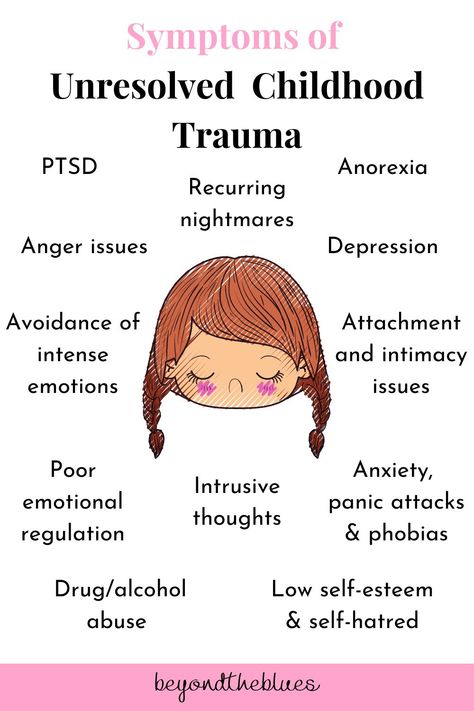

Childhood trauma disorder

Understanding Child Trauma - What is Childhood Trauma?

Fast Facts

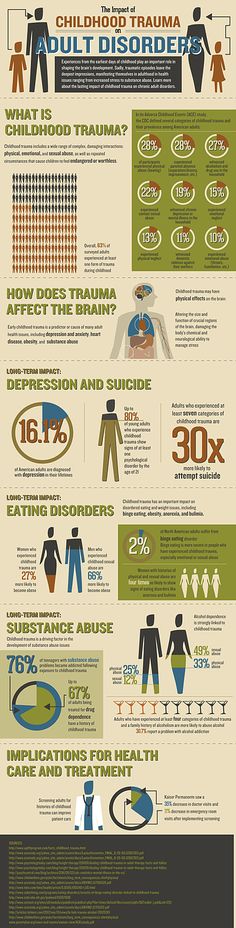

At least 1 in 7 children have experienced child abuse and/or neglect in the past year, and this is likely an underestimate. In 2019, 1,840 children died of abuse and neglect in the United States.

Each day, more than 1,000 youth are treated in emergency departments for physical assault-related injuries.

In 2019, about 1 in 5 high school students reported being bullied on school property in the last year.

8% of high school students had been in a physical fight on school property one or more times during the 12 months before the survey.

Each day, about 14 youth die from homicide, and more than 1,300 are treated in emergency departments for violence-related injuries.

It’s important to recognize the signs of traumatic stress and its short- and long-term impact.

The signs of traumatic stress may be different in each child. Young children may react differently than older children.

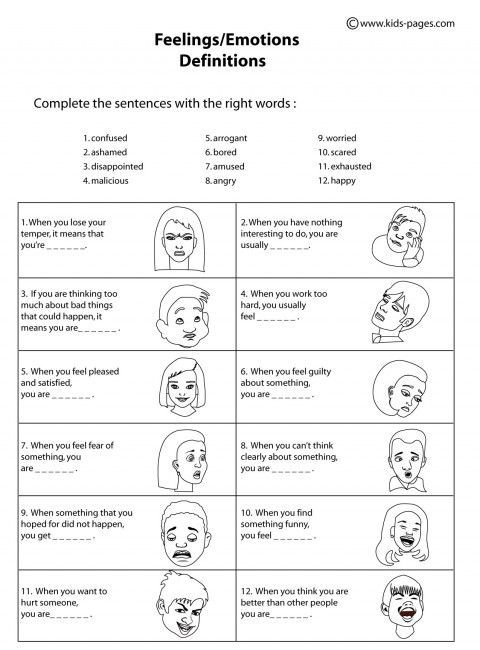

Preschool Children

- Fear being separated from their parent/caregiver

- Cry or scream a lot

- Eat poorly or lose weight

- Have nightmares

Elementary School Children

- Become anxious or fearful

- Feel guilt or shame

- Have a hard time concentrating

- Have difficulty sleeping

Middle and High School Children

- Feel depressed or alone

- Develop eating disorders or self-harming behaviors

- Begin abusing alcohol or drugs

- Become involved in risky sexual behavior

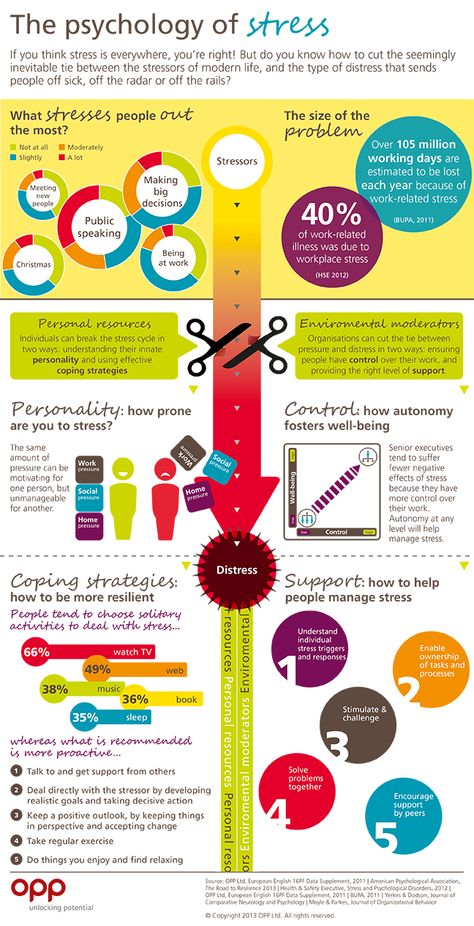

The Body's Alarm System

Everyone has an alarm system in their body that is designed to keep them safe from harm. When activated, this tool prepares the body to fight or run away. The alarm can be activated at any perceived sign of trouble and leave kids feeling scared, angry, irritable, or even withdrawn.

