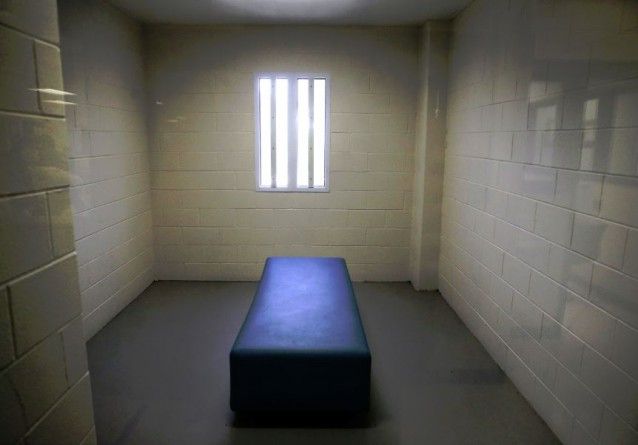

Locked psychiatric facility

I work in a locked psychiatric ward. These days, you do too

First Opinion

By Abraham NussbaumDec. 23, 2021

Reprints

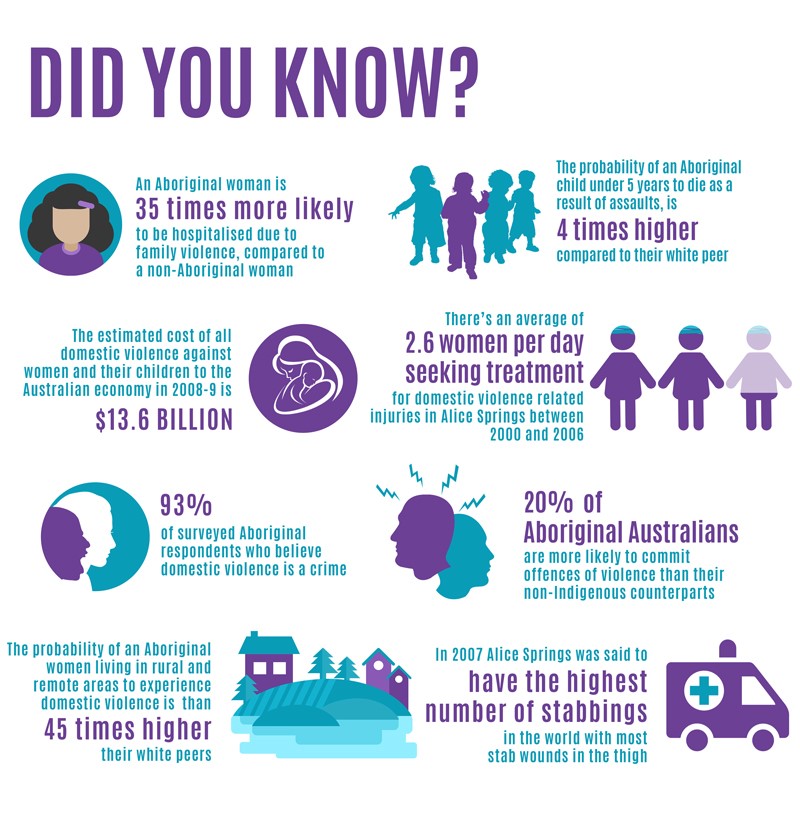

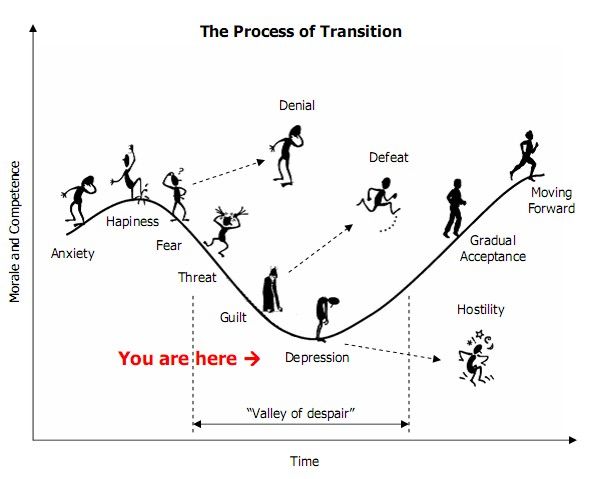

AdobeAt parties, I used to explain to people who wanted to know what I do — I’m a psychiatrist — that caring for people with mental illness on a psych ward is like working in a place apart from the world. I don’t say that anymore. These days, the whole world feels like the psych ward. Everyone is discouraged by past harms and present fears. The people who need meds the most are the most reluctant to take them. Most everyone wants out, but many worry they will never leave, and everyone wonders how things will be on the other side.

And I certainly won’t be saying that at holiday parties this year, since I am quarantining with a breakthrough infection. Even if I was out of quarantine, most parties have been cancelled here in Colorado, where I live and work, because the state is entering its third wave of the pandemic.

The state has fully vaccinated 69% of eligible people, but the hospitals are full, the Federal Emergency Management Agency is helping staff them, and the governor is enacting crisis standards of care.

In some ways, it’s the worst wave so far. In the first one, clinicians were galvanized. In the second, we knew the vaccine was coming. In this wave, we are short-staffed and short-tempered, exhausted by people threatening us for doing our best and threatening everyone’s health by declining vaccination.

advertisement

It turns out that living with an endemic virus isn’t so different from being locked up on a psychiatric ward, and that if you want to get out of a restricted space you have to learn how to use confinement.

Psych wards are places where it’s hard to know when you can leave. When you ask when you will be discharged, my colleagues and I always answer, “When you no longer need to be here.” It’s a conditional answer that frustrates almost all recipients, even if it’s true. The evidence-based guidelines are just as conditional, recommending that you stay until the risk factors for acute danger are addressed.

The evidence-based guidelines are just as conditional, recommending that you stay until the risk factors for acute danger are addressed.

advertisement

In the pandemic, here we are, together, waiting out danger.

Psych wards are places that don’t have basic supplies. The nurses will take your shoelaces because you could use them to tie or bind yourself as an act of self-harm or suicide. It’s the same reason why there are neither knobs on the doors nor hooks on the walls. Hand sanitizer dispensers are often disabled because patients have been found crouching underneath them, triggering their motion sensors again and again so they can drink the measured doses for their scant alcohol content. (No matter what country songs say, hand sanitizer shots on the psych unit are the most desperate of drinks.) So you improvise, figuring out to how hold shoes together, open doors, and wash hands with what you have.

In the pandemic, amid widespread supply chain woes, we are all learning to improvise with what we have. Some real innovation will result from this forced improvisation.

Some real innovation will result from this forced improvisation.

