Lymes disease and depression

New-Onset Panic, Depression with Suicidal Thoughts, and Somatic Symptoms in a Patient with a History of Lyme Disease

- Journal List

- Case Rep Psychiatry

- v.2015; 2015

- PMC4397473

Case Rep Psychiatry. 2015; 2015: 457947.

Published online 2015 Apr 1. doi: 10.1155/2015/457947

1 , 2 , 3 , * and 4

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

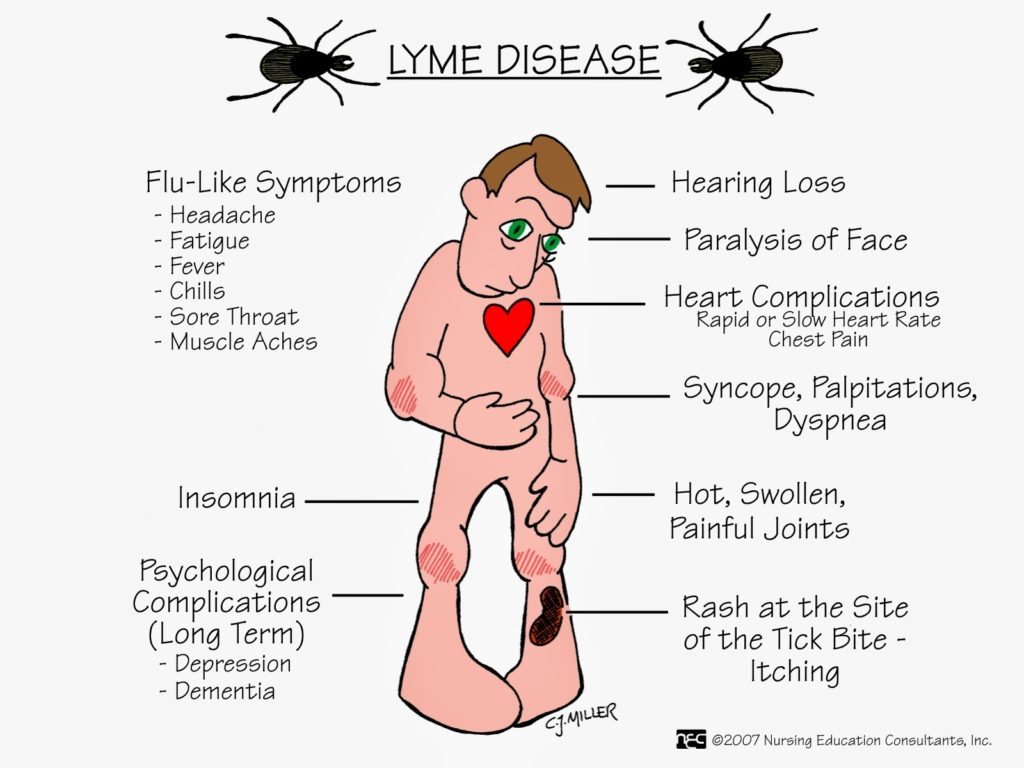

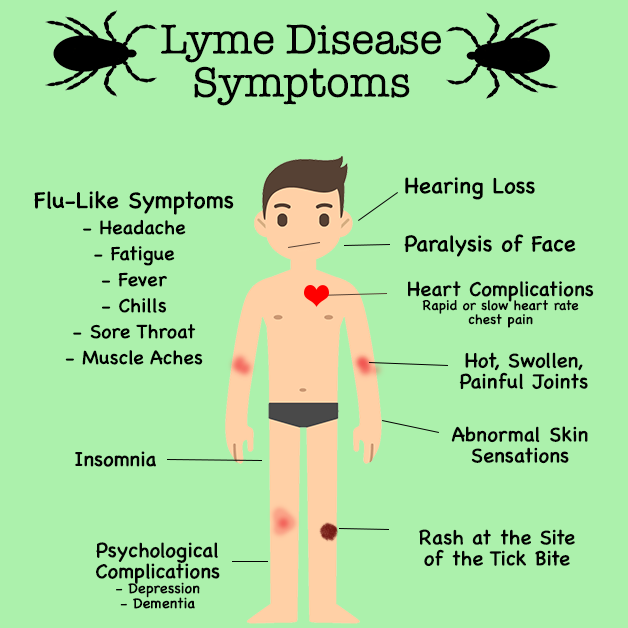

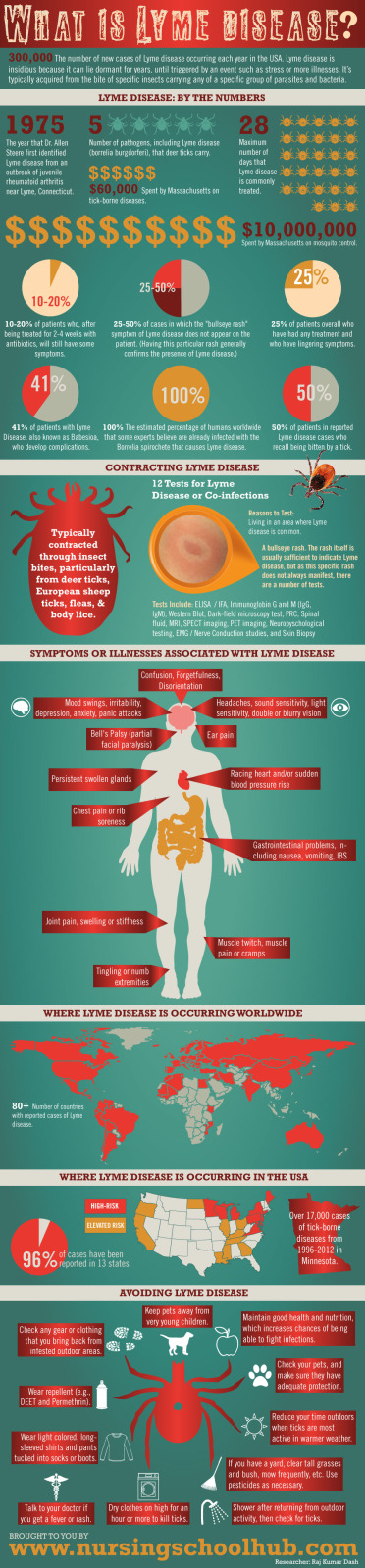

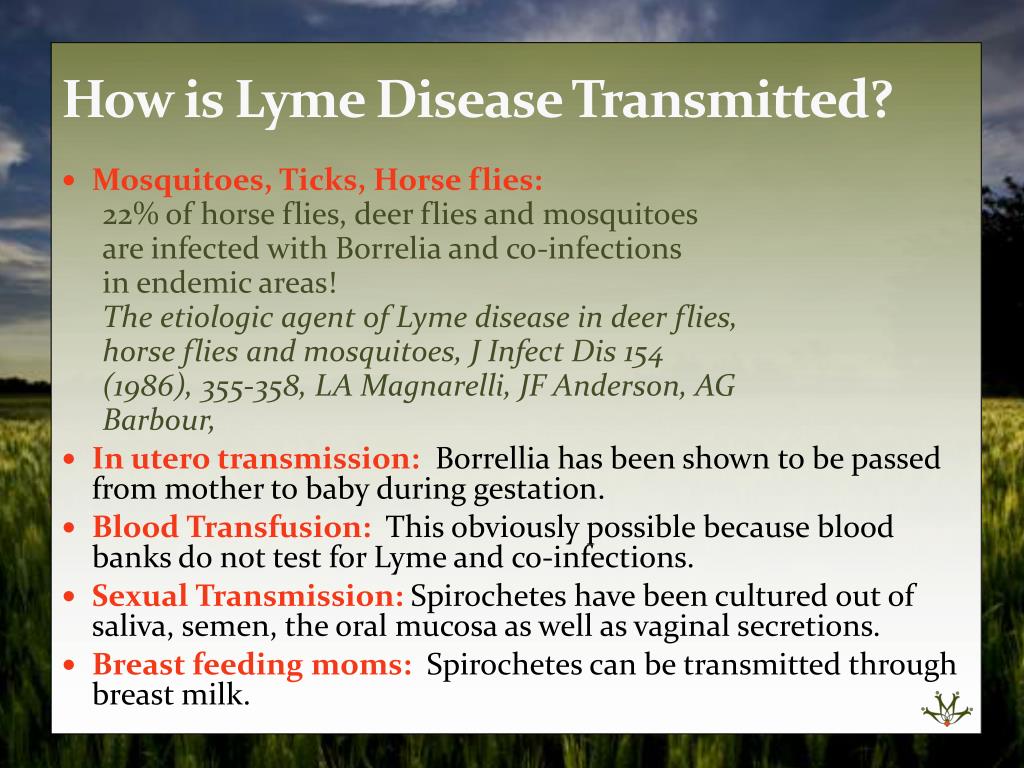

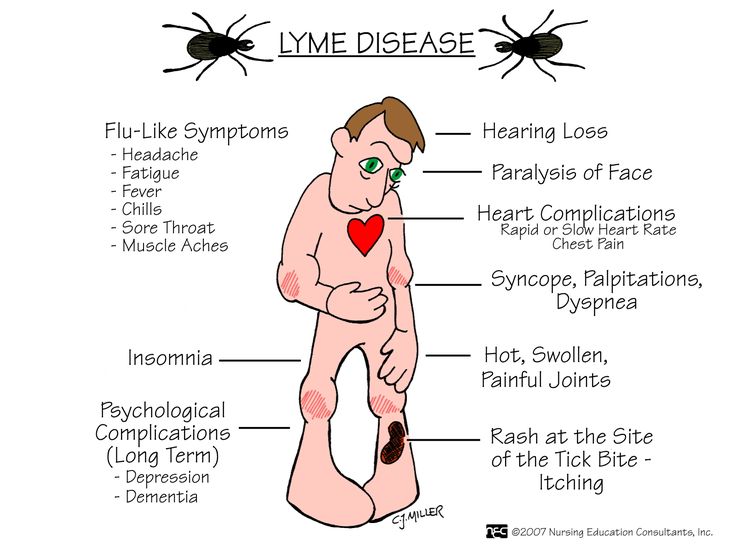

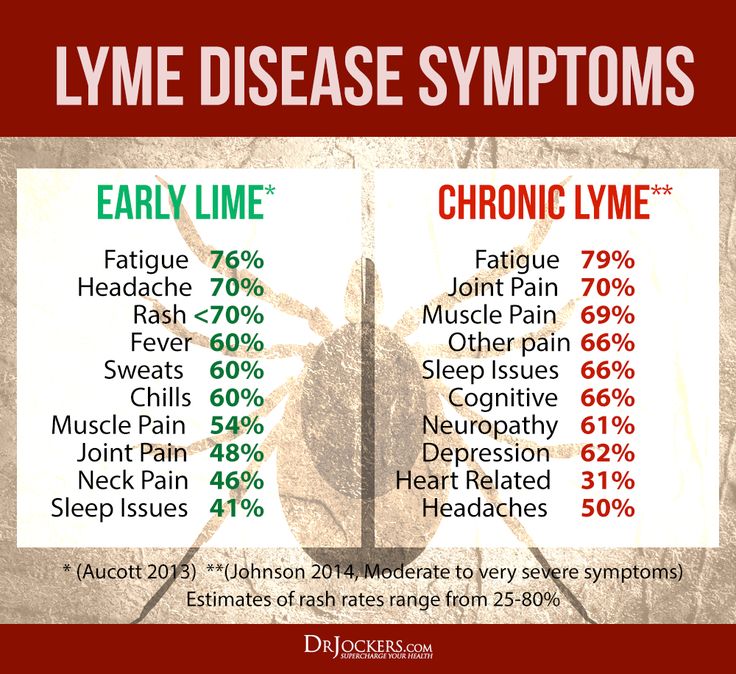

Lyme Disease, or Lyme Borreliosis, caused by Borrelia burgdorferi and spread by ticks, is mainly known to cause arthritis and neurological disorders but can also cause psychiatric symptoms such as depression and anxiety.

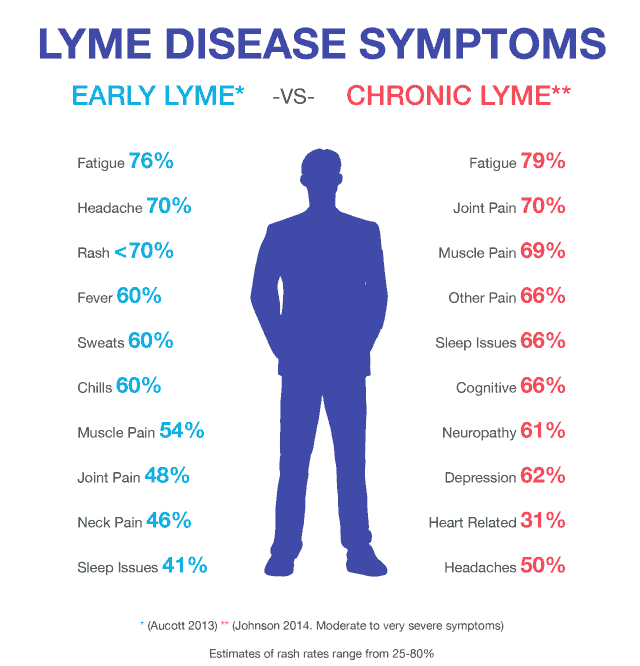

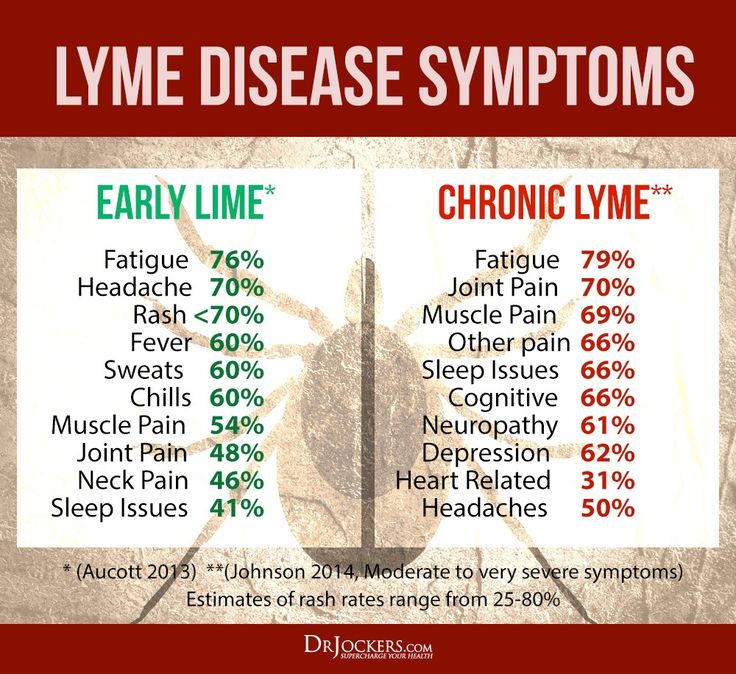

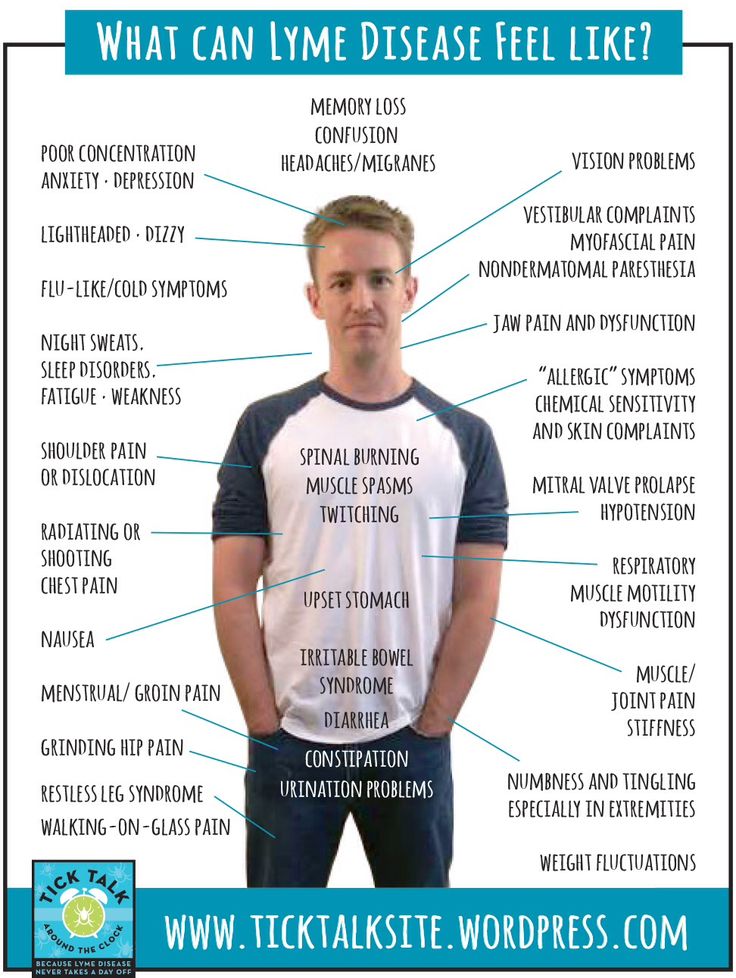

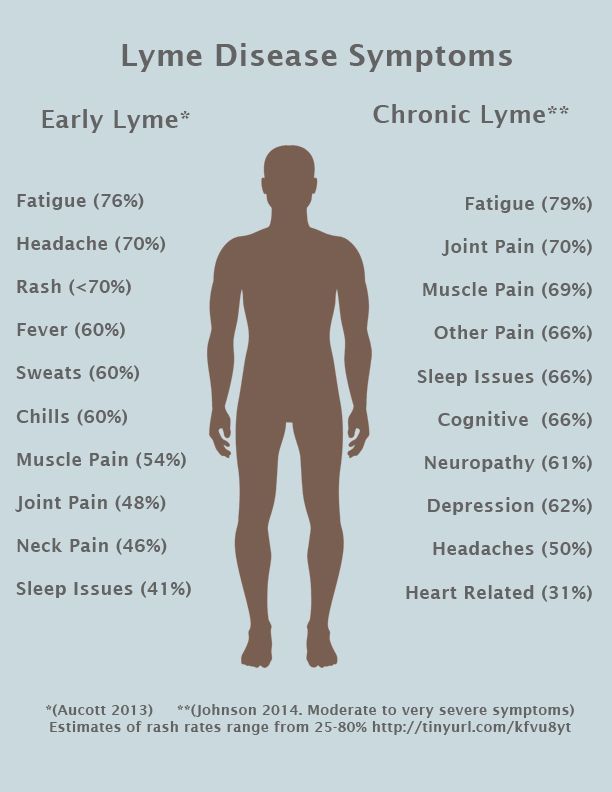

We present a case of a 37-year-old man with no known psychiatric history who developed panic attacks, severe depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation, and neuromuscular complaints including back spasms, joint pain, myalgias, and neuropathic pain. These symptoms began 2 years after being successfully treated for a positive Lyme test after receiving a tick bite. During inpatient psychiatric hospitalization his psychiatric and physical symptoms did not improve with antidepressant and anxiolytic treatments. The patient's panic attacks resolved after he was discharged and then, months later, treated with long-term antibiotics for suspected “chronic Lyme Disease” (CLD) despite having negative Lyme titers. He however continued to have subsyndromal depressive symptoms and chronic physical symptoms such as fatigue, myalgias, and neuropathy. We discuss the controversy surrounding the diagnosis of CLD and concerns and considerations in the treatment of suspected CLD patients with comorbid psychiatric diagnoses.

Lyme Disease, caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi and transmitted to humans by ticks (Ixodes spp.), is reported to be one of the most common vector-borne infections in the United States [1]. In a subset of patients previously infected with Lyme Borreliosis (LB), psychiatric sequelae can occur, most commonly depression with reports ranging across studies from 26% to 66% [2]. Additionally, there are case reports of panic attacks in patients with LB infections and a reported 5.3% prevalence of panic disorder in patients at a Lyme Disorders clinic [3–6]. We present a case of a man who has no known prior psychiatric history who presented to the hospital with severe anxiety, panic, depression, and suicidal thinking in addition to multiple somatic symptoms that began 2 years after receiving antibiotic treatment for LB.

