Is it bad to be a sociopath

Inside The Mind Of A Sociopath : NPR

Inside The Mind Of A Sociopath The word "sociopath" often brings to mind criminals, killers, and people who are cruel and heartless. But writer and diagnosed sociopath M.E. Thomas wants to challenge that conventional wisdom. She says sociopaths are not inherently evil, and can be incredibly productive to society.

Mental Health

Heard on Tell Me More

NPR Staff

Inside The Mind Of A Sociopath

What exactly is a sociopath? Many people might think of killers, criminals, the cruel and heartless, Jack Nicholson's character in The Shining.

That's the common wisdom. But it's being challenged by a new memoir,

Confessions of a Sociopath: A Life Spent Hiding in Plain Sight. It's written under the pen name of M. E. Thomas. The author says most sociopaths are not incarcerated — and the silent majority of them live freely and anonymously. They're your neighbors, colleagues, maybe even family members and lovers.

Thomas admits that sociopaths can be dangerous; they're hungry for power, and they don't feel guilt or remorse. But they're not inherently evil, and some are highly productive members of society. Thomas herself is an attorney, law professor and Sunday school teacher. She founded the website SociopathWorld.com.

Interview Highlights

On the key traits of a sociopath

"They can be very charismatic. They don't really get nervous. ... They tend to fail to conform to social norms. They might come off as a little bit of an independent thinker. Or they might be committing crimes, depending on who they are. They have a facility with lying — well, they lie frequently, obviously to cover up certain aspects of themselves, or things that would indicate that they are a sociopath. Probably the biggest characteristic of a sociopath is their lack of empathy. ... They can't really imagine or feel the emotional worlds of other people. It's very foreign to them. And they don't have conscience."

Probably the biggest characteristic of a sociopath is their lack of empathy. ... They can't really imagine or feel the emotional worlds of other people. It's very foreign to them. And they don't have conscience."

On whether sociopaths can have fulfilling, loving relationships

"Definitely fulfilling, and I think loving; we feel a love. You know, whatever it is that we feel affection, for me it's maybe 70 percent gratitude, a little bit of adoration, a little bit of — if it's a romantic relationship — infatuation or sexual attraction. I think a complex emotion like love is made up of all sorts of little emotions. And our particular cocktail of love is going to look or feel different to us, but it's still there."

On changing the way we view sociopaths

"I think that there really has been so little research done about sociopaths. And the common wisdom now is that they are untreatable. And that, you know, sociopathy is basically synonymous with evil. ... You know, statistically everybody has interacted with a sociopath at one point. But the fact that most people can't identify who a sociopath is or remember those sorts of interactions suggests to me that it couldn't have been that bad of an interaction, right? Most people interact with sociopaths in positive ways and don't realize it. It's only when we catch them, and they are in prison, and we have gone through this lengthy trial to point out all the bad things that they've done, that we start thinking that sociopaths are bad."

... You know, statistically everybody has interacted with a sociopath at one point. But the fact that most people can't identify who a sociopath is or remember those sorts of interactions suggests to me that it couldn't have been that bad of an interaction, right? Most people interact with sociopaths in positive ways and don't realize it. It's only when we catch them, and they are in prison, and we have gone through this lengthy trial to point out all the bad things that they've done, that we start thinking that sociopaths are bad."

On realizing she's a sociopath

"I had just lost a job. I had just lost several relationships. And it wasn't the first time that something like this had happened to me, where my life seemed to just fall apart. And I thought, 'Well, I can't keep doing this — every few years have my life just go kaput. And so I thought, 'What is the common denominator here? It's me. There must be something that I'm doing that's causing this.' So I started going to therapy, and therapy didn't really help that much. ... But I remembered through therapy a casual diagnosis that one of my co-workers had made years before. And I explained to her how I viewed the world and my ethical principles, and she said very nicely, 'You might consider the fact that you are a sociopath.' So I looked it up, and I saw the traits, and it made sense. And it made sense in a way that nothing really before had."

... But I remembered through therapy a casual diagnosis that one of my co-workers had made years before. And I explained to her how I viewed the world and my ethical principles, and she said very nicely, 'You might consider the fact that you are a sociopath.' So I looked it up, and I saw the traits, and it made sense. And it made sense in a way that nothing really before had."

On why she wrote the memoir under a pen name

"There's a huge stigma against sociopaths, and I wanted to protect my family a little bit as well. I have little relatives who share my last name, and they've done nothing really to bring any sort of notoriety to themselves."

Sponsor Message

Become an NPR sponsor

Definition, vs. Psychopath, Test, Traits, and Symptoms

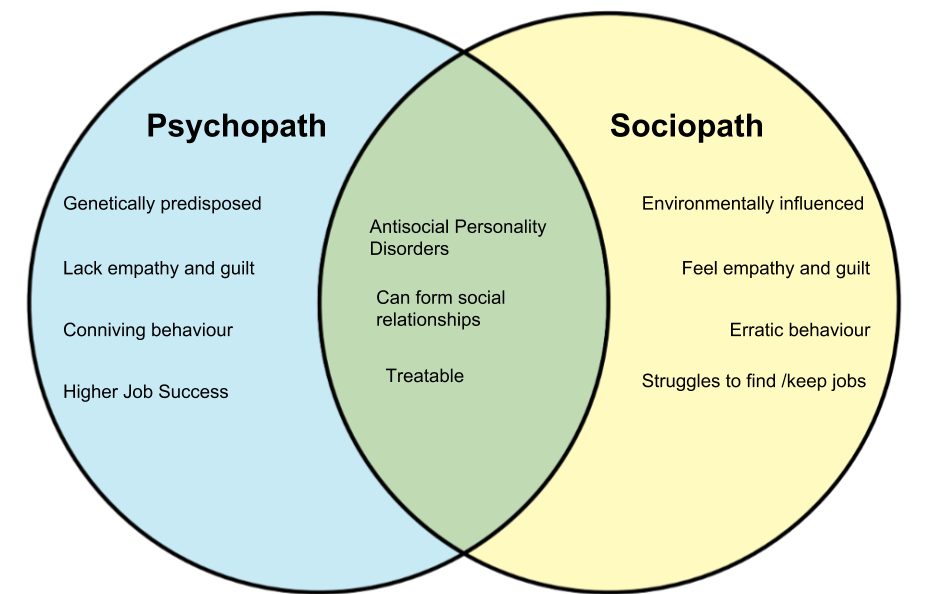

The term sociopath refers to someone living with antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) — as does the term psychopath.

The most recent edition of the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders” (DSM-5), which mental health professionals use to diagnose mental health conditions, defines ASPD as a consistent disregard for rules and social norms and repeated violation of other people’s rights.

