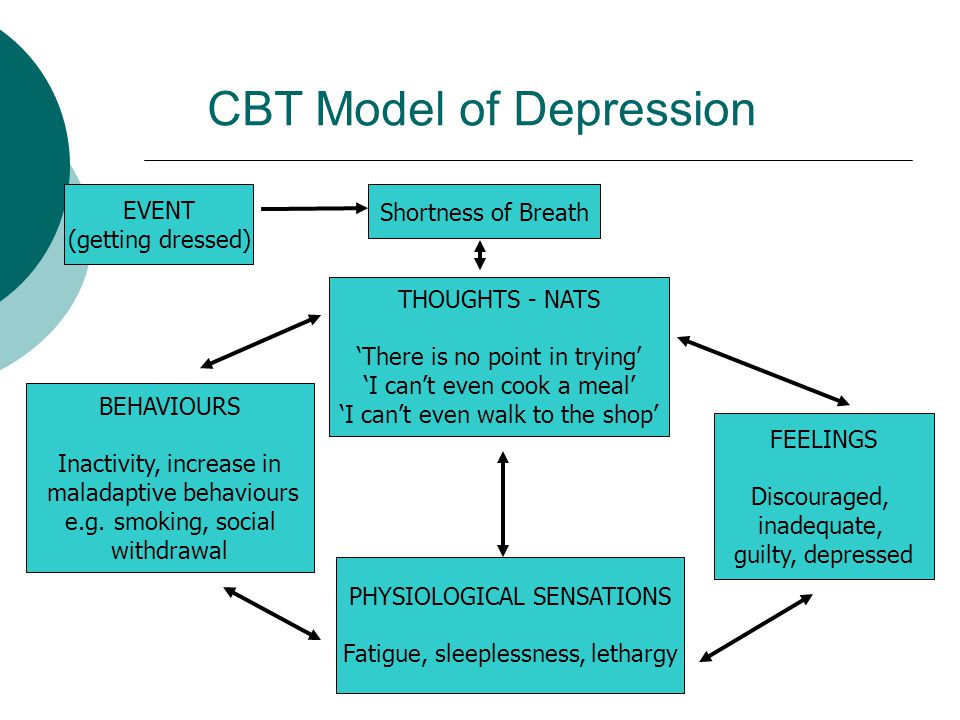

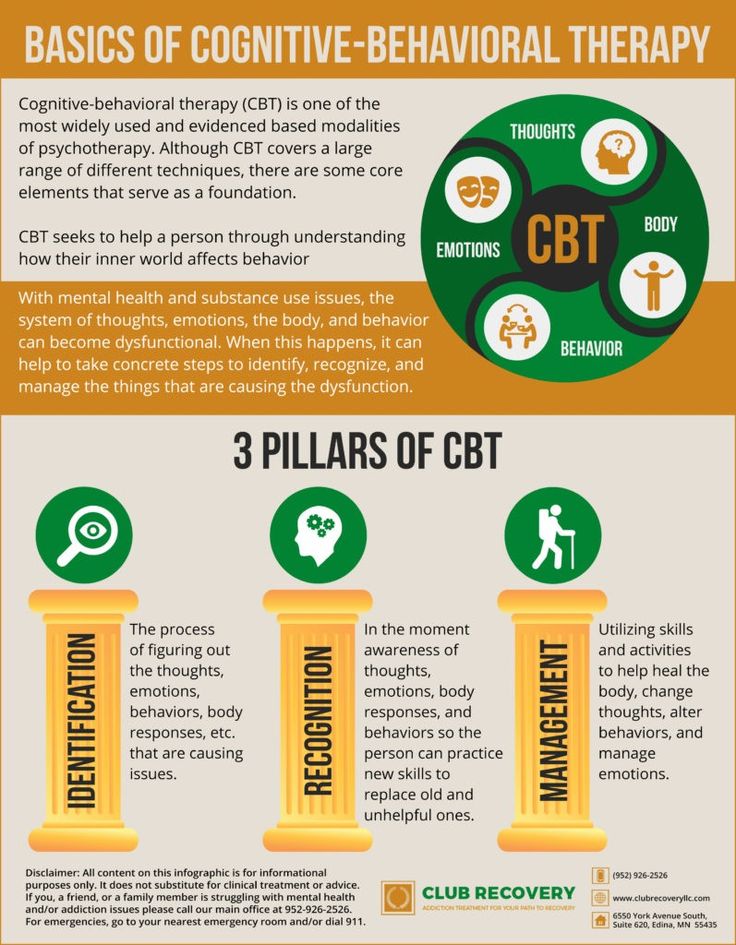

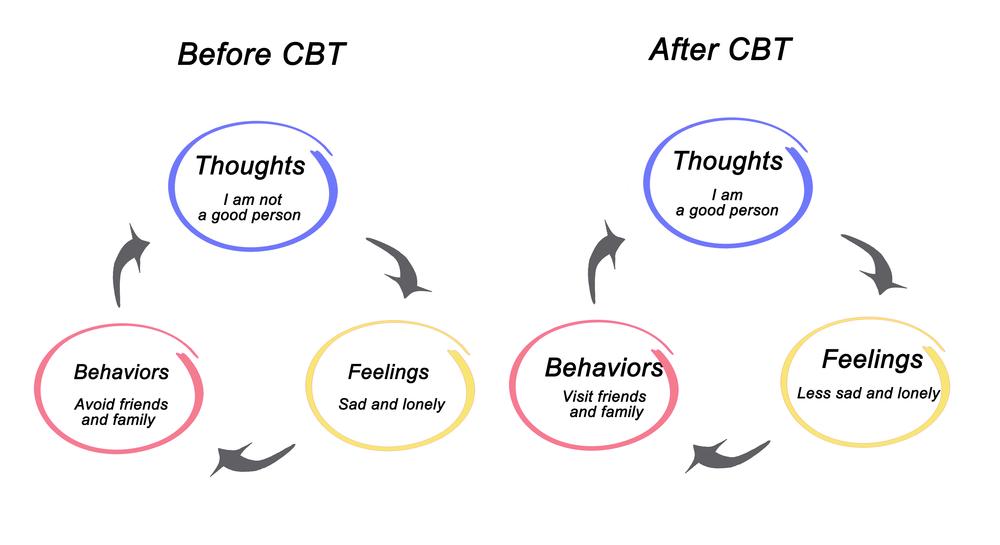

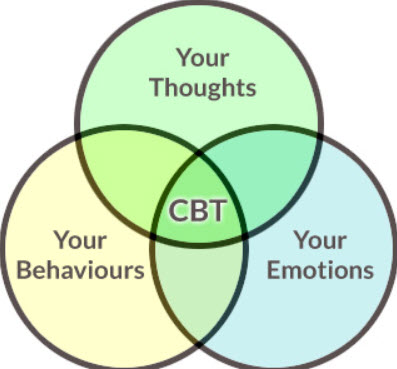

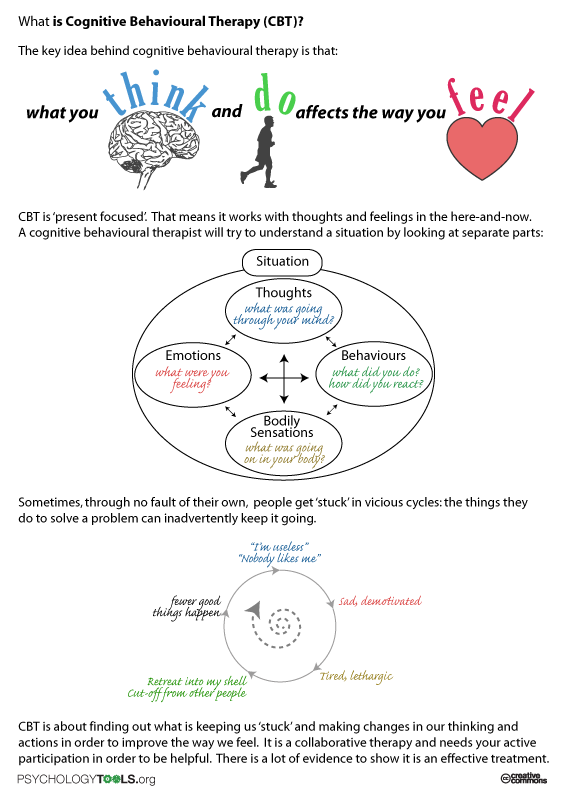

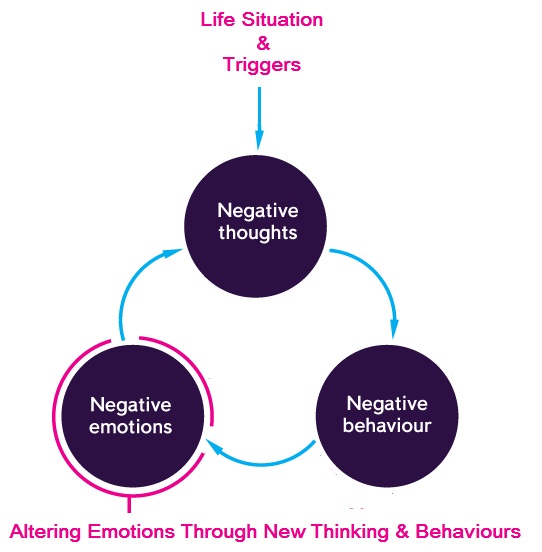

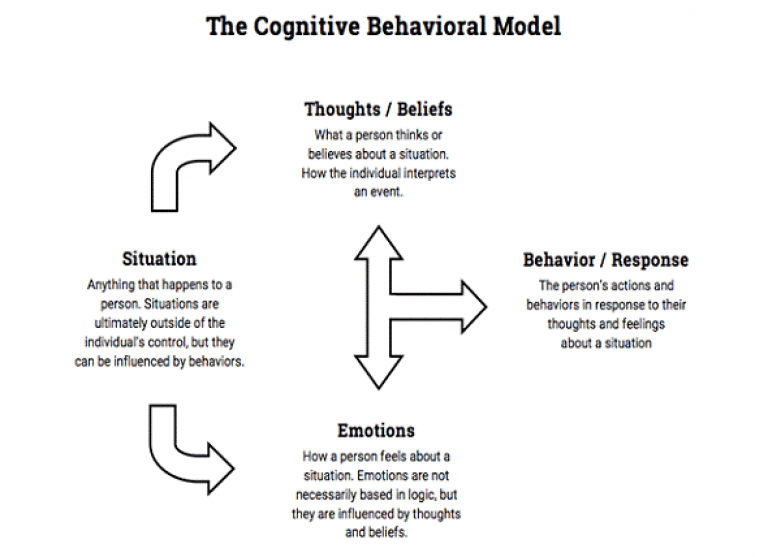

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, or CBT, is built on the idea that the way we think affects the way we feel. It is easy to see the logic behind this idea, and the implications of faulty ways of thinking.

