Major depressive disorder atypical features

SAMHSA’s National Helpline | SAMHSA

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Main page content

-

SAMHSA’s National Helpline is a free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year treatment referral and information service (in English and Spanish) for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

Also visit the online treatment locator.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357) (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

Also visit the online treatment locator, or send your zip code via text message: 435748 (HELP4U) to find help near you. Read more about the HELP4U text messaging service.

The service is open 24/7, 365 days a year.

English and Spanish are available if you select the option to speak with a national representative. Currently, the 435748 (HELP4U) text messaging service is only available in English.

In 2020, the Helpline received 833,598 calls. This is a 27 percent increase from 2019, when the Helpline received a total of 656,953 calls for the year.

The referral service is free of charge. If you have no insurance or are underinsured, we will refer you to your state office, which is responsible for state-funded treatment programs. In addition, we can often refer you to facilities that charge on a sliding fee scale or accept Medicare or Medicaid. If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

The service is confidential. We will not ask you for any personal information. We may ask for your zip code or other pertinent geographic information in order to track calls being routed to other offices or to accurately identify the local resources appropriate to your needs.

No, we do not provide counseling. Trained information specialists answer calls, transfer callers to state services or other appropriate intake centers in their states, and connect them with local assistance and support.

-

Suggested Resources

What Is Substance Abuse Treatment? A Booklet for Families

Created for family members of people with alcohol abuse or drug abuse problems. Answers questions about substance abuse, its symptoms, different types of treatment, and recovery. Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.

Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.It's Not Your Fault (NACoA) (PDF | 12 KB)

Assures teens with parents who abuse alcohol or drugs that, "It's not your fault!" and that they are not alone. Encourages teens to seek emotional support from other adults, school counselors, and youth support groups such as Alateen, and provides a resource list.After an Attempt: A Guide for Taking Care of Your Family Member After Treatment in the Emergency Department

Aids family members in coping with the aftermath of a relative's suicide attempt. Describes the emergency department treatment process, lists questions to ask about follow-up treatment, and describes how to reduce risk and ensure safety at home.Family Therapy Can Help: For People in Recovery From Mental Illness or Addiction

Explores the role of family therapy in recovery from mental illness or substance abuse. Explains how family therapy sessions are run and who conducts them, describes a typical session, and provides information on its effectiveness in recovery.

For additional resources, please visit the SAMHSA Store.

Last Updated: 08/30/2022

SAMHSA Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator

HomeWelcome to the Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator, a confidential and anonymous source of information for persons seeking treatment facilities in the United States or U.S. Territories for substance use/addiction and/or mental health problems.

PLEASE NOTE: Your personal information and the search criteria you enter into the Locator is secure and anonymous. SAMHSA does not collect or maintain any information you provide.

Please enter a valid location.

please type your address

-

FindTreatment.

gov

gov Millions of Americans have a substance use disorder. Find a treatment facility near you.

-

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline

Call or text 988

Free and confidential support for people in distress, 24/7.

-

National Helpline

1-800-662-HELP (4357)

Treatment referral and information, 24/7.

-

Disaster Distress Helpline

1-800-985-5990

Immediate crisis counseling related to disasters, 24/7.

- Overview

- Locator OverviewLocator Overview

- Locator OverviewLocator Overview

- Finding Treatment

- Find Facilities for VeteransFind Facilities for Veterans

- Find Facilities for VeteransFind Facilities for Veterans

- Facility Directors

- Register a New FacilityRegister a New Facility

- Register a New FacilityRegister a New Facility

- Other Locator Functionalities

- Download Search ResultsDownload Search Results

- Use Google MapsUse Google Maps

- Print Search ResultsPrint Search Results

- Use Google MapsUse Google Maps

- Icon from Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers). - Icon from Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers). Find programs providing methadone for the treatment of opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

The Locator is authorized by the 21st Century Cures Act (Public Law 114-255, Section 9006; 42 U.S.C. 290bb-36d). SAMHSA endeavors to keep the Locator current. All information in the Locator is updated annually from facility responses to SAMHSA’s National Substance Use and Mental Health Services Survey (N-SUMHSS). New facilities that have completed an abbreviated survey and met all the qualifications are added monthly. Updates to facility names, addresses, telephone numbers, and services are made weekly for facilities informing SAMHSA of changes. Facilities may request additions or changes to their information by sending an e-mail to [email protected], by calling the BHSIS Project Office at 1-833-888-1553 (Mon-Fri 8-6 ET), or by electronic form submission using the Locator online application form (intended for additions of new facilities).

Updates to facility names, addresses, telephone numbers, and services are made weekly for facilities informing SAMHSA of changes. Facilities may request additions or changes to their information by sending an e-mail to [email protected], by calling the BHSIS Project Office at 1-833-888-1553 (Mon-Fri 8-6 ET), or by electronic form submission using the Locator online application form (intended for additions of new facilities).

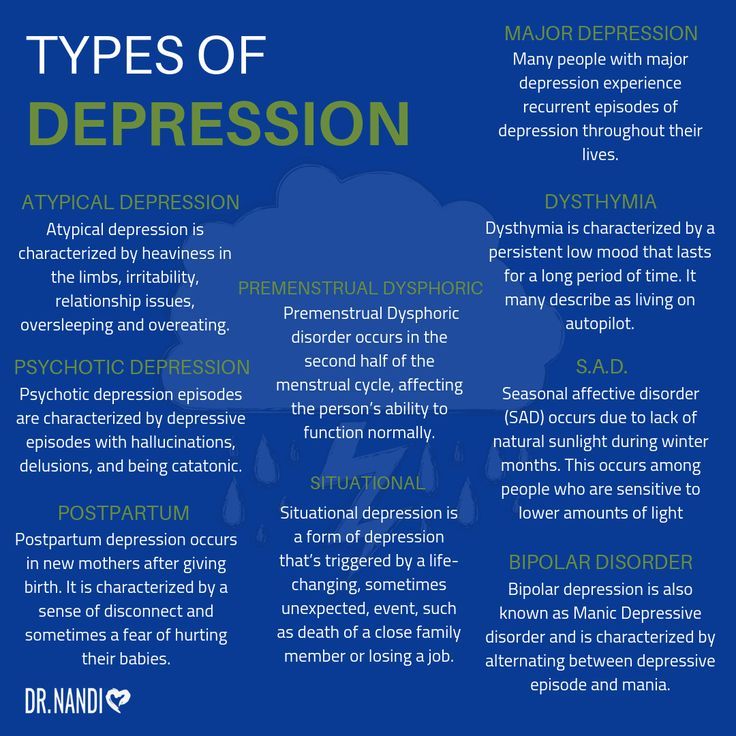

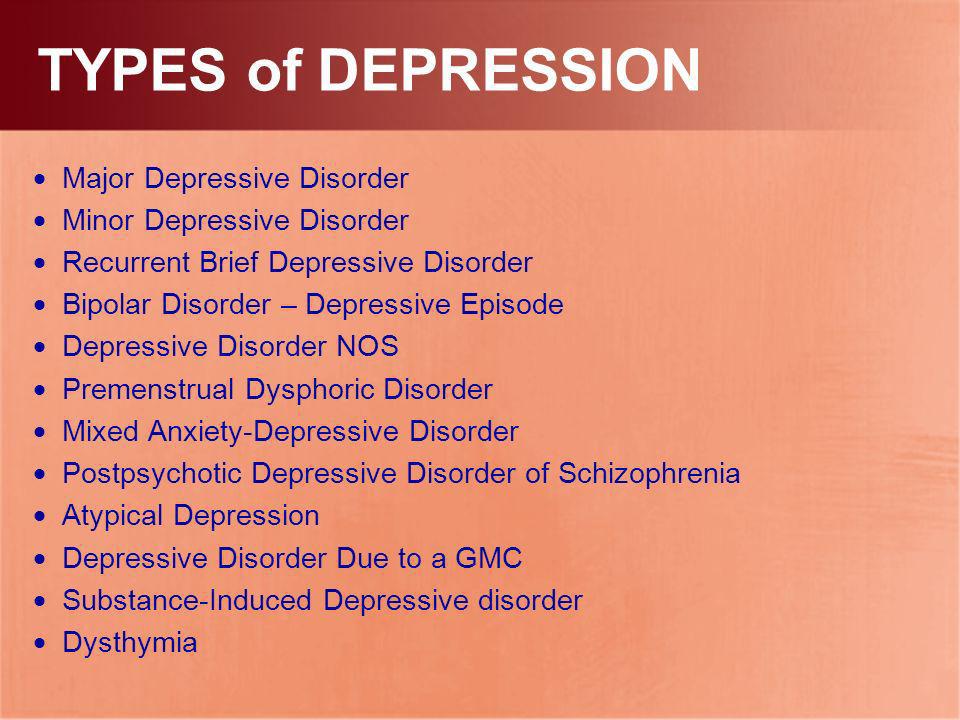

Major depressive disorders (clinical depression)

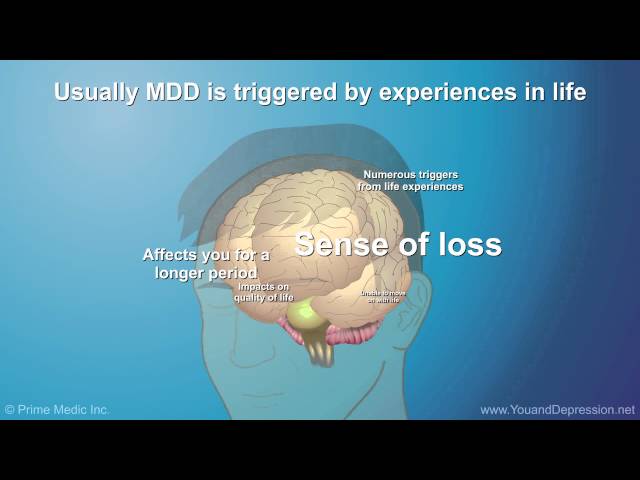

Depression is different from normal mood swings and short-term emotional responses to everyday problems. Prolonged moderate to severe depression can become a serious illness. This results in patients suffering greatly and doing poorly at work, at school and have problems in their families. At its worst, depression can lead to suicide.

Depression is a common illness worldwide, affecting more than 264 million people. Major depressive disorder is one of the most common forms of mental illness, affecting approximately one in six men and one in four women in their lives.

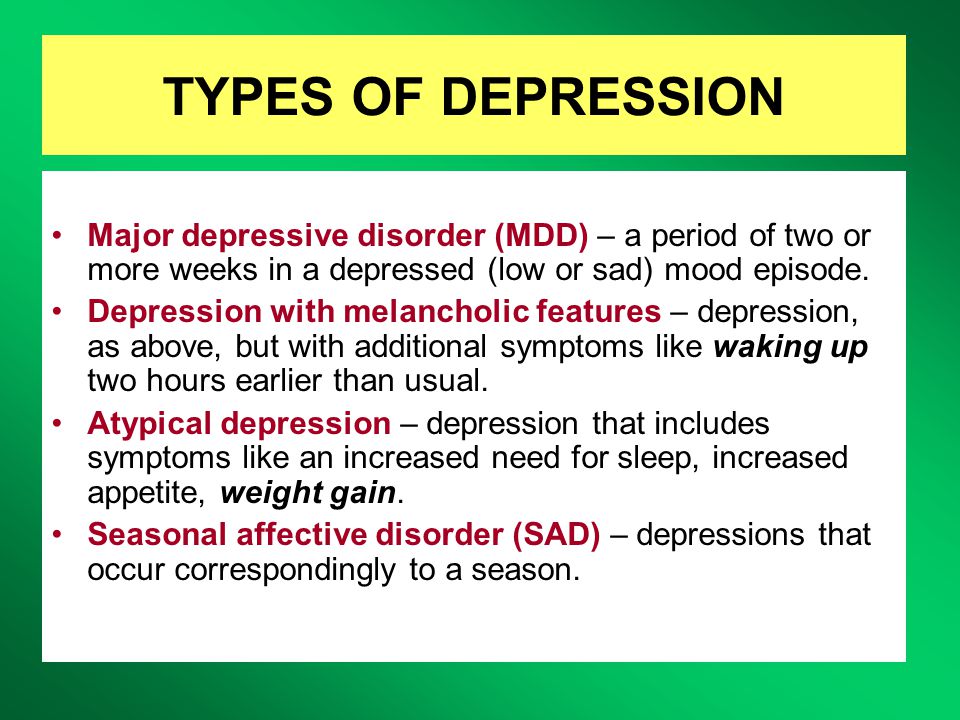

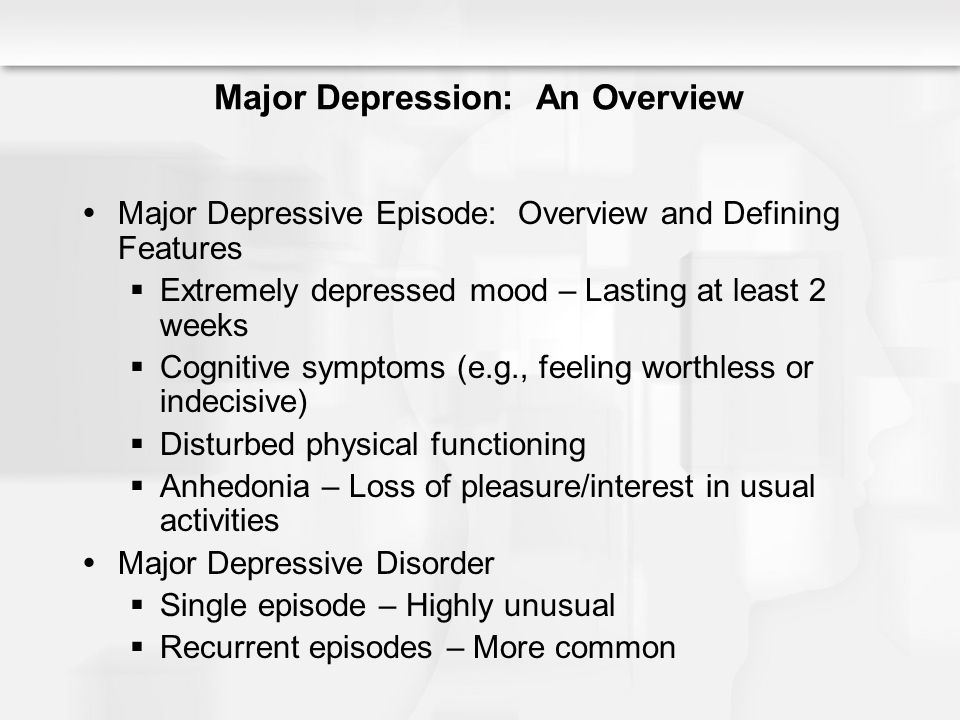

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a severe condition characterized by low mood, decreased interests, poor cognitive function, and autonomic symptoms such as disturbed sleep or eating. MDD can develop in one in six adults during their lifetime and affects about twice as many women as men.

