Jealousy of others

Why Am I Jealous of Others’ Success?

We’ve all experienced feelings of envy and jealousy.

Maybe you’re jealous of others’ success at work. Perhaps you’re envious of your friend’s great relationship, or their seemingly fabulous life.

In this day and age, when people share so much on social media, it’s easy to look at photos and Facebook announcements and feel a twinge of FOMO (fear of missing out) or concern that the realities of your life don’t quite measure up.

Why do we feel jealous of others’ good fortune? Why do we covet our friends’ lives? Is jealousy really so bad? And what should we do to clear up those green-with-envy moments?

The Haves and the Have-Not’sThere are a lot of ways to look at jealousy. If we view it from the perspective of psychologist Alfred Adler, jealousy stems from our inferiority complex.

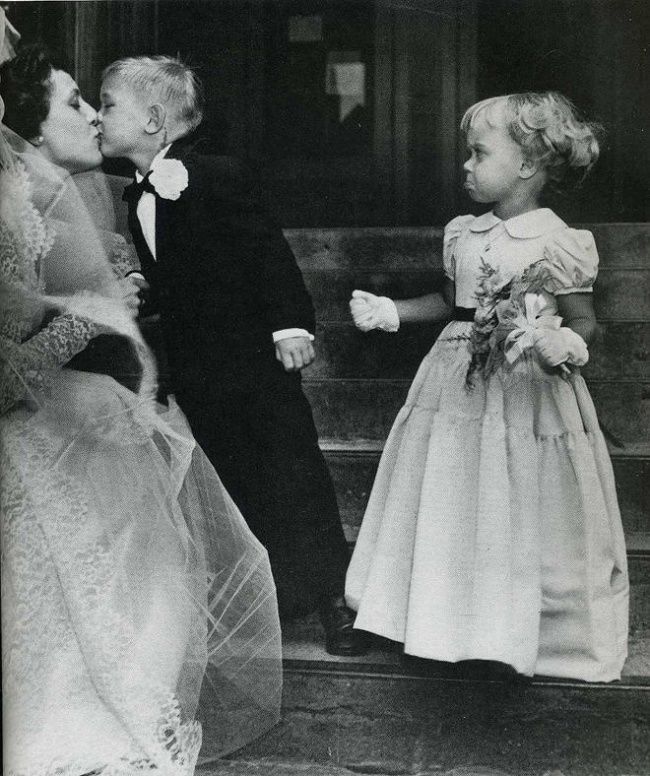

Everyone has an inferiority complex. If you think someone doesn’t have one, you don’t know him or her well enough. Feelings of inferiority are embedded deep in our psyche. It’s part of growing up and navigating our world. As children, we’re fighting our siblings to get our parents’ attention. We’re fighting our way through a big world when we’re small. We’re learning about our limitations. These feelings are a natural part of being human.

When you view the success of those around you, you may interpret their accomplishment to mean you’re somehow inadequate.

Someone else was chosen over you. They’re one up, and you’re one down. Even if you tell yourself it’s not a contest or competition, you may still feel twinges of envy. You may wonder if they’re better than you are, or what they did to deserve what you didn’t receive.

These feelings are the trigger for jealousy.

Jealousy is the feeling of “I want what she’s having.” It’s an indicator you’re feeling less-than-okay about yourself. Even if you’re generally confident, jealousy still happens. Those feelings of being left out or left behind translate into jealousy. Jealousy is sparked by not feeling okay about some aspect of your self or your situation.

Those feelings of being left out or left behind translate into jealousy. Jealousy is sparked by not feeling okay about some aspect of your self or your situation.

Jealousy is a deeply ingrained emotion in humans. We want what others have because we need resources to survive (and want comforts to thrive). If we look back through history, jealousy has always been part of us. Hera, the wife of Zeus, jealously turned his mistress Lo into a heifer in Greek mythology. Themes and teachings in Christianity, Judaism, Islam, and Buddhism all speak to jealousy as a damaging emotion. It seems as long as humans have existed, so has jealousy.