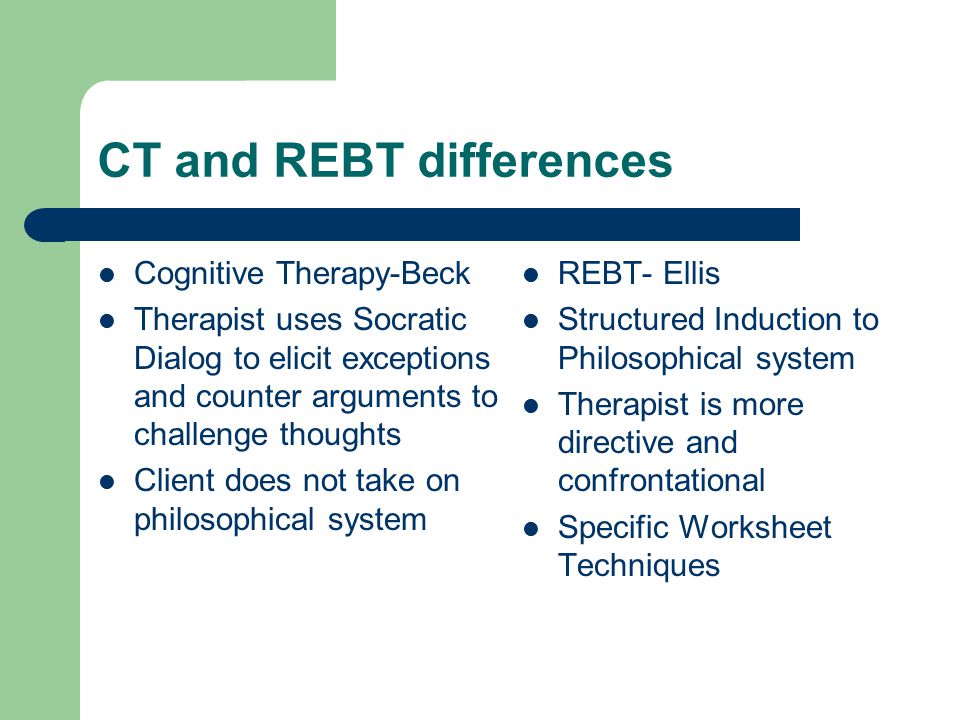

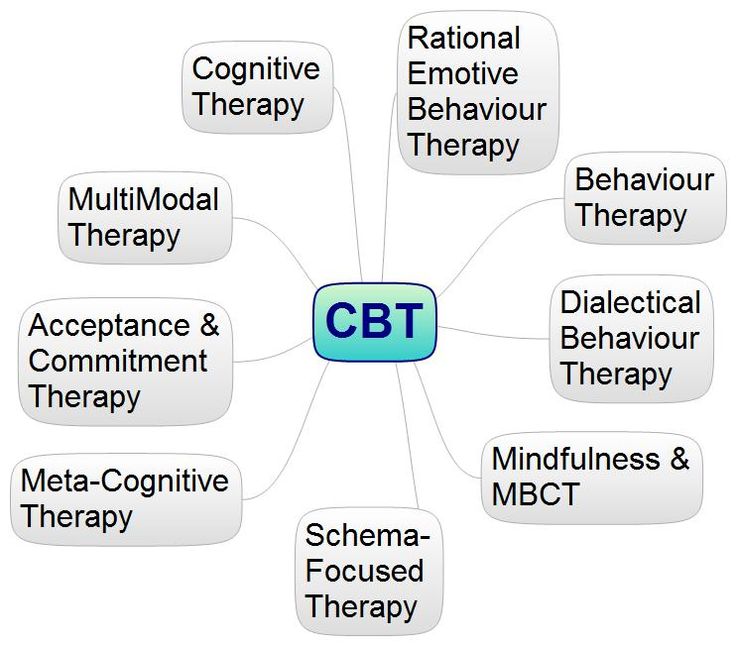

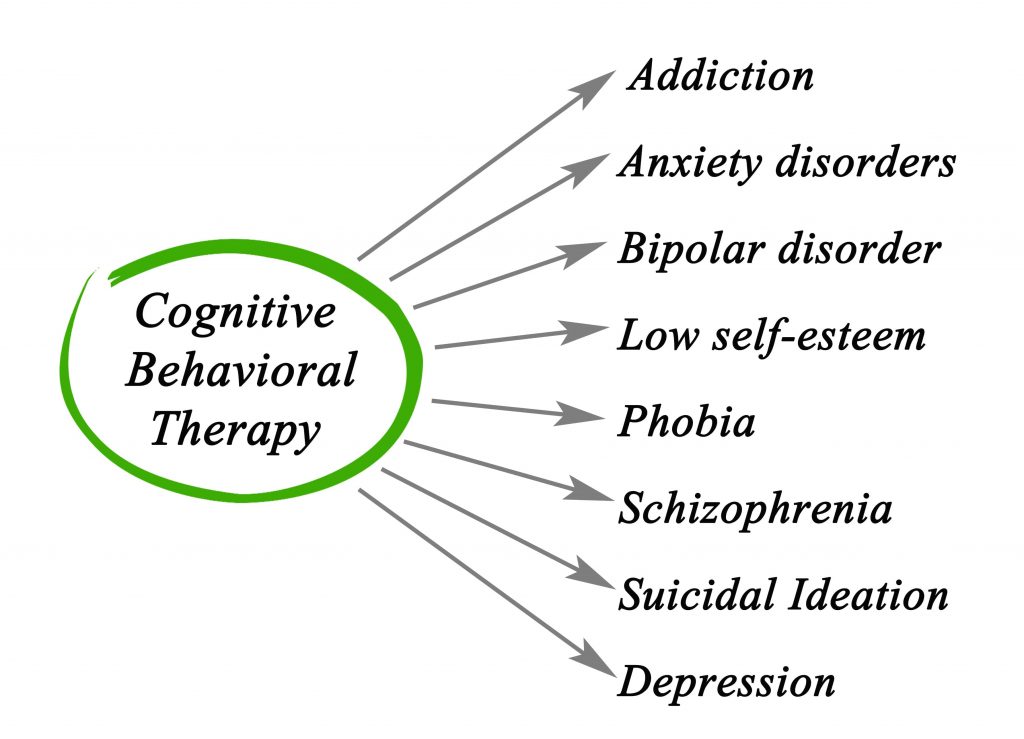

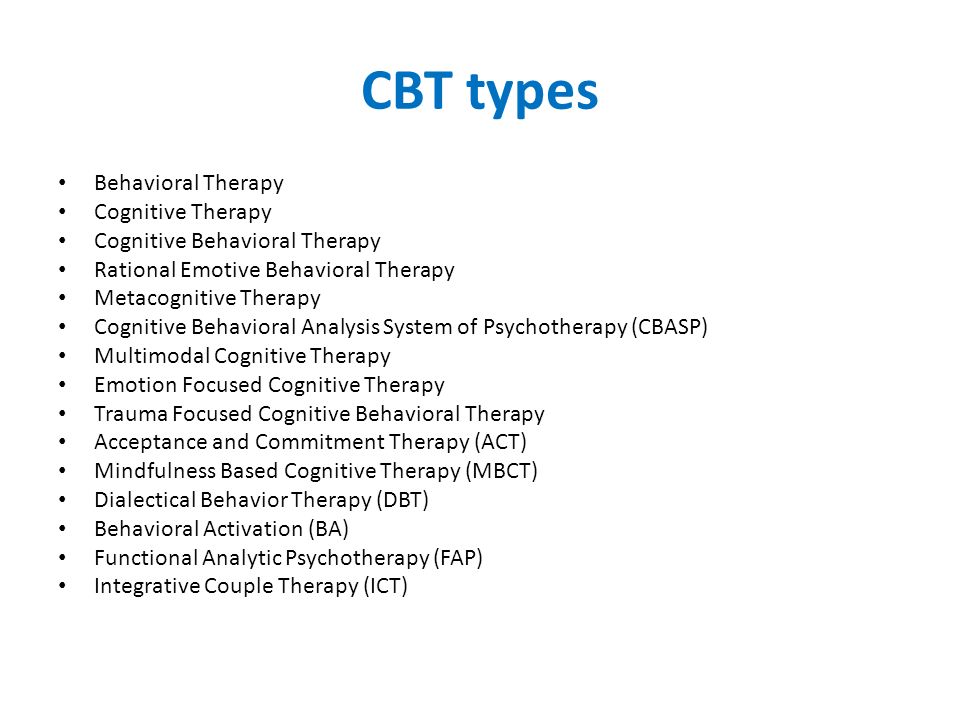

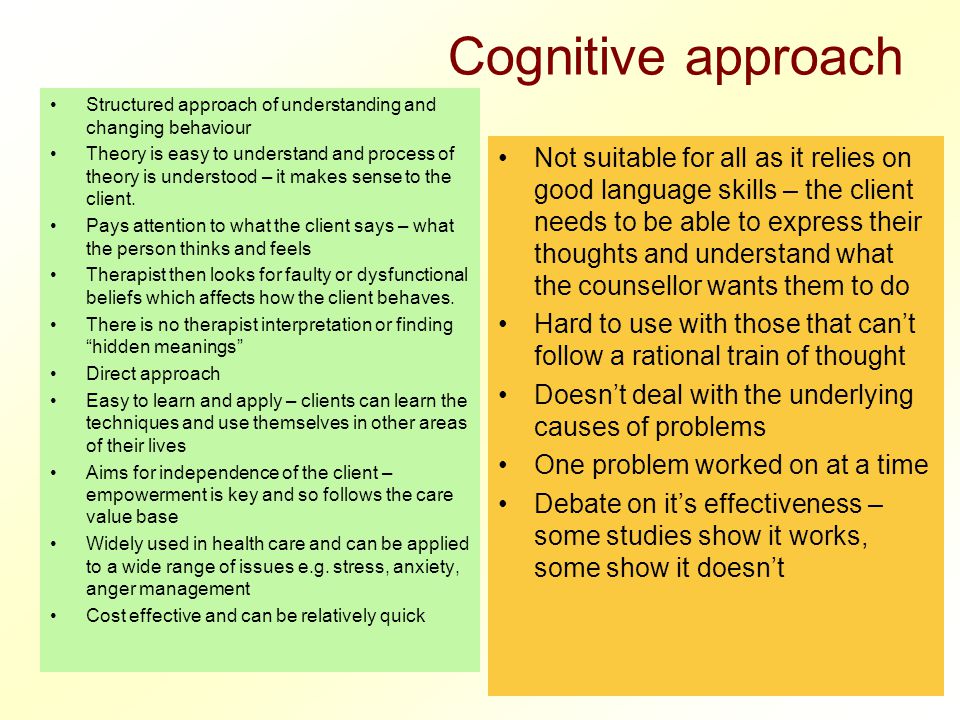

Cognitive restructuring was first developed as a therapeutic tool of CBT and Rational Emotive Behavioral Therapy, or REBT (Mills, Reiss, & Dombeck, 2008). CBT practitioners quickly found that it was an adaptable and flexible tool that could help a wide range of people dealing with all kinds of problems, whether the problems were due to outside factors, internal issues, or both.

CBT practitioners quickly found that it was an adaptable and flexible tool that could help a wide range of people dealing with all kinds of problems, whether the problems were due to outside factors, internal issues, or both.

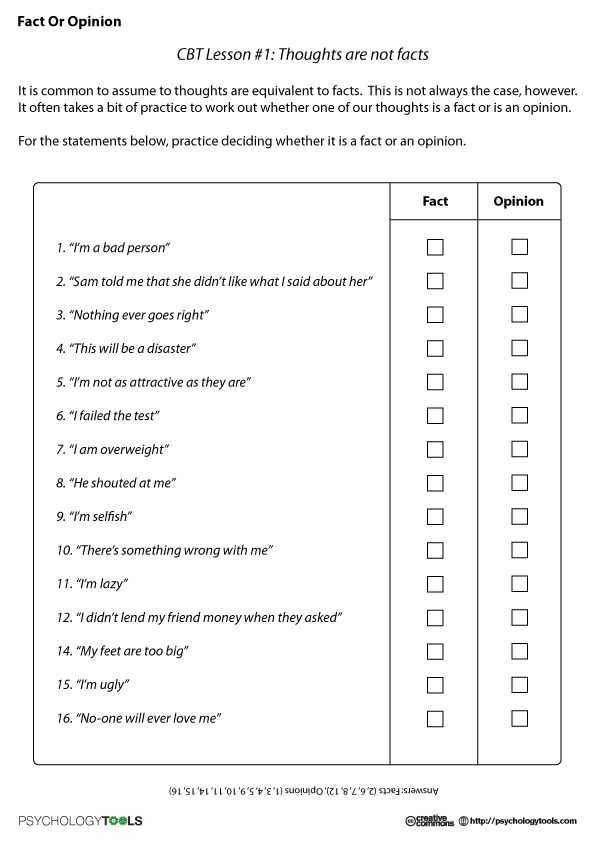

This method of addressing problems and promoting healing makes up the bulk of CBT sessions and offers dozens of techniques and exercises that can be applied to nearly any client scenario. Applied correctly, it will help the client learn to stop automatically trusting his or her thoughts as representative of reality and begin testing his or her thoughts for accuracy (Mills, Reiss, & Dombeck, 2008).

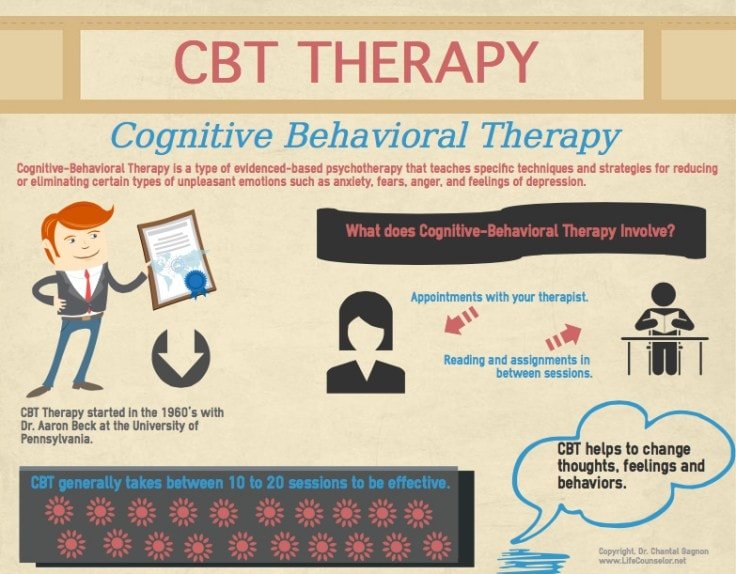

To learn more about how CBT uses cognitive restructuring techniques, watch this video of CBT founding father Aaron Beck discussing this method.