Psych wards are institutional spaces that prioritize safety. The lights are always too bright. Someone is always monitoring your behavior. Safety trumps comfort — but there’s a reason for that: Even though people with mental illness are more likely to be the victims of violence rather than perpetrators of it, psych wards preselect for people experiencing thoughts of harming others. The Bureau of Labor Statistics says that while the average hospital worker is six times more likely to be intentionally injured at work than the average American worker, the average psychiatric hospital worker is 59 times more likely. Because intentional injury to workers is so common, when your illness starts to threaten the staff or the other patients, you will be asked to keep to yourself or take medications.

The next time those statistics are assessed, I suspect intentional injuries will rise across health care because so many nurses, physicians, and public health officials have been threatened and assaulted.

In the pandemic, when my health care worker colleagues and I talk about the necessity of masks and vaccines to ward off Covid infections for your family and for us, we are talking about similarly temporary restraints on liberty in pursuit of life-saving safety for you and us.

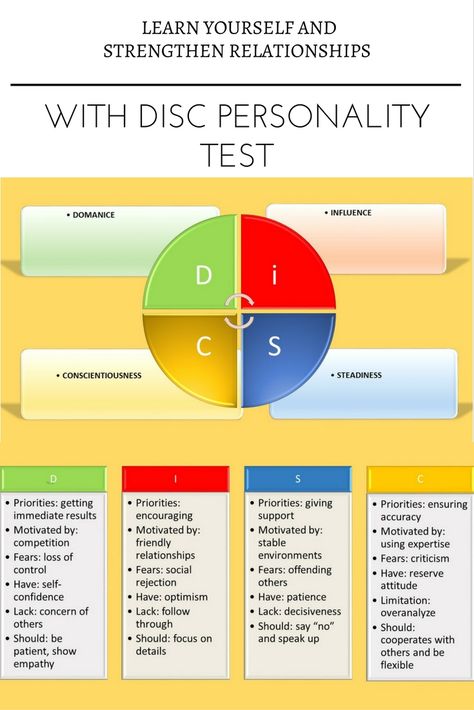

Psych wards work only when they are staffed by skilled nurses who help by being present. On every bad ward I have visited, the nurses were absent in one fashion or another. There were too few of them, or they didn’t have time for the patients, or they relied on policies instead of presence. The worst nurses had failed their way off medical and surgical wards and ended up in psych wards. On every good psych ward I have seen, the nurses chose to work there as a reactive act of altruism after a personal or familiar experience with the ravages of mental illness. They said consoling words, like “I cannot imagine what you are going through, but I’ll be here for you.”

Good nurses talk, sing, and problem solve patients out of difficult places. Unlike the unit’s televisions, which enrage or pacify, a good nurse can see and understand you. The good nurses align with you, not with your interpretation of events, by endorsing you, not your anger, helplessness, or paranoia. They recognize your emotions, but without sharing them.

Unlike the unit’s televisions, which enrage or pacify, a good nurse can see and understand you. The good nurses align with you, not with your interpretation of events, by endorsing you, not your anger, helplessness, or paranoia. They recognize your emotions, but without sharing them.

Doctors like me come and go, making our rounds and then leaving. Nurses remain, day and night. At least they did.

In the pandemic, psych and other wards are short nurses more than ever before, with nurses being a significant part of the reduction of the American health care workforce by 450,000 people since the pandemic began. And while medications help, nothing is better than a good nurse, so we need to figure out how to get nurses back to the bedside.

Psych wards are places where people say all kinds of things, because these units welcome all comers. I often find myself jotting down a powerful phrase, a striking sentence, or, in the case of a person with mania, a performative paragraph. Listening to them all, I am struck by how people with mental illness can magnify a cultural moment. Sometimes they distort it, but they often hear the messages rightly.

Listening to them all, I am struck by how people with mental illness can magnify a cultural moment. Sometimes they distort it, but they often hear the messages rightly.

Psych wards have tables in the dayroom where a person can say something strange or provocative, giving voice to previously unvoiced thoughts, and they can do so safely — if the unit provides enough structure.

In the pandemic, we don’t have a shared dayroom with the right structure to remind us of our shared vulnerability. The place where we now commonly meet people different from us — social media — is designed to profit off our differences. To survive the pandemic, we need more in-person places where we can encounter people from different tribes.

Psych wards are places where people don’t experience you as yourself. No one ever does, of course, projecting past experiences to their present encounter with you. But on a psych ward it feels acute. You are likely to be experiencing negative emotions such as anxiety, discouragement, and uncertainty, rather than any kind of emotional equanimity. Reacting emotionally, a patient can experience a doctor or nurse or other health care worker as a lover, a jailer, and an alien — all in the same conversation.

Reacting emotionally, a patient can experience a doctor or nurse or other health care worker as a lover, a jailer, and an alien — all in the same conversation.

When working on a ward, I listen to what a patient says, but also how and to whom. Are they talking to me or their unforgivable mother, their irresistible ex, or their hostile neighbor? When I listen to someone, I learn to ask myself, “Who is this person really addressing? How can I work with them so they will experience me more as myself rather than all that they are projecting upon me?”

In the pandemic, social distancing deepened social polarization. To defeat the virus, we need physical distancing, but the kind of social connections where people encounter each other as something closer to themselves.

Psych wards work best as immediate responses to acute emergencies, not regular responses to chronic problems. A few years ago, several colleagues and I examined the data on who benefits from being on a psych ward and found that hospitalization most benefited people with acute illnesses. The ward serves as a kind of temporary environment that prevents someone from making an irreversible error, like a fatal withdrawal from substances or a final overdose or suicidal act. What psych wards are least helpful for is helping people who have been in one many times before, because they are often the individuals who are refractory to the available treatments.

The ward serves as a kind of temporary environment that prevents someone from making an irreversible error, like a fatal withdrawal from substances or a final overdose or suicidal act. What psych wards are least helpful for is helping people who have been in one many times before, because they are often the individuals who are refractory to the available treatments.

In systematic reviews, the best predictor of rehospitalization is previous hospitalization. A psych ward may feel good if you have an acute problem and are grateful to have a group of professionals rallying around you. It’s likely to feel terrible if you have chronic mental health problems, because you know the limits of treatment and have little confidence that this time will be different.

In the pandemic, the first wave of quarantine felt like bracing medicine but it was probably too late and too short, allowing the virus to become endemic. Later stages, with half-measures of masking and mandates and shifting rules and regulations to address a chronic reservoir, feel confusing and confining, like a hospitalization without an apparent discharge.

