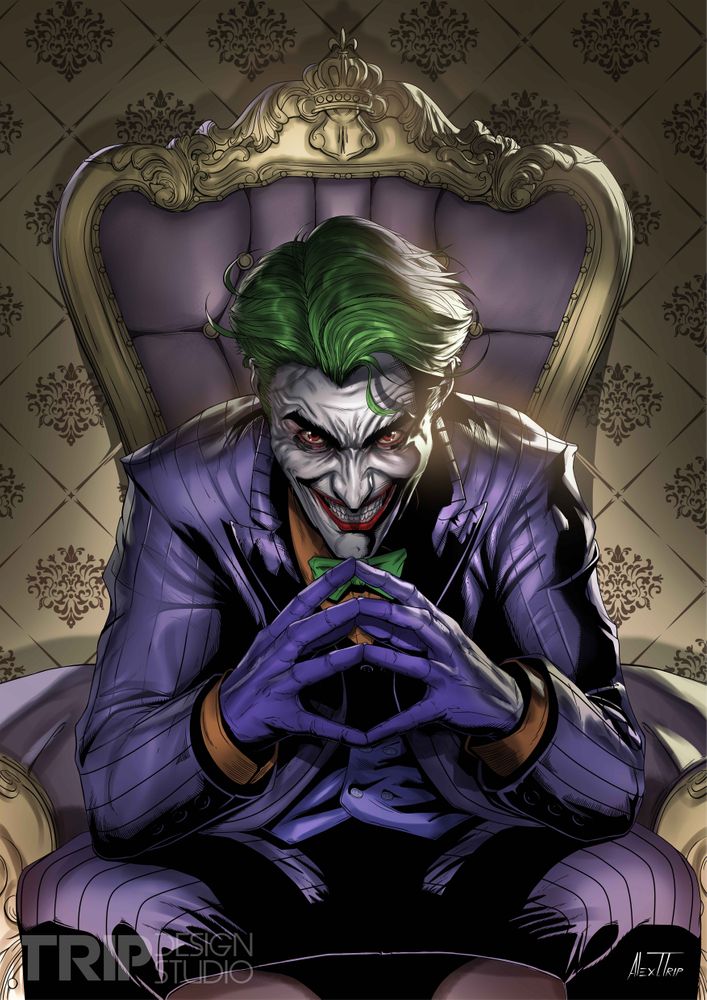

Joker psychological profile

The Psychology of the Joker from ‘Joker’ (2019)