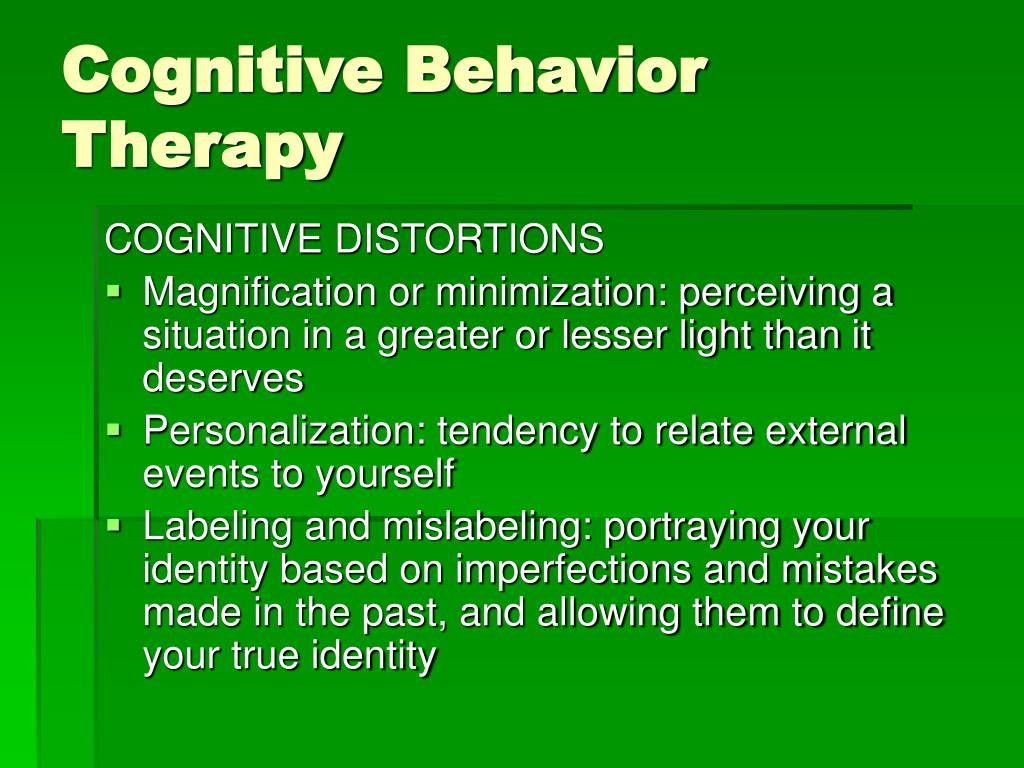

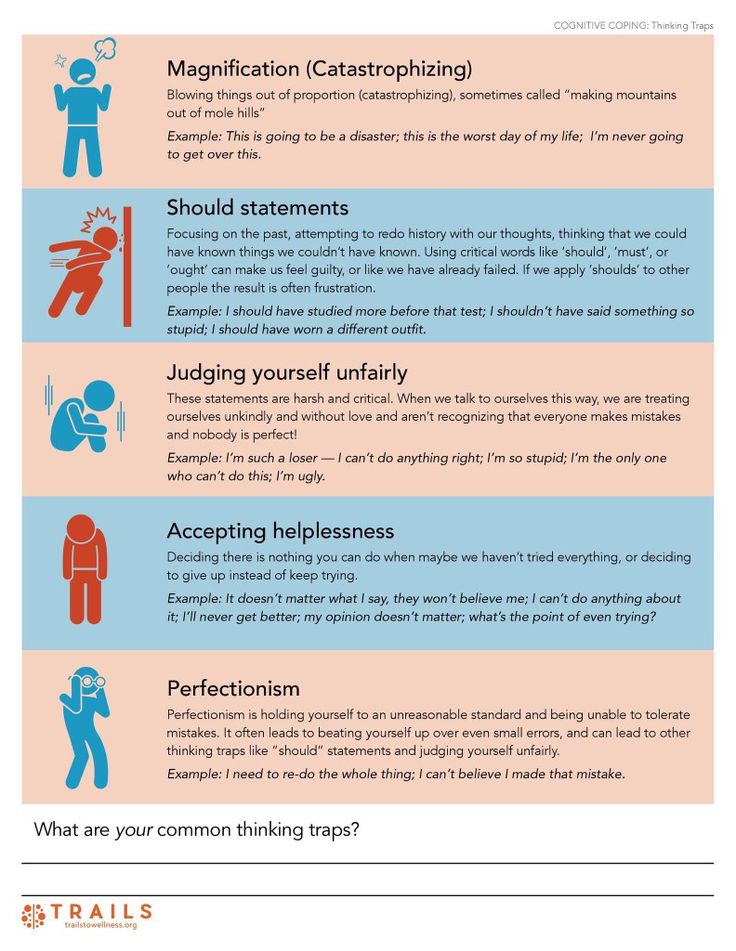

Magnification, Overgeneralization, and Other Cognitive Distortions

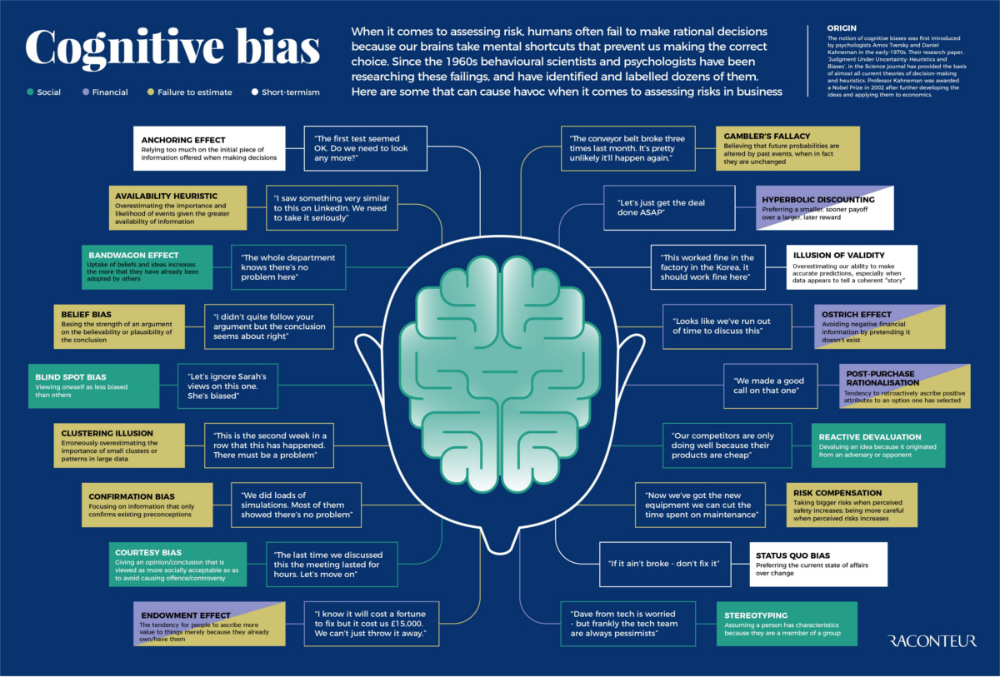

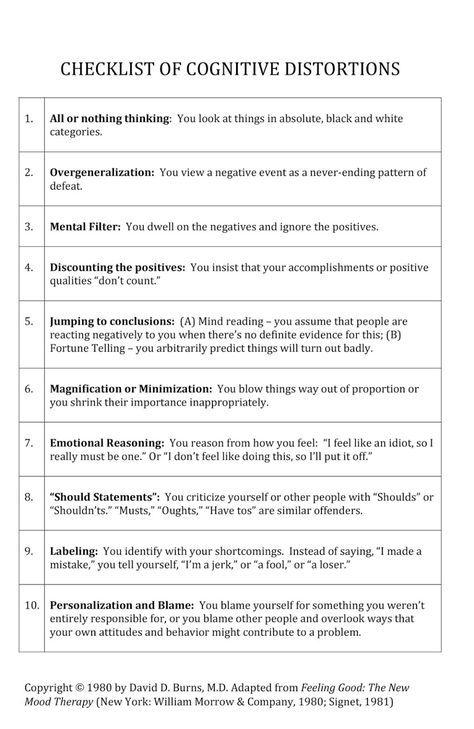

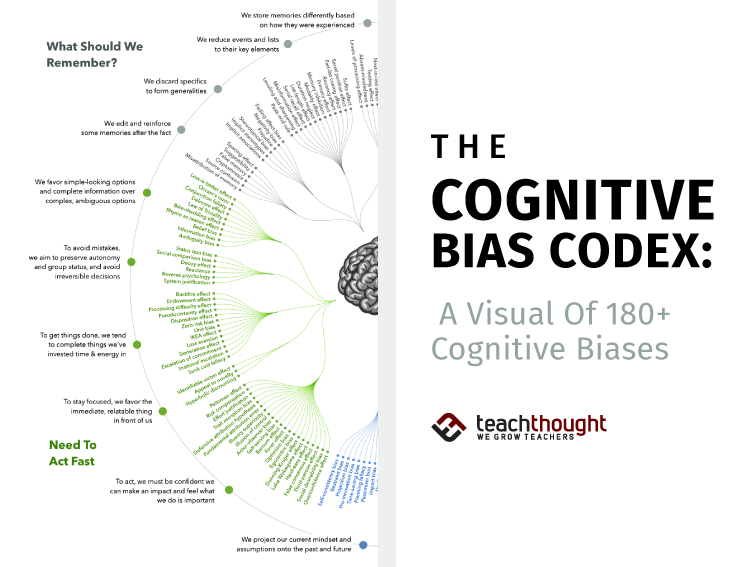

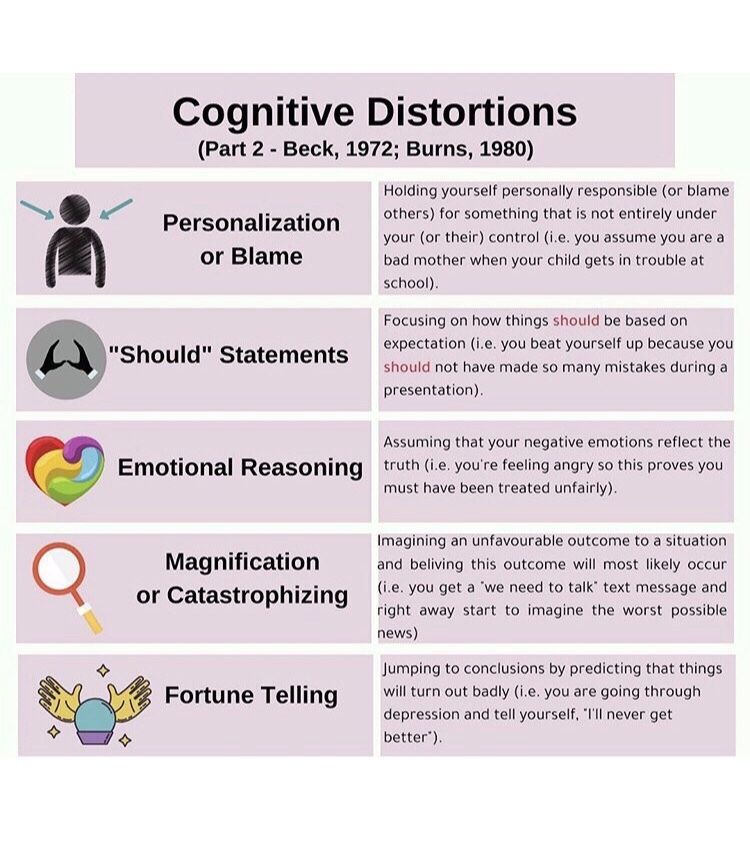

There are so many ways our thinking can play tricks on us that it’s almost surprising that we think in a more functional way most of the time! These tricks are known as “cognitive distortions” in psychology.

Cognitive distortions are faulty or biased ways of thinking about ourselves and/or our environment (Beck, 1976). They are beliefs and thought patterns that are irrational, false, or inaccurate, and they have the potential to cause serious damage to our sense of self, our confidence, and our ability to succeed.

One of the most common cognitive distortions is magnification or minimization, a damaging distortion that affects how we evaluate the things that happen to us (Yurica & DiTomasso, 2005). You can read more in our cognitive distortions article about magnification, overgeneralization, and other common cognitive distortions.

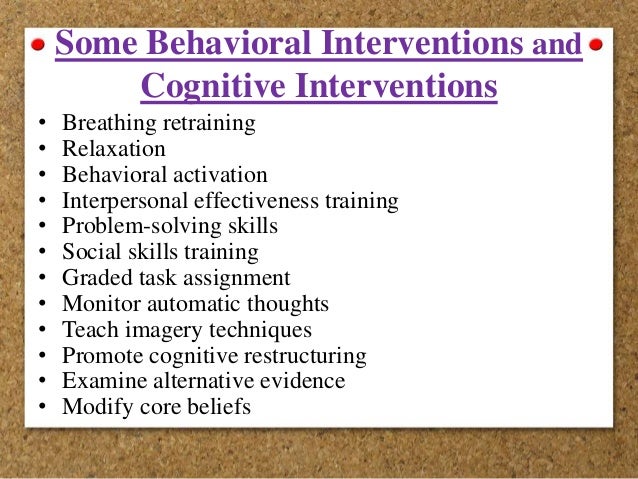

Cognitive Restructuring Techniques: Socratic Questioning, Guided Imagery, and More

Luckily, although cognitive distortions are stubborn and surprisingly insidious thought patterns, there are ways to combat them! Cognitive restructuring techniques have had great success in identifying, challenging, and replacing faulty ways of thinking with more accurate, helpful, and positive ways of thinking.

Increasing Awareness of Thoughts

The first step toward fixing faulty thinking is to identify your faulty thinking. Increasing your awareness of your own thoughts, particularly your overly negative or biased thoughts, is a vital piece of this process.

It will take time and effort to improve your awareness of your own thoughts. It’s not a natural practice for people to stop in the middle of experiencing an intense emotion and think about how they got to where they are! Although it is difficult, you will find that the outcome is worth the effort.

Begin looking for cognitive distortions by turning on your internal “radar” for negative emotions. Think about when your depression, anxiety, or anger symptoms are at their worst. If it’s too difficult to start with your emotions, start with behaviors instead. Ask yourself what behaviors you would like to change, then identify what triggers those behaviors.

You can think of these situations as “alarm” situations, or situations that alert you to the presence of one or more cognitive distortions.

Some example alarm situations include:

- You notice a feeling of anxiety before going out with friends. Your heart races, and you sweat.

- You start arguments with your partner after you’ve had a meeting with your boss. The arguments always start over something minor, like chores.

- When a big assignment is due at school, you put it off until the last minute. Small assignments are no problem.

- You feel depressed when you have to spend an evening alone. You feel so lonely that you can’t take it.

Consider these alarm situations and think about similar situations in your own life. Are there scenarios that frequently bring out uncomfortable or painful emotions? Do certain situations tend to have a larger than expected impact on your mood?

Do your best to identify as many triggering situations as you can, and the more specific they are, the better! It’s incredibly helpful to have a list of your most common or most significant triggers when beginning your cognitive restructuring work.

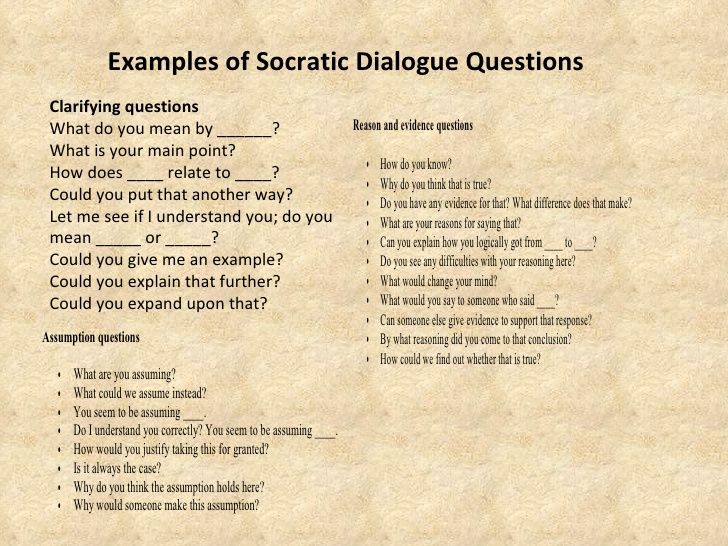

Socratic Questioning

Socratic questioning is a very effective cognitive restructuring technique that can help you or your clients to challenge irrational, illogical, or harmful thinking errors.

The basic outline for this technique is to ask the following questions:

- Is this thought realistic?

- Am I basing my thoughts on facts or on feelings?

- What is the evidence for this thought?

- Could I be misinterpreting the evidence?

- Am I viewing the situation as black and white, when it’s really more complicated?

- Am I having this thought out of habit, or do facts support it?

Thoughts are a running dialogue in our minds, and they can come and go so quickly that we can barely understand them, let alone have time to address them.

The first step is to identify the thoughts that you feel need to be questioned. Think of a specific thought that you suspect is destructive or irrational, especially one that pops into your head quite a lot.

Next, consider the evidence for and against this thought. What evidence is there that this thought is accurate? What evidence exists that calls it into question?

Once you have identified the evidence, you can make a judgment on this thought. Weigh the evidence for the thought and the evidence against the thought, and decide whether it is more likely to be accurate or false. Determine whether it is based on the facts or on your feelings.

Next, you answer a question on whether this thought is truly a black and white situation, or whether reality leaves room for shades of grey. This is where you think about whether you are using all-or-nothing thinking, or making things unreasonably simple when they are truly complex.

This detailed Cognitive Restructuring Worksheet uses “Socratic questions” to encourage a deep dive into thoughts that plague you, and offer an opportunity to analyze and evaluate them for truth. If you are having thoughts that do not come from a place of truth, this worksheet can be an excellent tool for identifying and defusing them.

Guided Imagery

You probably already know that visualization can be a great tool for relaxing, managing pain, getting anxiety under control, and neutralizing anger.

You may not have known that it can also be an extremely effective method of cognitive restructuring.

There are three main categories of guided imagery that a therapist can guide their client through cognitive restructuring:

- Life Event Visualization

- Reinstatement of a Dream or Daytime Image

- Feeling Focusing

CBT therapists looking to support their clients using guided imagery might point them toward recordings they can purchase, many of which accompany CBT workbooks or come as guided audio meditations.

Alternatively, practitioners may wish to pre-record their own audio that guides their clients through cognitive restructuring exercises.

Using a digital psychotherapy platform such as Quenza (pictured here), these pre-recorded audio clips can be sent directly to the client’s smartphone or tablet, where they will be available to complete when needed, such as during moments of pain or anxiety.

The advantage of distributing these recordings via such a platform is that the therapist can then track the completion of the sessions from their own devices. This may provide useful content for exploration during in-person therapy sessions, such as regarding the timing and frequency with which clients choose to engage with cognitive restructuring exercises.

Let’s now look more closely at key types of guided imagery exercises for cognitive restructuring.

– Life Event Visualization

This technique involves having the client identify a specific event or theme that is the focus of the therapy sessions (Edwards, 1989). This event could be something recent and particularly salient, like an argument with a loved one, or something from the past that still has a strong impact on the client, like being bullied or a harsh rejection from childhood. If the focus is on a theme, the client will keep this theme in mind and let an image arise organically.

– Reinstatement of a Dream or Daytime Image

This imagery technique focuses on a specific image that the client has already had. The image could be one that the client encountered in a dream, daydream, fantasy or previous guided imagery session. Wherever it came from, it will hold some inherent meaning to the client and may cause the client to feel anxious, sad, upset, or another emotion intensely.

The image could be one that the client encountered in a dream, daydream, fantasy or previous guided imagery session. Wherever it came from, it will hold some inherent meaning to the client and may cause the client to feel anxious, sad, upset, or another emotion intensely.

– Feeling Focusing

The final imagery type is characterized by the client focusing on a feeling he or she is experiencing in the session, and letting an image arise from the feeling. An image will usually arise spontaneously, but if not, a technique called multisensory evocation can help to clarify an image. For this technique, the therapist will direct the client through an exploration of the senses to help sharpen the image and identify more detail.

