Mental illness living in a fantasy world

The Subtle Effects of Trauma - Living in a Fantasy

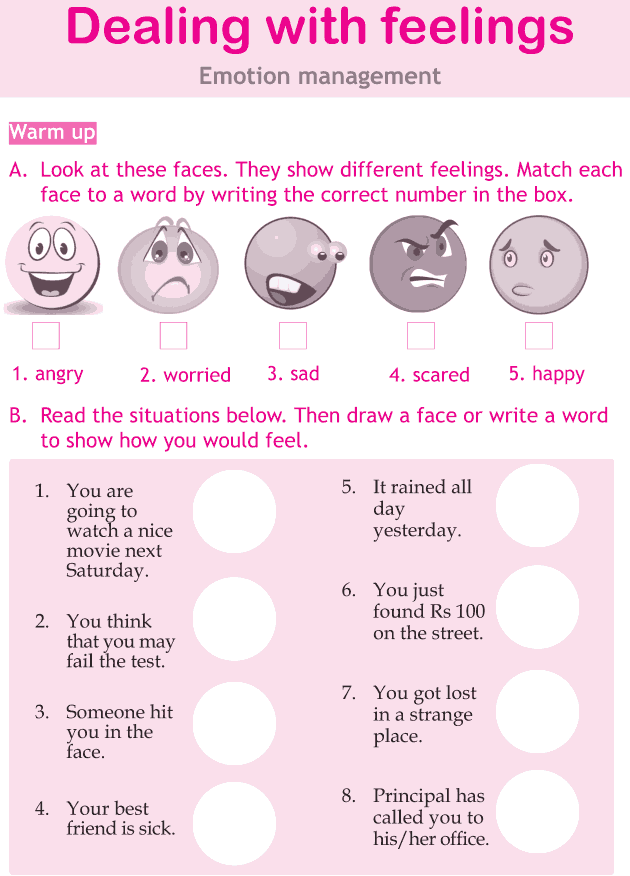

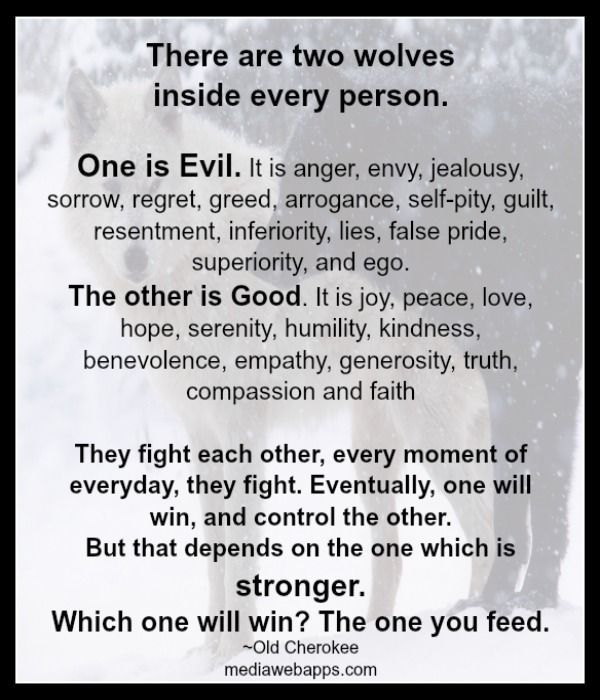

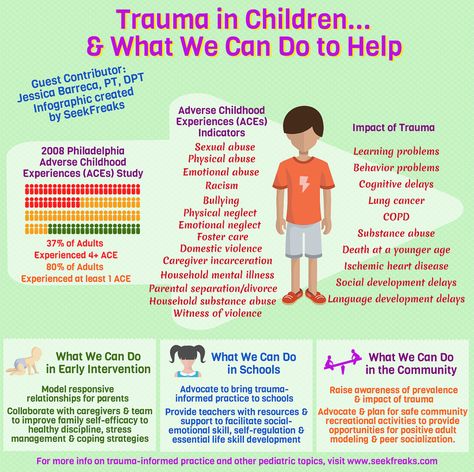

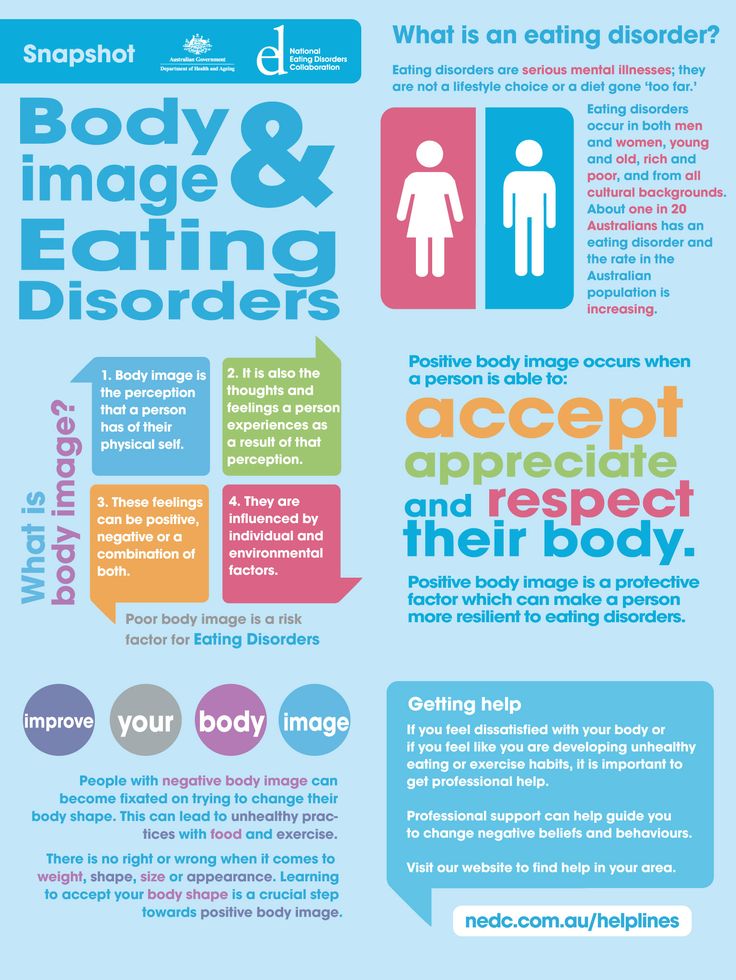

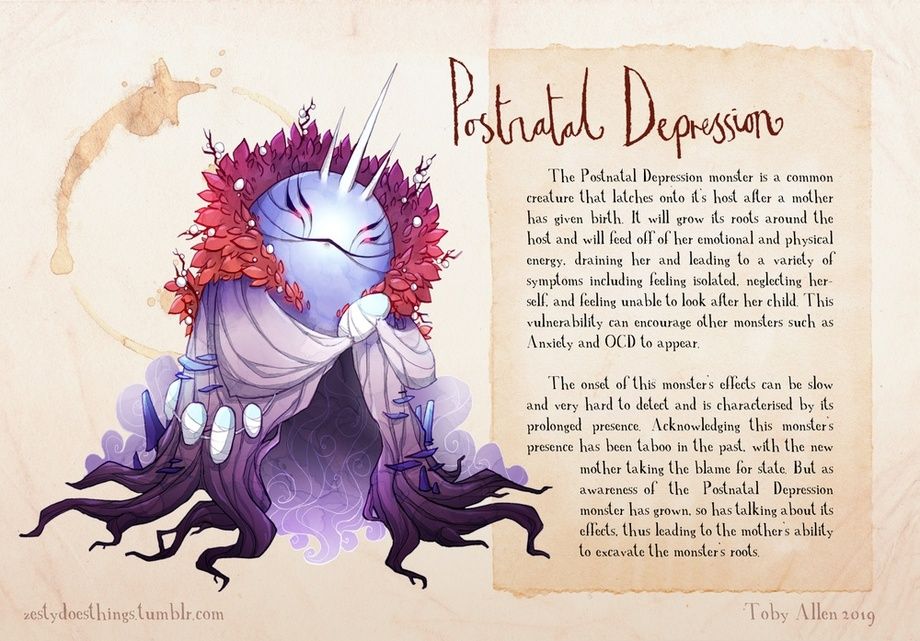

When we are children, and our needs go unmet, our environment is painful, or we have emotional wounds, we may have a fantasy our situation, environment, or relationships will change and we will feel better. For example, a child living in an unsafe home may imagine a character from a television show coming to their house and rescuing them from their situation. Essentially, we daydream about escaping our reality. Living in a fantasy or always daydreaming about positive change is one of the more subtle effects of trauma, but it can be toxic to our health and lead to:

- Strained relationships

- Unhealthy relationships

- Behavioural addictions

- Substance use disorder

- Dependence on others

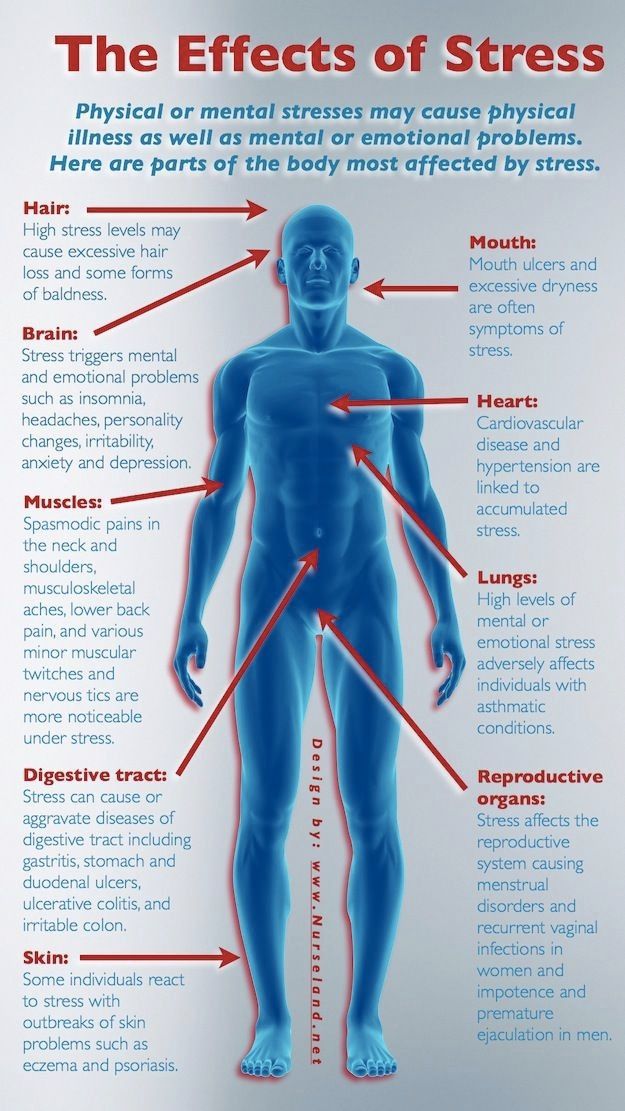

- Anxiety and depression

Daydreaming itself is not problematic. We all do it, and it can help us exercise our imagination and explore our private responses to life and its events. However, as is the case with any trauma symptom, and any substance or behavioural addiction, daydreaming and fantasy is problematic when it becomes a compulsion and interrupts our normal daily well-being and functioning. [1]

When you are only daydreaming about a different future but not doing the actions or tasks that will get you there, then daydreaming is maladaptive. Below are some common ways in which we fantasise or daydream about our lives changing for the better.

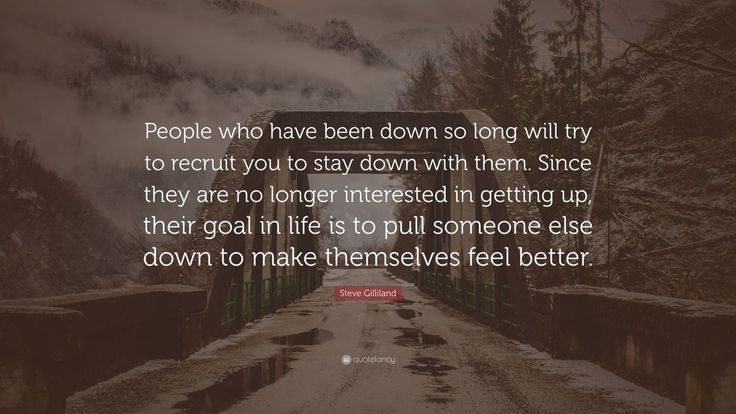

Wanting to Save/Be SavedMany of us engage in rescue fantasies, particularly in romantic relationships, where we believe we can be a knight in shining armour for our romantic interest and save them from their situation, to be praised and seen as a hero in our fantasy world.[2] Alternatively, we may imagine that we will be rescued by someone – a person will come along and make us happy by changing our current situation.

Both types of rescue fantasy can be harmful and counterintuitive to authentic, healthy intimate connections. The fantasy may seem to come true in the short-term. Still, over time as our situations change we may continue to place these heroic expectations on ourselves or on our partners – these are often unrealistic or impossible to live up to. Over time, the need or desire to replay that fantasy returns, and the person we once believed we saved, or saved us, seems to change and we seek other people to play these characters in a vicious and destructive fantasy cycle.

Over time, the need or desire to replay that fantasy returns, and the person we once believed we saved, or saved us, seems to change and we seek other people to play these characters in a vicious and destructive fantasy cycle.

As children, we are virtually powerless. We don’t have a wide range of choices available to us to make changes in our environment or our living situation because we are dependent on the adults in our lives. This sense of powerlessness may be appropriate for the child but becomes a problem if we carry this perceived sense of powerlessness into adulthood, feeling like you can’t do anything to make your life different. Many of us seek out ways to make others change so that we can feel better, and feel hopeless or helpless when we realise we can’t change anyone else. The reality is that as adults, we need to take responsibility for our own needs – we need to recognise what we need for ourselves and show up differently in ourselves of our own accord.

In childhood, seeking validation from others is a regular aspect of development, and as we grow up we do move through many environments in which external validation is normalised, such as in school, in sports, in our family – we get praise or criticism externally. As an adult, our responsibility to ourselves is to internalise the feeling of validation, that we are good enough in the absence of external validation. This is so that we can feel good when it seems the world does not show up for us. This doesn’t mean that we don’t feel good when we achieve something in the outside world, such as a promotion at work or a compliment from our partner, but when those types of validation are not happening that we don’t sink into a depression or believe that we are unworthy.

Seeking Quick Fixes

As children, we do not usually have much patience regarding the desire to feel good or not to feel bad. We want results immediately. When we carry this into adulthood, we continue to seek quick fixes that can be destructive to our health, such as unhealthy relationships or the use of substances for the sake of any kind of connection, or to escape our thoughts and feelings. We need to cultivate an acceptance of delayed gratification so that we can make responsible and mature choices that help us reach our long term goals.

When we carry this into adulthood, we continue to seek quick fixes that can be destructive to our health, such as unhealthy relationships or the use of substances for the sake of any kind of connection, or to escape our thoughts and feelings. We need to cultivate an acceptance of delayed gratification so that we can make responsible and mature choices that help us reach our long term goals.

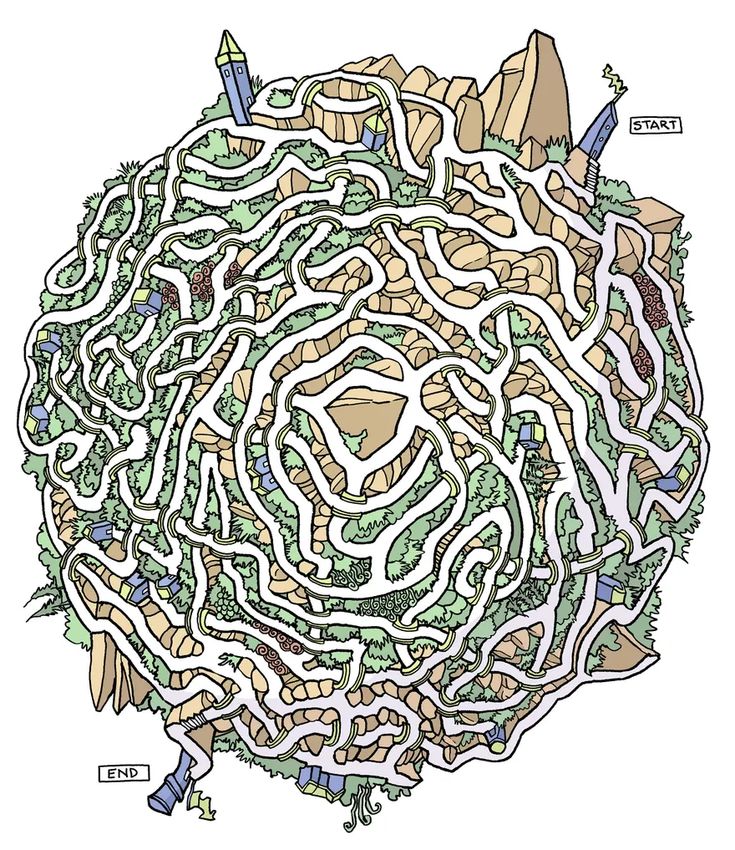

Early emotional wounds can disconnect us from reality[3] and cause us to seek out alternate universes and situations in which we are happy or in which we had never experienced our deep pain. Understandably, people seek relief from their pain, especially if that pain has been carried into adult life from childhood. However, continually fantasising or daydreaming about a better life can distract us from any real, present opportunities to make a positive change. If we want to come back to reality and live our lives in the present moment – the only place where we can experience real joy and fulfilment – then we must seek help and treatment for our emotional wounds.