Healthy Steps Kids Can Take to Respond to the Alarm

- Recognize what activates the alarm and how their body reacts

- Decide whether there is real trouble and seek help from a trusted adult

- Practice deep breathing and other relaxation methods

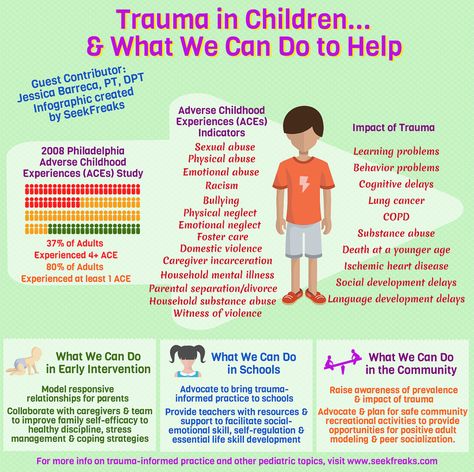

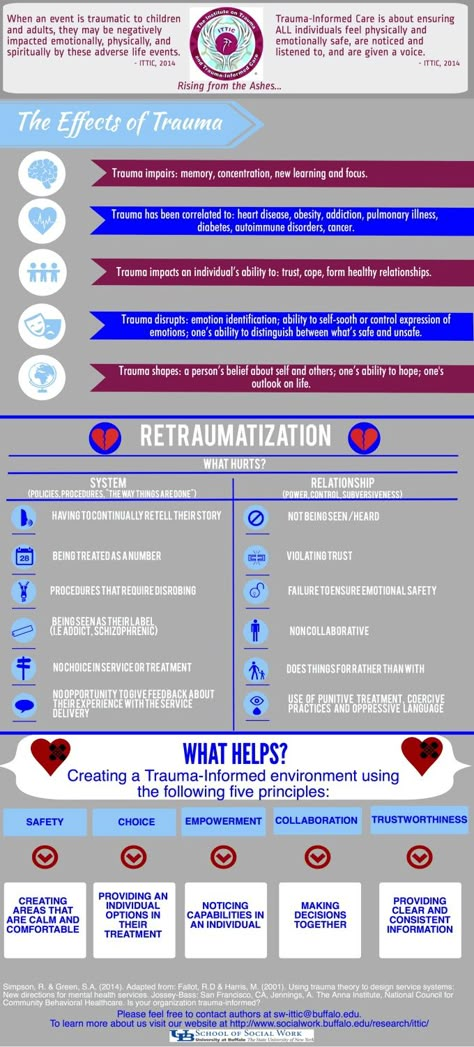

Impact of Trauma

The impact of child traumatic stress can last well beyond childhood. In fact, research has shown that child trauma survivors may experience:

In fact, research has shown that child trauma survivors may experience:

- Learning problems, including lower grades and more suspensions and expulsions

- Increased use of health and mental health services

- Increase involvement with the child welfare and juvenile justice systems

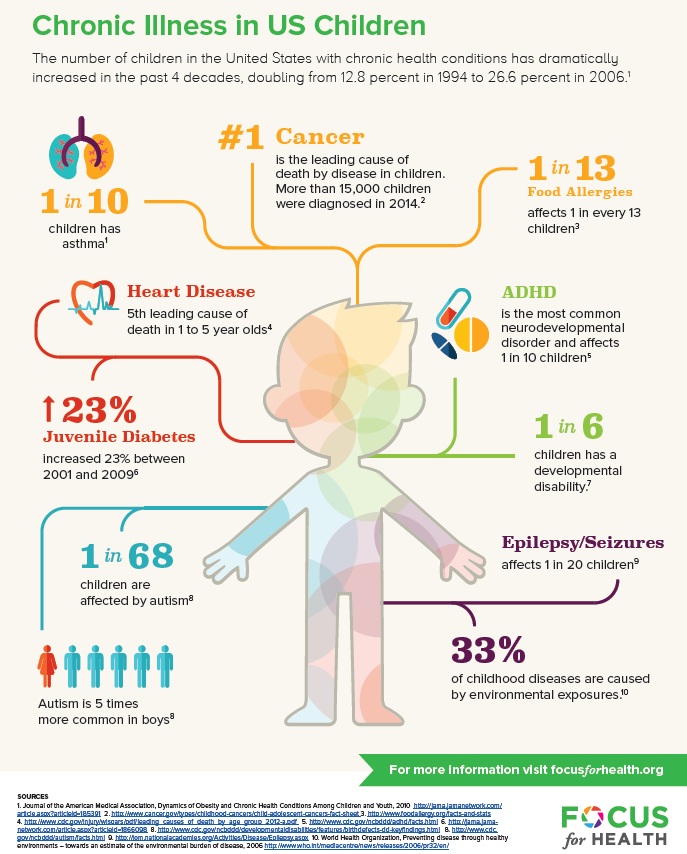

- Long-term health problems (e.g., diabetes and heart disease)

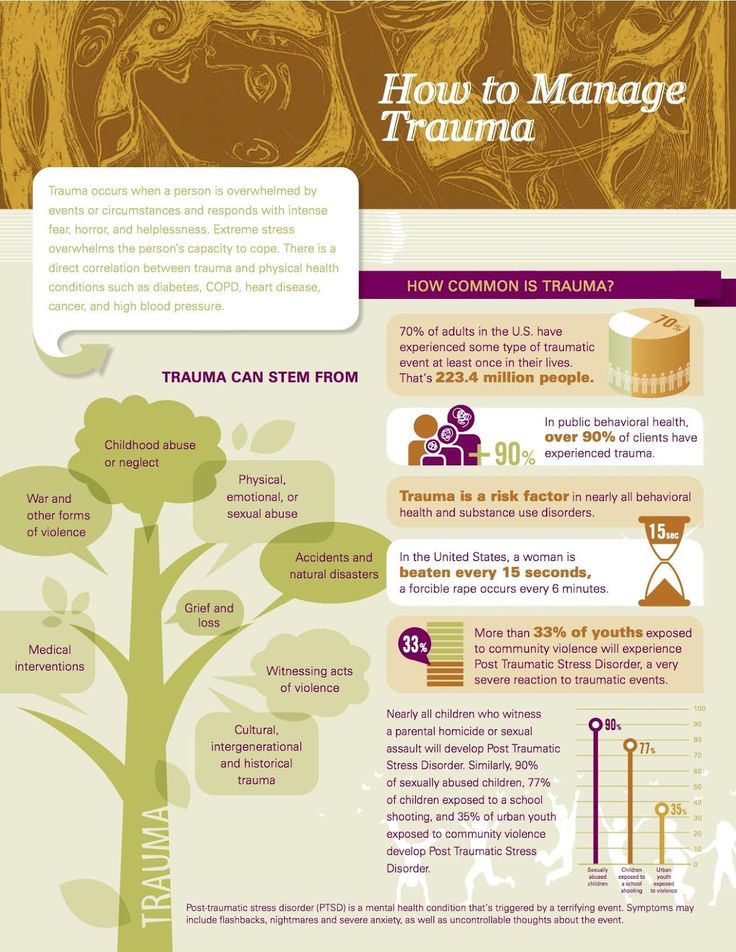

Trauma is a risk factor for nearly all behavioral health and substance use disorders.