Once the client has an image in mind, the therapist will move on to assessing the meanings that the image hold for the client. There are several assessment techniques a therapist may use, including:

- Prompted soliloquy – the therapist directs the client to identify as an object or entity from the image (e.

g., a client who visualized a lake drying up was directed to “be the lake”), and speak from the position of this object or entity (e.g., the client would speak about how it felt to be the lake, and what its drying up meant).

g., a client who visualized a lake drying up was directed to “be the lake”), and speak from the position of this object or entity (e.g., the client would speak about how it felt to be the lake, and what its drying up meant). - Interview – in this technique, the client will once again take on the role of an object or entity from the image, and the therapist will ask specific questions of the client in this role.

- Prompted dialogue – similar to the previous techniques, this technique involves the client taking on a role and addressing one of the other objects or people in the imagery (e.g., the client could identify as the lake and address the trees around the lake).

- Prompted descriptions – this basic technique simply refers to the therapist’s use of frequent questions about what the client is seeing and feeling.

- Prompted transformation – the therapist may suggest that the client shifts or changes the image; this can be especially helpful when the current image has reached the end of its usefulness as a discussion piece.

However a therapist and client work together to identify the meanings attached to the image, the next step will help them to begin challenging, restructuring, or replacing harmful assumptions and beliefs.

Some of the techniques a therapist may use to guide a client through restructuring include summary and reframing, directed dialogue, prompted dialogue, directed transformation, and prompted transformation.

– Summary and Reframing

This restructuring method refers to the therapist’s summarizing what he or she has learned from the client and suggesting alternate beliefs or assumptions based on the client’s image. This is generally a first step in restructuring, as it is a gentle introduction to the idea of changing what may be deeply or even unconsciously held beliefs.

– Directed Dialogue

In directed dialogue, the therapist instructs the client to take on the role of one of the objects or people from the imagery and deliver specified lines in that role. The client may direct their speech to another object or person in the imagery or simply make statements to no one in particular. This technique can help the client consider the possibility of new beliefs and begin to modulate their own assumptions.

The client may direct their speech to another object or person in the imagery or simply make statements to no one in particular. This technique can help the client consider the possibility of new beliefs and begin to modulate their own assumptions.

– Prompted Dialogue

This technique is not as direct as the previous technique, but it can be just as powerful. Instead of telling the client exactly what to say in their role from the image, the therapist will direct them to come up with their own words to capture a specific idea.

– Directed Transformation

This technique also has the potential to be very powerful. In directed transformation, the therapist will direct the client to make a change to the image. The change may be to direct one of the individuals in the image to take a new action or to edit, enhance, or erase an object from the image.

– Prompted Transformation

Like prompted dialogue, this technique gives the client a bit more freedom to make their own changes to the image. Instead of directing the client in exactly how to change the image, the therapist will encourage the client to think of a way to change the image that will further a goal or help it become more positive (Edwards, 1989).

Instead of directing the client in exactly how to change the image, the therapist will encourage the client to think of a way to change the image that will further a goal or help it become more positive (Edwards, 1989).

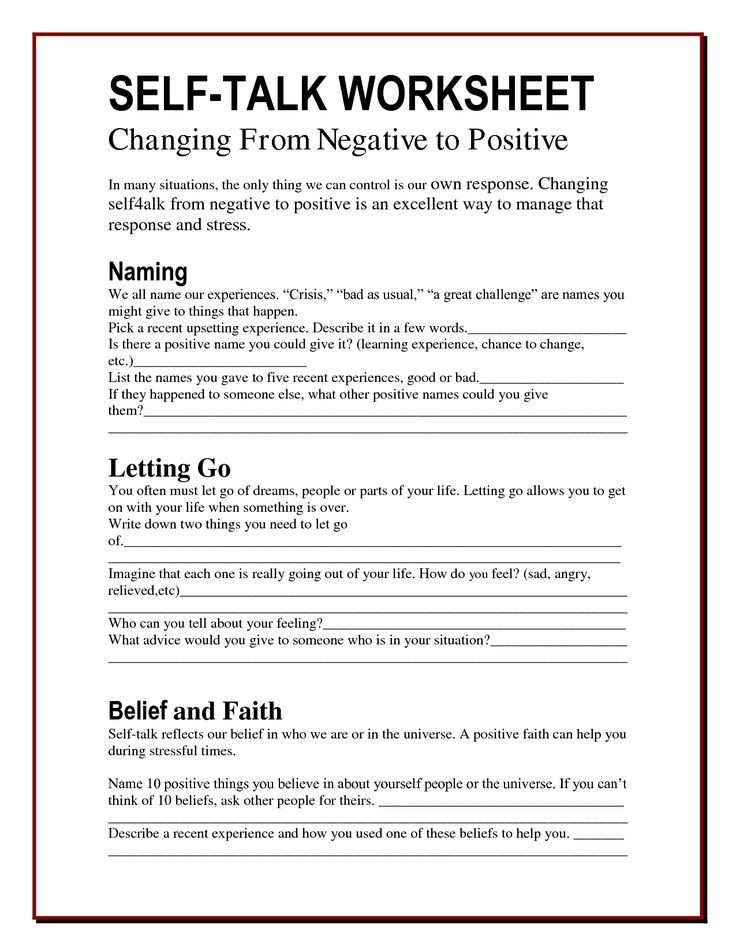

Thought Records

Keeping thought records is an excellent way to help you or your client become aware of any cognitive distortions that went previously unnoticed or unquestioned, which is the necessary first step to restructuring them (Myles & Shafran, 2015). There are several different ways to structure a thought record, but the main idea is to note what recurrent thoughts are coming to mind and the situations in which they come up.

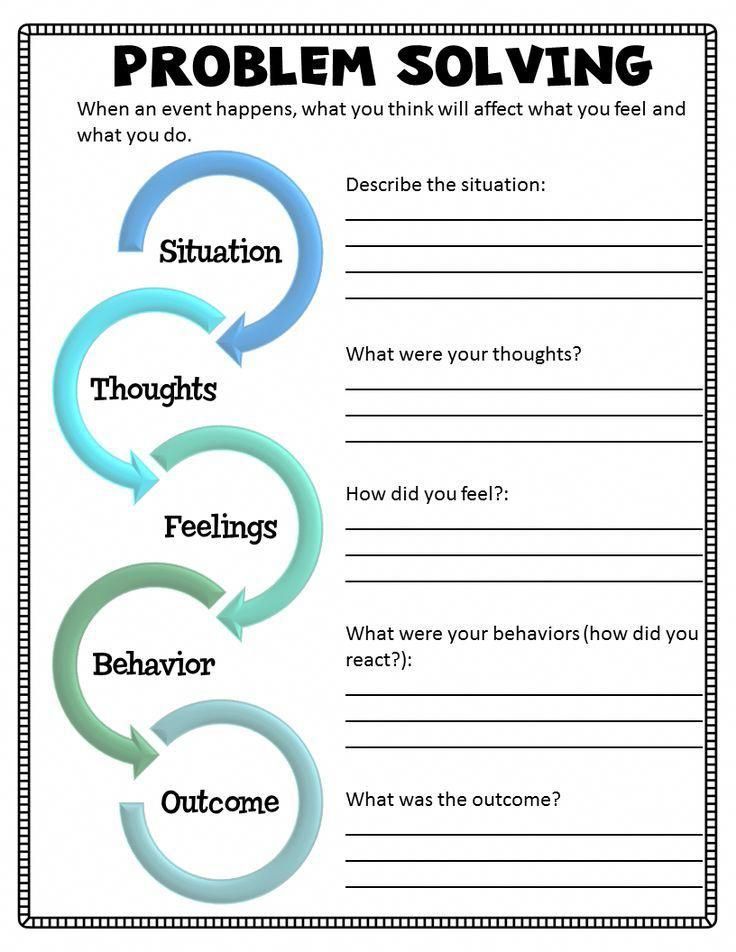

A popular thought record (described in more detail later) instructs you to record the situation, thoughts, emotions, behaviors, and alternate thought.

As an example, you may fill this out with the following descriptions if you are having trouble being alone with depressive symptoms:

- Situation: Everyone’s busy, so I’m spending an evening alone with no plans.

- Thoughts: No one wants to hang out with me. I’m just wasting my life, sitting here alone.

- Emotions: Depressed.

- Behaviors: Stayed home all night and did nothing. Just sat around having bad thoughts.

- Alternate Thought: I’m alone tonight, but everyone is alone from time to time. I can do whatever I want!

Alternatively, if you are struggling with procrastination, you might fill out the thought record as follows:

- Situation: A difficult assignment is due at school.

- Thoughts: This is so much work. I’m horrible at this stuff. I don’t think I can do it.

- Emotions: Anxious.

- Behaviors: Avoided the assignment until the last minute. Had to rush my work.

- Alternate Thought: This is a difficult assignment, and it’ll take a lot of work. But I know I can do it if I break it into small pieces.

Writing this information down will give you or your client a way to consider what they may not have noticed before, and find patterns in their thinking that can point to specific distortions in their cognition.

In the next section, we’ll go over one such worksheet that can be used to record potentially distorted thoughts.

Decatastrophizing or “What If?” Technique

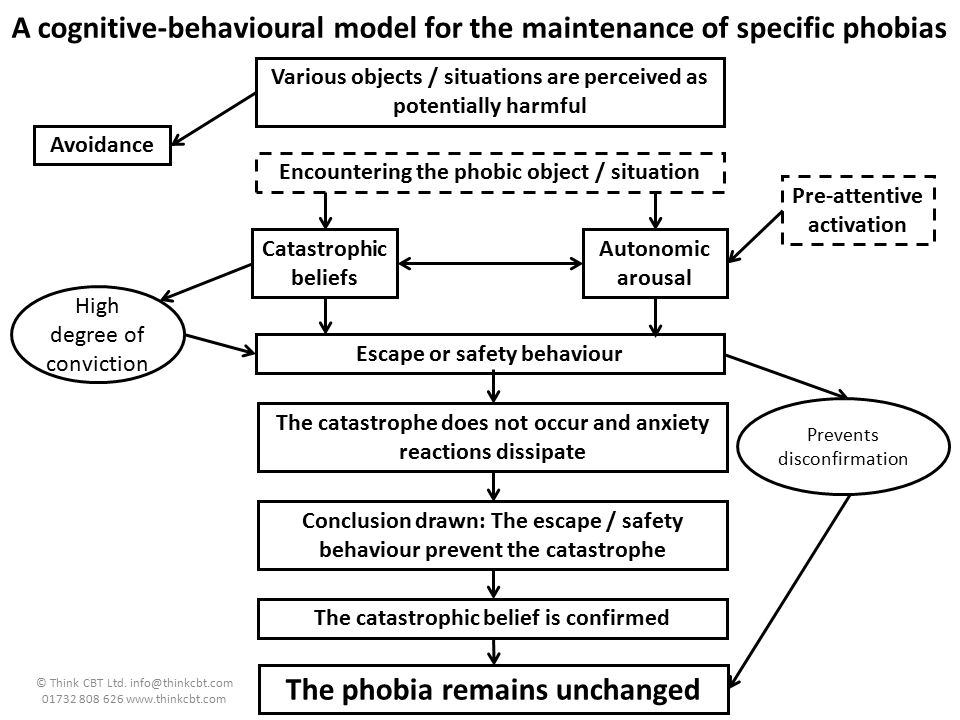

This technique is basically asking “what’s the worst that can happen?” and following a scenario logically through to completion (Dattilio & Freeman, 1992). We often suffer from assumptions or anxieties about the worst possible outcome that could happen, even if that outcome is (a) not very likely, and (b) not going to ruin our lives even if it does!

Decatastrophizing or asking yourself “what if?” will help you or your client determine what is likely to happen, reduce irrational or unreasonable anxiety, and see that even the worst-case scenario is manageable.

A worksheet covering this technique will also be included below.

5 Cognitive Restructuring Worksheets (PDF)

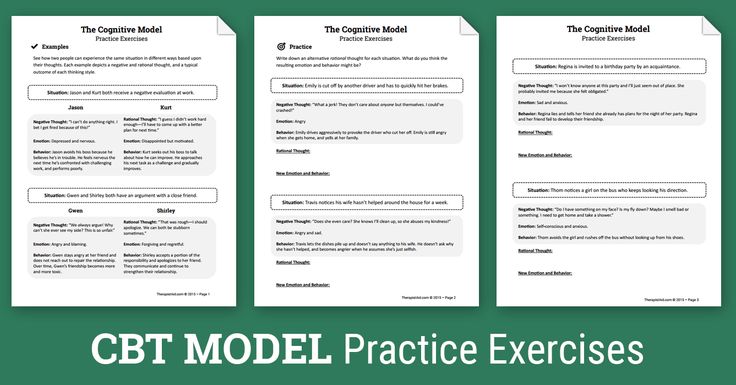

If you’re hoping for some hands-on tools to help you with cognitive restructuring, you’ve come to the right place! A few of the best worksheets and handouts for cognitive restructuring exercises are described below.

Thought Record

This simple worksheet is very easy to use, but it can be extremely helpful for enhancing your awareness and identifying potentially damaging thoughts.

There are six columns in this thought record, with space for up to five separate instances.

In the second column, the user is instructed to describe the situation. This should include the five “W”s and one “H” (i.e., who, what, where, when, why, how), if applicable. Write down everything you can think of that contributed to the environment and to encouraging or promoting the thought that follows.

Write down this thought in the third column. It should be a thought that you identified as potentially harmful, illogical, or outright false. Be specific and write out the whole thought.

In the next column, think about the emotions that accompanied this thought. How did you feel when this thought popped up? What emotions did it seem to bring with it? What emotions did it cause? Anger, shame, sadness, guilt? Write down whatever emotions it engendered.

Use the fifth column to record an alternate thought, especially if the original thought is one that you find unenjoyable or unhelpful. The alternate thought should be something that you find plausible, but that is more positive and realistic than the original thought.

In the last column, note the outcome of this exercise.

Use this Thought Record Worksheet as much as needed, whether that is once every couple of days when a problematic thought pops up, or several times a day when a recurring thought returns to plague you. Keeping a log will help you identify patterns and discover the triggers and potential fixes for the negative, automatic thoughts you are suffering from.

ABC Belief Monitoring

Similar to the Thought Record worksheet, this worksheet is a great way to help you or your client identify the link between situations, thoughts and beliefs, and the feelings and actions that follow.

Sometimes it is difficult for us to connect the triggers of our thoughts and beliefs with the outcomes of those thoughts and beliefs. Use this worksheet to help you or your clients discover these connections.

Use this worksheet to help you or your clients discover these connections.

In the first portion of the worksheet, you will identify the antecedents or triggers (the “A” in ABC) of the belief or thought. Describe the situation as best you can.

In the second section, identify the belief or thought (the “B” in ABC) that you had about the situation. Make sure to note all thoughts or beliefs that arose if you had more than one. Be specific about them. After you have identified the thoughts and beliefs, rate how true you find them to be on a scale from 0% (not true at all) to 100% (absolutely true). Consider each thought or belief, and take some time to assign them an accurate rating.