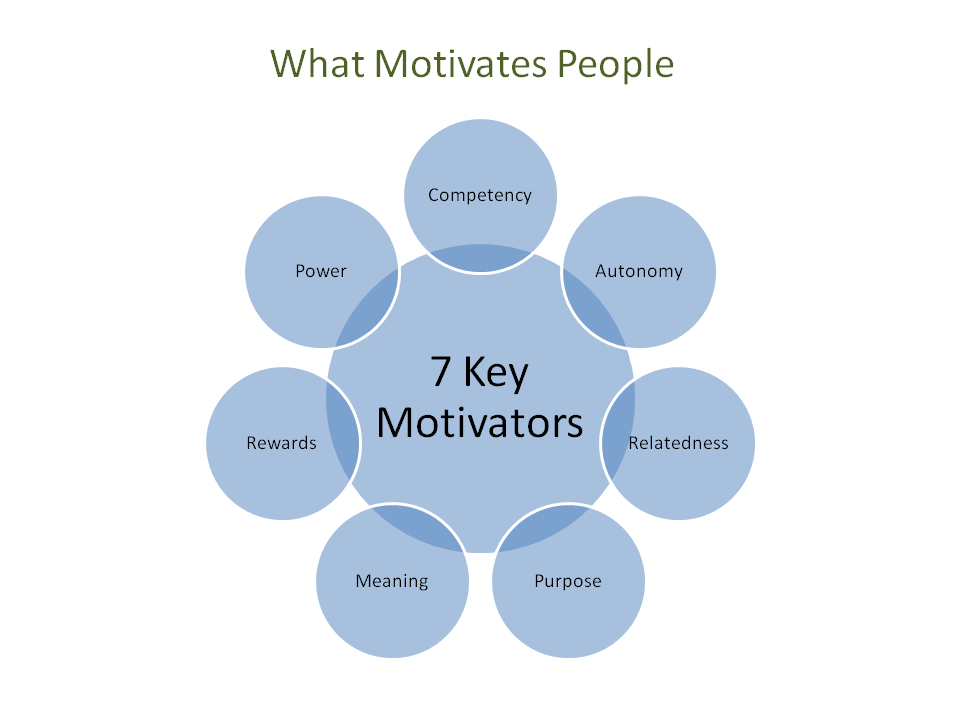

Psych wards are designed to motivate change. I am fond of the old joke: “How many psychiatrists does it take to change a lightbulb? One, but the lightbulb has to want to change.” Psychiatrists are most helpful to people ready for change — and few things motivate change like being hospitalized on a locked psych ward. I ask every patient “What changes would you like to make in your life?” Some patients readily identify changes, while others deny that any changes are necessary. Psych wards are architecture against ambivalence. Ambivalence resolves under the realization that you, yes you, are spending the night here and you can’t leave. Whatever vulnerabilities and habits have brought you to this point, it is time to change them.

In the pandemic, we are coming to realize — belatedly — that humans have lived with viruses and will always live with them. It is only those viruses that exploit human vulnerabilities and habits that induce pandemics. That is why pandemics are, historically, a time of great change. Any real change will feel uncomfortable, leaving some to fear that they are not ready, but we need to accept change so we can walk out.

Any real change will feel uncomfortable, leaving some to fear that they are not ready, but we need to accept change so we can walk out.

Here’s the last parallel I’ll share: Psych wards should be put out of business. They are confining and uncomfortable. I wish we did not need them, but I work in them because they are necessary until something better exists. When I discharge patients, I remind them they can return if they need help, but share a hope they won’t need to. Together, we talk about the steps they can take to avoid rehospitalization. With the right patient, I share my wish that the culture wouldn’t need psych wards. I tell them, “Do what you can to put me out of business.”

It’s the same with the pandemic: Do whatever you can — getting vaccinated and rebuilding relationships are the best places to start — to put Covid-19 out of business.

Now, where’s that nurse so we can talk about other ways to get out of here?

Abraham M. Nussbaum is a psychiatrist, chief education officer at Denver Health, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, and author of “The Finest Traditions of My Calling: One Physician’s Search for the Renewal of Medicine” (Yale University Press, 2016).

About the Author Reprints

Create a display name to comment

This name will appear with your comment

The locked inpatient psychiatry unit: What's it really like?

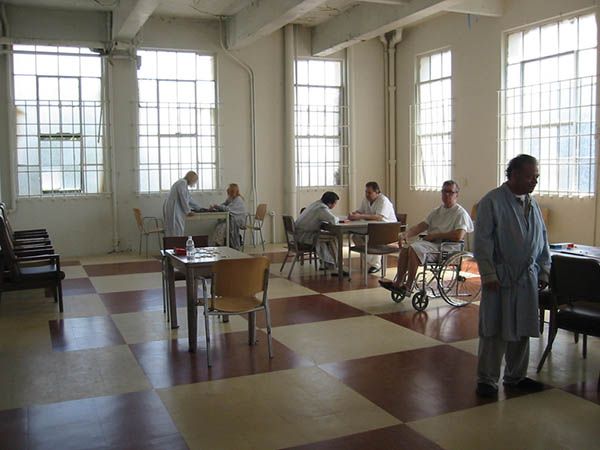

As I walk onto any one of the locked psychiatric units at our hospital I am immediately struck by the hum of intense activity. It’s like the startling feeling of stepping out of an air-conditioned apartment into the steamy height of a New Haven summer. Across from the nurses’ station, a psychologist interviews a patient retelling the story of constant childhood molestation as rivulets of mascara run down her cheeks. A confused nineteen-year-old man recently diagnosed with schizophrenia talks to an unseen critic telling him he should just “end it all.” In the heavily-fortified clinical station nurses enter vital signs, psychiatric technicians rapidly discuss overnight events and psychiatry resident physicians like myself collect all this data in order to present our patients’ clinical profiles on morning rounds.

While this bustling environment might suggest a power differential in which patients are at the mercy of their treatment providers, such an interpretation could not be further from the truth. The days of psychiatrists wantonly admitting patients against their will has been replaced with a legal procedure that firmly puts patients’ rights first. The question of whether a patient possesses “psychiatric disabilities and is dangerous to himself” is reexamined daily to ensure that the patient can be treated in the least restrictive environment possible. Just as the patient’s commitment criteria are constantly being reevaluated, long-term management strategies run alongside. Psychological and pharmacological therapies are used together to stabilize patients and transition them into outpatient treatment where their long term psychological needs can be met. Additionally, as many of our patients are in dire financial straits, housing and vocational opportunities are aggressively pursued by the treatment team’s social workers.

Perhaps you’re saying yourself, “This all sounds way too normal. Where are the screams? The shackles? And where, oh where, is ‘Nurse Ratched’?!” These are questions that have plagued the perception of psychiatric inpatient treatment since Ken Kesey’s seminal work One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and the classic movie adaptation. Certainly the screams occur. I wish I could say there weren’t situations in which patients need to be forcibly restrained. However, these events happen far less often than might be expected.

