Mdd vs bipolar

Bipolar Disorder And Depression: Understanding The Difference

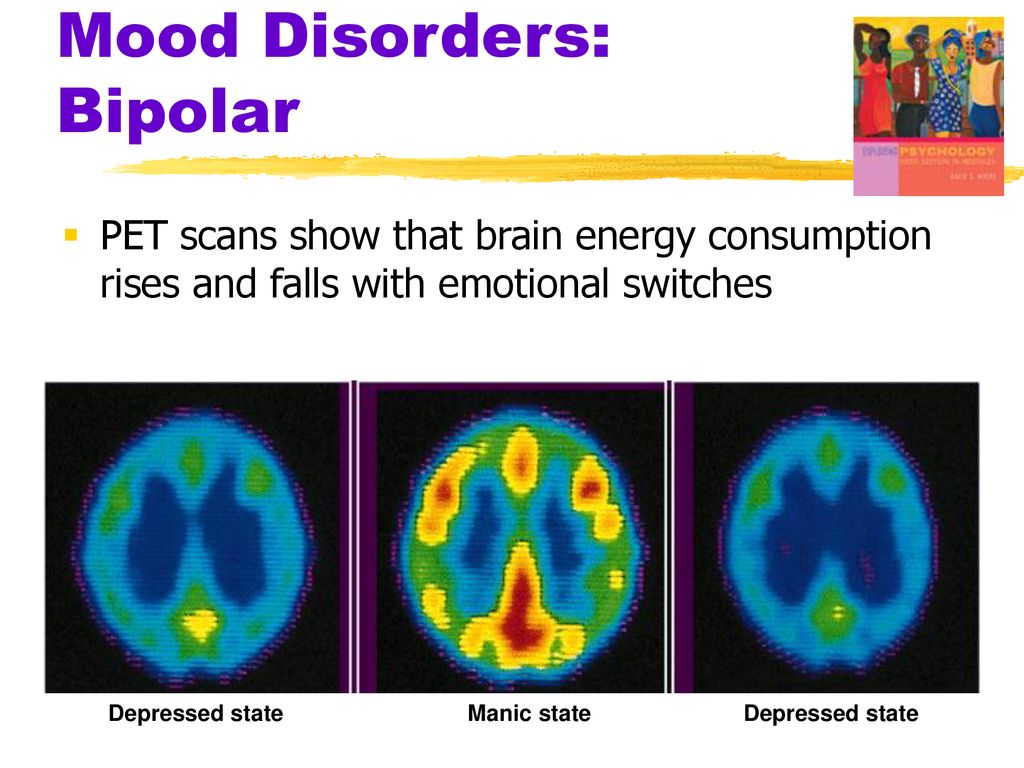

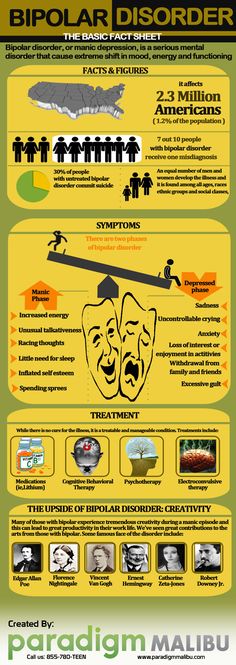

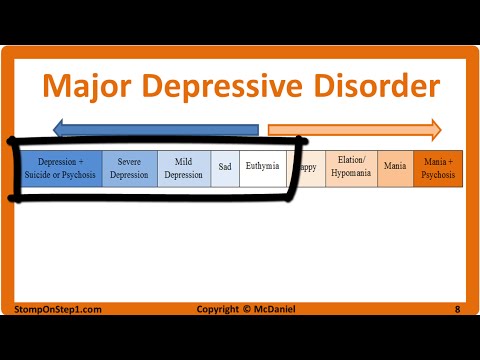

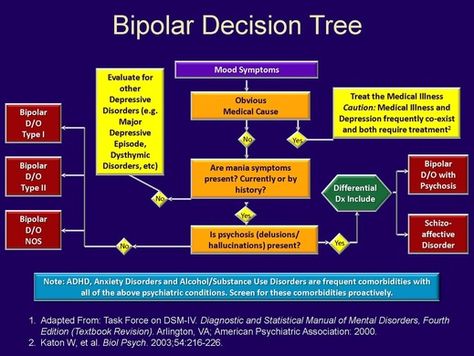

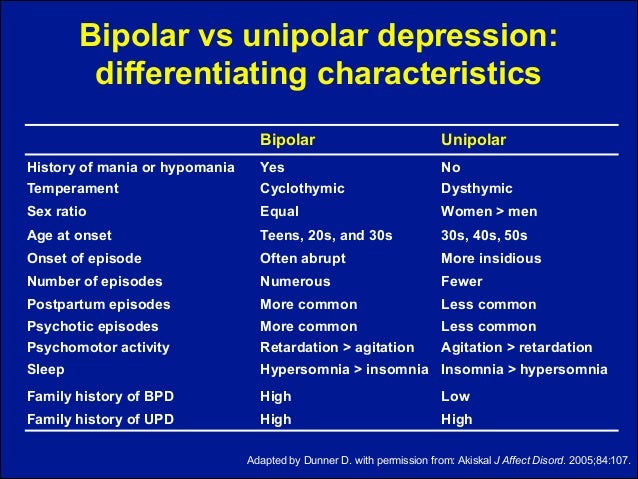

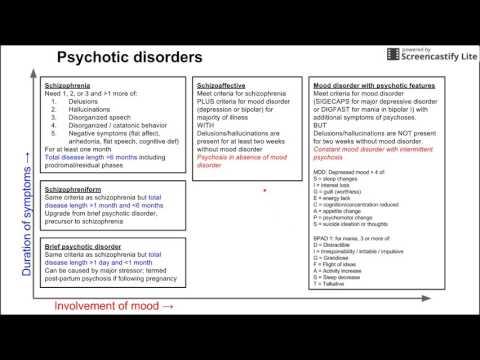

Bipolar disorder is easily confused with depression because it can include depressive episodes. The main difference between the two is that depression is unipolar, meaning that there is no “up” period, but bipolar disorder includes symptoms of mania.

To differentiate between the two disorders, it helps to understand the symptoms of each one.

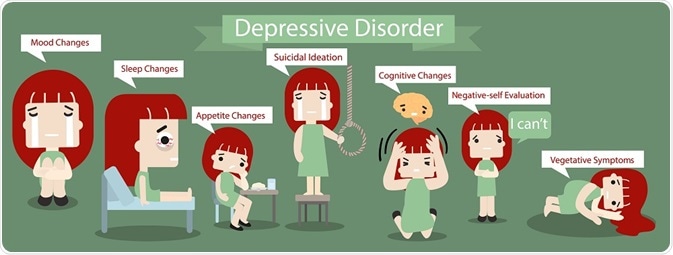

Symptoms of Depression

The essential feature of major depressive disorder is a period of two weeks or more during which there is either depressed mood most of the day nearly every day or loss of interest or pleasure in nearly all activities. Other potential symptoms include:

Significant weight loss when not dieting or weight gain and changes in appetite

Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day

Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day

Fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day

Feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt

Impaired ability to think or concentrate, and/or indecisiveness

Recurrent thoughts of death, recurrent suicidal ideation without a plan, or a suicide attempt or suicide plan

The symptoms of major depressive disorder cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other areas of functioning. To meet the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder, there should be no history of a manic episode or a hypomanic episode.