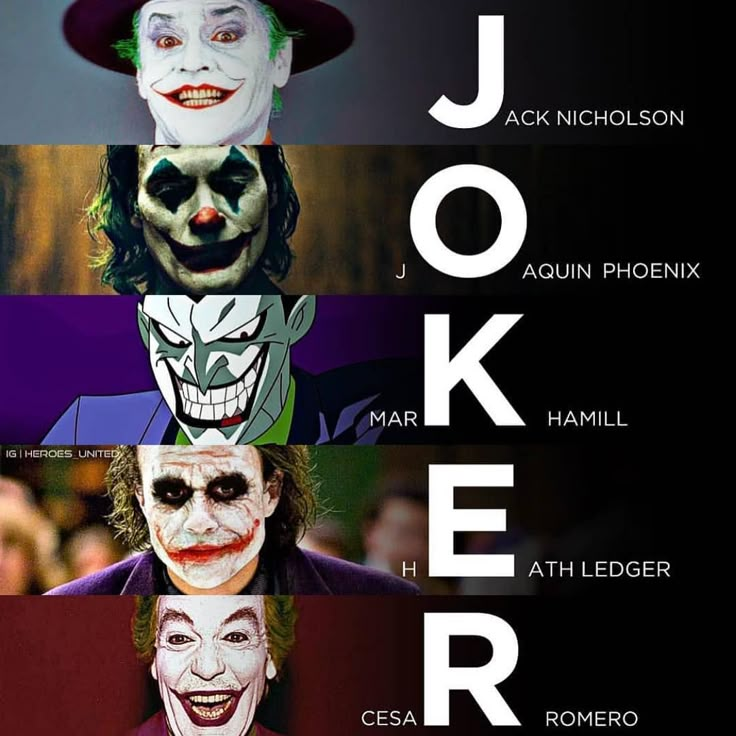

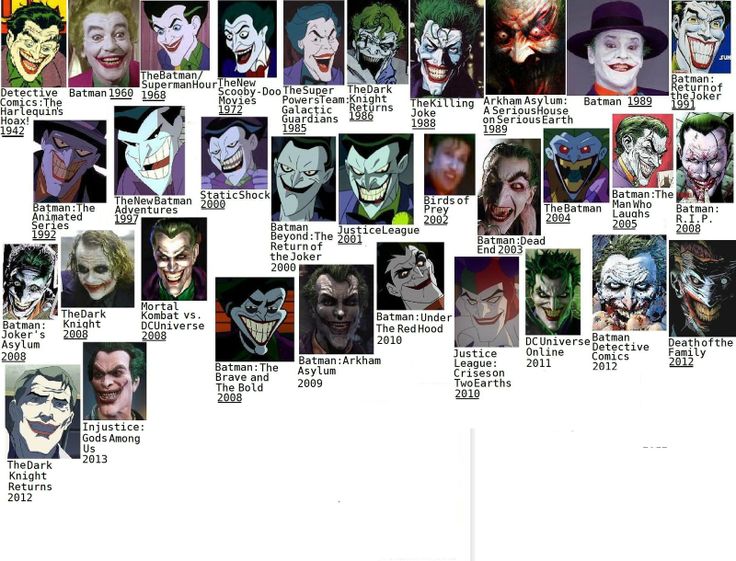

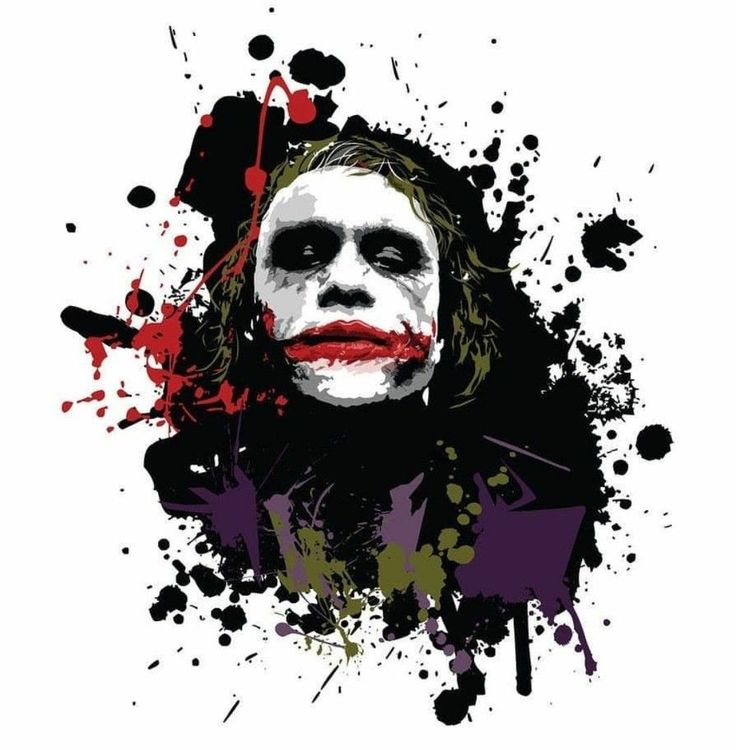

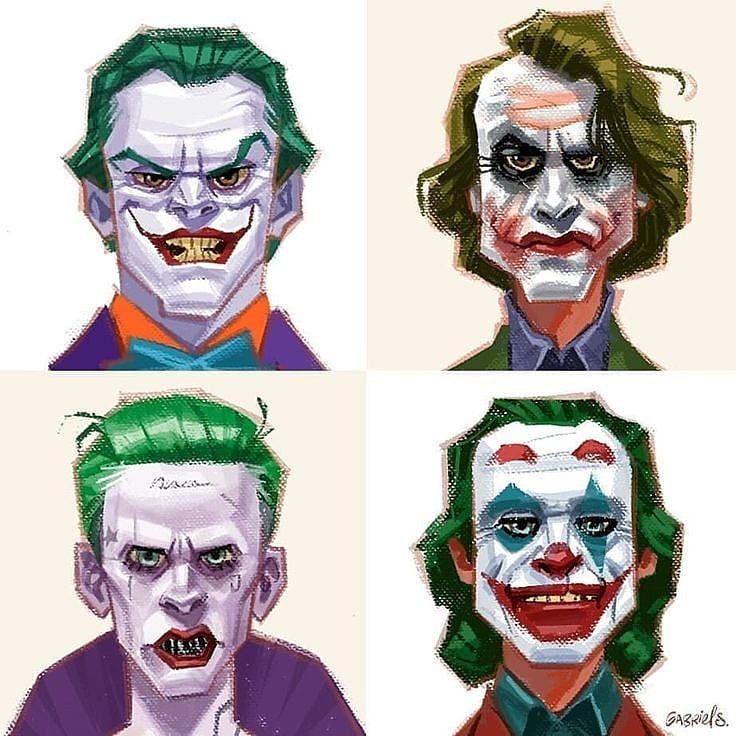

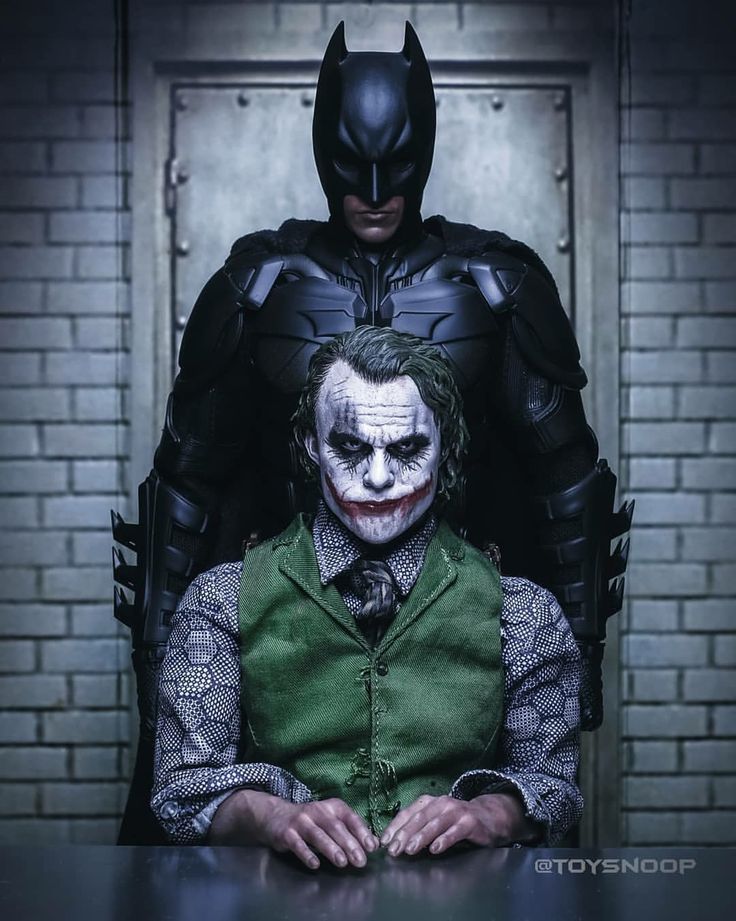

The Joker is a villain that both fascinates and terrifies us. His origin has remained relatively mysterious, sparking questions about how a “psycho killer” is created. Using real methods and theory, clinical expert Dr. Andrea Letamendi examines several portrayals of the Clown Prince of Crime, including Jack Nicholson in 1989’s Batman, Heath Ledger in The Dark Knight, and Mark Hamill in Batman: The Animated Series. Given the raised concerns causing tension to surround the new film, Joker (2019), considerations are given to the science behind behavioral threat assessment, case study, and occurrences of real events in an effort to responsibly inform the discourse. The author wishes to note to readers that this collection of psychological profiles includes some references and descriptions of both real and fictional portrayals of mass violence, intimate partner abuse, and suicide. Just like the Joker, these conceptualizations are fictional and are not meant to diagnose any real person.

This series is not intended as a substitute for the medical or mental health advice of psychiatrists or other clinical professionals.

SPOILER WARNING: Full spoilers for Joker follow.

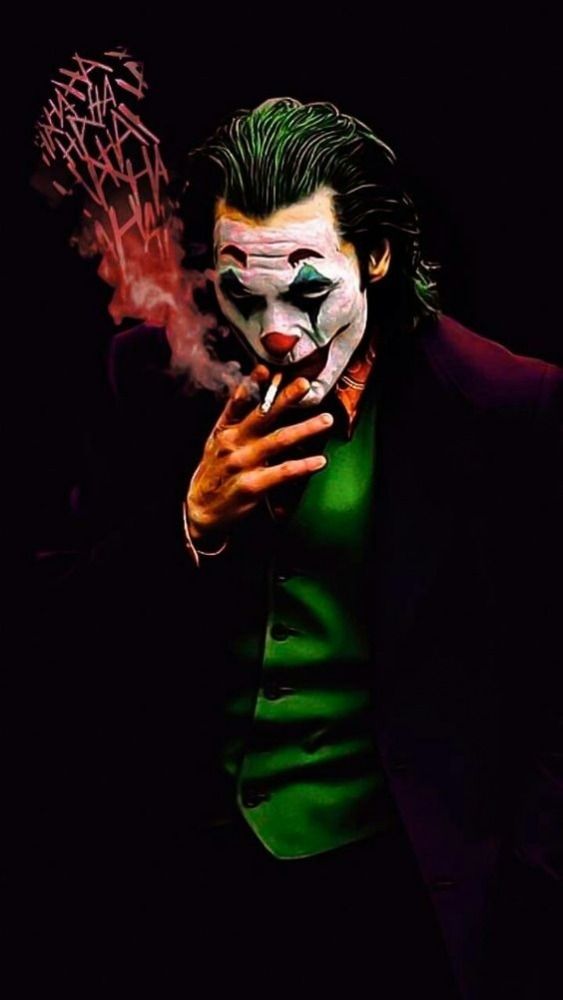

The Misunderstood LonerArthur Fleck, played by Joaquin Phoenix in the solo origin story film Joker (2019) is an impoverished, scraggy middle-aged man who works as a party clown in the crime-riddled city of Gotham. Arthur is significantly underweight, his face sunken and pallid; and although he isn’t repulsive, his untidy, bizarre appearance is off-putting to others. Behaviorally, too, Arthur is odd. He is withdrawn and anti-social, but does not seem to be inherently callous or devious. In fact, Arthur is somewhat innocent and initially well-meaning toward others, especially children. Arthur lives with his mother, Penny, who he cares about deeply, but maintains no other strong, meaningful connections. His communication skills are generally poor; he may hold his gaze too long at someone, use abnormal body posturing or facial expressions, or miss important interpersonal cues, which cause others to be upset or discomforted around him. In his line of work as a cheap party clown, Arthur’s oddities are amplified. In many ways, Arthur is a product of interactionalsocialization; his peculiarities influence others to ostracize, bully, or avoid him, which in turn, lead him to isolate, grow weirder, and inevitably miss opportunities to improve his social skills.

In his line of work as a cheap party clown, Arthur’s oddities are amplified. In many ways, Arthur is a product of interactionalsocialization; his peculiarities influence others to ostracize, bully, or avoid him, which in turn, lead him to isolate, grow weirder, and inevitably miss opportunities to improve his social skills.

Importantly, Phoenix’s Joker does not try to be disturbing or strange; he does not seek the thrill of upsetting or endangering others.

This Joker is not inherently provocative. In fact, when we’re introduced to him, Arthur has little insight in how he comes across to others. He’s generally aware that he is odd, but does not quite grasp the degree to which others find him unsettling. Quite the contrary, Arthur dreams of winning the adoration of others by becoming a successful stand-up comedian. He believes his purpose in life is to instill happiness in others—his overactive fantasies depict his mother as his number one support: “you were put on this earth to spread joy and laughter,” he imagines her saying to him adoringly. Arthur fantasizes of being in the spotlight, basking in the glow of show lights, approval, and applause. At times, he even closes his eyes and slowly dances to the sound of imaginary music; picturing himself as the center of attention, a popular figure like the famous talk-show host, Murray Franklin: visible, idolized, and respected. As he pantomimes the scene, Arthur envisions himself as charming, masculine, and dominant. Despite these uplifting dreams, Arthur’s actual life as a loner is monotonous, repetitive, unrewarding, and—much like the landscape of the Gotham City—hopelessly bleak.

Arthur fantasizes of being in the spotlight, basking in the glow of show lights, approval, and applause. At times, he even closes his eyes and slowly dances to the sound of imaginary music; picturing himself as the center of attention, a popular figure like the famous talk-show host, Murray Franklin: visible, idolized, and respected. As he pantomimes the scene, Arthur envisions himself as charming, masculine, and dominant. Despite these uplifting dreams, Arthur’s actual life as a loner is monotonous, repetitive, unrewarding, and—much like the landscape of the Gotham City—hopelessly bleak.

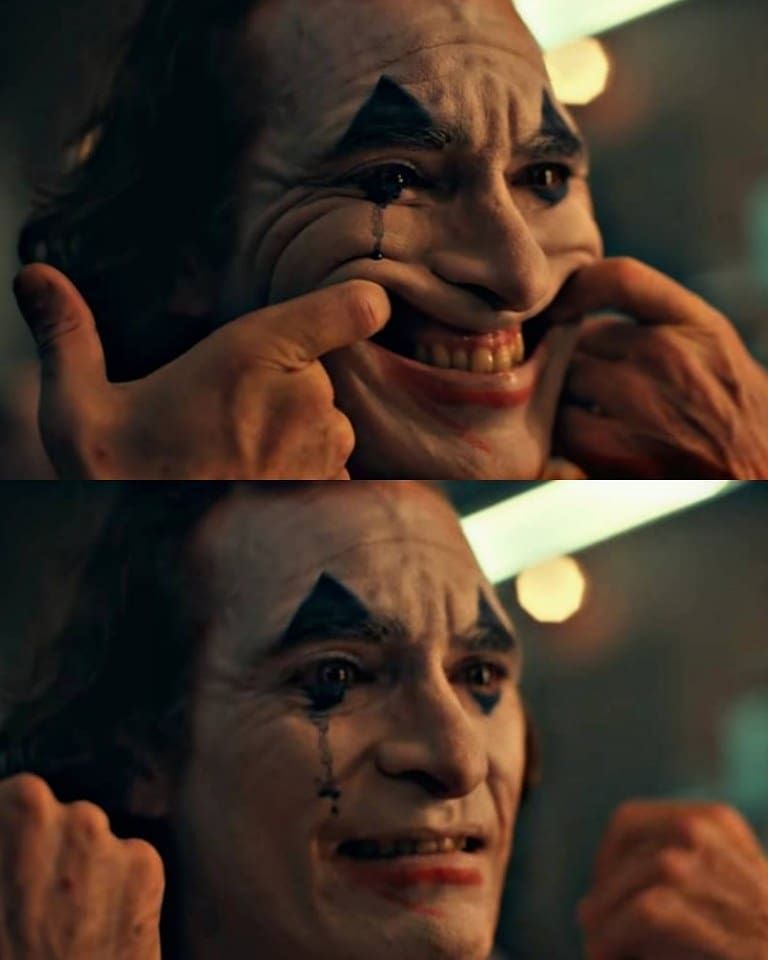

In his portrayal, Phoenix delivers a unique biological basis for the Joker’s maniacal laughter. Arthur lives with a neurological condition that is described in the film as spontaneous, socially inappropriate laughter. The episodes are typically precipitated by an intense feeling of nervousness, anxiety, or shame. Laughter, the external expression of joy, is therefore in misalignment with his internal state of emotions. A single episode may last longer than a minute, and increases in intensity and loudness. The fits become so uncomfortably uncontrollable for Arthur that it causes him to cry, stutter, and react with guttural chokes.

A single episode may last longer than a minute, and increases in intensity and loudness. The fits become so uncomfortably uncontrollable for Arthur that it causes him to cry, stutter, and react with guttural chokes.

The condition called Involuntary Emotional Expression Disorder (IEED), also known as pseudobulbar affect, is indeed a real neurological disease characterized by emotional lability, and pathological laughing. This expressive disorder is characterized by uncontrollable, sudden and intense episodes of laughter (or for some patients, crying) that are exaggerated and incongruent with the underlying mood. These episodes can be long-lasting, and are often embarrassing and socially debilitating for individuals who struggle to convey their real, experienced emotion.

The psychological outcome often includes outbursts of frustration, anger, and the development of depression.