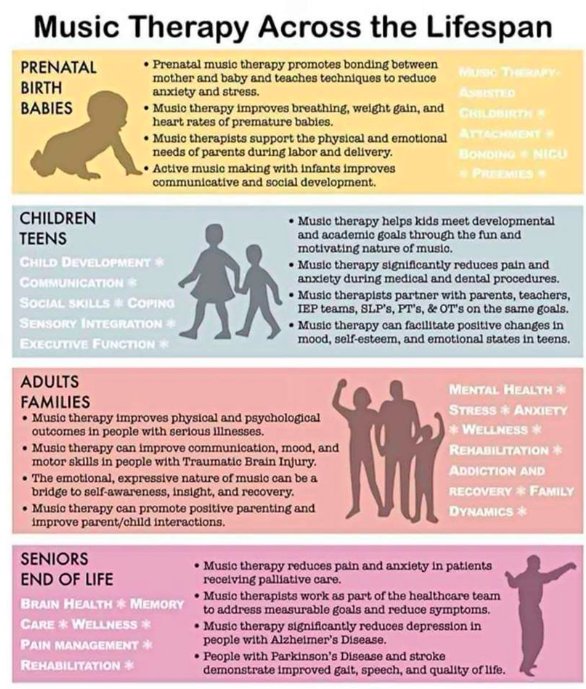

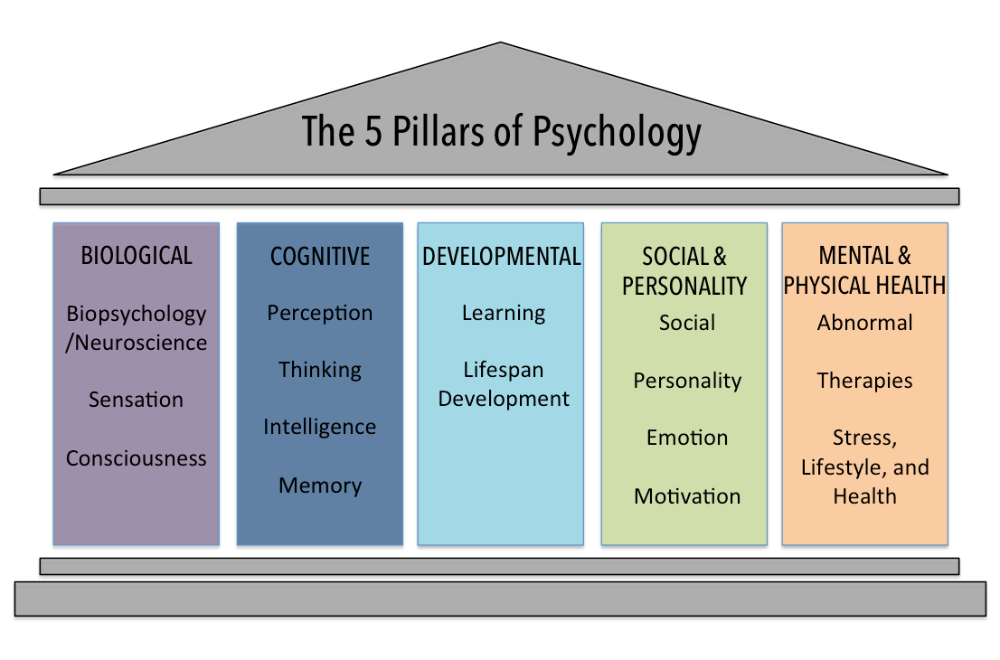

Various therapies are available to help survivors of trauma build the strength and resilience to face, reframe, and integrate their past traumatic experiences into the present life so that they no longer need to escape. Trauma can be effectively approached through therapies such as Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioural Therapy[4] (TF-CBT), in which therapist and client explore the ‘cognitive triangle’ – the thought, feelings, and behaviours that characterise our life and our personal outcomes. Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) can help clients heal from their trauma by supporting them in staying present and grounded in the moment as they explore their trauma memories and narrative.[5] Somatic Experiencing (SE) is also a popular trauma-healing approach, as it supports clients in reconnecting with and exploring the physical sensations associated with their traumatic memories.[6]

Recovery from trauma is not an overnight journey. It takes time and conscious effort, as well as compassionate care and support. However long it takes, beginning the healing journey yields far better personal outcomes than not taking the journey at all.

It takes time and conscious effort, as well as compassionate care and support. However long it takes, beginning the healing journey yields far better personal outcomes than not taking the journey at all.

If you have a client, or know of someone who is struggling to heal from psychological trauma, reach out to us at Khiron Clinics. We believe that we can improve therapeutic outcomes and avoid misdiagnosis by providing an effective residential program and out-patient therapies addressing underlying psychological trauma. Allow us to help you find the path to realistic, long-lasting recovery. For information, call us today. UK: 020 3811 2575 (24 hours). USA: (866) 801 6184 (24 hours).

Sources

[1] Soffer-Dudek, Nirit, and Eli Somer. “Trapped in a Daydream: Daily Elevations in Maladaptive Daydreaming Are Associated With Daily Psychopathological Symptoms.” Frontiers in psychiatry vol. 9 194. 15 May. 2018, doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00194

15 May. 2018, doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00194

[2] Farrell, Kirby. “Love, Loss, And Heroic Rescue”. Psychology Today, 2016, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/swim-in-denial/201604/love-loss-and-heroic-rescue. Accessed 11 Nov 2020.

[3] Lahousen, Theresa et al. “Psychobiology of Attachment and Trauma-Some General Remarks From a Clinical Perspective.” Frontiers in psychiatry vol. 10 914. 12 Dec. 2019, doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00914

[4] Cohen, Judith A, and Anthony P Mannarino. “Trauma-focused Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Traumatized Children and Families.” Child and adolescent psychiatric clinics of North America vol. 24,3 (2015): 557-70. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2015.02.005

[5] Shapiro, Francine. “The role of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy in medicine: addressing the psychological and physical symptoms stemming from adverse life experiences.” The Permanente journal vol. 18,1 (2014): 71-7. doi:10.7812/TPP/13-098

18,1 (2014): 71-7. doi:10.7812/TPP/13-098

[6] Brom, Danny et al. “Somatic Experiencing for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Outcome Study.” Journal of traumatic stress vol. 30,3 (2017): 304-312. doi:10.1002/jts.22189

Living in an Imaginary World

When Rachel Stein (not her real name) was a small child, she would pace around in a circle shaking a string for hours at a time, mentally spinning intricate alternative plots for her favorite television shows. Usually she was the star—the imaginary seventh child in The Brady Bunch, for example. “Around the age of eight or nine, my older brother said, ‘You're doing this on the front lawn, and the neighbors are looking at you. You just can't do it anymore,’” Stein recalls.

So she retreated to her bedroom, reveling in her elaborate reveries alone. As she grew older, the television shows changed—first General Hospital, then The West Wing—but her intense need to immerse herself in her imaginary world did not.

“There were periods in my life when daydreaming just took over everything,” she recalls. “I was not in control.” She would retreat into fantasy “any waking moment when I could get away with it. It was the first thing I wanted to do when I woke up in the morning. When I woke up in the night to go to the bathroom, it would be bad if I got caught up in a story because then I couldn't go back to sleep.” By the time she was 17, Stein was exhausted. “I loved the daydreams, but I just felt it was consuming my real life. I went to parties with friends, but I just couldn't wait to get home. There was nothing else that I wanted to do as much as daydreaming.

Convinced that she was crazy, she consulted six different therapists, none of whom could find anything wrong with her. The seventh prescribed Prozac, which had no effect. Eventually Stein began taking another antidepressant, Luvox, which, like Prozac, is also a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor but is usually prescribed for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Gradually she brought her daydreaming under control. Now age 39, she is a successful lawyer, still nervously guarding her secret world.

Gradually she brought her daydreaming under control. Now age 39, she is a successful lawyer, still nervously guarding her secret world.

The scientific study of people such as Stein is helping researchers better understand the role of daydreaming in normal consciousness—and what can happen when this process becomes unhealthy. For most of us, daydreaming is a virtual world where we can rehearse the future, explore fearful scenarios or imagine new adventures without risk. It can help us devise creative solutions to problems or prompt us, while immersed in one task, with reminders of other important goals.

For others, however, the draw of an alternative reality borders on addiction, choking off other aspects of everyday life, including relationships and work. Starring as idealized versions of themselves—as royalty, raconteurs and saviors in a complex, ever changing cast of characters—addictive daydreamers may feel enhanced confidence and validation. Their fantasies may be followed by feelings of dread and shame, and they may compare the habit to a drug or describe an experience akin to drowning in honey.

The recent discovery of a network in the brain dedicated to autobiographical mental imagery is helping researchers understand the multiple purposes that daydreaming serves in our lives. They have dubbed this web of neurons “the default network” because when we are not absorbed in more focused tasks, the network fires up. The default network appears to be essential to generating our sense of self, suggesting that daydreaming plays a crucial role in who we are and how we integrate the outside world into our inner lives. Cognitive psychologists are now also examining how brain disease may impair our ability to meander mentally and what the consequences are when we just spend too much time, well, out to lunch.

Videos in the Mind's Eye

Most people spend between 30 and 47 percent of their waking hours spacing out, drifting off, lost in thought, woolgathering, in a brown study or building castles in the air. Yale University emeritus psychology professor Jerome L. Singer defines daydreaming as shifting attention “away from some primary physical or mental task toward an unfolding sequence of private responses” or, more simply, “watching your own mental videos.” The 89-year-old Singer, who published a lyrical account of his decades of research on daydreams in his 1975 book, The Inner World of Daydreaming (Harper & Row), divides daydreaming styles into two main categories: “positive-constructive,” which includes upbeat and imaginative thoughts, and “dysphoric,” which encompasses visions of failure or punishment. Most people experience both kinds to some degree.

Singer defines daydreaming as shifting attention “away from some primary physical or mental task toward an unfolding sequence of private responses” or, more simply, “watching your own mental videos.” The 89-year-old Singer, who published a lyrical account of his decades of research on daydreams in his 1975 book, The Inner World of Daydreaming (Harper & Row), divides daydreaming styles into two main categories: “positive-constructive,” which includes upbeat and imaginative thoughts, and “dysphoric,” which encompasses visions of failure or punishment. Most people experience both kinds to some degree.

Other scientists distinguish between mundane musings and extravagant fantasies. Michael Kane, a cognitive psychologist at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, considers “mind wandering” to be “any thoughts that are unrelated to one's task at hand.” In his view, mind wandering is a broad category that may include everything from pondering ingredients for a dinner recipe to saving the planet from alien invasion. Most of the time when people fall into mind wandering, they are thinking about everyday concerns, such as recent encounters and items on their to-do list. More exotic daydreams in the style of James Thurber's grandiose fictional fantasist Walter Mitty—such as Mitty's dream of piloting an eight-engine hydroplane through a hurricane—are rare.

Most of the time when people fall into mind wandering, they are thinking about everyday concerns, such as recent encounters and items on their to-do list. More exotic daydreams in the style of James Thurber's grandiose fictional fantasist Walter Mitty—such as Mitty's dream of piloting an eight-engine hydroplane through a hurricane—are rare.