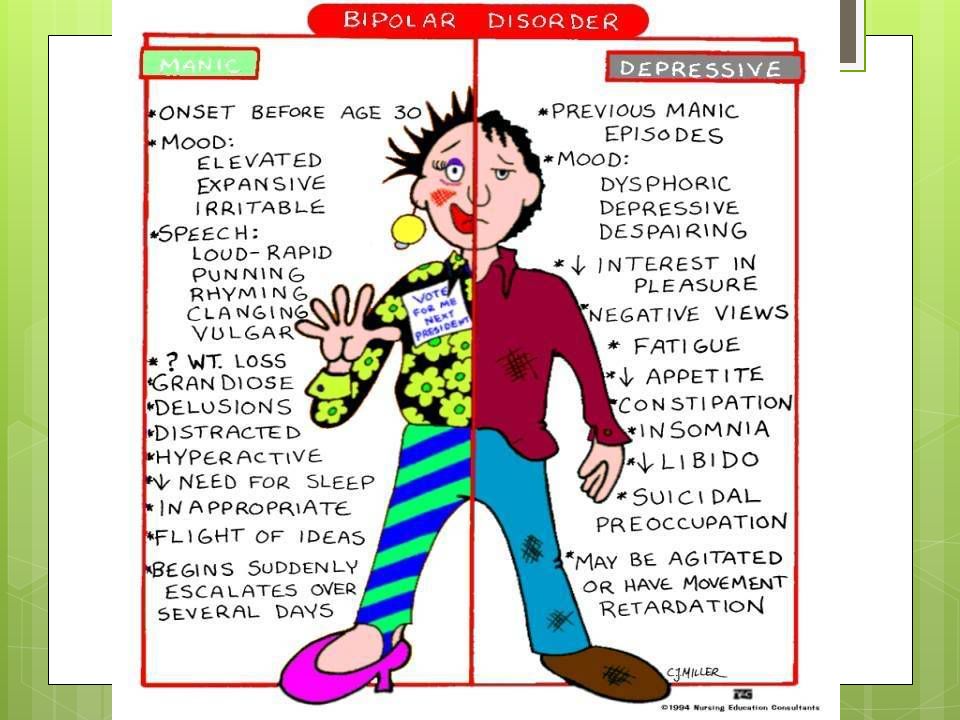

Symptoms of Bipolar Disorder

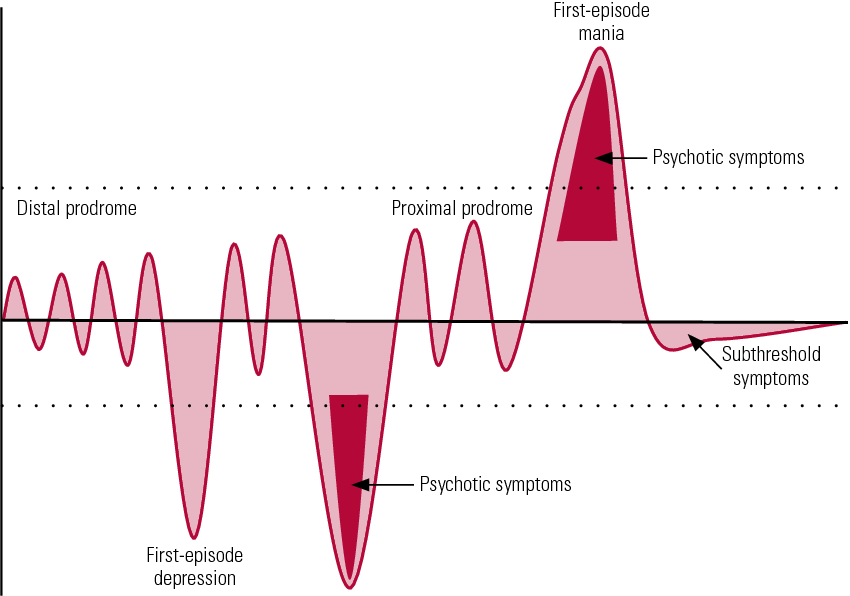

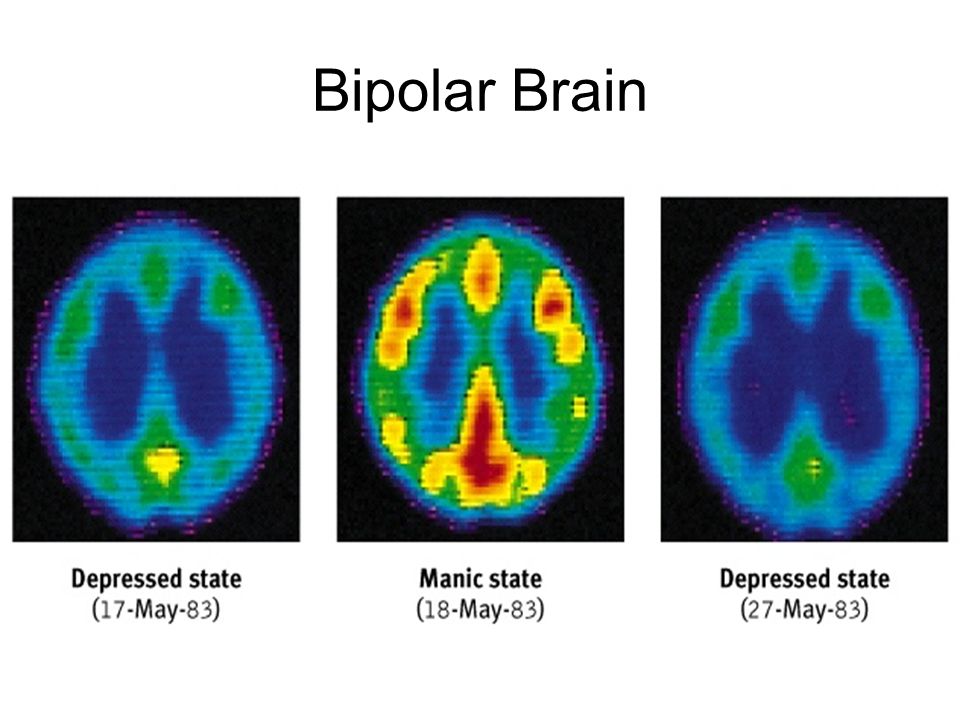

Although bipolar disorder can include the above depressive symptoms, it also includes symptoms of mania. Bipolar disorder is characterized by mood swings that fluctuate between depressive lows and manic highs.

A manic episode is described as a distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood and increased goal-directed activity or energy, lasting at least one week.

Symptoms of mania include:

Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity

Decreased need for sleep

More talkative than usual or pressured speech

Flight of ideas, racing thoughts

Distractibility

Increase in goal-directed activity

Excessive involvement in potentially reckless activities (usually involving drugs, money, or sex)

With bipolar disorder, the mood episode is severe enough to cause marked impairment in social or occupational functioning or to require hospitalization to avoid self-harm.