IEED’s cause is unclear; but it is associated with traumatic brain injury, typically to the prefrontal cortex (the brain region just behind the forehead). Consistent with this theory, it is revealed in the film that Arthur was physically abused as a child, and experienced a significant violent assault that caused head trauma. It is theorized that IEED is a reflection of damage to the neuronal pathways that cause emotional expression, and it is highly likely that Arthur’s childhood injuries lead to the condition he has as an adult. Moreover, the behavior observed in patients with IEED (grinning, laughing, cackling, etc.) is not interpreted as actual laughing by medical professionals but considered a deficit in the patient’s ability to control their facial muscles. The inclusion of pathological laughter and distorted facial gestures –a neuropsychological manifestation of the Joker’s trauma—is more realistic if not an improvement of the existing Joker narrative. Disturbing laughter is not a result of the Joker’s disfigurement, self-injury, or a tactic to unsettle others; his laughter is his disease, a part of his psychiatric makeup that ultimately leads others to stigmatize him.

Consistent with this theory, it is revealed in the film that Arthur was physically abused as a child, and experienced a significant violent assault that caused head trauma. It is theorized that IEED is a reflection of damage to the neuronal pathways that cause emotional expression, and it is highly likely that Arthur’s childhood injuries lead to the condition he has as an adult. Moreover, the behavior observed in patients with IEED (grinning, laughing, cackling, etc.) is not interpreted as actual laughing by medical professionals but considered a deficit in the patient’s ability to control their facial muscles. The inclusion of pathological laughter and distorted facial gestures –a neuropsychological manifestation of the Joker’s trauma—is more realistic if not an improvement of the existing Joker narrative. Disturbing laughter is not a result of the Joker’s disfigurement, self-injury, or a tactic to unsettle others; his laughter is his disease, a part of his psychiatric makeup that ultimately leads others to stigmatize him.

Unlike other portrayals, Phoenix’s Joker struggles to achieve a sense of intrinsic happiness and seems unable to activate pleasurable feelings within himself. Nicholson’s Joker, for instance, delights in his ostentatious, grand acts of performative terrorism; Hamill’s sustains euphoric mania by increasingly pushing the boundaries of risk-taking; Ledger’s Joker seems to be skilled in generating intellectual satisfaction. These Jokers certainly presented with their own idiosyncratic problems, but were able to find ways to achieve feelings of pleasure. Arthur Fleck attempts to find joy through his stand-up comedy, but cannot overcome the barriers of his disease. He is instead met with doubts, derision and even dismissive reactions from his own mother, who casually tells him, “You have to actually be funny to be a comedian.” Phoenix’s Joker directly deals with mental illness. He gives us, in his story, clear evidence that he has biomarkers of a brain disorder. Unlike other portrayals of the Joker, it is not simply implied that he has a characterological flaw. Phoenix’s Joker attends therapy, takes psychotropic medication, and follows behavioral prescriptions given by his providers. Though his exact psychiatric diagnosis is not named, Arthur makes direct reference to his meds (he is taking up to four different kinds), hispsychotherapy (he sees a social worker for weekly counseling), and his history of severe mental illness (he has been committed to Arkham State Hospital at least once). His treatments are provided at no-cost by Gotham City’s Department of Health as a state-funded service.

Unlike other portrayals of the Joker, it is not simply implied that he has a characterological flaw. Phoenix’s Joker attends therapy, takes psychotropic medication, and follows behavioral prescriptions given by his providers. Though his exact psychiatric diagnosis is not named, Arthur makes direct reference to his meds (he is taking up to four different kinds), hispsychotherapy (he sees a social worker for weekly counseling), and his history of severe mental illness (he has been committed to Arkham State Hospital at least once). His treatments are provided at no-cost by Gotham City’s Department of Health as a state-funded service.

During one therapy session, Arthur asks his therapist, “Is it just me or is it getting crazier out there?” referring to the growing, segmented class of Gotham who are impoverished, disenfranchised and angry. “People are upset,” she responds to him, calmly. “These are tough times.” She isn’t unhelpful, but seems to focus on a set of structured steps or required, systematic checklists, rather than attune to Arthur’s direct (and changing) mental health needs. In the same session, Arthur pulls out his journal, which he says he’s using as a “joke diary” to keep his stand-up notes. The journal includes some scribblings of jokes, but also contains disturbing passages, intense drawings, and torn-out pages of pornographic magazines. His therapist does not seem to notice a glaring red flag: pictures of naked women with the clipping torn at the neck, or hard scribbling covering their faces. These are likely recordings of Arthur’s subversive fantasies. Depersonalizing women by “removing” their faces allows Arthur to objectify them and even experiment with feelings of aggression or sadism toward them. It remains unclear whether these are congruent with his desires or ego-dystonic(intrusive, upsetting thoughts that are not aligned with his sense of self). In the journal, is another red flag: Arthur writes, “I hope my death will make more cents than my life.” Taken together, messages of suicide, vague threats, and pornography are risk factors for targeted violence.

In the same session, Arthur pulls out his journal, which he says he’s using as a “joke diary” to keep his stand-up notes. The journal includes some scribblings of jokes, but also contains disturbing passages, intense drawings, and torn-out pages of pornographic magazines. His therapist does not seem to notice a glaring red flag: pictures of naked women with the clipping torn at the neck, or hard scribbling covering their faces. These are likely recordings of Arthur’s subversive fantasies. Depersonalizing women by “removing” their faces allows Arthur to objectify them and even experiment with feelings of aggression or sadism toward them. It remains unclear whether these are congruent with his desires or ego-dystonic(intrusive, upsetting thoughts that are not aligned with his sense of self). In the journal, is another red flag: Arthur writes, “I hope my death will make more cents than my life.” Taken together, messages of suicide, vague threats, and pornography are risk factors for targeted violence. They are known as “pre-offense” behaviors, due to the direct correlation between these types of passages and consequent acts of violence. This is a missed opportunity in that his therapist may have been crucial in connecting with Arthur during a period of risk, understanding his feelings of resentment and loneliness, and directing him to more effective resources.

They are known as “pre-offense” behaviors, due to the direct correlation between these types of passages and consequent acts of violence. This is a missed opportunity in that his therapist may have been crucial in connecting with Arthur during a period of risk, understanding his feelings of resentment and loneliness, and directing him to more effective resources.

“Does it help to have someone to talk to?” his therapists asks; and Arthur replies, “I felt better when I was locked up in the hospital.”

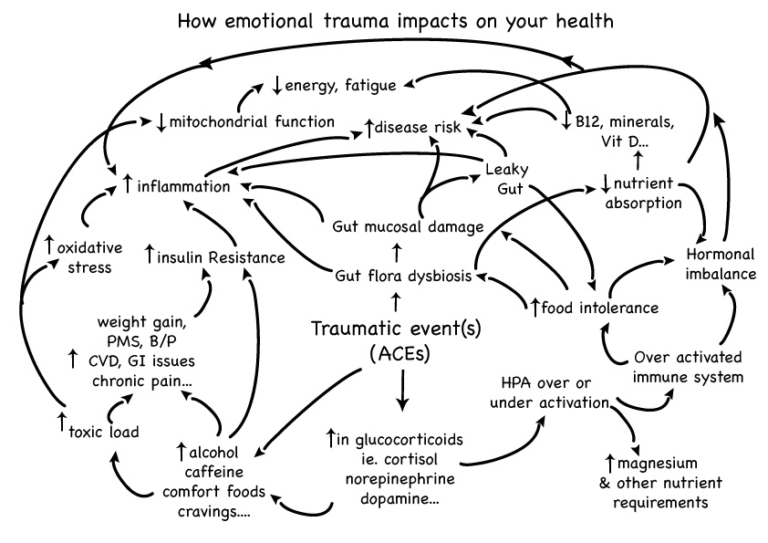

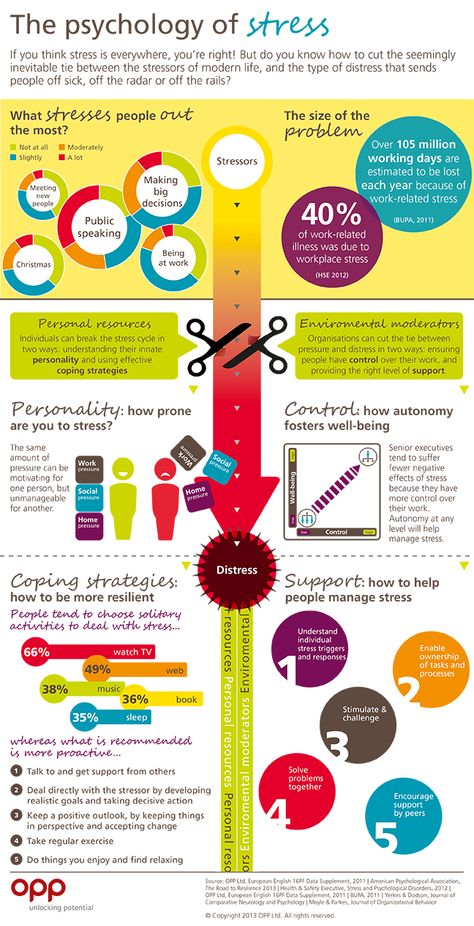

The film cuts to a shot of him banging his head against the wall of his cell. Here, it is likely that he had access to stronger or more intensive treatments, and may have experienced reprieve from his emotional pain. To his therapist, he adds, “I just don’t want to feel so bad anymore.” Arthur acknowledges his depression and his inability to escape from the weight of his disease. Clinical depression is a serious medical condition, rooted in neurobiological causes, that is associated with symptoms such as chronic feelings of melancholy, loss of pleasure, lack of energy, difficulty in concentrating, and suicidal thoughts. Consistent feelings of irritability, physical pain, and anger are also manifestations of depression. For individuals with treatment-resistant depression—in other words, few to no symptoms are relieved by the medication—standard treatments aren’t enough. In fact, up to 30% of people show no or partial response to standard depression medications. Just like Arthur, people who do not seem to respond well to first-line treatments often have severe despair, chronic hopelessness, frequent environmental or family conflict, maternal depression (have a mother with clinical depression), and a history of child abuse. Again, Arthur’s therapist is a key part of his potential remission. Medication is more effective when coupled with talk therapy, especially when the therapist addresses the underlying concerns that may be contributing to the patient’s depression. Psychotherapy is effective because it helps us discover ways to cope with life’s challenges, process past our emotional trauma, learn to manage our relationships in healthier ways, improve how we can reduce the effects of stress, and minimize addictive behaviors.