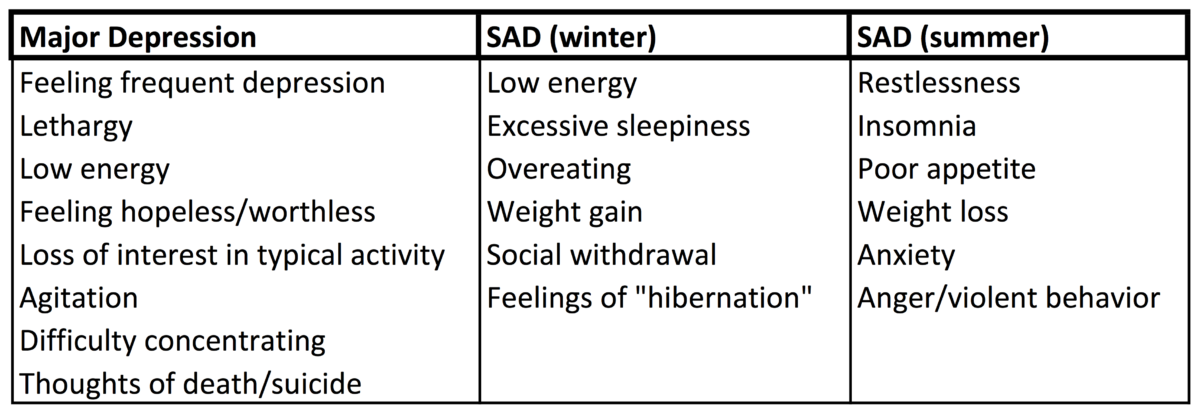

Main symptoms of depressive disorder

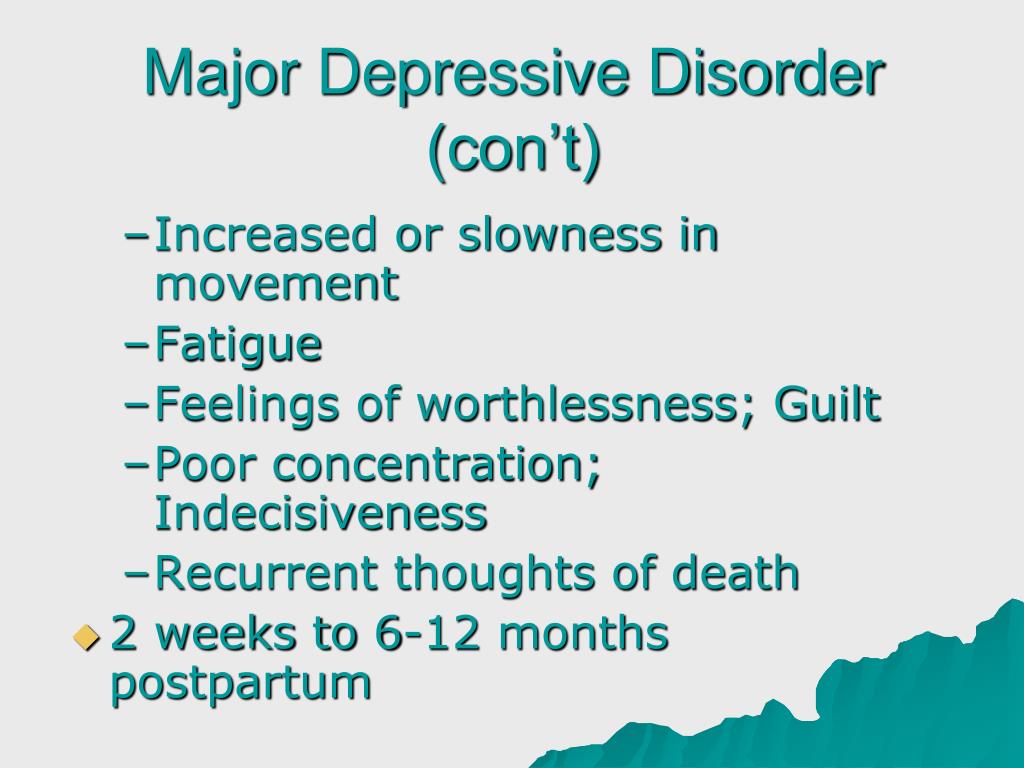

Symptoms of major depressive disorder (MDD) may include:

- depression almost every day

- loss of interest in activities you once enjoyed

- changes in appetite or weight

- sleep problems

- feeling lazy or restless

- low energy

- feelings of hopelessness or worthlessness

- trouble concentrating

- frequent thoughts of death or suicide

Recurrent depression:

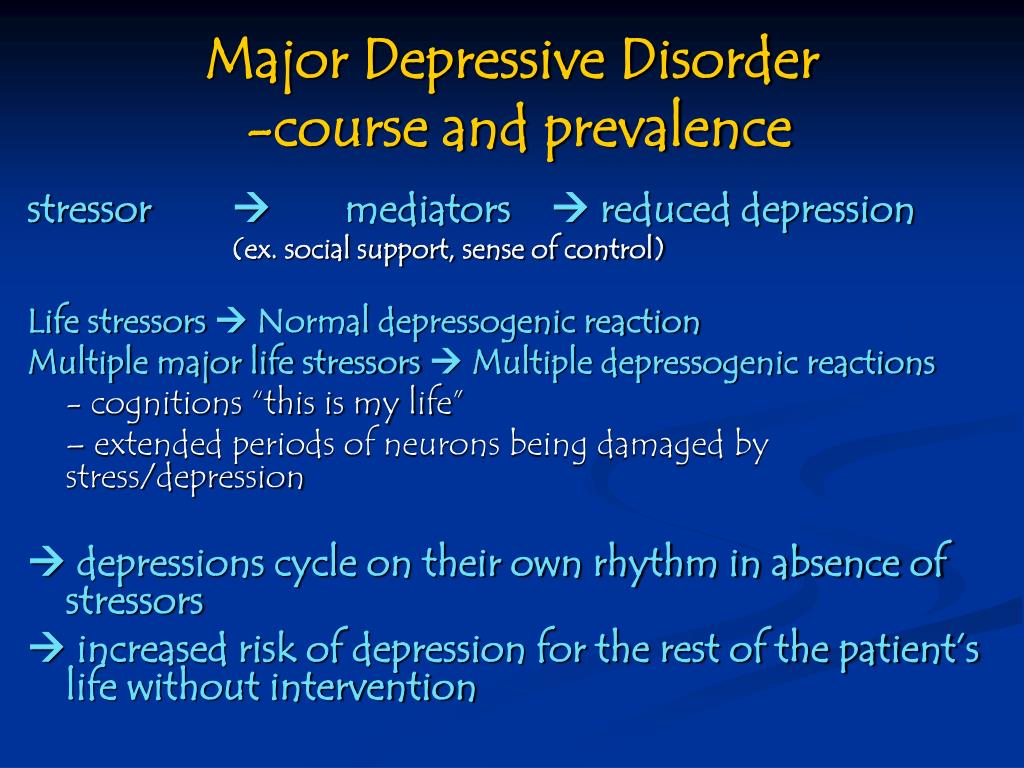

This is a highly relapsing condition: at least 50% of people recovering from a first episode of depression have at least one additional episode in their lifetime, and about 80% of people have a history of two recurrent episodes.

Episodes typically recur within five years of the first episode, and the average person with a history of depression will have five to nine depressive episodes in their lifetime.

Symptoms of recurrent depression:

- difficulty concentrating

- disturbed sleep

- reduced energy level

- constant light alarm

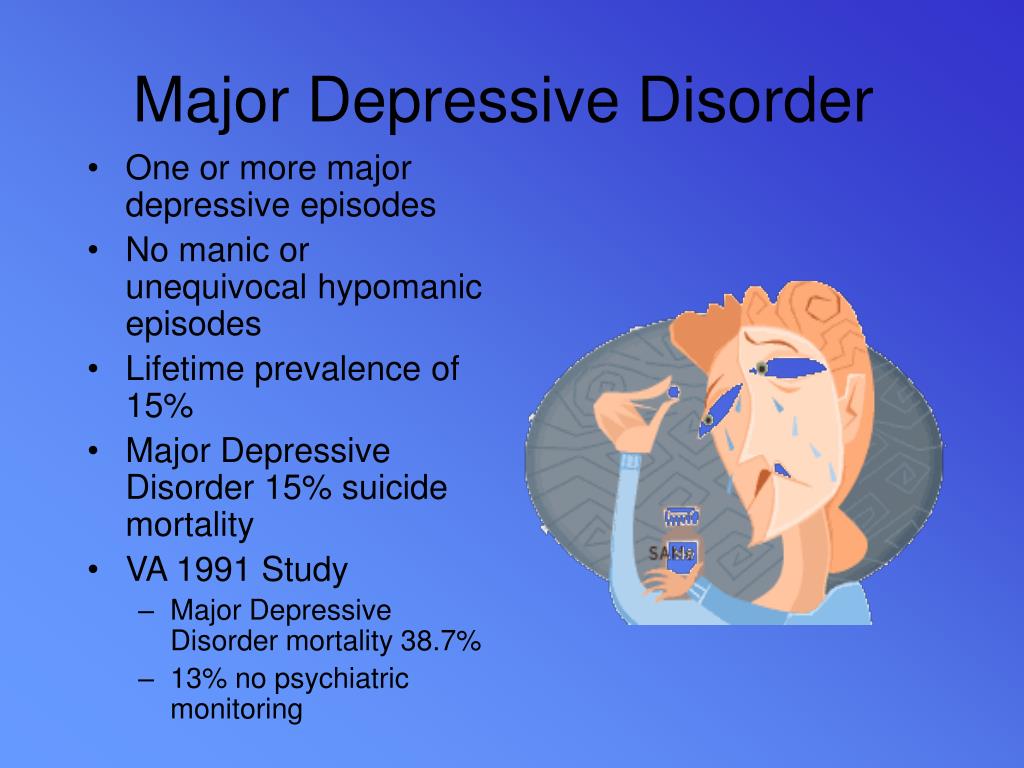

Major depression in adults:

Depression is a common adult disorder that often leads to poor quality of life and impaired role functioning. Depression is also associated with high rates of suicidal behavior and death. When depression occurs in the context of a medical illness, it is associated with increased healthcare costs, longer hospital stays, poor collaboration in treatment, etc.

Causes of depression in adults may be related to the difficulty of changing roles:

- low education and low income

- early pregnancy and childbirth

- divorces

- unstable work

- highly competitive and hard work

Major symptoms of depression in adults include:

- Mostly sad or depressed mood

- Loss of interest or pleasure and avoidance of social gatherings

- Decreased energy and frequent fatigue

- Decreased concentration and attention

- Decreased self-esteem and self-confidence

- Thoughts on guilt and unworthiness

- A gloomy and pessimistic view of the future

- Thoughts or actions of harming oneself or suicidal thoughts

- Sleep disturbance or insomnia

- Pronounced or reduced appetite

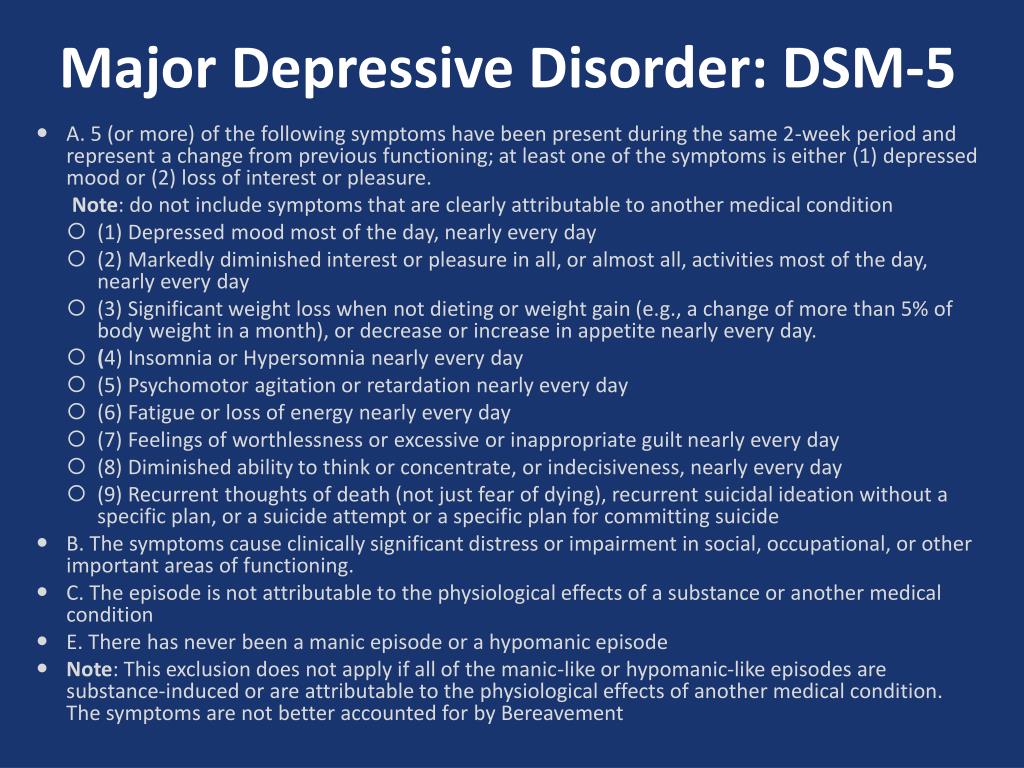

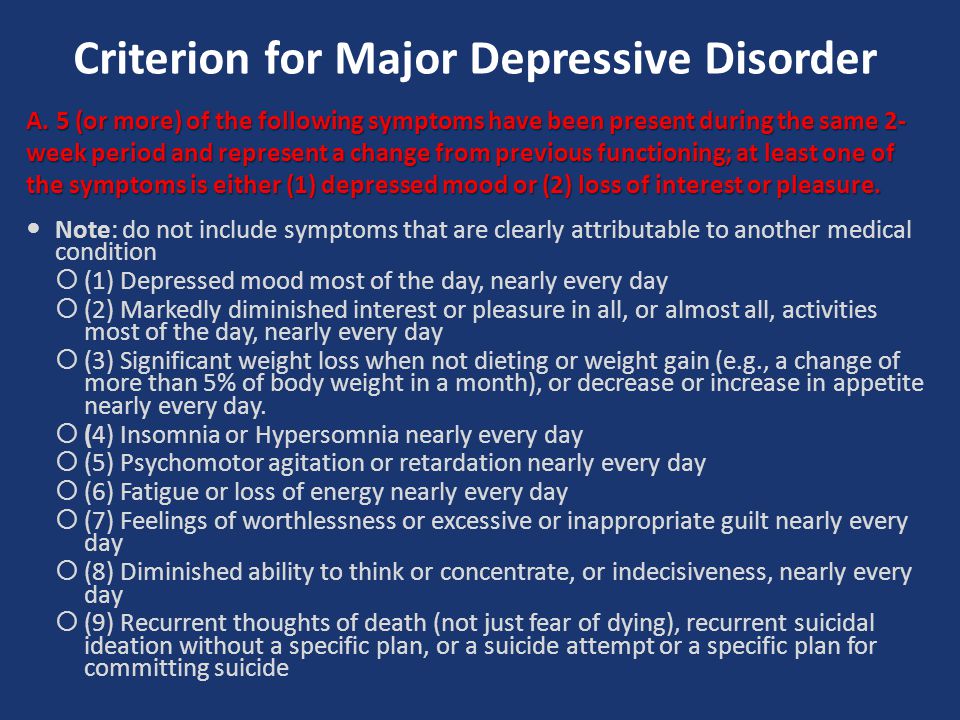

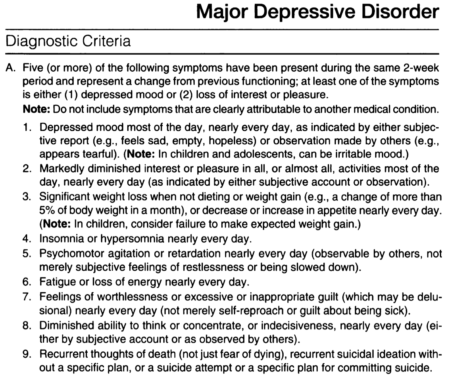

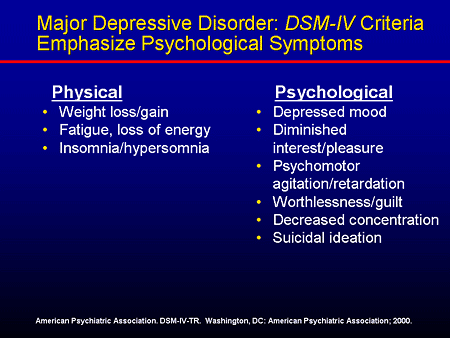

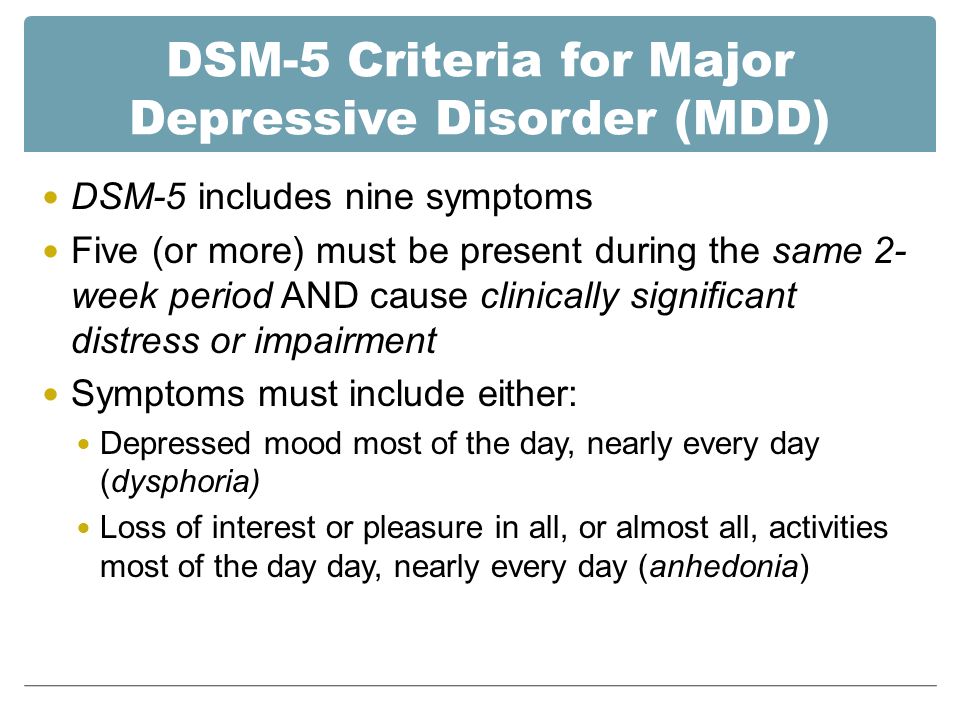

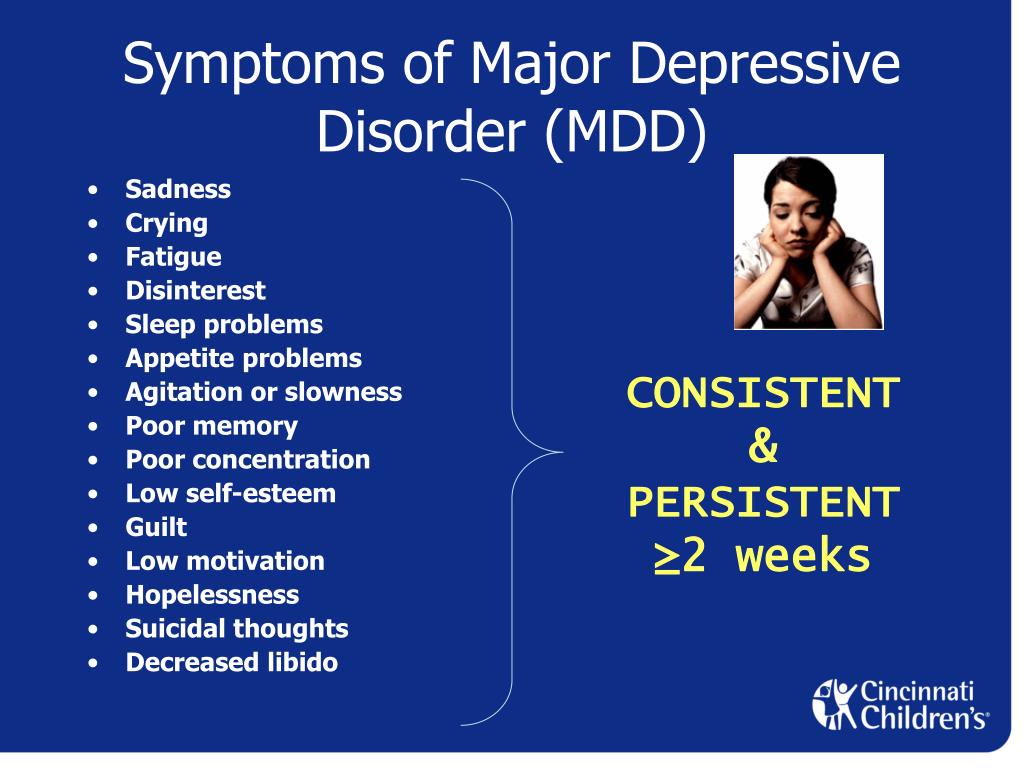

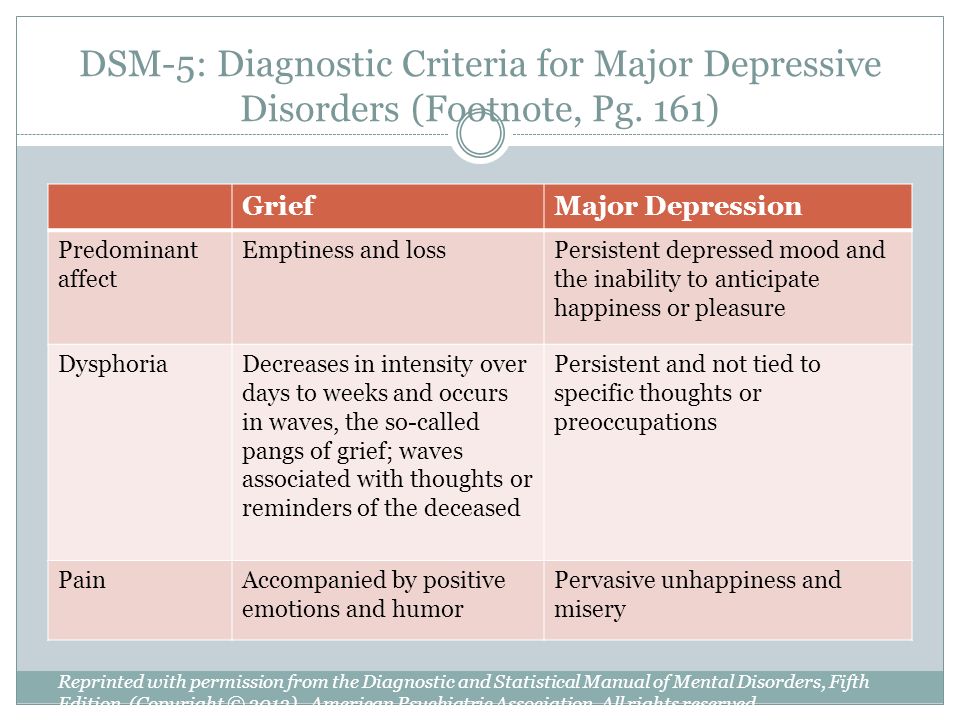

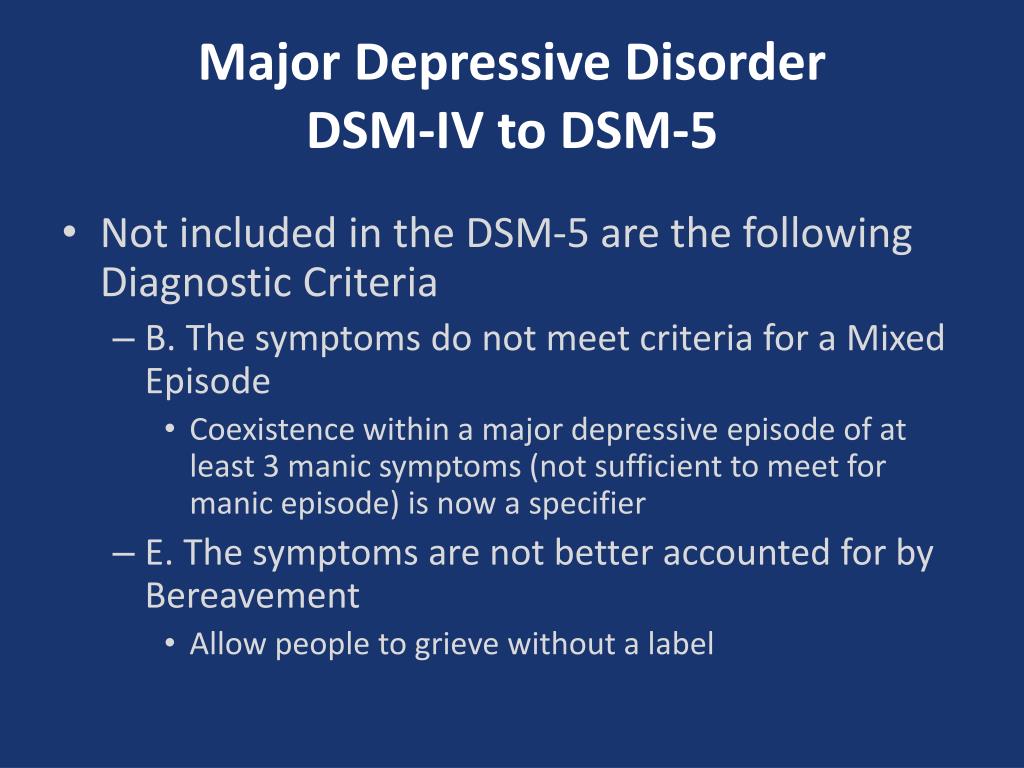

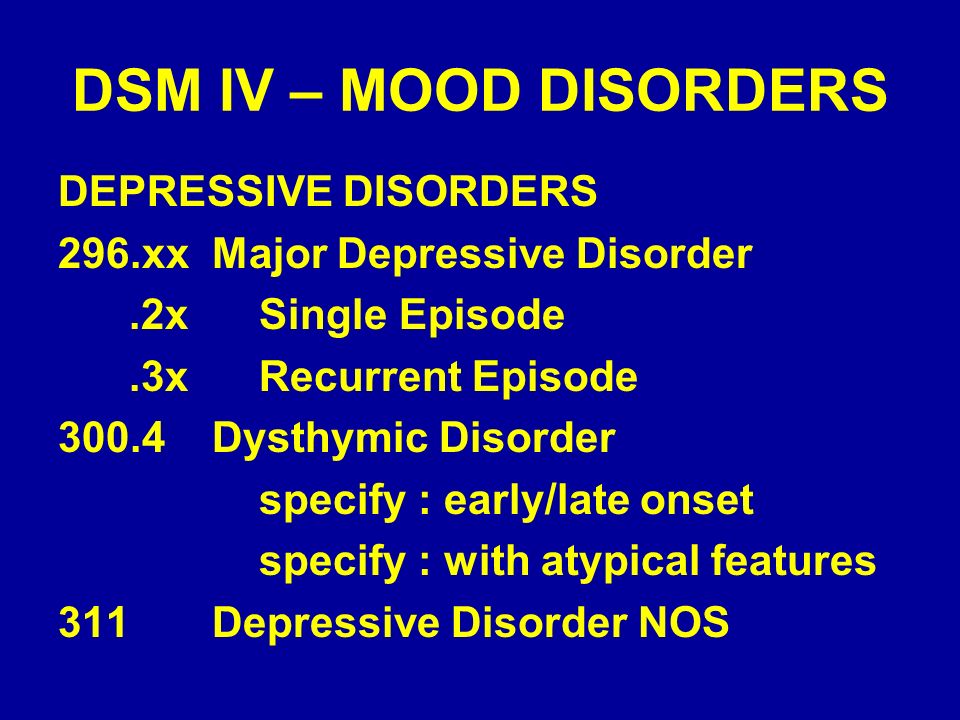

DSM-5 Criteria for Major Depressive Disorder

According to the DSM-5, the following criteria must be met for a diagnosis of major depression:

At least five of the following symptoms must have been present for at least two weeks and reflect a change in previous functionality. In addition, at least one of the symptoms is a low mood or loss of interest or pleasure.

In addition, at least one of the symptoms is a low mood or loss of interest or pleasure.

- The person is depressed most of the day, almost every day, as noted by himself or others.

- He or she is not interested in all or most activities most of the day, almost every day.

- Every day a person gains or loses a large amount of weight or has a decreased or increased appetite.

- Almost every day he or she suffers from insomnia or hypersomnia.

- Every day a person experiences psychomotor disturbances that are visible to others and can also be reported.

- Almost every day he or she feels exhausted or tired.

- Almost every day a person has thoughts of worthlessness or guilt.

- Every day a person's ability to think, concentrate, or make judgments deteriorates.

- He or she has recurrent suicidal thoughts, suicidal thoughts (without a definite plan), a suicide attempt, or a definite plan to commit suicide.

- Symptoms listed above cause clinical distress or interfere with daily activities.

- The episode of depression is not associated with the physiological effect of the drug or other disease.

- The onset of the episode is not better explained by specific or unspecified schizophrenia spectrum illness or other psychotic disorders.

- The person has never had a manic or hypomanic episode.