People with the condition might seem charming and charismatic at first, at least on the surface, but they generally find it difficult to understand other people’s feelings. They often:

- break rules or laws

- behave aggressively or impulsively

- feel little guilt for harm they cause others

- use manipulation, deceit, and controlling behavior

Languate mattersBoth sociopathy and psychopathy have become well-recognized terms among mental health professionals, but neither represent an official diagnosis. They also carry a lot of stigma, particularly for people living with personality disorders, so it’s best to avoid describing anyone displaying violent or manipulative behavior as “sociopaths” or “psychopaths.”

Instead, focus on specific behaviors and actions. Rather than labelling a controlling ex as a sociopath, for example, you could say, “He would regularly remind me he was monitoring my social media activity.

”

Experts first began using the term sociopathy during the 1930s. Unlike “psychopathy,” it wasn’t easily confused with “psychosis.” The prefix also reflected a widely-held belief that the traits and behaviors associated with sociopathy related to socio-environmental factors.

Many researchers used sociopathy and psychopathy interchangeably until ASPD was added to the third edition of the DSM in 1980.

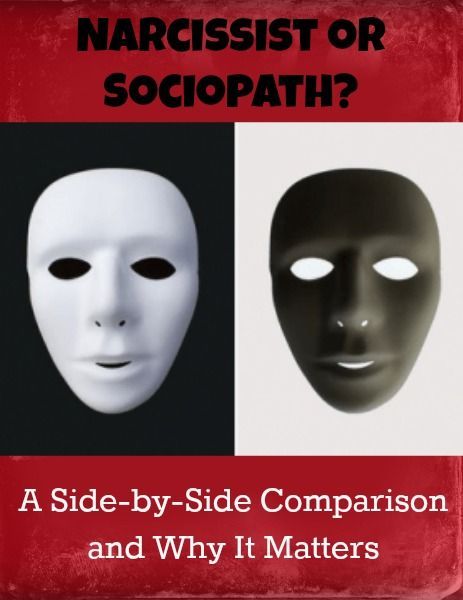

In a clinical setting, there’s no actual difference between sociopathy and psychopathy. A mental health professional won’t diagnose either of the two.

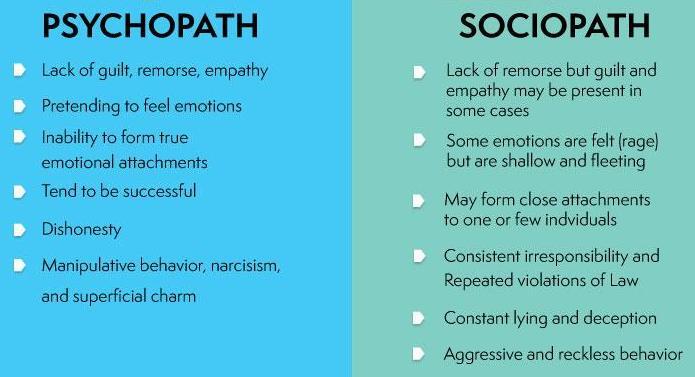

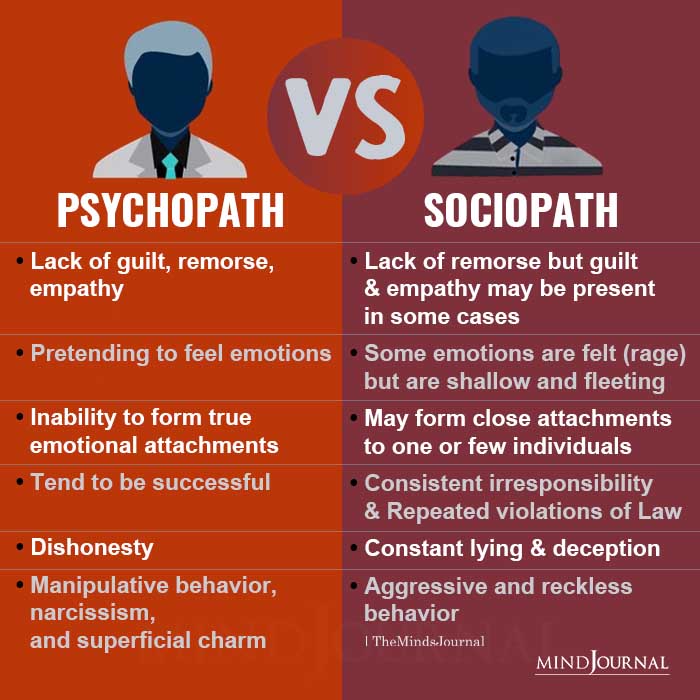

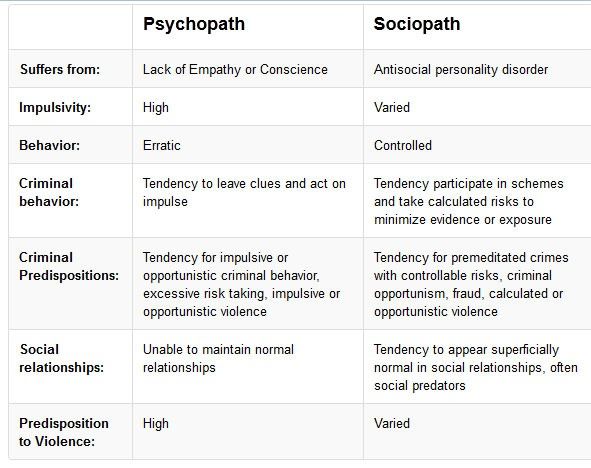

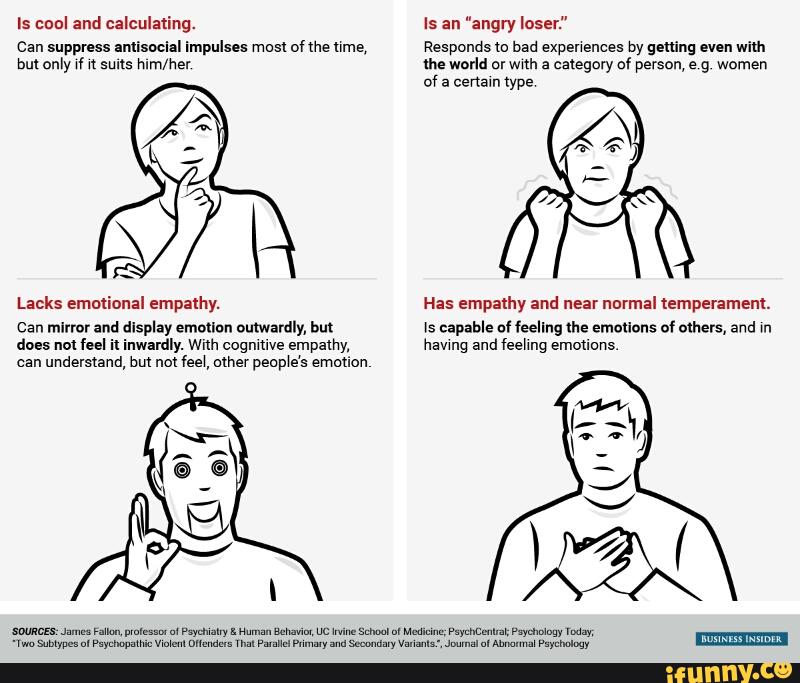

Some psychologists and researchers do make key distinctions between sociopathy and psychopathy. But these terms simply offer two slightly different ways of understanding the diagnosis of ASPD

In these interpretations, psychopathy is sometimes seen as involving more planned behavior. The behavior might not necessarily be violent, but it’s typically premeditated.