Why Do I Get Jealous of Others?Growth mindset is a big buzz topic these days and for a good reason. When we shift to a growth mindset, we start to view others’ success as inspiring. We may still want what others have, but instead of seeing it as “being left out,” we look at as motivation to achieve success.

A growth mindset looks at success and says, “What would it take for me to achieve something similar? How can I do that too? What would I need to do or learn to gain the same success?” Then, we learn from the success of others and use it to propel us forward.

Inspiration is a very healthy way to look at someone else’s success (but it’s still perfectly okay to admit we’re humans who feel jealous from time to time).

Bob and I will see writers who create an instant best-seller, and although we may feel jealous for a moment, we shift it into a lesson. “What did they do right? How do we do what they’re doing to promote their book? What can we learn from their experience?” These lessons are beneficial in our future success, and we’ve both found so many takeaways from looking at what other professionals do well.

Jealousy is normal. It’s fine. Jealousy comes up. But rather than dwelling on it and beating yourself up as inadequate, learn how to tap into it and mine it as a resource.

You may feel jealous of someone’s life (especially when you see beautiful vacation photos online, for example) but in reality, it may not even be something you want. You may discover you don’t even want what your friends have or wouldn’t want the same experiences. You may find an aspect of their achievement you value, but other pieces you don’t desire.

If you don’t truly value or covet what others have, then love that they have it and celebrate for them. If you do value what they have and want it for yourself, look at the lessons to extract from their experience. Apply them to your actions and figure out how to create more of the same success in your life.

What Are You Really Jealous Of?I recently met with a man who said he feels intimidated and jealous of the other men in his leadership group. He told me, “They’re all big guys, earning a lot of money. I’m jealous of them.”

We started exploring where the feelings were coming from and discussing his values. He has a very service-filled life. His relationship with his wife is intimate and beautiful. He’s a good family man who serves those around him. He teaches others and gives back. He’s crafted his life toward his values and filled it with what matters to him. He doesn’t care so much about money, or he would steer his life toward it.

He has a very service-filled life. His relationship with his wife is intimate and beautiful. He’s a good family man who serves those around him. He teaches others and gives back. He’s crafted his life toward his values and filled it with what matters to him. He doesn’t care so much about money, or he would steer his life toward it.

As we discussed his feelings about the guys in his group, he said, “Wait a minute! These aren’t even my values!” He started to realize if he wanted to earn more money, then fine, he could learn from his leadership group and follow a similar path. But feeling envious of others was denying his values. He values service, intimacy, and relationships and has done a beautiful job at building those aspects in his life. He was feeling jealous of the rich and powerful, but he wasn’t really honoring his values.

I consulted on an article in a women’s magazine on how to turn feelings of jealousy into motivation.

Jealousy rises when your own deeper yearnings aren’t being met, and you become envious of what another person has, how they are, or what they do.

Jealousy is a clue to what it is we really want, and what we’re yearning for. Jealousy helps us narrow our focus and tap into our core values.

Whether we’re jealous of a friend’s promotion, new car, or attractive partner, we should realize their situation doesn’t take away from our own. We may think we want EXACTLY what they have (this is especially true when it comes to romantic relationships) but look at the aspects of their situation causing your jealousy.

One fantastic aspect of life is there’s enough love, success, and happiness to go around. When someone else has something in his or her life you want, look at the lesson. What is it you really want? How do you achieve the same love, success, or happiness in your own life and your situation?

When harnessed correctly, jealousy is a powerful motivator to help us clarify our desires and move us toward getting what we really want in life.

For more ways to get what you want in your life, visit the Wright Foundation. Join us for an upcoming More Life Training, where you’ll connect with other growth-minded people. We’re also proud to announce that many of our courses are available online for download. Don’t miss this great opportunity and a special, introductory price.

Join us for an upcoming More Life Training, where you’ll connect with other growth-minded people. We’re also proud to announce that many of our courses are available online for download. Don’t miss this great opportunity and a special, introductory price.