Humdrum concerns figured prominently in one study that rigorously measured how much time we spend mind wandering in daily life. In a 2009 study Kane and his colleague Jennifer McVay asked 72 U.N.C. students to carry PalmPilots that beeped at random intervals eight times a day for a week. The subjects then recorded their thoughts at that moment on a questionnaire. About 30 percent of the beeps coincided with thoughts unrelated to the task at hand. Mind wandering increased with stress, boredom or sleepiness or in chaotic environments and decreased with enjoyable tasks. That may be because enjoyable activities tend to grab our attention.

Intense focus on our problems may not always lead to immediate solutions. Instead allowing the mind to float freely can enable us to access unconscious ideas hovering underneath the surface—a process that can lead to creative insight, according to psychologist Jonathan W. Schooler of the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Instead allowing the mind to float freely can enable us to access unconscious ideas hovering underneath the surface—a process that can lead to creative insight, according to psychologist Jonathan W. Schooler of the University of California, Santa Barbara.

We may not even be aware that we are daydreaming. We have all had the experience of “reading” a book yet absorbing nothing—moving our eyes over the words on a page as our attention wanders and the text turns into gibberish. “People oftentimes don't realize that they're daydreaming while they're daydreaming; they lack what I call ‘meta-awareness,’ consciousness of what is currently going on in their mind,” Schooler says. Aimless rambling across the moors of our imaginings may allow us to stumble on ideas and associations that we may never find if we strive to seek them.

A Key to Creativity

Artists and scientists are well acquainted with such playful fantasizing. Orhan Pamuk, the Turkish novelist who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2006, imagined “another world,” to which he retreated as a child, where he was “someone else, somewhere else . .. in my grandmother's sitting room, I'd pretend to be inside a submarine.” Albert Einstein pictured himself running along a light wave—a reverie that led to his theory of special relativity. Filmmaker Tim Burton daydreamed his way to Hollywood success, spending his childhood holed up in his bedroom, creating posters for an imaginary horror film series.

.. in my grandmother's sitting room, I'd pretend to be inside a submarine.” Albert Einstein pictured himself running along a light wave—a reverie that led to his theory of special relativity. Filmmaker Tim Burton daydreamed his way to Hollywood success, spending his childhood holed up in his bedroom, creating posters for an imaginary horror film series.

Why should daydreaming aid creativity? It may be in part because the waking brain is never really at rest. As psychologist Eric Klinger of the University of Minnesota explains, floating in unfocused mental space serves an evolutionary purpose: when we are engaged with one task, mind wandering can trigger reminders of other, concurrent goals so that we do not lose sight of them. Some researchers believe that increasing the amount of imaginative daydreaming we do or replaying variants of the millions of events we store in our brain can be beneficial. A painful procedure in a doctor's office, for example, can be made less distressing by visualizations of soothing scenes from childhood.

Yet to enhance creativity, it is important to pay attention to daydreams. Schooler calls this “tuning out” or deliberate “off-task thinking.” In an as yet unpublished study, he and his colleague Jonathan Smallwood asked 122 undergraduates at the University of British Columbia to read a children's story and press a button each time they caught themselves tuning out. The researchers also periodically interrupted the students as they were reading and asked them if they were “zoning out” or drifting off without being aware of it. “What we find is that the people who regularly catch themselves—who notice when they're doing it—seem to be the most creative,” Schooler says. Such subjects score higher on a standard test of creativity, in which they are asked to describe all the uses of a common object, such as a brick; high scorers compile a longer and more creative list. “You need to have the mind-wandering process,” he explains, “but you also need to have meta-awareness to say, ‘That's a creative idea that popped into my mind. ’”

’”

The mind's freedom to wander during a period of deliberate tuning out could also explain the flash of insight that may pop into a person's head when he or she takes a break from an unsolved problem. Ut Na Sio and Thomas Ormerod, two researchers at the University of Lancaster in England, conducted a recent meta-analysis of studies of these brief reveries. They found that people who engaged in a mildly demanding task, such as reading, during a break from, say, a visual assignment, such as the hat-rack problem—in which participants have to construct a sturdy hat rack using two boards and a clamp—did better on that problem than those who did nothing at all. They also scored higher than those engaged in a highly demanding task—such as mentally rotating shapes—during the interval. Allowing our mind to ramble during a moderately challenging task, it seems, enables us to access ideas not easily available to our conscious mind or to combine these insights in original ways. Our ability to do so is now known to depend on the normal functioning of a dedicated daydreaming network deep in our brain.

The Mental Matrix of Fantasy

Like Facebook for the brain, the default network is a bustling web of memories and streaming movies, starring ourselves. “When we daydream, we're at the center of the universe,” says neurologist Marcus Raichle of Washington University in St. Louis, who first described the network in 2001. It consists of three main regions: the medial prefrontal cortex, the posterior cingulate cortex and the parietal cortex. The medial prefrontal cortex helps us imagine ourselves and the thoughts and feelings of others; the posterior cingulate cortex draws personal memories from the brain; and the parietal cortex has major connections with the hippocampus, which stores episodic memories—what we ate for breakfast, say—but not impersonal facts, such as the capital of Kyrgyzstan. “The default mode network is critical to the establishment of a sense of self,” Raichle says.

It was not until 2007, however, that cognitive psychologist Malia Fox Mason, now at Columbia University, discovered that the default network—which lights up when people switch from an attention-demanding activity to drifting reveries with no specific goal—becomes more active when people engage in a monotonous verbal task, when they are more likely to mind wander. In an experiment, participants were shown a string of four letters such as R H V X for one second, which was then replaced by an arrow pointing either left or right, to indicate whether the sequence should be read forward or backward. When one of the characters in the string appeared, subjects were asked to indicate its position (first, second, third or last, depending on the direction of the arrow). The more the participants practiced on each of the four original letter strings, the better they performed. They were then given a novel task, consisting of letter sequences they had not seen before. Activity in the default network went down during the novel version of the test. Subjects who daydreamed more in everyday life—as determined by a questionnaire—also showed greater activity in the default network during the monotonous original task.

In an experiment, participants were shown a string of four letters such as R H V X for one second, which was then replaced by an arrow pointing either left or right, to indicate whether the sequence should be read forward or backward. When one of the characters in the string appeared, subjects were asked to indicate its position (first, second, third or last, depending on the direction of the arrow). The more the participants practiced on each of the four original letter strings, the better they performed. They were then given a novel task, consisting of letter sequences they had not seen before. Activity in the default network went down during the novel version of the test. Subjects who daydreamed more in everyday life—as determined by a questionnaire—also showed greater activity in the default network during the monotonous original task.

Mason did not directly measure mind wandering during the scans, however, so she could not determine exactly when subjects were “on task” and when they were daydreaming. In 2009 Smallwood, Schooler and Kalina Christoff of the University of British Columbia published the first study to directly link mind wandering with increased activity in the default network. The researchers scanned the brains of 15 U.B.C. students while they performed a simple task in which they were shown random numbers from zero to nine. Each was asked to push a button when he or she saw any number except three. In the seconds before making an error—a key sign that an individual's attention had drifted—default network activity shot up. Periodically the investigators also interrupted the subjects and asked them if they had zoned out. Again, activity in the default network was higher in the seconds before the moment they were caught in the act. Notably, activity was strongest when people were unaware that they had lost their focus. “The more complex your mind-wandering episode is, the more of your mind it's going to consume,” Smallwood says.

In 2009 Smallwood, Schooler and Kalina Christoff of the University of British Columbia published the first study to directly link mind wandering with increased activity in the default network. The researchers scanned the brains of 15 U.B.C. students while they performed a simple task in which they were shown random numbers from zero to nine. Each was asked to push a button when he or she saw any number except three. In the seconds before making an error—a key sign that an individual's attention had drifted—default network activity shot up. Periodically the investigators also interrupted the subjects and asked them if they had zoned out. Again, activity in the default network was higher in the seconds before the moment they were caught in the act. Notably, activity was strongest when people were unaware that they had lost their focus. “The more complex your mind-wandering episode is, the more of your mind it's going to consume,” Smallwood says.