Consistent feelings of irritability, physical pain, and anger are also manifestations of depression. For individuals with treatment-resistant depression—in other words, few to no symptoms are relieved by the medication—standard treatments aren’t enough. In fact, up to 30% of people show no or partial response to standard depression medications. Just like Arthur, people who do not seem to respond well to first-line treatments often have severe despair, chronic hopelessness, frequent environmental or family conflict, maternal depression (have a mother with clinical depression), and a history of child abuse. Again, Arthur’s therapist is a key part of his potential remission. Medication is more effective when coupled with talk therapy, especially when the therapist addresses the underlying concerns that may be contributing to the patient’s depression. Psychotherapy is effective because it helps us discover ways to cope with life’s challenges, process past our emotional trauma, learn to manage our relationships in healthier ways, improve how we can reduce the effects of stress, and minimize addictive behaviors.

Throughout the film, Arthur is dating Sophie Dumond, a young single mother who lives in his building. We ultimately learn that Sophie is real, but their relationship is completely fabricated in Arthur’s mind. His fantasy-building is so intense that he was able to create a credible romantic narrative between him and Sophie, a story that supported his personal dream of being lovable, funny, and charming. Unlike a hallucination where Sophie would actually be projected, as if real, by Arthur’s mind–or a delusion in which she would be believed to be his actual girlfriend—Arthur’s manifestation of Sophie as his girlfriend is likely a product of his overactive imagination coupled with his desperate need to be seen. To matter. Arthur’s fantasy is one that he writes; he controls how Sophie reacts to him when he performs his stand-up comedy, when he takes her on a loving date, when he barges through her apartment door and forcefully kisses her on the lips. In his fantasy, she is passive and quiet, but she is notably supportive and consoling toward him. Sophie’s compassion fills the void, but soon, this dream is no longer sufficiently soothing to Arthur.

Sophie’s compassion fills the void, but soon, this dream is no longer sufficiently soothing to Arthur.

Arthur also momentarily becomes fixated on another source of emotional support, stemming from the idea that Thomas Wayne is his biological father. Penny had routinely written letters for Wayne, and to Arthur’s knowledge, the Wayne family only represented Penny’s employer before she became ill and was put on leave. Curious, Arthur impulsively opens a letter that Penny had written to Wayne, and reads her pleas for Wayne to take care of his “son.” Arthur is livid in learning the news, feeling resentment toward the Wayne family for not caring for him or his mother.

One thing to note is that before he engages in any violence, Arthur is particularly interested in getting better. This Joker pursues ways to integrate into society through normative, healthy channels. He is treatment compliant. He utilizes his therapy session for self-examination, he does his “homework,” and he takes his medication regularly. When he believes his medication is not working, he asks for higher doses. Arthur also makes concerted efforts to attend his job regularly, despite the challenges involved. His journal reads, “The worst part about having a mental illness is that people expect you to behave as if you don’t.” This belief means that Arthur is both willing to acknowledge that he needs help and that he is tired of asking for help. His descent into antisocial behavior and violence is, in part, influenced by the contextual forces around him. The system fails him.

When he believes his medication is not working, he asks for higher doses. Arthur also makes concerted efforts to attend his job regularly, despite the challenges involved. His journal reads, “The worst part about having a mental illness is that people expect you to behave as if you don’t.” This belief means that Arthur is both willing to acknowledge that he needs help and that he is tired of asking for help. His descent into antisocial behavior and violence is, in part, influenced by the contextual forces around him. The system fails him.

Mental health “protectors” are the social, environmental, and personal factors that help us manage big changes in our lives, push through stress or emotional pain, and even safeguard us from developing mental illness. Arthur’s mother, for instance, is a protective factor for him because she is the source of a loving bond and a purpose in life. Arthur buys her groceries, provides her meals, and bathes her every night—and he genuinely cares for her. They enjoy watching the Murray Franklin show together, as a bonding family ritual. Arthur, of course, holds a fantasy of appearing on the Murray Show. In this fantasy, Murray Franklin welcomes him onto the stage and tells him, in front of the cameras, “I’d give it up in a heartbeat to have a kid like you.” In a way, his parasocial, unharmful relationship with Murray Franklin is a protective factor. Arthur seeks fatherly love, a sense of belonging and acceptance, and he feels somewhat fulfilled from this fictional relationship he’s created with Murray. Murray and Penny are his family.

They enjoy watching the Murray Franklin show together, as a bonding family ritual. Arthur, of course, holds a fantasy of appearing on the Murray Show. In this fantasy, Murray Franklin welcomes him onto the stage and tells him, in front of the cameras, “I’d give it up in a heartbeat to have a kid like you.” In a way, his parasocial, unharmful relationship with Murray Franklin is a protective factor. Arthur seeks fatherly love, a sense of belonging and acceptance, and he feels somewhat fulfilled from this fictional relationship he’s created with Murray. Murray and Penny are his family.

But things take a turn for Arthur, and we begin to see significant changes in his behavior that align with the removal of his protective factors. First, his supervisor punishes him for being physically assaulted on the job; he directs Arthur to return the sign that his assailants used to essentially beat him. Arthur protests, but is met with complete disregard. Unable to express his anger and growing resentment, Arthur smiles awkwardly at his unempathetic boss, and later finds himself aggressively kicking bags of trash in the alley. Seems harmless at first, but this outward display of rage is Arthur’s “tryout,” for future violence. Novel aggression, or the experimentation of new forms of violence, may appear as an early warning sign of future, more severe and lethal forms of behavior for individuals who may be a safety threat to society. Feeling sorry for him, Arthur’s co-worker hands him a pistol one day at his workplace. “I’m not supposed to have a gun,” Arthur says cautiously (and, again, in compliance with his treatment plan). He is hesitant to take it, but agrees to keep the gun as self-protection.

Seems harmless at first, but this outward display of rage is Arthur’s “tryout,” for future violence. Novel aggression, or the experimentation of new forms of violence, may appear as an early warning sign of future, more severe and lethal forms of behavior for individuals who may be a safety threat to society. Feeling sorry for him, Arthur’s co-worker hands him a pistol one day at his workplace. “I’m not supposed to have a gun,” Arthur says cautiously (and, again, in compliance with his treatment plan). He is hesitant to take it, but agrees to keep the gun as self-protection.

While he’s performing at the children’s hospital, Arthur is sloppy. The newly acquired gun drops out of his clown pants and hits the ground in plain sight and is immediately fired. Following his termination is a chain of negative events creating significant loss and disruption in Arthur’s life.

Meanwhile, Arthur becomes fixated on his new weapon. He interprets the concept of a gun as an extension of his emerging identity.

To him, the gun is an emblem of importance; like a badge, a microphone, a spotlight. In search of power and control, he begins to fantasize with the loaded gun in hand. His bizarre, slow dancing is unsettling to watch, but for Arthur, the weapon represents a physical manifestation of his deeply cherished dream, a symbol of his desire to command the attention and praise of others. He is mesmerized by his new toy and the idea that it can bring him the devotion he craves. Over the course of time, the concept of harnessing a meaningful role in the dreary city begins to take shape: “I hope my death will make more cents than my life.” Arthur grows more comfortable with the weapon. In one instance, while fantasizing that he’s being interviewed on the Murray Franklin show, Arthur places the empty barrel of the gun under his chin, pulls the trigger, and throws his head back. Imagining an audience witness his suicide is exhilarating and uniquely satisfying – finally, momentary relief from his pain and suffering. Although he’s not yet sure where to direct it, Arthur begins to connect public violence with feelings of fulfillment and satisfaction.

Although he’s not yet sure where to direct it, Arthur begins to connect public violence with feelings of fulfillment and satisfaction.

Shortly after being fired, Arthur witnesses three Wayne Enterprises businessmen begin to harass a woman on the subway. Feeling uncomfortable and vicariously shameful, Arthur’s neurological condition is triggered, and he starts laughing uncontrollably. The men turn their attention toward him and begin to ridicule him. Once they begin to beat him, Arthur instinctively, pulls out his gun and shoots one of them to death. The other two men, however, he shoots at close range. During his third killing, Arthur is not impulsive or acting in a defensive manner. He is deliberate. Calm. Confident. He identifies as a killer.

Later, Arthur is grappling with the upsetting news that he was adopted by Penny, neglected, and beaten as a child. He discovers that Penny was admitted to Arkham State Hospital for serious mental health problems as well as child endangerment, and that Thomas Wayne is not his father. Overwhelmed with disappointment, Arthur drags all the food out of his refrigerator, climbs into it, and shuts the door behind him. Somewhat like the earlier pantomime of suicide by gunshot, Arthur’s wish to suffocate himself is a new sign of self-destruction. He is challenging his threshold of corporal pain. Notably, Arthur is already at high risk of dying from suicide, due to his pre-existing lack of social connections as well as his sense of “perceived burdensomeness.” This term refers to a deep, genuine experience of feeling unwanted and undervalued by society. Learning that he was adopted triggered significant beliefs that he had no real belonging in this world, no known origin aside from abandonment and abuse. According to the interpersonal theory of suicide, completed suicides are strongly associated with two things: 1) a strong desire to die, and 2) the capabilityof killing oneself. The desire to die is usually associated with thwarted belongingness. Many of us have had this feeling at least once in our lives.

Overwhelmed with disappointment, Arthur drags all the food out of his refrigerator, climbs into it, and shuts the door behind him. Somewhat like the earlier pantomime of suicide by gunshot, Arthur’s wish to suffocate himself is a new sign of self-destruction. He is challenging his threshold of corporal pain. Notably, Arthur is already at high risk of dying from suicide, due to his pre-existing lack of social connections as well as his sense of “perceived burdensomeness.” This term refers to a deep, genuine experience of feeling unwanted and undervalued by society. Learning that he was adopted triggered significant beliefs that he had no real belonging in this world, no known origin aside from abandonment and abuse. According to the interpersonal theory of suicide, completed suicides are strongly associated with two things: 1) a strong desire to die, and 2) the capabilityof killing oneself. The desire to die is usually associated with thwarted belongingness. Many of us have had this feeling at least once in our lives. The second step, however, refers to a threshold that few of us cross. This threshold protects us from acting seriously on thoughts of self-harm. That is, we all typically have a strong sense of self-preservation, the resilient instinct to keep ourselves alive. Acquired capability means that a person has crossedthat protective threshold—they’ve overcome the normal inhibitions against harming oneself. Like with Arthur, this usually occurs when due to habituation of corporal pain and suffering. Arthur is susceptible, at this point, to risk factors, and then goes on to experience numerous additional environmental risk factors for suicide: disruption or loss of social relationships (his mother), financial distress (loss of a job), and intense humiliation (child abandonment and abuse).