There is hope. Children can and do recover from traumatic events, and you can play an important role in their recovery.

A critical part of children's recovery is having a supportive caregiving system, access to effective treatments, and service systems that are trauma informed.

Get Help Now

SAMHSA Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network: Get Help Now

Healthcare Toolbox: Basics of Trauma-Informed Care

Not all children experience child traumatic stress after experiencing a traumatic event. With support, many children are able to recover and thrive.

With support, many children are able to recover and thrive.

As a caring adult and/or family member, you play an important role.

Remember To:

- Assure the child that he or she is safe.

- Explain that he or she is not responsible. Children often blame themselves for events that are completely out of their control.

- Be patient. Some children will recover quickly while others recover more slowly. Reassure them that they do not need to feel guilty or bad about any feelings or thoughts.

- Seek the help of a trained professional. When needed, a mental health professional trained in evidence-based trauma treatment can help children and families cope and move toward recovery. Ask your pediatrician, family physician, school counselor, or clergy member for a referral.

Visit the following websites for more information:

- Trauma and Violence

- The National Child Traumatic Stress Network

Recognizing and Treating Child Traumatic Stress

Learn about the signs of traumatic stress, its impact on children, treatment options, and how families and caregivers can help.

- Types of Traumatic Events

- Signs of Child Traumatic Stress

- Impact of Child Traumatic Stress

- What Families and Caregivers Can Do to Help

- Treatment for Child Traumatic Stress

- More Ways to Find Help

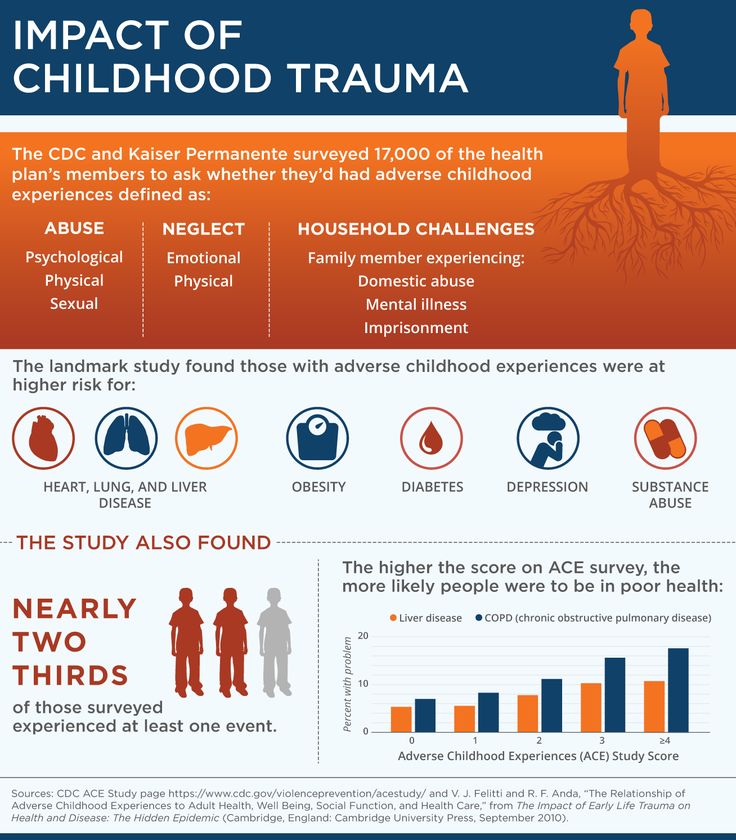

Types of Traumatic Events

Childhood traumatic stress occurs when violent or dangerous events overwhelm a child’s or adolescent’s ability to cope.

Traumatic events may include:

- Neglect and psychological, physical, or sexual abuse

- Natural disasters, terrorism, and community and school violence

- Witnessing or experiencing intimate partner violence

- Commercial sexual exploitation

- Serious accidents, life-threatening illness, or sudden or violent loss of a loved one

- Refugee and war experiences

- Military family-related stressors, such as parental deployment, loss, or injury

In one nationally representative sample of young people ages 12 to 17:

- 8% reported a lifetime prevalence of sexual assault

- 17% reported physical assault

- 39% reported witnessing violence

Also, many reported experiencing multiple and repeated traumatic events.

It is important to learn how traumatic events affect children. The more you know, the more you will understand the reasons for certain behaviors and emotions and be better prepared to help children and their families cope. Learn more about the types of trauma and violence and types of disasters.

Signs of Child Traumatic Stress

The signs of traumatic stress are different in each child. Young children react differently than older children.

Preschool Children

- Fearing separation from parents or caregivers

- Crying and/or screaming a lot

- Eating poorly and losing weight

- Having nightmares

Elementary School Children

- Becoming anxious or fearful

- Feeling guilt or shame

- Having a hard time concentrating

- Having difficulty sleeping

Middle and High School Children

- Feeling depressed or alone

- Developing eating disorders and self-harming behaviors

- Beginning to abuse alcohol or drugs

- Becoming sexually active

For some children, these reactions can interfere with daily life and their ability to function and interact with others.

