Mania psychological disorder

What Is It, Causes, Triggers, Symptoms & Treatment

Overview

What is mania?

Mania is a condition in which you have a period of abnormally elevated, extreme changes in your mood or emotions, energy level or activity level. This highly energized level of physical and mental activity and behavior must be a change from your usual self and be noticeable by others.

What's considered an “abnormal,” extreme change in behavior and what does it look like?

Abnormal manic behavior is behavior that stands out. It’s over-the-top behavior that other people can notice. The behavior could reflect an extreme level of happiness or irritation. For example, you could be extremely excited about an idea for a new healthy snack bar. You believe the snack could make you an instant millionaire, but you’ve never cooked a single meal in your life, don’t know a thing about developing a business plan and have no money to start a business. Another example might be that you strongly disagree with a website “influencer” and not only write a 2,000-word post but do an exhaustive search to find all the websites connected to the influencer so you can post your letter there too.

Although these examples may sound like they could be normal behavior, a person with mania will expend a great deal of time and energy including many sleepless nights working on projects such as these.

What is a manic episode?

A manic episode is a period of time in which you experience one or more symptoms of mania and meet the criteria for a manic episode. In some cases, you may need to be hospitalized.

Can I have a manic episode as its own condition or is it always part of another mental health condition?

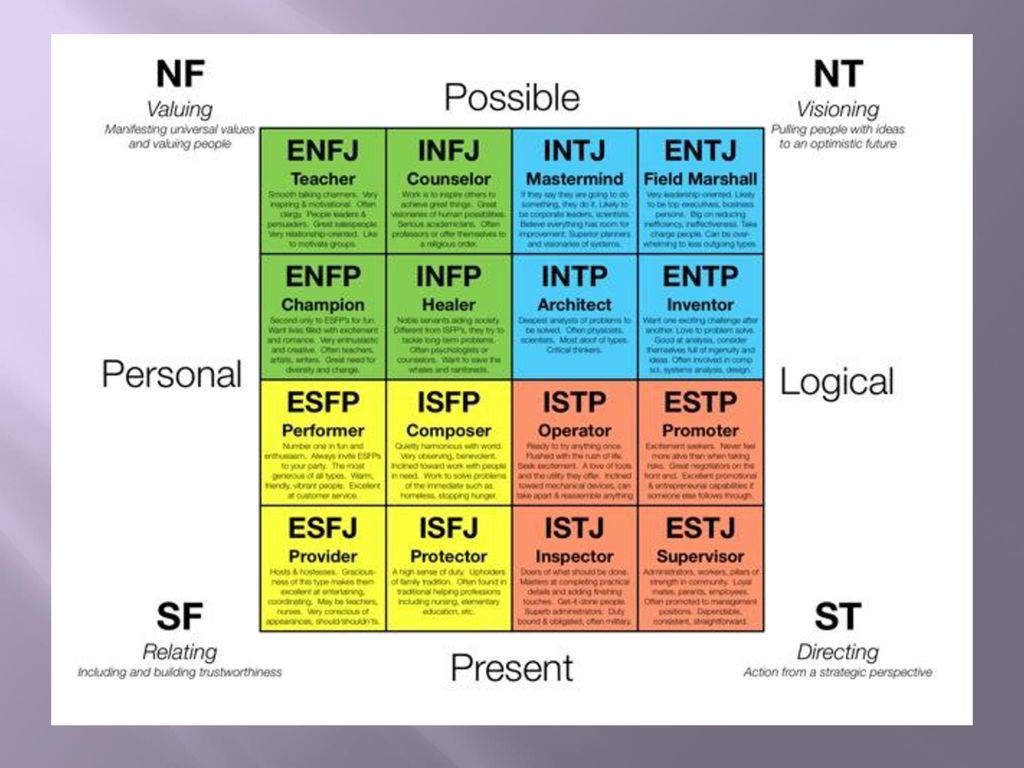

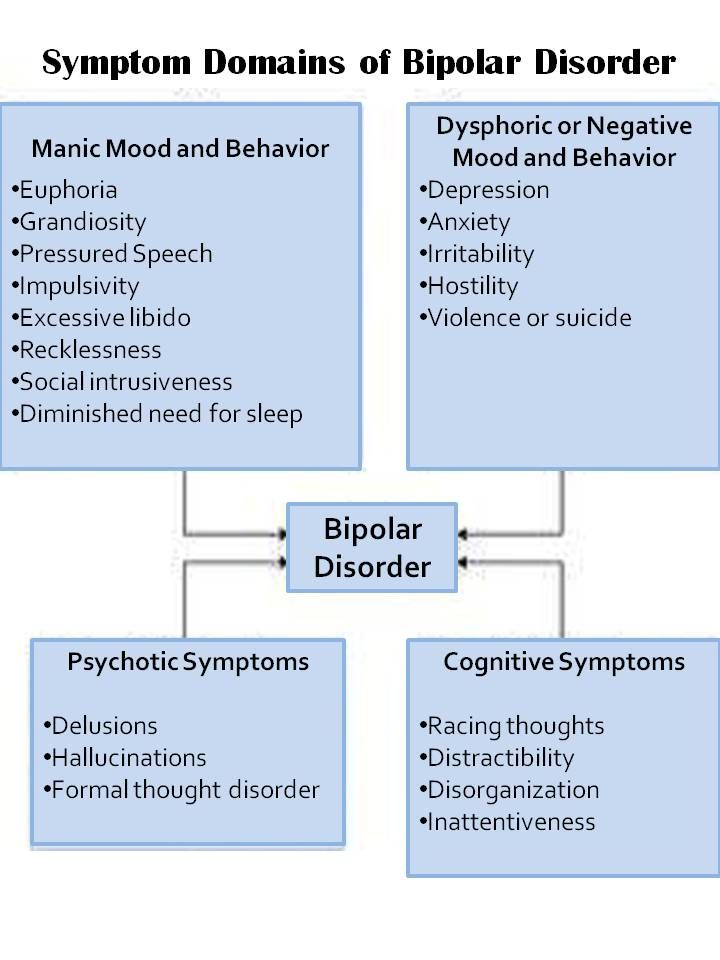

Technically if you have a manic episode, you have a mental health condition. Mania can be a part of several mental health conditions including:

- Bipolar I disorder (the most common condition for mania to occur).

- Seasonal affective disorder.

- Postpartum psychosis.

- Schizoaffective disorder.

- Cyclothymia.

