Mental image psychology definition

Mental Imagery | in Chapter 07: Cognition

Mental Imagery

Mental imagery can be defined as pictures in the mind or a visual representation in the absence of environmental input. This is not a universal talent; not everybody can conjure up mental images at will.

Sir Francis Galton discovered this in 1883 when he asked 100 people, including prominent scientists, to form an image of their breakfast table from that morning. Some had detailed images, others reported none at all.

What is the easiest way to make visual imagery stronger?

Almost everybody has mental imagery during dreams. That includes people who go blind at an early age after gaining some experience with vision, but not people who never see at all.

Some individuals are capable of deep levels of hypnosis in which they can have visual hallucinations of dreamlike clarity. That is rare. For most of us, mental imagery during states of wakefulness is faint or difficult to manipulate.

The best way to make imagery more vivid is to imitate the conditions of sleep. When one is relaxed or half asleep, mental imagery can be quite vivid.

Simply pressing lightly on closed eyelids can result in an explosion of geometric forms. You might recall from Chapter 3 that vivid imagery sometimes occurs upon awakening, in the hypnopompic state.

What do brain scans show about brain areas involved in mental imagery?

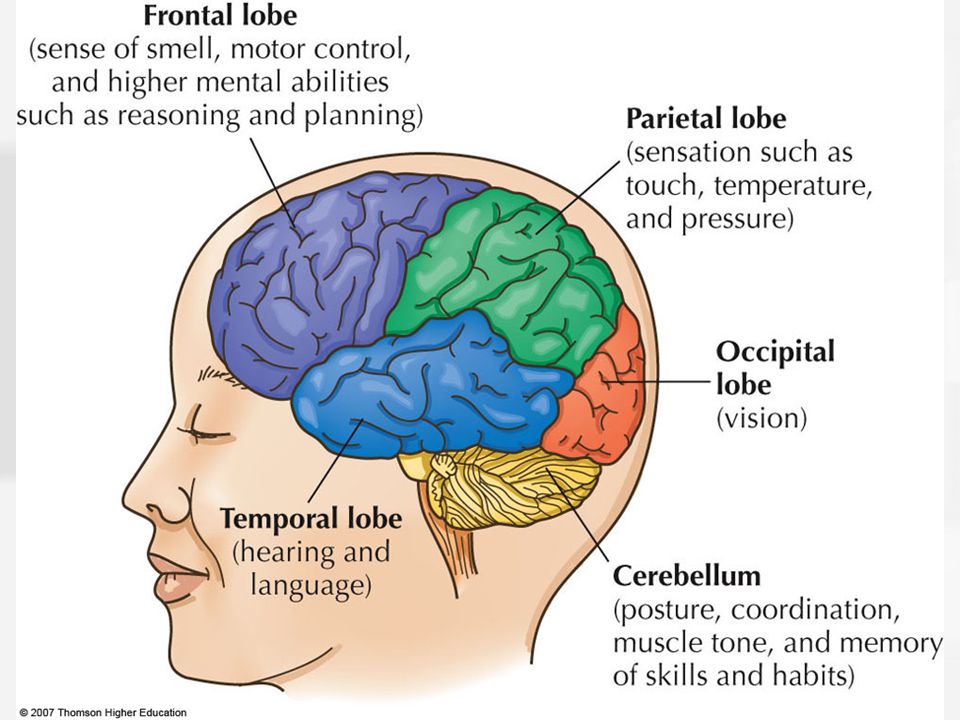

An abundance of evidence from brain scanning research shows that the same areas of the brain used for normal perception are also activated by mental imagery. (Miyashita, 1995).

In general, imagining any cognitive activity seems to activate the same areas of the brain normally involved in that activity. For example, "thinking about a telephone activates some of the same brain areas as seeing a telephone." (Posner, 1993)

Early, important studies of mental imagery came from Roger Shepard of Stanford University and various colleagues. He used computer-generated block shapes similar to these:

He used computer-generated block shapes similar to these:

One shape is different from the others.

Three of the shapes are the same as each other, only rotated. The fourth is different; it is a mirror image of the others. Can you find the one that is a mirror image?

To determine this, most subjects must mentally rotate the figures, much as they would rotate a three-dimensional block model, to see if each matches the others.

Why was the Cooper and Shepard research influential?