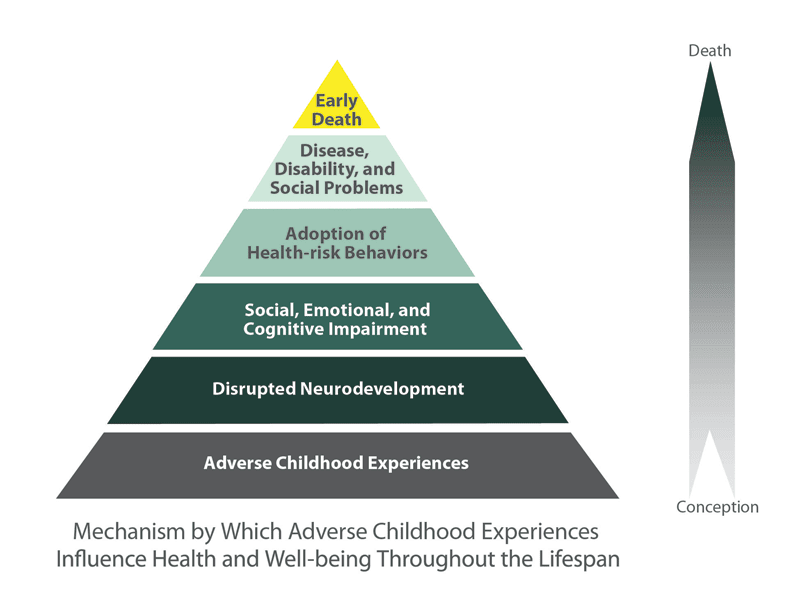

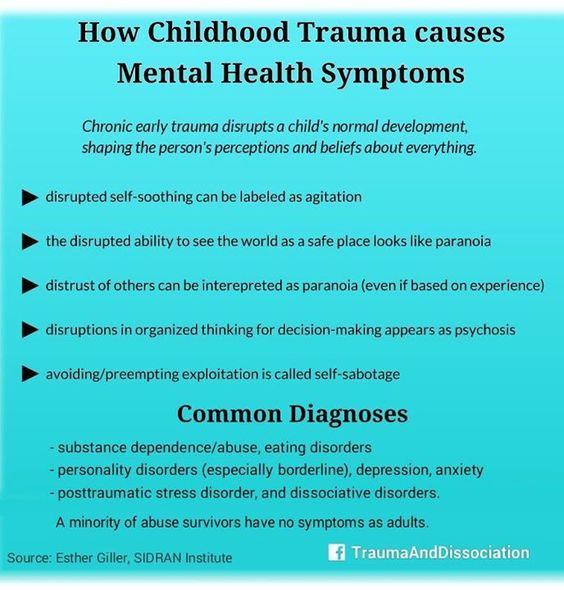

Impact of Child Traumatic Stress

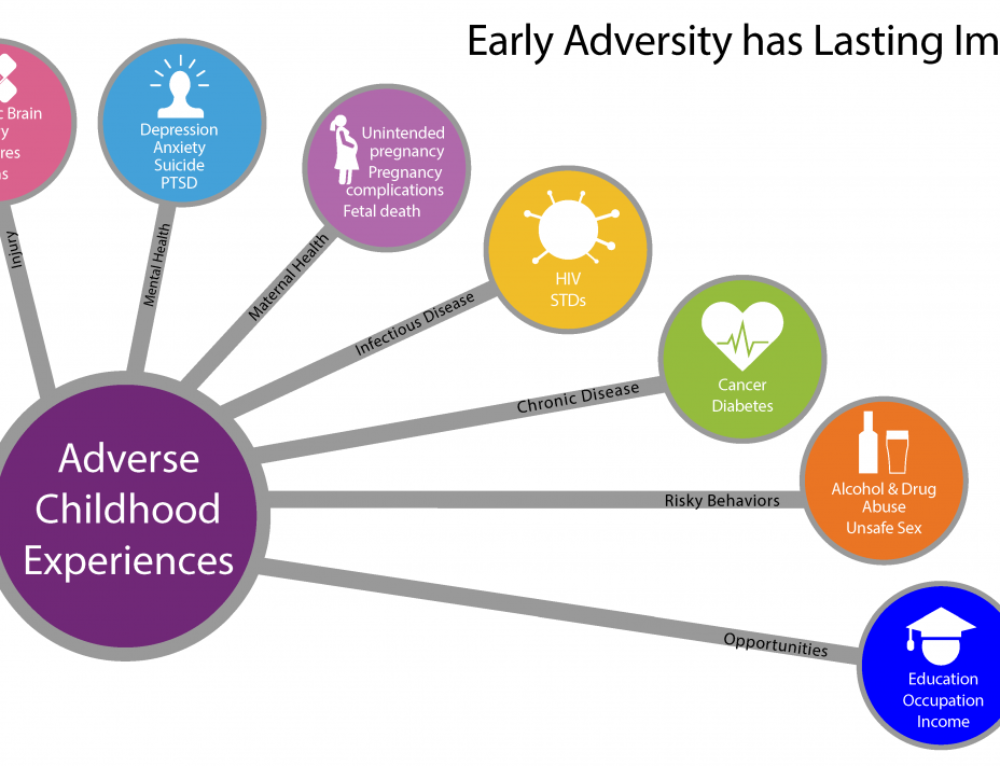

The impact of child traumatic stress can last well beyond childhood. In fact, research shows that child trauma survivors are more likely to have:

- Learning problems, including lower grades and more suspensions and expulsions

- Increased use of health services, including mental health services

- Increased involvement with the child welfare and juvenile justice systems

- Long term health problems, such as diabetes and heart disease

Trauma is a risk factor for nearly all behavioral health and substance use disorders.

What Families and Caregivers Can Do to Help

Not all children experience child traumatic stress after experiencing a traumatic event, but those who do can recover. With proper support, many children are able to adapt to and overcome such experiences.

As a family member or other caring adult, you can play an important role. Remember to:

- Assure the child that he or she is safe.

Talk about the measures you are taking to get the child help and keep him or her safe at home and school.

Talk about the measures you are taking to get the child help and keep him or her safe at home and school. - Explain to the child that he or she is not responsible for what happened. Children often blame themselves for events, even those events that are completely out of their control.

- Be patient. There is no correct timetable for healing. Some children will recover quickly. Others recover more slowly. Try to be supportive and reassure the child that he or she does not need to feel guilty or bad about any feelings or thoughts.

Review NCTSI’s learning materials for parents and caregivers, educators and school personnel, health professionals, and others.

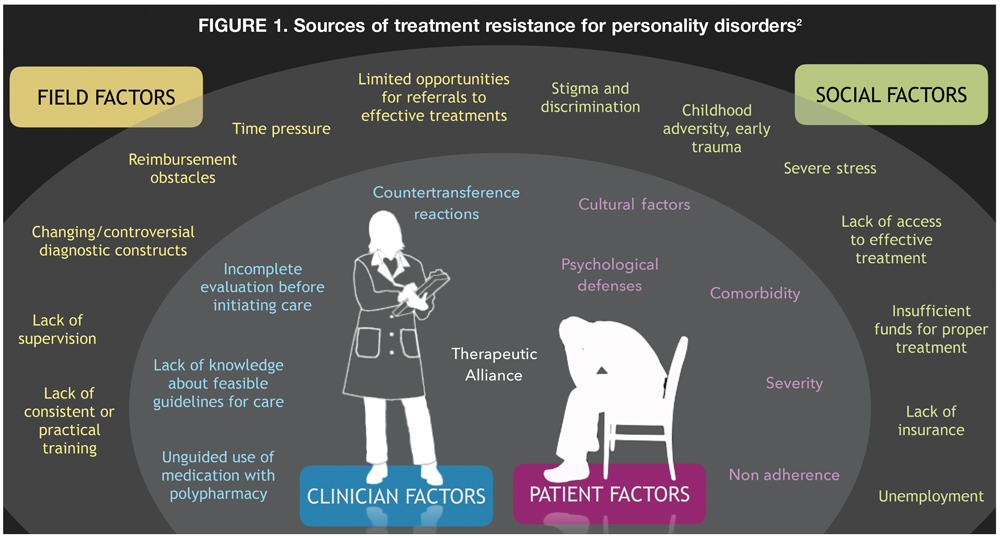

Treatment for Child Traumatic Stress

Even with the support of family members and others, some children do not recover on their own. When needed, a mental health professional trained in evidence-based trauma treatment can help children and families cope with the impact of traumatic events and move toward recovery.