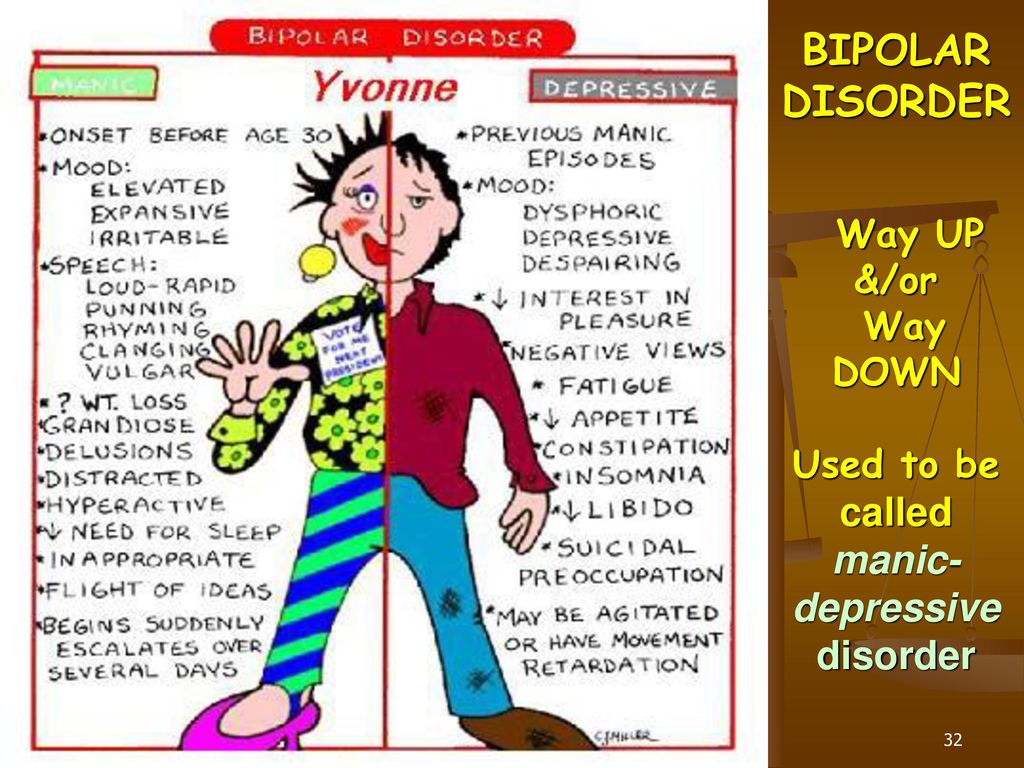

What is bipolar I disorder?

Bipolar I disorder is a mental health illness in which a person has major high and low swings in mood, activity, energy and ability to think clearly. To be diagnosed with bipolar I disorder, you have to have at least one episode of mania that lasts for at least seven days or have an episode that is so severe that it requires hospitalization.

To be diagnosed with bipolar I disorder, you have to have at least one episode of mania that lasts for at least seven days or have an episode that is so severe that it requires hospitalization.

Most people have both episodes of both mania and depression, but you don’t have to have depression to be diagnosed with mania. Many people with a bipolar I disorder diagnosis have recurring, back-to-back manic episodes with very few episodes of depression.

What are the triggers of manic episodes?

Manic episode triggers are unique to each person. You’ll have to become a bit of a detective and monitor your mood (even keeping a “mood diary”) and start to track how you feel before an episode and when it occurs. Ask family and close friends who you trust and have close contact with to help identify your triggers. As outside observers, they may notice changes from your usual behavior more easily than you do.

Knowing your triggers can help you prepare for an episode, lessen the effect of an episode or prevent it from happening at all.

Common triggers to be aware of include:

- A highly stimulating situation or environment (for example, lots of noise, bright lights or large crowds).

- A major life change (such as divorce, marriage or job loss).

- Lack of sleep.

- Substance use, such as recreational drugs or alcohol.

What happens after a manic episode?

After a manic episode, you may:

- Feel happy or embarrassed about your behavior.

- Feel overwhelmed by all the activities you’ve agreed to take on.

- Have only a few or unclear memories of what happened during your manic episode.

- Feel very tired and need sleep.

- Feel depressed (if your mania is part of bipolar disorder).

Symptoms and Causes

What are the symptoms of mania?

Symptoms of a manic episode

- Having an abnormally high level of activity or energy.

- Feeling extremely happy or excited — even euphoric.

- Not sleeping or only getting a few hours of sleep but still feeling rested.

- Having inflated self-esteem, thinking you’re invincible.

- Being more talkative than usual. Talking so much and so fast that others can’t interrupt.

- Having racing thoughts — having lots of thoughts on lots of topics at the same time (called a “flight of ideas”).

- Being easily distracted by unimportant or unrelated things.

- Being obsessed with and completely absorbed in an activity.

- Displaying purposeless movements, such as pacing around your home or office or fidgeting when you’re sitting.

- Showing impulsive behavior that can lead to poor choices, such as buying sprees, reckless sex or foolish business investments.

Psychotic symptoms of a manic episode

- Delusions. Delusions are false beliefs or ideas that are incorrect interpretations of information. An example is a person thinking that everyone they see is following them.

- Hallucinations. Having a hallucination means you see, hear, taste, smell or feel things that aren’t really there.

An example is a person hearing the voice of someone and talking to them when they’re not really there.

An example is a person hearing the voice of someone and talking to them when they’re not really there.

How long does a manic episode last?

Early signs (called “prodromal symptoms”) that you’re getting ready to have a manic episode can last weeks to months. If you’re not already receiving treatment, episodes of bipolar-related mania can last between three and six months. With effective treatment, a manic episode usually improves within about three months.

What causes mania?