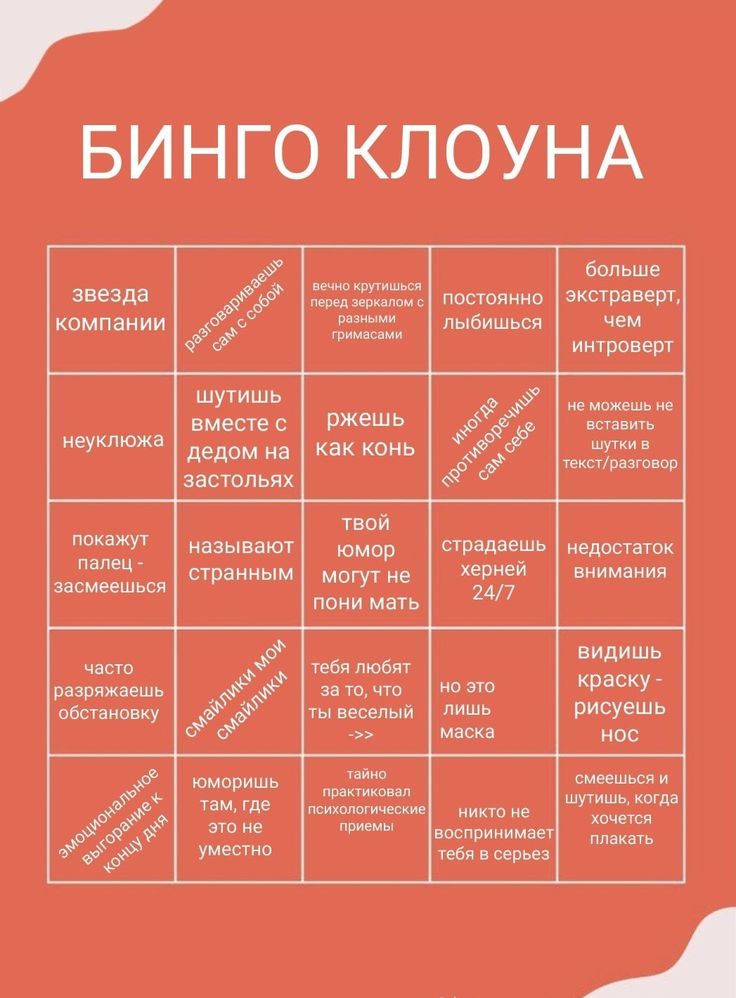

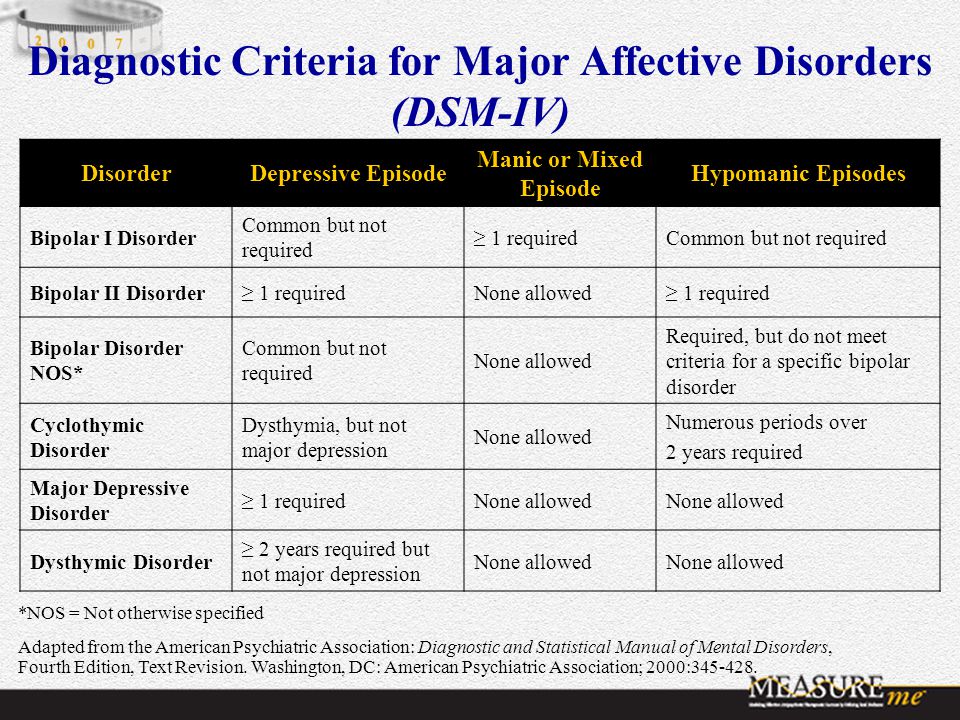

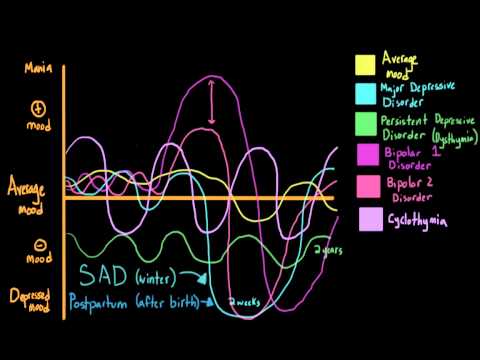

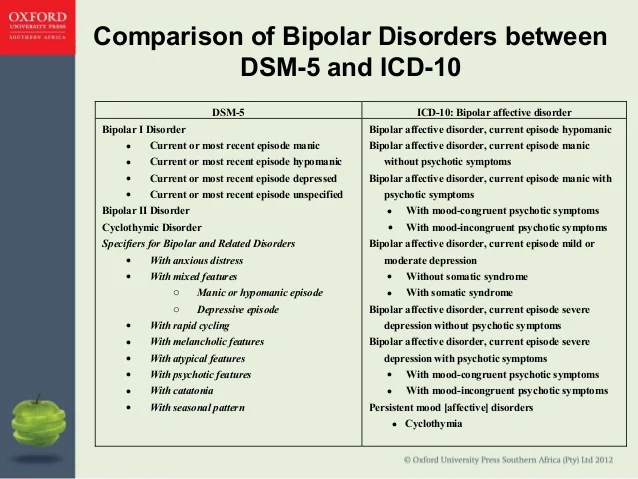

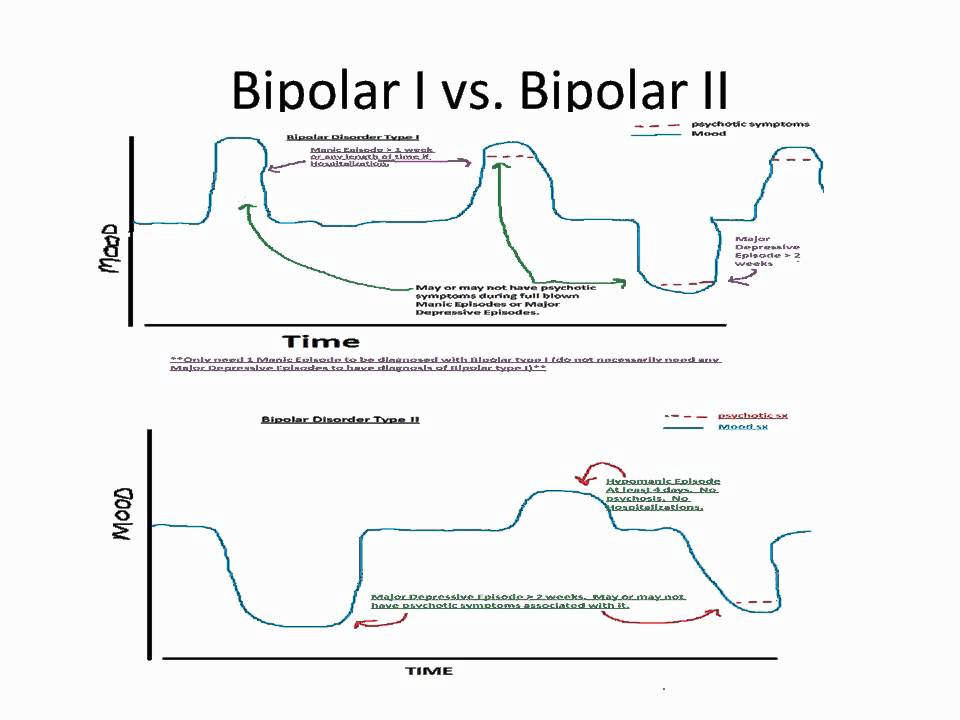

Types of Bipolar Disorder

There are two types of bipolar disorder and two closely related disorders. Understanding the different types of bipolar disorder can help distinguish between bipolar disorder and depression.

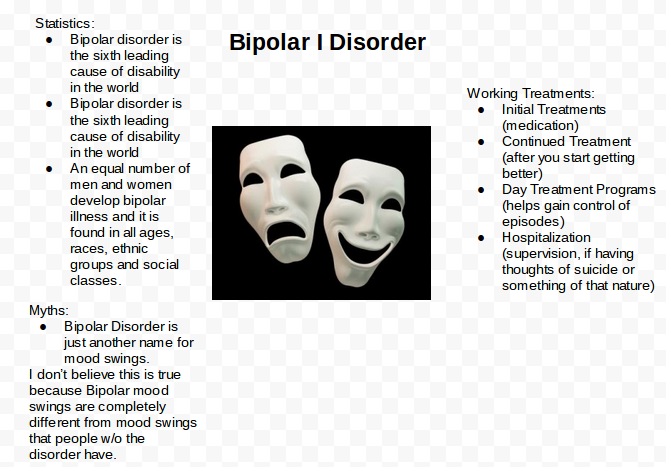

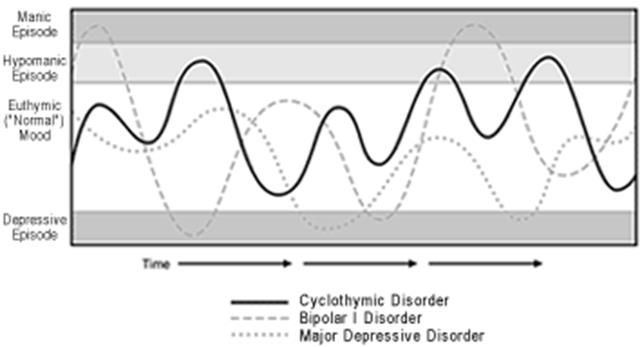

Bipolar I disorder

This is diagnosed when a patient has had at least one manic episode, regardless of whether or not there has been a depressive episode.

Bipolar II disorder

This diagnosis is given when a patient has had at least one depressive episode and a period of elevated mood referred to as hypomania. Bouts of hypomania are not as extreme as mania and are shorter lived. Patients with bipolar II tend to experience longer depressive episodes and shorter states of hypomania. Patients often seek treatment during the depressive episode, as the hypomanic symptoms might not impact functioning as much.

Cyclothymic disorder

The essential feature of cyclothymic disorder is a chronic, fluctuating mood disturbance involving numerous hypomanic symptoms and periods of depressive symptoms that are distinct from each other. The hypomanic symptoms do not meet the full criteria for a hypomanic episode and the depressive symptoms do not meet the full criteria for a depressive episode.