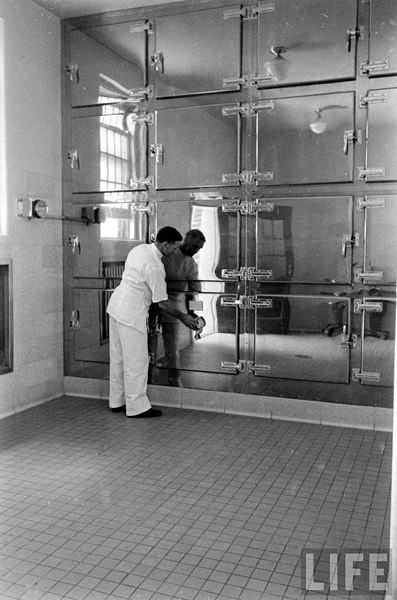

Just as our colleagues in surgery and emergency medicine note that fiction wildly dramatizes certain elements of their fields, inpatient psychiatry is also a victim of such inaccurate portrayal. In fact, much of inpatient psychiatric care involves a lot of routine work, like any other medical unit. We admit patients, treat them, and discharge them. That’s not to say incredible things don’t happen, of course. The reality of a locked inpatient ward is less outwardly dramatic than fiction but perhaps even more potent. True transformations occur during psychotherapy, medication management sessions, and art therapy classes. When a patient who has been kicked around his entire life finds an empathic ear, the click of connection is almost audible during a session. When just the right medication or psychological therapy falls into place, the heart and soul of inpatient psychiatry emerge. These moments don’t photograph well and similarly don’t move books or sell movie tickets. Pictures of cruelty sell better than the truth, unfortunately.

True transformations occur during psychotherapy, medication management sessions, and art therapy classes. When a patient who has been kicked around his entire life finds an empathic ear, the click of connection is almost audible during a session. When just the right medication or psychological therapy falls into place, the heart and soul of inpatient psychiatry emerge. These moments don’t photograph well and similarly don’t move books or sell movie tickets. Pictures of cruelty sell better than the truth, unfortunately.

Despite the well-worn image of the inpatient made into a zombie by mind-numbing agents, I’m pleased to say that our patients, on balance, do well. And they are doing better with every passing year. Emerging medications have made patients’ lives outside of the hospital less encumbered by severe side effects such as drooling and confusion that previously served to isolate and stigmatize. Long-acting forms of our medications have been developed to help patients who are unable to manage having to take pills on a consistent basis. While celebrity rapid-detoxes and costly boutique psychotherapy treatments seem to command widespread interest, I am more excited to hear everyday people tell me that they have been admitted to an inpatient unit during a crisis and our now able to return to the satisfactions of life and work while managing their illness through a combination of therapy and medications. Although images from Cuckoo’s Nest and the like persist in the minds of many, I think the future holds an intense change in perception of the inpatient psychiatric ward. As our government has now recognized the increasingly high cost of lost productivity due to mental illness, perhaps the average inpatient stay will increase, the funding for outpatient care will similarly climb, and patients will have a greater shot at wellness. Such an outcome may not make for a great movie but is high drama nonetheless.

While celebrity rapid-detoxes and costly boutique psychotherapy treatments seem to command widespread interest, I am more excited to hear everyday people tell me that they have been admitted to an inpatient unit during a crisis and our now able to return to the satisfactions of life and work while managing their illness through a combination of therapy and medications. Although images from Cuckoo’s Nest and the like persist in the minds of many, I think the future holds an intense change in perception of the inpatient psychiatric ward. As our government has now recognized the increasingly high cost of lost productivity due to mental illness, perhaps the average inpatient stay will increase, the funding for outpatient care will similarly climb, and patients will have a greater shot at wellness. Such an outcome may not make for a great movie but is high drama nonetheless.

Arjune Rama is a resident physician in psychiatry and can be reached on Twitter @arjunerama. This piece originally appeared in HUM Magazine.

This piece originally appeared in HUM Magazine.

Tagged as: Psychiatry

Founded in 2004 by Kevin Pho, MD, KevinMD.com is the web’s leading platform where physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, medical students, and patients share their insight and tell their stories.

CME Spotlights

From MedPage Today

Nizhny Novgorod Regional Psychoneurological Hospital No. 1

An appointment with a doctor is carried out by calling 8 (831) 466-71-33 and through the Regional Portal of Medical Services

State Budgetary Institution of Healthcare of the Nizhny Novgorod Region P.P. Kashchenko"

(GBUZ NO "NOPNB No. 1").

Address: 603152, Nizhny Novgorod, Kashchenko street, 12a

E-mail: [email protected]

ATTENTION! nine0013

Due to a technical failure, making an appointment by phone 466-71-33 is not possible. Please contact the hotline 8-991-793-30-03

In order to implement measures to prevent and reduce the risks of the spread of a new coronavirus infection ( COVID -19) 1" warns of strict adherence to the use of personal respiratory protection equipment when is in enclosed spaces. nine0016

nine0016

From March 26, 2020, the reception of visitors in all structural divisions is limited. Citizens can submit appeals, complaints, applications and other documents in the form of an electronic document, an email: [email protected], through postal organizations, by fax: 8(831)466-74-72. Also, during the opening hours of the institution, citizens, legal entities can contact the institution by phone: 8 (831) 466-71-33.

For questions about the condition of patients being treated at the State Budgetary Institution of Healthcare "NOPNB No. 1", contact the attending physicians at the indicated numbers from 14:00 to 16:00

(831)466-73-13 1 psychiatric department

(831)466-72-63 2 psychiatric department

(831)466-73-70 3 psychiatric department

(831)466-72-50 4 psychiatric department

(831)466-17-46 5 psychiatric department

(831)466-36-05 6 psychiatric department

(831)466-72-90 7 psychiatric department

(831)466-73- 30 8 psychiatric department

(831)466-75-30 9 psychiatric department

(831)466-35-68 12 psychiatric department

(831)466-73-21 13 psychiatric department of compulsory treatment

Reception of packages is carried out through the duty staff of the department in which the patient is from 10-00 to 12-00 and from 16:00 to 18:00. Perishable food products are not accepted, only long-term storage products are allowed: non-perishable fruits, sweets, cookies, bakery products, bottled water up to 1.5 liters.

Perishable food products are not accepted, only long-term storage products are allowed: non-perishable fruits, sweets, cookies, bakery products, bottled water up to 1.5 liters.

Administration.

At present, GBUZ NO "NOPNB No. 1" is the leading specialized psychiatric institution in the region with 850 beds. The hospital has 11 inpatient departments, a dispensary department, diagnostic and treatment services and offices. The only children's psychiatric department in the region with 60 beds meets modern requirements, experienced specialists work in the department: psychiatrists, teachers, educators, psychologists. The hospital is an organizational and methodological center for coordinating the activities of all psychiatric institutions in the region. nine0007

Today, the hospital employs more than 500 employees, including many young people. The hospital is strong with its traditions, labor dynasties, many employees have the highest qualification category.

Recently, the material and technical base has significantly improved, departments and services have been renovated, and much attention has been paid to interior elements and domestic comfort.

In recent years, the hospital has been implementing a biopsychosocial model of mental health care. One of the aspects of this assistance is rehabilitation work with patients aimed at increasing the social competence of patients, improving their communication skills, as well as social protection and support. Rehabilitation work is carried out in all departments of the hospital by highly qualified specialists. nine0007

Since 1993, on the basis of the hospital, cycles of improvement of mid-level medical workers of psychiatric health care and social protection institutions have been regularly conducted.