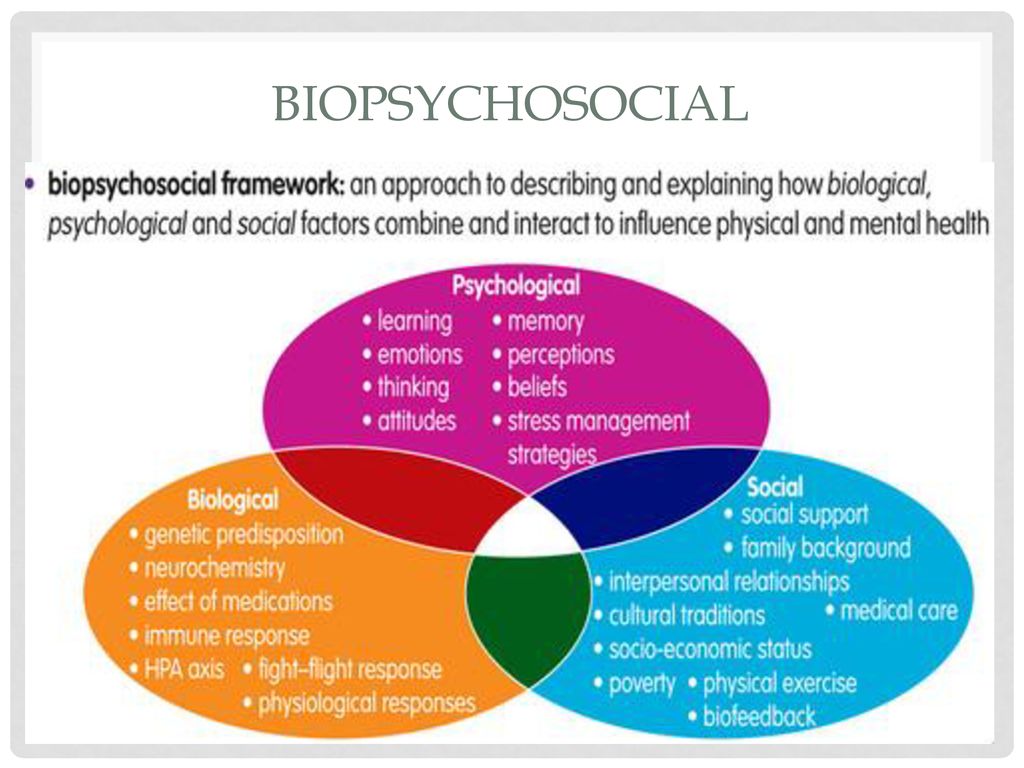

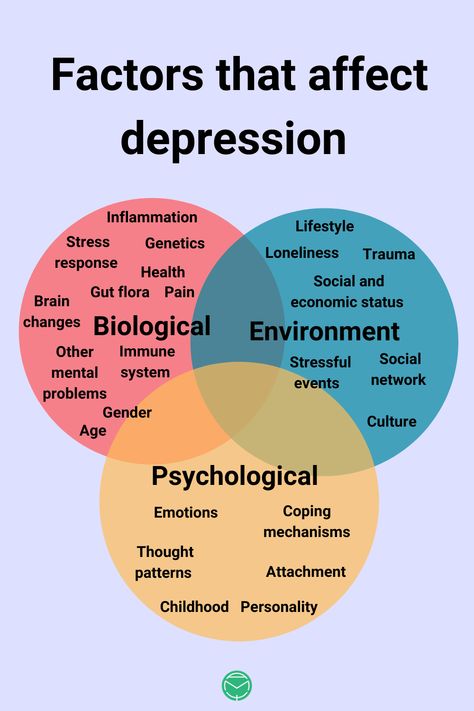

Scientists aren’t completely sure what causes mania. However, several factors are thought to contribute. Causes differ from person to person.

Causes may include:

- Family history. If you have a family member with bipolar illness, you have an increased chance of developing mania. This isn't definite though. You may never develop mania even if other family members have.

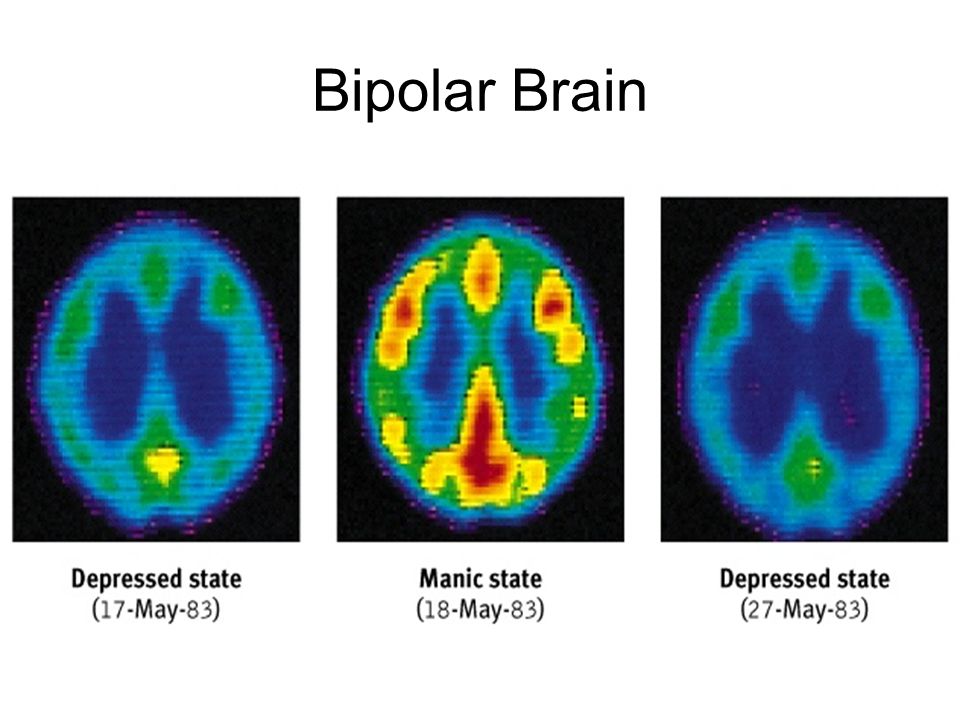

- A chemical imbalance in the brain.

- A side effect of a medication (such as some antidepressants), alcohol or recreational drugs.

- A significant change in your life, such as a divorce, house move or death of a loved one.

- Difficult life situations, such as trauma or abuse, or problems with housing, money or loneliness.

- A high level of stress and an inability to manage it.

- A lack of sleep or changes in sleep pattern.

- As a side effect of mental health problems including seasonal affective disorder, postpartum psychosis, schizoaffective disorder or other physical or neurologic condition such as brain injury, brain tumors, stroke, dementia, lupus or encephalitis.

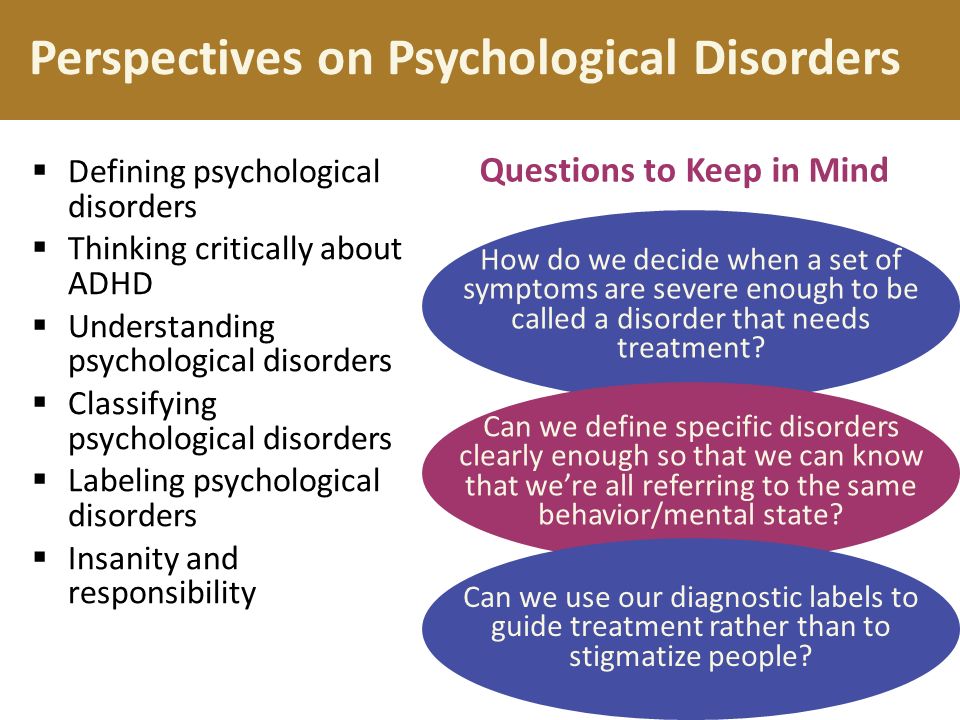

Diagnosis and Tests

How is mania diagnosed?