The second step, however, refers to a threshold that few of us cross. This threshold protects us from acting seriously on thoughts of self-harm. That is, we all typically have a strong sense of self-preservation, the resilient instinct to keep ourselves alive. Acquired capability means that a person has crossedthat protective threshold—they’ve overcome the normal inhibitions against harming oneself. Like with Arthur, this usually occurs when due to habituation of corporal pain and suffering. Arthur is susceptible, at this point, to risk factors, and then goes on to experience numerous additional environmental risk factors for suicide: disruption or loss of social relationships (his mother), financial distress (loss of a job), and intense humiliation (child abandonment and abuse).

“All I have are negative thoughts,” Arthur admits to his therapist. In a crucial session, he begins to leak his homicidal ideation.

In an effort to explain that he is beginning to feel different and that perhaps he’s found a sense of purpose that he’s uncertain of, one that scares him, Arthur adds, “even I didn’t know if I really existed. ” This may have been his confession, or perhaps a fleeting last request for help. His therapist, however, is distracted. She tells him that all funding for Public Health Services are cut and that she will no longer be able to meet with him. This is their last therapy session. Seeing his disappointment, Arthur’s therapist discloses her beliefs about the government, “they don’t give a s**t about people like you, Arthur…” she says, sternly. Then she adds, solemnly, “they don’t really give a s**t about people like me.” Similar to Arthur, mental health providers are dismissed, rejected, and abandoned in a city like Gotham. The effect of this dynamic is dismal: If the people who are responsible for caring for others are not cared about, how can there be any hope of meaningful healing or recovery for anyone?

” This may have been his confession, or perhaps a fleeting last request for help. His therapist, however, is distracted. She tells him that all funding for Public Health Services are cut and that she will no longer be able to meet with him. This is their last therapy session. Seeing his disappointment, Arthur’s therapist discloses her beliefs about the government, “they don’t give a s**t about people like you, Arthur…” she says, sternly. Then she adds, solemnly, “they don’t really give a s**t about people like me.” Similar to Arthur, mental health providers are dismissed, rejected, and abandoned in a city like Gotham. The effect of this dynamic is dismal: If the people who are responsible for caring for others are not cared about, how can there be any hope of meaningful healing or recovery for anyone?

In rapid succession, Arthur’s many protective nets are pulled from underneath him. He loses his job, his therapist, his access to medication, and his relationship with his mother, who represented the single most supportive source of social support for Arthur. At the time he receives the phone call from the Murray Franklin show to appear as a guest, he has already killed four people, including his mother.

At the time he receives the phone call from the Murray Franklin show to appear as a guest, he has already killed four people, including his mother.

Emerging findings in the targeted violence literature support the belief that so-called “warning behaviors” will often include a fixation toward a public figure (e.g., personal cause, violent fantasies, grandiose delusions), and that though the relationship may not be real, such signs should be treated seriously. For Arthur, the intensity of his efforts to further the Murray Franklin quest increases following his first few murders. As said before, he’s “practiced” enough to build internal confidence that he can pull it off with his identified target.

Arthur’s appearance on the Murray Franklin show is filled with uncomfortable tension. As he sits on the very couch he used to fantasize about, Arthur’s guard is actually down. He speaks his mind freely and openly. Arthur tells Murray, quite smugly, “It’s been a rough few weeks since I killed those three guys. ” When it becomes clear that Arthur is not joking, his smiles take on a completely different meaning, and the tension intensifies and fills the studio in the form of hundreds of held breaths. Murray, though, attempts to harness his own calmness and engages in the conversation, which continues to air to Gotham’s viewers, city-wide. Arthur then goes on to essentially deliver his verbal manifesto, starting with, “Everyone is awful these days…” Murray, now more irritated, tells Arthur that there is indeed chaos in the city, and that one reason the people of Gotham are being terrorized is because of Arthur’s murders, his attack on the rich and privileged. At the peak of his speech, Arthur asks Murray directly, in a raised and threatening voice, “What do you get when you cross a mentally ill loner with a society that abandons him and treats him like trash?” Murray, now fearful, commands his team to call the cops, but Arthur continues, now fully escalating: “I’ll tell you what you get – you get what you fucking deserve!” He then pulls out his gun shoots Murray in the forehead, killing him instantly.

” When it becomes clear that Arthur is not joking, his smiles take on a completely different meaning, and the tension intensifies and fills the studio in the form of hundreds of held breaths. Murray, though, attempts to harness his own calmness and engages in the conversation, which continues to air to Gotham’s viewers, city-wide. Arthur then goes on to essentially deliver his verbal manifesto, starting with, “Everyone is awful these days…” Murray, now more irritated, tells Arthur that there is indeed chaos in the city, and that one reason the people of Gotham are being terrorized is because of Arthur’s murders, his attack on the rich and privileged. At the peak of his speech, Arthur asks Murray directly, in a raised and threatening voice, “What do you get when you cross a mentally ill loner with a society that abandons him and treats him like trash?” Murray, now fearful, commands his team to call the cops, but Arthur continues, now fully escalating: “I’ll tell you what you get – you get what you fucking deserve!” He then pulls out his gun shoots Murray in the forehead, killing him instantly.

Incidents of senseless, unforgivable acts of atrocities by lone gunmen have become a part of our cultural andpsychological landscape. The film Joker raises reasonable concerns about how entertainment media influences our current climate as it relates to unpredictable violence, simply because we have too few ways to predict such incidents and we cannot afford to be anything but hyper-vigilant. When exploring the traits of violent behavior, even if fictional, it’s imperative to clarify the overlap between violent crime and mental health. The following facts may help us appreciate the complexities:

1) There isn’t a single psychiatric diagnosis that maps onto “homicidal killer.” An interest in targeted violence alone doesn’t trace to any particular mental health problem. Despite its common usage, the term psychopathis not a clinical diagnosis, but refers to an extreme characterological condition with features of manipulation, selfishness, extreme callousness, violation of social norms and the need for stimulation. It is mostly associated with criminal behavior; not mental illness.

It is mostly associated with criminal behavior; not mental illness.

2) Mental health disorders are brain-related conditions that are quite common. One out of every four of us are affected by mental or neurological disorders at some point in our lives. Among violent killers, less than half have an actual known history of a mental disorder. Despite the largely held public notion that mental disorders account for gun violence, that factor only play one part in a more complex picture.

3) People with mental health problems are more likely to be the victims of violent crime than the perpetrators. As such, it is recommended that persons with mental health disorders are detected early and given access to effective interventions and reliable resources.

4) Having a psychiatric diagnosis is neither necessary nor sufficient as a risk factor for committing an act of mass violence. Similar to Arthur Fleck’s path to destruction, the triggering event for most targeted violence is the acquisition of a lethal weapon, coupled by a significant social, occupational, or personal loss.

Phoenix’s Joker may currently be received as the most frightening manifestation of a modern comic-book villain. He is horrific because he represents today’s fears: What could be more threatening to us right now than a single, white male loner with an untreated mental illness and a loaded gun?

Moreover, Joker was devoid of any fantastical, supernatural comic-book themes that might otherwise pull us out of our discomfort or help us detach from the horror of Phoenix’s realistic Joker. There is little resembling fiction to hold us in safety—no toxic waste dumps, tumbling Batmobiles, or absurd trolley games to separate us from the realness of the story. No, the most chilling line in the film is perhaps the most simple and direct accusation, and it is told in therapy: “You don’t ever hear me.” With this assertion, Arthur is asking his counselor to be vulnerable with him by giving him the space to safely share his feelings of hopelessness, despair, self-hatred and nihilism.

We take a comfortable distance in asking of killers, “what is wrong with them?” when we should be exploring the question “what happened to them?”

Like professor and researcher Brené Brown has said, to be empathetic—to truly offer up a sense of understanding for another person when they’re in pain—we must access something deep within ourselves that is similarly painful. It is easy for us to dismiss Phoenix’s Joker as a maniacal psycho who acts in unpredictable, senseless ways. But the truth is that we can trace nearly every step of his descent into destruction. This is how origin stories go: The Joker is shaped by his traumas, haunted by the void of compassion, and discarded by a failing system. Undoubtedly, employing our empathy for him feels irresponsible and dangerous, and it makes us sense our own fragility, shortcomings and weaknesses. Relating to the Joker is now more subversive than ever. And the truth is, it is unlikely that each of us,at the individual level, can harness enough human compassion to keep everyone around us protected from harm—but we are equally guilty by actively ignoring each other’s pleas to be heard. The hardest aspect to acknowledge in Joker is the viewer’s participation in Arthur’s failed search for connection. Ultimately, Joker is hard to shake off because intrinsic to the storytelling is the direct warning that we may each be contributing to our culture’s mass destruction.

The hardest aspect to acknowledge in Joker is the viewer’s participation in Arthur’s failed search for connection. Ultimately, Joker is hard to shake off because intrinsic to the storytelling is the direct warning that we may each be contributing to our culture’s mass destruction.

Understanding Joker : A Psychological View | by Aditya Vats

Why so serious ?Why so serious? — The Joker, The Dark Knight

There are times when a certain character influences you so much that you totally sink yourself into that character. Of all the villains in the history, the Joker is, without a doubt, one of the most enduring and iconic characters.

But why, despite being a psychopathic, nihilistic murderer, is the character so popular — so loved, even? Why do we see that freakish red scar of a smile on so many t-shirts, posters, and memes?

If you are good at something, never do it for free. — The Joker, The Dark Knight

The Joker is a complicated character. His crimes are not fueled by the desire for money, ambition, or other ordinary motifs. The terror he spreads is ideological and his motivations are philosophical.

His crimes are not fueled by the desire for money, ambition, or other ordinary motifs. The terror he spreads is ideological and his motivations are philosophical.

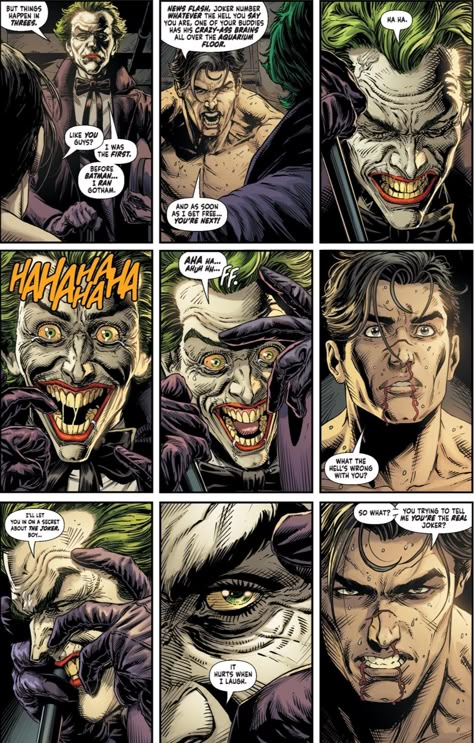

Let’s start by exploring his origin story. The classic one, revealed in the brilliant comic, “The Killing Joke”, is that he was a failed comic trying to make ends meet to support his life with his pregnant wife. He joins a bunch of crooks operating as the Red Hood gang to make easy money. Before the day of the heist, his wife and unborn child die in an accident. He is forced to commit the crime and in the middle of it is met by the Batman. Startled, he falls into a vat of chemicals in the factory where the crime is taking place and washes up outside the factory rendered insane.