Research supports a few of these distinctions — to an extent.

Robert Hare, the psychologist who created the Psychopathy Checklist (PCL-R), defined sociopathy as involving a conscience and sense of right and wrong, or morality. But that sense of morality doesn’t line up with cultural and social norms. Instead, people with sociopathy often justify actions they recognize as “wrong.”

In a nutshell, people with sociopathy may have little empathy and a habit of rationalizing their actions. But they do know the difference between right and wrong.

Psychopathy, according to Hare, involves no sense of morality or empathy.

Research from 2013 suggests the difference between psychopathy and sociopathy may relate to differences in the brain, including gray matter volume and amygdala development. For people with sociopathy, increased neuron function in certain parts of the brain may factor into the development of some sense of morality.

There’s no standard list of sociopath signs, but the signs and symptoms of ASPD include a persistent pattern of disregard for others. For example:

For example:

- ignoring social norms and laws, or breaking rules at school or work, overstepping social boundaries, stealing, stalking and harassing others, and destroying property

- dishonesty and deceit, including using false identities and manipulating others for personal gain

- difficulty controlling impulses and planning for the future, or acting without considering the consequences

- aggressive or aggravated behavior, including frequent fights or physical conflict with others

- disregard for personal safety, or the safety of others

- difficulty managing responsibilities, including showing up at work, handling tasks, or paying rent and bills

- little to no guilt or remorse, or a tendency to justify actions that negatively affect others

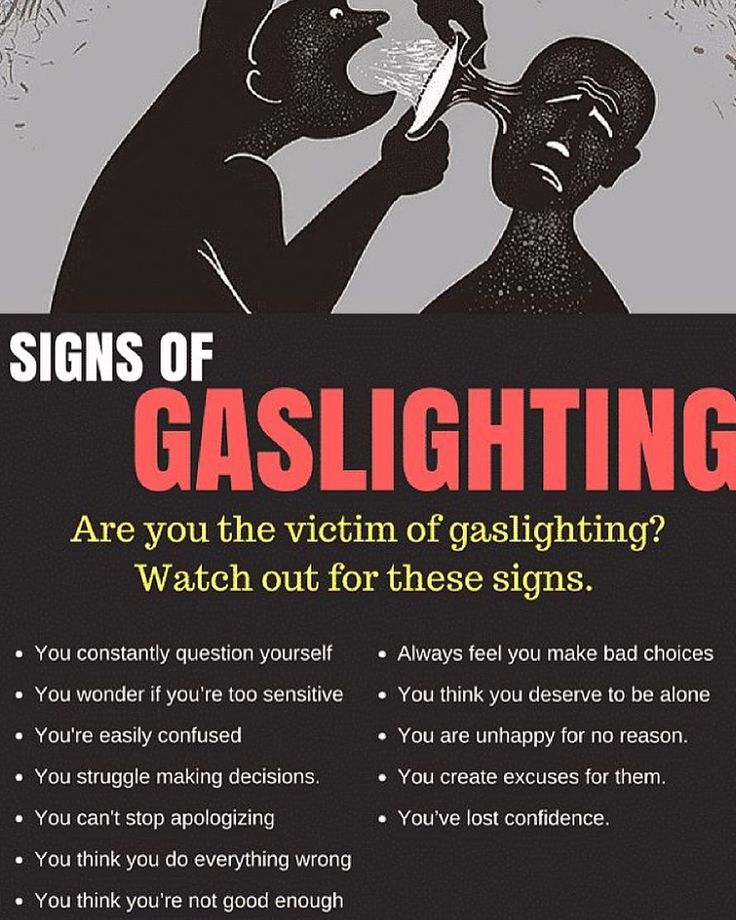

People with ASPD generally show little emotion or interest in the lives of others. They might:

- come across as arrogant or superior, with firmly fixed opinions

- use humor, intelligence, and charisma to manipulate

- seem charming at first, until their self-interest becomes clear

People with ASPD generally find it challenging to maintain friendships, relationships, and other mutually fulfilling connections. This difficulty may stem from traits, like:

This difficulty may stem from traits, like:

- low empathy and emotional intelligence

- difficulty learning from mistakes

- lack of concern for the safety of others

- a tendency to intimidate and threaten in order to maintain control

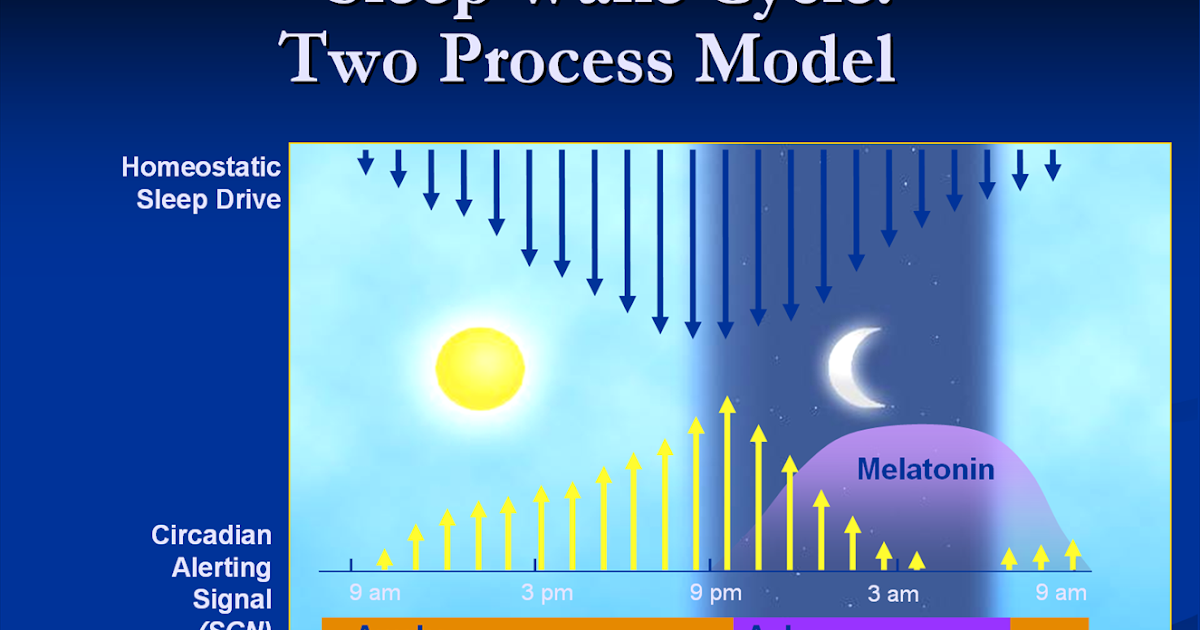

Many experts consider sociopathy more of an environmental construct than a genetic one.