Following up on the first experiments with mental rotation, Cooper and Shepard (1973) found that the time required for mental rotations depended upon the amount of rotation. This was a very important finding, because it implied that mental images could be manipulated as if real.

Mental Maps and Images

Steven Kosslyn of Harvard is famous for studies of mental imagery. Kosslyn found that the size of an imagined image influenced how quickly subjects could move around the image in memory. If subjects memorized a map, the time it took them to make a mental jump from one location to another depended upon the distance on the imagined map.

If subjects memorized a map, the time it took them to make a mental jump from one location to another depended upon the distance on the imagined map.

In one experiment, Kosslyn (1975) asked subjects to imagine animals standing next to one another, such as a rabbit next to an elephant or a rabbit next to a fly. Then subjects were asked questions such as, "Does the rabbit have two front paws?"

When asked to imagined a rabbit next to a fly, people were quick to answer questions about the rabbit's appearance. They were slower when first asked to imagine it next to an elephant.

People took longer to answer such questions when the rabbit was imagined next to an elephant. In that condition, the rabbit's image was small.

When the rabbit was imagined next to a fly, its imagined image was large. Then subjects were quick to answer questions about the image. Kosslyn concluded that visual imagination produces "little models, which we can manipulate much like we do actual objects. "

"

What did Kosslyn find, concerning scanning of mental maps? When he had subjects imagine a rabbit next to a fly?

Researchers have identified two types of mental imagery. One is for pictures (for example, visualizing the rabbit next to the fly), and one for spatial representation (for example, rotating shapes in imagination).

Kosslyn's work focused on imagined pictures. Shepard and colleagues focused on imagined rotation of shapes in space. The two involve different brain areas, and the two skills can be doubly dissociated by brain injury (you can lose one but not the other).

The ability to imagine pictures can be lost after damage to the back of the brain, near the occipital lobe. The ability to imagine space is lost after damage to the middle of the right hemisphere, near the parietal lobe.

Memory Mostly for Meaning

Although mental imagery can be vivid and detailed, most people have rather poor memory for the details of a picture. We remember mostly the meaning of a picture, not details.

We remember mostly the meaning of a picture, not details.

Baggett (1975) showed that detailed picture memory fades over several days. She showed subjects a short cartoon in one of two versions. One she called the explicit version. It showed a longhaired person getting hair cut.

The other she called the implicit version. It showed no actual hair cutting. However, it did show a person walking out of a barbershop with shorter hair.

After showing one or the other version to her subjects, Baggett waited various lengths of time. Then she asked subjects whether a test picture, showing hair actually being cut, appeared in the original sequence.

How did Baggett investigate memory for pictures? What did she discover?

The implicit version (left) did not show hair being cut.

For up to three days, subjects who received the implicit version knew they had not seen the test picture. However, after three days, they were likely to believe they had seen the hair being cut, even though they had not.

Why? It was consistent with the story told by the pictures. When someone walks out of a hair salon with shorter hair, one infers that hair was cut. It is another case of going "beyond the information given," in Bruner's words.

Baggett concluded that after three days participants lost detailed memories for the images themselves. They mostly remembered the meaning or story behind those images. The test item seemed familiar because it fit with the meaning of the images.

In summary, it appears that most people can generate mental images and manipulate them like little models, as Kosslyn put it. However, mental images are mostly lost after a few days. Then we use inference to help re-construct images based on remembered knowledge.

---------------------

References:

Baggett, P (1975). Memory for explicit and implicit information in picture stories. JVLVB, 14, 538-548.

Cooper, L. A. & Shepard, R. N. (1975). Mental transformations in the identification of left and right hands. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 104, 48-56.

Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 104, 48-56.

Miyashita, Y. (1995) How the brain creates imagery: Projection to the primary visual cortex. Science, 268, 1719-1720.

Posner, M. I. (1993). Seeing the mind. Science, 262, 673-676.

Prev page | Page top | Chapter Contents | Next page

Write to Dr. Dewey at [email protected].

Don't see what you need? Psych Web has over 1,000 pages, so it may be elsewhere on the site. Do a site-specific Google search using the box below.