The fusion of maturity and youth, experience and research, responsibility to colleagues and duty to patients allow hospital staff to solve complex problems in modern conditions.

- Previous

- Next

Lifelong treatment. Why psychiatric hospitals are becoming prisons and how Georgia is trying to change that

- Nina Akhmeteli

- BBC Russian Service, Georgia

Photo by Dato Koridze (RFE/RL)

Psychiatric institutions, where patients often spend most of their lives, are still the most common form of treatment for people with mental disorders in many post-Soviet countries. After the release of shocking reports on living conditions in Georgia's largest psychiatric institutions, human rights activists are calling on the authorities to accelerate the reform of a system that isolates vulnerable people from society. nine0100

In 2004, David Dgebuadze, a graduate of the Faculty of History of Tbilisi University, ended up in a psychiatric clinic. “Some things seemed to me, and I signed a consent to voluntary treatment,” he says. He became a patient of a psychiatric hospital for 16 years.

“Some things seemed to me, and I signed a consent to voluntary treatment,” he says. He became a patient of a psychiatric hospital for 16 years.

David does not tell in detail about his diagnosis, but he proudly says that he was born on Mtatsminda, in the center of Tbilisi. After graduating from high school, he lived in a church for three years - he says that a priest offered him to stay there. After an attack of illness, David ended up in the hospital - the first of many during his treatment. nine0007

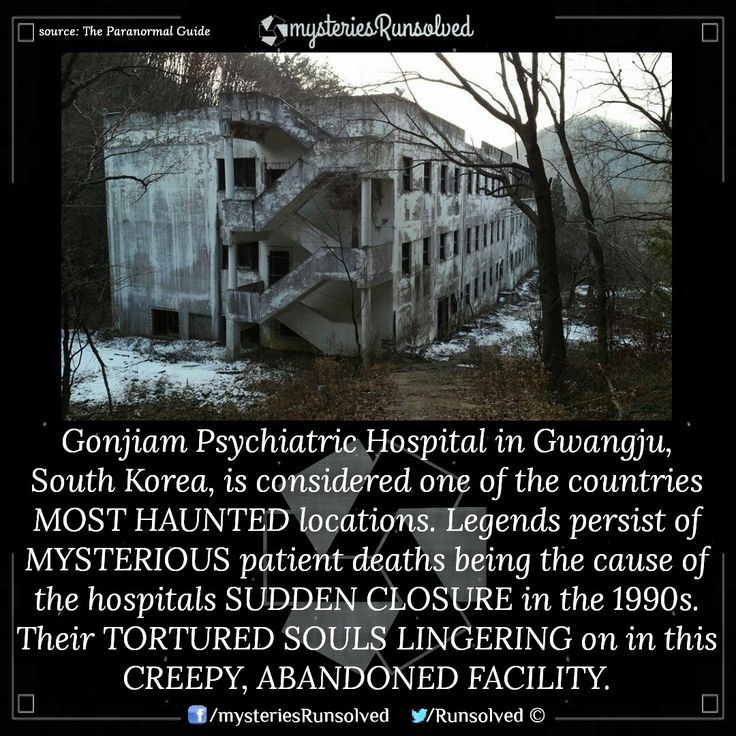

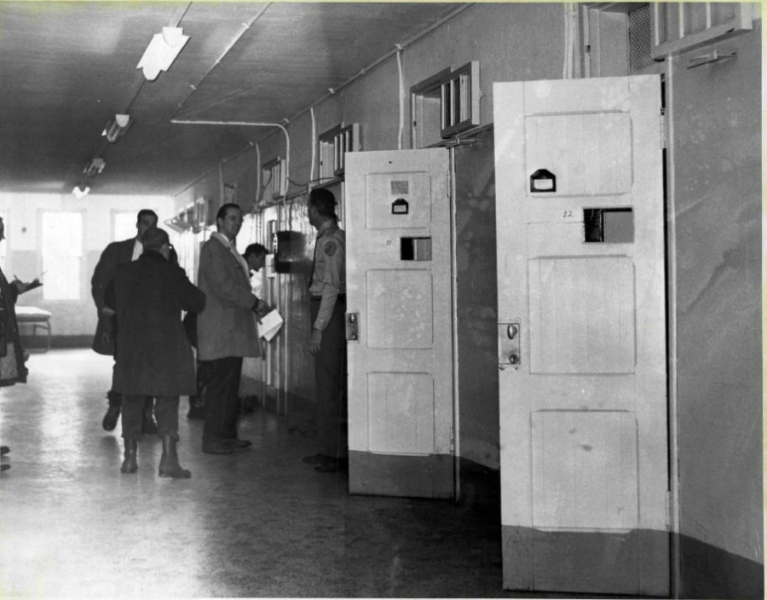

"It was the worst in Bediani," says Dgebuadze about the psychiatric clinic, which for a long time served as a de facto city-forming institution for a village in southern Georgia. . Six to eight beds in a room and a common bedside table."

The author of the photo, Dato Koridze (RFE/RL)

Photo caption,The hospital in Bediani was called the symbol of Soviet psychiatry

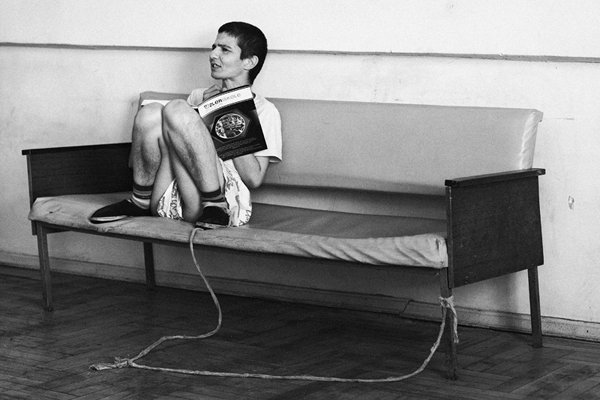

David lived in Bediani for about four years. According to him, patients there were treated rudely: they tied them up and sometimes used physical force. “They took away my clothes there, they said: “We have such rules - everyone has the same clothes,” he says.

“They took away my clothes there, they said: “We have such rules - everyone has the same clothes,” he says.

Last fall, the Office of the Public Defender of Georgia (Ombudsman for Human Rights) published a shocking report following a visit to the Bediani hospital. According to the report, the wards were overcrowded and many had nowhere to store their personal belongings; toilet doors did not close; patients had to share a washcloth and sometimes shower together.

- When the house is a prison and the coronavirus does not make sense. How people with mental disorders cope with isolation

- Euthanasia due to mental illness. Was there an alternative? nine0078

- Delegated Munchausen Syndrome: a form of child abuse

The village could only be reached by minibus, which ran only once a day, and in order to catch the return flight, relatives could spend only a few minutes with patients. Communication between women and men in the hospital was prohibited under the pretext of preventing sexual intercourse. On walks, they could not even talk - the patients were always monitored by staff.