The hypomanic symptoms do not meet the full criteria for a hypomanic episode and the depressive symptoms do not meet the full criteria for a depressive episode.

Unspecified bipolar disorder

This diagnosis may be given when there is clinically significant abnormal mood elevation that doesn’t match the full criteria for the other three disorders. These disorders can be substance-induced or associated with other conditions.

Treatment for Bipolar and Depression

Left untreated, both bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder can have a major impact on social and occupational functioning. Both include the risk of suicide. The good news is that both conditions are treatable. Combination treatment often works best in both cases. Possible treatment modalities include:

Talk therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Family therapy (involvement of family members increases success)

Medication management (including antidepressants and/or mood stabilizers)

Accurate diagnosis is crucial if antidepressants or other depression medications are prescribed, because some can worsen bipolar disorder symptoms.

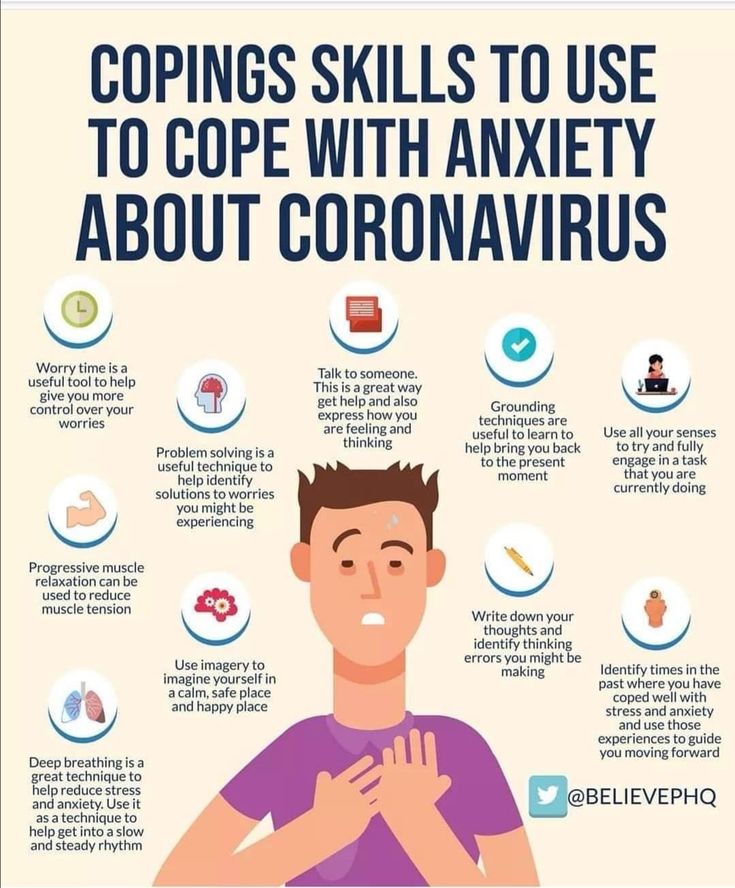

Patients with both depression and bipolar disorder respond well to highly structured routines. Creating a routine helps patients know what to expect and follow through with medication management independently.

What to Do When You Are Depressed

The first thing to realize is that you’re not alone. Depression is temporary; there is help, hope, and a way out. You can make lifestyle choices that will have a significant, positive impact on your depression.