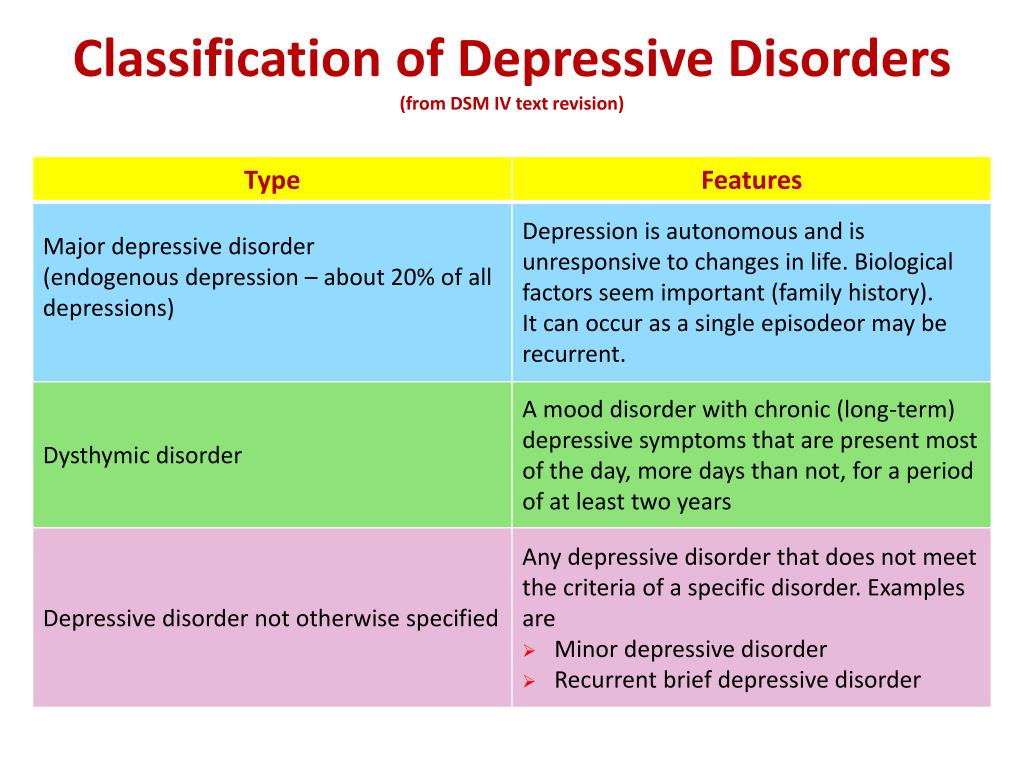

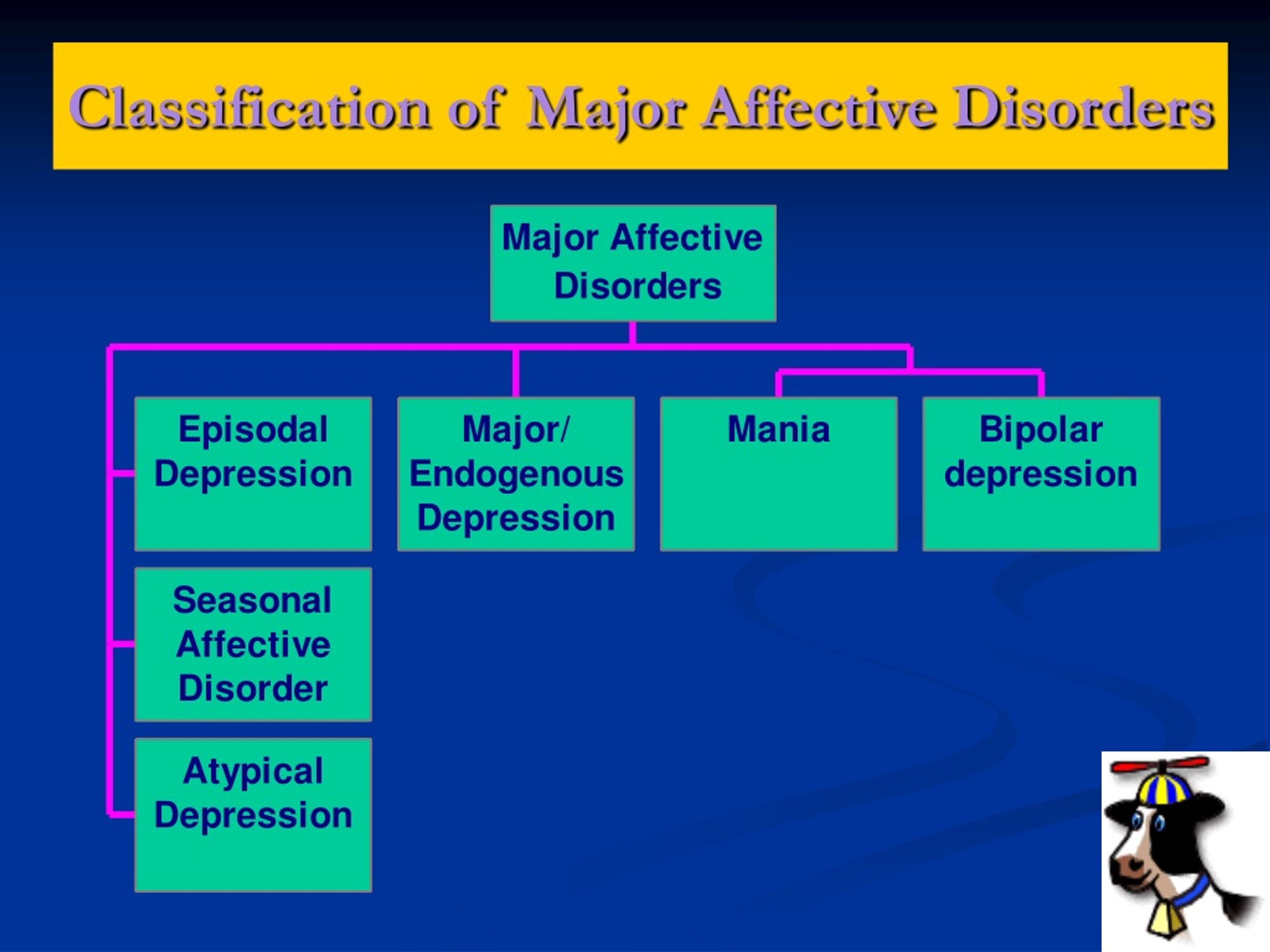

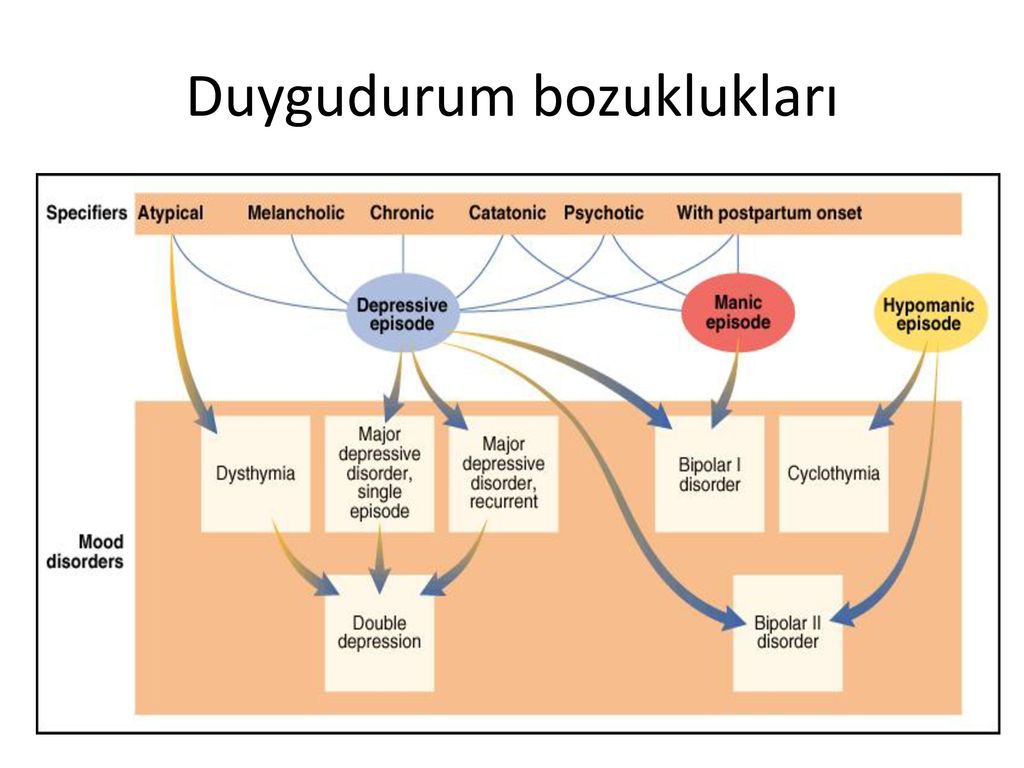

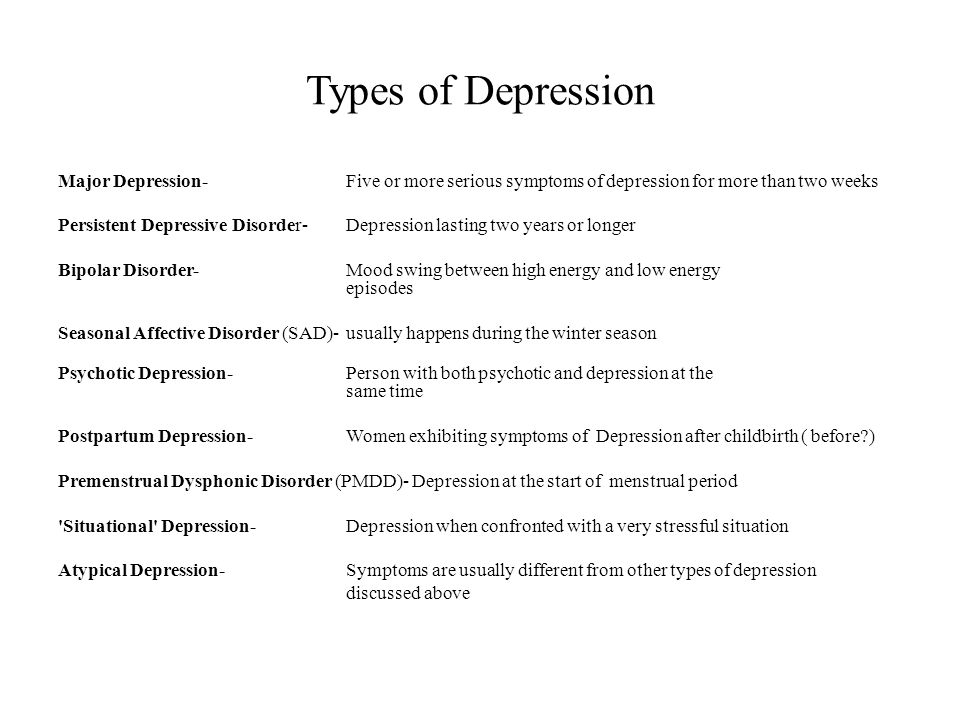

The diagnostic code for major depressive disorder is based on the frequency of recurrent episodes, the severity of the episodes, the presence of psychotic characteristics, and the state of remission. Below are the varieties of depression:

Severity of depression:

- Minor

- Moderate

- Heavy

- Psychotic

- In partial remission

- In complete remission

- Undefined

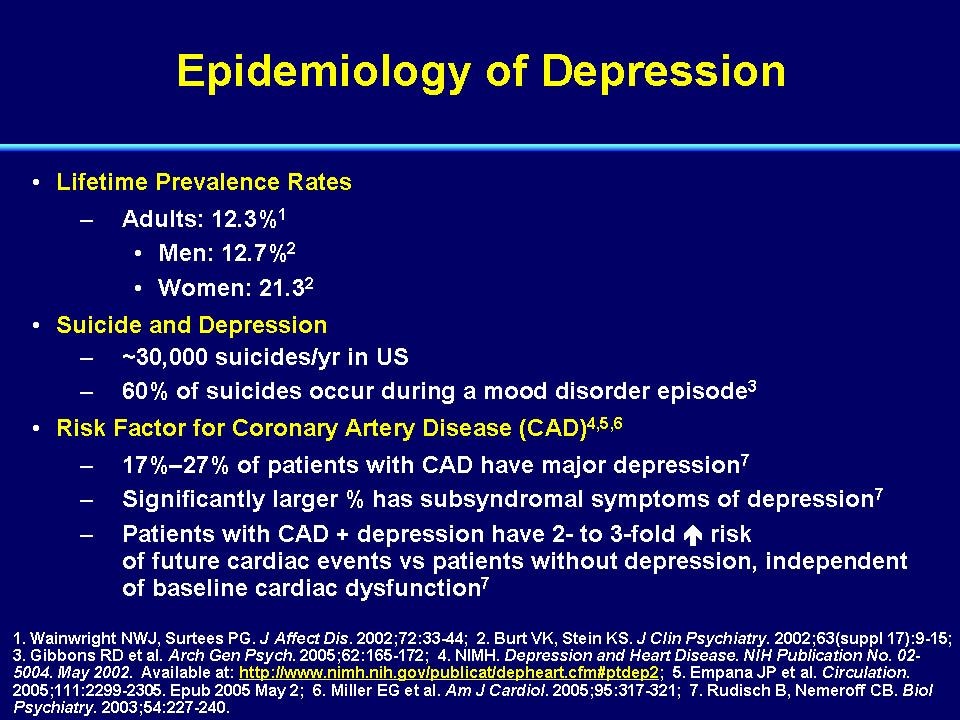

Epidemiology

Major depressive illness is a common mental illness. Its lifetime prevalence ranges from 5 to 17 percent. The incidence in women is about twice as high as in men. This is due to hormonal variations, the consequences of childbearing, different psychological pressures in men and women, and a behavioral model of learned helplessness. Although the median age of onset is around 40 years old, new studies show an increase in the incidence among younger populations due to the use of alcohol and other psychoactive substances.

The incidence in women is about twice as high as in men. This is due to hormonal variations, the consequences of childbearing, different psychological pressures in men and women, and a behavioral model of learned helplessness. Although the median age of onset is around 40 years old, new studies show an increase in the incidence among younger populations due to the use of alcohol and other psychoactive substances.