Copyright © 2007-2018 Russ Dewey

Mental Images Examples in Cognitive Psychology —Ifioque.com

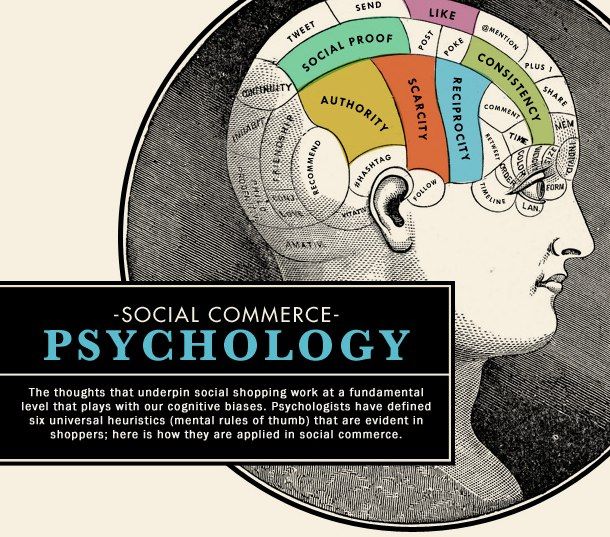

Psychologists generally define thinking as the mental representation and manipulation of information. When we think, we often represent information in our minds in the form of images.

- A mental image is a mental picture or representation of an object or event.

People form mental images of many different objects—faces of familiar people, the lay-out of the furniture in their homes, the letters of the alphabet, a graduation or religious ceremony.

A mental image is not an actual or photographic representation. Rather, it is a reconstruction of the object or event from memory.

The ability to hold and manipulate mental images helps us perform many cognitive tasks, including remembering directions. You could use verbal descriptions (“Let’s see, that was two lefts and a right, right?”). But forming a mental image—for example, picturing the church where you make a left turn and the gas station where you make a right—may work better.

Mental imaging can also lead to creative solutions to puzzling problems. Many of Albert Einstein’s creative insights arose from personal thought experiments. His creative journey in developing his landmark theory of relativity began at age 16 when he pictured in his mind what it would be like to ride a light beam at the speed of light (Isaacson, 2007). He was later to say that words did not play any role in his creative thought. Words came only after he was able to create mental images of new ideas he had formulated in his thought experiments.

He was later to say that words did not play any role in his creative thought. Words came only after he was able to create mental images of new ideas he had formulated in his thought experiments.

The parts of the visual cortex we use in forming mental images are very similar to those we use when actually observing objects. Yet there is an important difference between an image imagined and image seen: The former can be manipulated, but the latter cannot. For example, we can manipulate imagined images in our minds by rotating them or perusing them from different angles. Figure X provides an opportunity to test your ability to manipulate mental images.

| Figure X. Are the objects that form a pair in this figure the same? Answering this question depends on your ability to rotate objects in your mind’s eye. |

Figure X. Mental Rotation | Are the objects that form a pair in this figure the same? Answering this question depends on your ability to rotate objects in your mind’s eye. |

Investigators finder gender differences in mental imagery. For example, women tend to outperform men in remembering the spatial location of objects (Aamodt & Wang, 2008). Perhaps that’s why husbands seem so often to ask their wives where they have put their keys or their glasses. Women may be better at recalling where things are placed because of their greater skill in visually scanning an image of a particular location in their minds.

Mental imagery is not limited to visual images. Most people can experience mental images of other sensory experiences, such as “hearing” in their minds the rousing first chords of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony or recalling the taste of a fresh strawberry or the feel of cotton brushing lightly against the cheek. Yet people generally have an easier time forming visual images than images of other sensory experiences.

- Citations

mental image - frwiki.wiki

The term mental image is used in philosophy, communication, and cognitive psychology to describe a remembered or imagined brain representation of a physical object, concept, idea, or situation. The especially developed ability of humans to form, remember, and use mental images, perceive the environment, and communicate with others is closely related to intelligence. Biologists and anthropologists are divided over this type of ability in other species.

These debates present in biology are usually ignored in other fields, which tend to focus on human knowledge. However, adaptive intelligence, whether human or animal, seems to be closely related to the ability to store, process, and develop multiple images and mental representations.

Summary

- 1 Birth and evolution of mental images

- 2 Philosophical approaches

- 3 Teaching use

- 4 In experimental psychology

- 5 In sports psychological training

- 6 Notes and references

- 7 See also

- 7.1 Related Articles

- 7.2 External links

Birth and evolution of mental images

Throughout our lives, probably starting from the prenatal phase of the fetus, our life experience generates many elements of mental representation that form new images in our minds or modify or enrich existing images. In this way, a network of images is maintained, each of which can be liked by others. Certain privileged sequences form true dynamic meta-images, similar to the neural pathways that underlie the functioning of the lower level brain.