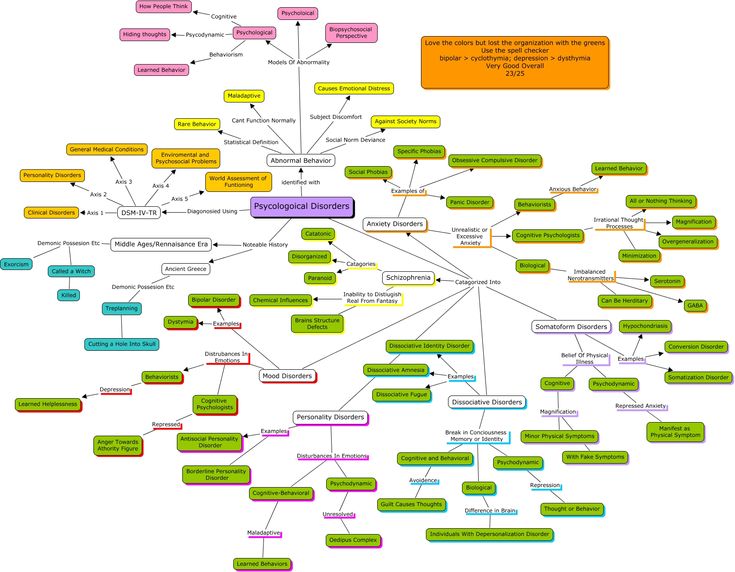

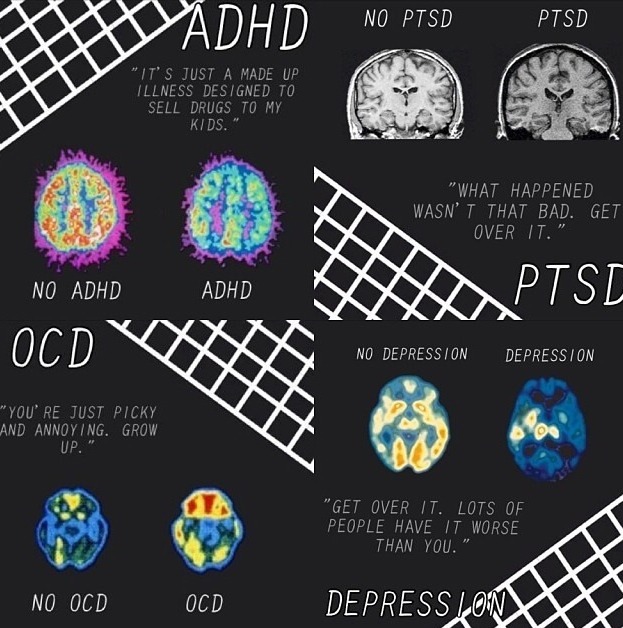

Defects in the default network may also impair our ability to daydream. A range of disorders—including schizophrenia and depression—have been linked to malfunctions in the default network. In a 2007 study neuroscientist Peter Williamson of the University of Western Ontario found that people with schizophrenia have deficits in the medial prefrontal cortex, which is associated with self-reflection. In patients experiencing hallucinations, the medial prefrontal cortex dropped out of the network altogether. Although the patients were thinking, they could not be sure where the thoughts were coming from. People with schizophrenia daydream normally most of the time, but when they are ill, “they often complain that someone is reading their mind or that someone is putting thoughts in their head,” Williamson says.

A range of disorders—including schizophrenia and depression—have been linked to malfunctions in the default network. In a 2007 study neuroscientist Peter Williamson of the University of Western Ontario found that people with schizophrenia have deficits in the medial prefrontal cortex, which is associated with self-reflection. In patients experiencing hallucinations, the medial prefrontal cortex dropped out of the network altogether. Although the patients were thinking, they could not be sure where the thoughts were coming from. People with schizophrenia daydream normally most of the time, but when they are ill, “they often complain that someone is reading their mind or that someone is putting thoughts in their head,” Williamson says.

On the other hand, those who ruminate obsessively—rehashing past events, repetitively analyzing their causes and consequences, or worrying about all the ways things could go wrong in the future—are well aware that their thoughts are their own, but they have intense difficulty turning them off. The late Yale psychologist Susan Nolen-Hoeksema did not believe that rumination is a form of daydreaming, which she defined as “imagining situations in the future that are largely positive in tone.” Nevertheless, she had found that in obsessive ruminators, who are at greater risk of depression, the same default network circuitry turns on that is activated when we daydream.

The late Yale psychologist Susan Nolen-Hoeksema did not believe that rumination is a form of daydreaming, which she defined as “imagining situations in the future that are largely positive in tone.” Nevertheless, she had found that in obsessive ruminators, who are at greater risk of depression, the same default network circuitry turns on that is activated when we daydream.

These ruminators—who may repeatedly scrutinize faux pas, family issues or lovers' betrayals—have trouble switching off the default network when asked to focus mentally on a neutral image, such as a truckload of watermelons. They may spend hours going over some past incident, asking themselves how it could have happened and why they did not react differently and end up feeling overwhelmed instead of searching for solutions. Experimental studies have shown that positive distraction—for example, exercise and social activities—can help ruminators reappraise their situation, as can techniques for cultivating mindfulness that teach individuals to pay precise attention to activities such as breathing or walking, rather than to thoughts. Yet people who daydream excessively may have the same problems ignoring their thoughts once they get going. Indeed, extreme daydreamers find their private world so difficult to escape that they describe it as an addiction—one as enslaving as heroin.

Yet people who daydream excessively may have the same problems ignoring their thoughts once they get going. Indeed, extreme daydreamers find their private world so difficult to escape that they describe it as an addiction—one as enslaving as heroin.

When Daydreaming Becomes a Drug

“I'm like an alcoholic with an unlimited supply of booze everywhere I go,” says Cordellia Amethyste Rose. A 33-year-old woman in Oregon, she started an online forum called Wild Minds (http://wildminds.ning.com) for people who simply cannot stop daydreaming. Since childhood, Rose has conjured up countless imaginary characters in ever changing plots. “They've grown right along with me, had children—some have died,” she says. The deeper she delved into her virtual world, though, the more distressed she became. “I couldn't pay attention for more than a split second. I would look at a book and zone out after every word.” Even so, she found her invented companions more compelling than anyone real. “I've learned to socialize internally with fictional characters I get along with,” she says. She could engage them in intellectual debate, whereas “socializing with outside people frustrates me. They all want to talk about the silliest things.”

“I've learned to socialize internally with fictional characters I get along with,” she says. She could engage them in intellectual debate, whereas “socializing with outside people frustrates me. They all want to talk about the silliest things.”

Rose says that she has no friends, but on Wild Minds she has found her peers. Many people posting to the site express relief that they have found others like themselves, emerging from a cocoon of loneliness and shame to share their experiences: misdiagnoses, lack of understanding from families and therapists, and rituals like the one described by a quiet girl who spends “endless hours” swaying in a rocking chair listening to music, daydreaming her life away. “It's like a drug, poisoning and destroying your life,” says one anonymous fantasist, who admits to bingeing for days on a story line. “It's even worse because an addict can put a drug down and walk away. You can't put down your mind and walk away from it.”

Yet few of the members of the Wild Minds community would abandon their mental creations, even if they could. One hardworking nurse revels in imagined adventures starring a fictional medieval Queen Eleanor of Scotland, a skilled horsewoman with four concurrent husbands, who practices a made-up religion and is “a genius in both state and battle-craft ... trained in martial arts and is always inventing marvelous things.” Like Thurber's fictional fantasist, Queen Eleanor's creator spends a lot of time mentally rescuing disaster victims from burning buildings or “abseiling over cliffs, being winched in and out of helicopters with casualties.”

One hardworking nurse revels in imagined adventures starring a fictional medieval Queen Eleanor of Scotland, a skilled horsewoman with four concurrent husbands, who practices a made-up religion and is “a genius in both state and battle-craft ... trained in martial arts and is always inventing marvelous things.” Like Thurber's fictional fantasist, Queen Eleanor's creator spends a lot of time mentally rescuing disaster victims from burning buildings or “abseiling over cliffs, being winched in and out of helicopters with casualties.”

She has also documented her preposterous plots for independent biopsychologist Cynthia Schupak, a researcher with a single-minded mission to understand compulsive daydreamers, who treated Rachel Stein and described her ordeal in a journal article published in 2009. Schupak is convinced that compulsive daydreaming is a unique disorder, characterized by an inability to control it and the deep distress over the condition. “Everyday escapist fantasy is fine and dandy, but this syndrome is different,” she says.

In 2011 Schupak and psychology researcher Jayne Bigelsen published a study of 90 compulsive fantasizers—75 women and 15 men—garnered from Web sites such as the Yahoo group Maladaptive Daydreamers (http://health.groups.yahoo.com/group/maladaptivedaydreamers). The self-selected respondents devoted between 12.5 and 99 percent of their waking hours to daydreaming, and 79 percent of them engaged in physical movement such as pacing while doing so. Many said everyday activities paled by comparison with their vivid inner worlds, and some drifted in and out of their alternative reality in the midst of conversation. Typically they reported that their daydreams made them feel comforted or confident “because it's me, just magnified,” as one subject put it. Nevertheless, 88 percent said they anguished over the amount of time spent fantasizing, even though most were gainfully employed or students. Nine percent had no friends or meaningful relationships, and 82 percent kept their daydreaming habit hidden from almost everyone.

Some evidence suggests that maladaptive daydreaming could be a distinctive disorder. Eleven years ago clinical psychologist Eli Somer of the University of Haifa in Israel recounted cases of six people consumed by fantasy lives packed with sadism and bloodshed. All had suffered some form of childhood trauma. One had been sexually molested by her grandfather. Another described his father as a brutal man who humiliated and physically abused family members.

Somer believes that this mental activity emerged as a coping mechanism to help his patients deal with intolerable or inescapable realities. When their enhanced ability to conjure up vivid imagery is under control and does not interfere with social or academic success, “the phenomenon should probably be classified as a talent rather than a disorder,” he says. Attitude may also be important.

Singer, who grew up during the Great Depression and had no formal musical training, he says, entertained himself through childhood and adolescence with the imaginary achievements of “Singer the Composer,” an alter ego who wrote a complete repertoire of classical music, including operas and an unfinished Seventh Symphony. He does not consider his inner adventures harmful but rather sees them as a boredom-banishing sport—one that likely helped to propel him into his profession.

He does not consider his inner adventures harmful but rather sees them as a boredom-banishing sport—one that likely helped to propel him into his profession.

Is Your Mind Wandering Out of Control?

How do you know when you have tipped over from useful and creative daydreaming into the netherworld of compulsive fantasizing? First, notice whether you are deriving any useful insights from your fantasies. “The proof is in the pudding,” Schooler says. “Creative individuals—artists, scientists, and so on—oftentimes report ideas that have occurred to them during daydreams.” Second, it is important to take stock of the content of your daydreams. To distinguish between beneficial and pathological imaginings, he adds, “Ask yourself if this is something useful, helpful, valuable, pleasant, or am I just rehashing the same old perseverative thoughts over and over again?” And if daydreaming feels out of control, then even if it is pleasant it is probably not useful or valuable.