Yes, brain chemistry and inherited genes play a part, but parenting styles and upbringing, along with other environmental factors, carry the most weight. (Psychopathy, on the other hand, appears linked to more innate biological factors.)

Children who don’t receive nurturing attention from caregivers tend to grow up learning they have to take care of themselves, because no one else will. Some children who experience abuse, violence, and manipulation from an early age may come to model this behavior as they navigate their own conflicts.

Research also suggests it’s possible to “acquire” sociopathy. Trauma or damage to the frontal lobes of the brain, which can happen as a result of a head injury or progressive conditions, like dementia, can lead to some antisocial behaviors.

Again, keep in mind that the DSM-5 makes no distinction between sociopathy and psychopathy, or any separate subtypes of ASPD.

Mental health professionals use DSM-established criteria to diagnose ASPD. This diagnosis can apply to someone whose behavior aligns with the accepted definition of either sociopathy or psychopathy.

A diagnosis of ASPD requires at least three of the seven signs listed above, plus a few additional criteria:

- These behaviors appear across multiple areas of life.

- The person is at least 18 years old.

- They had some symptoms of conduct disorder before the age of 15. This helps distinguish ASPD from lawbreaking behavior that begins in adulthood.

- Antisocial traits and behaviors don’t relate to schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

To make a diagnosis, a therapist or psychologist might:

- ask questions about a person’s feelings, thoughts, behavior, and personal relationships

- ask (with permission) family members and romantic partners about their behaviors

- evaluate their medical history for signs of other conditions

Keep in mind that personality disorders, including APSD, involve traits that are beyond the person’s control. These characteristics go beyond a desire for personal gain and tend to remain fixed over time, causing distress.

These characteristics go beyond a desire for personal gain and tend to remain fixed over time, causing distress.

Could it be a different condition?

Other mental health conditions can involve symptoms similar to ASPD:

- Intermittent explosive disorder (IED) involves extreme and repeated verbal or physical outbursts. These outbursts, driven by impulse or anger, can be directed toward people, property, or animals. IED commonly begins in adolescence and usually before the age of 40. On its own, it doesn’t involve low empathy or lack of remorse.

- Conduct disorder involves antisocial behavior that typically begins by the age of 16. Experts consider this condition a major risk factor for ASPD. Adults must show signs of conduct disorder in childhood to be diagnosed with ASPD. Someone who doesn’t meet full ASPD criteria might be diagnosed with conduct disorder.

- Schizophrenia often involves trouble recognizing facial emotions, a trait also associated with ASPD.

The condition may involve aggressive or antisocial behavior — but not always. It also involves psychosis, while ASPD does not. Experts won’t diagnose ASPD before treating schizophrenia.

The condition may involve aggressive or antisocial behavior — but not always. It also involves psychosis, while ASPD does not. Experts won’t diagnose ASPD before treating schizophrenia. - Bipolar I disorder. Episodes of mania can involve impulsivity, aggression and irritability, and increased thoughts of suicide — symptoms also linked to ASPD. Experts won’t diagnose ASPD during an episode of mania.

People living with personality disorders don’t always recognize any issues with their behavior, so they often don’t consider getting professional support.

They might choose to work with a therapist if prompted by a court order or someone in their personal or professional life.

Work supervisors, family members, and romantic partners might notice traits, like impulsivity and a tendency toward aggressive outbursts, for example, and they may recommend professional support.

Some people also try therapy to address other challenges or mental health concerns, including:

- depression

- difficulty coping with boredom or stress

- substance use disorders

But since many people living with ASPD never choose to go to therapy, little research on helpful treatment approaches exists. That doesn’t mean treatment can’t help. But therapy and other approaches generally only work when someone willingly puts in the effort.

That doesn’t mean treatment can’t help. But therapy and other approaches generally only work when someone willingly puts in the effort.

Possible treatments for ASPD include the following.

Psychotherapy

Therapy involves talking to a therapist about thoughts and feelings that can prompt harmful or aggressive behavior. It might also include anger management tactics or treatment for substance use.

Potentially beneficial approaches include:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT can help people learn to consider their responses to people and situations, which may lead to more productive behaviors. Therapy can, for example, help someone recognize the benefits of using negotiation rather than violence to solve conflict or disagreements. CBT also involves psychoeducation, which can teach people more about ASPD.

- Mentalization-based therapy (MBT). This approach aims to help people learn to better identify and understand mental and emotional mindsets — both their own and those of others.

A small 2016 study suggests MBT helped reduce hostility and anger, paranoia, self-harm and interpersonal difficulties in people living with both ASPD and borderline personality disorder, along with leading to an improved mood overall.

A small 2016 study suggests MBT helped reduce hostility and anger, paranoia, self-harm and interpersonal difficulties in people living with both ASPD and borderline personality disorder, along with leading to an improved mood overall. - Democratic therapeutic communities. This approach, often used in prisons, involves therapy groups of various sizes that help participants make collaborative decisions as part of a group and work together on problems affecting the community. It can help boost community-minded and prosocial thinking in people living with ASPD.

- Contingency management. This approach offers rewards to encourage treatment progress. Older research suggests it can help people living with ASPD limit intake of alcohol and other substances.

Medication

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) hasn’t approved any medications to treat symptoms of ASPD.

A doctor or psychiatrist may recommend medication for symptoms associated with the condition, such as:

- antipsychotics, like risperidone (Risperdal), as a first-line treatment for aggression

- SSRI antidepressants, like fluoxetine (Prozac), or mood stabilizers, like lithium, to help treat aggression

- anticonvulsants, like carbamazepine (Tegretol), to help reduce impulsivity

According to a small 2014 study, the antipsychotic medication clozapine (Clozaril) shows some promise as a treatment for men with ASPD. After taking the medication for several weeks, all seven participants experienced improvement in ASPD symptoms, including anger, impulsivity, and violence or aggression.

After taking the medication for several weeks, all seven participants experienced improvement in ASPD symptoms, including anger, impulsivity, and violence or aggression.

If you’d like to work on maintaining your relationship with someone who has ASPD, it may help to:

- recognize they may never fully understand your emotions

- explain specific ways their behavior affects others

- establish clear boundaries to protect your emotional and physical space

- encourage them to get professional support

Marriage or family counseling can also help you develop a more positive relationship with a loved one living with ASPD.