Your healthcare provider will ask about your medical history, family medical history, current prescriptions and non-prescription medications and any herbal products or supplements you take. Your provider may order blood tests and body scans to rule out other conditions that may mimic mania. One such condition is hyperthyroidism. If other diseases and conditions are ruled out, your provider may refer you to a mental health specialist

To be diagnosed with mania, your mental health specialist may follow the criteria of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5. Their criteria for a manic episode are:

Their criteria for a manic episode are:

- You have an abnormal, long-lasting elevated expression of emotion along with a high degree of energy and activity that lasts for at least one week and is present most of the day, nearly every day.

- You have three or more symptoms to a degree that they’re a noticeable change from your usual behavior (four symptoms if your mood is only irritable). (See the symptoms section of this article for a list of the symptoms used as criteria.)

- The mood disturbance is severe enough to cause significant harm to your social, work or school functioning or there’s a need to hospitalize you to prevent you from harming yourself or others, or you have psychotic features, such as hallucinations or delusions.

- The manic episode can’t be caused by the effects of a substance (medications or drug abuse) or another medical condition.

Management and Treatment

How is mania treated?

Mania is treated with medications, talk therapy, self-management and family and friends support.

Medications

If you have mania only, your healthcare provider may prescribe an antipsychotic medication, such as ariprazole (Abilify®), lurasidone (Latuda®), olanzapine (Zyprexa®), quetiapine (Seroquel®) or risperridone (Risperdal®).

If you have mania as part of a mood disorder, your provider may add a mood stabilizer. Some examples include lithium, valproate (Depakote®) and carbamazepine (Tegretol®). (If you’re pregnant or plan to become pregnant, let your provider know. Valproate can increase the chance of birth defects and learning disabilities and shouldn’t be prescribed to individuals who are able to become pregnant.)

Sometimes antidepressants are also prescribed.

Talk therapy (psychotherapy)

- Psychotherapy involves a variety of techniques. During psychotherapy, you’ll talk with a mental health professional who'll help you identify and work through factors that may be triggering your mania and/or depression (if you’re diagnosed with bipolar I disorder).

- Cognitive behavioral therapy can be useful in helping you change inaccurate perceptions that you have about yourself and the world around you.

- Family therapy is important since it’s very helpful for your family members to understand your behavior and what they can do to help.

Ask your provider for contact information for local support groups. You might find it helpful to talk with people with similar medical experiences and share problems, ideas for coping and strategies for living and caring for yourself.

Other treatments

Electroconvulsant therapy (ECT) may be considered in rare cases in individuals who have severe mania or depression (if bipolar). ECT involves applying brief periods of electric current to your brain.

Prevention

What steps can I take to better cope with or manage my mania?

Although episodes of mania can’t always be prevented, you can make a plan to better manage your symptoms and prevent them from getting worse when you feel a manic episode may be starting.

Some ideas to try during this time include:

- Avoid stimulating activities and environments – such as loud or busy places or bright places. Instead, choose calm and relaxing activities and environments.

- Stick to routines. Go to bed at a set time, even if you’re not tired. Also, stick to the same times for eating meals, taking medications and exercising.

- Limit the number of social contacts to keep you from getting too stimulated and excited.

- Postpone making any major life decisions and big purchases.

- Avoid people and situations that might tempt you to make poor or risky choices, such as taking recreational drugs or drinking alcohol.

- Consider selecting someone to manage your finances during a manic episode.

If you ever have thoughts of harming yourself, tell family or friends, call your healthcare provider or contact the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988. Counselors are available 24/7.

Outlook / Prognosis

What outcome can I expect if I’ve been diagnosed with mania?

If your mania is related to a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, this is a lifelong disease. Although there’s no cure for mania, medication and talk therapy (psychotherapy) can manage your condition in most cases.

Although there’s no cure for mania, medication and talk therapy (psychotherapy) can manage your condition in most cases.

Living With

How can I involve family and friends in understanding my mania?

It’s important to have an honest conversation with your family and closest friends.

- Let your family and friends know what you do and don’t find helpful. For example, if you’d appreciate a friendly reminder about taking your daily medications or a question about if you are getting enough sleep, let them know. On the other hand, if you don’t like always being asked if your current state of happiness is a sign you’re having a manic episode, discuss this.

- Ask your family and friends if they can help identify your triggers if you can’t. They may be able to spot triggers that you can’t spot yourself. Ask what they’ve noticed or any patterns they may see around the times of your episodes. As soon as you recognize an early sign, make an appointment to see your healthcare provider.

You may or may not need a medication adjustment. However, it’s good to be on alert since your symptoms could rapidly change.

You may or may not need a medication adjustment. However, it’s good to be on alert since your symptoms could rapidly change. - Describe how your symptoms feel to you. Your family and friends will have a better understanding of your condition.

- Let family and friends know what type of help you’d like from them and when you’d like it. There may be times when you feel you can cope on your own. Knowing the difference will be helpful for everyone.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is acute mania?

Acute mania is the manic phase of bipolar I disorder. It is defined as an extremely unstable euphoric or irritable mood along with an excess activity or energy level, excessively rapid thought and speech, reckless behavior and feeling of invincibility.

What is unipolar mania?

Unipolar mania is a disorder in which only excitement, excess activity or energy level and euphoric symptoms are seen. This is a rare condition.

What’s the difference between mania and hypomania?

Hypomania is a less severe form of mania. The criteria that healthcare professionals use to make the diagnosis of either hypomania or mania is what sets them apart. The differences between these two conditions are as follows:

| Mania | Hypomania | |

|---|---|---|

| How long the episode lasts. | At least one week. | At least four consecutive days. |

| Severity of episode. | Causes severe impact on social or work/school functioning. | Not severe enough to significantly affect social or work/school functioning. |

| Need for hospitalization. | Possibly. | No. |

| Psychotic symptoms present (delusions or hallucinations). | Is among possible symptoms. | Can’t be present for a diagnosis of hypomania. |

Can my diagnosis change between bipolar I disorder and bipolar II disorder?