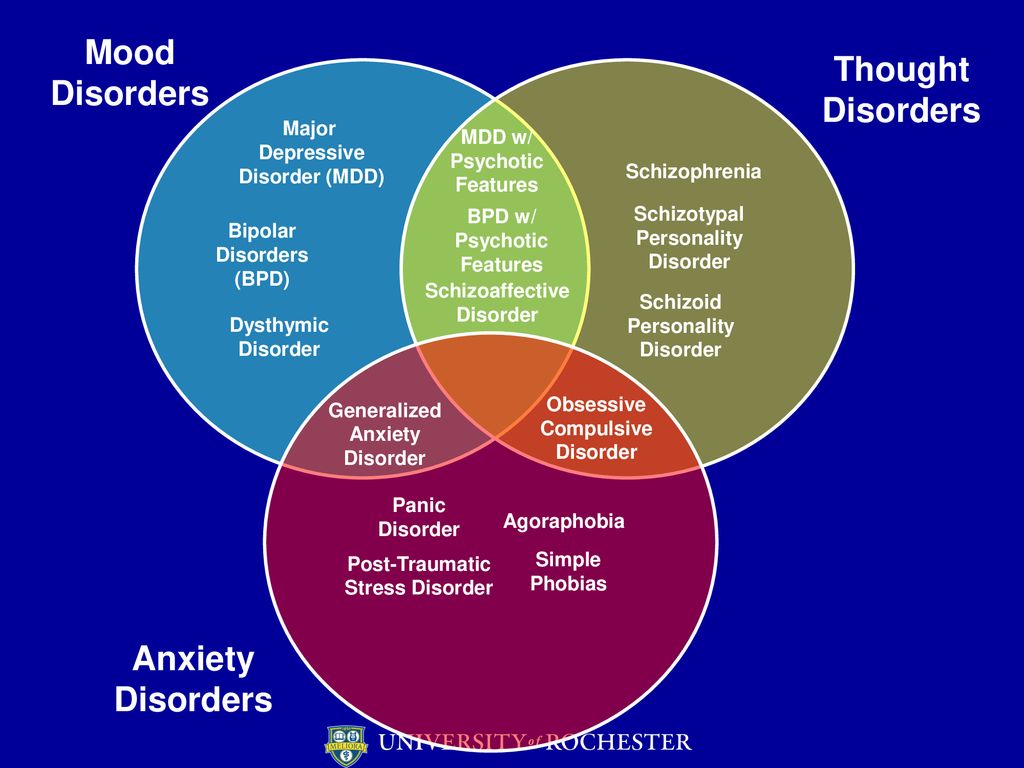

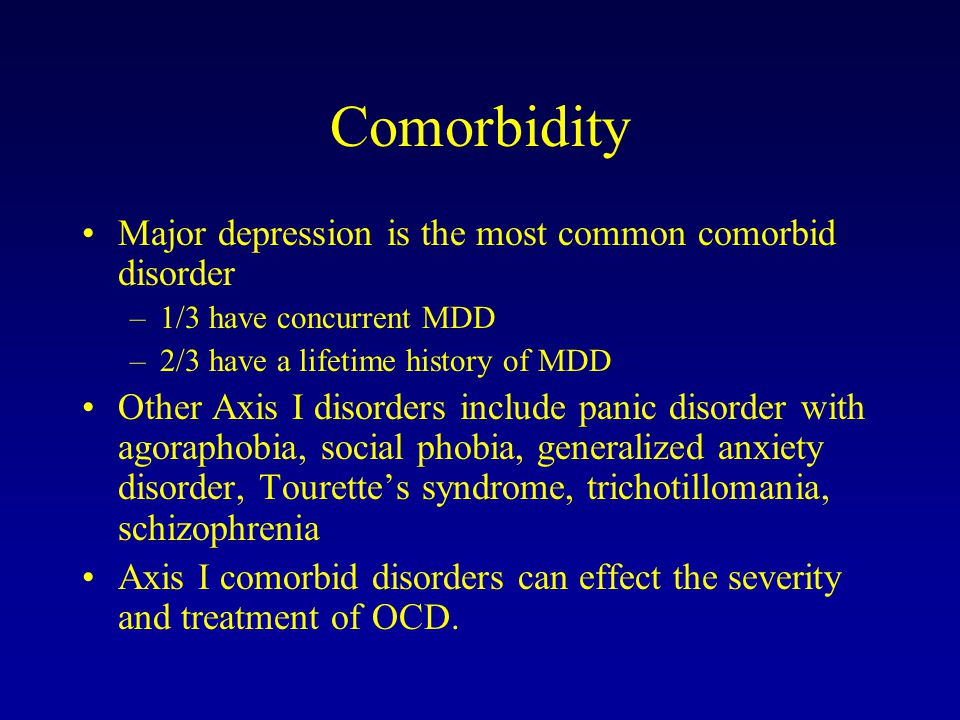

MDD is more common in divorced, separated, or bereaved individuals who do not have meaningful interpersonal interactions. There is no difference in the prevalence of MDD between races or socioeconomic status. People with MDD often have comorbidities such as substance abuse, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The presence of these comorbidities in people with MDD increases the risk of suicide. Depression is more common in older people with underlying medical problems. Depression is more common in rural areas than in cities.

Pathophysiology of major depressive disorder

The genesis of major depressive disorder is believed to be multifaceted, with biological, genetic, environmental and psychological factors at play. It used to be thought that MDD was caused mainly by abnormalities in neurotransmitters, especially serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine.

This has been demonstrated by the use of several antidepressants in the treatment of depression, such as selective serotonin receptor inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine receptor inhibitors, and dopamine-norepinephrine receptor inhibitors. Serotonin metabolites have been found to decrease in people who have had suicidal thoughts. However, recent hypotheses suggest that this is largely due to more complex neuroregulatory systems and brain circuits, leading to subsequent disruption of the neurotransmitter systems.

GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter, as well as glutamate and glycine, important excitatory neurotransmitters, have been shown to play a role in the genesis of depression. Depressed people have reduced plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, and brain levels of GABA. GABA is believed to act as an antidepressant by blocking the ascending monoamine pathways, including the mesocortical and mesolimbic systems.

Depressed people have reduced plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, and brain levels of GABA. GABA is believed to act as an antidepressant by blocking the ascending monoamine pathways, including the mesocortical and mesolimbic systems.

The antidepressant properties of drugs that oppose NMDA receptors have been investigated. Thyroid and growth hormone imbalances have also been linked to mood disorders. Numerous adversity and trauma in childhood have been linked to the development of depression later in life.

Severe early stress can cause dramatic changes in neuroendocrine and behavioral responses, leading to anatomical abnormalities in the cerebral cortex and severe depression later in life. Structural functional tomography of the brain in people with depression revealed greater hyperintensity in the subcortical regions and a decrease in the metabolism of the anterior brain regions on the left.

Family, adoption and twin studies have shown that genes play a role in the risk of depression. According to genetic studies, twins with MDD have a very high level of concordance, especially monozygotic twins. Life experience and personal qualities also have an impact.

According to genetic studies, twins with MDD have a very high level of concordance, especially monozygotic twins. Life experience and personal qualities also have an impact.

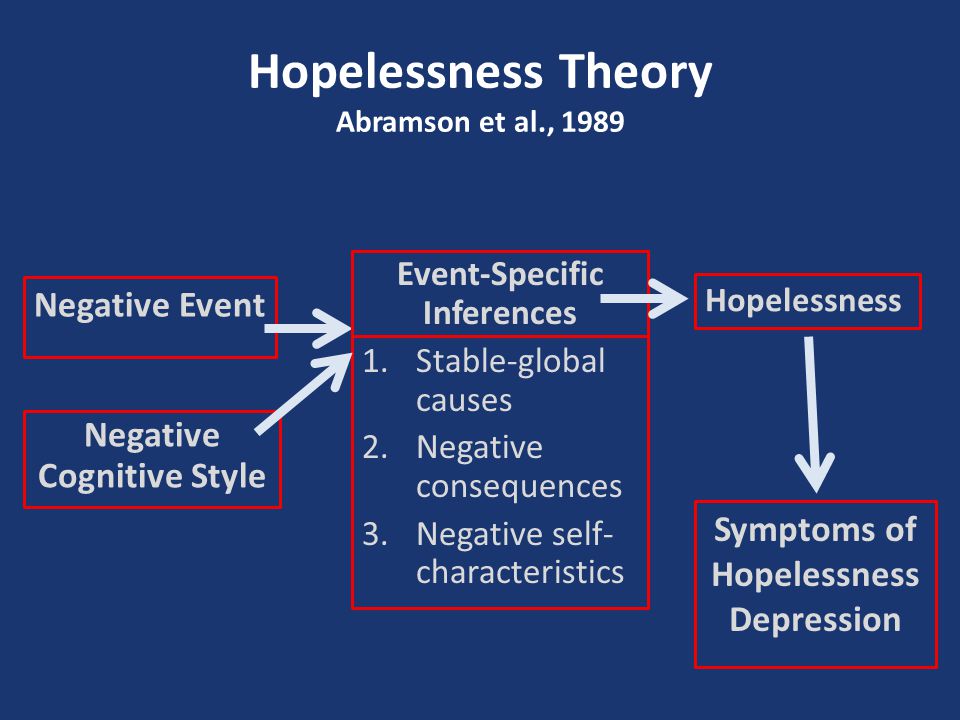

According to the theory of learned helplessness, the onset of depression is associated with the experience of uncontrollable events. Depression, according to cognitive theory, results from cognitive errors in those who are predisposed to depression.

Somatic illnesses associated with depression

Somatic sensations are especially common in depression and other mental illnesses. Although somatic symptoms are common in depressed individuals, they are of much lesser importance than major depressive symptoms in the diagnosis of depression.

The clinical stages of sad mood are characterized by both painful and non-painful bodily symptoms.

Major depressive disorder diagnosis

Major depressive disorder is a clinical diagnosis; this is mainly determined by the patient's medical history and assessment of mental status. Along with symptomatology, the clinical interview should include medical history, family history, social history, and history of drug use. Related information from the patient's family/friends is an important component of the psychiatric evaluation.

Along with symptomatology, the clinical interview should include medical history, family history, social history, and history of drug use. Related information from the patient's family/friends is an important component of the psychiatric evaluation.

Although there are no objective tests to diagnose depression, routine laboratory tests such as CBC with a differential diagnosis, a comprehensive metabolic panel, thyroid-stimulating hormone, free T4, vitamin D, urinalysis, and toxicology screening are done to rule out organic or medical diseases. causes of depression.

People with depression often see their primary care physicians for medical problems related to their depression rather than seeking a mental health professional. In nearly half of the cases, patients deny experiencing depressive symptoms and are often referred to therapy by family members or sent by employers to be tested for social isolation and decreased activity. At each visit, it is critical to assess the patient for thoughts of suicide or murder.

Being in a bad mood or feeling tense is common for all of us. When these feelings persist, you may suffer from depression or anxiety—or both. The self-assessment quizzes contain relevant questions to help you assess your current situation and develop a strategy to help you feel better sooner.

When you are going through a difficult moment, it is natural to feel depressed for a while; feelings like melancholy and loss help define who we are. However, if you feel sad or uncomfortable most of the time for an extended period of time, you may be suffering from depression.

Take a self-test to see if you are showing any warning signs of depression. This won't give you a diagnosis, but it will help you determine what to do next.

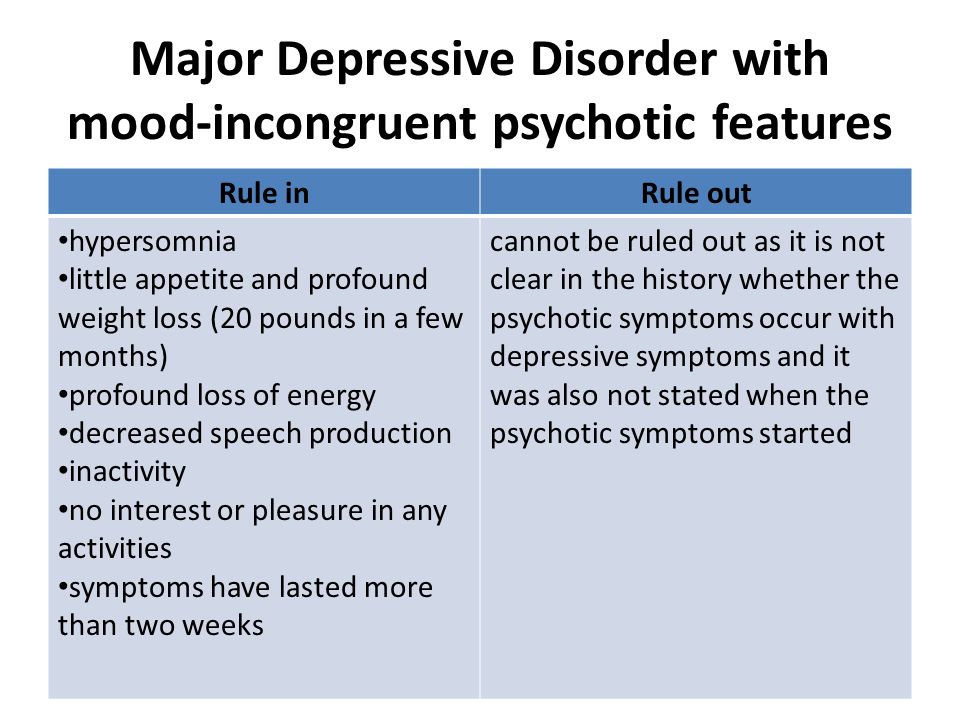

Major depressive disorder with psychotic features

Psychotic depression, also known as major depressive disorder with psychotic features, is a serious medical or mental illness that requires prompt treatment and constant monitoring by a physician or mental health professional.

Major depression is a common mental condition that can have a detrimental effect on many aspects of a person's life. It affects mood and behavior as well as various bodily processes such as eating and sleeping. People who are severely depressed often lose interest in things they used to love and have difficulty doing daily activities. Sometimes they may even feel that life is not worth living.

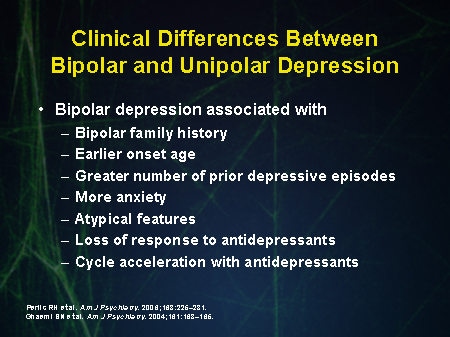

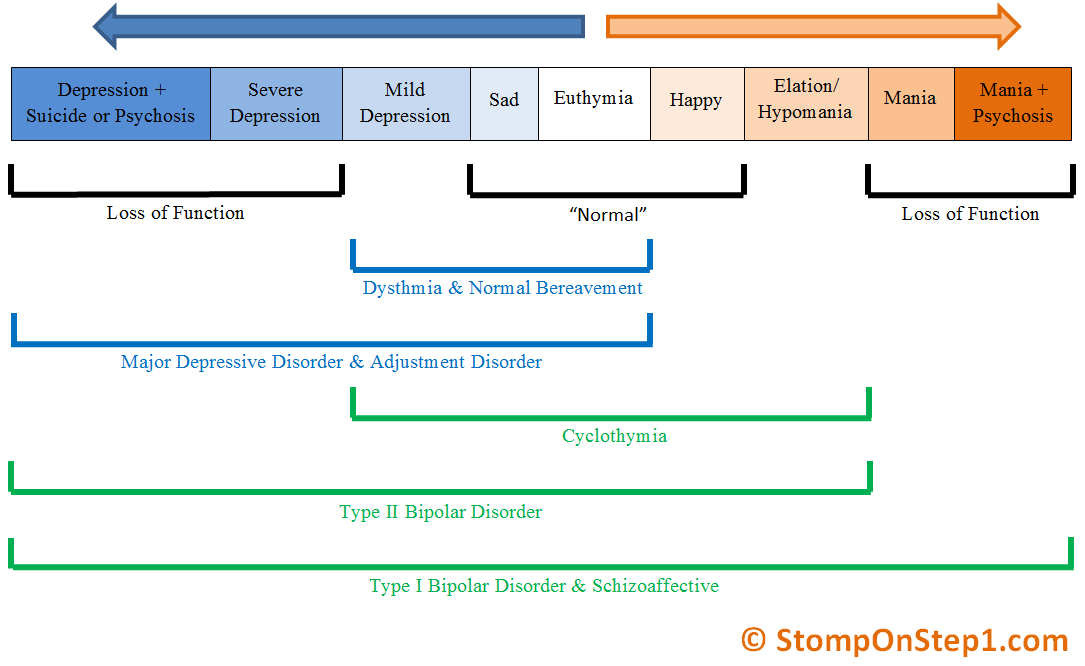

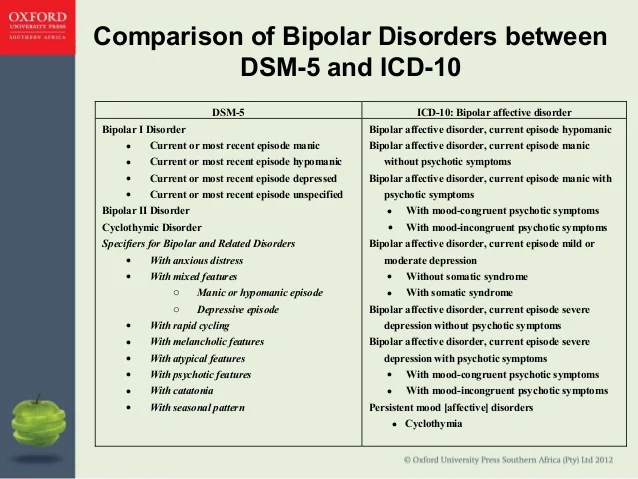

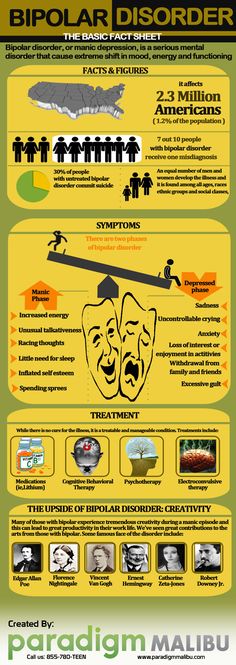

Bipolar disorder (BD)

Depression in patients with bipolar disorder (BD) is a significant clinical problem. Since schizophrenia dominates even in the treatment of BD, depression is associated not only with schizophrenia, but also with BD and comorbid medical disorders with a high risk of suicide.