Ultimately, they may choose not to respect your boundaries and continue to cause emotional distress or physical harm. In that case, ending the relationship, or at least creating space from it, may be your safest option.

Working with a therapist yourself can also help you:

- explore productive communication

- build coping skills

- identify signs of abuse

- work on a plan to safely leave a relationship if needed

A therapist can also offer more specific guidance on handling problematic behaviors, including manipulation and control tactics or outbursts of anger.

Personality researchers and experts continue to explore the nuances of sociopathy and psychopathy. Still, they have yet to establish unique criteria to diagnose either, and ASPD remains the closest diagnosis to what people typically think of as psychopathy.

There’s no cure for ASPD. Some research suggests, though, that antisocial behavior often decreases over time. By middle age, people are less likely to behave in violent or aggressive ways.

Therapy approaches that help people learn to replace problematic behaviors with more constructive ones can also make a difference for ASPD symptoms.

In short, it’s absolutely possible for people with ASPD to build stable and fulfilling relationships with others, though it does take work.

Contrary to media portrayals, people who show signs of sociopathy don’t choose to be “evil.”

In many cases, they’re likely living with ASPD, a condition that develops from a combination of genetic and environmental factors, including childhood abuse and neglect.

9 signs that you are a sociopath

He has no conscience, he lies and does not blush, he does not blush at all, except perhaps from wine, but never from guilt. Do you know such a person? Congratulations. Although, however, there is nothing: most likely, you happened to meet a sociopath, and before it’s too late, run away from him. You won't like talking to him.

Sociopathy is a dissocial personality disorder that can affect anyone: your neighbor, boss, girlfriend, husband, child, police officer, and so on. The disorder is not congenital: if a psychopath is to be born, then sociopathy is the result of childhood trauma, perhaps even abuse, physical or emotional.

"Suffer" is not quite the right word: sociopaths don't suffer from their disorder at all. But those around you get it. Because sociopaths do not put them in a penny, they live for their own pleasure, and nothing will force them to at least look at their behavior from the outside.

Cold, sinisterly attractive, unaware of doubts and remorse, fearless and ready to take risks, these people are dangerous to others. But it is rather difficult to understand: sociopaths are so charming that it is easy to fall in love with them, to see a teacher, a guru, a savior of the fatherland. And only when your life is destroyed or at least turned upside down, you will start to look around and ask what it was.

But it is rather difficult to understand: sociopaths are so charming that it is easy to fall in love with them, to see a teacher, a guru, a savior of the fatherland. And only when your life is destroyed or at least turned upside down, you will start to look around and ask what it was.

The biggest problem with a sociopath is that they are hard to recognize.

More precisely, it is easy to misunderstand him: not knowing how to experience such feelings as love, compassion, shame, guilt, they know very well how to show them.

These are excellent actors: not every psychiatrist will be able to accurately determine the first time that he is a sociopath. What can we say about us mere mortals.

Why you need to stop tolerating resentment

When you feel that a loved one constantly raises self-esteem at your expense, do not blame yourself...

07 October 10:24

The easiest way to confuse a sociopath is with a narcissist - a charming, narcissistic idiot who endlessly flaunts in front of a mirror and posts selfies (according to a study conducted in 2015 at Ohio State University, men who often take selfies and select them for social networks are prone to narcissism) .

But wait. A sociopath is not an idiot at all. And he may have plans for you.

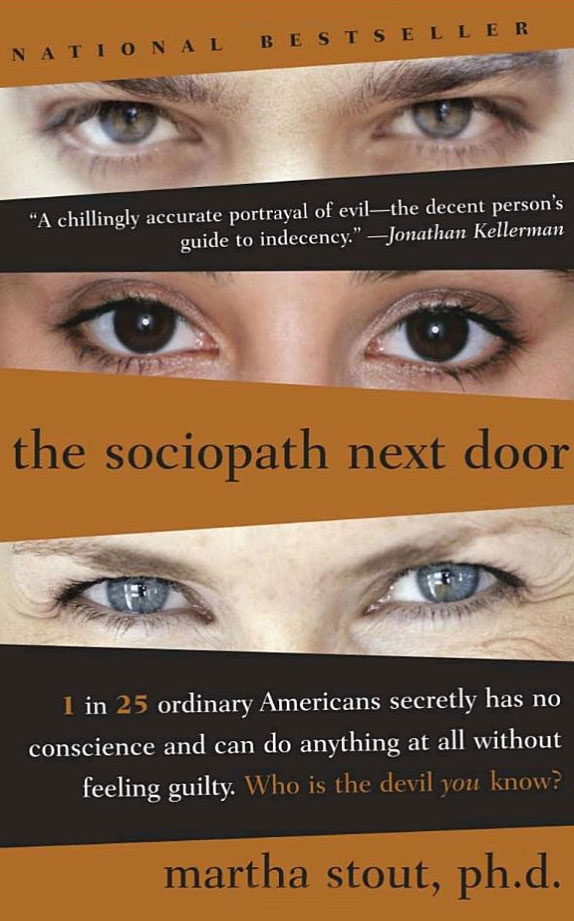

In 2005, American psychologist Martha Stout wrote a book that has become a classic, The Sociopath Next Door. In it, she clearly explains how high our chances are to suffer from the actions of sociopaths - because these are not movie characters.

Sociopaths often become criminals - but much more often their lack of conscience leads them to power.

And they begin to manage other people's lives in a way that suits them. To do this, you do not even need to declare yourself a guru or become the founder of a sect.

9 signs that you are at the mercy of a sociopath

1. He is charming

Sociopaths have a special attraction - and people who need to be nurtured and guided like to be around such a strong, powerful person. This calms them down, gives them confidence in the future.

In addition, sociopaths are often sexually attractive. By the way, they use it: promiscuity is one of the hallmarks of a sociopath.

2. He is unpredictable

And this distinguishes him from his psychopathic brother, with whom he is easily mistaken. Both do not experience emotions.

But if a psychopath is inclined to build and implement his plans in cold blood, then a sociopath is capable of spontaneous, inexplicable, often risky actions.

He can break the rules and go beyond the accepted.

3. He does not feel shame, regret or guilt

And it is pointless to be offended by them for this: they are simply arranged in such a way that such feelings are unknown to them. Because of this, alas, they can, without a twinge of conscience, betray, lie, intrigue, threaten - in general, harm other people in every possible way.

They act solely in their own interests - and because of this they often succeed in business and politics.

4. He likes to brag

More precisely, to exaggerate the significance of one's achievements or the exclusivity of one's experience. When telling a story from his life, a sociopath dramatizes events, embellishing, exaggerating, inventing colorful details - but at the same time he sounds extremely convincing.

When telling a story from his life, a sociopath dramatizes events, embellishing, exaggerating, inventing colorful details - but at the same time he sounds extremely convincing.