Communication between women and men in the hospital was prohibited under the pretext of preventing sexual intercourse. On walks, they could not even talk - the patients were always monitored by staff.

Located in a gorge behind a high concrete fence, the Bediani psychiatric hospital was called by some a symbol of Soviet psychiatry, a system that sought to hide people with mental disorders from society. nine0007

Georgia has been trying to get rid of this legacy for more than a decade.

Lifelong hospitalization

At the end of 2018, 76.5 thousand people had a diagnosed mental and behavioral disorder in Georgia. In matters of care for these people, the authorities continue to focus on hospitals: more than half of the budget for the mental health program is allocated to these institutions, the treatment in which is paid for by the state.

At the same time, often those who need constant support and care, or who do not have their own housing, are doomed to lifelong isolation in hospitals - in fact, not so much because of their illness, but because of hopelessness. According to the Public Defender's report, out of 158 patients at the Bediani clinic, 64 have been there for more than five years, and half of them have lived there for more than 11 years. nine0007 Photo description,

According to the Public Defender's report, out of 158 patients at the Bediani clinic, 64 have been there for more than five years, and half of them have lived there for more than 11 years. nine0007 Photo description,

David was a patient of psychiatric institutions for sixteen years. Only the hospitals he was transferred to changed

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

The End of the Story Podcast

A psychiatric hospital shouldn't be an orphanage, says Deputy Public Defender Ekaterina Skhiladze. "People shouldn't live for years in medical institutions, especially against the background of the infrastructural problems that are found in psychiatric institutions today," she notes. nine0007

nine0007

From year to year, the Public Defender speaks about violations in psychiatric hospitals and calls for deinstitutionalization - the transfer of patients to a different form of treatment that does not involve permanent residence in the hospital. This process began in Western countries in the middle of the last century, and the World Health Organization considers it one of the main stages in the reform of the mental health care system.

Prolonged stay in closed psychiatric institutions not only does not contribute to recovery, but also leads to the loss of independent living skills, experts say. nine0007

"The vast majority of people with mental disorders can live normally in society, provided the necessary services are available. They should only be admitted to hospitals in case of exacerbation for a short time until their condition stabilizes," says Manana Sharashidze, chairperson of the department of the Georgian Mental Health Association, which has been pushing for the reform of the psychiatric service in Georgia since the 1990s.

The government also agrees with this: according to the action plan for 2015-2020, the decision to hospitalize a patient can only be made after all alternatives to treatment and care have been exhausted. nine0007

But despite the development of some forms of community services, there are still few alternatives to large institutions for those who need care and a roof over their heads, according to human rights activists.

Behind the iron door

Viewers of many Georgian TV channels saw old buildings, rusty shells and dark corridors of the Bediani Psychiatric Hospital last autumn. The authorities acknowledged the violations and announced plans to close the clinic, converting it into a drug rehabilitation center. nine0007

However, on October 18, employees, for whom the hospital is actually the only place of work in a small village, in protest blocked the exit from the clinic with logs, preventing some of the patients from being taken away from there.

As a result, plans to build a drug rehabilitation center in Bediani were abandoned by the authorities, and the status of the psychiatric clinic was changed to a shelter, leaving about thirty patients in the women's ward, which was in relatively good condition.

Most of the Bediani patients were transferred to the National Mental Health Center in the village of Kutiri in western Georgia. Among them was David. nine0007 Image caption,

Walking area outside the renovated building at the National Mental Health Center

In the yard of Kutiri hospital, old net beds are thrown out and have been replaced with new furniture, staff tells me. Behind a concrete fence with barbed wire is a separate building for convicts and those who, by court order, are here for compulsory treatment.

Other buildings have cemented and fenced walking areas.

"It was better there, but there was also a small yard. People were allowed to walk around with their (staff - BBC) permission. There was an iron door that was locked several times a day," David recalls the place where he spent about half a year.

There was an iron door that was locked several times a day," David recalls the place where he spent about half a year.

Some patients are still kept behind metal doors

The massive doors are still there. In one of the buildings, we pass along a long corridor, on the sides of which, through narrow door windows, we can see the thin faces of patients who are undergoing involuntary treatment. Someone through the opening asks the employees of the center for a cigarette. nine0007

Those who were transferred here from Bediani have the same metal doors. Center staff say it's temporary until repairs are completed. Then they are promised to be transferred to rooms with windows without bars and ordinary doors.

I am not allowed to speak to any of the patients - not even those who volunteered here - citing pandemic security measures.

This is the largest psychiatric institution in Georgia, located a few kilometers from the city of Khoni with a population of 9thousands of people. Today, there are about 650 patients and beneficiaries - that is, those who live in the shelter located on the territory of the center. In 2015, 95% of the center was privatized, the remaining 5% is still state-owned.

Today, there are about 650 patients and beneficiaries - that is, those who live in the shelter located on the territory of the center. In 2015, 95% of the center was privatized, the remaining 5% is still state-owned.

The facade of the building that houses the shelter has been half renovated.

Gocha Bakuradze, the general director and owner of the center, proudly says that he was one of the first to declare a quarantine and a ban on receiving visitors since the beginning of March. Since then, patients can only communicate with relatives by phone. nine0007

"Everyone treats this with understanding," Bakuradze believes. "Everyone knows that there are no alternatives to compulsory treatment units in our country. God forbid, an infection will get there, where will you transfer these people? To a hotel? This is is excluded. Therefore, I observe everything especially strictly. "

"We will treat you however you like"

The living conditions in the orphanage at the Kutiri hospital were also called inhuman and degrading in the Ombudsman's report. nine0007

nine0007

The facade of the building where the shelter is located is half renovated. At the old part, untouched by the renovation, with peeling walls, laundry is being dried, but the staff of the center does not allow me to go inside.

The Ombudsman's greatest criticism, however, was not the center's infrastructure, but its established practice of treating patients. According to the report, they were subjected to methods of "physical and chemical containment" - that is, fixation (binding) of patients and antipsychotics - drugs that suppress nervous activity and emotional state. This included those under voluntary treatment, and according to the report, "physical restraint" was sometimes used in the presence of other patients. nine0007 Image caption,

The staff of the center promise to transfer patients to rooms with bare windows and ordinary wooden doors after the renovation.