No. Once you have a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder — even if you never have another manic episode or a psychotic event (delusions or hallucinations) — your diagnosis can never be changed to bipolar II disorder. You’ll always have a bipolar I disorder diagnosis.

Once you have a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder — even if you never have another manic episode or a psychotic event (delusions or hallucinations) — your diagnosis can never be changed to bipolar II disorder. You’ll always have a bipolar I disorder diagnosis.

A note from Cleveland Clinic

Problems can develop in your social life, work/school functioning and home life when you have symptoms of mania, which include mood swings and an abnormal level of energy and activity. You may require hospitalization if you have severe hallucinations or delusions, or to prevent you from harming yourself or others. It’s important to have a good understanding of mania, mania symptoms, your particular triggers and ways to better manage your manic episodes. Medications, talk therapy and support groups as well as support from your family and friends can help manage your mania. Stay in close contact with all your healthcare providers, especially during times of manic episodes. Your provider will want to see you and may need changes to your medications or dose.

Schizoaffective Disorder: Schizophrenia, Mood Disorder, Treatment

Overview

What is schizoaffective disorder?

Schizoaffective disorder is a serious mental health condition. It has features of two different disorders:

- “Schizo” means the psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia. This brain disorder changes how a person thinks, acts and expresses emotions. It also affects how someone perceives reality and relates to others.

- “Affective” refers to a mood disorder, or severe changes in a person’s mood, energy and behavior.

There’s no cure for schizoaffective disorder. But treatment can help people manage symptoms and improve their quality of life.

What are the types of schizoaffective disorder?

There are two types of schizoaffective disorder: bipolar schizoaffective disorder and depressive schizoaffective disorder. The two types are based on the associated mood disorder the person has:

- Bipolar disorder type: This condition features one or two types of different mood changes.

People with bipolar disorder have severe highs (mania) alone or combined with lows (depression).

People with bipolar disorder have severe highs (mania) alone or combined with lows (depression). - Depressive type: People who have depression have feelings of sadness, worthlessness and hopelessness. They may have suicidal thoughts. They may also experience concentration and memory problems.

How does schizoaffective disorder affect people?

This lifelong illness can affect all areas of a person’s life. A person with schizoaffective disorder can find it difficult to function at work or school. It also affects people’s relationships with family, friends and loved ones.Many people with schizoaffective disorder have periodic episodes. There are times when their symptoms surface and times when their symptoms might disappear for a while.

Who gets schizoaffective disorder?

The condition usually begins in the late teens or early adulthood, up to age 30. It rarely occurs in children. Studies suggest the disorder is more likely to occur in women than men.

How common is schizoaffective disorder?

Schizoaffective disorder is rare. Research estimates that 3 in every 1000 people (0.3%) will develop schizoaffective disorder in their lifetime.Still, it’s difficult to know exactly how many people have the condition because of the challenging diagnosis. People with schizoaffective disorder have symptoms of two different mental health conditions. Some people might get misdiagnosed with schizophrenia. Others might get misdiagnosed with a mood disorder.

Symptoms and Causes

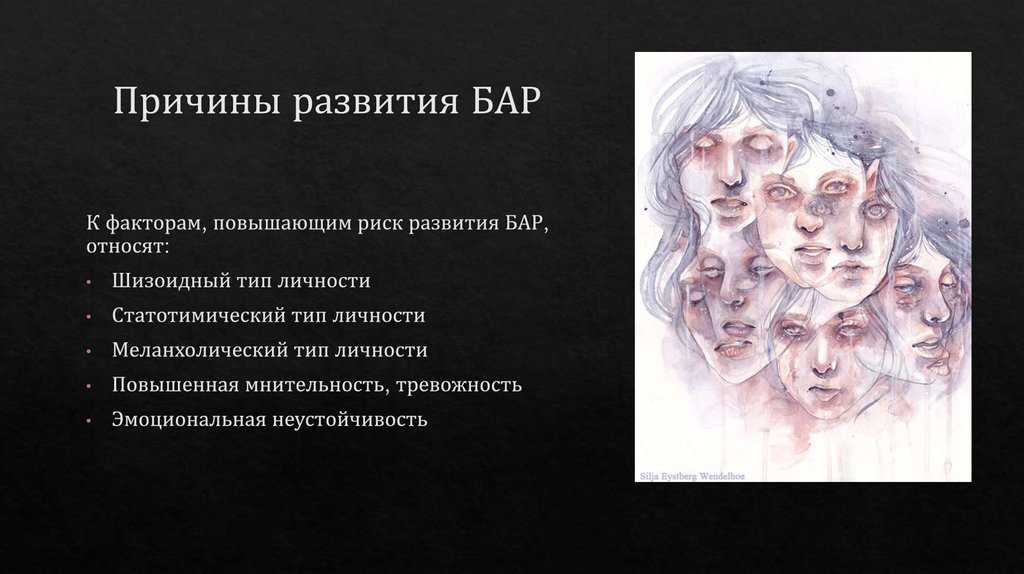

What causes schizoaffective disorder?

Researchers don’t know the exact cause of schizoaffective disorder. They believe several factors are involved:

- Genetics: Schizoaffective disorder might be hereditary. Parents may pass down the tendency to develop the condition to their children. Schizoaffective disorder can also occur in several members of an extended family.

- Brain chemistry: People with the disorder may have an imbalance of brain chemicals called neurotransmitters.

These chemicals help nerve cells in the brain communicate with each other. An imbalance can throw off these connections, leading to symptoms.

These chemicals help nerve cells in the brain communicate with each other. An imbalance can throw off these connections, leading to symptoms. - Brain structure: Abnormalities in the size or composition of different brain regions (such as the hippocampus, thalamus) may be associated with developing schizoaffective disorder.

- Environmental factors: Certain environmental factors may trigger schizoaffective disorder in people who inherited a higher risk. Factors may include highly stressful situations, emotional trauma or certain viral infections.

- Drug use: Using psychoactive drugs, such as marijuana, may lead to the development of schizoaffective disorder.

What are the symptoms of schizoaffective disorder?

Symptoms of schizoaffective disorder vary from one person to the next. They can range from mild to severe.

Someone with schizoaffective disorder experiences psychotic symptoms. They also experience severe mood changes, with symptoms of depression, mania or both.![]() A person with schizoaffective disorder will have psychotic symptoms that occur alone and with mood changes.

A person with schizoaffective disorder will have psychotic symptoms that occur alone and with mood changes.

Psychotic symptoms:

- Delusions (false beliefs with no basis in reality that the person won’t give up, even if given evidence to the contrary).

- Hallucinations (perceived sensations that aren’t real, such as hearing voices or seeing shadows).