The patient was a 37-year-old employed man who self-presented to the emergency department complaining of severe anxiety and suicidal ideas. For 3 months he had been experiencing palpitations, tremulousness, chest pressure, choking sensation, and an intense fear of dying. These symptoms would last for hours. He began seeing a psychiatrist 2 months prior and was started on sertraline that was titrated up to 200 mg a day, along with clonazepam 0.5 mg as needed (he was taking around 1-2 mg a day on average). The patient experienced minimal relief of his symptoms despite these therapies. He felt that the sertraline was worsening his symptoms and was tapered off of it. He reported back pain and muscle spasms, weakness and tingling in his arms and legs, and general fatigue. His physical symptoms contributed to his poor sleep, low energy, loss of interest in his job and social activities, and loss of appetite, with a 10-pound weight loss during the previous 2 months. He also reported a sense of hopelessness that “things will never get better” and was having persisting suicidal thoughts without intent or a plan. He reported no prior history of suicide attempts or self-injury.

For 3 months he had been experiencing palpitations, tremulousness, chest pressure, choking sensation, and an intense fear of dying. These symptoms would last for hours. He began seeing a psychiatrist 2 months prior and was started on sertraline that was titrated up to 200 mg a day, along with clonazepam 0.5 mg as needed (he was taking around 1-2 mg a day on average). The patient experienced minimal relief of his symptoms despite these therapies. He felt that the sertraline was worsening his symptoms and was tapered off of it. He reported back pain and muscle spasms, weakness and tingling in his arms and legs, and general fatigue. His physical symptoms contributed to his poor sleep, low energy, loss of interest in his job and social activities, and loss of appetite, with a 10-pound weight loss during the previous 2 months. He also reported a sense of hopelessness that “things will never get better” and was having persisting suicidal thoughts without intent or a plan. He reported no prior history of suicide attempts or self-injury. The patient stated that he had no psychiatric contact before two months. He reported that he had been diagnosed with Lyme Disease 2 years prior when he developed fatigue, tinnitus, headaches, fever, and other flu-like symptoms 1 month after pulling a tick off his leg. He had a positive Lyme ELISA antibody at that time from a local hospital laboratory. He had been treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 3 weeks. Besides some occasional mild headaches he had an almost 2-year cessation in symptoms until he began developing muscle aches, spasms, fatigue, and worsening anxiety in the past 2 months. He reported having presented to the ER multiple times for his anxiety and neuromuscular complaints but that an ELISA Lyme antibody test, from 3 weeks prior, had been negative (no Western Blot was sent since the ELISA was negative), as was the rest of his medical workup.

The patient stated that he had no psychiatric contact before two months. He reported that he had been diagnosed with Lyme Disease 2 years prior when he developed fatigue, tinnitus, headaches, fever, and other flu-like symptoms 1 month after pulling a tick off his leg. He had a positive Lyme ELISA antibody at that time from a local hospital laboratory. He had been treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 3 weeks. Besides some occasional mild headaches he had an almost 2-year cessation in symptoms until he began developing muscle aches, spasms, fatigue, and worsening anxiety in the past 2 months. He reported having presented to the ER multiple times for his anxiety and neuromuscular complaints but that an ELISA Lyme antibody test, from 3 weeks prior, had been negative (no Western Blot was sent since the ELISA was negative), as was the rest of his medical workup.

The patient was admitted to inpatient psychiatry for depression and suicidal ideas and treated with escitalopram which was titrated up to 10 mg a day with some improvement in mood. Nonetheless, he complained that his cramping, flank pain, and fatigue and panic did not improve. He required several doses of as-needed lorazepam which improved his anxiety symptoms only slightly. He was started on propranolol 10 mg three times daily but noted no improvement in his anxiety. Concurrently, he was seen by a Medicine consultant whose physical exam, including a complete neurological and cranial nerve examination, was unremarkable. Despite report of arthritic pain his knees and other joints were not swollen on exam. His Lyme Western Blot was negative (fewer than 5 out of 10 of the following IgG bands: 18, 23, 28, 30, 39, 41, 45, 58, 66, or 93 kDa; fewer than 2 of the following IgM bands: 23, 39, or 41 kDa), and other blood work, including a comprehensive metabolic panel, CBC, TSH, RPR, Vitamin B12, Folate, ESR, ANA, and CRP, was all negative or within normal limits (except for moderately low platelets, 120 × 10

9/L). His urine drug screen was negative and he denied using or abusing any illicit drugs or alcohol.

Nonetheless, he complained that his cramping, flank pain, and fatigue and panic did not improve. He required several doses of as-needed lorazepam which improved his anxiety symptoms only slightly. He was started on propranolol 10 mg three times daily but noted no improvement in his anxiety. Concurrently, he was seen by a Medicine consultant whose physical exam, including a complete neurological and cranial nerve examination, was unremarkable. Despite report of arthritic pain his knees and other joints were not swollen on exam. His Lyme Western Blot was negative (fewer than 5 out of 10 of the following IgG bands: 18, 23, 28, 30, 39, 41, 45, 58, 66, or 93 kDa; fewer than 2 of the following IgM bands: 23, 39, or 41 kDa), and other blood work, including a comprehensive metabolic panel, CBC, TSH, RPR, Vitamin B12, Folate, ESR, ANA, and CRP, was all negative or within normal limits (except for moderately low platelets, 120 × 10

9/L). His urine drug screen was negative and he denied using or abusing any illicit drugs or alcohol. He denied taking any over-the-counter or other nonprescription medications. His ECG showed normal sinus rhythm. His Mini-Mental State Exam was normal (30/30) despite his complaint that he was very forgetful at home and would often not recall having taken his medications or where he had left common household items. He also complained of poor attention and focus. The patient was frustrated by the persistence of his neurological symptoms which further contributed to his hopelessness and passive thoughts of dying. He agreed to adding mirtazapine 15 mg at bedtime to his regimen and his mood symptoms improved. He however continued to complain of fatigue, weakness, back and leg spasms, and “shooting pains” in his hands, stating that the pain and tingling were “rising up” in his body. The patient, however, no longer felt unsafe and agreed with plan for discharging to home, on Day 8, with referrals for a psychiatry, neurology and internal medicine appointment.

He denied taking any over-the-counter or other nonprescription medications. His ECG showed normal sinus rhythm. His Mini-Mental State Exam was normal (30/30) despite his complaint that he was very forgetful at home and would often not recall having taken his medications or where he had left common household items. He also complained of poor attention and focus. The patient was frustrated by the persistence of his neurological symptoms which further contributed to his hopelessness and passive thoughts of dying. He agreed to adding mirtazapine 15 mg at bedtime to his regimen and his mood symptoms improved. He however continued to complain of fatigue, weakness, back and leg spasms, and “shooting pains” in his hands, stating that the pain and tingling were “rising up” in his body. The patient, however, no longer felt unsafe and agreed with plan for discharging to home, on Day 8, with referrals for a psychiatry, neurology and internal medicine appointment.

The patient contacted the hospital's outpatient clinic 9 months after discharge to arrange reinstitution of care. He states that after discharge he visited multiple internists and neurologists and had several ELISA Lyme tests which were negative and Western Blots which were also negative for the required IgM and IgG bands (see above). He then traveled to a specialist in another state who sent blood work to IGeneX Laboratories, Inc., in California, which came back positive for Borrelia and Babesiosis on Bands 31 and 34 for IgG. In addition, he reported that his CD57 count was low (352). He was begun on a 6-month course of oral antibiotics including 3 months of tetracycline and 3 months of azithromycin and fluconazole. At that time, his brain MRI with and without contrast was negative for any white matter or other changes or disease. The patient denied further cognitive deficits since his antibiotic treatment. Patient attempted to have neuropsychological testing and functional imaging but this was not covered by his insurance and he could not obtain them due to the cost.

He states that after discharge he visited multiple internists and neurologists and had several ELISA Lyme tests which were negative and Western Blots which were also negative for the required IgM and IgG bands (see above). He then traveled to a specialist in another state who sent blood work to IGeneX Laboratories, Inc., in California, which came back positive for Borrelia and Babesiosis on Bands 31 and 34 for IgG. In addition, he reported that his CD57 count was low (352). He was begun on a 6-month course of oral antibiotics including 3 months of tetracycline and 3 months of azithromycin and fluconazole. At that time, his brain MRI with and without contrast was negative for any white matter or other changes or disease. The patient denied further cognitive deficits since his antibiotic treatment. Patient attempted to have neuropsychological testing and functional imaging but this was not covered by his insurance and he could not obtain them due to the cost.

He stated that he was no longer taking SSRI medication or mirtazapine and only rarely took lorazepam as needed for anxiety but was eventually tapered off per the patient's request. He no longer reported panic attacks or periods of hopelessness or suicidal thoughts. He said he was trying to use relaxation and yoga and natural approaches to his anxiety and physical symptoms. Nonetheless, he reported being despondent and frustrated by the lack of improvement in his physical symptoms, which caused him to have to leave his job and go on disability. He still has fatigue, weakness, low energy, pain and spasms in his back and upper legs, and nonspecific joint pain but stated he was only on multivitamins and minerals and no other standing medications. He agreed to a low dose of gabapentin, 100 mg three times daily, which was titrated up as tolerated and helped alleviate some of his anxiety and neuropathic pain.

He no longer reported panic attacks or periods of hopelessness or suicidal thoughts. He said he was trying to use relaxation and yoga and natural approaches to his anxiety and physical symptoms. Nonetheless, he reported being despondent and frustrated by the lack of improvement in his physical symptoms, which caused him to have to leave his job and go on disability. He still has fatigue, weakness, low energy, pain and spasms in his back and upper legs, and nonspecific joint pain but stated he was only on multivitamins and minerals and no other standing medications. He agreed to a low dose of gabapentin, 100 mg three times daily, which was titrated up as tolerated and helped alleviate some of his anxiety and neuropathic pain.