Such methods were common not only in Kutiri. Olga Kalina, a human rights activist and one of the founders of the Platform for New Opportunities, first entered a psychiatric hospital at the age of 21. There was no alternative to the hospital at that time, and therefore, when she first became ill, her relatives took her to a hospital on the outskirts of Tbilisi. There, Olga was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, a disorder characterized by a distorted perception of reality and can manifest itself in hallucinations. nine0007

There was no alternative to the hospital at that time, and therefore, when she first became ill, her relatives took her to a hospital on the outskirts of Tbilisi. There, Olga was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, a disorder characterized by a distorted perception of reality and can manifest itself in hallucinations. nine0007

- "I hid my psychosis for ten years." The story of a man with hallucinations

- Depersonalization: a syndrome that interferes with feeling

"They just locked me there. When I tried to protest it and asked why the door was closed, they tied me up and used neuroleptics," Kalina recalls her first hospital. "Nothing was explained : neither what is wrong with me, nor what course of treatment is possible, nor how long I will be there.

After that, Olga ended up in a psychiatric hospital twice more. Patients were tied up, she recalls, sometimes using force. “The woman could not move, more likely for mental reasons, and not because of her physical condition. The orderlies beat her in order to convince her that she needed to get up and move,” says Olga. nine0007

“The woman could not move, more likely for mental reasons, and not because of her physical condition. The orderlies beat her in order to convince her that she needed to get up and move,” says Olga. nine0007

The last time Kalina came to the hospital was in 2011 - then she already had experience of working in a non-governmental organization, and she knew her rights as a patient. But it didn't always help.

Photo copyright, Olga Kalina

Photo caption,Olga Kalina now works for three organizations dedicated to protecting the rights of people with disabilities and promoting psychiatric reform

I was told that the psychiatrist will be on Monday, and before that we will treat you as you like. I was then given an injection in the back of my body in front of other patients. It was very humiliating, but the staff does not understand this, she says. “If a person somehow protests, expresses dissatisfaction, then this is considered an exacerbation of the disease or psychosis. ” nine0007

” nine0007

In their report on the situation at the Kutiri Psychiatric Center, human rights activists also referred to the quality of medical care: in most medical records, 25 patients who died in this hospital or shortly after being transferred from it from the end of January 2018 to the end of April 2019, the cause of death Sudden death from acute cardiovascular failure was indicated. The report notes that in some cases, an overdose of antipsychotic drugs and a risky combination of medications without regard to the patient's physical condition could lead to a deterioration in the condition of patients. nine0007

The center says that there is a therapist on staff who immediately responds to patients' health problems, and, if necessary, they are taken to other institutions by an ambulance team.

Photo caption,The newly refurbished building has a light reception area for visitors. Photographs of the old building on the walls

According to Gocha Bakuradze, director of the center, he does not understand the meaning of the term "chemical containment" at all, and physical containment is the most extreme measure that is rarely used in the institution. In addition, other psychiatric institutions often "select patients" and transfer the most problematic ones to them, complains Bakuradze. nine0007

In addition, other psychiatric institutions often "select patients" and transfer the most problematic ones to them, complains Bakuradze. nine0007

"You see, all the numbers compared to other psychiatric institutions will be much higher, because there are many more patients. And if there is such an approach, as some of my colleagues in other psychiatric institutions: "Oh, this is too acute If we need to translate it, we cannot accept it," then, of course, there will be more fixation and use of medicines in Khoni," he says.

Childbirth in the toilet

Other shocking examples of conditions in psychiatric hospitals are cited in the Public Defender's reports. Thus, the staff of the hospital in Bediani found out about the patient's pregnancy only after she gave birth in the toilet without assistance. However, in the previous months she had been treated in two clinics and, according to her medical records, she had visited a gynecologist. The report also notes that she took psychotropic medication during her pregnancy. nine0007

The report also notes that she took psychotropic medication during her pregnancy. nine0007

Chairman of the Georgian Psychiatric Society and Deputy Director of the Tbilisi Mental Health Center Eka Chkonia calls this case out of the ordinary, but admits problems with providing other medical care to patients in psychiatric hospitals.

If a person is brought from such a clinic, or if they have a suspected mental disorder, regular hospitals are often reluctant to admit them.

"Recently, a patient with liver failure was brought to us, he vomited blood, and, of course, he had an altered consciousness. His family barely agreed to be transferred to another clinic. And this often happens," says Chkonia . nine0007

The author of the photo, Dato Koridze (RFE/RL)

Photo caption,Reports of the Georgian Ombudsman for Human Rights described the terrible living conditions in large psychiatric institutions

On the other hand, patients from other hospitals are rarely referred to psychiatrists, even if such assistance is needed. “For example, during a suicide attempt, they are brought to emergency therapy and often then directly discharged home,” says Chkonia. “While in such cases, the likelihood of a repeat attempt within a month is high. But no one sends them to psychiatrists.” nine0007

“For example, during a suicide attempt, they are brought to emergency therapy and often then directly discharged home,” says Chkonia. “While in such cases, the likelihood of a repeat attempt within a month is high. But no one sends them to psychiatrists.” nine0007

Specialists and human rights activists have been calling for the replacement of individual psychiatric hospitals with departments in general hospitals for years, believing that this will not only facilitate access to medical services, but also help combat stigma against people with mental disorders.

The government says they are striving for this, but complain about the lack of personnel. According to First Deputy Minister for Health and Social Protection Tamar Gabunia, psychiatric departments have already appeared in multidisciplinary hospitals, but later they had to be closed due to a lack of qualified personnel. nine0007

To replenish the staff, the state pays for a residency program in psychiatry - postgraduate medical education, but it takes years to train specialists.

An alternative to hospitals

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, funds for the maintenance of psychiatric hospitals, and hence the places in them, became less and less, and the quality of service became worse.

"From 1990 to 1995, more than 800 patients with mental disorders died in such closed institutions. At the same time, more people died in those institutions that were far from the city center or in remote regions. This is what an institution means. People were left behind, relatives they could not be visited,” says Manana Sharashidze of the Georgian Mental Health Association. nine0007

You need to enable JavaScript or use a different browser to view this content

Video caption,Residents of boarding schools move home to volunteers during quarantine

With a group of specialists and the help of international donors, in 1999 she opened a center for psychosocial rehabilitation at a psychiatric hospital in Tbilisi. Today the center has its own building; it is visited by forty-five people - these are people with chronic mental disorders. nine0007

Today the center has its own building; it is visited by forty-five people - these are people with chronic mental disorders. nine0007

An individual plan is developed for each visitor of the center, which is adjusted every six months. The center provides both group and individual therapy. Some are taught to use the Internet and social networks, some learn English, hoping that this will help in finding a job.

There are three such psychosocial rehabilitation centers in Georgia, the services in which are fully financed by the state. But this, according to experts, is not enough for the full integration of people with mental disorders into society, and there are still no effective programs for their employment. nine0007

The Association of Mental Health also operates an outpatient clinic where patients can receive medical care, and two mobile teams - outreach teams that advise and make home visits to more seriously ill patients. This is the most dynamically developing type of service: in total, about 30 such teams operate in Georgia, eight of them are in Tbilisi.