- Inability to tell real from imaginary.

- Disorganized speech (difficulty producing clear and coherent sentences).

- Unclear thinking.

- Odd or unusual behavior.

- Paranoia.

- Lack of emotion in facial expression and speech.

- Poor motivation.

- Slow movements or inability to move.

Depression symptoms:

- Low or sad mood

- Thoughts of death or suicide.

- Feelings of worthlessness or hopelessness.

- Guilt or self-blame.

- Lack of energy and low mood

- Loss of interest in usual activities.

- Poor appetite.

- Changes in sleeping patterns (sleeping a little or a lot).

- Trouble thinking or concentrating.

- Weight loss or gain.

Mania symptoms:

- Agitation.

- Distractibility.

- Increased or rapid talking.

- Increased work, social and sexual activity.

- Inflated self-esteem.

- Not sleeping much.

- Rapid or racing thoughts.

- Self-destructive or dangerous behavior (spending sprees, reckless driving, unsafe sex).

Diagnosis and Tests

How is schizoaffective disorder diagnosed?

If someone is showing symptoms of schizophrenia and a mood disorder, see a healthcare provider. The provider will do a medical history and physical examination. There are no lab tests to diagnose schizoaffective disorder. But the provider may use X-rays and blood tests to rule out other illnesses that may be causing the symptoms.

If there is no physical cause for the symptoms, the provider may refer the person to a psychiatrist or psychologist. These professionals specialize in diagnosing and treating conditions tied to mental and behavioral health.

These professionals specialize in diagnosing and treating conditions tied to mental and behavioral health.

How does a psychiatrist or psychologist diagnose schizoaffective disorder?

Mental health professionals use specially designed interview and assessment tools to diagnose psychotic disorders. They listen to the person (or a loved one) describe the symptoms. They also watch the person’s speech, movement and behavior.

Providers figure out if these symptoms and behaviors match a specific disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). The American Psychiatric Association publishes the DSM-5. It’s considered the reference book for mental health conditions.

According to the DSM-5, a person has schizoaffective disorder if they have:

- Periods of uninterrupted mental illness, such as having symptoms of depression or another mood disorder for a long time.

- Episode of mania, major depression or both while also having symptoms of schizophrenia.

- At least two weeks of psychotic symptoms (such as delusions or hallucinations) without mood symptoms.

- No evidence of a substance use disorder or medications that may be causing the symptoms.

Management and Treatment

How is schizoaffective disorder treated?

Treatment for schizoaffective disorder involves medication combined with psychotherapy and skills training. The medication helps stabilize the person’s mood and treats the psychotic symptoms. The therapy and skills training help improve their relationships and coping skills.

What medications treat schizoaffective disorder?

The provider will figure out the right medicine based on the type of mood disorder the person has:

- Antipsychotics: This is the primary medicine used to treat the psychotic symptoms that come with schizophrenia — for example, delusions, hallucinations and disordered thinking.

- Antidepressants: An antidepressant or mood stabilizer such as lithium can help treat mood-related symptoms.

Sometimes, a person needs both an antidepressant and an antipsychotic.

Sometimes, a person needs both an antidepressant and an antipsychotic.

How does psychotherapy treat schizoaffective disorder?

During therapy, the person talks to a trained mental health professional. The goal of psychotherapy is for the person to:

- Learn about the illness.

- Establish goals.

- Manage everyday problems related to the disorder.

Family therapy can also help. A therapist can help families learn how to cope with the illness and support their loved one. Family therapy helps improve symptoms and quality of life for the person with the disorder.

How does skills training help a person with schizoaffective disorder?

This type of counseling helps a person manage their everyday lives better. It often focuses on:

- Day-to-day activities, such as money and home management.

- Grooming and hygiene.

- Social skills.

- Work.

Does someone with schizoaffective disorder need to be hospitalized?

Most people with this disorder can get outpatient treatment. They go to a clinic or hospital for treatment during the day and then return home. Sometimes, people have severe symptoms, though, or they’re in danger of harming themselves or others. They may need to be hospitalized to stabilize their condition.

They go to a clinic or hospital for treatment during the day and then return home. Sometimes, people have severe symptoms, though, or they’re in danger of harming themselves or others. They may need to be hospitalized to stabilize their condition.

Are there side effects of schizoaffective treatment?

The medications may cause side effects.

Side effects of lithium:

- Dizziness.

- Hand tremors.

- Loss of appetite.

- Low thyroid hormone.

- Mild diarrhea.

- Nausea.

Side effects of antidepressants (varies depending on the type of antidepressant):

- Constipation or diarrhea.

- Dry mouth.

- Headache.

- Sexual problems (including delayed orgasm or erectile dysfunction).

- Sleepiness or trouble sleeping.

- Sweating.

- Weight gain or loss.

Side effects of antipsychotic medications:

- Drowsiness.

- Increased cholesterol and triglycerides.

- Increased risk of diabetes.

- Slow movements.

- Weight gain.

Prevention

Can schizoaffective disorder be prevented?

There’s no way to prevent schizoaffective disorder. But make sure to get an early diagnosis and treatment if you start noticing symptoms, either in yourself or a loved one. Prompt treatment helps avoid or reduce frequent relapses and hospitalizations. It can also decrease the disruption to the person’s life, family and relationships.

What other conditions might a person with schizoaffective disorder have?

A person with schizoaffective disorder may have other mental health conditions as well, including:

- Anxiety disorder.

- Substance use disorder.

- Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Outlook / Prognosis

What’s the outlook for schizoaffective disorder?

There’s no cure for schizoaffective disorder. But treatment can help. The right combination of medication and therapy can:

But treatment can help. The right combination of medication and therapy can:

- Help the person cope with the disorder.

- Improve social functioning.

- Lessen symptoms.

Living With

How should I take care of myself (or a loved one) when it comes to schizoaffective disorder?

Perhaps you’ve noticed signs of schizoaffective disorder in yourself or a loved one. Those symptoms may include prolonged hallucinations, delusions, depression or manic episodes. The first step is to talk to a healthcare provider. Getting diagnosis and treatment as soon as possible helps improve symptoms and promote a good quality of life. Be sure to follow your provider’s treatment instructions:

- Attend therapy sessions, including individual and family therapy.

- Stay in contact with your provider, who can help manage and adjust your treatments as necessary.

- Take medications as directed.

Talk to your provider to help manage side effects from the medications.

Talk to your provider to help manage side effects from the medications. - Treat substance use disorders, if necessary.

When should I go to the emergency room?

If you or a loved one seems in danger of harming themselves or others, get help right away. Go to an emergency room, call 911, or call the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988. This national network of local crisis centers provides free, confidential emotional support to people in suicidal crisis or emotional distress. It’s available 24/7.

What else should I ask my healthcare provider?