In the third and final section, list the consequences (the “C” in ABC) of the thought or belief. Describe how you felt when this situation occurred, what you did in response, and how others reacted (if applicable). Do your best not to shy away from the truth, even if it’s difficult to admit how you responded to the situation or acknowledge how others reacted.

Use this ABC Functional Analysis worksheet to keep tabs on any automatic beliefs or thoughts that tend to pop up for you, especially in times of stress or situations that don’t go your way. The first step to restructuring harmful or problematic beliefs is identifying them!

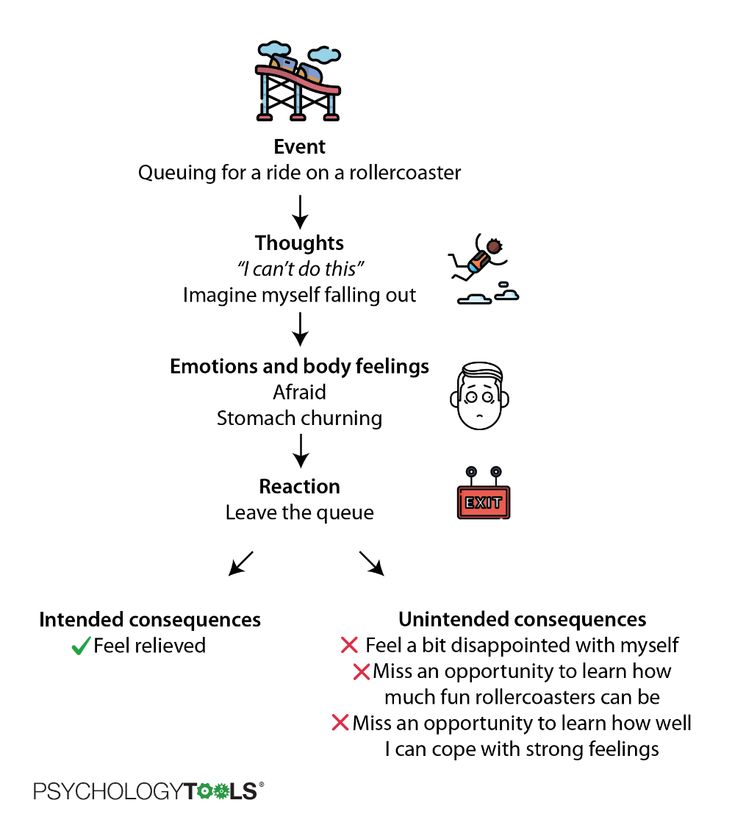

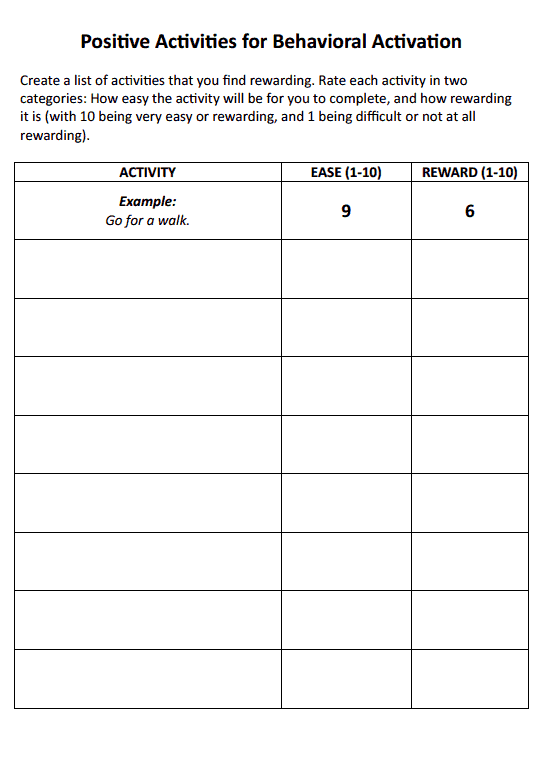

Behavioral Experiment

This worksheet is an excellent way to practice several helpful restructuring techniques and methods of reframing. It also allows you to use your imagination and think about how your current habits and behaviors could bring about future outcomes, whether positive or negative.

In the first section, labeled “Original Belief,” write down something you believe to be true. It should be related to something meaningful to you, and it should be tied to a potential cognitive distortion. Describe what you expect to happen, and how you would know if your belief came true. Next, rate how strongly you believe it will actually come true on a scale from 0% (not strong at all) to 100% (extremely strong).

In the next section, you will do a little experimenting. Think of an experiment that could test this prediction you have, and note the situation that would need to unfold (when, where, who, etc.). Identify which of your safety behaviors, or behaviors you use to protect yourself from anxiety, sadness, or disappointment, would need to be dropped to conduct the experiment.

Write this in the next circle if there is an alternate belief you may need to adopt. Again, rate in on a scale from 0% (not strong at all) to 100% (extremely strong). Note how you would know if your prediction came true or not.

The next step is the biggest one – go out and conduct the experiment.

Once you have completed the experiment, come back to the worksheet and answer the rest of the questions.

The section following the experiment covers the outcome of the experiment. Describe what happened, and don’t skimp on details! Once you have penned a good description of the outcome, determine whether your prediction was accurate.

Write down what you learned from your experiment, and determine how likely it is that your original belief will come true in the future. Finally, rate how strongly you agree with your original belief now that you have completed your experiment and examined the results.

The beauty of this worksheet is that it can be used for a wide variety of beliefs, predictions and behaviors, from big to small, positive to negative, meaningful to trivial, and everything in between.

Completing these Behavioral Experiments will help you challenge your assumptions about how things work, as well as your beliefs about how things should work. Use it as often as you like to keep track of any potentially damaging distortions and maintain awareness about your deeply held beliefs.

Positive Belief Record

This worksheet offers a surprisingly simple and straightforward, yet evidence-based method of challenging potentially harmful or inaccurate beliefs you may hold.

To dive into this worksheet, direct your attention to the top of the sheet. You will find two clouds – one where you can record the belief you would like to modify or replace, and a second space where you can come up with a new, more positive belief to replace it.

You will find two clouds – one where you can record the belief you would like to modify or replace, and a second space where you can come up with a new, more positive belief to replace it.

Underneath the two beliefs is a section where you can record some evidence for the new belief or against the current belief. This evidence can provide support for the new belief, call the current belief into question, or do both at once. It should be fairly easy to find this kind of evidence, especially if the current belief is one that you have identified as a belief that is likely to be inaccurate or illogical.

There is enough space on the worksheet to come up with ten pieces of evidence that support the new belief or cast doubt upon the current belief, but feel free to use another sheet of paper if you need more room! This evidence can include experiences you have had, something someone else has said to you, or anything else you can think of that supports the new belief or sheds doubt on the old belief.

Use this Logging Positive Beliefs worksheet whenever you identify a thought or belief that you realize is distorted, inaccurate, or biased. It will help you come up with ways to combat it and replace it with a new, more positive, more realistic thought or belief.

Theory A Theory B

However important, real, or pressing our problems seem to us, they are often a different kind of problem than we think. This exercise can help your client see many problems as problems of belief or worry instead of situation or fact.

Take a blank sheet of paper and split it into two columns, labeling them as “Theory A” and “Theory B.”

Under Theory A, describe your problem as one of fact. Under Theory B, describe your problem as one of worry.

First, identify your problem and describe it under Theory A. Finish the sentence prompt “The problem is…” with a description of the problem as you currently understand it.

Next, provide evidence that this problem is real, and that you are interpreting the situation correctly.

Finish up the Theory A column by answering the question: “What do I need to do if Theory A is true?” In other words, determine what you would need to do to solve your problem or, if it is unsolvable, address the issues that come with this problem.

When you have finished with the first column, move on to the second column and Theory B.

Describe the problem again, but this time from the perspective of the problem as one of worrying rather than fact. Consider the idea that the real problem is in fact the belief you have or the worry you carry.

Next, provide evidence for the problem as one of belief or worry instead of fact. Think of any evidence you can find that lends support to this interpretation.

Finally, answer the same question you did at the bottom of the first column: “What do I need to do if Theory B is true?” Consider what you would need to do to address your problem if it is interpreted as a problem of worry rather than fact.

Compare the two columns once you have finished. You will likely find that the second column describes a problem that is much more realistic and manageable, and that your “to-do list” at the bottom is much simpler and more straightforward in the second column.

You will likely find that the second column describes a problem that is much more realistic and manageable, and that your “to-do list” at the bottom is much simpler and more straightforward in the second column.

Use this exercise whenever you want to reframe a problem to make it tamer and more manageable.

What If…?

This last worksheet will help you change your perspective on some of the most common situations you encounter or think about. It is based on the natural human tendency to finish the thought “What if…?” with negative situations or events.

While we often veer toward the negative possibilities, there are usually an equal number of positive possibilities that we simply fail to recognize. The consequence of considering only negative outcomes is clearly not a happier and healthier you – a more balanced perspective will help you to approach life with a more positive and realistic attitude.

The worksheet juxtaposes two columns with two separate ways of looking at the world: one negative, and one positive.

On the left side, the column is labeled “Negative ‘What if…?’”

On the right side, the column is labeled “Positive ‘What if…?’”

As you have probably guessed, your instructions are to fill out the left column with “glass half empty” ways of completing a “What if…?” thought, and to fill out the right column with “glass half full” ways of completing such a thought.

There is plenty of room to write in each column, so do your best to fill them! At the least, you should try to make sure you come up with as many positive sentence completions as negative ones. Negative ones tend to come easier to us, but it’s important to consider the positive possibilities as well.

Once you are done, ask yourself these two questions:

- How does each kind of “What if…?” make me feel?

- Which is more likely than the other?

Consider your answers to these questions for each pair of “What if…?” scenarios. You will likely find that you feel much better thinking about the positive ones than the negative ones. If you are being honest with yourself, you will probably find that the positive outcome is more likely to occur than the negative one.

If you are being honest with yourself, you will probably find that the positive outcome is more likely to occur than the negative one.

Pull out this What If Bias worksheet whenever you or your client is having trouble considering the positive along with the negative. This exercise can help you restructure your thinking to correct distortions like disqualifying the positive, mental filter, catastrophizing, minimizing, and overgeneralization.

Challenging Negative Automatic Thoughts

In this worksheet, the reader will be guided through questions challenging negative automatic thoughts (or cognitive distortions).

The questions are based on strategies which include:

- Examining the evidence for and against

- Exploring the idiosyncratic meanings of these thoughts

- Exposing the bias and distortion in these thoughts

- Expanding one’s perspective

- Experimenting, both behaviorally and cognitively

Here are some of the questions:

- What facts support this thought? What existing evidence contradicts it?

- What would the worst possible outcome be, if this thought were true?

- Am I using a past experience to overgeneralize?

Use these questions to guide your thinking about the evidence for negative automatic thoughts, the implications if they are correct (and if they are incorrect), and how they should be modified, restructured, or replaced.

A Take-Home Message

In this piece, we covered the topic of cognitive restructuring. We defined cognitive restructuring (or cognitive reframing), identified some of the most common distortions that can be addressed through cognitive restructuring, covered several different techniques for modifying or replacing these distortions, and provided worksheets and handouts that can help you or your client on this journey to more positive and effective cognition.

I hope you come away from this piece with a new understanding of this valuable CBT tool, and an interest in learning more about the fascinating way that our minds work.

Have you tried any of these techniques, either as a therapist or as a client? How did they work for you? Are there any techniques you found effective that were not included here? Leave us a comment and let us know your thoughts on the subject!

Thanks for reading!

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. For more information, don’t forget to download our 3 Positive CBT Exercises for free.

- Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and emotional disorders. New York, NY: International Universities Press.

- Clark, D. A. (2013). Cognitive restructuring. In S. G. Hoffman, D. J. A. Dozois, W. Rief, & J. Smits (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of cognitive behavioral therapy (pp. 1-22). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Dattilio, F. M., & Freeman, A. (1992). Introduction to cognitive therapy. In A. Freeman & F. M. Dattilio (Eds.), Comprehensive casebook of cognitive therapy (pp. 3-11). Boston, MA: Springer.

- Edwards, D. (1989). Cognitive restructuring through guided imagery: Lessons from Gestalt Therapy. In A. Freeman, K. M. Simon, L. E. Beutler, & H. Akrowitz (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of cognitive therapy. Boston, MA: Springer.

- Mills, H., Reiss, N., & Dombeck, M. (2008). Cognitive restructuring. Mental Help Net. Retrieved from https://www.mentalhelp.net/articles/cognitive-restructuring-info/

- Myles, P.

, & Shafran, R. (2015). The CBT Handbook: A comprehensive guide to using Cognitive Behavioural Therapy to overcome depression, anxiety and anger. London, UK: Hachette.

, & Shafran, R. (2015). The CBT Handbook: A comprehensive guide to using Cognitive Behavioural Therapy to overcome depression, anxiety and anger. London, UK: Hachette. - Yurica, C. L., & DiTomasso, R. A. (2005). Cognitive distortions. In S. Felgoise, A. M. Nezu, C. M. Nezu, & M. A. Reinecke (Eds.), Encyclopedia of cognitive behavior therapy (pp. 117-122). Springer, Boston, MA.

What is a Functional Analysis of Behavior in CBT?

Behaviors do not occur in isolation.

In order to change a behavior, we need to understand why we act that way in the first place.

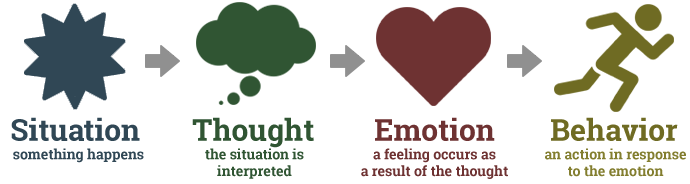

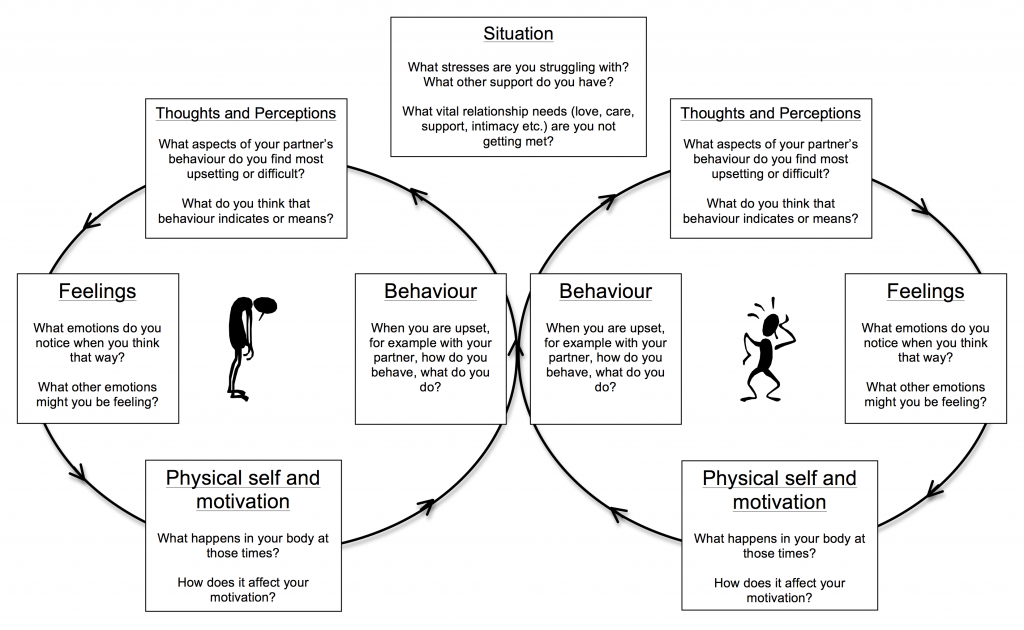

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a therapeutic modality that considers the triggers (antecedents), thoughts, actions, and consequences that make up a behavior (Bakker, 2008).