Whether or not mind wandering causes distress often depends on the context, Kane observes. “We argue that it's not inherently good or bad; it all depends on what the goals of the person are at the time.” It may be perfectly reasonable for a scientist to mentally check out in the midst of a repetitive experiment. And a novelist who can publish her reveries is clearly putting them to good use.

“Happily, a lot of what we do in life doesn't require that much concentration,” Kane says. “But there are going to be some contexts in which it is costly. Does the cost to your activity, to your reputation, to your performance, overwhelm the benefit that you may be getting from those thoughts? You can imagine situations where it is so costly that there's no thought you could be having that's worth it,” he says, pausing to consider the possibilities. “You've crossed the line,” he concludes, “if you walk into traffic and get killed.”

The Author

JOSIE GLAUSIUSZ is a science journalist who has written for Nature, National Geographic and Discover. She writes the weekly On Science column for the American Scholar and is author of Buzz: The Intimate Bond between Humans and Insects (Chronicle, 2004).

She writes the weekly On Science column for the American Scholar and is author of Buzz: The Intimate Bond between Humans and Insects (Chronicle, 2004).

Further Reading

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty. James Thurber in My World and Welcome to It. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1937.

The Inner World of Daydreaming. Jerome L. Singer. Harper and Row, 1975.

Maladaptive Daydreaming: A Qualitative Inquiry. Eli Somer in Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, Vol. 32, Nos. 2–3; Fall 2002.

Rethinking Rumination. Susan Nolen-Hoeksema, Blair E. Wisco and Sonja Lyubomirsky in Perspectives on Psychological Science, Vol. 3, No. 5, pages 400–424; 2008.

Compulsive Fantasy: Proposed Evidence of an Under-Reported Syndrome through a Systematic Study of 90 Self-Identified Non-normative Fantasizers. Jane Bigelsen and Cynthia Schupak in Consciousness and Cognition, Vol. 20, No. 4, pages 1634–1648; December 2011.

20, No. 4, pages 1634–1648; December 2011.

The Costs and Benefits of Mind-Wandering: A Review. Benjamin W. Mooneyham and Jonathan W. Schooler in Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, Vol. 67. No. 1, pages 11–18; March 2013.

This article was originally published with the title "Living in an Imaginary World" in SA Special Editions 23, 1s, 70-77 (January 2014)

doi:10.1038/scientificamericancreativity1213-70

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)

The Author

JOSIE GLAUSIUSZ is a science journalist who has written for Nature, National Geographic and Discover. She writes the weekly On Science column for the American Scholar and is author of Buzz: The Intimate Bond between Humans and Insects (Chronicle, 2004).

How to get a person out of a fantasy world if they don't want to

- John Kelly

- BBC News

Image copyright, Getty Images

One day, when she was five, Daya Bharj told her brother that she didn't want to play with him anymore. Now she will play with herself - in her imagination.

Now she will play with herself - in her imagination.

Daya was lying on the sofa in the living room and staring at the ceiling. She imagined a little boy, about her own age, running across the field. He ran to the plane, which made an emergency landing, climbed inside and sat on one of the seats in the cockpit. nine0011

His hands were too small to fasten his seat belt. But it was Dai's fantasy, and she invented another hero who helped the boy fasten his seat belt.

The boy looked like Peter Pan, and the other one who strapped him to the seat looked like Captain Hook. Then Daya imagined the pilot starting the engine. The plane took off and disappeared into the clouds.

Daya found that she really enjoyed fantasizing. She could replay in her mind the scenes she had already imagined, adding new details or deleting what she did not like. nine0011

That day she spent two hours lying on the couch. The rest of the family thought she was asleep, but her eyes were wide open.

13 years have passed, and daydreams continued. The little boy grew up with Daya, but his life was much more eventful.

Image copyright Getty Images

As Daya replayed the opening scene of her fantasy over and over in her mind, she refined many details, leaving only what she liked.

At first, the boy's name was Peter, but she soon changed his name to Light. The heavyset man who fastened Light's seat belts no longer looked like Captain Hook. This character became the brother of Light, Dai's dream hero.

"Light is me in that world," she says. He resembles Daya in appearance, being about her height, but unlike her, he has matted blond hair, very pale skin, and a scarred body. (Daya watched a lot of Japanese cartoons, and Light became more and more like a character from manga comics. Actually, she borrowed the name for him from the anime series "Suicide Note".)0011

- New reality: how Pokémon became more popular for porn

- Do you like daydreaming? It turns out that this is useful

- Is our free will an illusion?

- Why doesn't Japan ban porn comics with children?

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

End of story Podcast

Light is the ideal that Dai herself aspires to: he is kind, gentle and sweet. Today he is 18, like Dae, but his voice still sounds like a boy's.

When Light was young, he was kidnapped from his family. His rich father is the head of the "Syndicate" (or "Organization"), and the kidnappers demanded a ransom for Light.

The boy was handed over from one kidnapper to another. Sometimes he begged to be let go, sometimes he tried to run away. But here's the twist: Light's kidnapping was originally organized by his own father. nine0011

Light's hardship contrasts with the happy, peaceful, secure life that Dai's family leads in the Wembley area of north London.

"I think I missed the experience," she says. "I read different books, and in all of them the child had a terrible life. You never meet a child who grew up in a wonderful family and eventually became a hero."

Daya continued to live in dreams all the time she was in elementary school, and when she moved to middle school, her fantasies became even more intense. She was bullied in class, and at some point she even had to transfer to another school. She hated the real world and escaped from it in the world of her fantasies. nine0011

Image copyright Getty Images

"I think I needed friendship," she says.

Every day after school, she went to the park next door, continuing to improve Light's story. She created plot branches, she could get rid of this or that character, but then change her mind and bring him back, and the plot continued to develop as if nothing had happened.

Her favorite scenes replayed over and over again in her head. When she was daydreaming, she needed to move, she paced back and forth or swung on a swing. nine0011

When she was daydreaming, she needed to move, she paced back and forth or swung on a swing. nine0011

She put on her headphones and listened to her favorite songs, which served as the soundtrack to an imaginary story, and the action unfolded to the rhythm of the bass or drums.

Sometimes Daya borrowed stories from books and TV programs she read. Fantasies became more and more detailed ... and darker.

Light's first kidnapper was named Kilgrave (the name was borrowed from the Jessica Jones comics). Kilgrave kept Light chained up and beat him when he tried to run.

Light develops a somewhat friendly relationship with Kilgrave's daughter Lana. Then Kilgrave decided that Light was more trouble than good and sold him to those who were vying for influence with Light's father's organization.

All members of this group had a scorpion tattoo (Daya borrowed this detail from Alex Ryder's youth spy novels).

Image copyright Getty Images

They cut off Light's finger and sent it to his family. But of course, Light's father wasn't in the least bit moved by this, because he was the one behind the original kidnapping of his own son. nine0011

But of course, Light's father wasn't in the least bit moved by this, because he was the one behind the original kidnapping of his own son. nine0011

The head of the family syndicate wanted to make sure that the organization would be inherited by Light's brutal brother, now named Kyle. And when Light's finger arrived in the mail, the father told the police to stop looking for his son.

Since the ransom could not be obtained, those who held Light in captivity began to think about how to kill him. But then Lana appeared, who managed to gain the trust of the group. "I'll help you run," she told Light.

She led him through a sewer pipe (resembling the pipe Dia had seen near a playground in their area), and the couple managed to escape and hide in a house no one knew about. nine0011

Light woke up the next morning after escaping, chained to his bed. "What's going on?" he asked Lana. "I thought you wanted to help me!" And then Lana admitted that she herself was going to get a ransom for him.

Light was in despair at such a betrayal. But after several months in Lana's captivity, Light and the girl formed a close bond.

Finally Lana agreed not to sell it. When one day they were standing on the roof of the house, Lana confessed her love to Light. But Light rejected her. He didn't feel anything like that for Lana at all, and besides, I'm gay, he explained to the girl. Lana was furious. nine0011

She pushed Light off the roof and he fell to the ground, blaming himself for once again trusting someone who didn't deserve it...

Image copyright, Getty Images

Dai's parents were worried about her. They knew that she was bullied at school, and now the daughter began to behave very strangely. She always wanted to be alone.

Every day after school she spent hours pacing up and down or swinging, completely lost in daydreaming. Sometimes she resorted to tricks to avoid going to school and be alone with Light and Lana. nine0011

nine0011

Her academic performance suffered because of this. She couldn't concentrate on anything for long. If she watched a TV show, she would run away from the screen after five minutes because she wanted to try using the joke or phrase she heard in her fantasies.

Meanwhile, Light's story took a new direction.

Falling from the roof, he survived, but lost his memory after hitting his head. He tried to remember who he really was and what had happened to him.

And then he met another boy, about his age, with a scorpion tattoo. Light did not remember what the scorpion meant, but something skipped a beat and he approached the boy with the tattoo. He called himself L.

In many ways, L. is the exact opposite of Light. He rides a motorcycle, he is gloomy and confident, and generally a bad boy. Besides, in Dai's eyes, he is the perfect boyfriend.

Mutual attraction immediately arose between the boys. L. offered to help Light find his former self. They became friends and have always been together.

L. offered to help Light find his former self. They became friends and have always been together.

But L never told Light that he was in a gang of scorpions. And Light couldn't remember why this tattoo looked so familiar. nine0011

But then he remembered. The scorpion tattoo gang wanted to kill me! How could you do this to me? - he begins to interrogate L. How could you be a member of the gang that kidnapped me?