Diagnosis of bipolar disorder (BD) and risk factors:

Approximately 12-17% of cases of bipolar disorder are not recognized until the mood "transforms" into hypomania or mania, either spontaneously or under the influence of substances uplifting mood.

Factors suggesting a diagnosis of BD:

- Family mania, psychosis, "nervous breakdown" or psychiatric hospitalization

- Early onset, often with depressive symptoms

- Cyclothymic mood

- Multiple relapses (eg 4 episodes of depression in 10 years)

- Depression with characteristic agitation, anger, insomnia, irritability, talkativeness.

- Other features are "mixed" or hypomanic or psychotic symptoms.

- Clinically "worsens", especially with mixed properties, during antidepressant treatment.

- Suicidal thoughts and actions

- Alcohol or drug abuse

Major depressive disorder in children and adolescents:

Major depressive disorder (MDD) can have a significant impact onset during childhood and adolescence. Associated with this are poor school performance, interpersonal problems later in life, early parenthood, and an increased risk of other psychiatric and substance use disorders. Diagnosing MDD in childhood is difficult. Children with MDD are often underdiagnosed and undertreated, and only 50% of adolescents are diagnosed before reaching adulthood.

Diagnosing MDD in childhood is difficult. Children with MDD are often underdiagnosed and undertreated, and only 50% of adolescents are diagnosed before reaching adulthood.

Symptoms of depression in children aged 3-8 years include:

- unsubstantiated claims.

- irritability

- less signs of depression

- anxiety

- behavioral changes

As the child becomes a teenager and adult, the presentation of symptoms meets the criteria for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5):

- Irritability.

- Expected weight gain.

- Lethargy or inner restlessness.

- May be delusional and not limited to feelings of guilt.

Postpartum depression

Postpartum depression affects one in seven women (PPD). While most women recover quickly from childhood blues, PPD lasts much longer and has a significant impact on women's ability to return to normal activities.

PDD affects the mother and her relationship with the child. PRD impairs maternal brain response and behavior. Postpartum depression most often occurs within 6 weeks after delivery. PDD affects 6.5 to 20% of women. It is more common in teenage girls, mothers who have given birth prematurely, and women living in cities.

In one study, African American and Hispanic mothers reported onset of symptoms within 2 weeks of birth, while white mothers reported onset of symptoms later.

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

Premenstrual symptoms are a group of psychological, behavioral and physical symptoms that cyclically occur before menstruation and subsequently resolve after menstruation in women of reproductive age. Most women experience relatively mild pain and the symptoms do not interfere with their personal, social, or professional lives; however, 5% to 8% of women experience moderate or severe symptoms that can cause significant distress and functional impairment.

All women of reproductive age, from menarche to menopause, may have premenstrual symptoms. Premenstrual symptoms are a common problem for women of reproductive age. In the United States, 70 to 90 percent of women of reproductive age report at least some premenstrual pain.

Approximately one third of these women have symptoms severe enough to warrant a diagnosis of PMS. PMDD, the most severe type of premenstrual symptom complex, occurs in 3-8% of these women.

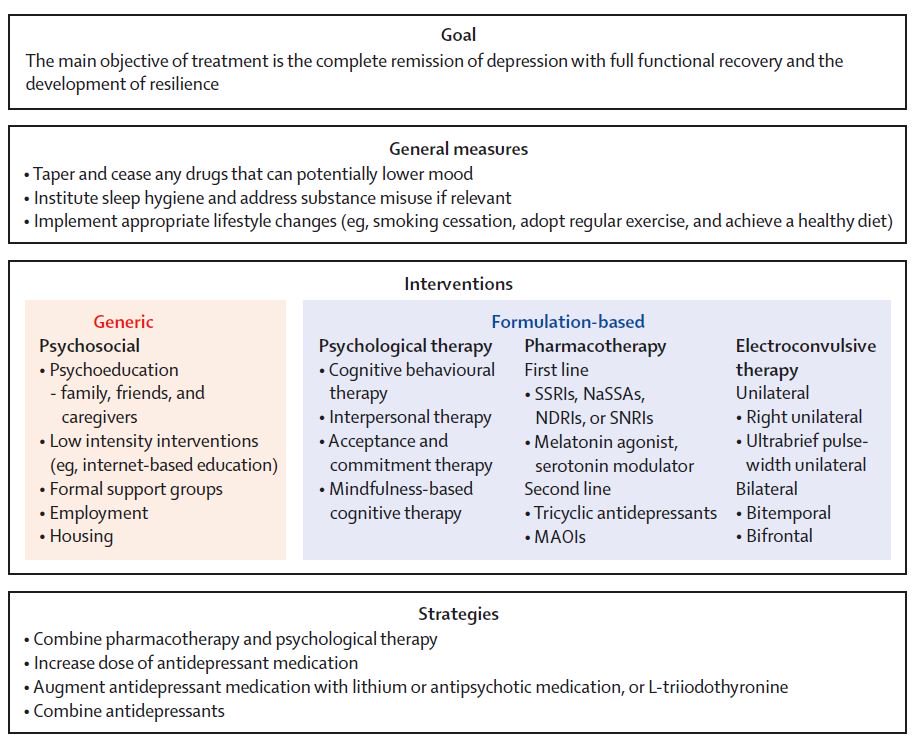

Treatment of major depressive disorder

Treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) in adults:

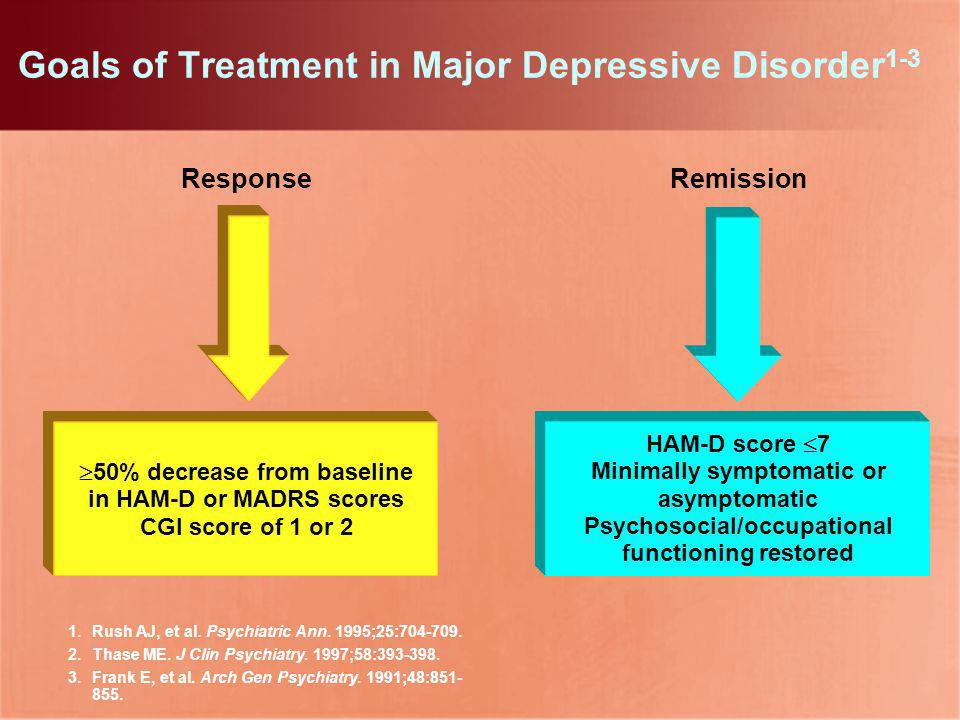

Treatment options for major depressive disorder include medication, psychological, interventional, and lifestyle changes. Medications and/or psychotherapy are used initially to treat MDD.

Combination treatment, including both drugs and psychotherapy, has been shown to be more effective than either treatment alone. Electroconvulsive therapy has been shown to be more effective than any other treatment for severe major depression.

Patient psychotherapy:

Depression education and treatment can be provided to all patients. When appropriate, education may be provided to eligible family members.

Information about available treatment options will help patients make informed decisions, anticipate side effects, and follow prescribed treatment. Another important aspect of education was informing patients and concerned family members about the delayed duration of antidepressant onset of action.

Pharmacotherapy and acute treatment:

Antidepressants may be used as the primary treatment for patients with moderate or severe depression.

Clinical features that may indicate that the drug is a preferred therapeutic agent include a history of previous positive response to antidepressants, severity of symptoms, significant sleep disturbance and appetite disturbance.

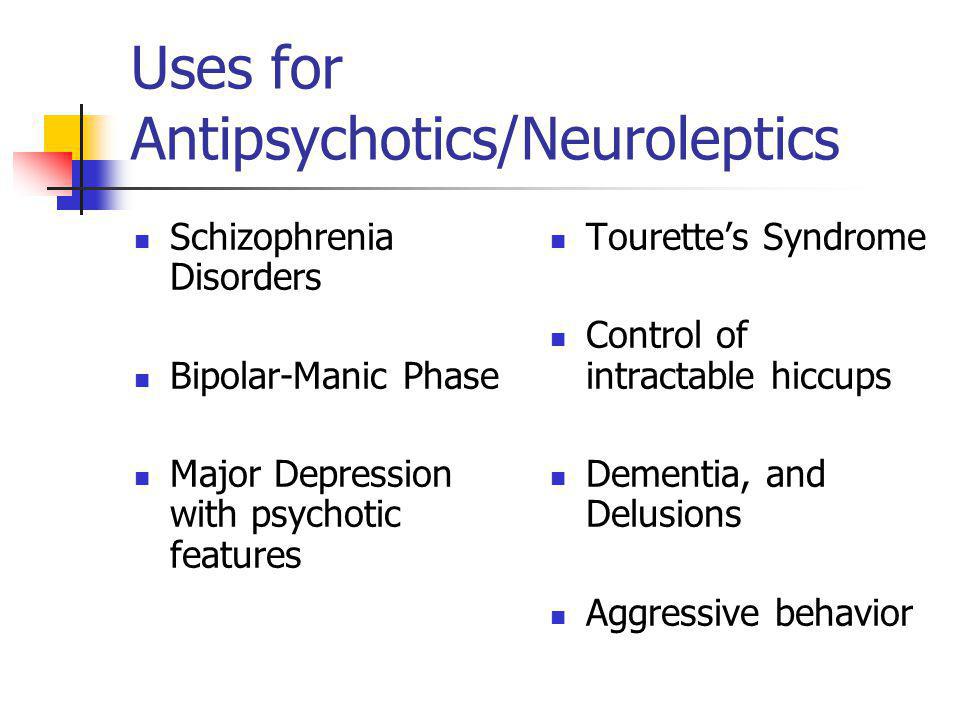

Patients with severe depression with psychotic features will require antidepressant and antipsychotic and/or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

All antidepressants are effective, although their side effects vary. The following drugs have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of MDD:

- Fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine are examples of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). They are commonly used as first line therapy and are the most commonly prescribed antidepressants.

- Venlafaxine, duloxetine, desvenlafaxine, levomilnacipran and milnacipran are examples of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). They are often used to treat depressed people who also have pain problems.

- Trazodone, vilazodone and vortioxetine are serotonin modulators.

- Bupropion and mirtazapine are examples of atypical antidepressants. When patients experience sexual side effects from SSRIs or SNRIs, they are often recommended as monotherapy or as adjunctive drugs.

- Amitriptyline, imipramine, clomipramine, doxepin, nortriptyline and desipramine are tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs).

- Tranylcypromine, phenelzine, selegiline, and isocarboxazid are examples of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). Due to the high prevalence of side effects and death in overdose, MAOIs and TCAs are not commonly used.

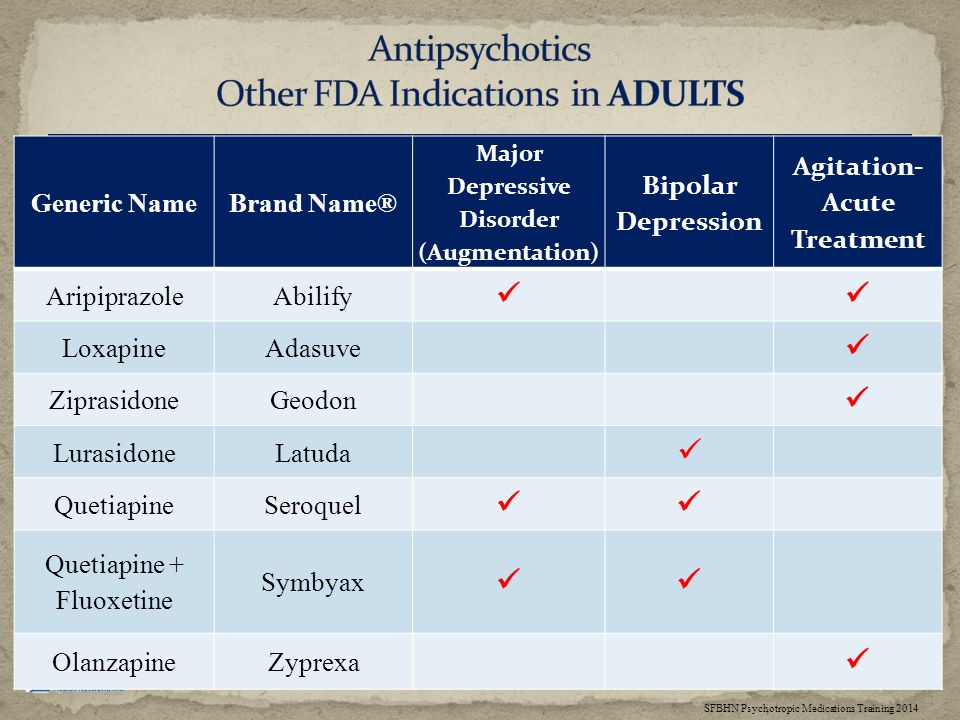

- Other drugs that can be used to improve the effectiveness of antidepressants include mood stabilizers and antipsychotics.

The role of yoga and meditation in managing depression:

Originating in ancient India, yoga is recognized as a form of alternative medicine using mind-body practice. Yoga philosophy is based on 8 elements that are best described as the ethical principles of a meaningful and purposeful life. Yoga can help with depression through the following mechanisms:

- Muscle relaxation resulting in less pain

- Creating Balanced Energy

- Decreased breathing and heart rate

- Lowering blood pressure and cortisol levels

- Increase blood flow

- Reducing stress and anxiety through tranquility

- Improve pre-existing ailments such as arthritis, cancer, mental illness and more.

Treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) in children and adolescents

Psychotherapy is important for both patients and their families, so everyone knows about the plan and goals of treatment. When the patient receives information, the severity of symptoms decreases. Mental education may include knowledge about the signs and symptoms of depression, the clinical course of the illness, the risk of exacerbation, treatment options, and parental advice on how to interact with depressed young people.

According to research by Sandra Mullen, psychotherapy, along with medication, is often recommended for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) in children and adolescents diagnosed with depression, suicidal ideation, and transient hypomania/mania.