About the Author

Dr. Judith Wright is a media favorite, sought-after inspirational speaker, respected leader, peerless educator, bestselling author, & world-class coach.

She is a co-founder of The Wright Foundation and the Wright Graduate University.

Loving the content and want more? Follow Judith on Facebook, Twitter and Pinterest!

Liked this post and want more? Sign up for updates – free!

The Wright Foundation for the Realization of Human Potential is a leadership institute located in Chicago, Illinois. Wright Foundation performative learning programs are integrated into the curriculum at Wright Graduate University.

The age of envy: how to be happy when everyone else's life looks perfect | Health & wellbeing

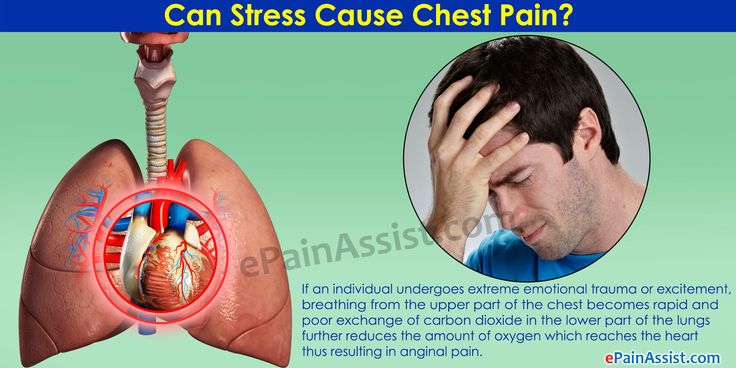

One night about five years ago, just before bed, I saw a tweet from a friend announcing how delighted he was to have been shortlisted for a journalism award. I felt my stomach lurch and my head spin, my teeth clench and my chest tighten. I did not sleep until the morning.

Another five years or so before that, when I was at university, I was scrolling through the Facebook photos of someone on my course whom I vaguely knew. As I clicked on the pictures of her out clubbing with friends, drunkenly laughing, I felt my mood sink so fast I had to sit back in my chair. I seemed to stop breathing.

I have thought about why these memories still haunt me from time to time – why they have not been forgotten along with most other day-to-day interactions I have had on social media – and I think it is because, in my 32 years, those are the most powerful and painful moments of envy I have experienced. I had not even entered that journalism competition, and I have never once been clubbing and enjoyed it, but as I read that tweet and as I scrolled through those photographs, I so desperately wanted what those people had that it left me as winded as if I had been punched in the stomach.

I had not even entered that journalism competition, and I have never once been clubbing and enjoyed it, but as I read that tweet and as I scrolled through those photographs, I so desperately wanted what those people had that it left me as winded as if I had been punched in the stomach.

We live in the age of envy. Career envy, kitchen envy, children envy, food envy, upper arm envy, holiday envy. You name it, there’s an envy for it. Human beings have always felt what Aristotle defined in the fourth century BC as pain at the sight of another’s good fortune, stirred by “those who have what we ought to have” – though it would be another thousand years before it would make it on to Pope Gregory’s list of the seven deadly sins.

But with the advent of social media, says Ethan Kross, professor of psychology at the University of Michigan who studies the impact of Facebook on our wellbeing, “envy is being taken to an extreme”. We are constantly bombarded by “Photoshopped lives”, he says, “and that exerts a toll on us the likes of which we have never experienced in the history of our species. And it is not particularly pleasant.”

And it is not particularly pleasant.”

Clinical psychologist Rachel Andrew says she is seeing more and more envy in her consulting room, from people who “can’t achieve the lifestyle they want but which they see others have”. Our use of platforms including Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Snapchat, she says, amplifies this deeply disturbing psychological discord. “I think what social media has done is make everyone accessible for comparison,” she explains. “In the past, people might have just envied their neighbours, but now we can compare ourselves with everyone across the world.” Windy Dryden, one of the UK’s leading practitioners of cognitive behavioural therapy, calls this “comparisonitis”.