5. He must win at any cost

It is better not to compete with such a person at all: in any situation he needs to win, and he will not disdain any means. This is a desperate debater who always wins, and if he is caught in a lie, he will dodge to the end, but will never admit it.

Do you have symptoms of burnout at work. Quiz

Do you fantasize about being fired and can't see your colleagues? Gazeta.Ru dealt with the psychological...

February 16 15:01

6. He is very smart

High intelligence is rare, and it is especially offensive that sociopaths use their intellectual abilities to cheat and manipulate other people.

7. He doesn't love anyone

A sociopath is incapable of experiencing love. He can imitate it: he knows the right words and movements - so you don’t even know that, in fact, he is completely cold. But in fact, he does not know what love, empathy or sympathy is.

But in fact, he does not know what love, empathy or sympathy is.

8. He never apologizes

And no wonder, we already understood that he does not feel guilty. So why empty words, some kind of apology? For what? Even when he is caught by the hand or pushed against the wall, he does not admit that he was wrong. On the contrary, he goes on the attack.

Try to directly and convincingly accuse him of something, giving evidence and examples. In response, he will attack you with accusations, stating that you specifically want to denigrate him and are probably already weaving a secret conspiracy.

9. He often presents himself as a knight with high moral principles

In fact, he can be a swindler, a deceiver, even a thief, but in words it always turns out that he is desperately fighting for the truth. He imagines himself almost the only person thanks to whom the world has not yet collapsed.

In work groups, sociopaths often provoke conflicts, pit people against each other, and declare themselves to be saviors, ready to keep the company from disintegration and ruin.

What not to do when communicating with a sociopath

You probably already figured out who the sociopath is in your environment, and you were scared enough. The worst thing about this story is that you can't change a sociopath. It remains to understand what to do if, for example, it is impossible to completely avoid communication. Or at least - what not to do, as M.I. suggests in his blog Sociopath World. Thomas, author of Confessions of a Sociopath (Confessions of a Sociopath), published in the US in 2014.

Remember what doesn't work when dealing with a sociopath:

1. Accusations and counter-accusations

Trying to blame a sociopath will only lead to a scandal, from which you will come out, having failed.

2. Emotions

Sociopaths are not at all interested in hearing about how you feel about their behavior. Never show emotion or raise your voice in an argument with such a person.

3. Threats and ultimatums

Any pressure, including emotional pressure, is perceived by the sociopath as a challenge, as part of the game, and immediately joins the competition. Which is guaranteed to win.

Which is guaranteed to win.

4. Reasoning about good and evil

Don't try to judge what is good and what is bad, the sociopath doesn't know, which means he doesn't care.

“I am a sociopath” Should I be afraid of Dexter, Sherlock Holmes and Dr. House: Books: Culture: Lenta.ru

“I am a highly active sociopath! It's time to learn the terms already, ”the charming Benedict Cumberbatch-Holmes tells Martin Freeman-Watson in the famous film adaptation. And he is not the only one. The noble maniac Dexter and the cynical genius Dr. House, the "mentalist" Patrick Jane and Detective Saga Noren from The Bridge are cute but specific. They are sociopaths. And this is not bad, a certain M. Thomas convinces the reader. She is 30 years old, a licensed lawyer, and has antisocial personality disorder (i.e., sociopathy). In her book Confessions of a Sociopath, she says that there are more such people in the world than you might think. Many of them are rich, famous and hold high positions.![]() "Confessions of a Sociopath" will be published in early August by the Azbuka publishing house. Lenta.ru publishes an excerpt from the book.

"Confessions of a Sociopath" will be published in early August by the Azbuka publishing house. Lenta.ru publishes an excerpt from the book.

If my life were a TV show, this is how it would start. A warm summer day somewhere in the south of the States. On the surface of the pool ripples sparkling in the rays of the sun. With a soft rustle, the sliding door of the house opens. A young woman in flip flops and a black sports swimsuit comes out onto the porch. Dark hair flowing over the muscular shoulders of a professional swimmer. The skin is covered with a dark golden tan - the heroine of the show moonlights as a lifeguard at the local municipal beach in the summer. A woman is neither beautiful nor ugly; there is nothing outstanding, conspicuous in it. She looks like an ordinary athlete; there is a boyish clumsiness in her movements. It seems that a woman is completely indifferent to her body, she does not care if it is beautiful or ugly. She has long been accustomed to being half-naked, like most athletes.

Today she is expecting a student for a swimming lesson. She casually tosses a towel on a beach chair, brushes off her flip-flops as if she'll never need them again, and only then notices that something is moving in the pool.

It's something very small, and the woman realizes what it is only when she comes to the edge of the pool. A baby opossum, hardly a week old, is desperately floundering in the water. Tiny pink paws hit the water. The animal struggles to keep a microscopic pink nose above the surface. The poor thing must have fallen into the pool at night. The opossum is still too small to jump to the edge of the pool. The body of the cub trembles with fatigue. Eyes covered with a veil of incredible fatigue. A little more, and the animal will give up and go to the bottom.

With a quick movement, the woman puts on her flip-flops again and thinks for a moment. Then he resolutely takes the net and heads for the pool. A close-up camera shows how the net descends and covers a small opossum, crushing its hind legs. With a quick, almost imperceptible movement, the woman pulls the animal under the water. Only his head remains above the water. The animal beats frantically, making plaintive, weeping sounds. A new danger gives it strength, it breaks out from under the net, emerges to the surface, manages to take a breath of life-giving air, but the net again inexorably pulls it to the bottom. However, the circle of the net is not completely immersed in the water, and the animal breaks out of the trap.

With a quick, almost imperceptible movement, the woman pulls the animal under the water. Only his head remains above the water. The animal beats frantically, making plaintive, weeping sounds. A new danger gives it strength, it breaks out from under the net, emerges to the surface, manages to take a breath of life-giving air, but the net again inexorably pulls it to the bottom. However, the circle of the net is not completely immersed in the water, and the animal breaks out of the trap.

The woman sighs and picks up the net. For a fraction of a second, the baby opossum feels relieved, but then again begins to frantically thrash the water with its tiny paws. The woman drops the net on the ground, takes a towel from the chair and goes into the house. Picks up the phone, calls the student and cancels the class, citing problems with the pool. Taking out the keys from the desk drawer, he leaves the house and runs to a powerful car, which he has been driving since the age of 16. The eight-cylinder engine sneezes and roars to life. The woman turns on the reverse gear and, not really caring about the cars standing nearby, leaves - she suddenly had a day off, she needs to spend it properly.

The woman turns on the reverse gear and, not really caring about the cars standing nearby, leaves - she suddenly had a day off, she needs to spend it properly.