Our patient presented with psychiatric symptoms and hospitalization about 2 years after a recommended course of antibiotics for diagnosed LB. His persisting psychiatric symptoms and lack of prior history of panic or depression bring up the possibility that his previous infection with LB played a role in the later development anxiety and panic attacks. There is ample evidence supporting the emergence of psychiatric symptoms including severe anxiety and depression, even months to years, after diagnosis and treatment of Lyme Disease [2–7]. The patient's laboratory studies and clinical exam did not exhibit any other signs or symptoms to suggest rheumatologic diseases like lupus and rheumatoid arthritis or a malignancy. He had no neurological sequelae and a negative brain MRI (which ruled out diseases such as multiple sclerosis) and despite his report of cognitive deficits he had no objective symptoms on admission. Unfortunately he never received neuropsychological testing or underwent SPECT or PET imaging [8]. He also was not tested for immune markers like cytokines, an important consideration given that CNS inflammation may be a part of untreated Lyme or prolonged exposure to Borrelia before initial treatment [9].

There is ample evidence supporting the emergence of psychiatric symptoms including severe anxiety and depression, even months to years, after diagnosis and treatment of Lyme Disease [2–7]. The patient's laboratory studies and clinical exam did not exhibit any other signs or symptoms to suggest rheumatologic diseases like lupus and rheumatoid arthritis or a malignancy. He had no neurological sequelae and a negative brain MRI (which ruled out diseases such as multiple sclerosis) and despite his report of cognitive deficits he had no objective symptoms on admission. Unfortunately he never received neuropsychological testing or underwent SPECT or PET imaging [8]. He also was not tested for immune markers like cytokines, an important consideration given that CNS inflammation may be a part of untreated Lyme or prolonged exposure to Borrelia before initial treatment [9].

The diagnosis of “chronic Lyme Disease” (CLD) is controversial and there is conflicting evidence on whether physical symptoms can persist in Lyme after a person is treated with a recommended course of antibiotics [10]. There is evidence for a “post-Lyme Disease Syndrome” (PLDS) which may cause persisting fatigue, myalgias, and neurocognitive deficits that can remain for years even after treatment, exclusive of and distinct from fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) [10, 11]. PLDS, however, has criteria which exclude the diagnosis if the subjective symptoms are not present within 6 months of diagnosis of Lyme or completion of antibiotic treatment or if there is a coinfection [10]. For PLDS, several randomized, controlled studies have reported improvement in neurocognition or fatigue after 6 or more months of IV antibiotic treatment although the risk of serious side effects limits this practice [10, 12]. In our case, the patient's episodic pain and fatigue are not consistent with fibromyalgia (absence of the trigger points on exam) or CFS (severe fatigue did not persist for 6 or more months) and he had no history of either prior to his first Lyme infection. The patient also had symptom onset around 2 years after his infection and no evidence of a recent reinfection due to negative Western Blot and a positive Babesiosis test, which rule out PLDS.

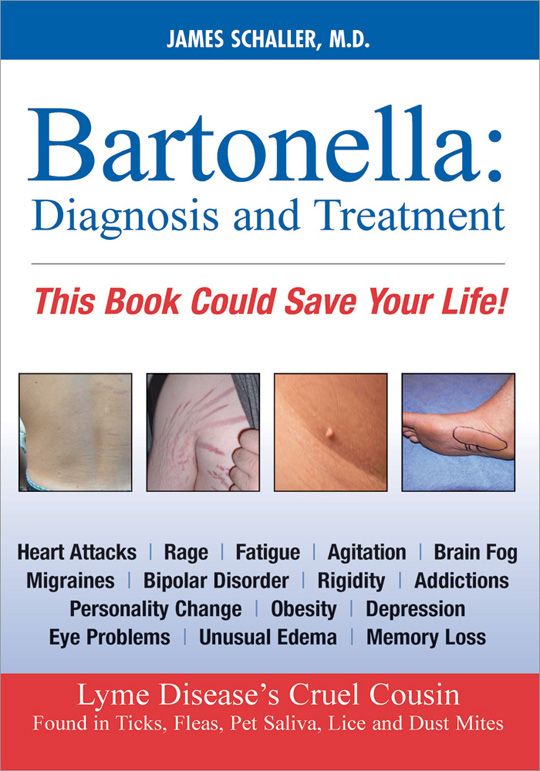

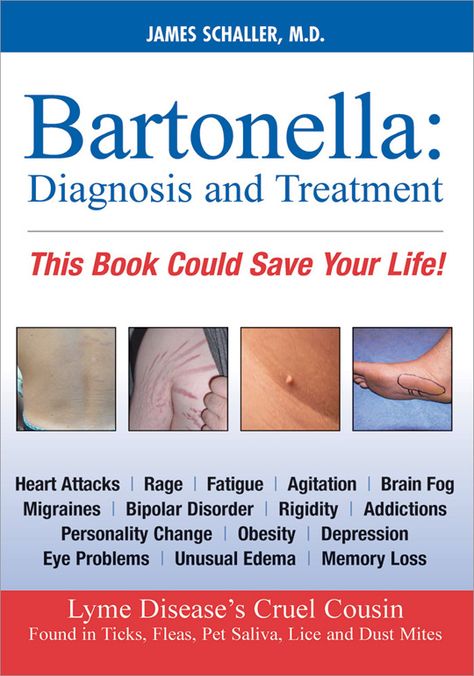

There is evidence for a “post-Lyme Disease Syndrome” (PLDS) which may cause persisting fatigue, myalgias, and neurocognitive deficits that can remain for years even after treatment, exclusive of and distinct from fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) [10, 11]. PLDS, however, has criteria which exclude the diagnosis if the subjective symptoms are not present within 6 months of diagnosis of Lyme or completion of antibiotic treatment or if there is a coinfection [10]. For PLDS, several randomized, controlled studies have reported improvement in neurocognition or fatigue after 6 or more months of IV antibiotic treatment although the risk of serious side effects limits this practice [10, 12]. In our case, the patient's episodic pain and fatigue are not consistent with fibromyalgia (absence of the trigger points on exam) or CFS (severe fatigue did not persist for 6 or more months) and he had no history of either prior to his first Lyme infection. The patient also had symptom onset around 2 years after his infection and no evidence of a recent reinfection due to negative Western Blot and a positive Babesiosis test, which rule out PLDS. We considered several other diagnoses including coinfections with Bartonella, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, West Nile, and other mosquito-borne illnesses but ruled them out due to the absence of laboratory or clinical evidence and the unlikelihood of persisting symptoms after recommended antibiotic treatment [13].

We considered several other diagnoses including coinfections with Bartonella, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, West Nile, and other mosquito-borne illnesses but ruled them out due to the absence of laboratory or clinical evidence and the unlikelihood of persisting symptoms after recommended antibiotic treatment [13].

Many infectious disease experts refute the existence of CLD on the grounds that there is no evidence of any latent spirochetal infection that would explain the ongoing symptoms or that the person's presentation can be explained by another diagnosis like fibromyalgia, CFS, or psychiatric disorders like depression [10, 14–17]. Some Lyme experts posit ethical concerns about providing patients with hope of a potentially unidentifiable cause to their distress and then offering prolonged and potentially unsafe courses of antibiotics without clear efficacy [10, 16]. They note that advocacy groups encourage patients to seek out “Lyme-literate medical doctors” (LLMDs) and be wary of the so-called “expert” recommendations [16, 17]. Additionally, there previously had been concerns about the validity of the positive results of Lyme tests of certain laboratories including IGeneX, where our patient had a positive result, although proponents of the laboratory note that IGeneX, Inc., is licensed in several states and tests for bands not measured at other laboratories, which use CDC criteria [16, 18, 19]. Also, the utility of natural killer T cell counts (like CD57) as a marker is controversial [20].

Additionally, there previously had been concerns about the validity of the positive results of Lyme tests of certain laboratories including IGeneX, where our patient had a positive result, although proponents of the laboratory note that IGeneX, Inc., is licensed in several states and tests for bands not measured at other laboratories, which use CDC criteria [16, 18, 19]. Also, the utility of natural killer T cell counts (like CD57) as a marker is controversial [20].

In patients experiencing chronic fatigue, depression, and unexplained anxiety and suffering from cognitive deficits, a diagnosis and concomitant treatment hold much promise and relief for the patient and provider [21]. A recent study reported that 30% of patients presenting to a Borrelia clinic has “Organically Unexplained Symptoms” and that this group had more symptoms and worse outcomes, were more dissatisfied with their care, and felt less reassured by the medical establishment [22]. Indeed, our patient felt stigmatized and marginalized by many providers and was labeled as “psychosomatic” by some and by others led to believe that all of his symptoms were related to Lyme or related infections and was given protracted courses of antibiotics. Auwaerter and Melia, referencing Whitson and Galinsky, posit the idea that “the suggestion that an infectious agent continues to cause chronic symptoms may speak to the observed tendency for patients to develop illusory patterns of perception when they lack control” [17, 23]. Well-meaning physicians often reinforce a patient's fixation on the diagnosis by empirically prescribing antibiotics for those with nonspecific symptoms and negative or nondiagnostic Lyme serology or those with nonspecific symptoms and positive Lyme disease serology.

It is further conceivable that beyond CLD as an explanation for the patient's symptoms is the well-documented response of depression and anxiety symptoms secondary to chronic illness [24]. The patient went through a prolonged period of uncertainty, was subjected to multiple treatment therapies, and experienced new onset and distressing symptoms; this experience in its entirety could likewise exacerbate the patient's presenting symptoms. In reality, the optimal approach in cases like ours would have laid somewhere in between both a purely biological and psychological explanation and treatment frame, where this patient would have received ongoing psychiatric care, including antidepressant medications and possibly anxiolytics to treat his mood and anxiety symptoms, and psychotherapy such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to help him cope with his chronic physical illness and ongoing treatment and evaluation of his physical symptoms, with a clear explanation that a firm diagnosis may not be reached. In fact current research shows a strongly synergistic effect of both medication and CBT intervention in treating chronic illness associated with mood symptoms [25]. Treatment with pregabalin or gabapentin, as is being used in our patient, may also alleviate anxiety and underlying neuropathic pain symptoms as well, although their use in anxiety is not FDA-approved and thus is off-label [10, 26].