In a rehabilitation center, patients practice art therapy and learn how to use the Internet

The prototype of the mobile teams was the Assertive Treatment Team, which started in Tbilisi in 2013 with support from the Open Society Foundation. It is designed for home care of people with severe mental disorders and those who, in addition to them, have a dependence on psychoactive substances. This team now consists of 13 people who visit one person on average 8-9once a month (mobile teams of three people - 2-3 times), says Giorgi Geleishvili, assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Tbilisi State Medical University from the Evidence-Based Practice Center, a non-profit organization that focuses on assertive treatment.

In addition to providing direct care to the patient, specialists also work with families to help them better understand the disease and how to care for their loved ones.

Today, one hundred residents of Tbilisi use this service. Only those who have been hospitalized at least three times or spent more than five months in a hospital in a year can get into this program.

Only those who have been hospitalized at least three times or spent more than five months in a hospital in a year can get into this program.

"Assertive care costs the state about the same amount [as hospitals]," Geleishvili assures, "with the difference that patients are outside the hospital, well-groomed, treated and rehabilitated, and not closed in institutions."

- Selfharm: when mental wounds turn into body wounds

- Living with autism. How I overcame the bad mother complex

But I failed to convince the government to allocate funds to finance this program. Only the city authorities of Tbilisi came forward, which since May 2016 finance about 80% of the costs of assertive service.

Crisis intervention groups are also operating in four cities of Georgia to reduce the burden on hospitals, helping people at home with symptoms of acute psychosis or behavior that threatens the life of the patient or his environment. nine0007

nine0007

Despite some progress in reforming the health care system, critics accuse the authorities of inconsistency: along with the development of community services, the largest psychiatric institution in the country - the center in Kutiri - continues to grow.

The author of the photo, Dato Koridze (RFE/RL)

Photo caption,According to human rights activists, the approach to treating patients in institutions is impersonal and ignores the needs of the patients themselves

"We will not achieve such a fantastic development of community services that hospitals are not needed," says Geleishvili. "But these should not be hospitals for 600 people." nine0007

Deinstitutionalization is not a goal, but one of the mechanisms to ensure that people with mental health problems have every opportunity to realize themselves, said Deputy Minister for Health and Social Protection Tamar Gabunia.

"We need to have a full range of all services that a person with mental health problems may need. These are acute care in the hospital, various community services, and if a person has a chronic problem that does not require active, acute intervention, he should be able to live peacefully in a comfortable environment within the community,” she says. nine0007

These are acute care in the hospital, various community services, and if a person has a chronic problem that does not require active, acute intervention, he should be able to live peacefully in a comfortable environment within the community,” she says. nine0007

Family homes

David was one of the few people who, after many years in a psychiatric hospital, was transferred to the so-called family-type home, government-sponsored housing where people with mental and developmental disabilities live together. For those who need care, assistants help. Residents of such houses receive medical care either in an outpatient clinic or from mobile teams.

"It's better here, the atmosphere is friendly, the people are happier. I really missed it. I'm free here. I'll live in peace. After all, a person cannot live closed all his life," says David, sitting on the wide balcony of the family house, which is served by a non-governmental organization "Hand in hand". nine0007

nine0007

David shows me his room, which he shares with two other people. He has a separate wardrobe for clothes, which, however, is still almost empty. David says that he loves to read, but there is only one book on the shelves so far - the stories of Mark Twain.

"It's nice here, but of course it's better to have your own place. I'll live here for a few years and then I'll move. I have a brother, a year and a half younger. He's already visited me here. I want to live with him, but he I don’t have my own home either,” complains David. nine0007

It takes time to adapt after being transferred from closed institutions, says Maya Shishniashvili, founder of the Hand in Hand organization. “Most of them (patients in psychiatric hospitals - BBC) are victims of violence. I don’t mean just beatings or insults. They are victims of a system that does not give you the right to choose - wake up so much, eat so much and this dish, and now you have to rest. This is also violence," she says.

This is also violence," she says.

In the family home, David can lead an almost normal life

Shishniashvili opened her first family home in 2011 at her parents' home in Gurjaani, eastern Georgia. She got the idea after her son was diagnosed with a rather rare diagnosis - Angelman syndrome, which is characterized by developmental delay, speech impairment, chaotic movements and spontaneous laughter. Maya thought about what the future might hold for her son. All that the state could offer was lifelong isolation in a large institution.

"I wanted to create a service that would replace a family, help people with disabilities who need support and who lack the skills for an independent life," says Shishniashvili, adding that she was guided in everything by what she would like for her son. "The main thing is a person, and the service should adapt to his interests and needs, and not vice versa. This idea turned out to be completely new, alien and difficult to implement here," she says. nine0007

nine0007

Initially, only people with developmental disabilities lived in family homes, but since 2015 the organization has begun to accept patients with mental disorders.

"Nobody then believed that it was possible. And the regulations were such that in psychiatric institutions they refused to transfer people to us," Maya says.

Today "Hand in Hand" already has six family houses in Gurjaani and Tbilisi, and soon it is planned to open another one in Batumi. For each inhabitant, the state allocates about $10 a day. Three or four assistants work in each house, replacing each other. They help solve everyday problems, monitor the health of residents and develop their skills for independent living. nine0007

According to Shishniashvili, assistance in finding a job is also part of the service, and 40-50% of family home residents are employed.

The author of the photo, Maja Shishniashvili

Photo caption,Maya says that when creating family houses, she was guided by the needs of her son

"We try to have no more than five, maximum six people in each house," says Maia Shishniashvili. “More is already an institution, and strict rules begin.”

“More is already an institution, and strict rules begin.”

The government is talking about plans to open several more larger houses, including those who live in the Kutiri orphanage. But human rights activist Olga Kalina believes that such houses will be of little use. nine0007

"Even if five or ten people live [in the house], they will be told when to get up, when to eat - it will be an institution. Institutional culture is, first of all, a regime and restrictions on freedom of movement, freedom to call someone "To see someone. These restrictions are not corrected by the number," says Kalina.

Stigma

People close to patients often oppose the removal of people with mental disorders from isolation, who for one reason or another do not want or cannot take care of them. In conditions when outside the walls of the hospital there is no necessary support either from the state or from relatives, human rights activists also face a dilemma. nine0007

nine0007

"Human rights defenders' hands are tied. Although it's illegal - despite signatures for voluntary treatment, people are there [in psychiatric institutions] not voluntarily, they are locked up, they are subjected to physical methods such as tying up - this continues. Because the alternative - let them go nowhere, actually into the street," says Kalina.

In a society that is accustomed to the fact that people with mental disorders live in isolation, stigma is one of the main barriers to mental health reform. nine0007 Image caption,

People who have lived in isolated psychiatric hospitals for a long time lose their independent living skills over time

People with mental disorders suffer from violence, stigma and the stereotype that a person with a mental disorder is a priori dangerous and aggressive, experts say . According to psychiatrists, such people often pose a greater danger to themselves than to others.

Olga Kalina currently works for three organizations dedicated to protecting the rights of people with disabilities and promoting psychiatry reform.