Treatment of bipolar depression

Bipolar depression remains a clinical problem. Treatment options are limited, especially in the treatment of the acute phase of bipolar depression. There are currently only three approved drugs: OFC, quetiapine (immediate or extended release) and lurasidone (lithium monotherapy or adjuvant therapy or valproate). All three agents have similar efficacy profiles. They differ in duration.

There are currently only three approved drugs: OFC, quetiapine (immediate or extended release) and lurasidone (lithium monotherapy or adjuvant therapy or valproate). All three agents have similar efficacy profiles. They differ in duration.

Non-approved agents and treatments

Non-pharmacological drugs such as lamotrigine, antidepressants, modafinil, pramipexole, ketamine, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) are often prescribed for the treatment of acute bipolar depression.

Treatment of recurrent depression:

Some patients may experience recurrent episodes of depression throughout their lives unless supportive care is used to prevent relapse. Treatment should include psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy, and the dose should generally not be reduced after remission has been achieved.

Differential

Critical to rule out depressive disorder due to another medical condition, depressive disorder due to psychoactive substances/drugs, dysthymia, cyclothymia, bereavement, adjustment disorder with depressed mood, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety disorders and eating disorders when assessed for DMD. Depressive symptoms can develop as a result of the following factors:

Depressive symptoms can develop as a result of the following factors:

- Neurological causes such as cerebrovascular accident, multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease.

- Endocrine diseases such as diabetes, thyroid disease and adrenal disease.

- Metabolic disorders such as hypercalcemia, hyponatremia

- Drugs/substances causing dependence: steroids, antihypertensives, anticonvulsants, antibiotics, sedatives, sleeping pills, alcohol, stimulant withdrawal.

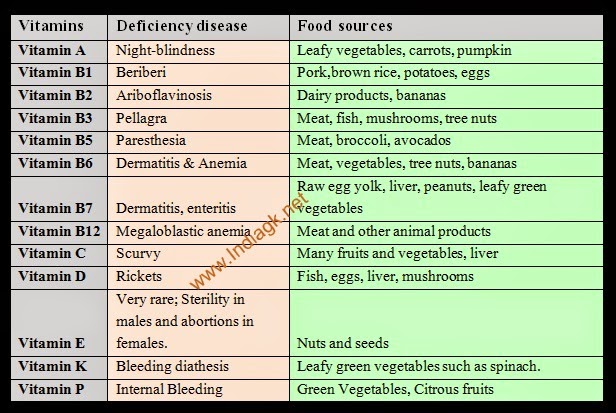

- Nutrient deficiencies such as vitamin D, B12, B6, iron or folate deficiency

- Infectious diseases such as HIV and syphilis

- Malignant neoplasms

Prognosis

Episodes of depression in untreated major depressive disorder can last 6 to 12 months. Approximately two-thirds of people with MDD think about suicide, and 10 to 15% commit suicide. MDD is a chronic relapsing disease; the recurrence rate after the first episode is about 50%, 70% after the second episode and 90% after the third episode. Approximately 5-10% of people with MDD develop bipolar disorder.

Approximately 5-10% of people with MDD develop bipolar disorder.

Patients with mild episodes, no psychotic symptoms, improved adherence, a reliable support system, and adequate premorbid functioning have a positive prognosis for MDD. In the presence of a concomitant mental disorder, personality disorder, multiple hospitalizations and advanced age, the prognosis is poor.

Complications

MDD is one of the leading causes of disability in the world. This not only causes severe functional impairment, but also negatively affects interpersonal relationships, reducing the quality of life. Individuals with MDD are at significant risk of developing comorbid anxiety and drug use disorders, which increase the risk of suicide.

Diabetes, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and coronary heart disease may be aggravated by depression. People who are depressed are more likely to engage in self-destructive behavior as a coping method. Left untreated, MDD can be quite debilitating.

Findings

In 2008, WHO classified major depressive disorder (MDD) as the third leading cause of disease burden worldwide and is expected to be number one by 2030.

Diagnosis is made when a person has a persistently low or depressed mood, anhedonia (loss of interest in pleasure), feelings of guilt or worthlessness, lack of energy, poor concentration, changes in appetite, psychomotor retardation or agitation, trouble sleeping, or suicidal thoughts.

Effective and successful treatment of MDD requires a multidisciplinary approach. These collaborative services include primary care physicians and psychiatrists, as well as nurses, therapists, social workers and caregivers. Screening for depression in primary care settings is critical.

Clinical typology of atypical depression in bipolar and unipolar affective disorder

In the domestic literature, the concept of atypical depression does not have clear diagnostic boundaries, and understanding the atypicality of the clinical picture of depression most often reflects the presence of symptoms (somatovegetative, obsessive, etc. ) that are not characteristic of manifestations of the classical melancholic affect [4, 6, 8, 9]. At the same time, in foreign publications, this term has its own syndromological meaning in the structure of a major depressive episode (DSM-IV). The origins of the term "atypical depression" are the English psychopathologists E. West and P. Dally [43], who, in their work on the study of the effectiveness of the drug from the group of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) - ipronioside, singled out a group of patients with a hysterical personality type, secondary depression and anxiety. The result of a systematic study of this disorder by J. Rabkin et al. [34] atypical depression at 1994 was included in the DSM-IV as a specifier for major depressive episode. Despite the high prevalence of atypical depression, reaching 15.3–29% [7, 10, 15–18, 38], at present there is no common idea about its place in the structure of affective pathology. Some authors [14, 24, 40] single out atypical depression as an independent nosological unit, confirming their findings with the biological features of its pathogenesis, while others [11] consider this condition as a “transitional” syndrome, a kind of bridge from unipolar depression to bipolar II disorder.

) that are not characteristic of manifestations of the classical melancholic affect [4, 6, 8, 9]. At the same time, in foreign publications, this term has its own syndromological meaning in the structure of a major depressive episode (DSM-IV). The origins of the term "atypical depression" are the English psychopathologists E. West and P. Dally [43], who, in their work on the study of the effectiveness of the drug from the group of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) - ipronioside, singled out a group of patients with a hysterical personality type, secondary depression and anxiety. The result of a systematic study of this disorder by J. Rabkin et al. [34] atypical depression at 1994 was included in the DSM-IV as a specifier for major depressive episode. Despite the high prevalence of atypical depression, reaching 15.3–29% [7, 10, 15–18, 38], at present there is no common idea about its place in the structure of affective pathology. Some authors [14, 24, 40] single out atypical depression as an independent nosological unit, confirming their findings with the biological features of its pathogenesis, while others [11] consider this condition as a “transitional” syndrome, a kind of bridge from unipolar depression to bipolar II disorder. type, and still others [15, 28, 32, 42] consider atypical depression to be a syndrome that develops according to compensatory mechanisms in response to stress factors. This is largely due to the heterogeneity of the results of works directly devoted to the analysis of the clinical features of conditions in the structure of which either an inversion of vegetative symptoms, or reactive lability, or sensitivity to rejection is singled out as an obligate trait.

type, and still others [15, 28, 32, 42] consider atypical depression to be a syndrome that develops according to compensatory mechanisms in response to stress factors. This is largely due to the heterogeneity of the results of works directly devoted to the analysis of the clinical features of conditions in the structure of which either an inversion of vegetative symptoms, or reactive lability, or sensitivity to rejection is singled out as an obligate trait.

The purpose of this work is to study the clinical features of atypical symptoms in the structure of a depressive episode and to determine their role in the formation of a stereotype of the course of an affective disorder.

Material and methods

The study was conducted in the department of new means and methods of therapy of the Department of Borderline Psychiatry of the State Scientific Center for Social and Forensic Psychiatry. V.P. Serbsky on the basis of the Moscow Psychiatric Clinical Hospital No. 12.

12.

The sample consisted of 46 people aged 18 to 65 years with a diagnosis of atypical depression in the structure of a major depressive episode (according to DSM-IV). Of the surveyed, the majority (87%) were women. The mean age of the patients was 37.6±13.5 years. An analysis of the educational level of the study group showed a predominance (47.8%) of people with higher education; a significant part were people with incomplete higher (26%) and secondary specialized (19.5%) education; the percentage of those surveyed who received only primary education was 6.5. Evaluation of labor activity showed that 45.6% of patients had a permanent job and a stable income, 54.3% did not work, of which 26% were due to mental illness.

The criterion for inclusion of patients in the study was the compliance of their mental state with the criteria for atypical depression according to the DSM-IV classification: the mandatory presence in the clinical picture of criterion A (mood reactivity) and two of the four criteria B (hypersomnia, hyperphagia, lead paralysis, sensitivity to rejection). Patients with acute and chronic somatic diseases in the stage of decompensation, severe neurological pathology, organic pathology of the brain, epilepsy, schizophrenia and delusional disorders, as well as those who abuse psychoactive substances were excluded from the study.

Patients with acute and chronic somatic diseases in the stage of decompensation, severe neurological pathology, organic pathology of the brain, epilepsy, schizophrenia and delusional disorders, as well as those who abuse psychoactive substances were excluded from the study.

In the course of the study, psychopathological and psychometric research methods were used, including the 17-item Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD-17), the Atypical Depression Scale (ADDS), and the Mini-Mult scale (abbreviated version of MMPI) was used to assess personal characteristics.

Results and discussion

Clinical assessment of the patients' condition revealed psychopathological heterogeneity of atypical depression, which made it possible to identify three of its variants: with a predominance of 1) mood reactivity; 2) inverted vegetative symptoms (hyperphagia, hypersomnia), including "lead paralysis"; 3) sensitivity to rejection.

The variant of atypical depression with a predominance of mood reactivity occurred in 30. 4% of patients, mainly in women (92.3%). Their mean age was 42.3±12.6 years. Patients in this group were characterized by a predominance (61.5%) of people with higher and incomplete higher education. Persons with a permanent job and a stable income amounted to 38.4%, the unemployed were 61.5%, of which 37.5% were mentally ill.

4% of patients, mainly in women (92.3%). Their mean age was 42.3±12.6 years. Patients in this group were characterized by a predominance (61.5%) of people with higher and incomplete higher education. Persons with a permanent job and a stable income amounted to 38.4%, the unemployed were 61.5%, of which 37.5% were mentally ill.

At the forefront in the clinical picture of the state of such patients was mood reactivity, i. the ability to improve it in response to current or potentially positive life events [35, 39, 42]. Such a willingness of emotional reactions to change (increase) mood in response to events or situations that are positive for patients was observed with general complaints of anhedonia, apathy, and other symptoms of a depressive state [41]. Patients with a predominance of mood reactivity at the mention of their relatives or friends, memories, for example, about a recent vacation or visiting the theater, were significantly animated, their facial expressions and movements became expressive, their mood improved. By their face one could easily guess the attitude to an object, event or person. At the same time, completely different factors were subjectively significant and positive, raising the mood of patients. Some noted that “only at the wheel they feel like a fish in water”, or “escaping depression, they go headlong into work”; for others, potentially significant events were thoughts about a future vacation - “only thinking about it lifts my spirits”, “during periods of strong apathy, I begin to plan it in great detail, and then longing recedes for a while”; the third was pleased with the thought of the planned purchases - “instead of work, I again look through the ads for the sale of apartments, although I know them by heart”; for the fourth, a simple compliment or encouragement from loved ones or a doctor was a positive event. Such positive events were long-awaited for them, and they often “mentally urged time” in impatience to distract themselves from “piling up problems”. The ability of patients to respond to subjectively significant positive life situations differed in the degree of reversibility of hypothymia, manifesting itself in an improvement in mood - from an insignificant level to its complete normalization [19].

By their face one could easily guess the attitude to an object, event or person. At the same time, completely different factors were subjectively significant and positive, raising the mood of patients. Some noted that “only at the wheel they feel like a fish in water”, or “escaping depression, they go headlong into work”; for others, potentially significant events were thoughts about a future vacation - “only thinking about it lifts my spirits”, “during periods of strong apathy, I begin to plan it in great detail, and then longing recedes for a while”; the third was pleased with the thought of the planned purchases - “instead of work, I again look through the ads for the sale of apartments, although I know them by heart”; for the fourth, a simple compliment or encouragement from loved ones or a doctor was a positive event. Such positive events were long-awaited for them, and they often “mentally urged time” in impatience to distract themselves from “piling up problems”. The ability of patients to respond to subjectively significant positive life situations differed in the degree of reversibility of hypothymia, manifesting itself in an improvement in mood - from an insignificant level to its complete normalization [19]. Thus, one patient noted that “going to the store, even during a recession, is always associated with a positive”, while another indicated that during a period of depression she likes to meet her friends, although “feelings are no longer the same.” Some patients were characterized by long periods of normothymia under a favorable set of circumstances [5, 17], while others noted long periods of depressed mood with short-term “enlightenments” in response to positive, emotionally significant events in their lives [37].

Thus, one patient noted that “going to the store, even during a recession, is always associated with a positive”, while another indicated that during a period of depression she likes to meet her friends, although “feelings are no longer the same.” Some patients were characterized by long periods of normothymia under a favorable set of circumstances [5, 17], while others noted long periods of depressed mood with short-term “enlightenments” in response to positive, emotionally significant events in their lives [37].

Among other atypical symptoms, patients of this group were characterized by complaints of a feeling of heaviness, fatigue throughout the body, including in the limbs (53.8%), as well as increased sensitivity to rejection (46.1%), characteristic of them with childhood and not increasing in the current state. At the same time, other symptoms of atypical depression, such as hyperphagia and hypersomnia, were minimally expressed (23%, respectively).

The severity of the current depressive episode according to the HAMD scale was 20±3 points. The personality profile of patients with mood reactivity was characterized by pronounced psychasthenic, schizoid and hysterical features with minimal manifestations of hyperthymic and paranoid features. Using the ADDS scale, a spectrum of atypical symptoms was identified, the most characteristic of the described variant of atypical depression. It is shown in fig. 1

The personality profile of patients with mood reactivity was characterized by pronounced psychasthenic, schizoid and hysterical features with minimal manifestations of hyperthymic and paranoid features. Using the ADDS scale, a spectrum of atypical symptoms was identified, the most characteristic of the described variant of atypical depression. It is shown in fig. 1

| Fig. 1. Spectrum of atypical symptoms in depression with a predominance of mood reactivity according to the ADDS scale (points). |

The variant of atypical depression with a predominance of inverse autonomic symptoms was the most numerous (39.1%). The mean age of patients in this group was 30.1±9.4 years. This group, like the previous one, was characterized by the predominance of women (73%) and persons with higher and incomplete higher education (83.3%). However, there were more patients with a permanent job - 55. 5% (unemployed 44.4%, of which 28.5% - due to the current mental disorder).

5% (unemployed 44.4%, of which 28.5% - due to the current mental disorder).

The psychopathological picture of this variant of atypical depression was primarily determined by the symptoms of hypersomnia, hyperphagia and lead paralysis. The high correlation between these symptoms, noted by many authors [10, 13, 25, 26], was the basis for the reconstruction of the diagnostic criteria for atypical depression proposed by F. Benazzi [12], according to which the presence of only two symptoms (overeating and drowsiness) is sufficient to make an appropriate diagnosis.