Three types of experience are involved in this process:

- that perception by one or more of our five senses, in particular vision, which is the most powerful, but not the only, generator of mental images.

Some of these perceptions and sensations are experienced, others are sought,

Some of these perceptions and sensations are experienced, others are sought, - imagination and reflection over which we have some control,

- then dreams, waking visions and hallucinations that are out of our control and aware spontaneously arise unpublished images.

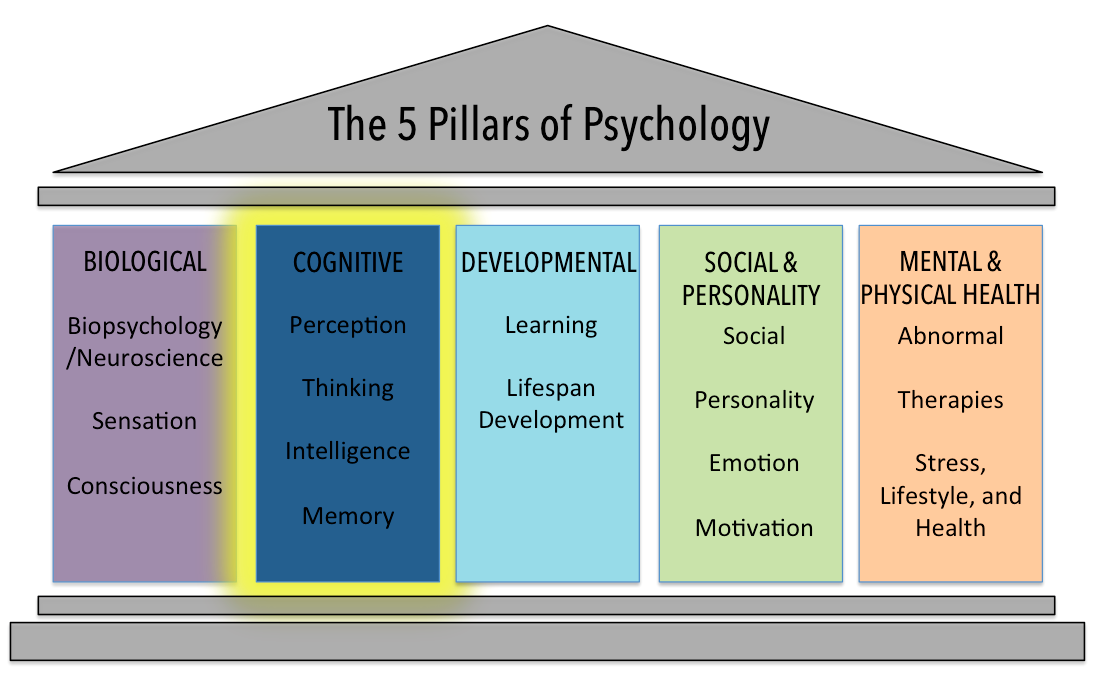

In each of these cases, the brain manipulates mental representations, evaluates them, compares them, connects them, combines them with or without external stimuli. In its normal (as opposed to pathological) functioning, the brain tends to maintain a store of images that enables it to find effective solutions to present and expected situations. Thus, cognitive strategies, more or less conscious, contribute to the development of our representations in the direction of what we consider to be reality, and in the artistic and imaginary fields, images, sources of pleasure and satisfaction, often deliberately dissociated, reality. In a continuous loop, these images, as well as their sequence, are evaluated according to their effectiveness in meeting our needs and goals of all kinds, and then modified accordingly. Cognitive psychology focuses on operations that can harm mental images.

Cognitive psychology focuses on operations that can harm mental images.

Philosophical approaches

The concept of mental images is central to classical and modern philosophy, as it is inseparable from the study of knowledge. In his Book VII of the Republic, Plato uses the well-known metaphor of prisoners in a cave, chained and immobilized, who turn their backs to the entrance and see only on the wall facing them their shadows and those that come from them. objects moving or far behind them. This metaphor exposes in visual terms the dangerous journey of people to the knowledge of reality restored in consciousness from a person to representations built from simplified and distorted images perceived by our senses (Cf allegories of the cave). Plato also brings about an equally difficult transmission of knowledge that runs into blindness and a difficult confrontation of mental representations resulting from various experiences.