If your depressive symptoms are severe or leading to suicidal thoughts or major functional impairment, seek professional help as soon as possible. Depression is a mental health condition that can be treated, and that you don't have to "power through."

For more mild depression symptoms or as part of a treatment plan, you may want to start with exercise, as research shows that exercise can lift mood, especially when used in conjunction with medication and talk therapy. Even light activities like a brisk walk can relieve depressive symptoms. Choosing a team sport may help reduce feelings of isolation.

Choosing a team sport may help reduce feelings of isolation.

Getting out in nature regularly may also relieve depression. This doesn’t mean you have to be in the deep wilderness. Simple, nature-based activities like gardening or a stroll in the park or around your neighborhood can help.

You might also try writing about your feelings. This can be done in the form of therapeutic writing with a trained therapist, creative writing, or writing song lyrics, with an emphasis on what you're feeling.

Music may also reduce depressive symptoms. The American Music Therapy Association is a good place to find out more information about formal music therapy and to locate a qualified music therapist.

Socializing is an important component of managing depression. Research consistently shows that people with strong social networks feel and function better than those with weak or limited connections. Of course, this may be easier said than done. Having depression can make it hard to connect with other people. Know that there is always someone available to help you take the first step. If you find it difficult to talk to family or friends, see the hotlines below.

Know that there is always someone available to help you take the first step. If you find it difficult to talk to family or friends, see the hotlines below.

Recognizing and Preventing Depression in Bipolar Disorder

In addition to the essential features of depression, you may be experiencing subtler symptoms. You may feel generally unmotivated to do activities you once found enjoyable. You might also have a sense of emptiness, feel cranky, or experience unexplained body aches or digestive issues, but not connect these feelings to depression.

If you suspect you might be depressed, take a moment to ask yourself the following questions:

Have I lost my enthusiasm for life in general or for things I once found enjoyable?

Do I feel agitated or cranky?

Do I feel I lack a purpose in life?

Do I get easily frustrated or overwhelmed?

Have family members or friends told you that you “don’t seem like yourself”?

If you feel like you are depressed, take action. Begin by talking to someone you trust, and contact your health care provider for guidance.

Begin by talking to someone you trust, and contact your health care provider for guidance.

The most important element in preventing depression is engaging in a regular structure of proactive, positive behaviors. Exercising regularly; eating regular, nutritious meals; socializing with people you care about; and participating in fun activities will help you manage your depression.

Moreover, if you have bipolar disorder and your medication is helping relieve depressive symptoms, you should continue to take it daily. If the medication isn’t helping, or if it has unpleasant side effects, communicate this with your health care providers. They can often adjust your dose or change your prescription to one that is more effective.

It may help to reframe your depression and your struggle with bipolar disorder as a journey to recovery, with you at the center. Recent research of people who have successfully managed bipolar disorder has identified the following themes:

Recognizing the problem

Obtaining support

Using medication

Participating in psychological therapy

Changing thought patterns

Suicide and Depression in Bipolar Disorder

Some people with bipolar depression feel so overwhelmed that they think suicide is the only option. It’s not. There are some practical measures you can take to prevent it, including:

It’s not. There are some practical measures you can take to prevent it, including:

Keeping a list of important contacts handy

Removing any means of suicide (guns, razors, medications you may overdose on)

Staying away from alcohol and recreational drug use

Avoiding websites that encourage negativity and suicide

Joining a support group

If your depression is so severe that you’re thinking about suicide or engaging in self-injury, call any of the following hotlines:

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (988)

Crisis Text Line: Text Hello to 741741 (for self injury)

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration National Helpline (1-800-662-HELP (4357))

If you are part of the LGBTQIA+ community, you may wish to contact the following organizations:

Remember that depression is a temporary state, and that being proactive in your recovery is the key to positive change.

Is bipolar linked to depression?

Bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder are both mood disorders. They are similar in that both include periods of feeling low mood or lack of in everyday activities. Bipolar disorder, formerly called "manic depression" has periods of mania; depression does not. They are both serious mental disorders— different criteria for diagnosis—and both have effective treatments.

Can bipolar turn into depression?

While one disorder cannot evolve into or become another, it’s possible that someone diagnosed with depression experiences the symptoms of bipolar disorder (ie. mania) later in life1, or that someone with bipolar is misdiagnosed initially with major depressive disorder, because of the similarity of the disorders’ symptoms.

Is bipolar more serious than depression?

Both are serious mental illnesses than can affect a person’s quality of life. And both can lead to serious consequences if left untreated, including suicide, self-harm, reckless behavior, and impairment at work, home, or school. Both bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder, however, can be treated to lessen the risk of these dangerous symptoms.

Both bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder, however, can be treated to lessen the risk of these dangerous symptoms.

Is bipolar depression worse than unipolar depression?

Some research has found that people with bipolar disorder, when not in a depressed phase, are worse at regulating happy and sad emotions than are those with depression.2 Also, bipolar disorder features more phases than does major depressive disorder, including mania, hypomania and depression.

But in terms of severity, neither disorder is worse, or better, than the other.

American Psychological Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, American Psychiatric Publishing, Washington, D.C., 2013.

Kvam S, Kleppe CL, Nordhus IH, Hovland A. Exercise as a treatment for depression: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. Published online 2016 Sep 15.doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.063.

Arroll B, Moir F, Kendrick T. Effective management of depression in primary care: a review of the literature. BJGP Open. 2017 Jun 28. doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen17X101025.

Effective management of depression in primary care: a review of the literature. BJGP Open. 2017 Jun 28. doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen17X101025.

Chaudhury P, Banerjee D. Recovering With Nature: A Review of Ecotherapy and Implications for the COVID-19 Pandemic.* Front Public Health.* 2020 Dec 10. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.604440.

Cooper P. Writing for Depression in Health Care. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2013. doi:10.4276/030802213X13651610908452.

Gee KA, Hawes V, Cox NA. Blue Notes: Using Songwriting to Improve Student Mental Health and Wellbeing. A Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial. Front Psychol. 2019 Mar doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00423. PMID: 30890979; PMCID: PMC6411695.

Roddis JK, Tanner M. Music therapy for depression. Res Nurs Health. 2020 Jan doi: 10.1002/nur.22006.

Sarris J, O'Neil A, Coulson CE, Schweitzer I, et al. Lifestyle medicine for depression. *BMC Psychiatry. *Apr 10, 2014 doi:1186/1471-244X-14-107.

MedlinePlus, National Library of Medicine. Depression. Available at https://medlineplus.gov/depression.html Nov 4, 2016. Accessed October 6, 2022.

Depression. Available at https://medlineplus.gov/depression.html Nov 4, 2016. Accessed October 6, 2022.

Warwick H, Tai S, Mansell W. Living the life you want following a diagnosis of bipolar disorder: A grounded theory approach. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, May 26, 2019. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2358.

FAQ Sources:

- O'Donovan C and Alda M. Depression Preceding Diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder. Front Psychiatry. Published online 2020 Jun 11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00500. Accessed March 8, 2022

- Rive M et al. State-Dependent Differences in Emotion Regulation Between Unmedicated Bipolar Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 Jul;72(7):687-96. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0161. Accessed March 8, 2022

Notes: This article was originally published March 8, 2022 and most recently updated November 7, 2022.

Bipolar vs. Major Depression: How Do They Differ?

- Depression

- Emotional Health

Women. Wisdom. Wellness.