A symptom observed in almost all patients (89%) of this group was hypersomnia, which was manifested either by increased daytime sleepiness, or sleep attacks (which were not explained by insufficient sleep during the night), or a prolonged transition to a state of full wakefulness after awakening [19]. The total number of hours of sleep per day in patients with hypersomnia ranged from 10 to 16. Most often (61%), hypersomnia was manifested by a feeling of daytime sleepiness of varying severity, in which patients several times during the day could “lie down for several hours” or, with more pronounced drowsiness, fell asleep wherever possible - "I sleep at home, in the subway, at the institute. " Less frequently (28%), it was manifested by a prolonged transition to full wakefulness after awakening. In such patients, despite the significantly higher than normal sleep duration, there was a lack of a sense of rest after waking up, it was difficult for them to wake up, force themselves to get out of bed - “in the evening I fall into a deep sleep without waking up, but in the morning I didn’t seem to sleep.” Sometimes (11%) manifestations of hypersomnia resembled the clinical picture of the Kleine-Levin syndrome [27] and were so pronounced that patients described these conditions with the words “hibernation”, “I sleep like a bear and don’t want to wake up”, “I wake up for short periods of time and again I fall asleep." Periods of such "hibernation" lasting several days could be repeated, alternating with minor phenomena of daytime sleepiness.

" Less frequently (28%), it was manifested by a prolonged transition to full wakefulness after awakening. In such patients, despite the significantly higher than normal sleep duration, there was a lack of a sense of rest after waking up, it was difficult for them to wake up, force themselves to get out of bed - “in the evening I fall into a deep sleep without waking up, but in the morning I didn’t seem to sleep.” Sometimes (11%) manifestations of hypersomnia resembled the clinical picture of the Kleine-Levin syndrome [27] and were so pronounced that patients described these conditions with the words “hibernation”, “I sleep like a bear and don’t want to wake up”, “I wake up for short periods of time and again I fall asleep." Periods of such "hibernation" lasting several days could be repeated, alternating with minor phenomena of daytime sleepiness.

Hypersomnia in 78% of cases was accompanied by another symptom characteristic of this variant of atypical depression — hyperphagia [7, 10]. Patients complained of increased appetite, their behavior could manifest itself both in the frequent use of small amounts of food “I chew something all the time”, and in episodes with the simultaneous intake of large amounts of food - “dinner turns into a feast”. Some patients were characterized by an increased craving for food rich in carbohydrates (“carbohydrate thirst”): flour and confectionery products, in particular chocolate [5, 29, 31]. Often, patients did not see a problem in increased appetite, believing that they successfully compensate for the calories received, for example, by physical activity. In other cases, increased appetite and “craving for food” were masked by the internal prohibitions of the patients themselves, who refused to eat by willpower, “I want to chew something all the time, but I don’t let myself relax.” Sometimes, according to patients, the tendency to hyperphagia was a way of coping with stressful life situations that was characteristic of them since childhood [32] — “when I worry, I definitely need to eat something tasty”, and with depression it only intensified — “wolf appetite wakes up ".

Patients complained of increased appetite, their behavior could manifest itself both in the frequent use of small amounts of food “I chew something all the time”, and in episodes with the simultaneous intake of large amounts of food - “dinner turns into a feast”. Some patients were characterized by an increased craving for food rich in carbohydrates (“carbohydrate thirst”): flour and confectionery products, in particular chocolate [5, 29, 31]. Often, patients did not see a problem in increased appetite, believing that they successfully compensate for the calories received, for example, by physical activity. In other cases, increased appetite and “craving for food” were masked by the internal prohibitions of the patients themselves, who refused to eat by willpower, “I want to chew something all the time, but I don’t let myself relax.” Sometimes, according to patients, the tendency to hyperphagia was a way of coping with stressful life situations that was characteristic of them since childhood [32] — “when I worry, I definitely need to eat something tasty”, and with depression it only intensified — “wolf appetite wakes up ". In a number of patients, an increase in appetite reached the degree of an unbridled desire to absorb food, which corresponded to the clinical picture of eating disorders in compulsive bulimia nervosa [36]. At the same time, the patients did not feel the taste of food and did not think about its quantity - "I eat everything that comes to hand", "I open the refrigerator and want to eat everything at the same time." Highlighting the craving for overeating as a symptom reflecting the common pathogenetic mechanisms of atypical depression and bulimia nervosa, J. Wildes and M. Marcus [44] classify both syndromes as “mild bipolar spectrum” disorders [32]. Patients who complained of hyperphagia often (78%) reported weight gain of 3-6 kg; in 22% of patients, the gained weight reached significant values, increasing by 7-12 kg within a few months.

In a number of patients, an increase in appetite reached the degree of an unbridled desire to absorb food, which corresponded to the clinical picture of eating disorders in compulsive bulimia nervosa [36]. At the same time, the patients did not feel the taste of food and did not think about its quantity - "I eat everything that comes to hand", "I open the refrigerator and want to eat everything at the same time." Highlighting the craving for overeating as a symptom reflecting the common pathogenetic mechanisms of atypical depression and bulimia nervosa, J. Wildes and M. Marcus [44] classify both syndromes as “mild bipolar spectrum” disorders [32]. Patients who complained of hyperphagia often (78%) reported weight gain of 3-6 kg; in 22% of patients, the gained weight reached significant values, increasing by 7-12 kg within a few months.

In 67% of cases, inverse vegetative symptoms (hyperphagia and hypersomnia) were accompanied by complaints of an asthenic nature in the form of a feeling of unusual heaviness in the limbs - "lead paralysis" [39]. Patients described their condition with the words “I feel like after prolonged physical exertion”, “it’s like lead was poured into me”, “it’s like cast-iron legs”, “I can’t move in the chair, I’m so tired”, “it feels like I was carrying two heavy bags." In some patients, sensations of heaviness were accompanied by paresthesia in the extremities: "numbness", "stiffness". The symptom of lead paralysis was observed both short-term - within 20-30 minutes, and long-term - several hours, arising in situations of psycho-emotional stress or spontaneously, without external provocation [5], in various situations (at home, at work, in transport).

Patients described their condition with the words “I feel like after prolonged physical exertion”, “it’s like lead was poured into me”, “it’s like cast-iron legs”, “I can’t move in the chair, I’m so tired”, “it feels like I was carrying two heavy bags." In some patients, sensations of heaviness were accompanied by paresthesia in the extremities: "numbness", "stiffness". The symptom of lead paralysis was observed both short-term - within 20-30 minutes, and long-term - several hours, arising in situations of psycho-emotional stress or spontaneously, without external provocation [5], in various situations (at home, at work, in transport).

The presence of other atypical symptoms in this group of patients was insignificant, confirming the high degree of association of inverse autonomic symptoms. So, for example, mood reactivity occurred in 27.2% of cases, while sensitivity to rejection - only in 36.3%, reflecting a character trait to a greater extent than manifestations of atypical depression. The average severity of depressive disorder was more pronounced than in the previous version (22.8±4.1 according to HAMD). The structure of a constitutional anomaly predisposing to the development of atypical depression with a predominance of inversion of autonomic symptoms is represented by hysterical, psychasthenic, schizoid, and, unlike the previous type of atypical depression, cycloid and hyperthymic features. The clinical features of this variant of atypical depression are shown in fig. 2.

The average severity of depressive disorder was more pronounced than in the previous version (22.8±4.1 according to HAMD). The structure of a constitutional anomaly predisposing to the development of atypical depression with a predominance of inversion of autonomic symptoms is represented by hysterical, psychasthenic, schizoid, and, unlike the previous type of atypical depression, cycloid and hyperthymic features. The clinical features of this variant of atypical depression are shown in fig. 2.

| Fig. 2. Spectrum of atypical symptoms in depression with a predominance of inverse autonomic symptoms according to the ADDS scale (points). |

| ]]> |

The third variant of atypical depression with a predominance of increased sensitivity to rejection of was detected in 32.6% of patients at a later age (42.5 years) . Most of them (87%) were women. Compared with the socio-demographic characteristics of patients in the previous groups, in this group of people with higher and incomplete higher education there were 73%, and the percentage of non-workers reached 60%, of which 56% were due to a mental state.

Most of them (87%) were women. Compared with the socio-demographic characteristics of patients in the previous groups, in this group of people with higher and incomplete higher education there were 73%, and the percentage of non-workers reached 60%, of which 56% were due to a mental state.

Persistent hypothymic affect was combined in these patients with increased resentment, constant anxiety about the attitude of others around them; expectation, as a rule, of imaginary criticism addressed to oneself, an unfavorable opinion of oneself, a tendency to take personally any neutral or insignificant change in the behavior of people who are more often close to them, interpreted by them as rejection, reproach, a catch [1, 16, 17, 25 ]. Patients said that they “take everything to heart”, “friends didn’t invite me to the cinema and I don’t want to communicate with them anymore”, “he called later than he should have, and we had a fight”, “colleagues didn’t invite me to dinner, and I was offended by them. ” The behavioral component of the syndrome in the studied patients is represented by patterned hysterical reactions, rejection reactions [3, 22], dysphoric outbursts with accusations of relatives of lack of understanding and indifference. Individualism in combination with increased vulnerability (the so-called nuanced sensitivity) led to selectivity in contacts, accompanied by emotional rejection similar to that observed in childhood [23] - overt (aggression, avoidance) or covert (emotional hostility and coldness). Reacting with excessive vulnerability, resentment with the formation of avoidant behavior or severe irritability, irascibility, aggression directed at anyone who entered into communication with them (“ready to pounce if they make a remark to me”) [5, 18], patients stopped going to work, study, tried unnecessarily not to enter into communication with relatives. So, one patient did not go to a meeting of her classmates because of the fear of becoming an object of ridicule, another could not pay for the apartment because of a long queue at the bank - "someone will definitely scold me.

” The behavioral component of the syndrome in the studied patients is represented by patterned hysterical reactions, rejection reactions [3, 22], dysphoric outbursts with accusations of relatives of lack of understanding and indifference. Individualism in combination with increased vulnerability (the so-called nuanced sensitivity) led to selectivity in contacts, accompanied by emotional rejection similar to that observed in childhood [23] - overt (aggression, avoidance) or covert (emotional hostility and coldness). Reacting with excessive vulnerability, resentment with the formation of avoidant behavior or severe irritability, irascibility, aggression directed at anyone who entered into communication with them (“ready to pounce if they make a remark to me”) [5, 18], patients stopped going to work, study, tried unnecessarily not to enter into communication with relatives. So, one patient did not go to a meeting of her classmates because of the fear of becoming an object of ridicule, another could not pay for the apartment because of a long queue at the bank - "someone will definitely scold me. " The consequence of such inadequate reactions was frequently occurring difficulties in interpersonal relationships, which further strengthened the patients in the thoughts that they were rejected [25], leading in severe cases to ideas of their own low value, phobic experiences and social maladjustment [39]. Often in the clinical picture of the condition, a significant place was occupied by symptoms of persistent asthenia with complaints of lack of strength: “didn’t do anything, but fatigue was like after a whole day of work.”

" The consequence of such inadequate reactions was frequently occurring difficulties in interpersonal relationships, which further strengthened the patients in the thoughts that they were rejected [25], leading in severe cases to ideas of their own low value, phobic experiences and social maladjustment [39]. Often in the clinical picture of the condition, a significant place was occupied by symptoms of persistent asthenia with complaints of lack of strength: “didn’t do anything, but fatigue was like after a whole day of work.”

The severity of behavioral disorders in this group of patients was noted by many authors, who in such cases single out a special vulnerable type of personality with idealization and romanticization of the surrounding reality against the background of emotional immaturity, excessive enthusiasm and hypersensitivity to interpersonal relationships, rejection of situations that hurt their pride and frustrating their need for attention, approval and recognition, expressed by a sense of inner protest against the prevailing circumstances (fate), the need for liberation from "injustice" in combination with excessive, unrealistic demands on oneself and especially others [1, 21, 28, 30]. This type of personality, characterized by amalgamation of pathocharacterological and hypothymic disorders, was designated as hysterical dysphoria [2, 20–22]. Other atypical symptoms for this group of patients were characterized by the presence of lead paralysis (73%) and mood reactivity (60%), while the severity of such signs of atypical depression as hypersomnia and hyperphagia was minimal - 13 and 20%, respectively ( Fig. 3).

This type of personality, characterized by amalgamation of pathocharacterological and hypothymic disorders, was designated as hysterical dysphoria [2, 20–22]. Other atypical symptoms for this group of patients were characterized by the presence of lead paralysis (73%) and mood reactivity (60%), while the severity of such signs of atypical depression as hypersomnia and hyperphagia was minimal - 13 and 20%, respectively ( Fig. 3).

| Fig. 3. The spectrum of atypical symptoms in depression with a predominance of sensitivity to rejection according to the ADDS scale (points). |

| ]]> |

The personality structure characteristic of this variant of atypical depression was represented by psychasthenic, hysterical, paranoid, and schizoid features, with the severity of the first three exceeding those in patients with other variants. A feature of patients in this group was the actual absence of individuals with hyper- and cyclothymic features.

A feature of patients in this group was the actual absence of individuals with hyper- and cyclothymic features.

The identified variants of atypical depression reflect a different stereotype of the dynamics of affective pathology (see table).

In these cases (38.4%), the disease usually began at the age of 28±11 years with a mild depressive episode that had a psychogenic provocation with inclusions of atypical symptoms, mainly in the form of mood reactivity and asthenic complaints (similar to lead paralysis). From the time of onset of the first symptoms of the disease to the age of the patients when the diagnosis was made (40.2±14 years), patients suffered an average of 2.8±0.7 depressive episodes lasting from 60 to 180 days, of varying severity and structure - with alternation more severe depressions with melancholic features and suicidal ideas, more often occurring in milder phases with a predominance of mood reactivity, which, although it was the main clinical characteristic of depression, had a clear tendency to decrease in the amplitude of affect fluctuations in dynamics. Less often (15.3%), this variant of atypical depression was observed in the structure of bipolar disorder. In this case, an earlier development of the disease was noted (at the age of 25.5±9, 1 year), visits to a doctor almost at the first symptoms of the disease, high frequency and severity of depressive and manic/hypomanic episodes, high frequency of visits to a psychiatrist. Less often (15.3%), this variant of atypical depression was observed in the structure of bipolar disorder. In this case, an earlier development of the disease was noted (at the age of 25.5±9, 1 year), visits to a doctor almost at the first symptoms of the disease, high frequency and severity of depressive and manic/hypomanic episodes, high frequency of visits to a psychiatrist. A variant of atypical depression with a predominance of inverted vegetative symptoms was characteristic of bipolar disorder (33.3%) and practically did not occur in recurrent course (5.5%). The disease manifested, as a rule, at a younger age (20.1 ± 7.1 years) from a mixed state, in the structure of which there were short-term episodes of increased appetite and daytime sleepiness. The further course of the disease was characterized by an alternation of depressive and hypomanic episodes with a deepening of depressive phases and vegetative manifestations characteristic of this type of atypical depression, leading to significant maladaptation (loss of work, study) and referral to a psychiatrist (mean age 26. The variant of atypical depression with a predominance of sensitivity to rejection, as well as with mood reactivity, is more characteristic of recurrent depressive disorder (26.6%) and almost never occurred in the structure of the bipolar course of the disease (6.6%). Depression, as a rule, developed at the age of involution (48.75±1.4 years), most often due to pronounced stressful effects (death of a loved one, dismissal from work, divorce). Repeated episodes that proceeded with similar clinical symptoms of the "cliché" type were provoked by individually intolerable conflict situations, the content of which "sounded" throughout the entire depressive episode. Anamnestic studies revealed periods of low mood at a subclinical level associated with “loss” (romantic relationships) or “failure” in solving important life tasks (career growth, creating a family). |

1 ± 3.7 years) . The euthymic intervals tended to shorten or, more rarely, the disease immediately acquired a continual course.

1 ± 3.7 years) . The euthymic intervals tended to shorten or, more rarely, the disease immediately acquired a continual course.