If you or a loved one has schizoaffective disorder, ask your provider:

- What medication will help?

- What other therapy can help?

- Will this disorder ever go away?

- How long will treatment continue?

- Is there a higher risk for other conditions or disorders?

A note from Cleveland Clinic

Schizoaffective disorder is a serious mental health condition. It has features of both schizophrenia and a mood (affective) disorder. Schizoaffective symptoms may include symptoms of mania, depression and psychosis. It’s important to get treatment as soon as possible. If you notice symptoms of schizoaffective disorder, talk to a healthcare provider. Treatment for schizoaffective disorder includes medication and therapy. While there’s no cure for this disorder, treatment helps improve people’s symptoms and quality of life.

It has features of both schizophrenia and a mood (affective) disorder. Schizoaffective symptoms may include symptoms of mania, depression and psychosis. It’s important to get treatment as soon as possible. If you notice symptoms of schizoaffective disorder, talk to a healthcare provider. Treatment for schizoaffective disorder includes medication and therapy. While there’s no cure for this disorder, treatment helps improve people’s symptoms and quality of life.

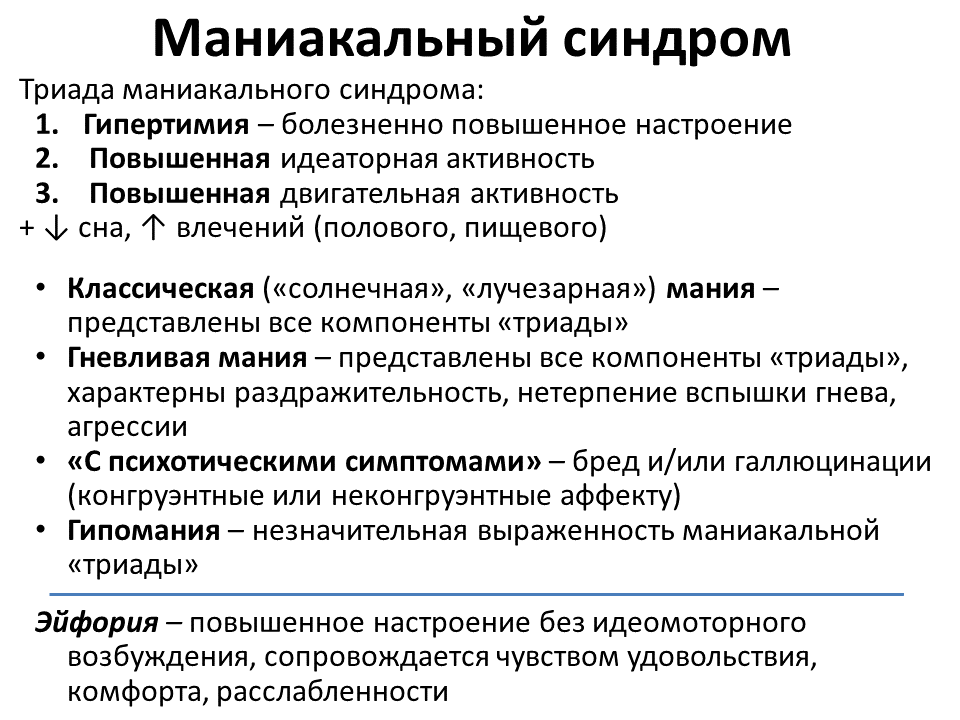

Manic disorders

Classification of manic episodes by severity includes hypomania, mania without psychotic episodes, and mania with psychotic episodes.

Under hypomania understand a mild degree of mania, in which changes in mood and behavior are long-term and pronounced, not accompanied by delusions and hallucinations. An elated mood manifests itself in the sphere of emotions as a joyful cloudlessness, irritability, in the sphere of speech - as increased talkativeness with ease and superficial judgments, increased contact. In the field of behavior, there is an increase in appetite, sexuality, distractibility, a decrease in the need for sleep, and individual actions that go beyond morality. Ease of associations, increase in working capacity and creative productivity are subjectively felt. Objectively, the number of social contacts and success increase. At the same time, there are episodes of reckless or irresponsible behavior, increased sociability or familiarity.

In the field of behavior, there is an increase in appetite, sexuality, distractibility, a decrease in the need for sleep, and individual actions that go beyond morality. Ease of associations, increase in working capacity and creative productivity are subjectively felt. Objectively, the number of social contacts and success increase. At the same time, there are episodes of reckless or irresponsible behavior, increased sociability or familiarity.

The main criterion for diagnosis is an elevated or irritable mood that is abnormal for the individual, persists for at least several days, and is accompanied by the above symptoms.

It should be noted that hypomanic episodes are possible in some somatic and psychiatric disorders. For example, with hyperthyroidism, anorexia or therapeutic starvation in the phase of food arousal; with intoxication with certain psychoactive substances - PAS (amphetamines, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine), however, there are other manifestations of somatic and mental pathology and PAS intoxication.

In its typical form , an extended manic state is manifested by the so-called manic triad: a painfully elevated mood, an accelerated flow of thoughts, and motor excitation. The leading sign of a manic state is a manic affect, manifested in an elevated mood, a feeling of happiness, contentment, well-being, an influx of pleasant memories and associations. It is characterized by an aggravation of sensations and perceptions, an increase in mechanical and some weakening of logical memory, superficial thinking, lightness and unproductiveness of judgments and conclusions, ideas of reassessment of one's own personality , up to delusional ideas of greatness, disinhibition of drives and weakening of higher feelings, instability, ease of switching attention.

Mania without psychotic symptoms. The main difference from hypomania is that elevated mood affects the change in the norms of social functioning, manifests itself in inadequate actions that are not controlled by the patient. The pace of the passage of time accelerates and the need for sleep is significantly reduced. Tolerance and need for alcohol increase, sexual energy and appetite increase, there is a craving for travel and adventure. Thanks to the leap of ideas, many plans arise, the implementation of which is not carried out. The patient strives for bright and flashy clothes, speaks in a loud voice, incurs a lot of debt and gives money to people he hardly knows. He easily falls in love and is sure of the love of the whole world for himself. Gathering a lot of random people, he arranges holidays on credit. There is reckless driving, a marked increase in sexual energy, or sexual promiscuity. There are no hallucinations or delusions, although there may be perceptual disturbances (eg, subjective hyperacusis, vivid color perception).

The pace of the passage of time accelerates and the need for sleep is significantly reduced. Tolerance and need for alcohol increase, sexual energy and appetite increase, there is a craving for travel and adventure. Thanks to the leap of ideas, many plans arise, the implementation of which is not carried out. The patient strives for bright and flashy clothes, speaks in a loud voice, incurs a lot of debt and gives money to people he hardly knows. He easily falls in love and is sure of the love of the whole world for himself. Gathering a lot of random people, he arranges holidays on credit. There is reckless driving, a marked increase in sexual energy, or sexual promiscuity. There are no hallucinations or delusions, although there may be perceptual disturbances (eg, subjective hyperacusis, vivid color perception).