It is a complex chain, and there is no single reason that a behavior occurs. Functional analysis helps break down that complexity.

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our three Positive CBT Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will provide you with detailed insight into Positive CBT and give you the tools to apply it in your therapy or coaching.

These science-based exercises will provide you with detailed insight into Positive CBT and give you the tools to apply it in your therapy or coaching.

This Article Contains:

- What Is a Functional Analysis of Behavior?

- The Theory Behind FA

- Applications of FA

- How to Perform a Functional Analysis

- 2 Real-Life Examples

- 4 Worksheets for Your CBT Sessions

- 4 Books on the Topic

- A Take-Home Message

- References

What Is a Functional Analysis of Behavior?

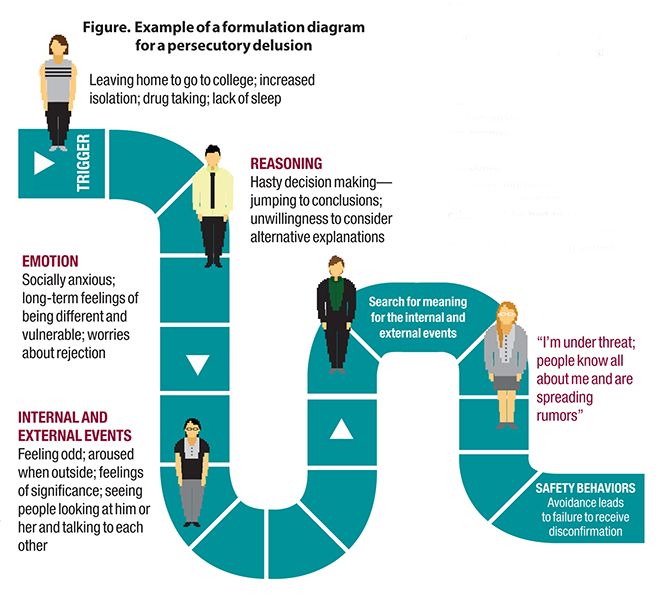

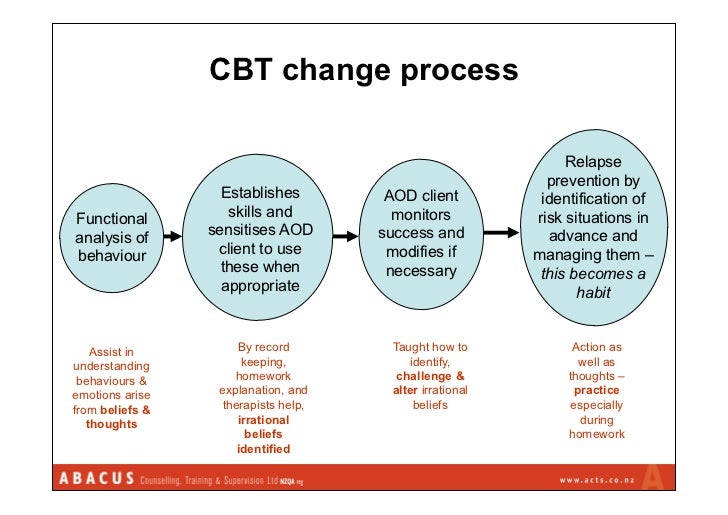

A functional analysis (FA) of behavior is an essential step in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy when the therapist and client break down the behavior chain into its respective parts (Bakker, 2008).

They perform this analysis so that they may better understand why a desirable behavior works and why undesirable behavior happens. Once they determine why and how a behavior is created, the therapist and client can then change parts of the behavior chain to achieve a different outcome (O’Donohue & Fisher, 2009).

When a client has a maladaptive behavior, it may be difficult for the clinician to know where to begin. There are many factors at play in behavior, such as developmental level, past learning (experiences), social influences, and environmental influences.

A functional analysis allows a client and clinician to target which consequences they want to change and then work backward to identify the rest of the behavioral chain to determine the causes of the behavior. A functional analysis is, essentially, breaking down a whole into parts and targeting the part that needs to change in order to end a maladaptive behavior (Ferster, n.d.).

A functional analysis of behavior is an experimental way to assess the cause of a particular behavior. Three types of assessments can be done in a functional assessment of behavior (Yoman, 2008):

- Indirect (i.e., self-reporting)

- Observational

- Experimental (analysis)

The Theory Behind FA

In CBT, the reasons behind the behaviors are called “functions” (O’Donohue & Fisher, 2009).

Functions explain how any given behavior works in its environment.

A functional analysis is a step in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy that is used to identify problematic thinking and where change can best begin.

At its core, it is a breakdown of operant and respondent conditioning to determine the relationship between the stimuli and responses (Yoman, 2008). It determines the reason and purpose for a behavior and often involves the direct manipulation of one of the variables to change the target behavior.

A functional analysis of behavior is particularly useful with young children who are nonverbal or unable to self-report on their behaviors. It is also useful with adults who are unable to find insight into the cause of their behaviors.

Since it does not rely on self-reports, but on direct observation, the client and clinician can objectively analyze the behavior and develop a quick intervention plan.

Generally, the most common causes of problem behaviors are:

- Access to social attention

- Access to items or activities

- Escape/Avoidance of unpleasant stimuli or task

- Sensory stimulation

Applications of FA

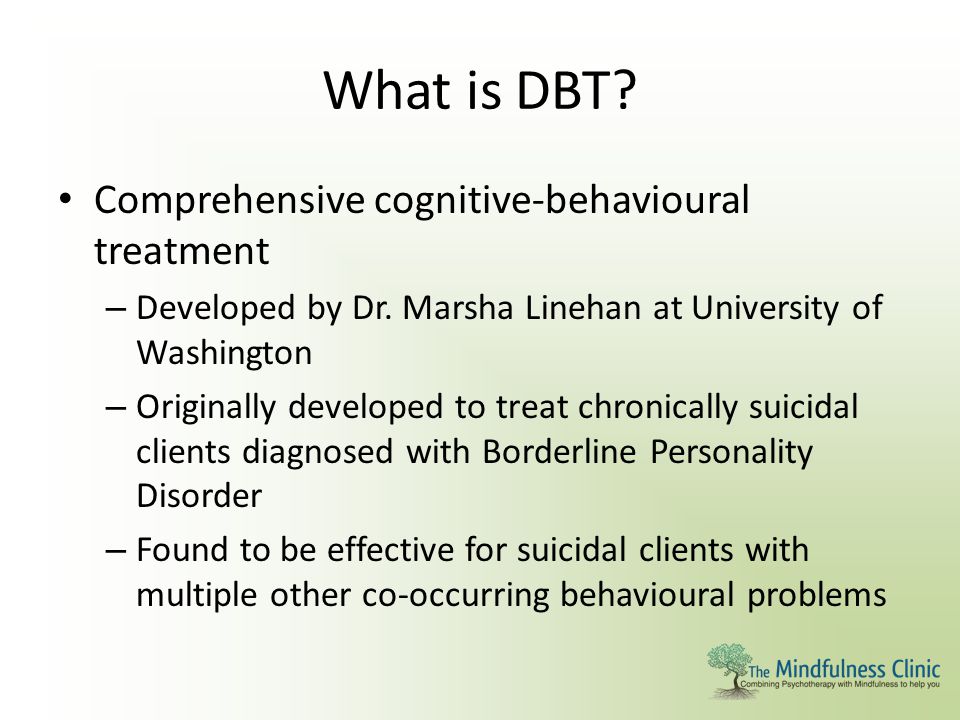

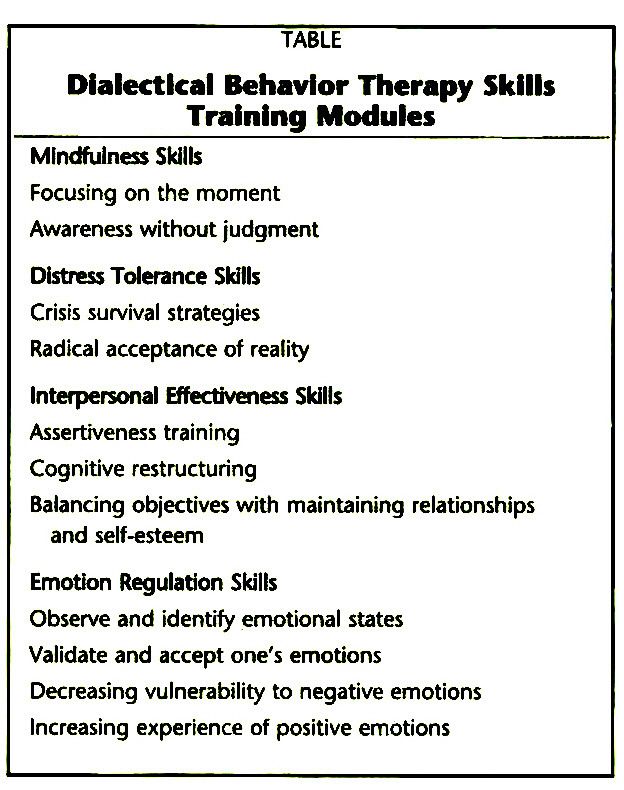

A functional analysis of behavior is most often used as a part of Behavior Therapy, be that Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) or Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT).

CBT and DBT are skill-based modalities and may provide a client with fast relief from maladaptive behaviors without extensive psychoanalysis, which is why a functional analysis of behavior is often used when working with nonverbal or autistic children, since the primary method of analysis is observation instead of subjective self-reporting (Kohlenberg, Kanter, Bolling, Parker, & Tsai, 2002).

When a client notices that they are “in a rut” or have developed a bad habit or maladaptive way of coping with certain situations, functional analysis can determine the reasons why that behavior exists and help to quickly create a plan to alter the behavior into something more desirable.

Clients who come into your office complaining about the same bad habits they have every week, but feel powerless to stop repeating the same mistakes, would benefit from a functional analysis of behavior.

When behavior is partialized, the client gains a more in-depth understanding of not only why the behavior is occurring, but also what factors maintain it (Kohlenberg et al. , 2002). When the root cause of the behavior is changed, then the outcome usually changes.

, 2002). When the root cause of the behavior is changed, then the outcome usually changes.

This is an excellent tool for clients who are looking for quick changes that can have lasting effects.

How to Perform a Functional Analysis

To perform a functional analysis, the clinician should first start with an assessment to determine what habits and behaviors are causing feelings of distress in the client (Yoman, 2008).

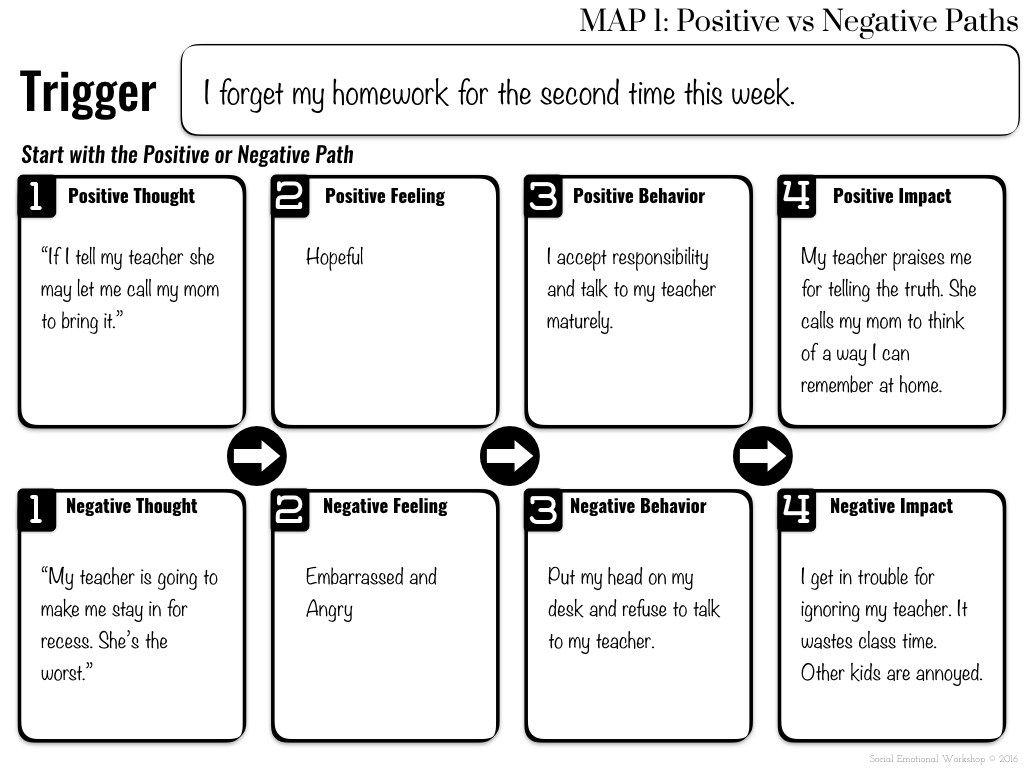

Often a functional analysis determines the ABCs of an event: the antecedent, the behavior, and the consequence (Bakker, 2008). The functional analysis is conducted when behaviors are altered to determine their strength in the behavioral chain.

The steps are:

- The antecedent: The clinician examines the client’s behaviors: how frequently a behavior is displayed, under what environmental contexts the behavior occurs, and other people that may be involved. The clinician is trying to determine the triggers that cause that particular behavior chain.

These are the events that occur directly before the thought, behavior, and consequence.

These are the events that occur directly before the thought, behavior, and consequence. - The thought: Next, the clinician may ask the client to identify a corresponding thought that happens whenever that trigger occurs. If the client is nonverbal or unable to identify a thought, this step may be skipped. These thoughts are often negative or self-deprecating.

- The behavior: Then, the clinician and client identify the behavior that comes directly as a result of that trigger and thought.

- The consequence: Finally, the clinician and client determine the consequence of the behavior. What happens as a result of this behavior chain? When the consequence is determined, and the analysis is looked at as a whole, it is easier to decide which parts of the chain are perpetuating the maladaptive behavior. When that part of the chain is changed, the rest of the behavioral chain should change in response.

Finally, the clinician and client determine which part of the behavior chain must be targeted to make a lasting change. They decide upon an intervention to alter the behavior and, thus, the outcome. The new behavior chain is tested and changed if needed, until the desired consequence is achieved.

They decide upon an intervention to alter the behavior and, thus, the outcome. The new behavior chain is tested and changed if needed, until the desired consequence is achieved.

The basis of a functional analysis is experimenting with the behavior chain and making alterations until the results improve.

2 Real-Life Examples

To give you a better understanding of how FA applies in real-life, look at the examples below.

Breaking your fast

You skipped breakfast, and now you are hungry (antecedent). You go to the staff room where there are free donuts. You are so hungry that you eat three donuts (behavior). As a result, you get a stomachache from the donuts (consequence).