In the XVIII - and centuries, George Berkeley developed similar ideas in his theory of idealism. According to Berkeley, reality exists only through our mental images, these are not representations of material reality, but reality itself. However, Berkeley clearly distinguished between images related to the knowledge of the external world, images that arise as a result of individual imagination, and the latter, in his opinion, is not part of "mental images" in the modern sense of the expression.

According to Berkeley, reality exists only through our mental images, these are not representations of material reality, but reality itself. However, Berkeley clearly distinguished between images related to the knowledge of the external world, images that arise as a result of individual imagination, and the latter, in his opinion, is not part of "mental images" in the modern sense of the expression.

Also in in the 18th century - th century the British writer and doctor Samuel Johnson, who, while walking in Scotland, he asked his opinion about idealism, made the following reply: “I see it as refuted! which he accompanied with a hard enough kick against a stone that made him jump with his foot. It was a way for him to show that considering the stone's existence as a pure mental image, devoid of any material support to speak of, would be a very poor explanation for the pain he had just experienced.

Critics of scientific realism ask how the internal perception of mental images actually occurs. This is sometimes referred to as the "homunculus hypothesis" (see also "mind's eye"). This problem boils down to asking in what forms the images displayed on the computer screen exist in the memory of the latter.

This is sometimes referred to as the "homunculus hypothesis" (see also "mind's eye"). This problem boils down to asking in what forms the images displayed on the computer screen exist in the memory of the latter.

For scientific materialism, mental images and their perception can only arise from mental states. According to these philosophers, scientific realists cannot find the location of images and their perception in the brain. These critics argue that neuroscience has failed to identify the components, processes, or memory in the brain that process and store images in the same way that a computer, graphics card, and its memory can.

Use in teaching

Learning styles largely define representation and memory skills that emphasize visual, auditory, or kinesthetic (related to the meaning or sensations of movement or body posture) of the experiment.

According to educational theorists, the acquisition of knowledge is facilitated by the simultaneous realization of several sensory areas (visual, auditory or kinesthetic). This need is met by teaching methods that include speech, gestures, and the display/animation of graphic and text images.

This need is met by teaching methods that include speech, gestures, and the display/animation of graphic and text images.

The use of existing mental images without sensory perception or physical input facilitates learning. For example, repeating a non-piano piano exercise only while visualizing the keyboard (mental practice) can significantly improve subsequent performance (albeit less effectively than physical practice). The authors of a related study stated that "mental practice alone appears to be sufficient to stimulate the modulation of neural circuits involved in the early stages of motor automatism acquisition" (Pascual-Leone 1995).

In experimental psychology

Cognitive psychologists and later neuroscientists empirically studied how the human brain uses mental images to build knowledge.

The metaphor of the 1970s tried to connect the brain with the computer as a serial processor of information. Zenon Pilyshyn presented cognition as a form of computation and argued that the semantic content of mental states is encoded in the same way as the semantic content of computer representations - a network state formed by a set of states of neurons and interconnections in a participant.

Psychologist Zenon Pilyshyn developed the theory that the human mind processes mental images, breaking them down into fundamental mathematical statements.

Roger Shepard and Jacqueline Metzler (1971) countered this by presenting people with a figure made up of lines representing a three-dimensional object and asking them to determine if other figures were representations of the same object after rotation in space. Shepard and Metzler suggested that if we decompose and then mentally recompose objects into basic mathematical sentences - as the prevailing thought of the day, proposed by analogy with computer processing - the time to determine whether an object was the same or not, then would not depend on the degree of rotation of the object. However, this experiment, on the contrary, showed that this time was proportional to the degree of rotation that the object underwent in the figure. Thus, Shepard and Metzler were able to conclude that the human brain maintains and manipulates mental images as global topographical and topological objects.

More recent studies have confirmed these results, showing that people are slower to mentally orient images of limbs, such as hands, in directions inconsistent with the rotation of the joints of the human body (Parsons 2003), and that patients who have an injured hand and pain are slower to mentally rotate the hand drawing on the side of the injured hand (Schwoebel 2001).