Frame: True Detective series

At dusk the woman comes back, goes to the pool and sees a small dark shadow at the bottom. Picking up the same net, she deftly hooks the dead body and throws it over the fence, onto the neighbor's plot. Throwing an antiseptic tablet into the pool, he goes into the house. The camera pans to the calm expanse of water in the pool. The ripple is no more. Blackout.

I am a sociopath. As a result of the intricacies of genetics and upbringing, I suffer from "antisocial personality disorder" (colloquially "sociopathy"), which is described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Psychiatric Disorders as "persistent behavior characterized by disregard for the rights of others and violation of these rights." Key symptoms leading to a diagnosis are an inability to repent and comply with social norms, coupled with a tendency to deceive. I myself prefer to define sociopathy as the sum of the traits that have shaped my personality, but do not define who I am. I am free from confusing and irrational emotions, good at making strategic plans, smart, self-confident and charming. At the same time, I try to notice when other people are emotional or embarrassed, and respond in a socially acceptable way.

I myself prefer to define sociopathy as the sum of the traits that have shaped my personality, but do not define who I am. I am free from confusing and irrational emotions, good at making strategic plans, smart, self-confident and charming. At the same time, I try to notice when other people are emotional or embarrassed, and respond in a socially acceptable way.

The terms psychopathy and sociopathy have the same clinical origin and are often used interchangeably, although some experts distinguish them based on genetic factors, attitudes toward aggression, and other manifestations. I prefer to call myself a sociopath, because the root "psycho" causes negative associations. I do suffer from a certain mental disorder, but I am by no means crazy.

Genetic factors I can trace back to my biological grandfather, who is said to have been an exceptionally cold and callous person. His scarred face spoke volumes of impulsiveness, risk-taking, and violence. A scientist, rocket designer, he imagined himself a cowboy all his life. He swelled all the savings he inherited into the ranch, which he brought to complete collapse, and then sold to pay taxes. He did not want to marry his grandmother, but she became pregnant; he was forced into marriage, but ran away a few months after his father was born. The grandfather voluntarily renounced parental rights and never met his own son in his life. I don't know anything about my grandfather's parents, but I think that an apple doesn't fall far from an apple tree.

He swelled all the savings he inherited into the ranch, which he brought to complete collapse, and then sold to pay taxes. He did not want to marry his grandmother, but she became pregnant; he was forced into marriage, but ran away a few months after his father was born. The grandfather voluntarily renounced parental rights and never met his own son in his life. I don't know anything about my grandfather's parents, but I think that an apple doesn't fall far from an apple tree.

Frame: film The Shining

My upbringing contributed to the development of pathological traits in me too, although not quite in the way that is shown in documentaries about sociopaths. As a child, I was treated very well. I didn't become a murderer or a criminal. I have never been in prison, preferring the ivy-covered arbor to the cell. I am a trained lawyer and lecturer in law, a typical young scholar who regularly publishes articles in special journals. I donate ten percent of my income to charity and teach Sunday school for free. I have excellent relationships with relatives and friends, I love them very much, and they love me.

I have excellent relationships with relatives and friends, I love them very much, and they love me.

Do you recognize yourself in this description? Maybe you're a sociopath too? Recent studies have shown that sociopaths make up 1 to 4 percent of the population. It turns out that every 25th of us is like that. It turns out that there are more sociopaths than people suffering from anorexia or autism. Are you a serial killer? Never been in jail? Make no mistake - the same goes for the vast majority of us. You may be surprised to learn that the fact that you are not a criminal does not relieve you of the diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder. Only 20 percent of the men and women in prison are sociopaths, although we are probably responsible for half of the serious crimes. Also, most sociopaths don't go to jail. The vast (and silent) majority of them live in freedom, quietly and unnoticed; they work, marry, marry, have children and achieve significant success in a society that considers them monsters.

So who are sociopaths? Our name is legion, and we are very diverse. At least one looks like me. Maybe the other one is on you?

Do you have many friends, fall in love with you, admire you? This means nothing. On the contrary, despite our bad reputation, we sociopaths have an irresistible, if superficial charm. In our world, populated mainly by sullen, ordinary nonentities, biting each other like rats and fussily rushing to feeders, we stand out very favorably, and people are drawn to us like moths to a candle flame.

If we could meet, you would like me. I am quite sure of this, as I know a sufficient number of people who fall under my spell. My smile is like a star of a TV show: I smile, showing (very rare!) shining teeth, and attract, not repel attention. I'm the girl you'd love to bring to your ex-wife's wedding. Joy, pleasant excitement from a great escort - your boss's wife would be delighted with such a sweet creature. Your parents would be very happy to see such a smart and successful girl like me in their house.

Do you have a very high opinion of yourself? For example, I value myself highly. The ego of sociopaths - this has long been known - is always in the body, like the women on the canvases of Rubens. I simply radiate self-confidence, and its level does not correspond to my condition and social position. I'm not tall, but I have broad shoulders and a square chin. Friends often comment on my firmness and self-confidence. However, I feel equally good in a summer dress and cowboy boots.

Shot: House M.D.

Perhaps the most noticeable sign of my self-confidence is the ability to withstand the gaze of others. Some people think I have a "predator's eye"; I think it is characteristic of most sociopaths. The ability to keep one's eyes open is seen by many as a sign of hostility. For example, visitors to the zoo are not advised to look into the eyes of gorillas, as for them such a look is a signal to attack. Apparently, the majority of people think the same way, because otherwise the competition of views would not be so defiantly difficult. We sociopaths are not like that. We are not at all embarrassed by the eyes of others. The fact that we do not politely look away is perceived as a sign of self-confidence, aggression, seduction or predation. For some, this ability of ours throws us off balance; but often it is also perceived as a sign of passionate love.

We sociopaths are not like that. We are not at all embarrassed by the eyes of others. The fact that we do not politely look away is perceived as a sign of self-confidence, aggression, seduction or predation. For some, this ability of ours throws us off balance; but often it is also perceived as a sign of passionate love.

Have you ever found that your charm and self-confidence make people do things for you that they would never do for another less confident person? Some call it manipulation, but I believe that I have the ability to dispose of what God has given me. The very word manipulation strikes me as disgusting. People use it to avoid being responsible for their own choices. If a person does not regret his decision, does this mean that no one manipulated him?

A lot of people think that manipulation is the area where the traits of a sociopath look the most repulsive, but I don't understand why. This is not manipulation, but just an equal exchange. People always want something - to please you, to be needed and wanted, to be considered good, and manipulation is a quick, if dirty, way to get them what they want. You can, of course, consider that they are seduced. A sociopath friend of mine gives the following example. Let's say someone wants to sell a car for five thousand dollars, and another wants to buy the same car for ten thousand. I know these two people are strangers. I buy a car for five thousand, sell it for ten thousand and make five thousand bucks. On Wall Street and places like that, it's called buying and selling securities, and they do it day in and day out, and no one thinks it's reprehensible. Everyone got what they wanted, and everyone will be happy if they do not learn more than what is needed. I took advantage of someone else's ignorance, to the satisfaction of the seller and the buyer, and to my own advantage.