And those comparisons are now much less realistic, Andrew continues: “We all know that images can be filtered, that people are presenting the very best take on their lives.” We carry our envy amplification device around in our pockets, we sleep with it next to our pillows, and it tempts us 24 hours a day, the moment we wake up, even if it is the middle of the night. Andrew has observed among her patients that knowing they are looking at an edited version of reality, the awareness that #nofilter is a deceitful hashtag, is no defence against the emotional force of envy. “What I notice is that most of us can intellectualise what we see on social media platforms – we know that these images and narratives that are presented aren’t real, we can talk about it and rationalise it – but on an emotional level, it’s still pushing buttons. If those images or narratives tap into what we aspire to, but what we don’t have, then it becomes very powerful.”

Andrew has observed among her patients that knowing they are looking at an edited version of reality, the awareness that #nofilter is a deceitful hashtag, is no defence against the emotional force of envy. “What I notice is that most of us can intellectualise what we see on social media platforms – we know that these images and narratives that are presented aren’t real, we can talk about it and rationalise it – but on an emotional level, it’s still pushing buttons. If those images or narratives tap into what we aspire to, but what we don’t have, then it becomes very powerful.”

To explore the role that envy plays in our use of social media, Kross and his team designed a study to consider the relationship between passive Facebook use – “just voyeuristically scrolling,” as he puts it – and envy and mood from moment to moment. Participants received texts five times a day for two weeks, asking about their passive Facebook use since the previous message, and how they were feeling in that moment. The results were striking, he says: “The more you’re on there scrolling away, the more that elicits feelings of envy, which in turn predicts drops in how good you feel”.

The results were striking, he says: “The more you’re on there scrolling away, the more that elicits feelings of envy, which in turn predicts drops in how good you feel”.

No age group or social class is immune from envy, according to Andrew. In her consulting room she sees young women, self-conscious about how they look, who begin to follow certain accounts on Instagram to find hair inspiration or makeup techniques, and end up envying the women they follow and feeling even worse about themselves. But she also sees the same pattern among older businessmen and women who start out looking for strategies and tips on Twitter, and then struggle to accept what they find, which is that some people seem to be more successful than they are. “Equally, it can be friends and family who bring out those feelings of envy, around looks, lifestyle, careers and parenting – because somebody is always doing it better on social media,” she says. How much worse would it have been for Shakespeare’s Iago, who says of Cassio: “He hath a daily beauty in his life / That makes me ugly,” if he had been following his lieutenant on Instagram?

While envying other people is damaging enough, “We have something even more pernicious, I think,” the renowned social psychologist Sherry Turkle tells me. “We look at the lives we have constructed online in which we only show the best of ourselves, and we feel a fear of missing out in relation to our own lives. We don’t measure up to the lives we tell others we are living, and we look at the self as though it were an other, and feel envious of it.” This creates an alienating sense of “self-envy” inside us, she says. “We feel inauthentic, curiously envious of our own avatars.”

“We look at the lives we have constructed online in which we only show the best of ourselves, and we feel a fear of missing out in relation to our own lives. We don’t measure up to the lives we tell others we are living, and we look at the self as though it were an other, and feel envious of it.” This creates an alienating sense of “self-envy” inside us, she says. “We feel inauthentic, curiously envious of our own avatars.”

We gaze at our slimming, filtered #OutfitOfTheDay, and we want that body – not the one that feels tired and achy on the morning commute. We spit out the flavourless “edible” flowers that adorn our bircher muesli – not much of a #foodgasm in reality. We don’t know what to do with the useless inflatable unicorn when the Instagram Story has come to an end. While we are busy finding the perfect camera angle, our lives become a dazzling, flawless carapace, empty inside but for the envy of others and ourselves, in a world where black cats languish in animal shelters because they are not “selfie-friendly”.