Some psychologists, including Stephen Kosslin, suggest that these results are related to the interaction between brain regions that process visual representations and those that process motor representations. Koslin (1995 and 1994) supports this hypothesis with a series of brain images showing where objects such as the letter "F" are held and controlled, as global images, in the visual cortex.

In cognitive science have led to a relative consensus on the neural state of mental images. Most researchers in psychology and neuroscience agree that there is no homunculus (central system that controls all or part of the brain) or process that structures the viewing of mental images. How these images are stored and processed, in particular in language, communication and in relation to our physical environment, remains a fertile field of study (Rohrer 2006) at the intersection of several areas: psychology, neuroscience, philosophy.

How these images are stored and processed, in particular in language, communication and in relation to our physical environment, remains a fertile field of study (Rohrer 2006) at the intersection of several areas: psychology, neuroscience, philosophy.

In sports psychological training

Mental imagery is commonly used in mental preparation to boost self-confidence by helping visualize images of past successes and results from particularly successful meetings (as opposed to mental rehearsal). The visualization technique starts with a state of relaxation (breathing, relaxing, etc.) and then visualizing the progress of successful actions chosen for their stimulating nature and their ability to reinforce winning behavior.

However, this technique should not be abused. In general, the stronger and more intense the confidence, the more likely it is to cause confusion if it fails. Therefore, this technique should only be used when the athlete has doubts.

Notes and links

- ↑ Dynamics of Forms and Representation: Toward the Human Biosymbol - Mikael Hayat - Published by L'Harmattan, 2002]

- ↑ Mental image: (Evolution and dissolution) - Jean Philippe - Published by F.

Principles of Human Knowledge - George Berkeley - Published by A. Colin, 1920

Principles of Human Knowledge - George Berkeley - Published by A. Colin, 1920 - ↑ Mental Imagery and Learning Strategies: Explanation and Criticism, Modern Tools of Mental Control - Elisabeth Grebot - Published by Esf Éditeur, 1994

- ↑ Magali Bove and Daphne Woellin, The Role of the Mental Image in Operational Reasoning: Auxiliary or Structuring? , Paris, University Press of France, 2003

- ↑ Computing and Cognition: Toward the Foundation of Cognitive Science, MIT Press, 1984

- ↑ (in) The return of the mental image: are pictures really in the brain?

- ↑ (en) Recent publications on Shepard-Metzler

- ↑ (in) Image and Brain: The Resolution of the Image Debate - Michael Stephen Kosslin - Published by MIT Press, 1996]

- ↑ Mental image and development (preface) - J.

Bidault and J. Courbois - PUF, 1998

Bidault and J. Courbois - PUF, 1998 - ↑ (in) Vision and visualization: it's not what you think - Zenon V. Pilyshyn - Published by MIT Press, 2003]

- ↑ (in) Critical review of Zenon's "Pylyshyn" Vision and Visualization: It's Not What You Think It Is - Katharina Abell, 2005]

See Also

Related Articles

- Presentation

- Representation of the world

- Aphantasia, inability to imagine a mental image

External links

- Note in a dictionary or general encyclopedia: Encyclopædia Universalis

- Research resources:

- (en) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Mental image | it's... What is a mental image?

Image in psychology is a mental (mental) image of an object perceived by him in the environment. When a person looks at and perceives an object in the environment, a mental image of this object is formed in his head. An image can arise without perception, with the help of daydreaming.

- Art is the process and result of meaningful expression of feelings in an image.

- Thinking creates and perceives images in the language of sensory perception.

- NLP introduces the concept of a representational system, which defines the language in which thinking encodes images.

- Imaginative thinking

Figurative thinking - thinking in the form of images through their creation, formation, support, transmission, operation, modification with the help of thought processes. It enters as an essential component in all types of human activity without exception. It is implemented using the presentation mechanism. It conveys knowledge not about separate isolated aspects (properties) of reality, but forms a holistic mental picture of a separate area of reality. Spatial thinking, associative thinking, visual-figurative thinking, visual thinking can be considered as varieties of figurative. It is opposed to non-figurative thinking.

It is implemented using the presentation mechanism. It conveys knowledge not about separate isolated aspects (properties) of reality, but forms a holistic mental picture of a separate area of reality. Spatial thinking, associative thinking, visual-figurative thinking, visual thinking can be considered as varieties of figurative. It is opposed to non-figurative thinking.