While we do not set out to argue the clinical validity of a diagnosis of CLD and its correlation to neuropsychiatric symptoms, our hope was to present a case that would illustrate the complexity of evaluating and treating a patient with chronic and disabling physical and psychiatric symptoms but without a clear diagnosis. In treating a patient with a history of suspected Lyme, special attention should be paid to ruling out other infections and Lyme reinfection and to diagnosing preexisting psychiatric conditions before a definitive diagnosis is made. These should be done by taking a thorough history, gathering collateral and old records, and consulting qualified specialists, with whom care should be coordinated, along with the patient's internist, to ensure the patient feels his concerns are being addressed, while minimizing the patient's tendency to overuse the healthcare system including requesting unnecessary tests or treatments. Additionally referral to therapy, specifically evidence based modalities such as CBT, can help to address and empower the patient faced with distressing psychological symptoms and a prolonged diagnostic and treatment course. Most importantly, a patient and empathic stance are crucial to ensure that patient remains connected to care and feels as if his or her concerns are being heard [10].

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

1. Steere A. C. Lyme disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345(2):115–125. doi: 10.1056/nejm200107123450207. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. Fallon B. A., Nields J. A. Lyme disease: a neuropsychiatric illness. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151(11):1571–1583. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.11.1571. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Fallon B. A., Nields J. A., Parsons B., Liebowitz M. R., Klein D. F. Psychiatric manifestations of Lyme borreliosis. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1993;54(7):263–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Fallon B. A., Schwartzberg M., Bransfield R., et al. Late-stage neuropsychiatric lyme borreliosis: differential diagnosis and treatment. Psychosomatics. 1995;36(3):295–300. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3182(95)71669-3. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Sherr V. T. Panic attacks may reveal previously unsuspected chronic disseminated lyme disease. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2000;6(6):352–356. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200011000-00005. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Hassett A. L., Radvanski D. C., Buyske S., Savage S. V., Sigal L. H. Psychiatric comorbidity and other psychological factors in patients with ‘chronic Lyme disease’ American Journal of Medicine. 2009;122(9):843–850. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.02.022. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Hassett A. L., Radvanski D. C., Buyske S., et al. Role of psychiatric comorbidity in chronic Lyme disease. Arthritis Care and Research. 2008;59(12):1742–1749. doi: 10.1002/art.24314. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Fallon B. A., Levin E. S., Schweitzer P. J., Hardesty D. Inflammation and central nervous system Lyme disease. Neurobiology of Disease. 2010;37(3):534–541. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.11.016. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Jacek E., Fallon B. A., Chandra A., Crow M. K., Wormser G. P., Alaedini A. Increased IFNα activity and differential antibody response in patients with a history of Lyme disease and persistent cognitive deficits. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2013;255(1-2):85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.10.011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Lantos P. M. Chronic Lyme disease: the controversies and the science. Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. 2011;9(7):787–797. doi: 10.1586/eri.11.63. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Cairns V., Godwin J. Post-Lyme borreliosis syndrome: a meta-analysis of reported symptoms. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;34(6):1340–1345. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi129. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Fallon B. A., Petkova E., Keilp J. G., Britton C. B. A reappraisal of the U.S. clinical trials of post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome. The Open Neurology Journal. 2012;6:79–87. doi: 10.2174/1874205x01206010079. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Berghoff W. Chronic lyme disease and co-infections: differential diagnosis. The Open Neurology Journal. 2012;6(1):158–178. doi: 10.2174/1874205x01206010158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Sigal L. H., Hassett A. L. Commentary: ‘What's in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.’ Shakespeare W. Romeo and Juliet, II, ii(47-48) International Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;34(6):1345–1347. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi180. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Feder H. M., Jr., Johnson B. J. B., O'Connell S., et al. A critical appraisal of ‘chronic lyme disease’ The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(14):1422–1430. doi: 10.1056/nejmra072023. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Auwaerter P. G., Bakken J. S., Dattwyler R. J., et al. Antiscience and ethical concerns associated with advocacy of Lyme disease. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2011;11(9):713–719. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70034-2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Auwaerter P. G., Melia M. T. Bullying Borrelia: when the culture of science is under attack. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. 2012;123:79–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Whelan D. Forbes. Lyme; 2007. () http://www.forbes.com/forbes/2007/0312/096.html. [Google Scholar]

19. FDA Public Health Advisory. Assays for Antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi; Limitations, Use, and Interpretation for Supporting a Clinical Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. 2013. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/PublicHealthNotifications/ucm062429.htm. [Google Scholar]

20. Marques A., Brown M. R., Fleisher T. A. Natural killer cell counts are not different between patients with post-Lyme disease syndrome and controls. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology. 2009;16(8):1249–1250. doi: 10.1128/cvi.00167-09. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Specter M. The lyme wars. The New Yorker. 2013 http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2013/07/01/130701fa_fact_specter. [Google Scholar]

22. Csallner G., Hofmann H., Hausteiner-Wiehle C. Patients with ‘organically unexplained symptoms’ presenting to a borreliosis clinic: clinical and psychobehavioral characteristics and quality of life. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(4):359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2012.08.012. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. Whitson J. A., Galinsky A. D. Lacking control increases illusory pattern perception. Science. 2008;322(5898):115–117. doi: 10.1126/science.1159845. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

24. Cassileth B. R., Lusk E. J., Strouse T. B., et al. Psychosocial status in chronic illness—a comparative analysis of six diagnostic groups. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1984;311(8):506–511. doi: 10.1056/nejm198408233110805. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Khalsa S. S., Shahabi L., Ajijola O. A., Bystritsky A., Naliboff B. D., Shivkumar K. Synergistic application of cardiac sympathetic decentralization and comprehensive psychiatric treatment in the management of anxiety and electrical storm. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 2014;7, article 98 doi: 10.3389/fnint.2013.00098. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Weissenbacher S., Ring J., Hofmann H. Gabapentin for the symptomatic treatment of chronic neuropathic pain in patients with late-stage lyme borreliosis: a pilot study. Dermatology. 2005;211(2):123–127. doi: 10.1159/000086441. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Articles from Case Reports in Psychiatry are provided here courtesy of Hindawi Limited