The main symptom is an elevated, expansive, irritable (angry) or suspicious mood, which is not characteristic of this individual. The change in mood should be distinct and persist throughout the week.

Mania with psychotic symptoms. It is a pronounced mania with a bright jump of ideas and manic excitement, to which secondary crazy ideas of greatness, high origin, hypereroticity, value join. There may be hallucinatory hails confirming the significance of the person, or "voices" telling the patient about emotionally neutral things, or delusions of meaning and persecution. The greatest difficulty lies in the differential diagnosis with schizoaffective disorders, however, with these disorders, there should be symptoms characteristic of schizophrenia, and delusions with them are less consistent with mood. However, the diagnosis can be considered as the starting point for the assessment of schizoaffective disorder (first episode).

Mental disorder formerly referred to as manic-depressive psychosis (MDP). It is characterized by repeated (at least two) manic, depressive and mixed episodes that alternate without a definite sequence. A feature of this psychosis is the presence of light interphase gaps (intermissions), in which all signs of the disease disappear, a complete restoration of a critical attitude to the transferred painful condition is observed, premorbid characterological and personal properties, professional knowledge and skills are preserved. Its non-psychotic form (cyclothymia) in clinical terms is a reduced (weakened, outpatient) variant of the disease.

Manic episodes usually start suddenly and last from two weeks to 4-5 months (mean episode duration about 4 months). Depression tends to last longer (average duration about 6 months), although rarely more than a year (excluding elderly patients). Both episodes often follow stressful situations or trauma, although their presence is not required for a diagnosis. The first episode can occur at any age. The frequency of episodes and the pattern of remissions and exacerbations are highly variable, but remissions tend to shorten with age, and depressions become more frequent and prolonged after middle age.

Although the earlier concept of manic-depressive disorder included patients who suffered only from depression, the term MDP is now used mainly as a synonym for bipolar disorder.

ATTENTION!!! Self-medication is not allowed in any cases, a psychotherapist is needed

Bipolar disorder | Symptoms, complications, diagnosis and treatment

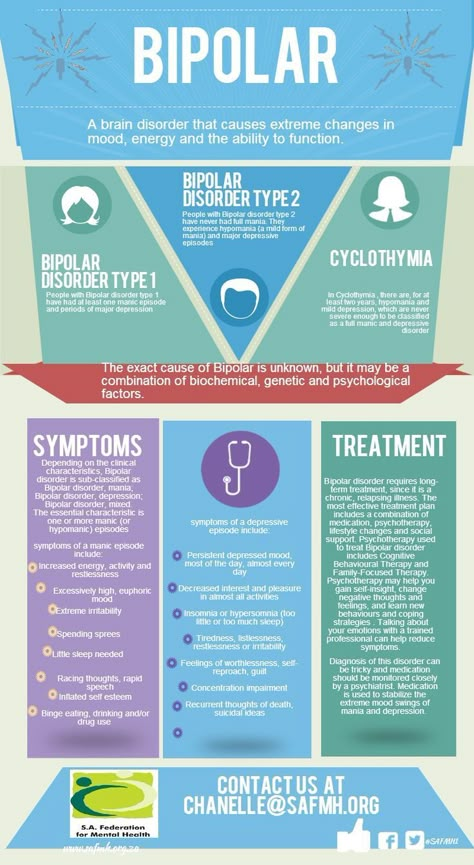

Bipolar disorder, formerly called manic depression, is a mental health condition that causes extreme mood swings that include emotional highs (mania or hypomania) and lows (depression). Episodes of mood swings may occur infrequently or several times a year.

When you become depressed, you may feel sad or hopeless and lose interest or pleasure in most activities. When the mood shifts to mania or hypomania (less extreme than mania), you may feel euphoric, full of energy or unusually irritable. These mood swings can affect sleep, energy, alertness, judgment, behavior, and the ability to think clearly.

Although bipolar disorder is a lifelong condition, you can manage your mood swings and other symptoms by following a treatment plan. In most cases, bipolar disorder is treated with medication and psychological counseling (psychotherapy).

Symptoms

There are several types of bipolar and related disorders. These may include mania, hypomania, and depression. The symptoms can lead to unpredictable changes in mood and behavior, leading to significant stress and difficulty in life.

- Bipolar I. You have had at least one manic episode, which may be preceded or accompanied by hypomanic or major depressive episodes.

In some cases, mania can cause a break with reality (psychosis).

- Bipolar disorder II. You have had at least one major depressive episode and at least one hypomanic episode, but never had a manic episode.

- Cyclothymic disorder. You have had at least two years - or one year in children and adolescents - many periods of hypomanic symptoms and periods of depressive symptoms (though less severe than major depression).

- Other types. These include, for example, bipolar and related disorders caused by certain drugs or alcohol or due to health conditions such as Cushing's disease, multiple sclerosis or stroke.

Bipolar II is not a milder form of Bipolar I but is a separate diagnosis. Although bipolar I manic episodes can be severe and dangerous, people with bipolar II can be depressed for longer periods of time, which can cause significant impairment.

Although bipolar disorder can occur at any age, it is usually diagnosed in adolescence or early twenties. Symptoms can vary from person to person, and symptoms can change over time.

Mania and hypomania

Mania and hypomania are two different types of episodes, but they share the same symptoms. Mania is more pronounced than hypomania and causes more noticeable problems at work, school, and social activities, as well as relationship difficulties. Mania can also cause a break with reality (psychosis) and require hospitalization.

Both a manic and a hypomanic episode include three or more of these symptoms:

- Abnormally optimistic or nervous

- Increased activity, energy or excitement

- Exaggerated sense of well-being and self-confidence (euphoria)

- Reduced need for sleep

- Unusual talkativeness

- Distractibility

- Poor decision-making - for example, in speculation, in sexual encounters, or in irrational investments

Major depressive episode

Major depressive episode includes symptoms that are severe enough to cause noticeable difficulty in daily activities such as work, school, social activities, or relationships. Episode includes five or more of these symptoms:

- Depressed mood, such as feeling sad, empty, hopeless, or tearful (in children and adolescents, depressed mood may manifest as irritability)

- Marked loss of interest or feeling of displeasure in all (or nearly all) activities

- Significant weight loss with no diet, weight gain, or decreased or increased appetite (in children, failure to gain weight as expected may be a sign of depression)

- Either insomnia or sleeping too much

- Either anxiety or slow behavior

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt

- Decreased ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness

- Thinking, planning or attempting suicide

Other features of bipolar disorder

Signs and symptoms of bipolar I and bipolar II disorder may include other signs such as anxiety disorder, melancholia, psychosis, or others.