Since you hate feeling sick, you talk with your therapist and decide to change the behavior chain. Your therapist suggests that you eat breakfast every day. Now, you eat oatmeal before work (antecedent). When you see the donuts in the room, you are no longer hungry. You ignore the donuts (behavior), and you feel great for the rest of the day (consequence).

Acting out

A student continually misbehaves in class and gets sent to the principal’s office. You decide to analyze the student’s behavior. You observe that the student’s “bad” behavior occurs every day at a certain time.

You observe that the student acts out as soon as the teacher announces that it is reading time. The student then throws a tantrum and hurls books across the room. The teacher sends the student to the principal’s office for acting out.

In this case, the antecedent is when the teacher announces that it is reading time. The student may not identify the corresponding thought, but if they can verbalize it, they may think something like, “I’m embarrassed because I can’t read well. I don’t want the others to think that I am stupid.”

The behavior occurs as a result of the antecedent and corresponding thought. The tantrum allows the child to escape reading time. Escaping from the room reinforces the child’s behavior because they are able to avoid a negative situation.

Therefore, the child may begin to act out during other times as well when embarrassed or frustrated. When the behavior chain is altered, and no escape is allowed, the child will no longer feel the need to act out during reading time.

4 Worksheets for Your CBT Sessions

The ABC Functional Analysis Worksheet will help you identify the antecedents, behaviors, and consequences. This worksheet will help you break down the behavior chain into parts so that you can identify where you need to make changes.

The Coping Styles Formulation will help you identify thoughts and feelings that may be reinforcing maladaptive coping strategies or preventing you from using more adaptive CBT techniques.

This Case Formulation Worksheet will help you determine how the problem developed in the first place. This worksheet focuses more on internal systems (e.g., thoughts and feelings) that perpetuate and can help alleviate a problem behavior.

The IF-Then Planning worksheet combines traditional CBT with positive psychology to shift the focus of therapy to what is right instead of what is wrong. It helps you recognize wrong reactions to certain situations in advance, and plan alternative and more appropriate reactions.

It helps you recognize wrong reactions to certain situations in advance, and plan alternative and more appropriate reactions.

4 Books on the Topic

A review of the functional analysis of behavior is included in many books on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, educational psychology, Dialectical Behavior Therapy, and applied behavior analysis.

These are some books that you may find useful when conducting a functional analysis of a client’s behavior.

1. Functional Analysis in Clinical Treatment – Peter SturmeyAlthough functional analysis was initially designed for an educational setting, this book describes the use of FA for a variety of psychological issues.

The book explains the framework of FA in detail, how to use FA in treatment planning, and how to implement FA in conjunction with Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.

It also goes through the various cases in which FA can be used, including with ADHD, autism, and even in occupational training.

Available on Amazon.

2. Functional Analysis: A Practitioner’s Guide to Implementation and Training – James T. Chok, Jill M. Harper, Mary Jane Weiss, Frank L. Bird, and James K. Luiselli

This book explains several of the most commonly used methodologies in functional analysis.

It is mostly geared toward the occupational training of staff in schools where the student population has been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. However, the training can help any clinician learn the basics of FA, and the worksheets can be used in direct application with clients.

Available on Amazon.

3. How to Think Like a Behavior Analyst: Understanding the Science That Can Change Your Life – Jon Bailey and Mary Burch

A beginner’s guide to behavior analysis, this book presents the science of functional analysis in a fun and entertaining way.

It includes practical information on the direct application of functional behavior analysis in a therapeutic, educational, or community setting.

Available on Amazon.

4. Handbook of Applied Behavior Analysis, Second Edition – Wayne W. Fisher, Cathleen C. Piazza, and Henry S. Roane

This book provides clear information on the theory, research, and science of behavioral analysis, including functional analysis.

It also addresses professional and ethical issues in behavior analysis. This book is geared more toward seasoned professionals who want to expand into the field of behavior analysis.

Available on Amazon.

A Take-Home Message

It is never easy to change a behavior. But when the cause of a behavior is understood and the parts that maintain that behavior are identified, it becomes easier to change the outcome. One change in the behavior chain should cause noticeable and lasting changes for a client.

Sometimes we miss the trees when looking at the forest, and a functional analysis of behavior reminds us that a forest is made up of trees. When we break down the complex into simple parts, we can implement changes more efficiently and with less stress.

As a client begins to implement small changes, these develop into bigger habits and, ultimately, more adaptive coping strategies.

A functional analysis of behavior is not a way to identify the developmental and psychological causes for why a behavior started in the first place. Rather, it is a way to quickly identify problem behavior and provide fast relief for your client.

The hope is that with many small changes of behavior, your client will develop more adaptive coping strategies that last a lifetime.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. For more information, don’t forget to download our three Positive CBT Exercises for free.

- Bailey, J., & Burch, M. (2006). How to think like a behavior analyst: Understanding the science that can change your life. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Bakker, G. (2008). Practical CBT: Using functional analysis, problem-maintaining-circles, and standardised homework. Bowen Hills, Queensland, AU: Australian Academic Press.

- Chok, J. T., Harper, J. M., Weiss, M. J., Bird, F. L., & Luiselli, J. K. (2019). Functional analysis: A practitioner’s guide to implementation and training (Critical specialties in treating autism and other behavioral challenges). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Ferster, C. (n.d.). A functional analysis of depression. Retrieved from http://www.personal.kent.edu/~dfresco/CBT_Readings/Ferster_1973.pdf

- Fisher, W. W., Piazza, C. C., & Roane, H. S. (Eds.) (2021). Handbook of applied behavior analysis (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Kohlenberg, R. J., Kanter, J. W., Bolling, M. Y., Parker, C. R., & Tsai, M. (2002). Enhancing cognitive therapy for depression with functional analytic psychotherapy: Treatment guidelines and empirical findings. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 9(3), 213–229.

- O’Donohue, W. T., & Fisher, J. E. (Eds.). (2009). General principles and empirically supported techniques of cognitive behavior therapy.

Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. - Sturmey, P. (2020). Functional analysis in clinical treatment (Practical resources for the mental health professional) (2nd ed.). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Yoman, J. (2008). A primer on functional analysis. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 15(3), 325–340.

basic principles and patterns of use

Socratic Dialogue: Basic Principles and Models of Use

Start with the question “Why are you interested in this article?” perhaps it would be a good idea (or maybe even the start of a Socratic dialogue!). And I have an idea how you could answer this question, because in the process of writing the article, I came across three facts:

- Despite the universality of the Socratic dialogue as a tool, very little is written about it and even less research is being done;

- Psychologists of all kinds and all who work with people use Socratic dialogue, but most often intuitively and unconsciously;

- Some questions can be more effective than others, and the use of Socratic dialogue helps to increase this efficiency.

In this article, I will try to present the basic principles of Socratic dialogue, a typology of Socratic questions, and exemplary models for their use in CBT.

“Mm... Does this have anything to do with Socrates?”

Yes, Socrates actively used questions in the discussion in order to reveal the knowledge of his students, or, on the contrary, the lack of this knowledge. It was assumed that truth and knowledge were not given in a ready-made form, but were a problem, the resolution of which took place in the process of searching. Modern psychotherapy actively uses the idea of Socrates that a person already has the necessary knowledge to develop a more adaptive understanding of the problem, and everything that the psychotherapist does helps to reorganize this knowledge.

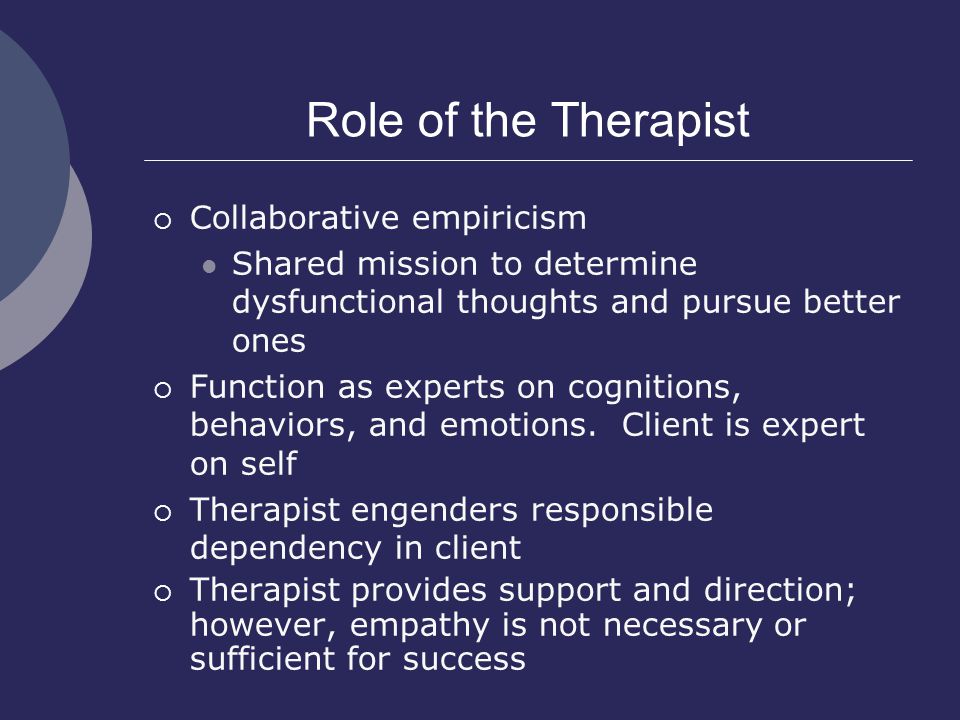

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) uses Socratic Dialogue in a “directed discovery” manner. This means that the therapist does not have any ready-made answer to which he purposefully leads the client - but there is a sincere curiosity and willingness to help the client formulate this "discovery" on his own.

This may be news to those who believe that "cognitivists change a person's negative thinking into positive thinking." In fact, a competent CBT therapist sets himself the task of teach the client to independently assess their beliefs, emotions, behavior and change them in a more adaptive way . Moreover, by asking Socratic questions, we accept the fact that there is only one expert in the client's life experience - this is the client himself, and by listening carefully to his answers, we can not only teach him something, but also learn a lot from him.

What principles guide the Socratic dialogue?

The cognitive-behavioral view of the Socratic dialogue involves relying on the following principles:

1. The client has sufficient knowledge to answer the question. Accordingly, it does not make sense for the therapist to ask a question that goes beyond the knowledge of the client (for example, asking in the first session "How does this emotion relate to your core beliefs?"). Moreover, it is extremely important to take into account the "zone of proximal development": for example, if we want to draw the client's attention to his emotions, the wording of the question should take into account his ability to be aware of them. The question “What emotions are you experiencing right now?” may be prohibitively difficult for a client with a personality disorder. It will be much easier for him to answer the question “Do you feel tension at the moment? How strong?..”

Moreover, it is extremely important to take into account the "zone of proximal development": for example, if we want to draw the client's attention to his emotions, the wording of the question should take into account his ability to be aware of them. The question “What emotions are you experiencing right now?” may be prohibitively difficult for a client with a personality disorder. It will be much easier for him to answer the question “Do you feel tension at the moment? How strong?..”

2. The therapist directs the client's attention to aspects of the problem that are out of the client's focus. And so it is extremely important that the therapist see them himself, while not insisting on any single interpretation, but opening up for the client different possibilities and points of view on the situation. At the same time, it is important for the therapist to have many different hypotheses regarding the development of events. One of my respected teachers, Elena Samoilovna Slepovich often told us students: “What is your hypothesis when you ask about it? Try to test some hypothesis with each of your questions.

3. Questions move attention away from a specific example and into broader, more abstract conclusions. This principle is also called the hourglass principle: we move from the abstract to the more concrete, then back to the more abstract. There may be several such movements, as a result of which the entire dialogue can be represented as a “snake” movement. For example:

Client (C): I feel terribly bad... (abstract level).

Therapist (T): What thoughts do you have in this state? (specific level)

K: If I let people treat me like that, then I'm a jerk. And I myself am to blame for this...

L: In what other situations does this feeling usually arise?

K: When I read about someone's successes on Facebook, when they praise someone in front of me... And when my husband compares me to his mother.

T: What do all these situations have in common? (abstract level)

K: Well, there is a comparison that makes me feel inferior to others.

T: Do you have any idea when you first had this feeling? (specific again)

K: Mm, yes, my mother always compared me to other children, especially since I started school. (pause) I think her constant criticism had a big impact on my self-esteem (abstract).

4. Finally, the client is able to independently formulate an alternative understanding of the problem or an alternative way of coping with it. It is this last principle that carries the main therapeutic function of the Socratic dialogue. By asking questions to explore the problem and expanding the client's awareness zone, we sort of turn the scattered puzzles upside down - and this is a very important stage, without which insight is impossible. At the same time, the client would not contact us if he was able to independently put the puzzles into a single picture. And this is precisely the task in which he needs help most of all.

T: I'm sorry that your mother acted like this... Is the way your husband criticizes you similar to the way your mother behaved?

K: I think so.

T: At the beginning of our dialogue, you said that you yourself are to blame for how terrible you feel. What do you think about it now?

K: Hmm, well, maybe I underestimated the role of my mom and husband in this. Their criticism really affects me.

How do some Socratic questions differ from others?

Below in the table I have tried to collect and summarize the different types of Socratic questions according to their functions. The types of questions are roughly in chronological order of movement in therapy, but it is important to remember that questions are just dishes on the smorgasbord of the therapist's tools, and he can choose at his own discretion.