Envy is wanting to destroy what someone else has. It is silent, destructive, underhand – it is pure malice

There is a different, even darker definition of the concept of envy. For Patricia Polledri, psychoanalytic psychotherapist and author of Envy in Everyday Life, the word refers to something quite dangerous, which can take the form of emotional abuse and violent acts of criminality. “Envy is wanting to destroy what someone else has. Not just wanting it for yourself, but wanting other people not to have it. It’s a deep-rooted issue, where you are very, very resentful of another person’s wellbeing – whether that be their looks, their position or the car they have. It is silent, destructive, underhand – it is pure malice, pure hatred,” she says.

This can make it very difficult for envious people to seek and receive help, because it can feel impossible for them to take in something valuable from someone else, so strong is the urge to annihilate anything good in others and in themselves. She believes envy is not innate; that it starts with an experience of early deprivation, when a mother cannot bond with her baby, and that child’s self-esteem is not nourished through his or her life.

She believes envy is not innate; that it starts with an experience of early deprivation, when a mother cannot bond with her baby, and that child’s self-esteem is not nourished through his or her life.

As a cognitive behavioural therapist, Dryden is less interested in the root causes of envy, focusing instead on what can be done about it. When it comes to the kind of envy inspired by social media, he says, there are two factors that make a person more vulnerable: low self-esteem and deprivation intolerance, which describes the experience of being unable to bear not getting what you want. To overcome this, he says, think about what you would teach a child. The aim is to develop a philosophy, a way of being in the world, that allows you to recognise when someone else has something that you want but don’t have, and also to recognise that you can survive without it, and that not having it does not make you less worthy or less of a person.

Illustration: Alva SkogWe could also try to change the way we habitually use social media. Kross explains that most of the time, people use Facebook passively and not actively, idly and lazily reading instead of posting, messaging or commenting. “That is interesting when you realise it is the passive usage that is presumed to be more harmful than the active. The links between passive usage and feeling worse are very robust – we have huge data sets involving tens of thousands of people,” he says. While it is less clear how active usage affects wellbeing, there does seem to be a small positive link, he explains, between using Facebook to connect with others and feeling better.

Kross explains that most of the time, people use Facebook passively and not actively, idly and lazily reading instead of posting, messaging or commenting. “That is interesting when you realise it is the passive usage that is presumed to be more harmful than the active. The links between passive usage and feeling worse are very robust – we have huge data sets involving tens of thousands of people,” he says. While it is less clear how active usage affects wellbeing, there does seem to be a small positive link, he explains, between using Facebook to connect with others and feeling better.

Perhaps, though, each of us also needs to think more carefully when we do use social media actively, about what we are trying to say and why – and how the curation of our online personas can contribute to this age of envy in which we live. When I was about to post on Facebook about some good career-related news recently, my husband asked me why I wanted to do that. I did not feel comfortable answering him, because the truth is it was out of vanity. Because I wanted the likes, the messages of congratulations, and perhaps, if I am brutally honest, I wanted others to know that I was doing well. I felt ashamed. There is nothing like an overly perceptive spouse to prick one’s ego.

Because I wanted the likes, the messages of congratulations, and perhaps, if I am brutally honest, I wanted others to know that I was doing well. I felt ashamed. There is nothing like an overly perceptive spouse to prick one’s ego.

It is easy to justify publicising a promotion on Twitter as necessary for work, as a quick way of spreading the news to colleagues and peers. But as we type the words “Some personal news”, we could pause to ask ourselves, why are we doing this, really? Friends, family, colleagues – anyone who needs to know will find out soon enough; with news that is quite personal, do we need to make it so public? Honing your personal brand on social media may seem good for business, but it does have a price. It all creates an atmosphere where showing off – whether unapologetically or deceptively – is not just normalised but expected, and that is a space where envy can flourish.

It is about not interpreting envy as a positive or a negative, but trying to understand what it is telling you

I do not think the answer necessarily always lies in being more honest about our lives – it might sometimes lie in simply shutting up. Of course, raising awareness about previously hushed-up, devastating experiences of miscarriage or abuse or harassment can have the power to challenge stigma and change society. But ostensibly authentic posts about mindfulness, or sadness, or no makeup selfies are always designed to portray their poster in the best light.