Lyme Disease and Depression - Dr. Todd Maderis

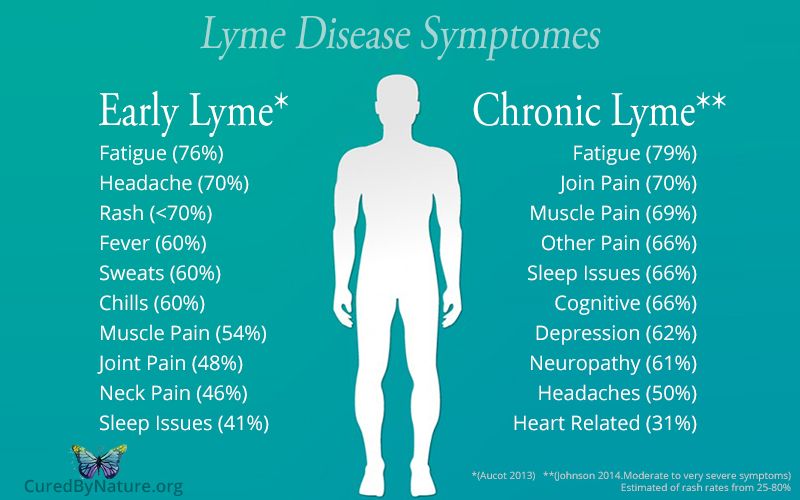

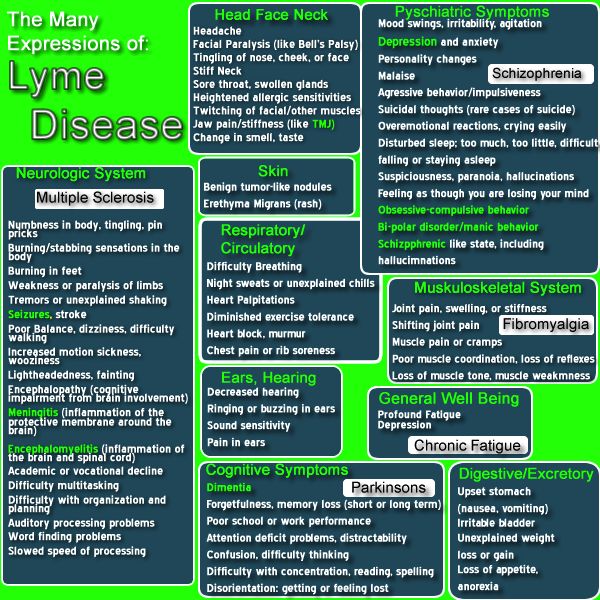

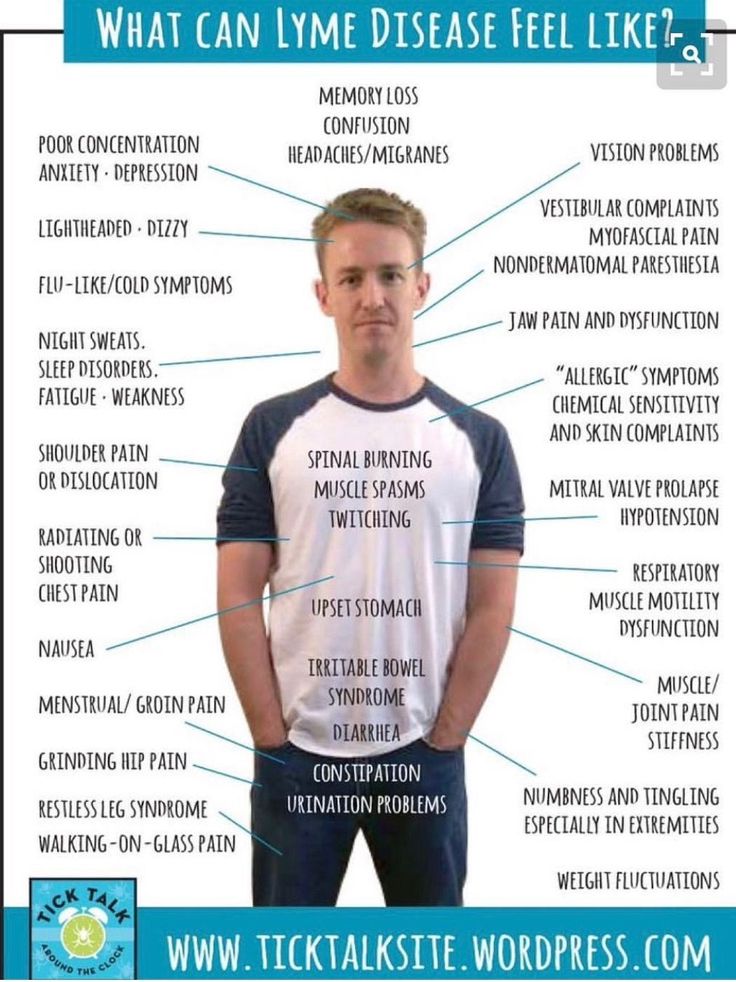

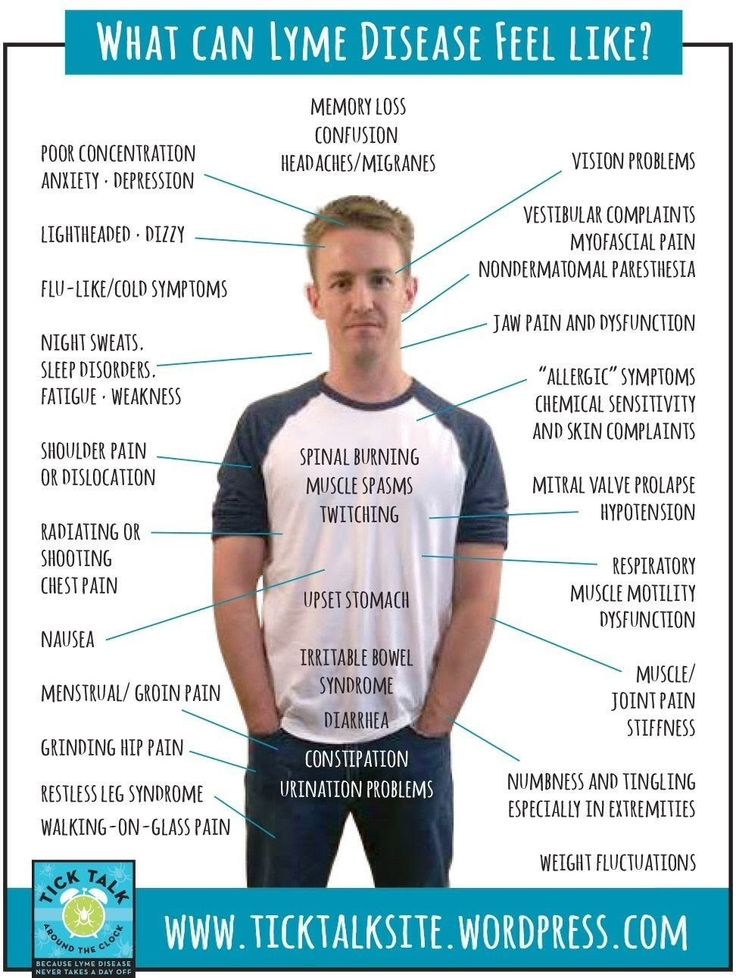

Mood disorders and mental illness are common manifestations of Lyme disease and other tick-borne infections. In acute Lyme disease, cognitive impairment (what most refer to as brain fog) is a common symptom. However, when tick-borne infections go undiagnosed for a long period of time, people can experience a range of neuropsychiatric symptoms. Lyme disease can cause anxiety, panic attacks, depression, bipolar disorder, developmental disorders, autism, schizophrenia, PTSD, addiction, insomnia, cognitive impairment, dementia, violence, and even suicide.

There are over 400 peer-reviewed articles discussing the association between Lyme disease and neuropsychiatric symptoms. The biggest challenge for people suffering from mood disorders is most mental health practitioners are not trained to look for the underlying cause(s) of the symptoms – including Lyme disease. Many people end up on mood-stabilizing medication for years – or a lifetime – without a known cause of their symptoms. In some with Lyme disease, mood symptoms may improve on psychotropic medication, but symptoms often relapse.

If a mood disorder is caused by Lyme disease or an associated infection, it may present as “atypical.” This is because the symptoms do not have the usual characteristics of the mood disorder while also having additional symptoms such as fatigue, joint pain, or headaches.

What Causes Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Lyme Disease?

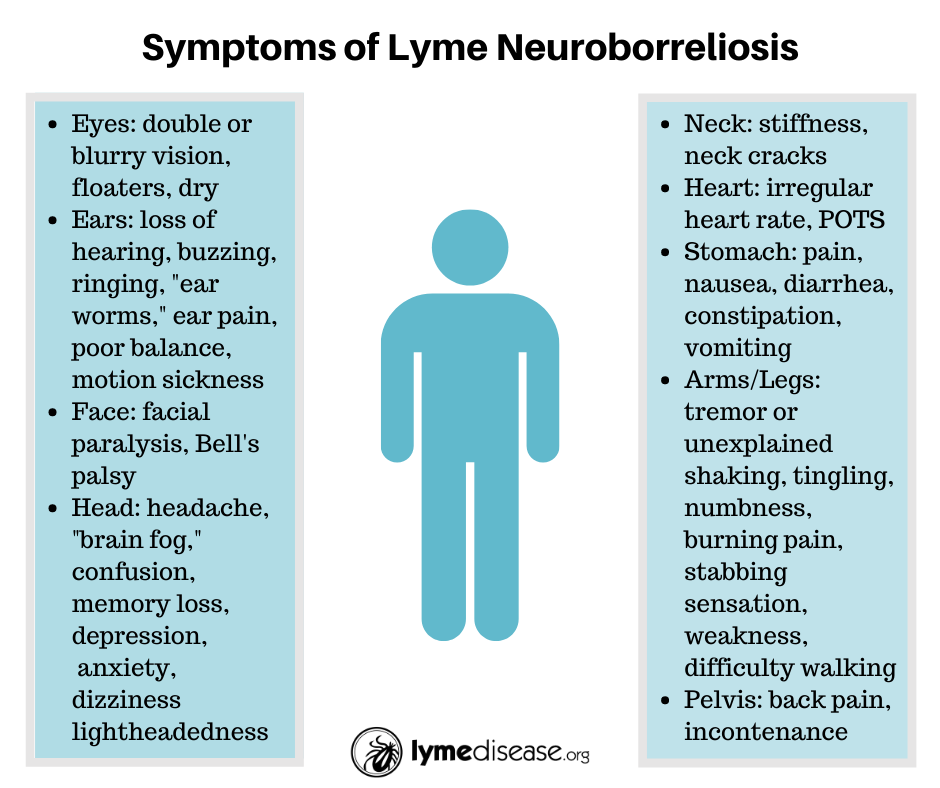

In tick-borne infections, it is believed damage to the nervous system can occur in three ways leading to neuropsychiatric symptoms. In the vascular form, tissue death in the brain can take place. In addition, infection with Borrelia within the central nervous system can lead to atrophy and encephalitis of the brain. The third type of damage happens outside of the central nervous system and causes an inflammatory response that affects the central nervous system.

Like many systemic symptoms associated with Lyme disease, neuropsychiatric symptoms can be caused by the immune response sparking inflammation.

The persistent immune response – even after the pathogen has been eliminated – includes inflammatory cytokines and autoimmune processes. Lyme bacteria has been shown to trigger antibodies to neuronal tissue leading to neurodegeneration.

Metabolic changes can also be induced by Lyme infections. The mitochondria in the central nervous system can become damaged from oxidative stress associated with tick-borne infections. Mitochondrial dysfunction leads to cognitive issues and fatigue. Inflammatory cytokines also cause an increase in quinolinic acid, a metabolite that contributes to neurotoxicity. People infected with Lyme borreliosis have increased levels of quinolinic acid in their central nervous system contributing to depression and poor cognition.

Imaging studies in people with Lyme disease often demonstrate pathophysiological changes of the brain that are not typically seen in depression. SPECT scans will illustrate decreased blood flow to the frontal and temporal lobes in Lyme disease. Swelling and atrophy in different regions of the brain can be seen on NeuroQuant MRI, which is consistent with an infectious or inflammatory cause of a mood disorder.

SPECT scans will illustrate decreased blood flow to the frontal and temporal lobes in Lyme disease. Swelling and atrophy in different regions of the brain can be seen on NeuroQuant MRI, which is consistent with an infectious or inflammatory cause of a mood disorder.

Lyme Disease and Depression

When properly treated following an acute infection with Lyme disease, depression rarely manifests.

In patients who are not properly diagnosed or effectively treated and end up with late-stage Lyme disease, depression is common. People suffering from depression caused by tick-borne infections will also often experience other symptoms such as fatigue, headaches, and/or joint pain. These additional symptoms are a good indication there may be a systemic illness causing the depression.

Since it can take years for a proper diagnosis of late-stage Lyme disease, it is common for people suffering from depression to be prescribed antidepressants. They often have to try multiple antidepressants because their depression was not alleviated by the initial medications. It may be important to remain on an antidepressant even after a diagnosis of Lyme disease is made to help stabilize one’s mood. Typically after effective treatment of late-stage Lyme disease, people are able to wean off of their psychotropic medications.

It may be important to remain on an antidepressant even after a diagnosis of Lyme disease is made to help stabilize one’s mood. Typically after effective treatment of late-stage Lyme disease, people are able to wean off of their psychotropic medications.

Major depressive disorder can be associated with underlying medical conditions such as tick-borne infections. Symptoms of major depressive disorder may include depressed mood, irritability, mood swings, insomnia, fatigue, poor concentration, and cognitive issues.

In addition to the physiological changes that occur in Lyme disease, being sick with a chronic illness can cause depression from not being able to perform daily activities, enjoy hobbies, engage in relationships, or from living with the uncertainty of a chronic medical condition.