Jan 30, 2018

Wisdom. Wellness.

Jan 30, 2018

It's easy to get the care you need.

See a Premier Physician Network provider near you.

Schedule Now

When you face the low feelings of depression, hope can seem distant. But the good news, says Beth Esposito, MS, LPCC-S, LSW, of Samaritan Behavioral Health: Depression is a treatable illness.

Depression treatment that works for one person, however, may not work for another. That’s because depression varies from one person to the next – in severity and type. Finding the right treatment for you may take time and fine-tuning, Esposito says.

She offers the following comparisons of two common types of depression and their symptoms, diagnosis and treatment:

- Bipolar depression, which is characterized by alternating (sometimes simultaneous) periods of depression and mania

- Unipolar depression, more commonly known as major depression, which has no manic periods

If you experience one episode of depression, you are at risk of recurring bouts.

Bipolar Depression

Sometimes referred to as manic depression, bipolar depression ranges from “depression so low you can’t get out of bed” to manic highs of euphoria and “talking so fast and furiously, you can’t follow the train of thought,” Esposito says.

“Think of the best day you’ve ever had, multiply that by one hundred, and that’s the mania of bipolar depression.”

However, the manic phase varies in intensity in two types of bipolar disorder, classified as bipolar I and bipolar II, Esposito adds.

In bipolar I, manic episodes are more intense. The resulting mood swings – from the lows of depression to the highs of mania – make maintaining a job and taking care of life’s issues difficult.

With bipolar II, the manic phase – called hypomania – is mild in comparison. With hypomania, you feel and function well in many situations, including at work.

During manic phases, people with bipolar disorder typically “feel good and can get all sorts of things done,” Esposito said. Because they feel good, they sometimes stop taking their medication. And without treatment, the mania – and depression – can intensify over time.

Because they feel good, they sometimes stop taking their medication. And without treatment, the mania – and depression – can intensify over time.

In the more intense manic swings of bipolar I disorder, an individual may lose judgment and act irrationally. “They can spend money they don’t have, have overdrawn bank accounts, get in trouble with the law,” Esposito explains. “They may have multiple partners, they’re oversexualized, they make poor decisions and won’t listen to loved ones.”

And a person in the manic state may be unaware of the consequences of impulsive behavior caused by the condition.

Other manic symptoms include:

- Excessively high, euphoric mood

- Increased energy, activity and restlessness

- Agitation and extreme irritability

- Decreased need for sleep without feeling tired

- Fast speech and racing thoughts

- Difficulty focusing

- Abuse of drugs

A diagnosis of bipolar depression requires at least one manic episode. A bipolar I diagnosis requires a manic episode that lasts at least seven days or manic symptoms so severe that hospital care is needed – and depression episodes that last at least two weeks.

A bipolar I diagnosis requires a manic episode that lasts at least seven days or manic symptoms so severe that hospital care is needed – and depression episodes that last at least two weeks.

A bipolar II diagnosis requires a pattern of depressive and hypomanic episodes.

Major Depression

Major, or unipolar depression, is characterized by persistent periods of sadness, without the high, manic phases of bipolar depression. While depression can be triggered by life events, major depression stretches beyond normal periods of sadness experienced after disappointing or traumatic life events.

Symptoms such as the following may signal that ordinary sadness has turned to major depression – particularly if five or more of the following symptoms persist for at least two weeks, Esposito says:

- Sad, anxious mood or feeling of emptiness

- Loss of interest in activities that you once enjoyed

- Difficulty concentrating, remembering or making decisions

- Decreased energy and increased tiredness

- Feelings of guilt, hopelessness, worthlessness and helplessness

- Irritability

- Over sleeping or difficulty sleeping

- Changes in appetite, weight loss or gain unrelated to dieting

- Hand-wringing, pacing or other purposeless physical activity

- Slowed speech or movements

- Headaches, digestive problems, cramps, or aches or pains that do not ease with treatment and have no clear physical cause

- Repeating thoughts of death or suicide (which calls for emergency care)

A mental health professional may diagnose depression through a psychiatric exam and a review of your medical history.

If you experience one episode of depression, you are at risk of recurring bouts. And if you don’t get treatment, depression can become more frequent and serious.

Depression Treatment

Depression affects everyone differently, so effective treatment can differ from one person to the next. Your health care provider may need to try various treatments, including medications, to discover what works best for you.

Medications, psychotherapy, or a combination are commonly used to treat major depression. Some with depression can be treated with psychotherapy, or talk therapy, alone – without medication.

However, Esposito says, “with bipolar, medication is necessary to even out the mood changes.” An effective treatment plan usually includes a combination of medication and talk therapy.

Different types of medications are available to control bipolar symptoms. And more than one type may need to be tried – with the understanding that noticeable results may take time, often two to four weeks.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and other brain stimulation therapies may be considered for those who do not respond to medication and talk therapy, and whose depression symptoms persist.

Esposito adds that a support group of friends or family can play a key role in helping you during therapy.

She adds, if you encounter someone who may exhibit signs of depression, don’t be afraid to approach the person. She explains it’s common for people to say, “‘I didn’t ask the person because I thought I would make it worse.’ It’s not going to make it worse by asking, so always ask (if they need help).

“When someone’s depressed, it gets to the point they have no energy, they don’t care. They need someone to ask them and get them the help that they need.”

It's easy to get the care you need.

See a Premier Physician Network provider near you.

Schedule Now

Source: Beth Esposito, MS, LPCC-S, LSW, Samaritan Behavioral Health; National Alliance on Mental Illness; National Institute of Mental Health; ULifeline

Beth Esposito, MS, LPCC-S, LSW

President, Samaritan Behavioral Health

Small Steps: Practice Yoga to Fight Anxiety

Take a class in your community or find one online to help calm yourself both physically and mentally.

Observations on 2.7 million people point to a complex relationship between depression and bipolar disorder - PCR News

Prepared by

Alina Suleymanova

American and Swedish researchers assessed the risks of developing nine mental illnesses in groups of patients with different predispositions to depression and bipolar disorder. It turned out that both depression and bipolar disorder are associated with an increased risk of affective disorders, but differ in terms of the risks of developing anxiety disorders and psychosis. nine0005

Prepared by

Alina Suleymanova

There is still an open question about the genetic relationship between depression (major depressive disorder, MDD) and bipolar disorder (BD). Initially, they were grouped into a disease known as manic-depressive psychosis, but they were later separated. Studies of the occurrence of MDD and BD in families did not give an unambiguous answer about the unity or difference in the genetic causes of these conditions. In a new study, scientists from Virginia Commonwealth University and Lund University tried to figure out how a genetic predisposition to depression is associated with a predisposition to bipolar disorder. nine0005

Studies of the occurrence of MDD and BD in families did not give an unambiguous answer about the unity or difference in the genetic causes of these conditions. In a new study, scientists from Virginia Commonwealth University and Lund University tried to figure out how a genetic predisposition to depression is associated with a predisposition to bipolar disorder. nine0005

The researchers analyzed data from more than 2.7 million people (mean age 43.9 years) who were born in Sweden between 1960 and 1990 and were seen by a doctor until the end of 2018. Data included an assessment of familial genetic risk for MDD and BD. The scientists divided patients into five groups depending on their genetic predisposition to MDD and BD: people with a high genetic predisposition to MDD, to BD, to both MDD and BD, with a high genetic predisposition to MDD and low to BD, and vice versa. In each of the groups, the authors assessed the risks of developing nine mental disorders, including psychotic and non-psychotic subtypes of MDD and BD, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and other types of psychoses. nine0005

nine0005

The scientists tested three hypotheses about the relationship between genetic risk factors for MDD and BD: the factors may be the same, unrelated, or contribute in the same way to certain aspects of the pathology, but differ in others.