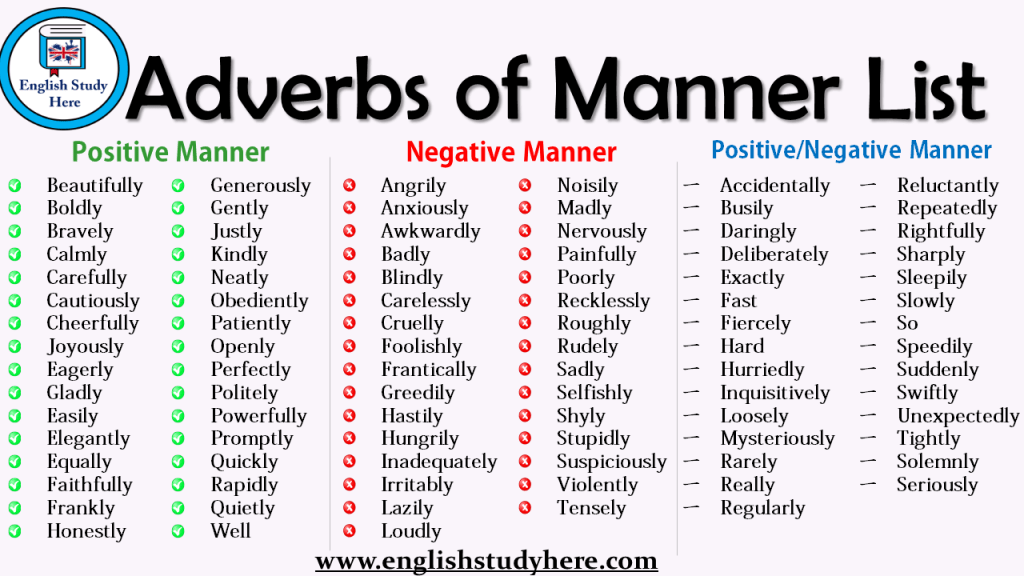

| Question type and function | Sample questions | Applications |

| 1. Study: refinement and clarification | “I'm not sure I understood you correctly. Are you saying that she did it because...” “Could you give me an example...”, “Could you expand on this”, “Is it true that you see it as...” , “What do these events have in common / how are they different?”, “When was the last time something like this happened?”, “How often does this happen?”, “Who else do you feel the same way with?” Are you saying that she did it because...” “Could you give me an example...”, “Could you expand on this”, “Is it true that you see it as...” , “What do these events have in common / how are they different?”, “When was the last time something like this happened?”, “How often does this happen?”, “Who else do you feel the same way with?” | At the beginning of therapy, when exploring a new situation/behavior pattern, when establishing a therapeutic relationship |

| “What makes you think this way?”, “Did something happen that led you to this conclusion?”, “What is the benefit/loss of thinking this way?”, “When did this thought first occur? What followed?”, “If you consider all the reasons you have named, how much influence on the situation can you attribute to each of them?” | At any stage when it is important to show cause and effect relationships and raise the awareness of the client (especially at the beginning of therapy) | |

3. Checking problematic beliefs Checking problematic beliefs | “What facts show that you are not succeeding?”, “What facts say otherwise?”, “Is this always the case?”, “Were there exceptions when it happened otherwise?”, “What was your experience to the contrary?”, “Is there anything in your experience” that contradicts this thought?”, “How would your friend look at this situation?” | When the client is ready to consider and try to change problematic beliefs (in CBT, during restructuring) |

| 4. Positive and negative effects | “What positive consequences in the short / long term do you see?”, “How useful is it to hold this belief?”, “If you believe this can affect your behavior / motivation?”, “What can help you avoid these consequences?” | Same as above |

| 5. Alternative understanding of the situation | “What else could be the reason for this?”, “What could be instead?”, “Who could disagree with this and why?”, “What would your friend say about this?”, “Are there any facts or possibilities that you have not considered enough?”, “If you were a detective, how would you collect evidence for and against?”, “How would you have looked at this before the depression?”, “What would you say to yourself if You are 75 years old”, “Now that you have seen the bigger picture, how could you change your initial perception of the problem?” | At the stage of forming new views on the situation |

6. Solution questions Solution questions | “What exactly can happen, what are you afraid of?”, “What exactly could you do to...”, “What would your friend do in your place?”, “What prevents you from doing this?”, “ Which of these could you do in spite of these obstacles?”, “How can you check if this is true?”, “How can this information be related to solving the problem?”, “How can you evaluate that [the new way action] affected [desired outcome]?” | In cases where the request is related to a change in behavior and a specific solution to the problem |

| 7. Down boom – so what? | “What does this say about you?”, “If so, what does it mean to you?”, “What is the most unpleasant thing about this?”, “Maybe this question sounds stupid, but what's wrong with such a view of things?” , “What would others think of you in this situation?”, “If this is really true, then what?..” | When examining the client's beliefs about himself (in CBT, core beliefs) |

How is Socratic dialogue used in CBT?

Socratic questions are like building blocks from which you can assemble different dialogue models. I would like to give three approximate models that I use most often in my work.

I would like to give three approximate models that I use most often in my work.

| Model of alternative understanding of the problem | Problem solving model | Behavioral experiment model | |

| What the is for | Help to see the range of possibilities that are outside the actual field of view | Explore different possibilities and ways to solve the problem | Allows you to check the validity of a new vision of the problem and a way to solve it |

| Types of eligible questions | Facts for and against, “alternative causes”, “negative and positive consequences” | Questions for solution | Anticipating an alternative situation and finding solutions |

| Examples | “What else could explain your son’s behavior other than the reason you gave?”, “What she said really proves that he is incapable of anything?”, “How useful is it for you to hold such an opinion ?” | “How could your colleague deal with such a problem?”, “Given that avoiding this problem is the main obstacle to solving it, what could help you?”, “How exactly could you prepare for this?” | “What would happen if you stopped controlling it?”, “What thoughts would flash through your head then?”, “What would you feel?”, “What would it mean for you?”, “How can you create a situation in which we could test it?”, “How could you prepare if things go differently?” |

What are the limitations of Socratic dialogue?

Despite its versatility, in certain situations Socratic dialogue is still inferior to other methods of therapeutic intervention. For example:

For example:

- when assessing the risk of suicide when a client comes to us in an acute crisis, directive questions will be more effective (“Have you attempted suicide? When?”, etc.)

- if the client does not have the knowledge and experience to which we could turn, it will be more effective informing or so-called. “psychoeducation ” (for example, if you have experienced panic attacks for the first time and do not know anything about their neurophysiology, it is important to simply tell him about what is happening to him).

- in acute grief reactions it may make more sense to abandon active interventions in favor of open compassion and empathy (simply “be there”, not “treat”).

An experienced therapist gradually masters more and more flexibility in Socratic dialogue, while novice therapists often lack this flexibility. And then there can be such difficulties as:

- “Bulldosing” the client, when the therapist asks difficult questions one by one: “And what does this mean for you? So, what is next? And what's so terrible about that?" It is likely that under such interrogation the client will shut down and may leave therapy altogether, so it is important to remember to prioritize the therapeutic relationship and ask questions gently and gently.

You should be especially careful when using the “arrow down” technique, aimed at revealing the client’s deepest beliefs.

You should be especially careful when using the “arrow down” technique, aimed at revealing the client’s deepest beliefs. - The therapist effectively asks questions, but also "chases" one hypothesis, which makes the client feel pressured and controlled. In this case, it is important to remember that we can never be sure what is best for the client, and give him the opportunity to make his own choice.

- The therapist explores the problem well, but forgets to sum up the intermediate results and ask questions aimed at analysis or synthesis, as a result of which it becomes difficult to form an alternative understanding of the problem, and sometimes make sure that the client and therapist are talking about the same thing.

In conclusion

The Socratic dialogue in psychotherapy is a powerful method, the conscious use of which can significantly deepen and probably speed up the therapeutic process. One of the most important resources of this method is the ability to work with existing knowledge and experience, which gradually allows the client to discover more and more ways to interact with the world and himself. And, as we know, the most valuable discoveries for us are those that we make ourselves.

And, as we know, the most valuable discoveries for us are those that we make ourselves.

Bibliography

- Carey, T. A., Mullan, R. J. (2004) What is Socratic questioning? Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, Vol 41(3), p. 217-226.

- Kennerley, H. (2007). socratic method. OCTC essential guides. Available on www.octc.co.uk

- Overholser, J. C. (1993). "Elements of the Socratic method: II. Inductive reasoning". Psychotherapy 30:75–85.

- Padesky, Ch. A (1993). Socratic Questioning: Changing Minds or Guiding Discovery? Center for Cognitive Therapy, Huntington Beach, California.

- Rutter, J. G., & Friedberg, R. D. (1999). Guidelines for the effective use of Socratic dialogue in cognitive therapy.

- Westbrook, D., Kennerley, H., Kirk, J. (2011) An Introduction to Cognitive Behavior Therapy. - 2nd ed. London: Sage. - p. 147 - 170.

About the author

Book a consultation

- Back

- Forward

Site search

Popular articles

- What are cognitive filters and how do they work?

- Socratic Dialogue: Basic Principles and Models of Use

- Competence and Basic Skills of a Cognitive Behavioral Therapist

- Neurophysiology of anxiety response-1: where does anxiety come from?

- Mindfulness meditation-mindfulness: resistance is useless

Tags

CPT Therapy mass media Mindfulness Anxiety Video Psychology What? Meditation Adaptation Retreat Buddhism exposition Depression

Become a Patron!

Worked with Katerina for several months on my requests, sought out and drove out "cockroaches")). . I recommend!

Ekaterina, thank you for your help, you helped me a lot, you gave me a lot of valuable advice and I have something to think about and work on. Thank you for your participation and for helping me overcome resistance, being very sensitive and patient.

Thank you for your participation and for helping me overcome resistance, being very sensitive and patient.

Ekaterina at one time helped me a lot to sort out my priorities, what was specifically important and useful to me. It helped me overcome some lack of self-confidence, opened up a world for me in which a lot of options for the development of events are possible in addition to what I see. In addition, in addition to remarkable competence in her field, she is just a good person with whom it is pleasant to talk about life's little things outside the context of "psychologist-client", and this is now very valuable.

Thank you for your help, for helping me figure out which way to look. Found the causes of problems and how to solve them. There was a solution strategy, enlightenment in the problem!

I turned to Ekaterina for help in matters of time management, personal efficiency in work and training. Ekaterina helped to carefully understand the problems, find their causes and showed various ways to solve them. I learned to spend my time more carefully, to concentrate on important tasks and not be distracted by useless trifles, to find and correctly use sources of replenishment of energy and strength. Thank you Catherine, it was a pleasure to work with you!

I learned to spend my time more carefully, to concentrate on important tasks and not be distracted by useless trifles, to find and correctly use sources of replenishment of energy and strength. Thank you Catherine, it was a pleasure to work with you!

Very professional psychologist, helped me to look inside myself and choose the right direction. Pleased with tact and indifference to the client. Consultations with Ekaterina brought a positive effect in a short time.

I really appreciate Ekaterina's powers of observation, her professional flair, correctness and great capacity for work! She has a corporate style that combines openness, a desire to help figure everything out ... The “Timekeeping” exercise was especially impressive in the work: I immediately saw where the gap was, where the vacillation was without a goal. After this technique, I threw away the TV and now I continue to actively change my life. In many ways - it is thanks to Catherine.

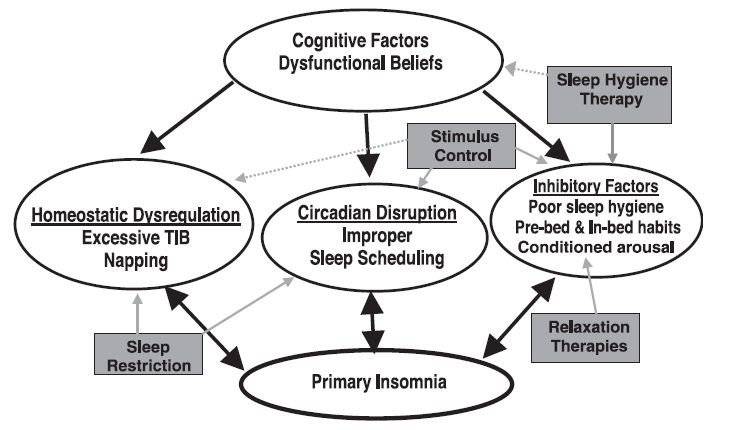

Diagnostics in cognitive behavioral therapy //Psychological newspaper

Mental health professionals are witnessing a crisis in systems for classifying/diagnosing mental disorders, as well as a rebalancing of the influence of biologically centered models applied to mental health and its management.

Revision of the classification and diagnostic models is an inevitable need. We cannot effectively operate only with the mechanical sum of clinical phenomena, turning them into lifeless labels of formal diagnoses that emasculate the complex mechanisms of the genesis and maintenance of dysfunctions and pathologies of the psyche and body.

The current DSM and ICD models have been conceptually criticized many times. And this criticism is largely based on substantial grounds. Modern classifications are more convenient for use by healthcare organizers and insurance companies than by clinicians and practitioners. They are convenient for reporting, but more often create the illusion of understanding disorders than revealing their underlying mechanisms to treat causes rather than consequences, eliminate pathogenesis rather than symptoms. The global mental health community is seeing that the ICD-11 (ICD-11) introduces significant changes from the ICD-10. However, in accordance with the overall strategy, most of the changes are aimed at harmonizing the ICD-11 with DSM-5, rather than creating a new foundation and principles for classification. Noting the imperfection of both systems, which is inevitable in the absence of a real normo- and pathopsychophysiological basis, this is also a desirable step, since diagnostic labels are basically an attempt to form a common global language for describing observed clinical phenomena and their genesis, but, unfortunately, is still obviously insufficient. for practitioners.

Noting the imperfection of both systems, which is inevitable in the absence of a real normo- and pathopsychophysiological basis, this is also a desirable step, since diagnostic labels are basically an attempt to form a common global language for describing observed clinical phenomena and their genesis, but, unfortunately, is still obviously insufficient. for practitioners.

We are still faced with a number of mysteries: what consciousness is, how exactly the leading mental processes function, and how exactly they relate to neuroanatomical structures. The old saying that we are treating the patient and the person, not the diagnosis and the disease, encourages us to see behind the symptom trees a forest and landscapes of at least a biopsychosocial model for describing their system of interconnections. Man is an open complex system included in the supersystems of micro- and macrosociety, biogeonocenosis. This system is much more complex than the labels pasted on it from different sides. How wide are the interconnections of a person in his colossal neural network with 86 billion neurons and many trillions of their connections (100–150, according to various estimates of researchers), just as wide are the internal programmatic interconnections based on it (as a result of learning not only simple conditioned reflexes, but also speech and thinking, a sign-symbolic system, or a second signal system, according to I.P. Pavlov , as the basis of a kind of software "software" that fills the biological "hard" neural networks with even greater content diversity) and external social relations (from microsociety - a system called "family", to macro-social state, ethno-cultural, gender-gender, professional, religious-confessional, political or other value systems with their own systems of broadcast codes and programs).

How wide are the interconnections of a person in his colossal neural network with 86 billion neurons and many trillions of their connections (100–150, according to various estimates of researchers), just as wide are the internal programmatic interconnections based on it (as a result of learning not only simple conditioned reflexes, but also speech and thinking, a sign-symbolic system, or a second signal system, according to I.P. Pavlov , as the basis of a kind of software "software" that fills the biological "hard" neural networks with even greater content diversity) and external social relations (from microsociety - a system called "family", to macro-social state, ethno-cultural, gender-gender, professional, religious-confessional, political or other value systems with their own systems of broadcast codes and programs).

Ignoring these factors and relationships critically reduces medical and psychological care to the level of a specialist in a particular organ, tissue or syndrome, who considers it as an existing ideal model of a spherical horse in a vacuum regardless of the universe.

In order to effectively help a person’s mental health, to reveal his black box as a phenomenon (as well as Watson’s “boxes” and Skinner’s along the way), it is necessary to include the client / patient in therapy not in the form of a passive object for manipulations and interventions, but in the status of an active actor therapy and an equal partner in all processes integrated by a systemic therapeutic approach. Only in the course of a working alliance and the development of therapeutic relationships is it possible to systematically work on the actualization of a person's potential and his large-scale internal and external resources. The qualities and skills of skilled therapists are critical to forming an alliance and a therapeutic relationship. The skills and competencies of psychotherapists and psychologists in building effective communication go far beyond the clinical model. They also apply to interpersonal relationships, working with families, groups and organizations. That A. Beck tried to formulate in 2014 as a generative cognitive model (The Generic Cognitive Model) [1], the methodology of which helps to go far beyond therapy and the medical model, forming the systemic context of a new interdisciplinary form of the cognitive model.

That A. Beck tried to formulate in 2014 as a generative cognitive model (The Generic Cognitive Model) [1], the methodology of which helps to go far beyond therapy and the medical model, forming the systemic context of a new interdisciplinary form of the cognitive model.