Effective treatments like trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapies are available. There are a number of evidence-based and promising practices to address child traumatic stress.

Each child’s treatment depends on the nature, timing, and amount of exposure to a trauma.

Review Effective Treatments for Youth Trauma – 2004 (PDF | 55 KB) at the National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

Families and caregivers should ask their pediatrician, family physician, school counselor, or clergy member for a referral to a mental health professional and discuss available treatment options.

More Ways to Find Help

Many U.S. agencies and other groups offer research and support related to child traumatic stress.

Government Websites

- Division of Violence Prevention and Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study at CDC

- Office for Victims of Crime at the Department of Justice

- National Center for PTSD at the Department of Veterans Affairs

- Pediatric Trauma and Critical Illness Branch at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

- Coping With Traumatic Events at the National Institute of Mental Health

Other Organizations

- American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children

- Children’s Mental Health Report at the Child Mind Institute

- HealTorture.

org

org - International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies

- National Children's Advocacy Center

- Sidran Institute

Post-traumatic stress disorder in young children

Alexandra De Young, PhD, Justin Kenardi, PhD

National Research Center for Disorders and Rehabilitation, Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland, Australia

(English). Translation: June 2015

Introduction

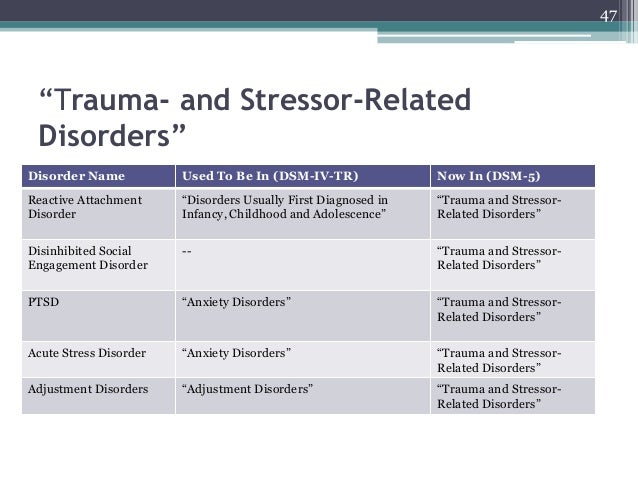

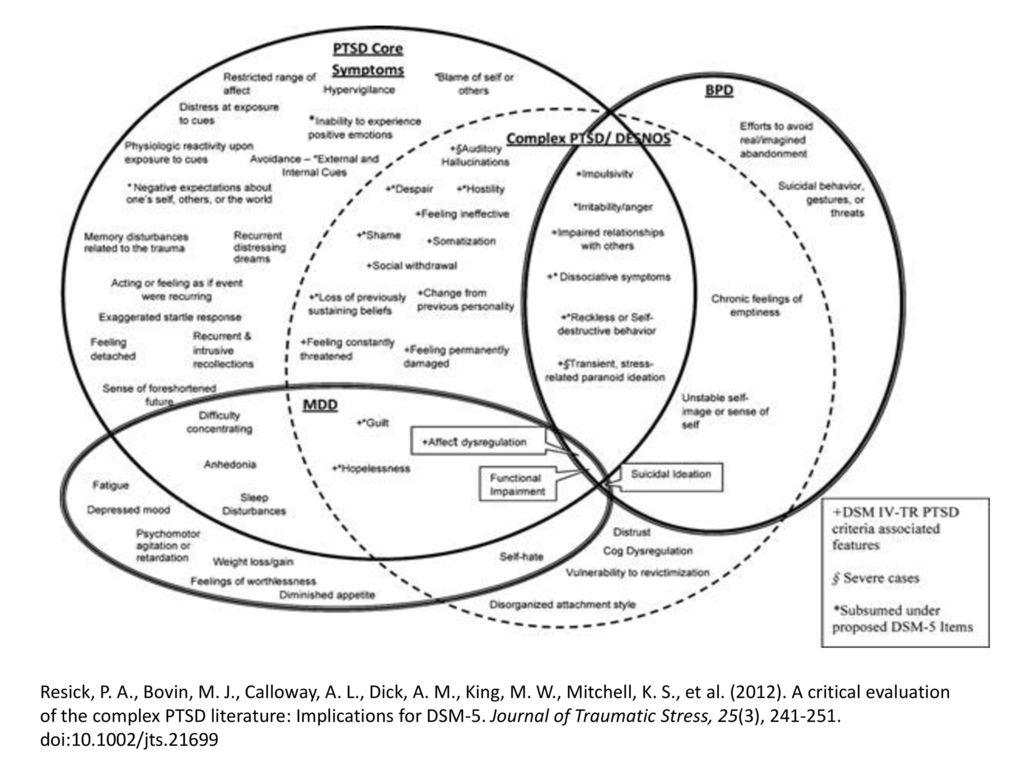

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is one of the most severe and debilitating disorders associated with trauma. According to research, young children, as well as older children and adolescents, commonly exhibit three of the traditional symptoms of PTSD: re-experiencing the event (through nightmares or acting out traumatic events), seeking to avoid being reminded of the event, and psychological overexcitation (for example, , irritability, sleep disturbance, unmotivated shivering). 1 However, research suggests that the PTSD features listed in The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 2 do not adequately reflect the specificity of onset of symptoms in infants and preschool children. The Guidelines also underestimate the number of children experiencing post-traumatic stress and subsequent deterioration in health. 3 Accordingly, new research is encouraging the inclusion of a subtype of PTSD occurring in preschool children in the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. 4.5

1 However, research suggests that the PTSD features listed in The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 2 do not adequately reflect the specificity of onset of symptoms in infants and preschool children. The Guidelines also underestimate the number of children experiencing post-traumatic stress and subsequent deterioration in health. 3 Accordingly, new research is encouraging the inclusion of a subtype of PTSD occurring in preschool children in the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. 4.5

Frequency, course and consequences of reactions to trauma months after the traffic accident (RTA) 6 or burn injuries 7 ; in 14.3–25% of cases, within two months after receiving various types of injuries (for example, burns, bullet wounds, road accidents, injuries during sports or during the game), 8.9 in 10% of cases, within six months after an accident or burn injuries 6. 8 and in 13.2% of cases - within 15 months on average after burn injuries.10 Signs of age-specific PTSD appear in 26-60% 1,3,11 cases as a result of physical or sexual abuse. Our study has shown that young children develop depression, separation anxiety disorder, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and specific phobias due to burn injuries, 8 , and that these disorders are highly co-morbid symptoms of PTSD.