It’s a pretty traumatic set of incidents that get him going to where he eventually ends up. The events follow the ‘one bad day’ principle in that all it takes is one lousy day to turn your life upside down. Combined with his exposure to chemicals, it’s the realization that life is inherently unfair and sort of comical that drives him over the edge.

All it takes is one bad day — The Joker, Batman : The Killing Joke

Now let’s try to dig a little deeper into the mind of the Joker.

Carl Jung was an early 20th-century psychologist and psychotherapist, highly influenced by Sigmund Freud. While controversy surrounds his theories today, one idea of his has stuck around that most people regard as true: we all break bad every once in a while.

Jung explained this phenomenon with a concept called the “Shadow.” The Shadow is the part of a person’s psyche they refuse to acknowledge. It’s the part of you that wishes you could beat up your boss and then steal his wallet. It’s the part of you that wishes you could rob a bank in a clown mask, or hurl down a public street in a semi firing off rocket launchers.

It’s the part of you that wants to abandon rules.

According to Jung, a person must recognize those negative impulses to maintain mental health. We must acknowledge the darkness within us but not identify with it. When you don’t acknowledge the Shadow, what happens is that it breaks free, takes on a life of its won and comes back to terrorize you and shatter your “illusory superiority.”

We must acknowledge the darkness within us but not identify with it. When you don’t acknowledge the Shadow, what happens is that it breaks free, takes on a life of its won and comes back to terrorize you and shatter your “illusory superiority.”

Psychologists tell us of what’s called “illusory superiority,” the cognitive bias in us all that causes a person to think far too highly of their positive qualities, and far too little of their negative ones. We like to think of ourselves as noble, honest, and good, especially in comparison to other people. We like to believe we’d never hurt someone, or cause any damage of any kind.

I’m not saying that’s bad, or wrong. I’m not calling people stupid, either. It’s very understandable. It’s just something our minds need to do in order to get through the day.

During the English Civil War of the 1600s, a guy named Thomas Hobbes was a bit ahead of the curve in terms of this “illusory superiority” thing, even if he never exactly recognized it as such. He didn’t agree with most people’s idea that they’re inherently moral and righteous. Instead, he theorized that without enforced rules, humanity would revert right back to a brutish and immoral nightmare of a society — one chaotic, hellish and burning. One in which you’d blow up a ferry full of innocents to stay alive.

He didn’t agree with most people’s idea that they’re inherently moral and righteous. Instead, he theorized that without enforced rules, humanity would revert right back to a brutish and immoral nightmare of a society — one chaotic, hellish and burning. One in which you’d blow up a ferry full of innocents to stay alive.

His most famous work was a horrifically dense tome called Leviathan. It contains perhaps his most famous quote of all, what amounts to his justification for the existence of government:

“…no Society; and which is worst of all, continuall feare, and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.”

Hobbes is saying that without the structured control of the government (what the Joker calls the “schemers”), people become animals. Killers. Thieves. In the 17th-century, this was especially influential and was the major reason Hobbes and guys like him caught on: government, law, and order were absolutely necessary.

Hobbes supported the government for fear of immoral chaos. The Joker, on the other hand, because he’s a downright anarchist psychopath (or psychopathic anarchist), would love nothing more than to see that happen.

Introduce a little anarchy, upset the established order and everything become chaos. I am an agent of chaos. — The Joker, The Dark Knight

It’s why he puts bombs on ferries. It’s why he murders government officials. It’s why he tries to corrupt the one person who’s a symbol that we don’t have to be afraid of people like him. The Joker wants to push a whole city into the wicked gravity of madness and anarchy.

I can’t wait to show you my toys. — The Joker, Suicide Squad

The Joker is simply an outlet for the Shadow, and such a compelling one that that millions have been captivated by him and have vicariously lived out the depravities of their psyche’s Shadow. It is precisely because the Joker bombs and murders and corrupts that so many viewers get a kick out of watching him. He acts in ways that we sometimes wish we could, deep down, and we get a vicarious rush out of seeing him indulge in such behavior, without anyone really getting hurt.

He acts in ways that we sometimes wish we could, deep down, and we get a vicarious rush out of seeing him indulge in such behavior, without anyone really getting hurt.

“Do I really look like a guy with a plan? You know what I am? I’m a dog chasing cars. I wouldn’t know what to do with one if I caught it. You know, I just… do things. — The Joker, The Dark Knight

Though eventually defeated by Batman, it appears the Joker does indeed prove his point. Harvey Dent was Gotham City’s White Knight, the walking epitome of justice, order and nobility. But the Joker turns him into Two Face who then goes on to murder five people, two of them cops, using a chaotic, absurdly meaningless method of flipping a coin to determine their fates. This alone symbolizes the Joker’s philosophy and mission to disrupt civilized society’s sense of “illusory superiority” and to humble it by bringing it back down to its savage roots.

Love him or hate him. But you cannot deny the fact he is probably the most lovable villain of the comic world.

But you cannot deny the fact he is probably the most lovable villain of the comic world.

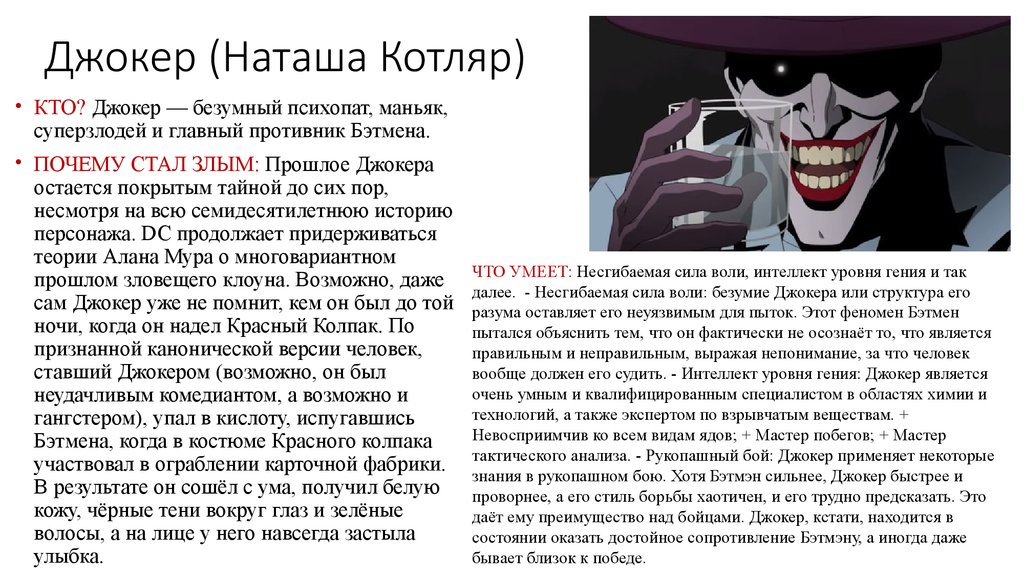

Psychological portrait of the Joker

Initially, I did not want to go to the film "Joker", because clowns do not attract me. Why? Because joking is very, very difficult. If a person does not have enough skills for high-quality and smart jokes, if he is unhappy in his soul, his creations turn out to be evil, stupid or insincere.

At the university in psychology, we went through the emergence of emotions, where we were given an example with monkeys. Like, any grin for monkeys is aggression. Gorillas, for example, when smiling, even cover their teeth with their hands so that, God forbid, their comrades do not misunderstand them. See the fine line between smiling and being angry?

Have you noticed that sometimes a person, in order to hide his pain or aggression from others, becomes “jolly”, tries to joke. But our consciousness is very sensitive, it immediately prompts: “It’s unpleasant for me to look at you. There's something wrong with you, my friend."

There's something wrong with you, my friend."

When Arthur Fleck appeared on the screen, I saw a little downtrodden boy trying to get out. From lack of money, from unemployment, from hopelessness and gloomy thoughts. On TV every now and then there are negative news, my mother is sick at home. His only outlet is the comedy show Murray Franklin. Mom now and then inspires the child: “Smile”, implying that this can bring joy and happiness to the world. Oh, how wrong she is! Her son is missing a lot.

So, what is Arthur missing and what is his problem, or rather disease?

I am a psychologist and have no right to make medical diagnoses, especially according to the plot of the film (there is little information, some information is presented ambiguously in order to interest the audience). One psychotherapist I respect is inclined to think that Arthur Fleck most likely suffers from catatonic schizophrenia. Now I'll tell you what it is.

There are a lot of types of schizophrenia. And the most interesting of them (this was taken into account by the creators of the film) is catatonic. Sometimes it proceeds as catatonic excitement: for example, the patient screams and rushes along the corridor (which we see in the last frames of the film, where Arthur is in a psychiatric hospital), performs absolutely unpredictable actions (kills the "guilty", etc.). At this moment, the patient is insane, very dangerous to others and needs to be isolated.

And the most interesting of them (this was taken into account by the creators of the film) is catatonic. Sometimes it proceeds as catatonic excitement: for example, the patient screams and rushes along the corridor (which we see in the last frames of the film, where Arthur is in a psychiatric hospital), performs absolutely unpredictable actions (kills the "guilty", etc.). At this moment, the patient is insane, very dangerous to others and needs to be isolated.

Sometimes this schizophrenia manifests itself in the form of a catatonic stupor, when the patient is practically unavailable for contact. He sits or lies, his gaze is fixed on emptiness, in especially severe cases, when there is a maximum regression of the psyche, such a patient cannot drink and eat, he relieves himself in bed.

We can observe a variant of catatonic stupor in the last frames of the film, where Arthur "talks" to a psychiatrist. He is not motivated, not disposed to talk, answers in monosyllables, smokes. He also shows signs of negativity. To the doctor's question: "Why are you laughing?", he replies: "You will not understand." Negativism for a schizophrenic patient is something of a trap. They give him a hand, and he pulls it away, they ask him, but he is silent or answers in monosyllables.