Aaron suffered from panic attacks, depression, and insomnia. He was referred to me by his psychiatrist to be evaluated for tick-borne infections because the presentation of his symptoms were atypical. Aaron also complained of migraines, fatigue, and difficulty concentrating. He had not been in school for over a year because his symptoms made it too difficult to attend.

Aaron also complained of migraines, fatigue, and difficulty concentrating. He had not been in school for over a year because his symptoms made it too difficult to attend.

I ran a complete panel for tick-borne infections, a comprehensive workup for mold exposure, and other general laboratory tests I order in chronic illness. Surprisingly, Aaron’s tests indicated he had bartonellosis, Lyme disease, past mold exposure, and hypothyroidism. I put him on an antimicrobial regimen, liothyronine for his low T3, and a detoxification protocol for mold.

Within a couple of months, Aaron was more engaged with his family and had the energy to begin home studies. After a few more months of treatment, he felt well enough to attend his senior year of high school. He was also able to wean off of two of his three psychotropic medications. His parents were thrilled to know Aaron’s anxiety, depression, and insomnia were not something he had to live with for the rest of his life.

Lyme Disease and Anxiety

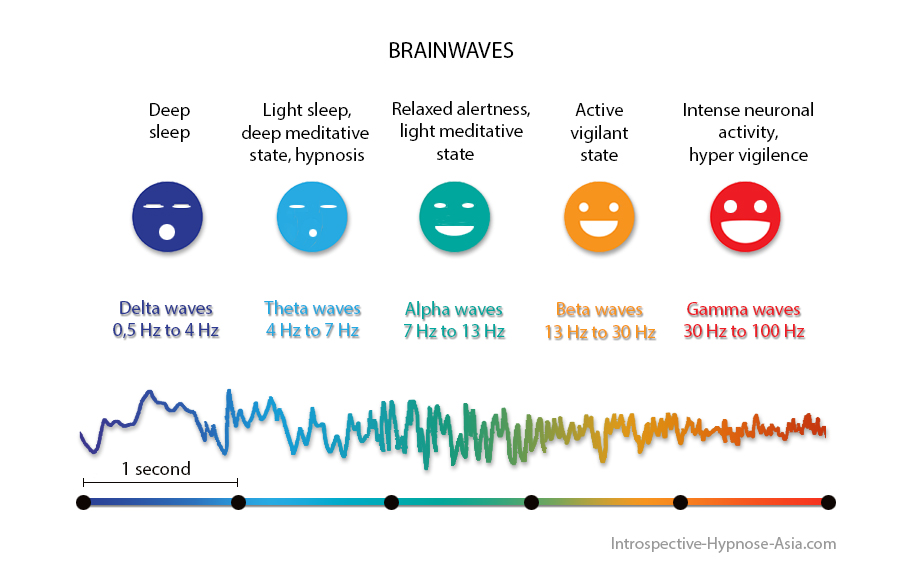

Anxiety, like depression, is a common psychiatric symptom that can be associated with Lyme disease. Like other neuropsychiatric symptoms, anxiety is triggered by inflammation and the metabolic changes that occur in tick-borne infections. Concern about one’s health – especially if causes have not been identified – can also contribute to anxiety or panic disorders. Different types of anxiety can present in Lyme disease. These include hypervigilance, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Like other neuropsychiatric symptoms, anxiety is triggered by inflammation and the metabolic changes that occur in tick-borne infections. Concern about one’s health – especially if causes have not been identified – can also contribute to anxiety or panic disorders. Different types of anxiety can present in Lyme disease. These include hypervigilance, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Of the tickborne co-infections, bartonellosis tends to cause an increase in anxiety. Bartonellosis requires a different treatment than Lyme disease, so it is important to test for all co-infections. I have seen generalized anxiety disorder and panic attacks resolve when patients are properly treated for Lyme disease and co-infections.

Of the associated tick-borne infections,

Bartonella tends to contribute to anxiety more than the others.Bartonellosis requires a different treatment than Lyme disease, so it is important to properly test for all co-infections. I have seen generalized anxiety disorder and panic attacks resolve when patients are properly treated for Lyme disease and co-infections.

I have seen generalized anxiety disorder and panic attacks resolve when patients are properly treated for Lyme disease and co-infections.

Other Mood Disorders Associated with Lyme Disease

There are multiple neuropsychiatric conditions that have been associated with Lyme disease and other tick-borne infections. Some of these associations have been researched in controlled studies and published in medical journals, while others come from case reports or presentations at medical conferences by physicians who have treated thousands of patients with mood disorders.

Bipolar disorder has been associated with multiple infections, including Lyme disease.

People with bipolar disorder caused by Lyme disease tend to be rapid cyclers. In reports and studies, the incidence of bipolar occurred in 10%-28% of people with Lyme disease.

There have been at least 23 infections identified as one of the causes of autism.

Seven of these infections were tick-borne infections. Oftentimes other environmental and genetic factors play a role in the onset of autism spectrum disorder. Like other neuropsychiatric disorders mentioned previously, it is the immune response to the infection that results in inflammation that contributes to the symptoms. In one study of children diagnosed with autism and Lyme disease, 94% had previously tested negative for Lyme disease with the standard two-tiered CDC testing criteria.

Oftentimes other environmental and genetic factors play a role in the onset of autism spectrum disorder. Like other neuropsychiatric disorders mentioned previously, it is the immune response to the infection that results in inflammation that contributes to the symptoms. In one study of children diagnosed with autism and Lyme disease, 94% had previously tested negative for Lyme disease with the standard two-tiered CDC testing criteria.

Substance abuse and addiction can become part of someone’s life if they are suffering from chronic tick-borne infections.

This is especially true if the infections have been undiagnosed for a long period of time. I see this abuse or addiction most often in teenagers and young adults. This population may be suffering from fatigue, chronic pain, headaches, and anxiety or depression, and without a diagnosis, they turn to alcohol and/or recreational or prescription drugs to cope with the symptoms. Adults can also become addicted to pain medication. One report indicated substance abuse can range from 10%-33% of people with Lyme disease.

One report indicated substance abuse can range from 10%-33% of people with Lyme disease.

Schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder are less common in people with Lyme disease.

However, in late-stage Lyme, paranoid symptoms occurred in 36% of patients. There was a slightly higher prevalence of hallucinations in people with Lyme disease in another report.

Psychiatrist Robert Bransfield has written about the association of Lyme disease and suicide.

Some individuals have been suffering from late-stage Lyme disease for an extended period of time. Whether or not they are being treated for the disease, some begin to lose hope they will ever get better. Most of the time, people are also suffering from anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, or cognitive issues so their actions may be impulsive and unpredictable.

What Can Be Done About Neuropsychiatric Illness and Lyme Disease?

When someone is suffering from a mood or psychiatric disorder and the person is also experiencing additional symptoms such as fatigue, headaches, joint pain, insomnia, and cognitive issues, an underlying cause such as an infection should be ruled out. Other clues that there may be an infectious cause to psychiatric symptoms include having an “atypical” presentation of the diagnosis and not responding to common medications used to treat the mood disorder. Also, is there a possibility the person could have been exposed to ticks or other known vectors? Anyone who spends time outdoors, either where they live or vacation, or has pets that are indoor/outdoor is at risk for exposure to ticks.

Other clues that there may be an infectious cause to psychiatric symptoms include having an “atypical” presentation of the diagnosis and not responding to common medications used to treat the mood disorder. Also, is there a possibility the person could have been exposed to ticks or other known vectors? Anyone who spends time outdoors, either where they live or vacation, or has pets that are indoor/outdoor is at risk for exposure to ticks.

If a tick-borne infection is the cause of a mood disorder, addressing the infection(s) can improve the mental symptoms. Those already on psychotropic medication may need to stay on the medication while the underlying cause(s) are treated. Immune and detoxification support to reduce inflammation is also effective at improving mental health.

Taking a comprehensive approach to identify and treat any underlying causes of psychiatric illness, especially in those with a multi-systemic and multi-symptomatic presentation. There is increased hope and improved outcomes for those suffering from what is otherwise a life-long disorder. Lyme disease and other tick-borne infections are more common than previously recognized and have a high likelihood of contributing to neuropsychiatric conditions.

There is increased hope and improved outcomes for those suffering from what is otherwise a life-long disorder. Lyme disease and other tick-borne infections are more common than previously recognized and have a high likelihood of contributing to neuropsychiatric conditions.

Share This Post

- Share on Twitter Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn Share on LinkedIn

- Share via Email Share via Email

Related Articles

how people who voluntarily returned to the Stone Age live

Such preppers appeared many years ago, but over the years they become less and less: life in the bosom of nature turned out to be not as harmless as they thought.

"A new life in the wild" - this is how 56-year-old native of Britain Lynx Wilden (that is, Wild Lynx) calls the idea of her strange existence. It has united around itself many Europeans who, for the sake of preserving the environment, are voluntarily ready to return to the Stone Age and live like cavemen.

Lynx started teaching her "doctrine" many years ago. Back in the mid-2010s, she lived for half a year in Washington, where she actively met with people and explained to them the need to abandon the benefits of civilization and return to the bosom of nature. For the remaining six months, the woman disappeared, going somewhere in a forest or mountainous area. There she taught her followers the art of survival.

With a small inheritance inherited from her mother, she bought a five-acre plot of land in Norway so that no one would annoy her or all her honest company. Now the woman lives there in a yurt, where a small stove is installed, running water and electricity are installed, and there is also a computer with an Internet connection. Lynx admits that since she could afford to live in savage conditions, a lot of time has passed and "something has changed." Now she is no longer able to huddle in caves and dugouts.

Ben Fogle and Lynx She told renowned British journalist Ben Fogle that she still hopes to inspire people's hearts to protect nature from the burden of anthropogenic pollution, and she still manages to convince some people to "go to the forests", but there are fewer of them, especially since the Wild Lynx itself has ceased to be so wild.