8 and in 13.2% of cases - within 15 months on average after burn injuries.10 Signs of age-specific PTSD appear in 26-60% 1,3,11 cases as a result of physical or sexual abuse. Our study has shown that young children develop depression, separation anxiety disorder, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and specific phobias due to burn injuries, 8 , and that these disorders are highly co-morbid symptoms of PTSD.

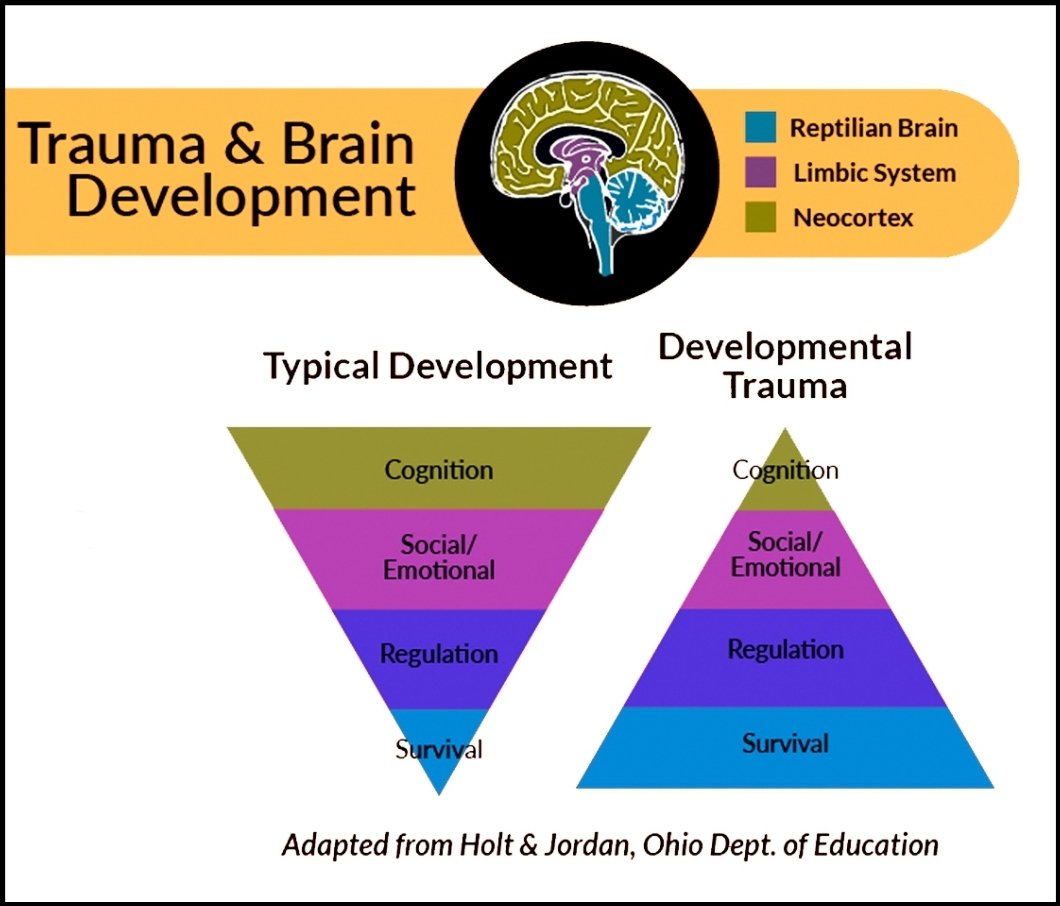

Studies in children of all ages have shown that, if left untreated, PTSD can develop into a chronic, debilitating form. 8,12,13 The results of this study are troubling given the fact that neurophysiological systems in young children, including stress modulation and emotion regulation, are still in rapid development. 14 In addition, childhood trauma is associated with permanent structural 15 and functional 16 brain damage, as well as with the onset of psychiatric disorders, 17 health risk behavior and related physical health status in adults. 18 Thus, trauma in early childhood can have much more severe consequences on the developmental trajectory than trauma sustained later in development.

18 Thus, trauma in early childhood can have much more severe consequences on the developmental trajectory than trauma sustained later in development.

The role of parents

When working with children, it is very important to realize that the trauma itself and the child's reaction to it is a serious test for parents, which can also become a source of chronic stress. Research has shown that approximately 25% of parents experience clinically elevated levels of acute stress, PTSD, anxiety, depression, and stress within the first six months of a child's trauma. 19-21 Although most parents remain relatively resilient and their stress levels return to clinical normal over time, parental distress during the acute stress stage contributes to the development and persistence of traumatic symptoms in affected children. 19,20,22

It is generally accepted that the quality of the attachment of children and parents to each other, the mental health of parents and their parenting actions are key factors influencing a child's recovery from trauma. 14,23,24 For young children, relationships with parents are especially important because children do not have sufficient adaptive capacity to regulate strong emotions on their own. Thus, they depend on a sensitive and emotionally open educator who can help them regulate their emotional response in times of distress. 14.23 In addition, young children especially rely on their parents' emotions to understand how to interpret or respond to an event. In the future, children can imitate their parents' reaction to fear and their inadequate adaptive reactions. 25 Parents can also directly influence the child's contact with the trauma memories (for example, avoiding discussion of what happened) and thus hinder the child's adaptation to the event. 25

14,23,24 For young children, relationships with parents are especially important because children do not have sufficient adaptive capacity to regulate strong emotions on their own. Thus, they depend on a sensitive and emotionally open educator who can help them regulate their emotional response in times of distress. 14.23 In addition, young children especially rely on their parents' emotions to understand how to interpret or respond to an event. In the future, children can imitate their parents' reaction to fear and their inadequate adaptive reactions. 25 Parents can also directly influence the child's contact with the trauma memories (for example, avoiding discussion of what happened) and thus hinder the child's adaptation to the event. 25

The influence of adverse psychological reactions on the relationship between children and parents, the development of traumatic symptoms in the child, combined with the mental suffering of parents, are important arguments for paying more attention to the needs of parents in order to reduce their level of experience and stimulate their ability to support children in difficult times. Adequate measures aimed at alleviating the mental illness of the child and parents, as well as improving relations between them, will have a beneficial effect on the process of inhibiting the development of post-traumatic reactions in parents and children. However, there is only preliminary evidence to support these types of interventions during an exacerbation, and more research is needed on this issue.