L. begged him to listen, but all in vain - Light left him in anger and vowed not to see L again.

Photo credit, Getty Images them the last straw.

Before that, she had always immersed herself in her fantasies by herself, in secret, but from about the age of 16-17 she began to talk aloud about what was happening in her head. nine0011

I'm not going crazy, she told her mother and father and tried to talk about her fantasies, plots and main characters. But her parents did not understand her. Is she too old to have imaginary friends?

Is she too old to have imaginary friends?

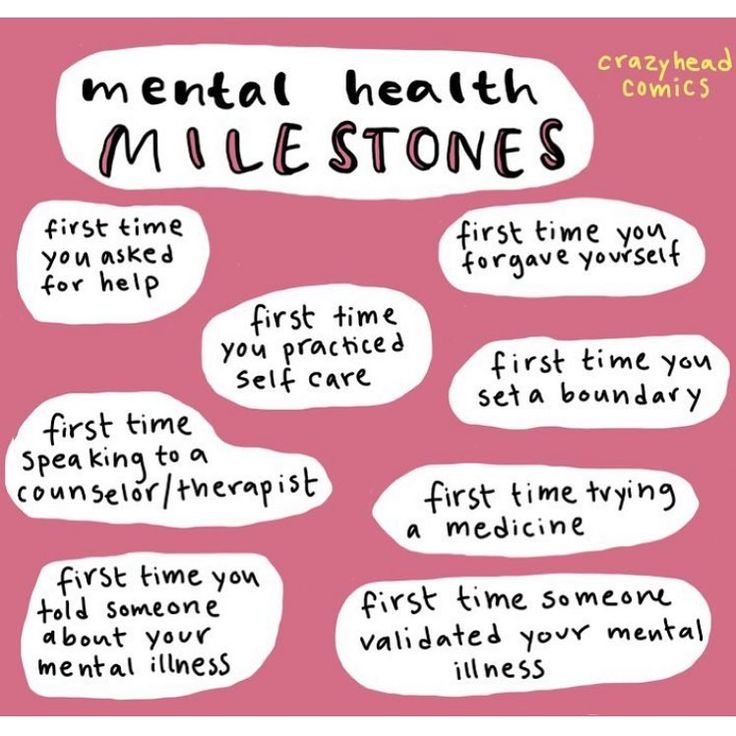

Daya was sent to psychotherapists and psychologists. But they did not come to a consensus about what was happening to her.

Some thought she simply had a wild imagination. Others thought it might be obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). One specialist suggested schizophrenia, but Daya objected: "I understand that this is not really." nine0011

The school psychotherapist asked if she identified with Light because deep down she always wanted to be a boy. "Not!" Daya snapped.

In general, experts could not find the answer. One day, Daya opened her computer and typed in the Google search box: "too many daydreams." And I quickly realized that she was not the only one.

Meanwhile, Light's memory began to return. He remembered more and more details about his former life - including about Kilgrave and his father. But he didn't remember a few things, like Lana pushing him off the roof. nine0011

nine0011

One day Light was found by CIA agents (sometimes these agents work for another agency - it depends on Dai's mood). "Where have you been?" they began to ask. "We've been looking for you since you were kidnapped!"

Light told them what he remembered. The agents were impressed by how Light was able to explain the essence of the case, which they had been struggling to solve for so many years. And they invited him to work together on the investigation of various crimes.

But when Light came to their headquarters, he was dumbfounded and furious to see L. Isn't L. a gang member with scorpion tattoos? nine0011

Image copyright, Getty Images

L. explained that when Light left, he was deeply disappointed and realized that he was going down the wrong path in life. He decided to get away from the bad guys and join the good ones.

Light and L. became friends again and began to solve crimes together, realizing that they needed each other. They began to investigate the activities of the scorpion gang and came across Lana, who was still listed there.

They began to investigate the activities of the scorpion gang and came across Lana, who was still listed there.

Lana felt jealous when she saw L. and Light together, she immediately realized that there was something between them. She began to tell Light that he should take revenge on his father and kill him. But Light by that time had other priorities. nine0011

He tracked down Kilgrave and let him capture him again. But when Kilgrave took him to his house and tried to chain him to the wall, Light wound a chain around Kilgrave's neck and strangled him.

Lana, having learned that Light killed her father, vowed revenge.

"Now she has become his main enemy," says Daya. "And Light is planning to kill his father as well, so I'm at a crossroads now - I don't know how to do all this yet."

In 2002, Eli Somer, an Israeli doctor who worked with six teenage victims of domestic violence, noticed that they all had something in common. nine0011

nine0011

In order not to be haunted by memories and emotional pain, each of them escaped into a carefully thought-out fantasy world, where they could stay for up to eight hours at a time.

Some imagined the ideal self living in an ideal world. Others created whole relationships in their heads, including romantic ones. One imagined leading a guerrilla war. The other conjured up images of football and basketball games in which he put on an outstanding performance.

Their fantasy stories often featured themes of captivity, escape and rescue, such as being kept chained in a cave or leading a prison riot. nine0011

And these were not just dreams. Not to mention how much time they spent in dreams, Eli Somer's patients had difficulty controlling their fantasies. This negatively affected their work, study, social ties.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Somer, a professor of clinical psychology at the University of Haifa, described his findings in a paper describing "compulsive daydreaming" (NG) as excessive daydreaming that replaces a person's normal life and interferes with normal interpersonal and professional functioning individual. nine0011

nine0011

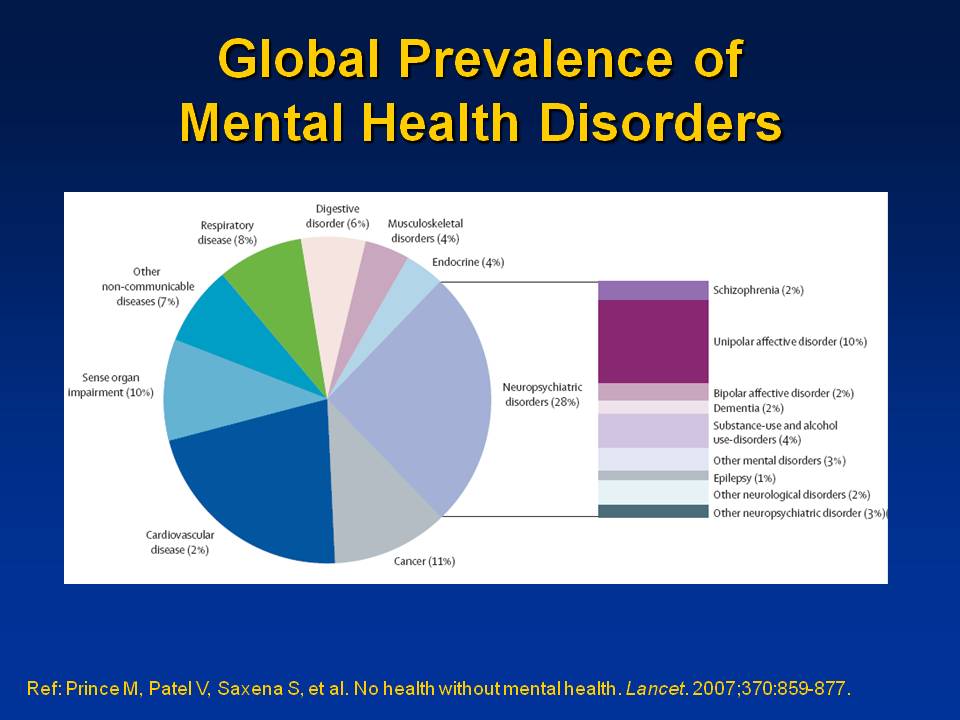

Researchers from the University of Lausanne (Switzerland) and Fordham University in New York also conducted their own research on NG. A total of 10 papers on obsessive dreams have been published, two have been approved for publication and two more have been submitted for peer review.

These studies suggest that most people with NC are not victims of violence. Some of them spend up to 60% of their waking time daydreaming.

The results of these studies are very popular - not in academic circles, but among daydreamers who search Google for an explanation of what is happening to him. There are many blogs, newsletters, and YouTube videos on the subject, and the online NG community is growing and thriving. nine0011

Daya was one of those who found the term online, and she said it was like a revelation. "When I discovered that this had a name, I experienced a surge of vitality: I'm not crazy, it actually exists!" she says.

However, her "compulsive daydreaming" is a self-diagnosis.

This disorder is not included in the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Statistical Manual of Diagnosis of Mental Disorders. The British Psychological Society says that he "does not have a definite position on obsessive daydreaming, as this disorder is not officially recognized." nine0011

Some psychologists think that NG is not a very good term. Skeptics say it runs the risk of mistaking normal behaviors as psychiatric symptoms. It also doesn't help the case to consider NG as a separate disorder rather than a by-product of, say, depression or OCD.

"The problem is not the dreams themselves, the problem is why people dream so much that it starts to interfere with their lives," argues Roderick Orner, a visiting professor of psychology at Lincoln University (USA). other problems". nine0011

Image copyright, Getty Images

Eli Somer says the term NG (now preferring "fantasy disorder") is only 15 years old and needs more research to be included in mainstream diagnostic references.

However, he says, even if this disorder is related to others such as OCD or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), it is very different from them.

For example, he says, mental activity during NG is not meaningless and not stressful, as in OCD, it is satisfying, these fantasies are important for daydreamers. nine0011

"People with NC describe fantasy craving as something similar to other pathological addictions - gambling, the Internet, promiscuous sexual behavior," Somer points out.

He believes that eventually the NC syndrome will be officially recognized as a behavioral addiction.