He also shows signs of negativity. To the doctor's question: "Why are you laughing?", he replies: "You will not understand." Negativism for a schizophrenic patient is something of a trap. They give him a hand, and he pulls it away, they ask him, but he is silent or answers in monosyllables.

A little about psychological age and psychopathology.

Remember, in one of my articles I talked about a woman who was offended by me and instantly turned into a little girl: her lips trembled, her voice changed to a three-year-old child, and the text that she uttered looked like the judgment of a little girl. So, when we are offended or we get into stress, we return to the age when we found ourselves in such a situation for the first time.

People with personality problems are divided into three groups: neurotics, border guards and psychotics (the latter includes schizophrenia). The psychological age of psychotics is from 0 to 1–1.5 years. Here, such a kind of adult uncle Arthur walks around, lives an adult life, but only gets into a stressful situation, and even worse, in a number of stressful situations, and his psyche disintegrates, regresses to the age when he was disliked.

What happens when you break up? Psychological death. With psychological death, a person loses the boundary between himself and the world around him, between his mental ideas about himself and the world around him.

An adult healthy person senses this boundary well. For example, “I want to eat. This is happening to me, not to the world” or “It has become cold. It's happening to the world, not to me."

In a psychotic, this state is mixed. At this moment, he experiences terrible sensations, because he does not feel himself. Where does the edge go? Disappears because mom couldn't shape it.

A healthy, clear, strong border for a baby is formed by the mother up to 1–1.5 years. It is not for nothing that they say that a mother during this period should be very stable (daily routine), very reliable (if you want to eat - I will feed you, if you get dirty - I will change the diaper, you are sad - I will tell a funny rhyme), very stress-resistant (yelling, you won’t let me sleep - don’t I’ll take it out on you, it’s not your fault), but also healthy and adequate. Mom needs to constantly be in a strong symbiosis with her child. And then by the age of 1 he will have a normal psychological birth.

Mom needs to constantly be in a strong symbiosis with her child. And then by the age of 1 he will have a normal psychological birth.

Arthur's mother, if I understood correctly from the plot, was also a schizophrenic. And she, due to her mental instability, was not able to provide the child with adequate care and satisfaction of his early needs. The child was somehow able to form a thin border for himself, but it was torn under stress.

If a child after 1 year and beyond is poorly cared for, beaten, almost all of his ideas about the world around him are bad. Remember how Arthur Fleck said at the doctor's office: "All my thoughts are negative"? And it is right. Because his thoughts show a real-life experience: he was beaten, not loved, chained to a battery, inspired by inadequate ideas, double messages. And Arthur is forced to maintain a very fragile line between "I" and "a practically bad world in which there is very little good."

A psychotic who is stuck between the ages of 1 and 1. 5 years is one of the most helpless, socially disadvantaged segment of the population, because he does not have the social skills that parents should form: understand, recognize and express their emotions, communicate effectively, influence circumstances.

5 years is one of the most helpless, socially disadvantaged segment of the population, because he does not have the social skills that parents should form: understand, recognize and express their emotions, communicate effectively, influence circumstances.

Arthur cannot defend his boundaries in a healthy way, protect himself from being fired, make a real acquaintance with a girl he likes, cannot come up with a full-fledged, logical comic performance. What is left for him? Resignedly endure all the circumstances that happen to him. But he can divide events into good and bad and fill his ideas about the world with them. The girl smiled - I'll put a coin in a good piggy bank, the boss fired me - I'll put a coin in a bad one.

Arthur, as a psychotic, has only two primitive defensive skills he needs to maintain a thin line between self and world. First, the projection: “I'm not bad. I'm good. It's someone else bad." Secondly, the denial of reality: "She cares about me, she is my girlfriend, we have love with her. "

"

How else does he maintain this boundary? With the manic decision: "I am good and the world is good." In the film: “I am a good viewer, the presenter loves me, my mother is good, we all watch it together.” This “all good” state cannot last long, because the world constantly reminds of the opposite: Fleck is beaten, fired, laughed at. Then he is forced to maintain a flimsy connection between himself and the bad world. It's called the paranoid decision: "I'm good. I have a pistol. I will kill the bad host. I will kill a bad colleague. And I'll leave the good."

When this stops working and ideas about good things run out in the psyche, then the depressive decision turns on: "I am bad, and the world is bad." Then the person has suicidal thoughts.

Why did Arthur's bad piggy bank overflow? Because he was trapped. People did not accept him, subconsciously realizing that "something is wrong with this person."

Even the psychotherapist at the very beginning of the film, who chose the wrong method of treatment (treated him as a neurotic, kept a distance in communication, asked questions, asked to keep a diary), made a big mistake, saying: “The world is like me and like you, not needed"

A psychotherapist can bring a psychotic out of a painful state by giving him that love, compassion, support, concern, comfort and attention that he did not receive in infancy. To show that there can be more good things in his idea of the world. It is easy technically, but morally difficult (the psychotic has a lot of aggression, specialists are taught to work with it). By the way, Arthur fantasy created these missing pluses in the form of an image of a neighbor girl, with whom he was never able to establish a real relationship.

To show that there can be more good things in his idea of the world. It is easy technically, but morally difficult (the psychotic has a lot of aggression, specialists are taught to work with it). By the way, Arthur fantasy created these missing pluses in the form of an image of a neighbor girl, with whom he was never able to establish a real relationship.

What does the film teach? Compassion. The fact that you can’t condemn people without knowing what a thorny path they have gone through, and you can’t hurt someone who is already hurting so much.

Thanks to all my friends, acquaintances and beloved editors for convincing me to watch this film.

Joker. Psychological Review - Movies & Series on DTF

4240 views

I'm not going to disassemble the acting game, staging the frame. Let's leave that to other film reviewers. Here - solely an attempt to get into the head of the most famous movie villain of the DC Universe, embodied by Joaquin Phoenix in 2019year.

PS. I do not pretend to be the ultimate truth. As they say, I am a couch psychologist, I see it that way.

!!! Spoilers!!! I have them!!!

First Look

How does Arthur Fleck appear before us in the first half of the film?

We see a deeply unhappy, insecure character forcibly stretching his lips into a happy smile. He is infantile, shy, unable to stand up for himself. His movements are comically ridiculous. He smokes one cigarette after another. In moments of severe stress, an involuntary tremor of the limbs is manifested. And laughter. Oh that laugh. I will return to this topic a little later.

From a conversation with a social worker, we learn that he has already been a client of a psychiatric clinic more than once. He complains of feeling unwell, “negative thoughts.” He appears before us in a state of severe, clinical depression, his suicidal tendencies are obvious even to a non-specialist. does not receive an adequate response.

When we are faced with depression, frustration? Generally speaking, this is a state when our expectations do not coincide with the real picture of the world. What expectations of Arthur Fleck turned out to be unfulfilled? Let's figure it out.

Environment

The first minutes of the film eloquently describe Arthur's whole life - being a kind and good-natured person, he sincerely tries to amuse and bring joy to people, and in return receives only anger and cruelty.

Artur works as a funny clown animator in a small entertainment agency. It is curious that the clown, in one of its meanings, is not only an artist of the clownery genre, but also a “laughing mark” - an object of bullying and humiliation. Such is the future prince of the underworld.

At work, colleagues do not have much respect for him - they are afraid of him, they consider him strange. The boss is absolutely intolerant of him. When one of his colleagues gives Arthur a gun (a real "Chekhov's gun"), a logical question arises about the sincerity of his intentions - did he sincerely try to help Arthur or wanted to bring a colleague objectionable to the team to a prison term, giving a deadly weapon with real, live ammunition to a person with pronounced deviations?

The only person who warmly relates to Arthur Fleck is his undersized colleague, who is also noticeably different from the others, and is also bullied because of his features. But they are not close and almost do not communicate with each other.

But they are not close and almost do not communicate with each other.

It is curious that children are in fact the only characters in the film who do not show aggression towards the eternally laughing eccentric, they do not hang labels and openly perceive the world, thereby liberating Arthur, allowing him to express himself and show emotions without fear, show them speeches.

During and after work, he encounters aggression and rejection from people who are completely unfamiliar - bystanders, fellow travelers in the subway, marginalized teenagers. After work - goes home, to the society of an unhealthy elderly mother.

So, day after day, being in an aggressive environment for himself, he lives his life. Society rejects him, because people try to avoid strange people, so different from them. “The worst thing about mental illness is that people expect you to act like you don't have it,” he writes in his diary.

But Artur does not give up - he regularly visits the social worker, takes medication, keeps the aforementioned diary. He tries to fight his devils, does not want to be different from others, passionately craves love and recognition. In the absence of real ones, ephemeral ones will do.

He tries to fight his devils, does not want to be different from others, passionately craves love and recognition. In the absence of real ones, ephemeral ones will do.

That is why he instantly becomes emotionally attached to his neighbor, who smiled politely but sincerely at him in the elevator. After all, she is the only one who "noticed" him, showed a grain of warmth, without condemnation and mockery.

As we can see, although negative, but still reaction, Arthur regularly receives from society. What is Arthur talking about, subsequently shouting more than once that no one notices him?

Childhood

The roots of problems always come from childhood. The hero's childhood is revealed to both us and Arthur at the same time through Arkham's medical notes on his mother.

From the memoirs we learn the tragic story of little Arthur Fleck.

He grows up in the company of a mentally ill mother and (at least for a while) her sadistic roommate. He is regularly subjected to severe beatings and humiliation on the part of the latter and complete indifference, tacit consent to what is happening on the part of the mother.

He is regularly subjected to severe beatings and humiliation on the part of the latter and complete indifference, tacit consent to what is happening on the part of the mother.

He grows up, becoming a victim who is unable to fight back his offenders. He cannot escape from personal hell, he is not even able to express sincere feelings about what is happening, therefore, he drags learned helplessness with him in the future through the years. An interesting fact is that in the future, Arthur displaces painful memories of childhood from his psyche, not returning to them, but again raising them from the recesses of memory only when reading Penny's anamnesis.

Decades later, Penny's indifference to her son continues. They still do not have a trusting and warm relationship, even if Arthur tries to build them. She prefers to ignore Arthur's obvious problems, her only focus being her own letters to her former employer. When Arthur shares his joy that he had a date, but she ignores it, when he talks about his ultimate dream of being a comedian, she gently stomps on her, planting a seed of doubt in him. “Where did you get what you can do?” she asks in an innocent voice.

“Where did you get what you can do?” she asks in an innocent voice.