Adequate measures aimed at alleviating the mental illness of the child and parents, as well as improving relations between them, will have a beneficial effect on the process of inhibiting the development of post-traumatic reactions in parents and children. However, there is only preliminary evidence to support these types of interventions during an exacerbation, and more research is needed on this issue.

Early prevention and correction measures

Unfortunately, most children and their parents who experience psychological difficulties after trauma are not diagnosed with characteristic symptoms, as a result of which both children and parents do not receive adequate support. Taking into account the prevalence of injuries, as well as the fact that early childhood is a sensitive period of brain development, it is necessary to introduce effective measures that can reduce the risk of developing chronic post-traumatic stress reactions in children and parents. It is advisable to take such measures in an environment with an increased risk of stress reactions, for example, in a medical institution. This solution would reduce the risk of traumatic stress reactions or even prevent them by conducting an examination and implementing a program of preventive measures. 26 Early detection of severe symptoms and appropriate action in families at risk will help prevent problems from occurring and entrenching, or at least minimize the impact of these problems on the child, family and society. However, the primary task is to learn to distinguish between categories of patients experiencing a short-term mental disorder and those at risk of developing chronic PTSD, 13 without creating additional overload for filled medical institutions. Psychometrically verified examination methods for very young children do not exist, which is a significant shortcoming in this area.

This solution would reduce the risk of traumatic stress reactions or even prevent them by conducting an examination and implementing a program of preventive measures. 26 Early detection of severe symptoms and appropriate action in families at risk will help prevent problems from occurring and entrenching, or at least minimize the impact of these problems on the child, family and society. However, the primary task is to learn to distinguish between categories of patients experiencing a short-term mental disorder and those at risk of developing chronic PTSD, 13 without creating additional overload for filled medical institutions. Psychometrically verified examination methods for very young children do not exist, which is a significant shortcoming in this area.

To date, most research has focused on the treatment of chronic PTSD rather than early prevention of its symptoms. Both in children's and adult literature, there is no data on which categories of patients need preventive measures at an early stage, what duration and content these measures should have. 27 To date, systematic reviews suggest that continuous cognitive-behavioral trauma therapy (CBT) is most effective when administered within the first three months after the event. 27

27 To date, systematic reviews suggest that continuous cognitive-behavioral trauma therapy (CBT) is most effective when administered within the first three months after the event. 27

Research involving children suggests that preventive action based on incident information up to two weeks after an injury can reduce anxiety symptoms in children at 1 28 and 6 months after the event developments. 29 In addition, Landolt et al received a positive response to a single session of preventive therapy aimed at managing symptoms of depression and behavioral problems in a group of preteens (7-11 years old) affected by road traffic accidents. 30 Berkowitz and colleagues 31 created the only individualized prevention program (4 sessions for a child with a parent/guardian, including diagnostics, psychological self-help training and coping skills) for children 7-17 years old. The program has shown its effectiveness in reducing the manifestations of PTSD and various post-traumatic symptoms.

However, there are no published studies on the effectiveness of preventive post-traumatic psychological interventions for young children (under six years of age). However, Scheering's research has shown that 12 sessions of cognitive-behavioral therapy, built in accordance with a special plan for PTSD, conducted with children aged 3-6 years who experienced a variety of traumatic events, showed their appropriateness and effectiveness in reducing existing post-traumatic stress symptoms. 32

Few studies look at the preventive therapy component for adults to prevent post-trauma disorders in children. Kenardy et al found that psychological self-help training provided to parents within 72 hours of an accident was effective in reducing parental post-traumatic symptoms up to 6 months after the accident. 28 Melnyk et al. 33 examined the effectiveness of a prevention program in parents of children aged 2-7 years under close pediatric supervision. The researchers found that parents in the prevention group had markedly reduced levels of stress, depression, and PTSD symptoms, and their children experienced fewer internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems after discharge.

The researchers found that parents in the prevention group had markedly reduced levels of stress, depression, and PTSD symptoms, and their children experienced fewer internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems after discharge.

Evidence-based recommendations for the prevention of PTSD in young children require research. However, Landolt et al., based on the results of a recent meta-analysis, argue that early preventive measures help identify children at risk. These activities include several sessions of training in psychological self-help, individual adaptation skills, involvement of parents in the process and familiarization with various forms of traumatic phenomena. 34

Advice for parents, services and policy

The phenomenon of post-traumatic stress disorder in young children has received little attention so far. Health care providers should monitor children more closely for signs of post-traumatic stress disorder. This may require training and retraining of staff. Mass standardized screening is ideal, but diagnosing groups of children at risk may be more cost-effective. In addition, any screening program must be integrated with a clinical setting that provides opportunities for appropriate care. Parental distress is a significant factor influencing post-traumatic reactions in children. However, in medical institutions this criterion is given insufficient attention. The reason for this may be the fact that the distress of the parents against the background of the child's injury may not reach the level of clinical diagnosis, or the fact that it is customary to pay more attention to the needs of the child than the family as a whole. 22 Caregivers should pay more attention to the fact that the consequences of trauma can have a more serious impact on the family system as a whole.

Mass standardized screening is ideal, but diagnosing groups of children at risk may be more cost-effective. In addition, any screening program must be integrated with a clinical setting that provides opportunities for appropriate care. Parental distress is a significant factor influencing post-traumatic reactions in children. However, in medical institutions this criterion is given insufficient attention. The reason for this may be the fact that the distress of the parents against the background of the child's injury may not reach the level of clinical diagnosis, or the fact that it is customary to pay more attention to the needs of the child than the family as a whole. 22 Caregivers should pay more attention to the fact that the consequences of trauma can have a more serious impact on the family system as a whole.

Literature

- Scheeringa, M., et al., New findings on alternative criteria for PTSD in preschool children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , 2003.

42(5): p. 561-570.

42(5): p. 561-570. - American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, (4th edition, Text Revision). 2000, Washington, DC: Author.

- Scheeringa, M.S., et al., Two approaches to the diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder in infancy and early childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , 1995. 34(2): p. 191-200.

- Scheeringa, M.S., C.H. Zeanah, and J.A. Cohen, PTSD in Children and Adolescents: Toward an Empirically Based Algorithm. Depression and Anxiety , 2011. 28(9): p. 770-782.