Of course, raising awareness about previously hushed-up, devastating experiences of miscarriage or abuse or harassment can have the power to challenge stigma and change society. But ostensibly authentic posts about mindfulness, or sadness, or no makeup selfies are always designed to portray their poster in the best light.

For Polledri’s concept of envy at its most noxious, there can be no upside. But as a less extreme emotional experience, it can serve a function in our lives. Dryden differentiates between unhealthy envy and its healthy form, which, he says, “can be creative”. Just as hunger tells us we need to eat, the feeling of envy, if we can listen to it in the right way, could show us what is missing from our lives that really matters to us, Kross explains. Andrew says: “It is about naming it as an emotion, knowing how it feels, and then not interpreting it as a positive or a negative, but trying to understand what it is telling you that you want. If that is achievable, you could take proper steps towards achieving it. But at the same time, ask yourself, what would be good enough?”

But at the same time, ask yourself, what would be good enough?”

When I reflect on those two moments of piercing envy that I cannot forget, I can see – once I have waded through the shame and embarrassment (so much for keeping the personal personal) – that they coincided with acute periods of unhappiness and insecurity. I was struggling to establish myself as a freelance writer and, before that, struggling to establish a social life after leaving home for university in a new city. Both of these things have improved as time has passed, but I do still feel unpleasant pangs of envy every now and then, whether I’m on social media or off it, and I see it among my friends and family. Perhaps in part it is because we do not know how to answer the question: “What would be good enough?” That is something I am still working on.

Why we are jealous and how to stop doing it

November 6, 2021Relationships

There are often no real reasons, so it is up to you to cope with the problem.

Share

0 You can listen to the article. If you feel more comfortable, tune in to the podcast:

What causes jealousy

You are insecure

Licensed clinical psychologist Seth Meyers writes that people with low self-esteem can also feel insecure in relationships. They believe that they are not good enough to attract a partner and keep his interest over time.

You need to control everything

One partner worries about his place in the other's world. Perhaps, even in childhood, a person experienced a disturbing experience and now thinks that he cannot be trusted, because at any moment he can be preferred to another.

Anastasia Popova

Psychologist, systemic family psychotherapist of the Family Medical Center "Leib-Medic".

But this is not just anxiety. This is an attempt to control the actions of the other side. Fear of someone else's freedom and rebellion against it.

You are too strongly attached to a partner

Constant baseless jealousy may appear due to excessive attachment, when one cannot separate from the other and lives his life.

If you constantly interfere in the life of a companion, forbid meeting friends and spending time separately, the chances of destroying relationships are high. There is nothing wrong with a couple having common interests. But everyone should also have their own hobbies.

You project your own repressed desires onto your partner

Family psychotherapist Anastasia Popova notes that jealousy can arise due to the projection of one's own state and repressed sexual desires onto another person. Without admitting to ourselves, we want to go to the left, only now we attribute this to the satellite.

You have obsessive thinking

Jealousy can be the result of obsessive (obsessive) thinking. Psychologist Seth Meyers recalls the case of a patient who was jealous of partners in all her relationships. She also had some signs of obsessive-compulsive disorder. When her husband came home late, lingered, she could not put up with not knowing what and where he was doing. Therefore, I filled in the gaps and thought out myself. I took the facts out of my head, and then I was jealous and worried. She herself created disturbing thoughts and reasons for excitement when faced with the most terrible circumstance for this type of people: unknown .

She also had some signs of obsessive-compulsive disorder. When her husband came home late, lingered, she could not put up with not knowing what and where he was doing. Therefore, I filled in the gaps and thought out myself. I took the facts out of my head, and then I was jealous and worried. She herself created disturbing thoughts and reasons for excitement when faced with the most terrible circumstance for this type of people: unknown .

Also, according to the expert, jealousy can be caused by a person's general paranoid state.