She refuses to accept reality. “He never cried, he was always a cheerful and joyful boy,” she says of her downtrodden, beaten, bullied child by her stepfather, when asked why Arthur was found beaten and chained to a radiator. “My joy,” she calls her always gloomy son. And don't let the sight of "God's dandelion" deceive you - Penny Fleck continues to be a latent sadist.

We perceive the first half of the film as the Joker's mother through the prism of Arthur's perception of her - she is a sick elderly woman whom he must take care of, whom he must not upset. He practically spoon-feeds her, bathes her in the bathroom, carries her in his arms, and therefore we have the complete impression that Penny is paralyzed from the waist down. But in the dance scene, we see that this is not at all the case - she is able to move on her own, and she is not that old either (assuming that Arthur is a little over 30 years old at the time of the story, then she should not be more than 65- ti). Why does a man who is able to look after himself allow his son to completely serve himself and his needs?

Why does a man who is able to look after himself allow his son to completely serve himself and his needs?

Whether the adopted child is Arthur or the natural son of Penny Fleck and Thomas Wayne, there is no direct answer in the film, there are arguments in favor of both versions. And therefore, whether Arthur's disease is of an organic nature - and is the result of a brain injury, genetically transmitted from a mentally ill mother, or became a deplorable result of childhood psychotrauma (or maybe it's a combination of all factors) - is also an open question.

Fantasies and main dream

One way or another, being unable to break through the iron curtain of his mother's alienation, thereby losing the support of his own person, not having a clear example of his father's figure, an example to follow, Arthur is forced to dive into the world of his fantasies, embodying an ideal picture in them world, making up for their unfulfilled desires in reality.

It is almost physically painful to watch the future Joker's fantasy of performing on his favorite TV show - the unsatisfied need of Arthur's inner child for love and recognition from the father figure in the face of the presenter is so clearly conveyed.

His other fantasy in the form of a neighbor personifies his need for support, at the same time reflecting hidden thoughts about the correctness of his own actions, becoming a living embodiment of self-justification. Curious is the fact that the object of desire, the main source of care becomes a dark-skinned girl so unlike her blond mother (not racism, but a statement of fact!).

Even his chosen profession as a comedian is not a desire to make people laugh. Laughter inherently represents a deep positive emotion, the emotion of approval. When we laugh at the jokes of others, we simultaneously show them our sympathy, form affection. Through laughter and jokes, Arthur tries to generate positive emotions that he does not have.

Not having an example of a person who loves him and shows him sympathy, Artur tries to figure out how to get it, to develop an algorithm, following which people can like him. He sincerely tries to understand what is considered funny and what is not, writing down jokes and comments on them with the reaction of society in a personal diary of experiences (which is significant). He visits stand-ups of novice talents, watching the reaction of others and trying to imitate them, not to differ from them as much as possible, because his own sense of humor is not at all the same as that of the others.

He visits stand-ups of novice talents, watching the reaction of others and trying to imitate them, not to differ from them as much as possible, because his own sense of humor is not at all the same as that of the others.

Despite Arthur's difficult childhood, his repressed anger and aggression at the injustice surrounding him, there is no place for violence and revenge in his fantasies - only endless, unconditional love and acceptance, which he had not had all his life.

The man who laughs

Arthur's essentially positive emotion appears as deeply negative, painful, suffocating and painful.

He grew up in an atmosphere of absolute dislike, rejection, and meanwhile indifference on the part of the closest and dearest person, and not knowing how to achieve these feelings, he did what his mother expected of him. "You must always smile," the future crime prince of Gotham clarifies as a child, in the hope that in this way he can win her sympathy. He learns to hide real emotions by suppressing himself, hiding his real self behind a smiling mask.

He learns to hide real emotions by suppressing himself, hiding his real self behind a smiling mask.

Inappropriate laughter manifests itself at moments of deepest stress, at moments of excessive anxiety, at the moment of experiencing the strongest feelings. This is a disguised manifestation of Arthur's true emotions and feelings - his anger, shame, emotions, even sadness, which he actively suppresses.

Remember the scene after the beating of Arthur by teenagers at the beginning of the film. He is scolded by the boss, to which he demonstrates behavior that is atypical for unfair accusations - instead of the natural emotion of anger, he smiles (rather cringely). And only when no one sees him, he gives out a real emotion.

Concealment of true impulses, excessive control of "It", life under the mask leads to the loss of a sense of one's own "I". “I'm not sure that I exist,” says Arthur, since he is real, his true feelings and impulses are not expressed outside.

People who doubt their own existence, as a rule, try to get out of this state in all possible ways, it is so painful. The simplest let - to show aggression, external or internal. Finally show emotion. The "parent's" internal prohibition against directing aggression towards others pushes him to direct it towards himself - hence Arthur's depressive and suicidal impulses.

The simplest let - to show aggression, external or internal. Finally show emotion. The "parent's" internal prohibition against directing aggression towards others pushes him to direct it towards himself - hence Arthur's depressive and suicidal impulses.

It is noteworthy that after the release of the inner beast outside, with the complete cessation of attempts to control oneself, pathological laughter, which torments Arthur the whole picture, no longer appears.

First kill or transformation

Arthur Fleck accumulates a huge unexpressed aggression against the injustice surrounding him, but he is not able to throw it out, constantly restraining himself. But it is infinitely impossible to fill the vessel, the last drop will spill all the contents out, without a trace - the "spring effect" will work, and the person will either finally break down or give a response proportional to the force of pressure.

The attack on him on the subway is the last straw for Arthur. As you know, there is no more dangerous beast than a beast crammed into a corner. Especially if he has a weapon. And, finally, he finds the strength to fight back, for the first time taking out his accumulated anger on living people. This murder is the logical outcome of the rebellion of a driven person.

As you know, there is no more dangerous beast than a beast crammed into a corner. Especially if he has a weapon. And, finally, he finds the strength to fight back, for the first time taking out his accumulated anger on living people. This murder is the logical outcome of the rebellion of a driven person.

Of course, we can refer to the necessary self-defense, but is it? It is difficult to argue with the murder of the first two employees of the Wayne company, but Arthur is already deliberately and purposefully sent to kill the third, releasing many more bullets into a person trying to escape than was necessary for protection.

The reaction of a person after a murder is usually very eloquent, through which we understand the true attitude of the killer to what happened. The first reaction of Arthur Fleck is to run away, to hide from what happened, the fear of being caught in the act. He does not feel regret, sadness either immediately after the act, or after. He suffers neither from guilt, nor from Dostoyevsky's fear of persecution.

It is symbolic that he commits his first crime under a mask, which helps him to abstract from what is happening, close his real self and safely try on the image of “another Arthur”.

The scene in the toilet is very expressive, his movements in the dance are light and slow, devoid of any tension. For the first time, he finds the desired calmness, demonstrates absolute peace, receives a long-awaited liberation from the framework that binds him. The murder was a real relaxation for Arthur, after which he received genuine satisfaction and deep self-confidence (and possibly real excitement) - it is after the first murder that he decisively goes to the girl next door, which he did not dare to do before. It is the first murder that becomes the starting point for the irreversible transformation of Arthur Fleck into the Joker.

Life begins to play with new colors, his relationship with a girl develops, he begins to smile sincerely. Only after the murder, he decides to try himself in his favorite role.

A daring crime in the metro inevitably attracts public attention, but its causes are misinterpreted by society, finding a lively response in the hearts of the masses. It and the subsequent inaccurate statement of the candidate for mayor of Gotham Thomas Wayne become an occasion for rallies and street riots, giving vent to the accumulated aggression and discontent of the inhabitants (does it remind you of anything?). Arthur, still convinced that no one notices him, sees a stormy response to his action, and, albeit anonymously for the time being, attracts the desired attention of people.

Policy

It is worth saying a few words about politics here. Of course, the picture touches on political topics more than once, but the film is not about it at all.

Gotham has always been a dark and unpromising place, with a huge number of economic and social problems: from the strongest social stratification to the highest level of crime (along with useless police work). Accordingly, without the accumulated human dissatisfaction with all this, it is problematic to imagine real popular unrest. Any uprising needs worthwhile reasons, and reasons (like the murder of three workers of the “upper” class), as you know, will be found.

Accordingly, without the accumulated human dissatisfaction with all this, it is problematic to imagine real popular unrest. Any uprising needs worthwhile reasons, and reasons (like the murder of three workers of the “upper” class), as you know, will be found.

Arthur himself has always been far from politics, which he directly mentions several times during the picture. When you live in a personal tragedy day after day, it becomes not up to political claims. Let's remember the scene with throwing the clown mask - a symbol of popular unrest - into the trash after it was no longer needed for disguise. He joins the protesters only because he is attracted by the outburst of emotions that the crowd demonstrates, and which, accordingly, can be manifested independently. In the crowd, the sense of responsibility for oneself and for one's actions decreases, a feeling of unlimited one's own strength appears. Let's add here the heady feeling of power from the fact that you, without expecting it, have become a powerful incentive for what is happening. In the end, the crowd, and especially the angry crowd, creates chaos and confusion, which Arthur's soul craves, so tired of living right.

In the end, the crowd, and especially the angry crowd, creates chaos and confusion, which Arthur's soul craves, so tired of living right.

Politics here appears only as a toolkit, thanks to which the formation of the Joker as such took place, because what is a leader without minions? The Joker, so desperately in need of love and recognition, simply finds a fertile audience, his faceless "like-minded people." He does not care who will applaud him, as long as there are such. And therefore, unwittingly, he becomes a symbol of the fight against injustice (as, in turn, Batman).

Subsequent Kills, Rebirth

Once having solved your problems by killing another, it is no longer possible to stop on your own. Perception is definitively deformed, and it no longer finds another way out except for subsequent murders.

Especially if your fantasy ideal world starts to crack. And the reasons for that begin to pour on Arthur like from a cornucopia.

Thanks to his mother, he learns the truth (?) about his origin and acquires a new fantasy about a rich and influential father. In an effort to verify the truth of this fantasy, he travels from Wayne Mansion to Arkham Asylum. And each goal on this path hits Arthur's already unhealthy psyche with a butt.

In an effort to verify the truth of this fantasy, he travels from Wayne Mansion to Arkham Asylum. And each goal on this path hits Arthur's already unhealthy psyche with a butt.

His mother ends up in the hospital, Artur is on the heels of an investigation into an accident in the subway, due to staff cuts, the social service can no longer deal with him (and this means depriving him of his medicines). His main fantasy that the performance in the stand-up club was successful is shattered by harsh realities (interestingly, the fact that the performance turns out to be a failure is forced out of his memory, as well as traumatic memories from childhood). He is ridiculed by the idol in which he saw his father, disappointed in his own dream, in himself. And at the same time, angry.