You can, of course, consider that they are seduced. A sociopath friend of mine gives the following example. Let's say someone wants to sell a car for five thousand dollars, and another wants to buy the same car for ten thousand. I know these two people are strangers. I buy a car for five thousand, sell it for ten thousand and make five thousand bucks. On Wall Street and places like that, it's called buying and selling securities, and they do it day in and day out, and no one thinks it's reprehensible. Everyone got what they wanted, and everyone will be happy if they do not learn more than what is needed. I took advantage of someone else's ignorance, to the satisfaction of the seller and the buyer, and to my own advantage.

Indeed, I believe that people who deal with sociopaths often get more than when dealing with "normal" people. Sociopaths are the lubricant that keeps the wheels of the world turning. We make dreams come true, or at least pretend to make them come true. Sometimes we alone in the world show the greatest concern for the needs and needs of others, while skillfully masking the true reasons for our attention. We carefully look at the intended victim and try to become the embodiment of what she needs - a good employee, boss or lover. By no means always our mask hides evil intentions or dark intentions. Our victim, as a rule, feels great during the exchange, and usually everything goes smoothly and ends to mutual satisfaction. Of course, any of our actions has its price: we never do anything for free, we always want to get something in return - money, power or just the pleasure of someone else's admiration, but this does not mean that our partners do not receive anything. It may seem to you that it is too expensive, but if you make a deal with the devil, then no angel has offered you better conditions.

We carefully look at the intended victim and try to become the embodiment of what she needs - a good employee, boss or lover. By no means always our mask hides evil intentions or dark intentions. Our victim, as a rule, feels great during the exchange, and usually everything goes smoothly and ends to mutual satisfaction. Of course, any of our actions has its price: we never do anything for free, we always want to get something in return - money, power or just the pleasure of someone else's admiration, but this does not mean that our partners do not receive anything. It may seem to you that it is too expensive, but if you make a deal with the devil, then no angel has offered you better conditions.

How are your morals? Don't you find it much easier to judge yourself and others by the "survival of the fittest" standard? People sometimes reproach us that we do not know how to regret and repent, and they think that this is bad. For some reason, it is believed that the ability to experience guilt is an essential sign of a good person. But I think that in the world there is no universal, much less "objective" morality. Theologians and philosophers have been breaking spears in disputes for thousands of years, but have never come to an unambiguous conclusion about what it is and what are the signs and measure of high morality. From my point of view, it is difficult to believe in something so elastic and changeable, and besides, it justifies such horrors as honor killings, "just" wars and the death penalty. Like most people, I am religious, and it is faith that guides my life morally, gives me confidence, helps me avoid prison and remain invisible in the crowd. But the essence of morality has always eluded me and still eludes me.

But I think that in the world there is no universal, much less "objective" morality. Theologians and philosophers have been breaking spears in disputes for thousands of years, but have never come to an unambiguous conclusion about what it is and what are the signs and measure of high morality. From my point of view, it is difficult to believe in something so elastic and changeable, and besides, it justifies such horrors as honor killings, "just" wars and the death penalty. Like most people, I am religious, and it is faith that guides my life morally, gives me confidence, helps me avoid prison and remain invisible in the crowd. But the essence of morality has always eluded me and still eludes me.

I have a pragmatic view. I submit to the requirements of morality when it suits me, and in other cases I act as I need, without being bothered by the search for self-justifications.

(…)

Have you ever, to the horror of those around you, made important decisions with lightning speed? Sociopaths are famous for their spontaneity of behavior. For example, I simply do not know peace; it is difficult for me to concentrate on one thing for a long time, I rarely stay in one job for more than a few years. Sociopaths need external stimuli like air, without them we start to get bored and act thoughtlessly. The dark side of our impulsiveness is that we fix our attention on one thing, distracted from everything else, and lose the ability to listen to the arguments of reason. But if the majority, succumbing to the moment, lose their heads, I do the same with a cold heart.

For example, I simply do not know peace; it is difficult for me to concentrate on one thing for a long time, I rarely stay in one job for more than a few years. Sociopaths need external stimuli like air, without them we start to get bored and act thoughtlessly. The dark side of our impulsiveness is that we fix our attention on one thing, distracted from everything else, and lose the ability to listen to the arguments of reason. But if the majority, succumbing to the moment, lose their heads, I do the same with a cold heart.

Frame: TV series Dexter

I have never killed anyone, although I often wanted to, but here I am hardly different from the others. I rarely wanted to kill someone close to me; more often such a desire arose in relation to random people who for some reason caused irritation. Once, when I was in Washington for a legal conference, a subway worker tried to shame me for trying to get on a closed escalator. He asked me in English with a strong foreign accent, "Don't you see the yellow barrier?"

Me: Yellow barrier?

OH: Yes! I just put up a barrier, which means the escalator is closed!

I look at him without any expression.

OH: This is a violation! Don't you know that you can't enter a closed escalator? You are breaking the law!

I remain impassive.

OH: (obviously taken aback by my lack of response): Okay, don't break it next time, okay?

No, it's not okay! Having done something terrible, people often explain later that they “lost it”. I am very familiar with this feeling. At that time, I stood, waiting for a wave of rage to overwhelm the part of the brain responsible for decisions. When the moment arrived, I was filled with icy calm and determination. Squinting my eyes and clenching my teeth, I followed the worker. Adrenaline rushed through my blood. My mouth was dry and there was a metallic taste. By an effort of will, I forced myself to carefully monitor everything that was happening around, trying to predict how the crowd would behave. Before that, I had not been to Washington and rarely rode the subway. Rush hour hasn't arrived yet. I expected that he would go alone into some deserted passage or unlocked room and there I would find him alone. I was completely focused on what I would do next. In my imagination, my fingers closed on his throat and life gradually left him. This is a manifestation of the highest justice, it seemed to me.

I was completely focused on what I would do next. In my imagination, my fingers closed on his throat and life gradually left him. This is a manifestation of the highest justice, it seemed to me.

Now it's strange to think about it. I weigh 60 kilograms, and he was at least 75. Like all musicians, I have strong arms, but are they strong enough to strangle a large man? Is it easy to take a life? When it came down to it one day, I couldn't even drown a baby opossum. I was under the illusion of my own strength, but in the end nothing happened - I lost the worker in the crowd. The rage dissipated as quickly as it had arisen.

I often ask myself what would have happened if I had not lost sight of him. I'm sure I couldn't kill him, but I almost certainly know I would. Would he resist? Would I get hurt? Would the police intervene? Is there anything I could say or do to get myself out of an awkward situation? I often think about this and many other similar cases and I understand that one day I can get into a very ugly story.