Common in the case of depression and bipolar disorder was a high risk of developing a non-psychotic subtype of BD. However, the relationship with other psychiatric disorders differed for MDD and BD. Thus, the risk of schizophrenia and psychosis was significantly higher in the group with a predisposition to BD, while the risk of anxiety disorders and OCD was significantly higher in the group with a predisposition to MDD. nine0005

A genetic predisposition to both conditions increased the risk of developing two subtypes of depression, non-psychotic BD, anxiety disorders, and obsessive-compulsive disorders, but was not associated with psychotic BD, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder.

In the high-risk BD and low-risk MDD group, researchers found significant reductions in the risks of four disorders—the nonpsychotic subtypes of MDD and BD, anxiety disorders, and OCD—compared to the high-risk BD-only group. At the same time, a high risk of developing MDD and a low risk of BD were associated with a reduction in the risk of only two diseases - the non-psychotic subtype of MDD and anxiety disorders - compared with a group with a high predisposition to only MDD. nine0005

At the same time, a high risk of developing MDD and a low risk of BD were associated with a reduction in the risk of only two diseases - the non-psychotic subtype of MDD and anxiety disorders - compared with a group with a high predisposition to only MDD. nine0005

Separately, scientists assessed the relationship of genetic predisposition to MDD or BD with the risk of developing their psychotic forms. Interestingly, the researchers were able to find such a link for bipolar disorder, but not for depression.

Thus, two opposite hypotheses about a close or weak relationship between the genetic causes of MDD and BD were not confirmed in the work performed. On the contrary, the results obtained indicate a more complex association of the two states. To learn more about it, the authors say, we need to move on to examining the risks for a wide range of mental health conditions, not just these two disorders in isolation. nine0005

Source:

Kendler K. S., et al. Risk for Mood, Anxiety, and Psychotic Disorders in Individuals at High and Low Genetic Liability for Bipolar Disorder and Major Depression. // JAMA Psychiatry, 2022, published online 21 September 2022. DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.2873

S., et al. Risk for Mood, Anxiety, and Psychotic Disorders in Individuals at High and Low Genetic Liability for Bipolar Disorder and Major Depression. // JAMA Psychiatry, 2022, published online 21 September 2022. DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.2873

Genetics

✚ Treatment of persistent depression. Neuropsychiatric clinic of Professor Minutko. Article No. 5511

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in the US describes an episode of major depressive disorder (MDD) in a constellation of several symptoms that persist most of the day almost every day for at least 2 weeks? Although bereaved patients may experience a major depressive episode, it is important to distinguish between the manifestations of grief and MDD.

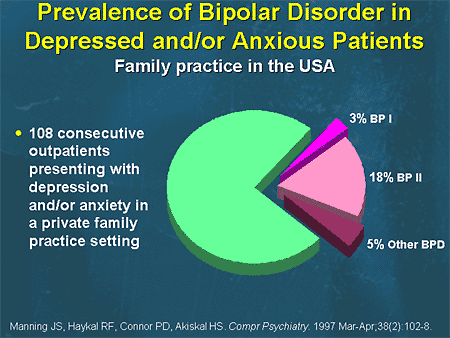

Clinicians should also consider when making a diagnosis that the patient's symptoms should not be explained by medical conditions such as hypothyroidism, drug side effects, chronic alcohol or substance use, or other psychiatric disorder. For example, patients with schizophrenia or post-traumatic stress disorder or who are in the early stages of dementia also report their symptoms of depression. Some patients suffering from clear depressive episodes also experience episodes of mania or hypomania. Somewhere between 20% and 50% of depressions are thought to fall on a bipolar spectrum that ranges from bipolar I disorder to an MDD patient experiencing a bizarre and sometimes subtle admixture of hypomanic symptoms during depressive episodes. nine0005

For example, patients with schizophrenia or post-traumatic stress disorder or who are in the early stages of dementia also report their symptoms of depression. Some patients suffering from clear depressive episodes also experience episodes of mania or hypomania. Somewhere between 20% and 50% of depressions are thought to fall on a bipolar spectrum that ranges from bipolar I disorder to an MDD patient experiencing a bizarre and sometimes subtle admixture of hypomanic symptoms during depressive episodes. nine0005

Classifiers recognize several modifiers or sub-categories of MDD, such as depressive episode with anxiety symptoms, which researchers believe suggest a poorer prognosis and poorer response to conventional therapy.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a complex, often relapsing or chronic condition that includes emotional, psychological, behavioral and somatic (physical) symptoms. Also known as "unipolar depression", MDD is one of the most common causes of disability worldwide. In the US, approximately 17% of people experience at least one episode of unipolar depression during their lifetime. Approximately 16 million adults (6.7%) and 3.1 million teens (12.8%) experienced a major depressive episode in 2016. Approximately two-thirds of people who have a depressive episode report a significant deterioration in professional, family functioning. In addition, MDD worsens most chronic diseases and is associated with a 60-80% increase in mortality. nine0005

In the US, approximately 17% of people experience at least one episode of unipolar depression during their lifetime. Approximately 16 million adults (6.7%) and 3.1 million teens (12.8%) experienced a major depressive episode in 2016. Approximately two-thirds of people who have a depressive episode report a significant deterioration in professional, family functioning. In addition, MDD worsens most chronic diseases and is associated with a 60-80% increase in mortality. nine0005

Depressive disorders often go untreated. A World Health Organization survey found that even in wealthy countries like the US, only about a quarter of people with unipolar depression receive minimally adequate treatment. However, primary care physicians could shorten the gap between depression onset and treatment (currently estimated at ~4 years) and detect depression early if physicians pay attention to their patients' moods. nine0005

The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) and the Montgomery-Osberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) are frequently used in research, but their complexity and time-consuming nature make them unsuitable for use in routine clinical practice. An abbreviated version of the patient questionnaire (PHQ-9) is useful for primary health care as an initial screening tool for clinically significant depression. In addition to the PHQ-9, the Rapid Inventory of Depressive Symptom-Self-Report (QIDS-SR) version and the Clinically Useful Depression Outcome Scale (CUDOS) are self-report scales that are easy to use. At the same time, CUDOS and HDRS make it possible to classify patients with residual symptoms. nine0005

An abbreviated version of the patient questionnaire (PHQ-9) is useful for primary health care as an initial screening tool for clinically significant depression. In addition to the PHQ-9, the Rapid Inventory of Depressive Symptom-Self-Report (QIDS-SR) version and the Clinically Useful Depression Outcome Scale (CUDOS) are self-report scales that are easy to use. At the same time, CUDOS and HDRS make it possible to classify patients with residual symptoms. nine0005

Suicidal thoughts or suicide attempts are not uncommon in patients with unipolar depression.