- Logical thinking

An image in culture is a product of human thought, a psycho-energetic object, an energy essence, created individually or collectively in the information space (field). The ability to create images is a unique ability that only a person is endowed with. An image created by a person can exist in space if it is nourished by the psychophysical energy of a person, the energy of feelings and emotions, as long as a person, people (community) represents it with his thought.

The more people feed the image with their feelings, the stronger the image, the stronger the possibility of the reverse influence of the image on the activities of a person, people (community). Able to form characters, behavior of large and small social groups, in connection with which the problem arises of a certain culture of creating images inherent in peoples and countries, nations, states and ethnic groups. The heritage of figurative thinking of any people can be considered as a kind of "imprint" of its views on the world, the idea of life, its mission in the world, a kind of cultural self-portrait.

Able to form characters, behavior of large and small social groups, in connection with which the problem arises of a certain culture of creating images inherent in peoples and countries, nations, states and ethnic groups. The heritage of figurative thinking of any people can be considered as a kind of "imprint" of its views on the world, the idea of life, its mission in the world, a kind of cultural self-portrait.

- Imaginative perception

Figurative perception is a fundamentally holistic one-stage process, recognition, recognition of an object, process, phenomenon "as a whole", identifying it with its own "representation" or establishing a connection, similarity, analogue of a new object with an already existing holistic natural phenomenon (figurative perception of nature), reality. The formation of the image is based on the existing life experience, human knowledge. Part of this experience is genetically shaped, and then one speaks of the "experience of previous generations. " Part of this experience can be accumulated by society in the form of knowledge and transferred by society to a person in the process of learning (language, writing, conceptual base, social models of behavior, etc.). Learning is the process of transforming the knowledge of society into the knowledge of a particular person. Sometimes it is identified with emotional perception and is opposed to analytical (abstract). However, in its pure form, each of the ways of perception is rare, usually the emotional and analytical flow together. From a dialectical point of view, figurative and abstract thinking are inseparable, but in the vast majority of situations one can speak of the conditional predominance of one or another type. The nature of figurative perception is not fully disclosed. Perceiving reality, a person receives "at the input" a certain amount of information, and "at the output" a holistic image is formed, characterized by some finite set of concepts. We "read" not letters, but words and phrases; “we see” not a “fragment” of the picture, but its integrity, we “hear” not individual sounds, but their totality.

" Part of this experience can be accumulated by society in the form of knowledge and transferred by society to a person in the process of learning (language, writing, conceptual base, social models of behavior, etc.). Learning is the process of transforming the knowledge of society into the knowledge of a particular person. Sometimes it is identified with emotional perception and is opposed to analytical (abstract). However, in its pure form, each of the ways of perception is rare, usually the emotional and analytical flow together. From a dialectical point of view, figurative and abstract thinking are inseparable, but in the vast majority of situations one can speak of the conditional predominance of one or another type. The nature of figurative perception is not fully disclosed. Perceiving reality, a person receives "at the input" a certain amount of information, and "at the output" a holistic image is formed, characterized by some finite set of concepts. We "read" not letters, but words and phrases; “we see” not a “fragment” of the picture, but its integrity, we “hear” not individual sounds, but their totality. The result of figurative recognition is generally ambiguous. Figurative thinking is fundamentally based on "similarity".

The result of figurative recognition is generally ambiguous. Figurative thinking is fundamentally based on "similarity".

- Figurative language

Figurative language - the language of images does not always use words, although it is often identified with literary language. However, often the means of figurative thinking are not words and letters, but visible images. The means of figurative language include hieroglyphs that convey a holistic image, meaning and even direction of action, runes, letter-images, symbols, etc. Figurative language allows you to highlight the features of a phenomenon, certain qualities of an object, strengthen and consolidate the emotional, aesthetic perception of a phenomenon, form and remember the impressions from it in a single holistic form.

- Figurative perception of nature

Figurative perception of nature - a historically fixed period of formation and development of the ancient world, associated with the formation of myths, the creation of images of gods, as products of figurative, holistic perception of natural reality, natural elements, elements, substances and compounds by people.

Nevid, Psychology: Concepts and Applications (p. 252-3) "Mental Images: In Your Minds Eye".

Nevid, Psychology: Concepts and Applications (p. 252-3) "Mental Images: In Your Minds Eye".