- De Young, A.C., J.A. Kenardy, and V.E. Cobham, Diagnosis of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Preschool Children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology , 2011. 40(3): p. 375-384.

- Meiser-Stedman, R., et al., The posttraumatic stress disorder diagnosis in preschool- and elementary school-age children exposed to motor vehicle accidents.

American Journal of Psychiatry , 2008. 165(10): p. 1326-1337.

American Journal of Psychiatry , 2008. 165(10): p. 1326-1337. - Stoddard, F.J., et al., Acute stress symptoms in young children with burns. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , 2006. 45(1): p. 87-93.

- De Young, A.C., et al., Prevalence, comorbidity and course of trauma reactions in young burn-injured children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry , 2012. 53(1): p. 56-63.

- Scheeringa, M.S., et al., Factors affecting the diagnosis and prediction of PTSD symptomatology in children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry , 2006. 163(4): p. 644-651.

- Graf, A., C. Schiestl, and M.A. Landolt, Posttraumatic Stress and Behavior Problems in Infants and Toddlers With Burns. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 2011. 36(8): p. 923-931.

- Levendosky, A.A., et al., Trauma symptoms in preschool-age children exposed to domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence , 2002.

17(2): p. 150-164.

17(2): p. 150-164. - Scheeringa, M.S., et al., Predictive validity in a prospective follow-up of PTSD in preschool children. J ournal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , 2005. 44(9): p. 899-906.

- Le Brocque, R.M., J. Hendrikz, and J.A. Kenardy, The Course of Posttraumatic Stress in Children: Examination of Recovery Trajectories Following Traumatic Injury. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 2010. 35(6): p. 637-645.

- Carpenter, G.L. and A.M. Stacks, Developmental effects of exposure to Intimate Partner Violence in early childhood: A review of the literature. Children and Youth Services Review , 2009. 31(8): p. 831-839.

- Carrion, V.G., C.F. Weems, and A.L. Reiss, Stress predicts brain changes in children: A pilot longitudinal study on youth stress, posttraumatic stress disorder, and the hippocampus. Pediatrics , 2007. 119(3): p. 509-516.

- Perry, B.D., et al., Childhood trauma, the neurobiology of adaptation, and ''use-dependent'' development of the brain: How ''states'' become ''traits''.

Infant Mental Health Journal , 1995. 16(4): p. 271-291.

Infant Mental Health Journal , 1995. 16(4): p. 271-291. - Green, J.G., et al., Childhood Adversities and Adult Psychiatric Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication I Associations With First Onset of DSM-IV Disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry , 2010. 67(2): p. 113-123.

- Felitti, V.J., et al., Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults - The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 1998. 14(4): p. 245-258.

- De Young, A.C., Psychological impact of burn injury on young children and their parents: Implications for diagnosis, assessment and treatment (Unpublished Doctoral dissertation), 2011, School of Psychology, University of Queensland: Brisbane.

- Landolt, M.A., et al., The mutual prospective influence of child and parental post-traumatic stress symptoms in pediatric patients. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry , 2012.

53(7): p. 767-774.

53(7): p. 767-774. - Hall, E., et al., Posttraumatic stress symptoms in parents of children with acute burns. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 2006. 31(4): p. 403-412.

- Le Brocque, R.M., J. Hendrikz, and J.A. Kenardy, Parental response to child injury: Examination of parental posttraumatic stress symptom trajectories following child accidental injury. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 2010. 35(6): p. 646-655.

- Lieberman, A.F., Traumatic stress and quality of attachment: Reality and internalization in disorders of infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal , 2004. 25(4): p. 336-351.

- Scheeringa, M.S. and C.H. Zeanah, A relational perspective on PTSD in early childhood. Journal of Traumatic Stress , 2001. 14(4): p. 799-815.

- Nugent, N.R., et al., Parental posttraumatic stress symptoms as a moderator of child's acute biological response and subsequent posttraumatic stress symptoms in pediatric injury patients.

Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 2007. 32(3): p. 309-318.

Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 2007. 32(3): p. 309-318. - Kazak, A.E., et al., An integrative model of pediatric medical traumatic stress. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 2006. 31(4): p. 343-355.

- Roberts, N.P., et al., Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Multiple-Session Early Interventions Following Traumatic Events. American Journal of Psychiatry , 2009. 166(3): p. 293-301.

- Kenardy, J., et al., Information-provision intervention for children and their parents following pediatric accidental injury. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry , 2008. 17(5): p. 316-325.

- Cox, C.M., J.A. Kenardy, and J.K. Hendrikz, A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Web-Based Early Intervention for Children and their Parents Following Unintentional Injury. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 2010. 35(6): p. 581-592.

- Zehnder, D., M. Meuli, and M.A. Landolt, Effectiveness of a single-session early psychological intervention for children after road traffic accidents: a randomized controlled trial.

Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health , 2010. 4: p. 7.

Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health , 2010. 4: p. 7. - Berkowitz, S.J., C.S. Stover, and S.R. Marans, The Child and Family Traumatic Stress Intervention: Secondary prevention for youth at risk of developing PTSD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry , 2011. 52(6): p. 676-685.

- Scheeringa, M.S., et al., Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in three-through six year-old children: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry , 2011. 52(8): p. 853-860.

- Melnyk, B.M., et al., Creating opportunities for parent empowerment: Program effects on the mental health/coping outcomes of critically ill young children and their mothers. Pediatrics , 2004. 113(6): p. E597-E607.

- Kramer, D.N. and M.A. Landolt, Characteristics and efficacy of early psychological interventions in children and adolescents after single trauma: a meta-analysis.

European journal of psychotraumatology , 2011. 2.

European journal of psychotraumatology , 2011. 2.

For citation:

De Young A, Kenardi D. Post-traumatic stress disorder in young children. In: Tremblay RE, Buavan M, Peters RDeV, eds. Rapi RM, ed. Topics. Encyclopedia of early childhood development [online]. https://www.encyclopedia-deti.com/trevozhnost-i-depressiya/ot-ekspertov/posttravmaticheskoe-stressovoe-rasstroystvo-u-detey-mladshego. Published: March 2013 (English). Viewed on December 12, 2022

Text copied to clipboard ✓

Stress and post-traumatic condition in children

We treat children according to the principles of evidence-based medicine: we choose only those diagnostic and treatment methods that have proven their effectiveness. We will never prescribe unnecessary examinations and medicines!

Make an appointment via WhatsApp

Prices Doctors

The first children's clinic of evidence-based medicine in Moscow

No unnecessary examinations and drugs! We will prescribe only what has proven effective and will help your child.