The treatment phases for major depressive disorder (MDD) include acute, prolonged, and maintenance periods. The goals of the acute (rescue) phase of therapy are to find a well-tolerated and effective treatment that will lead, first, to a significant reduction in the symptoms of depression (called response) and, therefore, a complete remission of depressive symptoms. nine0005

In clinical trials, response is usually defined as at least a 50% improvement in symptom relief score, which is typically achieved in 4-8 weeks. This definition of "response" to antidepressants, however, allows for significant residual symptoms of depression. A "response" to antidepressant therapy usually develops within 1-2 months, however, the complete lack of improvement in patients' condition after 2 weeks of treatment predicts a subsequent weak "response" to antidepressant treatment. If too many persistent symptoms of depression remain to achieve remission after 6-8 weeks of therapy, it is unclear whether the best course of action is to switch therapy to other antidepressants or use an additional strategy that may improve the "response" to treatment. nine0005

This definition of "response" to antidepressants, however, allows for significant residual symptoms of depression. A "response" to antidepressant therapy usually develops within 1-2 months, however, the complete lack of improvement in patients' condition after 2 weeks of treatment predicts a subsequent weak "response" to antidepressant treatment. If too many persistent symptoms of depression remain to achieve remission after 6-8 weeks of therapy, it is unclear whether the best course of action is to switch therapy to other antidepressants or use an additional strategy that may improve the "response" to treatment. nine0005

The continuation phase includes 4 to 9 months of therapy after achieving remission, during which the patient takes the same drug at the same dose to prevent relapse of depression. The goal of therapy is recovery - almost complete relief from depressive symptoms that have been absent for several months. For patients who are known to be at high risk of depressive relapse, an indeterminate course of maintenance phase pharmacotherapy is recommended to prevent recurrence of depression. If prophylactic therapy continues for months or years, the antidepressant dose will usually need to be reduced over several weeks to avoid antidepressant withdrawal symptoms. nine0005

If prophylactic therapy continues for months or years, the antidepressant dose will usually need to be reduced over several weeks to avoid antidepressant withdrawal symptoms. nine0005

Although more than 20 antidepressant drugs (ADMs) are currently in high demand for the treatment of MDD, many patients do not respond to adequate and consistent courses of antidepressant medication. The term treatment-resistant depression (TRD) has been used for decades to describe an illness that does not respond to treatment with two or more prescribed antidepressants. Thus, TRD is a description of a specific pattern of long-term (longitudinal) treatment of patients, and not a diagnosis per se. However, the road to resistance begins with the patient not responding to the first prescription of an antidepressant, which occurs in about 40% - 50% of cases. The likelihood of a "response" decreases with each subsequent prescription of a new antidepressant, which may be due to the fact that the most commonly used antidepressants (ADMs) have similar mechanisms of action. In the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives for Depression Relief (STAR*D) study, the estimated remission rate after 4 courses of antidepressant therapy during the initial treatment period was 13%. At follow-up, half of the patients who achieved remission after the fourth appointment of a new antidepressant relapsed into depression. nine0005

In the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives for Depression Relief (STAR*D) study, the estimated remission rate after 4 courses of antidepressant therapy during the initial treatment period was 13%. At follow-up, half of the patients who achieved remission after the fourth appointment of a new antidepressant relapsed into depression. nine0005

Treatment-resistant depression (TRD) accounts for a significant portion of the $201 billion annual burden on the US economy. A survey of private insurance claims for nearly 200,000 US found that the combination of direct and indirect costs of treating treatment-resistant depression (TRD) was twice as high than the cost of more treatment-responsive episodes of unipolar depression.

The introduction of effective new antidepressants for the treatment of unipolar depression depends on a better understanding of the neurobiological mechanisms of depression. The most commonly used antidepressants were discovered when research was mainly focused on the monoamine theory of depression and therefore their mechanisms of action targeted the monoaminergic system. The original hypotheses of the monoamine theory of depression suggest that depressive symptoms result from a functional deficiency in monoamine neurotransmission in central nervous system tracts required for mood regulation, stress-reward response, cognition, motivation, and sleep. Neurotransmitters in this group include serotonin (5-HT), norepinephrine (NE) and, to a lesser extent, dopamine (DA). For example, one of the first hypotheses suggested that the presynaptic enzymatic degradation of monoamine oxidase and catechol-O-methyltransferase causes a deficiency in neurotransmitter activity. Some evidence suggests that depressed patients have higher levels of monoamine oxidase activity. Other studies show that some depressed patients have low levels of the metabolite 5-HT-5-HIAA (5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid) in the cerebrospinal fluid and low levels of the metabolite MHPG (3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol) in the urine. nine0005

The original hypotheses of the monoamine theory of depression suggest that depressive symptoms result from a functional deficiency in monoamine neurotransmission in central nervous system tracts required for mood regulation, stress-reward response, cognition, motivation, and sleep. Neurotransmitters in this group include serotonin (5-HT), norepinephrine (NE) and, to a lesser extent, dopamine (DA). For example, one of the first hypotheses suggested that the presynaptic enzymatic degradation of monoamine oxidase and catechol-O-methyltransferase causes a deficiency in neurotransmitter activity. Some evidence suggests that depressed patients have higher levels of monoamine oxidase activity. Other studies show that some depressed patients have low levels of the metabolite 5-HT-5-HIAA (5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid) in the cerebrospinal fluid and low levels of the metabolite MHPG (3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol) in the urine. nine0005

The monoamine hypotheses of depression arose in part from observations that tricyclic antidepressants blocked the reuptake, primarily of NE, but also of 5-HT, from the synaptic cleft, thereby increasing extracellular levels of these neurotransmitters. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) have also been shown to increase the synaptic availability of monoamine neurotransmitters by blocking the enzymatic degradation of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) have also been shown to increase the synaptic availability of monoamine neurotransmitters by blocking the enzymatic degradation of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine.

The first tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors were discovered through incidental observations (for example, imipramine and iproniazid were originally developed for the treatment of schizophrenia and tuberculosis, respectively). Thus, TCAs and MAOIs have major effects on neurotransmitter systems in addition to inhibiting monoamine uptake, and these effects help explain why these drugs cause such a range of adverse side effects. nine0005

As the use of antidepressants became common by the late 1960s and early 1970s, there has been increasing interest in the development of antidepressants that more selectively target monoaminergic neurotransmission. Newer antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs, SSRIs), serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs), have entered the pharmaceutical market and are safer and easier to use. Recent antidepressants have rapidly replaced TCAs and MAOIs as the standard first-line treatment for depression. nine0005

Recent antidepressants have rapidly replaced TCAs and MAOIs as the standard first-line treatment for depression. nine0005

Likely new antidepressants (antidepressants of the future) will target: the opioid system, neurokinin 1 receptors, nicotinic cholinergic receptors and tumor necrosis factor. New hypotheses of depression point to its pathogenetic mechanisms that go beyond monoaminergic neurotransmission.

Research into the treatment of depression is currently being conducted in the areas of glutamate neurotransmission and neuronal plasticity, cholinergic transmission, the opioid system, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation, neuroinflammation, and γ-aminobutyric acid neurotransmission. While clinical trials of new antidepressants targeting the opioid system have shown promising results, clinical trials of new drugs targeting receptors found on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the cholinergic system, or drugs that target tumor necrosis factor ( marker of neuroinflammation) have produced mixed and conflicting results.