The woman hopes to create a community called Lithica, bringing together people who are ready to abandon the modern way of life, return to the Stone Age and learn to unite with nature. But such escapades became too heavy for her. The fact is that somewhere in her wanderings (and Lynx actively traveled around Europe for several years and, in particular, wandered around France a lot), she picked up Lyme disease. “I was bitten by ticks hundreds of times, and this was probably to be expected,” Lynx spreads his arms.

She needs a computer and the Internet to solve psychological problems. In some embarrassment, she admitted that living alone in the long winter months, for a long time without seeing a single soul, was becoming more and more unbearable for her. Therefore, online communication partly replaces her meetings with people she is deprived of, and does not allow her to finally slide into depression. “I had to make that compromise,” says Lynks.

Lynx and Ben Fogle in the mid-2010s “I am not a simple person, I have had a desire to change places for a long time. Apparently, my ancient ancestors were nomads, and their blood still drives me to wander. Of course, such an existence cannot be peaceful. I have either a calm or a storm. Lyme disease, for example, is a violent storm,” says the woman.

Lyme disease is a tick-borne borreliosis, a tick-borne infection that can be transmitted to humans by a bite and is the most common disease transmitted in this way. Borrelia bacteria enter the bloodstream causing fever, headaches, fatigue, and a skin rash called erythema migrans (which looks like a pale ring on reddened skin that gradually expands).

In some genetically predisposed people, Lyme disease quickly affects the joints, heart, nervous system, and eyes. In most cases, it can be cured with antibiotics, but the outcome depends on the stage at which the diagnosis was made and therapy started. If borreliosis has gone far and was caught already at a late stage, it is considered intractable and often leads to disability or even death.

Tick-borne borreliosis (Lyme disease) is a common story among "savages" Even after treatment, many patients continue to suffer from some of the symptoms of the disease, leading to the theory of the existence of chronic Lyme disease (persistent infection with Borrelia burgdorferi). The World Health Organization (WHO) does not recognize it as an independent disease, but thousands of doctors around the world make such a diagnosis unofficially.

Chronic Lyme disease is manifested by subjective symptoms - constant fatigue and increased fatigue, muscle and headaches, difficulty concentrating, periodic aching joints. Doctors who believe in the existence of this disease prescribe long courses of antibiotics in large doses to their patients. However, it is officially accepted that Borrelia burgdorferi is either an untreated "classic" tick-borne borreliosis in a late stage, or the neurological consequences of a severely endured borreliosis that require rehabilitation.

“I got infected from ticks, too many ticks bit me in France, I got hundreds of bites a year, and finally my body couldn't handle the bacterial load,” Lynx explained. Now she is experiencing all the "charms" of the condition, which is called chronic Lyme disease, so living in the bosom of nature has become almost unbearable for her.

Now the woman wants to engage in education and propaganda of her former lifestyle. “Although I myself can no longer roam the forests and caves, I can teach this to many other people who are ready to take care of nature and refuse to pollute it with the “benefits” of modern civilization,” says Lynks.

In the summer, she is going to organize courses for all comers on her plot of land, where she intends to educate volunteers about the harm caused to nature by humans, and conduct a master class on survival in the wild. “Everyone will be able to find their true wild “I”, which sits inside each of us. You have to start small, because big dreams start small, ”the woman rants.

Lynx taught her followers how to hunt with bows and arrows for years Now there are three men and a lady named Tessa, who came there from The Hague because she was looking for "such a place" for a long time. She, however, is more interested in the external attributes of "rewilding" (as the movement of "returnees" in prehistoric times is called) such as homemade clothes, than in conceptual things. “Unfortunately, they are the majority,” Lynx sighs, not losing hope of attracting new followers with the advent of warmth.

Ekaterina Kotova

Lyme disease - treatment, symptoms, causes, diagnosis

Lyme disease is a bacterial infection affecting all organs and systems caused by the spirochete borrelia burgdorferi. The microorganism was named after Willy Burgdorfer, a researcher of this disease, and the town of Lyme in the United States. Studies have shown that this infection has existed in the US for at least 100 years. The natural focus of infection is wild animals, in whose body this bacterium persists and is transmitted to other animals with tick bites. Humans and pets become infected with this bacterium through accidental bites. Unfortunately, a strong immunity to this infection does not develop, and it is possible to re-infect with accidental tick bites. Lyme disease is transmitted through the bite of a tick.

Ticks develop through four life stages: egg, larva, nymph, and adult. The transition from one stage to another is accompanied by a molting process that requires building material (blood). When a tick bites an animal infected with a microbe, it becomes infected, and the infection persists in the tick's body throughout the entire life cycle of the insect. But an adult tick does not transmit the infection to the next generations. Transmitters of infection in the USA are ticks from the Ixodes family (Ixodes pacificis, Ixodes scapularis, Ixodes dammini, etc.).

Other types of ticks play a minor role in the existence of natural foci of borreliosis, since recirculation between animals does not include humans. For example, we are talking about wood rat mites (Ixodes neotomae) and rabbit mites (Haemaphysalis leporispalustris), in which Lyme disease bacteria may be present, but they are not transmitted to humans. This is explained by the fact that ticks feed only on the blood of these animals.

In other parts of the world, other ticks are involved in the transmission of borreliosis (in Europe it is the sheep tick (Ixodes ricinus), and in Asia the taiga tick (Ixodes persculcatus). These ticks are found everywhere (in the forest, on the seashore and even in courtyards of residential buildings)

While a tick can bite at any time of the year, the peak season for tick bites is April-September. Ticks can survive in a variety of weather conditions as long as there is adequate moisture

Symptoms of Lyme disease.

The early symptoms of Lyme disease are similar to those of the flu: headache, fever, muscle pain, fatigue, stiff neck. Approximately 60% of fair-skinned patients develop a characteristic rash called erythema migrans (usually a few days after a tick bite). In patients with dark skin, these rashes look like a bruise.

The rash may appear within a day of the bite or a month later. This rash may look like a half-inch red spot raised above the skin surface in the form of a ring (normally colored skin in the center). But sometimes the rash can be large and occupy, for example, the entire back. It is necessary to distinguish small rashes from other possible skin lesions. As a rule, local skin damage is a reaction to trauma and usually disappears after a few days without causing general symptoms.

Symptoms of dissemination of infection.

Often the patient does not notice the first signs of the disease, and there comes a period of involvement of internal organs in the infectious process. But the symptoms of dissemination are not specific to Lyme disease and are seen in other diseases as well.

General symptoms

General weakness, severe headache, fever severe muscle pain.

CNS symptoms

Signs of nerve conduction disorders (weakness / paresis in the limbs, loss of reflexes, sensory disturbances, peripheral neuropathy), severe headaches, neck stiffness, meningitis, disorders of the cranial nerves ( for example, smell/taste changes Difficulty chewing, swallowing, or speaking Dysphonia or problems in the vocal cords Bell's palsy Facial palsy Dizziness/fainting Shoulders droop Inability to turn the head Light or sound sensitivity. hearing changes are also possible, deviation of the eyeball, ptosis of the eyelid, stroke, sleep disturbances, intellectual-mnestic disorders (impaired fixation memory, concentration of attention, performing simple arithmetic actions), behavioral disorders (depression, personality change).0003

In addition, other mental changes are described in the literature: anxiety attacks, disorientation, hallucinations, paranoia, and other schizophrenia-like changes.

Eyes

Visual impairment, including blindness, retinal damage, optic nerve atrophy, eye redness, conjunctivitis, "spots" before the eyes, inflammation of various parts of the eye, pain, diplopia.

Skin

Eruption not on side of bite. Skin rashes vary in both shape and color, usually ring-shaped, and can range in color from red to purple. The rashes may be hot to the touch or itchy or hard to the touch. In addition, other skin manifestations are possible:

- Lyphocytoma, which is a benign nodule or tumor, and

- acrodermatitis chronic atrophicus, which is usually discoloration/degeneration of the skin of the hands or feet.

Cardiovascular system

Cardiac arrhythmias, conduction disturbances in the myocardium, myocarditis, pain in the heart area, vasculitis.

Joints

Arthritis in Lyme disease is manifested by pain, both transient and persistent. Joint lesions are usually not symmetrical, sometimes there are swelling in the joints..

Liver

Moderate liver dysfunction.

Light . Respiratory disorders sometimes pneumonia.

Muscles. Pain in the muscles, inflammation, decreased tone.

Gastrointestinal tract bowel dysfunction (diarrhea), appetite disorders, anorexia

Influence on pregnancy

Spontaneous abortion, premature birth, stillbirth are possible with Lyme disease. In addition, cases of congenital Lyme disease have been described. In such cases, the bacteria may pass from the mother to the fetus through the placenta. In addition, it is not excluded that the infection can be transmitted through breast milk.

Diagnosis

Unfortunately, there are no tests that reliably confirm that the patient is currently infected with borreliosis bacteria and then confirm the absence of bacteria (the small size of spirochetes and the number does not allow you to see these bacteria in a living organism). The diagnosis is exposed on the basis of symptoms of a clinical picture and an epidemiological history.

Laboratory diagnostic methods

Indirect tests (antibody tests )

Antibodies are proteins produced by immune cells to bind infectious agents and neutralize microorganisms. Both the general level of antibodies in the blood and specific antibodies to the bacterium that causes Lyme disease are determined. False negative tests may be due to too low levels of antibodies to spirochetes, the presence of a small number of freely circulating spirochetes and, therefore, a low level of immune response (use of antibiotics, mutation of spirochetes). False-positive tests may be in other diseases (eg, syphilis, periodontal disease, rheumatoid arthritis). Types of Tests (antibody titer, Western blotting, antibodies to Lyme C6 peptide).

- Antigen detection - These tests detect a unique Bb protein in the fluid (eg urine) of patients. This may be useful for diagnosing Lyme disease in patients taking antibiotics or during a sudden flare-up.

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) - This assay enhances the detection of the Bb protein.

- Cultivation - Growing bacteria in media is labor intensive and time consuming (sometimes taking months).

Biopsy and microscopy are not very successful due to the fact that there are not many circulating spirochetes in the blood. Therefore, at present there are no clear protocols for the treatment of this disease. Antibiotics are only effective in the early stages of Lyme disease. When internal organs are involved in the infectious process, antibiotic treatment should be long-term and in sufficient dosage.