There is a real reason for jealousy

Perhaps the most logical reason: there really is a reasonable reason for jealousy. Maybe this is an unambiguous correspondence with another or another, not yet forgotten betrayal or irrefutable evidence of infidelity.

How to stop being jealous

Accept and examine your thoughts

Robert Leahy, Ph.D., professor at Yale University, former president of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy, the Academy of Cognitive Therapy, and the International Association for Cognitive Psychotherapy, recommends that in the midst of jealousy, stop, exhale and pay attention to your thoughts.

Do they reflect the reality? If you think that a partner is interested in someone other than you, this does not mean that they are. You must understand that thoughts and reality are different things.

Don't give in to feelings of jealousy

Anger and anxiety can intensify if you start fixating on them. You need to accept your emotions and let them be. You don't have to "get rid of the feelings," but if you approach observing your experiences consciously, it will help to ease them.

Understand that uncertainty is part of any relationship

We are looking for certainty: “I need to know that she / he is not interested in you” or “I want to know that we will not part and be together.” Dr. Leahy writes that some are even ready to end the relationship before they think the other does.

Robert Leahy

Uncertainty is part of life. This is something we cannot do anything about.

It is impossible to know for sure whether your partner will leave you or not. But with your accusations and reproaches, you can create a self-fulfilling prophecy.

But with your accusations and reproaches, you can create a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Understand your conjectures

Jealousy can be fueled by unrealistic beliefs: past relationships of a loved one threaten your union, you have nothing to offer a partner, this relationship will repeat a bad experience with another or another. Often this is nothing more than speculation that has nothing to do with reality.

Find effective ways to build relationships

“Instead of relying on jealousy, find another way to make the union safer,” advises Robert Leahy. For example, pay attention when your partner does something good, praise each other, refrain from criticism and sarcasm, or make a list of simple and pleasant things that would please each of you.

Take care of yourself

We must not forget about our development. Find a hobby, play a sport, or take a yoga class. Do not deprive yourself and your beloved of freedom and personal space.

Show gratitude instead of jealousy

To a certain extent, jealousy is normal in a relationship. But only as long as it strengthens them, and does not destroy them.

But only as long as it strengthens them, and does not destroy them.

Anastasia Popova

It is useful to remember that besides me, a wonderful miracle, my partner has many other people in his life who can take my place. And that he or she chooses and prefers me over someone else.

A good alternative to jealousy is gratitude for choosing you, for being together. You can’t save a relationship with jealousy, but with gratitude it can work out.

Build up trust

Oleg Ivanov

Psychologist, conflictologist, head of the Center for Settlement of Social Conflicts.

Jealousy is usually "cured" by trust. If you do not trust your partner, be sure to talk to him about it.

He may not even guess about your feelings and not know that his behavior gives rise to them.

Accept the situation and reconsider the relationship

This applies precisely to those cases in which there are justified reasons to doubt the fidelity of a loved one.

Anastasia Popova

Jealousy can be a completely honest and normal feeling and have real reasons. Then you need not to suppress it, but to honestly see the unpleasant truth.

In this situation, it is necessary to decide what to do not with feelings of jealousy, but with relationships in general.

The problem can be dealt with. But, if it sits deep and is rooted in childhood, it is better to work out the issue with a specialist. Jealousy can be dangerous and even destructive for relationships, you should not leave it unattended.

Read also 🧐

- 3 effective ways to overcome jealousy

- 6 signs of an unhealthy relationship that people consider normal

- 15 tips that harm relationships

Jealousy for a friend: why we experience this feeling and what to do with it

When someone else appears in a relationship, it's unpleasant. But if jealousy for romantic partners seems understandable, then for friends - not always. They asked the psychologist where this feeling comes from, why we are jealous of friends and how we can help ourselves so as not to destroy relationships.

They asked the psychologist where this feeling comes from, why we are jealous of friends and how we can help ourselves so as not to destroy relationships.