In 2014, Texas student Cyane Reed started a Change.org petition calling for the American Psychiatric Association to recognize NC as a disorder.

Without official recognition, Reid says, those who suffer from the negative consequences of their fantasizing simply have nowhere to go with their problem, no one to turn to, except for online communities, whose members often "connive" NG. nine0011

nine0011

"Some people don't want to get rid of it," she explains. "It's like a lifeline for them."

"But those who want to get rid of it, like me, for example, feel abandoned to their fate. I want to lead a fruitful life and do not want to spend an hour a day daydreaming. This is a whole hour that I could spend on something other".

Image copyright Getty Images

Dia and I are sitting in a cafe near her house. "This is the first time I'm telling someone my whole story," she admits. She seems to be relieved by this. nine0011

We've been talking for an hour, but I don't always have her attention. For example, when the sound of a cappuccino machine was heard from behind the counter, Daya, as she later said, imagined that it was machine gun fire, and tried to come up with a scene in which Light riddled Kilgrave with bullets.

Sometimes daydreams interfere with real life. Daya tried dating guys, but none of them could compare to L.

"No one could compare, and in the end I ended the relationship. I was not interested. And it's sad, because I feel: I need a real relationship in a real life." nine0011

But ever since Daya found NG sites on the Internet, she has learned to get the better of the fantasies that are trying to dominate her life.

She listens to those songs that she has not yet used in the plots of her dreams. When she took her matriculation exams, she forced Light to do the same, placing him under the supervision of a tutor who constantly reminded him to focus. (At first, the tutor was young and handsome, and Light immediately fell in love with him, but Daya quickly made the tutor an older man.)

And it all seemed to work, because Daya enrolled in a writing course at Brunel University in London. Light also does not lag behind, studying drawing and dancing at the evening department, while he spends most of his time working for the CIA.

I wonder if she would like to turn her fantasies into a book.

Daya says that she tried to start writing a couple of times. But things did not go beyond the plan. And it turned out so stretched out that she stopped, stunned by the enormity of the task before her. nine0011

But this is not the main problem. "It's always been hard for me to write it all down because I don't know what's going to happen at the end," she explains. "And I hope I never get to the end, to be honest."

Once upon a time, the thought that her dreams would continue into adulthood frightened Daya. She wanted to grow out of it. But now she believes fantasy is a useful tool for creative projects like writing.

"I want this to last for the rest of my life," she says. "I hope it never stops." nine0011

Image copyright, Getty Images

***

Everyday fantasy: how and why do we imagine another life?

Everyday fantasizing is our reaction to some event in the outside world. It is woven into the context of everyday life, and we do it all the time, but we do not pay much attention to such fantasies. And we are very surprised when we hear that such an occupation can be called a scientific term, that it can be explored.

It is woven into the context of everyday life, and we do it all the time, but we do not pay much attention to such fantasies. And we are very surprised when we hear that such an occupation can be called a scientific term, that it can be explored.

As a rule, having become interested in this topic, a person begins to observe himself, and he himself wants to share: “It happens to me like this, like this, and also like this.” Several hundred people filled out an anonymous questionnaire on daily fantasy, others gave anonymous interviews. As a result, we managed to collect a bank of the most common fantasies. nine0011

Revenge or forgive

We studied the reactions of adults who experienced something unpleasant in transport (for example, they stepped on their feet). Some "quench" their anger and find other ways to calm down, while others, like a child, imagine an alternative development of the situation.

Suppose one woman stepped on the foot of another with a sharp heel. And the second one imagines how the "offender" comes out onto the platform, and she, the "victim", beats her with a whip, punishes her. Another option: the man stepped on the girl's foot and called her names at the same time - because she squealed. The girl can imagine that in fact he behaved like a gentleman, was horrified by his act, apologized, bowed and showed himself as well as possible. nine0011

And the second one imagines how the "offender" comes out onto the platform, and she, the "victim", beats her with a whip, punishes her. Another option: the man stepped on the girl's foot and called her names at the same time - because she squealed. The girl can imagine that in fact he behaved like a gentleman, was horrified by his act, apologized, bowed and showed himself as well as possible. nine0011

Men undress, women change

Sometimes adults, like children, fantasize for fun because they are bored. For example, a person is riding the subway, and he has neither a newspaper nor a book, but there is energy inside. He begins to look at those who are sitting opposite. Both men and women (not all, but many) often indulge in fantasizing about those they are looking at.

Adults also make imaginary friends, but they rarely talk about it - they are afraid that they will be mistaken for mentally ill

Women very often "dress up" those who, in their opinion, are poorly or tastelessly dressed. At the same time, they mentally try on the clothes of others on this person. It's a bit like how girls cut out paper dolls and put different paper dresses on them.

At the same time, they mentally try on the clothes of others on this person. It's a bit like how girls cut out paper dolls and put different paper dresses on them.

Men often - much more often than women - come up with fantasy biographies of people sitting opposite - complex, thoughtful, with many details. Men are very fond of mentally undressing women and imagining what they look like without clothes. Women do not admit to such fantasies in relation to men. nine0011

What do Carlson and Angelina Jolie have in common?

Day-to-day fantasizing helps us make up for what we lack in real life. Children create imaginary friends. A famous example is Carlson, who lives on the roof. Some children invent a friend for themselves so that it is not scary to walk through an empty yard. It is usually someone big and strong—sometimes a human, sometimes an animal. “When I’m with him, I’m not afraid, if anything, he will help,” “he walks next to me, here, on the left side,” says the child. Young children are less self-aware, and according to them, imaginary friends appear to them themselves. Older children say: "When I want, he will appear", "I call him." nine0011

Young children are less self-aware, and according to them, imaginary friends appear to them themselves. Older children say: "When I want, he will appear", "I call him." nine0011

Adults also make imaginary friends, but they rarely talk about it - they are afraid that they will be taken for mentally ill. People very often have imaginary conversations with absent or deceased loved ones. Many come up with an ideal partner for themselves, hoping that such a person can meet in real life.

Young spouses have similar fantasies. If it seems to a woman that her husband is not tender, affectionate and attentive enough, a “understudy” may appear in her fantasies - an imaginary husband No. 2 with a romantic name, for example, Robert or Albert. The woman mentally "puts" this Albert on an empty chair and mentally talks to him. At the same time, her real husband sits nearby and reads a newspaper. Men, instead of their wife, imagine Angelina Jolie or another attractive celebrity, and do this quite often. They explain this by saying that "it's more fun that way." The wife does not notice this and thinks that all emotions are intended only for her. nine0011

They explain this by saying that "it's more fun that way." The wife does not notice this and thinks that all emotions are intended only for her. nine0011

Men and women fantasize differently

Day-to-day fantasizing has many functions. For example, you can plan and imagine the future: thinking about an upcoming meeting, a person can “lose” in his head the possible options for how it will go. People are almost always aware of such fantasizing, they consider it acceptable. In the same way, you can "process" the past.

It is important that in the real world it is interesting for a person to love something, to be good at something

Men in such cases turn out to be more simple-hearted: they go over the events in the form in which they really happened. If there was something bad, they figure out what else they could do. Women also do this, but unlike men, they tend to turn even good things into beautiful ones. Thinking about yesterday's reception, at which an important person for her could not be present, a woman can imagine that he did come. And thus create a picture even more wonderful than it was in reality. nine0011

And thus create a picture even more wonderful than it was in reality. nine0011

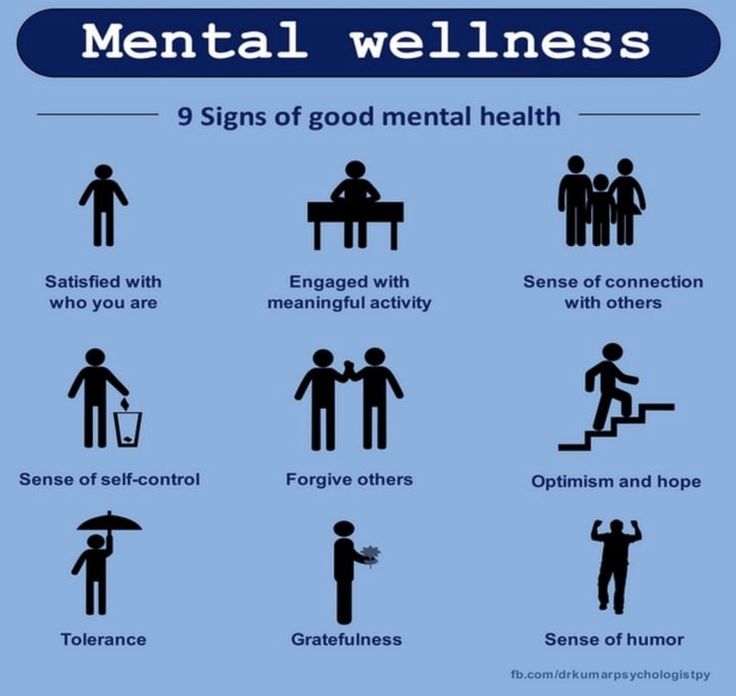

Staying in touch with reality

Being aware of our fantasies, we discover wonderful possibilities for ourselves: since the invented is our own creation, we can control it, we can try to better design the future or better process the past. Instead of remembering again and again how terrible everything turned out, you can imagine an option in which we behaved much better than in reality. This does not mean that we erase memory and replace it with imaginary ideal pictures. This means that we have the opportunity to compare the real version with the fictional one, to draw conclusions. Such "fantasy" work is very useful. nine0011

Sometimes children and adults "fly away" in fantasy for a long time. This usually happens when something really goes wrong for them in the real world. Therefore, it is extremely important that in the real world it is interesting for a person, that he loves something, that he does something well.