We have a telegram channel! Subscribe to be the first to read the most interesting articles and participate in discussions.

Evgenia Dashkova

Contextual-behavioral psychologist

Where does jealousy come from

Jealousy is a complex social feeling that includes different emotions: it is anger, sadness, and love. It occurs when there is a threat of alienation of a significant person and loss of his attention.

We humans want to be intimate with other people. For us, as social beings, this is very important. And if a close person (friend, partner, parent) begins, for example, to communicate with someone else, we feel threatened. This threat can be real or imagined. And the task of jealousy is to reduce this threat.

And the task of jealousy is to reduce this threat.

Jealousy is not about selfishness, but about the fear of loss.

But!

There is such a thing as pathological jealousy. When jealousy can act as a form of violence in a relationship. In such cases, they often say “jealous of every pillar”: the partner does not let out of the house, checks correspondence, forbids seeing friends. But this is not about the feeling of jealousy, but about control, violence and abuse.

It is important to distinguish between jealousy as a feeling and as a control.

Jealousy for a partner and jealousy for a friend are not the same thing

Both jealousies are about the fear of losing a loved one. But there are differences, of course.

But there are differences, of course.

Since jealousy is a social feeling, cultural aspects are important. Culture dictates how we behave and feel. With respect to romantic love, the culture prescribes jealousy: we grew up on melodramas and romances that formed the "love and jealousy" link. Therefore, sometimes it may seem to people that if a partner is not jealous of them, then he does not love them.

In the relationship of friends, everything works a little differently. We can be jealous of friends, but not overreact. For example, there is a friend whom you love very much, but due to being busy, you cannot meet often. And one day on social networks you see a photo where she spends Friday evening in a bar with friends. Of course, you have a jolt: why not with me? But you are unlikely to run to write and demand an explanation. And if a romantic partner instead of meeting you chooses to spend the evening in a bar with another woman, then some questions already arise. Because the agreements in the relationship are different.

Because the agreements in the relationship are different.

Why we are jealous of friends

Man as a species has evolved in a group. It is important for us to have “our own” nearby - the one for whom we are more important than others. That's why it kind of tingles inside when a friend meets someone else at a bar. We regard this as a breach of attachment.

Attachment relationships are a vital need for all people, therefore their violation causes extremely strong feelings

We react to the violation of important relationships with emotions. Of course, most of us are more or less in control. But emotions still arise simply because we are human. There is nothing wrong with intelligent jealousy. This is a sign that close relationships may be at risk: take a closer look to see if something needs to be done to save this relationship.

What to do if jealousy gets in the way of friendship

Look for facts . There is such a technique in psychotherapy. When you experience an emotion, check whether it is true or not. Maybe you and your friend really always went hand in hand, and now he hasn’t met with you for two months and doesn’t answer your calls. Then the question arises not about what to do with this feeling, but about what to do with relationships.

If the emotion does not match the facts, you are still close, then the question is: how can you help yourself to experience this feeling? Maybe you are vulnerable right now, going through hard times, tired, in need of attention. Think about how you can help yourself. For example, if you're feeling lonely, you might want to try expanding your circle of friends.

Talk to a friend about your jealousy. But in any conversation about feelings, it is important to understand what you ultimately want from this conversation: just to speak out or some kind of change. In any case, you cannot demand that a girlfriend or boyfriend cut off all other contacts and devote time only to you.

But in any conversation about feelings, it is important to understand what you ultimately want from this conversation: just to speak out or some kind of change. In any case, you cannot demand that a girlfriend or boyfriend cut off all other contacts and devote time only to you.

Remember that feelings are hard to control. You can't clap and stop feeling. We cannot overcome the jealousy of a friend, but we can help ourselves to live this feeling and sympathize. I would recommend reading Christine Neff's books How to Get Through Life's Difficult Moments and Self-Compassion.

There are three steps to help soften an emotion:

-

Name the feeling. Without any ratings.

-

Normalize emotion. Some people find it helpful to say "most people would feel the same way if I were you.